Abstract

Rare facial nerve branching patterns, pose dangers due to their unexpected course. Cases with multiple branches may reduce the intraoperative risk, due to the compensation of adjacent branches. We present a case of a cadaveric specimen where an early trifurcation of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve was noted.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12070-022-03352-2.

Keywords: Facial nerve, Cadaveric, Anatomy, Mandibular branch of facial nerve

Introduction

Distribution of the extratemporal segment of the facial nerve follows complicated patterns [1]. During salivary gland, mandible, or facial plastic surgery, facial nerve integrity is crucial considering the negative impact on a patient’s quality of life following a permanent postoperative facial nerve palsy [2]. A necessary sacrifice or an inadvertent injury of the nerve should always be restored either by a direct anastomosis or with the use of a nerve-free graft to reduce postoperative morbidity. The sural nerve and great auricular nerve remain the workhorses in this process [3]. The House-Brackman classification is used in everyday practice to assess the function of the nerve based on the impairment of the mimic muscles [4]. The marginal branch of the facial nerve and its relationship with the mandible is well-documented [1]. However, uncommon variations should be mentioned for further understanding of the intraoperative risks and better preoperative planning.

There is still an ongoing debate about the anatomical variations in the branching pattern of facial nerve. Davis classification remains the gold standard in the depiction of the main patterns [5]. However, there is still unanswered questions. The presence of bilateral symmetry seems not to be the case and many authors believe that every facial nerve has a unique pattern [1]. Besides the normal anatomical variability, there are still anomalies that range from total agenesis of the nerve to partial hypoplasia [6].

In addition, the extratemporal course of facial nerve is strongly depended on the temporal bone anomalies and variations that may play a significant role in otosurgery. Ear malformations are strongly related to aberrant facial nerve both intra and extratemporally, make it prone to injuries during surgery [7]. Thus, recruitment of endoscopes is indicated to avoid inadvertent injuries during cochlear implantation in malformed ears [8].

Case Report

A trifurcation of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve was observed during the dissection of a 76-year-old Caucasian male formalin embalmed cadaver from Northern Greece. The cadaver was donated to the Department of Anatomy, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. A heart attack was documented as the cause of death. Dissection of the cadaver was carried out as part of a major project to map the microanatomy of the extratemporal portion of the facial nerve in Greece. Dissection of the cadaveric specimen did not reveal any gross pathology in the head and neck region. Furthermore, there was no evidence of previous surgical interventions. The extratemporal part of the facial nerve was dissected meticulously in a retrograde fashion. Measurements were performed independently by two investigators and the mean values were used for analysis. The interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was recruited to settle the interobserver and intraobserver reliability.

On the right side, no gross anatomical variation was recorded and a type III distribution pattern according to Davis classification was noted [5]. However, on the left side an interesting variation was observed. The left mandibular branch was trifurcated and followed a unique course. Thus, Davis classification could not be applied to define the recorded distribution pattern.

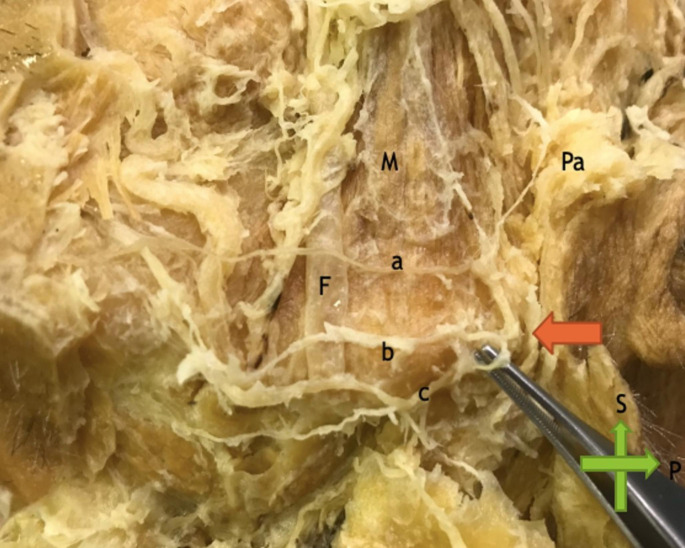

Specifically, the mandibular branch of the facial nerve was trifurcated in a very complicated manner (Fig. 1). The point of trifurcation was 0.63 cm after the emergence of the parotid gland fascia.

Fig. 1.

Cadaveric specimen of the left mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Point of trifurcation (red arrow), a: upper branch, b: middle branch, c: lower branch, Pa: parotid gland, F: facial vein, M: masseter muscle, S: superior, P: posterior

The upper branch followed a horizontal course 0.72 cm above the inferior border of the mandible lateral to the masseter muscle. After a 3.12 cm course and in the most anterior part of the masseter muscle a bifurcation was noted, with one upper anastomotic branch to the buccal branches.

The middle branch crossed horizontally just upon the inferior border of the mandible and was bifurcated after a long 4.74 cm course without anastomotic branches.

The lower branch crossed a more inferior course 0.71 cm below the inferior margin of the mandible, without any anastomotic branches or ramifications.

It should be stated that every branch was finally distributed in the depressor anguli oris muscle.

Discussion

According to the literature, the mandibular branch of the facial nerve has almost always a single trunk with either a late bifurcation or trifurcation before the depressor anguli oris muscle or an anastomotic branch to the most inferior buccal branch [5,]. It is apparent, that an injury of the trunk during parotid surgery will lead to ipsilateral palsy due to lack of innervation of the depressor anguli oris muscle. This complication is considered devastating both for the patient and for the surgeon. However, late terminal branches are described in the literature, and the bifurcation or trifurcation of the nerve is not proximal to the parotid fascia [9]. In other large studies, no trifurcation of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve was recorded, but a late bifurcation was the case in the majority of them [10].

Davis classification remains the cornerstone in the extratemporal segment of the facial nerve distribution pattern [5]. Although, newer investigations suggested new patterns or modified patterns, a recent systematic review of Poutoglidis et al. [1] confirmed the value of Davis classification as the most accurate one. Anatomical variations with significant differences from the classic patterns of Davis classification remain rare exceptions [1]. The recognition of the correct distribution pattern intraoperatively helps the surgeon to avoid an injury to the nerve but does not always suffice. The presence of rare cases like this confirms the complexity of the facial nerve distribution and alerts even experienced surgeons to be ready for unexpected patterns during surgery. The old-fashioned opinion that neuromonitoring should not be considered for experienced surgeons with deep knowledge of facial nerve anatomy is ill-advised. Anatomical landmarks are useful to identify both the main trunk of facial nerve but they cannot be used in every case [1]. Pathology, like parotid tumors may change significant the distance between a landmark and facial nerve trunk.

The wide variability of facial nerve course and pathology makes neuromonitoring mandatory in the vast majority of parotid and ear surgeries.

Our findings suggest that in cases where multiple mandibular branches exist direct damage to the nerve may not cause even temporary palsy due to the compensation of the other branches. In cases of inadvertent damage of the facial nerve during parotid surgery, it is strongly recommended to search for the presence of another branch proximal to the injured nerve. If it is confirmed from the dissection and the facial monitoring, that this nerve provides sufficient innervation to depressor angular oris muscle, no other measurements need to be taken. As a take home message, readers should consider that retrograde dissection always consists a safe and decent way to protect the nerve. In cases of multiple variations or pathologies that infiltrate the main trunk of the facial nerve a retrograde approach is the most legit way to proceed in order to perform a lege artis procedure.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

Researchers did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Statements and Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to be reported.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Poutoglidis A, Paraskevas GK, Lazaridis N, et al. Extratemporal facial nerve branching patterns: systematic review of 1497 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 2022;26:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0022215121003571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poutoglidis A, Tsetsos N, Sotiroudi S, Fyrmpas G, Poutoglidou F, Vlachtsis K. Parotid gland tumors in Northern Greece: a 7-year Retrospective Study of 207 patients. Otolaryngol Pol. 2020;75(2):1–5. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0014.5731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MC, Kim DH, Jeon YR, et al. Functional outcomes of multiple sural nerve grafts for facial nerve defects after tumor-ablative surgery. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(4):461–468. doi: 10.5999/aps.2015.42.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bylund N, Hultcrantz M, Jonsson L, Marsk E. Quality of life in Bell’s Palsy: correlation with Sunnybrook and House-Brackmann over Time. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(2):612–618. doi: 10.1002/lary.28751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis RA, Anson BJ, Budinger JM, Kurth LR. Surgical anatomy of the facial nerve and parotid gland based upon a study of 350 cervicofacial halves. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1956;102:385–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaqoob A, Dar W, Raina A, Chandra A, Khawaja Z, Bukhari I, Ganie H, Wani M, Asimi R. Moebius Syndrome. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2021;24(6):929. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_182_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giesemann AM, Neuburger J, Lanfermann H, Goetz F. Aberrant course of the intracranial facial nerve in cases of atresia of the internal auditory canal (IAC) Neuroradiology. 2011;53(9):681–687. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poutoglidis A, Fyrmpas G, Vlachtsis K, Paraskevas GK, Lazaridis N, Keramari S, Garefis K, Dimakis C, Tsetsos N. Role of the endoscope in cochlear implantation: a systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2022;47(6):708–716. doi: 10.1111/coa.13909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marolt C, Freed B, Coker C, et al. Key anatomical clarifications for the marginal Mandibular Branch of the facial nerve: clinical significance for the Plastic Surgeon. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41:1223–1228. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjaa368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jose A, Yadav P, Roychoudhury A, Bhutia O, Millo T, Pandey RM. Cadaveric study of Topographic anatomy of temporal and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve in relation to Temporomandibular Joint surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79(2):343. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.