In Brief

The authors explored real-world application of a data-driven computer model (Rupture Resemblance Score; RRS) developed to objectively gauge the morphological and hemodynamic similarity of incidentally discovered unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) to ruptured IAs. They explored RRS applicability to cases where the UIA treatment score (UIATS) model recommendation was not definitive. The UIATS recommendation was not definitive for 43% of the UIAs. Using RRS, those could be stratified based on ruptured IA similarity, thus aiding UIA management.

Keywords: intracranial aneurysm, hemodynamics, subarachnoid hemorrhage, machine learning, rupture risk, computational fluid dynamics, vascular disorders

ABBREVIATIONS : CFD = computational fluid dynamics; DSA = digital subtraction angiography; IA = intracranial aneurysm; ICA = internal carotid artery; ISUIA = International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms; MCA = middle cerebral artery; OSI = oscillatory shear index; PComA = posterior communicating artery; PHASES = Population, Hypertension, Age, Size, Earlier SAH, and Site of the Aneurysm; RIA = ruptured IA; RRS = Rupture Resemblance Score; SR = size ratio; UIA = unruptured IA; UIATS = UIA treatment score; WSS = wall shear stress

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Previous studies have found that ruptured intracranial aneurysms (RIAs) have distinct morphological and hemodynamic characteristics, including higher size ratio and oscillatory shear index and lower wall shear stress. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) that possess similar characteristics to RIAs may be at a higher risk of rupture than those UIAs that do not. The authors previously developed the Rupture Resemblance Score (RRS), a data-driven computer model that can objectively gauge the similarity of UIAs to RIAs in terms of morphology and hemodynamics. The authors aimed to explore the clinical utility of RRS in guiding the management of UIAs, especially for challenging cases such as small UIAs.

METHODS

Between September 2018 and June 2019, the authors retrospectively collected consecutive challenging cases of incidentally identified UIAs that were discussed during their weekly multidisciplinary neurovascular conference. From patient 3D digital subtraction angiography, they reconstructed the aneurysm geometry and performed computer-assisted 3D morphology analysis and computational fluid dynamics simulation. They calculated RRS for every UIA case and compared it against the treatment decision made at the neurovascular conference as well as the recommendation based on the unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score (UIATS).

RESULTS

Forty-seven patients with 79 UIAs, 90% of which were < 7 mm in size, were included in this study. The mean RRS (range 0.0–1.0) was 0.24 ± 0.31. At the conferences, treatment was endorsed for 45 of the UIAs (57%). These cases had significantly higher RRSs than the 34 cases suggested for observation (0.33 ± 0.34 vs 0.11 ± 0.19, p < 0.001). The UIATS-based recommendations were “observation” for 24 UIAs (30%), “treatment” for 21 UIAs (27%), and “not definitive” for 34 UIAs (43%). These “not definitive” cases were stratified by RRS based on similarity to RIAs.

CONCLUSIONS

Although not a rupture predictor, RRS is a data-driven model that gauges the similarity of UIAs to RIAs in terms of morphology and hemodynamics. In cases in which the UIATS-based recommendation is not definitive, RRS provides additional stratification to assist the identification of high-risk UIAs. The current study highlights the clinical utility of RRS in a real-world setting as an adjunctive tool for the management of UIAs.

With advancement and accessibility of cranial diagnostic imaging, the number of incidentally discovered unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) has increased.1 UIA treatment decision-making is challenging because there is no high-quality evidence to stratify high-risk UIAs from those that remain stable. Aneurysm size is one of the key factors when discussing treatment options for UIAs, supported by prospective studies that provide a very low 5-year rupture risk to UIAs < 7 mm.2,3 However, small UIAs are prevalent and are responsible for approximately 50% of rupture events.4,5 In addition to size, family history of aneurysms, smoking, and hypertension are believed to increase the risk of aneurysm rupture.2,6,7 The decision-making process becomes further complicated when considering the risks of treatment and associated costs.8 The UIA treatment score (UIATS), derived from consensus among 69 interdisciplinary specialists, is a scoring model to balance the established aneurysm-, patient-, or treatment-related factors and to compare risks associated with conservative management against treatment.9 However, even UIATS can be “not definitive” for some UIAs. For these cases, the interdisciplinary specialists recommended that “additional factors apart from those used in the development of the UIATS may be considered in making a final decision.”9

It is commonly believed that UIAs resembling ruptured IAs (RIAs) are likely to carry a higher rupture risk and therefore warrant early treatment. Previously, we analyzed a cross-sectional cohort of 204 IAs (including 56 RIAs) and generated a logistic regression model based on morphology and hemodynamics.10–12 This model predicts the probability of an IA being a ruptured aneurysm. We then suggested that this logistic regression model could be applied to UIAs and the rupture probability (indicated by ranges between 0 and 1) reinterpreted to gauge their similarity to RIAs.11 In this context, the rupture probability is more appropriately termed the Rupture Resemblance Score (RRS).11 In the present study, we aimed to investigate the clinical utility of RRS as an adjunct in guiding the management of UIAs, especially when existing clinical metrics are inadequate.

Methods

This study was approved by the University at Buffalo institutional review board.

Patient Cohort and Multidisciplinary Neurovascular Conference

Between September 2018 and June 2019, we retrospectively collected data from consecutive UIA cases that were discussed during multidisciplinary neurovascular conferences held at our institution. This conference was held every week to present challenging cerebrovascular cases thought to benefit from discussion and multidisciplinary input. The meeting was attended by neurosurgeons, neurointerventionalists, neurologists, clinical and basic research scientists, nursing staff, international visiting physicians, and observers from other medical institutions, in addition to fellows and medical students. Decisions on treatment or conservative management of aneurysm cases were made by considering the patient’s history; neurological findings; and aneurysm size, morphology, and evidence of growth, without considering RRS or UIATS. A final decision for each case was made based on the consensus at the end of the discussion, documented, and recommended to the patient. The actual management, which could differ from this recommendation, was not considered in the present study.

Rupture Resemblance Score

Previously, we analyzed a cross-sectional data set of 119 consecutively collected IAs (including 38 RIAs)10 and identified morphological and hemodynamic features that were significantly different between RIAs and UIAs. Using multivariate logistic regression, we pared them down to 3 independently significant rupture discriminators—aneurysm size ratio (SR), time- and aneurysm-averaged normalized wall shear stress (WSS), and oscillatory shear index (OSI)—which comprise the rupture discriminator model, odds = exp(0.73SR − 0.45WSS + 2.19OSI − 2.09) (Eq. 1). From the obtained odds, we can calculate the probability (p) of an IA being ruptured: p = odds/(1 + odds). We then tested this model in classifying RIAs from UIAs in an independent cohort of 85 IAs (including 18 RIAs).11 Based on a threshold of p = 0.3, the model was able to identify 90% of RIAs. Furthermore, false-predictive UIAs that were predicted as RIAs bore a high resemblance to RIAs in terms of morphology and hemodynamics. A review of the clinical records showed that these UIAs were treated immediately. Consequently, we applied this rupture discriminator model to new incidentally discovered UIAs, projecting that the obtained probability (a continuous metric ranging between 0 and 1) could be interpreted as the RRS to gauge the similarity of UIAs to RIAs.11 Furthermore, in a follow-up study, we expanded the study cohort to 204 IAs (including 56 RIAs)12 and retrained the rupture discriminator model. The resulting RRS model, odds = exp(0.58SR − 0.33WSS + 2.14OSI − 2.43) (Eq. 2), was almost identical to the original rupture discriminator model, indicating its robustness.12 Details of the computational methodology can be found in our previous studies.10–12

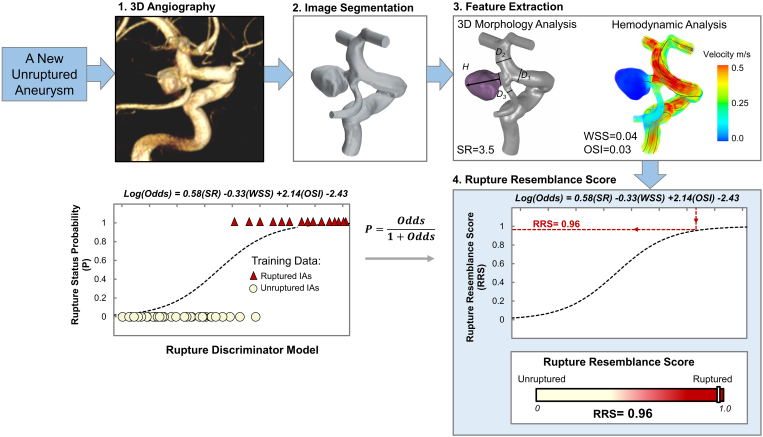

Using the updated RRS model (Eq. 2), we retrospectively calculated RRS for the UIA cases presented at the neurovascular conferences (Fig. 1). First, 3D digital subtraction angiography (DSA) data of a UIA were segmented to reconstruct a surface representation of the aneurysm and parent vessel lumen. Based on the reconstructed 3D geometry, computer-assisted morphology analysis and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation were performed to extract morphological and hemodynamic features, respectively. The input parameters (SR, WSS, and OSI) were then fed into the RRS model. The authors who calculated the RRS were blinded to the decisions made at the neurovascular conferences. Cases in which the image quality was suboptimal for hemodynamic analysis were excluded from our study.

FIG. 1.

Workflow for calculating RRS. 1) 3D angiography; 2) segmentation of images to reconstruct the aneurysm geometry; 3) performing 3D morphology analysis and CFD to extract morphological and hemodynamic features, respectively; and 4) feeding the SR, WSS, and OSI data into the previously developed logistic discriminator model.12 Then, the rupture status probability is reported as RRS. D = vessel diameter; H = height.

Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm Treatment Score

The UIATS is a clinical scoring model developed by 69 multidisciplinary specialists to guide clinical decision-making for the management of UIAs.9 UIATS compares the risk of treatment against conservative management based on 29 aneurysm-, patient-, or treatment-related factors and leads to 2 final scores: “favors UIA repair” and “favors UIA conservative management.” Differences in scores can determine whether a UIA is favorable for treatment or observation. If the difference is 2 points or less, UIATS is considered “not definitive.” The authors who calculated UIATS were blinded to decisions made at neurovascular conferences.

Data Analysis

Using the UIATS, we classified all UIAs into the following 3 cohorts based on differences between “favors UIA repair” and “favors UIA conservative management” scores:

• UIATS < −2 “observation”

• UIATS > +2 “treatment”

• −2 ≤ UIATS ≤ +2 “not definitive”

We also classified all UIAs into observation and treatment cohorts based on treatment decisions recommended at multidisciplinary neurovascular conferences. We report the RRS means and standard deviations for all cohorts. We also report the percentage of UIAs for which the UIATS was “not definitive.” We studied whether the RRS could stratify those UIAs based on their resemblance to RIAs. Additionally, we reported the 5-year rupture risk estimated by the investigators of the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA) and the Population, Hypertension, Age, Size, Earlier SAH (subarachnoid hemorrhage), and Site of the Aneurysm (PHASES) study for the collected cases.2,3 Agreement between the decisions made at the neurovascular conference and the UIATS recommendations was studied using a contingency table, followed by a chi-square test.

Results

Clinical Data

Forty-seven patients with 79 incidentally detected UIAs were included in this study. Table 1 provides a summary of the clinical data. The mean age of the patients was 65 ± 11 years, and 32 patients (68%) were women. Twenty-one patients (45%) had at least 2 UIAs. The mean size of the UIAs was 3.95 ± 2.74 mm, and 90% of them were small (< 7 mm). Location in the internal carotid artery (ICA) had the highest prevalence (37% of all UIAs), and the posterior circulation had the lowest (4% of all UIAs). The corresponding 5-year rupture risks according to ISUIA and PHASES estimates were 1.45% ± 3.56% and 1.05% ± 0.93%, respectively.2,3

TABLE 1.

Summary of cases discussed at weekly multidisciplinary neurovascular conferences

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Patients |

|

| No. of patients |

47 |

| Mean age, yrs |

65 ± 11 |

| Female sex |

32 (68) |

| Hypertension |

24 (51) |

| Smoker |

9 (19) |

| IA family history |

5 (11) |

| IA multiplicity |

21 (45) |

| Aneurysms |

|

| No. of aneurysms |

79 |

| Mean size, mm |

3.95 ± 2.74 |

| Small size (<7 mm) |

71 (90) |

| ACA |

1 (1) |

| AComA |

14 (18) |

| ICA |

29 (37) |

| MCA |

20 (25) |

| PComA |

12 (15) |

| Posterior circulation |

3 (4) |

| 5-yr rupture risk |

|

| ISUIA |

1.45 ± 3.56% |

| PHASES |

1.05 ± 0.93% |

| Mean RRS (range) |

0.24 ± 0.31 (0–1) |

| Neurovascular conference recommendation |

|

| Observation |

34 (43) |

| Treatment |

45 (57) |

| UIATS recommendation |

|

| Observation |

24 (30) |

| Treatment |

21 (27) |

| Not definitive | 34 (43) |

ACA = anterior cerebral artery; AComA = anterior communicating artery.

Values represent the number of patients or aneurysms (%) unless stated otherwise. Mean values are presented as the mean ± SD.

The mean RRS was 0.24 ± 0.31 (range 0.0 to 1.0). The conference participants recommended observation for 34 UIAs (43%) and treatment for 45 UIAs (57%). The UIATS recommendations were “observation” for 24 UIAs (30%), “treatment” for 21 UIAs (27%), and “not definitive” for 34 UIAs (43%).

Comparing RRS With Decisions Made at the Neurovascular Conference and UIATS Recommendations

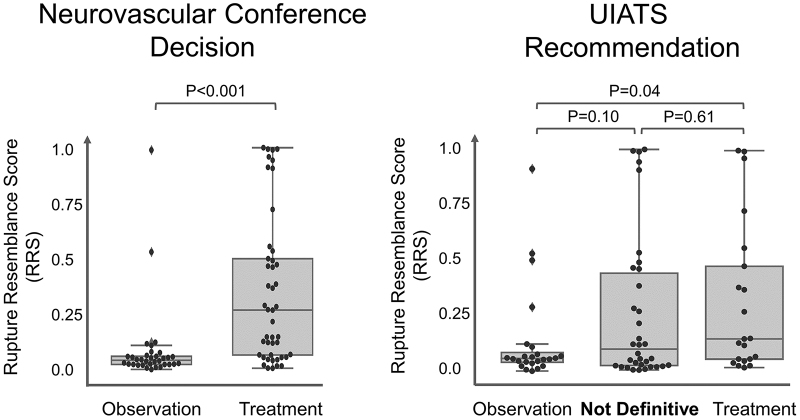

Figure 2 shows RRS plotted against different management recommendations. UIAs that were recommended for treatment at neurovascular conferences had significantly higher RRSs than those recommended for observation. However, the RRS was not significantly different among management cohorts defined based on the UIATS.

FIG. 2.

The RRS for 79 UIAs recommended for observation or treatment based on UIATS and the management based on a consensus of neurovascular conference participants. The UIATS was not definitive for 34 UIAs (43%).

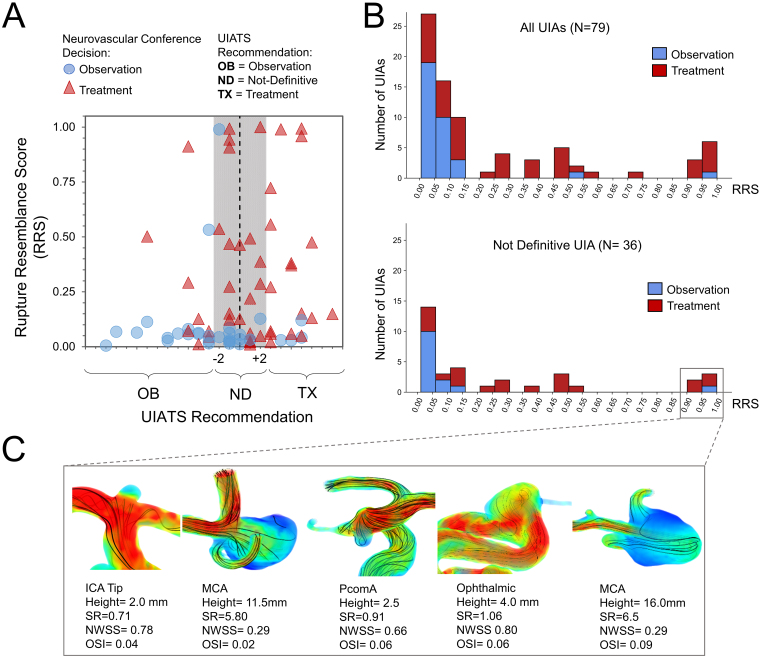

Figure 3A shows a scatterplot of all UIAs with corresponding RRSs against UIATS and neurovascular conference recommendations. There was no correlation between RRS and UIATS-based treatment recommendations. In addition, we found that UIATS was not definitive for 34 UIAs (43%). When comparing RRS with decisions made at the neurovascular conferences, only 2 UIAs with high RRSs were considered for observation: a 4.5-mm irregular ophthalmic artery aneurysm in a patient with metastatic lung cancer and a 2.5-mm posterior communicating artery (PComA) aneurysm recommended for observation due to the UIA size. The remaining UIAs that were recommended for observation had RRSs < 0.15. Figure 3B shows RRS histograms for all UIAs and a subgroup of 34 UIAs that had “not definitive” UIATS recommendations. In both histogram plots, UIAs recommended for treatment at neurovascular conferences had higher RRSs than those recommended for observation.

FIG. 3.

A: Scatterplot of all UIAs with corresponding RRS against UIATS-based recommendations. The UIATS-based recommendation was not definitive for 34 (43%) UIAs (highlighted region). B: Histograms of calculated RRS for all UIAs and for 34 UIAs with “not definitive” UIATS recommendation. RRS stratified those UIAs based on their resemblance to previously ruptured IAs in terms of morphology and hemodynamics. C: Flow visualization of 5 UIAs in panel B (lower) with “not definitive” recommendations from UIATS but having RRS > 0.9. All 5 aneurysms had adverse aneurysm hemodynamic environments, including stasis and oscillatory flow. NWSS = normalized WSS.

The blood flow in 5 UIAs with RRS > 0.9 and “not definitive” recommendations from UIATS is illustrated in Fig. 3C. The 2 large unruptured middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms displayed flow stasis, and the 3 small UIAs (ICA, PComA, and ophthalmic artery) displayed strong impinging flow, which results in oscillatory intraaneurysmal flow. Stasis and oscillatory flow, quantified as low WSS and high OSI, induce aneurysmal wall degradation and destructive remodeling, which can lead to aneurysm rupture.13 Treatment was suggested for all aneurysms except the PComA.

Comparing Decisions Made at the Neurovascular Conference With UIATS Recommendations

The relationship between decisions made at the conference and UIATS recommendations is shown in Table 2. This contingency table indicates that there is an association between the two approaches (chi-square test, p = 0.004), e.g., 81% of cases recommended for treatment by UIATS were suggested to receive treatment by conference participants. In addition, conference participants suggested treatment for 59% of the cases with the “not definitive” recommendation from UIATS. Overall, our results demonstrated that neurovascular conference participants tended to recommend treatment more than the UIATS.

TABLE 2.

Contingency table of UIATS recommendations compared with real-world treatment decisions

| |

No. of Patients (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| UIATS < −2 | −2 ≤ UIATS ≤ +2 | UIATS > +2 | |

| Observation |

16 (67) |

14 (41) |

4 (19) |

| Treatment |

8 (33) |

20 (59) |

17 (81) |

| Total | 24 | 34 | 21 |

Discussion

When discussing treatment options, multiple factors such as aneurysm size, morphology, and location and the patient’s family history, presence of hypertension, age, and life expectancy need to be considered. UIATS is a model developed to quantify and compare factors favoring treatment against factors supporting conservative management to guide treatment decisions. Yet, UIATS had no recommendation for 43% of the challenging UIAs that were discussed at our neurovascular conferences. In such cases, additional factors are required to guide UIA management. RRS is an objective metric that can identify UIAs with a high resemblance to RIAs, based on their detailed morphology and hemodynamics. In this retrospective study, we highlighted the potential application of RRS as an adjunct to UIA management, especially when current clinical metrics cannot provide any recommendation.

Aneurysm rupture is a result of the dynamic and complex interaction between aneurysm morphology, hemodynamics, and aneurysm wall pathophysiology.13 Currently, there is no noninvasive method to measure the vulnerability and strength of the aneurysm wall for patients in routine IA management. However, current cerebrovascular imaging such as DSA, MRA, and CTA and numerical simulation such as CFD can provide bases for aneurysm morphology and hemodynamic analysis. Several studies have found that RIAs have distinct morphology and hemodynamic features.12,14–17 The American Heart Association has also begun to recognize the importance of these factors, suggesting that one “consider morphological and hemodynamic characteristics of the aneurysm when discussing the risk of aneurysm rupture.”18 To that end, RRS offers a practical means, linking the morphology and hemodynamics of a UIA to known rupture characteristics.

Although RRS does not directly predict aneurysm rupture, it gauges the similarity of UIAs to RIAs. The development of a true rupture predictor requires longitudinal follow-up of unbiased cohorts of UIAs for a sufficiently long time, which is extremely difficult to accomplish because most UIAs eventually receive treatment.19 Conversely, RRS is derived from consecutively collected cross-sectional data and therefore is unbiased. In current clinical practice, UIAs with an irregular or elongated shape and blebs, which are common features of RIAs, are usually recommended for treatment, regardless of size.20 RRS quantifies such morphology and also incorporates aneurysmal hemodynamics; therefore, it is more objective and accurate. Having such a tool can be greatly informative in the process of decision-making, especially for challenging UIAs.21

We would like to emphasize that the RRS concept is important because it shifts the paradigm from predicting rupture risk, which is difficult to establish, to quantifying rupture resemblance. However, the formulation of RRS is not unique. It can be expanded and improved over time. Currently, RRS evaluation is based purely on IA morphology and hemodynamics. Nonanatomical risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and family history are currently not incorporated in the RRS. In practice, decision-making is based on several aneurysm-, patient-, and treatment-related factors but not hemodynamics. This is probably the main reason for the observed discrepancies between RRS evaluation and management suggested by the conference participants or UIATS. However, RRS is a concept that can be expanded beyond morphology and hemodynamics to incorporate aneurysm location and nonanatomical risk factors. We have recently demonstrated that incorporating clinical factors can improve the performance of RRS.17 In the current study, we used our original model, which proved to be stable and robust in two follow-up studies.11,12 By incorporating larger cohorts from different populations, RRS can become increasingly more robust. With a sufficiently large repository of training data, RRS can further be tailored for aneurysm locations or patients in the future.

Other research groups that have made great strides in building rupture classification models22,23 could also consider adopting the RRS concept, which is simply a reinterpretation of the probability of rupture status in the classification models. Rupture status classification itself has no clinical utility but changing the focus of the classification models to measure the similarity of UIAs to RIAs could have a greater impact on IA management.

It should be cautioned that to directly use our RRS formula, it is best to perform CFD and morphological analysis in the same manner as described in our studies, to be consistent with the training data set used for building the models. Otherwise, the results may be less reliable.24 To overcome this limitation, we believe it is essential that methodologies and parameter definitions be standardized; the lack of standardization is a significant hurdle to the development and dissemination of data-driven models.

In the future, it will be possible to test the effectiveness of RRS at identifying unstable UIAs in longitudinal data sets. We have not performed such studies. However, preliminary evidence of a possible correlation between RRS and UIA growth has been reported.25 Furthermore, correlation between RRS, wall phenotype,26 and wall enhancement27 could be investigated to shed new light on aneurysm pathology and rupture characteristics.

Limitations

This is a proof-of-concept study with a small number of patients at a single center. Therefore, performance of the RRS needs to be tested on larger data sets at other institutions. Furthermore, we only included challenging IA cases that were presented at the multidisciplinary neurovascular conference; thus, it is unclear whether the results hold true for all aneurysm patients. Our RRS model was generated on a small data set of 204 IAs at a single center. Also, the input features, particularly the hemodynamic parameters, were derived from CFD simulations that had a set of nonphysiological assumptions, including rigid wall and Newtonian fluid. Finally, the RRS model was built using retrospectively collected cross-sectional data and could be tested in a longitudinal study to evaluate its ability in identifying UIAs that will rupture.

Conclusions

Although not a rupture predictor, RRS is a data-driven model that gauges the similarity of UIAs to previously ruptured IAs in terms of morphology and hemodynamics. In those cases for which current clinical metrics cannot provide a definitive treatment recommendation, RRS adds additional stratification to aid the identification of high-risk UIAs. The current study highlights the clinical utility of RRS in a real-world setting as an adjunctive tool for informed decision-making for the management of UIAs.

A) We explored the real-world application of a data-driven computer model (RRS) developed to objectively gauge the similarity of incidentally discovered UIAs to a ruptured cohort of IAs in terms of morphology and hemodynamics.

B) We explored the applicability of RRS in cases in which the recommendation of the UIATS model was not definitive.

C) We found good agreement between RRS and decisions made at our multidisciplinary neurovascular conferences. The UIATS recommendation was not definitive for 43% of the UIAs. By applying the RRS model, those cases could be stratified based on their similarity to RIAs, thus aiding in the management of UIAs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants R01NS091075 and R03NS090193; and JMD National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR001413 to the University at Buffalo.

We thank Paul H. Dressel, BA, for assistance with preparation of the illustrations and W. Fawn Dorr, BA, and Debra J. Zimmer for editorial assistance.

Disclosures

Funding was provided by Canon Medical Systems Corp.

Dr. Snyder: consulting and teaching for Canon Medical Systems Corp., Penumbra Inc., Medtronic, and Jacobs Institute; and cofounder of Neurovascular Diagnostics, Inc. Dr. Davies: shareholder/ownership interests in RIST Neurovascular; ownership in Cerebrotech; consultant for Medtronic; speakers bureau for Penumbra; and honoraria from Neurotrauma Science, LLC. Dr. Siddiqui: research grant as coinvestigator of NIH/NINDS R01NS091075; financial interest/investor/stock options/ownership in Amnis Therapeutics, Apama Medical, Blink TBI Inc., Buffalo Technology Partners Inc., Cardinal Consultants, Cerebrotech Medical Systems, Inc., Cognition Medical, Endostream Medical Ltd., Imperative Care, International Medical Distribution Partners, Neurovascular Diagnostics Inc., Q’Apel Medical Inc., Rebound Therapeutics Corp., Rist Neurovascular Inc., Serenity Medical Inc., Silk Road Medical, StimMed, Synchron, Three Rivers Medical Inc., and Viseon Spine Inc.; consultant/advisory board for Amnis Therapeutics, Boston Scientific, Canon Medical Systems USA Inc., Cerebrotech Medical Systems Inc., Cerenovus, Corindus Inc., Endostream Medical Ltd., Guidepoint Global Consulting, Imperative Care, Integra LifeSciences Corp., Medtronic, MicroVention, Northwest University–DSMB Chair for HEAT Trial, Penumbra, Q’Apel Medical Inc., Rapid Medical, Rebound Therapeutics Corp., Serenity Medical Inc., Silk Road Medical, StimMed, Stryker, Three Rivers Medical, VasSol, W.L. Gore & Associates; and principal investigator/steering committee of the following trials: Cerenovus NAPA and ARISE II; Medtronic SWIFT PRIME and SWIFT DIRECT; MicroVention FRED & CONFIDENCE; MUSC POSITIVE; and Penumbra 3D Separator, COMPASS, and INVEST. Dr. Levy: shareholder/ownership interests in NeXtGen Biologics, RAPID Medical, Claret Medical, Cognition Medical, Imperative Care (formerly the Stroke Project), Rebound Therapeutics, StimMed, and Three Rivers Medical; national principal investigator/steering committees of Medtronic (merged with Covidien Neurovascular) SWIFT PRIME and SWIFT DIRECT Trials; honoraria from Medtronic (training and lectures); consultant for Claret Medical, GLG Consulting, Guidepoint Global, Imperative Care, Medtronic, Rebound Therapeutics, and StimMed; advisory board of Stryker (AIS Clinical Advisory Board), NeXtGen Biologics, MEDX, Cognition Medical, and Endostream Medical; site principal investigator of CONFIDENCE study (MicroVention), STRATIS Study—Sub I (Medtronic); and provider of medical/legal opinion as an expert witness. Dr. Meng: principal investigator of NIH grants R01NS091075 and R03NS090193 and Canon Medical Systems Corp. grants (no grant number); and cofounder of Neurovascular Diagnostics Inc.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Meng, Rajabzadeh-Oghaz, Waqas. Acquisition of data: all authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: Meng, Rajabzadeh-Oghaz, Waqas. Drafting the article: Meng, Rajabzadeh-Oghaz, Waqas. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: all authors.

Supplemental Information

Previous Presentations

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the following meetings: the 16th Interdisciplinary Cerebrovascular Symposium, Iowa City, IA, April 17, 2019; and the 81st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurological Surgery, Rome, Italy, September 18–21, 2019.

References

- 1. Etminan N, Rinkel GJ. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: development, rupture and preventive management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(12):699–713. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bijlenga P, Gondar R, Schilling S, et al. PHASES score for the management of intracranial aneurysm: a cross-sectional population-based retrospective study. Stroke. 2017;48(8):2105–2112. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, III, et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng J, Xu R, Guo Z, Sun X. Small ruptured intracranial aneurysms: the risk of massive bleeding and rebleeding. Neurol Res. 2019;41(4):312–318. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2018.1563737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee G-J, Eom K-S, Lee C, et al. Rupture of very small intracranial aneurysms: incidence and clinical characteristics. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2015;17(3):217–222. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2015.17.3.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korja M, Kivisaari R, Rezai Jahromi B, Lehto H. Natural history of ruptured but untreated intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2017;48(4):1081–1084. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Can A, Castro VM, Ozdemir YH, et al. Association of intracranial aneurysm rupture with smoking duration, intensity, and cessation. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1408–1415. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hackenberg KAM, Hänggi D, Etminan N. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2018;49(9):2268–2275. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Etminan N, Brown RD, Jr, Beseoglu K, et al. The unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score: a multidisciplinary consensus. Neurology. 2015;85(10):881–889. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiang J, Natarajan SK, Tremmel M, et al. Hemodynamic-morphologic discriminants for intracranial aneurysm rupture. Stroke. 2011;42(1):144–152. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xiang J, Yu J, Choi H, et al. Rupture Resemblance Score (RRS): toward risk stratification of unruptured intracranial aneurysms using hemodynamic-morphological discriminants. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7(7):490–495. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiang J, Yu J, Snyder KV, et al. Hemodynamic-morphological discriminant models for intracranial aneurysm rupture remain stable with increasing sample size. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8(1):104–110. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, Siddiqui A. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35(7):1254–1262. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung BJ, Mut F, Putman CM, et al. Identification of hostile hemodynamics and geometries of cerebral aneurysms: a case-control study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(10):1860–1866. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Backes D, Vergouwen MD, Velthuis BK, et al. Difference in aneurysm characteristics between ruptured and unruptured aneurysms in patients with multiple intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1299–1303. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miura Y, Ishida F, Umeda Y, et al. Low wall shear stress is independently associated with the rupture status of middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke. 2013;44(2):519–521. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.675306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varble N, Tutino VM, Yu J, et al. Shared and distinct rupture discriminants of small and large intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2018;49(4):856–864. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Connolly ES, Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43(6):1711–1737. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alshafai N, Falenchuk O, Cusimano MD. Practises and controversies in the management of asymptomatic aneurysms: results of an international survey. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29(6):758–764. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1096906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindgren AE, Koivisto T, Björkman J, et al. Irregular shape of intracranial aneurysm indicates rupture risk irrespective of size in a population-based cohort. Stroke. 2016;47(5):1219–1226. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xiang J, Antiga L, Varble N, et al. AView: an image-based clinical computational tool for intracranial aneurysm flow visualization and clinical management. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44(4):1085–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1363-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Detmer FJ, Chung BJ, Mut F, et al. Development and internal validation of an aneurysm rupture probability model based on patient characteristics and aneurysm location, morphology, and hemodynamics. Int J CARS. 2018;13(11):1767–1779. doi: 10.1007/s11548-018-1837-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Y, Tian Z, Jing L, et al. Bifurcation type and larger low shear area are associated with rupture status of very small intracranial aneurysms. Front Neurol. 2016;7:169. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kallmes DF. Point: CFD—computational fluid dynamics or confounding factor dissemination. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(3):395–396. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Varble N, Kono K, Rajabzadeh-Oghaz H, Meng H. Rupture resemblance models may correlate to growth rates of intracranial aneurysms: preliminary results. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:e794–e805. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.11.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cebral J, Ollikainen E, Chung BJ, et al. Flow conditions in the intracranial aneurysm lumen are associated with inflammation and degenerative changes of the aneurysm wall. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(1):119–126. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hu P, Yang Q, Wang D-D, et al. Wall enhancement on high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging may predict an unsteady state of an intracranial saccular aneurysm. Neuroradiology. 2016;58(10):979–985. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]