Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy presents a risk for maternal mental health problems, preterm birth, and having a low birthweight infant. We assessed the prevalence of self-reported physical, emotional, and sexual violence during pregnancy by a current partner among women with a recent live birth. We analyzed data from the 2016–2018 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System in six states to calculate weighted prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals for experiences of violence by demographic characteristics, health care utilization, and selected risk factors. Overall, 5.7% of women reported any type of violence during pregnancy. Emotional violence was most prevalent (5.4%), followed by physical violence (1.5%), and sexual violence (0.9%). Among women who reported any violence, 67.6% reported one type of violence, 26.5% reported two types, and 6.0% reported three types. Reporting any violence was highest among women using marijuana or illicit substances, experiencing pre-pregnancy physical violence, reporting depression, reporting an unwanted pregnancy, and experiencing relationship problems such as getting divorced, separated, or arguing frequently with their partner. There was no difference in report of discussions with prenatal care providers by experience of violence. The majority of women did not report experiencing violence, however among those who did emotional violence was most frequently reported. Assessment for IPV is important, and health care providers can play an important role in screening. Coordinated prevention efforts to reduce the occurrence of IPV and community-wide resources are needed to ensure that pregnant women receive needed services and protection.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Intimate partner violence, Emotional violence, PRAMS

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as physical violence, stalking, psychological harm, or sexual violence perpetrated by a romantic or sexual partner, affects one in four women in the United States (CDC, 2020). Women who experience IPV are at an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. They experience higher rates of chronic health conditions; musculoskeletal, and female reproductive disorders; sexually transmitted diseases (Bonomi et al., 2009; Stubbs & Szoeke, 2021); psychosocial/mental (Bonomi et al., 2009) and substance use disorders (Afifi et al., 2012). Physical violence can lead to injuries such as bruises and broken bones, traumatic brain injuries, and death (Chisholm et al., 2017a, b; Morrison et al., 2020; Sarkar, 2008). Physical violence, as well as emotional violence and sexual violence, are associated with poor mental health including depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Chisholm et al., 2017a, b; Hahn et al., 2018; Paulson, 2020; Sarkar, 2008).

IPV victimization may escalate during pregnancy for some women, and studies have found a nearly two-fold increase in homicide of pregnant compared to non-pregnant women (Morrison et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2021). IPV during pregnancy is also associated with maternal and infant risk factors and adverse outcomes including inadequate prenatal care and lower attendance at well-child visits (Wolf et al., 2021), lower breastfeeding rates (Normann et al., 2020; Sarkar, 2008), and higher risk for preterm and low birth weight infants (Sarkar, 2008). This has implications for intergenerational transmission of risk as many of the aforementioned factors increase the likelihood that children will experience adversity during key developmental years which has been shown to predict poor health and social outcomes across the life course (CDC, 2019).

The aim of this study is to provide recent weighted population-based estimates on the prevalence of self-reported physical, emotional, and sexual violence by a current partner during pregnancy among women with a recent live birth. We also describe maternal characteristics, prenatal care utilization, maternal risk factors, financial stressors, and partner stressors of women who report violence by type of violence reported. This information can be used to understand the magnitude of IPV victimization during pregnancy and help target prevention efforts, screenings, interventions, and resources to identify and protect affected women, infants, and families.

Methods

Study Population

We analyzed 2016–2018 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data from six states in the United States (US) (Arkansas, Kansas, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Washington, Wisconsin). PRAMS is a state-specific, population-based surveillance system conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with state, city, and territorial health departments. PRAMS generates cross-sectional survey data. Using a standardized data collection protocol, each participating state draws a stratified random sample of women from recent birth certificate records every month. Women are sampled 2 to 6 months after a live birth and are mailed up to three surveys. Non-respondents are contacted to complete the survey by telephone. Data are weighted to account for the PRAMS complex survey design prior to analysis. Details of the PRAMS methodology have been described previously (Shulman et al., 2018). The PRAMS study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of CDC and each participating state.

Measures

Maternal demographic characteristics including age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and urban/rural residence are from the linked birth certificate file. Urban/rural residence is based on the National Center for Health Statistics classification of county of residence. Large Central Metro, Large Fringe Metro, Medium Metro, and Small Metro are grouped together in the ‘Urban’ group, while Micropolitan and Noncore are grouped together in the ‘Rural’ group.

Information on physical violence during pregnancy is available for all states; however, we restricted our analysis to states which included an optional question on their survey about the experience of emotional and sexual violence during pregnancy. Physical violence by a current intimate partner was defined as a response of “yes” to the option “My husband or partner” in response to the question: “During your most recent pregnancy, did any of the following people push, hit, slap, kick, choke, or physically hurt you in any other way?”.

Emotional and sexual violence were assessed based on responses to a question that asked each respondent if her husband or partner did any of the following during her most recent pregnancy: a) threatened or made her feel unsafe in some way, b) made her frightened for her safety or her family’s safety because of the partner’s anger or threats, c) tried to control her daily activities, for example, controlling who she could talk to or where she could go, and d) forced her to take part in touching or any sexual activity when she did not want to. Women who responded “yes” to items a, b, or c were considered to have experienced emotional violence. Women who responded “yes” to item d were considered to have experienced sexual violence.

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence of reporting any violence and the type of violence was estimated overall, and by maternal characteristics including age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status with unmarried women further stratified by acknowledgement of paternity (i.e., presence of documentation adding father’s name to the birth record), and urban/rural residence. We examined violence by selected factors from the PRAMS questionnaire including: health care related factors (health insurance for prenatal care; timing of prenatal care initiation; if a prenatal care provider asked if the respondent was being hurt emotionally or physically during pregnancy), risk factors before pregnancy (pregnancy intention; cigarette smoking; heavy drinking; marijuana or illicit drug use; depression; experience of previous physical violence by an intimate partner), and risk factors during pregnancy (cigarette smoking; any drinking; marijuana or illicit drug use; depression). We also examined experience of financial (job loss or cut in hours for respondent or partner; problems paying bills) and partner or relationship stressors (partner did not want the pregnancy; divorced or separated from husband or partner, or frequent arguing) in the 12 months before delivery. Only a subset of states used the indicators on alcohol use during pregnancy (Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Washington) and financial stressors and partner stressors (Kansas, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin). Using the weighted data, weighted prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using SUDAAN (version 11.0; RTI International). Subgroup differences in experience of self-reported violence were ascertained using non-overlapping 95% confidence interval estimates of the weighted prevalence. This typically conservative approach might fail to note differences between estimates more often than formal statistical testing. Overlap between CIs does not necessarily mean that there is no statistical difference between estimates.

There were 15,592 respondents across the six study states representing the 964,156 women who gave birth to live infants in those states during the years included in the study. The unweighted sample size is presented on the tables with the weighted prevalence and corresponding confidence intervals.

Results

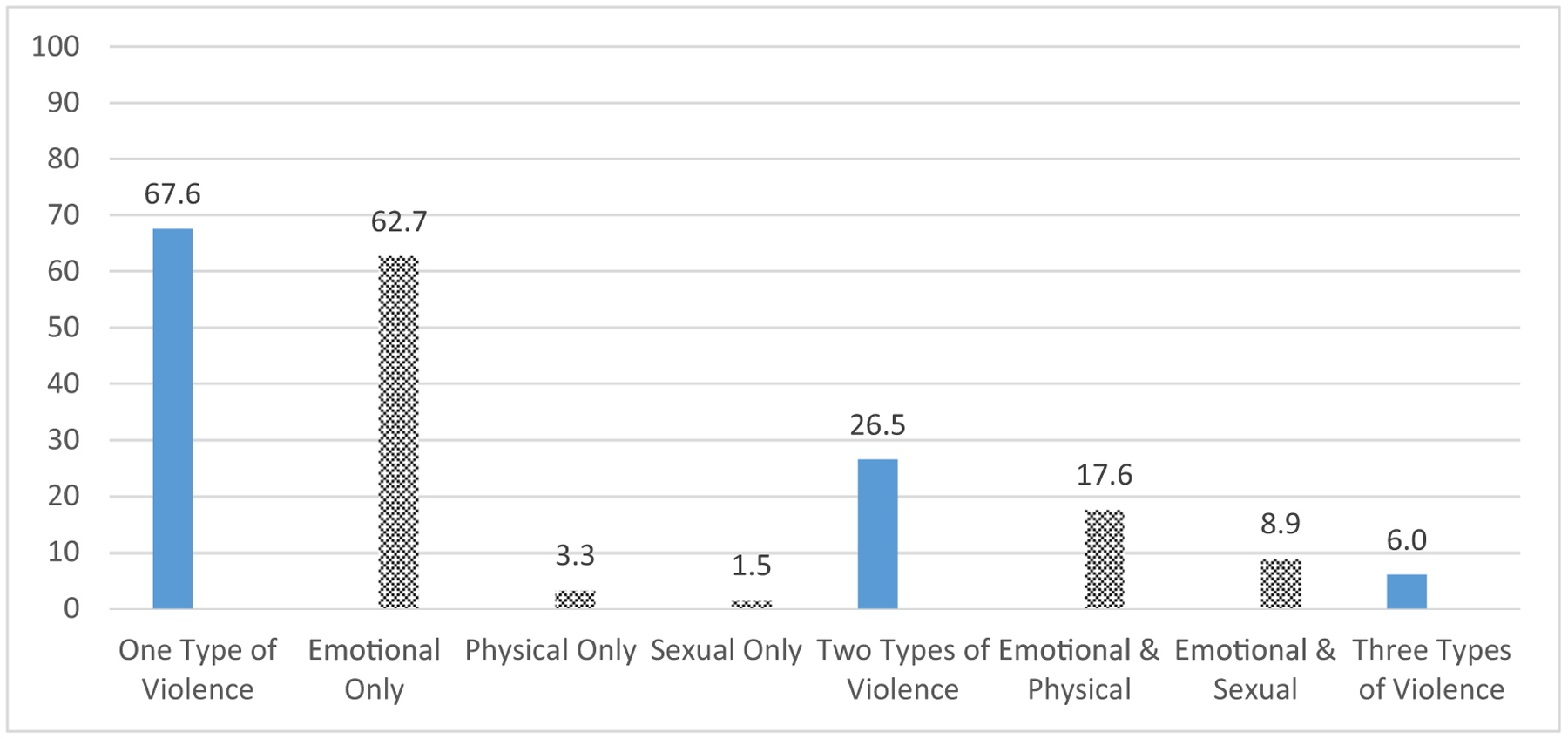

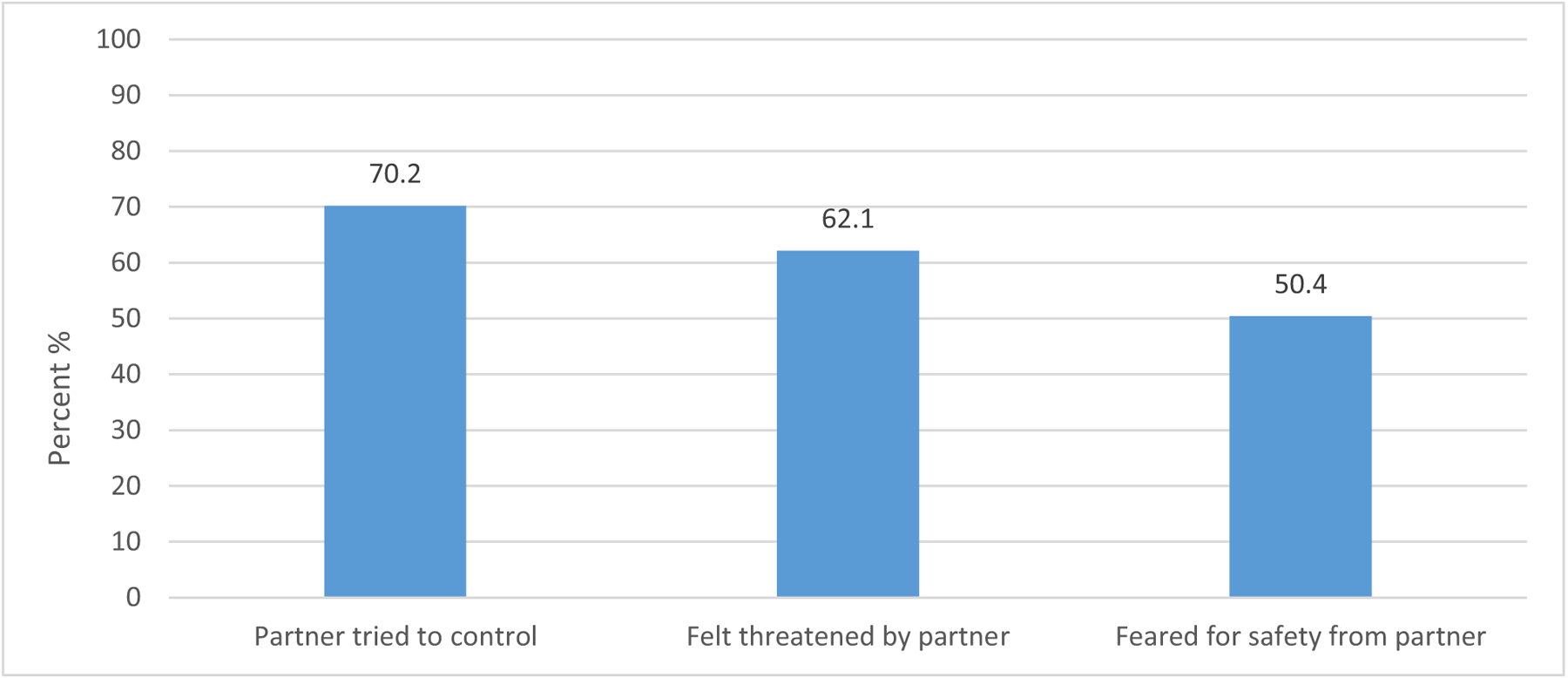

Overall, 5.7% of women (n = 1050) reported experiencing any violence during pregnancy by a current intimate partner; emotional violence was most common (5.4%; n = 991), followed by physical (1.5%; n = 312), and sexual violence (0.9%; n = 178) (Table 1). Among women reporting any violence during pregnancy, 67.6% reported one type of violence, 26.5% reported two types of violence, and 6.0% reported three types of violence (Fig. 1). Among women who reported emotional violence, 70.2% reported their partner tried to control their activities, 62.1% reported that their partner threatened them, and 50.4% reported that their partner made them fearful for their safety (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Emotional, Physical, or Sexual Violence during Pregnancy by a Current Partner among Women with a Recent Live Birth by Selected Maternal Characteristics, 2016—2018

| Maternal Characteristics | Any Violence (n = 1050) | Emotional Violencea (n = 991) |

Physical Violenceb (n = 312) |

Sexual Violencec (n = 178) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n d | % e | 95% CI | % e | 95% CI | % e | 95% CI | % e | 95% CI | |

| Total | 15,592 | 5.7 | 5.2–6.3 | 5.4 | 4.9–6.0 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.8 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 |

| Age | |||||||||

| < 20 | 812 | 15.1 | 11.2–20.1 | 14.9 | 11.0–19.8 | 2.8 | 1.4–5.4 | 2.0 | 0.9–4.1 |

| 20–24 | 2943 | 9.2 | 7.7–11.1 | 8.5 | 7.0–10.2 | 2.1 | 1.4–3.2 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.3 |

| 25–34 | 9365 | 4.7 | 4.1–5.3 | 4.5 | 3.9–5.1 | 1.5 | 1.2–1.9 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.2 |

| 35 + | 2471 | 3.8 | 2.9–5.0 | 3.7 | 2.8–4.9 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.1 | 0.5 | 0.3–1.0 |

| Race/Ethnicityf | |||||||||

| White | 7123 | 5.1 | 4.5–5.8 | 4.9 | 4.3–5.6 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.6 | 0.8 | 0.6–1.1 |

| Black | 3088 | 9.0 | 7.2–11.3 | 8.2 | 6.5–10.4 | 3.4 | 2.3–5.1 | 1.8 | 1.0–3.2 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1014 | 12.8 | 10.1–16.0 | 12.5 | 9.8–15.7 | 4.0 | 2.9–5.5 | 3.6 | 2.0–6.4 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1222 | 3.6 | 2.4–5.3 | 3.3 | 2.2–4.8 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.8 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.7 |

| Mixed/other race | 1073 | 10.2 | 7.1–14.4 | 9.3 | 6.3–13.5 | 1.8 | 0.9–3.3 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.4 |

| Hispanic | 2017 | 5.9 | 4.7–7.4 | 5.5 | 4.4–7.0 | 1.6 | 1.0–2.6 | 0.6 | 0.4–1.1 |

| Education level (years) | |||||||||

| < 12 | 2033 | 9.0 | 7.2–11.3 | 8.8 | 7.0–11.0 | 1.3 | 0.7–2.2 | 1.5 | 0.8–2.8 |

| 12 | 3952 | 8.0 | 6.8–9.4 | 7.4 | 6.2–8.7 | 2.2 | 1.6–3.1 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.3 |

| > 12 | 9484 | 4.2 | 3.7–4.9 | 4.0 | 3.5–4.7 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.6 | 0.6 | 0.4–0.8 |

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Married | 9052 | 2.6 | 2.2–3.0 | 2.4 | 2.0–2.9 | 0.7 | 0.5–1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.6 |

| Unmarried with AOP | 3686 | 8.6 | 7.3–10.1 | 8.1 | 6.8–9.5 | 2.2 | 1.5–3.0 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.4 |

| Unmarried without AOP | 2490 | 17.7 | 15.1–20.6 | 16.9 | 14.3–19.7 | 4.8 | 3.5–6.5 | 4.3 | 3.0–6.2 |

| Residenceg | |||||||||

| Urban | 12,205 | 5.4 | 4.8–6.0 | 5.1 | 4.5–5.7 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.8 | 0.8 | 0.6–1.1 |

| Rural | 3384 | 7.4 | 6.1–9.0 | 7.1 | 5.9–8.7 | 1.9 | 1.3–2.8 | 1.3 | 0.8–2.2 |

| Health Insurance for Prenatal Care | |||||||||

| Private | 8340 | 3.2 | 2.7–3.7 | 3.0 | 2.5–3.5 | 0.7 | 0.5–1.0 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 |

| Medicaid | 5465 | 10.6 | 9.4–12.1 | 10.2 | 9.0–11.6 | 2.9 | 2.2–3.7 | 1.8 | 1.3–2.5 |

| None | 347 | 3.1 | 1.6–6.0 | 2.6 | 1.3–5.2 | 1.2 | 0.3–4.6 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.4 |

| Trimester of entry into prenatal care | |||||||||

| First | 13,052 | 5.0 | 4.5–5.5 | 4.8 | 4.3–5.3 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.6 | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 |

| After first or none | 2185 | 10.1 | 8.3–12.4 | 9.4 | 7.6–11.6 | 2.6 | 1.7–3.9 | 2.6 | 1.7–3.9 |

| Prenatal Provider discussed violence | |||||||||

| Yes | 11,700 | 5.9 | 5.3–6.6 | 5.6 | 5.0–6.3 | 1.5 | 1.2–1.9 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 |

| No | 3406 | 4.5 | 3.6–5.6 | 4.3 | 3.4–5.4 | 1.3 | 0.9–2.0 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 |

Abbreviations: CI confidence interval, AOP acknowledgement of paternity

Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data from six states: Arkansas (2016), Kansas (2017, 2018), Pennsylvania (2016, 2017, 2018), South Dakota (2017, 2018), Washington (2016, 2017, 2018), Wisconsin (2016, 2017, 2018)

Respondent indicated yes to: ‘My husband or partner threatened me or made me feel unsafe in some way,’ or ‘I was frightened for my safety or my family’s safety because of the anger or threats of my husband or partner’ or ‘My husband or partner tried to control my daily activities, for example, controlling who I could talk to or where I could go’ during pregnancy

Respondent indicated yes to husband or partner doing any of the following during pregnancy: ‘hit, slap, kick, choke, or physically hurt you in any way’

Respondent indicated yes to: ‘my husband or partner forced me to take part in touching or any sexual activity when I did not want to’ during pregnancy

Total unweighted sample size; sample size varies due to missing responses

Weighted prevalence (expressed as a percentage)

Race/ethnicity categories are non-Hispanic White, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asia/Pacific Islander, Mixed/Other race and Hispanic of any race

Urban/rural residence based on National Center for Health Statistics classification for county of residence: Large Central Metro, Large Fringe Metro, Medium Metro, and Small Metro are in the ‘Urban’ group; Micropolitan and Noncore are in the ‘Rural’ group https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm

Fig. 1.

Co-occurrence of Multiple Types of Violence among Women with a Live Birth who Experienced Any Violence during Pregnancy by a Current Partner, 2016–2018a. aPregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data from six states: Arkansas (2016), Kansas (2017, 2018), Pennsylvania (2016, 2017, 2018), South Dakota (2017, 2018), Washington (2016, 2017, 2018), Wisconsin (2016, 2017, 2018). For two types of violence, no respondent reported experiencing physical and sexual violence

Fig. 2.

Type of Emotional Violence Experienced during Pregnancy among Women with a Live Birth who Experienced Emotional Violence by a Current Partner, 2016–2018a. aPregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data from six states: Arkansas (2016), Kansas (2017, 2018), Pennsylvania (2016, 2017, 2018), South Dakota (2017, 2018), Washington (2016, 2017, 2018), Wisconsin (2016, 2017, 2018)

Considering maternal demographic characteristics and prenatal care, the highest prevalence of reporting emotional violence during pregnancy was among women aged < 20 years (14.9%) and 20–24 years (8.5%) compared with older women (4.5% for 25–34 year olds; 3.7% for 35 years and older), American Indian or Alaska Native women (12.5%), mixed race women (9.3%), and Black women (8.2%) compared with White women (4.9%), those who were unmarried with and without acknowledgement of paternity (8.1% and 16.9%, respectively) compared with married women (2.4%), women with Medicaid coverage for prenatal care (10.2%) compared with those with private insurance (3.0%), and women with delayed prenatal care who entered care in the second trimester, later, or not at all (9.4%) compared with those who entered in the first trimester (4.8%) (Table 1).

Similar to emotional violence, physical violence was lower among women aged 35 years or older (0.6%) compared with younger women (2.8% for < 20 years old; 2.1% for 25–34 years old; 1.5% for 35 years and older), and was higher among Black women (3.4%), American Indian or Alaska Native women (4.0%) compared with White women (1.3%) and Asian or Pacific Islander women (0.8%), those who were unmarried with and without acknowledgement of paternity (2.2% and 4.8%, respectively) compared with married women (0.7%), women with Medicaid (2.9%) compared with women with private insurance (0.7%), and women with late or no entry into prenatal care (2.6%) compared with those reporting first trimester care (1.3%) (Table 1).

Sexual violence was higher among American Indian or Alaska Native women (3.6%) compared with White women (0.8%), women with only a high school education (1.5%) compared with those with more than a high school education (0.6%), unmarried women without acknowledgement of paternity (4.3%) compared with unmarried women with acknowledgement of paternity (0.9%) and married women (0.4%), Medicaid recipients (1.8%) compared with those with private insurance (0.4%) and women with delayed or no prenatal care (2.6%) compared with those with first trimester care (0.7%) (Table 1).

A higher prevalence of all three types of violence (emotional, physical and sexual) was reported among women with, compared with those without, selected risk factors before pregnancy including smoking cigarettes (emotional: 12.3%, physical: 3.4%, sexual: 2.6%), using marijuana or illicit substances (emotional: 20.1%, physical: 5.4%, sexual: 2.5%), reporting depression before pregnancy (emotional: 15.5%, physical: 4.1%, sexual: 3.4%), experiencing pre-pregnancy physical violence by an intimate partner (emotional: 64.3%, physical: 35.6%, sexual: 17.0%), and having an unwanted pregnancy (emotional: 14.0%; physical: 3.5%; sexual; 1.1%). Patterns were similar for related risk factors during pregnancy, as well (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Emotional, Physical or Sexual Violence during Pregnancy by a Current Partner among Women with a Recent Live Birth by Selected Behavioral Risk Factors, Experiences, and Stressors, 2016–2018

| Risk Factors and Stressors | Any Violence (n = 1050) | Emotional Violencea (n = 991) | Physical Violenceb (n = 312) | Sexual Violencec (n = 178) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nd | %e | 95% CI | %e | 95% CI | %e | 95% CI | %e | 95% CI | |

| Risk Factors Before Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Cigarette Smoking 3 Months Before Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 3223 | 13.0 | 11.3–14.9 | 12.3 | 10.6–14.2 | 3.4 | 2.6–4.5 | 2.6 | 1.8–3.6 |

| No | 12,100 | 3.9 | 3.4–4.5 | 3.7 | 3.3–4.2 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4–0.7 |

| Heavy Drinking 3 Months Before Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 422 | 7.9 | 5.0–12.3 | 7.7 | 4.8–12.1 | 3.3 | 1.6–6.7 | 1.5 | 0.5–4.8 |

| No | 14,787 | 5.6 | 5.1–6.2 | 5.3 | 4.8–5.9 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.7 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 |

| Used Marijuana or Illicit Substance during the Month Before Pregnancyf | |||||||||

| Yes | 625 | 21.8 | 16.4–28.4 | 20.1 | 14.9–26.7 | 5.4 | 3.2–8.9 | 2.5 | 1.5–4.0 |

| No | 4888 | 4.7 | 3.9–5.8 | 4.5 | 3.6–5.6 | 1.3 | 0.9–1.8 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.0 |

| Depression | |||||||||

| Yes | 2487 | 16.4 | 14.2–18.8 | 15.5 | 13.4–17.8 | 4.1 | 3.0–5.5 | 3.4 | 2.5–4.8 |

| No | 12,955 | 3.8 | 3.4–4.3 | 3.6 | 3.2–4.1 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.5 | 0.3–0.7 |

| Experienced Physical Violence by an intimate partnerg | |||||||||

| Yes | 628 | 67.5 | 61.0–73.3 | 64.3 | 57.9–70.3 | 35.6 | 29.5–42.1 | 17.0 | 12.5–22.7 |

| No | 14,588 | 3.8 | 3.3–4.3 | 3.6 | 3.1–4.0 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 |

| Pregnancy Intentionh | |||||||||

| Unwanted | 1015 | 14.1 | 10.9–18.0 | 14.0 | 10.8–17.9 | 3.5 | 2.0–6.1 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 |

| Unsure | 2661 | 9.1 | 7.5–10.9 | 8.8 | 7.2–10.6 | 2.5 | 1.7–3.6 | 2.1 | 1.4–3.2 |

| Mistimed | 3029 | 8.7 | 7.3–10.4 | 8.1 | 6.7–9.8 | 2.2 | 1.5–3.1 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.4 |

| Intended | 8581 | 3.2 | 2.7–3.8 | 3.0 | 2.5–3.6 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.7 |

| Risk Factors During Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Smoking in the Last 3 Months of Pregnancy | |||||||||

| Yes | 1642 | 16.2 | 13.5–19.3 | 15.6 | 13.0–18.6 | 4.2 | 3.0–6.0 | 3.5 | 2.3–5.3 |

| No | 13,696 | 4.6 | 4.1–5.1 | 4.3 | 3.8–4.8 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.5 | 0.6 | 0.5–0.9 |

| Any Drinking in the Last 3 Months of Pregnancyi | |||||||||

| Yes | 638 | 5.8 | 3.8–8.8 | 5.8 | 3.8–8.8 | 2.7 | 1.4–5.2 | 1 | 0.3–3.2 |

| No | 8143 | 5.4 | 4.7–6.1 | 5.1 | 4.4–5.8 | 1.4 | 1.0–1.8 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.2 |

| Use of Marijuana or Illicit Substance during Pregnancyj | |||||||||

| Yes | 460 | 26.5 | 20.0–34.3 | 24.9 | 18.5–32.6 | 7.3 | 4.8–11.1 | 5.9 | 3.5–9.8 |

| No | 6978 | 5.4 | 4.6–6.3 | 5.1 | 4.4–6.0 | 1.4 | 1.0–1.8 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.2 |

| Depression | |||||||||

| Yes | 2411 | 17.7 | 15.5–20.3 | 17.0 | 14.7–19.5 | 4.6 | 3.5–6.1 | 3.7 | 2.7–5.1 |

| No | 12,833 | 3.7 | 3.3–4.2 | 3.5 | 3.0–4.0 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.5 | 0.3–0.7 |

| Stressors in the 12 Months Before Delivery | |||||||||

| Job Loss or Cut in Hoursk | |||||||||

| Yes | 3015 | 12.9 | 11.3–14.8 | 12.3 | 10.7–14.1 | 3.7 | 2.9–4.8 | 2.5 | 1.8–3.5 |

| No | 9395 | 3.6 | 3.1–4.1 | 3.4 | 2.9–3.9 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3–0.7 |

| Problems Paying Billsl | |||||||||

| Yes | 2067 | 16.7 | 14.4–19.2 | 16.1 | 13.9–18.5 | 5.0 | 3.8–6.6 | 2.6 | 1.8–3.8 |

| No | 10,375 | 3.7 | 3.2–4.3 | 3.5 | 3.0–4.0 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5–0.9 |

| Partner did not want the pregnancym | |||||||||

| Yes | 849 | 33.0 | 28.3–38.0 | 32.0 | 27.4–37.0 | 10.5 | 7.8–14.0 | 8.8 | 6.2–12.4 |

| No | 11,582 | 3.9 | 3.5–4.5 | 3.7 | 3.2–4.2 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 |

| Divorced, separated, or frequent arguingn | |||||||||

| Yes | 2900 | 22.1 | 19.9–24.4 | 21.2 | 19.0–23.5 | 6.5 | 5.3–8.0 | 3.6 | 2.8–4.8 |

| No | 9523 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.4 |

Abbreviation: CI confidence interval

Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data from six states: Arkansas (2016), Kansas (2017, 2018), Pennsylvania (2016, 2017, 2018), South Dakota (2017, 2018), Washington (2016, 2017, 2018), Wisconsin (2016, 2017, 2018)

Respondent indicated yes to: ‘My husband or partner threatened me or made me feel unsafe in some way,’ or ‘I was frightened for my safety or my family’s safety because of the anger or threats of my husband or partner’ or ‘My husband or partner tried to control my daily activities, for example, controlling who I could talk to or where I could go’ during pregnancy

Respondent indicated yes to husband or partner doing any of the following during pregnancy: ‘hit, slap, kick, choke, or physically hurt you in any way’

Respondent indicated yes to: ‘my husband or partner forced me to take part in touching or any sexual activity when I did not want to’ during pregnancy

Unweighted sample size; sample size varies due to missing responses

Weighted prevalence (expressed as a percentage)

Respondent indicated yes to using one or more of the following: Synthetic marijuana (K2, Spice), Heroin (smack, junk, Black Tar, Chiva), Amphetamines (uppers, speed, crystal meth, crank, ice, agua), Cocaine (crack, rock, coke, blow, snow, nieve), Tranquilizers (downers, ludes), Hallucinogens (LSD/acid, PCP/angel dust, Ecstasy, Molly, mushrooms, bath salts); indicators used by South Dakota and Wisconsin

Respondent indicated yes to husband or partner or ex-husband/ex-partner doing any of the following during the 12 months before getting pregnant: ‘hit, slap, kick, choke, or physically hurt you in any way’

Respondent reported that just before getting pregnant, feelings about the pregnancy were: didn’t want to be pregnant then or any time in the future (unwanted), wasn’t sure what wanted (unsure), wanted to be pregnant later (mistimed), wanted to be pregnant then or sooner (intended)

Indicator used by Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Washington

Respondent indicated yes to using one or more of the following: Synthetic marijuana (K2, Spice), Heroin (smack, junk, Black Tar, Chiva), Amphetamines (uppers, speed, crystal meth, crank, ice, agua), Cocaine (crack, rock, coke, blow, snow, nieve), Tranquilizers (downers, ludes), Hallucinogens (LSD/acid, PCP/angel dust, Ecstasy, Molly, mushrooms, bath salts); indicators used by Kansas, South Dakota, Wisconsin

Respondent reported that she or her husband or partner lost their job or had a cut in work hours or pay in the 12 months before the baby was born; indicator used by Kansas, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin

Respondent reported having trouble paying the rent, mortgage or other bills in the 12 months before the baby was born; indicator used by Kansas, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin

Respondent reported that husband or partner said they didn’t want her to be pregnant; indicator used by Kansas, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin

Respondent reported that getting separated or divorce or arguing with her husband or partner more than usual in the 12 months before the baby was born; indicator used by Kansas, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin

Reported experiences of violence also varied by financial stressors and relationship factors during the 12 months before delivery. These indicators were available for four of the six states (Kansas, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin). Women reporting job loss or cut in hours were more likely to report violence (emotional: 12.3%, physical: 3.7%, sexual: 2.5%), as were women who reported problems paying bills (emotional: 16.1%, physical: 5.0%, sexual: 2.6), than were women who did not have these stressors. In addition, women who reported having a partner who did not want the pregnancy (emotional: 32.0%, physical: 10.5%, sexual: 8.8%), and being divorced, separated or arguing frequently with their husband or intimate partner in the 12 months before delivery of their new baby (emotional: 21.2%, physical: 6.5%, sexual: 3.6%) were more likely to report violence compared with women without these risk factors (Table 2).

Discussion

Overall, 6% of women reported emotional, physical, or sexual violence during pregnancy by a current intimate partner in six US states. Aggregated estimates of physical violence from PRAMS sites in 2016 through 2019 have been reported between 2–3%, however emotional and sexual violence during pregnancy have not been reported using PRAMS data (CDC, 2021). A notably larger prevalence of IPV is observed when considering emotional and sexual violence along with physical violence. Other estimates of perinatal IPV range between 3–9% (Hahn et al., 2018). Emotional violence, sometimes referred to as psychological violence or coercive control, encompasses behaviors such as yelling, insulting, bullying, threatening, and controlling activities, financial resources, and contacts with other people. Also, though studies have linked emotional violence alone to mental, physical, and functional limitations (Heise et al., 2019), the predominant pattern is that it is often a precursor to later physical violence (Murphy & O’Leary, 1989; O’Leary, 1999), and occurs in concert with physical and sexual violence (Heise et al., 2019). Findings from this study indicate not only that emotional violence was the most frequently reported of the three types of IPV, but also that over a quarter of women who reported IPV experienced more than one type of violence, such as emotional violence in combination with physical violence (17.6%) or emotional violence with sexual violence (8.9%).

The experience of IPV during pregnancy can have short- and long-term health effects. This study corroborates the findings from other studies that women who experienced violence were more likely than women not reporting violence to smoke cigarettes (Cheng et al., 2015) and use of illicit substances before and during pregnancy (Hahn et al., 2018; Salom et al., 2015). They were also more likely to self-report depression before and during pregnancy (Paulson, 2020). Substance use and mental health disorders have been found to be correlated with both IPV victimization and perpetration (Afifi et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2003). Even more concerning, and similar to other studies, we found a notably higher prevalence of violence during pregnancy was reported by women who had previous experience of violence (68%) (Sarkar, 2008). Previous research has found that women who experience physical violence when they are in a more vulnerable state, such as pregnancy, may be at greatest risk for the most debilitating injuries or death in the future (Morrison et al., 2020; Campbell et al., 2021). Homicide is a leading cause of maternal mortality, the death of a woman during pregnancy or during the first year postpartum (Campbell et al., 2021). One study found a three-fold difference between Black and White women in the rate of maternal homicide, particularly when the victim has a relationship with the perpetrator (Kivisto et al., 2021). Although we didn’t look at homicide in this study, we also found disparities in violence experienced during pregnancy by race/ethnicity with non-Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and mixed or other race women having the highest prevalence of any violence, nearly a two-fold difference compared with White and Asian or Pacific Islander women.

The prevalence of being asked by a prenatal care provider if someone was hurting the respondent emotionally or physically was no different when comparing women who reported violence and those who did not. Another study using PRAMS data also found that while just over half of women reported counseling about IPV during prenatal care, there was no difference by experience of violence (Kapaya et al., 2019). Professional organizations recommend that health care providers screen all pregnant women for violence during health care visits (ACOG, 2012; USPST, 2018), however, based on the findings from this and the previous study, there is room for improvement as many women do not report discussions with their prenatal care provider.

The higher prevalence of violence during pregnancy reported by women who reported an unwanted pregnancy and women who reported violence before pregnancy points to the importance of ensuring access to reproductive health services for women who have experienced or are at increased risk for IPV (Gavin et al., 2017). Similarly, the higher prevalence of reports of violence in certain racial/ethnic subgroups suggests the need to understand structural and system level reasons for differences by race/ethnicity and address root causes of violence (Stockman et al., 2015; Sutton et al., 2020; Waltermaurer et al., 2006). Prevention of IPV perpetration and victimization may be addressed with a comprehensive strategy that includes individual, relationship, and community-level interventions. For example, to prevent victimization and perpetration of IPV before it begins, programs that promote healthy relationships can be provided to adolescents and young adults. Additional prevention strategies include strengthening economic supports for families and early childhood home visitation. Evidence-based interventions and tools are available, although their dissemination and use could be expanded and tailored (CDC, 2017). Referrals to resources and assistance such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline or other state-based hotlines (National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2021), can be made available to women who are identified by their prenatal care providers as at risk or experiencing violence. Screening and referrals by health care providers are an important first step to identifying victims and connecting them with services, however, they may not be sufficient (Chisholm et al., 2017a, b). Community-wide interventions that involve collaboration between crisis centers, law enforcement, health care providers, housing departments, and other services may be effective in helping people get out of dangerous situations, increase safety, and reduce harm.

While this analysis focuses on pregnant women, IPV may begin prior to pregnancy and anyone may experience injury, trauma, and poor health outcomes from IPV. As IPV affects not only women, but also men, children and families, it is important for prevention and intervention efforts to be widely available and accessible to all individuals, including those who may be at increased risk such as individuals from racial/ethnic sub-groups, people with disabilities, and sexual and gender minority individuals.

This study has several limitations. Data are only representative of women from the six states included in the analysis. PRAMS respondents are individuals who had a live birth, so these findings do not represent women who experienced stillbirth, abortion, or miscarriage. Information about experiences during pregnancy is self-reported in the postpartum period and may be subject to recall bias. In the case of a sensitive topic like violence, respondents may choose not to report, or may be more willing to disclose emotional than physical abuse. Further, estimates relate to the woman’s current partner, and do not include ex- or former partners (CDC, 2021). For these reasons, findings likely underestimate the prevalence of IPV experienced during pregnancy.

Conclusion

Intimate partner violence during pregnancy is a serious threat to the health of women, infants, and families. Assessment of emotional, physical and sexual IPV is important in order to get a full picture of this problem and to ensure provision of needed referrals or services. Health care providers can play an important role in screening pregnant women for IPV; however, comprehensive prevention strategies and coordinated community-wide efforts and resources may be needed to prevent IPV before it happens and to ensure that pregnant women receive the services and protection they need.

Acknowledgements

Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Working Group members: Letitia de Graft-Johnson, Arkansas; Lisa Williams, Kansas; Sara E. Thuma, Pennsylvania; Maggie Minett, South Dakota; Linda Lohdefinck, Washington; Fiona Weeks, Wisconsin; PRAMS Team, Women’s Health and Fertility Branch, Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. (2012). 518: Intimate partner violence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 119(2 Pt 1), 412–417. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318249ff74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, Henriksen CA, Asmundson GJ, & Sareen J (2012). Victimization and perpetration of intimate partner violence and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200(8), 684–691. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182613f64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, Rivara FP, Carrell D, & Thompson RS (2009). Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(18), 1692–1697. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Matoff-Stepp S, Velez ML, Cox HH, & Laughon K (2021). Pregnancy-associated deaths from homicide, suicide, and drug overdose: review of research and the intersection with intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(2), 236–244. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdf. Accessed 13 Apr 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences: Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/preventingACES.pdf. Accessed 13 Apr 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html. Accessed 13 Apr 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). PRAMS Selected 2016 through 2019 Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Indicators. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/prams/prams-data/mch-indicators/states/pdf/2019/All-Sites_PRAMS_Prevalence-of-Selected-Indicators_2016-2019_508.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2021.

- Cheng D, Salimi S, Terplan M, & Chisolm MS (2015). Intimate partner violence and maternal cigarette smoking before and during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 125(2), 356–362. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm CA, Bullock L, & Ferguson J 2nd. (2017a). Intimate partner violence and pregnancy: Epidemiology and impact. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(2), 141–144. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm CA, Bullock L, & Ferguson J 2nd. (2017b). Intimate partner violence and pregnancy: Screening and intervention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(2), 145–149. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin L, Pazol K, & Ahrens K (2017). Update: Providing Quality Family Planning Services - Recommendations from CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(50), 1383–1385. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6650a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn CK, Gilmore AK, Aguayo RO, & Rheingold AA (2018). Perinatal intimate partner violence. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 45(3), 535–547. 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L, Pallitto C, García-Moreno C, & Clark CJ (2019). Measuring psychological abuse by intimate partners: Constructing a cross-cultural indicator for the sustainable development goals. SSM - Population Health, 9, 100377. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapaya M, Boulet SL, Warner L, Harrison L, & Fowler D (2019). Intimate partner violence before and during pregnancy, and prenatal counseling among women with a recent live birth, United States, 2009–2015. Journal of Women’s Health, 28(11), 1476–1486. 10.1089/jwh.2018.7545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivisto AJ, Mills S, & Elwood LS (2021). Racial disparities in pregnancy-associated intimate partner homicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 886260521990831. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0886260521990831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Beaumont JL, & Kupper LL (2003). Substance use before and during pregnancy: Links to intimate partner violence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 29(3), 599–617. 10.1081/ada-120023461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison PK, Pallatino C, Fusco RA, Kenkre T, Chang J, & Krans EE (2020). Pregnant Victims of intimate partner homicide in the national violent death reporting system database, 2003–2014: A descriptive analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 886260520943726. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0886260520943726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, & O’Leary KD (1989). Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(5), 579–582. 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Domestic Violence Hotline. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.thehotline.org/. Accessed 13 Apr 2021.

- Normann AK, Bakiewicz A, Kjerulff Madsen F, Khan KS, Rasch V, & Linde DS (2020). Intimate partner violence and breastfeeding: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 10(10), e034153. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD (1999). Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. Violence and Victims, 14(1), 3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JL (2020). Intimate partner violence and perinatal posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms: A systematic review of findings in longitudinal studies. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 1524838020976098. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1524838020976098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salom CL, Williams GM, Najman JM, & Alati R (2015). Substance use and mental health disorders are linked to different forms of intimate partner violence victimisation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 151, 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar NN (2008). The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology : The Journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28(3), 266–271. 10.1080/01443610802042415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman HB, D’Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, & Warner L (2018). The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Overview of design and methodology. American Journal of Public Health, 108(10), 1305–1313. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Hayashi H, & Campbell JC (2015). Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women [corrected]. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(1), 62–79. 10.1089/jwh.2014.4879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs A, & Szoeke C (2021). The effect of intimate partner violence on the physical health and health-related behaviors of women: A systematic review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 1524838020985541. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1524838020985541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton TE, Gordon Simons L, Martin BT, Klopack ET, Gibbons FX, Beach S, & Simons RL (2020). Racial Discrimination as a risk factor for African American men’s physical partner violence: A longitudinal test of mediators and moderators. Violence Against Women, 26(2), 164–190. 10.1177/1077801219830245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Preventive Services Taskforce. (2018). Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: Screening. Retrieved from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/intimate-partner-violence-and-abuse-of-elderly-and-vulnerable-adults-screening. Accessed 13 Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Waltermaurer E, Watson CA, & McNutt LA (2006). Black women’s health: The effect of perceived racism and intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 12(12), 1214–1222. 10.1177/1077801206293545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ER, Donahue E, Sabo RT, Nelson BB, & Krist AH (2021). Barriers to attendance of prenatal and well-child visits. Academic Pediatrics, 21(6), 955–960. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]