Abstract

The ‘makeshift medicine’ framework describes how individuals address healthcare needs when they are unable to access the US healthcare system. The framework is applied to gender-affirming care, the health of people who inject drugs and abortion access. Recommendations for future research, advocacy and policy are made.

The USA spends more money on healthcare per capita than any other country and is touted as having the most-advanced tools to address health problems. However, despite steep investments in healthcare system reforms such as the Affordable Care Act, uninsurance and underinsurance remain massive problems1. Americans face challenges in accessing and navigating healthcare services within covered benefit networks. Moreover, not all groups have equal distributions of uninsurance and underinsurance. Indeed, there are substantial disparities in health insurance coverage by income, race, ethnicity and gender identity1,2. Uninsured and underinsured individuals are vulnerable to life-altering medical expenses, worsened medical conditions and excess mortality when healthcare use is delayed or is not received at all.

A fractured healthcare system

Individuals who experience a need for medical care may face inaccessible, inadequate or nonexistent healthcare services. We refer to these as healthcare access barriers. What happens when an individual experiences a threat to their health and recognizes the need to address this threat, but lacks access to or cannot navigate the healthcare system to receive care? Experiencing healthcare access barriers may force individuals to practice ‘makeshift medicine’ – the practice of meeting one’s healthcare needs outside of formalized settings as a response to exclusion from the healthcare system.

Our makeshift medicine framework is informed by two primary existing lines of thought and research. First, Montori3 describes the notion of ‘common care’ as a way towards a more-sustainable health system. Common care is the interplay of care provision between human beings, juxtaposed with the vertical transfer of medical knowledge and resources from healthcare provider to patient3. Given the increasingly industrial healthcare system, Montori argues that a resurgence of common care is needed and that, through mutual aid, a healthier society is possible3. Second, in Healthcare Off the Books, Raudenbush4 identifies and characterizes a formal–informal hybrid healthcare system in which individuals who have access to healthcare resources serve as intermediaries, providing health resources from the formalized healthcare system to others who lack access to care.

These two bodies of work inform our makeshift medicine framework by acknowledging that individuals within and outside the formal healthcare system may come to rely on one another to meet their healthcare needs and that intermediaries (for example, community support) may have an important role in helping those without access to formalized healthcare to address their health needs.

The makeshift medicine framework

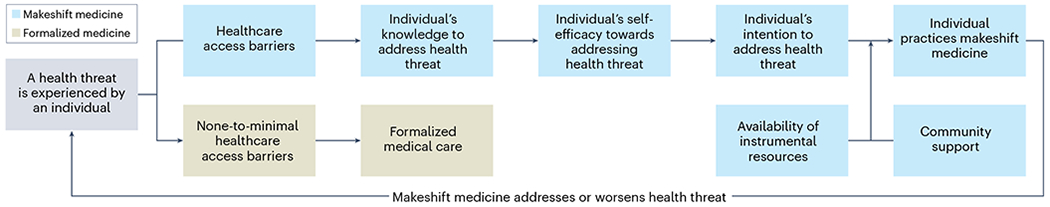

Makeshift medicine is a response to healthcare access barriers that force people into the margins of the formalized healthcare system. According to the framework (Fig. 1), several factors lead to the practice of makeshift medicine. An individual experiences a health threat and cannot access formalized healthcare. When they possess some level of knowledge to address the threat and have the self-efficacy (that is, belief in their own ability) to address the threat, they may develop the intention to address the health threat. In these circumstances, they may then address the health threat themselves using the practice of makeshift medicine. The extent to which they do this may depend also on the availability of instrumental resources (for example, medications or medical devices) and community support. The quantity, quality and other characteristics of available resources vary for individuals. Access to resources can also differentially shape the feasibility of addressing a specific health threat for each person. The nature and amount of community support that is available to individuals also affects how instrumental resources are shared. Thus, the availability of instrumental resources and community support may moderate the relationship between the intention to practice and the actual practice of makeshift medicine. Ultimately, makeshift medicine can contribute to improved or worsened health outcomes for individuals with no other means of managing their health threat.

Fig. 1|. Makeshift medicine framework.

When a health threat is experienced, healthcare access barriers affect whether formalized medical care is accessed or makeshift medicine is practiced. When healthcare access barriers are experienced and an individual possesses the knowledge to address the health threat, self-efficacy to address the threat promotes intention to address the health threat using makeshift medicine practices. The availability of instrumental resources (for example, medications or medical devices) and community support moderates the relationship between intention and the practice of makeshift medicine, which may address or worsen a health threat.

Gender-affirming care

Makeshift medicine has long been practiced by many transgender people who face systemic healthcare access barriers to accessing medically necessary care. Limited health insurance coverage for gender-affirming healthcare services, discrimination in healthcare and the paucity of knowledgeable providers who are capable of providing gender-affirming care are only some of the healthcare access barriers2. When access to gender-affirming medical care is limited, many transgender individuals are resilient in finding ways to affirm their gender through informal healthcare means5.

For many decades, an informal market for hormones and body modification has provided access to gender-affirming medical care2,5. Accessing medical forms of gender affirmation to align one’s physical presentation with one’s gender identity is important. Formalized medical gender-affirmation services are not always easily accessible or may be so exclusionary that a person does not feel comfortable accessing them. Transgender people have devised techniques to sculpt the face and body through the injection of silicone or construction-grade material when formal gender-affirming care is inaccessible5. This is a form of knowledge to address healthcare threats (Fig. 1). Although there are health benefits to medically affirming one’s gender, this makeshift medicine practice also has the potential to harm health. This is because injections are administered by nonlicensed people using health-harming substances under potentially unsanitary conditions without following proper techniques. This introduces new health threats, by increasing the potential for the acquisition of HIV or hepatitis C virus via the sharing of injection supplies. Failed procedures have led to deformity, toxicity and death2,5.

Although these practices indicate resilience against an exclusionary healthcare system and can be gender-affirming, they also can result in unintended harms. However, in the context of a transphobic and exclusionary healthcare system, people may accept the potential risks associated with makeshift medicine as the consequences of inaction (for example, gender dysphoria) could outweigh unintended harms.

Self-treatment of wounds

As with transgender people, people who inject drugs consistently experience discrimination, violence and other forms of enacted stigma when accessing healthcare services6. Stigma contributes to suboptimal healthcare experiences for people who inject drugs, which may lead to the avoidance of needed healthcare for fear of future mistreatment6. This is evident in the context of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) (a health threat), which are common among people who inject drugs and can result in adverse health consequences that include mobility impairment, uncontrolled infections, the development of infective endocarditis and sepsis, and even death if left untreated7. Recent data suggest that SSTIs are on the rise among people who inject drugs and that this surge is due in part to a rise in the use of xylazine, a veterinary sedative that is increasingly present in unregulated drugs and is associated with increased risk of SSTIs among people who use the substance8.

Research documents experiences of the self-treatment of SSTIs among people who inject drugs and lack access to stigma-free care7. People who inject drugs can recognize an infection, and relay methods to self-treat wounds to other people who inject drugs. Thus, they have the knowledge to address health threats, and community support in doing so (Fig. 1). The availability of resources is also important: when asked about specific methods used to self-treat infections, one participant reported using antibiotics obtained from an aquarium7. The concurrent rise of xylazine in the drug market and the surge in SSTIs may lead to a greater reliance on makeshift medicine practices to self-treat infections. This is particularly likely for individuals who face social and structural barriers to accessing formal medical care or choose not to engage with formalized medical care because it is perceived as highly unwelcoming6.

This case example showcases the utility of makeshift medicine in circumventing stigmatizing care experiences, while also highlighting the health-harming implications of the forced reliance on informal methods to treat wounds. Compared to the stigmatizing and even traumatic experiences that can result from attempting to access formal healthcare services, self-treating SSTIs as a makeshift medicine practice may be the preferred route for people who use drugs.

Access to abortion care

Local, state and federal policies can create healthcare access barriers. In the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling, the US Supreme Court overturned the precedent that protected the right of a person to choose to have an abortion established by the landmark Roe v. Wade decision in 1973. In the aftermath of this decision, 13 states have passed laws that make abortion illegal, with many of these states providing no exceptions even in the case of rape and incest9. Additionally, in Idaho, Oklahoma and Texas, private citizens can sue providers who perform abortions. Although some states have moved to protect access to abortion, in about half of the USA the future of abortion access is in legal jeopardy. This assault on access to necessary and lifesaving healthcare breeds conditions that propel pregnant people without access to the formal healthcare system to potentially self-manage abortions using abortifacients – the safest and most-accessible abortion-inducing medications in a post-Roe landscape. Indeed, an analysis of Google search trends in the 72 hours after the leaked draft Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision indicated that searches for abortifacient medications were 162% greater than the typical search volume for these medications9.

There is a well-documented history of self-managed abortions in the absence of accessible abortion service providers10. An unknown number of people have used an array of makeshift medicine practices to end pregnancies, including herbal and pharmaceutical concoctions, self-inflicted abdominal trauma and the insertion of objects into the uterus via the vagina (physical insertion methods are less common now because of abortifacient medications)9,10. In states in which abortions are outlawed, communities are left with no option but to care for one another. Techniques to end pregnancies – and how to minimize legal repercussions – are shared within communities. Online resources and communities have also formed to disseminate best practices for abortion self-management, and to distribute abortifacient medications to people who need them10. This means that the knowledge and resources to address health threats become more widespread, increasing the likelihood that individuals will practice makeshift medicine (Fig. 1). As in the previous examples, this case study illustrates that when ostracized from formalized medicine (in this case through the force of law), the resilience of individuals to meet their own healthcare needs will persist.

Future directions

There is an increasing focus on health disparities research and attentiveness to barriers to the healthcare system. However, there remains a dearth of empirical research on how individuals meet their healthcare needs when forced to do so outside of the formal healthcare system. The makeshift medicine framework is a step towards understanding how individuals forge their own systems of healthcare when the formalized healthcare system has abandoned them. It also provides a map to guide future empirical testing.

We need to do more to understand the context in which and dimensions of how individuals address their healthcare needs by practicing makeshift medicine. To do this, we first suggest ethnographic work with marginalized populations who lack access to the healthcare system. Such research could result in novel solutions to emergent health threats. Ethnographic methods that use intersectional analysis provide the means to be critically attentive to how oppressive actors and forces – including racism, transphobia, classism and sources of stigma (for example, injection-drug use stigma) – co-construct healthcare access barriers and contribute to the use of makeshift medicine practices. Quantitative epidemiological research is also critical to testing the makeshift medicine framework on a population level, including longitudinal survey designs to establish temporality. The field will also benefit from advanced methods, such as structural equation modelling, to describe how complex relationships between factors that push people outside the healthcare system, resources and individual-level constructs lead people to engage in makeshift medicine practices. Empirically establishing the mechanisms through which healthcare access barriers lead to the use of makeshift medicine could identify intervention targets that can be addressed in future intervention research to reduce the impact of potentially harmful makeshift medicine practices using harm reductionist approaches. This work should be pursued in tandem with efforts to improve the accessibility of the healthcare system.

In addition to empirical research, we need advocacy for public policy to address the factors that lead to makeshift medicine. Although the Affordable Care Act was a step forward in improving access to the formalized healthcare system, recent years have seen attempts (some successful and others not) to further limit access, including the overturning of Roe v. Wade and legislation to prohibit gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents. Public health and medical practitioners must call on policymakers to demand parity in access to and navigation of the healthcare environment for all people, ensuring that the conditions that necessitate the use of makeshift medicine are eliminated. Until then, people will continue to meet their own healthcare needs when pushed to the edges of medicine.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Keisler-Starkey K & Bunch LN U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-278, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2021 (US Government Publishing Office, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 2.White Hughto JM, Reisner SL & Pachankis JE Soc. Sci. Med 147, 222–231 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montori V BMJ 375, n2886 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raudenbush DT Healthcare Off the Books: Poverty, Illness, and Strategies for Survival in Urban America (Univ. California Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly PJ Commonhealth 1, 62–68 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biancarelli DL et al. Drug Alcohol Depend. 198, 80–86 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert AR, Hellman JL, Wilkes MS, Rees VW & Summers PJ Harm Reduct. J 16, 69 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander RS, Canver BR, Sue KL & Morford KL Am. J. Public Health 112, 1212–1216 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman D & Verma N J. Am. Med. Assoc 328, 1693–1694 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moseson H et al. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol 63, 87–110 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]