Abstract

In bacteria, phospholipids are synthesized on the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane and must translocate to the outer leaflet to propagate a bilayer. Transbilayer movement of phospholipids has been shown to be fast and independent of metabolic energy, and it is predicted to be facilitated by membrane proteins (flippases) since transport across protein-free membranes is negligible. However, it remains unclear as to whether proteins are required at all and, if so, whether specific proteins are needed. To determine whether bacteria contain specific proteins capable of translocating phospholipids across the cytoplasmic membrane, we reconstituted a detergent extract of Bacillus subtilis into proteoliposomes and measured import of a water-soluble phospholipid analog. We found that the proteoliposomes were capable of transporting the analog and that transport was inhibited by protease treatment. Active proteoliposome populations were also able to translocate a long-chain phospholipid, as judged by a phospholipase A2-based assay. Protein-free liposomes were inactive. We show that manipulation of the reconstitution mixture by prior chromatographic fractionation of the detergent extract, or by varying the protein/phospholipid ratio, results in populations of vesicles with different specific activities. Glycerol gradient analysis showed that the majority of the transport activity sedimented at ∼4S, correlating with the presence of specific proteins. Recovery of activity in other gradient fractions was low despite the presence of a complex mixture of proteins. We conclude that bacteria contain specific proteins capable of facilitating transbilayer translocation of phospholipids. The reconstitution methodology that we describe provides the basis for purifying a facilitator of transbilayer phospholipid translocation in bacteria.

Transbilayer movement of phospholipids is a rapid process in many, but not all, biological membranes (7, 8, 26, 43). Since flip-flop is very slow in pure lipid bilayers (18), it is generally assumed that biological membranes are equipped with some mechanism to accelerate transport. The plasma membrane of eucaryotes possesses a number of distinct lipid translocation activities that are dependent on ATP or Ca2+. These include the aminophospholipid translocase (8, 6, 23, 36), products of certain members of the multidrug resistance (mdr) gene family (31, 34, 38, 39), and a unique Ca2+-stimulated, nonspecific lipid translocase (the phospholipid scramblase) that has been purified and cloned (1, 44). In contrast to the progress in identifying lipid translocators situated in eucaryotic plasma membranes, very little is known about lipid translocators in biogenic (self-synthesizing) membranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum and the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria. Phospholipid biosynthesis occurs on the cytoplasmic face of these membranes (2, 29, 42), and in order to form a bilayer the phospholipids must translocate to the opposite leaflet at a rate compatible with cell growth. Flip-flop in these membranes has been found to be fast, with measured half-times ranging from 15 s to several minutes (3, 5, 11–14, 32). Although the measured rate of transport varied between assays, possibly due to differences in methodology, all observations to date indicate that transport is independent of metabolic energy, nonspecific toward the phospholipid head group, and probably mediated by proteins (flippases) (11, 12, 20). However, the mechanisms by which phospholipids translocate back and forth across the bilayer are unknown, and the flippases responsible have not been identified.

We previously used fluorescent phospholipid analogs to measure phospholipid flip-flop in Bacillus megaterium membrane vesicles (11) and demonstrated rapid transport with a half-time of ∼30 s. We found that transport was protease sensitive and nonspecific toward the phospholipid head group. We also showed that vesicles made from B. megaterium phospholipids were inactive in the assay, consistent with the idea that bacterial proteins were directly or indirectly responsible for lipid translocation. Similar results were found in membrane vesicles from the inner membrane of Escherichia coli, using both fluorescent and natural phospholipids (12, 13).

To begin a biochemical identification of the mechanism responsible for transbilayer movement of phospholipids in bacterial membranes, we chose to reconstitute the activity from a detergent extract of B. subtilis membranes. Our results clearly show that proteoliposomes reconstituted from the detergent extract can support transbilayer movement of a phospholipid analog as well as long-chain phosphatidylcholine, whereas protein-free liposomes are inactive. Additional analyses demonstrate that activity is due to specific proteins. These results, and the methodology that we describe, lay the groundwork for future purification of a bacterial phospholipid flippase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and routine procedures.

Antibiotic medium 3 was from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.), proteinase K, DNase I, and Triton X-100 were from Boehringer-Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.), n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.), and egg phosphatidylcholine (egg PC) was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). SM-2 BioBeads were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, Calif.). Silica 60 thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates were from EM Science (Gibbstown, N.J.). l-α-Dipalmitoyl-[3H]phosphatidylcholine (∼80 Ci/mmol), d-[2-3H(N)]-mannose (∼20 Ci/mmol), d-[1-14C]mannose (∼53 mCi/mmol), and inulin[methoxy-3H] (∼130 mCi/g) were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. (St. Louis, Mo.). All other chemicals and reagents were from Sigma.

Phospholipids were quantitated by total phosphorus assay (33). Protein was determined using the Micro BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay reagent from Pierce Chemical Co. (Rockford, Ill.). Samples with a low protein/phospholipid ratio were delipidated prior to protein measurement as described by Wessel and Flügge (41).

Synthesis of [3H]diC4PC.

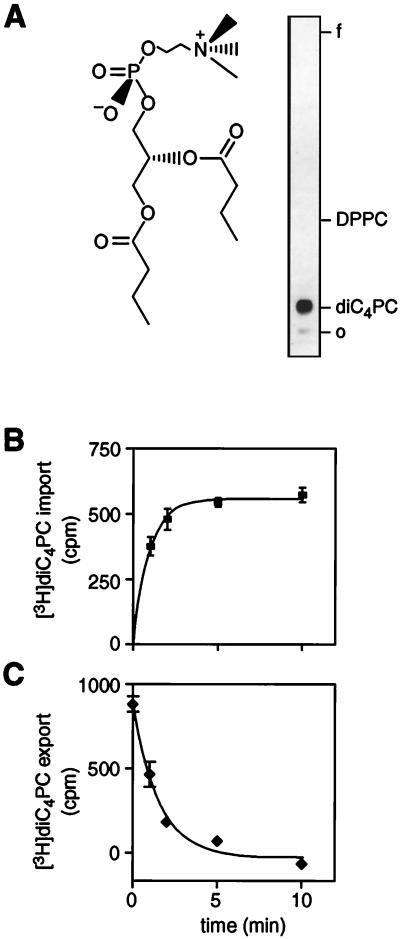

Radiolabeled dibutyroylphosphatidylcholine (Fig. 1A) was prepared essentially as described by Bishop and Bell (3), with the following modifications. Syntheses were performed on the 50- to 100-μmol scale. A mixture of [choline-methyl-3H]dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine([choline-methyl-3H]DPPC) and nonradioactive DPPC (mixed to yield a specific activity approximately 3,000 cpm/nmol) was deacylated with mild alkali (16). The resulting [3H]glycerophosphocholine was isolated by phase separation (16), dried in a rotary evaporator, coevaporated several times with dry benzene (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, Wis.) to ensure dryness, and chemically reacylated by incubation in a chloroform solution containing butyric anhydride and diaminopyridine (10). Dibutyrylphosphatidylcholine was purified on a silica column (silica gel, 70/230 mesh; ∼8-ml bed volume). The column was rinsed with 5 column volumes of chloroform, followed by 5 volumes of 2:1 (vol/vol) chloroform-methanol. The product, [choline-methyl-3H]dibutyroylphosphatidylcholine, ([3H]diC4PC), was then eluted with 1:2 (vol/vol) chloroform-methanol. Fractions containing radioactivity were identified by liquid scintillation counting and characterized initially by TLC using silica 60 plates and chloroform-methanol-acetic acid-water (25:15:4:2, by volume) as the solvent system (Fig. 1A). Pure fractions were pooled and quantitated precisely with liquid scintillation counting and lipid phosphorus measurement (33). Typical yields were in the range of 60 to 80% of the starting radioactive DPPC, and the purity of diC4PC was ∼95%. The molecular mass of the product was verified by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry (M + H+ 398.2). The [3H]diC4PC was stored at −20°C in chloroform. Prior to use, the organic solvent was evaporated and the [3H]diC4PC was dissolved in the assay buffer.

FIG. 1.

DiC4PC transport in B. subtilis membrane vesicles. (A) Structure of diC4PC. [3H]diC4PC was synthesized and purified as described in Materials and Methods. The product was analyzed by TLC using chloroform-methanol-acetic acid-water (25:15:4:2, by volume) as the solvent system. O, origin, f, solvent front. (B) BSV (36 μg of protein/assay) were incubated at 35°C in the presence of ∼6 mM [3H]diC4PC (2,952 cpm/nmol). At the indicated times, the incubation mixtures were diluted 40-fold into ice-cold buffer and immediately filtered. The filters were washed with ice-cold buffer, transferred to scintillation vials, and counted. The background (zero time point) was subtracted from the data points. The line represents a single exponential fit of the data. The amplitude of the plot corresponds to an uptake of ∼5.3 pmol of diC4PC per μg of protein. (C) BSV (36 μg of protein/assay) were incubated with ∼6 mM [3H]diC4PC for 20 min, then diluted 40-fold in ice-cold buffer, and further incubated at 35°C for the indicated times. Data are corrected for the assay background. The solid line is a single exponential decay fit of the data. The start point of the export experiment corresponds to 8.3 pmol of diC4PC per μg of protein. Error bars show the standard deviation between two samples.

Preparation of B. subtilis membrane vesicles.

B. subtilis strain 1E51 (DB105, hisH aprEΔ nprE1 nprR2 pgr71; Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, Iowa State University) was used in this study. This strain has several protease genes deleted and was chosen in order to minimize proteolysis during cell breaking and reconstitution procedures. Initial experiments, comparing diC4PC transport in membrane vesicles between strains 1E51 and 168, showed no difference between the strains (data not shown).

B. subtilis strain 1E51 was grown in Penassay broth (antibiotic medium 3; Difco Laboratories) at 37°C and harvested in the log phase of growth by centrifugation. Right-side-out B. subtilis vesicles (BSV) were prepared by hypotonic lysis of protoplasts by a variation (11) of the method described by Konings et al. (17). Inside-out membrane vesicles (iBSV) were prepared by passing cells through a French pressure cell. Briefly, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with water, and resuspended in 50 mM triethanolamine (TEA)–0.25 M sucrose–10 mM MgSO4, (pH 7.5) to give a ∼60-fold-concentrated cell suspension. The suspension was supplemented with 0.2 mg of DNase I/ml of cells and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; from a 150 mM stock in isopropanol) and passed two to three times through a French press at a cell pressure of 103 kPa. Dithiothreitol (0.5 mM) was added before each pass. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 6,500 × g for 10 min in a JA 14 rotor. The iBSV were collected by centrifugation at 45,000 rpm for 2 h in a Ti 50.2 rotor (∼245,000 × g) and resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.5) to ∼5 mg of protein/ml. B. subtilis lipids were obtained by extracting the iBSV by the method of Bligh and Dyer (4). The lipid extract was dissolved in chloroform and stored at −20°C.

Reconstitution protocol.

iBSV were salt washed by incubation for 1 h on ice in 25 mM TEA–125 mM sucrose–1 M potassium acetate–1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 7.5). The vesicles were reisolated by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 mM HEPES–200 mM NaCl (pH 7.5); 10% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 in the same buffer was added to give a final concentration of 1%. The detergent/phospholipid ratio varied but was generally 10 mg of Triton X-100/μmol of phospholipid. After 1 h on ice, the undissolved material was removed by centrifugation in a Beckman TLA 100.3 rotor for 30 min at 75,000 rpm (∼230,000 × g). The supernatant was diluted twofold into egg PC dissolved in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)–1% Triton X-100. In a parallel sample, a comparable amount of B. subtilis lipids was used instead of the Triton X-100-soluble fraction. [3H]mannose, [14C]mannose, or inulin[methoxy-3H] was added to the detergent solutions as a soluble vesicle content marker. SM-2 BioBeads were washed twice with methanol, three times with water, and once with 10 mM HEPES–100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (HS buffer); 100 mg of washed beads was added per ml of detergent solution, and the samples were rotated at room temperature for 3 to 4 h. After incubation, the increased turbidity of the solution indicated vesicle formation. Freshly washed beads (200 mg/ml of solution) were then added, and the suspension was rotated at 4°C overnight. In some experiments, the suspension was incubated for an additional 2 h at room temperature after addition of the second portion of beads before incubation overnight at 4°C. The vesicles were collected by centrifugation in a Beckman TLA 100.3 rotor (45 min at ∼230,000 × g), and the pellet was washed once in HS buffer. The vesicles were resuspended in HS buffer at a final phospholipid concentration of ∼11 mM, and [3H]diC4PC uptake measurements were carried out the same day. Protein recovery in the reconstituted vesicles was ∼23% and phospholipid recovery was ∼66% of the amount in the starting material. In initial experiments the ratio of protein to phospholipid was ∼230 μg of protein/μmol of phospholipid in the proteoliposomes, but in later experiments the amount of protein was decreased (see figure legends for individual experiments).

Triton X-100 absorbance at 275 nm was used to follow the removal of detergent during the reconstitution (E1 cm1% in 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5]–100 mM NaCl was 21); 600 μl of methanol and 300 μl of chloroform were added to 150 μl of sample. The sample was vortexed and centrifuged to remove precipitated protein. The absorbance at 275 nm was measured, and Triton X-100 concentration was calculated from measurements of identically treated standards. After 1.5-h, 3-h, and overnight incubation at room temperature with SM-2 BioBeads, ∼75%, ∼92%, and ∼99%, respectively, of the Triton X-100 had adsorbed to the beads. When the room temperature incubation was extended for an additional 2 h, 99.5% of the Triton X-100 was removed. The final concentration of Triton X-100 in the reconstituted vesicle preparations was less than 0.01% (wt/vol).

To determine if phospholipid degradation was occurring during the reconstitution procedure, the Triton X-100-soluble fraction from B. subtilis and the Bligh-Dyer extract from the same membrane were reconstituted as described above except that 1 of μCi of [3H]DPPC was added to each sample. After reconstitution, lipids were extracted from the vesicles by the procedure of Bligh and Dyer and analyzed by TLC using chloroform-methanol-water (65:25:4, by volume) as the mobile phase. Radioactivity on the TLC plate was detected using a Berthold LB2842 TLC scanner, and unlabeled lipids were visualized with I2 vapor.

DiC4PC transport assay.

[3H]DiC4PC in chloroform was dried under nitrogen and dissolved in HS buffer to give the desired concentration (usually 30 mM). Then 20-μl aliquots of the vesicles were pipetted into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and kept on ice until required. The vesicles were preincubated for 1 min at the assay temperature and transport was initiated by adding [3H]diC4PC in HS buffer (usually 5 μl) and gently vortexing. The final concentration of [3H]diC4PC was generally ∼6 mM. Transport was stopped by diluting the incubation mixture into 1 ml of ice-cold HS buffer (40-fold dilution) and immediately filtering through a HA 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore) using a Hoefer filter manifold. The filter chamber was cooled, and the filters were wetted by filtering 5 ml of ice-cold HS buffer ∼10 s prior to filtering the sample. The reaction tubes were washed once with 1 ml of ice-cold HS buffer, and the filter was washed with an additional 5 ml of buffer. The assay background was determined by diluting the vesicles with 1 ml of ice-cold HS buffer before adding the [3H]diC4PC and then filtering as described above. The filters were transferred to 20-ml glass scintillation vials; 100 μl of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added, followed by 10 ml of Ready Safe scintillation fluid (Research Products International, Mount Prospect, Ill.). Radioactivity was measured after the filters had dissolved. Experimental points were corrected by subtracting the background from each experiment.

For [3H]diC4PC export experiments, 20 μl of BSV was incubated with 6.0 mM [3H]diC4PC for 20 min at 35°C to allow the diC4PC concentration to reach equilibration in the vesicles. The loaded BSV were then diluted 40-fold in HS buffer and incubated for various times at 35°C before being filtered as described above.

To check if [3H]diC4PC was metabolized during the assay, 200 μl of BSV was incubated at 37°C with 5 mM [3H]diC4PC for 5 and 30 min. After filtration as above, the filters were sequentially extracted with 0.8 ml of water, 2 ml of methanol, 0.9 ml of methanol-water (5:4, vol/vol), 1 ml of chloroform, and 1 ml of chloroform-methanol (1:1, vol/vol). The extracts were combined, centrifuged to remove filter particles, and dried under nitrogen. Pellets were dissolved in 950 μl of chloroform-methanol-water (1:2:0.8, vol/vol/vol), and phase separation was induced by adding 200 μl of chloroform and 200 μl of water. Approximately 70% of the radioactivity was found in the upper phase. The upper and lower phases were analyzed by TLC, using chloroform-methanol-acidic acid-water (25:15:4:2, by volume) as the mobile phase, and radioactivity on the TLC plate was detected with a Berthold LB2842 TLC scanner.

Calculations.

DiC4PC is transported from the extravesicular volume, through the bilayer, and into the intravesicular space. In a passive, bidirectional transport model, the intravesicular concentration of diC4PC at equilibrium is expected to be the same as the starting concentration of the diC4PC in the sample. The exact concentration of [3H]diC4PC in each experiment was determined by measuring the radioactivity in a sample of the [3H]diC4PC stock in buffer and calculated from the known specific activity (counts per minute per nanomole of phospholipid) of each [3H]diC4PC preparation. Thus, from the amount of 3H (counts per minute) associated with the vesicles at equilibrium (the amplitude from a single-phase exponential fit of transport, or in some instances the transport after 15 min), the total intravesicular volume occupied by [3H]diC4PC can be calculated (cpm/specific activity of [3H]diC4PC/[3H]diC4PC concentration). The amount of trapped soluble marker ([14C]- or [3H]mannose or inulin[methoxy-3H] [counts per minute]) was obtained by filtering vesicles as described in the diC4PC assay. The soluble marker concentration (counts per minute per microliter) in each sample was determined by counting a small sample before reconstitution. The intravesicular mannose volume was then calculated: cpm on filter/cpm/μl in starting solution. The fraction of the intravesicular volume occupied by diC4PC (percent occupancy) can thus be calculated: μl of diC4PC/μl of mannose.

Electron microscopy.

For electron microscopy, a suspension of proteoliposomes or liposomes was diluted 50-fold in 100 mM NaCl–10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). A drop of the diluted suspension was placed on a carbon-coated copper grid treated with denatured bovine serum albumin. After the vesicles were allowed to adsorb, the grid was washed with ammonium acetate (200 mM) and glycerol (10%). Vesicles were stained with 5% uranyl acetate and 5% glycerol and then washed with a few drops of water containing 5% glycerol. The grid was then shadowed with platinum and examined in a Philips 300 electron microscope. Photographs of fields of vesicles were taken, and vesicle diameters were measured by projecting images of the grid onto a ground glass surface. Photographs of a calibration grid were taken and measured in parallel.

Protease treatment.

The Triton X-100-soluble fraction of B. subtilis membrane (Triton extract) was reconstituted in the presence of [14C]mannose to obtain proteoliposomes with 7.8 μg of protein/μmol of phospholipid. Aliquots of the proteoliposomes (∼0.1 mg of protein/ml) were incubated at room temperature for the indicated time with 0.5 or 1 mg of proteinase K/ml. Proteolysis was stopped by adding ∼3 mM PMSF, and the samples were stored on ice and assayed within 15 min. A control sample was incubated with buffer only, then treated with PMSF, and assayed. The amount of [14C]mannose associated with the proteoliposomes remained constant, indicating that proteolysis did not disrupt the vesicles.

DEAE chromatography.

DEAE fractionation was performed at 4°C. A 300-μl aliquot of a Triton extract (obtained as described above) was applied to a ∼0.5-ml column of DE-52 (Whatman International Ltd., Maidstone, England) that had been preequilibrated with 20 mM TEA (pH 7.5)–50 mM NaCl–1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100. The column was rinsed with 10 column volumes of the starting buffer, and the bound material was eluted with 10 column volumes of 100 mM NaCl followed by 10 column volumes of 250 mM NaCl, both in 20 mM TEA (pH 7.5)–1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100. The first 1 ml of the unbound material and the two elution steps were collected and reconstituted separately as described above; 100 μl of the starting Triton extract was also reconstituted. The NaCl concentration was adjusted to 100 mM in all fractions before the detergent was removed.

Glycerol gradient.

Triton extract (500 μl) was loaded onto 4.8 ml of a 10 to 25% glycerol gradient in 1% Triton X-100 in HS buffer. The gradient was centrifuged at 4°C for 20 h at 37,000 rpm in an SW 50.1 rotor (∼165,000 × g), and ∼0.4-ml fractions were collected from the top. The top fraction was disregarded, and the next eight fractions were pooled pairwise to yield pools 1 to 4; the remaining three fractions were combined to yield pool 5. Pools from two gradients were combined and dialyzed for 1.5 h against 1% Triton X-100 in HS buffer. The pools and part of the Triton extract (kept at 4°C overnight) were reconstituted separately as described above, using inulin as a content marker. The amount of diC4PC transported after 15 min at 25°C was measured the same day. Protein and phospholipid concentrations were measured in the reconstituted pools and delipidated protein samples separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The protein/phospholipid ratio was between 3 and 11 μg/μmol in the reconstituted samples, all within the dynamic range of the diC4PC assay. A mixture of standards, containing 125 μg each of cytochrome c (2.1S), ovalbumin (3.6S), bovine serum albumin (4.35S), alcohol dehydrogenase (7.6S), β-amylase (8.9S), apotransferrin (17.7S), and thyroglobulin (19.4S), was loaded onto a separate gradient and fractionated as described for the samples. The fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

PLA2 treatment of liposomes and proteoliposomes.

The Triton extract was reconstituted as described above except that [3H]DPPC was added to the detergent solutions (1.25 μCi/μmol of egg PC). Different amounts of the Triton extract were used to produce proteoliposomes with increasing protein/phospholipid ratios. Liposomes containing egg PC and [3H]DPPC were made similarly. Reconstituted vesicles were resuspended in HS buffer, supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2, to give ∼5 mM phospholipid. A 30-μl sample was incubated with phospholipase A2 (PLA2; 1 U/μl; from Naja naja venom [Sigma]; 200 U/μmol of phospholipid) at 29°C for 30 min (10-min incubation gave the same amount hydrolyzed in the liposomes). Hydrolysis was stopped by adding 30 μl of 120 mM EGTA and 40 μl of H2O, and samples were immediately extracted by the procedure of Bligh and Dyer (4). Extracted lipids were analyzed by TLC on silica 60 plates, using chloroform–methanol–28% ammonia (65:25:5, by volume) as the mobile phase. Radioactivity on the TLC plates was detected with a Berthold LB2842 TLC scanner. Control samples (with buffer instead of PLA2) as well as samples disrupted with 0.5% Triton X-100 were treated identically.

RESULTS

To measure phospholipid translocation across B. subtilis membranes and reconstituted vesicle membranes, we used [3H]diC4PC (Fig. 1A), a water-soluble analog of phosphatidylcholine (3). Although phosphatidylcholine is not found in B. subtilis, previous observations (11) indicated that phospholipid flip-flop in Bacillus membranes does not discriminate between various glycerophospholipid head groups, allowing us to use this easily prepared water-soluble analog for assay purposes. When incubated with membrane vesicles, the analog is presumed to associate with the outer leaflet of the vesicle membrane, undergo facilitated translocation to the opposite leaflet, and then partition into the intravesicular space. The assay consists of incubating vesicles with [3H]diC4PC, then separating vesicles from the incubation medium by filtration, and washing them on a filter manifold. Filter-bound vesicles are then taken for scintillation counting to determine the amount of [3H]diC4PC that they contain.

DiC4PC transport in B. subtilis membrane vesicles.

[3H]diC4PC uptake was measured in two different B. subtilis membrane preparations: BSV, made by hypotonic lysis of spheroplasts, and iBSV, prepared by homogenizing the cells in a French press. A representative time course for uptake with the BSV preparation is shown in Fig. 1B; similar results were obtained with iBSV. Single exponential fits of the data yielded rate constants in the range of 0.45 to 0.61 min−1 (half-time of ∼1 min) for both membrane preparations, as well as for salt-washed iBSV that were stripped of peripheral membrane proteins. The data indicate that [3H]diC4PC is taken up rapidly in all of these membrane preparations. Since BSV and iBSV are topologically opposite vesicle preparations, these data suggest that the transport of diC4PC in these vesicles is bidirectional. To measure directly the export of diC4PC, BSV were preloaded with [3H]diC4PC by incubation at 35°C for 20 min. Export of [3H]diC4PC was then induced by diluting the vesicles into buffer. A representative time course for export is shown in Fig. 1C, and analyses of several experiments yielded an export rate constant of ∼0.53 min−1 (half-time of ∼1 min). From these data, it is clear that diC4PC exits the membrane vesicles rapidly with a rate indistinguishable from that measured for import. Thus, B. subtilis membranes are able to sustain bidirectional transport of diC4PC, in agreement with results obtained using fluorescent phospholipid analogs (11) or metabolically labeled bacterial phospholipids (32).

Reconstitution of diC4PC transport in proteoliposomes.

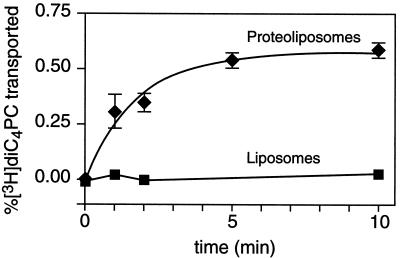

To analyze the mechanism responsible for transbilayer movement of phospholipids in B. subtilis, we reconstituted proteoliposomes from detergent-solubilized iBSV and assayed for [3H]diC4PC uptake. As a test of the reconstitution procedure and to establish that residual detergent was not a factor in increasing transbilayer movement (19), we reconstituted a B. subtilis lipid fraction identically. The iBSV were solubilized in 1% Triton X-100, and insoluble material was removed by ultracentrifugation. The supernatant so obtained was supplemented with egg PC before adding SM-2 BioBeads to remove detergent. Greater than 99% of the starting Triton X-100 was removed during the reconstitution procedure. The resulting proteoliposomes showed time-dependent uptake of [3H]diC4PC (Fig. 2) with a half-time ∼1 min. Liposomes containing a comparable amount of B. subtilis lipids mixed with egg PC were inactive. Since the amplitude of the assay signal depends on intravesicular volume, it was conceivable that the lack of measurable transport in the liposomes was the result of their being much smaller than the proteoliposomes. We therefore included [3H]mannose in the solutions prior to vesicle reconstitution to provide an indicator of intravesicular volume. The amount of [3H]mannose associated with the proteoliposomes and liposomes after reconstitution was similar (data not shown), indicating similar total volumes. Furthermore, it was evident from measurements of the amount of filter-bound [3H]mannose (in the absence of [3H]diC4PC) that the different vesicles were similarly retained on the filter (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Reconstitution of diC4PC transport. The Triton X-100-soluble fraction from iBSV was mixed with egg PC, and the detergent was removed by incubation with SM-2 BioBeads (see Materials and Methods). The resulting proteoliposomes contained ∼28 μg of protein/μmol of phospholipid. B. subtilis lipids were reconstituted identically to obtain liposomes containing comparable proportions of B. subtilis lipids (∼0.13 μmol/μmol of egg PC). [3H]diC4PC transport was assayed as described for Fig. 1. Data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation of two measurements. The solid line for proteoliposomes is a single exponential fit of the data.

The reconstitution protocol involves an incubation period of several hours at room temperature and overnight at 4°C, leaving open the possibility that lipids are degraded during reconstitution. This is potentially a problem with protein-containing samples that may have active lipases. However, TLC of extracted lipids from proteoliposomes and liposomes containing B. subtilis lipids showed no degradation of phosphatidylcholine and no detectable changes in lipid profile (data not shown). The transport activity in the proteoliposomes is therefore unlikely to be the result of lipid metabolism. We also determined whether [3H]diC4PC was being metabolized during the assay. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C with BSV, vesicle-associated [3H]diC4PC appeared intact, and no radioactive metabolites were detected (data not shown).

Taken together, the data indicate that a Triton extract of B. subtilis membrane contains a component, not found in a chloroform-methanol (lipid) extract of the same membrane, that allows transport of diC4PC. Given the nature of the two extracts, the active component is likely to be a protein.

Vesicle size.

The total intravesicular volume can be estimated from the amount of soluble content marker associated with the vesicles. The average volume from many different reconstitutions was 13 (±7, n = 29) μl/μmol of phospholipid, corresponding to an average external diameter of 386 nm, if one assumes unilamellar vesicles (see Materials and Methods and reference 27). This number was somewhat dependent on the protein/phospholipid ratio, since vesicles prepared with less protein had a larger average size (data not shown). To obtain an independent estimate of vesicle size and heterogeneity, we used electron microscopy to measure the diameter of vesicles in negatively stained preparations (data not shown). The micrographs revealed that most of the vesicles were round, with a mean diameter (deduced from the mean volume) of 235 nm (155 vesicles measured). The trapped volume ([3H]mannose space) in this particular vesicle preparation was 10.1 μl/μmol of phospholipid, which gives an average diameter of 309 nm. If a significant portion of the vesicles were multilamellar, the size calculated from the trapped volume would be expected to be much less than the size deduced from electron microscopy. The corresponding numbers for the lipid-only vesicles were 229 nm deduced from the volume histogram and 234 nm deduced from the [3H]mannose trapping data. Results from vesicles reconstituted with inulin (∼5,000 Da) as the content marker were similar (data not shown). Since the trapped soluble marker data provide an overestimate of the intravesicular volume (no corrections were made for extravesicular radioactivity), we conclude that both measurements provide a consistent estimate of vesicular size and that the majority of the vesicles are unilamellar.

Effect of protein concentration on transport.

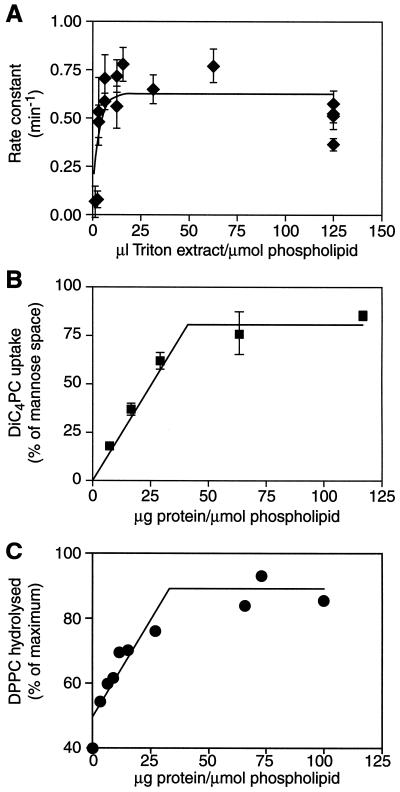

Our data show that the Triton X-100-soluble fraction of B. subtilis membrane contains some component(s) that facilitates transport of diC4PC across the bilayer. We therefore expected that the concentration of this component in the proteoliposomes would affect transport. To test this, we created a series of proteoliposomes containing different amounts of the Triton X-100-soluble fraction and measured the rate and extent of [3H]diC4PC uptake. As shown in Fig. 3A, the rate of transport is not affected by decreasing protein/phospholipid ratio; as long as there is any transport, the rate remains relatively constant. Since data from experiments with B. megaterium membrane vesicles (11) using fluorescent phospholipid analogs gave transport half-times of ∼30 s and the rate of transport of newly synthesized phospholipids in E. coli inner membrane was measured with a half-time of less than 15 s (13), it is likely that the transbilayer movement of diC4PC is considerably faster than the observed rate (half-time of ∼1 min). Thus, the apparent rate in our assay is governed by other processes such as the association of the analog with the membranes.

FIG. 3.

Effect of protein concentration on transport. (A) Proteoliposomes were prepared with increasing amount of the Triton extract, and diC4PC uptake was measured as before. The rate constant was calculated from a one-phase exponential fit of time courses at each concentration. Error bars are the standard error from the nonlinear regression. The solid line is the one-phase exponential fit of the data. (B) The diC4PC uptake at equilibrium was measured over a range of protein/phospholipid ratios. All measurements were done in duplicate; error bars are the cumulative standard deviation. (C) Proteoliposomes containing [3H]DPPC and increasing amounts of the Triton extract were incubated with PLA2 for 30 min. The amount hydrolyzed is shown as a percentage of the maximal amount hydrolyzed in disrupted controls; data are from two independent experiments.

The extent of [3H]diC4PC uptake at equilibrium was dependent on the protein/phospholipid ratio in the proteoliposomes (Fig. 3B). The data are shown as percent occupancy, i.e., the percentage of intravesicular volume (calculated from filter-bound [3H]mannose) occupied by [3H]diC4PC. The data show that the percent occupancy decreases with decreasing protein/phospholipid ratio, indicating that a proteoliposome population sparsely populated with protein contains vesicles that lack the ability to transport diC4PC. These inactive vesicles could lack proteins altogether, e.g., liposomes such as those described in Fig. 2, or contain proteins other than those able to transport diC4PC. Assuming that the average size of a bacterial membrane protein is 50 kDa and using the data of Mimms et al. (27) to calculate the number of vesicles that we have in our preparations, we suggest that over a significant region of the dose-response curve (Fig. 3B) the entire population of reconstituted vesicles do indeed contain protein. Thus, the incomplete accessibility of the mannose space to diC4PC suggests that a fraction of the vesicles simply lack a diC4PC transporter or lack a critical concentration of membrane proteins needed for transport.

From these experiments, we conclude that even though the diC4PC uptake assay does not provide the kinetic resolution to measure fast transbilayer movement, it provides a measure of transport activity if used on proteoliposomes with a protein/phospholipid ratio in the linear range of the curve in Fig. 3B.

Although the phospholipid analog that we used in this study has the structural features of a phospholipid, it is conceivable (as with all analogs) that its particular structural features may lead to results different from those that would be obtained with natural phospholipids. To test if long-chain phospholipids behaved similarly in our reconstituted system, we tested the extent to which a long-chain phospholipid could be hydrolyzed by PLA2 treatment of liposomes and proteoliposomes. To do this, we reconstituted vesicles containing [3H]DPPC and treated them with PLA2. The level of hydrolysis in each case was normalized to the maximal hydrolysis seen in disrupted vesicles. We argued that it should be possible to hydrolyze only ∼50% of the DPPC in liposomes, whereas hydrolysis should approach 100% in transport-active vesicles.

Figure 3C shows that this is exactly the case. The limited accessibility of DPPC to PLA2 in liposomes indicates (i) that DPPC is roughly evenly distributed over the inner and outer leaflets of the liposomal membrane, (ii) that the transbilayer distribution of DPPC is static, and (iii) that products of phospholipid hydrolysis (lysophosphatidylcholine and fatty acids) do not facilitate transbilayer movement of DPPC. Furthermore, PLA2 hydrolysis of [3H]DPPC as a function of protein/phospholipid ratio has a profile similar to that seen with diC4PC (Fig. 3B). The increasing efficiency of hydrolysis seen in the proteoliposome preparations is consistent with transbilayer movement and can be explained by Fig. 3B: only some of the vesicles are capable of translocating DPPC at a low protein/phospholipid ratio, while the majority of the vesicles are transport active at a high protein/phospholipid ratio. These differences in efficiency underscore the point made above that the PLA2 hydrolysis protocol does not cause a general membrane perturbation resulting in increased transbilayer movement. We conclude that our reconstitution procedures yield proteoliposomes that are capable of facilitating the transbilayer translocation of long-chain phosphatidylcholine under conditions where liposomes are inactive. Thus our assays with diC4PC in the reconstituted vesicles reflect the behavior of long-chain phospholipids.

Effect of protein modification on transport.

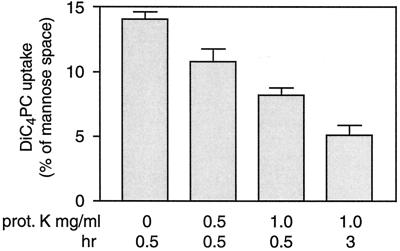

Figures 2, 3B, and 3C suggest that specific proteins are required for [3H]diC4PC transport. As an additional test of this idea, we assayed the effect of proteolysis on [3H]diC4PC transport. In initial experiments, using proteoliposomes with a high protein/phospholipid ratio, [3H]diC4PC uptake was unaffected by pretreatment of vesicles with proteinase K (data not shown). We repeated the experiment with proteoliposomes that were reconstituted to give less than maximum uptake (7.8 μg of protein/μmol of phospholipid). As shown in Fig. 4, transport of [3H]diC4PC in these preparations was inhibited by proteinase K. The amount of [3H]mannose associated with the proteoliposomes was not affected by proteolysis, indicating that the vesicles remained intact. The proportion of intravesicular volume occupied by diC4PC in the control sample was ∼14%, consistent with what would be expected at this protein/phospholipid ratio (Fig. 3B). This value dropped to 5% in the longest proteinase treatment, indicating that transport capability of ∼65% of the vesicles was abolished. The rate of transport was relatively unaffected by the treatment (data not shown), consistent with our proposal that the observed rate in the assay is not that of flip-flop. We conclude that transport activity can be completely abolished by proteolysis in a large fraction of transport-active vesicles.

FIG. 4.

DiC4PC transport in proteinase-treated proteoliposomes. The Triton extract was reconstituted to give proteoliposomes with 7.8 μg of protein/μmol of phospholipid. After reconstitution, the proteoliposomes (0.12 mg of protein/ml) were incubated with 0.5 or 1 mg of proteinase K/ml for 30 min or 1 h at room temperature. Proteolysis was stopped by addition of 3 mM PMSF, and diC4PC transport was measured within 15 min. Data are shown as the fraction of mannose space occupied by diC4PC at equilibrium, calculated from the maximum amplitude of the one-phase exponential fit of the time courses. The error bars are the standard deviation calculated from the fit and the cumulative standard deviation from protein and phospholipid determinations.

Fractionation of the Triton extract.

As a first step toward characterizing the transport component, we applied the Triton extract to an anion-exchange column and eluted bound proteins in two steps with increasing salt. The flowthrough material and the two eluted fractions were reconstituted separately at a protein/phospholipid ratio in the dynamic range of the transport assay (Fig. 3B). The data from one of two similar fractionations (Table 1) clearly show that it is possible to generate fractions of different specific activity. The unbound fraction, containing the majority (∼75%) of the total activity, was further fractionated on a cation-exchange resin (not shown). Most of the activity from the cation-exchange step was again found in the flowthrough, giving a fourfold increase in specific activity compared to the starting Triton extract. These data indicate that fractionation of the Triton extract and purification of the transporter are feasible.

TABLE 1.

DEAE fractionation of the Triton extracta

| Fraction | Protein (μg) | Sp actb (U/μg/μmol) | Total activityc (U/μmol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triton extract | 174 (10) | 3.8 (0.3) | 661 (68) |

| Unbound | 81 (0.4) | 6.2 (0.2) | 505 (32) |

| 100 mM NaCl | 15 (1.7) | 5.3 (2.1) | 78 (32) |

| 250 mM NaCl | 43 (4.4) | 2.3 (0.8) | 99 (36) |

All measurements were done in duplicates; the cumulative sample standard deviation is shown in parentheses.

Since the protein/phospholipid ratio varied between the fractions (1 to 7 μg/μmol, within the dynamic range of the assay), specific activity was calculated by normalizing activity to the ratio.

Calculated by multiplying the specific activity by total protein in the sample. The total activity recovered was 682 U, compared to 661 U loaded.

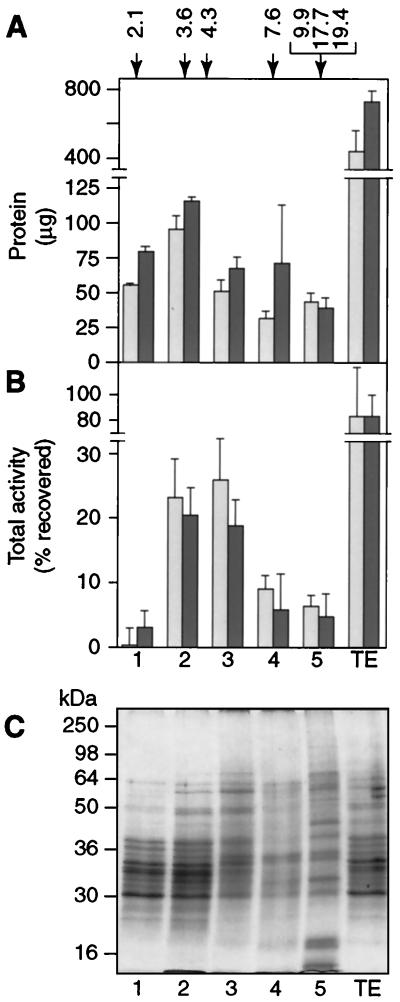

We next analyzed the Triton extract by glycerol gradient centrifugation using a 10 to 25% glycerol gradient. The data from two separate gradients are shown in Fig. 5. Vesicles reconstituted from pooled gradient fractions had protein/phospholipid ratios in the range 3 to 11 μg/μmol, within the dynamic range of the diC4PC uptake assay. Protein recovery (measured after reconstitution) was maximal in gradient pool 2 but otherwise distributed broadly across the entire gradient (Fig. 5A). However, diC4PC transport activity was markedly different in the different gradient pools. For example, a comparison of pools 1 and 3 shows that the two pools contain similar amounts of reconstituted vesicle protein (Fig. 5A) but vastly different total activities for diC4PC transport (Fig. 5B). Thus, vesicles reconstituted from pool 1 are almost completely devoid of diC4PC transport activity (Fig. 5B), while vesicles reconstituted from pool 3 are greatly enriched in transport activity. A one-dimensional Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE profile of proteins (Fig. 5C) shows that both pools contain complex mixtures of proteins with clear differences between them. This result reinforces our conclusion that not all proteins are capable of supporting diC4PC transport and that transport is due to specific proteins. Since most of the transport activity (∼75% [Fig. 5B]) is recovered in pools 2 and 3, we further conclude that the proteins responsible for diC4PC transport sediment in the range of 3.6S to 4.3S.

FIG. 5.

Glycerol gradient fractionation of the Triton extract. The Triton extract was loaded onto a 10 to 25% glycerol gradient and centrifuged for 20 h at ∼165,000 × g. Fractions were collected from the top and pooled as described in Materials and Methods to yield pools 1 to 5. Pools were dialyzed to remove glycerol and reconstituted as before, using inulin as a content marker. Results from two separate gradients are shown. (A) Total protein in reconstituted pools 1 to 5 and the Triton extract loaded onto the gradient. Extents of protein recovery from the two gradients were ∼63 and 51%, respectively. Numbers at the top show the relative positions and sedimentation values of standards run on a parallel gradient. (B) Total activity in pools. Extents of total activity recovered from the gradients were 77 and 66%. (C) SDS-PAGE of pools 1 to 5 from the first gradient (lighter bars) (lanes 1 to 5) and the Triton extract (lane TE). Approximately 20 μg of delipidated samples were loaded onto a 12% acrylamide gel. The picture shows Coomassie blue staining of the gel. Numbers on the left indicate the relative positions of molecular mass markers.

DISCUSSION

Previous reports on phospholipid transbilayer movement in bacterial cytoplasmic membranes have been directed toward characterization of the activity in membrane vesicles or intact cells, using fluorescent phospholipid analogs and naturally occurring phospholipids (11–13, 20, 32). Our objective was to use biochemical methods to substantiate the hypothesis that membrane proteins are responsible for transbilayer movement in bacterial membranes and to test, in particular, if specific proteins are involved. The goal was to establish a reconstitution system that could be used for eventual identification of the transporter(s). Using this approach, we found that the transport activity is associated with the detergent extract of the bacterial membrane, not the lipid extract, and is inhibited by proteolysis, confirming that proteins play a direct or indirect role in phospholipid translocation. Since we were able to generate protein-rich fractions essentially devoid of transport activity (pool 1 of the glycerol gradient analysis shown in Fig. 5), we further conclude that transport is not a general property of membrane proteins. In the same analysis (Fig. 5), we identified a fraction containing proteins sedimenting at ∼4S that was greatly enriched in transport activity. Simple anion-exchange fractionation of the detergent extract also resulted in an enrichment of transport activity, reaffirming that specific proteins must be required for transport and indicating that the reconstitution system could be used for identification of the transporter.

The measurement of transport activity is perhaps the major obstacle in the study of transbilayer movement of phospholipids. Several different assay systems have been reported (for a review, see reference 26), based on the use of phospholipid analogs as transport reporters. The analogs have increased water solubility that allows for fast insertion into and removal from membranes; assays based on natural phospholipids are generally much slower (13, 15, 32, 38). The fluorescent assay that we used previously to study phospholipid flip-flop in B. megaterium membrane vesicles was impractical when applied to the reconstituted proteoliposomes. We therefore employed an assay based on [3H]diC4PC that had been previously used to measure phospholipid flip-flop in rat liver endoplasmic reticulum vesicles (3). This analog is sufficiently water soluble to allow for easy assay of transport from the extravesicular space, through the bilayer, into the vesicle interior. Even though this analog has short acyl chains, it contains the main structural features of a phospholipid. Importantly, we were able to demonstrate a clear correlation between transport of diC4PC and flip-flop of long-chain phospholipid. This correlation mitigates uncertainties that stem from our choice of diC4PC as a transport reporter.

Using the diC4PC assay, we confirmed that phospholipid flip-flop in bacterial cytoplasmic membranes is bidirectional and not dependent on supplied energy. We then tested if transport could be reconstituted in proteoliposomes. Initial experiments in which we reconstituted vesicles from octylglucoside or cholate extracts by dialysis showed that diC4PC was transported across lipid-only vesicles (data not shown). Since we and others have previously shown that lipid vesicles prepared by means other than detergent reconstitution are incapable of supporting rapid lipid translocation, the effect that we observed with the octylglucoside and cholate-based preparations is likely due to small amounts of residual detergent or trace contaminants in the detergent. Similar results have been previously reported in which, for example, phosphatidylcholine liposomes reconstituted by dialysis of a cholate extract were shown to be able to translocate DPPC (19). To explore other reconstitution possibilities, we used extracts prepared with Triton X-100 and reconstituted vesicles according to procedures described by Lévy et al. (21). This approach resulted in a reliable and credible reconstitution. We were thus able to show that the Triton extract of the membrane contained a component(s) that accelerated the transbilayer movement of diC4PC.

Analyses of diC4PC transport in proteoliposomes containing different ratios of protein to phospholipid revealed that the rate of transport was not dependent on the concentration of the active component. A likely explanation for this is that because of the high water-solubility of this analog, the rate-limiting step in the assay is the association of the analog with the bilayer rather than transbilayer movement. Despite this kinetic limitation, the amount of diC4PC transported at equilibrium was clearly dependent on the protein/phospholipid ratio, showing that upon increasing dilution of the detergent extract into egg PC liposomes, a decreasing fraction of the liposomes were active in diC4PC transport. This is consistent with the proposal that a specific protein(s) is responsible for transport. Sufficient dilution of the detergent extract to give vesicle populations with less than one transporter per vesicle thus resulted in adequate assay resolution.

Using these dilute reconstitution conditions, we could detect inhibition of transport by proteolysis. Previous data from B. megaterium membrane vesicles showed a twofold decrease in rate of transport upon proteolysis of the vesicles (11), but data from protease treatment of E. coli inner membrane vesicles showed that transport activity was unaffected (12). The observed noneffect with the E. coli preparation is most likely because the assay used would not have allowed for detection of partial inhibition. The rather harsh proteolysis treatment that we used here did not completely abolish the diC4PC uptake since about one-third of the vesicles remained transport active. This protease-resistant activity in the minority of the vesicles could represent a distinct or differently oriented transporter. Consistent with this, we found no effect of protease treatment on vesicles reconstituted at high protein/phospholipid ratios corresponding to maximal diC4PC uptake; this can readily be explained only by suggesting that under these reconstitution conditions, all vesicles contain at least one protease-resistant transporter.

Eucaryotic MDR transporters have been implicated in lipid transport, and the idea that their bacterial homologs (35, 40) have similar activity is appealing. Of special interest are the MsbA protein in E. coli (30) and the LmrA protein from Lactococcus lactis. These proteins are both Mdr homologs, and recent work implicates them in transbilayer lipid translocation (22, 45). MsbA is an inner membrane, ATP-binding protein that is essential for growth (30). Cells depleted of MsbA accumulate core lipid A and glycerophospholipids in the inner membrane fraction on a sucrose gradient, suggesting that the protein has a role in lipid transport to the outer membrane (45). Whether MsbA is able to transport both core lipid A as well as phospholipids as the authors suggest is unclear, and reconstitution studies of the type described in this paper should help to resolve this issue.

The LmrA protein presents a somewhat different picture. Analyses of LmrA-containing proteoliposomes showed that under conditions where LmrA was able to transport drugs in an ATP-dependent fashion (22), it was also apparently able to translocate a fluorescent analog of phosphatidylethanolamine, 1-myristoyl-2-[6-[(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino] caproyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylethanolamine (1-myristoyl-2-C6-NBD-PE). Some ATP-independent transport of other fluorescent phospholipids (bearing a short C6 acyl chain modified by the fluorescent NBD group) was seen, but only the transport of C6-NBD-PE was stimulated by ATP. Surprisingly, C6-NBD-PE did not accumulate strongly in the inner leaflet of the proteoliposomes, as would be expected for a vectorial transport process. These data, together with the results for MsbA, suggest that Mdr homologs may play a role in transbilayer translocation of lipids in bacteria. However, the ATP dependence and the vectorial nature of transport catalyzed by Mdr proteins contrast with the ATP-independent, bidirectional transport activity that we describe here. Thus, while Mdr proteins and their homologs may well act to transport certain lipid intermediates unidirectionally across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane, it is unlikely that they catalyze bidirectional, energy-independent translocation of phospholipids in biogenic membranes.

Several pore-forming antimicrobial peptides have been shown to increase the transbilayer movement of fluorescent phospholipids (9, 24, 25, 28). Various models have been proposed for the mechanism of their action (for a review, see reference 37), including a peptide-induced continuum between the outer and inner monolayer that would allow lipids to diffuse between the two leaflets. Because of the energy-independent, bidirectional characteristics of transbilayer movement in bacterial membranes, this model represents an attractive hypothesis for the mechanism. These peptides are, however, unlikely candidates for the bacterial phospholipid flippase because of the leakage of ions and small water-soluble molecules that accompanies their action. Nevertheless, having a reliable reconstitution system now allows these models to be examined while affording the promise of methodology for the direct purification of a phospholipid translocator.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Wylie Nichols for valuable discussions on reconstitution procedures, John Silvius, Tim Heath, and Mark Krebs for advice, Ross Inman and Maria Schnos for electron micrographs, and Jolanta Vidugiriene and Dave Rancour for comments on the manuscript. A.K.M. acknowledges Bob Dylan for stimulation, and S.H. acknowledges technical support provided by Sigtryggur Baldursson and Una Sigtryggsdottir.

This work was supported by a grant from the American Heart Association of Wisconsin (97-GS-67) and NIH grant GM55427. S.H. was supported in part by a Peterson fellowship in the Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassé F, Stout J G, Sims P J, Wiedmer T. Isolation of an erythrocyte membrane protein that mediates Ca2+-dependent transbilayer movement of phospholipid. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17205–17210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell R M, Mavis R D, Osborn M J, Vagelos P R. Enzymes of phospholipid metabolism: localization in the cytoplasmic and outer membrane of the cell envelope of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;249:628–635. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(71)90144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop W R, Bell R M. Assembly of the endoplasmic reticulum phospholipid bilayer: the phosphatidylcholine transporter. Cell. 1985;42:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buton X, Morrot G, Fellmann P, Seigneuret M. Ultrafast glycerophospholipid-selective transbilayer motion mediated by a protein in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;249:636–642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daleke D L, Huestis W H. Incorporation and translocation of aminophospholipids in human erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5406–5416. doi: 10.1021/bi00341a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devaux P F. Lipid transmembrane asymmetry and flip-flop in biological membranes and in lipid bilayers. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:489–494. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolis D, Moreau C, Zachowski A, Devaux P F. Aminophospholipid translocase and proteins involved in transmembrane phospholipid traffic. Biophys Chem. 1997;68:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(97)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fattal E, Nir S, Parente R A, Szoka F C., Jr Pore-forming peptides induce rapid phospholipid flip-flop in membranes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6721–6731. doi: 10.1021/bi00187a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta C M, Radhakrishnan R, Khorana H G. Glycerophospholipid synthesis: improved general method and new analogs containing photoactivable groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:4315–4319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hrafnsdóttir S, Nichols J W, Menon A K. Transbilayer movement of fluorescent phospholipids in Bacillus megaterium membrane vesicles. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4969–4978. doi: 10.1021/bi962513h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huijbregts R P H, de Kroon A I P M, de Kruijff B. Rapid transmembrane movement of C6-NBD-labeled phospholipids across the inner membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1280:41–50. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huijbregts R P H, de Kroon A I P M, de Kruijff B. Rapid transmembrane movement of newly synthesized phosphatidylethanolamine across the inner membrane of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18936–18942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huijbregts R P H, de Kroon A I P M, de Kruijff B. Topology and transport of membrane lipids in bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1469:43–61. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(99)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutson J L, Higgins J A. Asymmetric synthesis followed by transmembrane movement of phosphatidylethanolamine in rat liver endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;687:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kates M. Techniques of lipidology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konings W N, Bisschop A, Veenhuis M, Vermeulen C A. New procedure for the isolation of membrane vesicles of Bacillus subtilis and an electron microscopy study of their ultrastructure. J Bacteriol. 1973;116:1456–1465. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.3.1456-1465.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornberg R D, McConnell H M. Inside-outside transitions of phospholipids in vesicle membranes. Biochemistry. 1971;10:1111–1120. doi: 10.1021/bi00783a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer R M, Hasselbach H, Semenza G. Rapid transmembrane movement of phosphatidylcholine in small unilamellar lipid vesicles formed by detergent removal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;643:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langley K E, Kennedy E P. Energetics of rapid transmembrane movement and of compositional asymmetry of phosphatidylethanolamine in membranes of Bacillus megaterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6245–6249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lévy D, Bluzat A, Seigneuret M, Rigaud J-L. A systematic study of liposome reconstitution involving Bio-Bead-mediated Triton X-100 removal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1025:179–190. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margolles A, Putman M, van Veen H, Konings W N. The purified and functionally reconstituted multidrug transporter LmrA of Lactococcus lactis mediates the transbilayer movement of specific fluorescent phospholipids. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16298–16306. doi: 10.1021/bi990855s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin O C, Pagano R E. Transbilayer movement of fluorescent analogs of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine at the plasma membrane of cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5890–5898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuzaki K, Yoneyama S, Murase O, Miyajima K. Transbilayer transport of ions and lipids coupled with mastroparan X translocation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8450–8456. doi: 10.1021/bi960342a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuzaki K, Murase O, Fujii N, Miyajima K. An antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, induces rapid flip-flop of phospholipids couples with pore formation and peptide translocation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11361–11368. doi: 10.1021/bi960016v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menon A K. Flippases. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mimms L T, Zampighi G, Nozaki Y, Tanford C, Reynolds J A. Phospholipid vesicle formation and transmembrane protein incorporation using octyl glucoside. Biochemistry. 1981;20:833–840. doi: 10.1021/bi00507a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moll G N, Konings W N, Driessen A J M. The lantibiotic nisin induces transmembrane movement of a fluorescent phospholipid. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6565–6570. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6565-6570.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson P H, Lennarz W J. Studies on the membranes of bacilli. I. Phospholipid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1062–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polissi A, Georgopoulos C. Mutational analysis and properties of the msbA gene of Escherichia coli, coding for an essential ABC family transporter. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1221–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raggers R J, van Helvoort A, Evers R, van Meer G. The human multidrug resistance protein MRP1 translocates sphingolipid analogs across the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:415–422. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman J E, Kennedy E P. Rapid transmembrane movement of newly synthesizes phospholipids during membrane assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:1821–1825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.5.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouser G, Fleischer S, Yamamoto A. Two dimensional thin layer chromatographic separation of polar lipids and determination of phospholipids by phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids. 1970;5:494–496. doi: 10.1007/BF02531316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruetz S, Gros P. Phosphatidylcholine translocase: a physiological role for the mdr2 gene. Cell. 1994;77:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saier M H, Jr, Paulsen I T, Sliwinski M K, Pao S S, Skurray R A, Nikaido H. Evolutionary origins of multidrug and drug-specific efflux pumps in bacteria. FASEB J. 1998;12:265–274. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seigneuret M, Devaux P F. ATP-dependent asymmetric distribution of spin-labeled phospholipids in the erythrocyte membrane: relation to shape changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3751–3755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shai Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by α-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith A J, Timmermans-Hereijgers J L P M, Roelofsen B, Wirtz K W A, van Blitterswijk W J, Smit J J M, Schinkel A H, Borst P. The human MDR3 P-glycoprotein promotes translocation of phosphatidylcholine through the plasma membrane of fibroblasts from transgenic mice. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Helvoort A, Smith A J, Sprong H, Fritzsche I, Schinkel A H, Borst P, van Meer G. MDR1 P-glycoprotein is a lipid translocase of broad specificity, while MDR3 P-glycoprotein specifically translocates phosphatidylcholine. Cell. 1996;87:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Veen H, Konings W N. The ABC family of multidrug transporters in microorganisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wessel D, Flügge U I. A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem. 1984;138:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White D A, Albright F R, Lennarz W J, Schaitman C A. Distribution of phospholipid-synthesizing enzymes in the wall and membrane subfractions of the envelope of Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;249:636–642. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(71)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zachowski A. Phospholipids in animal eukaryotic membranes: transverse asymmetry and movement. Biochem J. 1993;294:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2940001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Q, Zhao J, Stout J G, Luhm R A, Wiedmer T, Sims P J. Molecular cloning of human plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18240–18244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Z, White K A, Polissi A, Georgopoulos C, Raetz C R H. Function of Escherichia coli MsbA, and essential ABC family transporter, in lipid A and phospholipid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12466–12475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]