Abstract

Optogenetic techniques permit non-invasive, spatiotemporal, and reversible modulation of cellular activities. Here, we report a novel optogenetic regulatory system for insulin secretion in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived pancreatic islet-like organoids using monSTIM1 (monster-opto-Stromal interaction molecule 1), an ultra-light-sensitive OptoSTIM1 variant. The monSTIM1 transgene was incorporated at the AAVS1 locus in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing. Not only were we able to elicit light-induced intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) transients from the resulting homozygous monSTIM1+/+-hESCs, but we also successfully differentiated them into pancreatic islet-like organoids (PIOs). Upon light stimulation, the β-cells in these monSTIM1+/+-PIOs displayed reversible and reproducible [Ca2+]i transient dynamics. Furthermore, in response to photoexcitation, they secreted human insulin. Light-responsive insulin secretion was similarly observed in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs produced from neonatal diabetes (ND) patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Under LED illumination, monSTIM1+/+-PIO-transplanted diabetic mice produced human c-peptide. Collectively, we developed a cellular model for the optogenetic control of insulin secretion using hPSCs, with the potential to be applied to the amelioration of hyperglycemic disorders.

Keywords: optogenetics, monSTIM1, pancreatic islet-like organoid, light-induced insulin secretion

Graphical abstract

Han, Heo and colleagues applied optogenetic Ca2+ regulatory module monSTIM1 to human pluripotent stem cell-derived islet-like organoids to establish a photoinducible insulin secretion model. Instead of preexisting studies based on the rodent model or immortalized cells, this study suggests an advanced scheme exploiting optogenetics for personalized diabetes cell therapy.

Introduction

Optogenetic techniques have been employed in the manipulation of a wide range of biological processes, including neuronal action potentials, protein-protein interactions, protein localization, and gene expression.1,2,3 These techniques are particularly attractive due to their non-invasive nature and quick reversibility in regulating biological activities. Diverse optogenetic regulation strategies have been developed by harnessing specific photosensitive proteins with varied characteristics, including the microbial ion pump channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2),4 photoactivatable cyclases,5 light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) sensors,6 cryptochrome,7 and phytochrome.8 The single-component optogenetic module Opto-Stromal interaction molecule 1 (OptoSTIM1) is designed to spatiotemporally modulate intracellular calcium ion levels ([Ca2+]i) in various biological model systems such as human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), zebrafish, and mice.9 Upon exposure to light, cytoplasmic OptoSTIM1 oligomerizes, activating the endogenous calcium release activated channel (CRAC) Orai1. Recently, monSTIM1, an OptoSTIM1 variant, was developed by introducing an E281A mutation and nine additional amino acids to OptoSTIM1’s PHR domain.10 This further improved its light sensitivity and activation kinetics in regulating [Ca2+]i.

Diabetes mellitus arises from insulin deficiency and insulin resistance caused by functional failure or loss of pancreatic β-cells. Along with conventional diabetes therapies such as drug administration and insulin injection, several optogenetic tools for inducing insulin secretion have been developed to manage blood glucose levels in diabetic model systems. Insulin exocytosis in pancreatic β-cells occurs in recqsponse to increases in [Ca2+]i triggered by stimulatory ligands, such as glucose, neurotransmitters, lipids, and incretin hormones.11,12,13 In previous studies, ChR2 has been used to trigger insulin release via optical stimulation,14,15 despite its insufficient ion selectivity. Recently, another group attempted to use optogenetic manipulation of islet-innervating cholinergic neurons via ChR2 to regulate blood glucose homeostasis.16 Others have attempted a more indirect approach to induce insulin secretion by photo-activating cAMP signaling in engineered cells transplanted into diabetic mice.17,18 Insulin expression has been optogenetically induced in diabetic mice transplanted with engineered cells expressing optogenetic transcription modulators such as the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-based LuminON system,19 the far-red light-inducible cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-di-GMP)-mediated system,20,21 and the green light-operated Glow Control system.22 Thus far, however, no one has achieved optogenetic regulation of insulin secretion in human pancreatic endocrine cells, a development that would be more directly applicable to the treatment of diabetes patients.

If successful, transplanted β-cells can strictly and consistently control blood glucose levels.23,24 In this context, pancreatic β-cells generated from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) are an attractive alternative for diabetes therapy.25,26,27,28,29 Still, there are several limitations to this approach, namely the reduced functionality, maturity, and differentiation efficiency of hPSCs.30 We previously reported that pancreatic islet-like organoids (PIOs) developed from hPSCs show β-cell functions, such as glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in vitro and blood glucose regulation in diabetic mice after transplantation.31 In this study, we sought to combine our PIOs with the monSTIM1 system to determine whether we could achieve optogenetic regulation of insulin secretion in hPSC-derived PIOs.

To achieve stable photoactivation of the CRAC channel, we used a CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genomic knockin method to insert a monSTIM1-expression construct into the adeno-associated virus integration site 1 (AAVS1) genomic locus of hPSCs. Upon photostimulation, homozygous monSTIM1+/+-hPSCs showed reversible intracellular Ca2+ influx. We then induced the differentiation of these cells into pancreatic endocrine cells and subsequently PIOs using our previously published protocol.31 Putative β-cells in the monSTIM1+/+-PIOs showed rapid and reversible intracellular Ca2+ influx and insulin secretion upon blue light stimulation. We also found that monSTIM1+/+-PIOs produced from neonatal diabetes mellitus (ND) patient-derived iPSCs (ND-iPSCs) showed similar insulin secretion upon photostimulation. Furthermore, LED-induced release of human c-peptide was detected in the blood of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced type 1 diabetic (T1D) mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. Our development of an optogenetic technique for inducing human insulin secretion in hPSC-derived PIOs has significant implications for the treatment of diabetic patients.

Results

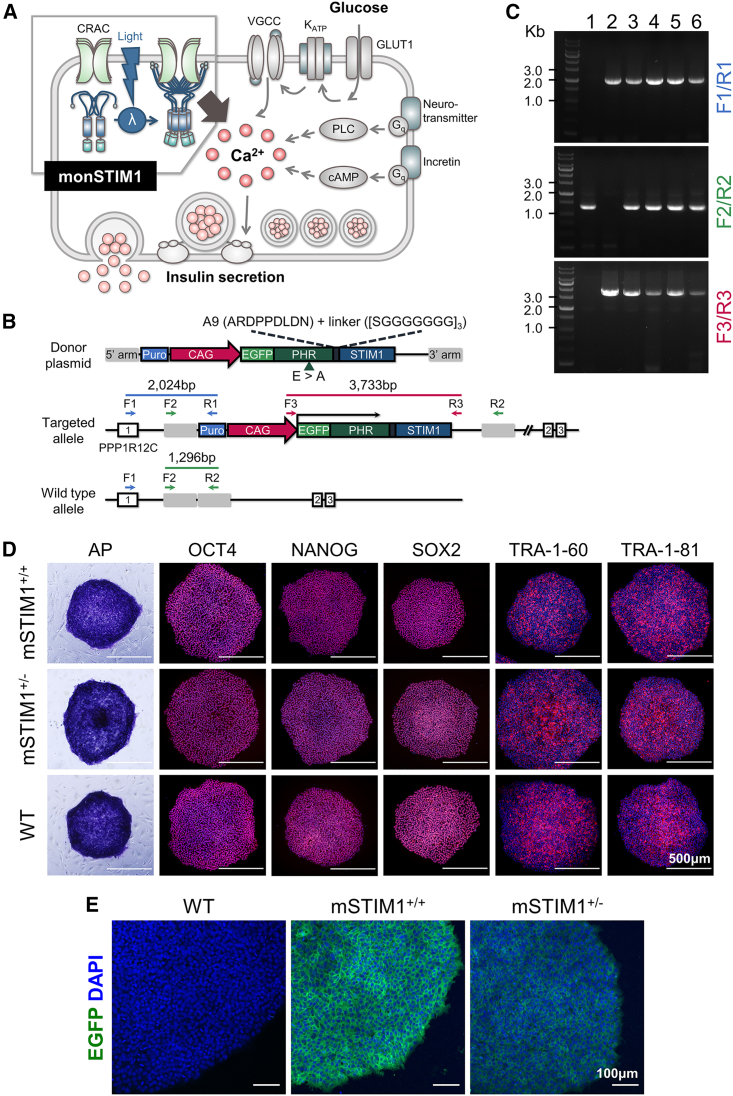

Generation of monSTIM1-knock-in H1 hESCs

To generate pluripotent stem cells that could be regulated by light, we inserted monSTIM1 into the AAVS1 locus of H1 hESCs using a CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockin strategy. After cloning the coding sequence of monSTIM1 into a donor plasmid containing an HDR (homology-directed repair) cassette with AAVS1 homology arms (Figure 1B), we co-transfected H1 hESCs via electroporation with donor plasmids, Cas9 expression plasmids, and guide RNA (gRNA) plasmids targeting the AAVS1 locus. After puromycin selection, we used PCR to individually genotype transfected cell clones, confirming monSTIM1 insertion into the AAVS1 locus. Bands arising from primer set I (F1/R1) detected the genomic stretch from an exon of PPP1R12C to the puromycin-coding region of HDR cassette and indicated successful construct knockin, while bands arising from primer set III (F3/R3) indicated incorporation of the monSTIM1 construct. Primer set II (F2/R2), spanning the left and right homology arms, was used to determine the zygosity of each clone. We found one homozygous monSTIM1-knockin cell clone, with the rest remaining heterozygous (Figure 1C). We used the one homozygous line (lane 2, monSTIM1+/+-H1) as well as one of the heterozygous lines (lane 6, monSTIM1+/−H1) for subsequent experiments. Like wild-type (WT)-H1 hESCs, both monSTIM1-knockin cell lines expressed pluripotency markers (i.e., OCT4, NANOG, SOX2, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81) and were positive for alkaline phosphatase activity (Figure 1D). As expected, the homozygous monSTIM1+/+-H1 line showed stronger EGFP expression than the heterozygous monSTIM1+/−H1 line (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Generation of monSTIM1-knock-in hESCs

(A) Schematic role of monSTIM1 upon photostimulation in pancreatic β-cells. In addition to glucose, insulin secretion is also triggered by other signaling molecules, including incretin hormones and neurotransmitters, via Ca2+ influx into β-cells. In this study, we designed a system using monSTIM1 in hPSC-derived β-cells to trigger light-induced insulin secretion. (B) Genetic structure of the constructs used for HDR at the AAVS1 locus. The locations of the primers used for genotyping the transfected hESC clones are depicted as arrows. A9, synthetic 9 amino acid sequences; CAG, cytomegalovirus (CMV) enhancer/chicken beta-actin promoter; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; F, forward primer; PHR, PHR domain of cryptochrome 2; PPP1R12C, protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 12C; Puro, puromycin resistance sequence; R, reverse primer; STIM1, cytoplasmic domain of stromal interaction molecule 1. (C) Genotyping transfected hESC clones. One homozygous (lane 2) and four heterozygous (lanes 3 to 6) monSTIM1-knockin hESC clones were identified by genomic PCR. WT-hESCs were used as a negative control (lane 1). (D) Normal expression of pluripotency markers in monSTIM1+/+- and monSTIM1+/−H1 hESCs. AP, alkaline phosphatase activity; mSTIM1, monSTIM1. Scale bars, 500 μm. (E) Strong expression of EGFP in homozygous monSTIM1-hESCs. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Photoactivation of Ca2+ influx in monSTIM1-H1 hESCs

To determine whether endogenous CRAC channels can be activated in monSTIM1-H1 hESCs to produce intracellular Ca2+ transients upon 488-nm blue light stimulation, we stained monSTIM1-H1 hESCs with X-rhod-1-AM and then exposed them to blue light for 1 min at an 8.33% duty cycle (1-s pulses at 0.083 Hz). To confirm that the light-induced Ca2+ signals arose in a CRAC-dependent manner via monSTIM1, we treated monSTIM1-H1 hESCs with the CRAC channel blocker SKF96365 for 90 min before live-cell imaging. While homozygous monSTIM1+/+-H1 produced strong Ca2+ signals in response to light, those subjected to CRAC channel inhibition did not (Figure 2A). We found that light stimulation induced synchronous Ca2+ transients across all monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells. Despite slight variations in the response dynamics between single cells, [Ca2+]i reached its peak within 200–250 s from the light onset, gradually falling to half-maximum in 650–900 s (Figure 2A, left graph, upper panel). Heterozygous monSTIM1+/−H1 showed light-induced Ca2+ signals that peaked at a level ∼1.5-fold lower than those of the homozygous cell line (Figure 2B). Thus, the level of light-induced Ca2+ influx depended on the level of monSTIM1 expression. Together, our results indicate that the light-induced Ca2+ influx in monSTIM1-H1 hESCs occurs via endogenous CRAC channels. When designing systems for optogenetic regulation, pulsatile stimulation is preferable to constant illumination because constant illumination can lead to phototoxicity and oxidative stress.32,33 We found no significant difference in the [Ca2+]i dynamics of monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells receiving constant irradiation (100% duty cycle) or pulsatile illumination (1 s ON and 11 s OFF, 8.33% duty cycle) (Figure S1). We therefore decided to adopt a pulsatile stimulus as the basal stimulatory protocol.

Figure 2.

Light-induced activation of Ca2+ influx in monSTIM1-H1 hESCs

(A) Homozygous monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells responding to blue light. monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells exhibited light-induced [Ca2+]i transients in a CRAC-dependent manner. The left panels show representative snapshots of monSTIM1 (EGFP) expression, as well as Ca2+ signals detected by X-rhod-1-AM staining before (Dark) and after (Light) photostimulation in the absence (−) or presence (+) of the CRAC channel inhibitor SKF96365. The right panels show a quantification of individual cell Ca2+ signal traces in time-lapse images (n = 26 cells) taken during the photostimulation sequence described in Table S4-1. The fluorescence intensity of each cell was normalized by its intensity at t = 0. Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Heterozygous monSTIM1+/−H1 responding to blue light. The right panels show a quantification of time-lapse images (n = 27 cells) taken during the photostimulation sequence described in Table S4-1. Heterozygous monSTIM1+/−H1 showed weaker light responses than their homozygous counterparts. (C) Reversible and repetitive [Ca2+]i transients in monSTIM1+/+-H1 hESCs (n = 23 cells). WT-H1 hESCs (n = 33 cells) did not respond to repetitive light stimulation. Upper panel shows representative time-lapse images of the respective cells, and lower panels show quantification of individual cell Ca2+ signal trace in images obtained in WT-hESCs and monSTIM1+/+-H1 hESCs, respectively. The conditions for repeated photoexcitation are shown in Table S4-3. The fluorescence intensity of each cell was normalized by its intensity at t = 0. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Next, we asked whether the light-induced Ca2+ influx in monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells was reversible. When we gave three 60-s light stimulations at 20-min intervals, we found that monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells, but not WT-H1 cells showed repetitive [Ca2+]i dynamics with light ON and OFF signals (Figure 2C, Video S1). Thus, [Ca2+]i in monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells can be regulated reversibly and repetitively by optical stimulation, entering via endogenous CRAC channels.

Representative time-lapse images of WT- (left) and monSTIM1+/+- (right) H1 hESCs in Figure 2C. The video only shows [Ca2+]i transients represented by X-rhod-1-AM signals. Serial images were captured every 11 s while the cells were sequentially stimulated as described in Table S4-3. This is indicated with white text (Light+) in the movie. Scale bar, 20 μm.

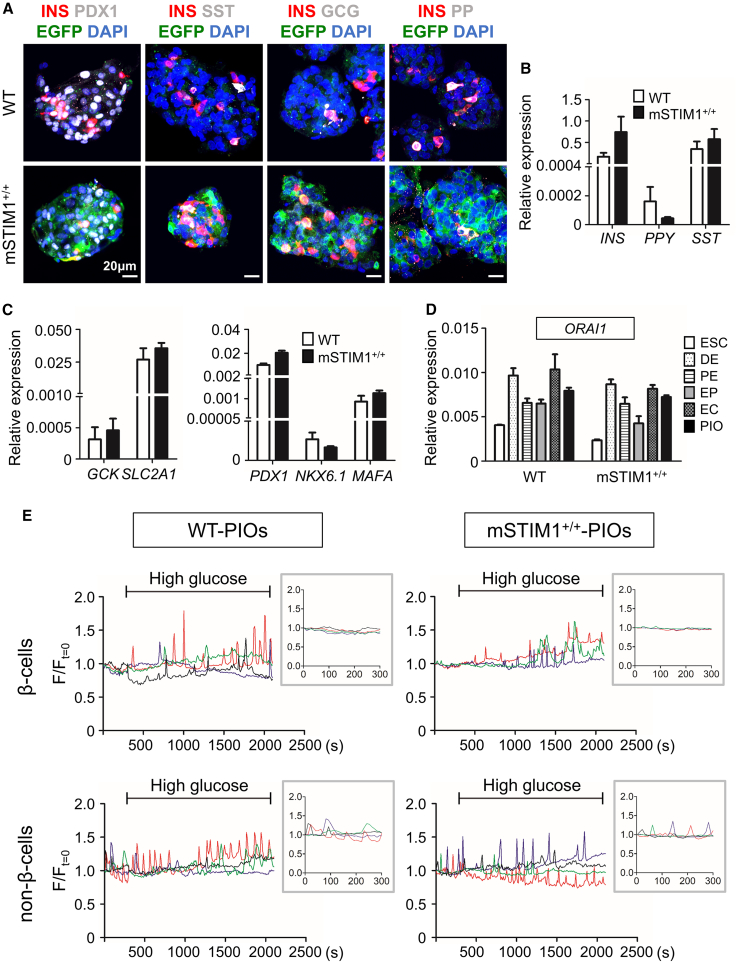

Differentiation of monSTIM1+/+-H1 hESCs into functional PIOs

To determine whether the light-inducible [Ca2+]i transients persist in differentiated cells, we differentiated monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells into PIOs following the protocol depicted in Figure S2A. During differentiation, the monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells developed definitive endoderm (DE), pancreatic endoderm (PE), endocrine progenitors (EP), and endocrine cells (ECs) expressing the appropriate marker genes associated with each developmental stage (Figures S2B and S2C). Like WT-PIOs, we found monSTIM1+/+-H1-derived PIOs expressed pancreatic endocrine hormones such as insulin (INS), somatostatin (SST), and pancreatic polypeptide (PP) (Figure 3A). WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs produced similar mRNA levels for the endocrine hormone genes, β-cell-associated transcriptional factor genes, and β-cell function-related genes we measured (Figures 3B and 3C). Thus, monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells showed normal developmental competence to produce pancreatic ECs and PIOs. In addition, WT- and monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells also produced a similar transcription pattern of the endogenous CRAC component ORAI1 through the various pancreatic developmental stages (Figure 3D). Since WT- and monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells also exhibited similar transcriptional profiles throughout the pancreatic development process for the other voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) involved in β-cell GSIS-related Ca2+ currents (Figure S2D), we concluded that the transformed cells express normal levels of VGCCs.

Figure 3.

Normal development of monSTIM1+/+-H1 hESCs into functional PIOs

(A) Expression of pancreatic endocrine hormones and a β-cell-associated transcription factor (PDX1) in WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. GCG, glucagon; INS, insulin; PP, pancreatic polypeptide; SST, somatostatin. Scale bars, 20 μm. (B and C) Transcriptional expression of β-cell-associated genes in WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs express similar levels of endocrine hormone genes (B) and β-cell-associated genes (GCK, SLC2A1, PDX1, NKX6.1, MAFA) (C). Relative expression levels are presented as means ± SEM (n ≥ 3). (D) WT- and monSTIM1+/+-H1 cells express the endogenous CRAC component ORAI1 at similar levels in each stage of pancreatic development. Relative expression levels are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). (E) Glucose-induced [Ca2+]i transients in WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. The gray-box is a magnified region of the timeline just before high glucose stimulation (from 0 to 300 s) in each experiment. Both WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs contain functional β-cells and non-β-cells. The fluorescence intensity of each cell was normalized by its intensity at t = 0. The colored lines indicate the Ca2+ signals of individual cells.

The ECs of pancreatic islets exhibit different [Ca2+]i response patterns upon glucose stimulation according to cell type.34,35,36 β-cells show a characteristic [Ca2+]i response that, while silent at low glucose levels, increases greatly in the presence of high glucose. Here, we confirmed that, as with WT-PIOs, the putative functional β-cells of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs showed reduced [Ca2+]i in low glucose and increased [Ca2+]i in high glucose (Figure 3E, upper panels). We also observed non-β-cells exhibiting [Ca2+]i oscillations before the onset of high glucose stimulation in both WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs (Figure 3E, lower panels). These results demonstrate that monSTIM1+/+-PIOs contain functional β-cells with typical glucose responsiveness as well as non-β-cells.

Light-induced [Ca2+]i transients in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs

To determine whether functional β-cells in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs exhibit light-induced [Ca2+]i transients, we exposed monSTIM1+/+-PIOs to 488-nm light in an 8.33% duty cycle on a confocal laser microscope for 12, 36, or 60 s. To discriminate which cells in the monSTIM1+/+-PIOs were functional β-cells, we treated the tissue with high glucose (27.5 mM) for 20 min after recording light-induced [Ca2+]i signals. As a result, while the monSTIM1+/+-β-cells showed Ca2+ influx in response to photostimulation, the control WT-β-cells did not (Figure 4A). We also found that the [Ca2+]i signal dynamics upon light stimulation varied among the functional monSTIM1+/+-β-cells in which some did not exhibit light-induced [Ca2+]i transients (Figure S3A). We noted that the proportion of responsive β-cells was highest in the 60-s photoexcitation group (Figure S3B), suggesting the possibility that some silent functional monSTIM1+/+-β-cells can be activated by longer light exposures. Video S2 is a representative time-lapse movie of [Ca2+]i transients observed in responsive monSTIM1+/+-β-cells. Our results thus indicate that monSTIM1+/+-PIOs contain a heterogeneous population of functional β-cells, some of which respond to light.

Figure 4.

Blue light-induced [Ca2+]i transients in β-cells of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs

(A) [Ca2+]i transients in β-cells of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs upon photostimulation. WT- and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs were stimulated with blue light for 12, 36, and 60 s during measurement of β-cell [Ca2+]i transients, respectively. The photoexcitation protocols are indicated in Table S4-4. Each colored line indicates a single cell Ca2+ signal trace. The relative fluorescence intensity of each cell was obtained as described in the materials and methods. (B) Temporal responsiveness of monSTIM1+/+-β-cells to light. The repeated photoexcitation protocols are indicated in Table S4-5. Light-responsive monSTIM1+/+-β-cells were categorized into repetitive (above) and non-repetitive groups (below). Each colored line indicates the changes in an individual cell’s Ca2+ signal. The relative fluorescence intensity of each cell was obtained as described in the materials and methods.

Representative time-lapse images of the WT- (left) and monSTIM1+/+- (right) PIOs in Figures 4A and S3A. The video only shows [Ca2+]i transients represented by X-rhod-1-AM signals. Functional β-cells of the PIOs discriminated by their glucose response pattern are indicated with white arrows. Serial images were captured every 11 s while the cells were stimulated as described in Table S4-4. This is indicated with white text (Light+, High glucose) in the movie. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Next, we asked whether the [Ca2+]i transients of light-responsive monSTIM1+/+-β-cells are repetitively reversible by stimulating monSTIM1+/+-PIOs with light three times at 15-min intervals for 60 s each. We found 38.5% of light-responsive monSTIM1+/+-β-cells showed [Ca2+]i transient reversibility upon repeated light stimulation, while the remaining 61.5% showed more ambiguous response patterns (Figure 4B). Video S3 shows a representative time-lapse movie of [Ca2+]i transients observed in monSTIM1+/+-β-cells responding repeatedly to light. Thus, our results indicate that [Ca2+]i transients can be induced in monSTIM1+/+-β-cells repeatedly and reversibly in response to light, despite some heterogeneity in their populations.

Representative time-lapse images of the monSTIM1+/+-PIO in Figure 4B. The video only shows [Ca2+]i transients represented by X-rhod-1-AM signals. Functional β-cells of the PIOs were discriminated by their glucose response pattern and are indicated with white arrows. Serial images were captured every 11 s while the cells were stimulated as described in Table S4-5. This is indicated with white text (Light+, High glucose) in the movie. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Light responsiveness of insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs

Finally, we asked whether the light-induced [Ca2+]i transients we triggered in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs were also associated with insulin secretion. We found that monSTIM1+/+-PIOs in low glucose showed increased insulin secretion upon light stimulation to levels comparable to those exposed to high glucose in the dark (Figure 5A), but the combination of light and high glucose did not produce a synergic effect. We also found monSTIM1+/+-PIOs repeatedly secreted insulin upon repetitive photoexcitation (8.33% duty cycle for 60 s as one unit) over the course of an hour at intervals of 9, 19, or 29 min (Figure S4A). Those results show that while WT-PIOs secrete human insulin only in response to high glucose (Figure S4B), monSTIM1+/+-PIOs also secrete insulin in response to light.

Figure 5.

Light-induced insulin secretion from monSTIM1+/+-PIOs

(A) Light-induced secretion of human insulin from monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. The secreted insulin level (%) for each group before and after stimulation (glucose or light) was normalized by the total insulin level of the PIO. L and H indicate low glucose (2.5 mM) and high glucose (27.5 mM), respectively (n = 4). (B) Kinetic profile of light-induced insulin secretion. WT and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs were either photostimulated for 1 min (+Light) or kept in the dark at different glucose concentrations (L or H). Supernatant was serially collected from each culture to measure the accumulation of secreted insulin at 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 min after stimulation (n = 3). The insulin secretion rate (%/min) at each time point was calculated by dividing the increased amount of the insulin secretion by the elapsed time (upper panel). The lower panel shows the accumulation of the secreted/total insulin (%). (C) Reversibility of light-induced insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs (n = 6). Activation of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs was reversible when activated at 6, 12, and 24 h after the first stimulation (t = 0). (D) Daily reversibility of light-induced insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs (n = 6). Relative insulin levels at each time point in (C) and (D) are shown as a fold change between the secretion level in the light group vs. the dark group. All data are presented as means ± SEM. p values in (A), (C), and (D) were determined using paired Student’s t tests. ∗0.01 < p < 0.05, ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗∗∗0.0001 < p < 0.001. Stimulation schedules (glucose or light) appear above the graphs.

To examine the kinetics of light-stimulated insulin secretion, we measured the rate at which secreted insulin accumulated in WT and monSTIM1+/+-PIOs after stimulation. The insulin secretion rate in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs stimulated with a single dose of illumination (8.33% duty cycle for 60 s) was faster than that of normal GSIS in WT-PIOs within 10 min (Figure 5B, upper graph). Notably, monSTIM1+/+-PIOs photostimulated in high glucose showed slower insulin secretion within 20 min. These unusual kinetics may be due to a reciprocal interaction between monSTIM1-mediated secretion and native GSIS. Regardless, the total amount of secreted insulin was similar among the three groups (Figure 5B, lower graph). Next, we investigated insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs exposed to repetitive photoexcitation. The insulin secretion of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs upon repetitive photoexcitation was reproducible at intervals of 6, 12, or 24 h (Figure 5C), and upon repeated daily exposure to light (Figure 5D). In addition, monSTIM1+/+-PIOs showed similar levels of light-induced insulin release when stimulated at 3-h intervals (Figure S4C). Together, our data indicate that the insulin secretion of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs can be reversibly and repeatedly controlled by photoexcitation with faster kinetics.

Optogenetic insulin secretion in ND-PIOs expressing monSTIM1

To assess the clinical applicability of our optogenetic regulatory system for insulin secretion, we performed a knockin of monSTIM1 into the AAVS1 locus of iPSCs derived from an ND patient (Figure 6A). This ND patient had a heterozygous mutation of KCNJ11, the gene that encodes the pore-forming Kir6.2 subunits of the ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel.37 Using PCR, we selected a homozygous monSTIM1-positive clone derived from ND-iPSCs (monSTIM1+/+-ND) (Figure S5A) that also showed normal expression of pluripotency-associated markers (Figure S5B). To confirm the nature of these monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs, we confirmed the presence of the patient’s original heterozygous KCNJ11 mutation (Figure S5C). As with monSTIM1+/+-H1 (Figure 2A), we verified that monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs showed stable expression of EGFP (Figure 6B) and light-inducible [Ca2+]i transients dependent on endogenous CRAC channels (Figure 6C). We also confirmed that monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs (Figure 6D and Video S4) but not untransformed ND-iPSCs (Figure S5D) reversibly and repeatedly produced light-induced [Ca2+]i transients. These results indicate [Ca2+]i transients in ND-derived pluripotent stem cells can be controlled via photostimulation. We were able to differentiate both ND- and monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs through the various pancreatic developmental stages (Figure S6A), eventually producing PIOs (Figures 6E and S6B).

Figure 6.

Optogenetic insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs

(A) Schematic workflow for generating monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs. (B) Expression of EGFP in homozygous monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Homozygous monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs responding to blue light. Like monSTIM1+/+-H1 hESCs, monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs exhibited light-induced and CRAC-dependent [Ca2+]i transients. The left panels show representative images of monSTIM1 (EGFP) expression, as well as Ca2+ signals detected by X-rhod-1-AM staining before (Dark) and after (Light) photostimulation in the absence (−) or presence (+) of SKF96365. The right panels show a quantification of time-lapse images acquired during the photostimulation sequence described in Table S4-1. The fluorescence intensity of each cell was normalized to its intensity at t = 0 (n = 27 cells). Scale bars, 20 μm. (D) Reversible and repetitive [Ca2+]i transients in monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs. The protocols for repeated photoexcitation are presented in Table S4-3. The fluorescence intensity of each cell was normalized to its intensity at t = 0 (n = 29 cells). (E) Expression of pancreatic β-cell-associated markers in ND- and monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs. Scale bars, 20 μm. (F) Insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs induced by light stimulation. Non-transformed ND-PIOs did not secrete human insulin in response to any of the stimuli tested (left panel, n = 6). monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs secreted insulin in response to blue light, but not high glucose (right panel, n = 7). The relative insulin level of each group is presented as a fold change between the insulin levels secreted before and after stimulation, and all data are presented as means ± SEM. p values were determined using paired Student’s t tests. ∗0.01 < p < 0.05.

Representative time-lapse images of the ND- (left) and monSTIM1+/+- (right) ND-iPSCs in Figures 6D and S5D. The video only shows [Ca2+]i transients represented by X-rhod-1-AM signals. Serial images were captured every 11 s while the cells were sequentially stimulated as described in Table S4-3. This is indicated with white text (Light+) in the movie. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Next, we examined the functionality of ND-PIOs. Although ND-PIOs never showed enhanced insulin secretion in response to either high glucose or light stimulation (Figure 6F, left graph), monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs showed increased insulin secretion upon photoexcitation (8.33% duty cycle for 1 h) even in the absence of glucose stimulation (Figure 6F, right graph). Since this patient iPSC model carries an autosomal dominant KATP channel mutation, these results imply that the light-induced insulin secretion of monSTIM1+/+-ND-PIOs is independent of the canonical KATP channel. Together, we have demonstrated the applicability of this monSTIM1-based optogenetic system to the controlled secretion of insulin in hypoinsulinemic diabetes.

Photostimulation-induced secretion of human insulin in diabetic mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs

We finally assessed the capability of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs for light-inducible insulin secretion in diabetic mice (Figure 7A). For this, pouches of fibrous polycaprolactone (PCL) membrane were employed to immobilize the monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. Prior to transplantation into the diabetic mice, we asked whether PCL-encapsulated monSTIM1+/+-PIOs (PIO implant) secrete insulin upon photostimulation in vitro. The encapsulated-monSTIM1+/+-PIOs secreted more insulin under a 470-nm LED array than in the dark (Figure 7B). After that, each monSTIM1+/+-PIO implant was subcutaneously transplanted into the dorsal region of a T1D mouse (Figure 7C, left panel). At 3 or 4 days after transplantation, the mouse was exposed to blue light in the home cage with an LED array lid for 2 h (Figure 7C, right panel, Video S5). We detected human c-peptide in the blood of diabetic mice that received monSTIM1+/+-PIOs under LED illumination in their home cage, just like in the positive control group that received an intraperitoneal glucose injection (Figure 7D). To determine whether the light-induced secretion of human insulin can regulate blood glucose levels in diabetic mice, we conducted an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) under the same illumination conditions. Unlike in the dark, we found illumination triggered a significant decrease of blood glucose levels in diabetic mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs (Figure 7E). As control groups, the blood glucose levels of WT mice and STZ-induced diabetic mice in a hyperglycemic state are depicted in Figure S7. In addition, we measured the expression of β-cell markers, including insulin and glucose transporter protein glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), in autopsied implants (Figure S8). These results indicate functional β-cells in the transplanted monSTIM1+/+-PIOs secreted human c-peptide upon optical stimulation in vivo. Collectively, our findings demonstrate the feasibility of our optogenetic system for controlling the secretion of human insulin in diabetic mouse models.

Figure 7.

Light-induced insulin secretion in diabetic mice that received monSTIM1+/+-PIO transplants

(A) Overall experiment schematic for testing our optogenetic system in diabetic mice. (B) Insulin secretion in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs-encapsulated PCL sheet induced by light stimulation in vitro. The relative insulin level of each group is presented as a fold change between the insulin levels secreted before and after photostimulation. All data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). p values were determined using paired Student’s t tests. ∗0.01 < p < 0.05. (C) Transplantation of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs-encapsulated PCL sheets (PIO implants) into diabetic mice and the home cage with an LED lid. A ∼1 cm2 PIO implant was subcutaneously transplanted into the dorsal region of a diabetic mouse (left). Right panel is a representative picture of a mouse receiving blue light stimulation in the home cage with an LED lid. (D) Light-stimulated secretion of human c-peptide in the serum of diabetic mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. At 3–4 days after PIO transplantation, human c-peptide was measured from the blood of the mouse after illumination in the LED home cage. All data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 7 or 5 mice for respective cohorts). p values were determined using paired Student’s t tests. ∗0.01 < p < 0.05, ∗∗0.001 < p < 0.01. (E) Glucose tolerance of diabetic mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. Blood glucose levels for mice under the indicated light condition (light and dark) measured at 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after intraperitoneal glucose injection (2 g/kg body weight), and all data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6 mice). p values were determined using unpaired Student’s t tests. ∗0.01 < p < 0.05.

PIO-transplanted mouse receiving the blue light illumination in the LED homecage. Mouse is freely moving in the cage during the photostimulatory period (2 h).

Discussion

Here, we report a human cellular model that incorporates a light-inducible system for insulin secretion from hPSC-derived PIOs. Briefly, after generating monSTIM1+/+-hESCs, we guided their differentiation into pancreatic ECs and PIOs. We then confirmed that monSTIM1+/+-PIOs produce [Ca2+]i transients and secrete human insulin upon photoexcitation independent of the canonical KATP channel. Moreover, diabetic mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs produced human c-peptide in response to light stimulation. Thus, it is conceivable that a combination of hPSC technology and this light-inducible system could be used to regulate insulin secretion in diabetic patients.

OptoSTIM1-expressing hESCs generated via lentiviral infection exhibit fast and reversible [Ca2+]i increases in response to light stimulation.9 These cells, however, have limitations, including heterogeneity and a gradual silencing of OptoSTIM1 expression during cellular passaging and differentiation. To circumvent these limitations, we used the CRISPR-Cas9 technology to insert monSTIM1 (i.e., an improved OptoSTIM1) into the AAVS1 region of the hPSC genome (Figures 1B and 1C). The AAVS1 locus is widely targeted as a safe-harbor site for the stable expression of foreign constructs in hPSCs.38,39,40 The resulting monSTIM1+/+-hPSCs showed consistent and homogeneous expression of monSTIM1 despite long-term culture in vitro through 40 to 60 culture passages (data not shown). These cells also developed normally into PIOs with strong monSTIM1 expression and functional β-cells capable of insulin secretion.

Several attempts have been made to control insulin production in cell lines and in mice by optical stimulation.14,15,16,17,18,19,41 These can be classified as indirect methods, such as induction of insulin secretion by transcriptional activation17,19,20,21,22 or by activating islet-innervating neurons,16 and direct methods using optogenetic tools, such as ChR2 and bPAC.14,15,18,41 In bPAC-based systems, light induces activation of cAMP signaling, which can then be used to potentiate glucose-dependent insulin secretion.42,43 In ChR2-based systems, insulin secretion is triggered more directly in a glucose-independent manner via an influx of diverse cations. ChR2 shows a strong preference for the monovalent cations H+ and Na+ rather than the divalent ions Ca2+ and Mg2+.44,45 This preference, however, can cause unnecessary perturbations in physiological cues because the ions can alter membrane potential and intracellular pH. In contrast, CRAC channels show a strong preference for Ca2+.46 This is why we chose the endogenous CRAC-dependent monSTIM1 system to produce the light-induced [Ca2+]i transients that eventually trigger insulin vesicle exocytosis in β-cells.

In this study, we describe a novel system for the light-induced regulation of [Ca2+]i transients in human β-cells. Although control WT-β-cells never showed [Ca2+]i transients upon photoexcitation, monSTIM1+/+-β-cells exhibited clear light-dependent Ca2+ influx (Figure 4A). We did notice some heterogeneity in PIOs among the functional monSTIM1+/+-β-cells that secreted insulin in response to high glucose, with only some responding to light (Figure S3A). β-cells are known to be heterogeneous in murine pancreatic islets in terms of their reactivity to extracellular stimuli.47 Specialized pacemaker cells, referred to as ‘hub cells’, are highly metabolic and relatively immature. These hub cells propagate Ca2+ waves to neighboring “follower” β-cells, which then secrete insulin.48,49 The heterogeneity in light responsiveness among functional monSTIM1+/+-β-cells we observed could also be due to differences in the properties of in vitro-derived and endogenous β-cells. Among the responsive β-cells, we also observed reduced reproducibility of [Ca2+]i transient production after repeated light stimulation (Figure 4B). Functional β-cells interact directly with one another via gap junctions,50 suppressing spontaneous [Ca2+]i transients in low glucose conditions.51 It is therefore likely that gap junctions in functional β-cells can also suppress repetitive Ca2+ influx triggered by light stimulation. In addition, we found a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i upon light stimulation of monSTIM1+/+-β-cells, which occurred more slowly in monSTIM1+/+-ESCs (Figure S9). This difference appears to arise from differential expression of ORAI1 between pluripotent stem cells and β-cells, as shown in Figure 3D. Together, our results indicate monSTIM1 can function as a light-inducible modulator of [Ca2+]i transients in hPSC-derived β-cells despite their heterogeneity.

Here, we have established a model system in which hPSC-derived β-cells secrete insulin upon photoexcitation. Although monSTIM1+/+-PIOs show GSIS, they also secrete insulin via Ca2+ influx in response to blue light with faster kinetics even under low glucose (Figure 5). Compared to their glucose-stimulated [Ca2+]i transients, the light-induced [Ca2+]i transient of monSTIM1+/+-β-cells were relatively prolonged (Figure 4A). It can be speculated that these prolonged [Ca2+]i transients probably cause a potential risk of hypoglycemia in application of the monSTIM1+/+-PIO model to diabetic therapy. Intriguingly, we found monSTIM1+/+-PIOs secreted insulin with much faster kinetics upon a single bout of photostimulation, producing a similar total amount of secreted insulin as GSIS (Figure 5B). Thus, our results demonstrate that photostimulation does not appear to cause sustained insulin release in monSTIM1+/+-PIOs. Unexpectedly, we found photoexcited monSTIM1+/+-PIOs in high glucose showed delayed insulin secretion kinetics (Figure 5B). This implies some sort of interplay between endogenous GSIS and light-stimulated insulin secretion. Recently, the store-operated Ca2+ channels, including CRAC, upon which monSTIM1 relies, are reported to be important in the secretory function of β-cells.52 It is therefore conceivable that in monSTIM1+/+-β-cells under glucose-stimulating conditions, monSTIM1 and endogenous STIM1 may affect one another’s activation of the Orai1 channel, either competitively or cooperatively. In addition, we confirmed the reversibility of our optogenetic system when we found monSTIM1+/+-PIOs exhibit insulin secretion upon repeated light stimulation at 3 h, dietary, or daily intervals (Figures 5C, 5D, and S4C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that our optogenetic control system can dynamically induce insulin secretion from human β-cells.

Next, we asked whether our optogenetic system would work in a diabetes model. After transplanting monSTIM1+/+-PIOs into diabetic mice, we exposed the mice to photostimulation and found human c-peptide in their blood (Figure 7D). Moreover, the blood glucose level of these monSTIM1+/+-PIO-transplanted diabetic mice promptly dropped to the initial level upon light-induced human insulin secretion (Figure 7E). These results confirm the functionality of our optogenetic system in vivo. In clinical trials for engrafting islets or stem cell-derived pancreatic cells into diabetic patients, the transplantation site should be selected carefully while paying attention to several factors, including its vascularization to ensure a proper supply of oxygen and nutrients, its potential for host immune rejection, as well as its surgical accessibility for facilitating further monitoring and retrieval of the transplant.53,54 In our study, we were able to confirm photostimulation-induced human c-peptide secretion and blood glucose regulation in diabetic mice transplanted with monSTIM1+/+-PIOs into the dorsal subcutaneous region (Figures 7D and 7E). Those results demonstrate that subcutaneous transplants can efficiently function in response to the light.

One potential risk of using hPSC-derivatives is the tumorigenicity of the transplants, which can be caused by the presence of undifferentiated cells or by genomic instability in the iPSCs due to the exogenous factors used for cellular reprogramming.55,56 Several approaches have been taken to prevent this, including whole-genome/exome sequencing of the iPSCs to screen out any clones with potentially oncogenic mutations or reprogramming factor remnants,57,58 induction of safety switch or treatment of chemicals that selectively kill the remaining iPSCs hiding among their differentiated progenies,58,59 and using single-cell RT-PCR for purity validation.57 It is also possible that the tumorigenesis of hPSC-derived grafts could be prevented by adjusting the transplantation region. Subcutaneous transplantation facilitates tracking transplantation progress and removal when necessary,53,54 thereby preventing the undesirable invasion of the engrafted cells. Therefore, in the clinical application of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs, subcutaneous transplantation strategy along with a specialized cell encapsulation device and a non-invasive lighting apparatus can be considered.

In addition, several other problems should be addressed before our optogenetic system enters clinical trials. One major obstacle is the low long-term survival of the transplanted cells, which is likely caused either by low vascularization or by attacks from the host’s innate immune system. Therefore, it is of importance to compromise a suitable niche within an encapsulation device to prolong PIO survival. We recommend trials with structural reinforcement via biomaterial scaffolds to promote vascularization or introduce supportive mesenchymal cells.54 Also, it is reported that ChR2-specific immune responses in rats injected with ChR2 can reduce functional protein levels via adaptive immunity.60 Unlike membrane-bound ChR2, monSTIM1 is cytoplasmic. It is a truncated version of STIM1 originally anchored to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane.10 Hence, monSTIM1 might be less susceptible to neutralizing antibodies than ChR2. Still, the potential risk of immunogenicity or genotoxicity of the optogenetic module with a non-human origin must be weighed carefully before clinical application.

Typically, β-cells secrete insulin in a KATP channel-dependent manner to regulate blood glucose homeostasis. To assess the feasibility of our optogenetic approach for the treatment of patients with ND caused by KATP channel mutations, we generated monSTIM1+/+-ND-iPSCs, developed them into PIOs, and then confirmed their light-induced insulin secretion (Figure 6). Although ND patients with KATP channel mutations are generally treated with sulfonylurea drugs, they often experience side effects (e.g., cardiovascular damage) when the drug acts on KATP channels in tissues other than the target pancreatic β-cells.61,62 ND patients with severe KATP channel mutations commonly show limited therapeutic improvement in response to the drugs because of KATP channel cooperativity.63,64 By contrast, optogenetic regulation with monSTIM1 makes it possible to activate pancreatic β-cells specifically and directly for insulin exocytosis, which may allow such patients to overcome the limitations of drug treatment. Our system is particularly appealing for patients with diabetes caused by genetic defects, such as ND and maturity onset diabetes of the young. We also expect that our system can be employed in more fine-tuned cellular therapies for patients with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes by improving the robustness of their glycemic control. In conclusion, we have demonstrated a novel treatment model for diabetes using optogenetic regulation of monSTIM1+/+-PIOs.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

Expression plasmids for Cas9 (pCas9_GFP, #44719 donated by Kiran Musunuru), the gRNA targeting AAVS1 site (gRNA_AAVS1-T2, #41818 donated by George Church), as well as the donor plasmid with AAVS1 site-targeting homology arms for HDR (AAVS1-CAG-hrGFP, #52344 donated by Su-Chun Zhang) were obtained from Addgene (Watertown, MA). The expression plasmid for monSTIM1 (pCMV-monSTIM1) was a gift from Prof. Won do Heo. To generate the AAVS1-CAG-monSTIM1 donor plasmid, the hrGFP cDNA in AAVS1-CAG-hrGFP was replaced with a monSTIM1 cDNA (∼3.7 kb) using the In-Fusion Cloning Kit (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the AAVS1-CAG-hrGFP vector was digested with SalI and MluI (purchased from Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) at 37°C for 2 h, and subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel (LPS solution, Daejeon, Korea) for 30 min followed by gel purification using a DNA purification kit (Cosmo Genetech, Seoul, Korea) to remove the hrGFP construct. PCR amplification of monSTIM1 cDNA was performed using the CloneAmp HiFi PCR Premix (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction conditions are summarized as follows: 98°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 98°C denaturation for 10 s, 55°C annealing for 15 s, 72°C elongation for 4 min 30 s, and then a final 72°C elongation step for 5 min. DNA oligomers 5′-AAAGAATTCGTCGACATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG-3′ and 5′-AGTGAATTCACGCGTCGGTGGATCCCAATTCCTAC-3′ were used as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The pCMV-monSTIM1 plasmid was used as a template. The In-Fusion reaction was carried out with purified PCR products and linearized vector at 50°C for 15 min. The final AAVS1-CAG-monSTIM1 donor plasmid was transformed into Stellar competent cells (Takara Bio), clonally amplified in LB broth (LPS solution), and purified using the NucleoBond Xtra Maxi Plus kit (Macherey-Nagel, Bethlehem, PA).

Cell maintenance and generation of monSTIM1-knockin hPSCs

Studies using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) were performed under the approval of the institutional review board of KAIST (KH2021-191). Undifferentiated hPSCs were maintained on Matrigel in mTeSR medium or on mitomycin C-treated (MMC; A.G. Scientific, San Diego, CA) feeder layers in hPSC medium containing DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Waltham, MA), 20% Knockout Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 10 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and daily media changes. Human PSC colonies were passaged every 5 to 6 days with 10 mg/mL Dispase (Gibco) or 10 mg/mL Collagenase Type IV (Gibco) followed by mechanical slicing of colonies into several sections. ND patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (ND-iPSCs) were generated from dermal fibroblasts of an ND patient provided by Asan Medical Center37 as previously described.65 The single nucleotide mutation of the KCNJ11 gene was identified by direct sequencing using the following primer sets: 5′-TTTTCTCCATTGAGGTCCAAGT-3′ and 5′- AGTCCACAGAGTAACGTCCGTC-3′. H1 (WA01) human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and ND-iPSCs were transfected with Cas9, gRNA, and donor plasmids using the NEON transfection system (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). Human PSCs were dissociated into single cells using Accutase (Millipore, Burlington, MA) and harvested by mild centrifugation (200 × g). The cells (1.25 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 100 μL of pre-warmed R buffer, mixed with 5 μg of DNA (1.25 μg of pCas9_GFP, 1.25 μg of gRNA_AAVS1-T2, 2.5 μg of AAVS1-CAG-monSTIM1), and immediately electroporated with two pulses of 1400 V for 20 ms each according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The electroporated cells were then resuspended in 1 mL of mTeSR medium (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and plated on Matrigel (Corning, New York)-coated four-well plates at a density of 1.25 × 106 cells/well. The cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 5 days with daily media changes until they reached approximately 50% confluence. For antibiotic selection, the cells were incubated in mTeSR medium supplemented with 0.5 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 10 days with daily media changes. The cells were then dissociated into single cells and serially diluted at a minimum density of 10 cells/well in 96-well plates for clonal isolation. Colonies expressing GFP with hPSC morphology were selected, mechanically dissociated from the 96-well plates and transferred to four-well plates. Then, homozygous and heterozygous monSTIM1 colonies were identified by genotyping PCR.

Genotyping PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from each colony using a G-DEX Genomic DNA extraction kit (Intron Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR reactions were performed using Taq Polymerase ver. 2.1 (BioAssay, Daejeon, Korea) and the following protocol: 95°C for 2 min and then 35 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 40 s, 72°C for 20 s, and a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min. The primer sets used for these PCR reactions are listed in Table S1.

Development of hPSCs into PIOs

Human PSCs were developed into islet-like endocrine organoids as previously described.31 Briefly, hPSCs were dissociated into single cells using an EDTA/PBS solution (EDTA; Bioneer, PBS; Gibco), plated onto Matrigel-coated six-well plates at a density of 4–5 × 104 cells/cm2, and cultured in mTeSR medium supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632 for 2 days. To induce definitive endoderm (DE) formation, cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma), 50 ng/mL activin A (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 3 μM CHIR99021 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), and 2 mM lithium chloride (LiCl; Sigma) for 24 h. They were then further cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 0.2% BSA, 50 ng/mL activin A, and 1% B27 supplement (Gibco) for 3 days. The resulting DE cells were incubated in DMEM high-glucose medium (Gibco) supplemented with 0.5% B27 supplement, 2 μM retinoic acid (Sigma), 2 μM dorsomorphin (A.G. Scientific), 10 μM SB431542 (Cayman Chemical), 5 ng/mL FGF2, and 250 nM SANT1 (Cayman Chemical) for 6 days to direct their differentiation into PE cells. To produce EP cells, PE cells were cultured in DMEM high-glucose medium containing 0.5% B27 supplement, 2 μM dorsomorphin, 10 μM SB431542, 10 μM DAPT (Cayman Chemical), and 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma) for 4 days. Those EP cells were then cultured in CMRL-1066 (Gibco) in the presence of 0.5% B27 supplement, 2 μM dorsomorphin, 10 μM SB431542, 10 nM exendin-4 (Sigma), 500 μM dibutyl-cAMP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma), 10 mM nicotinamide (Sigma), 25 mM glucose (Sigma), and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin for 8 days to produce ECs. Finally, the ECs were dissociated into single cells by Accutase treatment, resuspended in the same medium supplemented with Y-27632, and plated on non-coated 96-well plates (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea) at a density of 3 × 105 cells/cm2. The cells were then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 day to generate PIOs.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the Easy-BLUE reagent (Intron Biotechnology). For each reaction, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (BioAssay) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A pre-made 2× mixture comprising 40 mM Tris (pH 8.4, LPS solution, Daejeon, Korea), 0.1 M KCl (Bioneer), 6 mM MgCl2 (Sigma), 2 mM dNTP (BioAssay), 0.2% fluorescein (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 0.4% SYBR Green (Invitrogen), and 10% DMSO (GenDEPOT, Katy, TX) was used for the qRT-PCR reactions. The reactions were performed on a CFX Connect TM Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) with the following reaction protocol: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 39 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55–60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, plate read and melting curve detection. The relative expression of each target gene was determined by its Ct value normalized to that of GAPDH. The primers used in these qRT-PCR analyses are listed in Table S2.

Alkaline phosphatase staining

Alkaline phosphatase staining was performed using the Leukocyte Alkaline Phosphatase kit (Sigma). Briefly, cells were fixed with a fixation solution comprising 1 mL of citrate solution, 2.6 mL of acetone (Junsei Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), and 320 μL of 37% formaldehyde (Sigma). After washing with distilled water, the cells were stained with AP staining solution containing sodium nitrate, FBB-alkaline solution, and naphtol As-BI alkaline solution for 1 h.

Immunofluorescence

Cultured cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Sigma) at 4°C overnight. Fixed cells were washed twice with PBS (Gibco), permeabilized with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) for 30 min, washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), and then blocked with PBST containing 1% BSA (GenDEPOT) at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. Then, the cells were incubated in PBST containing 1% BSA with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After rinsing five times with PBST, the cells were incubated in PBST supplemented with 1% BSA and 1 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with the secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. Then, the cells were mounted onto slide glasses with Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Dako, Santa Clara, CA) and observed on a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The primary and secondary antibodies used, as well as their dilution ratios, are listed in Table S3.

Calcium imaging

Live-cell Ca2+ imaging was done in human PSCs or PIOs. The cells were plated onto Matrigel-coated 24-well glass-bottom plates (Cellvis, Mountain View, CA) 1 day before imaging. For hPSC imaging, cells were incubated in mTeSR medium supplemented with 2 μM of X-rhod-1-AM (Invitrogen) plus 0.02% Pluronic F-127 (Invitrogen) for 30 min. After removing the residual dye, the cells were incubated for 15–30 min before imaging. To test CRAC channel activity, monSTIM1-knock-in hPSCs were pre-treated with 50 μM of SKF96365 (Sigma) for 90 min before imaging. For imaging PIOs, the cells were pre-incubated in KRBH-BSA containing 2.5 mM glucose (Gibco) for 30 min. KRBH (Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate with HEPES)-BSA buffer contains 115 mM NaCl (Sigma), 24 mM NaHCO3 (Sigma), 5 mM KCl (Junsei Chemical), 2.5 mM CaCl2 (Junsei Chemical), 1 mM MgCl2 (Junsei Chemical), and 25 mM HEPES (Sigma) supplemented with 2% BSA (Sigma). The cells were incubated in KRBH-BSA buffer containing 2 μM of X-rhod-1-AM, 0.02% Pluronic F-127, and 2.5 mM glucose for 30 min. Then, the cells were further incubated for 30 min in KRBH-BSA containing 2.5 mM glucose before imaging. To observe glucose-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations during imaging, PIOs were exposed to 2.5 mM glucose for 5 min and then 27.5 mM glucose for 30 min. Blue light excitation was delivered with the 488-nm laser module on a Nikon A1 confocal microscope at a power intensity of 204.5 μW/mm2 (as measured with an optical power meter from Advantest, Tokyo, Japan). The serial photoexcitation conditions are listed in Table S4. Time-lapse images were acquired using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) mounted on a Nikon Eclipse Ti body equipped with a Nikon CFI Apochromat Lambda S objective (×60, 1.4 numerical aperture; Nikon Instruments). The environmental conditions for live-cell imaging—37°C and 5% CO2—were adjusted and maintained using a Chamlide TC system (Live Cell Instrument, Seoul, Korea).

Analysis of the time-lapse images

All time-lapse images were analyzed with imaging software NIS Elements version 4.60 (Nikon Instruments). For quantification of the images, whole cells were designated as regions of interest (ROIs) and continuously tracked using the TrackingROIEditor() function of the imaging software. Time-lapse fluorescence intensity of each ROI was measured with the Time measurement function. Relative fluorescence intensity values (F) for hPSCs and glucose-stimulated PIOs, were determined by normalizing the fluorescence intensity at a designated time (Ft) to the basal fluorescence intensity measured at t = 0 (F0). Relative fluorescence intensity values (F) for the photoexcitation of β-cells, were calculated using both basal (F0) and maximum fluorescence intensities measured during the imaging process (Fmax).

Light stimulus and insulin secretion assay on hPSC-derived PIOs

After washing with KRBH containing 5 mM glucose, PIOs were incubated in KRBH buffer containing 2.5 mM glucose for 2 h. Then, the PIOs and KRBH buffer (100 μL) with 2.5 mM or 27.5 mM glucose were placed into each well of a 96-well or 24-well black plate (SPL Life Sciences). For blue light stimulation, the cells were exposed to light for various times with a TouchBright W-96 LED Excitation System (470 nm wavelength, Live Cell Instrument) at an intensity of ∼200 μW/mm2. For the secreted insulin assay, the supernatant was collected from the cell cultures in monSTIM1+/+- and WT-PIOs just before and/or after the respective light stimulation protocol. For the total insulin assay, cells were lysed in 500 μL of acid-ethanol solution using a Vibra-Cell sonicator (Sonics & Materials, Newtown, CT), neutralized with 500 μL of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer (Bioneer), and then incubated at 4°C overnight. The amount of total or secreted insulin was measured using the Ultrasensitive Insulin ELISA Kit (Alpco, Salem, NH) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance values were measured at 450 nm on a Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Fabrication of fibrous PCL membrane

Electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL, Sigma) solution was prepared by dissolving PCL pellets at 20% (w/v) in a mixed solution of dichloromethane (DM, Junsei Chemical) and N, N-dimethylformamide (NDF, Junsei Chemical) at a 1:3 ratio and kept undisturbed overnight at RT. The prepared solution was infused in a 5-mL disposable syringe, then connected to a 30-cm-long Teflon tube (inner diameter: 1.0 mm).

For fabrication through electrospinning, 13 kV voltage was applied at the nozzle tip, and the discharged fibers were collected on the grounded aluminum collector plate. The collector distance was set at 275 mm, and the humidity in the chamber was maintained below 30%.

Transplantation of PIOs into diabetic mice

For easier handling of the PCL membrane, a 1.0 × 1.0-cm square frame was made around the edge of the electrospun sheet by squeezing the melted PCL through a 20 G needle at 3 atm using the direct polymer melting deposition (DPMD) method.66 The DPMD printed PCL frame allows for simple handling and control of the manufactured bag using forceps and bare hands.

Two PCL membranes were joined together for PCL pouches, and the edges were framed with DPMD, leaving the top edge unframed. PCL pouches were then sterilized with a plasma generator for 45 s and then submerged in ethanol for 24 h under ultraviolet light. Approximately 8 × 104 PIOs were mixed with 30 μL of Matrigel supplemented with murine vascular endothelial growth factor 165 (VEGF165, 40 ng, Peprotech) to facilitate the vascularization. The mixture was then transferred into the PCL pouch, followed by heat-sealing with syringe needle. For in vitro light penetration test of the PCL sheet, the same PIOs were encapsulated into the pouch without Matrigel. Encapsulated PIOs were placed into the 24-well glass-bottom plate for photostimulation using TouchBright W-24 LED Excitation System (470 nm wavelength, Live Cell Instrument) at the intensity of ∼200 μW/mm2 for 1 h. Supernatant collected before and after stimulation were assessed with ELISA assay as described earlier.

All animal experiments and animal care were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of KAIST (approval number KA2022-015). Animals used in this study were 8- to 9-week-old male NOD-Prkdcem1BaekIl2rgem1Baek mice (JA BIO, Suwon, Korea). To generate the diabetic condition, mice were intraperitoneally injected with low-dose (40 mg/kg body weight per day) STZ (Sigma) daily for 4 days. At an additional 4 days after the last STZ injection, on the transplantation day, mice were fasted for 4 h, and then anesthetized by injection of 200 mg/kg body weight of Avertin (2,2,2-tribomoethanol, Sigma). Before transplantation, blood glucose level was monitored by portable glucometer (Allmedicus, Anyang, Korea) from tail tip blood, and only mice with >250 mg/dL blood glucose level were considered diabetic. A PCL pouch containing PIOs (PIO implant) was subcutaneously transplanted into the dorsal region of the mouse. For the measurement of human c-peptide in the blood, the mouse was subjected to fasting for 4 h, and then exposed to light in its home cage with an LED lid controlled by a solid-state LED excitation system (473 nm wavelength, Live Cell Instrument, light density of 1 mW/cm2 near the height of mouse skin) for 2 h at 3 or 4 days post-transplantation. For control cohort, the mouse was intraperitoneally injected with D-glucose (2 g/kg body weight, Sigma) and retained for 1 h. Before and after stimulation (glucose or light), the blood sample (∼100 μL) was collected into a Microvette lithium heparin-coated tube (Sarstedt, Newton, NC) by facial vein bleeding or cardiac puncture from the mouse. Human c-peptide level was measured from the plasma separated from the blood by centrifugation at 4°C (2,000 × g, 20 min) using Ultrasensitive C-peptide ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of 450 nm on a Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transplanted PIO implants were retrieved after the last blood sample collection, and fixed in 4% formaldehyde at 4°C overnight, followed by dehydration in PBS supplemented with 30% sucrose (Sigma) at 4°C for 72 h. The implants were embedded in the 7.5% gelatin (supplemented with 10% sucrose in PBS, Sigma) block, frozen at −80°C, and cryosectioned into ∼40 μm slices using a Cryostat (Leica microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Sliced samples were mounted onto the slide glasses to undergo further immunofluorescence processes as described previously.

For the IPGTT, the mouse was subjected to fasting for 6 h at 3 days post-transplantation and then given an intraperitoneal injection of D-glucose at 2 g/kg body weight. Then, blood glucose was measured from tail tip blood at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after the glucose injection. During the IPGTT, the mice were kept in their home cage with the LED lid or in the dark.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was independently performed at least three times. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was carried out to check for normal distributions. Thereafter, all data were evaluated with Student’s t tests using GraphPad Prism 7.00 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The data are presented as means ± SEM unless otherwise noted. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Sora Oh for hPSC maintenance and differentiation. This work was supported by a grant (21A0402L1-12) from the Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.C., W.D.H., and Y.M.H.; Methodology, J.E.C., E.J.S., J.S.L., and D.K.K.; Investigation, J.E.C., E.J.S., J.S.L., and S.D.; Resources, S.D., J.H.S., and J.H.C.; Manuscript writing, J.E.C., E.J.S., J.S.L., S.D., J.H.S., W.D.H., and Y.M.H.; Visualization, J.E.C., E.J.S., W.D.H., and Y.M.H.; Supervision and funding acquisition, Y.M.H.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.03.013.

Contributor Information

Won Do Heo, Email: wondo@kaist.ac.kr.

Yong-Mahn Han, Email: ymhan57@kaist.ac.kr.

Supplemental information

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Deisseroth K. Optogenetics: 10 years of microbial opsins in neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:1213–1225. doi: 10.1038/nn.4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rost B.R., Schneider-Warme F., Schmitz D., Hegemann P. Optogenetic tools for subcellular applications in neuroscience. Neuron. 2017;96:572–603. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tischer D., Weiner O.D. Illuminating cell signalling with optogenetic tools. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:551–558. doi: 10.1038/nrm3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagel G., Szellas T., Huhn W., Kateriya S., Adeishvili N., Berthold P., Ollig D., Hegemann P., Bamberg E. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13940–13945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936192100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stierl M., Stumpf P., Udwari D., Gueta R., Hagedorn R., Losi A., Gärtner W., Petereit L., Efetova M., Schwarzel M., et al. Light modulation of cellular cAMP by a small bacterial photoactivated adenylyl cyclase, bPAC, of the soil bacterium Beggiatoa. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:1181–1188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J., Natarajan M., Nashine V.C., Socolich M., Vo T., Russ W.P., Benkovic S.J., Ranganathan R. Surface sites for engineering allosteric control in proteins. Science. 2008;322:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1159052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy M.J., Hughes R.M., Peteya L.A., Schwartz J.W., Ehlers M.D., Tucker C.L. Rapid blue-light-mediated induction of protein interactions in living cells. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:973–975. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levskaya A., Weiner O.D., Lim W.A., Voigt C.A. Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyung T., Lee S., Kim J.E., Cho T., Park H., Jeong Y.M., Kim D., Shin A., Kim S., Baek J., et al. Optogenetic control of endogenous Ca(2+) channels in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1092–1096. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S., Kyung T., Chung J.H., Kim N., Keum S., Lee J., Park H., Kim H.M., Lee S., Shin H.S., Heo W.D. Non-invasive optical control of endogenous Ca(2+) channels in awake mice. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:210. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Z., Gilbert E.R., Liu D. Regulation of insulin synthesis and secretion and pancreatic Beta-cell dysfunction in diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2013;9:25–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rorsman P., Braun M. Regulation of insulin secretion in human pancreatic islets. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013;75:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rorsman P., Ashcroft F.M. Pancreatic beta-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol. Rev. 2018;98:117–214. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinbothe T.M., Safi F., Axelsson A.S., Mollet I.G., Rosengren A.H. Optogenetic control of insulin secretion in intact pancreatic islets with beta-cell-specific expression of Channelrhodopsin-2. Islets. 2014;6 doi: 10.4161/isl.28095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushibiki T., Okawa S., Hirasawa T., Ishihara M. Optogenetic control of insulin secretion by pancreatic beta-cells in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2015;22:553–559. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontaine A.K., Ramirez D.G., Littich S.F., Piscopio R.A., Kravets V., Schleicher W.E., Mizoguchi N., Caldwell J.H., Weir R.F.F., Benninger R.K.P. Optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic fibers for the modulation of insulin and glycemia. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:3670. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye H., Daoud-El Baba M., Peng R.W., Fussenegger M. A synthetic optogenetic transcription device enhances blood-glucose homeostasis in mice. Science. 2011;332:1565–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.1203535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F., Tzanakakis E.S. Amelioration of diabetes in a murine model upon transplantation of pancreatic beta-cells with optogenetic control of cyclic adenosine monophosphate. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019;8:2248–2255. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li T., Chen X., Qian Y., Shao J., Li X., Liu S., Zhu L., Zhao Y., Ye H., Yang Y. A synthetic BRET-based optogenetic device for pulsatile transgene expression enabling glucose homeostasis in mice. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:615. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20913-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao J., Xue S., Yu G., Yu Y., Yang X., Bai Y., Zhu S., Yang L., Yin J., Wang Y., et al. Smartphone-controlled optogenetically engineered cells enable semiautomatic glucose homeostasis in diabetic mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu G., Zhang M., Gao L., Zhou Y., Qiao L., Yin J., Wang Y., Zhou J., Ye H. Far-red light-activated human islet-like designer cells enable sustained fine-tuned secretion of insulin for glucose control. Mol. Ther. 2022;30:341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansouri M., Xue S., Hussherr M.D., Strittmatter T., Camenisch G., Fussenegger M. Smartphone-flashlight-mediated remote control of rapid insulin secretion restores glucose homeostasis in experimental type-1 diabetes. Small. 2021;17 doi: 10.1002/smll.202101939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millman J.R., Pagliuca F.W. Autologous pluripotent stem cell-derived beta-like cells for diabetes cellular therapy. Diabetes. 2017;66:1111–1120. doi: 10.2337/db16-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair G.G., Tzanakakis E.S., Hebrok M. Emerging routes to the generation of functional beta-cells for diabetes mellitus cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020;16:506–518. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagliuca F.W., Millman J.R., Gürtler M., Segel M., Van Dervort A., Ryu J.H., Peterson Q.P., Greiner D., Melton D.A. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezania A., Bruin J.E., Arora P., Rubin A., Batushansky I., Asadi A., O'Dwyer S., Quiskamp N., Mojibian M., Albrecht T., et al. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:1121–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair G.G., Liu J.S., Russ H.A., Tran S., Saxton M.S., Chen R., Juang C., Li M.L., Nguyen V.Q., Giacometti S., et al. Recapitulating endocrine cell clustering in culture promotes maturation of human stem-cell-derived beta cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:263–274. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0271-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sim E.Z., Shiraki N., Kume S. Recent progress in pancreatic islet cell therapy. Inflamm. Regen. 2021;41:1. doi: 10.1186/s41232-020-00152-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balboa D., Iworima D.G., Kieffer T.J. Human pluripotent stem cells to model islet defects in diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.642152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen S., Du K., Zou C. Current progress in stem cell therapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020;11:275. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01793-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim Y., Kim H., Ko U.H., Oh Y., Lim A., Sohn J.W., Shin J.H., Kim H., Han Y.M. Islet-like organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells efficiently function in the glucose responsiveness in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep35145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grzelak A., Rychlik B., Bartosz G. Light-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species in cell culture media. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;30:1418–1425. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00545-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Icha J., Weber M., Waters J.C., Norden C. Phototoxicity in live fluorescence microscopy, and how to avoid it. BioEssays. 2017;39:1700003. doi: 10.1002/bies.201700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quesada I., Todorova M.G., Alonso-Magdalena P., Beltrá M., Carneiro E.M., Martin F., Nadal A., Soria B. Glucose induces opposite intracellular Ca2+ concentration oscillatory patterns in identified alpha- and beta-cells within intact human islets of Langerhans. Diabetes. 2006;55:2463–2469. doi: 10.2337/db06-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stožer A., Dolenšek J., Rupnik M.S. Glucose-stimulated calcium dynamics in islets of Langerhans in acute mouse pancreas tissue slices. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arrojo E Drigo R., Jacob S., García-Prieto C.F., Zheng X., Fukuda M., Nhu H.T.T., Stelmashenko O., Peçanha F.L.M., Rodriguez-Diaz R., Bushong E., et al. Structural basis for delta cell paracrine regulation in pancreatic islets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3700. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11517-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho J.H., Kang E., Lee B.H., Kim G.H., Choi J.H., Yoo H.W. DEND syndrome with heterozygous KCNJ11 mutation successfully treated with sulfonylurea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017;32:1042–1045. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.6.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hockemeyer D., Soldner F., Beard C., Gao Q., Mitalipova M., DeKelver R.C., Katibah G.E., Amora R., Boydston E.A., Zeitler B., et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qian K., Huang C.T.L., Chen H., Blackbourn L.W., 4th, Chen Y., Cao J., Yao L., Sauvey C., Du Z., Zhang S.C. A simple and efficient system for regulating gene expression in human pluripotent stem cells and derivatives. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1230–1238. doi: 10.1002/stem.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertero A., Pawlowski M., Ortmann D., Snijders K., Yiangou L., Cardoso de Brito M., Brown S., Bernard W.G., Cooper J.D., Giacomelli E., et al. Optimized inducible shRNA and CRISPR/Cas9 platforms for in vitro studies of human development using hPSCs. Development. 2016;143:4405–4418. doi: 10.1242/dev.138081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang F., Tzanakakis E.S. Optogenetic regulation of insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9357. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09937-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahrén B. Islet G protein-coupled receptors as potential targets for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:369–385. doi: 10.1038/nrd2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seino Y., Fukushima M., Yabe D. GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: Similarities and differences. J. Diabetes Investig. 2010;1:8–23. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berndt A., Prigge M., Gradmann D., Hegemann P. Two open states with progressive proton selectivities in the branched channelrhodopsin-2 photocycle. Biophys. J. 2010;98:753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lórenz-Fonfría V.A., Heberle J. Channelrhodopsin unchained: structure and mechanism of a light-gated cation channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1837:626–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prakriya M. The molecular physiology of CRAC channels. Immunol. Rev. 2009;231:88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westacott M.J., Ludin N.W.F., Benninger R.K.P. Spatially organized beta-cell subpopulations control electrical dynamics across islets of langerhans. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston N.R., Mitchell R.K., Haythorne E., Pessoa M.P., Semplici F., Ferrer J., Piemonti L., Marchetti P., Bugliani M., Bosco D., et al. Beta cell hubs dictate pancreatic islet responses to glucose. Cell Metab. 2016;24:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutter G.A., Hodson D.J., Chabosseau P., Haythorne E., Pullen T.J., Leclerc I. Local and regional control of calcium dynamics in the pancreatic islet. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017;19:30–41. doi: 10.1111/dom.12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farnsworth N.L., Hemmati A., Pozzoli M., Benninger R.K.P. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching reveals regulation and distribution of connexin36 gap junction coupling within mouse islets of Langerhans. J. Physiol. 2014;592:4431–4446. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.276733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benninger R.K.P., Head W.S., Zhang M., Satin L.S., Piston D.W. Gap junctions and other mechanisms of cell-cell communication regulate basal insulin secretion in the pancreatic islet. J. Physiol. 2011;589:5453–5466. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.218909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]