Abstract

The impact of the COVID-19 infection, caused by Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), during the pandemic has been considerably more severe in pregnant women than non-pregnant women. Therefore, a review detailing the morphological alterations and physiological changes associated with COVID-19 during pregnancy and the effect that these changes have on the feto-placental unit is of high priority. This knowledge is crucial for these mothers, their babies and clinicians to ensure a healthy life post-pandemic. Hence, we review the placental morphological changes due to COVID-19 to enhance the general understanding of how pregnant mothers, their placentas and unborn children may have been affected by this pandemic. Based on current literature, we deduced that COVID-19 pregnancies were oxygen deficient, which could further result in other pregnancy-related complications like preeclampsia and IUGR. Therefore, we present an up-to-date review of the COVID-19 pathophysiological implications on the placenta, covering the function of the placenta in COVID-19, the effects of this virus on the placenta, its functions and its link to other gestational complications. Furthermore, we highlight the possible effects of COVID-19 therapeutic interventions on pregnant mothers and their unborn children. Based on the literature, we strongly suggest that consistent surveillance for the mothers and infants from COVID-19 pregnancies be prioritised in the future. Though the pandemic is now in the past, its effects are long-term, necessitating the monitoring of clinical manifestations in the near future.

Keywords: COVID-19, Placenta, Pregnancy, Morphology, Pathology

1. Introduction

The novel corona virus, SARS-CoV-2, discovered in Wuhan, China (2019), led to the calamitous pandemic, which left a massive death toll at its peak, resulting in several health-related repercussions which impacted healthcare, including maternal and foetal outcomes [1]. The virus, with an incubation period of ∼5 days (range, 2–14 days), results in symptoms including headaches, fever, diarrhoea, myalgia, cough, severe respiratory illness and death depending on its severity [1]. Notably, pregnant women and their unborn children are considered high-risk populations, as pregnancy-related infections correlate with a greater risk of morbidity and death [2,3]. In 2020, a total of 3,613,647 births were recorded in the United States, with 225,225 women delivering during the pandemic and approximately 6.9% of these births being affected by COVID-19 [4,5]. This was alarming for the healthcare system, as the effects of COVID-19 on pregnancies are still to be fully determined [6].

Mechanical and physiological alterations during normal pregnancies can significantly affect the immune system, respiratory system, susceptibility to infections, cardiovascular function and coagulation [2,7]. In addition, studies in pregnant women have shown that COVID-19 can result in haematological changes, inflammation that can or may result in a ‘cytokine storm’ and hypoxia which have all been linked to high mortality [[6], [7], [8]]. Furthermore, once infection triggers the maternal immune response, this will impact on the development of the foetal immune and nervous system, which could potentially result in neural impairments of the unborn baby [9,10]. In addition, mothers who contracted COVID-19 have been found to have a greater risk of preterm labour and pre-eclampsia [11]. On the other hand, there have been reports of the placental unit and foetus being unaffected by COVID-19 [12,13]. Hence, further research is needed on the placenta and its role in COVID-19 pregnancies since impairment to the placental function is central to a successful pregnancy.

A meta-analysis conducted by Wei et al. (2021) documented that the outcomes of a COVID-19 pregnancy, which can range from preterm birth, preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, diabetes, lymphopenia, stillbirth, low birth weight and even neonatal death. Elsaddig and Khalil (2021) noted that pregnant women with COVID-19 are at a greater risk of adverse maternal outcomes, with many in their third trimester even requiring intensive care [14]. The exact factors underlying the link between COVID-19 and preeclampsia remains unclear. However, common pathways are expected, given their mutual impact on angiogenic pathways and vascular alterations [15]. Furthermore, foetal vascular malperfusion were documented in numerous pregnancies, which could possibly contribute to preterm birth, stillbirth and affect foetal growth [15,16].

The placenta has numerous critical functions, including protecting the foetus from infections, xenobiotic molecules and maternal diseases [17,18]. Its key role in a successful pregnancy necessitates an interrogation of the impact of infection especially given that the blood flow to this organ forms a substantive part of cardiac output [19]. The placental foetal unit plays a key role in protection through forming a selective barrier which prevents the movement of pathogens from the maternal to foetal circulation, with a mononuclear inner layer of cytotrophoblasts which play an essential role in autophagy and resistance for viral infections (Fig. 1 ) [16,20,21].

Fig. 1.

Shows the schematic representation of the human chorionic villi highlighting the structure. The trophoblast differentiates into the extravillous trophoblast and villous. The villous is composed up of a monolayer of cytotrophoblastic cells from the floating villi (in the intervillous space) which are still attached the villous basement membrane. When these cells differentiate and proliferate, they form the external covering of the villus, the syncytiocytotrophoblast layer. Adapted from Evain-Brion and Malassiné [22].

The design of the villi allows it to innately play a role in the defence within the placenta, with a syncytium that is selective to pathogen entry through different receptors which are able to recognize different pathogens [[23], [24], [25]].

Importantly, the surge in new-borns who were found to be COVID-19 positive has resulted in transplacental transmission becoming the focal point in COVD-19 transmission [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. Furthermore, the possibility of antibodies from the mothers circulating blood passing through is of significance [30]. Indeed, a study conducted in the UK cohort reported that two of the five babies that died could have been due to COVID-19 complications, with one in 20 babies testing positive for COVID-19 in this study [12]. A case study conducted on 17 pregnant women in 2021, indicated that two neonates contracted COVID-19 and concluded that the SARS-CoV-2 infection could potentially result in preterm delivery and neonatal pneumonia [31]. Alarmingly, 25.5% of births were noted to be preterm in women who presented with COVID-19 [32]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Italy detected two cases of neonates who presented with COVID-19 as well as the SARS-CoV-2 genome in 2 placentas, 1 milk specimen, vaginal mucosa and the umbilical cord plasma indicating that mother-to-child transmission is possible [33]. Hence evidently COVID-19 can be transmitted through the placenta, thereby possibly affecting its structure and function [34,35].

Therefore, this review sheds light on the effects of COVID-19 in pregnancies, with its impact on the placenta being the focal point. It includes a background that covers the role of the placenta in COVID-19 pregnancies. Furthermore, the effects of COVID-19 on the placenta have been discussed, in addition to highlighting the link between COVID-19 and other gestational complications. Finally, the vaccine and therapeutic implications of COVID-19 on the placenta have been included in this review together with recommendations for life post pandemic.

2. The effect of COVID-19 on pregnancies

The pathophysiology of COVID-19 in general has been extensively described [36]. The angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor (a component of the Renin-Angiotensin system-RAS) is the entry point for SARS-CoV-2 in the human body and has multiple implications in terms of physiological responses where RAS is the main protagonist [37,38]. Active replication of this virus results in, amongst other effects, an increase in inflammatory responses, and the dysregulation of the RAS including the downregulation of ACE2 which increases vascular permeability, inflammation and vasoconstriction [39]. Interestingly, Fenizia et al. (2020) postulated that modulation of ACE2 levels could possibly be associated with susceptibility to the SARS-CoV-2 infection in the placenta.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is thought to be transmitted through the placenta by infecting the syncytiotrophoblasts of the villi resulting in an inflammatory response, or via the maternal blood through the uterine artery which will cross the interstitial space to enter the foetal circulation [40]. Furthermore, initially the virus infects the immune cells of the mother, thereafter transferring to the extravillous proximal trophoblast cells which allows it to be transmitted further to the core the villus and vasculature of the foetus [40].

Moreover, recent studies on COVID-19 pregnancies have noted several placental pathological changes, which include vascular and inflammatory alterations, placental infiltration, thrombo-embolic complications, necrosis and ischemia [7,41,42].

Various vascular pathological changes in placenta have been associated with the COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. These changes mainly include thrombosis, malperfusion and vasculopathy in both maternal and foetal circulations as summarized in Table 1 . Vascular changes may adversely affect the health of pregnant women and their unborn babies and cause severe health consequences [43,44].

Table 1.

Vascular alterations reported in the placentas of COVID-19 pregnancies.

| Placental pathological variations | Type of Study | Number of COVID-19 cases | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

[45] |

|

|

|

[46] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[47] |

|

|

|

[48] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[49] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[41] |

|

|

|

[50] |

| |||

|

|

|

[51] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[52] |

| |||

|

|

|

[53] |

| |||

|

|

|

[54] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[55] |

|

|

|

[56] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[57] |

| |||

|

|

|

[58] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[59] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[60] |

| |||

|

|

|

[61] |

| |||

|

|

|

[62] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[63] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[64] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[65] |

| |||

|

|

|

[66] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[67] |

|

|

|

[68] |

| |||

|

|

|

[69] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[44] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[70] |

|

|

|

[71] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[72] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[73] |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[74] |

|

Placental vascular changes due to COVID-19 infections during the third trimester have been extensively studied. Studies documented signs of maternal vascular malperfusion which included the presence of infarcts, thrombosis, increased syncytial knots, increased fibrin deposition, villous agglutination and accelerated villous maturation [44,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54],[56], [57], [58], [59], [60],[62], [63], [64], [65],68,71,73,74]. Furthermore, subsequent studies that reported multi case investigations of placentae from COVID-19 positive mothers which presented different features of foetal vascular malperfusion including avascular villi, karyorrhexis, mural fibrin deposition, villous hypoplasia and chorangiosis [44,46,48,49,51,54,56,59,62,63,65,66,69,73]. Patberg et al. (2021) concluded that COVID-19 pregnancies exhibited an increase in histopathological abnormalities of the placenta, namely villitis of unknown aetiology and foetal vascular malperfusion. Infarction together with chorionic haemangioma in the placenta have also been documented in these past few years [61,75]. Alterations in the uteroplacental circulation like malperfusion were attributed to hypoxia and shock [63]. Last year in South Africa Ramphal et al. (2022) documented vascular maladaptation, substantial fibrin deposition, an increase in villitis and vascular malperfusion. In addition to vascular alterations, pathological features indicative of inflammatory changes including chorioamnionitis/subchorionitis, intervillositis, chronic villitis and villous edema have also been identified in COVID-19 placentas as summarized in Table 2 [41,44,45,[48], [49], [50],[52], [53], [54], [55],[57], [58], [59], [60],63,65,66,[68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74]].

Table 2.

Shows alterations reported in the placentas of COVID-19 pregnancies which are indicative of inflammation.

| Placental pathological variations | Type of Study | Number of cases | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

[45] |

|

|

|

[48] |

|

|

||

|

|

|

[49] |

| |||

| |||

|

|

|

[41] |

|

|

|

[50] |

|

|

|

[52] |

|

|

|

[53] |

|

|

|

[54] |

| |||

|

|

|

[55] |

| |||

|

|

|

[57] |

|

|

|

[58] |

| |||

|

- Case Study |

|

[59] |

| |||

|

- Case study |

|

[60] |

|

- Case study |

|

[63] |

| |||

|

- Case study |

|

[65] |

| |||

|

|

|

[66] |

| |||

|

|

|

[68] |

|

|

|

[69] |

|

|

|

[44] |

|

|

|

[70] |

|

|

|

[71] |

|

|

|

[72] |

|

|

|

[73] |

|

|

|

[74] |

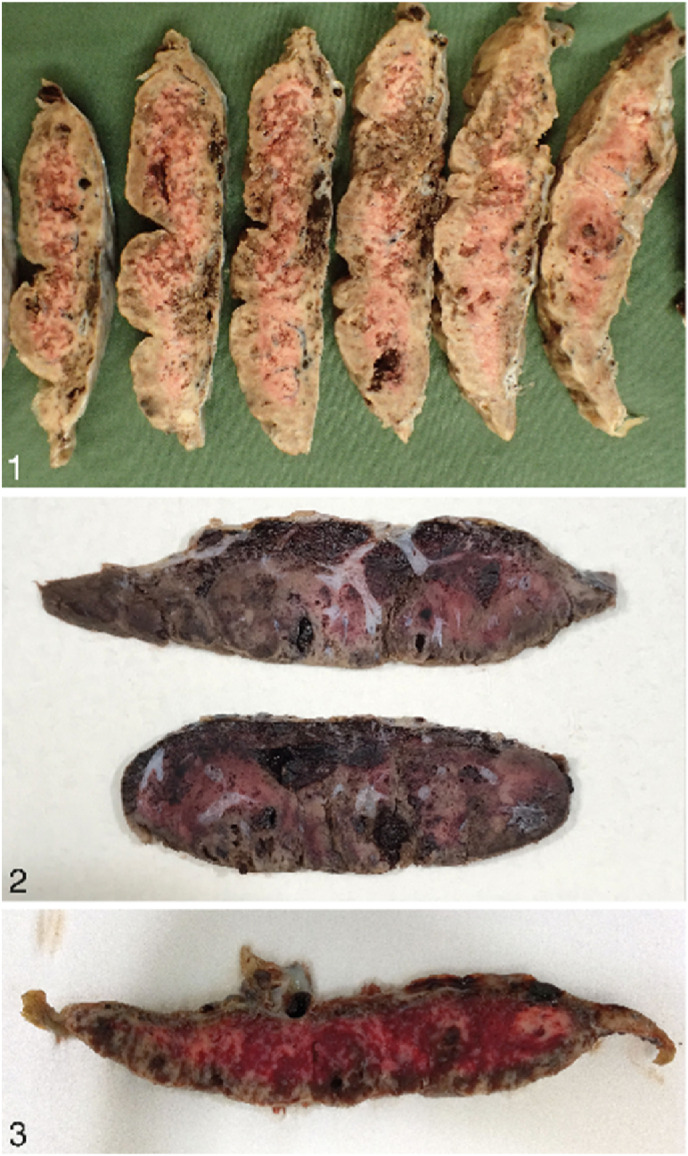

Edlow et al. (2020) noted that a decrease in the expression of transmembrane serine protease 2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the placenta can possibly protect the foetus against vertical transmission. However, aggregates of cytotoxic T lymphocytes as well as histiocytes have been detected in the intervillous space and further confirmed through CD8, CD68 and CD3 immunohistochemical staining which support and suggest the detection of chronic intervillositis in COVID-19 placentas [52]. Chronic intervillositis as a result of COVID-19 has been reported to be indicative of the virus in the syncytiotrophoblast [76]. Furthermore, Schwartz et al. (2021) documented that the presence of both syncytiotrophoblast necrosis and chronic histiocytic intervillositis together can result in the increased risk for transplacental foetal infection. Transplacental transmission of COVID-19 was documented in a case where the neonate was born with neurological complications and upon further investigation perivillous fibrin deposition together with intervillositis and infarction were detected in the placenta [57]. Sadly, there have been stillbirth cases which have observed the combined presence of massive perivillous fibrin deposition, trophoblast necrosis and chronic histiocytic intervillositis in the placenta which have been identified as SARS-CoV-2 placentitis (Fig. 2 ) [69,74,77].

Fig. 2.

Shows sections of placental samples that have been affected by SARS-CoV-2. Image 1 shows serially sectioned placenta from a case showing appearance of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. Microscopic examination showed massive perivillous fibrin deposition, chronic histiocytic intervillositis, and trophoblast necrosis. The extent of pathology resulting from these destructive lesions was greater than 90% and led to placental insufficiency and stillbirth. Image 2 shows gross pathological appearance of massive perivillous fibrin deposition that occurred with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis from a stillborn foetus. Intervillous thrombohematomas can be seen. Image 3 shows sectioned placental specimen from a case illustrating SARS-CoV-2 placentitis. There was 70% involvement of placental tissue with this destructive process [Adapted from Schwartz et al. (2022)].

Placentitis results in destructive events within the placenta that can affect >75% of it, thereby impacting its function to provide oxygen to the foetus consequently causing malperfusion and neonatal death [77]. Increased subchorionic and intervillous fibrin in placentas attributed to maternal hypoxia, have been documented in a past study [78]. Also a case of intrauterine foetal death was recently attributed to coagulopathy and hypoxia as a result of placental dysfunction due SARS-CoV-2 placentitis [71]. Hence vascular changes together with inflammatory alterations caused by COVID-19 in the placenta can result in dire consequences.

Furthermore, this virus often results in severe hypoxemia in pregnancy therefore altering the oxygen distribution to the placenta, as it is dependent on the uterine blood flow, fetoplacental system and maternal oxygen saturation [79]. Hypoxia and ischemia can be identified in the placenta through the increase in syncytial knots, whilst foetal hypoxia can be identified in the circulation through the increase in erythroblasts and nuclear debris [52,58,63,64,67,73]. Hypoxia induced by COVID-19 can result in altering the development of blood vessels, the blood supply as well as the development of the placenta which can have a devastating impact on the growing foetus [80]. This alteration in the blood supply and oxygenation due to COVID-19 is of critical interest, as in pregnancy, the demand for oxygen increases significantly, therefore with this compounding effect, there is bound to be dysregulation in oxygen supply to the placenta [81,82]. This then leads to the assumption that these alterations in the blood supply to the placenta can be mechanistically responsible for the morphological changes observed in the past years. A previous study conducted on severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) observed similar morphological alterations in the placenta and deduced these may be as a result of the changes in the blood flow [78]. Furthermore, a study in rats documented reduced levels of oxygen in pregnancy, resulting in a surge of oxidative stress markers which are associated with malperfusion [83].

Alterations in the placental structure due to hypoxia were noted to be adaptive changes that occur in order to enhance placental function, however some changes may be suggestive of ineffective placental development and damage [84]. In addition to the morphological changes mentioned above in the placenta as a result of COVID-19, a study conducted last year found an abnormality in the umbilical cord of COVID-19 pregnancies to be high, whereby it attached to the margin of the placenta resulting in altered functioning and blood flow [82]. In addition, vascular remodelling in the arteries of the placenta in COVID-19 pregnancies have now been identified through histological examinations and documented [85]. Therefore, it can be speculated that in COVID-19 pregnancies the oxygen demand increases, however this demand is not met.

3. COVID-19 and other gestational complications

In the previous section, the hypoxic conditions experienced during COVID-19 pregnancies were highlighted. The presence of such conditions are known to put a pregnant individual under risk for other gestational complications such as preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) which can impact the development of the foetus [86,87]. This poses great concern as it leads to the question of whether COVID-19 and its effects have the ability to predispose and cause further gestational complications. This raises further concerns for women who are already diagnosed with gestational complications and then contract COVID-19.

Jamieson and Rasmussen (2021) documented that COVID-19 pregnancies are related to unfavourable consequences like premature births and preeclampsia [88]. Furthermore, in the USA, it was found that women with COVID-19 were 1.2 times more likely to develop preeclampsia [89]. SARS-CoV-2 was more likely to present in the placentas of preeclamptic women and could trigger hypertensive disorders in pregnant woman [90]. IUGR was also documented in a case where the foetus presented with this abnormality at approximately 36 weeks of gestation, following the mother contracting COVID-19 in the third trimester [91]. Furthermore, COVID-19 has been documented to be associated with increasing the risk of IUGR [92]. Villar et al. (2021) documented a link between elevated preeclampsia occurrence and COVID-19 however this association is yet to be confirmed, as COVID-19 and preeclampsia may result in similar pathological alterations [93].

Placental hypoxia has been noted to be a contributing factor in both preeclampsia and IUGR [86]. Interestingly we propose that the alterations observed in the placenta as a result of COVID-19, preeclampsia and IUGR are as a result of hypoxia.

Recent studies have found that changes seen in COVID-19 pregnancies mimic those that are seen in preeclampsia and preeclamptic women should therefore be considered high risk if they contract COVID-19 [[94], [95], [96]]. Hence we propose that COVID-19 alters the blood flow in pregnancy resulting in placental hypoxia which has been documented to result in preeclampsia and IUGR, and therefore COVID-19 can predispose one of these gestational complications with similar clinical manifestations [97,98].

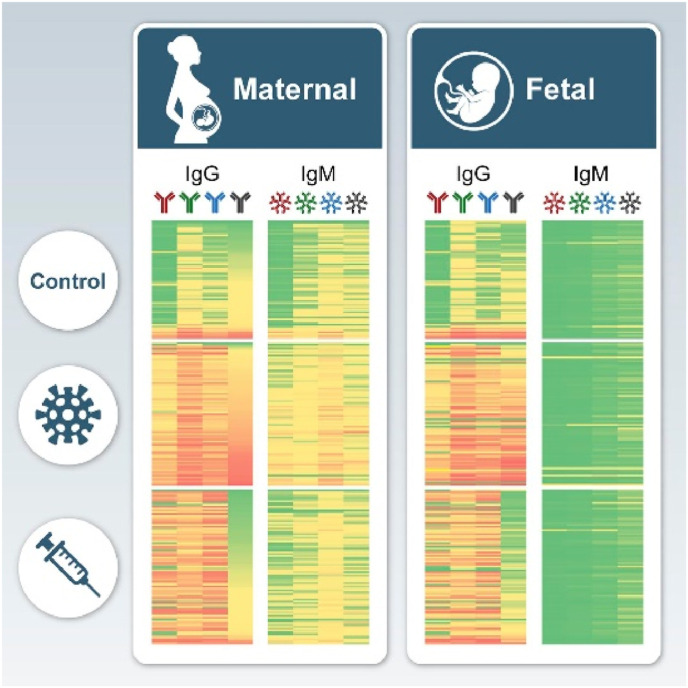

4. COVID-19 vaccine implications in pregnancies

It is known that vaccines signify important public health-advancement, through saving approximately 2–3 million lives yearly by providing adaptive immunity through generating antibodies upon exposure to a pathogen [99]. There are licensed vaccines available for 26 human pathogens and with the rapid rise in the number of vaccines becoming available, hesitancy towards vaccines have arisen with refusal differing across continents and cultures due to many concerns [100]. These concerns and hesitancy were further intensified with the implications of COVID-19 infections pertaining to maternal and foetal health [101]. In particular, vaccination during pregnancy protecting both the mother and unborn child from infection via the transfer of antibodies through the placental circulation (Immunoglobulin G- IgG) and mucosa (IgM, IgA, IgG) which releases antibodies into milk and colostrum to protect the neonate after birth [102]. However concerns around the COVID-19 vaccine only worsened with rumours of it eliciting antibodies that could attack the placenta thereby creating fear and anxiety in pregnant women, preventing them from considering the importance of this vaccine [103]. Furthermore, there has been a history of rumours about vaccines causing infertility which had also been circulated with the COVID-19 vaccine, where claims of cross reactivity between the human placental protein syncytin 1 and antibodies that recognize the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein emerged, resulting in many women declining this vaccine [103]. This despite the fact that, one should weigh the risk of a disease vs the risk of side effects of a vaccine when making a decision, as all types of medical treatment can pose adverse effects [99,100]. In keeping with this, the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine outweighed the risks in pregnant women, as it posed minimal risk like side effects ranging from nausea to fever and myalgia [104]. Furthermore, studies have found that antibodies generated from the COVID-19 vaccine were able to be transferred through the placenta to foetuses providing passive immunity postpartum [[105], [106], [107]]. Thus far several studies have documented that the COVID-19 vaccines have elicited maternal responses as they were able to document the presence of maternal IgG as well as foetal IgM antibodies for SARS-CoV-2, as presented in Fig. 3 [105,106,[108], [109], [110]]. In addition, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 protein receptor binding domain (RBD) and spike (S) antibodies were detected in umbilical cords as well as infants [105,111]. Wang et al. (2021) observed that the IgG levels for the SARS-CoV-2 antibodies decreased drastically postpartum. Global data on the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancies, infection rates and outcomes still need to be determined [112]. More importantly, the long-term effects of these vaccines still need to be established with critical focus on clinical manifestations that may arise due to these interventions.

Fig. 3.

A representative schematic diagram illustrated the maternal and foetal antibodies found after COVID-19 infection and vaccination [108].

5. Therapeutic implications

Therapeutic interventions during pregnancy, may pose threat to maternal and foetal health if not properly validated for safety. In this regard COVID-19 put an extra load by jeopardizing the ability to maintain a healthy pregnancy hence a host of new interventions were introduced [113,114].

Therapeutic interventions to treat COVID-19 included using various antiviral drugs, convalescent plasma (Passive immunotherapy) including using antiviral antibodies; nutritional supplements (folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin D); and miscellaneous treatments (Telbivudine, Azithromycin, Cobicistat) [114,115]. Significant efforts have been made to repurpose FDA-approved therapeutic drugs with known safety profiles during pregnancy in order to safely treat COVID-19 infection, which helped reduce the effects of COVID-19 therapeutic interventions [116]. However, some of the interventions mentioned above can have profound effects on pregnancy by affecting the placenta. Therefore, monitoring the impact of these drugs through investigating the physiological changes on the placenta would be beneficial in controlling future undesired side effects.

Pregnant women have been included in very few clinical trials for COVID-19 infection management (eg, SOLIDARITY trial [117], RECOVERY trial [117]). The severity of the mother's condition, underlying risk factors, gestational age, any potential maternal benefits, the likelihood of placental transfer, potential mechanisms for foetal harm, and the lack of knowledge regarding foetal and new-born risks should all be taken into account when deciding whether to use COVID-19-specific therapies during pregnancy. Patients being treated in hospitals may take the following medications presented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Therapeutic agents recommended for COVID-19 Pregnant patients.

| Therapeutic agent | Indications | Dosing, Precautions and other considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Heparin | Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized patients. |

|

| ||

| Dexamethasone |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSIAD) and Paracetamol |

|

|

|

|

|

| Remdesivir |

|

|

| ||

| Baricitinib, Tofacitinib |

|

|

| ||

| ||

| Tocilizumab, Sarilumab, Siltuximab, Anakinra |

|

|

|

Several studies have observed pathophysiological changes in the placentas of COVID-19 positive patients [41,45,46,48,54,56,65,126]. Majority of these studies were able to report the pathological effects of COVID-19 but lacked a pharmacological and therapeutic perspective. However, a recent study was able to reveal that COVID-19 treatment with antivirals, antibiotics, low molecular weight heparins and chloroquine increased the weight and efficiency of the placenta compared to untreated group [127].

Further investigation into the effects of COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines on the placenta and pregnancy in general are recommended to improve the health/safety of the mother and infant in the future.

6. Life after COVID-19

After exploring COVID-19 and the severity of its effects in pregnancy, it is critical to monitor the health of these mothers and new-borns to establish if there are any clinical manifestations as a result of the virus or its interventions. Many of the studies in this review reported no maternal deaths, illness or death in the new-borns as a result of COVID-19 [54,58]. However there have also been reports of maternal death as a result of COVID-19 and new-borns presenting with infection after birth [128,129]. Hence it is essential that these mothers and their new-borns from these COVID-19 pregnancies are monitored post-delivery and even after they recover as one is uncertain if the effects of COVID-19 will manifest clinically in the future. A study conducted by Liu et al. (2021) followed up with these infants for 9 months, where they observed transient early fine motor abnormalities in these babies born from COVID-19 pregnancies. However, we are still unaware of the long-term effects that COVID-19 and its therapeutic interventions may have, which will only manifest in the years to come, hence consistent surveillance on the mothers and new-borns from COVID-19 pregnancies need to be made a priority. It is in the best interest of these mothers and infants to be screened for potential aftereffects.

7. Conclusion

This review has highlighted the impact that COVID-19 had on maternal and foetal health. The effects of COVID-19 observed in the placenta were concerning as it suggested that there were alterations in the blood flow which resulted in hypoxic conditions as the placenta and consequently the foetus were not receiving adequate blood supply. Furthermore, we found that this could result in predisposing mothers to preeclampsia and IUGR resulting in further complications. Therefore, understanding the effects of the virus is imperative in determining therapeutic interventions to overcome current and even future adverse effects in both mother and baby. But most importantly, mothers and children from these pregnancies need to be monitored for any clinical manifestations that may arise in the years to come as a result of the alterations caused by COVID-19.

Funding information

The authors acknowledge the College of Health Sciences, the University of KwaZulu-Natal UKZN), National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant No MND210518602191) and Medical Research Council of South Africa.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Handling Editor: Dr A Perkins

References

- 1.Rasmussen S.A., Smulian J.C., Lednicky J.A., Wen T.S., Jamieson D.J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;222(5):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dashraath P., Wong J.L.J., Lim M.X.K., Lim L.M., Li S., Biswas A., Choolani M., Mattar C., Su L.L. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;222(6):521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daclin C., Carbonnel M., Rossignol M., Abbou H., Trabelsi H., Cimmino A., Delmas J., Rifai A.-S., Coiquaud L.-A., Tiberon A. Impact of COVID-19 infection in pregnancy and neonates: a case control study. J. Gynecol. Obstet.Hum. Reprod. 2022;51(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2022.102366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Son M., Gallagher K., Lo J.Y., Lindgren E., Burris H.H., Dysart K., Greenspan J., Culhane J.F., Handley S.C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy outcomes in a US population. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;138(4):542. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterman M.J., Hamilton B.E., Martin J.A., Driscoll A.K., Valenzuela C.P. 2022. Births: Final Data for 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoiwal K., Agarwal A., Gaurav A., Kumari R., Mittal A., Sabnani S., Mundhra R., Chawla L., Bahadur A., Chaturvedi J. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19: an interim analysis. Women Health. 2022;62(1):12–20. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2021.2007199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wastnedge E.A., Reynolds R.M., van Boeckel S.R., Stock S.J., Denison F.C., Maybin J.A., Critchley H.O. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol. Rev. 2021;101(1):303–318. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenling Y., Junchao Q., Xiao Z., Ouyang S. vol. 62. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo; 2020. (Pregnancy and COVID-19: Management and Challenges). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forestieri S., Pintus R., Marcialis M.A., Pintus M.C., Fanos V. COVID-19 and developmental origins of health and disease. Early Hum. Dev. 2021;155 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2021.105322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granja M.G., da Rocha Oliveira A.C., De Figueiredo C.S., Gomes A.P., Ferreira E.C., Giestal-de-Araujo E., de Castro-Faria-Neto H.C. SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women: neuroimmune-endocrine changes at the maternal-fetal interface. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2021;28(1):1–21. doi: 10.1159/000515556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abedzadeh‐Kalahroudi M., Sehat M., Vahedpour Z., Talebian P. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID‐19: a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021;153(3):449–456. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight M., Bunch K., Vousden N., Morris E., Simpson N., Gale C., O'Brien P., Quigley M., Brocklehurst P., Kurinczuk J.J. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. bmj. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker K.F., O'Donoghue K., Grace N., Dorling J., Comeau J.L., Li W., Thornton J.G. Maternal transmission of SARS‐COV‐2 to the neonate, and possible routes for such transmission: a systematic review and critical analysis. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020;127(11):1324–1336. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsaddig M., Khalil A. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology; 2021. Effects of the COVID Pandemic on Pregnancy Outcomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei S.Q., Bilodeau-Bertrand M., Liu S., Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ (Can. Med. Assoc. J.) 2021;193(16):E540–E548. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prochaska E., Jang M., Burd I. COVID-19 in pregnancy: placental and neonatal involvement. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020;84(5) doi: 10.1111/aji.13306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gude N.M., Roberts C.T., Kalionis B., King R.G. Growth and function of the normal human placenta. Thromb. Res. 2004;114(5–6):397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa M.A. The endocrine function of human placenta: an overview. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2016;32(1):14–43. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mourad M., Jacob T., Sadovsky E., Bejerano S., Simone G.S.-D., Bagalkot T.R., Zucker J., Yin M.T., Chang J.Y., Liu L. Placental response to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93931-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brett K.E., Ferraro Z.M., Yockell-Lelievre J., Gruslin A., Adamo K.B. Maternal–fetal nutrient transport in pregnancy pathologies: the role of the placenta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15(9):16153–16185. doi: 10.3390/ijms150916153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoo R., Nakimuli A., Vento-Tormo R. Innate immune mechanisms to protect against infection at the human decidual-placental interface. Front. Immunol. 2020:2070. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evain-Brion D., Malassiné A. Treballs de la Societat Catalana de Biologia; 2007. The Human Placenta: an Atypical Endocrine Organ; pp. 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins J.R., Skrzypczynska K.M., Zeldovich V.B., Kapidzic M., Bakardjiev A.I. Placental syncytiotrophoblast constitutes a major barrier to vertical transmission of Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.León-Juárez M., Martínez–Castillo M., González-García L.D., Helguera-Repetto A.C., Zaga-Clavellina V., García-Cordero J., Flores-Pliego A., Herrera-Salazar A., Vázquez-Martínez E.R., Reyes-Muñoz E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of viral infection in the human placenta. Pathogens and disease. 2017;75(7) doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreis N.-N., Ritter A., Louwen F., Yuan J. A message from the human placenta: structural and immunomodulatory defense against SARS-CoV-2. Cells. 2020;9(8):1777. doi: 10.3390/cells9081777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz D.A., Thomas K.M. Characterizing COVID-19 maternal-fetal transmission and placental infection using comprehensive molecular pathology. EBioMedicine. 2020;60 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghema K., Lehlimi M., Toumi H., Badre A., Chemsi M., Habzi A., Benomar S. Outcomes of newborns to mothers with COVID-19. Infect. Dis. News. 2021;51(5):435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husen M.F., van der Meeren L.E., Verdijk R.M., Fraaij P.L., van der Eijk A.A., Koopmans M.P., Freeman L., Bogers H., Trietsch M.D., Reiss I.K. Unique severe COVID-19 placental signature independent of severity of clinical maternal symptoms. Viruses. 2021;13(8):1670. doi: 10.3390/v13081670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsa Y., Shokri N., Jahedbozorgan T., Naeiji Z., Zadehmodares S., Moridi A. Possible vertical transmission of COVID-19 to the newborn; a case report. Arch.Acad. Emerg. Med. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.22037/aaem.v9i1.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta P.D., Pushkala K. How COVID-19 affects expecting women. Immunity. 2021;12:13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan S., Jun L., Siddique R., Li Y., Han G., Xue M., Nabi G., Liu J. Association of COVID-19 with pregnancy outcomes in health-care workers and general women. Clin. Microbiol. Infection. 2020;26(6):788–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamzelou J. Elsevier; 2020. Coronavirus May Cross Placenta. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenizia C., Biasin M., Cetin I., Vergani P., Mileto D., Spinillo A., Gismondo M.R., Perotti F., Callegari C., Mancon A. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 vertical transmission during pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong L., Tian J., He S., Zhu C., Wang J., Liu C., Yang J. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He Z., Fang Y., Zuo Q., Huang X., Lei Y., Ren X., Liu D. Vertical transmission and kidney damage in newborns whose mothers had coronavirus disease 2019 during pregnancy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2021;57(2) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sayad B., Afshar Z.M., Mansouri F., Salimi M., Miladi R., Rahimi S., Rahimi Z., Shirvani M. Pregnancy, preeclampsia, and COVID-19: susceptibility and mechanisms: a review study. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2022;16(2):64. doi: 10.22074/IJFS.2022.539768.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohn M.K., Hall A., Sepiashvili L., Jung B., Steele S., Adeli K. Pathophysiology of COVID-19: mechanisms underlying disease severity and progression. Physiology. 2020;35(5):288–301. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00019.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuki K., Fujiogi M., Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin. Immunol. 2020;215 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrer-Oliveras R., Mendoza M., Capote S., Pratcorona L., Esteve-Valverde E., Cabero-Roura L., Alijotas-Reig J. Immunological and physiopathological approach of COVID-19 in pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021;304(1):39–57. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng Z., Zhang J., Shi Y., Yi M. Research progress in vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 among infants born to mothers with COVID-19. Future Virol. 2022;17(4):211–214. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2021-0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosier H., Farhadian S.F., Morotti R.A., Deshmukh U., Lu-Culligan A., Campbell K.H., Yasumoto Y., Vogels C.B., Casanovas-Massana A., Vijayakumar P. SARS–CoV-2 infection of the placenta. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130(9) doi: 10.1172/JCI139569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prochaska E., Jang M., Burd I. COVID‐19 in pregnancy: placental and neonatal involvement. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020;84(5) doi: 10.1111/aji.13306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H.Y., Guo J., Zeng C., Cao Y., Ran R., Wu T., Yang G., Zhao D., Yang P., Yu X., Zhang W., Liu S.M., Zhang Y. Transient early fine motor abnormalities in infants born to COVID-19 mothers are associated with placental hypoxia and ischemia. Front Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.793561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubucs C., Groussolles M., Ousselin J., Sartor A., Van Acker N., Vayssière C., Pasquier C., Reyre J., Batlle L., Courtade-Saïdi M. Severe placental lesions due to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection associated to intrauterine fetal death. Hum. Pathol. 2022;121:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2021.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Algarroba G.N., Rekawek P., Vahanian S.A., Khullar P., Palaia T., Peltier M.R., Chavez M.R., Vintzileos A.M. Visualization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 invading the human placenta using electron microscopy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;223(2):275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baergen R.N., Heller D.S. Placental pathology in Covid-19 positive mothers: preliminary findings. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2020;23(3):177–180. doi: 10.1177/1093526620925569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baud D., Greub G., Favre G., Gengler C., Jaton K., Dubruc E., Pomar L. Second-trimester miscarriage in a pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2198–2200. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Facchetti F., Bugatti M., Drera E., Tripodo C., Sartori E., Cancila V., Papaccio M., Castellani R., Casola S., Boniotti M.B. SARS-CoV2 vertical transmission with adverse effects on the newborn revealed through integrated immunohistochemical, electron microscopy and molecular analyses of Placenta. EBioMedicine. 2020;59 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hecht J.L., Quade B., Deshpande V., Mino-Kenudson M., Ting D.T., Desai N., Dygulska B., Heyman T., Salafia C., Shen D. SARS-CoV-2 can infect the placenta and is not associated with specific placental histopathology: a series of 19 placentas from COVID-19-positive mothers. Mod. Pathol. 2020;33(11):2092–2103. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0639-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mongula J., Frenken M., Van Lijnschoten G., Arents N., de Wit‐Zuurendonk L., Schimmel‐de Kok A., van Runnard Heimel P., Porath M., Goossens S. COVID‐19 during pregnancy: non‐reassuring fetal heart rate, placental pathology and coagulopathy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;56(5):773–776. doi: 10.1002/uog.22189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mulvey J.J., Magro C.M., Ma L.X., Nuovo G.J., Baergen R.N. Analysis of complement deposition and viral RNA in placentas of COVID-19 patients. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2020;46 doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2020.151530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pulinx B., Kieffer D., Michiels I., Petermans S., Strybol D., Delvaux S., Baldewijns M., Raymaekers M., Cartuyvels R., Maurissen W. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection and preterm birth. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;39(12):2441–2445. doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-03964-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richtmann R., Torloni M.R., Otani A.R.O., Levi J.E., Tobara M.C., de Almeida Silva C., Dias L., Miglioli-Galvão L., Silva P.M., Kondo M.M. Fetal deaths in pregnancies with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Brazil: a case series. Case Rep. Women's Health. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2020.e00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shanes E.D., Mithal L.B., Otero S., Azad H.A., Miller E.S., Goldstein J.A. Placental pathology in COVID-19. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020;154(1):23–32. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sisman J., Jaleel M.A., Moreno W., Rajaram V., Collins R.R., Savani R.C., Rakheja D., Evans A.S. Intrauterine transmission of SARS-COV-2 infection in a preterm infant. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020;39(9):e265–e267. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smithgall M.C., Liu‐Jarin X., Hamele‐Bena D., Cimic A., Mourad M., Debelenko L., Chen X. Third‐trimester placentas of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2)‐positive women: histomorphology, including viral immunohistochemistry and in‐situ hybridization. Histopathology. 2020;77(6):994–999. doi: 10.1111/his.14215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vivanti A.J., Vauloup-Fellous C., Prevot S., Zupan V., Suffee C., Do Cao J., Benachi A., De Luca D. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao L., Ren J., Xu L., Ke X., Xiong L., Tian X., Fan C., Yan H., Yuan J. Placental pathology of the third trimester pregnant women from COVID-19. Diagn. Pathol. 2021;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13000-021-01067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giordano G., Petrolini C., Corradini E., Campanini N., Esposito S., Perrone S. COVID-19 in pregnancy: placental pathological patterns and effect on perinatal outcome in five cases. Diagn. Pathol. 2021;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13000-021-01148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsu A.L., Guan M., Johannesen E., Stephens A.J., Khaleel N., Kagan N., Tuhlei B.C., Wan X.F. Placental SARS‐CoV‐2 in a pregnant woman with mild COVID‐19 disease. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93(2):1038–1044. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ikhtiyarova G., Dustova N., Khasanova M., Suleymanova G., Davlatov S. Pathomorphological changes of the placenta in pregnant women infected with coronavirus COVID-19. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2021:1935–1942. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jaiswal N., Puri M., Agarwal K., Singh S., Yadav R., Tiwary N., Tayal P., Vats B. COVID-19 as an independent risk factor for subclinical placental dysfunction. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021;259:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jang W.-K., Lee S.-Y., Park S., Ryoo N.H., Hwang I., Park J.M., Bae J.-G. Pregnancy outcome, antibodies, and placental pathology in SARS-CoV-2 infection during early pregnancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18(11):5709. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu H.-Y., Guo J., Zeng C., Cao Y., Ran R., Wu T., Yang G., Zhao D., Yang P., Yu X. Transient early fine motor abnormalities in infants born to COVID-19 mothers are associated with placental hypoxia and ischemia. Front.Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.793561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menter T., Mertz K.D., Jiang S., Chen H., Monod C., Tzankov A., Waldvogel S., Schulzke S.M., Hösli I., Bruder E. Placental pathology findings during and after SARS-CoV-2 infection: features of villitis and malperfusion. Pathobiology. 2021;88(1):69–77. doi: 10.1159/000511324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patberg E.T., Adams T., Rekawek P., Vahanian S.A., Akerman M., Hernandez A., Rapkiewicz A.V., Ragolia L., Sicuranza G., Chavez M.R. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection and placental histopathology in women delivering at term. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;224(4):382. e1–382. e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shchegolev A., Kulikova G., Lyapin V., Shmakov R., Sukhikh G. The number of syncytial knots and VEGF expression in placental villi in parturient woman with COVID-19 depends on the disease severity. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021;171(3):399–403. doi: 10.1007/s10517-021-05236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwartz D.A., Baldewijns M., Benachi A., Bugatti M., Collins R.R., De Luca D., Facchetti F., Linn R.L., Marcelis L., Morotti D. Chronic histiocytic intervillositis with trophoblast necrosis is a risk factor associated with placental infection from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and intrauterine maternal-fetal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission in live-born and stillborn infants. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2021;145(5):517–528. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0771-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watkins J.C., Torous V.F., Roberts D.J. Defining severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) PlacentitisA report of 7 cases with confirmatory in situ hybridization, distinct histomorphologic features, and evidence of complement deposition. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2021;145(11):1341–1349. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2021-0246-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huynh A., Sehn J.K., Goldfarb I.T., Watkins J., Torous V., Heerema-McKenney A., Roberts D.J. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis and intraparenchymal thrombohematomas among COVID-19 infections in pregnancy. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5345. -e225345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kato M., Yamaguchi K., Maegawa Y., Komine‐Aizawa S., Kondo E., Ikeda T. Intrauterine fetal death during COVID‐19 pregnancy: typical fetal heart rate changes, coagulopathy, and placentitis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022;48(7):1978–1982. doi: 10.1111/jog.15302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mao Q., Chu S., Shapiro S., Young L., Russo M., De Paepe M.E. Placental SARS-CoV-2 distribution correlates with level of tissue oxygenation in COVID-19-associated necrotizing histiocytic intervillositis/perivillous fibrin deposition. Placenta. 2022;117:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramphal S., Govender N., Singh S., Khaliq O., Naicker T. Histopathological features in advanced abdominal pregnancies co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and HIV-1 infections: a case evaluation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022;X doi: 10.1016/j.eurox.2022.100153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwartz D.A., Avvad-Portari E., Babál P., Baldewijns M., Blomberg M., Bouachba A., Camacho J., Collardeau-Frachon S., Colson A., Dehaene I. Placental tissue destruction and insufficiency from COVID-19 causes stillbirth and neonatal death from hypoxic-ischemic injury: a study of 68 cases with SARS-CoV-2 placentitis from 12 countries. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2022;146(6):660–676. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2022-0029-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen S., Huang B., Luo D., Li X., Yang F., Zhao Y., Nie X., Huang B. Pregnancy with new coronavirus infection: clinical characteristics and placental pathological analysis of three cases. Zhonghua bing li xue za zhi= Chinese journal of pathology. 2020;49(5):418–423. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200225-00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Linehan L., O'Donoghue K., Dineen S., White J., Higgins J.R., Fitzgerald B. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis: an uncommon complication of maternal COVID-19. Placenta. 2021;104:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwartz D.A., Mulkey S.B., Roberts D.J. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination: clinical–pathologic correlations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023;228(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ng W., Wong S., Lam A., Mak Y., Yao H., Lee K., Chow K., Yu W., Ho L. The placentas of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a pathophysiological evaluation. Pathology. 2006;38(3):210–218. doi: 10.1080/00313020600696280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lapinsky S.E., Al Mandhari M. COVID-19 critical illness in pregnancy. Obstet. Med. 2022;15(4):220–224. doi: 10.1177/1753495X211051246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dang D., Wang L., Zhang C., Li Z., Wu H. Potential effects of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection during pregnancy on fetuses and newborns are worthy of attention. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020;46(10):1951–1957. doi: 10.1111/jog.14406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mauro M., Aliverti A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy. Breathe. 2015;11:297–301. doi: 10.1183/20734735.008615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Venkata S.M., Suneetha N., Balakrishna N., Satyanarayana K., Geddam J.B., Kumar P.U. Anomalous marginal insertion of umbilical cord in placentas of COVID-19-affected pregnant mothers: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15(1) doi: 10.7759/cureus.33243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Richter H., Camm E., Modi B., Naeem F., Cross C., Cindrova‐Davies T., Spasic‐Boskovic O., Dunster C., Mudway I., Kelly F. Ascorbate prevents placental oxidative stress and enhances birth weight in hypoxic pregnancy in rats. J. Physiol. 2012;590(6):1377–1387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.226340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siragher E., Sferruzzi-Perri A.N. Placental hypoxia: what have we learnt from small animal models? Placenta. 2021;113:29–47. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gychka S.G., Brelidze T.I., Kuchyn I.L., Savchuk T.V., Nikolaienko S.I., Zhezhera V.M., Chermak I.I., Suzuki Y.J. Placental vascular remodeling in pregnant women with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2022;17(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hu X.-Q., Zhang L. Hypoxia and mitochondrial dysfunction in pregnancy complications. Antioxidants. 2021;10(3):405. doi: 10.3390/antiox10030405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hu X.-Q., Zhang L. Hypoxia and the integrated stress response promote pulmonary hypertension and preeclampsia: implications in drug development. Drug Discov. Today. 2021;26(11):2754–2773. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2021.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jamieson D.J., Rasmussen S.A. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology; 2021. An Update on COVID-19 and Pregnancy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Litman E.A., Yin Y., Nelson S.J., Capbarat E., Kerchner D., Ahmadzia H.K. Adverse perinatal outcomes in a large United States birth cohort during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.MFM. 2022;4(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2022.100577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fabre M., Calvo P., Ruiz-Martinez S., Peran M., Oros D., Medel-Martinez A., Strunk M., Ruesca R.B., Schoorlemmer J., Paules C. Frequent placental SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19-associated hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2021;48(11–12):801–811. doi: 10.1159/000520179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kumar P., Kumar B., Saha M. Development of intrauterine growth restriction following Covid 19 infection in third trimester of pregnancy. J West Bengal Univ Health Sci. 2021;1(3):71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cavalcante M.B., Cavalcante C.T.d.M.B., Sarno M., Barini R., Kwak-Kim J. Maternal immune responses and obstetrical outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 and possible health risks of offspring. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2020.103250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Villar J., Ariff S., Gunier R.B., Thiruvengadam R., Rauch S., Kholin A., Roggero P., Prefumo F., Do Vale M.S., Cardona-Perez J.A. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID multinational cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(8):817–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mendoza M., Garcia‐Ruiz I., Maiz N., Rodo C., Garcia‐Manau P., Serrano B., Lopez‐Martinez R.M., Balcells J., Fernandez‐Hidalgo N., Carreras E. Pre‐eclampsia‐like syndrome induced by severe COVID‐19: a prospective observational study. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020;127(11):1374–1380. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jayaram A., Buhimschi I.A., Aldasoqi H., Hartwig J., Owens T., Elam G.L., Buhimschi C.S. Who said differentiating preeclampsia from COVID-19 infection was easy? Pregnancy Hypertension. 2021;26:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2021.07.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Papageorghiou A.T., Deruelle P., Gunier R.B., Rauch S., García-May P.K., Mhatre M., Usman M.A., Abd-Elsalam S., Etuk S., Simmons L.E. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;225(3):289. e1–289. e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Burton G.J., Jauniaux E. Pathophysiology of placental-derived fetal growth restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;218(2):S745–S761. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tong W., Giussani D.A. Preeclampsia link to gestational hypoxia. J. Dev. Origins. Health Dis. 2019;10(3):322–333. doi: 10.1017/S204017441900014X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vetter V., Denizer G., Friedland L.R., Krishnan J., Shapiro M. Understanding modern-day vaccines: what you need to know. Ann. Med. 2018;50(2):110–120. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2017.1407035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Geoghegan S., O'Callaghan K.P., Offit P.A. Vaccine safety: myths and misinformation. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:372. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goncu Ayhan S., Oluklu D., Atalay A., Menekse Beser D., Tanacan A., Moraloglu Tekin O., Sahin D. COVID‐19 vaccine acceptance in pregnant women. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021;154(2):291–296. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arora M., Lakshmi R. Vaccines-safety in pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021;76:23–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Male V. Are COVID-19 vaccines safe in pregnancy? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21(4):200–201. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00525-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chavan M., Qureshi H., Karnati S., Kollikonda S. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy: the benefits outweigh the risks. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021;43(7):814. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Flannery D.D., Gouma S., Dhudasia M.B., Mukhopadhyay S., Pfeifer M.R., Woodford E.C., Triebwasser J.E., Gerber J.S., Morris J.S., Weirick M.E. Assessment of maternal and neonatal cord blood SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and placental transfer ratios. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(6):594–600. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rathberger K., Häusler S., Wellmann S., Weigl M., Langhammer F., Bazzano M.V., Ambrosch A., Malfertheiner S.F. SARS-CoV-2 in pregnancy and possible transfer of immunity: assessment of peripartal maternal and neonatal antibody levels and a longitudinal follow-up. J. Perinat. Med. 2021;49(6):702–708. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2021-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Colavita F., Oliva A., Bettini A., Antinori A., Girardi E., Castilletti C., Vaia F., Liuzzi G. Evidence of maternal antibodies elicited by COVID-19 vaccination in amniotic fluid: report of two cases in Italy. Viruses. 2022;14(7):1592. doi: 10.3390/v14071592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Beharier O., Plitman Mayo R., Raz T., Nahum Sacks K., Schreiber L., Suissa-Cohen Y., Chen R., Gomez-Tolub R., Hadar E., Gabbay-Benziv R., Jaffe Moshkovich Y., Biron-Shental T., Shechter-Maor G., Farladansky-Gershnabel S., Yitzhak Sela H., Benyamini-Raischer H., Sela N.D., Goldman-Wohl D., Shulman Z., Many A., Barr H., Yagel S., Neeman M., Kovo M. Efficient maternal to neonatal transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J. Clin. Investig. 2021;131(13) doi: 10.1172/JCI150319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang X., Yang P., Zheng J., Liu P., Wei C., Guo J., Zhang Y., Zhao D. Dynamic changes of acquired maternal SARS-CoV-2 IgG in infants. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87535-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yang Y.J., Murphy E.A., Singh S., Sukhu A.C., Wolfe I., Adurty S., Eng D., Yee J., Mohammed I., Zhao Z. Association of gestational age at coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination, history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, and a vaccine booster dose with maternal and umbilical cord antibody levels at delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022;139(3):373–380. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gray K.J., Bordt E.A., Atyeo C., Deriso E., Akinwunmi B., Young N., Baez A.M., Shook L.L., Cvrk D., James K. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine response in pregnant and lactating women: a cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;225(3):303. e1–303. e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stock S.J., Carruthers J., Calvert C., Denny C., Donaghy J., Goulding A., Hopcroft L.E., Hopkins L., McLaughlin T., Pan J. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. 2022;28(3):504–512. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Abbas-Hanif A., Rezai H., Ahmed S.F., Ahmed A. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy and therapeutic drug development. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022;179(10):2108–2120. doi: 10.1111/bph.15582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Arco-Torres A., Cortés-Martín J., Tovar-Gálvez M.I., Montiel-Troya M., Riquelme-Gallego B., Rodríguez-Blanque R. Pharmacological treatments against COVID-19 in pregnant women. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10(21):4896. doi: 10.3390/jcm10214896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chilamakuri R., Agarwal S. COVID-19: characteristics and therapeutics. Cells. 2021;10:206. doi: 10.3390/cells10020206. s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published …, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Omolo C.A., Soni N., Fasiku V.O., Mackraj I., Govender T. Update on therapeutic approaches and emerging therapies for SARS-CoV-2 virus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;883 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Consortium W.S.T. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—interim WHO solidarity trial results. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384(6):497–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.D'Souza R., Malhamé I., Teshler L., Acharya G., Hunt B.J., McLintock C. A critical review of the pathophysiology of thrombotic complications and clinical practice recommendations for thromboprophylaxis in pregnant patients with COVID‐19. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;99(9):1110–1120. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Saad A.F., Chappell L., Saade G.R., Pacheco L.D. Corticosteroids in the management of pregnant patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;136(4):823–826. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bérard A., Sheehy O., Zhao J.-P., Vinet E., Quach C., Kassai B., Bernatsky S. Available medications used as potential therapeutics for COVID-19: what are the known safety profiles in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jorgensen S.C., Tabbara N., Burry L. A review of COVID-19 therapeutics in pregnancy and lactation. Obstet. Med. 2022;15(4):225–232. doi: 10.1177/1753495X211056211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mulangu S., Dodd L.E., Davey R.T., Jr., Tshiani Mbaya O., Proschan M., Mukadi D., Lusakibanza Manzo M., Nzolo D., Tshomba Oloma A., Ibanda A., Ali R., Coulibaly S., Levine A.C., Grais R., Diaz J., Lane H.C., Muyembe-Tamfum J.J., Sivahera B., Camara M., Kojan R., Walker R., Dighero-Kemp B., Cao H., Mukumbayi P., Mbala-Kingebeni P., Ahuka S., Albert S., Bonnett T., Crozier I., Duvenhage M., Proffitt C., Teitelbaum M., Moench T., Aboulhab J., Barrett K., Cahill K., Cone K., Eckes R., Hensley L., Herpin B., Higgs E., Ledgerwood J., Pierson J., Smolskis M., Sow Y., Tierney J., Sivapalasingam S., Holman W., Gettinger N., Vallée D., Nordwall J. A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381(24):2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Costanzo G., Firinu D., Losa F., Deidda M., Barca M.P., Del Giacco S. Baricitinib exposure during pregnancy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12 doi: 10.1177/1759720X19899296. 1759720x19899296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Karakaş Ö., Erden A., Ünlü S., Erol S.A., Goncu Ayhan Ş., Özdemir B., Tanacan A., Ozden Tokalioglu E., Ateş İ., Moraloğlu Tekin Ö., Omma A., Şahin D., Küçükşahin O. Can Anakinra and corticosteroid treatment be an effective option in pregnant women with severe Covid-19? Women Health. 2021;61(9):872–879. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2021.1981517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gulersen M., Prasannan L., Tam H.T., Metz C.N., Rochelson B., Meirowitz N., Shan W., Edelman M., Millington K.A. Histopathologic evaluation of placentas after diagnosis of maternal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.MFM. 2020;2(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tasca C., Rossi R.S., Corti S., Anelli G.M., Savasi V., Brunetti F., Cardellicchio M., Caselli E., Tonello C., Vergani P., Nebuloni M., Cetin I. Placental pathology in COVID-19 affected pregnant women: a prospective case-control study. Placenta. 2021;110:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hantoushzadeh S., Shamshirsaz A.A., Aleyasin A., Seferovic M.D., Aski S.K., Arian S.E., Pooransari P., Ghotbizadeh F., Aalipour S., Soleimani Z. Maternal death due to COVID-19. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;223(1):109. e1–109. e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zeng L., Xia S., Yuan W., Yan K., Xiao F., Shao J., Zhou W. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(7):722–725. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]