Abstract

Emergency medicine training is associated with high levels of stress and burnout, which were exacerbated by the COVID‐19 pandemic. The pandemic further exposed a mismatch between trainees' mental health needs and timely support services; therefore, the objective of our innovation was to create an opportunity for residents to access a social worker who could provide consistent coaching. The residency leadership team partnered with our graduate medical education (GME) office to identify a clinical social worker and professionally‐trained coach to lead sessions. The project was budgeted at an initial cost of $15,000 over 1 year. Residents participated in 49 group and 73 individual sessions. Post implementation in 2021, we compared this intervention to all other wellness initiatives. Resident response rate was 80.88% (n = 55/68) and median interquartile range (IQR) score of the initiative was 2 (1 = detrimental and 4 = beneficial) versus 3.79 (3.69–3.88) the median IQR of all wellness initiatives. A notable number, 22%, rated the program as detrimental, which could be related to summary comments regarding ability to attend sessions, lack of session structure, loss of personal/educational time, and capacity of the social worker to relate with them. Summary comments also revealed the innovation was useful, with individual sessions preferred to group sessions. Application of a social worker coaching program in an emergency medicine residency program appears to be a feasible novel intervention. Lessons learned after implementation include the importance of recruiting someone with emergency department/GME experience, orienting them to culture before implementation and framing coaching as an integrated residency resource.

1. INTRODUCTION

Emergency medicine residency training is associated with high levels of stress and burnout, which have been exacerbated by the COVID‐19 pandemic. 1 Accessing counseling and supportive services to mitigate burnout can be difficult to arrange on an emergent, urgent, or continual basis. Burnout is extremely common in emergency medicine residents, with 76.1% of participants meeting criteria in a recent national study by Lin et al 2 Subsequent studies found an increase in depressive symptoms and post‐traumatic stress disorder among emergency staff during the COVID‐19 pandemic, even referring to it as a “psychological pandemic.” 3 , 4 This pandemic exposed the mismatch between trainee mental health needs and their access to support services. Emergency medicine residency training typically places residents away from their customary psychosocial support system, while injecting potentially traumatizing encounters and sleep‐wake disruptions to their lives. The shift‐based emergency medicine training model further limits and complicates access to emergent, urgent, or continual psychosocial care and services. We postulate that trainees need just‐in‐time, easily accessible resources that can support them before mental health concerns arise

2. PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

Our residency is a 4‐year program with 68 total residents based at an urban, safety‐net hospital with an adult Level I and pediatric Level II trauma center. The objective of our innovation was to support an opportunity for our residents to work with a professional coach who could provide counseling on an emergent, urgent, or regular basis to assist with 5 goals:

Find meaning in work and home life.

Allow residents a safe space to debrief and work through concerns.

Support tools that foster success in work, relationships, and future careers.

Create an environment safe to express concerns among peers and professionals.

Promote well‐being and support.

Residency leadership observed suboptimal access to regular psychosocial services approximately 1.5 years before the pandemic. The pandemic thrust this concern to the forefront for the residency and graduate medical education (GME) leadership teams.

Following a traditional interview process, the team identified a clinical social worker and professionally trained coach to engage with the residents. All meetings were paid for out of the residency/departmental budget, a cost of $15,000 for the initial year of the project. The clinical social worker set up group and individual sessions with the residents and met with residency leadership and chief residents to understand common residency themes and pressure points. Chief residents piloted sessions with the clinical social worker before the deployment to all residents. It was anticipated that each group would vary based upon the participants' needs and expressed concerns. Therefore, curricular components would have some general themes but would be particular to each group as they developed. Occasionally, a group could request additional facilitation from other experts. As best as possible, these requests would be made with lead time in order to secure the presence of these facilitators to benefit the group. When appropriate, the social worker could make individual referrals for additional mental health assessment available through other organizational channels. The group and individual sessions were intended to fill the gap between the day‐to‐day problems residents face and engagement in therapeutic assessment and intervention.

Confidentiality was imperative. It was agreed that what was shared in an individual session would not be shared without consent of the resident. Likewise, the content of each group discussion was to remain confidential apart from periods when it was the consensus of the group that something needed to be shared with program leadership. General themes of interest to leadership that arose in group meetings were shared anonymously by the facilitator. This allowed leadership to anticipate general themes and concerns within the residency, as well as opportunities for intervention and follow‐up. The legal limits to confidentiality were followed, which included mandatory reporting of any threats made around harm to self or others, as well as the divulging of abuse. It was agreed upon a priori that in these circumstances, the program director would be contacted as well as the appropriate resources for referral and assessment.

In order for each resident in the program to connect with the social worker, a total of 12 one‐hour‐long small group sessions with approximately 6 residents each were arranged, beginning on October 1, 2020. Individual coaching sessions were begun shortly thereafter on a request basis. The overall structure of the program was organized as follows:

-

‐

Small Group Sessions:

-

‐

First Wednesday: 9–10am (6 interns), 10–11am (6 interns), 11–12pm (5 interns)

-

‐

Second Wednesday: 9–10am (6 residents), 10–11am (6 residents), 11–12pm (5 residents)

-

‐

Third Wednesday: 9–10am (6 residents), 10–11am (6 residents), 11–12pm (5 residents)

-

‐

Fourth Wednesday: 9–10am (6 residents), 10–11am (6 residents), 11–12 pm (5 residents)

-

‐

Individual Sessions:

-

‐

Individual resident sessions were scheduled directly with clinical social worker.

-

‐

Each resident was asked to complete one individual 30‐min session.

-

‐

Additional individual sessions were available as needed or as referred on a flexible time schedule for the resident.

3. PROGRAM IMPACT

The development team gathered evaluation data on the program using the residency annual end‐of‐year survey. The primary outcome was comparison of this wellness initiative to all other wellness initiatives in the program and assess resident attitudes toward the wellness initiative.

This was a locally approved institutional review board study and simple statistical analysis was applied to our data.

During the first year from October 1, 2020 to October 1, 2021 approximately 36 unique residents used the resource. There were 49 group and 73 individual sessions held with 95% of the meetings online given pandemic restrictions. In‐person meetings were held in an administration office on another floor away from residency offices. Only 2 residents were referred for further counseling.

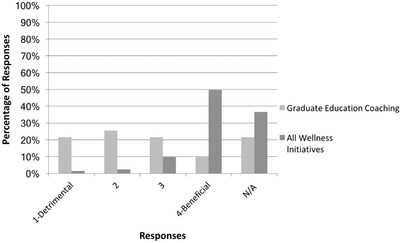

The development team gathered evaluation data on the program using the residency annual end‐of‐year survey with an overall response rate of 80.88% (n = 55/68) of all residents responding in the residency. The focus of this study was to assess the feasibility and attitudes of emergency medicine residents on this particular wellness intervention compared to other wellness interventions (eg, gym access, ride share program access, closer parking, new sick call policy etc.). The residents were asked the following question, “Please rate the following wellness initiatives, 1 = detrimental 4 = beneficial.” An open‐ended comment box was also available for written comments. The survey scale was 1–4, to avoid neutral ranking, with 1 as detrimental and 4 as beneficial and respondents could also label it not applicable if they did not participate in the initiative. The median and interquartile range (IQR) of all wellness initiatives was 3.79 (3.69–3.88). The coaching sessions had a median and IQR of 2 1 , 2 , 3 (Figure 1). In their summary comments in the end‐of‐year survey, the residents revealed the innovation was useful but many shared concern regarding their ability to attend sessions, having sessions during dedicated conference time and the capacity of the social worker to relate with them in their specific emergency medicineresidency setting. Further supporting these comments, graduating senior residents in their exit interviews, an interview without structured questions where residents could give open ended feedback about the program, felt this innovation was an excellent addition to the residency but also shared the concern regarding ability of the social worker to relate with the residents given differing clinical perspectives. In addition to familiarizing the coach with the clinical environment, residents recommended leadership bring topics to the group sessions rather than ask the residents to provide conversation topics and recommended reduction in group sessions so that there were more opportunities for individual sessions that residents could schedule at their convenience. Residents also sought delineation between situations that would benefit from mentorship versus coaching versus counseling. Mentors and others were often mentioned as sources for additional support and connection. However, almost every coaching session involved a sense of how someone was connected to their wider base of support. For example, almost every session conducted ended with the question of, “who do you want to talk to about maintaining your progress or holding you accountable to your goals?”

FIGURE 1.

Graduate education coaching versus all wellness initiatives.

This is a retrospective, single institution study using only emergency medicineresidents during a 1‐year time frame, which limits broader application to other specialties and professionals. The financial cost of implementation is also a major limitation in regard to other programs implementing a similar program given that our program financially supported this program completely.

4. LESSONS LEARNED

Implementation of an emergency medicine residency social worker/coach is feasible. It is a novel intervention that can teach habits of self‐monitoring and self‐reflection. 5 , 6 This implementation requires budget support, clear goals, and finding an appropriate individual to provide services. In our single institution experience over a 1‐year time frame, emergency medicine residents commonly used these services but felt that they would prefer to work with someone more knowledgeable about emergency medicine culture. A notable number, 22%, rated the program as detrimental, which could be related to the fact that many residents shared concern regarding their ability to attend sessions, loss of personal/educational time, lack of session structure, and the capacity of the chosen social worker to relate with them in their specific emergency medicine residency setting. Currently, we are using the same individual and providing increased support, perspective, and immersion into our clinical realm so that the social worker/coach can relate to our residents in a more cohesive way, such as by attending our case conferences and morbidity and mortality conferences. If other programs are interested in implementing a similar program, we would recommend seeking someone who has experience with GME and in the emergency department, or planning an intentional orientation to the setting and culture of residency before implementation. Residents also preferred individual sessions as opposed to group sessions and sought delineation in situations that would benefit from mentorship versus coaching versus counseling, which we subsequently developed as a process map tool for different types of coaching sessions and shared this with residents. We are also requiring all interns have a meeting with our coach to promote an ongoing relationship throughout residency. Application of a social worker coaching program in an emergency medicine residency appears to be a feasible and novel wellness intervention with potential to improve well‐being but needs framing and structure to benefit trainees. Ongoing assessment will be important to inform resident use and value placed on coaching as the professional coaching model becomes embedded in the residency culture.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Jennie A Buchanan, Sarah Meadows, Katherine Bakes, and Malorie Millner. Acquisition of the data: Jennie A Buchanan, Megan Stephens, Sarah Meadows, and Jason Whitehead. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Jennie A Buchanan, W. Gannon Sungar, Megan Stephens, and Sarah Meadows. Drafting of the manuscript: Jennie A Buchanan, Sarah Meadows, Jason Whitehead , W. Gannon Sungar, Christy Angerhofer, Abraham Nussbaum,, Barbara Blok, Todd Guth, Katherine Bakes, Malorie Millner, Lavonne Salazar, Megan Stephens, and Bonnie Kaplan. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jennie A Buchanan, Christy Angerhofer, W. Gannon Sungar, Todd Guth, Barbara Blok, Abraham Nussbaum,, Sarah Meadows, and Bonnie Kaplan. Statistical expertise: Jennie A Buchanan and Megan Stephens. Acquisition of funding: Bonnie Kaplan. Administrative, technical, or material support: Jason Whitehead , Malorie Millner, Lavonne Salazar, Megan Stephens, and Bonnie Kaplan. Study supervision: Jennie A Buchanan, Bonnie Kaplan, Megan Stephens, Lavonne Salazar, and Sarah Meadows.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Buchanan JA, Meadows S, Whitehead J, et al. Implementation of dedicated social worker coaching for emergency medicine residents ‐ Lessons learned. JACEP Open. 2023;4:e12971. 10.1002/emp2.12971

Supervising Editor: Katherine Edmunds, MD, Med

Presentations: This work was presented as an abstract/poster at Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine conferencein San Diego, April 2022.

The Department of Emergency Medicine provided funding to support this innovation, which supported the coaching services for $15,000 over 1 year.

Consulting for commercial interests, including advisory board work: Jason Whitehead was paid to provide coaching services for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chang J, Ray JM, Joseph D, Evans LV, Joseph M. Burnout and post‐traumatic stress disorder symptoms among emergency medicine resident physicians during the COVID‐19 pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(2):251‐257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin M, Battaglioli N, Melamed M, et al. High prevalence of burnout among US emergency Medicine residents: results from the 2017 National Emergency Medicine Wellness Survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(5):682‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Song X, Fu W, Liu X, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:60‐65. doi:\ 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002. Epub 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, et al. COVID‐19‐Related mental health effects in the workplace: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7857. doi:\ 10.3390/ijerph17217857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chung A, Mott S, Rebillot K, et al. Wellness interventions in emergency medicine residency programs: review of the literature since 2017. West J Emerg Med. 2020;22(1):7‐14. doi:\ 10.5811/westjem.2020.11.48884. Published 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jain A, Tabatabai R, Vo A, Riddell J. I have nothing else to give’’: a qualitative exploration of emergency medicine residents' perceptions of burnout. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(4):407‐415. doi:\ 10.1080/10401334.2021.1875833. Epub 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]