Abstract

Objective:

This study was performed to systematically review the current literature on the effects of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on multiple sclerosis-induced neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction.

Materials and methods:

Medical databases including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science were systematically searched from inception to September 2022. Meta-analysis was carried out using the comprehensive meta-analysis tool.

Results:

Our inclusion criteria were met by 12 studies evaluating the effects of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation/transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on multiple sclerosis-induced neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Comparing the post-intervention results to the baseline showed that the rate of frequency was decreased in both percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation groups after intervention. The overall mean change of tibial nerve stimulation on frequency was –2.623 (95% CI: –3.58, –1.66; P < .001, I 2: 87.04) among 6 eligible studies. The post-void residual was decreased after treatment in both methods of tibial nerve stimulation, with an overall mean difference of –31.13 mL (95% CI: –50.62, –11.63; P = .002, I 2: 71.81). The other urinary parameters, including urgency (mean difference: –4.69; 95% CI: –7.64, –1.74; P < .001, I 2: 92.16), maximum cystometric capacity (mean difference: 70.95; 95% CI: 44.69, 97.21; P < .001, I 2: 89.04), and nocturia (mean difference: –1.41; 95% CI: –2.22, 0.60; P < .001, I 2: 95.15), were improved after intervention, too. However, the results of subgroup analysis showed no effect of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on urinary incontinence (mean difference: –2.00; 95% CI: –4.06, 0.06; P = .057, I 2: 95.22) and nocturia (mean difference: –0.39; 95% CI: –1.15, 0.37; P = .315, I 2: 84.01). In terms of mean voided volume, the evidence was related to only percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation with a mean change of 75.01 mL (95% CI: –39.40, 110.61; P < .001, I 2: 85.04).

Conclusion:

Although the current literature suggests that tibial nerve electrostimulation might be an effective method for treating neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction, the evidence base is poor and derived from small, mostly nonrandomized trials with a high risk of bias and confounding.

Keywords: Tibial nerve stimulation, multiple sclerosis, neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction, neurogenic bladder, overactive bladder, systematic review

Main Points

One of the most prevalent problems among multiple sclerosis (MS) patients is neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD), for which there is now no definite treatment.

Two of the most promising neuromodulation techniques for minimizing MS-induced NLUTD are transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation which are the focus of this systematic review.

The meta-analysis of 8 studies found that individuals with MS-related NLUTD may benefit from percutaneous or transcutaneous electrostimulation of the tibial nerve.

Despite offering level 1 evidence, generalizability of the findings of this study is limited, especially as a result of the inclusion of uncontrolled, nonrandomized trials with small populations.

Introduction

Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD) is one of the most frequent complaints in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients. Approximately 90% of MS patients experience urologic symptoms 10 years after the outbreak of the disease, while 5%-10% of patients have bladder disturbances at the beginning of the disease.1,2

Considering their troublesome nature, these symptoms can severely affect patients’ quality of life (QoL).3 The bladder dysfunction can be attributed to several pathophysiological pathways, including impulse blockage in demyelinated axons, conduction failure due to neuronal degeneration, and possible functional impairment of cytokines.4

The first and the second pathology are related to damage in bladder control and the third pathology links the bladder disturbances to the dysfunction of receptors and neurotransmitters which are responsible for bladder control. In MS, NLUTD occurs as a consequence of spinal cord involvement above the sacral segment, leading to urinary symptoms including increased frequency and urgency of micturition, nocturia, incontinence, and inability to empty the bladder completely. The first 2 are suggested to be the most frequent ones.5,6

Approaching the MS-induced NLUTD consists of a multidisciplinary method. For instance, intermittent self-catheterization offers one of the best methods of coping with incomplete bladder emptying and urinary retention. Medications including antimuscarinics benefit patients with frequency, nocturia, urgency, or urge incontinence.7

Other approaches are available in cases where antimuscarinics are ineffective or poorly tolerated, including intradetrusor botulinum toxin, or nerve stimulation methods including tibial nerve stimulation (TNS) and sacral neuromodulation.8-10

Neuromodulation is, as defined by the International Neuromodulation Society, the use of implantable and non-implantable electrical or chemical technologies to enhance the quality of human life and functioning. The use of neuromodulation has been increased recently, especially for managing chronic pain, musculoskeletal disorders, psychiatric disorders, and epilepsy.10

Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) and percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) are 2 types of neuromodulation that have been proposed for the treatment of MS-related urinary disturbances.11-13 These techniques rely on electrical stimulation of the tibial nerve to constrain the detrusor muscle. The most frequently reported intervention in the greater part of academic studies consists of 30-minute stimulation sessions performed every week for 10-12 weeks.14

Having the importance of managing NLUTD and its high prevalence among MS patients in mind, this study aims to systematically review the current literature on the effects of TNS (PTNS/TTNS) on the MS-induced NLUTD.

Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement was followed when conducting this study to ensure accurate data reporting.15 The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under the code CRD42022360571.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

From their creation to September 2022, a number of medical databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science, were thoroughly searched. They were then updated in October 2021. Google Scholar and all the references of the included studies were also checked for items that met the inclusion criteria, and those were imported to make sure there was complete saturation. The main search terms were as follows: “multiple sclerosis,” “MS,” “tibial nerve stimulation,” “percutaneous electric nerve stimulation,”, “PTNS,” “transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation,” “TTNS,” “neuromodulation,” “neurogenic bladder,” “urinary bladder,” “overactive bladder,” “urinary incontinence,” and “neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction.” The Endnote X20 citation manager software was used to import the search results for further exploration.

Eligibility Requirements

Two impartial reviewers conducted the eligibility evaluation (F.T. and S.H.). A third reviewer was consulted to settle any disagreements (H.S.). Studies were selected for further survey if they met all of the following criteria: (1) studies aiming to determine the effects of PTNS and/or TTNS on NLUTD in MS patients; (2) a population consisting of humans; and (3) available English full text.

Unoriginal articles including any type of reviews, conference proceedings, letters, and commentaries were excluded.

Quality Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed through the Joanna Briggs Institute tools of critical appraisal, each individualized based on the methodology of the study.16 In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer evaluated the study for confirmation after 2 authors independently evaluated the quality of the studies.

Data Collection Process and Data Items

In a predetermined Excel sheet, 2 authors (F.T. and H.S.) extracted the data from the included studies. From each of the included studies, the following information was taken: data on citations including the first author’s name; the publication’s year and place of publication; the number, condition, and age of patients; the condition of the control group; the type of intervention used; the number, length, and frequency of therapy sessions; the length of the follow-up period; and the main outcomes of measure.

Synthesis of Results

The comprehensive meta-analysis tool v3.7z was used to conduct the meta-analysis. For identifying heterogeneity within the studies, the Q statistic was used. Additionally, the I 2 statistic was used to calculate the effect of study heterogeneity. Low I 2 was defined as 25%, moderate as 25%-75%, and high as >75%. A fixed-effect model was used when there was no statistically significant difference in the heterogeneity (P < .05); otherwise a random effect model was applied.

Results

Literature Search and Description of Studies

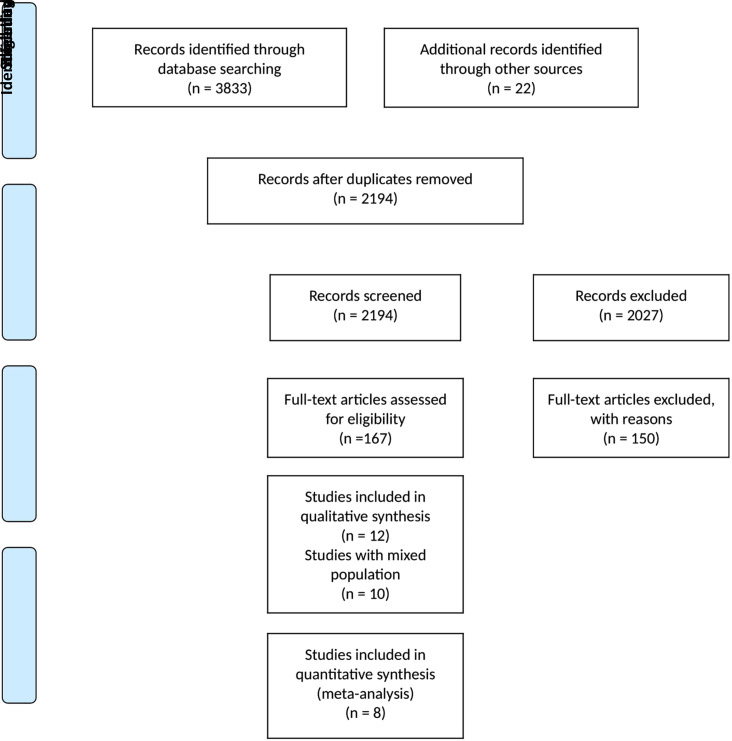

Up until September 2022, we discovered 3855 publications through the use of electronic databases, manual searches, and reference checking. After the duplicate studies were eliminated, 2194 studies underwent title/abstract screening. After reviewing the full texts of 41 articles, we determined that 12 studies satisfied our inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. A total of 8 studies were eligible for meta-analysis. In addition, 10 studies were found with mixed population; however, they did not separate data for the MS patients; therefore, we were unable to analyze their findings (Supplementary Table 1). The PRISMA flow diagram displays more details about the selection procedure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram representing the selection process.

Summary of the Evidence

Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics and the quality of the included studies, respectively. Twelve clinical studies were included, which assessed the outcomes of TNS among MS population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Citation | Origin | Design | Arms (n) | Patients | Intervention | F/U (Weeks) | Main Outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Male/Female | Mean Age (Years) | EDSS Score | Duration of MS (Years) | Duration of NLUTD (Years) | Session/Week | Duration (Minutes) | Frequency | Pulse Width | ||||||

| PTNS | |||||||||||||||

| Fjorback (2007) | Denmark | Case series | 1 | 12 | 7/5 | 46 | – | – | – | – | – | 20 Hz | 200 μs | None | Detrusor overactivity via 2 successive slow-fill cystometries |

| Kabay (2008) | Turkey | Clinical trial | 1 | 29 | 12/17 | 46.5 ± 8.5 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 8.80 ± 3.6 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | – | – | 20 Hz | 200 ms | None | Acute urodynamic effects, including mean first involuntary detrusor contractions and mean maximum cystometric capacity |

| Kabay (2009) | Turkey | Clinical trial | 1 | 19 | 6/13 | 44.9 ± 8.3 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 8.2 ± 3.3 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 1 | 30 | 20 Hz | 200 μs | 12 | Urodynamic findings including mean volume at the first involuntary detrusor contraction, mean maximum cystometric capacity, mean P detmax at first involuntary detrusor contraction, maximal detrusor pressure at maximum cystometric capacity, detrusor pressure at maximal flow (P detQmax), and maximal flow rate (Q max) |

| Kabay (2015) | Turkey | Clinical trial | 1 | 21 | 5/16 | 42.7 ± 6.9 | 4.2 ±1.5 | 9.56 ± 3.6 | 4.8 ±1.6 | 4-day intervals for 3 months, 21-day intervals for 3 months, and 28-day intervals for 3 months | – | 20 Hz | 200 μs | 12 | Voiding diary, ICIQ-SF, OAB-V8, and OAB-q SF |

| Gobbi (2011) | Switzerland | Clinical trial | 1 | 18 | 2/16 | 46 ± 13 | 4.5 ± 2.1 | 15 ± 10 | – | 1 | 30 | 20 Hz | 200 μs | 12 | 3-Day frequency volume chart, PPBC questionnaire, PPIUS, patient assessment of urgency bother (VAS-UB), KHQ, and VAS score |

| Zecca (2014) (A) | UK | Cohort | 1 | 83 | 21/62 | 49 | 4.1 | 14.4 | – | 1 | 30 | 20 Hz | 200 μs | 12 | 3-Day bladder diary, PPBC questionnaire, 7-level GRA scale, OAB-q, PPIUS, KHQ, and OAB-q |

| Zecca (2014) (B) | UK | Clinical trial | 1 | 83 | 21/62 | 49 | 4 | 14.4 | – | 1 | 30 | 20 Hz | 200 ms | NA | 3-Day frequency volume chart and PPBC questionnaire, patient perception of VAS TS-VAS, 7-level GRA scale |

| TTNS | |||||||||||||||

| De Seze (2011) | France | Clinical trial | 1 | 70 | 19/51 | 48.3 ± 10.2 | 4.03 ± 1.60 | 13.4 ± 9.3 | 8.2 ± 7.8 | 7 | 30 | 10 Hz | 200 μs | 12 | Clinical efficacy on urgency, based on warning time (WT), urgency “Mesure du Handicap Urinaire (MHU)” subscale, 3 days voiding chart, QoL, urodynamic parameter changes, and tolerance |

| Dunya (2020) | Turkey | Clinical trial | A1: TTNS A2: PFMT |

55 | All female | 43.49 ± 8.66 | 3.69 ± 1.64 | 13.70 ± 8.63 | 7.67 ± 6 | 5 | 30 | 10 Hz | 200 μs | 6 | Bladder diary, PVR, and Qualiveen scales |

| Dunya (2021) | Turkey | Clinical trial | A1: TTNS A2: PFMT |

30 | All female | 42.80 ± 7.74 | 3.40 ± 1.52 | 13.70 ± 9.40 | 7.42 ± 6.15 | 5 | 30 | 10 Hz | 200 ms | 6 | Sexual function index (FSFI), OABv‐8, and sexual quality of life—female (SQoL‐F) questionnaires |

| Al Dandan (2021) | Ireland | Clinical trial | 1 | 20 | 6/14 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 30 | 10 Hz | 0.2-0.5 ms equal to 200 μs | 6 | Feasibility of the intervention, bladder storage symptoms, and quality of life using ICIQ-OAB |

| Zonić-Imamović (2019) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Randomized clinical trial | A1: TTNS A2: oxybutynin |

60 | 20/40 | A1: 47.36 ± 7.98 A2: 45.8 ± 8.13 |

– | A1: 8.9 ± 4.9 A2: 8.3 ± 5.1 |

– | 7 | 30 | 10 Hz | 200 ms | 12 | OAB-q SF, QoF |

EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; F/U, follow-up; ICIQ-OAB, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire on OAB; KHQ, King’s Health Questionnaire; MS, multiple sclerosis; NLUTD, neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction; PFMT, pelvic floor muscle training; PPBC, patient perception of bladder condition; PPIUS, Patient Perception of Intensity of Urgency Scale; PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; PVR, post-voiding residue; QoL, Quality of Life; SF, Short Form; TS-VAS, treatment satisfaction via using a visual analog scale; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Table 2.

The Assessment of Included Studies Based on the JBI Checklist

| Citation | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Quality of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case series | ||||||||||||||

| Fjorback (2007) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | – | – | – | Low |

| Cohort | ||||||||||||||

| Zecca (2014) (A) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | – | – | Moderate |

| Nonrandomized clinical trial | ||||||||||||||

| Kabay (2008) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | Moderate |

| Kabay (2009) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Kabay (2015) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Gobbi (2011) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Zecca (2014) (B) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| De Seze (2011) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Dunya (2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Dunya (2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Al Dandan (2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | – | High |

| Randomized clinical trial | ||||||||||||||

| Zonić-Imamović (2019) | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Low |

JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute.

Seven studies used PTNS17-23 and the other 5 used TTNS as the neuromodulation technique.24-28 Five studies took place in Turkey,18-20,26,25 2 studies in the United Kingdom,22,23 and 1 in each of the following countries: Denmark,17 Switzerland,21 France,24 and Bosnia and Herzegovina.28 Three studies had a parallel control group—2 was a nonrandomized clinical trial with a control group consisting of pelvic floor muscle training25,26 and the other 1 was a randomized clinical trial with a control group receiving 5 mg oxybutynin tablet twice a day for 3 months.28 The Expanded Disability Status Scale score was reported in 9 studies and varied from the minimum of 3.40 to 4.8.

Furthermore, publications with mixed populations were reviewed to check for possible MS inclusions. Ten articles were found with a population consisting of patients with overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, among which some were diagnosed with MS.29-38 In 5 articles TTNS and in the other 5 PTNS were sued as the intervention. All of these publications, except for 1, supported the beneficial effects of TNS in enhancing different parameters regarding the OAB symptoms. However, none of these articles reported data exclusive for MS patients; therefore, they are taken into consideration in our study. The results are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

We assessed the overall outcomes of the daily voiding frequency, daily leakage episodes (incontinence), urgency episodes, frequency of nighttime urination (nocturia), and cystometric parameters including mean voiding volume (MVV), maximum cystometric capacity (MCC), and post-void residual (PVR). The overall analysis results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The Results of Meta-analysis

| Groups | Outcome | Effect Size and 95% CI | Test of Null (2-Tail) | Heterogeneity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Studies | Point Estimate | Standard Error | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Z-Value | P | Q-Value | df (Q) | P | I 2 | ||

| PTNS | Frequency | 3 | –2.991 | 0.801 | –4.561 | –1.421 | –3.733 | .000 | 36.521 | 2 | .00 | 94.524 |

| TTNS | 3 | –2.191 | 0.370 | –2.916 | –1.466 | –5.922 | .000 | 0.215 | 2 | .90 | 0.000 | |

| 6 | –2.623 | 0.491 | –3.585 | –1.661 | –5.343 | .00 | 38.589 | 5 | .00 | 87.043 | ||

| PTNS | PVR | 3 | –45.478 | 7.843 | –60.849 | –30.107 | –5.799 | .000 | 0.789 | 2 | .67 | 0.000 |

| TTNS | 2 | –14.301 | 3.325 | –20.817 | –7.784 | –4.301 | .000 | 0.007 | 1 | .93 | 0.000 | |

| Total | 5 | –31.132 | 9.946 | –50.625 | –11.638 | –3.130 | .002 | 14.193 | 4 | .01 | 71.816 | |

| PTNS | Urgency | 1 | –7.280 | 0.567 | –8.392 | –6.168 | –12.831 | .00 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 |

| TTNS | 2 | –3.303 | 0.659 | –4.594 | –2.011 | –5.012 | .00 | 1.294 | 1 | .26 | 22.749 | |

| Total | 3 | –4.696 | 1.504 | –7.643 | –1.749 | –3.123 | .00 | 25.516 | 2 | .00 | 92.162 | |

| PTNS | MCC | 2 | 80.941 | 12.676 | 56.096 | 105.785 | 6.385 | .00 | 10.274 | 1 | .00 | 90.267 |

| TTNS | 1 | 38.700 | 18.539 | 2.364 | 75.036 | 2.087 | .04 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 | |

| Total | 3 | 70.957 | 13.399 | 44.694 | 97.219 | 5.296 | .00 | 18.252 | 2 | .00 | 89.042 | |

| PTNS | MVV | 3 | 75.011 | 18.165 | 39.409 | 110.614 | 4.129 | .00 | 13.371 | 2 | .00 | 85.043 |

| PTNS | Nocturia | 3 | –2.036 | 0.189 | –2.407 | –1.665 | –10.750 | .00 | 5.221 | 2 | .07 | 61.696 |

| TTNS | 2 | –0.392 | 0.390 | –1.156 | 0.373 | –1.005 | .315 | 6.257 | 1 | .01 | 84.018 | |

| Total | 5 | –1.419 | 0.413 | –2.229 | –0.609 | –3.434 | .00 | 82.539 | 4 | .00 | 95.154 | |

| PTNS | Urinary incontinence | 1 | –3.330 | 0.391 | –4.096 | –2.564 | –8.525 | .00 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 |

| TTNS | 3 | –1.464 | 0.959 | –3.344 | 0.416 | –1.527 | .127 | 15.023 | 2 | .00 | 86.687 | |

| Total | 4 | –2.000 | 1.051 | –4.061 | 0.060 | –1.903 | .057 | 62.842 | 3 | .00 | 95.226 | |

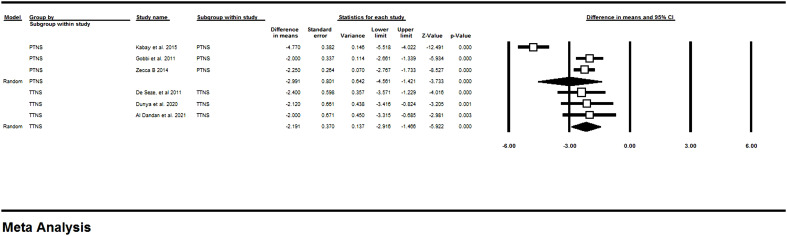

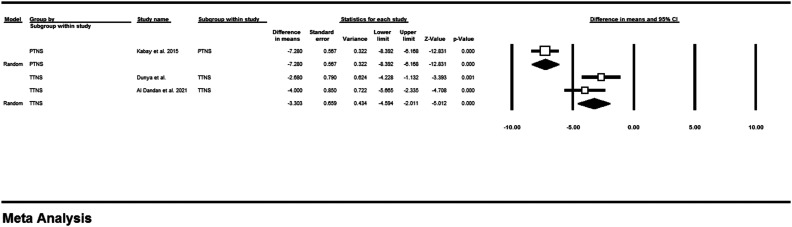

Meta-analysis of Daily Voiding Frequency

Figure 2 shows the results of meta-analysis of the pre- and post-intervention values of 6 studies (3 PTNS and 3 TTNS) regarding the daily frequency. Accordingly, the frequency was decreased significantly after the stimulation of tibial nerve (MD: –2.62, 95% CI: –3.58 to –1.66 and P < .001; I 2: 87.04). The subgroup analysis of showed that PTNS (MD: –2.99, 95% CI: –4.56 to –1.42, and P < .001; I 2: 94.52) and TTNS (MD: –2.19, 95% CI: –2.91 to –1.46, and P < .001; I 2: 0) each can significantly reduce the frequency as well.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the daily voiding frequency. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

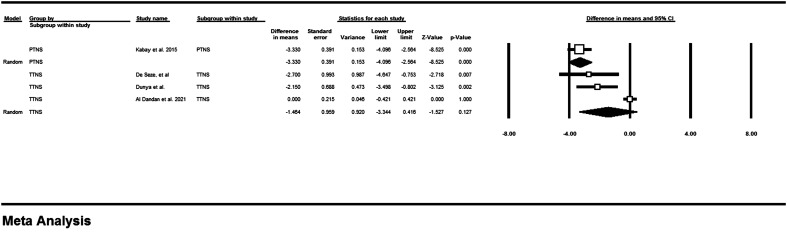

Meta-analysis of Daily Leakage Episodes

Daily leakage or incontinence episode was reduced after the application of PTNS in 1 study (MD: –3.33, 95% CI: –4.09 to –2.56, and P < .001; I 2: 0). The TTNS subgroup and the overall effect of TNS on urinary incontinence episodes did not show a significant reduction (MD: –1.46, 95% CI: –1.52 to 0.127, and P = .127), and MD: –2.00 (95% CI: –4.06 to 0.060, and P = .057). The results of meta-analysis are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the daily leakage episodes. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

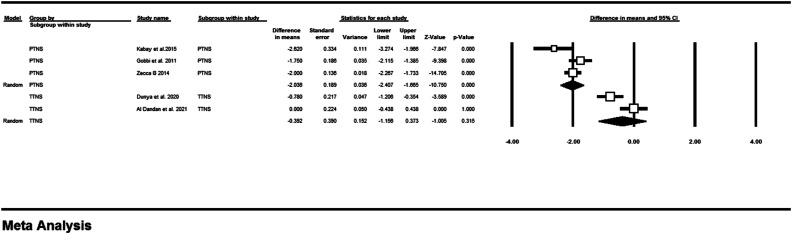

Meta-analysis of Nocturia

The meta-analysis of 6 studies, presented in Figure 4, showed that nocturia episodes are decreased significantly following TNS (MD: –1.41, 95% CI: –2.22 to –0.60, and P < .001). Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and TTNS subgroups each also reduced these episodes; however, the reduction was statistically significant in PTNS (MD: –2.03, 95% CI: –2.40 to –1.66, and P < .001), while it was insignificant in TTNS (MD = –0.39, 95% CI: –1.005 to 0.315 and P = .315).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the nocturia. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

Meta-analysis of Urgency Episodes

As presented in Figure 5, daily urgency episodes, experienced by patients from 3 studies, were decreased significantly (MD: –4.69, 95% CI: –1.504 to –7.64, and P < .001).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of the urgency episodes. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

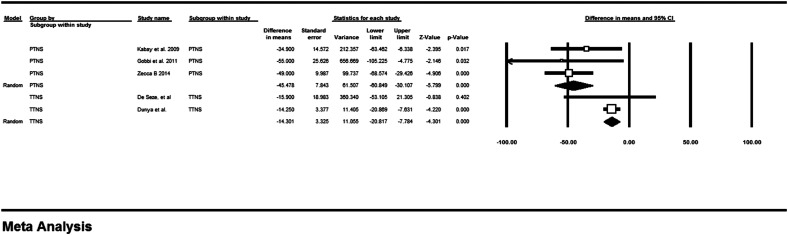

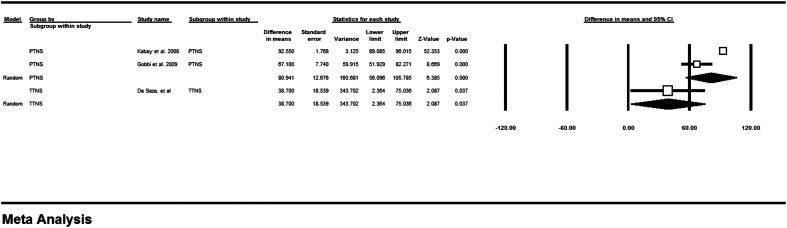

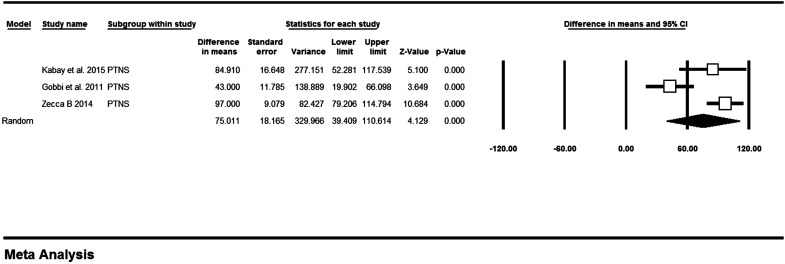

Cystometric Parameters

The results of meta-analyzing PVR, MCC, and MVV are presented in Figures 6, 7, and 8, respectively. According to the meta-analysis of 5 studies, PVR shows a significant reduction after the application of TNS (MD: –31.13, 95% CI: –50.62 to –11.63, and P = .002). The subgroup analysis shows that PTNS and TTNS showed a significant reduction in PVR (MD: –45.47, 95% CI: –60.84 to –30.10, and P < .001; MD: –14.30, 95% CI: –20.81 to –7.78, and P < .001, respectively).

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis of the post-voiding residual. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

Figure 7.

Meta-analysis of the maximum cystometric capacity. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; TTNS, transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

In 3 studies, MCC was insignificantly enhanced (MD: 70.95, 95% CI: 44.69 to 97.21, and P < .001) and MVV was significantly increased after only in PTNS eligible studies (MD: 75.01, 95% CI: 39.40 to 110.61, and P < .00) (Figures 7 and 8, respectively).

Figure 8.

Meta-analysis of the mean voiding volume. PTNS, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation.

Discussion

The aim of our systematic review was to analyze the scientific evidence on the treatment of MS-induced NLUTD through PTNS or TTNS procedures and evaluate the results of post-intervention with baseline amounts. Tibial nerve electrostimulation appears to be promising interventions, according to the results of our review.

Multiple sclerosis is a unique neurological disease. It manifests with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations. These symptoms are related with time and disease course. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs), which are highly prevalent in MS patients (affecting over 80% of patients), are closely intertwined with the location of the plaque, that is either intracranial or spinal. Even, in some cases, LUTSs are the primary manifestation of MS (in 10% of patients), and also patients’ disability status is usually related to the severity of their symptoms. Overactive bladder symptoms are the most frequently reported complaints. Urinary urgency (38%-99% of patients), increased urinary frequency (26%-82% of patients) and urge incontinence (27%-66% of patients), stress urinary incontinence (with a prevalence of 56%), and mixed urinary incontinence are among the mostly reported symptoms of patients with MS, which cause a significant decrease of QoL. By contrast, symptoms of the voiding phase are less frequent (6%-49%). Symptoms of both the storage and voiding phases can coexist in 50% of patients.10

Urinary tract is regulated by the medial prefrontal cortex, insula, and pons, and lesions in cortical regions lead to detrusor overactivity (DO). In addition, spinal cord, and particularly suprasacral lesions that are common in MS patients, may cause DO by impacting the descending inhibition of bladder contraction. Reticulospinal tract damage may lead to detrusor–sphincter–dyssynergia (DSD). Urinary retention may result from plaques that obstruct emptying in the efferent or afferent pathways. Only 5% of patients with sacral lesions have bladder areflexia, despite the fact that 63% of them exhibit detrusor hypocontractility.39

Litwiller et al, in a meta-analysis, showed that 62% of MS patients had Neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO). The other signs were DSD (25%), and Detrusor underactivity (DU) (20%). In addition, 10% were normal on examination. Low bladder capacity, increased PVR volume, and increased DO amplitude are common in MS patients. As MS is a fluctuating disease, and often presents in recurring attacks, in which the symptoms become worse or new symptoms appear, and between attacks, Urodynamic studies (UDS) shows urinary tract function at particular time points despite the fact that the symptoms may get better or stay the same.3

Different studies reported various prevalence of urinary symptoms in MS patients. A prevalence of 37%-99% for OAB, characterized by irritative bladder symptoms, 34%-79% for obstructive symptoms, and 25% for chronic urinary retention was reported.6

Management of MS-induced NLUTD requires a multidisciplinary model. Some of the most common approaches are medical therapies, such as antimuscarinics, intermittent self-catheterization, the use of synthetic antidiuretic hormone desmopressin, cannabinoids, and intravesical treatments like Onabotulinum toxin A (BoNTA) injection. Other therapeutic approaches are neuromodulation, including TNS and sacral nerve stimulation (SNS), and surgical treatments such as cystoplasty and non-continent urinary diversion.10

After behavioral therapies and medication management, nerve stimulation and neuromodulation is the third-line therapy used to treat these patients.40

Although the exact mechanism of TNS or sacral nerve root S3 stimulation in managing OAB remains uncertain, its efficacy has been proved. However, it is thought to be a result of modulation of spinal pelvic reflexes through the activation of inhibitory interneurons.41

The effects of TNS for NLUTD and OAB syndrome have also been the subject of multiple systematic reviews in the recent literature.42-45 However, just 1 systematic review that examined the impact of PTNS on MS-induced NLUTD in patients with MS was published, and the findings were favorable.46 The effects of TTNS on female MS patients with OAB syndrome have also been the subject of a protocol for a systematic review; however, its results have not yet been made public.47

The unique aspect of our study is the combination of these 2 approaches, which closes this knowledge gap and tackles both PTNS and TTNS in MS patients, offering fresh perspectives on the overall impacts of cutting-edge neuromodulation techniques.48

Limitations

Despite providing level 1 evidence, this study may be subject to bias, primarily due to the inclusion of nonrandomized and uncontrolled trials with limited populations. Second¸ none of the studies addressed the long-term efficacy of the TNS; therefore, it is yet unknown whether the improvement of NLUTD is lifelong, and generalizing the results to clinical settings is rather restricted.

Conclusion

The results of the current systematic review showed that stimulation of the tibial nerve shows a promising future in managing NLUTD in MS patients. However, due to the high heterogeneity among studies, these results must be interpreted with caution. The long-term effects of TNS therapy and its cost-effectiveness need to be addressed further by high-quality and controlled trials.

Supplementary Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies with Mixed Populations

|

TTNS |

|||||||

|

Welk, 2020 |

Canada |

RCT |

OAB+neurogenic bladder |

50 (not mentioned) |

10/40 |

62 |

Patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC) |

|

Amarenco, 2004 |

France |

Prospective, open-label trial |

Neurologic+idiopathic |

44 (13) |

15/29 |

53.3 |

Urodynamic parameters including mean first involuntary detrusor contraction volume, maximum cystometric capacity |

|

Seth, 2018 |

UK |

Prospective, single centre, open label |

Neurologic+idiopathic |

48 (24) |

10/38 |

46.4 and 46.9 in two arms |

ICIQ-OAB,ICIQ-LUTSqol , 3-day bladder diary and a Global Response Assessment (GRA) |

|

Valles-Antuna, 2017 |

Spain |

prospective cohort |

Urge urinary incontinence (UUI) |

65 (9) |

24/41 |

55.06 |

48-hour micturitional calendar |

|

Tornic, 2019 |

Switzerland |

RCT |

Neurogenic LUTD |

9 (2 ) |

7/2 |

52.8 |

feasibility, acceptability, safety of TTNS |

|

PTNS |

|||||||

|

Tudor, 2018 |

UK |

retrospective cohort |

Neurologic+idiopathic |

74 (19 ) |

22/52 |

56 |

ICIQ-OAB, ICIQ-LUTSqol, 3-day bladder diary parameters |

|

Jung 2020, (A) |

USA |

retrospective cohort |

OAB |

141 (not mentioned) |

All female |

70 |

PGI-I, OABq-SF |

|

Jung 2020, (B) |

USA |

retrospective cohort |

OAB |

334 (not mentioned) |

All female |

70.9 |

PGI-I, OABq-SF |

|

Salatzki, 2019 |

UK |

cross-sectional |

OAB |

79 (27) |

20/59 |

58.9 |

bladder diary, PTNS Service Evaluation Questionnaire (PTNS-SEQ), ICIQ-OAB, ICIQ-LUTSqol |

|

Arrabal-Polo, 2012 |

Spain |

prospective cohort |

OAB |

14 (1) |

All female |

60.8 |

48-hour micturitional calendar |

1. F/U: Follow-up; 2. MS: Multiple sclerosis; 3. M/F: Male/female; 4. TTNS: Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; 5. RCT: Randomized controlled trial; 6. OAB: Overactive bladder; 7. Hz: Hertz; 8. ms: Millisecond; 9. ICIQ-OAB: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire on OAB; 10. ICIQ-LUTSqol: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life Module; 11. LUTD: Lower urinary tract dysfunction; 12. μs: Microsecond; 12. PGI-I: Patient Global Impression- Improvement; 12. OABq-SF: Overactive Bladder Questionnaire-Short Form

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: The regional Ethics Committee approved the protocol of this study. (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.375).

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – F.T., S.H.; Design – F.T., H.S.-P., Supervision – S.H., S.H.; Resources –F.T., H.S.-P., R.M.H.; Materials – F.T., S.H., H.S.-P.; Data Collection and/or Processing – F.T., R.M.H., H.S.-P.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – F.T., S.H., H.S.-P.; Literature Search – F.T., S.H.; Writing Manuscript – F.T., R.M.H., S.H., H.S.-P.; Critical Review – S.H., S.H.

Acknowledgments: This study is derived from a thesis, and we would like to express our gratitude to the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology, of Tabriz University of medical sciences for approving the protocol.

Declaration of Interests: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding: This article was financially supported by the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology. (grant no: 67487).

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine committee on multiple sclerosis: current S, strategies for the F. In: Joy JE, Johnston RB.eds. Multiple Sclerosis: Current Status and Strategies for the Future. US: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Copyright 2001 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Washington: , : DC. ( 10.17226/10031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCombe PA, Gordon TP, Jackson MW. Bladder dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(3):331 340. ( 10.1586/14737175.9.3.331) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Litwiller SE, Frohman EM, Zimmern PE. Multiple sclerosis and the urologist. J Urol. 1999;161(3):743 757. ( 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61760-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith KJ, McDonald WI. The pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis: the mechanisms underlying the production of symptoms and the natural history of the disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354(1390):1649 1673. ( 10.1098/rstb.1999.0510) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oppenheimer DR. The cervical cord in multiple sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1978;4(2):151 162. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1978.tb00555.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Sèze M, Ruffion A, Denys P, Joseph PA, Perrouin-Verbe B. GENULF. The neurogenic bladder in multiple sclerosis: review of the literature and proposal of management guidelines. Mult Scler. 2007;13(7):915 928. ( 10.1177/1352458506075651) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tornic J, Panicker JN. The management of lower urinary tract dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(8):54. ( 10.1007/s11910-018-0857-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersson KE. Current and future drugs for treatment of MS-associated bladder dysfunction. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57(5):321 328. ( 10.1016/j.rehab.2014.05.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaviani A, Khavari R. Disease-specific outcomes of botulinum toxin injections for neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Urol Clin North Am. 2017;44(3):463 474. ( 10.1016/j.ucl.2017.04.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phé V, Chartier-Kastler E, Panicker JN. Management of neurogenic bladder in patients with multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Urol. 2016;13(5):275 288. ( 10.1038/nrurol.2016.53) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krames ES, Peckham PH, Rezai A, Aboelsaad F. What is neuromodulation? In: Neuromodulation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2009:3 8. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Finazzi-Agrò E, Petta F, Sciobica F, Pasqualetti P, Musco S, Bove P. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation effects on detrusor overactivity incontinence are not due to a placebo effect: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2010;184(5):2001 2006. ( 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ridout AE, Yoong W. Tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder syndrome unresponsive to medical therapy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30(2):111 114. ( 10.3109/01443610903428922) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaziev G, Topazio L, Iacovelli V.et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) efficacy in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctions: a systematic review. BMC Urol. 2013;13(1):61. ( 10.1186/1471-2490-13-61) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336 341. ( 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global/. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fjorback MV, van Rey FS, van der Pal F, Rijkhoff NJ, Petersen T, Heesakkers JP. Acute urodynamic effects of posterior tibial nerve stimulation on neurogenic detrusor overactivity in patients with MS. Eur Urol. 2007;51(2):464 470. ( 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kabay SC, Yucel M, Kabay S. Acute effect of posterior tibial nerve stimulation on neurogenic detrusor overactivity in patients with multiple sclerosis: urodynamic study. Urology. 2008;71(4):641 645. ( 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kabay S, Kabay SC, Yucel M.et al. The clinical and urodynamic results of a 3-month percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis-related neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(8):964 968. ( 10.1002/nau.20733) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Canbaz Kabay S, Kabay S, Mestan E.et al. Long term sustained therapeutic effects of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation treatment of neurogenic overactive bladder in multiple sclerosis patients: 12-months results. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(1):104 110. ( 10.1002/nau.22868) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gobbi C, Digesu GA, Khullar V, El Neil S, Caccia G, Zecca C. Percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation as an effective treatment of refractory lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis: preliminary data from a multicentre, prospective, open label trial. Mult Scler. 2011;17(12):1514 1519. ( 10.1177/1352458511414040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zecca C, Digesu GA, Robshaw P.et al. Motor and sensory responses after percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in multiple sclerosis patients with lower urinary tract symptoms treated in daily practice. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(3):506 511. ( 10.1111/ene.12339) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zecca C, Digesu GA, Robshaw P, Singh A, Elneil S, Gobbi C. Maintenance percutaneous posterior nerve stimulation for refractory lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis: an open label, multicenter, prospective study. J Urol. 2014;191(3):697 702. ( 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Sèze M, Raibaut P, Gallien P.et al. Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for treatment of the overactive bladder syndrome in multiple sclerosis: results of a multicenter prospective study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(3):306 311. ( 10.1002/nau.20958) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polat Dunya C, Tulek Z, Kürtüncü M, Panicker JN, Eraksoy M. Effectiveness of the transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and pelvic floor muscle training with biofeedback in women with multiple sclerosis for the management of overactive bladder. Mult Scler. 2021;27(4):621 629. ( 10.1177/1352458520926666) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Polat Dunya C, Tülek Z, Kürtüncü M, Gündüz T, Panicker JN, Eraksoy M. Evaluating the effects of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation or pelvic floor muscle training on sexual dysfunction in female multiple sclerosis patients reporting overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40(6):1661 1669. ( 10.1002/nau.24733) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al Dandan HB, Galvin R, Robinson K, McClurg D, Coote S. Feasibility and acceptability of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the treatment of bladder storage symptoms among people with multiple sclerosis. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2022;8(1):161. ( 10.1186/s40814-022-01120-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zonić-Imamović M, Imamović S, Čičkušić A, Delalić A, Hodžić R, Imamović M. Effects of treating an overactive urinary bladder in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Med Acad. 2019;48(3):271 277. ( 10.5644/ama2006-124.267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amarenco G, Ismael SS, Even-Schneider A.et al. Urodynamic effect of acute transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in overactive bladder. J Urol. 2003;169(6):2210 2215. ( 10.1097/01.ju.0000067446.17576.bd) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arrabal-Polo MA, Palao-Yago F, Campon-Pacheco I, Martinez-Sanchez M, Zuluaga-Gomez A, Arrabal-Martin M. Clinical efficacy in the treatment of overactive bladder refractory to anticholinergics by posterior tibial nerve stimulation. Korean J Urol. 2012;53(7):483 486. ( 10.4111/kju.2012.53.7.483) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jung CE, Menefee SA, Diwadkar GB. 8 versus 12 weeks of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation and response predictors for overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(5):905 914. ( 10.1007/s00192-019-04191-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jung CE, Menefee SA, Diwadkar GB. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation maintenance therapy for overactive bladder in women: long-term success rates and adherence. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(3):617 625. ( 10.1007/s00192-020-04325-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salatzki J, Liechti MD, Spanudakis E.et al. Factors influencing return for maintenance treatment with percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the management of the overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2019;123(5A):E20 E28. ( 10.1111/bju.14651) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seth JH, Gonzales G, Haslam C.et al. Feasibility of using a novel non-invasive ambulatory tibial nerve stimulation device for the home-based treatment of overactive bladder symptoms. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7(6):912 919. ( 10.21037/tau.2018.09.12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tornic J, Liechti MD, Stalder SA.et al. Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for treating neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: a pilot study for an international multicenter randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6(5):909 915. ( 10.1016/j.euf.2019.11.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tudor KI, Seth JH, Liechti MD.et al. Outcomes following percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) treatment for neurogenic and idiopathic overactive bladder. Clin Auton Res. 2020;30(1):61 67. ( 10.1007/s10286-018-0553-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Valles-Antuña C, Pérez-Haro ML, González-Ruiz de L C.et al. Transcutaneous stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve for treating refractory urge incontinence of idiopathic and neurogenic origin. Actas Urol Esp. 2017;41(7):465 470. ( 10.1016/j.acuro.2017.01.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Welk B, McKibbon M. A randomized, controlled trial of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation to treat overactive bladder and neurogenic bladder patients. Can Urol Assoc J. 2020;14(7):E297 E303. ( 10.5489/cuaj.6142) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aharony SM, Lam O, Corcos J. Evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms in multiple sclerosis patients: review of the literature and current guidelines. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(1-2):61 64. ( 10.5489/cuaj.4058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lightner DJ, Gomelsky A, Souter L, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202(3):558 563. ( 10.1097/JU.0000000000000309) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nuhoğlu B, Fidan V, Ayyildiz A, Ersoy E, Germiyanoğlu C. Stoller afferent nerve stimulation in woman with therapy resistant over active bladder; a 1-year follow up. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(3):204 207. ( 10.1007/s00192-005-1370-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schneider MP, Gross T, Bachmann LM.et al. Tibial nerve stimulation for treating neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2015;68(5):859 867. ( 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Booth J, Connelly L, Dickson S, Duncan F, Lawrence M. The effectiveness of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) for adults with overactive bladder syndrome: a systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(2):528 541. ( 10.1002/nau.23351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burton C, Sajja A, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(8):1206 1216. ( 10.1002/nau.22251) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gaziev G, Topazio L, Iacovelli V.et al. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) efficacy in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctions: a systematic review. BMC Urol. 2013;13(1):1 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guitynavard F, Mirmosayyeb O, Razavi ERV.et al. Percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs) treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;58:103392. ( 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103392) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tu H, Li N, Liu W, Fan Z, Kong D. Effects of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on females with overactive bladder syndrome in multiple sclerosis a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis . PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0269371. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0269371) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a