Abstract

A gene cluster upstream of the arylsulfatase gene (atsA) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa was characterized and found to encode a putative ABC-type transporter, AtsRBC. Mutants with insertions in the atsR or atsB gene were unable to grow with hexyl-, octyl-, or nitrocatecholsulfate, although they grew normally with other sulfur sources, such as sulfate, methionine, and aliphatic sulfonates. AtsRBC therefore constitutes a general sulfate ester transport system, and desulfurization of aromatic and medium-chain-length aliphatic sulfate esters occurs in the cytoplasm. Expression of the atsR and atsBCA genes was repressed during growth with sulfate, cysteine, or thiocyanate. No expression of these genes was observed in the cysB mutant PAO-CB, and the ats genes therefore constitute an extension of the cys regulon in this species.

Sulfate esters make up a large proportion of the sulfur that is found in aerobic soils, and so it is not surprising that many soil microorganisms have evolved enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of these compounds, either to release the sulfate moiety as a sulfur source for growth, or as the first step in their mineralization. Bacterial sulfatases have been studied extensively in the past, with particular emphasis placed on those enzymes that lead to degradation of surfactants (5). Strains that are able to grow with alkylsulfates such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as the source of carbon are widespread in the environment, even in samples isolated from uncontaminated sites (23). A variety of alkylsulfatases is responsible for the hydrolysis reaction, often even within one species. The best-studied such strain is Pseudomonas sp. strain C12B (reviewed in reference 5), which displays a broad substrate tolerance even though the enzymes it contains are relatively substrate specific in terms of chain length and stereospecificity. Synthesis of these enzymes is controlled by a complex network of substrate and product induction (5).

Hydrolysis of aromatic sulfate esters, in contrast, is controlled in bacteria exclusively by the supply of sulfur to the cell, and is catalyzed by enzymes of the arylsulfatase family. These enzymes are common soil enzymes and, because they are easy to assay, are often used as a measure of soil quality (16). Synthesis of arylsulfatase is repressed during growth with inorganic sulfate or cysteine as the sulfur source and upregulated under sulfate-limiting conditions (e.g., during growth with sulfonates, sulfate esters, sulfamates, or methionine) (7). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the repressive effect in vivo was recently traced to two independent effectors—sulfite and either sulfide or cysteine (7)—whereas in Klebsiella pneumoniae, sulfate and cysteine repress arylsulfatase synthesis, also independently of each other (12).

The regulation of arylsulfatase synthesis is correlated with that of a group of so-called sulfate starvation-induced proteins, which were identified by differential two-dimensional electrophoresis (7, 13), and we have therefore used arylsulfatase as a model system for the sulfate starvation response. In this report, we show that, in P. aeruginosa, arylsulfatase is encoded together with a general transport system for both aliphatic and aromatic sulfate esters, and expression of this gene cluster requires the LysR-type transcriptional activator CysB.

Cloning and sequence analysis of the ats gene cluster.

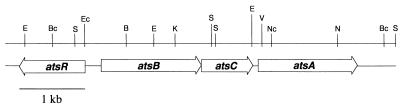

Previous studies of arylsulfatase in P. aeruginosa led to the identification and characterization of the atsA gene (1), but complementation studies with a DNA fragment carrying only this gene were unsuccessful. We therefore cloned and sequenced a region upstream of the atsA gene, in order to identify the promoter region from which atsA is expressed. Screening of a cosmid bank of P. aeruginosa yielded two cosmid clones carrying parts of the desired locus, and these were subcloned onto pBluescript (Stratagene) to give a 7-kb fragment on the plasmid pME4326. Sequencing of this fragment led to the identification of three further open reading frames, atsB, atsC, and atsR (Fig. 1). The genes atsB and atsC were carried as part of a putative operon with atsA, and overlapped each other by four nucleotides, whereas a fourth gene, atsR, was identified on the complementary strand, oriented divergently from atsBCA. The overall G+C content of the coding regions was 68.2%, although this dropped to 50% in the intergenic region between atsR and atsB.

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the ats locus of P. aeruginosa. Selected restriction sites are shown: B, BamHI; Bc, BclI; E, EcoRI; Ec, Eco47III; K, KpnI; N, NotI; Nc, NcoI; S, SalI; V, EcoRV.

Sequence analysis of the deduced AtsRBC proteins suggested that they represented an ABC-type transporter of unknown specificity. atsB encoded a 57.8-kDa polypeptide with 30 to 40% identity to known bacterial permeases. Hydrophobicity analysis with the program TMpred (6) predicted the presence of 12 membrane-spanning domains, and since the predicted AtsB protein is twice the size of related permeases (e.g., TauC of Escherichia coli, encoding the putative taurine permease [20], is 30 kDa in size), AtsB therefore corresponds as a monomer to the dimeric form of other permeases. The deduced AtsC protein was 31 kDa in size and was related (40 to 44% amino acid identity) to ATP-binding proteins of ABC-type transporters. The two Walker motifs which are characteristic of proteins of this family were present (GASGCGKST and LLLLDEPF [consensus residues underlined]), as was the so-called ABC signature, LSGG (11). The third open reading frame identified, atsR, encoded a 34-kDa protein carrying a putative N-terminal signal peptide. The AtsR protein was 25 to 42% identical to periplasmic substrate binding proteins involved in uptake of arylsulfatases or aliphatic sulfonates (21). These proteins are sufficiently similar that they have been proposed to form an independent family of binding proteins (21), adding to those previously defined by Tam and Saier (17).

AtsRBC proteins constitute a general sulfate ester transport system.

To further characterize the AtsRBC transporter, mutations were introduced into the atsR and atsB genes. The promoterless xylE::Gm cassette from the plasmid pX1918GT (15) was ligated into the Eco47III site in atsR (nucleotide 8 of atsR) and between the BamHI and EcoRI sites in atsB, respectively (Fig. 1). The resulting constructs were subcloned onto the suicide plasmid pME3087 (22) and transferred onto the P. aeruginosa PAO1 chromosome by homologous recombination. This yielded strains JH1 (atsR::xylE/Gm), in which the xylE was present as a transcriptional fusion to the atsR gene, and JH3 (atsB::Gm), where unfortunately we were only able to generate the construct with xylE in the reverse orientation to atsB. These strains, and the previously described strain, ATS1, which carries an 832-bp deletion in atsA (4), were grown in a succinate-mineral medium (1) with various sulfur sources (Table 1). Strain ATS1 was found to be defective only in growth with nitrocatechol sulfate, but strains JH1 and JH3 had lost the ability to grow with aromatic sulfates or medium-chain-length alkyl sulfates as the sulfur source. Complementation of these strains with the entire gene cluster on the broad-host-range vector pBBRMCS-3 (9) led to restoration of the wild-type phenotype (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the AtsRBC proteins constitute a general sulfate ester transporter which is involved in the uptake of both aromatic and aliphatic sulfate esters and also confirm the previous conclusion that the arylsulfatase is not involved in alkylsulfatase metabolism (1). Interestingly, JH1 and JH3 retained the ability to grow with SDS. This finding is consistent with previous studies of SDS degradation as a carbon source, which showed that the SDS sulfatase is periplasmically located (2, 5). In contrast to SDS sulfatase, however, the medium-chain-length sulfatase appears to be localized in the cytoplasm in P. aeruginosa, as is arylsulfatase (1).

TABLE 1.

Growth of P. aeruginosa strains with different sulfur sources

| Sulfur source | Relative growth of strain:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1S (wild type)a | JH1 (atsR::xylE) | JH3 (atsB::Gm) | ATS1 (ΔatsA) | |

| Sulfate | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Nitrocatechol sulfate | +++ | − | − | − |

| Hexyl sulfate | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| Octyl sulfate | +++ | − | − | +++ |

| Dodecyl sulfate | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Pentanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Methionine | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

Strain PAO1S is a spontaneously streptomycin-resistant derivative of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (1).

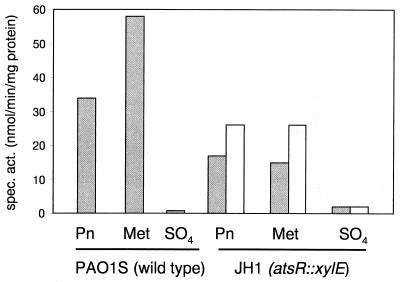

Arylsulfatase and catechol oxygenase activities in strain JH1 were measured by standard methods (1, 8) and showed that expression of the atsR gene was repressed during growth with sulfate, and upregulated during growth with organosulfur sources such as pentanesulfonate or methionine (Fig. 2). Arylsulfatase synthesis was also regulated in the same way, although the arylsulfatase levels were not as high as in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2). As expected, no arylsulfatase activity was seen in strain JH3, due to the polar effect of the atsB::Gm insertion on transcription of the atsA gene.

FIG. 2.

Arylsulfatase and catechol oxygenase activities in strain JH1. Cells were grown in succinate-minimal medium with pentanesulfonate (Pn), methionine (Met), or sulfate (SO4) as the sulfur source (250 μM), and were harvested in the mid-exponential phase. □, arylsulfatase activity; ░⃞, catechol oxygenase activity. Spec. act., specific activity.

Expression of atsR and atsBCA is controlled by CysB in P. aeruginosa.

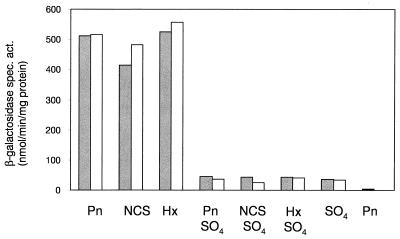

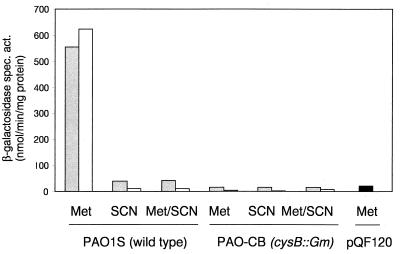

Expression of the atsR and atsB genes was now examined in the wild-type strain PAO1, by using transcriptional lacZ fusions constructed by cloning the atsR-atsB intergenic region in both orientations into the promoter probe plasmid pQF120 (14), to yield the plasmids pME4334 (atsR::lacZ) and pME4337 (atsB::lacZ). β-Galactosidase activities in mid-exponential-phase cells during growth with various sulfur sources were measured with o-nitrophenylgalactopyranoside (ONPG) as a substrate and are shown in Fig. 3. Both atsR and atsB were upregulated during growth with organosulfur sources, and repressed during growth with inorganic sulfate, even when the latter was combined with an organosulfur compound. The degree of downregulation in the presence of sulfate was consistent with that previously observed with the chromosomal atsR::xylE fusion (Fig. 2), demonstrating that copy number did not have an effect on the regulation. This suggested that expression might not be regulated by a direct repressor (there was no evidence for titration of a repressor protein in the presence of a high-copy-number reporter plasmid), but might be mediated by a positive regulator, such as the CysB protein. CysB is a LysR-type transcriptional activator which has been well characterized in enteric bacteria (10), where it activates transcription of the cys biosynthetic genes in the presence of the coinducer N-acetylserine, and during sulfur limitation. It has recently also been reported in P. aeruginosa, where it plays a role in algD expression (3), and is required for growth with a variety of organosulfur compounds (8). We therefore tested expression of the atsB::lacZ and atsR::lacZ fusion constructs in the cysB::Gm mutant strain PAO-CB (8). Because this strain is auxotrophic for cysteine, we were unable to use sulfate as a repressing growth substrate, and we substituted it with thiocyanate, which also represses arylsulfatase expression in this species (7). No expression of the atsB or atsR gene was observed under derepressing conditions in the absence of a functional CysB protein (Fig. 4). We therefore conclude that the atsR and atsBCA genes are new members of the cys regulon in P. aeruginosa, and the CysB protein clearly controls not just cysteine biosynthesis, but also the cleavage of organosulfur compounds to release inorganic sulfur for cysteine biosynthesis. However, when the atsRBCA cluster was introduced into E. coli, no synthesis of arylsulfatase was observed, and the cells were unable to grow with aromatic sulfates, despite the presence of an active E. coli cysB gene. It is not yet clear whether this effect is due to specificity of the P. aeruginosa CysB protein, but not the E. coli CysB protein, for binding sites in the atsR-atsB intergenic region, or whether additional species-specific factors are required for expression of the ats genes. Such factors are known for the sulfur-regulated sulfonatase systems asf in Pseudomonas putida (21) and tau/ssu in E. coli (18, 19), which in addition to CysB also require the LysR-type regulators AsfR and Cbl, respectively, for expression. Further work to elucidate this is ongoing in our laboratory.

FIG. 3.

Regulation of atsR::lacZ and atsB::lacZ expression in P. aeruginosa PAO1S. Cells were grown in succinate-minimal medium with pentanesulfonate (Pn), methionine (Met), nitrocatechol sulfate (NCS), hexyl sulfate (Hx), or sulfate (SO4) as the sulfur source and were harvested in the mid-exponential phase. β-Galactosidase specific activity (spec. act.) was measured with ONPG as the substrate. ░⃞, atsR::lacZ (pME4334); □, atsB::lacZ (pME4337); ■, vector control (pQF120).

FIG. 4.

Effect of cysB on atsB and atsR expression in P. aeruginosa. Cells were grown in succinate-minimal medium with methionine (Met), thiocyanate (SCN), or both as the sulfur sources and were harvested in the mid-exponential phase. Expression of atsB::lacZ and atsR::lacZ was measured as β-galactosidase activity in the wild-type strain PAO1S or in the cysB mutant PAO-CB. ░⃞, atsR::lacZ (pME4333); □, atsB::lacZ (pME4337); ■, vector control PAO1S(pQF120).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been included with the previously published atsA sequence (1) and is available under accession no. Z48540.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 31-49435.96) and the Swiss Federal Office for Education and Sciences (grant no. 97.0190, as part of the EC program SUITE, contract no. ENV4-CT98-0723).

We thank Paul Vermeij and Claudia Wietek for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beil S, Kehrli H, James P, Staudenmann W, Cook A M, Leisinger T, Kertesz M A. Purification and characterization of the arylsulfatase synthesized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO during growth in sulfate-free medium and cloning of the arylsulfatase gene (atsA) Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:385–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0385k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison J, Brunel F, Phanopoulos A, Prozzi D, Terpstra P. Cloning and sequencing of Pseudomonasgenes determining sodium dodecyl sulfate biodegradation. Gene. 1992;114:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90702-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delic-Attree I, Toussaint B, Garin J, Vignais P M. Cloning, sequence and mutagenesis of the structural gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa CysB, which can activate algDtranscription. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1275–1284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4121799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dierks T, Miech C, Hummerjohann J, Schmidt B, Kertesz M A, von Figura K. Posttranslational formation of formylglycine in prokaryotic sulfatases by modification of either cysteine or serine. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25560–25564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodgson K S, White G F, Fitzgerald J W. Sulfatases of microbial origin. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. TMBASE—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1993;374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummerjohann J, Kuttel E, Quadroni M, Ragaller J, Leisinger T, Kertesz M A. Regulation of the sulfate starvation response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: role of cysteine biosynthetic intermediates. Microbiology. 1998;144:1375–1386. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kertesz M A, Schmidt-Larbig K, Wüest T. A novel reduced flavin mononucleotide-dependent methanesulfonate sulfonatase encoded by the sulfur-regulated msu operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1464–1473. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1464-1473.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovach M E, Elzer P H, Hill D S, Robertson G T, Farris M A, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kredich N M. Biosynthesis of cysteine. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 514–527. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linton K J, Higgins C F. The Escherichia coliATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:5–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murooka Y, Adachi T, Okamura H, Harada T. Genetic control of arylsulfatase synthesis in Klebsiella aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:74–81. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.74-81.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quadroni M, James P, Dainese-Hatt P, Kertesz M A. Proteome mapping, mass spectrometric sequencing and reverse transcriptase-PCR for characterisation of the sulfate starvation-induced response in Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO1. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:986–996. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronald S L, Kropinski A M, Farinha M A. Construction of broad-host-range vectors for the selection of divergent promoters. Gene. 1990;90:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90451-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schweizer H P, Hoang T T. An improved system for gene replacement and xylE fusion analysis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1995;158:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00055-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stott D E, Hagedorn C. Interrelations between selected soil characteristics and arylsulfatase and urease activities. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1980;11:935–955. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tam R, Saier M H., Jr Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:320–346. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.320-346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Ploeg J R, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Bykowski T, Hryniewicz M, Leisinger T. The Cbl-regulated ssuEADCB gene cluster is required for aliphatic sulfonate-sulfur utilization in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;174:29358–29365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Ploeg J R, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Kertesz M A, Leisinger T, Hryniewicz M M. Involvement of CysB and Cbl regulatory proteins in expression of the tauABCD operon and other sulfate starvation-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7671–7678. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7671-7678.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Ploeg J R, Weiss M A, Saller E, Nashimoto H, Saito N, Kertesz M A, Leisinger T. Identification of sulfate starvation-regulated genes in Escherichia coli: a gene cluster involved in the utilization of taurine as a sulfur source. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5438–5446. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5438-5446.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeij P, Wietek C, Kahnert A, Wüest T, Kertesz M A. Genetic organization of sulfur-controlled aryl desulfonation in Pseudomonas putidaS-313. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:913–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voisard C, Bull C T, Keel C, Laville J, Maurhofer M, Schnider U, Défago G, Haas D. Biocontrol of root diseases by Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: current concepts and experimental approaches. In: O'Gara F, Dowling D N, Boesten B, editors. Molecular ecology of rhizosphere microorganisms. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1994. pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- 23.White G F, Russell N J, Day M J. A survey of sodium dodecyl-sulfate (SDS) resistance and alkylsulfatase production in bacteria from clean and polluted river sites. Environ Poll Ser Ecol Biol. 1985;37:1–11. [Google Scholar]