Abstract

Background:

The cholinesterase inhibitor therapeutics (CI) approved for use in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are palliative for a limited time.

Objective:

To examine the outcome of AD patients with add-on therapy of the omega-3 fatty acid drink Smartfish.

Methods:

We performed a prospective study using Mini-Mental State Examination, amyloid-β (Aβ) phagocytosis blood assay, and RNA-seq of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in 28 neurodegenerative patients who had failed their therapies, including 8 subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), 8 mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 2 AD dementia, 1 frontotemporal dementia (FTD), 2 vascular cognitive impairment, and 3 dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) patients.

Results:

MCI, FTD, and DLB patients patients volunteered for the addition of a ω-3 fatty acid drink Smartfish protected by anti-oxidants to failing CI therapy. On this therapy, all MCI patients improved in the first year energy transcripts, Aβ phagocytosis, cognition, and activities of daily living; in the long term, they remained in MCI status two to 4.5 years. All FTD and DLB patients rapidly progressed to dementia. On in vivo or in vitro ω-3 treatments, peripheral blood mononuclear cells of MCI patients upregulated energy enzymes for glycolysis and citric acid cycle, as well as the anti-inflammatory circadian genes CLOCK and ARNTL2.

Conclusion:

Add-on ω-3 therapy to CI may delay dementia in certain patients who had failed single CI therapy.

Keywords: Amyloid-beta, bioenergy, cell signaling, cholinesterase inhibitor, glycolysis, ω-3 fatty acids, phagocytosis, tricarboxylic cycle

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has no currently approved disease-modifying therapy. In mild-to-moderate AD, the cholinesterase inhibitor (CI) drugs, such as donepezil, and the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine, show initially approximately 1.5-point Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) gain, which falls below baseline at 6 to 9 months and remains a small advantage for a year compared to a placebo [1]. Cochrane review found that AD patients on donepezil experience small benefits for 12–24 weeks [2]. Anti-amyloid antibodies have recently failed with an exception of aducanumab, which has limited brain penetration and risk of vasogenic edema. Tramiprostate inhibits soluble amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers, which are considered principal toxic species, but clinical effects were shown only in APOE ε4/ε4 homozygotes [3]. Long-term studies of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients beyond 6 to 12 months of single, combination, and add-on therapies are lacking [4].

Popular and well-tolerated omega-3 fatty acid (ω-3) supplementation is a potential addition to long-term preventive therapy of MCI patients. We find that ω-3 support innate immunity against Aβ [5] based on their pro-phagocytic action and reduce inflammation by their anti-inflammatory [6] and anti-endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress properties [7]. ω-3 is the only natural product with favorable clinical effects in a controlled clinical trial, in which ω-3 supplementation (430 mg docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and 150 mg eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)) slowed cognitive decline in early stage MCI patients [8]. A trial of the algal DHA, however, showed no effect [9]. The ω-3 supplement-related factors (fish-derived emulsion versus algal DHA, and inclusion of anti-oxidants) and patient-related factors (cognitive reserve, disease stage, APOE genotype, compliance, and comorbidities) may explain the discrepancy [10, 11].

ω-3 has multiple mechanisms relevant to neurode-generative diseases, including the enhancement of oxidative and glycolytic metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis in human muscle cells [12], and structural effects in the white matter of the fornix [13]. ω-3 supplementation increases ω-3 incorporation into the mitochondria and reactive oxygen species (ROS) emission without oxidative damage [14]. Mitochondrial ROS signaling promotes homeostasis and longevity in model systems [15, 16]. In MCI patients, curcuminoids increase macrophage phagocytosis of Aβ through effects on the glycosylation enzyme MGAT-III [17]. ω-3 and resveratrol increase Aβ macrophage phagocytosis by enhancing unfolded protein response to ER stress [18]. Thus, ω-3 and other molecules with transcriptional effects in the immune system on homeostasis, energy and circadian genes, and structural effects have beneficial mechanisms for MCI patients.

We performed a prospective observational study of neurodegenerative patients for up to 5 years and examined the effects of ω-3 supplementation added to CI therapy on cognition, immunity, and transcription of energy and circadian genes. AD is associated with reduced nuclear gene expression encoding subunits of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in the neurons of AD-affected regions [19] and disturbances of circadian rhythm [20]. We investigated transcription of energy and circadian genes and immune function of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of neurodegenerative patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

We enrolled 28 community patients (>60 years of age, males and female, a variety of ethnicities, and MMSE score of 16 or higher) who had failed CI or other therapies and desired participation in a research study and supplementation by ω-3.

The usual complaints included failing memory, impaired activities of daily living, and loss of driving ability and orientation. On the follow-up, we diagnosed 8 patients as subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), 8 as MCI, 6 as AD, one as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), 2 as vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), and 3 as dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). We followed the patients by MMSE, Aβ phagocytosis test using PBMC, transcriptional testing of PBMC, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) scan. We obtained informed Consent from all participants. This work was performed in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) serves all ethnicities and genders. UCLA Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study and the testing of blood samples.

Diagnostic evaluation

We diagnosed eight subjects as SCI (MMSE 27–30) according to subjective complaints and subtle cognitive defects [21]; eight subjects as MCI (MMSE > 19 and <27) using the Petersen criteria [22] and a positive FDG PET scan in five patients; one subject as FTD according to positron emission tomography (PET-CT); six as AD dementia (MMSE <19); two subjects as VCI according to the history of recurring minor strokes and FDG scan; and three subjects as DLB according to neuropsychiatric symptoms before onset of the movement disorder and FDG-scan. All MCI and AD patients, one FTD patient, two DLB patients, and one SCI patient had been receiving CI therapy prescribed by each patient’s neurologist prior to ω-3 supplementation and continued CI (except patient #14) together with ω-3 supplementation.

Nutritional supplementation

The participants took, under caregiver supervision, daily supplementation with 100 mL of the ω-3 drink Smartfish (SMFRES) [18], which was provided directly to each patient at his/her request by Smartfish AS, Oslo, Norway. The drink contained in a 200 mL emulsion 1000 mg DHA, 1000 mg EPA, and other fish-derived lipids (see below), botanical antioxidants (pomegranate and choke-berry), 10 μg vitamin D3, and 150 mg resveratrol. Lipidomic analysis of SMF showed lipids from nine classes including ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids, cholesterol esters, ceramides, lysophophatidylcholine, lysophophatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, sphingomyelin, and triacylglycerols.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells and macrophage cultures

We isolated PBMC from the blood collected from patients between 9 AM and 12 PM using the Ficoll-Hypaque gradient method, and incubated 50,000 PBMC in each well of the 8-well culture slide (Becton Dickinson Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA, USA) in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) with 10% autologous serum. CD68-positive macrophages with typical appearance differentiated in 14–21 days [18]. We isolated RNA from PBMC or macrophages noon to 3 PM. For in vitro testing, we used SMFRES diluted in fetal calf serum, sonicated, and then diluted in IMDM to the final concentration of 27 μg/mL DHA or 3x higher.

Aβ phagocytosis blood test and ω-3 effects on phagocytosis

We suspended PBMC in IMDM medium (ThermoFisher Co.) with 10% autologous serum and placed 300,000 PBMC in tubes #1, 2, 3, and 4. We added beta-amyloid (1–42) Hi-Lyte fluor 488 (Anaspec, San Jose, CA) to tubes #2 and #3. After incubation for 18 h, we washed the cells with FACS buffer (2 μg bovine serum albumin/mL) by centrifugation and resuspended in 100 μL of FACS buffer. We stained tubes #3 and #4 30 min at 4°C with anti-CD14-PE (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). We examined the cells in the Attune Nxt flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) within CD14-positive cells by FlowJo vX software (Ashland, OR, USA). We tested ω-3 in the SMF drink as well as in other preparations of ω-3 (omegaFF 100–1, Vesteraalens, Norway; DHA and EPA, Cayman Chemical).

RNA sequencing analysis

We stimulated PBMC (2 million) with SMFRES (SMFRES emulsion diluted to DHA 27 μg/ml) or a placebo 18 h, extracted RNA using RNA extraction kit (Zymo Research), and prepared the libraries using kappa mRNA HyperPrep kit on a custom Janus G3 Liquid Handler (Perkin-Elmer). We sequenced the libraries using Illumina HiSeq 3000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to obtain 50-bp reads. We processed the RNA-Seq data to remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads and aligned them to the human genome GCHr38 using STAR (v2.6+) [23]. We calculated data from HTSeq [24], normalized and measured differential expression using DESeq2 [25].

RESULTS

Cognitive status of SCI and MCI, but not AD, VCI, and DLB, patients is stabilized on ω-3 supplementation and dementia is delayed beyond historical trials of CI

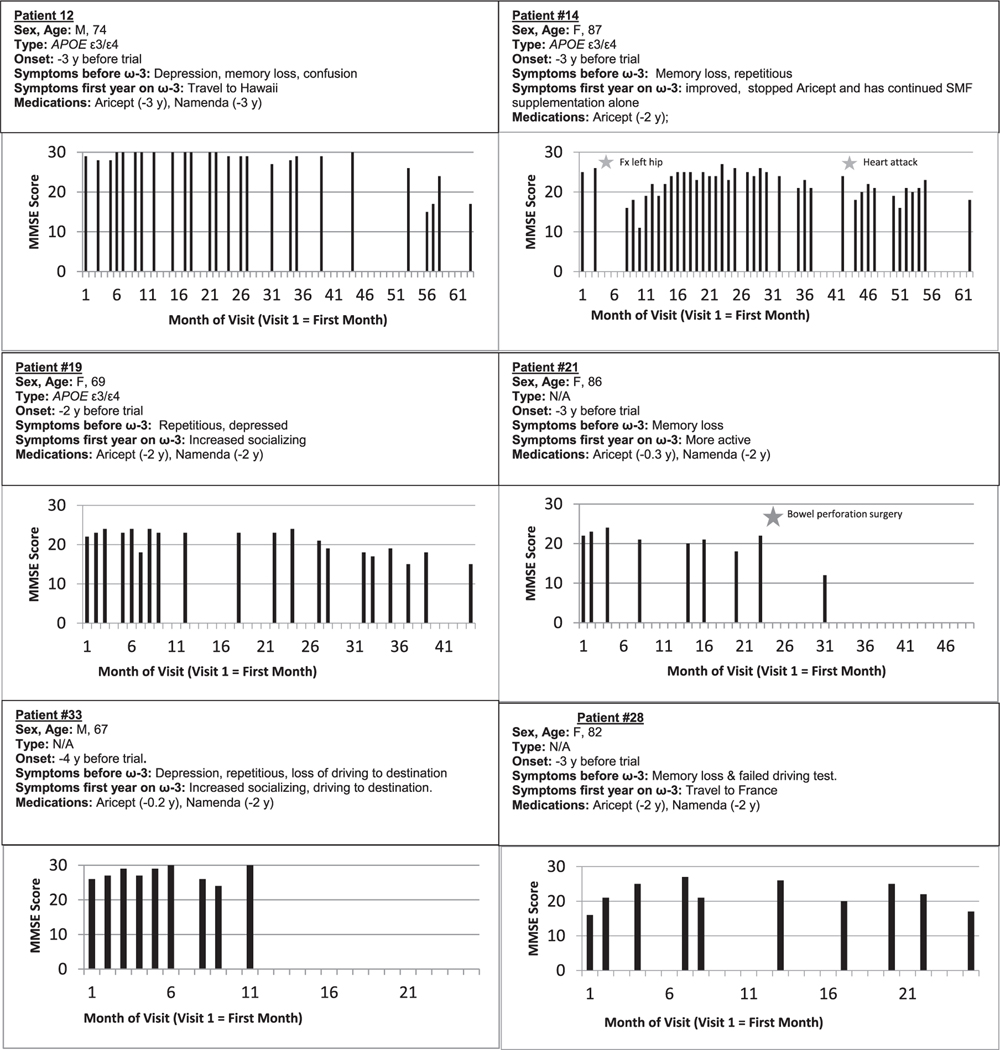

We evaluated cognition by MMSE testing at 1- to 3-monthly visits. On ω-3 add-on to CI therapy, all SCI patients had stable cognitive status for 4 to 23 months. On this therapy, all eight MCI patients improved in a short term with three patients improving by 4, 11, and 4 MMSE points in the first year (Fig. 1). Five patients maintained the MCI status for at least 8 to 24 months and continued in the study. Three MCI patients maintained the MCI status for 26 to 54 months before progressing to dementia stage. All other patients had a rapid decline: AD patients 0.35 points per month, VCI patients 0.28 points per month, and DLB patients 0.94 points per month. The MMSE change of SCI and MCI patients versus AD, VCI, and DLB patients was significantly different (p = 0.024) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cognitive status of MCI patients on cholinesterase and add-on ω-3 therapies over the whole study. Note protection (months) of initial MMSE status in MCI patients: 43 (pt. #12), 41 (pt. #14), 23 (pt. #19), 20 (pt #28), and 11 (pt #33).

Table 1.

Changes in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of SCI, MCI, VCI, and DLB patients on supplementation with the ω-3 drink Smartfish

| Diagnosis Group | Patient # | Age, Sex At onset | Genotype | CI Therapy before ω-3 (y) | ω-3 supplement 1st - last (months) | MMSE 1st visit | MMSE last visit | MMSE change per month (prior to AD onset) | Progression to AD dementia (months after onset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCI | 4 | 77, M | ε3/ε3 | none | 9 | 30 | 30 | 0 | none |

| SCI | 7 | 78, F | ND | none | 7 | 29 | 30 | +0.14 | none |

| SCI | 10 | 61, F | ε3/ε3 | none | 6 | 28 | 30 | +0.33 | none |

| SCI | 11 | 63, F | ε3/ε3 | none | 4 | 28 | 29 | +0.25 | none |

| SCI | 18 | 72, F | ε3/ε4 | 4 | 23 | 30 | 30 | 0 | none |

| SCI | 24 | 69, M | ND | none | 6 | 30 | 30 | 0 | none |

| SCI | 26 | 80, M | ε3/ε3 | none | 15 | 28 | 30 | +0.13 | none |

| SCI | 15 | 66, M | ε3/ε4 | none | 13 | 30 | 30 | 0 | |

| SCI | n = 8, Mean ± SE | 10.4 ± 2.2 | 29.1 ± 0.4 | 29.9 ± 0.1 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | none | |||

| MCI | 3 | 83, M | ε3/ε4 | 1 | 17 | 23 | 21 | −0.12 | none |

| MCI | 8 | 72, M | ND | 0 | 8 | 26 | 30 | +0.5 | none |

| MCI | 10 | 61, F | ND | 1 | 18 | 26 | 30 | +0.22 | none |

| MCI | 12 | 74, M | ε3/ε4 | 3 | 62 | 29 | 25 | −0.06 | 52 |

| MCI | 14 | 87, F | ε3/ε4 | 2 | 61 | 25 | 23 | −0.04 | 54 |

| MCI | 19 | 69, F | ε3/ε4 | 2 | 43 | 22 | 20 | −0.04 | 26 |

| MCI | 28 | 82, F | ND | 2 | 24 | 16 | 23 | +0.29 | none |

| MCI | 33 | 67, M | ND | 2 | 10 | 26 | 30 | +0.4 | none |

| MCI | n = 8, Mean ± SE | 30.4 ± 7.8 | 24.1 ± 1.4 | 25.8 ± 1.5 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 44 | |||

| AD | 23 | 61, M | ND | 1 | 8 | 13 | 11 | −0.25 | |

| AD | 1 | 81, F | ND | 1 | 8 | 17 | 12 | −0.63 | |

| AD | 12 | 58, F | ND | 1 | 25 | 8 | 3 | −0.20 | |

| AD | 9 | 88, F | ND | 5 | 6 | 16 | 11 | −0.83 | |

| AD | 1A | 68, M | ND | 5 | 12 | 18 | 10 | −0.67 | |

| AD | n = 5, Mean ± SE | 11.8 ± 3.4 | 14.4 ± 1.8 | 9.4 ± 1.6 | −0.52 ± 0.12 | N/A | |||

| FTD | 21 | 86, M | ND | 2 | 30 | 22 | 11 | −0.36 | 22 |

| FTD | n = 1, Mean | 30 | 22 | 11 | −0.36 | 22 | |||

| VCI/MCI | 2 | 79, M | ε3/ε4 | none | 51 | 24 | 28 | +0.07 | none |

| VCI | 25 | 96, M | ε3/ε4 | none | 8 | 30 | 25 | −0.63 | none |

| VCI | n = 2, Mean ± SE | 25.5 ± 17.5 | 27.0 ± 3.0 | 26.5 ± 1.5 | −0.28 ± 0.35 | N/A | |||

| DLB | 9 | 74, M | ε3/ε3 | none | 35 | 26 | 3 | −0.66 | 21 |

| DLB | 20 | 63, F | ε3/ε4 | 1 | 14 | 17 | 10 | −0.5 | 5 |

| DLB | 32 | 75, M | ND | 1 | 3 | 25 | 20 | −1.67 | none |

| DLB | n = 3, Mean ± SE | 17.3 ± 9.4 | 22.7 ± 2.8 | 11.0 ± 4.9 | −0.94 ± 0.36 | 13 | |||

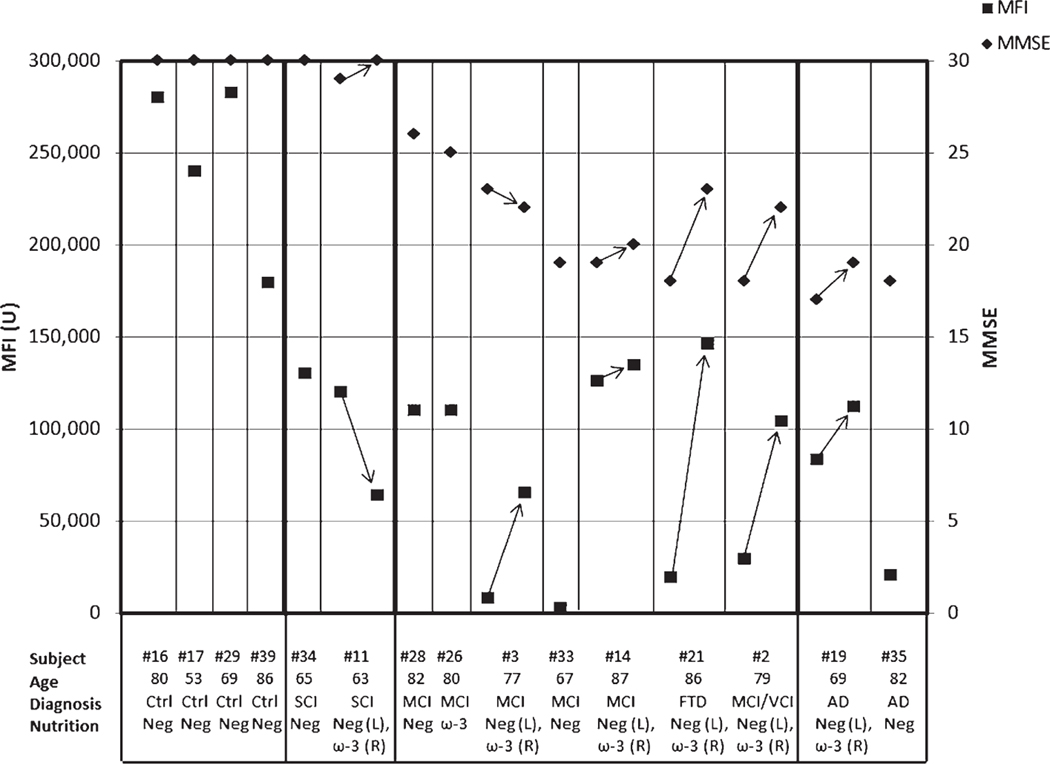

Improvement of the Aβ phagocytosis blood test on ω-3 supplementation

We evaluated the progressive stages of AD immunopathology by the Aβ phagocytosis blood test. We improved the sensitivity of the phagocytosis test with brighter fluorescent Aβ for detection of cognitive changes compared to the previous test. Our 2019 test is 250-times more sensitive and has improved correlation with cognition (Pearson’s correlation of MMSE with MFI r = 0.66) in comparison to the 2009 phagocytosis test (Pearson’s correlation r = 0.32) [26]. The test results separate the stages from normal to AD: > 150,000 MFI units in normal age-matched controls; 100,000–150,000 MFI units in SCI patients; c) < 50,000 MFI units in MCI and AD patients at the first, non-supplemented visit, but >100,000 MFI units after supplementation. The AD patient #21 showed strong improvement from MMSE 18 and phagocytosis of 19,705 MFI units to MMSE 22 and phagocytosis of 145, 170 MFI units (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Amyloid-β phagocytosis blood test (MFI units) in control subjects (#16, #17,#29, #39), SCI (#34, #11), MCI (#28, #26, #3, #33, #14, #21, #2), and AD (#19 and #35) patients before (neg) and 2 to 3 months on ω-3 therapy (ω-3). Minimental state examination score (MMSE) is shown for each subject.

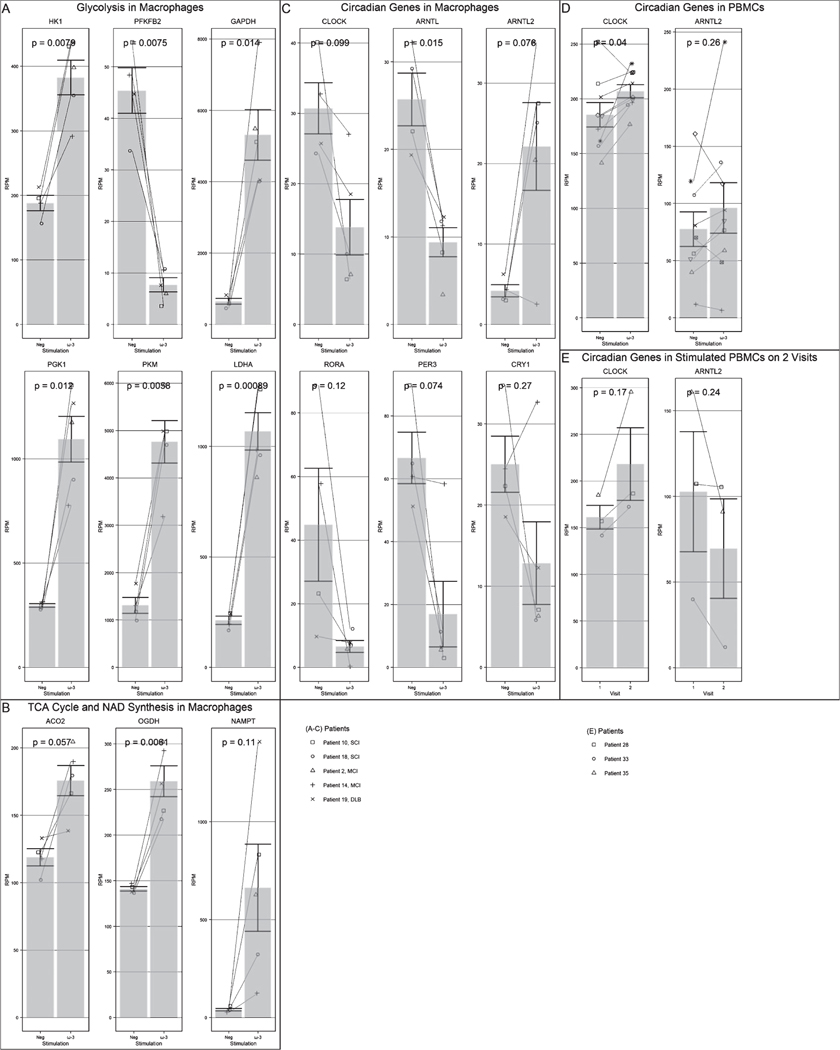

Upregulation of energy and circadian gene transcripts by ω-3 in vitro and in vivo

We evaluated the effects of SMFRES on energy and circadian cycle genes in macrophages and PBMC of AD/MCI patients. We compared the results trans-sectionally on the same visit (placebo versus ω-3 treatment in vitro) and longitudinally on two successive visits (ω-3 on visit 1 and visit 2) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of ω-3 treatment (in macrophages (Mφ) or PBMC, as stated) on: A) glycolysis in Mφ (p < 0.02), B) TCA cycle in Mφ (p < 0.003), C) NAMPT in Mφ (p < 0.2), D) circadian genes in Mφ (p < 0.003), E) CLOCK (PBMC, two visits) (N.S.), F) CLOCK (PBMC, same visit neg versus ω-3, N.S.)

Trans-sectional analysis showed upregulation of energy genes and the circadian gene ARNTL2 by ω-3 in macrophages and PBMC. The upregulated nuclear energy genes included enzymes in glycolysis (hexokinase (HK) and glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase (GAPDH)); tricarboxylic cycle (alpha-ketoglutarate (OGDH); and the NAD metabolism (nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT). Longitudinal analysis on two visits suggested upregulation by ω-3 of the circadian regulator CLOCK (N.S.) in PBMC (Fig. 3).

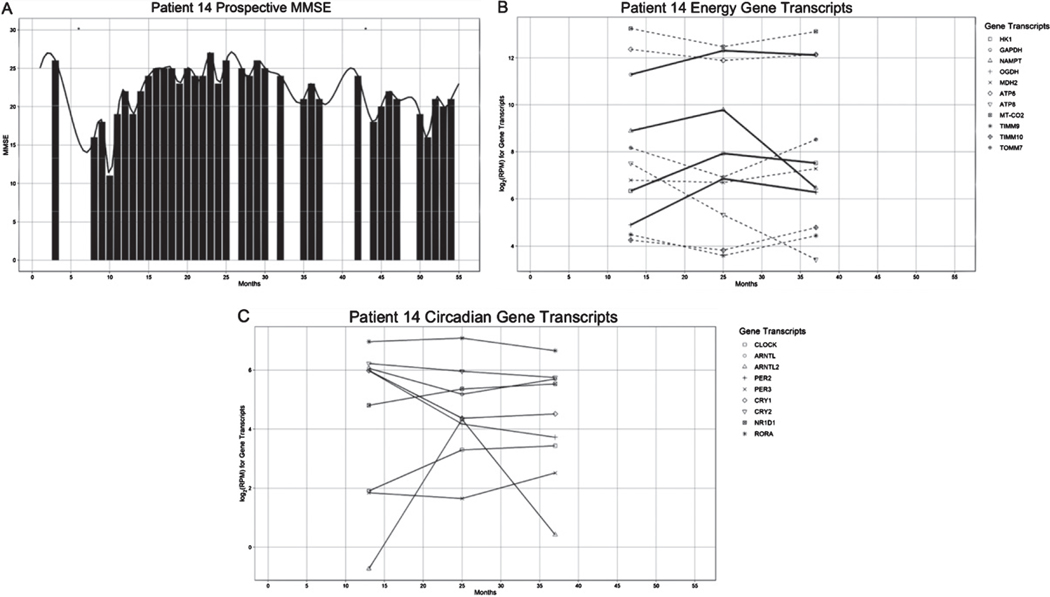

Changes in cognition parallel changes in transcription of energy and circadian genes

We followed the MCI patient #14 for 5.3 years. Her cognition declined from the initial MMSE 25 to MMSE 11 during a hospitalization for a hip fracture without ω-3 supplementation. On resumption of ω-3 supplementation after discharge (Fig. 4A), her cognition increased in parallel with nuclear energy gene transcripts for 26 months but slowly decreased afterwards in parallel with energy transcripts. Mitochondrion-coded gene transcripts (ATP6, ATP8, MTCO2, TOMM7, TIMM9, TIMM10) had an opposite trend to energy enzymes (Fig. 4B). The circadian genes CLOCK and ARNTL2 increased in the recovery phase but had opposite or flat trend while the patient was cognitively declining. In the recovery phase, proinflammatory PER 2 and 3, anti-inflammatory CRY 1 and 2, and ROR alpha had divergent trends (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 4.

Relation of cognitive progression (MMSE score) and transcription of energy (HK1, GAPDH, OGDH, and NAMPT) and circadian genes (CLOCK, ARNTL2) in patient #14 followed for 5 years.

Imaging results by FDG glucose scan

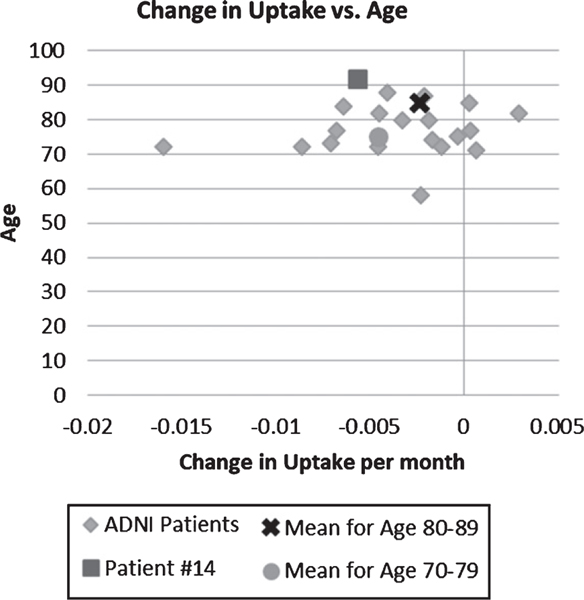

The MCI patient #14, current age 93, had her initial FDG scan in July 2016 followed by another scan in December 2019, which showed a decrease of FDG uptake in the right parietotemporal cortex −0.0057 per month. In comparison, the patients in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database with MMSE score 20–25 had an average change in uptake per month in the right temporal cortex of −0.0036. In the database, the average age of the patients is 76.8 years old, but this patient is 5 years older than the oldest patient in the ADNI study.

DISCUSSION

Here, we investigated immune and cognitive effects of add-on ω-3 supplementation to CI therapy in twenty eight patients with neurodegenerative diseases. Our observational study suggests that, in a cohort of 8 MCI patients failing CI, the add-on ω-3 therapy upregulates transcription of energy and circadian genes in PBMC and macrophages, inproves Aβ phagocytosis, and delays progression to dementia by 26 to 54 months (Table 1). Cognitive decline is not irreversible and patients recover from decline on supplementation.

We examined the transcription of energy genes in PBMC and macrophages. Bioenergy from glycolysis and/or TCA cycle is essential for macrophage phagocytosis. ω-3 treatment of macrophages in vitro upregulated all energy genes and ARNTL2 but downregulated CLOCK and ARNTL. CLOCK gene transcript increased over time in PBMC of MCI patients. In the oldest patient (93-year-old after 6 years in the study), we showed an association between upregulation of energy gene transcripts in PBMC and cognitive improvement. This patient had a slightly higher than average decline in FDG uptake in temporo-parietal area; however, her age exceeds by 5 years the age of the oldest patient in the ADNI study.

Circadian rhythm disorders are a common occurrence in patients with AD [20]. CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer activates circadian rhythm genes through binding to E-box sites on DNA. CLOCK/BMAL-1 has anti-inflammatory function in bronchiolar epithelial cells where BMAL-1 ablation leads to exaggerated inflammatory response [27]. In AD patients, increased inflammation is suggested by the association of periventricular white matter intensities involving microstructural damage with peripheral inflammatory markers, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-21, and IL-23 [28]. ARNTL2, a circadian regulator, is a transcriptional repressor of the IL-21 gene associated with peripheral inflammatory response in AD [28, 29]. We investigated the effect of ω-3 in vitro and the effect of add-on ω-3 supplementation to CI therapy on circadian rhythm genes in vivo (Fig. 3). In the ω-3-supplemented patient #14, two principal circadian gene regulators, CLOCK and ARNTL2, increased in parallel with the improvement of cognitive status.

Macrophages have key role in brain clearance of oligomeric Aβ by monocyte/macrophages, which, however, fail in AD patients [17]. This defectiveness is associated with transcriptional defects in glycosylation, unfolded protein response [18], and energy and circadian genes. We demonstrate in our previous and current studies [10, 17] that ω-3 partially repair these defects. The Aβ phagocytosis blood test results [26, 30] demonstrate immune improvement of macrophage function by ω-3 supplementation and highlight the stages from normal to AD [5, 11]. The parallel changes in cognition and gene transcription in patient #14 and other patients are a compelling evidence of ω-3 effects and the rationale for development of immune therapy of MCI macrophages using energetic molecules, including ω-3, carnitine, and other molecules.

The results of this study, restricted by an uncontrolled design and a small sample, suggest that add-on ω-3 extend cognitive benefits of CI 2 to 4.5 years beyond CI alone through immune effects on macrophage phagocytosis and biochemical effects on energy and circadian genes.

Fig. 5.

Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in parieto-temporal area: Comparison of change per month of ADNI patients to patient #14 by age. The age of patient #14 is above the age limit in the comparison group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kevin Williams for the lipidomic analysis of ω-3 drink Smartfish.

Smartfish Company supported this research by a grant to UCLA and providing the Smartfish drink to the patients who requested it. Smartfish Company was not involved in the design, analysis, interpretation of the data, and submission of the article for publication.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0252r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J (2010) Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: Are they effective? PT 35, 208–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Birks JS, Harvey RJ (2018) Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6, CD001190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tolar M, Abushakra S, Sabbagh M (2020) The path forward in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics: Reevaluating the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Alzheimers Dement. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.09.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Magierski R, Sobow T (2015) Benefits and risks of add-on therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegener Dis Manag 5, 445–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fiala M, Kooij G, Wagner K, Hammock B, Pellegrini M (2017) Modulation of innate immunity of patients with Alzheimer’s disease by omega-3 fatty acids. FASEB J 31, 3229–3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Calder PC (2017) Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: FFrom molecules to man. Biochem Soc Trans 45, 1105–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bazan NG (2013) The docosanoid neuroprotectin D1 induces homeostatic regulation of neuroinflammation and cell survival. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 88, 127–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Freund-Levi Y, Eriksdotter-Jonhagen M, Cederholm T, Basun H, Faxen-Irving G, Garlind A, Vedin I, Vessby B, Wahlund LO, Palmblad J (2006) Omega-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study: A randomized double-blind trial. Arch Neurol 63, 1402–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Quinn JF, Raman R, Thomas RG, Yurko-Mauro K, Nelson EB, Van Dyck C, Galvin JE, Emond J, Jack CR Jr., Weiner M, Shinto L, Aisen PS (2010) Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: A randomized trial. JAMA 304, 1903–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fiala M, Restrepo L, Pellegrini M (2018) Immunotherapy of mild cognitive impairment by omega-3 supplementation: Why are amyloid-beta antibodies and omega-3 not working in clinical trials? J Alzheimers Dis 62, 1013–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Famenini S, Rigali EA, Olivera-Perez HM, Dang J, Chang MT, Halder R, Rao RV, Pellegrini M, Porter V, Bredesen D, Fiala M (2017) Increased intermediate M1-M2 macrophage polarization and improved cognition in mild cognitive impairment patients on omega-3 supplementation. FASEB J 31, 148–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vaughan RA, Garcia-Smith R, Bisoffi M, Conn CA, Trujillo KA (2012) Conjugated linoleic acid or omega 3 fatty acids increase mitochondrial biosynthesis and metabolism in skeletal muscle cells. Lipids Health Dis 11, 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zamroziewicz MK, Paul EJ, Zwilling CE, Barbey AK (2017) Predictors of memory in healthy aging: Polyunsaturated fatty acid balance and fornix white matter integrity. Aging Dis 8, 372–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Herbst EA, Paglialunga S, Gerling C, Whitfield J, Mukai K, Chabowski A, Heigenhauser GJ, Spriet LL, Holloway GP (2014) Omega-3 supplementation alters mitochondrial membrane composition and respiration kinetics in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 592, 1341–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shadel GS, Horvath TL (2015) Mitochondrial ROS signaling in organismal homeostasis. Cell 163, 560–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sena LA, Chandel NS (2012) Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 48, 158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fiala M, Liu PT, Espinosa-Jeffrey A, Rosenthal MJ, Bernard G, Ringman JM, Sayre J, Zhang L, Zaghi J, Dejbakhsh S, Chiang B, Hui J, Mahanian M, Baghaee A, Hong P, Cashman J (2007) Innate immunity and transcription of MGAT-III and Toll-like receptors in Alzheimer’s disease patients are improved by bisdemethoxycurcumin. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA 104, 12849–12854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Olivera-Perez HM, Lam L, Dang J, Jiang W, Rodriguez F, Rigali E, Weitzman S, Porter V, Rubbi L, Morselli M, Pellegrini M, Fiala M (2017) Omega-3 fatty acids increase the unfolded protein response and improve amyloid-beta phagocytosis by macrophages of patients with mild cognitive impairment. FASEB J 31, 4359–4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liang WS, Dunckley T, Beach TG, Grover A, Mastroeni D, Ramsey K, Caselli RJ, Kukull WA, McKeel D, Morris JC, Hulette CM, Schmechel D, Reiman EM, Rogers J, Stephan DA (2010) Neuronal gene expression in non-demented individuals with intermediate Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Neurobiol Aging 31, 549–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Musiek ES, Xiong DD, Holtzman DM (2015) Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Exp Mol Med 47, e148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Greig MT, Potter E, Barker W, Raj A, Schinka J, Borenstein A, Schoenberg M, Wu Y, Banko J, Potter H (2011) Pre-MCI and MCI: Neuropsychological, clinical, and imaging features and progression rates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 19, 951–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E (1999) Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 56, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR (2013) STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Avagyan H, Goldenson B, Tse E, Masoumi A, Porter V, Wiedau-Pazos M, Sayre J, Ong R, Mahanian M, Koo P, Bae S, Micic M, Liu PT, Rosenthal MJ, Fiala M (2009) Immune blood biomarkers of Alzheimer disease patients. J Neuroimmunol 210, 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gibbs J, Ince L, Matthews L, Mei J, Bell T, Yang N, Saer B, Begley N, Poolman T, Pariollaud M, Farrow S, DeMayo F, Hussell T, Worthen GS, Ray D, Loudon A (2014) An epithelial circadian clock controls pulmonary inflammation and glucocorticoid action. Nat Med 20, 919–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Swardfager W, Yu D, Ramirez J, Cogo-Moreira H, Szilagyi G, Holmes MF, Scott CJ, Scola G, Chan PC, Chen J, Chan P, Sahlas DJ, Herrmann N, Lanctot KL, Andreazza AC, Pettersen JA, Black SE (2017) Peripheral inflammatory markers indicate microstructural damage within periventricular white matter hyperintensities in Alzheimer’s disease: A preliminary report. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 7, 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lebailly B, He C, Rogner UC (2014) Linking the circadian rhythm gene Arntl2 to interleukin 21 expression in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 63, 2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fiala M, Cribbs DH, Rosenthal M, Bernard G (2007) Phagocytosis of amyloid-beta and inflammation: Two faces of innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 11, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]