Abstract

The objective of the current study was to investigate the grief experiences of people affected by COVID-19. The study adopted a qualitative design of descriptive phenomenology. Fifteen adults who had lost a family member during the COVID-19 pandemic were selected as the sample through the purposive sampling method until theoretical saturation was achieved. Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and the Colaizzi analysis method. Six main themes (i.e., unexpressed grief, psychosomatic reactions, negative emotions, family problems, and social and occupational problems) were extracted. Data analysis showed that complex disenfranchised grief is the pervasive consequence of the COVID-19 experience. According to the findings, participants experienced disenfranchised grief during the loss of their loved ones due to the COVID-19 disease, which was a complex, painful experience accompanied by negative emotions and family, work, and social tensions. This grief is accompanied by more severe and prolonged symptoms, making it difficult for the bereaved to return to normal life. In unexpressed grieving, there are intense feelings of grief, pain, separation, despair, emptiness, low self-esteem, bitterness, or longing for the presence of the deceased. This grief originated from the conditions of quarantine and physical distance on the one hand, which required the control of the outbreak of the COVID-19 disease, and on the other hand, the cultural-religious context of the Iranian people.

Keywords: the covid-19 disease, experiences of grief, bereavement, grief, disenfranchised grief

Introduction

Grief is regarded as a natural reaction to the loss of life during or after traumatic events and disasters. Human also reacts with grief to drastic changes to routines and lifestyles that usually give us contentment and a feeling of balance. People usually show their grief through shock, distrust, denial, anxiety, distress, rage, sadness, sleep disorder, and decreased appetite. Considering all these effects, grief is considered one of the most agonizing common human experiences (Gross, 2015; Howarth, 2011). This process is provoked as a response to death, loss of job, separation or divorce, unanticipated life events, traumas, and other losses (Pop-Jordanova, 2021). In the revised edition of the manual for diseases diagnosis - ICD-11, grief is defined as intense emotional pain, difficulty to accept loss, and an inability to experience positive mood. These reactions can lead to functional impairment and persist for more than 6 months after the loss (World Health Organization, 2018).

Generally, when the grieving reaction is severe, the grieving process lasts more than 2 months, or when a loved one is lost, but the grief has not gone through the normal grieving process, a prolonged grief disorder (PGD) can be recognized (Worden, 2018). In addition to persistent and pervasive longing for, or preoccupation with the deceased one, PGD is also characterized by severe emotional pain like guilt, anger, or sadness and difficulty accepting the death. Sufferers also experience emotional numbness, a sense of lost, difficulty participating in social activities and accepting the loss and experiencing negative mood (World Health Organization, 2018). Lundorff et al. (2017) showed that after a close person died, 9.8% of people would develop PGD. In other words, although an adaptive grieving process is common among many grievers, recent findings revealed that around a 49% in the cases of unnatural losses are at high risk of developing complicated or PGD (Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020).

It is hypothesized that several characteristics in the event can interfere with the grieving process, including unnatural losses or loss characteristics, such as intensive care admission and unexpected death, and loss circumstances, such as infection, quarantine, not having the opportunity to say goodbye, altered funeral services, financial problems, and lack of social support. Additionally, stated that COVID-19 is a multifaceted and complex trauma that causes many psychological, economic, and social stressors. During the COVID-19 epidemic, the family that loses a loved one is in the most difficult psychological state because family members are still forced to stay home. They cannot participate in funerals and post-funeral ceremonies and must stay at home and be in quarantine so as not to lose another loved one due to the COVID-19 disease. COVID-19 poses significant challenges to the grieving or mourning process for the deceased person and caring for and supporting the bereaved ones. As a result of the highly contagious nature of COVID-19, families, children, siblings and other close friends of the deceased are barred from entering the hospitals’ wards. This dehumanized treatment and disenfranchised grief leaves families and friends with no time to say goodbye properly with hearts full of guilt, sadness, distress, and feelings of neglect (Gabay & Tarabeih, 2022).

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, people might be unable to be with a loved one when they die, or unable to mourn someone’s death in-person with friends and family. Additionally, some features of a person may affect grief process. In this regard, Kira et al. (2020) revealed that the will to live and survive could influence the process of grief. They also found that childhood traumas are associated with elevated COVID-19 stress level and at the same time less resilience and social support along with unhelpful coping strategies (Kira et al., 2022). Their results showed that higher difficulty in the grieving process is found in individuals with less resilience and social support, unhelpful coping strategies, and more serious mental health due to COVID-19 (Kira et al., 2021a, 2021b).

It is obvious that the bereaved family is under much pressure in such a situation, and this issue will have adverse consequences in the long run. Every time someone passes away, there are loved ones who are deeply affected by the loss, especially when sanitary restrictions can limit their autonomy and resourcefulness in coping with their grief. If the grievers are aware of these limitations, the risk of experiencing their grief as disenfranchised increases to a degree.

Kenneth Doka was first who formally suggest the notion of disenfranchised grief in 1989. He relates this notion to a situation where a loss is incurred that is not or cannot be openly acknowledged, publicly mourned, or socially supported (Doka, 1989). As Doka (2002) points out society’s grieving norms define what losses and relationships are legitimately grieved. The resultant grief remains unnoticed and underestimated, when a loss does not conform these guidelines. Therefore, a person may perceive that his/her “right to grieve” has been neglected. Consequently, it appears that some bereavements are not socially accepted, like complex grief and those that provoke secondary variables like the disenfranchised grief. The bereaved may also feel guilty for being absent when the death occurs, not expressing their love or saying goodbye (Van Bortel et al., 2016). Therefore, the current pandemic situation may amplify their experience of guilt-shame due to their helplessness (Tay et al., 2017). Disenfranchisement of self may be related to not having the emotional safeness conditions and coping resources in order to fully respond their pain and grieving process. The current increase in pandemic-related anxiety and depression levels contribute to this issue. It may deplete the emotional resources needed to grieve the loss of the person, on its own, or due to the risk of triggering previous mental illness issues. Also, the overload concept in the well-known Dual Process Model may present a clear picture of the current grieving context (Stroebe & Schut, 2016).

Cesur-Soysal and Arı (2022) introduced culture as one of the possible reasons that can explain the difference in the quality of disenfranchise grief. The culture of grieving in Iran is accompanied by mass funerals and many grieving ceremonies with the presence of friends and acquaintances. In some cases, close friends or relatives do not leave the grievers alone at home for up to 7 days. These ceremonies play important roles in the process of natural grieving and facilitate the release of negative emotions associated with grieving. At the funeral and first-week ceremonies, grievers talk about the memories of the loved deceased person and cry. This atmosphere, provided by the presence of others, plays a key role in venting negative emotions and resolving grief or returning to normal life for the bereaved. The grieving ceremonies in the COVID-19 condition, due to serious concerns about the spread of the virus, maintaining hygiene standards, and keeping physical distancing, are either not held or are held very briefly. For these reasons, death resulting from COVID-19 makes the grieving process difficult to resolve and reinforces the ground for unexpressed or complicated grief. Meanwhile, due to the emergence of unpleasant emotions and feelings such as anger, sadness, and the rest concerning the issue of grief and its cultural meaning, the ground is set for expressing wrong thoughts and behaviors and spreading rumors.

To conclude, despite the fact that changes resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have been shown to increase the risk of complicated grief and that the pandemic resembles natural disasters that increase the prevalence of PGD (Mayland et al., 2020; Eisma et al., 2020; Tang & Xiang, 2021), no convincing results have been found regarding how grievers’ experiences and perceptions will influence the grieving process. Therefore, studies with individual in-depth interviews seem necessary to shed more light on the issue (Burrell & Selman, 2022; Şimşek Arslan & Buldukoğlu, 2021). However, the evidence and findings concerning cultural factors and grief reactions of people who lost loved ones during the COVID-19 pandemic has been contradictory. For example, findings from different studies have shown that the context of the COVID-19 pandemic can significantly affect the grief process (Gang et al., 2022; Shahini et al., 2022). On the other hand, there are other studies that point to insignificant relationship between the level of grief or its process in people before or during the pandemic (Eisma & Tamminga, 2020; Şimşek Arslan & Buldukoğlu, 2021). In such circumstances, the research question based on a type III trauma is, what grief experiences did the people who had lost a loved one during the COVID-19 epidemic have? What are the contexts and ideas behind these experiences? What were the meanings constructed during the period of grieving? What is the pervasive nature of their experiences?

Methods

Study Design

This research was a qualitative study with the descriptive phenomenology research type. The method of phenomenology is concerned with the study of lived experience or the living world; in other words, this method focuses on the world as it is lived by a person, not the world or reality as something separate from people, and tries to explore meanings as they are lived in the daily life of individuals. It also tries to explore through reviewing common experiences, taken-for-granted experiences, and revealing new or neglected meanings of these experiences to achieve a new understanding of the living world. The main focus of phenomenology is on the analysis of conscious experiences, and its purpose is to describe life experiences as they have occurred (Creswell et al., 2007). A key requirement for the use of phenomenology, according to Creswell (1998), is the need for a comprehensive understanding of human experiences common to a population. To this end, the lived experiences of the group members should be articulated. As participants’ experiences vary, it becomes harder for the researchers to discover the underlying essences and meanings related to the phenomenon under study. Investigators and researchers in the field of phenomenology should “construct” the objects under study based on their manifestations, structures and components (Ponce, 2014). Phenomenological data analysis involves “horizontalization” of data. It has been shown that although data analytic strategies were diverse (17 unique configurations of data analysis), horizontalization of data emerged as the most effective methodology (Flynn & Korcuska, 2018). During horizontalization, researchers sent the horizons again to the participants as co-researchers after cleaning the data by removing irrelevant statement. This research tries to investigate what circumstances during COVID-19 affect people’s experiences of grief and it aims to pinpoint how this process takes place. Hence, phenomenology method was employed in the present study to explore the lived experiences of people who lost their loved ones due to COVID-19 disease.

In order to comply with the quality standards in the research, after observing the principles of sampling, the desired sample was selected. The entry and exit criteria of the research were carefully considered. Also, the participants were given the necessary explanations about answering the interviews. The researchers answered any ambiguity or problems from the participants and the implementation was done with utmost care. The criterion of reaching the saturation limit has been included in the research in order to meet the desired standard in qualitative research.

Data Sources

The study’s sample was people who had lost one of their first-degree relatives (father, mother, brother, sister, and child) due to the COVID-19 epidemic disease. Participants in this study were selected using purposive sampling with the homogeneous sampling approach and, simultaneously, considering maximum sampling variation. Individuals were selected based on their ability to provide the information needed for the researcher to answer the study’s research questions. All of them had the experience of losing a loved one due to the COVID-19 disease and had a within-group variety in terms of education, age, gender, relationship with the lost loved one, job, and so on. In qualitative research, there is no precise criterion for determining the sample size or the number of participants. However, according to Holloway and Galvin (2016), between 4 and 40 participants are sufficient for this type of research. When the samples in a group are homogeneous, the appropriate number of samples is 6–8 units of data; if the samples are heterogeneous, 12–20 units of data are required. In qualitative research, the open sampling method is used. It implies that the sample size increases until the researcher realizes that theoretical saturation has occurred; that is, he realizes that by increasing the sample size, no further insight is added, and nothing new is discovered. In the present study, interviews continued with 15 participants until data saturation occurred. To achieve data saturation, we use two main factors of theory-based analysis cited by Francis et al. (2010). A minimum of 10 interviews (with appropriate diversity sampling) conducted as part of the initial analysis sample. The study terminated when no distinct themes emerge from three more interviews (Stopping criterion).

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from January 01 2021 to February 05 2021. In this type of interview, the researcher in this study designed a limited number of general and open-ended questions to obtain in-depth information about the interviewees regarding their lived experiences of losing their loved ones due to the COVID-19 disease. The semi-structured interview was designed so that the defined framework was flexible while focusing on the research topic, allowing participants to address aspects of the topic that they considered important. The interview with each participant lasted between 40 and 60 minutes, while sessions were audio-recorded with informed consent from the participants. Pseudonyms and codes were used instead of participants' real names to reassure participants about the confidentiality of data they provided in the interviews and during the research process. The researcher started with this general question “what did you experience as a result of your loved ones' death who died of COVID-19?” (Their perceptions, mentality, feelings, and mood about the death of loved ones were asked about). What contexts or conditions, in general, have been influenced or affected by your experience of a loved one’s death due to COVID-19 disease? The interviews started, and relevant questions were asked based on what the interviewees had said. So deep understanding and explanations regarding the experiences of these people and their conditions and contexts were obtained.

In order to analyze the data collected through semi-structured interviews with participants, the Colaizzi method was used, which includes steps to reach semantic clusters and describes the nature of the bereavement phenomenon. We accurately described the bereavement phenomenon based on the Colaizzi method and its stages in the present study. Namely: 1) Identification of people who have experienced bereavement due to the COVID-19 disease. 2) Data Horizonalization: The researcher identified the participants' quotes that contained “important statements” that described how the participants' experiences were directly related to bereavement. 3) These important statements were categorized into themes. 4) A contextual description of what the participants had experienced was provided. 5) A structural description of the experience of bereavement was provided about its context and substantial conditions. 6) Based on the contextual and structural descriptions, a combined description was provided that reflected the nature of the participants' experiences.

Four criteria of validity, reliability, transferability, and verification were observed in Lincoln’s and Guna’s qualitative research to ensure the accuracy and precision of the research finding in this section.

Results

Participants

Participants in the study include a total of 15 people who witnessed a family member’s death due to COVID-19. The mean and standard deviation of participants’ ages were 35.13 and 13.50, respectively. Most of the participants had a diploma and bachelor’s degrees. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics separately.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Research Participants.

| Code | Gender | Age | Level of education | Marital status | Occupation | The deceased person |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 25 | Bachelor | Single | University student | Mother |

| 2 | Female | 65 | Bachelor | Married | Employee | Child |

| 3 | Female | 45 | Diploma | Married | Housewife | Child |

| 4 | Female | 29 | Bachelor | Married | Employee | Mother |

| 5 | Female | 21 | Diploma | Married | Housewife | Husband |

| 6 | Female | 20 | Bachelor | Single | University students | Father |

| 7 | Female | 55 | Associate | Married | Housewife | Child |

| 8 | Female | 25 | Diploma | Single | Salesperson | Brother |

| 9 | Male | 32 | Master of arts | Married | Employee | Father |

| 10 | Male | 25 | Bachelor | Single | Freelancer | Mother |

| 11 | Male | 33 | Bachelor | Married | Employee | Wife |

| 12 | Male | 40 | Bachelor | Married | Employee | Wife |

| 13 | Male | 45 | Master of arts | Married | Employee | Wife |

| 14 | Male | 55 | Master of arts | Married | Retired teacher | Child |

| 15 | Male | 28 | Master of arts | Married | Employee | Mother |

Table 2 reports the themes of the grieving experiences extracted from the text analysis of interviews with the participants.

Table 2.

Themes Extracted from the Grieving Experiences of the Research Participants.

| Main themes | Sub-themes | Supporting quotation (the relationship to the deceased) |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosomatic reactions | Feeling of suffocation | “I continually felt suffocation. I Felt like someone was squeezing my throat” (daughter) |

| Feeling of pain | “I felt pain in my rib cage, I felt pain in my hands, I felt a headache” (daughter) | |

| The feeling of lethargy and hypotension | “I experienced hypotension many times. I mean, I felt hypotension after my wife died” (son) | |

| Hypochondriasis | “After the death of my wife, I had physical problems. I Had intense itchy skin” (husband) | |

| Sleep problem | “I have not slept well even once during this period. I Usually cry a lot, I cannot sleep, sometimes I see nightmares” (father) | |

| Negative emotions | World worthlessness | “I hate everyone now, and this life is really worthless and meaningless. Nothing in life is worth it. We uselessly try hard; we are always running” (daughter) |

| Disrupted vision of the future | “We were waiting for her to get married. She was old enough to get married, but she died. I Wanted to have grandchildren and see my grandchildren. All these wishes are gone” (mother) | |

| ‘Feeling of sadness | “I was very upset and sad” (mother) | |

| Depression | “Everyone has become depressed after my mother died” (son) | |

| Feeling of loneliness | “We were indeed alone and felt lonely” (son) | |

| Thought rumination | “Most of the time, I just sit in a corner and talk to myself” (son) | |

| Feeling of confusion | “... And we are confused, I do not know what we are doing” (son) | |

| Stress about illness | “We, who have lost our loved one due to this disease and have touched the disease totally, have much stress about the disease” (son) | |

| Feeling of futility | “I always wish I had died instead of my child so I would not have seen this loss. After that, we did not even eat a good meal. We have lost our appetite. We only have a few bites to spend time with because we have to do it” (mother) | |

| Anxiety about future | “It is not clear what the future of the disease is. We are worried about losing someone else due to the disease” (daughter) | |

| Experience of living in limbo (fear and hope) | “It took a few days for my mother to die, we hoped she would get better every day, but we also experienced much fear” (daughter) | |

| Family problems | Intra-family tensions | “Recently, I had a lot of fights with my father at home. We both got bored. My sister is persnickety too, and I don’t want to spend time with her. I fight with her a lot. I am upset with the whole world” (daughter) |

| Limited family relations | “Others used to visit us and ask how we were doing. Many of our relatives and friends were afraid that we would transmit the disease and did not even call” (father) | |

| Losing family enthusiasm | “We used to talk to each other for a long time, we were generally happy, now each of us is in the corner of the house for herself, even we don’t say a word to each other for a long time” (sister) | |

| Unexpressed grief | Problems with burial and funeral | “We strongly believe in holding ceremonies, especially funerals. In this situation, we could not hold any ceremony” (wife) |

| The feeling of guilt and remorse | “I felt the world was ruined on my head. I Intensely felt guilty for his being away from me during that time. I Could not take care of him and felt guilty and remorseful” (mother) | |

| Staying in grief condition | “When I go to his tomb, I sit there for hours. Only over time, maybe after years, will we get used to this bereavement, and this sadness will become a part of our daily life. Life remains with its pains and sorrows. Most of the time, those pains remain fresh forever” (mother) | |

| Continuing crying and restlessness | “We cry a lot. My father cries a lot and is restless” (daughter) | |

| A feeling of vegetative life | “We live just because it is our duty and just to spend time, we have become like an iron man” (mother) | |

| Shock and denial | “I cannot believe it at all. We are still shocked” (mother) | |

| Secondary victims | Lack of attention to personal needs | “Nothing is important for me now; I gave up life” (husband) |

| Helplessness | “I don’t know what to do. I Wish I had been dead” (mother) | |

| Losing supporter | “I was widowed at a young age with a small child that I had to take care of. All expenses and problems were put on my shoulders” (wife) | |

| Occupational and social problems | Financial stress | “I could not go to work. I Had very much stress about how I was going to make ends meet” (husband) |

| Distrust of others | “People are good as long as you do not have a problem; otherwise, their behavior changes” (wife) | |

| Pessimism | “Our neighbors behaved in such a way that they wanted to evict us from the neighborhood as if we had been the COVID-19 disease ourselves” (wife) | |

| Feeling of loneliness | “My mother was the only person I had in my life. Our life fell apart after she left, and I became completely lonely” (daughter) | |

| Doubt about support and assistance of others | “We could not hold a funeral. We expected support from the people, which unfortunately did not exist. Also, close relatives no longer asked after us” (daughter) |

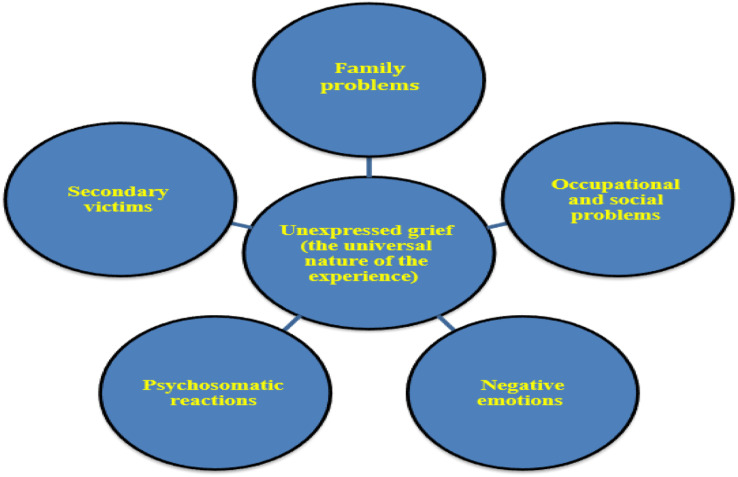

Six main themes were extracted from the analysis of the grieving experiences of the bereaved participants due to the COVID-19 disease.

Main Theme 1: Psychosomatic Reactions: The participants bereaved due to COVID-19 reacted physically to the loss.

Sub-theme 1-1: Feeling of suffocation: For the study participants, the experience of a loved one’s death due to the COVID-19 disease was so difficult and unbearable that some of them experienced suffocation without any presence of disease.

Sub-theme 1-2: Feeling of pain: Study participants reported cases of a feeling of pain since the loss of their family member.

Sub-theme 1-3: Feeling of lethargy and hypotension: The bereaved participants experienced problems such as lethargy and hypotension.

Sub-theme 1-4: Hypochondriasis: Witnessing death due to the COVID-19 disease caused some survivors to experience feelings such as feeling sick and having itchy skin.

Sub-theme 1-5: Sleep problems: Participants had sleep problems after the death of their loved ones. In some cases, not sleeping for several days was a side effect of this experience.

Main Theme 2: Negative emotions: Participants who were bereaved due to the COVID-19 disease experienced a range of negative emotions.

Sub-theme 2-1: World worthlessness: The feeling of worthlessness was one of the sub-themes that emerged from the experiences of the bereaved. In general, this emptiness is more about the world and life.

Sub-theme 2-2: Disrupted vision of the future: Participants believed that the experience of grieving for a loved one caused their wishes to disappear.

Sub-theme 2-3: Feeling of sadness: The bereaved participants experienced great sadness, which was permanent.

Sub-theme 2-4: Depression: Depression is common among bereaved participants.

Sub-theme 2-5: Feeling of loneliness: experiences of the bereaved showed that the stronger the connection between the deceased and the survivor, the greater the feeling of loneliness.

Sub-theme 2-6: Thought rumination: Ruminant in such a way that the person regularly reviews the thoughts related to an incident. The analysis of the participants' experiences showed that they talked to themselves constantly.

Sub-theme 2-7: Feeling of confusion: The analysis of the experiences of the bereaved showed that they experienced a feeling of confusion and lack of control over things.

Sub-theme 2-8: Stress about illness: One of the themes extracted from the participants' experiences was the stress caused by the disease.

Sub-theme 2-9: Feeling of futility: The analysis of the experience of the bereaved showed that the death of their loved ones destroyed all the pleasures they could have in their lives, and they felt empty.

Sub-theme 2-10: Anxiety about the future: The participants were concerned about losing another loved one and how the disease will end in the future.

Sub-theme 2-11: Experience of living in limbo (fear and hope): After the death of one of their family members, the participants experienced being in limbo.

Main theme 3: Family problems: One of the consequences of quarantine and the COVID-19 disease is increased family problems. However, the analysis of the participants' experiences showed that anger and aggression were more common among family members who had lost a loved one due to the disease.

Sub-theme 3-1: Intra-family tensions: The analysis of the experiences of the bereaved showed an increase in tensions among family members, such as irritability, persnickety, and complaints from each other.

Sub-theme 3-2: Limited family relationships: The participants have pointed to the limitation of relationships, even online.

Sub-theme 3-5: Loss of family enthusiasm: The participants' experiences showed that family dynamism, enthusiasm, and vitality among family members were gone.

Main theme 4: Unexpressed grief: The participants reported inability to express or solve their emotions.

Sub-theme 4-1: Burial and funeral problems: The participants' experiences showed that in the condition of COVID-19 disease, no funeral was held for their loved ones, and it was not possible to hold various funeral ceremonies. Such ceremonies provide the opportunity for comfort and solace because of the presence of others.

Sub-theme 4-3: Feelings of guilt and remorse: Since the bereaved were unable to care for their patients during hospitalization, they experienced a sense of guilt and remorse in the absence of their loved ones.

Sub-theme 4-4: Staying in the grieving condition: The analysis of the participants' grieving experiences showed that their grief was not over and continued.

Sub-theme 4-5: Continuing crying and restlessness: One of the signs of unfinished grief in the participants was continuing crying.

Sub-theme 4-6: Feeling of a vegetative life: The pressure of losing a family member caused the remaining members not to enjoy life and to experience a purposeless and futile life.

Sub-theme 4-7: Shock and denial: Coping with this experience was very difficult and unbelievable for the bereaved.

Main theme 5: Secondary victims: Secondary victims refer to family members or caregivers in a situation where a person suffers from an illness, disorder, or problem, and at the same time, other persons, such as family members, are also affected by these problems.

Sub-theme 5-1: Lack of attention to personal needs: For the bereaved, the charm of life was lost, and they ignored their personal needs.

Sub-theme 5-2: Helplessness: The participants were desperate and helpless.

Sub-theme 5-3: Losing one’s supporter: The participants perceived that the death of a loved one had caused them to lose their supporters.

Main theme 6: Occupational and social problems: The participants experienced occupational and social problems during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Sub-theme 6-1: Financial stress: The bereaved participants faced job problems due to the social stigma of the disease and experienced much stress caused by financial problems.

Sub-theme 6-2: Distrust of others: The research participants experienced the death of their loved ones, and the behavior of others toward them caused them to change their views about others and distrust them.

Sub-theme 6-3: Pessimism: The death of the loved ones of the participants of the study caused other people to treat them differently and change their behaviors toward them as if the participants had had COVID-19 themselves.

Sub-theme 6-4: Feeling of loneliness: One of the experiences of the bereaved due to the COVID-19 disease was that they felt very helpless and lonely.

Sub-theme 6-5: Doubt about the support and assistance of others: The experiences of the bereaved due to COVID-19 indicated an increase in their expectations of receiving support from others. However, because they experienced the opposite of what they had expected, feelings of doubt about the support and assistance of others appeared. The summary can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Categorizing the excluded themes of this study.

It has been found that COVID-19 can have inter- and intra-personal psychological effects (Abrams et al., 2021; McMahon et al., 2022). Hence, the consequences of loss due to COVID-19 are categorized into subtopic 2, namely interpersonal and intrapersonal mechanisms. Table 3 summarizes these mechanisms:

Table 3.

Mapping of Outcomes of Covid-19 Loss.

| Mechanisms | Findings |

|---|---|

| Intra-personal | Feeling of suffocation, feeling of pain, the feeling of lethargy and hypotension, hypochondriasis, sleep problem, world worthlessness, disrupted vision of the future, feeling of sadness, depression, feeling of loneliness, thought rumination, feeling of confusion, stress about illness, feeling of futility, anxiety about future, experience of living in limbo (fear and hope), problems with burial and funeral, the feeling of guilt and remorse, staying in grief condition, continuing crying and restlessness, a feeling of vegetative life, shock and denial, lack of attention to personal needs, helplessness, financial stress, pessimism |

| Inter-personal | Intra-family tensions, limited family relations, losing family enthusiasm, losing supporter, distrust of others, feeling of loneliness, doubt about support and assistance of others |

Discussion and Conclusion

Grief is an inevitable experience in every person’s life because the death of a loved one causes grief reactions in the individual. Universally, all people react to the loss of a loved ones with grief (Stroebe & Schut, 1998) ranging from feelings of extreme distress to shock, denial, extreme sadness, and loss of control (Gross, 2015). Different functions help people to regain their control and cope with the grief, including emotional support, funerals, remembrance and prayers for the deceased, and special day rituals (Bolton & Camp, 1987; Mallon, 2008; Gross, 2015; Özel & Özkan, 2020).

In the COVID-19 epidemic, the grieving situation and procedures did not occur properly due to some problems and circumstances. The study found that many participants had negative emotions such as sadness, loneliness, and depression. Similarly, Wallace et al. (2020) found that bereaved person may be susceptible to experience feelings of loneliness, chronic fatigue, and even psychological shock during COVID-19 pandemic. According to Mitima-Verloop et al. (2022), it was not possible for the bereaved families to grieve, be together, and exchange emotions and feelings due to hygiene standards, the possibility of spreading the disease, and people’s fear of infection. Being by the bedside of someone who is seriously ill is an important way to express love. However, this was not possible and is still not possible due to the physical distancing to prevent the spread of the disease. People have experienced many losses during the outbreak of the COVID-19 disease, such as lack of financial security, less social and emotional relationships, endangered autonomy in relocation, and the experience of losing a family member. Some of the participants in this study felt confusion, stress about illness, futility, anxiety about future, fear. These findings are in agreement with psychological symptoms mentioned in Eisma et al. (2020). The results showed that bereaved people who experienced COVID-19 had many psychological symptoms, including unexpressed grief, as funerals were held in particular situations with no family and friends and in abnormal manners. If grieving is not done at the right time, it remains like a lump in the throat of the griever and causes both the intensity of grieving and the increase in its duration. Therefore, the grief may show itself in other situations and in different ways, which can be the basis of many psychological problems.

In addition to these findings, this study revealed that participants experienced unexpressed grief as a symptom of their lived experiences. According to the Iran’s cultural characteristics, where this study was conducted, there are special ceremonies and rituals for grieving and bereavement. Death and grief, and bereavement rituals have been difficult to perform during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of less social support and different burial process, participants experienced unexpressed grief after losing their family members. Similarly, it was found that the rituals and culture helped to regain the sense of control and cope with the grieving process (Wojtkowiak et al., 2021). Also, Zhai and Du (2020) stated that the experience of grief at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak could lead to long-term grief due to its inconsistency with culture and preparation. This study’s findings were in line with that of Şimşek Arslan & Buldukoğlu (2021). They stated that the participants who affected the grieving process amid the COVID-19 pandemic had more physiological grief reactions. This may explain the experience of participants’ unexpressed grief. The disease and living in quarantine, along with the lack of social and family support, are so severe that problems associated with grief arise. In other words, family members have been inevitably forced to distance themselves from each other because of rapid transmission of the COVID-19 (Shear et al., 2011). This is especially true when a person in a family dies from the COVID-19 disease, and family members cannot perform the typical burial and funeral process for their lost loved ones.

In most cases, a person dies without the presence of the family, leaving them with great regret. Feelings of guilt and helplessness remain. Due to these reasons and factors, the bereaved family members may show complicated or unexpressed grief. It remains to be seen to what extent services can adapt, provide the escalating level of care, and prevent a ‘tsunami of grief’. The pandemic remind the society of the importance of the bereavement care as an integral part of health and social care provision.

A number of psychosomatic reactions and symptoms were reported in participants in the current study, including feeling of suffocation, feeling of pain, fatigue, hypotension, hypochondriasis, and sleep disturbances. These symptoms become more vigorous and severe when a person experiences a lack of emotional support, such as losing a family member. Such symptoms also emerged in a previous study by Gica et al. (2020) which examined the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on psychosomatic complaints. The study showed that the psychosomatic complaints increased during the COVID-19 outbreak period, and the changes in perceived threat and biological rhythm, especially intolerance of uncertainty, were effective in this increase.

The participant reported that they feel victimized (secondary victims) because they lost their supporters, could not pay attention to their personal needs and felt helplessness. Similarly, Iheduru-Anderson (2021) noted that nurses reported the feelings of helplessness and loss amid the COVID-19 pandemic. For many, feeling helpless and lost stemmed from having no control over what is happening. For others, it stemmed from being torn and forced to choose between their own well-being, that of their families, their patients, and their jobs. Some felt helpless due to the loss of previous standards of care.

The results of this study also showed that bereaved people during the pandemic felt negative emotions such as worthlessness of the world, gone wishes, sadness, depression, loneliness, thought rumination, confusion, disease stress, and concern for the future. Researchers have shown extensively that high stress, anxiety, and depression cause sleep problems during the COVID-19 epidemic (Cao et al., 2020). Additionally, Freeston et al. (2020) stated that when a person experiences grief, negative feelings and emotions are expressed more severely (Freeston et al., 2020). It is important to note that although people usually respond successfully to grief, some people may not be able to cope successfully with grief, resulting in negative emotions and psychological problems. Relatives who do not have the opportunity to grieve appropriately are more likely to show psychological problems such as sadness and depression (Shear, 2022).

Overall, bereaved people who used to perform certain rituals and ceremonies for the lost member may show more psychological problems if they cannot express their grief. During the outbreak of COVID-19, bereaved people were forced to live in isolation due to their contact with the sick person. These people experience feelings such as fear and anxiety along with bereavement after losing their loved ones (Sun et al., 2020). Also, during the outbreak of the COVID-19 disease, family tensions have increased due to quarantine and recreational problems. This becomes more complicated when a person shows low tolerance due to negative feelings of bereavement. Other factors can also increase grief-related problems such as low self-esteem, socio-economic problems, previous mental health problems, and lack of social support. In general, a high number of deaths occur during a crisis. Several factors prevent people from expressing grief such as low awareness of illness, stigma, discrimination, lack of psychological interventions, financial problems, low emotional and social support, family conflict, and living in particular circumstances due to the crisis. They, in turn, lead to complicated grief and its resulting disorders in the long run. A top grief theory and model, disenfranchised grief, coined by Doka (1989), supported and acknowledged these findings. Hopefully, this research will raise awareness about the grief experiences of the bereaved during the covid-19 pandemic.

Practice Implications

Previous studies have shown that several strategies could decrease the risk of complicated grief, including 1) facilitating “connection” between the patient, and family members via technology to aid communication; 2) practicing individualized care in decision-making, advanced care planning (for instance better access to telehealth and telephone visits and shared resources for enhanced connection), and supporting beliefs and wishes; and 3) discussing opportunities for future remembrance rituals (Parkes & Prigerson, 2013).

Since Covid-19 is a new phenomenon and it only has been addressed in the research literature for 5 years ago, there have not been many studies about grief related to Covid-19. However, this research showed that Covid-19 can be related to grief and involve various emotional (Personal, Interpersonal) and cognitive components of the individuals (Shahini et al., 2022)

Therefore, coping skills should be developed to deal with the psychological problems caused by bereavement during the outbreak of COVID-19, and awareness of psychological issues should be increased in people. Psychological support resources for bereaved families should also be increased. One of the ways through which the pain and sorrow of people who have lost a loved one can be reduced is for the relatives and friends to accompany them. This empathy and companionship (enabled by phone or video call) will significantly reduce the grief of losing a loved one for the griever. In general, the philosophy of holding funerals worldwide is for people to find a chance to have psychological reconstruction.

Study Limitations

One of the limitations of this research is that it was conducted in a specific cultural context, which probably limits the using of the findings in other cultural contexts. Another limitation is related to physical complaints. In other words, physical complaints in participants could be related to being ill with COVID or somatization; therefore, it may influence the results. Thus, it is suggested that other researchers examine the physical health of participants. The suggestion is that the research problem of this study is replicated in other cultural contexts to increase the results' generalizability.

Author Biographies

Mohammad Asgari is an associate professor of assessment and measurement, School of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. His teaching and research interests include psychological testing, research methods in psychology, and statistical methods in psychology.

Mahdi Ghasemzadeh is a M.A in Psychology at the School of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. His clinical and research interests include psychotherapy and psychoeducation.

Asgar Alimohmadi is an assistant professor at the School of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. His clinical and research interests include child psychopathology, developmental disabilities and learning disorders.

Shiva Sakhaei is a Ph.D in Counselling, Department of Educational Science and Counselling, College of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. Her clinical and research interests include counselling and parenting.

Clare Killikelly has been awarded a Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Post-Doc Mobility grant to work at the University of British Columbia. She is a clinical psychologist and clinical researcher specializing in grief and trauma.

Elham Nikfar is a M.A in Psychology at the School of Psychology and Education, Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran. Her clinical and research interests include psychotherapy and psychoeducation.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Elham Nikfar https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7986-4642

References

- Abrams D., Lalot F., Hogg M. A. (2021). Intergroup and intragroup dimensions of COVID-19: A social identity perspective on social fragmentation and unity. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 201–209. 10.1177/1368430220983440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton Christopher, Camp Delpha J. (1987). Funeral Rituals and the Facilitation of Grief Work, 17(4), 343–352. 10.2190/VDHT-MFRC-LY7L-EMN7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell A., Selman L. E. (2022). How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives' mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed method reviews with implications for COVID-19. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 85(2), 345–383. 10.1177/0030222820941296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Fang Z., Hou G., Han M., Xu X., Dong J., Zheng J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287(Special Articles on Mental Health and Covid-19), 112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesur-Soysal G., Arı E. (2022). How we disenfranchise grief for self and other: An empirical study. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, (0), 00302228221075203. 10.1177/00302228221075203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Hanson W. E., Clark Plano V. L., Morales A. (2007). Qualitative research designs: Selection and implementation. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 236–264. 10.1177/0011000006287390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doka K. J. (1989). Disenfranchised grief. Bereavement Care, 18(3), 37–39. 10.1080/02682629908657467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doka K. J. (2002). Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Research PressPub. [Google Scholar]

- Eisma M. C., Boelen P. A., Lenferink L. I. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288(Special Articles on Mental Health and Covid-19), 113031. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma M. C., Tamminga A. (2020). Grief before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Multiple group comparisons. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(6), Article e1-e4. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn S. V., Korcuska J. S. (2018). Credible phenomenological research: A mixed-methods study. Counselor Education and Supervision, 57(1), 34–50. 10.1002/ceas.12092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J. J., Johnston M., Robertson C., Glidewell L., Entwistle V., Eccles M. P., Grimshaw J. M. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology and Health, 25(10), 1229–1245. 10.1080/08870440903194015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston M., Tiplady A., Mawn L., Bottesi G., Thwaites S. (2020). Towards a model of uncertainty distress in the context of Coronavirus (COVID-19). Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13(31), 1–15. 10.1017/S1754470X2000029X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay G., Tarabeih M. (2022). Death from COVID-19, Muslim death rituals and disenfranchised grief–a patient-centered care perspective. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 0(0), 00302228221095717. 10.1177/00302228221095717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gang J., Falzarano F., She W. J., Winoker H., Prigerson H. G. (2022). Are deaths from COVID-19 associated with higher rates of prolonged grief disorder (PGD) than deaths from other causes? Death Studies, 46(6), 1287–1296. 10.1080/07481187.2022.2039326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gica S., Kavakli M., Durduran Y., Ak M. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on psychosomatic complaints and investigation of the mediating role of intolerance to uncertainty, biological rhythm changes and perceived COVID-19 threat in this relationship: A web-based community survey. Personnel, 11(14), 15. 10.5455/pcp.20200514033022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross Richard. (2015). The nature and experience ofgrief. In Understanding Grief: An Introduction (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway Immy, Galvin Kathleen. (2016). Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth R. (2011). Concepts and controversies in grief and loss. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 33(1), 4–10. 10.17744/mehc.33.1.900m56162888u737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iheduru-Anderson K. (2021). Reflections on the lived experience of working with limited personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 crisis. Nursing Inquiry, 28(1), Article e12382. 10.1111/nin.12382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira I. A., Rice K., Ashby J. S., Shuwiekh H., Ibraheem A. B., Aljakoub J. (2022). Which traumas proliferate and intensify covid-19 stressors? The differential role of pre-and concurrent continuous traumatic stressors and cumulative dynamics in two communities: USA and Syria. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 28(1), 1–18. 10.1080/15325024.2022.2050067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kira I. A., Shuwiekh H., Kucharska J., Al-Huwailah A. H., Moustafa A. (2020). “Will to Exist, Live and Survive” (WTELS): Measuring its role as master/metamotivator and in resisting oppression and related adversities. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 26(1), 47–61. 10.1037/pac0000411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kira I. A., Shuwiekh H. A., Alhuwailah A., Ashby J. S., Sous Fahmy Sous M., Baali S. B. A., Azdaou C., Oliemat E., Jamil H. J. (2021. a). The effects of COVID-19 and collective identity trauma (intersectional discrimination) on social status and well-being. Traumatology, 27(1), 29–39. 10.1037/trm0000289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kira I. A., Shuwiekh H. A., Ashby J. S., Elwakeel S. A., Alhuwailah A., Sous M. S. F., Baali S. B. A., Azdaou C., Oliemat E. M., Jamil H. J., Jamil H. J. (2021. b). The impact of COVID-19 traumatic stressors on mental health: Is COVID-19 a new trauma type. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(1), 51–70. 10.1007/s11469-021-00577-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokou-Kpolou C. K., Fernández-Alcántara M., Cénat J. M. (2020). Prolonged grief related to COVID-19 deaths: Do we have to fear a steep rise in traumatic and disenfranchised griefs? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S94–S95. 10.1037/tra0000798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundorff M., Holmgren H., Zachariae R., Farver-Vestergaard I., O’Connor M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212(6), 138–149. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallon B. (2008). Dying, death and grief: Working with adult bereavement. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mayland Catriona R., Harding Andrew J.E., Preston Nancy, Payne Sheila. (2020). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(2), 33–39. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon G., Douglas A., Casey K., Ahern E. (2022). Disruption to well-being activities and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediational role of social connectedness and rumination. Journal of Affective Disorders, 309(15), 274–281. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitima-Verloop H. B., Mooren T., Kritikou M. E., Boelen P. A. (2022). Restricted mourning: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on funeral services, grief rituals, and prolonged grief symptoms. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13(0), 878818. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.878818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özel Yasemin, Özkan Birgül. (2020). Psychosocial Approach to Loss and Mourning. Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 12(3), 352–367. 10.18863/pgy.652126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes C. M., Prigerson H. G. (2013). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce O. A. (2014). Investigación cualitativa en educación: Teorías, prácticas, debates. Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas. [Google Scholar]

- Pop-Jordanova N. (2021). Grief: Aetiology, symptoms and management. Prilozi, 42(2), 9–18. 10.2478/prilozi-2021-0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahini N., Abbassani S., Ghasemzadeh M., Nikfar E., Heydari-Yazdi A. S., Charkazi A., Derakhshanpour F. (2022). Grief experience after deaths: Comparison of covid-19 and non-covid-19 causes. Journal of Patient Experience, 9(1), 23743735221089697. 10.1177/23743735221089697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear M. K. (2022). Grief and mourning gone awry: Pathway and course of complicated grief. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 119–128. 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/mshear [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear M. K., Simon N., Wall M., Zisook S., Neimeyer R., Duan N., Reynolds C., Lebowitz B., Sung S., Ghesquiere A., Gorscak B., Clayton P., Ito M., Nakajima S., Konishi T., Melhem N., Meert K., Schiff M., O'Connor M. F., Keshaviah A. (2011). Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 103–117. 10.1002/da.20780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek Arslan B., Buldukoğlu K. (2021). Grief rituals and grief reactions of bereaved individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, (0), 00302228211037591. 10.1177/00302228211037591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H. (1998). Culture and grief. Bereavement Care, 17(1), 7–11. 10.1080/02682629808657425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H. (2016). Overload: A missing link in the dual process model? OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 74(1), 96–109. 10.1177/0030222816666540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Bao Y., Lu L. (2020). Addressing mental health care for the bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74(7), 406–407. 10.1111/pcn.13008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Xiang Z. (2021). Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19? Prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12992-021-00669-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay A., Rees S., Steel Z., Liddell B., Nickerson A., Tam N., Silove D. (2017). The role of grief symptoms and a sense of injustice in the pathways to post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-conflict Timor-Leste. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 26(4), 403–413. 10.1017/S2045796016000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortel T., Basnayake A., Wurie F., Jambai M., Koroma A. S., Muana A. T., Hann K., Eaton J., Martin S., Nellums L. B. (2016). Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(3), 210–214. 10.2471/BLT.15.158543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace C. L., Wladkowski S. P., Gibson A., White P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), Article e70–e76. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtkowiak J., Lind J., Smid G. E. (2021). Ritual in therapy for prolonged grief: A scoping review of ritual elements in evidence-informed grief interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(0), 623835. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.623835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden J. W. (2018). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. springer publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y., Du X. (2020). Loss and grief amidst COVID-19: A path to adaptation and resilience. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87(5), 80–81. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]