Abstract

Background/Aims

The safety of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in users of a P2Y12 receptor antagonist (P2Y12RA) under current guidelines has not been verified.

Methods

Patients treated by gastric ESD at Okayama University Hospital between January 2013 and December 2020 were registered. The postoperative bleeding rates of patients (group A) who did not receive any antithrombotic drugs; patients (group B) receiving aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy; and P2Y12RA users (group C) those on including monotherapy or dual antiplatelet therapy were compared. The risk factors for post-ESD bleeding were examined in a multivariate analysis of patient background, tumor factors, and antithrombotic drug management.

Results

Ultimately, 1,036 lesions (847 patients) were enrolled. The bleeding rates of group B and C were significantly higher than that of group A (p=0.012 and p<0.001, respectively), but there was no significant difference between group B and C (p=0.11). The postoperative bleeding rate was significantly higher in dual antiplatelet therapy than in P2Y12RA monotherapy (p=0.014). In multivariate analysis, tumor diameter ≥12 mm (odds ratio [OR], 4.30; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.99 to 9.31), anticoagulant use (OR, 4.03; 95% CI, 1.64 to 9.86), and P2Y12RA use (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 1.07 to 10.70) were significant risk factors for postoperative bleeding.

Conclusions

P2Y12RA use is a risk factor for postoperative bleeding in patients who undergo ESD even if receiving drug management according to guidelines. Dual antiplatelet therapy carries a higher risk of bleeding than monotherapy.

Keywords: Fibrinolytic agents, Endoscopic submucosal resection, Postoperative hemorrhage, Purinergic P2Y receptor antagonists

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a commonly used, effective treatment for early gastric neoplasms.1,2 Nonetheless, postoperative bleeding is a frequent complication of ESD3,4 and occurs in 4% to 8% despite advances in endoscopic technology.5-7 Antithrombotic agents, such as aspirin, P2Y12 receptor antagonists (P2Y12RA, thienopyridines), warfarin, and direct oral anticoagulants, are important risk factors for bleeding.8 In the aging population, the proportion of gastric ESD patients taking antithrombotic drugs is increasing, and antithrombotic drug management during ESD is being carefully considered. According to Japanese guidelines for endoscopy in patients taking antithrombotic drugs,9 aspirin and cilostazol can be continued when there is a high risk of thromboembolism, whereas P2Y12RA should be interrupted or replaced with aspirin or cilostazol. Also, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) should be changed to monotherapy with aspirin or cilostazol. However, this policy was based on reports that continued thienopyridine derivatives increased the risk of hemorrhagic complications after polypectomy of the colon;10 no data have supported this recommendation for gastric ESD.

In this study, we evaluated the risk of bleeding after ESD in patients who were taking antithrombotic drugs or P2Y12RA agents according to current Japanese guidelines. For further evaluation, we adjusted these antithrombotic factors with others that are known to affect the postoperative bleeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design and patient populations

We conducted a single-center, retrospective, case-control study. Patients treated by gastric ESD at Okayama University Hospital (Okayama, Japan) between January 2013 and December 2020 were registered. Patients and lesions were excluded if (1) final pathological results were other than gastric adenoma or carcinoma; (2) gastric perforation occurred; (3) patients’ antithrombotic drug management deviated from the current guidelines; and (4) cases had insufficient clinical data. For each patient and lesion, clinical and demographic data were collected by referring to the endoscopy and pathology reports and the medical records. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent for the recommended procedure. The study protocol was approved by the Okayama University Hospital Ethics Committee in February 2022 (approval number: 2203-318).

2. ESD procedure and perioperative management

ESD was performed with electrosurgical devices (IT knife or IT knife 2 [KD-610L or KD-611L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan], a Dual knife [KD-650L; Olympus]), and an electrosurgical generator (VIO 300D; Erbe, Marietta, GA, USA). The choice of surgical procedure and devices was left to the discretion of each endoscopist. Closure of mucosal defects after ESD was not performed in any cases. If there were no signs of perforation, second-look endoscopy was performed the day after the treatment in all patients. After second-look endoscopy, patients were allowed to drink water and take oral proton-pump inhibitors if no adverse events, including bleeding, had occurred. Oral intake was resumed 2 days after treatment, and 7 days later, patients were discharged if third-look endoscopy revealed no problems, including bleeding. In all patients who did not have postoperative bleeding, antithrombotic drugs were resumed the day after endoscopic surgery. For patients in whom bleeding was confirmed, endoscopy was performed every day, and antithrombotic drugs were resumed after hemostasis was confirmed.

3. The definition of postoperative bleeding

We defined postoperative bleeding as any episode of overt hematemesis/hematochezia; a drop in hemoglobin of ≥2 g/dL; or endoscopic hemostasis, angiographic embolization, or surgery and/or transfusion needed.11,12 All bleeding was confirmed by emergent endoscopy from the time of the completion of ESD to 28 days after ESD. Preventive hemostasis of visible vessels without evidence of bleeding during second-look endoscopy was not regarded as postoperative bleeding. Early bleeding was defined as bleeding within 48 hours after ESD, and late bleeding was defined as bleeding beyond 48 hours and after primary hemostasis on second-look endoscopy.

4. The management of antithrombotic drugs and patient stratification

Antithrombotic drugs were managed according to the guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in antithrombotic drug users by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society;9 cases whose management deviated substantially from the guidelines were excluded. The decision to discontinue antithrombotic drugs was made after the prescribing doctor approved, especially in cases of high risk of thrombosis.

We stratified patients and lesions according to their antithrombotic medication status as (1) patients who were not taking any kind of antithrombotic drugs (control group); (2) patients receiving aspirin or cilostazol as monotherapy, which was continued during the perioperative period or was withdrawn for 3 to 5 days with low risk of thromboembolism; (3) P2Y12RA users, including monotherapy and DAPT that had been withdrawn or replaced with aspirin/cilostazol for 5 to 7 days before ESD; and (4) others, including anticoagulant drug users. Patients taking other antiplatelet agents, such as ethyl icosapentate, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, and prostaglandin E1 derivative, were excluded from (1) to (3). Data were also collected on the details of antithrombotic drugs and perioperative management for cases not applicable to (1) to (3).

5. Outcomes

To assess the risk of postoperative bleeding of P2Y12RA, the bleeding rate and the incidence of thromboembolism in group C (P2Y12RA users including monotherapy and DAPT) were compared with those in groups A (control) and B (aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy users). Furthermore, we subdivided group C into C1 (monotherapy) and C2 (DAPT) groups and compared their bleeding risk.

To extract factors related to postoperative bleeding, we analyzed patients and lesions based on age, sex, comorbidity (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, central neurological disease, and chronic kidney disease with hemodialysis), status of antithrombotic drugs (aspirin or cilostazol, P2Y12RA, warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants), tumor depth, tumor diameter, grade of endoscopic gastric atrophy, and operator experience (expert, ≥100 cases of gastric ESD performed; trainee, <100 cases of gastric ESD performed).

6. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared with the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test. When more than two groups were compared, the Bonferroni correction was performed. We performed a propensity score matching analysis to adjust for significant differences in the confounding factors of age and sex in the baseline characteristics of the patients. A logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) and evaluate factors associated with post-ESD bleeding. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

1. Study flow diagram and clinicopathological characteristics

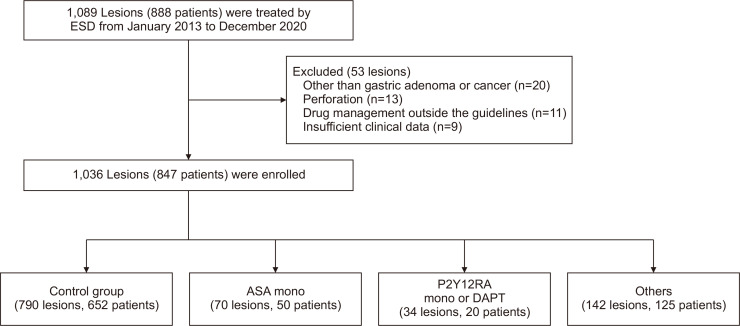

The flowchart of enrolment of patients and lesions is shown in Fig. 1. One thousand and eighty-nine lesions (888 patients) were treated by ESD from January 2013 to December 2020. Fifty-three lesions were excluded, and 1,036 lesions (847 patients) were enrolled. We divided all patients into four groups: control group (group A; 790 lesions, 652 patients); aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy group (group B; 70 lesions, 50 patients); P2Y12RA group, including monotherapy and DAPT (group C; 34 lesions, 20 patients); and others. In Table 1, we summarize the clinicopathological features of lesions of each group. Compared with groups B and C, patients in group A were significantly younger at the time of treatment, and the proportion of men was lower (p<0.001 and p=0.015, respectively). The prevalence of comorbidity (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and central neurological disease) were significantly more frequent among patients in groups B and C than in group A (control) patients.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; ASA, aspirin; P2Y12RA, P2Y12 receptor antagonist; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of Lesions in Groups A, B, and C

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B | Group C | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesions | 790 | 70 | 34* | - |

| Age, yr | 77.0±8.8 | 77.0±6.2 | 76.0±5.5 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male/female | 587/203 | 61/9 | 28/6 | 0.015 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (1.5) | 37 (52.9) | 16 (47.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 122 (15.4) | 16 (22.9) | 14 (41.2) | <0.001 |

| Central neurological disease | 5 (0.6) | 13 (1.9) | 15 (44.1) | <0.001 |

| CKD with hemodialysis | 5 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Tumor depth | ||||

| Mucosa | 661 (83.7) | 56 (80.0) | 27 (79.4) | 0.570 |

| Submucosa or deeper | 129 (16.3) | 14 (20.0) | 7 (20.6) | - |

| Tumor diameter, mm | 15.4±11.9 | 15.6±11.8 | 17.9±10.6 | 0.490 |

| Bleeding | 19 (2.4) | 6 (8.6) | 7 (20.6) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

Group A, control; Group B, aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy users; Group C, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including monotherapy (C1) and dual antiplatelet therapy (C2); CKD, chronic kidney disease.

*Group C1 (n=24) and group C2 (n=10).

2. Postoperative bleeding rate among various groups

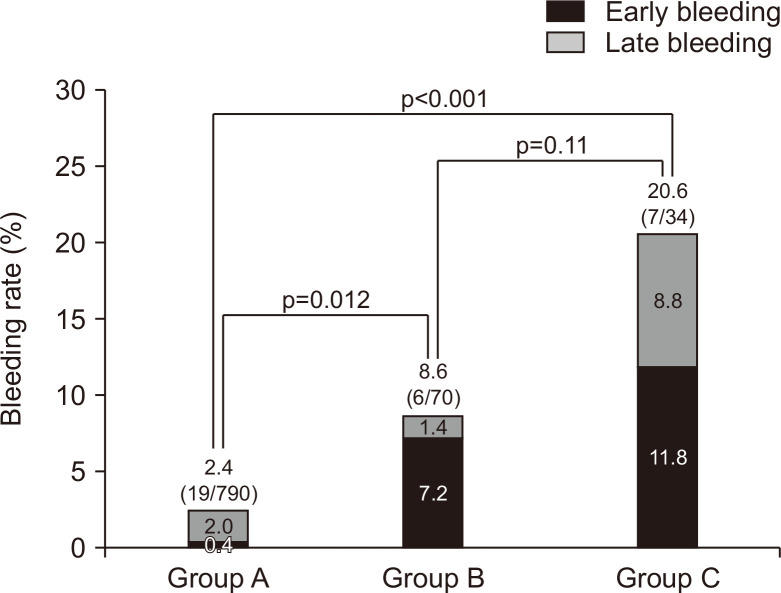

Fig. 2 shows the postoperative bleeding rate in each group. The rates were group A (2.4%, 19/790), group B (8.6%, 6/70), and group C (20.6%, 7/34). The bleeding rates of groups B and C were significantly higher than that of group A (p=0.012 and p<0.001, respectively), but there was no significant difference between groups B and C (p=0.11). In group A, most of the postoperative bleeding was late bleeding (early/late=3/16), but early bleeding was predominant in groups B and C (early/late=5/1 and 4/3, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Postoperative bleeding rates in groups A, B, and C.

Group A, control; Group B, aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy users; Group C, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including monotherapy (C1) and dual antiplatelet therapy (C2).

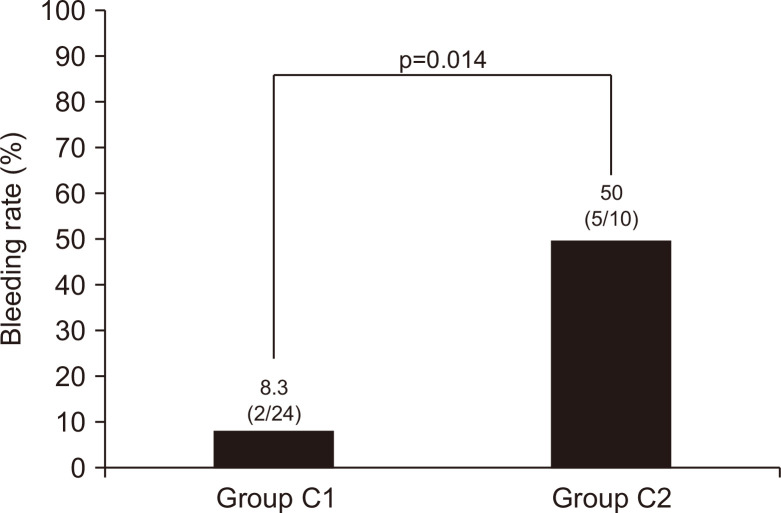

We also compared the bleeding rate between group C1 and group C2 (Table 2, Fig. 3). The postoperative bleeding rate was significantly higher in group C2 than in group C1 (p=0.014).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of Lesions in Groups C1 and C2

| Characteristics | Group C1 | Group C2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of lesions | 24 | 10 | - |

| Age, yr | 76.0±5.5 | 75.0±6.0 | 0.1 |

| Sex, male/female | 20/4 | 8/2 | 1.000 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (25) | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (42) | 4 (40) | 1.000 |

| Central neurological disease | 14 (58) | 1 (10) | 0.02 |

| CKD with hemodialysis | 0 | 0 | - |

| Tumor depth | |||

| Mucosa | 18 (75) | 9 (90) | 0.64 |

| Submucosa or deeper | 6 (25) | 1 (10) | - |

| Tumor diameter, mm | 15.5±8.6 | 13.5±14.6 | 0.38 |

| Bleeding | 2 (8) | 5 (50) | 0.014 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

Group C1, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including monotherapy; Group C2, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including dual antiplatelet therapy; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Fig. 3.

Postoperative bleeding rates in groups C1 and C2.

Group C1, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including monotherapy; Group C2, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including dual antiplatelet therapy.

3. Propensity score matching analysis

To adjust as much as possible for the patient background between groups A, B, and C, we used propensity score matching analysis. Regarding the rate of comorbidities, it was difficult to adjust between groups because most patients with a history of thrombosis were taking antithrombotic drugs. Therefore, we adjusted for age and sex between group A versus group B, and group A versus group C. Regarding groups B and C, there was no difference in patient background in age and sex. After matching, 69 patients and 34 patients were included in comparison of group A versus group B, and group A versus group C, respectively (Table 3). Bleeding rates remained significantly higher in groups B and C than that in group A (p=0.012 and p=0.005, respectively).

Table 3.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of Lesions in Group A vs Group B, and Group A vs Group C (after Propensity Score Matching)

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B | p-value | Group A | Group C | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of lesions | 69 | 69 | - | 34 | 34* | - |

| Age, yr | 76.0±5.6 | 77.0±6.0 | 0.77 | 77.0±6.8 | 76.0±5.8 | 0.62 |

| Sex, male/female | 62/7 | 60/9 | 0.79 | 26/8 | 28/6 | 0.77 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 | 36 (52.2) | <0.001 | 0 | 16 (47.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (15.9) | 15 (21.7) | 0.39 | 3 (8.8) | 14 (41.2) | 0.002 |

| Central neurological disease | 1 (1.4) | 13 (18.8) | <0.001 | 0 | 15 (44.1) | <0.001 |

| CKD with hemodialysis | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| Tumor depth | ||||||

| Mucosa | 61 (88.4) | 55 (79.7) | 0.28 | 29 (85.3) | 27 (79.4) | 0.53 |

| Submucosa or deeper | 8 (11.6) | 14 (20.3) | - | 5 (14.7) | 7 (20.6) | - |

| Tumor diameter, mm | 15.4±11.2 | 15.6±11.8 | 0.94 | 16.3±10.8 | 17.9±10.6 | 0.55 |

| Bleeding | 0 | 6 (8.7) | 0.012 | 0 | 7 (20.6) | 0.005 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

Group A, control; Group B, aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy users; Group C, P2Y12 receptor antagonist users including monotherapy (C1) and dual antiplatelet therapy (C2); CKD, chronic kidney disease.

*Group C1 (n=24) and group C2 (n=10).

4. Risk factors for postoperative bleeding

Table 4 shows the clinicopathological characteristics of the lesions divided into the bleeding group and the no bleeding group. In univariate analysis, there were significantly higher proportions of patients with cardiovascular disease and central neurological disease in the bleeding group. Tumor diameters of lesions were significantly larger in the bleeding group than in the no bleeding group. Regarding the status of antithrombotic drug usage, patients who had bleeding had a significantly lower rate of no drug use (group A) but higher rates of P2Y12RA monotherapy or DAPT use (group C). Furthermore, the rate of anticoagulant users and the proportion of patients who continued aspirin or cilostazol during the perioperative period were also higher in the bleeding group.

Table 4.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of Lesions in the Postoperative Bleeding Group and the No Bleeding Group

| Characteristics | Total | Bleeding | No bleeding | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of lesions | 1,036 | 46 | 990 | - |

| Age, yr | 73.0±8.7 | 73.5±9.1 | 73.0±8.7 | 0.881 |

| Sex, male/female | 786/250 | 35/11 | 751/239 | 1.000 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 83 (8.0) | 13 (28.3) | 70 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 184 (17.8) | 12 (26.1) | 172 (17.4) | 0.164 |

| Central neurological disease | 61 (5.9) | 6 (13.0) | 55 (5.6) | 0.048 |

| CKD with hemodialysis | 9 (0.9) | 0 | 9 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Tumor depth | ||||

| Mucosa | 873 (84.3) | 38 (82.6) | 835 (84.3) | 0.682 |

| Submucosa or deeper | 163 (15.7) | 8 (17.4) | 155 (15.7) | - |

| Tumor diameter, mm | 12.0±11.9 | 19.0±16.6 | 12.0±11.5 | <0.001 |

| Endoscopic gastric atrophy (-) | 35 (3.4) | 1 (2.2) | 34 (3.4) | 1.000 |

| Operator experiences | ||||

| Expert | 764 | 40 | 724 | <0.039 |

| Trainee | 272 | 6 | 266 | - |

| Antithrombotic drugs | ||||

| A, control* | 790 (76.3) | 19 (41.3) | 751 (75.9) | <0.001 |

| B, aspirin mono* | 70 (6.8) | 6 (13.0) | 64 (6.5) | 0.12 |

| C, P2Y12RA mono or DAPT* | 34 (2.3) | 7 (15.2) | 27 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| C1, P2Y12RA mono | 24 | 2 | 22 | |

| C2, P2Y12RA DAPT | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| Aspirin or CSZ continued† | 73 (7.0) | 8 (17.4) | 65 (6.6) | 0.012 |

| Warfarin or DOAC* | 75 (7.2) | 11 (23.9) | 64 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin or DOAC, mono | 56 | 9 | 47 | |

| Warfarin or DOAC+APA | 13 | 2 | 11 | |

| Multiple antithrombotic drugs* | 23 (2.2) | 7 (15.2) | 16 (1.6) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

CKD, chronic kidney disease; P2Y12RA, P2Y12 receptor antagonist; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; CSZ, cilostazol; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; APA, antiplatelet agent.

*The number of patients who meet each condition before endoscopic treatment. The condition on the day of treatment does not matter; †The number of patients who meet the conditions during the perioperative period, including the day of treatment.

We also evaluated variables with clinical significance by multivariate logistic regression analyses (Table 5). Tumor diameter ≥12 mm (OR, 4.30; 95% CI, 1.99 to 9.31) was a significant risk factor for postoperative bleeding. Continuation of aspirin or cilostazol was not significantly associated with a risk of postoperative bleeding (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 0.49 to 4.72), but P2Y12RA use (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 1.07 to 10.7) and anticoagulant use (OR, 4.03; 95% CI, 1.64 to 9.86) were significant risk factors. Multiple antithrombotic drug use was not a risk factor for bleeding in multivariate analysis.

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis to Detect the Post-Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Bleeding Risk Factors

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 2.48 (0.96–6.37) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.98 (0.45–2.12) | 0.95 |

| Central neurological disease | 1.71 (0.59–4.94) | 0.32 |

| Tumor diameter ≥12 mm | 4.30 (1.99–9.31) | <0.001 |

| Operator experiences (expert) | 1.54 (0.70–3.39) | 0.29 |

| Aspirin or CSZ continued | 1.53 (0.49–4.72) | 0.46 |

| P2Y12RA use | 3.40 (1.07–10.70) | 0.038 |

| Warfarin or DOAC use | 4.03 (1.64–9.86) | 0.002 |

| Multiple antithrombotic drugs | 1.67 (0.42–6.66) | 0.47 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CSZ, cilostazol; P2Y12RA, P2Y12 receptor antagonist; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant.

5. Adverse events

None of the patients developed thromboembolism during the perioperative period. All cases of postoperative bleeding were treated with endoscopic hemostasis, and no additional treatment such as interventional radiology or surgery was required.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, P2Y12RA use was an independent risk factor of postoperative bleeding, even under management according to the current Japanese guidelines. In contrast, continued aspirin or cilostazol was not a risk factor, a finding in agreement with reports13-15 and possible consensus on this issue. For P2Y12RA, on the other hand, several studies have suggested that it has a lower risk of bleeding than does low-dose aspirin,16,17 but there is currently no evidence that it is safer in bleeding control than aspirin alone, and the risk assessment of its postoperative bleeding differs depending on the reports.16-19 Those reports are of retrospective studies with a limited number of patients, which may reflect the difficulty in collecting P2Y12RA users, unlike those using aspirin. In addition, these studies include cases accrued both before and after the current guidelines, while the present study examined only cases treated under the guidelines.

In the present study, the overall postoperative bleeding rate was 4.4%; 8.6% in aspirin or cilostazol monotherapy and 8.3% in P2Y12RA monotherapy. These results are not much different from previous results.3,16,17 The present study did not find that multiple antithrombotic drug use, including DAPT, was a significant risk of postoperative bleeding, whereas several studies have reported that multiple drug use is a significant risk of bleeding.15,16 The reason for the different results in our study from previous reports could be the fewer cases of multiple drug use (n=23) than of single-use aspirin or P2Y12RA in our study. However, it is noteworthy that DAPT had a significantly higher bleeding rate than did aspirin and P2Y12RA, even with antithrombotic drug management according to the guidelines. In multiple drug cases, switching to monotherapy as much as possible before endoscopic intervention should be considered, but further studies are required to determine whether treatment with continuous P2Y12RA therapy is acceptable.

Recently, to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal and intracranial hemorrhage associated with low-dose aspirin and to maintain the effect of suppressing the risk of thrombotic events, treatment with continued P2Y12RA instead of aspirin after DAPT is being investigated in the field of cardiology.20,21 The latest guidelines of the Japanese Circulation Society also recommend P2Y12RA rather than aspirin as the single drug when switching from DAPT in acute coronary syndrome patients.22 Based on this background, the proportion of people taking P2Y12RA may increase in the future, and the risk of bleeding from taking P2Y12RA needs to be evaluated more carefully.

This study has limitations. First, it is a single-center, retrospective study, and the number of patients taking each antithrombotic drug was not sufficient to permit individual comparisons. Also, the number of cases could be too small to allow assessment the risk of developing thromboembolism. It has been reported that the risk of thrombosis due to antithrombotic drug cessation associated with endoscopic treatment is about 1%.17 Thromboembolism can have fatal consequences and should be carefully assessed for risk and benefit when withdrawing antithrombotic therapy. Although there were no cases of thromboembolism in this study, careful investigation of the balance between bleeding and thrombosis in a larger series is needed. Second, in instances when endoscopic follow-up is performed at another hospital after ESD, the occurrence of postoperative bleeding and thromboembolism may not be accurately recorded.

In conclusion, P2Y12RA, along with larger specimen size and anticoagulant therapy, were significant risk factors for postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD even under the current guidelines for endoscopy in patients using antithrombotic drugs. P2Y12RA use needs perioperative management as an increased risk of bleeding. DAPT carries a higher risk of bleeding than mono therapy. The number of users of these drugs is expected to increase in the future according to the recommendations in the field of cardiology, and further investigations in prospective studies of this effect on ESD are needed.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: R.H., S. Kawano. Data analysis and interpretation: R.H. Drafting of the manuscript: R.H., S. Kawano. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: R.H. Statistical analysis: R.H. Administrative, technical, or material support: S.I., S. Kuraoka, S.O., T.S., K.H., Y.K., H.K., M.I., Y.K. Study supervision: H.O. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, et al. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262–270. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lian J, Chen S, Zhang Y, Qiu F. A meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection and EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, Kim JM. The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2666–2677. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1627-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito I, Tsuji Y, Sakaguchi Y, et al. Complications related to gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection and their managements. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:398–403. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.5.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyahara K, Iwakiri R, Shimoda R, et al. Perforation and postoperative bleeding of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 1190 lesions in low- and high-volume centers in Saga, Japan. Digestion. 2012;86:273–280. doi: 10.1159/000341422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toyokawa T, Inaba T, Omote S, et al. Risk factors for perforation and delayed bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: analysis of 1123 lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:907–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yano T, Tanabe S, Ishido K, et al. Different clinical characteristics associated with acute bleeding and delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4542–4550. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi T, Ota K, Harada S, et al. The postoperative bleeding rate and its risk factors in patients on antithrombotic therapy who undergo gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M, et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:1–14. doi: 10.1111/den.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh M, Mehta N, Murthy UK, Kaul V, Arif A, Newman N. Postpolypectomy bleeding in patients undergoing colonoscopy on uninterrupted clopidogrel therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim JH, Kim SG, Kim JW, et al. Do antiplatelets increase the risk of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasms? Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mochizuki S, Uedo N, Oda I, et al. Scheduled second-look endoscopy is not recommended after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasms (the SAFE trial): a multicentre prospective randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Gut. 2015;64:397–405. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tounou S, Morita Y, Hosono T. Continuous aspirin use does not increase post-endoscopic dissection bleeding risk for gastric neoplasms in patients on antiplatelet therapy. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E31–E38. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390764.65160cfc261d4b16b423f3ac73b66314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuhata T, Kaise M, Hoteya S, et al. Postoperative bleeding after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kono Y, Obayashi Y, Baba Y, et al. Postoperative bleeding risk after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection during antithrombotic drug therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:453–460. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh S, Kim SG, Kim J, et al. Continuous use of thienopyridine may be as safe as low-dose aspirin in endoscopic resection of gastric tumors. Gut Liver. 2018;12:393–401. doi: 10.5009/gnl17384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igarashi K, Takizawa K, Kakushima N, et al. Should antithrombotic therapy be stopped in patients undergoing gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection? Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1746–1753. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatta W, Tsuji Y, Yoshio T, et al. Prediction model of bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: BEST-J score. Gut. 2021;70:476–484. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono S, Fujishiro M, Yoshida N, et al. Thienopyridine derivatives as risk factors for bleeding following high risk endoscopic treatments: Safe Treatment on Antiplatelets (STRAP) study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:632–637. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Numasawa Y, Kohsaka S, Ueda I, et al. Incidence and predictors of bleeding complications after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiol. 2017;69:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high-risk patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2032–2042. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura M, Kimura K, Kimura T, et al. JCS 2020 guideline focused update on antithrombotic therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2020;84:831–865. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]