Abstract

During the last decade, the hns gene and its product, the H-NS protein, have been extensively studied in Escherichia coli. H-NS-like proteins seem to be widespread in gram-negative bacteria. However, unlike in E. coli and in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, little is known about their role in the physiology of those organisms. In this report, we describe the isolation of vicH, an hns-like gene in Vibrio cholerae, the etiological agent of cholera. This gene was isolated from a V. cholerae genomic library by complementation of different phenotypes associated with an hns mutation in E. coli. It encodes a 135-amino-acid protein showing approximately 50% identity with both H-NS and StpA in E. coli. Despite a low amino acid conservation in the N-terminal part, VicH is able to cross-react with anti-H-NS antibodies and to form oligomers in vitro. The vicH gene is expressed as a single gene from two promoters in tandem and is induced by cold shock. A V. cholerae wild-type strain expressing a vicHΔ92 gene lacking its 3′ end shows pleiotropic alterations with regard to mucoidy and salicin metabolism. Moreover, this strain is unable to swarm on semisolid medium. Similarly, overexpression of the vicH wild-type gene results in an alteration of swarming behavior. This suggests that VicH could be involved in the virulence process in V. cholerae, in particular by affecting flagellum biosynthesis.

In prokaryotic cells, the organization and/or the function of their chromosomal DNA require the involvement of proteins, generally small, abundant, and basic (24). H-NS, one of the most abundant DNA-binding proteins in enterobacteria, was isolated about 30 years ago as a transcription factor (25). It was later shown to be involved in the organization of bacterial chromosome by affecting the level of DNA condensation (45). Numerous phenotypes have been associated with hns mutations, resulting from a modification in the expression of several plasmid and chromosomal genes. Most of them are regulated by environmental parameters, such as pH, osmolarity, and temperature (2, 30), or are known to be involved in bacterial virulence, e.g., in Shigella flexneri (33).

H-NS exists essentially as a homodimer and binds preferentially to curved DNA in vitro (51). No information is available concerning its three-dimensional structure, except for the organization of its C-terminal domain, which has been resolved by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (39). This region is required in DNA binding, while the N-terminal region is implicated in protein-protein interactions (49, 52). H-NS synthesis is known to be negatively autoregulated and to be induced by cold shock (2).

During the past few years, the genetics of Vibrio cholerae has been extensively studied, in particular in relation with the expression of virulence factors (15, 40). In contrast, nothing is known about the existence of the so-called histone-like proteins involved in the structure and function of the chromosome in this organism. Recently, we have demonstrated that H-NS and H-NS-like proteins represent a large family of functionally and structurally related DNA-binding proteins, at least in gram-negative bacteria (5). Except for BpH3 in Bordetella pertussis (22), most of them have been identified on the basis of sequence homology. Moreover, only a few genes, including hns and stpA in Escherichia coli (2, 17, 29, 43, 54) and hvrA in Rhodobacter capsulatus (10), have been characterized. Here we describe the isolation and the characterization of vicH, an hns-like gene in V. cholerae. It constitutes the first gene isolated by complementation of hns-related phenotypes and the first hns-like gene identified among members of the family Vibrionaceae. Our results suggest that VicH has a pleiotropic role in the physiology of V. cholerae, in particular by altering expression of several genes which could play a role in pathogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

FB8 (9) and BE1410, its hns-1001 derivative (30), were used in this study. E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) was used to construct the genomic library of V. cholerae strain classical Ogawa O395. All experiments were performed in accordance with the European regulations concerning the contained use of genetically modified organisms of group I (agreement 2735) and group II (agreement 2736).

Plasmids pDIA562 and pDIA566, isolated from the V. cholerae genomic library, carry DNA fragments of 1,320 and 1,980 bp, respectively. The nucleotide sequence of each insert was determined on both strands by Genome Express (Grenoble, France). DNA fragments in pDIA562 and pDIA566 both contain the vicH gene and its flanking regions. A kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene was isolated from pUC4K (Pharmacia) after digestion by PstI and ligated to pDIA562 digested by ApaL1 and filled in by Klenow enzyme. A recombinant plasmid containing the Kmr cartridge inserted at codon 92 of the vicH gene was selected in E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene), giving rise to plasmid pDIA563. Plasmids pDIA562 and pDIA563 were introduced into the V. cholerae wild-type strain by electrotransformation as previously described (6), giving rise to strains BV1920 and BV1921, respectively.

To overproduce VicH-His6 protein, its structural gene was PCR amplified from genomic DNA by using primers 5′-CCGCTCGAGCAGAGCGAATTCTTCCAGAG-3′ and 5′-GGAGGTTCATATGTCGGAAATCACTAAGAC-3′, introducing an XhoI cloning site at its 5′ end and an NdeI cloning site at its 3′ end, respectively. PCR product was inserted into the XhoI and NdeI sites of the pET-22b vector (Novagen), giving rise to plasmid pDIA564.

E. coli and V. cholerae cells were grown at 37 and 30°C, respectively, in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in M63 medium (35) supplemented with 40 μg of serine per ml, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and 0.4% glucose as a carbon source in complementation experiments of serine susceptibility. Metabolism of β-glucosides was tested on MacConkey indicator agar plates with 1% salicin as a carbon source. Tryptone swarm plates containing 1% Bacto Tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, and 0.3% Bacto Agar were used to test bacterial motility as previously described (5). When required, the antibiotics kanamycin and chloramphenicol were added at concentrations of 25 and 20 μg/ml, respectively.

Construction of a V. cholerae genomic DNA library.

Genomic DNA was isolated from V. cholerae, and a Sau3A partial digestion was performed according to standard procedures (38). The fragments ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 kb were purified from an agarose gel by using a JETsorb kit (GENOMED). They were partially filled in with dA and dG, using Klenow enzyme, generating AG cohesive ends. Plasmid pSU19 (4) was digested by SalI and partially filled in with dC and dT, generating CT cohesive ends. Restriction fragments and plasmid DNA were ligated by T4 DNA ligase at 16°C for 15 h. The ligation mixture was introduced into E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene) by electrotransformation as previously described (6). About 60,000 independent clones were selected on LB plates and pooled. Large-scale plasmid DNA isolation was carried out with a JETstar kit (GENOMED). This genomic library was then used to transform the hns-1001 strain.

Protein purification.

Recombinant protein VicH-His6 was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) carrying pDIA564, using NiSO4 chelation columns (Qiagen) as previously described (5).

Protein-protein cross-linking.

VicH-His6 (100 μM) was equilibrated in 8 μl of buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 8), 60 mM potassium glutamate, 8 mM magnesium aspartate, 0.05% NP-40, and 2 mM dithiothreitol for 15 min at room temperature; 2 μl of cross-linking chemical reagents, i.e., 50 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 200 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), was then added to the protein mixture. The cross-linking reaction was stopped after 10, 30, or 60 min by addition of loading buffer containing 70 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 5% glycerol, 1.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 120 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue and by heating at 95°C for 5 min. The samples were loaded onto a 4 to 20% (wt/vol) gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). The gel was stained with Coomassie blue and destained with a 30% ethanol–10% acetic acid solution.

Antibodies and Western blotting.

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against H-NS according to the standard protocol (38). Briefly, two rabbits were injected subcutaneously four times with 135 μg of purified protein (44) emulsified in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 1.4 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.3) and an equal volume of Freund's incomplete adjuvant. Sera were mainly collected 3 weeks after the final injection. After 3 h at room temperature, blood was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 15 min. Supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C.

Before use, anti-H-NS antibodies were exhausted against a crude extract of hns strain; 250 ml of stationary-phase culture was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 12.5 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and bacterial cells were disrupted by ultrasonic treatment. Anti-H-NS antibodies were diluted 600-fold in 6.25 ml of crude extract two times diluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and put on ice for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and the volume was adjusted to a 1,000-fold final dilution of antibodies in Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl) containing 5% nonfat dried milk powder.

To prepare bacterial extracts of E. coli, V. cholerae, and Bordetella bronchiseptica, cells were grown in LB medium to stationary phase; 2 ml of culture was centrifuged and resuspended in 200 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Bacterial cells were disrupted by sonication and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g. Proteins were quantified as previously described (8). After boiling of the samples, 20 μg of each protein extract was separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide (14%) Prosieve 50 (FMC) gel using Tris-glycine running buffer (25 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.3], 41 mM glycine, 1.3% SDS). The gel was then placed on a nitrocellulose membrane underlaid with one Whatman 3MM filter soaked in buffer A (25 mM Tris in 20% methanol). Below this filter were placed two filters soaked in buffer B (300 mM Tris in 20% methanol). Three filters soaked in buffer C (25 mM Tris–40 mM ɛ-amino-n-caproic acid in 20% methanol) were put above the gel. Proteins were transferred to the membrane at 250 mA for 20 min using a semidry transfer apparatus.

After incubation in the anti-H-NS antibody mixture (see above) for 15 h at 4°C, the nitrocellulose membrane was washed 10 times rapidly and three times for 10 min in Tris-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dried milk. The immune complex was detected with anti-rabbit immunoglobulins conjugated to peroxidase, using an Amersham ECL detection kit according to the manufacturer.

Sequence analysis.

The MULTALIGN method (11) was used for sequence alignments and refined manually as previously described (5). Prediction of antigenic determinants was performed by different methods contained in the MacVector 6.5 package such as hydrophilicity analysis (Kyte-Doolittle, Hopp-Woods, and von Heijne scales), antigenicity prediction (Parker, protrusion index, and Welling scales), and surface probability determination (Janin and Ermini profiles).

Preparation and analysis of RNAs.

Total RNAs were extracted from 4 ml of culture grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4 to 0.5, using a High Pure RNA isolation kit (Boehringer Mannheim). RNA concentration and purity were determined by OD260 and OD280 measurements. Quantitative determination of mRNA was performed from 300 ng of RNAs by slot blotting as previously described (44). In Northern blot experiments, RNAs were transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham) according to standard procedures (38). A 430-bp DNA probe was generated by PCR amplification using oligonucleotides 5′-CGGGATCCTATCATTTTAGTTTCTGGC-3′ and 5′-ATGTCGGAAATCACTAAGAC-3′ and a PCR DIG Probe synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim) as instructed by the manufacturer. In both experiments, hybridization of the digoxigenin-labeled probe and detection were performed with the CSPD chemiluminescence detection system (Boehringer Mannheim) as previously described (44).

Primer extension analysis.

The primer extension reaction was performed as previously described (44), using 50 μg of total RNAs and oligonucleotide 5′-GGGGTACCAGGGCTAATTTCGCTTCTTGCT-3′ located around 150 bp downstream of the ATG translational initiation codon. This oligonucleotide was end labeled with phage T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) according to standard procedures (38). As a reference, sequencing reactions were performed with a ThermoSequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham) with the same primer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence shown in Fig. 6 has been assigned GenBank accession no. AJ010791.

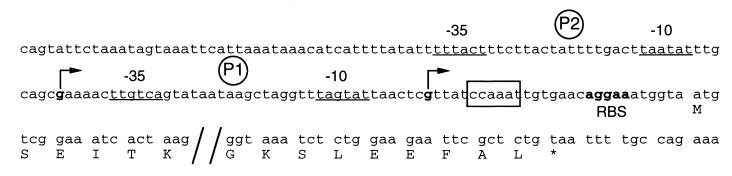

FIG. 6.

Promoter region of the vicH gene. Transcriptional start sites are indicated by bent arrows; proximal and distal promoters relative to the ATG translational codon are indicated by P1 and P2, respectively. Positions of the −10 and −35 sequences are underlined. The putative cold box and putative ribosome-binding site (RBS) are boxed and in boldface, respectively. Only the residues corresponding to the N- and the C-terminal parts of VicH are indicated.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the vicH gene.

High susceptibility to serine in minimal medium is one of the numerous phenotypes associated with hns mutations in E. coli (5). To isolate a putative hns-like gene in V. cholerae, we constructed a genomic library of Sau3A-digested V. cholerae chromosomal DNA (see Materials and Methods). This library was introduced into the BE1410 hns strain by electrotransformation, and selection was performed on plates containing minimal medium supplemented with 40 μg of serine per ml. Numerous clones were obtained after incubation at 37°C for 48 h. One hundred clones were purified on the same medium and tested for two additional hns-related phenotypes, i.e., loss of motility on semisolid medium (7) and use of salicin as a carbon source (13). In addition to serine susceptibility, most of them showed an alteration in both swarming and β-glucoside metabolism. Analysis of restriction fragments from the plasmid DNA of 36 clones allowed us to isolate plasmids pDIA562 and pDIA566, carrying 1,320- and 1,980-bp DNA fragments, respectively. In the presence of each plasmid, a wild-type phenotype was restored in the hns mutant with regard to motility, β-glucoside utilization, and mucoidy (Table 1). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence revealed the presence in both inserts of a complete coding sequence (CDS) of 405 bp encoding a protein of 135 amino acids with predicted molecular mass of 14,931 kDa and pI of 5.26. This putative protein, VicH (for V. cholerae H-NS-like protein), showed approximately 50% identity with E. coli H-NS and StpA proteins (Fig. 1). Sequence determination of the region upstream from vicH revealed the presence in the opposite orientation of a partial CDS starting 693 bp from the VicH ATG start codon (data not shown). This CDS encodes a putative protein which presents a significant similarity with the hypothetical integral membrane protein HI1586 present close to hns in Haemophilus influenzae (16). In contrast, sequence determination of the 250-bp region downstream of the vicH CDS revealed no significant similarity with any known gene (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Analysis of various phenotypes in E. coli and V. cholerae expressing wild-type and/or truncated form of vicH

| Strain (relevant genotype) | Phenotype

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motilitya | β-Glucoside utilizationb | Mucoidyc | |

| E. coli | |||

| FB8 (wild type) | + | W | − |

| BE1410 (hns-1001) | − | R | + |

| BE1410/pDIA562d | + | W | − |

| BE1410/pDIA563 | − | R | + |

| V. cholerae | |||

| Classical O395 (wild type) | + | W | − |

| BV1921 (O395/pDIA563) | − | P | +/− |

+, motility revealed by the appearance of a swarming ring on semisolid medium; −, no motility.

R, β-glucoside metabolism revealed by the appearance of red colonies on MacConkey-salicin agar plates; W, no metabolism by white colonies; P, intermediate metabolism by pink colonies.

+, mucoid phenotype observed on MacConkey-salicin agar plates; −, no mucoid phenotype; +/−, intermediate phenotype.

Similar results were obtained with plasmid pDIA566.

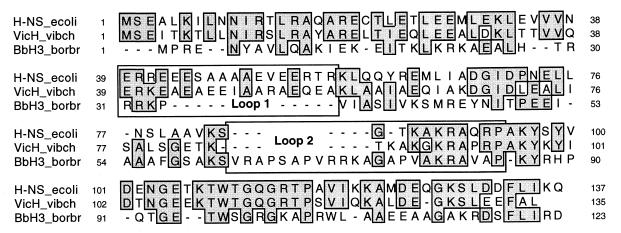

FIG. 1.

Structurally based alignment of V. cholerae VicH and B. bronchiseptica BbH3 sequences with the H-NS sequence of E. coli (37). The alignment was achieved using both MULTALIGN (11) and HCA (31) plots as previously described (5). Residues conserved in at least two sequences are in gray boxes.

To confirm that the reversion of hns-related phenotypes observed in the E. coli mutant strain resulted from vicH expression, this gene was disrupted in pDIA562 by inserting a Kmr gene upstream from the DNA-binding domain of the putative protein, i.e., between codons 91 and 92, giving rise to plasmid pDIA563. Compared with plasmid pDIA562 expressing vicH, plasmid pDIA563 had no effect on serine susceptibility, loss of motility, and β-glucoside utilization in the hns strain (Table 1). This provides evidence that the vicH gene itself is responsible for the reversion of hns-related phenotypes that we observed (Table 1).

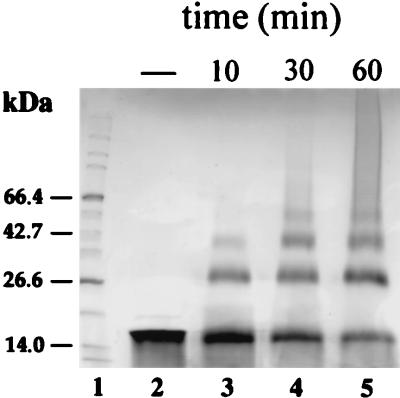

Structural organization of the vicH gene product.

The VicH protein sequence was aligned with those of H-NS and BbH3 (GenBank accession no. AJ006983), an H-NS-like protein that we recently isolated from B. bronchiseptica by the same procedure (data not shown). This protein is homologous to BpH3 previously isolated from B. pertussis by Southwestern blot techniques (22). As pointed out for other H-NS-like proteins so far characterized such as StpA in E. coli and HvrA in R. capsulatus (5, 12), the C-terminal third was highly conserved between H-NS, BbH3, and VicH (Fig. 1). Amino acid conservation in the remaining part of these three proteins was less prominent. However, the N-terminal domain has been demonstrated to play an important role in the dimerization process of H-NS and various H-NS-like proteins (5, 49, 52). Moreover, the oligomeric structure of the protein has been suggested to be required for its specific binding to DNA (46). This prompted us to analyze the ability of VicH to oligomerize in vitro by cross-linking experiments in the presence of chemical cross-linking reagents EDC and NHS (23). A time course experiment showed that VicH is able to form dimers, trimers, and tetramers in vitro (Fig. 2). Moreover, the presence of a smeared band at the top of the gel after 60 min of incubation suggests the formation of higher-order aggregates.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of in vitro protein-protein interactions by chemical cross-linking. VicH protein (100 μM) was incubated as described in Materials and Methods without any reagent (lane 2) or with EDC and NHS for 10, 30, and 60 min (lane 3 to 5, respectively) prior to quenching with β-mercaptoethanol and loading onto a 4 to 20% (wt/vol) gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis for 1 h at 120 V, the gel was Coomassie blue stained. Lane 1, molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad).

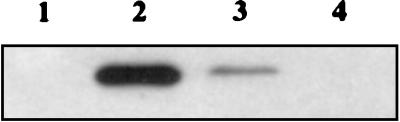

The major differences between H-NS, VicH, and BbH3 concerned two regions rich in charged amino acids. They were recently shown to contain protease cleavage sites in H-NS and/or StpA (12) and were predicted as putative loops in H-NS-like proteins (5). This suggests that these domains (Fig. 1) could be exposed to the surface in the folded structure of H-NS-like proteins. Therefore, the amino acid sequences of the three proteins were analyzed by different methods of antigenicity or hydrophilicity prediction and of surface probability determination (see Materials and Methods). Unlike the case for BbH3, we observed two major peaks centered around residues A45 and G89 in VicH (around residues S45 and A88 in H-NS) (data not shown). This suggests that the regions encompassing loops 1 and 2 constitute major antigenic sites, at least in VicH and H-NS. In both loops, the amino acid sequence was, at least in part, conserved between VicH and H-NS. In contrast, loop 1 was restricted to only a few residues in BbH3, while loop 2 was longer in BbH3 than in VicH and in H-NS. To determine whether the structural organization in VicH could result in antigenic properties different from those in H-NS and in BbH3, we performed Western blot experiments on E. coli, V. cholerae, and B. bronchiseptica protein extracts, using antibodies raised against H-NS. No cross-reactivity was observed with the BbH3 protein of B. bronchiseptica (Fig. 3). In contrast, the VicH protein of V. cholerae was recognized by the anti-H-NS antibodies but to a lower extent compared with H-NS. This suggests that major epitopes present in H-NS are, at least in part, conserved in VicH.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of H-NS and H-NS-like proteins in E. coli, V. cholerae, and B. bronchiseptica. Total protein extracts (20 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel (14%) electrophoresis, transferred to a nitrocellulose filter, and reacted with antibodies raised against H-NS (sera diluted 1/1,000). Lane 1, E. coli (BE1410 hns-1001); lane 2, E. coli (FB8, wild type); lane 3, V. cholerae (O395, wild type); lane 4, B. bronchiseptica (BB973, wild type).

Transcriptional analysis of vicH.

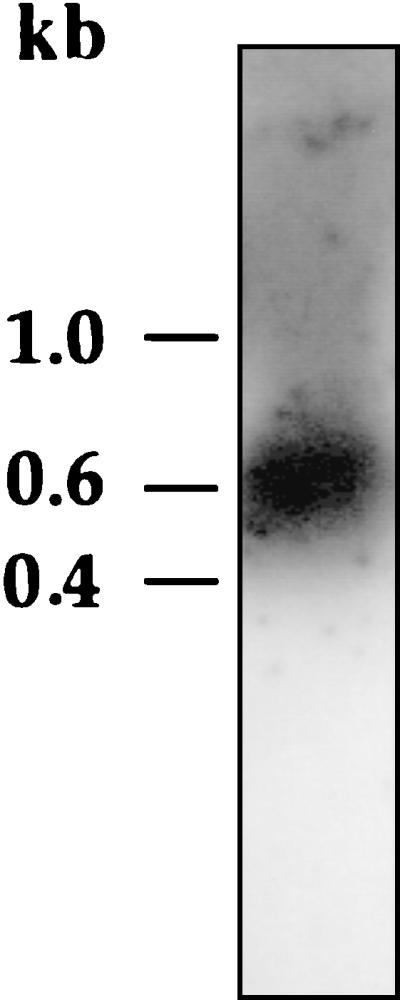

To know whether vicH was expressed as a single gene like hns in E. coli (21) or as part of an operon like hvrA in R. capsulatus (10), we analyzed in vivo transcripts by Northern blotting (Fig. 4). Although we cannot rule out any processing of a longer transcript, the presence of mRNA with an apparent size of about 600 bases in RNAs extracts suggests that vicH does not form an operon with any other gene in V. cholerae.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of vicH mRNA. Total RNAs were extracted from wild-type strain (O395 classical Ogawa) of V. cholerae as described in Materials and Methods. A 430-base probe specific to the vicH gene revealed the presence of transcripts with an apparent size of about 600 bases.

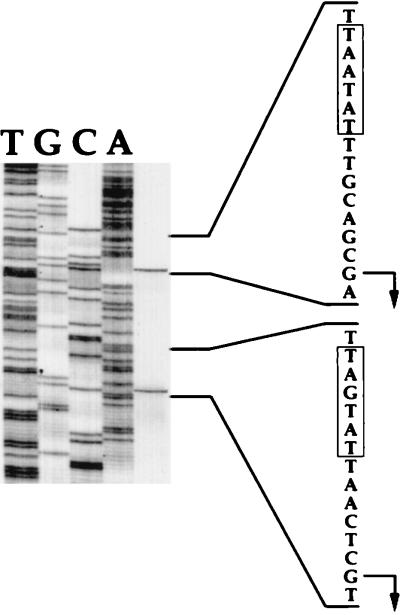

Primer extension analysis were performed to determine transcriptional start sites. Two major bands for transcription initiation were detected (Fig. 5), which indicates that transcription of vicH could arise from two G residues located 29 and 70 nucleotides, respectively, upstream from the ATG translational start codon (Fig. 6). Upstream from the distal transcriptional start site, −35 and −10 hexamers showing 67% similarity with the ς70 consensus in E. coli were identified. Upstream from the proximal +1 site, −35 and −10 hexamers showing 83 and 67%, respectively, similarity with the ς70 consensus were identified. In both cases, the two boxes are separated by a 17-bp spacer (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

Identification of the vicH transcriptional start site. Primer extension analysis was performed with total RNA extracted from a V. cholerae wild-type strain grown in LB at 30°C. As a reference, a DNA sequencing ladder is shown (lanes T, G, C, and A). The sequence is complementary to the strand shown to the right and was obtained with the same primer as that used for primer extension. The −10 boxes and transcription start points (+1) are indicated by a bracket and bent arrows, respectively.

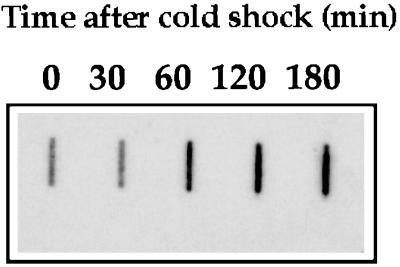

A motif, CCAAAT, reminiscent to the Y box recognized by nucleic acid-binding proteins (53) was identified 5 bp downstream from the proximal +1 site relative to the ATG start codon (Fig. 6). The precise role of this motif in the transcriptional control of cold shock-regulated genes, e.g., cspA, remains to be determined (20). However, such a motif has also been identified upstream from the coding sequence of H-NS (29). As this regulatory protein is known to belong to the cold shock regulon in E. coli (47), it was of interest to determine whether vicH expression was also regulated by a shift to low temperature. V. cholerae was grown at 30°C to mid-log phase, and the culture was then shifted to 10°C. Three-milliliter aliquots of culture were removed before and at various times after the temperature shift. Total RNAs were prepared, and 300-ng aliquots were analyzed by slot blotting. The temperature shift from 30°C to 10°C resulted in a threefold increase in vicH mRNA synthesis (Fig. 7), in agreement with previous results for hns in E. coli (29). Primer extension analysis revealed a similar increase in transcription from both promoters after cold shock (data not shown), suggesting that a shift to low temperature results in a global increase in vicH expression rather than in a differential rate of transcription initiation between the two promoters.

FIG. 7.

Effect of cold shock on vicH mRNA synthesis. Transcript level was analyzed in the V. cholerae wild-type strain by slot blot hybridization using a 430-base probe specific to the vicH gene. Cells were grown in LB at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.7 and then shifted to 10°C. Samples were withdrawn for RNA extraction at various times between 0 and 3 h after the temperature shift. Quantitation was performed with the Bio-Rad Multi-Analyst system.

Pleiotropic role of vicH in V. cholerae.

Attempts to construct a vicH null mutant by allelic exchange have so far been unsuccessful (data not shown). Similar failures to disrupt or delete hns-like genes have been recently reported for B. pertussis (22) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (50). Nevertheless, it has been recently demonstrated that synthesis in a wild-type E. coli strain of truncated forms of H-NS, in particular those lacking their DNA-binding domain, can lead to phenotypes reminiscent to those observed in an hns mutant (48, 51). Therefore, to investigate the role of VicH, we introduced plasmid pDIA563, expressing a vicHΔ92 gene, into a V. cholerae wild-type strain, giving rise to strain BV1921.

We tested the effect of the vicHΔ92 gene expression on various hns-related phenotypes, i.e., ability to use β-glucosides and mucoidy. While the V. cholerae wild-type strain was unable to use salicin as a carbon source (Table 1), expression of the vicHΔ92 gene in BV1921 strain resulted in the appearance of pink and mucoid colonies on MacConkey-salicin agar plates. These observations suggest that V. cholerae possesses a silent system allowing transport and metabolism of β-glucosides as well as an operon required in the synthesis of capsular exopolysaccharides.

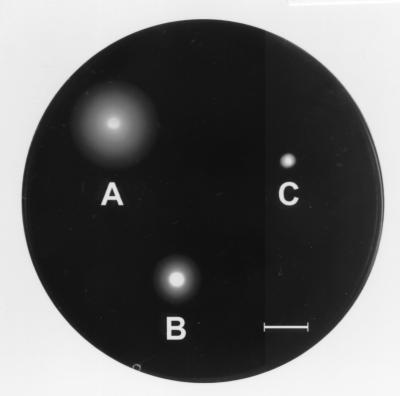

Among the various phenotypes associated with hns mutations, motility is one of the few processes known to be positively controlled by H-NS in E. coli (7, 44). Expression of the truncated form of vicH resulted, in V. cholerae, in loss of motility on semisolid medium (Table 1 and Fig. 8). Similarly, overexpression in trans of the vicH wild-type gene in V. cholerae BV1920 resulted in a strong reduction of motility (Fig. 8). This finding further supports the gene dosage effect associated with H-NS and H-NS-like overproduction reported in E. coli (3, 22, 34).

FIG. 8.

Motility assay on semisolid medium. (A) O395 classical Ogawa wild-type strain; (B) BV1920 (O395/pDIA562); (C) BV1921 (O395/pDIA563). Plasmids pDIA562 and pDIA563 express vicH and vicHΔ92 genes, respectively. The results are representative of three independent experiments. The bar represents 10 mm.

DISCUSSION

To survive under a wide range of detrimental conditions, bacteria have to constantly monitor environmental parameters and rapidly adapt their structure and physiology. These processes are based on the existence of multiple regulatory networks in which genes are regulated in a coordinate manner in response to environmental factors, such as temperature, osmolarity, or pH. In E. coli, numerous genes involved in adaptation to environmental challenges or in virulence are controlled by DNA-binding proteins, such as HU, integration host factor, H-NS, and FIS (24). In V. cholerae, the etiologic agent of the human diarrheal disease cholera, little is known about the presence of such a DNA-binding protein. In this report, we describe the characterization of vicH, a V. cholerae gene coding for a protein of the H-NS family.

Our results demonstrate that the amount of vicH mRNA in V. cholerae was increased threefold after cold shock (Fig. 7), suggesting that VicH could belong to a cold shock regulon in this organism. Moreover, analysis of transcripts by Northern blotting (Fig. 4) as well as the lack of any similarly oriented CDS close to vicH (see below) demonstrated that this gene is not part of an operon like hvrA in R. capsulatus (10) but expressed as a single gene like hns in E. coli (21). In contrast, the presence of two promoters in the vicH regulatory region (Fig. 5) could be the basis of a fine-tuning of its expression under specific environmental conditions. Examination of the unfinished V. cholerae genome from the Institute for Genome Research (TIGR) website (http://www.tigr.org/cgi-bin/BlastSearch /blast.cgi?) suggests that a gene homologous to vicH exists in El Tor N16961. However, the region downstream of vicH in V. cholerae classical Ogawa O395 strain was not similar to that in El Tor N16961 (data not shown). On the other hand, upstream from vicH in both organisms, we identified a partial CDS coding for a putative membrane protein showing a significant similarity with HI1586, a hypothetical membrane protein identified upstream from hns in H. influenzae. In contrast, no gene homologous to this putative membrane protein was identified close to the hns locus in E. coli. This provides evidence that the genetic organization of the hns or hns-like locus is not entirely conserved, even among closely related gram-negative bacteria.

The major structural difference between VicH, H-NS, and BbH3 is at the N-terminus, in particular the two regions previously predicted as loops in H-NS-like proteins (5). Unlike BbH3, these two domains are partly conserved in VicH in comparison with H-NS (Fig. 1). The cross-reactivity observed between VicH and anti-H-NS antibodies supports the presence of conserved epitopes in both proteins. By in silico analysis, loops 1 and 2 were predicted as major antigenic sites in both proteins. Moreover, these regions have been recently identified as protease sensitive in H-NS and/or StpA (12). This suggests that amino acids in both loops could play an important role in the immunoreactivity of VicH and H-NS, due to their exposure to the surface in both proteins, and supports a close structural relationship between VicH and H-NS. Despite a low amino acid conservation in the N-terminal domain of H-NS-like proteins, this region has been suggested to play a key role in protein-protein interactions (5, 49, 52). In particular, H-NS has been shown to form oligomers, i.e., essentially dimers but also small amount of trimers and tetramers, depending on the protein concentration (14). Moreover, it has been suggested that repression by H-NS could involve a polymerization step of the protein along the DNA and that the ability of this protein to recognize curved DNA and/or to bend it depends on its oligomeric state (46, 49). The propensity of VicH to form oligomers in vitro (Fig. 2) suggests that such a cooperative mode of binding to DNA is widespread in H-NS-like proteins. This further supports an essential role of this DNA-binding property in the function of these proteins.

In E. coli, the formation of hybrid proteins between wild-type H-NS and mutant proteins has been proposed to give rise to species with altered properties, especially with regard to DNA binding (48, 49, 52). In the presence of a plasmid expressing a truncated form of vicH, several phenotypic alterations, such as mucoidy and salicin metabolism, were observed in V. cholerae BV1921 (Table 1). In E. coli hns mutants, similar phenotypes result from the derepression of capsular exopolysaccharide synthesis and of β-glucoside utilization as a carbon source (2). Mucoidy observed in V. cholerae BV1921 suggests the existence of an operon involved in the synthesis of colanic acid and homologous to the H-NS-regulated cps operon in E. coli (41). In this organism, one function for colanic acid might be to protect it from environmental assaults that damage or perturb the outer membrane (42). In addition, the effect of the vicHΔ92 gene expression on salicin metabolism revealed the existence of an uncharacterized operon in V. cholerae which could be homologous to the bglGFB operon repressed by H-NS in E. coli (13). Examination of the unfinished V. cholerae genome from the TIGR website further supports the existence in V. cholerae of genes showing more than 50% identity with bgl and cps genes (data not shown). Moreover, our results suggest a key role of VicH in the negative control of these operons expression (Table 1). Finally, the lack of expression under laboratory conditions of the bgl-like operon in V. cholerae suggests that, rather than cryptic, bglGFB could be specifically induced in the host environment, as recently demonstrated in E. coli infecting mouse liver, suggesting a role of this operon in the infection process (26).

The V. cholerae BV1920 strain overexpressing the vicH gene and the BV1921 strain expressing the truncated vicHΔ92 gene showed a strong reduction in motility on semisolid medium (Fig. 8). Preliminary experiments suggest that this alteration of swarming behavior results from a decrease in the level of flagellin flaA mRNA (C. Tendeng, unpublished data). In V. cholerae, motility depends on the presence of a single polar flagellum instead of several peritrichous flagella as in E. coli (32). Moreover, unlike in E. coli, five flagellin subunits have been recently identified in V. cholerae, among which only FlaA seems to be essential for flagellar synthesis (28). Finally, the flaA gene is transcribed by the ς54 holoenzyme form of RNA polymerase, unlike the fliC gene in E. coli. Despite these differences between the two organisms, our results suggest that VicH is involved, like H-NS in E. coli (7), in the positive control of flagellum synthesis in V. cholerae. The VicH protein, in particular by controlling the synthesis of bacterial components such as flagella frequently associated with the virulence process in various microorganisms (1, 18, 19, 27, 36), could play a role in the pathogenicity of V. cholerae. Furthermore, our results suggest that the function of H-NS-like proteins is, at least in part, evolutionarily conserved in gram-negative bacteria, despite differences in genetic and functional organization of their target genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to C. Parsot for providing V. cholerae O395, to I. Martin and O. Soutourina for critical reading of the manuscript, to N. Benhabiles and I. Moszer for helpful advice, and to C. Laurent-Winter, P. Dumont, and Laetitia Genet for technical assistance.

Financial support came from the Institut Pasteur and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (URA 1129 and URA 1773) and from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie (Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie et Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires). C.T. and C.B. were supported by MESR grants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akerley B J, Cotter P A, Miller J F. Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella-host interaction. Cell. 1995;80:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr G C, Bhriain N N, Dorman C J. Identification of two new genetically active regions associated with the osmZ locus of Escherichia coli: role in regulation of proU expression and mutagenic effect at cya, the structural gene for adenylate cyclase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:998–1006. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.998-1006.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartolomé B, Jubete Y, Martinez E, de la Cruz F. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene. 1991;102:75–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90541-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertin P, Benhabiles N, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Tendeng C, Turlin E, Thomas A, Danchin A, Brasseur R. The structural and functional organization of H-NS-like proteins is evolutionarily conserved in Gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:319–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertin P, Lejeune P, Colson C, Danchin A. Mutations in bglY, the structural gene for the DNA-binding protein H1 of Escherichia coli, increase the expression of the kanamycin resistance gene carried by plasmid pGR71. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:184–192. doi: 10.1007/BF00587578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertin P, Terao E, Lee E H, Lejeune P, Colson C, Danchin A, Collatz E. The H-NS protein is involved in the biogenesis of flagella in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5537–5540. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5537-5540.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruni C B, Colantuoni V, Sbordone L, Cortese R, Blasi F. Biochemical and regulatory properties of Escherichia coli K-12 his mutants. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:4–10. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.4-10.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buggy J J, Sganga M W, Bauer C E. Characterization of a light-responding trans-activator responsible for differentially controlling reaction center and light-harvesting-I gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6936–6943. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6936-6943.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cusick M E, Belfort M. Domain structure and RNA annealing activity of the Escherichia coli regulatory protein StpA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:847–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Defez R, De Felice M. Cryptic operon for β-glucoside metabolism in Escherichia coli K12: genetics evidence for a regulatory protein. Genetics. 1981;97:11–25. doi: 10.1093/genetics/97.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falconi M, Gualtieri M T, La Teana A, Losso M A, Pon C L. Proteins from the procaryotic nucleoid: primary and quaternary structure of the 15-kD Escherichia coli DNA binding protein H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faruque S M, Albert M J, Mekalanos J J. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1301–1314. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1301-1314.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, Fitzhugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Free A, Dorman C J. The Escherichia coli stpA gene is transiently expressed during growth in rich medium and is induced in minimal medium and by stress conditions. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:909–918. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.909-918.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardel C L, Mekalanos J J. Alterations in Vibrio cholerae motility phenotypes correlate with changes in virulence factor expression. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2246–2255. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2246-2255.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Givaudan A, Lanois A. flhDC, the flagellar master operon of Xenorhabdus nematophilus: requirement for motility, lipolysis, extracellular hemolysis, and full virulence in insects. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:107–115. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.107-115.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenberg D, Azar I, Oppenheim A B, Brandi A, Pon C L, Gualerzi C O. Role of Escherichia coli cspA promoter sequences and adaptation of translational apparatus in the cold shock response. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:282–290. doi: 10.1007/s004380050571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Göransson M, Sondén B, Nilsson P, Dagberg B, Forsman K, Emanuelsson K, Uhlin B E. Transcriptional silencing and thermoregulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1990;344:682–685. doi: 10.1038/344682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goyard S, Bertin P. Characterization of BpH3, an H-NS like protein in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:815–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3891753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grabarek Z, Gergely J. Zero-length crosslinking procedure with the use of active esters. Anal Biochem. 1990;185:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90267-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayat M A, Mancarella D A. Nucleoid proteins. Micron. 1995;26:461–480. doi: 10.1016/0968-4328(95)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacquet M, Cukier-Kahn R, Pla J, Gros F. A thermostable protein factor acting on in vitro DNA transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;45:1597–1607. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan M A, Isaacson R E. In vivo expression of the β-glucoside (bgl) operon of Escherichia coli occurs in mouse liver. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4746–4749. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4746-4749.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J S, Chang J H, Chung S I, Yum J S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the Helicobacter pylori fliD gene, an essential factor in flagellar structure and motility. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6969–6976. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.22.6969-6976.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Differential regulation of multiple flagellins in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:303–316. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.303-316.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.La Teana A, Brandi A, Falconi M, Spurio R, Pon C L, Gualerzi C O. Identification of a cold shock transcriptional enhancer of the Escherichia coli gene encoding nucleoid protein H-NS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10907–10911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurent-Winter C, Ngo S, Danchin A, Bertin P. Role of Escherichia coli histone-like nucleoid-structuring protein in bacterial metabolism and stress response. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:767–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemesle-Varloot L, Henrissat B, Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Morgat A, Mornon J P. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: procedures to derive structural and functional information from 2-D-representation of protein sequences. Biochimie. 1990;72:555–574. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macnab R M. Flagella and motility. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maurelli A T, Sansonetti P J. Identification of a chromosomal gene controlling temperature-regulated expression of Shigella virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2820–2824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.May G, Dersch P, Haardt M, Middendorf A, Bremer E. The osmZ (bglY) gene encodes the DNA-binding protein H-NS (H1a), a component of the Escherichia coli K12 nucleoid. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:81–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00259454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milton D L, O'Toole R, Hörstedt P, Wolf-Watz H. Flagellin A is essential for the virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1310–1319. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1310-1319.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pon C L, Calogero R A, Gualerzi C O. Identification, cloning, nucleotide sequence and chromosomal map location of hns, the structural gene for Escherichia coli DNA-binding protein H-NS. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:199–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00334684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shindo H, Iwaki T, Ieda R, Kurumizaka H, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Kuboniwa H. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of a nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS, from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00079-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skorupski K, Taylor R K. Control of the ToxR virulence regulon in Vibrio cholerae by environmental stimuli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1003–1009. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5481909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sledjeski D, Gottesman S. A small RNA acts as an antisilencer of H-NS-silenced rcsA gene of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2003–2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sledjeski D D, Gottesman S. Osmotic shock induction of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1204–1206. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1204-1206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sondén B, Uhlin B E. Coordinated and differential expression of histone-like proteins in Escherichia coli: regulation and function of the H-NS analog StpA. EMBO J. 1996;15:4970–4980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soutourina O, Kolb A, Krin E, Laurent-Winter C, Rimsky S, Danchin A, Bertin P. Multiple control of flagellum biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: role of H-NS protein and the cyclic AMP-catabolite activator protein complex in transcription of the flhDC master operon. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7500–7508. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7500-7508.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spassky A, Rimsky S, Garreau H, Buc H. H1a, an E. coli DNA-binding protein which accumulates in stationary phase, strongly compacts DNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5321–5340. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spurio R, Falconi M, Brandi A, Pon C L, Gualerzi C O. The oligomeric structure of nucleoid protein H-NS is necessary for recognition of intrinsically curved DNA and for DNA bending. EMBO J. 1997;16:1795–1805. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thieringer H A, Jones P G, Inouye M. Cold shock and adaptation. Bioessays. 1998;20:49–57. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199801)20:1<49::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ueguchi C, Seto C, Suzuki T, Mizuno T. Clarification of the dimerization domain and its functional significance for the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:145–151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueguchi C, Suzuki T, Yoshida T, Tanaka K, Mizuno T. Systematic mutational analysis revealing the functional domain organization of Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J Mol Biol. 1996;263:149–162. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ussery D W, Hinton J C D, Jordi B J A M, Granum P E, Seirafi A, Stephen R J, Tupper A E, Berridge G, Sidebotham J M, Higgins C F. The chromatin-associated protein H-NS. Biochimie. 1994;76:968–980. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams R M, Rimsky S. Molecular aspects of the E. coli nucleoid protein, H-NS: a central controller of gene regulatory networks. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams R M, Rimsky S, Buc H. Probing the structure, function and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins using dominant negative derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4335–4343. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4335-4343.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolffe A P, Tafuri S, Ranjan M, Familari M. The Y-box factors: a family of nucleic acid binding proteins conserved from Escherichia coli to man. New Biol. 1992;4:290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang A, Rimsky S, Reaban M E, Buc H, Belfort M. Escherichia coli protein analogs StpA and H-NS: regulatory loops, similar and disparate effects on nucleic acid dynamics. EMBO J. 1996;15:1340–1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]