Abstract

Carbamoyl phosphate (CP) is an intermediate in pyrimidine and arginine biosynthesis. Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (CPS) contains a small amidotransferase subunit (GLN) that hydrolyzes glutamine and transfers ammonia to the large synthetase subunit (SYN), where CP biosynthesis occurs in the presence of ATP and CO2. Lactobacillus plantarum, a lactic acid bacterium, harbors a pyrimidine-inhibited CPS (CPS-P; Elagöz et al., Gene 182:37–43, 1996) and an arginine-repressed CPS (CPS-A). Sequencing has shown that CPS-A is encoded by carA (GLN) and carB (SYN). Transcriptional studies have demonstrated that carB is transcribed both monocistronically and in the carAB arginine-repressed operon. CP biosynthesis in L. plantarum was studied with three mutants (ΔCPS-P, ΔCPS-A, and double deletion). In the absence of both CPSs, auxotrophy for pyrimidines and arginine was observed. CPS-P produced enough CP for both pathways. In CO2-enriched air but not in ordinary air, CPS-A provided CP only for arginine biosynthesis. Therefore, the uracil sensitivity observed in prototrophic wild-type L. plantarum without CO2 enrichment may be due to the low affinity of CPS-A for its substrate CO2 or to regulation of the CP pool by the cellular CO2/bicarbonate level.

Lactobacilli are fastidious gram-positive bacteria with complex nutritional requirements resulting from numerous genetic lesions in metabolic pathways which often revert to prototrophy (24). Natural auxotrophies involved in carbamoyl phosphate (CP) biosynthesis were shown to be reversed in most cases by incubating lactobacilli in CO2-enriched air (2; F. Bringel, unpublished data). Metabolically, lactobacilli are at the threshold of the transition from anaerobic to aerobic life (16); Lactobacillus plantarum grows in aerobiosis but prefers microaerobiosis or increased CO2 concentration.

The arginine and pyrimidine biosynthetic pathways share CP as a common precursor. CP synthetase (CPS) catalyzes the synthesis of CP from bicarbonate, glutamine, and two molecules of ATP via a complex reaction mechanism that leads to several unstable intermediates. The X-ray crystal structure of CPS in Escherichia coli has revealed the location of three separate active sites connected by two molecular tunnels that run through the interior of the protein (33) and that would allow substrate channeling and subsequent protection of the reactive intermediates (reviewed in reference 22). Furthermore, CP biosynthesis in Pyrococcus abyssi also includes metabolic channeling, a process whereby the product of one enzyme is directly transferred to the next enzyme in the pathway without being released in the bulk solvent; CPS may interact with two CP-utilizing enzymes in the pyrimidine (aspartate carbamoyltransferase) and the arginine (anabolic ornithine carbamoyltransferase) biosynthetic pathways (29). The heterodimeric CPS enzyme is composed of a small subunit (GLN) which functions as a glutamine amidotransferase and a large synthetase subunit (SYN) that fulfills the other catalytic properties (for a review, see reference 4). Allosteric regulation via the carboxy-terminal part of SYN subunit by effectors which are intermediates in the pyrimidine, arginine, and purine pathways has been identified for some prokaryotic CPSs (4) but not for others (27, 38).

Prokaryotic CPSs are encoded by two genes, commonly named carA and carB, which are organized as an operon with the gene order carAB. Prokaryotes harbor a single CPS regulated by both the pyrimidines and arginine levels in the cell (E. coli); alternatively, a single CPS regulated by the pyrimidines and CP is also produced by arginine degradation (Lactobacillus leichmannii and possibly Lactococcus lactis and Enterococcus faecalis), or a set of two CPSs specifically pyrimidine or arginine regulated is produced (Bacillaceae). In L. plantarum, earlier studies suggested the presence of two CPSs, CPS-P, and CPS-A. CPS-P is part of the pyr operon regulated by transcriptional attenuation under the control of the regulator PyrR (9, 10). The existence of L. plantarum CPS-A was suspected but not proven. Partial cloning of a carA-like sequence contiguous to the arginine-repressed biosynthetic genes (3) suggested the existence of CPS-A in L. plantarum. Furthermore, Lyman et al. observed in 1947 that L. plantarum (formerly named L. arabinosus) grew in the presence of uracil if incubated in air enriched with CO2. This CO2-conditional uracil sensitivity was confirmed in our laboratory. These data argue for the presence of a CPS-A in L. plantarum which is not inhibited by uracil and not functional in cells grown with ordinary air unless supplemented with CO2. In this study, we demonstrate that L. plantarum indeed harbors two functional CPSs. In contrast to other microorganisms, wild-type L. plantarum CP synthesis is dependent on higher CO2 requirements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gram-positive bacteria strains and culture conditions.

L. plantarum CCM-1904 was grown on MRS medium (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with arginine (500 μg/ml), uracil (100 μg/ml), and erythromycin (2.5 μg/ml) when necessary. Nutritional requirements were tested at 30°C on agar plates of defined medium DLA (3) supplemented with 50 μg of arginine or uracil per ml in aerobiosis, anaerobiosis, or CO2-enriched air. Aerobiosis was obtained by incubation in ordinary air (PO2, 21%; PCO2, 0.01%) with vigorous aeration when liquid cultures were performed. Anaerobiosis was obtained in a hermetically closed jar either with GENbox anaer or GazPak CO2 + H2 (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l'Etoile, France), providing less than 1% residual PO2 and approximately 20 or 4% PCO2 respectively. CO2-enriched aerobiosis was controlled either using a water-jacketed CH/P incubator (Forma Scientific) calibrated at 4 or 20% PCO2 or in a hermetically closed jar with GENbox CO2 (bioMérieux) providing 3 to 6% PCO2.

Bacillus subtilis MI112, equivalent to ATCC 33712 (argGH Leu− Thr− recE HsdR−/M−), was used for cloning plasmid pGID023Δcar on Luria-Bertani plates supplemented with erythromycin and lincomycin (1 and 25 μg/ml, respectively).

Nucleic acid techniques.

L. plantarum, B. subtilis, and E. coli DNA transformation and nucleic acid preparations were performed as previously described (3). RNA extractions were performed according to the Lactobacillus bulgaricus hot phenol protocol (17) adapted to L. plantarum by adding β-mercaptoethanol (1.9 mM, final concentration) and increasing lysozyme 30-fold and sodium dodecyl sulfate 10-fold (9). Nucleic acid hybrids on Hybond positively charged nylon membranes (Amersham) were detected with a nonradioactive digoxigenin DNA labeling and detection kit using the alkaline phosphatase chemiluminescent substrate CDP-Star (Boehringer Mannheim). Routine PCR amplifications were done with the Sigma Taq DNA polymerase. For cloning purposes, higher-fidelity amplifications were obtained with the native Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). DNA primers were 32P end labeled with the T4 polynucleotide kinase (30), and primer extension was performed as previously described (13). DNA sequencing was done with a Thermo Sequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Construction of the L. plantarum ΔCPS mutants using pGID023-derived plasmids.

The 8.2-kb cloning vector pGID023 is stable in E. coli and unstable in gram-positive bacteria under nonselective conditions. Mutagenesis by allelic replacement is therefore possible in L. plantarum by two successive homologous recombinations: an insertion followed by excision (14). Erythromycin resistance was the selective marker in E. coli and in gram-positive bacteria.

(i) FB331.

Complete deletion of the two genes pyrAa and pyrAb, coding for the two subunits of CPS-P and part of the pyrRBCAaAbDFE operon (10), was designed to prevent mutations in the adjacent pyr genes.

Plasmid pFB331, which harbored the ΔCPS-P mutation, was constructed. A 1.2-kb fragment obtained from the assembly of two 0.6-kb PCR products corresponding to ΔpyrAaAb deletion borders was inserted into pGID023. First, left (1.1-kb) and right (1.9-kb) fragments were PCR amplified from the L. plantarum genomic DNA using the primers sets P1 (5′-ATCCTGGTCAAACAGCGAAG-3′)-P2 (5′-GGGTGTCCTGATTCATGCTTGCGTTTCCTTTCCATATG-3′) and P3 (5′-ACGCAAGCATGAATCAGGACACCCGCCGATAAGC-3′)-P4 (5′-CCCCGCAATCACTTCGG-3′), respectively. Second, the left and right fragments were joined using the 24-nucleotide (nt)-long complementarity of P2 and P3 incorporated primers. The 3-kb joined fragment was PCR amplified with primers P1 and P4, restricted with enzymes HpaI and PvuII, and ligated with the linearized blunt-end SmaI pGID023 vector. E. coli was electroporated with the ligation mixture, and plasmid pFB331 (9.4 kb) was obtained.

Plasmid pFB331 harboring the CPS-P deletion was electroporated into L. plantarum. Stable erythromycin-resistant transformants were selected for plasmid pFB331 integration at the pyr locus. After growth without erythromycin, 9 of 22 erythromycin-sensitive excisants were unable to grow without arginine and pyrimidines. To confirm the deletion of the CPS-P genes in these excisants, their genomic DNA was tested by Southern-type hybridization with a probe hybridizing the upstream pyrC region of the deletion. With NcoI digests of genomic DNA, we detected a 3.4-kb band in the wild-type strain and a 2.9-kb band in the excisants, demonstrating the presence of a mutation in the tested excisants (data not shown). Excisant FB331 harbored the expected pyrAaAb deletion as checked by sequencing (data not shown).

(ii) FB335.

CPS-A encoded by the carAB genes was inactivated by removing the majority of CarA and 16% of the beginning of CarB. This was done to avoid deregulation of the contiguous and divergently transcribed arg cluster since the beginning of carA harbors a putative ARG box suggested to be part of the argC operator (3). Therefore, in this ΔCPS-A mutant, a fusion protein of the first 27 amino acids (aa) of CarA and the CarB C-terminal part will be synthesized. To avoid translation of the remaining carB gene, two stop codons in each frame were added at the junctions of the deletion.

Plasmid pGID023Δcar contains vector pGID023 with a 1-kb insert composed of two 0.5-kb PCR-amplified fragments corresponding to the Δcar deletion left (primers P5 [5′-CATTTATCTAGAGCTGCCACCGTCTTTAATGCC-3′] and P6 [5′-CCGGATATTATTAGTTATTACTTATTACCCCGCAACCTCTAGCTGGC-3′]) and right borders (primers P7 [5′-GCGGGGTAATAAGTAATAACTAATAATATCCGGTCATTGTTCGTCC-3′] and P8 [5′-CATTTACTGCAGCGTGACTGGATTCTTGATCTC-3′]). The two fragments were joined using P6 and P7 complementarity, and the joint fragment was amplified with primers P5 and P8 (which harbored PstI and XbaI restriction sites, respectively). The cloning vector pGID023 was PstI and XbaI linearized and ligated with the digested 1-kb PCR fragment. We did not succeed in cloning this construct in E. coli (see Discussion) but had no problem in B. subtilis, which is closely related to L. plantarum.

Plasmid pGID023Δcar was introduced by transformation in the L. plantarum wild-type strain, and erythromycin-resistant transformants were selected. After testing for plasmid marker loss, we obtained 13 erythromycin-sensitive excisants that either harbored the CPS-A deletion or reverted to the wild-type allele. To discriminate between these two types of excisants, Southern-type hybridization was done with a probe hybridizing with the remaining carB gene. The probe hybridized with genomic DNA digested with either Nsp(7524)I or HindIII, and a band of 4 or 3 kb, respectively, was detected with the wild-type CCM1904, whereas a band of 2.6 or 1.6 kb, respectively, was obtained with four excisants (data not shown). CPS-A deletion was confirmed in excisant FB335 using PCR and sequencing (data not shown).

(iii) HN217.

To construct an L. plantarum strain with no functional CPS, plasmid pGID023Δcar harboring the CPS-A deletion was introduced by electroporation in FB331, a strain having the CPS-P deleted. After the two steps of homologous recombination, pGID023Δcar integration at the car locus, and excision of the vector, erythromycin-sensitive excisants were analyzed as described for FB335. Strain HN217 was an erythromycin-sensitive excisant deleted of both CPS-A and CPS-P as demonstrated by Southern-type hybridization, PCR amplifications, and sequencing (data not shown).

Computer analysis.

Database searches and sequence analyses were performed using the Genetics Computer Group package from the University of Wisconsin (6) and the advanced BLAST program (1). The ClustalX program (35) was used for protein alignments.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data reported here have been submitted to DDB/EMBL/GenBank as an update of accession number X99978.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequencing strategy without cloning.

CPSs are generally encoded by two carA and carB clustered genes (see Introduction). We cloned part of carA while cloning the argF gene by complementation of a B. subtilis argF mutant since argF is 4.5 kb distant from carA (3). Our attempts to clone the L. plantarum car genes by functional complementation in a CPS- deficient E. coli (strain C600ΔcarB8) were unsuccessful (see discussion of arginine repression studies for possible explanations). Thus, PCR without cloning was chosen to complete the carA sequence and find carB (Fig. 1). We added 3,954 bp to the 7,226-bp arg cluster sequence previously published.

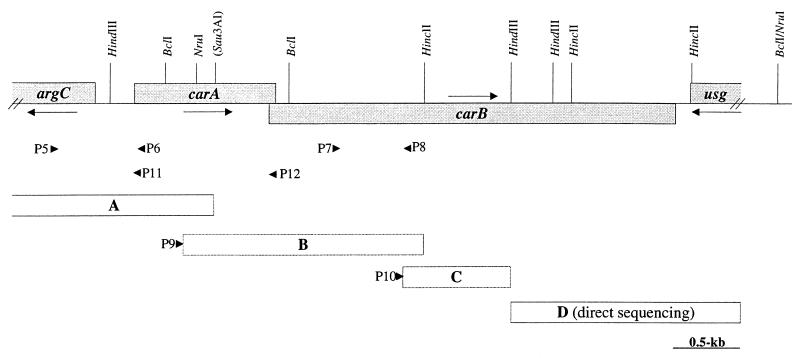

FIG. 1.

Sequencing strategy of the L. plantarum carAB operon. Relevant restriction sites are indicated on the top. The arrows indicate primer orientations and localizations. Primers P6 and P7 define the ends of the ΔCPS-A deletion constructed in strains FB335 and HN217. Steps in our sequencing strategy are marked with capital letters in rectangles as follows. Region A is part of a previously sequenced 7.2-kb fragment (3). Segment B, a 1.8-kb fragment, was PCR amplified with a universal primer (M13Rev) and the P9 (5′-CAAGTACTAACGGCTACC-3′) internal carA primer deduced from region A. The template was a ligation mixture of the SmaI-digested pGID023 vector (14) ligated with a complete HincII digest of the L. plantarum genomic DNA. Fragment C was PCR amplified with a universal primer (M13Rev) and the P10 primer (5′-AGATCAAGAATCCAGTCACGC-3′) deduced from segment B. The template was a ligation mixture of the HindIII-digested pUC19 vector (26) ligated with a complete HindIII digest of the L. plantarum DNA. Region D was sequenced on one strand directly from a 4-kb gel-purified BclI digestion of L. plantarum DNA, PCR amplified, and subsequently sequenced on the complementary strand.

Sequence analysis. (i) GLN subunit.

Divergently oriented with respect to the arg cluster, an open reading frame (ORF) of 355 aa shares more than 40% identity with the GLN small subunit of different bacterial CPSs (B. caldolyticus, B. stearothermophilus, B. subtilis, and E. coli; CPS-P of L. plantarum) and corresponds to the carA gene. Important residues were identified for E. coli GLN (Cys269, His353, Glu355, and His312) by biochemical studies, site-directed mutagenesis, and X-ray crystal structure analysis (33) and found in the L. plantarum GLN subunit (Cys240, His226, Glu228, and His284).

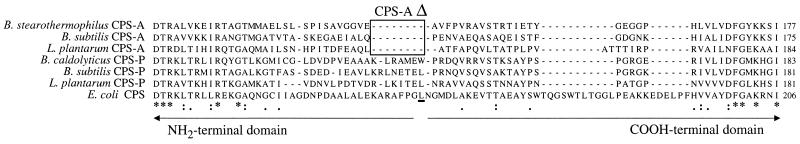

The pyrimidine-regulated GLN subunits have about 10 aa more than the gram-positive bacteria arginine-regulated GLN subunits. To investigate the putative localization of these missing amino acids, gram-positive bacteria GLN subunit sequences of CPS-A (B. stearothermophilus, 354 aa; B. subtilis, 353 aa; L. plantarum, 355 aa) were aligned with the 364-aa-long sequences of CPS-P (B. caldolyticus, B. subtilis, and L. plantarum). As a reference, the single E. coli CPS (382 aa) regulated by both the arginine and the pyrimidines was also aligned. As seen in Fig. 2, a stretch of 7 to 8 aa that is not conserved in CPS-P is absent only in CPS-A. When placed on the E. coli CPS quaternary structure (33), this segment, named CPS-AΔ (Fig. 2), was at the hinge of the NH2- and catalytic COOH-terminal subdomains of the bilobal GLN subunit. When other prokaryotic CPS-A sequences are available, the significance of this proposed CPS-A specific deletion can be tested.

FIG. 2.

Prokaryote CPS-A and CPS-P comparisons of GLN subunit subdomain junctions. The framed 8-aa-long deletion (CPS-AΔ) was found when comparing the smaller GLN subunits of the gram-positive bacteria CPS-A with the larger gram-positive CPS-P and the single E. coli CPS. Numbers on the right indicate the studied sequence positions within the different whole GLN subunits. The underlined E. coli Leu153 marks the border between the bilobal GLN subunit subdomains: the NH2-terminal and catalytic COOH-terminal subdomains (33). Underneath the sequences, three characters (*, :, and .) indicate positions which harbor a single conserved residue having fully, strongly, and weakly conserved groups, respectively, as defined by the ClustalX multiple sequence alignment program (35).

(ii) SYN subunit.

The second ORF encodes 1,020 aa sharing significant identity with the SYN large subunit of several bacterial CPSs (L. plantarum CPS-P, 62%; B. caldolyticus, 59%; L. lactis, 59%; E. coli, 48%). Therefore, this ORF was named carB. The 7-nt overlap of the GLN and SYN subunits (Fig. 3) suggests stoichiometric translational coupling. E. coli CPS crystal structure studies revealed an internal tunnel mediating substrate channeling; 21 conserved residues lining this tunnel (34) were also found in L. plantarum CPS-A (data not shown). The L. plantarum SYN subunit is the smallest of the arginine-specific SYN subunits described so far. Like CPS-A in B. subtilis (1,027 aa [27]) and B. stearothermophilus (1,047 aa [38]), the L. plantarum CPS-A SYN subunit had a C-terminal truncation which was not observed in the five known gram-positive bacterial CPS-P: L. plantarum (1,058 aa), L. lactis (1,064 aa), B. caldolyticus (1,065 aa), B. subtilis (1,071 aa), and B. stearothermophilus (1,064 aa) (protein alignments not shown). Yang et al. (38) correlated the difference in size (average of 34 aa) between CPS-A and CPS-P with the presence of the pyrimidine effector binding site in the carboxy terminus of CPS-P. So, is L. plantarum CPS-A, like other gram-positive bacteria CPS-A, unable to bind allosteric ligands?

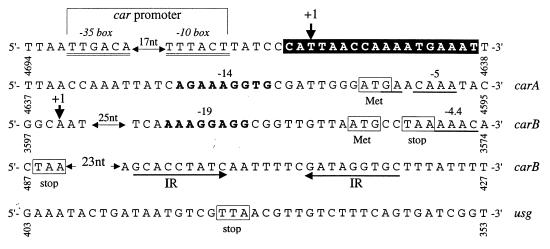

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional and translational elements of the L. plantarum carAB operon. Numbers correspond to the citrulline biosynthetic cluster sequence (accession number X99978). The +1 labels indicate transcriptional start sites, which are marked with thick arrows. Residues involved in the carA promoter are double underlined. A B. subtilis ARG box-like sequence (23) around the +1 site is indicated with a blackened box. The proposed translational initiation and stop codons are indicated with boxes for the CPS-A GLN (carA gene) and SYN (carB gene) subunits and for the adjacent divergently oriented ORF. Good putative ribosome binding sites which exhibit complementarity to the L. plantarum 3′-terminal and 5′-terminal 16S rRNA sequence (EMBL accession number M58827) are boldface and underlined, respectively. The free energy (ΔG [36]) characterizes the base pairing between the different RNAs. Two arrows indicate the inversely repeated (IR) sequences preceding a row of T residues, which suggests a transcriptional rho-independent terminator (estimated ΔG of −12 kcal/mol for IR pairing).

(iii) Third ORF.

Another gene was found with the opposite orientation of carB and located 106 bp after the carB stop codon. This ORF encodes a 124-aa protein truncated at its N terminus that shared no similarity with known proteins in the databank. Therefore, we designated this gene usg (upstream gene of the citrulline biosynthetic cluster).

Transcription studies and arginine repression. (i) carB is cotranscribed with carA and transcribed monocistronically.

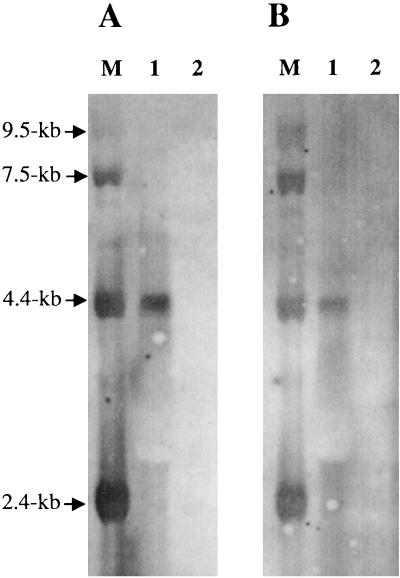

mRNAs extracted from L. plantarum grown on DLA without arginine were probed with a carA fragment. A unique 4.2-kb transcript was detected (Fig. 4A), demonstrating cotranscription of the carAB genes. The carA transcription initiation site was localized using primer extension (Fig. 5), and the corresponding promoter was found (Fig. 3) by similarity with the Lactobacillus consensus sequence (−35 box [TTgaca] and −10 box [TAtAaT] 17 nt apart) (28). Since the carB gene is transcribed monocistronically in P. aeruginosa and in L. lactis (18, 20), independent carB transcription was assessed in L. plantarum using a specific carB probe in Northern hybridizations. Indeed, we detected a 4.2-kb transcript (Fig. 4B) but not the 3.1-kb band corresponding to the predicted carB transcript. Nonetheless, carB may be weakly transcribed. Therefore, primer extension experiments were done on mRNAs extracted from cells grown in the absence of arginine, and a transcription start site was identified (Fig. 5) with two different primers (data not shown). We concluded that carB is independently transcribed. However, in the vicinity of the transcription start site, no promoter-like sequence could be found. Moreover, as no carB transcript was revealed by Northern blots, the carB mRNA is probably not abundant. This could result from weak transcription in the tested conditions or carB mRNA unstability.

FIG. 4.

Transcription studies and arginine repression with Northern hybridizations using mRNAs extracted from L. plantarum grown on defined medium without and with arginine (tracks 1 and 2, respectively) and probed with a carA (A) or carB (B) probe. The size of the transcript was determined using the Gibco BRL 0.24- to 9.5-kb RNA ladder (track M), which was revealed by hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled λ DNA.

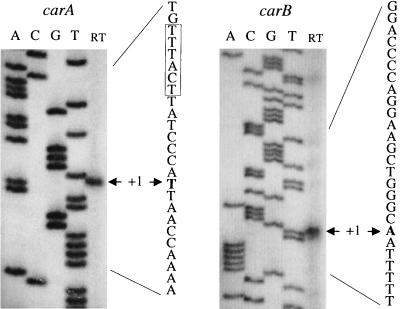

FIG. 5.

Primer extension mapping of the 5′ end of the carAB and carB mRNAs. RNAs were extracted from L. plantarum CCM1904 grown on defined medium without arginine and no agitation at 30°C. Sequencing ladders generated with the oligonucleotide (P11 [5′-GTCCGCTAAAGTTAAGTATTTG-3′] for carAB; P12 [5′-AGCAATCGAATGAATGGCATTG-3′] for carB) used for the primer extension were loaded next to the reaction mixture (track RT). On the DNA sequence of the sense strand, the first nucleotide in the transcript is indicated as +1 and the promoter −10 sequence is boxed.

(ii) Arginine repression studies.

In L. plantarum, arginine inhibition of the biosynthetic ornithine transcarbamoylase activity was correlated to the presence of 11 E. coli-like ARG boxes in the intergenic carA/argC promoter region (3). Northern hybridizations with either a carA or a carB probe were assessed on mRNA extracted from L. plantarum grown in DLA with or without arginine. As a positive control, transcription of the constitutive gene ldhL (11) was visualized with a 1-kb band in all cases (data not shown). No transcripts were detected with the car probes in presence of arginine (Fig. 4), demonstrating arginine repression of the car operon. Two regions were similar to the B. subtilis ARG box consensus sequence (23). The first region (5′-CATtAAccAAAATGaAAT-3′; mismatches are in lowercase) was located on the carA initiation codon (Fig. 3); the second region is also similar to the E. coli ARG box consensus and was previously designated R9 (3). The lack of success in cloning L. plantarum carAB in E. coli may be explained by the arginine repressor binding to the ARG boxes present on the insert and not to its E. coli target. Moreover, plasmid instability may occur since the arginine repressor is an accessory protein involved in ColE1 multicopy plasmid stability (reviewed in reference 32). We conclude that L. plantarum may harbor an arginine repressor binding in the presence of its corepressor to a specific ARG box, as found for E. coli or other gram-positive bacteria, B. subtilis (23), and B. stearothermophilus (7).

Physiological analysis of the L. plantarum deletion mutants.

Since CPS produce CP for arginine and pyrimidine biosynthetic pathways, CPS-deficient derivatives were tested for arginine and uracil auxotrophy. Moreover, different growth conditions were tested such as aerobiosis and anaerobiosis because oxygen limitations induce arginine catabolism in some microorganisms (12), and CP produced from arginine catabolism provides pyrimidine biosynthesis in some lactobacilli (15). Our anaerobiosis conditions implied both oxygen depletion (less than 2%) and CO2 enrichment from 4 to 20%. Thus, to evaluate the effect of CO2 alone, we tested growth conditions in ordinary air enriched with either 4 or 20% CO2 and no change of oxygen concentration. We found no difference of growth between anaerobiosis and CO2-enriched air at either 4 or 20% CO2 (Table 1). On the contrary, incubation with less than 0.01% of CO2 (ordinary air) had a dramatic effect on L. plantarum growth in the presence of uracil alone. Thus in our tests, the important factor to alleviate uracil sensitivity in L. plantarum was CO2 and not oxygen.

TABLE 1.

Nutritional requirements of wild-type L. plantarum and CPS deletion mutants

| Strain | Grown on DLA with: | Growtha

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobiosis (ordinary air; 21, <0.05) | CO2-enriched air (21, 4 or 20) | Anaerobiosis (<2, 4 or 20) | ||

| Wild type (CCM1904) | No supplement | + | ++ | ++ |

| Arginine | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Uracil | − | ++ | ++ | |

| Arginine + uracil | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| CPS-P deficient (FB331) | No supplement | − | − | − |

| Arginine | − | − | − | |

| Uracil | − | ++ | ++ | |

| Arginine + uracil | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| CPS-A deficient (FB335) | No supplement | + | ++ | ++ |

| Arginine | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Uracil | − | − | − | |

| Arginine + uracil | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| CPS-P and CPS-A deficient (HN217) | No supplement | − | − | − |

| Arginine | − | − | − | |

| Uracil | − | − | − | |

| Arginine + uracil | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

Three days of growth on agar plates incubated at 30°C in different air conditions as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers in parentheses represent percent O2, percent CO2. ++, +, and − refer to very good, good, and no growth, respectively.

(i) In L. plantarum, no CP-producing system other than CPS-A and CPS-P is functionally significant.

To test if L. plantarum can produce CP for arginine and pyrimidine biosynthetic pathways using a system different from the two CPSs, strain HN217 (double CPS deletant) was tested for its ability to grow on defined media. Such an alternative CP-producing system may result from carbamate kinase activity. A carbamate kinase-like CPS has been identified in the prokaryote Pyrococcus furiosus (8) and shown to be enzymatically and structurally a carbamate kinase that produced rather than degraded CP in vivo (37). To assess if an anabolic carbamate kinase may be present in L. plantarum, the growth requirement of HN217 was tested. The absence of both CPSs in HN217 resulted in arginine and pyrimidine auxotrophy (Table 1). This result was confirmed in the single CPS deletants under conditions repressing the remaining CPS (Table 1; FB335 was uracil sensitive and FB331 was unable to grow in the presence of arginine alone in CO2-enriched air). Thus, in the tested conditions, no CP-producing system other than CPS-A and CPS-P is present or functionally significant in L. plantarum.

(ii) CPS-P is the major source of CP in L. plantarum.

To assess the CPS-P relative role in L. plantarum and whether CPS-P can supply CP necessary for arginine and pyrimidine biosynthesis, we tested the growth requirements of strain FB335 with only a functional CPS-P. FB335 was prototrophic for arginine and uracil (Table 1, without supplement). Thus, CPS-P alone can provide sufficient CP for the pyrimidine and arginine biosynthetic pathways. Despite its natural lability, CP can be transferred from the L. plantarum pyrimidine-specific CPS-P to the arginine biosynthetic CP-consuming enzyme, ornithine carbamyltransferase. This is reminiscent of the absence of CP pool compartmentalization found in B. subtilis, which also harbors two CPSs, and is consistent with the case of prokaryotes having a unique CPS such as E. coli but is different from the eukaryote Neurospora (27). Since unlike CPS-P deletion (see below), CPS-A deletion did not lead to auxotrophy, we concluded that CPS-P is the major source of CP in L. plantarum.

(iii) CPS-A is functional in L. plantarum grown in CO2-enriched air and provides CP only for arginine biosynthesis.

With only a functional CPS-A, FB331 was unable to grow on DLA (Table 1, without supplement). Thus, CPS-A is unable to provide CP for both the arginine and pyrimidine biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, unlike CPS-P, CPS-A is not essential for L. plantarum growth in minimal medium. FB331 grew in the presence of both arginine and uracil, demonstrating that only these corresponding biosynthetic pathways were impaired in FB331. FB331 grew in the presence of uracil only when CO2 was added to air (similar to the wild-type strain, where CPS-P was repressed and only CPS-A was theoretically available for CP biosynthesis [Table 1, with uracil in ordinary air]). The conditional pyrimidine auxotrophy suggests that CPS-A provides enough CP for arginine biosynthesis and is active only in CO2-enriched air. Since unlike CPS-P, CPS-A is not able to provide CP for pyrimidine biosynthesis, CPS-P may be more abundant than CPS-A, or possibly CPS-A activity remains lower than CPS-P activity even in presence of increased CO2 concentrations.

How can CO2 stimulate CP biosynthesis in L. plantarum?

CO2 may regulate CPS-A expression as described for various microbial genes (31). To assess if CO2 was absolutely required for carAB transcription, Northern hybridization and primer extensions were done on mRNAs extracted from cells cultivated in air with agitation. The 4.2-kb carAB transcript was detected, and primer extension of the 5′ end of the carB transcript was obtained (data not shown). These transcriptional results do not exclude CO2 as a modulator of the car genes but strongly suggest that the main effect of CO2 stimulation on CPS-A is not at the transcriptional level.

The most obvious explanation for CO2 stimulation is that CPS-A has a low affinity for CO2/HCO3− as a substrate. Nonauxotrophic E. coli mutants with sensitivity to uracil alleviated by raising CO2 in the gas phase were isolated (21) and recently correlated to amino acid substitutions within the large CPS subunit (5). These residues (Pro165, Pro170, Ala182, and Pro360, equivalent to L. plantarum Pro358) were conserved between L. plantarum and E. coli wild-type SYN subunits (protein alignment not shown). The CO2/bicarbonate level may be naturally low in L. plantarum grown under laboratory conditions since the two CO2-producing steps of the Krebs cycle (isocitrate dehydrogenase and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase) are inoperative in L. plantarum (25). If this is the case, CPS-A may have a normal affinity for its substrate and CPS-P may have an enhanced one. Whether CPS-A has a low affinity for bicarbonate, or other systems regulate CPS-A or the CP pool when L. plantarum is grown on CO2-enriched air, is not yet known.

The uracil sensitivity in aerobiosis but not in a CO2-enriched air was found not only in strain CCM1904 but also in 90 different strains of prototrophic L. plantarum and related species such as L. paraplantarum and L. pentosus isolated from various geographical environments (F. Bringel, unpublished data). Since CPS-P is inhibited in presence of uracil and CP synthesis relies on CPS-A, the higher CO2 dependency of CPS-A than of CPS-P seems to be a general feature in L. plantarum and probably also in related species. Evolution toward greater needs for CO2 was possible since different microorganisms coexist in natural fermentations; CO2 produced from heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria would be available for homofermentative lactic acid bacteria such as L. plantarum. Future biochemical and genetic studies will elucidate the unique influence of CO2 on L. plantarum CP metabolism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Delcour for providing plasmid pGID023 and R. Cunin for strain C600ΔcarB8.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bringel F. Carbamoylphosphate and natural auxotrophies in lactic acid bacteria. Lait. 1998;78:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bringel F, Frey L, Boivin S, Hubert J-C. Arginine biosynthesis and regulation in Lactobacillus plantarum: the carA gene and the argCJBDF cluster are divergently transcribed. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2697–2706. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2697-2706.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Piérard A, Stalon V. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delannay S, Charlier D, Tricot C, Villeret V, Piérard A, Stalon V. Serine 948 and threonine 1042 are crucial residues for allosteric regulation of Escherichia coli carbamoylphosphate synthetase and illustrate coupling effects of activation and inhibition pathways. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:1217–1228. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dion M, Charlier D, Wang H, Gigot D, Savchenko A, Hallet J-N, Glansdorff N, Sakanyan V. The highly thermostable arginine repressor of Bacillus stearothermophilus: gene cloning and repressor-operator interactions. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:385–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4781845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durbecq V, Legrain C, Roovers M, Piérard A, Glansdorff N. The carbamate kinase-like carbamoyl phosphate synthetase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus, a missing link in the evolution of carbamoyl phosphate biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12803–12808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elagöz A. Structure et régulation de l'expression des gènes de la voie de biosynthèse des pyrimidines de Lactobacillus plantarum CCM 1904. Ph.D. thesis. Strasbourg, France: Université Louis-Pasteur; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elagöz A, Abdi A, Hubert J-C, Kammerer B. Structure and organization of the pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway genes in Lactobacillus plantarum: a PCR strategy for sequencing without cloning. Gene. 1996;182:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00461-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferain T, Garmyn D, Bernard N, Hols P, Delcour J. Lactobacillus plantarum ldhL gene: overexpression and deletion. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:596–601. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.596-601.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamper M, Zimmermann A, Haas D. Anaerobic regulation of transcription initiation in the arcDABC operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4742–4750. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4742-4750.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmer G D, Allmang C, Ehresmann C, Guilley H, Richards K, Jonard G, Ehresmann B. The secondary structure of the 5′-noncoding region of beet necrotic yellow vein virus RNA3: evidence for a role in viral RNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1389–1395. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.6.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hols P, Ferain T, Garmyn D, Bernard N, Delcour J. Use of homologous expression-secretion signals and vector-free stable chromosomal integration in engineering of Lactobacillus plantarum for α-amylase and levanase expression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1401–1413. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1401-1413.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutson J Y, Downing M. Pyrimidine biosynthesis in Lactobacillus leichmannii. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:1249–1254. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.4.1249-1254.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandler O, Weiss N. Genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1209–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leong-Morgenthaler P, Zwahlen M C, Hottinger H. Lactose metabolism in Lactobacillus bulgaricus: analysis of the primary structure and expression of the genes involved. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1951–1957. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.1951-1957.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu C-D, Kwon D-H, Abdelal A T. Identification of greA encoding a transcriptional elongation factor as a member of the carA-orf-carB-greA operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3043–3046. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3043-3046.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyman C M, Moseley O, Wood S, Butler B, Hale F. Some chemical factors which influence the amino acid requirements of the lactic acid bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1947;167:177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinussen J, Hammer K. The carB gene encoding the large subunit of carbamoylphosphate synthetase from Lactococcus lactis is transcribed monocistronically. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4380–4386. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4380-4386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mergeay M, Gigot D, Beckmann J, Glansdorff N, Piérard A. Physiology and genetics of carbamoylphosphate synthesis in Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;133:299–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00332706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles E W, Rhee S, Davies D R. The molecular basis of substrate channeling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12193–12196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller C M, Baumberg S, Stockley P G. Operator interactions by Bacillus subtilis arginine repressor/activator, AhrC: novel positioning and DNA-mediated assembly of a transcriptional activator at catabolic sites. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:37–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5441907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morishita T, Deguchi Y, Yajima M, Sakurai T, Yura T. Multiple nutritional requirements of lactobacilli: genetic lesions affecting amino acid biosynthetic pathways. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:64–71. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.1.64-71.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morishita T, Yajima M. Incomplete operation of biosynthetic and bioenergetic functions of the citric acid cycle in multiple auxotrophic lactobacilli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene. 1983;26:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulus T J, Switzer R L. Characterization of pyrimidine-repressible and arginine-repressible carbamyl phosphate synthetases from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:82–91. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.82-91.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pouwels P H, Leer R J. Genetics of lactobacilli: plasmids and gene expression. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1993;64:85–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00873020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purcarea C, Evans D R, Hervé G. Channeling of carbamoyl phosphate to the pyrimidine and arginine biosynthetic pathways in the deep sea hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus abyssi. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6122–6129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stretton S, Goodman A E. Carbon dioxide as a regulator of gene expression in microorganisms. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1998;73:79–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1000610225458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Summers D. Timing, self-control and a sense of direction are the secrets of multicopy plasmid stability. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1137–1145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoden J B, Holden H M, Wesenberg G, Raushel F M, Rayment I. Structure of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase: a journey of 96 Å from substrate to product. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6305–6316. doi: 10.1021/bi970503q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoden J B, Raushel F M, Benning M M, Rayment I, Holden H M. The structure of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase determined to 2.1 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. 1999;D55:8–24. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998006234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tinoco I, Jr, Borer P N, Dengler B, Levine M D, Uhlenbeck O C, Crothers D M, Gralla J. Improved estimation of secondary structure in ribonucleic acids. Nature. 1973;246:40–41. doi: 10.1038/newbio246040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uriarte M, Marina A, Ramón-Maiques S, Fita I, Rubio V. The carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase of Pyrococcus furiosus is enzymatically and structurally a carbamate kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16295–16303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang H, Park S-M, Nolan W G, Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. Cloning and characterization of the arginine-specific carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]