Abstract

Developing markets are using sustainable development potential to reach zero-carbon goals. Due to the limitation of natural resources, companies need to use environmentally friendly manufacturing to develop a circular economy (CE). Green finance (GF) and the CE are linked in a systematic and complex approach; therefore, it was essential to employ the coupling coordination-level framework to explain their relationship and feedback. Any study linking green financing and CE together has been found. The objective of this research is to explore this twofold domain and determine its main characteristics. To address this objective, a comprehensive review of the literature was conducted, supplemented by a bibliometric analysis. The results confirm that GF has the potential to help society, sustainability, and the prevention to climate shifts, investing in the CE. There are many hurdles to overcome, including inadequate knowledge about CE and GF, ambiguous definitions, a lack of coherence between legal frameworks on CE and green financing, unclear laws, and a lack of financially viable motivation for investors and financial institutions that are ready to promote in sustainability. This study explores CE and GF domains. Managers may readily increase their understanding of methods, strategies, and technical solutions beneficial to assist their operations toward a green economy depending on various CE and GF elements. Finally, based on a categorization of GF types, the assessment identifies future investment potential consequences of green financing in the CE.

Keywords: Circular economy, Sustainable finance, Nexuses, Green finance, Circular supply chains, Responsible production and consumption

Introduction

Our world is on track to break global climate change records in the twenty-first century (Jiang et al., 2023; Siegert et al., 2020). Over the past decade, there have been wide demands to ensure natural resources are used equitably to slow their rapid decline and prevent disastrous effects on future generations (Kapustkina, 2021; Kumar et al., 2023). According to research on monitoring the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, the number 12 on sustainable consumption and production is critical to accomplishing several other linked goals (Campbell et al., 2019). The implications of a circular economy (CE) are wide-ranging and essential for reversing human-caused climate change (Dwivedi et al., 2023). CE, in line with Goal 12, is strictly related to the 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle) (Manoharan et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022), recently extended to 9 (adding Refuse, Rethink, Repair, Refurbish, Remanufacture and Repurpose) (European Commission, 2020). The idea of a CE acquired significant momentum among various countries, groups, lawmakers, academic institutions, research scholars, and businesses worldwide in the twenty-first century (Di Vaio et al., 2023a, 2023b, 2023c; Merli et al., 2018). According to some studies, CE initiatives can help to reduce waste, maximize resource reuse, and ecosystems protection, resulting in a win–win scenario for businesses, the market, and the environment (Austin & Rahman, 2022; D’Adamo, 2022; Sassanelli et al., 2019). This lifecycle idea has developed over time, from specific businesses to the entire CE. The development of a CE is a necessary decision for achieving economic advancement and resource efficiency (Rodrigo-González et al., 2021). The current linear economic systems cannot be maintained without significant adjustments to existing patterns of production and consumption (Ikram, Sroufe, et al., 2021). The ecosystem, society, and business may all benefit from CE initiatives that use the 9 Rs as their primary approach (Acerbi et al., 2022; D’Adamo, 2022). The world needs an immediate implementation of a CE system that safeguards the planet and advances humanity (Garcés-Ayerbe et al., 2019). There will be large costs involved with the shift to a CE. These include public spending on green infrastructure, new product subsidies, research & development, and capital expenditures (Austin & Rahman, 2022). The link between finance and the CE’s growth is quite close. The industrial transformation of the CE requires market-oriented green financial assistance. The initial capital expenses and expected payback time are more responsive to additional financing emerging from green product innovation and green initiatives (Sepetis, 2022; Tagar et al., 2022).

The development of the CE is still in its early stages, and access to finance for the growth of the CE is very limited. This is primarily due to insufficient macroeconomic policy guidelines and economic venture, lacking economic sector building and financial institution development, a low percentage of capital market financing, and inadequate funding tool invention, all of which have hampered the advancement of the CE (Xiaofei, 2022; Yuan et al., 2020). Kumar et al. (2022); Wang and Zhi, (2016) define the green finance (GF) economy as “a financial gateway of resources for the protection of the environment and CE,” suggesting that the market economy would allocate resources to publicly appropriate economic development drivers through social investment. The debate, however, revolves around the necessity for a steady between environmental advantages and economic progress, with the balance rolling from one to the other when conditions (such as the World Financial Crisis) demand. Furthermore, the challenging development of a financial support and assurance framework for the growth of the CE has been limited by the poor economic climate and a lack of risk-compensating measures (Xiaofei, 2022). The CE can be classified into various levels, such as company manufacturing, industrial parks, towns, and regions, based on the area and range it includes, and each sector has its own unique financial requirements (Ikram, 2022; Sarmento et al., 2022). Recent articles have emphasized the potential and prospects of CE, GF, as well as the need to overcome various current obstacles and increase transparency by enforcing reporting, standardization, and refining definitions and metrics for circular activity (Dewick et al., 2020; Sarmento et al., 2022). This shows that the development of a CE may depend on conventional financing mechanisms, such as financial commitment and lending, but should increase money through numerous financial institutions at all stages and necessitate a portfolio expansion strategy.

In recent years, there has been a notable surge of interest among scholars from diverse research disciplines and countries in the research domains of GF and CE separately. The period spanning 2011 to 2022 witnessed a multi-fold increase in the number of research publications dedicated to GF and CE, underscoring their growing significance as research priorities (Akomea-Frimpong et al., 2022; Alcalde-Calonge et al., 2022). As such, it is critical to conduct a comprehensive review, analysis, and synthesis of the existing research at one place in these areas to gain a holistic understanding of the overall research context, findings, and prospects for defining future research trajectories maximizing the impact of combined GF and CE research across various domains.

Indeed, to encourage the development of a CE, it is essential to make full use of finance, which is a significant market-oriented resource. Finance not only manages funds but also improves the industrial supply chain, making it the backbone of the modern economy (Debrah et al., 2022). Finance represents an essential foundation for expanding the CE domain. Studies into the mechanisms behind the progress of GF and CE are important to the progress of the environmental sustainability, economy, and society. GF in CE offers a great opportunity to overcome the CE financing gaps. It may also help overcome the cost barrier to sustainability and CE. However, access to finance for the growth of the CE is limited, and there is a lack of risk-compensating measures. The recent surge of interest among scholars from diverse research disciplines and countries in the research domains of GF and CE underscores their growing significance as research priorities.

The primary motivation for carrying out this research is that the application of GF in CE represents a potential chance for filling the investment gap in the CE and overcoming green innovation cost obstacles. However, to enhance and support GF in CE among researchers, policymakers, and practitioners, a comprehensive review of their combined current state and future requirements is required. Previous research concentrated solely on GF or the CE. No research has provided a complete summary of GF in CE. As a result, the purpose of this research is to perform explore the twofold research context of GF in CE, answering the following research question: “What is the present status of GF in CE implementation, and what are the upcoming requirements and opportunities for its growth?”. The following research objectives are created to accomplish this goal:

to provide a comprehensive review and synthesis of existing literature on GF and CE, including the research context, findings, and prospects for future research,

to identify and analyze the key drivers, barriers, and opportunities for the development of a GF and CE,

to examine the potential of GF and CE as a means to achieve sustainable development, particularly in relation to sustainable consumption and production patterns.

to propose a research agenda for future studies on GF and CE, focusing on interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral approaches, and addressing emerging issues such as digitalization, innovation, and resilience.

to come up with suggestions for how to move the research forward and make the study more useful in practice.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reports the research context. Section 3 explains the research method adopted. Section 4 shows the results obtained, and Sect. 5 discusses them. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes the paper.

Background and research context

This section defines all of the research's key concepts related to CE, circular supply chain, GF, and environmental finance in order to prepare for their collective study.

Circular economy

The recent times have heightened the sense of urgency and ambition surrounding the concept of the CE, which can be challenging to define precisely. However, this ambiguity has actually increased interest and engagement with the CE to date. Drawing on the DOI theory, this space for creativity and willingness to disrupt the status quo can foster greater dedication to extending and challenging current practices. In sum, CE programs highlight a range of objectives rooted in ongoing activities (Di Vaio et al., 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). A widely accepted definition of the CE has been put forth by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF, 2013): “CE is one that is regenerative and restorative by structure and strives to keep products, elements, and substances at their largest value and price at all periods, differentiating between biological and technological phases.” According to Milios (2021) and Broten et al. (2004), business practices for the CE may be separated into two categories: those which boost reuse and extend life of product by maintenance, modifications, reproduction, and refurbishments, and those that recycle the resources from used products to build resources that are as good as new. The strategy should be focused on individuals of various ages and levels of education. Ownership provides a path to stewardship, and customers become users and producers. Remanufacturing and repairing worn-out items, buildings, and infrastructure in local workshops produce skilled employment. Former workers are a useful source of information. However, CE’s importance has just recently become more widely recognized. Old industrial techniques have gradually been replaced by closed-loop systems that are solely dedicated to integrating economic, ecological, and societal implications (Rosa et al., 2019). According to the D’Adamo (2019), CE model is required to construct a closed-loop cycle as a replacement of linear system. As a result, the meaning idea for both the environment and the economy must be demonstrated. Therefore, CE has also become an important field of academic research during the past ten years, as seen by the steep increase in the number of publications and journals covering this topic. Businesses are also starting to recognize the advantages of CE and its potential advantages for both themselves and their stakeholders (Taddei et al., 2022).

Circular supply chain

Undoubtedly, the theories of legitimacy and institutionalism have had a significant impact on the development of SDGs benchmarking (Colasante & D’Adamo, 2021). Today, cross-functional integration is necessary for accurately describing innovative processes and attaining harmony between economic and engineering endeavors (Koksharov et al., 2019). A circular supply chain has been defined from two different perspectives. According to the material perspective, a circular supply chain is one in which materials are continuously reused and recycled once they have reached the end of their useful lives and there are very few materials wastes overall (Taddei et al., 2022; Yousafzai et al., 2020). Others take a broader approach, considering circular supply chains, also known as C2C supply chains, as essential components of production systems. Such systems must close the material loop, generate no solid, liquid, or gaseous waste, minimize the use of hazardous chemicals, and rely exclusively on renewable energy sources (Genovese et al., 2017; Saccani et al., 2023). A definition of circular supply-chain management (CSCM) has only recently been found in the literature, despite the fact that the phrase “circular supply chain” was used in several researches to combine CE with SCM (Zhang et al., 2023). CSCM involves synchronizing forward and reverse supply chains through intentional business ecosystem interconnections to generate wealth from goods and services, by-products, and useful waste flows while promoting an organization's economic, cultural, and environmental sustainability (Farooque et al., 2022; Mishra et al., 2018; Nasir et al., 2017). Materials recovered by companies other than the original producers who are allowed to reuse them are included in open-loop SCs. For the purpose of recovering additional value, items are returned to the original producer through closed-loop supply chains (CLSCs). The latter, which builds on reverse logistics, includes recycling, remanufacturing, and utilization (Hussain & Malik, 2020). Gains related to both environmental and economic performance are produced via green supply chains, which include suppliers and customers to support environmental cooperation (Masi et al., 2017). Green supply chain management is defined as being environmentally friendly in terms of product design, raw selection of materials and purchasing, manufacturing, transportation, and post-sale activities (Hussain & Malik, 2020; Kazancoglu et al., 2018).

Green finance

In 2010, a group of 194 countries established the Green Climate Fund (GCF) to provide financial support for global greenhouse gas emission mitigation efforts (Amoah et al., 2022; Cui & Huang, 2017). The main objective of the fund was to promote and facilitate GF initiatives and raise awareness of the concept worldwide. Since its inception, the principles of the GCF and GF in general have been discussed at various forums, including the G-8 and G-20 summits and the United Nations General Assembly (Akomea-Frimpong et al., 2022). Moreover, sustainable private finance, also known as GF, has been recognized as an essential part of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 16 and 17 (Li et al., 2023).

However, what defines “green finance” is an issue of contention between many researchers and reputable institutions globally (Li et al., 2023; Patterson et al., 2021). While some authors contend that GF is the same as sustainable finance (or green bond or green investment) based on utilization and context, others disagree (Hafner et al., 2020; Migliorelli & Philippe Dessertine, 2019). The best approach to enhance the volume of financial flows (banking, microcredit, insurance, and investment) from the government, commercial, and non-profit sectors in order to support SDGs is through the use of GF. As a result, GF is important to accomplishing the goal of SDGs that take into account green economy (Ahmad et al., 2022; Campiglio, 2016). Therefore, inclusive green growth may be achieved through accessible GF, as inclusive GF aids in reducing the negative effects of climate change and fostering adaptability. Financial institutions are required to promote green goods in savings, credit, insurance, transfers of money, and modern electronic delivery channels in order to offer those funds essential help to people navigating an unpredictable climate. Consequently, overall investment strategy should change to be more environmentally friendly, as it will help to achieve the UN SDGs, especially SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), and SDG 13 (climate action), all of which are designed to promote green growth. Bank lending is especially notable among such for two primary reasons (Ahmad et al., 2022). First, the most frequent source of external financing for businesses is bank loans (Chen et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2022). For example, the total amount of bank lending to British firms in 2013 was roughly three times the total amount of corporate bond issuance and more than 10 times the total value of public equity (Hussein & Hamdan, 2020). By providing funding to businesses that are prepared to take positive environmental action, or “green economy,” GF seeks to increase the financial sector's contribution to environmental protection (Kumar et al., 2022). Recent years have seen as rise in the use of green financing as a strategy for addressing environmental problems (Desalegn & Tangl, 2022). The effectiveness of green financing in addressing current environmental problems, however, is still challenging since there is still uncertainty about how to fulfill the green investment gap, which has been found to be rather large.

Research methodology

This study is based on a systematic literature review (SLR). SLR is an useful method for evaluating development in a research subject and developing a new research (Corona et al., 2019; Desalegn & Tangl, 2022; Tranfield et al., 2003), and it is a scientific, transparent, and replicable process (Di Vaio et al., 2022a, 2022b). The SLR analysis supports the development of the proposed theoretical structure on CE and GF. This analysis aims to contribute to the advancement of the literature in this area (Paul & Criado, 2020). SLR has the following advantages over other types of reviews: (a) a higher standard of the method and outcomes (Leonidou et al., 2017); (b) bias reduction (Di Vaio et al., 2022a, 2022b); (c) more reliability because the steps taken by the authors can be replicated (Wang & Chugh, 2014); (d) a concise outline of the research area examined (Di Vaio, Hassan, et al., 2023); and (e) the presentation of the foundations on which author can develop and share new conceptual model (Di Vaio et al., 2022a, 2022b; Di Vaio, Latif, et al., 2023). An integrated qualitative approach was used in this research.

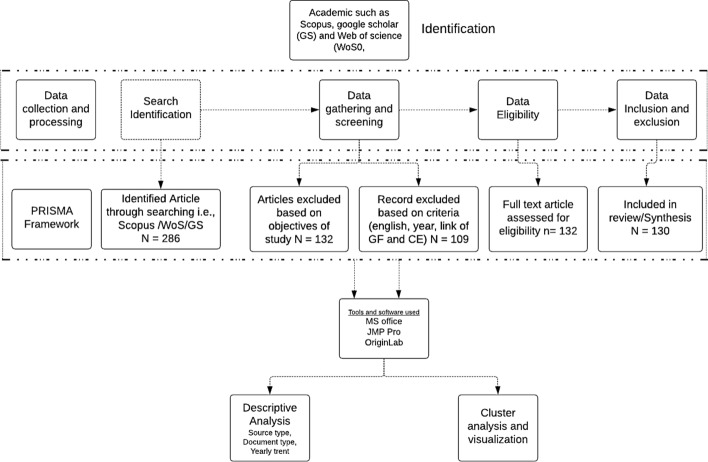

To conduct a comprehensive analysis of the various studies relevant to the topics of interest of this research, bibliometric reviews were employed, utilizing statistical tools to gain a thorough understanding of current trends, methodologies, journals, countries, particular subjects, and concepts that were important to our research. Following the study method shown in Fig. 1, a complete assessment of the literature was done (Kumar et al., 2022; Jabbour et al., 2020), following the same procedure of multiple previous researches. Given the abundance of literature on GF and CE, it was crucial to limit the scope of research to only relevant literature. A systematic approach (Ren et al., 2019) was employed, which involved defining research goals, developing search strategies, identifying appropriate keywords, language, sorting and excluding literature based on pre-defined criteria, and categorizing relevant literature for analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart explaining the methodology followed for the literature review

The research design has been structured in five primary steps, following the protocol established in the prior systematic literature review. The steps of the literature review were described in detail below.

In the first step, search strings have been used and defined with the combination of keywords, language, and year. The keywords for this literature review were constrained to GF system and CE. In the first step, search strings have been used and defined with the combination of keywords, language, and year. The keywords for this literature review were “Green finance”, “Circular economy”, “Sustainability”, and “Green innovation”. Furthermore, various researchers have different definitions for the phrase “green finance”. On the other hand, the definitions’ scope and content are comparable. The process of keyword selection was conducted through a focus group comprising of five researchers who work in the field of GF and CE. Furthermore, the validity of the search query was determined by comparing the selected keywords with additional terms utilized in the respective papers identified in the initial list. The analysis of keyword frequency demonstrated the importance of a specific keyword “Green bonds”, “Green credit”, “Environmental finance”, “Climate finance”, “Green loans”, “Sustainable production”, “Carbon finance”, “Green climate fund”, and “Funds for environmental initiatives”. Information was gathered from different databases, including ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Google Scholar (Ren et al., 2019). The relationship between the GF and CE was properly taken into account when conducting this literature review. To ensure the consistency and quality of the data studied, it was decided to only include peer-reviewed literature on the topic of GF and CE and find the link between these, although there were many valuable case studies, reports and articles by non-governmental organizations, companies, and governments on this topic. We decided for this approach for two main reasons: first, to focus on the current and state-of-the-art scientific research in the field of GF and CE; and second, to avoid the risk of potential biases or conflicting interests that could be present in non-scientific sources because non-scientific data may be prone to share success stories, instead than application failures. However, it was acknowledged that even scientific literature can sometimes present a biased view of the topic (Bjornbet et al., 2021; Diaz Lopez et al., 2019).

In the second step of this study, the scope of the review was limited to English language literature published between 2011 and 2022. It corresponds to the Identification step in PRISMA (Fig. 1) (Di Vaio, Hassan, Chhabra, et al., 2022; Di Vaio et al., 2022a, 2022b; Di Vaio, Hassan, et al., 2023; Di Vaio, Latif, et al., 2023; Martin et al., 2021). The focus of these literature review was limited to CE and GF concept. The second and third steps involve Screening (inclusion or exclusion) and eligibility checks (check whether it corresponds with the research question or objective). Initial search provided the 286 papers in academic data search (Fig. 1). The publications were selected based on their suitability for the review goals and question after doing the content analysis of the abstract and conclusion. Using the second and third step of PRISMA (Di Vaio, Hassan, Chhabra, et al., 2022; Di Vaio, Hassan, et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2022), 130 articles were selected for the comprehensive review.

The fourth step consisted in an analysis of contributions to detect links, constraints, and restraints of GF in CE for the selected articles/documents (using the last step of PRISMA). The data collected from the stated sources were organized in Microsoft Excel (Perkhofer et al., 2019). In the fifth step, JMP Pro and OriginLab Pro softwares were used to generate maps, graphs, and visualizations (Betancourt-Rodríguez et al., 2023; Schwebach et al., 2022) (Appendix A. script).

Main findings

This section first provides a descriptive analysis of the literature selected and then investigates and defines the dimensions of the GF in CE twofold domain, also listing the types of GF tools that could be employed to support its fully adoption. Finally, it provides the key components of the domain analyses to define interactions among them.

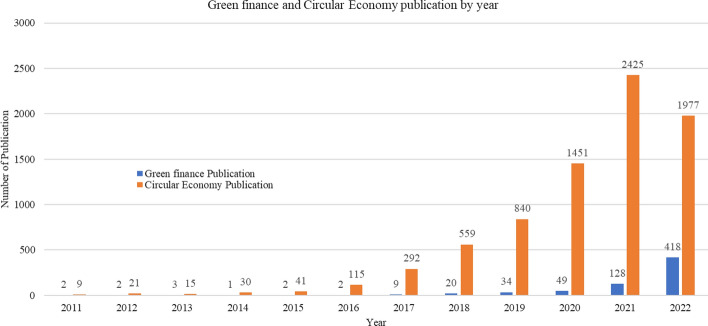

Descriptive assessment

The analysis articles' chronological order is shown in Fig. 2. It demonstrates a rise in articles that deal with CE and GF after 2016. It was observed that trend of CE has increased from 2017 and GF after 2019. The major article on CE (2425) was published in year 2021 and the GF (418) was in 2022. Yu et al. (2014) give a summary of the history of industrial cooperation and identify two phases in its growth. The authors note a development in theoretical development about CE and CE-related studies over the period of (2006–2012). However, the researchers point out that prior to this time (1997–2005), industrial symbiosis (IS) research work was confined to the evaluation of sustainable and environment park projects, the development of waste recycling and treatment networks, and the idea of industrial symbiosis (Yu et al., 2014). Whereas GF is discussed previously in Sect. 2.3, this result might be attributed to the fact that “GF” did not start becoming mainstream until after the year 2010. The number of research that were conducted from 2011 to 2022 is shown in Fig. 2. It has a tendency of fluctuations, and there has been no consistent rise since 2011 to 2019 (Debrah et al., 2022). There were a number of 'ups and downs,' and more curiously, there was only one research paper in certain years, including 2014. It is possible that throughout these years, the popularity of environmentally friendly financing had not yet considerably shown itself in environmentally friendly structures. The biggest number of research was published in 2021 and 2022, although the total was still very low. The number of studies published in 2022 is projected to increase toward the end of the year. The outcomes of the investigation led to several observations that were rather noteworthy.

Fig. 2.

Yearly publication on topic of circular economy and green finance

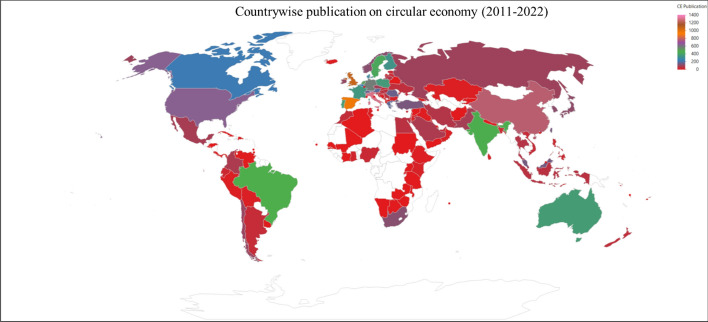

Further research has been carried out in order to identify patterns of geographic occurrence in the literature; Figs. 3 and 4 show the publication on CE and GF. Figure 3 demonstrates that a many studies on CE was carried out by the European authors in particular Italy (1313), UK (1080) and Spain (974). In this search, it was also found that China and USA were the next with the highest number of publications with 775 and 654. In light of this, the Delft University of Technology and Technical University of Denmark has been reported the most disseminated one since the author of most of publications was affiliated to this school (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Countrywide publication on circular economy (2011–2022)

Fig. 4.

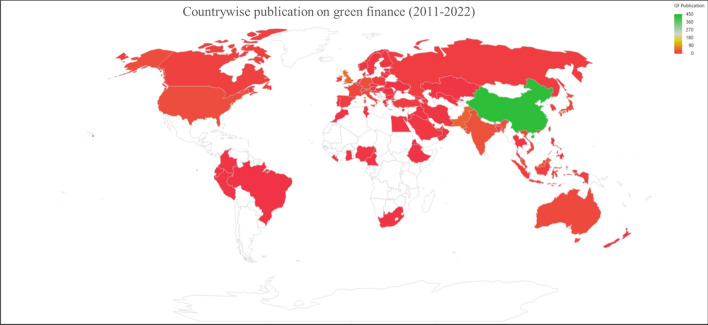

Countrywide publication on green finance (2011–2022)

Fig. 6.

Top 10 institutions

In terms of GF (the second major theme of this study) studies countrywide, in our literature review, we have not found major interest of authors in this topic. However, the research's findings include several intriguing insights that GF is gaining interest by authors to explore more in recent years. We have found Asia with major contribution, China (434), Pakistan (47), Malaysia (38), and India (39). Furthermore, other nations with large populations have demonstrated a great dedication to the field of study, including UK (51), Germany (28), and USA (25) (Fig. 4). In this regard, the major institutions were from China Jiangsu University, Wuhan University, and Beijing Institute of Technology (Fig. 6).

Research on the nexus of green finance and circular economy

GF, CE, and green revolution have emerged as research hotspots in finance and environmental research in the face of increasing serious ecological impact and environmental destruction. A portion of the literature recognizes that CE and GF were not two separate ecosystems, but rather have a connection in which they encourage and influence one another (Linnenluecke et al., 2016; Xiaofei, 2022). As a result, academics begin to merge CE and GF in order to validate the connection between the two functions. Others agreed that green financing may foster green initiatives from a variety of perspectives such as CE (Lewandowski, 2016; Orman, 2015). Green financial instruments, like green bonds and insurance, boost public participation into green industrial sectors and drive cleaner production innovation (Fernando et al., 2019). A diverse green financial system may improve CE efficiency and lead to the development of new green financial products (Chemmanur & Fulghieri, 2014; Fernando et al., 2019; Gilbert & Lihuan Zhou, 2017). According to Sachs et al. (2019), financial institutions were more keen in fossil fuel projects than in ecofriendly efforts, partly considering green investments have a lower return on investment than fossil fuel investments and were subject to future uncertainty. Two recommendations were made by Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino, (2019), on how to increase business participation in green investments. Developing initiatives to provide data on green credit is the first proposal. The second idea is to provide to shareholders a portion of the tax revenue that was initially generated as a consequence of the positive ripple effect of providing clean energy. They think these two methods can increase their return on investment while reducing the risk associated with green initiatives.

There has been no single study on Nexus, but some authors had carried out study in subareas of CE such as Battiston et al. (2020) investigate the Austrian green financing industry. They forecast that yearly development in Austria's green economy would reach EUR 17 billion between 2021 and 2030. They believe that state funding is insufficient and that commercial resources should be organized to support sustainable (or environmental) initiatives. They also contend that green financing will be a significant step toward reaching this aim. They admit several existing flaws in Austria's financial sector. They believe that the Austrian industry for sustainable financial services is immature by worldwide standards, that mutual funds control it, and that institutional investors drive it rather than private companies. They also point out that client awareness of sustainable financial solutions is currently low in Austria. According to Battiston et al., (2020; Rasoulinezhad and Taghizadeh-Hesary, (2022); and Ren et al., (2020), there is no connection among GF, ecofriendly energy usage, and energy efficiency in the short term due to factors such as undesirable political associations, exogenous shocks, and financial systems. As a result, the research of causal relationships is both instructive and useful to legislators. Some governments, however, significantly promote the growth of the green financing sector. The top ten economies that promote GF, USA, Norway, Hong Kong, UK, Canada, New Zealand, Denmark, Sweden, Japan, and Switzerland that qualify as “Green Leaders” have had significant economic development, increased urbanization, reduced CO2 footprints, and increased the share of renewable energy usage to their overall energy usage (Saeed Meo & Karim, 2021). However, many research studies have shown that green financing has a favorable influence on environmental sustainability (Flaherty et al., 2017; Zhou & Cui, 2019). According to Wang and Zhi (2016), GF is important for properly controlling negative impacts on the environment and optimizing ecological and economic reserves. Ng (2018) GF is an economic action that supports green improvement, improves material use, and responds to climate change. In contrast to traditional finance, GF promotes environmental preservation, sustainable industry, and sustainable growth (Falcone & Sica, 2019; Kang et al., 2019; Zhou & Cui, 2019). In Zhou and Cui (2019), GF improves the environment and boosts an industry's corporate social responsibility. More finance for environmental protection, as well as financial tools particularly created for climate-friendly initiatives, can contribute in the achievement of ecological, social, and governance (ESG) targets (Tolliver et al., 2019). Furthermore, green credit may provide economic help for national SD if it meets with environmental standards (An et al., 2021).

GF laws might place variability on enterprises' relief; resources companies are vulnerable to financial limits, which will facilitate companies' financial flows by limiting R&D spending for sustainability practices (Yu et al., 2021). Chang et al. (2019) demonstrated that the current financial institution's economic markets are incapable of meeting the need for sustainable innovation. Limited GF availability and interest rates may hinder company engagement in financial help for sustainability practices. Overall, there are several works on GF and sustainable development that give further information and motivation for this study. Figure 5 displays the papers published on the connections between the CE and GF. We have not found many publications but limited from China (5), France (3), and Italy (2). Because of the small number of studies that have been done so far in this, the results suggest that this is a developing, relatively young study topic with significant potential for future work. Future research in this area should help practitioners and policymakers make the most of funding opportunities and encourage the CE as a means of addressing environmental problems like climate change (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Countrywide publication on cross theme (green finance and circular economy)

Methodological characteristics of green finance in circular economy research

The methodological features of the research that have been evaluated range in terms of the techniques used for analysis and data collection. Prior research has used survey questionnaires, consultations, qualitative document or document analyses, review of literature, case studies, archival/statistical data, and hybrid approaches to collect data. The most frequent approach, employed in research, is reports, which include published articles, qualitative document analysis, and research studies. Archival/statistical data, survey questionnaires, and interviews were the main approaches with research published in scientific databases. Di Maio et al. (2017) conducted research on assessing CE and resource efficiency using market value method; the resource efficiency of numerous Dutch sectors was assessed using the novel technique and contrasted with a conventional mass-based technique using standard industry data from Statistical Netherlands. Various techniques were employed for data processing after data gathering. The observations were divided into five categories based on the methods used to analyze the data: (1) statistical analysis (or descriptive statistics), (2) qualitative examination (content or report analysis), (3) econometric examination, (4) hybrid analysis and (5) computational analysis (including artificial intelligence (AI) processes) (An & Pivo, 2020; Di Maio & Rem, 2015a, 2015b; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). Liu et al. (2021) measured the total element rate of the sustainable economy and the progress of GF using the epsilon-based measure model and the entropy approach. In China, they conducted research on the long-term connections between environmental regulation, GF, and green total factor productivity. They discovered in their research that green financing does play a big part in fostering high-quality economic growth, where industrial structure modernization and technology innovation both play a portion of the intermediary function. A study on green revolution countermeasures of strengthening the CE to GF under big data demonstrates that the ecofriendly innovation is considerably encouraged by the regression coefficients of green financing, environmental legislation, and their relationship, which were 0.1598, 0.0541, and 0.1763, respectively. Accessibility, higher education, and per capita gross domestic product had regression coefficients of 0.0361, 0.0819, and 0.0686, respectively, which might considerably encourage green initiatives (Yaoteng & Xin, 2022). Pan et al. (2022), in their study, sought to determine whether investors seek a risk premium for enterprises transitioning to low-emissions operations in nations where high polluters from natural resource-related companies have strong market dominance. Between 2011 and 2020, they employed a time-series selection of enterprises from six GCC nations to integrate an emission-based risk component into the standard asset pricing methodology. According to their results, carbon pollution is consistently valued in stock market returns. As a result, investors will need greater incentive to include low polluters in their investments to compensate for more polluting but dominant businesses, resulting in an increased cost of capital for green enterprises. We have not found a cross field research on CE in GB or GB in CE. There is a need of research study in two of the study areas, GF-in-CE barriers and drives, and CE-in-GF solutions and patterns.

The circular economy and its financing

Making the transition from the linear economy to the CE demands modifications in four essential components: materials and product development, marketing strategies, organizational structures, global reverse networks and enablers (AlAhbabi & Nobanee, 2020). Moreover, numerous resource efficiency efforts by insurance and banking companies are emerging in reaction, including peer-to-peer financing, zero-waste, repurpose, product leasing, remanufacturing, and reverse manufacturing (Dewick et al., 2020). It is necessary to make the transition to a new “circular” approach based on “Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle” of materials, which enables one to “close the loop” in the operation of financial systems and offers advantages to the economy and the environment at many levels of assessment (Ghisetti & Montresor, 2020). These progressions imply that governments and the financial sector are more devoted than ever to supporting CE initiatives, with the European Investment Bank's (EIB) pledge to invest EUR 10 billion (USD 12 billion) by 2023 as part of the Partnership Initiative CE by method of loans, equity investments, assurances, and the creation of creative financing structures for both public and private initiatives serving as an especially notable example (Lewandowski, 2016; Linder & Williander, 2017; Stahel, 2012). Furthermore, Intesa Sanpaolo introduced the CE Plafond, a financial instrument designed to aid in the shift to a CE. Within the 2018–2021 Business Plan, the CE Plafond, containing of € 5 billion (recently increased to € 6 billion), is committed to the most innovative firms or initiatives in the CE area among all Italian and international market. The corporation recently issued a third Green Bond with an asset value of €1.25 billion, which will be used to fund green mortgages for the development or acquisition of energy-efficient houses (Ghisetti & Montresor, 2020; Heshmati, 2017; Patrick & Jan, 2021).

Recent articles have underlined the rise and potential of CE financing, but also the need to remove various current hurdles, improve openness by regulating transparency and standardization, and clarify terms and measurements for circular operations (Dewick et al., 2020; Ghisetti & Montresor, 2020; Hussein & Hamdan, 2020). Moreover, methods, techniques, and tools for social sustainability initiatives must be integrated in emerging frameworks, analytic concepts, and standards of CE financial instruments (Heshmati, 2017; Patrick & Jan, 2021). These initiatives are actual, present, and rising, and they have been warmly welcomed by supporters of a CE (Bhandari et al., 2019). We take advantage of this chance to take a step back and deliver a more measured, critical, and remedial review. From our vantage point, we must ask if these projects are motivated by a genuine commitment to sustainability, and how our idea of a CE is developing as new sets of stakeholders interact to shape the narrative (Dewick et al., 2020; Heshmati, 2017). What are the chances that viable resource efficiency concepts will be properly integrated in common company models? As countries seek to recover from the effects of the COVID-19 epidemic, the CE provides an appealing route ahead. With governments announcing millions of dollars in stimulation financing in response to the pandemic's economic and health effects, we have arrived at a critical juncture in utilizing forward-thinking public investments and incentivizing private investments toward a healthier, more adaptable, low-carbon CE approach (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2021).

Although CE financing is growing and the industry has an excellent interest, most enterprises currently lack sufficient funding (Lv et al., 2021). Furthermore, opportunities for SMEs to obtain venture funding and loans during the beginning and early growth phases can be very limited in comparison with the options open to existing organizations needing financial support for larger projects, such as changing their existing processes and supply chains (Linder & Williander, 2017; Linnenluecke et al., 2016). Corporate expenditure on the CE has risen in contrast to investment funding. Just Economics' working paper includes projections for corporate investment in CE techniques across a broad range of industries covering consumables (clothing and fabrics, technology), construction, transportation, food and drinks, agricultural, and nonspecific wastes (Dewick et al., 2020; Hussein & Hamdan, 2020). These areas contribute for the greatest rates of both pollution and resource consumption; housing, mobility, and food alone account for 70% of life cycle pollution (Mngumi et al., 2022; Muganyi et al., 2021). Despite rapid growth in the percentage of circular spending, it is still outpaced by linear expenses. Concerning the proposition types of GF papers are presenting strong connection with CE components such as technological innovation, environmental compliance, economic development, and industrial structure upscaling (Table 1). Furthermore, finding of this paper shows that not every paper writes about the financial resources needed to meet the CE concepts. A number of contributions are devoted to highlighting creative initiatives in maintaining circular economies, adding GF and big data analytics, assisting businesses in digitalizing inventory activities and traceability, and securing the efficiency and efficiency of the CE and GF (Clark et al., 2018; George et al., 2015; Soundarrajan & Vivek, 2016; Zhou et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Green finance and circular economy category analysis

| Authors | Field | Innovation in technology | Improving industrial structure | Environmental supervision | Superior economic development | Finance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geng et al. (2012) | CE | × | × | |||

| Mattila et al. (2012) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Aguilera-Caracuel and Ortiz-de-Mandojana (2013) | CE & GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Naustdalslid (2014) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Walls and Paquin (2015) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Haas et al. (2015) | CE | × | × | |||

| George et al. (2015) | CE & GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Ghisellini et al. (2016) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Sauvé et al. (2016) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Kirchherr et al. (2017) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Murray et al. (2017) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| D’Amato et al. (2017) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Spring and Araujo (2017) | CE | × | × | × | × | × |

| Cui et al. (2018) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Korhonen et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Kalmykova et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Reike et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Baral et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | × | × |

| Soundarrajan and Vivek (2016) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Esposito et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Sandoval et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Zhong and Pearce (2018) | CE | × | × | × | × | × |

| Clark et al. (2018) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Falcone et al. (2018) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Zucchella and Previtali (2019) | CE | × | × | × | × | × |

| Zhang et al. (2019) | GF | ×× | × | × | × | × |

| Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino (2019b) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Schroeder et al. (2018) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Belaud et al. (2019) | CE | × | × | |||

| Hahladakis and Iacovidou (2019) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Frishammar and Parida (2019) | CE & GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Eriksen et al. (2019) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| He et al. (2019) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Zhou et al. (2020) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino (2020) | CE & GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Jabbour et al. (2020) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Ghisellini and Ulgiati (2020) | CE | × | × | × | × | × |

| Jabbour et al. (2020) | CE | × | × | |||

| Rizvi et al. (2020) | CE | × | × | |||

| Borregan-Alvarado et al. (2020) | CE | × | × | |||

| Taghizadeh-Hesary and Yoshino (2020) | GF | × | × | × | ||

| Kumar et al. (2021) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Bag et al. (2021) | CE | × | × | ×× | × | × |

| Patwa et al. (2021) | CE | × | × | × | ||

| Yu et al. (2021) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Lv et al. (2021) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Bongers and Casas (2022) | CE | × | × | × | × | |

| Taddei et al. (2022) | CE | × | × | × | × | × |

| Kumar et al. (2022) | GF | × | × | × | × | × |

| Saeed Meo and Karim (2021) | GF | × | × | × | × | |

| Total | 48 | 46 | 39 | 44 | 26 |

×-they talked about the mentioned areas in their research

Green finance and circular economy concepts

Sustainable finance and investment (SFI), on the one hand, finances to promoting long-term sustainable global development (Cunha et al., 2021) and climate financing funds climate change adaptation and mitigation projects (Ram Bhandary et al., 2021; Steckel et al., 2017). GF, on the other hand, covers primarily environmental financing and all other economic products and services focused on a larger number of environmental goals, such as 3Rs, industrial pollution management, and natural resource and ecosystem protection (Debrah et al., 2022; Dewick et al., 2020; Xiaofei, 2022). According to Zhang et al. (2019), financial development is an important determinant of CE future advancement. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was formed in 2010 by 194 nations with the goal of providing financial assistance to developing countries in order to reduce GHG emissions and prepare for climate change. Since then, the phrase “GF” has featured regularly in publications by global groups and national governments. Academics have also paid close attention to relevant topics. GF, on the other hand, remains poorly defined and is frequently confused with sustainable and climate financing. Some researchers studied the effect of GF on environmental issues and discovered that GF improves ecological sustainability (Debrah et al., 2022; Ji & Zhang, 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Furthermore, authors have pointed out the same for the CE. CE isn't just seen as a way to protect the environment. They also say that it is good for the economy because it saves money, creates jobs, and has innovative and disruptive business strategies that transform or challenge the way business is done (Antikainen et al., 2018; Jinru et al., 2021). Because of the multidimensional nature of CE business models in comparison with traditional business models, as well as the consequences for other sectors of the economy, companies are searching for opportunities inside the CE or collaborating with companies or financial institutions that have shifted or helped towards the CE in order to profit financially (Jinru et al., 2022; Mngumi et al., 2022). The GF is a strategic approach to incorporate the financial sector in the shift to resource-efficient and low-carbon sectors, as well as adaptation to climate change. It also helps in the implementation of the green innovation agenda (Mngumi et al., 2022; Umar et al., 2021). The previous study identified various advantages of GF, such as it promotes technical dissemination for environmentally friendly facilities, supports in the building of competitive advantage, contributes to corporations, and enhances economic prospects (Muganyi et al., 2021; Soundarrajan & Vivek, 2016; Umar et al., 2021). Table 2 provides a classification scheme that defines several forms of green financing, and their implementations green financing is clearly relevant to CE adaptation activity and it is updated in table by (Debrah et al., 2022). This paper shares the review that can be used to make suggestions for future research, legislation, and practice in the parts CE.

Table 2.

Green finance applied to circular economy

| Type of finance | Definition | Categories of green finance tools a | CE benefits a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green finance | “Green finance” includes financing eco-friendly resources, initiatives, and methods. It contributes toward a sustainable economy | Climate change mitigation includes lowering greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). Adapting to climate change entails changing ecological, social, or economic systems to account for climatic changes and their repercussions |

Emission reduction Economic development Adaptation to change of climate Energy efficiency projects Sustainable development projects Pollution Control Waste processing and recycling |

Li and Shao, (2022), Liu and Xiong (2022), Peng et al. (2022) |

| Green bonds | Green bonds are new financial products designed to benefit people and the environment. Green bonds can be used by firms to fund investments like standard fixed-income instruments. Green bonds reduce CO2 emissions and prevent environmental damage | It promotes green business, renewable energy, green jobs, pollution avoidance, sustainable resource usage, etc |

CO2 emission reduction Energy efficiency Pollution reduction Sustainable wastewater and water management Eco efficiency Climate change adaptation Resource saving |

Gilchrist et al. (2021), ICMA (2022), Tang and Zhang (2020) |

| Green Loans | Any form of bank loan set aside specifically to put money into, or re-investing in, environmentally friendly new and old initiatives | It promotes renewable energy, environmental stewardship, pollution avoidance, and resource sustainability |

Sustainability Renewable energy Recycle Pollution control Green energy Green projects |

Brears (2022), ICMA (2022), Kortt and Dollery (2012) |

| Green climate fund GCF | To support the fundamental shift toward low-emission and climate-resilient options, eight key outcome areas have been prioritized, four for mitigation and four for adaptation | Limiting GHG emissions in developing nations and helping vulnerable communities adapt to climate change. Investing in creative technologies, corporate strategies, and procedures for climate innovation |

Carbon accounting GHG reduction Emission standard Energy efficiency Sustainable development Ecosystems and ecosystem services Hazard mapping |

Ashraf et al. (2020), GCF (2022), Khanna et al. (2022), Sivapathy et al. (2021) |

| Green funds | Green funds allow investors to support businesses that use greener production practices, renewable energy, and other eco-friendly technology | Climate change and ecologically responsible initiatives, including energy efficiency, agricultural, and waste management initiatives |

Cleaner production Renewable energy Environmentally friendly technology Emission reduction Waste management Energy efficiency |

Climent and Soriano (2011), Silva and Cortez (2016) |

| Climate finance | The funds required to cover the extra costs and risks associated with climate action, to foster the growth of potential for mitigation and adaptation to promote the study, creation, and application of new technologies, and to catalyze the transformation of development into one that is more climate intelligent | Climate change adaptation, such as building flood barriers for rising sea levels, and climate change mitigation, which includes attempts to reduce GHG emissions, such as renewable energy and energy efficiency programs |

Clean energy GHG emission reduction Extraction of renewable resources Low-carbon path Build resilience of countries to climate change |

Berrou et al. (2019), Hong et al. (2020), Khanna et al. (2022) |

| Climate Bonds | Climate Bonds Action seeks to move debt-based investment resources towards enterprises and activities that will assist meet the Paris Agreement's 2 °C global warming target | Climate-related fixed-income investing services. They're issued to increase funds for climate change mitigation or adaptation plans such GHG emissions reduction, clean energy, and energy efficiency | Same as discussed in Climate finance | Berrou et al. (2019), Shinde (2021) |

| Green credits | Green credit is when banks include economic and environmental factors in lending choices | Green industries, investment restraints in polluting and overcapacity sectors, and withdrawal of funding from businesses that have been particularly focused for their detrimental environmental effect |

Greening industries Pollution reduction Growth of capital-intensive Energy-intensive Regional energy conservation and emission reduction |

Lyu et al. (2022), Xiao et al. (2022) |

| Sustainable/Green banking | “Financial goods and services that serve human needs, protect the environment, and generate money”. Sustainable banking and related terms such as CSR, ethical-banks, eco-banking, and green-banks have been widely researched since they promote environmental sustainability | Adopting energy-efficient street lighting, decreasing financing costs, installing rooftop solar panels, increasing green technology sectors, and retrofitting business and residential buildings are some strategies to attain these aims |

Climate-resilient infrastructure Energy Efficiency Water management Green technology Waste management Renewable energy Low-carbon, and |

Aracil et al. (2021), San-Jose et al. (2011), Yip and Bocken (2018) |

| Sustainable finance | Sustainable finance supports long-term funding in economically viable projects and activities by incorporating ESG elements into financial sector investment possibilities | Includes not just environmental, green, and social finance but also broader concerns about the funding recipients' long-term financial viability and the role and strength of the larger economic mechanism in which they participate |

Climate change mitigation and adaption Green, and social projects Water management Energy management |

Fatemi and Fooladi (2013) |

| Environmental finance | Environmental finance investigates the economic impact of environmental change on corporations and sectors and the need for a more sustainable economic model. The topic integrates environmental and financial research to produce market-based financial and policy solutions to climate change and other planetary system changes | Investment and funding aimed toward improving environmental conditions (water, soil, air etc..) or protecting the environment from potential harm |

Waste and wastewater Green buildings Solar panels Sustainable transport Solar energy systems Agriculture and land use Forestry Environmental resources Environmental technologies Infrastructure |

Labatt and White (2002), Lee et al. (2013), Linnenluecke et al. (2016) |

| Sustainability bonds | Financing used to fund projects with positive environmental and socioeconomic impacts that are also in accordance with the Paris agreement's target are known as “sustainability bonds” | Any form of secured loan with principal, interest, and any other earnings are all intended for use in financing or refinancing green and social initiatives | Same benefits as discussed in the portion of sustainable finance above | AlAhbabi and Nobanee (2020), Debrah et al. (2022) |

aKindly note that the above project proposals are not exhaustive

GF in CE: key components and interactions

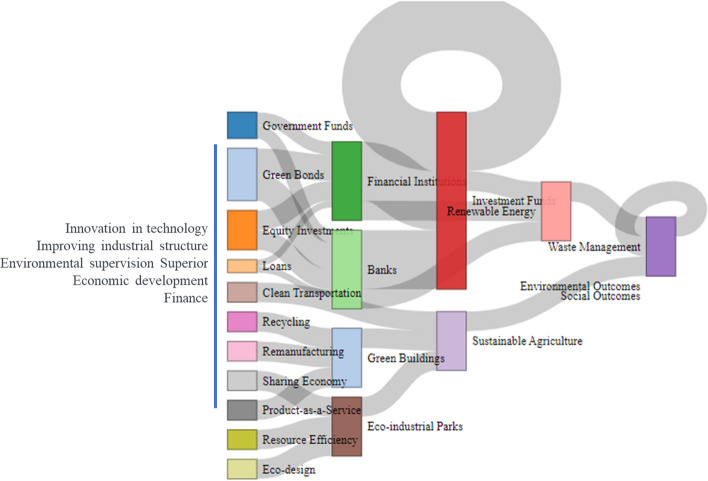

A crucial element in the shift to a more sustainable and CE is green money. GF promotes the adoption of CE principles and supports sustainable development by allocating financial resources to environmentally and socially responsible projects (Liu et al., 2021). This framework (Fig. 7), which illustrates the movement of financial resources, information, and materials among different stakeholders, sectors, and strategies, provides an overview of the green GF within a CE.

Fig. 7.

Navigating green finance in the circular economy: Key components and interactions

The financial inputs, which include government money, green bonds, equity investments, loans, and other sources of capital, are at the heart of GF. These funds are crucial for accelerating the transition to a CE, innovation in technology, improving industrial structure, and supporting environmentally friendly initiatives. In order to direct investments toward projects that adhere to the principles of the CE, intermediaries like financial organizations, banks, and investment funds play a critical role in facilitating the allocation of these resources (Flaherty et al., 2017; He et al., 2019; Yaoteng & Xin, 2022). The CE’s “targeted sectors” include a broad range of businesses and projects that aim to minimize their negative environmental effects and maximize their efficient use of resources. Among these industries are clean transportation (Tolliver et al., 2019), eco-industrial parks (Sakr & Abo Sena, 2017), green buildings (Ikram, Ferasso, et al., 2021), waste management (Scharff, 2014), sustainable farmland (Hens et al., 2018), and renewable energy (Tolliver et al., 2019). Investments in these areas promote innovation, create employment, and advance sustainable development, all of which help to create a more circular and resource-efficient economy.

Recycling, remanufacturing, product-as-a-service, sharing economy, resource efficiency, and eco-design are just a few examples of the CE strategies that businesses and governments can use to minimize waste, increase product lifespans, and decrease the need for raw materials (De Oliveira Neto et al., 2016; Ghisellini & Ulgiati, 2020). These tactics boost long-term revenue and competitiveness in addition to minimizing the environmental impact of economic activity. Various stakeholders, including governmental organizations, banking institutions, non-governmental organizations, businesses, small and medium-sized enterprises, and private investors, make up the GF ecosystem (Falcone et al., 2018; Pan et al., 2022). Each of these parties has a particular responsibility for advancing and putting into practice CE principles, and systemic change cannot be achieved without their combined efforts. The development of the GF environment and the promotion of the adoption of CE principles are greatly influenced by policy and regulatory frameworks. Policies like carbon pricing, tax breaks, and green procurement can encourage the demand for sustainable goods and services while also creating favorable market circumstances for green investments (Majumdar & Sinha, 2019; Steckel et al., 2017). Governments can make sure that financial resources are allocated to initiatives that improve the environment and societal well-being by setting clear rules, criteria, and incentives.

Delivering favorable environmental and social results is the ultimate goal of GF in a CE. Green funding can support biodiversity preservation, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and increase resource efficiency (Maio & Rem, 2015a, 2015b; Yin et al., 2012). Socially, GF can help with the development of new jobs, the reduction of destitution, and the enhancement of health and wellbeing. Stakeholders can evaluate the success of GF initiatives based on these results and then make educated decisions about future allocations by doing so. The comprehensive review performed found that GF is not effective without monitoring and reporting because they allow stakeholders to follow the development and results of their expenditures. The effectiveness of GF efforts in promoting CE practices can be determined by looking at key performance indicators like the amount of GF allocated, the number of projects supported, and the environmental and social outcomes obtained.

Discussion

Green financing and the road to the circular economy

This study demonstrates that the majority of authors (e.g., Khorasanizadeh & Parkkinen, 2015; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al., 2020; Severo et al., 2015; Yaoteng & Xin, 2022; Zhao et al., 2018) concentrate on the environmental developments in performance of the CE instead of taking a broad view on all aspects of CE and environmental sustainability; however, this is also right for a number of researchers in the end field. Whereas the environmental approach used by sustainable development can range from openly and implicitly comprehensive to the analysis of specific concerns, the majority of researchers conceptually limit the CE to resource input, waste output, and pollution output. Other concerns, such as financial needs, climate change, land usage and ecological degradation, are only alluded to by the latter researchers (e.g., Bongers & Casas, 2022; Geng et al., 2012; Kalmykova et al., 2018; Lv et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2017; Song et al., 2021). Despite this, the present worldwide environment presents a threat to the finance accessible to developing countries. The pandemic exacerbates the debt burdens of developing countries, which reduces the amount of public funds accessible for projects for sustainable development. The OECD anticipates that foreign private finance inflows might decline by $700 billion in 2020 relative to 2019 levels, which would be 60 percent more than the effect of the global economic crisis of 2008 (OECD, 2020). Such consequences would heighten the possibility of significant development setbacks, which would increase global susceptibility to developing environmental and public health hazards, such as future pandemics, climate change, and other global public harms, such as biodiversity loss or plastics pollution (Bradford, 2018; IRR et al., 2017; Moss et al., 2013). The regulatory agencies encourage banks to offer green lending services and sustainable avenues for company financing via the securities market. The optimization of energy-saving resources and green financial strategies. The capital outflow process, as opposed to the capital movements method, restricts the growth of businesses with high levels of energy and pollution utilization. During functioning, the four following procedures will generate vast amounts of data (Yaoteng & Xin, 2022). Financial markets technique, financial outflow process, project planning method, and risk aversion method are the four communication processes of green financing to green innovation. The capital inflow system refers to financial institutions that invest extra money in protecting the environment and energy-saving businesses to encourage companies to engage in green development activities per the requirements of applicable national legislation (Tara et al., 2015). The regulatory authorities encourage banks to offer green lending facilities and green pathways for company financing via the securities market. Government agencies enhance the financial process and promote sustainable funds to invest in firms dedicated to environmental preservation and energy conservation (Yaoteng & Xin, 2022). The capital outflow system is diametrically opposed to the capital influx process, which restricts the growth of businesses with high emissions and energy use levels. The project selection method enables GF to serve as a channel for firms and investors to continue contact. In this setting, businesses with superior protection of the environment abilities can acquire financing from banking firms, and financial institutions can also identify protection of the environment and energy-saving companies with competitive improvements. The risk-aversion process indicates that while security of the environment and energy-saving firms have wide growth opportunities, their financial risk is greater than that of conventional businesses (Zheng & Meng, 2018). The initial two processes were responsible for the capital-oriented impact, whereas the last two were responsible for the innovative decision-making impact (Zhao et al., 2018). GF as a whole plays a greater role in supporting green development under formal environmental legislation. Formal environmental legislation plays a greater role in supporting green revolution in the context of green financing.

The size of the company is an important determinant for the feasibility of a circular system; according to Aranda-Usón et al. (2019), the more challenging it will be to raise capital, the small the firm. Another issue is the expense of the circular manufacturing process, which will depend on the size of the businesses, possibly as a result of scale advantages. Therefore, using public policy and tax incentives to boost this kind of effort might be one method to promote the adoption of circular processes by small and microbusinesses. In this manner, relevant research questions might be found based on prior publications. First, how do public policies affect and how crucial are they to the economic feasibility of CE projects for micro- and small businesses? What role do public finance lines play in small and microbusinesses' adoption of circular manufacturing practices (Bartolacci et al., 2017; Sarmento et al., 2022). Furthermore, the study by Jinru et al. (2021) found that the management, government/regulators, and policymakers are enormous in order to boost efficiency and reach CE; their research first suggests that a firm should integrate varied green efforts with on-the-ground activities while sticking to the established sustainable production. The CE facilitates the cost-effectively transforming of linear economic systems into circular systems for long-term sustainability. CE enterprise practices can support in resolving resource deficiency challenges while enhancing the company's profitability. In addition, sustainable production will assist a business's key strengths in establishing sustainability across the company (Gbolarumi et al., 2021). It is now recommended that stakeholders integrate green systems and procedures while developing a sustainable plan of action and monitoring the outcomes produced through the integrity of their SP. Second, in order to boost the pace of CE adoption. Green financing enables buyers and producers to collaborate in mitigating climate change, provides transparency into the activities getting financed, and enables financiers to monitor the impact of their purchase. Why Finance Circularity with GF ? Increasingly, the banking industry recognizes the benefits of sustainability. It has been noted that customers that are environmental leaders are more inventive, have superior financial performance, and have higher credit ratings. The risk is a last factor in the relationship between the CE and financial elements. Some research emphasized the increased risk exposure simply due to the CE's new manufacturing mechanism. The environmental risk that the linear system represents must be taken into account (Falcone et al., 2018; Soundarrajan & Vivek, 2016). How can one balance the hazards of the CE with the environmental impacts that the existing arrangement poses as a result? Is it feasible to develop a financial ratio or financial report that more objectively reveals and assesses such facets? A significant number of papers indicate the absence of metrics to assess the effectiveness of the CE or provide policymakers with evidence in support of this deficiency (Cui et al., 2018; Ghisellini & Ulgiati, 2020). The life cycle of substances (Gigli et al., 2019), financial environmentally friendly innovation developments (Portillo-Tarragona et al., 2018), green and smart cities (Sarmento et al., 2022), CE-related blockchain technology (Rieckhof & Guenther, 2018), environment friendly accounting method and its applications (Yin et al., 2012), and other topics related to the CE were identified in other analyses that were not focused on corporate finance issues. The banks that control more assets and resources to sustainable enterprises and assist them in facilitating the shift to a low-carbon market develop a robust portfolio. Therefore, sustainability is currently a commercial potential for the financial sector (Jinru et al., 2021).

Implications to theory and practice

The results of this comprehensive review have important effects on both theory and practice. This research adds to the body of knowledge by creating a link between GF and the CE. This was completed by conducting a comprehensive literature review as well as a descriptive and theme assessment. The collaborative interaction and feedback among the numerous variables involved in this relationship were examined using the coupling coordination level framework. This research also emphasizes the significance of financial indicators and incentives, such as project funding, GF, company and consumer understanding, in encouraging the implementation of sustainable management practices and the shift from a linear to a CE. In practice, this study will help to raise knowledge of CE and the use of GF among professionals from many industries. Indeed, the findings of the literature study provide important suggestions and recommendations that governments, institutions, academics, and businesses may employ as management insights. Managers might conveniently increase their understanding about processes, practices, and technological explanations that could be beneficial in assisting their CE initiatives through them, depending on their need to concentrate on various aspects of CE and how finance can assist them in achieving CE. Furthermore, the unique characteristics of each sector, as determined by the CE methods and technologies used, enable certain sectors in their transition to a CE. This study provides a roadmap for policymakers, businesses, and financial institutions to promote sustainable practices and economic growth while also preserving the environment.

Key lessons learnt

First, provided that adopting a CE has a strong theoretical environmental clarification and that businesses of all sizes will eventually be required to adhere to environmental legislation, it is essential to have financial measures that can demonstrate the positive effect on market share value. Business sustainability does not conflict with the activities of investors; this will serve as the primary motivation for the implementation of eco-friendly management initiatives, which can act as the missing financial reason and, as a result, as a mechanism for the shift from the linear to the CE. It is vital to go over the present difficulties and hindrances related to finances, market importance, and practice optimization. It is necessary to research how GF can help to increase the CE and investment possibilities. The second lesson is that there is an increasing demand for innovative funding tools to support CE projects. Traditional financing methods may not always be appropriate for CE initiatives, our review suggests, and there is a need to investigate novel financing models that can help enhance the CE transition. Third, financial, institutional, and national benchmarks are required to examine the growth of different circular businesses, and financial incentives through GF, project subsidies, and national, corporate, and consumer awareness are important. Finally, in order to realize the maximum potential of the CE, expenses, market value, and process optimization must be surmounted.

Research limitations and future directions

Researchers in the future should think about using a multidimensional conceptual framework to further investigate the connection between GF and CE. Researchers, practitioners and policy makers can use these findings to better understand the link in this twofold domain. As a foundation for future study and the development of government orders, Fig. 8 depicts the fundamental dimensions, constituent components, and interrelationships in the twofold field of GF and CE. The main levels of the conceptual model are the GF dimensions, the CE dimensions, and the additional elements (pertaining the technological, economic and social dimensions). In contrast to the CE, which focuses on sectors, initiatives, stakeholders, and collaboration, Green Finance is more concerned with financial instruments, mechanisms, as well as policy and regulatory frameworks. The financial, technological innovation, improving industrial structure, environmental supervision, and superior economic development components make up the additional elements.

Fig. 8.

Multidimensional Conceptual Framework: Exploring the Interconnections between Green Finance and Circular Economy

Providing financial backing and investing in R&D for technological innovation are two examples of the crucial roles finance plays in assisting GF, both of which are present in the framework as “Additional Elements”. “Innovation in technology” results in “Technological Advancements,” which consequently aid “Improving Industrial Structure” and “CE Sectors and Initiatives” in their respective changes. Proper environmental supervision affects the policy and regulatory framework and guarantees adequate monitoring and compliance. By maintaining economic development, “Superior Economic Development” helps improve the stability of the financial system.

Future research should look at the role that circularity and corporate sustainability may play in boosting GF and financial possibilities. Future research can also use empirical analysis to look at the connection between GF and CE innovation. Risks come with development in green financing and investing, and the more the risk, the greater the reward. The balance between risk and anticipated return in GF and investment is currently a topic with little research. Future research should examine the exchange between predicted green returns and green risk in considerable detail. Furthermore, the potential for green financing in emerging nations can be examined. It is also important to investigate how the difficult institutional and policy conditions impact the development of GF and investment industries in developing nations. Such research must consider the distinctive institutional and governmental constraints present in developing countries.

The fields of GF and the CE can build upon the complex conceptual structure. It provides an aerial perspective of the interconnected parts and how they work together, making it easier for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to see the possibility for cooperation. Future research efforts can aid in the advancement of scholarship and the development of policies and strategies to promote sustainable development through GF and CE initiatives by examining the pathways outlined in this framework.

Focusing upon the multidimensional conceptual framework and lessons learned, it is possible to develop a research roadmap that effectively addresses the current gaps within the domains of GF and CE. The present study proposes the identification of research directions that can address the aforementioned gaps. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of diverse financial instruments and mechanisms in advancing CE activities. The research can include various methodologies such as case studies, comparative analysis, or experimental designs to assess the efficacy of diverse financing tools and strategies on projects related to CE. Moreover, the research could potentially center on the identification of optimal methodologies, the examination of the effects of particular regulations on the advancement of GF and CE, and the investigation of the feasibility of standardizing policies across various nations or territories.

This study aims to analyze the contribution of different sectors towards the promotion of CE practices. It involves the identification of effective business models, innovations, and technologies that can be expanded and duplicated. The proposed research may encompass a variety of methodologies, including case studies, surveys, and comparative analysis, to investigate the role of various sectors in advancing the principles of the CE. Furthermore, the proposed study needs to evaluate the accessibility of monetary funds, investigate novel financing approaches, and recognize impediments to obtaining financial support for GF and CE endeavors. Through the exploration of these research directions, forthcoming studies have the potential to address the knowledge deficits within the domains of GF and CE, thereby furnishing significant perspectives for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers.

Conclusion