ABSTRACT

Cancer is a serious concern in public health worldwide. Numerous modalities including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, have been used for cancer therapies in clinic. Despite progress in anticancer therapies, the usage of these methods for cancer treatment is often related to deleterious side effects and multidrug resistance of conventional anticancer drugs, which have prompted the development of novel therapeutic methods. Anticancer peptides (ACPs), derived from naturally occurring and modified peptides, have received great attention in these years and emerge as novel therapeutic and diagnostic candidates for cancer therapies, because of several advantages over the current treatment modalities. In this review, the classification and properties of ACPs, the mode of action and mechanism of membrane disruption, as well as the natural sources of bioactive peptides with anticancer activities were summarised. Because of their high efficacy for inducing cancer cell death, certain ACPs have been developed to work as drugs and vaccines, evaluated in varied phases of clinical trials. We expect that this summary could facilitate the understanding and design of ACPs with increased specificity and toxicity towards malignant cells and with reduced side effects to normal cells.

Keywords: anticancer peptide, antimicrobial peptide, apoptosis, natural resources

Introduction

As a leading cause of death, cancer threatens human health and life worldwide.1, 2 Based on the report of the World Health Organization, cancer accounts for about 20 million deaths in 2020, including the occurrence of lung, prostate, colorectal, and stomach cancer in men, and breast, colorectal, lung, cervical and thyroid cancer in women.3 Cancer results from the transformation of normal cells into tumour cells that grow uncontrollably and go beyond their boundaries to invade the surrounding tissues and organs via the process of metastasis, which is the principal reason of death from cancer.4

The current strategies for cancer therapies mainly include surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, which serve as the most frequently used modalities for cancer treatment in clinic. Despite progress in anticancer therapies, the usage of these methods for cancer therapy is often related to deleterious side effects. For example, surgery generally can quickly remove obvious cancer cells from the body, but the process of operation often results in serious trauma, bleeding, infection, and other risks. Radiotherapy as a modality of cancer therapy, relies on the application of high-energy rays or radioactive substances to damage cancer cells or prevent cancer growth.5 However, radiotherapy often causes a wide range of side effects, such as tiredness and sore skin in the tumour area, due to the exposure of healthy cells and tissues around the tumour site to high doses of radiation.6 Chemotherapy as a systemic therapy, depends on the administration of chemical drugs into the body to kill cancer cells.7 But, most classical anticancer drugs lack the property to distinguish cancer cells from normal ones, thus resulting in systemic toxicity and adverse side effects (e.g., anaemia, gastrointestinal mucositis, alopecia, or cardiotoxicity).8, 9 And, long-term usage of anticancer drugs increases the risk of drug resistance through the development of mechanisms to deactivate or transport drugs out of the cells.10 Thus, the development or discovery of a new class of anticancer agents with low toxicities, high selectivity and overcoming the influence of drug resistance is urgently required.11, 12

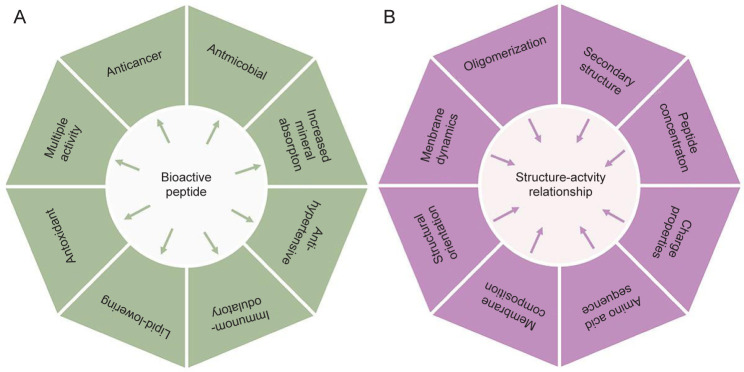

With the advance of biology and biomedicine, a great many bioactive peptides have been discovered and isolated from natural animal and plant sources, which exhibit antioxidant, antiinflammatory, antimicrobial and anticancer activities (Figure 1A).13 In this review, the recent studies on naturally occurring cationic antimicrobial peptides with anticancer activities for cancer treatment were reviewed.14 Most cationic anticancer peptides (ACPs) are usually short in length, with 5–50 amino acids, and mainly consist of positively charged amino acids, such as Lys and Arg and hydrophobic residues.15 Because of the presence of positively charged amino acids and high proportions of hydrophobic residues, ACPs can electrostatically interact with cancer cell membranes with net negative charges, and elicit a cytotoxic effect on cancer cells via disruption of cell membranes.16 Molecular sequences and chemical compositions of peptides can seriously affect the abilities to interact with cancers and the cytotoxicity (Figure 1B and Table 1).17 Because of their unique mechanisms of action, ACPs have many advantages, including low toxicity and chance of developing multi-drug resistance problems, compared with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, and thus offer the opportunity of developing a novel class of anticancer agents with improved cell selectivity for cancer cells and decreased side effects on normal tissues.18, 19 Due to the limitation of space, the information about pharmaceutical characteristics of therapeutic peptides, such as peptide design, synthesis, modification, and evaluation of peptide drugs is not included in this review. For further details on these aspects, the readers are referred to several recent reviews.2, 20-23

Figure 1. (A) Multipurpose bioactivities exhibited by peptides from natural resources, (B) Physicochemical and physiological factors of bioactive peptides that determine their anticancer activities.

Table 1. Effects of amino acid residues in ACPs on cancer cells.

| Amino acid residue | Amino acid properties | Action on cancer cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect on cell membrane interactions | |||

| Lysine | Positively charged, polar and hydrophilic | Disrupt cell membrane integrity and penetrate cell membrane, leading to cancer cell cytotoxicity | 24 |

| Arginin | |||

| Histidine | Induce cancer cytotoxicity via membrane permeability under acidic condition | 25, 26 | |

| Glutamic acid | Negatively charged, polar and hydrophilic | Antiproliferative activities on tumour cells | 27 |

| Aspartic acid | |||

| Effect on cancer cell structure | |||

| Cysteine | Polar, non-charged | Interact with numerous cell surface receptors for stabilizing and maintaining extracellular motif/domain structure | 28 |

| Proline | Non polar, aliphatic | Membrane interaction and conformational flexibility of peptide chains | 29 |

| Glycine | Membrane interaction and conformational flexibility | 29 | |

| Phenylalanine | Aromatic | Enhance the affinity with cancer cell membrane | 30 |

| Effect on cancer cell metabolism | |||

| Methionine | Polar, non charged | Reduced methionine will arrest cancer cell proliferation | 31 |

| Tyrosine | Aromatic | increase cytotoxic activity | 32 |

| Tryptophan | Aromatic | binding at the major groove of nuclear DNA | 33 |

Note: Reprinted from Chiangjong et al.17

Characteristics of Cancer Cells for Selective Treatment by Anticancer Peptide

Although the selectivity and mechanism of membrane disruption by ACPs to kill cancer cells are not yet fully understood, the structural and compositional differences between cell membranes of cancer cells and normal cells may be responsible for the selectivity of ACPs towards cancer cells over healthy cells.34 Compared with normal cells, malignant cells show several different characteristics with regard to the membrane components.35 For example, the membrane of malignant normally carries a net negative charge because of the presence of a higher number of anionic components such as the phospholipid phosphatidylserine, O-glycosylated mucins, sialylated gangliosides and heparin sulphate than normal cells, which contributes to the selective cytotoxic property of ACPs.36 Another distinctive trait of malignant cells is associated with the content of cholesterol within cell membranes.37 Cholesterol is an integral component in cell membranes of eukaryotic cells to regulate membrane fluidity. Normal cells have large amounts of cholesterol which works as a protective layer to modulate the cell fluidity and block the entrance or passage of cationic ACPs. In contrast, most malignant cells have increased membrane fluidity, due to the low content of cholesterol in cell membranes, which may make them susceptible to ACPs. In addition, cancer cells also contain an increased number of microvilli, in contrast to healthy cells. The presence of microvilli with irregular size and shape on cancer cells can increase the surface area of cells for ACP binding and interactions,38 influences cell adhesion, and the communications between cancer cells and their environments, and facilities the specific interaction of ACPs with cancer cells. Therefore, the high selectivity and cell-killing efficacy of ACPs towards cancer cells over normal cells could attribute to different compositions in cell membranes, as well as higher fluidity and surface areas of cancer cells than normal cells. Relying on electrostatic interactions, ACPs with positive charges and amphiphilicity target and bind the membrane of cancer cells with highly negative charges, destabilise and destroy cell membranes through hydrophobic interactions, leading to cell necrosis.2

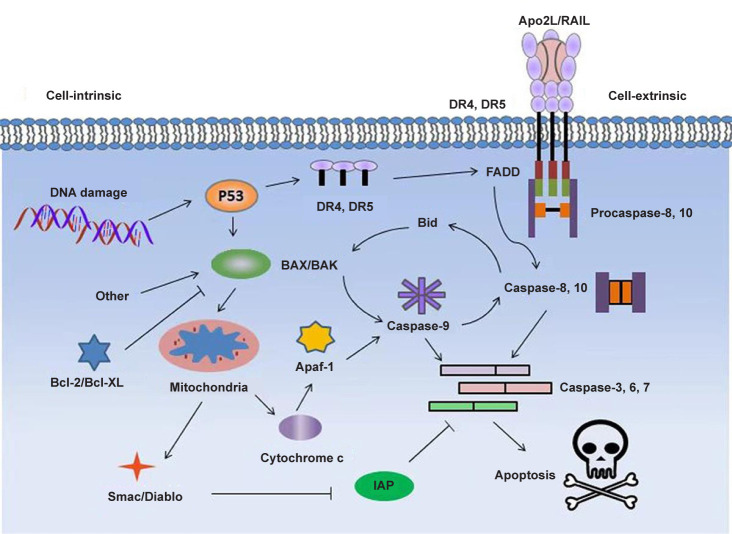

With in-depth studies, scientists discovered that certain membrane-active peptides can disrupt the membrane of mitochondria, causing the release of cytochrome c, after they were internalised inside eukaryotic cells.39 The released cytochrome c from damaged mitochondria to cytosol can induce oligomerization of Apaf-1, activation of caspase-9 and the transformation of pro-caspase-3 to caspase-3, initiating apoptosis in many cancer cells.40 For example, the cationic membrane-active peptide (KLAKLAKKLAKLAK) has been shown to target mitochondria and trigger apoptosis after fusing to a CNGRC homing domain (Figure 2).41

Figure 2. Proposed signaling pathways for induced apoptosis of cancer cells by pro-apoptotic peptides. Apaf-1: apoptotic protease activating factor 1; Apo2L: Apo2 ligand; Diablo: direct IAP binding protein with low pI; DR: death receptor; FADD: Fas associated via death domain; IAP: inhibitor of apoptosis protein; TRAIL: tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

Besides direct disruption of plasma or mitochondrial membranes, some ACPs can also kill cancer cells via other indirect pathways, such as gene targeting and immunomodulation.42, 43 For example, melittin, is an ACP consisting of 26 amino acid residues, and can preferentially activate phospholipase A2 in cells that overexpress the Ras oncogene, and result in selective destruction of cells. In another study, scientists discovered that a histidine-rich alloferons derivative could stimulate properly the activity of the natural killer cell of lymphocytes in a mouse model for tumour killing.44 Currently, more and more evidence suggests that drugs with immunomodulatory effects could provide beneficial effects for cancer therapies.45

Properties and Classification of Anticancer Peptide

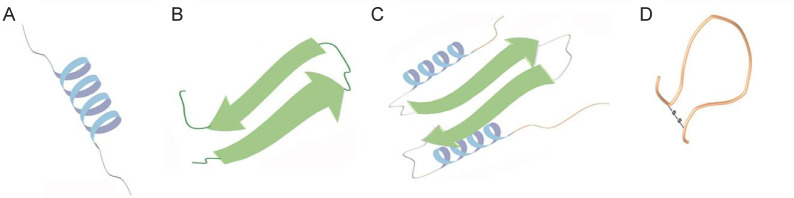

Based on their secondary molecular structures, most ACPs can be classified into four typical classes (Figure 3): (1) α-helices (e.g., bovine myeloid antimicrobial peptide (BMAP), melittin, cecropins, and magainins); (2) β-sheets (α- and β-defensins, lactoferrin and tachyplesin I); (3) ACPs with extended structures and enriched with glycine, proline, tryptophan, arginine, and/or histidine residues; and (4) cyclic loops (diffusa cytides 1–3).46

Figure 3. Schematic illustration of ACP structures containing α-helices (A), β-sheets (B), extended structures (C) or cyclic loops (D). ACP: anticancer peptide.

α-Helical anticancer peptides

The ACPs with α-helical structures are a major group of ACPs with short sequences and simple structures and compositions, which generally are composed of basic amino acids, such as lysine and arginine. Lysine (K) and arginine (R) are two kinds of hydrophilic amino acids with an amine group and a guanidinium group in their side chains, which contributes to the formation of peptides with net positive charges in neutral pH.47 Compared with lysine, arginine containing the guanidinium group has a higher potential to perform electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding with the anionic membrane in a high affinity.48 In contrast, lysine with ε-amino group in the side chain exhibits more hydrophobicity than arginine, and the long nonpolar alkyl side chain can insert into the hydrophobic area of the cell membrane, increasing the cytotoxicity of α-helical ACPs against cancer cells.49 Based on statistical studies, lysine is an essential component of α-helical ACPs.

Besides positive net charge, the hydrophobicity of ACPs can also influence their biological activities.50 Normally, the percentage of hydrophobic residues within ACPs can reach 30%, which makes these molecules possess a helical conformation with both polar and nonpolar faces in hydrophobic environments.51 Peptides with increased hydrophobicity on the nonpolar face would increase their helicities and self-assembling abilities, which could insert deeper into the hydrophobic area of the cell membrane, increasing the potential to form pore or channel structures in the cancer cell membrane.52 Therefore, ACPs with increased hydrophobicity would accordingly exhibit enhanced anticancer and hemolytic activities towards cancer cells.

β-Sheet anticancer peptides

The second class of ACPs shows a β-sheet structure that contains at least a pair of two β-strands, as well as 2–8 cysteine amino acids which form 1–4 pairs of intramolecular S–S bonds.53 Formation of disulfide bonds within the molecular structures of β-sheet ACPs is often essential for the stabilization of the structure and biological activities of these peptides.54 The β-sheet peptides also show amphipathic characteristics with spatially distributed polar and non-polar regions. Because of the high stability of β-sheet structures of ACPs, they will not conduct conformational transitions after binding with phospholipid membranes. Defensins are one of the well-researched and cationic ACPs which consist of 29 to 45 amino acid residues. Defensins generally are composed of three to six disulfide linkages, which create cyclic, triple-stranded β-sheet structures with spatially separated hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains.53 In addition, the pattern and position of intramolecular disulfide bonds within peptide structures can define the class of the defensin. For example, α-defensins contain disulfide linkages in the positions Cys1–Cys6, Cys2–Cys4 and Cys3–Cys5, while Cys1–Cys5, Cys2–Cys4 and Cys3–Cys6 are for β-defensins. The formation of cyclic cysteine ladder conformation plays an essential role in determining the anticancer activity of defensins by sustaining the structure and molecular stability of the cyclic backbone. The stable, cyclic structures have high surface areas and reduced conformational flexibilities, which improve the capability and selectivity to bind with cancer cells.

Anticancer peptides with extended structures

ACPs with extended structures are generally rich in arginine, proline, tryptophan, glycine and histidine, but lack typical secondary structures. The extended structures are only stabilised by hydrogen bonds and other non-covalent interactions.55 Typically, PR-39 is a linear ACP formed from proline (49%) and arginine (24%), which is isolated from porcine neutrophils. PR-39 consists of 39 amino acid residues and lacks a regular structure.56 PR-39 exerts anticancer activities on human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by inducing the expression of syndecan-1. Similar anticancer effects were also observed on hepatic leukaemia factor hepatocellular carcinoma cells when they were transfected with the PR-39 gene. Alloferon is another group of ACP derived from insects with glycine-rich domains, which can activate natural killer cells and the synthesis of interferon for antitumour treatment in mice.57

Cyclic anticancer peptides

Cyclic ACPs consist of a head-to-tail cyclization peptide backbone or disulfide linkages, which show much higher stability than that of linear molecules.58 Diffusa cytides 1–3, as three new cyclic peptides, were extracted from the leaves and roots of the white snake plant, and have an obvious preventive effect on the growth and the migration of prostate cancer cells in vitro.59 H-10 is another cyclic pentapeptide, which exhibits a concentration-dependent cytotoxic effect on mouse malignant melanoma B16 cells, without obvious cytotoxicity to human peripheral lymphocytes and rat aortic smooth muscle cells.60 Because of its intense inhibitory activity against cancer cells, cyclic ACPs account for the majority of ACPs in clinical studies.

Natural Sources of Peptides with Anticancer Activity

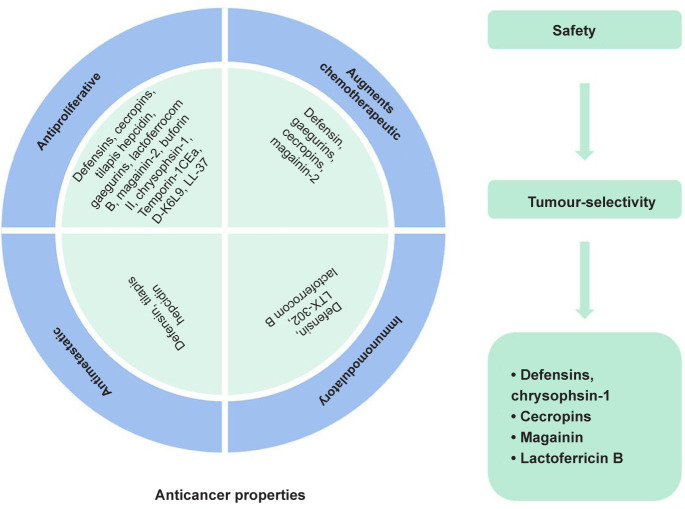

Recently, a number of natural ACPs with cationic, anionic or neutral properties have been discovered in various organisms, including marine, plant, yeast, fungi, bacteria and bovine.61 In addition, some nutrient proteins from milk and soybean can release biofunctional peptides via enzymatic degradation, and show antiproliferative effects on the growth of human cancer cells (Figure 4).62

Figure 4. Lists of bioactive peptides with potentials for anticancer therapies via varied mechanisms.

Bioactive peptide compounds from both human and terrestrial animals have been reported to have anticancer properties. For example, LL-37 is a typical antimicrobial peptide derived from human cathelicidin and shows antimicrobial activities towards both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria under much lower concentrations.63 In addition, LL-37 also exhibits the capability to induce calpain-mediated apoptosis through DNA fragmentation and mitochondrial depolarization in Jurkat cells as well as human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells.64 Defensins (α- and β-defensins) are an expressed effector agent of the innate immune system of humans with broad antimicrobial activities.65 Among them, α-defensins or named human neutrophil peptides (HNP-1, HNP-2 and HNP-3) that derive from the azurophilic granules of neutrophils could exist as dimers on cell membranes and show inhibitory activities against numerous cell lines, including human B-lymphoma cells, human oral squamous carcinoma cells, and MOT mouse teratocarcinoma cells.66 In addition, bioactive peptides (GFHI, DFHING, FHG, and GLSDGEWQ) obtained from bovine meat-derived peptides exhibit cytotoxicity.67 Among them, GFHI is most cytotoxic to the human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and could reduce the viability of the stomach adenocarcinoma cell line (AGS) in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the peptide of GLSDGEWQ considerably prohibits the proliferation and growth of AGS cells. In addition, a novel anticancer bioactive peptide (ACPB-3) extracted from goat spleens or livers, has exhibited antiproliferative activities towards the human gastric cancer cell line (BGC-823) and gastric cancer stem cells (GCSCs).68, 69

Some bioactive peptides from aquatic animal sources, such as frogs, toads, fish, ascidians, mollusks, and other organisms have also been identified with potential anticancer activities.70 For example, some amphibians, such as frogs and toads, can secrete mucus, which contains a wide range of antimicrobial peptides which show cytotoxicity towards human cancer cells.71 China has a long history of using secretions from amphibians (e.g., frogs and toads) to prepare traditional Chinese medicines for multi-purpose therapeutic applications.50 The well-studied ACPs from amphibian secretions are magainins, obtained from the skin of the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis, and exhibiting membranolytic properties.72 Magainin 2, together with its potent synthetic analogues (magainins A, B, and G), can trigger a rapid death of haematopoietic and solid tumour cells via the formation of pores on cell membranes, but no cytotoxic activity was observed on normal human or murine fibroblast cell lines.73 The hydrolytic products from dark tuna muscle have shown potential antiproliferative activities towards MCF-7 cells. Specifically, the fraction of peptides with molecular weights from 400–1400 Da from the digested products exhibits the strongest antiproliferative activity in cancer cells, because of the presence of two antiproliferative peptides, LPHVLTPEAGAT and PTAEGVYMVT.74

Milk and dairy products contain plenty of molecules that exhibit various bioactivities. Therefore, bioactive peptides prepared from milk and dairy products through enzyme-mediated digestion have been considered to be significant bioactive agents with anticancer activities. And plenty of reports have indicated the anticancer activities of bioactive peptides derived from milk protein. For instance, Roy and others discovered that bovine skim milk degraded by Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of a human leukaemia cell line.75 Lactoferrin is a glycoprotein with iron-binding properties isolated from the transferrin family and exhibits a variety of biofunctionalities, such as antibacterial, antiviral, anticancer, antiinflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities.76 In addition, lactoferrin proteins treated by pepsin under acidic conditions could generate cationic peptides with obvious cytotoxic activities against both microorganisms and cancer cells via the mechanisms of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, antiangiogenesis effects, antimetastasis effects, immune modulation and necrosis.77 Thus, milk can not only supply essential proteins as nutrients in a normal daily diet but also have potentials for the preparation of ACPs for cancer prevention and management.78 Therefore, the search for natural peptides from food sources with anticancer activities has increased in recent years. For example, the peptide of HVLSRAPR obtained from Spirulina platensis hydrolysates displayed cell selective and obvious cytotoxic activities towards HT-29 cancer cells but with little inhibitory effects on normal liver cell proliferation.79 In addition, a tripeptide of WPP extracted from blood clam muscle exhibited strong inhibitory effects against PC-3, DU-145, H-1299 and HeLa cell lines.80 Similarly, the hydrolysate of Soybean protein also contains many peptide segments such as Lunasin, RKQLQGVN,81 GLTSK, LSGNK, GEGSGA, MPACGSS and MTEEY,82 which can exert distinct antiproliferative actions on colorectal cancer HT-29 cells.

Venoms and toxins secreted by different animals are also composed of a large number of proteins or peptides, which were used as therapeutic agents in traditional medicine for centuries, and currently are explored for the discovery of novel ACPs.83 Melittin is an amphiphilic peptide with 26 amino acid residues, which is obtained from the honeybee Apis mellifera, and exhibited inhibitory effects on the growth of different cancer cells in vitro, including astrocytoma, leukaemic, lung tumour, ovarian carcinoma, squamous carcinoma, glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, osteosarcoma, prostate cancer and renal cancer cells.84 In spite of its considerable cytotoxicity to a broad spectrum of tumour cells, melittin also exhibits toxicity towards normal cells. Thus, with the purpose of achieving optimal results, the therapeutic agent of melittin could be used through accurate and specific delivery to the targeted tumour areas. Crotamine, as the first venom-derived peptide polypeptide from South American rattle snake venom, is used as a natural cell-penetrating and antimicrobial peptide with pronounced antifungal activity.85 Besides, crotamine also exhibits toxicity toward cancer cells from B16-F10 (murine melanoma cells), SK-Mel-28 (human melanoma cells), and Mia PaCa-2 (human pancreatic carcinoma cells) in a mouse model of melanoma.86 Until now, more and more natural peptides with cationic, anionic or neutral properties have been identified and collected from various organisms, whose anticancer properties are summarised and presented in Table 2.87

Table 2. Mechanism of some anticancer peptides from different origins for cancer treatment.

| No. | ACP | Cancer type | Mechanism | Molecular sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LL-37 | Human oral squamous cell, carcinoma cells | Toroidal pore mechanism | LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRI VQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES | 88 |

| 2 | α-Defensins | Human myeloid leukaemia cell line (U937) | Cytolytic activity | ACYCRIPACIAGERRYGTCI YQGRLWAFCC | 89 |

| 3 | β-Defensin-3 | HeLa, Jurkat and U937 cancer cell lines | Binding to cell membrane to cause cytolysis | GIINTLQKYYCRVRGGRCA VLSCLPKEEQIGKCSTRGRK CCRRKK | 90 |

| 4 | Bovine lactoferricin | Drug-resistant and drug-sensitive cancer cells | Cytolysis and immunogenicity | FKCRRWQWRMKKLGAP SITCVRRAF | 91 |

| 5 | Gomesin | Murine and human cancer cell lines along with melanoma and leukaemia | Carpet model for destroying the membrane | QCRRLCYKQRCVTYCRGR | 92 |

| 6 | Cecropin B1 | NSCLC cell line | Tumour growth inhibition using pore formation and apoptosis | KWKIFKKIEKVGRNIRNG IIKAGPAVAVLGEAKAL | 93 |

| 7 | Magainin 2 | Human lung cancer cells A59 and in | Formation of pores on cell membranes | GIGKFLHSAKKFGKAFVG EIMNS | 94 |

| 8 | Brevinin 2R | Breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7, and lung carcinoma A549 cell | Lysosomal death pathway and autophagy-like cell death | KLKNFAKGVAQSLLNKAS CKLSGQC | 95 |

| 9 | Bufforin IIb | Leukaemia, breast, prostate, and colon cancer | Mitochondrial apoptosis | TRSSRAGLQFPVGRVHRLL RK | 96 |

| 10 | Brevinvin | Lung cancer H460, melanoma cell, glioblastoma U251MG, colon cancer HCT116 cell lines | Penetrating into the lipidic bilayer causing cell death | FLPLAVSLAANFLPK LFCKI TKKC | 97 |

| 11 | Phylloseptin-PHa | Breast cancer cells MCF-7, breast epithelial cells MCF10A | Penetrating into the lipidic bilayer causing cell death | FLSLIPAAISAVSALANHF | 98 |

| 12 | Ranatuerin-2PLx | Prostate cancer cell PC-3 | Cell apoptosis | GIMDTVKNAAKNLAGQLL DKLKCSITAC | 99 |

| 13 | Dermaseptins | Prostate cancer cell PC-3 | Pore formation one the lipid bilayer | GLWSKIKEVGKEAAKAAAK AAGKAALGAVSEAV | 100 |

| 14 | Chrysophsin-1, -2 and -3 | Human fibrosarcoma HT-1080, histiocytic lymphoma U937, and cervical carcinoma HeLa cell lines | Disrupt the plasma membrane | FFGWLIKGAIHAGKAIHG LIHRRRH | 101 |

| 15 | D-K6L9 | Breast and prostate cancer cell lines | Reduce neovascularization | LKLLKKLLKKLLKLL | 96 |

Note: Reprinted from Bakare et al.87

Mechanism of Anticancer Peptides for Cancer Treatment

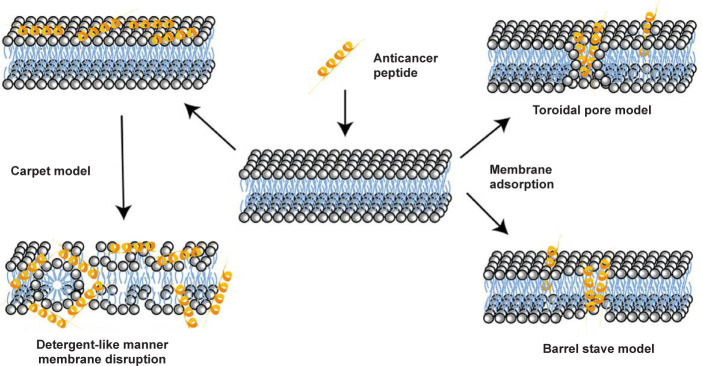

Unlike conventional anticancer chemotherapy drugs, which generally target specific biomolecules, most cationic ACPs interact with the membrane of cancer cells, resulting in cell lysis and death. Thus, ACPs provide the opportunity of developing therapeutics for cancer therapy with a new mode of action, which are complementary to conventional anticancer drugs, and to which cancer cells could not develop drug resistance. The mechanism by which ACPs perform their membrane-disruption role relies on a series of physicochemical properties, such as the sequence of peptide molecules, net positive charge, hydrophobicity, structural conformations (secondary structure, dynamics and orientation) in membranes, self-assembling, peptide concentrations, and membrane composition of cells.54 Currently, several mechanisms of membrane disruption have been proposed to describe the activity of ACPs, including the carpet model, the barrel-stave model, and the toroidal-pore wormhole model (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of different mechanisms of anticancer peptides for cell entry.

The carpet model describes the association of ACPs with positive charges with phospholipids in the outer layer of the membranes with negative charges via electrostatic interactions, which leads to the parallel alignment of ACPs to the cell membrane, covering the cell in a carpet-like manner and without embedding them into the lipid bilayers.102 But after peptide concentrations reach a threshold concentration, they change their molecular conformation by rotating themselves, inserting into the membrane, and forming micelle aggregates via hydrophobic interactions, resulting in membrane disintegration.

With regard to the barrel-stave model, ACPs first attach on the surface of cell membrane via the physical interactions of the peptides with hydrophilic segments. Then the monomer peptide undergoes a structural change and aggregates together through supramolecular self-assembling to form transmembrane channels and stave-like structures within the lipid bilayer.103 The molecular insertion of peptides generates a hydrophilic channel that expels the hydrophobic part of the bilayer. Once the formation of channel, more peptide molecules can enter and enlarge the channel’s size. Furthermore, due to the physical interactions between ACPs and cancer cells, the integrity of cell membrane is also weakened. Currently, the only discovered ACP which kills cancer cells via the barrel-stave model is alamethicin.

The toroidal pore model describes a two-stage process of interactions of ACPs with cell membranes. Firstly, the peptide is inactive at low concentrations and aligns parallel to the membrane bilayer. And then it converts to the active form at certain concentrations, perpendicularly inserts into the membrane and irreversibly destabilises the bilayers via the formation of a toroidal-like pore structure.104 The generated toroidal pore can allow for the entrance of more ACPs into the intracellular space of the cell. There are many examples of ACPs, such as cecropin A, protegrin-1 and magainin-2, that employ this mechanism to destabilise cell membranes.

Anticancer Peptides in Clinical Trials

Currently, there are a number of synthetic peptides and vaccines under clinical trials. This information could be found in the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (Table 3).17 For example, the cyclic undecapeptide of CIGB 300 (a peptide-based casein kinase 2 (CK-2) inhibitor) can inhibit CK 2 mediated phosphorylation, after fusing with the trans-acting activator of transcription (TAT) cell penetrating peptide, resulting in apoptosis of cervical and non small cell lung cancer cells.105-107 Wilms’ tumour 1 peptide vaccine exhibited high antitumour effects and safety on pediatric patients with a solid tumour, when administered with the adjuvant drug OK 432.108 In addition, Wilms’ tumour 1 pulsed dendritic cell vaccine was tested to treat patients with surgically resected pancreatic cancer under a phase I study.109 The vaccine from a modified Wilms’ tumour 1 (9-mer) peptide showed the potential to activate cytotoxic T cells, after it was administered to treat patients with gynecological cancer.110 After emulsification with Montanide ISA 51, the vaccine of LY6K 177 peptide was administered to patients with gastric cancer, and these patients showed high tolerance to the formulation in a phase I clinical trial.111

Table 3. Lists of anticancer peptides in clinical trials.

| Phase | Biological peptides | Cancer type | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early phase I | MUC-1 peptide vaccine | Breast cancer | Positive anti-MUC1 antibody responses |

| HER-2/neu peptide vaccine | Breast cancer | Specific interferon-γ and IL-5 producing T-cell responses | |

| GAA/TT-peptide vaccine and poly-ICLC | Astrocytoma, oligoastrocytoma and glioma | GAA-specific T-cell responses | |

| Phase I | Gag:267-274 peptide vaccine | Melanoma | Cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte responses |

| HPV16 E7 peptide-pulsed autologous DCs | Cervical cancer | Pulsed autologous DC immunotherapy | |

| LY6K, VEGFR1, VEGFR2 | Esophageal cancer | Immune responses including LY6K, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 specific T-cells | |

| Antiangiogenic peptide vaccine | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte responses | |

| HLA-A*0201 or HLA-A*0206-restricted URLC10 peptides | Non-small cell lung cancer | Cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte responses, antigen cascade, regulatory T-cells, cancer antigens and human leukocyte antigen levels | |

| Phase I/II | MAGE 3.A1 peptide and CpG 7909 | Malignant melanoma | Cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte responses |

| VEGFR1-1084, VEGFR2 169 | Pancreatic cancer | Cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte responses | |

| HER-2/neu peptide vaccine | Breast cancer | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-specific T-cell response | |

| Phase II | gp100:209-217(210M), HPV 16 E7:12-20 | Melanoma | T-cell immunity |

| WT1 126-134 peptide | Acute myeloid leukaemia | T-cell response | |

| G250 peptide | Metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte responses | |

| Phase III | PR1 leukaemia peptide vaccine | Leukaemia | Immune response |

| Phase IV | Degarelix | Prostatic neoplasms | Binds to GnRH receptors |

Note: Reprinted from Chiangjong et al.17 DC: dendritic cell; GnRH: gonadotropin releasing hormone; HER 2: human epidermal growth factor receptor; HPV: human papillomavirus; poly ICLC: polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid stabilized with poly-L-lysine and carboxymethylcellulose; IL-5: interleukin-5; LY6K: lymphocyte antigen 6 family member K; MUC 1: transmembrane glycoprotein mucin 1; PR1: pathogenesis-related protein 1; URLC10: a peptide vaccine; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

B cell lymphocytic leukaemia and pancreatic cancer are associated with an increased level of telomerase activity.112 The peptide vaccine of GV1001 was developed from the hTERT (EARPALLTSRLRFIPK), and tested in patients with non resectable pancreatic cancer in phase I/II trials. Studies show that it was able to induce CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, interact with professional antigen presenting cells, and then engulf dead tumour tissue or cells.113 Moreover, GV1001 also exhibited the potential to act as a candidate vaccine to treat the patients with B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, a telomerase specific leukaemic cell line.114

The integration of the ACPs with other conventional drugs, such as such as cyclodepsipeptide plitidepsin and bevacizumab, has also been tested in refractory solid tumours and evaluated in phase I trials.115 In addition, a short peptide, which can work as a luteinising hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist, was fused to cytotoxic analogs of LHRH to target cancer expressing receptors for LHRH. Based on the results of phase II clinical trial, the LHRH agonist displays anticancer activities in LHRH receptor positive cancer types (human endometrial, ovarian and prostate cancer).116 In recent years, a personalised peptide vaccine was created to work as a novel strategy for cancer treatment by boosting the immune response with specific peptides for each patient.117 For example, 19 peptide mixtures selected from 31 personalised peptide vaccines were also assessed in a phase II clinical trial in patients with metastatic breast cancer. While other peptides of gp100:209 217 (210M)/MontanideTM ISA 51/Imiquimod and E39 peptide/granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor vaccine plus E39 booster have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of high risk melanoma and ovarian cancer, respectively. In addition, the peptide of boronate bortezomib as a reversible 26S proteasome inhibitor, has been approved in clinical therapy for multiple myeloma therapy by degenerating several intracellular proteins.118-120 Till now, various cancer vaccines based on ACPs or ACPs integrated with other adjuvants or drugs, have been developed and evaluated in clinical trials for safety, side effects and specificity for targeting cancer cells by activating immune responses. More ACP examples in clinical trials are summarised and presented in Table 3.

Summary and Future Perspective

As potential therapeutic agents for cancer therapy, ACPs have numerous advantages, but also have their inherent drawbacks, including low stability, easy degradation, potential toxicity, and low bioavailability, which may severely prohibit their clinical usage.34 In recent years, different strategies have been taken to reconstruct or modify ACPs via chemical modification (e.g., cholesterol modification, phosphorylation, polyethylene glycol modification, glycosylation and palmitoylation) or replacement of natural amino acids with non-natural ones, with expected to retain their advantages while decreasing their shortcomings, thereby increasing their therapeutic efficiencies.121 Besides, with the development of material chemistry and nanotechnology, various nanomaterials with unique optical, electronic, magnetic and photo-responsive properties have been used as a selective delivery system for tumour-targeted release of ACPs.122 Furthermore, the combination of ACPs with other therapeutic modalities also holds great potentials to enhance therapeutic effects, decrease the toxicity and side effects, and prevent the development of drug resistance by cancer cells.123 Till now, a large number of ACPs with anti proliferative and apoptotic properties towards various cancer cell types, are evaluated in clinical trial or are already in the pre-clinical stage.17

Besides the significant progress in the identification of more ACPs from different natural resources, there are also developments of novel strategies for selective and targeting delivery of ACPs to cancer cells or regulating the fate of cancer cells via the process of enzyme-instructed self-assembly of peptides.124, 125 Among them, enzyme-instructed self-assembly is promising to kill cancer cells with high specificity, relying on the specific activity of enzymes overexpressed by cancer cells to induce the formation of pericellular and intracellular peptide self-assemblies, which interrupted intercellular communications, blocked multiple cellular pathways, and prevented cell survival.126, 127 Although enzyme-instructed self-assembly has exhibited numerous advantages for cancer therapy, such as high selectivity and minimal drug resistance, there is still much room for improving anticancer efficiency. Therefore, the continuous discovery of ACPs with optimised anticancer activities and development of advanced strategies with improved anticancer efficiency should offer an economically viable and therapeutically superior alternative to the current generation of chemotherapeutic drugs for cancer treatment.128, 129

Footnotes

Author contributions: Literature search and analysis, manuscript draft and figure preparation: YZ, CW, WZ and XL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support: This work was supported by the Key Laboratory of Polymeric Materials Design and Synthesis for Biomedical Function, Soochow University.

Acknowledgement: None.

Conflicts of interest statement: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Editor note: Xinming Li is an Editorial Board member of Biomaterials Translational. He was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal’s standard procedures, with peer review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and his research group.

References

- 1.Poston G. J. Global cancer surgery: the Lancet Oncology review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1559–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norouzi P., Mirmohammadi M., Houshdar Tehrani M. H. Anticancer peptides mechanisms, simple and complex. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;368:110194. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R. L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai Z., Yin Y., Shen C., Wang J., Yin X., Chen Z., Zhou Y., Zhang B. Comparative effectiveness of preoperative, postoperative and perioperative treatments for resectable gastric cancer: A network meta-analysis of the literature from the past 20 years. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu W. D., Sun G., Li J., Xu J., Wang X. Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials of cancer immunotherapy in combination with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;452:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aljabery F., Shabo I., Gimm O., Jahnson S., Olsson H. The expression profile of p14, p53 and p21 in tumour cells is associated with disease-specific survival and the outcome of postoperative chemotherapy treatment in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:530.e7–530.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajalakshmi M., Suveena S., Vijayalakshmia P., Indu S., Roy A., Ludas A. DaiCee: A database for anti-cancer compounds with targets and side effect profiles. Bioinformation. 2020;16:843–848. doi: 10.6026/97320630016843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimizu C. Side effects of anticancer treatment and the needs for translational research on toxicity: a clinician’s perspective. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2015;146:72–75. doi: 10.1254/fpj.146.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Tomás R. Multidrug resistance: retrospect and prospects in anti-cancer drug treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1859–1876. doi: 10.2174/092986706777585077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoekstra R., Verweij J., Eskens F. A. Clinical trial design for target specific anticancer agents. Invest New Drugs. 2003;21:243–250. doi: 10.1023/a:1023581731443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vulfovich M., Saba N. Molecular biological design of novel antineoplastic therapies. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;13:577–607. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L., Qu L., Lin S., Yang Q., Zhang X., Jin L., Dong H., Sun D. Biological functions and applications of antimicrobial peptides. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2022;23:226–247. doi: 10.2174/1389203723666220519155942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilchie A. L., Hoskin D. W., Power Coombs M. R. Anticancer activities of natural and synthetic peptides. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1117:131–147. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-3588-4_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soon T. N., Chia A. Y. Y., Yap W. H., Tang Y. Q. Anticancer mechanisms of bioactive peptides. Protein Pept Lett. 2020;27:823–830. doi: 10.2174/0929866527666200409102747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marqus S., Pirogova E., Piva T. J. Evaluation of the use of therapeutic peptides for cancer treatment. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24:21. doi: 10.1186/s12929-017-0328-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiangjong W., Chutipongtanate S., Hongeng S. Anticancer peptide: Physicochemical property, functional aspect and trend in clinical application (Review) Int J Oncol. 2020;57:678–696. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlieghe P., Lisowski V., Martinez J., Khrestchatisky M. Synthetic therapeutic peptides: science and market. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thundimadathil J. Cancer treatment using peptides: current therapies and future prospects. J Amino Acids. 2012;2012:967347. doi: 10.1155/2012/967347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D., He Y., Ye Y., Ma Y., Zhang P., Zhu H., Xu N., Liang S. Little antimicrobial peptides with big therapeutic roles. Protein Pept Lett. 2019;26:564–578. doi: 10.2174/1573406415666190222141905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juretić D. Designed multifunctional peptides for intracellular targets. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:1196. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11091196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basith S., Manavalan B., Shin T. H., Lee D. Y., Lee G. Evolution of machine learning algorithms in the prediction and design of anticancer peptides. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020;21:1242–1250. doi: 10.2174/1389203721666200117171403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palomo J. M. Solid-phase peptide synthesis: an overview focused on the preparation of biologically relevant peptides. RSC Adv. 2014;4:32658–32672. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai Y., Cai X., Shi W., Bi X., Su X., Pan M., Li H., Lin H., Huang W., Qian H. Pro-apoptotic cationic host defense peptides rich in lysine or arginine to reverse drug resistance by disrupting tumor cell membrane. Amino Acids. 2017;49:1601–1610. doi: 10.1007/s00726-017-2453-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro S., Aleu J., Jiménez M., Boix E., Cuchillo C. M., Nogués M. V. The cytotoxicity of eosinophil cationic protein/ribonuclease 3 on eukaryotic cell lines takes place through its aggregation on the cell membrane. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:324–337. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7499-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Midoux P., Kichler A., Boutin V., Maurizot J. C., Monsigny M. Membrane permeabilization and efficient gene transfer by a peptide containing several histidines. Bioconjug Chem. 1998;9:260–267. doi: 10.1021/bc9701611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi Y., Yamamoto K., Sato Y., Inoue S., Morinaga T., Hirano E. Combination of aspartic acid and glutamic acid inhibits tumor cell proliferation. Biomed Res. 2016;37:153–159. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.37.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oancea E., Teruel M. N., Quest A. F., Meyer T. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged cysteine-rich domains from protein kinase C as fluorescent indicators for diacylglycerol signaling in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:485–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamova O., Orlov D., Stegemann C., Czihal P., Hoffmann R., Brogden K., Kolodkin N., Sakuta G., Tossi A., Sahl H.-G., Kokryakov V., Lehrer R. I. ChBac3.4: a novel proline-rich antimicrobial peptide from goat leukocytes. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2009;15:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dennison S. R., Whittaker M., Harris F., Phoenix D. A. Anticancer alpha-helical peptides and structure/function relationships underpinning their interactions with tumour cell membranes. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2006;7:487–499. doi: 10.2174/138920306779025611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawaguchi K., Han Q., Li S., Tan Y., Igarashi K., Kiyuna T., Miyake K., Miyake M., Chmielowski B., Nelson S. D., Russell T. A., Dry S. M., Li Y., Singh A. S., Eckardt M. A., Unno M., Eilber F. C., Hoffman R. M. Targeting methionine with oral recombinant methioninase (o-rMETase) arrests a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model of BRAF-V600E mutant melanoma: implications for chronic clinical cancer therapy and prevention. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:356–361. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1405195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmaditaba M. A., Houshdar Tehrani M. H., Zarghi A., Shahosseini S., Daraei B. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel peptide-like analogues as selective COX-2 inhibitors. Iran J Pharm Res. 2018;17:87–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhunia D., Mondal P., Das G., Saha A., Sengupta P., Jana J., Mohapatra S., Chatterjee S., Ghosh S. Spatial position regulates power of tryptophan: discovery of a major-groove-specific nuclear-localizing, cell-penetrating tetrapeptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:1697–1714. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoskin D. W., Ramamoorthy A. Studies on anticancer activities of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:357–375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szlasa W., Zendran I., Zalesińska A., Tarek M., Kulbacka J. Lipid composition of the cancer cell membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2020;52:321–342. doi: 10.1007/s10863-020-09846-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schweizer F. Cationic amphiphilic peptides with cancer-selective toxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sok M., Sentjurc M., Schara M. Membrane fluidity characteristics of human lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 1999;139:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwaal R. F., Schroit A. J. Pathophysiologic implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood. 1997;89:1121–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mai J. C., Mi Z., Kim S. H., Ng B., Robbins P. D. A proapoptotic peptide for the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7709–7712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H., Kolluri S. K., Gu J., Dawson M. I., Cao X., Hobbs P. D., Lin B., Chen G., Lu J., Lin F., Xie Z., Fontana J. A., Reed J. C., Zhang X. Cytochrome c release and apoptosis induced by mitochondrial targeting of nuclear orphan receptor TR3. Science. 2000;289:1159–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouchet S., Tang R., Fava F., Legrand O., Bauvois B. The CNGRC-GG-D(KLAKLAK)2 peptide induces a caspase-independent, Ca2+-dependent death in human leukemic myeloid cells by targeting surface aminopeptidase N/CD13. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19445–19467. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y., Yu J. Research progress in structure-activity relationship of bioactive peptides. J Med Food. 2015;18:147–156. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2014.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chalamaiah M., Yu W., Wu J. Immunomodulatory and anticancer protein hydrolysates (peptides) from food proteins: a review. Food Chem. 2018;245:205–222. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma S. V. Melittin-induced hyperactivation of phospholipase A2 activity and calcium influx in ras-transformed cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:939–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quintal-Bojórquez N., Segura-Campos M. R. Bioactive peptides as therapeutic adjuvants for cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2021;73:1309–1321. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1813316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H. T., Lee C. C., Yang J. R., Lai J. Z., Chang K. Y. A large-scale structural classification of antimicrobial peptides. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:475062. doi: 10.1155/2015/475062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Libério M. S., Joanitti G. A., Fontes W., Castro M. S. Anticancer peptides and proteins: a panoramic view. Protein Pept Lett. 2013;20:380–391. doi: 10.2174/092986613805290435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rothbard J. B., Jessop T. C., Lewis R. S., Murray B. A., Wender P. A. Role of membrane potential and hydrogen bonding in the mechanism of translocation of guanidinium-rich peptides into cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9506–9507. doi: 10.1021/ja0482536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guidotti G., Brambilla L., Rossi D. Cell-penetrating peptides: from basic research to clinics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:406–424. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oelkrug C., Hartke M., Schubert A. Mode of action of anticancer peptides (ACPs) from amphibian origin. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gabernet G., Müller A. T., Hiss J. A., Schneider G. Membranolytic anticancer peptides. MedChemComm. 2016;7:2232–2245. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang Y. B., Wang X. F., Wang H. Y., Liu Y., Chen Y. Studies on mechanism of action of anticancer peptides by modulation of hydrophobicity within a defined structural framework. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:416–426. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lehrer R. I., Lichtenstein A. K., Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial and cytotoxic peptides of mammalian cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:105–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar P., Kizhakkedathu J. N., Straus S. K. Antimicrobial peptides: diversity, mechanism of action and strategies to improve the activity and biocompatibility in vivo. Biomolecules. 2018;8:4. doi: 10.3390/biom8010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veldhuizen E. J., Schneider V. A., Agustiandari H., van Dijk A., Tjeerdsma-van Bokhoven J. L., Bikker F. J., Haagsman H. P. Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activities of PR-39 derived peptides. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan Y. R., Gallo R. L. PR-39, a syndecan-inducing antimicrobial peptide, binds and affects p130(Cas) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28978–28985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bae S., Oh K., Kim H., Kim Y., Kim H. R., Hwang Y. I., Lee D. S., Kang J. S., Lee W. J. The effect of alloferon on the enhancement of NK cell cytotoxicity against cancer via the up-regulation of perforin/granzyme B secretion. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1026–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramalho S. D., Pinto M. E. F., Ferreira D., Bolzani V. S. Biologically active orbitides from the euphorbiaceae family. Planta Med. 2018;84:558–567. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu E., Wang D., Chen J., Tao X. Novel cyclotides from Hedyotis diffusa induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation and migration of prostate cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:4059–4065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang G., Liu S., Liu Y., Wang F., Ren J., Gu J., Zhou K., Shan B. A novel cyclic pentapeptide, H-10, inhibits B16 cancer cell growth and induces cell apoptosis. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:248–252. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sable R., Parajuli P., Jois S. Peptides, peptidomimetics, and polypeptides from marine sources: a wealth of natural sources for pharmaceutical applications. Mar Drugs. 2017;15:124. doi: 10.3390/md15040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chakrabarti S., Guha S., Majumder K. Food-derived bioactive peptides in human health: challenges and opportunities. Nutrients. 2018;10:1738. doi: 10.3390/nu10111738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burton M. F., Steel P. G. The chemistry and biology of LL-37. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:1572–1584. doi: 10.1039/b912533g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mader J. S., Mookherjee N., Hancock R. E., Bleackley R. C. The human host defense peptide LL-37 induces apoptosis in a calpain- and apoptosis-inducing factor-dependent manner involving Bax activity. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:689–702. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ganz T., Selsted M. E., Szklarek D., Harwig S. S., Daher K., Bainton D. F., Lehrer R. I. Defensins. Natural peptide antibiotics of human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1427–1435. doi: 10.1172/JCI112120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McKeown S. T., Lundy F. T., Nelson J., Lockhart D., Irwin C. R., Cowan C. G., Marley J. J. The cytotoxic effects of human neutrophil peptide-1 (HNP1) and lactoferrin on oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) in vitro. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jang A., Jo C., Kang K.-S., Lee M. Antimicrobial and human cancer cell cytotoxic effect of synthetic angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides. Food Chem. 2008;107:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Su L., Xu G., Shen J., Tuo Y., Zhang X., Jia S., Chen Z., Su X. Anticancer bioactive peptide suppresses human gastric cancer growth through modulation of apoptosis and the cell cycle. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu L., Yang L., An W., Su X. Anticancer bioactive peptide-3 inhibits human gastric cancer growth by suppressing gastric cancer stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:697–711. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suarez-Jimenez G. M., Burgos-Hernandez A., Ezquerra-Brauer J. M. Bioactive peptides and depsipeptides with anticancer potential: sources from marine animals. Mar Drugs. 2012;10:963–986. doi: 10.3390/md10050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Conlon J. M., Mechkarska M., Lukic M. L., Flatt P. R. Potential therapeutic applications of multifunctional host-defense peptides from frog skin as anti-cancer, anti-viral, immunomodulatory, and anti-diabetic agents. Peptides. 2014;57:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim M. K., Kang N., Ko S. J., Park J., Park E., Shin D. W., Kim S. H., Lee S. A., Lee J. I., Lee S. H., Ha E. G., Jeon S. H., Park Y. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity and mode of action of magainin 2 against drug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3041. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lehmann J., Retz M., Sidhu S. S., Suttmann H., Sell M., Paulsen F., Harder J., Unteregger G., Stöckle M. Antitumor activity of the antimicrobial peptide magainin II against bladder cancer cell lines. Eur Urol. 2006;50:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsu K. C., Li-Chan E. C. Y., Jao C. L. Antiproliferative activity of peptides prepared from enzymatic hydrolysates of tuna dark muscle on human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Food Chem. 2011;126:617–622. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roy M. K., Watanabe Y., Tamai Y. Induction of apoptosis in HL-60 cells by skimmed milk digested with a proteolytic enzyme from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biosci Bioeng. 1999;88:426–432. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(99)80221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steijns J. M., van Hooijdonk A. C. Occurrence, structure, biochemical properties and technological characteristics of lactoferrin. Br J Nutr. 2000;84(Suppl 1):S11–17. doi: 10.1017/s0007114500002191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mader J. S., Salsman J., Conrad D. M., Hoskin D. W. Bovine lactoferricin selectively induces apoptosis in human leukemia and carcinoma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:612–624. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yin C. M., Wong J. H., Xia J., Ng T. B. Studies on anticancer activities of lactoferrin and lactoferricin. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2013;14:492–503. doi: 10.2174/13892037113149990066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang Z., Zhang X. Isolation and identification of anti-proliferative peptides from Spirulina platensis using three-step hydrolysis. J Sci Food Agric. 2017;97:918–922. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chi C.-F., Hu F.-Y., Wang B., Li T., Ding G.-F. Antioxidant and anticancer peptides from the protein hydrolysate of blood clam (Tegillarca granosa) muscle. J Funct Foods. 2015;15:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fernández-Tomé S., Sanchón J., Recio I., Hernández-Ledesma B. Transepithelial transport of lunasin and derived peptides: Inhibitory effects on the gastrointestinal cancer cells viability. J Food Compost Anal. 2018;68:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luna Vital D. A., González de Mejía E., Dia V. P., Loarca-Piña G. Peptides in common bean fractions inhibit human colorectal cancer cells. Food Chem. 2014;157:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soares A. M., Zuliani J. P. Toxins of animal venoms and inhibitors: molecular and biotechnological tools useful to human and animal health. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19:1868–1871. doi: 10.2174/156802661921191024114842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Havas L. J. Effect of bee venom on colchicine-induced tumours. Nature. 1950;166:567–568. doi: 10.1038/166567a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kerkis I., Hayashi M. A., Prieto da Silva A. R., Pereira A., De Sá Júnior P. L., Zaharenko A. J., Rádis-Baptista G., Kerkis A., Yamane T. State of the art in the studies on crotamine, a cell penetrating peptide from South American rattlesnake. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:675985. doi: 10.1155/2014/675985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pereira A., Kerkis A., Hayashi M. A., Pereira A. S., Silva F. S., Oliveira E. B., Prieto da Silva A. R., Yamane T., Rádis-Baptista G., Kerkis I. Crotamine toxicity and efficacy in mouse models of melanoma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:1189–1200. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.602064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bakare O. O., Gokul A., Wu R., Niekerk L. A., Klein A., Keyster M. Biomedical relevance of novel anticancer peptides in the sensitive treatment of cancer. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1120. doi: 10.3390/biom11081120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aghazadeh H., Memariani H., Ranjbar R., Pooshang Bagheri K. The activity and action mechanism of novel short selective LL-37-derived anticancer peptides against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2019;93:75–83. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fruitwala S., El-Naccache D. W., Chang T. L. Multifaceted immune functions of human defensins and underlying mechanisms. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;88:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu S., Zhou L., Li J., Suresh A., Verma C., Foo Y. H., Yap E. P., Tan D. T., Beuerman R. W. Linear analogues of human beta-defensin 3: concepts for design of antimicrobial peptides with reduced cytotoxicity to mammalian cells. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:964–973. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zweytick D. LTX-315 - a promising novel antitumor peptide and immunotherapeutic agent. Cell Stress. 2019;3:328–329. doi: 10.15698/cst2019.11.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jeyamogan S., Khan N. A., Sagathevan K., Siddiqui R. Sera/organ lysates of selected animals living in polluted environments exhibit cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2019;19:2251–2268. doi: 10.2174/1871520619666191011161314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brady D., Grapputo A., Romoli O., Sandrelli F. Insect cecropins, antimicrobial peptides with potential therapeutic applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5862. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pinto I. B., dos Santos Machado L., Meneguetti B. T., Nogueira M. L., Espínola Carvalho C. M., Roel A. R., Franco O. L. Utilization of antimicrobial peptides, analogues and mimics in creating antimicrobial surfaces and bio-materials. Biochem Eng J. 2019;150:107237. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li B., Lyu P., Xie S., Qin H., Pu W., Xu H., Chen T., Shaw C., Ge L., Kwok H. F. LFB: A Novel Antimicrobial Brevinin-Like Peptide from the Skin Secretion of the Fujian Large Headed Frog, Limnonectes fujianensi. Biomolecules. 2019;9:242. doi: 10.3390/biom9060242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zahedifard F., Lee H., No J. H., Salimi M., Seyed N., Asoodeh A., Rafati S. Anti-leishmanial activity of Brevinin 2R and its Lauric acid conjugate type against L. major: In vitro mechanism of actions and in vivo treatment potentials. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu Y., Tavana O., Gu W. p53 modifications: exquisite decorations of the powerful guardian. J Mol Cell Biol. 2019;11:564–577. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjz060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen X., Zhang L., Ma C., Zhang Y., Xi X., Wang L., Zhou M., Burrows J. F., Chen T. A novel antimicrobial peptide, Ranatuerin-2PLx, showing therapeutic potential in inhibiting proliferation of cancer cells. Biosci Rep. 2018;38:BSR20180710. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tornesello A. L., Borrelli A., Buonaguro L., Buonaguro F. M., Tornesello M. L. Antimicrobial peptides as anticancer agents: functional properties and biological activities. Molecules. 2020;25:2850. doi: 10.3390/molecules25122850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tripathi A. K., Kumari T., Harioudh M. K., Yadav P. K., Kathuria M., Shukla P. K., Mitra K., Ghosh J. K. Identification of GXXXXG motif in Chrysophsin-1 and its implication in the design of analogs with cell-selective antimicrobial and anti-endotoxin activities. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3384. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03576-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hansen I., Isaksson J., Poth A. G., Hansen K., Andersen A. J. C., Richard C. S. M., Blencke H. M., Stensvåg K., Craik D. J., Haug T. Isolation and characterization of antimicrobial peptides with unusual disulfide connectivity from the colonial ascidian synoicum turgens. Mar Drugs. 2020;18:51. doi: 10.3390/md18010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oren Z., Shai Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 1998;47:451–463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<451::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shai Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by alpha-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Matsuzaki K., Murase O., Fujii N., Miyajima K. An antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, induced rapid flip-flop of phospholipids coupled with pore formation and peptide translocation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11361–11368. doi: 10.1021/bi960016v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Garay H., Espinosa L. A., Perera Y., Sánchez A., Diago D., Perea S. E., Besada V., Reyes O., González L. J. Characterization of low-abundance species in the active pharmaceutical ingredient of CIGB-300: A clinical-grade anticancer synthetic peptide. J Pept Sci. 2018;24:e3081. doi: 10.1002/psc.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Perea S. E., Reyes O., Baladron I., Perera Y., Farina H., Gil J., Rodriguez A., Bacardi D., Marcelo J. L., Cosme K., Cruz M., Valenzuela C., López-Saura P. A., Puchades Y., Serrano J. M., Mendoza O., Castellanos L., Sanchez A., Betancourt L., Besada V., Silva R., López E., Falcón V., Hernández I., Solares M., Santana A., Díaz A., Ramos T., López C., Ariosa J., González L. J., Garay H., Gómez D., Gómez R., Alonso D. F., Sigman H., Herrera L., Acevedo B. CIGB-300, a novel proapoptotic peptide that impairs the CK2 phosphorylation and exhibits anticancer properties both in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;316:163–167. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rodríguez-Ulloa A., Ramos Y., Gil J., Perera Y., Castellanos-Serra L., García Y., Betancourt L., Besada V., González L. J., Fernández-de-Cossio J., Sanchez A., Serrano J. M., Farina H., Alonso D. F., Acevedo B. E., Padrón G., Musacchio A., Perea S. E. Proteomic profile regulated by the anticancer peptide CIGB-300 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:5473–5483. doi: 10.1021/pr100728v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hirabayashi K., Yanagisawa R., Saito S., Higuchi Y., Koya T., Sano K., Koido S., Okamoto M., Sugiyama H., Nakazawa Y., Shimodaira S. Feasibility and immune response of WT1 peptide vaccination in combination with OK-432 for paediatric solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:2227–2234. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yanagisawa R., Koizumi T., Koya T., Sano K., Koido S., Nagai K., Kobayashi M., Okamoto M., Sugiyama H., Shimodaira S. WT1-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine combined with chemotherapy for resected pancreatic cancer in a phase I study. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:2217–2225. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ohno S., Takano F., Ohta Y., Kyo S., Myojo S., Dohi S., Sugiyama H., Ohta T., Inoue M. Frequency of myeloid dendritic cells can predict the efficacy of Wilms’ tumor 1 peptide vaccination. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2447–2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ishikawa H., Imano M., Shiraishi O., Yasuda A., Peng Y. F., Shinkai M., Yasuda T., Imamoto H., Shiozaki H. Phase I clinical trial of vaccination with LY6K-derived peptide in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vasef M. A., Ross J. S., Cohen M. B. Telomerase activity in human solid tumors. Diagnostic utility and clinical applications. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112:S68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bernhardt S. L., Gjertsen M. K., Trachsel S., Møller M., Eriksen J. A., Meo M., Buanes T., Gaudernack G. Telomerase peptide vaccination of patients with non-resectable pancreatic cancer: A dose escalating phase I/II study. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1474–1482. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kokhaei P., Palma M., Hansson L., Osterborg A., Mellstedt H., Choudhury A. Telomerase (hTERT 611-626) serves as a tumor antigen in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and generates spontaneously antileukemic, cytotoxic T cells. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Aspeslagh S., Awada A. A. S. M. P., Aftimos P., Bahleda R., Varga A., Soria J. C. Phase I dose-escalation study of plitidepsin in combination with bevacizumab in patients with refractory solid tumors. Anticancer Drugs. 2016;27:1021–1027. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Engel J. B., Tinneberg H. R., Rick F. G., Berkes E., Schally A. V. Targeting of peptide cytotoxins to LHRH receptors for treatment of cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:488–494. doi: 10.2174/138945011705160303154717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Noguchi M., Matsumoto K., Uemura H., Arai G., Eto M., Naito S., Ohyama C., Nasu Y., Tanaka M., Moriya F., Suekane S., Matsueda S., Komatsu N., Sasada T., Yamada A., Kakuma T., Itoh K. An open-label, randomized phase II trial of personalized peptide vaccination in patients with bladder cancer that progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:54–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Brown T. A., Byrd K., Vreeland T. J., Clifton G. T., Jackson D. O., Hale D. F., Herbert G. S., Myers J. W., Greene J. M., Berry J. S., Martin J., Elkas J. C., Conrads T. P., Darcy K. M., Hamilton C. A., Maxwel G. L., Peoples G. E. Final analysis of a phase I/IIa trial of the folate-binding protein-derived E39 peptide vaccine to prevent recurrence in ovarian and endometrial cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2019;8:4678–4687. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schwartzentruber D. J., Lawson D. H., Richards J. M., Conry R. M., Miller D. M., Treisman J., Gailani F., Riley L., Conlon K., Pockaj B., Kendra K. L., White R. L., Gonzalez R., Kuzel T. M., Curti B., Leming P. D., Whitman E. D., Balkissoon J., Reintgen D. S., Kaufman H., Marincola F. M., Merino M. J., Rosenberg S. A., Choyke P., Vena D., Hwu P. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2119–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mikecin A. M., Walker L. R., Kuna M., Raucher D. Thermally targeted p21 peptide enhances bortezomib cytotoxicity in androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:189–199. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xie M., Liu D., Yang Y. Anti-cancer peptides: classification, mechanism of action, reconstruction and modification. Open Biol. 2020;10:200004. doi: 10.1098/rsob.200004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hu X., Liu S. Recent advances towards the fabrication and biomedical applications of responsive polymeric assemblies and nanoparticle hybrid superstructures. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:3904–3922. doi: 10.1039/c4dt03609c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hwang J. S., Kim S. G., Shin T. H., Jang Y. E., Kwon D. H., Lee G. Development of anticancer peptides using artificial intelligence and combinational therapy for cancer therapeutics. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:997. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14050997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Regberg J., Srimanee A., Langel U. Applications of cell-penetrating peptides for tumor targeting and future cancer therapies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2012;5:991–1007. doi: 10.3390/ph5090991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chatzisideri T., Leonidis G., Sarli V. Cancer-targeted delivery systems based on peptides. Future Med Chem. 2018;10:2201–2226. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2018-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kim B. J., Xu B. Enzyme-instructed self-assembly for cancer therapy and imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2020;31:492–500. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shi J., Xu B. Nanoscale assemblies of small molecules control the fate of cells. Nano Today. 2015;10:615–630. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu X., Wu F., Ji Y., Yin L. Recent advances in anti-cancer protein/peptide delivery. Bioconjug Chem. 2019;30:305–324. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Conibear A. C., Schmid A., Kamalov M., Becker C. F. W., Bello C. Recent advances in peptide-based approaches for cancer treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27:1174–1205. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666171123204851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]