Abstract

Distinct fungal communities or “mycobiomes” have been found in individual tumor types and are known to contribute to carcinogenesis. Two new studies present a comprehensive picture of the tumor-associated mycobiomes from a variety of human cancers. These studies reveal that fungi, although in low abundance, are ubiquitous across all major human cancers and that specific mycobiome types can be predictive of survival.

The human mycobiome is less populous than the bacteriome but can still greatly affect human health (Aykut et al., 2019; Elaskandrany et al., 2021; Iliev and Leonardi, 2017). Like bacteriome profiles, the differential fungal composition within individuals in a population is derived from a complex interplay of several factors including geographic location, sex, age, race, diet, and lifestyle (Elaskandrany et al., 2021). There is compelling evidence that polymorphic variability in the microbiomes between individuals in a population can have a profound impact on cancer phenotypes, with either protective or deleterious effects on cancer development, malignant progression, and response to therapy (Helmink et al., 2019; Sepich-Poore et al., 2021). Recently, fungi have been found to contribute to carcinogenesis in esophageal and pancreatic cancer (Alam et al., 2022; Aykut et al., 2019).

In this issue of Cell, Narunsky-Haziza et al. (2022) characterize the cancer mycobiome within 17,401 patient-derived tissue, blood, and plasma samples across 35 cancer types from four independent cohorts using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing and whole-genome sequencing methods. Narunsky-Haziza et al. first used whole-genome sequencing and transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets from two cohorts: the Weizmann cohort (WIS) containing 1,183 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded or frozen samples of tumor, normal adjacent tissue, and non-cancerous tissue from eight tissue types; and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort, which consists of 15,512 samples. Using these data, the authors sought to define the fungal signature associated with various cancers (Figure 1A). The authors further developed various staining techniques to visualize fungi in tumor types. The data showed the ubiquitous presence of fungi across all major human cancers, with cancer-specific compositions (Figure 1A). Histological staining of tissue revealed the intratumoral presence of fungi and their frequent spatial association with cancer cells and macrophages. Mycobiome richness varied significantly across cancer types in both the WIS and TCGA cohorts, and the fungal load was significantly higher in tumors as compared to negative controls. The genome datasets discovered 31 specific fungi with ≥1% collective genome coverage. Narunsky-Haziza et al. identified various fungi including Saccharomyces cerevisiae (99.7% coverage), Malassezia restricta (98.6% coverage), Candida albicans (84.1% coverage), Malassezia globosa (40.5% coverage), and Blastomyces gilchristii (35.0% coverage). The study revealed the presence of low-abundance, cancer-type-specific mycobiomes; however, beta-diversity and permutational multivariate analysis of fungi in the WIS and TCGA cohorts failed to show significant differences between tumor and normal adjacent tissues, suggesting a limitation of the sample size and data analysis. However, when Narunsky-Haziza et al. analyzed the plasma mycobiome from two independent cohorts (Hopkins [n = 537] and University of California San Diego [UCSD] [n = 169]) of 11 cancer types, they found significant differences between cancer and controls. The authors identified a signature of circulating fungal DNA from 20 distinct fungi that potentially can be used to distinguish pan-cancer versus healthy individuals, suggesting the utility of using the mycobiome in cancer diagnostics, even in patients with early-stage disease. Another significant finding of this study is the interaction of the mycobiome and bacteriome in the tumor microenvironment. The authors compared intratumoral fungal and bacterial communities and discovered co-existing, noncompetitive bacterial and fungal ecologies; however, each had distinct immune responses. The average relative abundances of bacteria and fungi in TCGA primary tumors were 96% bacteria and 4% fungi, further confirming low abundance of fungi as compared to bacteria. When machine learning and differential abundance testing of mycobiomes was applied, the authors were able to distinguish cancer versus non-cancerous tissues as well as between and within cancer types, supporting the significance of the findings.

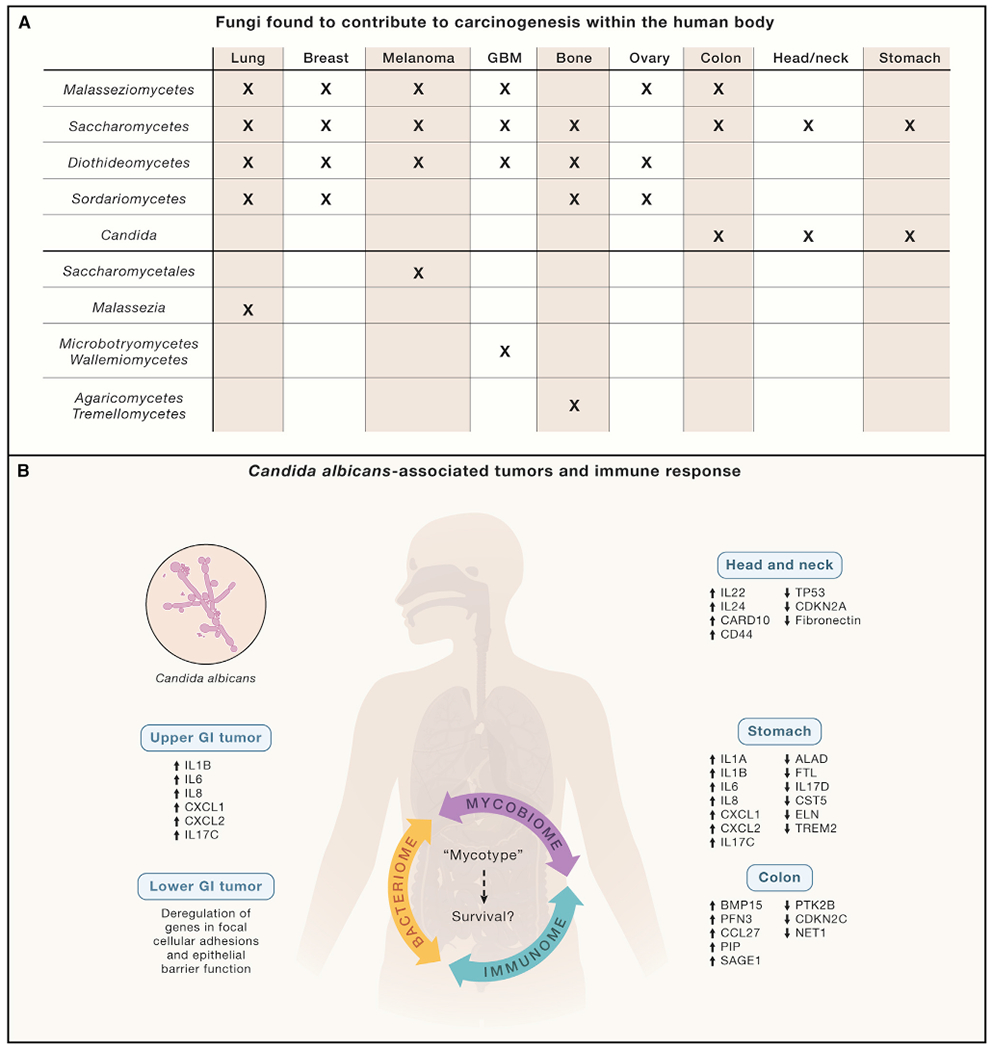

Figure 1. Distinct mycobiome signature and immune response in different cancers.

(A) Fungal diversity in WIS and TCGA cohorts. Fungi belonging to classes Malasseziomycetes, Saccharomycetes, Diothideomycetes, Sordariomycetes, and the genus Candida were found to be significantly enriched in various types of cancers while some specific fungi were only found in a cancer at a specific site.

(B) Potential effects of fungi in tumors on mycobiome-bacteriome-immunome interactions. Gene regulation in various cancers in response to high abundance of Candida. The upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin 6 (IL-6), is well known to promote cancer progression. At the same time, chronic inflammation also promotes Candida growth, suggesting that Candida infection in various cancers may be key to cancer therapy. Fungal-driven, pan-cancer “mycotypes” with distinct immune responses can predict survival. Narunsky-Haziza et al. proposed three distinct fungal based fungi-bacteria-immune clusters called “mycotypes”: F1 (Malassezia-Ramularia-Trichosporon), F2 (Aspergillus-Candida), and F3 (multi-genera including Yarrowia). The log-ratio comparisons of these myotypes and clinical data may have the potential to predict cancer survival.

Similarly, an independent study in this issue by Dohlman et al. (2022) reported a pan-cancer analysis of multiple anatomically distinct body sites and identified diverse tumor-specific mycobiomes. Dohlman et al. analyzed multiple cancer types from the TCGA cohort and extracted community profiles of tumor-associated fungi with genus- and species-level resolution. Like Narunsky-Haziza et al., Dohlman and colleagues found that fungal sequences were represented in a much smaller proportion as compared to bacterial sequences. Fungal DNA was particularly abundant in tissues from head and neck, colon and rectum, and stomach, but less abundant in the esophagus and negligible in brain tissue. The study further revealed that gastrointestinal cancers had a different relative abundance of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae, suggesting that cancers of the gastrointestinal tract can be segregated into Candida and Saccharomyces-associated tumors. Candida-dominant (Ca-type) and Saccharomyces-dominant (Sa-type) tumors showed several interesting differences in gene expression (Figure 1B). Ca-type tumors were associated with increased expression of IL-1 pro-inflammatory immune pathways and increased neutrophils and suggested a Type 17 signature. Blastomyces were highly prevalent in lung tumor tissues, whereas in stomach cancers a higher abundance of Candida was observed with higher expression of pro-inflammatory immune pathways, further suggesting the role of the mycobiome in tumorigenesis and inflammation. IL-1 is a major inflammatory cytokine that plays a key role in carcinogenesis and tumor progression. In colon cancers, Candida was not only predictive of late-stage disease and metastasis but also associated with an attenuation of cellular adhesion mechanisms. Candida is suggested to be functionally associated with multiple cancers (Figure 1B). Analysis of stomach cancers showed that Candida interacted with bacterial species and positively correlated with Lactobacillus spp., whereas it was anti-correlated with H. pylori. L. spp. have been shown to affect the attachment of both H. pylori and Candida spp. to epithelial cells, which may play a role in their colonization. Inflammation promotes Candida colonization, which maintains pro-inflammatory environment by itself increasing inflammation; thus, a vicious cycle is sustained. Prevention and management of Candida infections in cancers may therefore be useful in blocking this damaging inflammatory state.

Overall, the pan-cancer analysis presented by Dohlman et al. showed that across all gastrointestinal (GI) sites, Candida species were transcriptionally active and was specifically enriched in tumor samples compared to matched normal tissue, and the presence of tumor-associated Candida DNA is associated with decreased overall survival. However, no clear mechanism is proposed. Additional mechanistic studies may help to clarify whether tumor-associated Candida is a key factor in tumorigenesis.

The fungal species identified in these two studies may reprogram innate immune cells, thus throwing the host immune response into disarray and resulting in a persistent immunotolerant state that favors disease progression. Earlier we reported that free-living fungal species of Malassezia secrete hydrolases to release host lipids and activate the C3 complement-mannan-binding lectin (MBL) pathway, promoting an immunosuppressive tumor milieu in pancreatic cancer (Aykut et al., 2019). Similarly, Alam and colleagues (2022) demonstrated that pancreatic cancer was infiltrated by Alternaria and Malassezia, two well-known fungal genera present in the gut. Specifically, the intratumoral mycobiome has been shown to activate dectin-1-mediated Src-Syk-CARD9 signaling in the pancreas, leading to a secretion of IL-33 (Alam et al., 2022); this resulted in tumor growth and therefore suggests a possible mechanism of the mycobiome’s role in cancer progression. Although fungal-driven pancreatic oncogenesis occurs via complement cascade activation and IL-33 secretion, little is known about fungal functional repertoires in other cancers. These two studies by Narunsky-Haziza et al. and Dohlman et al. will be a big step forward to initiate hypothesis-driven mechanistic studies on the role of the mycobiome in various cancers. The finding of a distinct fungal signature in many tumor types may also have implications in cancer therapy (Helmink et al., 2019; Sepich-Poore et al., 2021); for example, the dysbiosis in the microbiome (mycobiome or bacteriome) can be treated by antimicrobial therapy, targeted pre- or probiotic therapy, modulation of diet, or a combination with chemo- or immunotherapy. These studies also have some limitations specifically with regard to sample pools, as most of the samples were not collected for microbiome studies. However, both groups developed robust algorithms to eliminate possible contaminants and tried to showthat diverse sample types may not have much impact on analysis. This is evident by the fact that in the two datasets used by Narunsky-Haziza et al., 87.2% of WIS species and 93.4% of fungal genera had matched TCGA cancer types with similar conclusions irrespective of cohort.

Many bacteria are known to affect cancer therapies (Pushalkar et al., 2018), and thanks to these new findings, fungi can now be included in updated cancer microbiome “hallmarks” (Hanahan, 2022). Symbiotic and antagonistic relationships between fungi and bacteria further motivate researchers to study their interactions in tumors, and combining their information provides synergistic role in various cancers. The significance of these two studies is that the prognostic and diagnostic capacities of the tissue and plasma mycobiomes can be developed for use in clinical settings, and synergistic predictive performance with bacteriomes will have significant implication in cancer diagnostic research (Helmink et al., 2019; Sepich-Poore et al., 2021).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH, United States grants RO1 CA206105 (D.S.); DOD W81XWH-19-1-0605 (D.S.); DOD, United States W81XWH-19-1-0603 (X.L.); and R41 CA250892 (X.L. and D.S.).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

X.L. and D.S. are co-founders of Periomics-Care LLC.

REFERENCES

- Alam A, Levanduski E, Denz P, Villavicencio HS, Bhatta M, Alhorebi L, Zhang Y, Gomez EC, Morreale B, Senchanthisai S, et al. (2022). Fungal mycobiome drives IL-33 secretion and type 2 immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell 40, 153–167.e11. 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aykut B, Pushalkar S, Chen R, Li Q, Abengozar R, Kim JI, Shadaloey SA, Wu D, Preiss P, Verma N, et al. (2019). The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 574, 264–267. 10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohlman AB, Klug J, Mesko M, Gao IH, Lipkin SM, Shen X, and Iliev ID (2022). A Pan-Cancer Mycobiome Analysis Reveals Fungal Involvement in Gastrointestinal and Lung Tumors. Cell 185, 3807–3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elaskandrany M, Patel R, Patel M, Miller G, Saxena D, and Saxena A (2021). Fungi, host immune response, and tumorigenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 321, G213–G222. 10.1152/ajpgi.00025.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D (2022). Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 12, 31–46. 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-21-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmink BA, Khan MAW, Hermann A, Gopalakrishnan V, and Wargo JA (2019). The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat Med 25, 377–388. 10.1038/s41591-019-0377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliev ID, and Leonardi I (2017). Fungal dysbiosis: immunity and interactions at mucosal barriers. Nat. Rev. Immunol 17, 635–646. 10.1038/nri.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narunsky-Haziza L, Sepich-Poore GD, Livyatan I, Asraf O, Martino C, Nejman D, Gavert N, Stajich JE, Amit G, González A, et al. (2022). Pan-cancer Analyses Reveal Cancer Type-specific Fungal Ecologies and Bacteriome Interactions. Cell 185, 3789–3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushalkar S, Hundeyin M, Daley D, Zambirinis CP, Kurz E, Mishra A, Mohan N, Aykut B, Usyk M, Torres LE, et al. (2018). The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 8, 403–416. 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-17-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepich-Poore GD, Zitvogel L, Straussman R, Hasty J, Wargo JA, and Knight R (2021). The microbiome and human cancer. Science 371, eabc4552. 10.1126/science.abc4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]