Abstract

Objective:

Our objective was to examine associations of gut microbiome diversity and composition with directly measured regional fat distribution, including central fat, in a large community-based cohort.

Methods:

We conducted our cross-sectional investigation in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (N=815, 55.2% female, 65.9% white). We assessed fecal microbiome using whole-genome shotgun metagenomic sequencing, and measured trunk and leg fat using dual x-ray absorptiometry. We examined multivariable-adjusted associations of regional fat measures, BMI, or waist circumference with microbiome alpha diversity, microbiome beta diversity metrics, and species differential abundance (verified using two compositional statistical approaches).

Results:

Trunk fat, leg fat, BMI, and waist circumference all significantly explained similar amounts of variance in microbiome structure. Differential abundance testing identified 11 bacterial species significantly associated with at least 1 measure of body composition or anthropometry. Ruminococcus gnavus was strongly and consistently associated with trunk fat mass, consistent with prior literature.

Conclusions:

Microbiome diversity and composition, in particular higher abundance of Ruminococcus gnavus, associated with greater central fat mass, in addition to other measures of obesity. Randomized trials are needed to determine whether interventions targeting the reduction of these microbiome features results in reductions in central fat and its metabolic sequelae.

Keywords: Microbiome, Body fat distribution, Abdominal obesity, Adiposity

Introduction

Obesity is a major risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases and mortality1,2. Collected evidence from human studies and animal models indicate that imbalances in the gut microbiome (commonly called dysbiosis) are associated with overweight and obesity3. The modifiable nature of the gut microbiome makes it an attractive target for weight loss interventions4. As such, a greater understanding of which microbiome features are associated with obesity is needed.

While many studies have linked the gut microbiome with obesity, there have been inconsistencies in the strength of associations and the specific microbial signatures involved5. These inconsistencies may be due in part to the use of overall obesity measures (e.g., BMI), which are imperfect surrogate measures of fat mass and distribution6. The distribution of body fat is important, as abdominal fat portends greater cardiometabolic risk while lower-body fat is thought to be protective7,8. Inconsistencies in prior studies may also be a result of differences in microbiome sequencing techniques (i.e., shotgun metagenomic sequencing vs. 16s rRNA marker gene sequencing)9. Few studies have used shotgun metagenomic sequencing, which can allow for greater resolution at the species taxonomic level, as compared to the more widely used 16s rRNA marker gene sequencing which provides resolution usually to the genus level10. While there are some studies in adults of microbiome associations with directly measured fat mass 11–22, no studies have examined microbiome measured by whole genome shotgun sequencing with fat directly measured in both upper and lower regions.

In the current study, we address the abovementioned gaps in the literature. Our objective was to examine associations of gut microbiome diversity and composition (measured using whole genome shotgun metagenomic sequencing) with directly measured central and lower body fat in a large and racially/ethnically diverse community-based cohort. We hypothesize that gut microbiome diversity and altered gut microbiome composition are associated with central fat in a manner consistent with associations with overall obesity.

Methods

Study Population

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) is an ongoing prospective cohort study of men and women primarily from the Washington DC-Baltimore area, conducted by the National Institute on Aging23. The study initiated in 1958 with an open enrollment design with participants followed every 1–4 years dependent on their age (<60 every 4 years, 60–79 every 2 years, ≥80 every year). The inclusion criteria for participation in BLSA has been detailed elsewhere24; in brief participants must be aged ≥20 years, be free of mobility and cognitive impairments, have a weight < 300 pounds or a BMI < 40 kg/m2, and be free of major chronic diseases (apart from controlled hypertension). Each study visit is conducted during a 3-day study at the Clinical Research Unit of Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (IRP, NIA), where participants complete a battery of physical, neurocognitive function, laboratory and radiologic testing and provide information on medical history and complete dietary assessment through a questionnaire. The study protocol was approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from participants at each visit.

Collection of fecal specimens began in 2013 for microbiome assessment with 929 participants providing 1,841 fecal samples by 2019. For this analysis, 829 samples with complete sequenced microbiome data were included. We excluded individuals with missing body composition and covariate data and with a microbiome sequencing depth <100,000, which resulted in N=815 individuals for analysis.

Fecal Sample Collection and Processing

During the study visit, fecal samples were collected using a stool collection bowl. Participants were instructed to place the stool collection bowl on the toilet and deposit their stool directly into the container. Once this was completed, study staff collected the fecal sample and placed it into an empty tube that was stored at 4C and transferred to the clinical lab within 24 hours. At the clinical lab, 2 mL of specimen were aliquoted into one 50 mL Falcon tube without buffer and stored at −80 °C.

DNA extraction, sequencing, and annotation

DNA extraction and shallow shotgun sequencing was performed by Diversigen® (Minneapolis, MN). Briefly, DNA was extracted from fecal samples using the Qiagen PowerFecal Pro extraction kit. Libraries were prepared using the Nextera library preparation kit (Illumina, CA), and the 2×150 bp paired-end reads were sequenced using a NextSeq (Illumina, CA) per manufacturer instructions. Raw fastq files were processed using the bioBakery3 workflow25. Read-level quality control was performed using KneadData (v0.10.0) and Trimmomatic (v0.39)26, with taxonomic assignment using MetaPhlAn3 (v3.0.7). Viral genomic data were removed. Given the low prevalence of eukaryotes in these samples, eukaryotic genomic data were also removed.

Body Composition

We measured body composition using dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Briefly, we performed scans using DXA model DPX-L (Lunar Radiation, Madison, WI). We analyzed the scans using the Lunar enCORE version 16 program (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI). We defined leg fat as the sum of fat mass in both legs, trunk fat as the fat mass located in the trunk region, and total fat as the fat mass across the entire body.

Other Covariates

Participants self-reported their age, sex, race, smoking status, physical activity, and education on a study questionnaire administered at their clinic visit. We categorized race into “White”, “Black”, or “Other”; cigarette smoking as current smoking “yes” or “no”; and physical activity as “sedentary”, “low”, “medium”, and “high” activity levels. Participants reported education as years of education received. Participants also reported medication use at the study visit, and we used medication anatomic and therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification codes to define antibiotic use [yes/no] and metformin use [yes/no]. We assessed dietary intake data by having participants complete a validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)27. For this analysis we included dietary data from individuals that reported daily energy intake between 2,511.6 and 20,092.8 kJ (600 and 4,800 kcal). Adherence to a healthy dietary pattern (e.g., Mediterranean diet) may be associated with both gut microbiome composition20 and differences in body mass28; thus, we also conducted a multivariable analysis in which we adjusted for self-reported adherence to a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern. We calculated the Mediterranean-style diet score by assessing the intakes of 9 food groups and nutrients, which were divided into beneficial food components (i.e., vegetables, legumes, fruits and nuts, whole grain, fish, monounsaturated-to-saturated fatty acid ratio) and detrimental food components (i.e., meat, dairy, and alcohol)29. We then calculated a summary score for adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet, which ranged from 0 (worse adherence) to 9 (better adherence). Energy intake was defined as kilocalories/day.

Statistics

We present sample characteristics, overall and by quartile of trunk fat, as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or N (%). We estimated linear trends using linear regression for continuous variables, Cochran-Armitage trend test for binary variables, and a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for categorical variables with ≥2 categories. We used Pearson correlations to determine correlations between body composition (trunk fat and leg fat) and anthropometric (waist circumference and BMI) measures.

Diversity analyses

We performed microbiome diversity analyses on rarefied datasets. Briefly, we rarefied samples ten times without replacement to a depth of 140,000. We then averaged and rounded rarefied results to the nearest integer. The rarefying procedure removed one bacterial species (Corynebacterium aurimucosum) from diversity analyses.

As measures of microbial alpha diversity, we calculated observed species and the Shannon diversity index using the R package phyloseq30, and we calculated Faith’s phylogenetic diversity using the R package picante31. We included alpha diversity metrics as independent variables in separate linear regression models, with body composition measures and anthropometric measures as dependent variables. We adjusted alpha diversity regression models for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity; and we further adjusted models with observed species and Faith’s phylogenetic diversity for unrarefied sequencing depth.

We calculated microbial beta diversity using Bray-Curtis distance from the phyloseq package and unweighted and weighted UniFrac from the rbiom package32. We visualized beta diversity using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots and we tested differences in beta diversity metrics using the adonis2 function in the vegan33 package with 9 999 permutations. We adjusted beta diversity models for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity.

Compositional Analyses

Prior to differential abundance testing, we performed species-level filtering using the Permutation Filtering Test for microbiome data (PERFect) algorithm in R34. PERFect removes taxa with insignificant contributions to microbiome covariance by quantifying the loss from filtering and using permutation tests to determine if loss is due to randomness. We ran PERFect using default parameters and the algorithm speed setting of “full”. Application of PERFect filtering reduced the number of species from 551 to 114.

We performed differential abundance testing of species across body composition and anthropometric measures using Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction (ANCOM-BC)35. Briefly, ANCOM-BC uses a linear regression framework to model the absolute abundance of taxa after correction for sampling fraction bias. We dealt with zeros using the procedures implemented in ANCOM-II36. In the ANCOM-BC models, we included standardized terms for body composition or anthropometric measures as independent variables; consistent with diversity regression models, we adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity. We used an FDR corrected p-value of 0.05 to identify significant species associated with the body composition and anthropometric predictors of interest. Using the ANCOM-BC modeled absolute abundances, we generated restricted cubic spline plots for trunk fat as an independent variable and significantly associated species as dependent variables using the R package rms37; models were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity. Different differential abundance testing methods have been shown to generate inconsistent results and may impair replicability of findings across studies38. Therefore, we also tested differential abundance associations using the R package ALDEx239. Like ANCOM-BC, ALDEx2 takes a compositionally consistent approach to differential abundance testing; however, underlying methods are different, with ALDEx2 generating expected values from Monte-Carlo instances drawn from the Dirichlet distribution. Following a centered logratio transformation, we used the aldex.glm() function with default parameters; model independent variables and covariates were identical to those used in the ANCOM-BC approach. Given the confirmatory nature of this analysis, we used an FDR corrected p-value of 0.20 as statistically significant. We then used the R package ggtree40 to generate heat maps of the standardized coefficients from ANCOM-BC and ALDEx2 models for significantly differentially abundant species.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our findings. Due to potential for sex, race, and age differences in microbiome-obesity associations, we tested sex, race, and age group (<55, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+) interactions with alpha diversity. Significant interactions were defined a priori as a p < 0.05. In sensitivity analyses, we also added smoking status, antibiotic medication use, and metformin use as potential confounders in our models. These variables had a low prevalence in our sample and adjustment for them had no significant impact on primary results (see Supplementary Material), so we report our primary results without adjustment for these covariates. For compositional analyses (ANCOM-BC), we also investigated the effects of adjusting trunk fat and leg fat models for total body fat. Finally, to assess if dietary intake may have confounded microbiome-adiposity associations, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we restricted the overall sample to a subset of individuals that also had diet data (N=534) and then we compared regression results from multivariable-adjusted regression models before and after additional adjustment for energy intake and Mediterranean-style diet score adherence.

Results

Associations of participant characteristics with trunk fat

We present participant characteristics in Table 1 overall and by quartile of trunk fat. Compared to individuals in quartiles with lower levels of trunk fat, those with higher levels were more likely to be male, to identify as Black, to have lower levels of education and physical activity, and to have higher levels of metformin use.

Table 1:

Sample characteristics, overall and by quartile of trunk fat

| Characteristic | Overall N=815 |

Trunk Fat Qt 1 N=204 |

Trunk Fat Qt 2 N=204 |

Trunk Fat Qt 3 N=203 |

Trunk Fat Qt 4 N=204 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 70.7 (12.9) | 71.1 (15.6) | 71.0 (12.0) | 71.3 (13.1) | 69.4 (10.0) | |

|

| ||||||

| Sex (Female) | 450 (55.2%) | 134 (65.7%) | 117 (57.4%) | 99 (48.8%) | 100 (49.0%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | White | 537 (65.9%) | 150 (73.5%) | 129 (63.2%) | 130 (64.0%) | 128 (62.7%) |

| Black | 215 (26.4%) | 36 (17.6%) | 55 (27.0%) | 58 (28.6%) | 66 (32.4%) | |

| Other | 63 (7.7%) | 18 (8.8%) | 20 (9.8%) | 15 (7.4%) | 10 (4.9%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Education (years) | 17.7 (2.7) | 17.8 (2.7) | 17.9 (2.7) | 17.6 (2.5) | 17.3 (2.8) | |

|

| ||||||

| Physical Activity | Sedentary | 80 (9.8%) | 14 (6.9%) | 11 (5.4%) | 27 (13.3%) | 28 (13.7%) |

| Low | 313 (38.4%) | 76 (37.3%) | 69 (33.8%) | 78 (38.4%) | 90 (44.1%) | |

| Medium | 242 (29.7%) | 62 (30.4%) | 67 (32.8%) | 64 (31.5%) | 49 (24.0%) | |

| High | 180 (22.1%) | 52 (25.5%) | 57 (27.9%) | 34 (16.7%) | 37 (18.1%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Current Smoking | 17 (2.1%) | 4 (2.0%) | 2 (1.0%) | 7 (3.4%) | 4 (2.0%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Current Antibiotic Use | 21 (2.6%) | 4 (2.0%) | 5 (2.5%) | 6 (3.0%) | 6 (2.9%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Current Metformin Use | 38 (4.7%) | 2 (1.0%) | 5 (2.5%) | 15 (7.4%) | 16 (7.8%) | |

|

| ||||||

| Body Composition and Anthropometrics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Height (cm) | 167.4 (9.3) | 164.6 (9.1) | 166.6 (8.5) | 168.4 (9.6) | 169.9 (9.1) | |

|

| ||||||

| Weight (kg) | 77.1 (16.5) | 61.3 (9.1) | 71.5 (8.4) | 79.6 (10.0) | 95.9 (14.2) | |

|

| ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 (4.8) | 22.6 (2.0) | 25.7 (2.0) | 28.0 (2.5) | 33.2 (4.3) | |

|

| ||||||

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 91.1 (12.3) | 79.4 (8.8) | 87.4 (7.8) | 93.4 (7.7) | 104.0 (9.4) | |

|

| ||||||

| Trunk Fat (kg) | 12.6 (8.8, 17.3) | 6.5 (5.2, 7.6) | 11.0 (10.1, 11.8) | 14.7 (13.8, 15.6) | 20.1 (18.4, 23.7) | |

|

| ||||||

| Leg Fat (kg) | 9.2 (6.6, 12.1) | 6.6 (5.3, 8.9) | 8.5 (6.4, 11.0) | 9.6 (7.7, 12.1) | 12.8 (10.1, 16.0) | |

|

| ||||||

| Microbiome Alpha Diversity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Observed Species | 63.4 (12.4) | 63.0 (12.3) | 64.0 (11.7) | 64.5 (13.4) | 62.0 (12.2) | |

|

| ||||||

| Shannon Index | 3.0 (2.7, 3.2) | 3.0 (2.7, 3.2) | 3.0 (2.8, 3.2) | 3.0 (2.7, 3.2) | 2.9 (2.7, 3.2) | |

|

| ||||||

| Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity Index | 9.8 (1.6) | 9.7 (1.6) | 9.9 (1.5) | 10.0 (1.7) | 9.6 (1.6) | |

Data presented as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or N (%)Linear trend p-value across quartiles of trunk fat determined using linear regression (continuous variables), Cochran-Armitage trend test (sex, smoking, antibiotics, metformin), and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (race, education, physical activity).

We present Pearson correlations of body composition and anthropometric measures in Supplementary Table S1. Body composition and anthropometric measures were highly correlated with each other (all r > 0.63), with the exception of leg fat, which was more modestly correlated with waist circumference (r=0.29).

Microbiome diversity metrics are associated with central adiposity

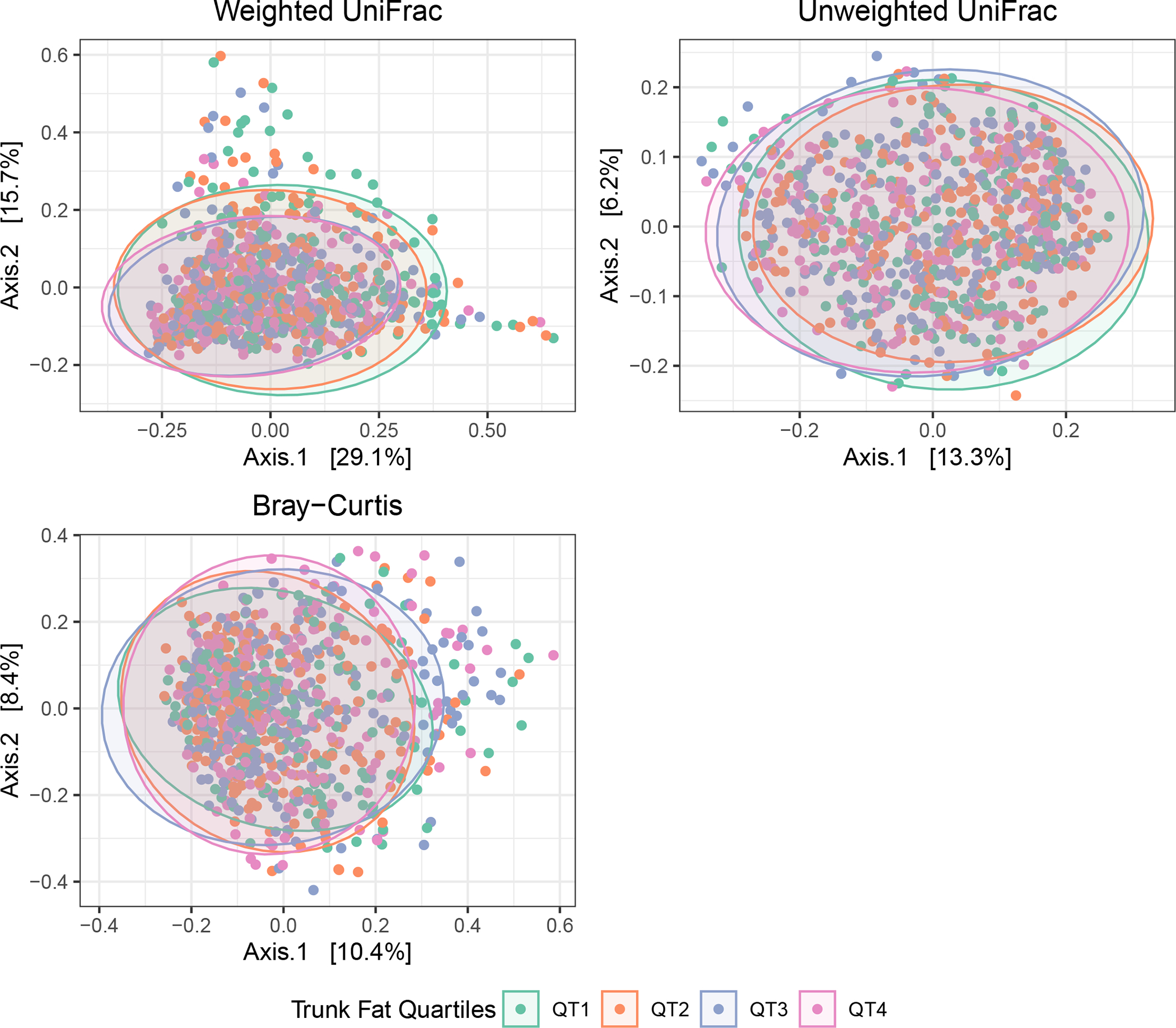

We report unadjusted and adjusted standardized associations of alpha diversity metrics with body composition and anthropometric measures in Table 2. In unadjusted models, alpha diversity metrics were significantly inversely associated with BMI, and similarly inversely (albeit not significantly) associated with objectively measured fats and waist circumference. After covariate adjustment, no alpha diversity metric was significantly associated with any central or overall obesity metric. However, beta diversity metrics were significantly associated with all measures of fat mass. Figure 1 shows beta diversity (Bray-Curtis, unweighted UniFrac, and weighted UniFrac) by quartiles of trunk fat. After adjustment for covariates, continuous measures of all fat and anthropometric measures were significant, explaining roughly 0.27–0.42% of variance in Bray-Curtis distance, 0.21–0.49% in unweighted UniFrac, and 0.49–0.94% of variance in weighted UniFrac distance (Table 3). Trunk fat and BMI generally explained similar and higher amounts of variance, while waist circumference and leg fat explained similar but lower amounts of variance.

Table 2:

Linear regression standardized β (95% CI) for a 1-standard deviation increase in microbial alpha diversity with body composition and anthropometric outcomes

| Predictor | Observed (per SD) † | Shannon (per SD) | Faith’s PD (per SD) † |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Trunk Fat | |||

| Unadjusted (per SD) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.02) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.02) | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.01) |

| Adjusted (per SD) | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.04) | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.03) |

|

| |||

| Leg Fat | |||

| Unadjusted (per SD) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.02) | −0.05 (−0.13, 0.03) | −0.07 (−0.14, 0.01) |

| Adjusted (per SD) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06) | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.04) |

|

| |||

| Waist | |||

| Unadjusted (per SD) | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.07) | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06) |

| Adjusted (per SD) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.05) | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.04) |

|

| |||

| BMI | |||

| Unadjusted (per SD) | −0.07 (−0.14, −0.00) | −0.08 (−0.15, −0.01) | −0.08 (−0.15, −0.01) |

| Adjusted (per SD) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.03) | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.02) | −0.05 (−0.13, 0.02) |

Adjusted models adjust for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity.

additionally adjusted for sequencing depth

Figure 1: Beta diversity by quartiles of trunk fat.

Beta diversity PcoA plots, using weighted UniFrac (top left), unweighted UniFrac (top right), and Bray-Curtis (bottom left) distances.

Table 3:

PERMANOVA marginal R2 results for associations of body composition and anthropometric measures with beta diversity

| Bray Curtis | Unweighted UniFrac | Weighted UniFrac | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal R2 | p-value | Marginal R2 | p-value | Marginal R2 | p-value | |

| Trunk Fat | 0.00423 | 0.0001 | 0.00488 | 0.0001 | 0.00944 | 0.0001 |

| Leg Fat | 0.00279 | 0.0008 | 0.00212 | 0.0146 | 0.00531 | 0.0003 |

| Waist Circumference | 0.00268 | 0.0026 | 0.00309 | 0.0004 | 0.00491 | 0.0008 |

| BMI | 0.00383 | 0.0002 | 0.00351 | 0.0002 | 0.00841 | 0.0001 |

PERMANOVA models adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity. R2 and p-values are from marginal associations.

Species associations with body composition and anthropometric measures

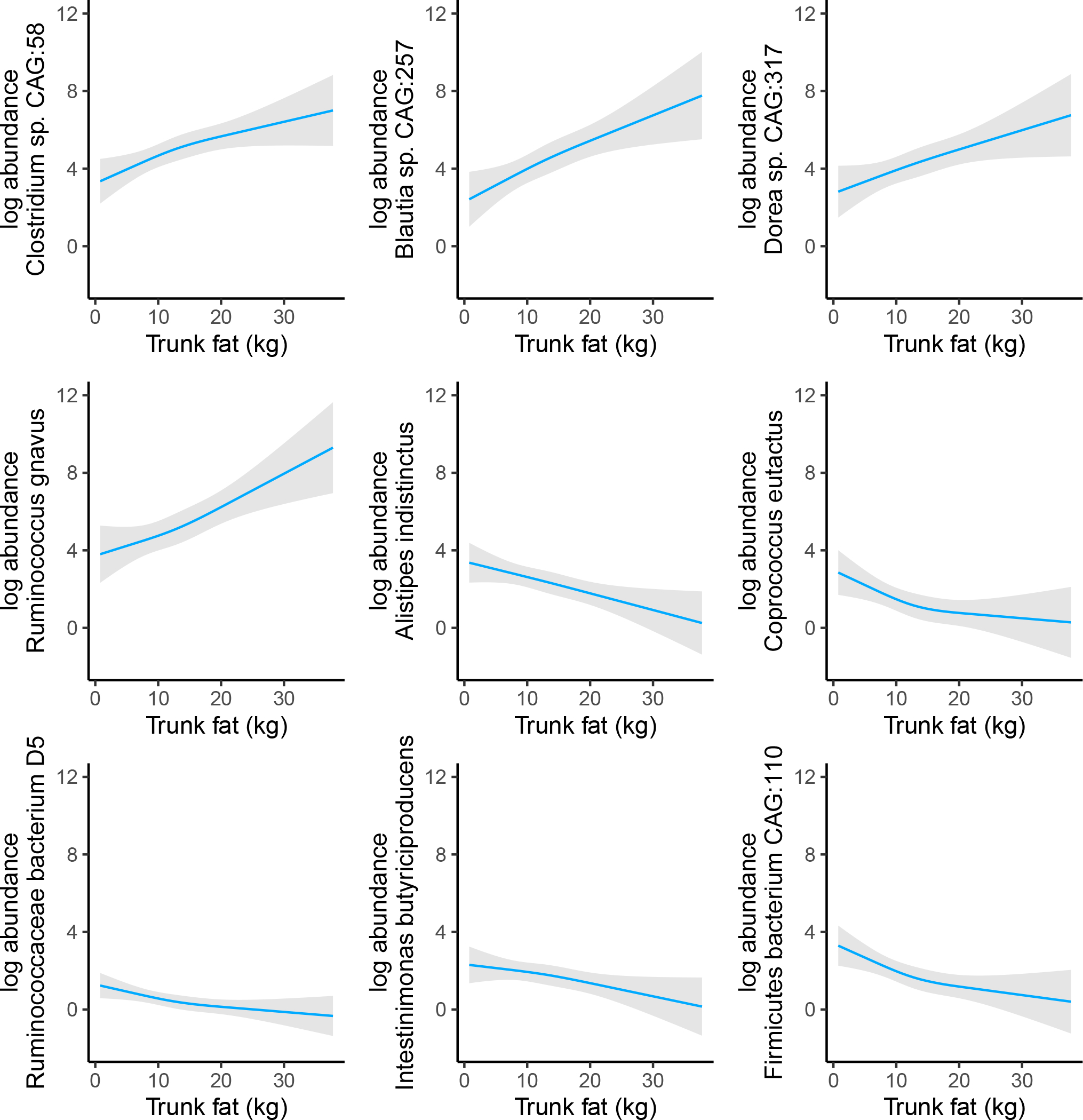

We estimated the standardized difference in species per standard deviation higher body composition or anthropometric measures using ANCOM-BC, and display results in Figure 2 and coefficients and FDR-corrected p-values in the Supplementary Materials. After adjustment for covariates, 11 species were significantly associated with at least 1 body composition or anthropometric measure. While effect sizes were similar across approaches, both BMI and trunk fat shared similar significant associations within and across approaches, with 4 species showing consistent significant positive associations (Ruminococcus gnavus, Dorea sp. CAG:317, Blautia sp. CAG:257, and Clostridium sp. CAG:58) and 4 species showing consistent significant inverse associations (Alistipes indistinctus, Ruminococcaceae bacterium D5, Intestinimonas butyriciproducens, and Firmicutes bacterium CAG:110). We further explored the linearity of associations of trunk fat with significantly associated species using restricted cubic spline plots (Figure 3). Associations were predominantly linear, indicating a dose-response relationship.

Figure 2: Per standard deviation change in species per standard deviation increase in body composition or anthropometric measure.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity. Asterisks denote significantly associated species at FDR < 0.05. Species are clustered by their phylogenetic relationships. Scatter strip plots of relative abundance for each species are provided on the right, and color coded by the prevalence of non-zero presence in the sample.

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; FDR = false discovery rate

Figure 3: Restricted cubic spline plots for assessing nonlinear associations of trunk fat with species.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and physical activity, and included a spline term with three knots for trunk fat.

Species associated with trunk fat and BMI also showed associations of similar magnitudes and directions with leg fat and waist circumference (Figure 2), indicating that species associations may reflect overall increasing adiposity. To test this, we compared trunk fat and leg fat results before and after adjustment for total body fat (Supplementary Figure S1). Statistical significance was lost for many of the trunk fat associations upon adjustment for total body fat, and associations of leg fat with species reversed direction after total body fat adjustment. Collinearity was however indicated for these models (all variance inflation factors for fat terms > 5), so caution is warranted in interpreting these findings.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sex or age group did not modify associations of microbiome alpha diversity metrics with body composition and anthropometric parameters (all p > 0.10). However, we did identify significant interactions between race and microbiome alpha diversity with respect to these outcomes. The interaction P value was p=0.0245 when we modeled an interaction term between Shannon diversity and race (Black vs. White) with respect to trunk fat as the dependent variable, and the P for interaction was p=0.0360 when we modeled an interaction term between observed species and race (Black vs. White) with respect to waist circumference as the dependent variable. Diversity results stratified by race are presented in the Supplementary Materials, though we suggest using caution when interpreting these results given the smaller sample sizes. Briefly, alpha diversity metrics were generally inversely associated with body composition and anthropometric measures in White participants, while associations tended to be null or positively associated in non-White participants.

Results for primary analyses with additional covariate adjustments (smoking status, antibiotic medication use, metformin medication use) and adjustment for Mediterranean dietary pattern (n=534) were consistent with the results from the primary analyses (Supplementary Materials). Using ALDEx2 as a differential abundance testing method, we identified similar directions and magnitudes of association for body composition and anthropometric measures with species (Supplementary Figure S2; coefficients in Supplementary Materials). ALDEx2 was more likely to identify statistically significant associations among positively associated bacteria, with all of these ANCOM-BC associations being replicated.

Discussion

In our study, overall microbiome structure (i.e., microbiome beta diversity) and the relative abundance of several bacterial species (e.g., Ruminococcus gnavus, Dorea sp. CAG:317, Blautia sp. CAG:257, and Clostridium sp. CAG:58) were associated with DXA-measured central adiposity (trunk fat). The majority of the bacterial species associated with DXA-measured trunk fat were also associated in a similar manner with other measures of adiposity (BMI, waist circumference, leg fat). Taken together, our findings show that associations of several bacterial species with measures of general adiposity extend to the more metabolically-pernicious trunk fat depot, and thus interventions targeting these species may lead to improved cardiometabolic health.

Our findings corroborate previously reported associations of microbiome features with BMI and central adiposity. A meta-analysis reported small but significant inverse associations between gut microbiome alpha diversity with BMI5. Although our results on microbiome alpha diversity and obesity were not significant following covariate adjustment, the magnitude of associations were similar to those reported in the meta-analysis, suggesting that larger sample sizes are needed to detect significant differences5. Interestingly, we identified significant interactions between alpha diversity metrics and self-reported race with respect to trunk fat, generally showing stronger inverse associations of alpha diversity with trunk fat in White participants than non-White participants. This finding is in line with a recent study41 suggesting that the inverse association of alpha diversity metrics with BMI was most consistently observed among White participants. Additional studies are needed to further corroborate these findings and to identify the drivers of race differences in microbiome feature associations with obesity.

Several of our identified differentially abundant species are also supported by prior studies. Notably, members of the Blautia11,13–15,42 and Ruminococcus14,20–22 genera have frequently been reported as being associated with central obesity measures, with most studies reporting positive associations. Blautia genera have been shown to have moderate heritability43 and to be positively associated with both visceral fat and the android-to-gynoid ratio in the TwinsUK cohort11,13. Blautia can produce the short chain fatty acid acetate44,45, which has been inconsistently associated with obesity in humans and may play a multifaceted role in weight regulation46. Whole genome shotgun sequencing studies have demonstrated a positive association between Ruminococcus gnavus and visceral fat and measures of poor cardiometabolic health20,21. Ruminococcus gnavus is associated with other inflammatory disease states such as Crohn’s Disease47 and can produce inflammatory polysaccharides48. Our finding of a positive relationship between Ruminococcus gnavus and trunk fat was particularly notable (consistent across statistical methods and across different obesity measures and given its high prevalence and abundance in this sample) and warrants further study.

We also identified several species which showed inverse associations consistent across obesity and adiposity measures, including Alistipes indistinctus, Ruminococcaceae bacterium D5, Instestinimonas butyriciproducens, and Firmicutes bacterium CAG:110; however, only the association of Firmicutes bacterium CAG:110 with trunk fat was corroborated using the ALDEx2 approach. Inverse correlations of visceral fat with some of these species (Ruminococcaceae bacterium D5, Firmicutes bacterium CAG:110, Alistipes indistinctus) have previously been reported18,20. In our sample, many of these inversely associated species generally had a lower prevalence and relative abundance compared to the positively associated species. Thus, we may be underpowered to detect these associations.

Central fat distribution is more strongly associated with cardiometabolic risk than overall obesity49. Thus, understanding how modifiable factors (such as gut microbes) relate to central body fat is important to uncover potential interventional targets to reduce harmful body composition phenotypes. In this analysis, we identified similar magnitudes of association of microbial features with indirect adiposity measures (BMI and waist circumference) and with directly measured central fat (trunk); these associations were similar in direction but slightly attenuated in magnitude for lower body fat (leg). Concordance of associations across different measures of obesity and adiposity has also been reported in other studies11,18,20,21. Further adjustment for total body fat attenuated the statistical significance of many of the trunk fat associations with bacterial species while reversing the directions of leg fat associations. Together, these findings may suggest that indirect adiposity measures could serve as surrogates for microbial associations with directly measured central fat accumulation in community-dwelling adults. Future observational studies, both cross-sectional and longitudinal in nature, are needed to further discern if these microbial features differentially track with specific fat depots, such as visceral and other ectopic fats.

Our study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study prevents us from inferring causality of our identified associations, and we are unable to rule out residual confounding factors such as sleep quality and aspects of mental health (e.g., depressive symptomatology). Additionally, repeated measures may be needed to better account for individual variation in the microbiome50. Second, our body composition measurements do not allow us to look at specific fat depots (e.g., visceral and subcutaneous fats) which have different propensities for cardiometabolic risk. Third, while our study population encompasses a large age range, most individuals are middle-aged or older; thus, results may not be as generalizable to younger populations. Our study also has several strengths. First, we are one of the few studies with both objectively measured regional body fat and shotgun metagenomic sequencing, allowing us greater resolution for both body composition assessment and for microbial species identification. Second, we use fat measures in both upper and lower body regions, providing a more detailed assessment of microbiome contributions to obesity phenotypes. Third, our study sample is large and racially diverse with good representation of both sexes. This may allow for better generalizability of results to other US adults.

In conclusion, using a large and multiracial cohort of US adults with directly assessed fat distribution, we corroborate previous findings of species-level associations of bacteria (e.g., Ruminococcus gnavus) with overall and regional adiposity. These findings suggest that microbiome features may be similarly associated with different aspects of obesity and subsequently obesity-associated cardiometabolic risks. Randomized trials are needed to determine whether interventions targeting the reduction of these microbial features results in reductions in central fat and its metabolic sequelae.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance Questions.

What is already known?

Imbalances in gut microbiome composition have been associated with overall obesity measured by anthropometry.

However, the specific species involved in the etiology has remained elusive as prior studies have largely relied on amplicon sequencing (vs. whole genome shotgun sequencing) and imprecise measurement of adiposity (e.g., body mass index vs. fat measured by imaging).

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

In a large, contemporary multiracial U.S. cohort, we used whole genome shotgun sequenced fecal microbiome and found overall microbiome diversity (i.e., beta diversity) and multiple bacterial species were associated DXA-measured fat depots, including trunk fat.

Among the bacterial species associated with metabolically pernicious trunk fat, Ruminococcus gnavus was particularly robust and consistent with prior research.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

Taken together with prior research, our findings suggest that Ruminococcus gnavus contributes to the development of metabolically pernicious central adiposity.

Randomized trials are needed to determine whether interventions targeting the reduction of Ruminococcus gnavus among other species results in reductions in trunk fat and its metabolic sequelae.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging and by R01AG050507 from the National Institute on Aging.

FUNDING:

N.T.M. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K01HL141589). C.T. and M.K.D. were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant T32HL007024.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon reasonable request. We will deposit human-removed genomic sequence data in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with corresponding NCBI Bioproject and Biosample accessions.

References

- 1.Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhaskaran K, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3·6 million adults in the UK. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:944–953. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(18)30288-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maruvada P, Leone V, Kaplan LM, Chang EB. The Human Microbiome and Obesity: Moving beyond Associations. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:589–599. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis CD. The Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Obesity. Nutr Today. 2016;51:167–174. doi: 10.1097/nt.0000000000000167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sze MA, Schloss PD . Looking for a Signal in the Noise: Revisiting Obesity and the Microbiome. mBio. 2016;7. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01018-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heymsfield SB, Peterson CM, Thomas DM, Heo M, Schuna JM Jr. Why are there race/ethnic differences in adult body mass index-adiposity relationships? A quantitative critical review. Obes Rev. 2016;17:262–275. doi: 10.1111/obr.12358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen GC, Arthur R, Iyengar NM, et al. Association between regional body fat and cardiovascular disease risk among postmenopausal women with normal body mass index. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2849–2855. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karpe F, Pinnick KE. Biology of upper-body and lower-body adipose tissue--link to whole-body phenotypes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:90–100. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laudadio I, Fulci V, Palone F, Stronati L, Cucchiara S, Carissimi C. Quantitative Assessment of Shotgun Metagenomics and 16S rDNA Amplicon Sequencing in the Study of Human Gut Microbiome. Omics. 2018;22:248–254. doi: 10.1089/omi.2018.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillmann B, Al-Ghalith GA, Shields-Cutler RR, et al. Evaluating the Information Content of Shallow Shotgun Metagenomics. mSystems. 2018;3. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00069-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaumont M, Goodrich JK, Jackson MA, et al. Heritable components of the human fecal microbiome are associated with visceral fat. Genome Biol. 2016;17:189. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1052-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pallister T, Jackson MA, Martin TC, et al. Untangling the relationship between diet and visceral fat mass through blood metabolomics and gut microbiome profiling. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017;41:1106–1113. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Roy CI, Beaumont M, Jackson MA, Steves CJ, Spector TD, Bell JT. Heritable components of the human fecal microbiome are associated with visceral fat. Gut Microbes. 2018;9:61–67. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1356556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roy CI, Bowyer RCE, Castillo-Fernandez JE, et al. Dissecting the role of the gut microbiota and diet on visceral fat mass accumulation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9758. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46193-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozato N, Saito S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Blautia genus associated with visceral fat accumulation in adults 20–76 years of age. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5:28. doi: 10.1038/s41522-019-0101-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min Y, Ma X, Sankaran K, et al. Sex-specific association between gut microbiome and fat distribution. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2408. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10440-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahleova H, Rembert E, Alwarith J, et al. Effects of a Low-Fat Vegan Diet on Gut Microbiota in Overweight Individuals and Relationships with Body Weight, Body Composition, and Insulin Sensitivity. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2020;12. doi: 10.3390/nu12102917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nie X, Chen J, Ma X, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiome and visceral fat accumulation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:2596–2609. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tavella T, Rampelli S, Guidarelli G, et al. Elevated gut microbiome abundance of Christensenellaceae, Porphyromonadaceae and Rikenellaceae is associated with reduced visceral adipose tissue and healthier metabolic profile in Italian elderly. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1–19. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1880221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asnicar F, Berry SE, Valdes AM, et al. Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nat Med. 2021;27:321–332. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01183-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan H, Qin Q, Chen J, et al. Gut Microbiome Alterations in Patients With Visceral Obesity Based on Quantitative Computed Tomography. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:823262. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.823262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lozano CP, Wilkens LR, Shvetsov YB, et al. Associations of the Dietary Inflammatory Index with total adiposity and ectopic fat through the gut microbiota, LPS, and C-reactive protein in the Multiethnic Cohort–Adiposity Phenotype Study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2021. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shock NW, Greulich RC, Costa PT Jr, et al. Normal human aging: The Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, Gerontology Research Center; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo PL, Schrack JA, Shardell MD, et al. A roadmap to build a phenotypic metric of ageing: insights from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Intern Med. 2020;287:373–394. doi: 10.1111/joim.13024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beghini F, McIver LJ, Blanco-Míguez A, et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. Elife. 2021;10. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talegawkar SA, Tanaka T, Maras JE, Ferrucci L, Tucker KL. Validation of Nutrient Intake Estimates Derived Using a Semi-Quantitative FFQ against 3 Day Diet Records in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:994–1002. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0518-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge L, Sadeghirad B, Ball GDC, et al. Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. Bmj. 2020;369:m696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2599–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kembel SW, Cowan PD, Helmus MR, et al. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1463–1464. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith DP. rbiom: Read/Write, Transform, and Summarize ‘BIOM’ Data; R package version 1.0.3. 2021.

- 33.Jari Oksanen FGB, Michael Friendly, Roeland Kindt, Pierre Legendre, Dan McGlinn, Peter R. Minchin, O’Hara RB, Simpson Gavin L., Solymos Peter, Stevens M. Henry H., Eduard Szoecs, Helene Wagner. vegan: Community Ecology Package; R package version 2.5–7. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smirnova E, Huzurbazar S, Jafari F. PERFect: PERmutation Filtering test for microbiome data. Biostatistics. 2019;20:615–631. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxy020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin H, Peddada SD. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3514. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17041-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaul A, Mandal S, Davidov O, Peddada SD. Analysis of Microbiome Data in the Presence of Excess Zeros. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2114. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank E Harrel Jr. rms: Regression Modeling Strategies; R package version 6.2–0. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nearing JT, Douglas GM, Hayes MG, et al. Microbiome differential abundance methods produce different results across 38 datasets. Nat Commun. 2022;13:342. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28034-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandes AD, Reid JN, Macklaim JM, McMurrough TA, Edgell DR, Gloor GB. Unifying the analysis of high-throughput sequencing datasets: characterizing RNA-seq, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and selective growth experiments by compositional data analysis. Microbiome. 2014;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, Guan Y, Lam TT-Y. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2017;8:28–36. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanislawski MA, Dabelea D, Lange LA, Wagner BD, Lozupone CA. Gut microbiota phenotypes of obesity. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. 2019;5:18. doi: 10.1038/s41522-019-0091-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goffredo M, Mass K, Parks EJ, et al. Role of Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids in Modulating Energy Harvest and Fat Partitioning in Youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:4367–4376. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodrich JK, Davenport ER, Beaumont M, et al. Genetic Determinants of the Gut Microbiome in UK Twins. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rey FE, Faith JJ, Bain J, et al. Dissecting the in vivo metabolic potential of two human gut acetogens. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22082–22090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.117713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Mao B, Gu J, et al. Blautia-a new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1–21. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1875796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernández MAG, Canfora EE, Jocken JWE, Blaak EE. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Acetate in Body Weight Control and Insulin Sensitivity. Nutrients. 2019;11. doi: 10.3390/nu11081943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall AB, Yassour M, Sauk J, et al. A novel Ruminococcus gnavus clade enriched in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Genome Medicine. 2017;9:103. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0490-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henke MT, Kenny DJ, Cassilly CD, Vlamakis H, Xavier RJ, Clardy J. Ruminococcus gnavus, a member of the human gut microbiome associated with Crohn’s disease, produces an inflammatory polysaccharide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116:12672–12677. doi: doi:10.1073/pnas.1904099116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Després J-P. Body Fat Distribution and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2012;126:1301–1313. doi: doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olsson LM, Boulund F, Nilsson S, et al. Dynamics of the normal gut microbiota: A longitudinal one-year population study in Sweden. Cell Host & Microbe. 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon reasonable request. We will deposit human-removed genomic sequence data in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with corresponding NCBI Bioproject and Biosample accessions.