Abstract

Adolescence and the transition to adulthood is an important developmental stage in the emergence of health risk behaviors, specifically underage alcohol use. Adolescents consume a tremendous amount of screened media (primarily streamed television), and media depictions of behaviors is prospectively linked to youth initiation of behaviors. With the arrival of streamed media technology, alcohol advertising can be nested within television content. This study describes alcohol brand depictions in television and evaluates impact of exposure to such depictions on adolescent drinking outcomes. A national sample of 2012 adolescents (Mage = 17.07; SD = 1.60 years, range 15–20; 50.70% female) reported on television viewership, alcohol brand affiliation, and drinking behavior, with follow-up one year later. Ten series (that remain relevant to youth today) across television ratings from a single television season were content coded for presence/salience of alcohol brand appearances. Adjusting for covariates (e.g., peer/parent drinking, youth sensation seeking, movie alcohol brand exposure), higher exposure to brand appearances in the television shows was associated with youth drinking. Aspirational and usual brand to drink corresponded to television alcohol brand prominence, and television brand exposure was independently associated with drinking initiation and hazardous drinking.

Keywords: Alcohol product placement, Underage drinking, Television alcohol exposure

Introduction

Adolescence is a period in youth development with emphasis on the emergence of autonomy and independence; with this shift comes an increased risk for engagement in health risk behaviors, such as substance use. Underage alcohol use is a significant public health concern, with alcohol remaining the leading substance used and abused by youth (Kann et al., 2018). Alcohol initiation during late adolescence (i.e., 18 years and older) is somewhat normative, with almost 60% of 12th graders reporting any lifetime alcohol use (Johnston et al., 2020). Prevalence of alcohol initiation and progression of use escalates rapidly across age cohorts during adolescent development phases as well, as only around 23% of 8th graders report lifetime alcohol use (Johnston et al., 2020). Beyond the immediate health concerns related to adolescent alcohol use in the context of a developing brain, early onset alcohol use and binge drinking that occurs during adolescence is associated with negative outcomes, such as problem drinking/dependence later in life (Guttmannova et al., 2012). Given the high-risk phase of adolescence and the potential detrimental effects of early-onset alcohol use, prior research has centered on modifiable environmental risk factors impactful for underage drinking, such as the role of media and exposure to advertising.

Youth today have unprecedented access to personalized media devices, with 95% of teens report ownership or access to smartphones and teen access to personalized media devices increasing with age (Anderson & Jiang 2018). With the ubiquity of media access, youth are bombarded with depictions of alcohol use and alcohol marketing across a range of media sources. Television remains the most prominent screened media content consumed by adolescents, but due to recent shifts in technology youth primarily stream television and video content rather than viewing aired television content live (Rideout & Robb 2019). The combination of increased youth access to media and technology with increased alcohol depictions embedded in media may have consequences for youth drinking outcomes. The present study seeks to extend current knowledge of the link between youth exposure to alcohol content in media and youth alcohol use behavior through examination of branded alcohol content nested within television show content as it relates to underage drinking outcomes.

Alcohol Depictions in Media and Alcohol Brand-Specific Effects

Numerous studies including four systematic reviews have identified the influence of alcohol media and marketing exposures on adolescent initiation of alcohol use, as well as problem drinking and drinking-related consequences (Anderson et al., 2009; Jernigan et al., 2017; Koordeman et al., 2012; Smith & Foxcroft 2009). These positive associations have been replicated across study designs, populations and types of media, and there is strong consensus that media depictions of alcohol use are related to alcohol consumption in youth. Three reviews investigated longitudinal studies on the influence of alcohol marketing on adolescents across platforms, including traditional advertising, movies, television, radio, and outdoor advertising, finding media depictions of alcohol to be significantly associated with drinking initiation in never-drinkers and progression in baseline drinkers (Anderson et al., 2009, Jernigan et al., 2017; Smith & Foxcroft 2009). A fourth review focused specifically on alcohol depictions in movies, music videos and soap operas, finding that alcohol exposure, while important for youth drinking outcomes, may have differential effects on adolescents dependent upon associated factors such as age, peer/parent alcohol use, sensation seeking, and gender (Koordeman et al., 2012). Across these reviews, the primary source of media content analyzed has been movies, given the relative ease by which movies can be categorized, content coded, and assessed for viewership through youth report. Movies only represent one small (although meaningful) aspect of youth media content exposure, however, and therefore will be considered as a covariate in the present study.

Movie content coding can also serve as a representation of overarching media trends as well. For example, alcohol content in the media may be increasing, as a review of content coding literature across ten years revealed an increase in the number of alcohol brand appearances in youth rated movies across time (Bergamini et al., 2013). Similar trends may occur in televised media as well as media depictions of alcohol are common in television content. For example, in a content analysis of television shows popular with youth, over 70% of episodes in shows rated TV-PG or higher contained content related to alcohol (Gabrielli et al., 2016). In the 2017 Super Bowl alone, which ran for approximately 4 h and was viewed by an estimated 111.3 million people (many of whom were children), 13 alcohol advertisements were featured (MacLean et al., 2017; Nielsen 2017).

An important limitation of prior research is the lack of emphasis on brand-specific effects (Roberts et al., 2016). Many studies either use aggregate data on alcohol sales and consumption or group drinking behavior based on type of beverage rather than specific brand (e.g. “beer” rather than “Budweiser”). This, in turn, has the potential to obscure the true effects of alcohol advertisements on drinking behavior (Roberts et al., 2016). The literature on tobacco advertising and subsequent smoking behavior underscore the value of looking at brand-specific outcomes: by looking at the effects of specific brands’ advertising campaigns–such as Camel brands’ Joe the Camel campaign, whose inclusion of a camel cartoon was very appealing to children–on youth consumption, researchers were able to identify a strong connection between brand advertising and initiation of consumption of that specific brand (Roberts et al., 2016). Recent studies that have looked at specific alcohol brand exposure and subsequent consumption yielded similar results; research suggests that youth prefer alcohol brands that have large advertising expenditures (Tanski et al., 2011) and youth are approximately five times more likely to consume alcohol brands that are advertised on national television (Siegel et al., 2016).

The Influence of Television

Just as it is important to differentiate brand-specific effects, so too is it important to evaluate media modality and alcohol depiction types separately given their inherent differences. For example, it is reasonable to expect that traditional alcohol advertisements (e.g., a beer commercial during a football game) will influence adolescents differently than unbranded alcohol depictions in a show or movie (e.g., the main character of a popular television show drinking an unbranded beer at a party), and further that the increasingly common hybrid of the two–product placement–will exert its own unique, and perhaps synergistic, influence (Koordeman et al., 2012). The aforementioned studies either reference product placement under the more general umbrella term of “media depictions” or in the context of distinct forms of media (e.g., movies, music, radio), but few studies to date have examined the influence of product placement in television shows. This is partly due to the relative ease with which other modalities, particularly movies, can be assessed for content and individual exposure. Television, on the other hand, is not as easily coded; television programming is consumed over multiple episodes and oftentimes across seasons rather than in one sitting, as movies tend to be viewed. To put this in perspective, the Sex in the City movie was 2 h and 25 min of content, while the television series spanned 94 episodes over 6 seasons. Due to this challenge, studies that assess embedded television alcohol branded content/advertising and adolescent exposure are lacking, despite the fact that television show content (whether viewed on a traditional television set or streamed via mobile devices) remains the primary source of media consumption for adolescents (Rideout and Robb 2019; Rideout 2016).

The increasing accessibility of media content through instant streaming and personalized media devices has extended television’s reach even farther into the lives of youth; a Pew Survey on teens and technology indicates that the vast majority of teens own or have access to a smart phone (95%) or a laptop or desktop computer (88%) and consume television/videos for almost 3 h a day (Anderson & Jiang 2018). Compared to 2015, when 48% of teens’ total television viewing happened live on a television set, only 24% of 2019 total viewership was live, shifting predominately to streaming services like Netflix and YouTube (Rideout & Robb 2019). Streaming has gained in popularity due to its “on-demand” nature, convenience, cost, original content (e.g. Amazon Originals or Netflix), and, most notably for the purpose of this paper, the elimination–or significant reduction–of commercials. This trend indicates that product placement within series will likely become a more dominant marketing approach of the alcohol industry due to limits of traditional commercial advertising in streaming content.

It is important to note that, with the shift from cable and broadcast television to streaming services, viewers’ have access to both current and past shows. In fact, Netflix released a list of its most-viewed television shows from 2017–2018, which is topped by the Office, which was on air from 2005 to 2013, and Friends, which was on air from 1994 to 2004 (Flint & Sharma 2019). Netflix’s viewing statistics highlight that, in the current viewing climate, a show’s original air date is not a major factor in its popularity. Indeed, despite the fact that the shows in this study originally aired in the mid-2000s, they all remain available to stream on multiple platforms, meaning that they are still popular among viewers. Further, if trends in movie alcohol placements are any indication (Bergamini et al., 2013), alcohol product placements on television have likely only increased since the production of these shows. Thus, the results presented within this study likely underestimate the true amount of alcohol product placements youth are exposed to today.

Product Placement

Despite the notable shift in television viewing habits with the emergence of streamed media, little is known about the scope and nature of alcohol brand placement within television series. Defined as “a paid product message aimed at influencing movie (or television) audiences via the planned and unobtrusive entry of a branded product into a movie (or television program)” (Balasubramanian 1994), product placements may be more influential than overtly persuasive marketing approaches such as commercial advertisements. This is, in part, because it may not be perceived as advertisement (Russell & Russell 2009; Shrum 2012). When viewers recognize an attempt at persuasion, a cognitive process ensues whereby the individual integrates knowledge about the topic, persuading agent, and act of persuasion in general in order to interpret and respond to the attempt (Friestad & Wright 1994). This active thought process increases the likelihood of resisting the message (Auty & Lewis 2004). Product placements circumvent cognitive defenses by exerting influence without being recognized as a persuasion attempt (Auty & Lewis 2004; Balasubramanian 1994), consequently decreasing viewers’ ability to resist the message (Auty & Lewis 2004). This has alarming implications for the influence alcohol product placements might have on subsequent adolescent drinking behavior.

Theoretical Framework for General Media Effects

Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1986) has been put forth as a theoretical framework to explain the translation of media exposure to alcohol to subsequent alcohol consumption, positing that adolescents learn both from direct experience and observation. This theory has most commonly been used to describe the role of parents or peers (known influencers for youth alcohol initiation and progression) in shaping youth behavior. As it applies to alcohol depictions in the media, this theory holds that by observing alcohol use behavior on television, in movies, or through music, youth alcohol use behavior is subsequently affected. An experimental study provided support for this theory by measuring the acute effects of media alcohol exposure on drinking behavior; researchers found that when comparing the immediate alcohol consumption of young men watching a movie depicting alcohol use to a control group watching a movie with no alcohol use, those in the test group drank significantly more, presumably as a result of watching the actors drink (Koordeman et al., 2014). The immediate modeling behavior of these young test subjects may bear similarity to the behavior of teens in the long and short term after media exposure to alcohol. Indeed, researchers have put forth the idea of media as a “super peer,” whereby media exerts influence in a similar, but more powerful, way as an individual’s peers (e.g., Elmore et al., 2017; Strasburger 2007). It follows, then, that just as perceiving alcohol use among peers predicts alcohol use, so too would alcohol use in the media predict alcohol use (Dal Cin et al., 2009). This social learning occurs despite mass media being much more likely to depict positive drinking experiences than negative, where characters’ drinking is often reinforced (Dal Cin et al., 2009).

Theoretical Framework for Marketing Effects

Product placement occupies a niche between entertainment media and traditional advertising, warranting theoretical grounding from both social learning as well as marketing perspectives. Accordingly, a heuristic-systematic model of marketing receptivity likely applies (Morgenstern et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2014). Originally operationalized for tobacco and adapted for alcohol, marketing receptivity can be defined as “a willingness to be open and responsive to the sponsor’s ideas, impressions, and suggestions” (Henriksen et al., 2008), with moderate receptivity being characterized as having a favorite advertisement, and high receptivity as owning or being willing to use branded merchandise, reflecting a positive affect towards substance-related advertising and related promotional content (McClure et al., 2013).

Alcohol receptivity was adapted from the same model as tobacco, partially because of the similarity between alcohol and tobacco marketing strategies and brand goals: increasing product use among never-users (Henriksen et al., 2008). Within this developmental cascades model, adolescents are exposed to alcohol content and/or marketing, which influences their alcohol expectancies and attention to marketing, relates to marketing preferences, brand recognition and affiliation, and consequently influences their identity as a drinker and drinking behaviors (McClure et al., 2013). This work has not extended to understanding how exposure to embedded marking content (i.e. product placement) may relate to formation of youth attitudes towards brands as well as subsequent risk for underage drinking initiation and progression. That being said, as a combination of media content and marketing, one might expect product placement to exert a more powerful influence (e.g., through consumer emotional connection with the product; Koordeman et al., 2012) on adolescent drinking behavior than either general media depictions of alcohol use or traditional marketing attempts might have otherwise exerted (Hudson & Hudson 2006); seeing a favorite television character drink alcohol might influence general alcohol expectancies, but seeing a favorite television character drinking branded alcohol might both influence general alcohol expectancies and specific brand receptivity.

Current Study

The present study endeavors to address gaps in the literature by exploring the prevalence and impacts of alcohol product placement within television programming. Alcohol content and brand appearances within ten complete television series from the 2009/2010 season were described, and associations between adolescent self-reported exposure to these programs and youth reported brand affiliation, current drinking status, and subsequent drinking transitions were evaluated. It is well recognized that this is a very limited measurement of alcohol media content exposure; however, similar to previous studies that content coded movies, this study seeks to provide an estimate of television exposure to alcohol brand content. Given prior evidence for the link between drinking depictions in movies and adolescent drinking (Dal Cin et al., 2008), movie alcohol brand exposure was identified as a key covariate. Further, it was posited that the exposure effect on adolescent drinking would be independent of other media-related factors such as amount of television viewed generally, as well as more general factors associated with youth drinking outcomes such as sensation seeking (Sargent et al., 2010), parent and friend alcohol use, age and gender (Gabrielli et al., 2019; Jernigan et al., 2017). Prior literature has focused primarily on count or yes/no presence of alcohol content; the present study extends this literature with content coding of brand salience. It was hypothesized that alcohol brands with more frequent and salient television series appearances would be more popular with adolescents, and greater exposure to alcohol brands across television series would be independently associated with adolescent drinking outcomes. For the purposes of this paper, “television” will be used to describe traditional broadcast television, cable and internet series programming viewed through either traditional television set devices, streamed on personalized digital devices (such as smartphones or tablets), or streamed via computer.

Methods

Data Collection and Participants

This is a secondary data analysis with a sample recruited for a study aiming to evaluate the impact of alcohol advertising on youth drinking behavior. Between October, 2010 and June, 2011, 3342 adolescents and young adults aged 15–23 years were recruited to complete random-digit dial computer-assisted telephone interviews with a follow up online survey. Participants received $10 for completion of the phone survey, with an additional $10 provided for completion of the supplemental online survey. The survey had completion rates of 56.3 and 43.8% for landlines and cell phone samples respectively. Of subjects who completed the baseline survey, 1596 (61.7%) completed the follow-up one year later. The follow-up sample had higher retention rates for younger participants and those from families with greater household income. For this study, the sample was limited to 2012 underage (<21 years of age) adolescents aged 15–20 years (sample mean age = 17.07; SD = 1.60 years). Participants over age 18 provided verbal consent. Subjects under age 18 provided verbal assent and verbal parental permission was obtained. Individuals responded to sensitive questions via their telephone keypad. The Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects at [name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process] approved the study. Further documentation of survey methodology has been previously published (Tanski et al., 2015).

Media and Advertising Exposure Content Coding

Ten scripted television/cable series from the 2009/10 distribution season that had been met with acclaim (based on viewership and popularity) in the preceding season were content coded for alcohol depictions. Series were selected to represent a range of rating categories (TV-PG, TV-14, TV-MA) as defined by the Television Parental Guidelines (2019). Series were purposively sampled to include popular series containing some mature content to ensure adequate variability in brand appearances. “Reality television” was excluded, as content and product placement would be less likely to be predetermined in this type of programming. Using rigorous and validated methods that have been employed at [name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process] for movie content coding, two highly experienced media coders digitally screened all episodes (92 h, 156 episodes) from the selected season and series. All occurrences of alcohol brands were coded, defined as any brand identifiable by logo or name either visually depicted or mentioned, regardless of whether it was consumed. For each brand appearance identified, coders also assigned a salience score representing how notable the brand appearance was within the series (see below for salience description). Reliability of television content across coders was obtained by double-coding alcohol brand appearances in a random sample of 10% of episodes, which provided an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.74, considered an acceptable level (Cicchetti 1994).

Measures

Alcohol use Measures

Alcohol use outcomes included questions about any drinking and hazardous drinking. Any drinking was obtained by asking respondents “Have you ever had a whole drink of alcohol more than a sip or taste?” [yes/no]. Hazardous drinking status was determined using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test- Consumption (AUDIT-C) as defined by Dawson et al., (2005), which assesses binge drinking (assessed by asking “How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion?” [Never/Less than monthly/Monthly/Weekly/Daily or almost Daily]); drinking frequency (“In the past year, how often did you have a drink of alcohol” Once a month or less, 2–4 times a month, 2–3 times a week, or 4 or more times a week) and quantity of alcohol consumed (“How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?” 1 or 2; 3 or 4; 5 or 6; 7, 8, or 9; or 10 or more) (Bush et al., 1998; Dawson et al., 2005). The six-drink threshold for binge drinking is higher and more conservative than is customary in US surveys (based on grams of alcohol per drink) (Babor et al., 2001). A score of 4 or greater on the AUDIT is defined as hazardous drinking among adults, thus is a highly conservative estimate among adolescents.

Alcohol Brand Affiliation

Brand affiliation was indicated by adolescent self-reported aspirational brand and usual brand to drink. Adolescents’ aspirational brand was assessed by: “If you could drink any brand you want, what is the name of the brand of alcohol you would choose?” Usual brand was assessed by: “What is the usual brand that you drink?” Reported brands were recorded using a single-choice drop-down menu of over 120 top alcohol brands including an “other” category.

Adolescent Alcohol Brand Television Exposure

Adolescents were asked how frequently they watched each of the ten content coded series with responses on a five-point Likert scale from “no episodes” to “every episode”. An exposure score was created by combining frequency of watching each series with frequency of alcohol brands appearances in each series (as determined below). Scores could fall on a continuous range due to the variability in brand depictions present across series and the variability in viewership across series. Exposure scores ranged from 0 (no exposure) to 141 (high exposure) with a positively skewed distribution. For interpretability and to address the issue of skewness, the exposure score was categorized into a three-category ordinal measure of “none,” “moderate” (0.1 – 21), and “high” (22 – 141) exposure based on the distribution of scores.

Subject Covariates

Covariates also included age, gender, and race as well as six items assessing sensation-seeking tendencies (e.g. “I like to do frightening things”[α = 0.72]) (Sargent et al., 2010), peer drinking (“How many of your friends drink alcohol?” [None to Most]), and parental drinking (“Which of the following statements best describes how often your mother/father drinks alcohol?” [Never-Occasionally to Weekly-Daily]). Adolescents were also asked about the frequency of television viewing/media use, “On week days, how many hours a day do you usually watch television programs or movies either on TV or over the internet?” [None to Over 4 h], and top box office movie viewing.

Alcohol Brand Content: Appearance Count Across Series and Salience

To account for the fact that some brands appeared many times across series while other brands appeared in only one series, a sum score was calculated for the number of series that contained any appearance for a given brand to identify series count (range 1–10, e.g., Bacardi appeared in Californication, Mad Men, and True Blood for a score of “3”). Brand appearances were also rated on salience, which was averaged to estimate how notable appearances were for each brand (values were “1, a brand was suggested but uncertain”; “2, a brand unmistakable but logo or name not seen”; “3, a brand logo or name was clearly visible or mentioned by a character with drinking depicted”). A combined television brand prominence score for each alcohol brand was created to account for series count of brand appearances and salience of brand depiction (mean salience score X series count; Table 2).

Table 2.

Top 20 alcohol brands depicted in the selection of television shows

| Brand | Youth Ranking |

# of Brand Appearances |

% of Total Brands |

# of Series Appeared (Count) |

Mean Salience of Brand Appearance |

Salience × Series Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Budweisera | 1 | 41 | 11.9% | 6 | 2.39 | 14.34 |

| 2 Heinekena | 11 | 22 | 6.3% | 4 | 1.96 | 7.84 |

| 3 Dos Equisa | 16 | 19 | 5.5% | 1 | 2.74 | 2.74 |

| 4 Abita | >20th | 17 | 4.9% | 1 | 2.65 | 2.65 |

| 5 Bombay | >20th | 17 | 4.9% | 3 | 1.47 | 4.41 |

| 6 Millera | 9 | 9 | 2.6% | 3 | 2.78 | 8.34 |

| 7 Sol | >20th | 9 | 2.6% | 2 | 2.33 | 4.66 |

| 8 Johnny Walker | >20th | 9 | 2.6% | 4 | 1.33 | 5.32 |

| 9 Stolichnaya | >20th | 9 | 2.6% | 5 | 1.78 | 8.90 |

| 10 Bacardia | 5 | 8 | 2.3% | 3 | 2.00 | 6.00 |

| 11 Patron Tequilaa | 15 | 8 | 2.3% | 3 | 2.00 | 6.00 |

| 12 Cuervo | >20th | 8 | 2.3% | 2 | 2.25 | 4.50 |

| 13 Captain Morgana |

8 | 7 | 2.0% | 2 | 2.57 | 5.14 |

| 14 Coronaa | 3 | 7 | 2.0% | 4 | 2.71 | 10.84 |

| 15 Dixie | >20th | 7 | 2.0% | 1 | 2.86 | 2.86 |

| 16 Absoluta | 14 | 7 | 2.0% | 3 | 2.14 | 6.42 |

| 17 Grey Goosea | 12 | 6 | 1.7% | 2 | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| 18 Jack Danielsa | 4 | 5 | 1.4% | 4 | 2.20 | 8.80 |

| 19 Stella Artois | >20th | 5 | 1.4% | 3 | 2.00 | 6.00 |

| 20 Crown Royala | 18 | 5 | 1.4% | 1 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

Denotes brands that were also in the top 20 brands of affiliation as reported by youth aged 15–20 years

Other Media Content Exposure

To provide an estimate of movie alcohol brand exposure, methods previously validated for measuring exposure to branded alcohol and tobacco appearances in movies were employed (Bergamini et al., 2013). A pool of top box office movie performers from 2008 to 2010 were content coded for any alcohol brand appearance (e.g., a recognizable logo/trademark) or any brand mentioned by characters. Any alcohol brand appearance was coded, whether the alcoholic beverage was in use by a character or not. To establish reliability, ten percent of movies were double coded with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.99 for alcohol brand appearances. Movie alcohol brand exposure was a score that combined adolescent self-reported movie viewership across 50 randomly selected movie titles (each content coded for number of alcohol brand appearances) from the overall movie pool. Using the Beach Method (Sargent et al., 2008), individual exposure scores were scaled to estimate exposure to alcohol brand appearances across the full 188 movies.

Statistical Analyses

Correlations across variables of interest were plotted. Line of best fit was assessed for the association between brand prominence and youth-reported brand affiliation. Given positive skew in brand affiliation variables, a negative binomial regression was used to evaluate associations between the number of series each brand appeared in and the proportion of adolescents who endorsed that brand as their aspirational and usual brand to drink. For brand exposure and adolescent drinking analyses, multivariate logistic regressions with maximum likelihood estimation using M-plus (Muthén & Muthén 2012) software were employed to test covariate-adjusted associations between television exposures to alcohol brands and drinking outcomes for cross-sectional (N = 2012) and longitudinal models. In longitudinal models, samples were restricted to baseline non-drinkers to identify drinking initiation (N = 898) and baseline non-hazardous drinkers to identify hazardous drinking initiation (N = 1636). The analytic sample had relatively low levels of missingness (covariance coverage ranged from 0.992 to 1.000). To account for missing data and the use of dichotomous outcome variables, estimates from 20 imputed datasets were combined using multiple imputation routines in M-plus. We report all relevant methodological features, data manipulations, and variables included for analyses within this study.

Results

Descriptive information about the selected television/cable series with details about rating, viewership, and brand appearances can be found in the Table 1. Across evaluated series, one, Desperate Housewives, contained no alcohol brand appearances within the season evaluated. In contrast, Californication and True Blood depicted branded alcohol use in every episode content coded (means of 12.8 and 14.7 brands per hour respectively). Excluding Desperate Housewives, the two network television series that contained alcohol content, Friday Night Lights and 30 Rock, had nine alcohol brand appearances (0.16 per episode); series that aired on cable television had 335 alcohol brand appearances (3.38 per episode), which significantly differed at the p < 0.001 level.

Table 1.

Television show information on rating, viewership, and brand appearances

| Show | Rating | % of Youth Viewers |

# of Brand Appearances |

% of Episodes with Brands |

Brand per Episode Hour |

Mean Salience of Brand Appearance |

Brand Prominence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friday Night Lightsa | TV-PG | 22.8 | 4 | 8% | 0.62 | 2.25 | 0.18 |

| The Hills | TV-PG | 21.9 | 35 | 70% | 3.50 | 2.37 | 1.66 |

| Burn Notice | TV-PG | 29.5 | 8 | 38% | 0.71 | 2.50 | 0.95 |

| 30 Rocka | TV-14 | 16.6 | 5 | 23% | 0.62 | 2.60 | 0.59 |

| Desperate Housewivesa | TV-14 | 32.0 | 0 | 0% | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Madmen | TV-14 | 8.1 | 23 | 85% | 2.26 | 2.60 | 2.21 |

| Californication | TV-MA | 4.1 | 77 | 100% | 12.83 | 2.36 | 2.36 |

| Entourage | TV-MA | 13.4 | 21 | 75% | 3.75 | 2.05 | 1.54 |

| True Blood | TV-MA | 20.2 | 162 | 100% | 14.73 | 2.37 | 2.37 |

| Weeds | TV-MA | 14.0 | 9 | 46% | 1.38 | 2.56 | 1.18 |

TV-PG: Parental Guidance Suggested. This program contains material that parents may find unsuitable for younger children

TV-14: Parents Strongly Cautioned. This program contains some material that many parents would find unsuitable for children under 14 years of age

TV-MA: Mature Audience Only. This program is specifically designed to be viewed by adults and therefore may be unsuitable for children under 17

Denotes shows that aired on broadcast network television as compared to shows that aired on cable television

Descriptive information about the top 20 alcohol brands depicted is provided in Table 2. Budweiser appeared most often (41 appearances), with the closest brands in prevalence being Heineken (22 appearances), followed by Dos Equis (19 appearances), Abita (17 appearances), and Bombay (17 appearances). Budweiser, Solichnaya, Heineken, Johnny Walker, Corona, and Jack Daniels all appeared in four or more series (out of the 10 series coded).

With regards to viewership, about one quarter (23%) of adolescents reported never viewing any of the ten television series assessed, 27% reported watching at least one series, and 50% reported having seen episodes from two or more series in this season. In terms of brand affiliation, 46% of adolescents endorsed having an aspirational brand, and 65% of adolescents with history of alcohol use reported having a usual brand to drink (33% of the full sample). Budweiser was an outlier in its level of popularity among adolescents, selected by 9% of adolescents as their aspirational and 5% as their usual alcohol brand to drink. Smirnoff, although not highly prominent in the television series assessed, was the second most popular brand among adolescents selected by 6% as their aspirational and 4% as their usual brand to drink.

Alcohol Brand Series Count, Prominence, and Brand Affiliation

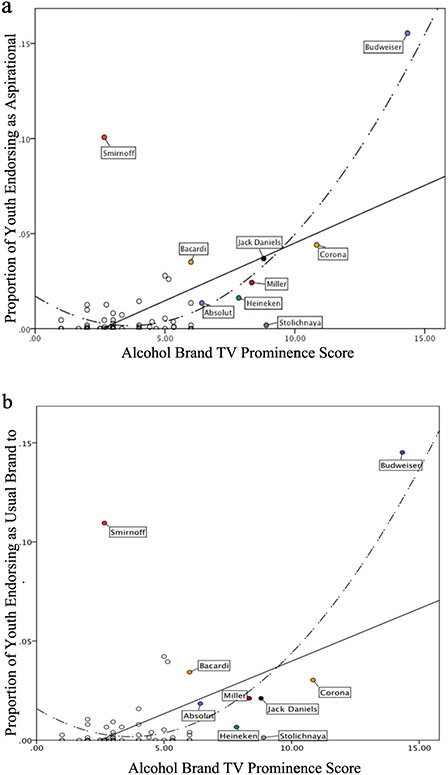

Prominence of specific brands across shows was significantly and positively associated with the percentage of youth endorsing that brand as one they aspire to drink (Fig. 1a), with a quadratic curve estimate providing the best fit to the data (adjusted R2 = 0.620, df = 83, p < 0.0001). Two outliers (Smirnoff and Budweiser) were removed, and the quadratic curve retained significantly better fit to the data than a linear estimation (p < 0.05). Similarly, the association between brand prominence and self-reported usual brand (Fig. 1b) revealed a positive quadratic association (adjusted R2 = 0.497, df = 83, p < 0.0001); however, when outliers were removed the linear trend provided the best fit to the data (adjusted R2 = 0.268, df = 83, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

a Youth reported aspirational brand by brand prominence in television shows. b Youth reported usual brand to drink by brand prominence in television shows

Negative binomial regressions revealed that brand series count (number out of the 10 series in which brand appearances occurred) related strongly with the proportion of adolescents affiliating with a given brand. In aspirational brand models, brands appearing in more series were significantly more likely to be endorsed by adolescents as their aspirational brand choice (OR two series = 10.47, 95% Confidence Interval [3.43, 31.98]; three or more series = 29.95 [7.82, 114.73]); this was also true for usual brand models (OR two series = 17.22, [5.54, 53.52]; three or more series = 33.67 [8.70, 130.39]).

Adolescent Alcohol Brand Exposure and Underage Drinking

In cross-sectional multivariable models (Table 3), after adjusting for covariates, including television viewership and movie alcohol brand exposure, exposure to alcohol brands in the ten television series retained significant associations with adolescent drinking. For the drinking initiation model, compared to no exposure adolescents, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for moderate exposure was 1.53, [1.25, 1.88], and for high exposure it was 2.14 [1.54, 2.98]. Similarly, higher exposure to television alcohol brand appearances in television series increased risk for hazardous drinking (AOR moderate exposure = 1.53, [1.15, 2.04]; high exposure = 2.18 [1.50, 3.18]).

Table 3.

Cross-sectional multivariable models of television alcohol brand exposure and drinking

| Any Drinking |

Hazardous Drinking |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age | 1.33 | 1.26; 1.42 | <0.001 | 1.30 | 1.20; 1.39 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.88 | 0.74; 1.06 | 0.257 | 0.43 | 0.34; 0.54 | <0.001 |

| White (reference) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Black | 0.82 | 0.60; 1.12 | 0.301 | 0.34 | 0.22; 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.69 | 1.25; 2.29 | 0.005 | 0.81 | 0.56; 1.17 | 0.342 |

| Other | 1.00 | 0.75; 1.33 | 0.996 | 0.88 | 0.58; 1.34 | 0.618 |

| Friend Alcohol Use | 2.22 | 1.99; 2.22 | <0.001 | 2.85 | 2.49; 3.27 | <0.001 |

| Parental Alcohol Use | 2.00 | 1.63; 2.46 | <0.001 | 1.50 | 1.19; 1.89 | <0.01 |

| Sensation Seeking | 2.35 | 1.94; 2.84 | <0.001 | 2.62 | 2.06; 3.33 | <0.001 |

| TV Viewership | 1.02 | 0.93; 1.11 | 0.728 | 1.11 | 0.99; 1.25 | 0.122 |

| Movie Brand Exposure | 1.01 | 1.01; 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.99; 1.00 | 0.361 |

| TV Brand Exposure (None, reference) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TV Brand Exposure (Moderate) | 1.53 | 1.25; 1.88 | <0.01 | 1.53 | 1.15; 2.04 | <0.05 |

| TV Brand Exposure (High) | 2.14 | 1.54; 2.98 | <0.001 | 2.18 | 1.50; 3.18 | <0.01 |

In longitudinal models (Table 4), television brand exposure contributed significantly to drinking transitions. Among baseline non-drinkers, adjusting for covariates, those with moderate television alcohol brand exposure were 1.85, [1.35, 2.55] times more likely and those with high exposure were 2.29, [1.22, 4.31] times more likely to initiate drinking at follow up as compared to no exposure adolescents. For initiation of hazardous drinking (among adolescents with no prior hazardous drinking) moderate exposure was not significantly associated with transition to hazardous drinking (AOR 1.09, [0.78, 1.51]), but high exposure was (1.88 [1.14, 3.11]). Across all models estimated, alternative models with either a continuous estimator of alcohol brand exposure or an estimator with alternative categorical cut points provided similar associations with drinking outcomes.

Table 4.

Longitudinal multivariable models of television alcohol brand exposure and drinking one year later

| Any Drinking Initiationa | Hazardous Drinking Initiationb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age | 1.36 | 1.22; 1.52 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 1.05; 1.24 | <0.05 |

| Gender | 1.23 | 0.91; 1.66 | 0.253 | 0.57 | 0.43; 0.76 | <0.01 |

| White (reference) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Black | 0.83 | 0.45; 1.52 | 0.607 | 0.72 | 0.72; 1.23 | 0.310 |

| Hispanic | 0.60 | 0.34; 1.06 | 0.138 | 0.58 | 0.36; 0.94 | 0.063 |

| Other | 0.66 | 0.42; 1.06 | 0.148 | 0.93 | 0.58; 1.51 | 0.811 |

| Friend Alcohol Use | 1.63 | 1.33; 2.00 | <0.001 | 1.92 | 1.66; 2.21 | <0.001 |

| Parental Alcohol Use | 1.60 | 1.12; 2.30 | <0.05 | 1.64 | 1.21; 2.21 | <0.01 |

| Sensation Seeking | 1.56 | 1.12; 2.18 | <0.05 | 1.34 | 0.99; 1.81 | 0.104 |

| TV Viewership | 0.88 | 0.75; 1.02 | 0.154 | 0.83 | 0.73; 0.95 | <0.05 |

| Movie Brand Exposure | 1.00 | 1.00; 1.01 | <0.05 | 1.00 | 1.00; 1.01 | <0.05 |

| TV Brand Exposure (None, reference) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TV Brand Exposure (Moderate) | 1.85 | 1.35; 2.55 | <0.01 | 1.09 | 0.78; 1.51 | 0.670 |

| TV Brand Exposure (High) | 2.29 | 1.22; 4.31 | <0.05 | 1.88 | 1.14; 3.11 | <0.05 |

Sample limited to non-drinkers at baseline (N = 898);

Sample limited to non-hazardous drinkers at baseline (N = 1636)

Of note, other significant predictors in both cross-sectional and longitudinal models were age, peer and parent drinking, sensation seeking, and movie alcohol brand exposure. Total television viewership time was not a significant predictor in any regression model. Further, females were significantly less likely to report initiation of hazardous drinking (see Table 3 & 4).

Discussion

Youth gain independent access to personalized media devices during adolescence, and changes in technology have resulted in an increased in streaming media content. This transition in how media is consumed likely changes the way alcohol industry embeds marketing within television show content, which may also change the way youth are exposed to alcohol marketing. The vast majority of prior research on youth exposure to alcohol in the media has focused on movie content or traditional alcohol advertisements, despite the fact that today’s youth primarily stream television and video content (Rideout and Robb 2019). As youth media consumption continues to evolve, the impact of embedded alcohol content within screened media content may gain import as an environmental influence on youth drinking and thus remains an important area of study. This study offers novel information through content coding of alcohol content within popular television series and evaluation of associations between pervasiveness of alcohol brand depictions, youth exposure to alcohol content within television series, and youth drinking outcomes.

The present results contribute to evidence that alcohol brands commonly appear in entertainment media, adolescents are exposed to brands through television content, and such exposures relate to brand affiliation and drinking behavior (Jackson et al., 2018). Although variability existed across series, the average number of alcohol brand appearances was greater than two per episode. Alcohol brands that appeared commonly (e.g., Budweiser, Heineken, Corona) were brands that television viewers would recognize as commonly appearing in traditional advertisements (Siegel et al., 2013; Tanski et al., 2015). As hypothesized, within alcohol brand, higher series count of television alcohol brand appearances was associated with adolescent brand affiliation. Youth exposure to alcohol brand appearances on television was associated with adolescent drinking outcomes both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, and higher doses were, generally, associated with larger effects on drinking outcomes, a finding consistent with prior literature (e.g. Hanewinkel and Sargent 2009; Sargent et al., 2006). This television alcohol brand exposure effect was independent of associations between other previously identified covariates (e.g., sensation seeking, peer/parent drinking) as well as alcohol brand exposure in movies. Our findings support prior cross-sectional research on alcohol brand exposure in television content (e.g., Ross et al., 2015) and longitudinal research on alcohol brand exposure in movie (e.g., Koordeman et al., 2012) and advertising content (e.g., Jernigan et al., 2017).

Given the increase in both alcohol product placements and access to media afforded by streaming services since the time of data collection, the frequency of alcohol brands that youth are exposed to through popular media is likely to be even higher than what the present results suggest. Accordingly, based on the theoretical framework provided by Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura 1986), one might expect that increased exposure to media depictions of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related products might shift youth perceptions of the commonality of alcohol use. Future studies targeting mechanisms (e.g., alcohol expectancies, subjective norms) important for this association would be useful to better inform intervention and prevention efforts to mitigate risks associated with media depictions of substance use.

Beyond simple exposure to media depictions, the present study also highlights the potential role of brand engagement, such as identifying a favorite and aspirational alcohol brand, and related marketing receptivity, as explained in the introduction. If the same trends found in prior alcohol and tobacco research apply, the present study’s findings for alcohol brand recognition in popular television is troubling for many reasons. Firstly, adolescents were significantly more likely to cite brands appearing more frequently in the series as their aspirational brand choice, perhaps providing another example of how the scope and expenditure of alcohol branding can impact youth drinking outcomes as found in prior research (e.g., Tanski et al., 2011). Secondly, the study’s finding that many respondents identify with and aspire to alcohol brands might signify current or future drinking behavior; studies have shown that adolescent drinkers recognize more alcohol brands than never-drinkers (Henriksen et al., 2008; Unger et al., 2003), and advertising awareness has been linked to drinking among middle school boys (Collins et al., 2003) and in high school-aged adolescents (Gabrielli et al., 2019).

Interestingly, total television viewership was not an indicator of risk for adolescent drinking onset or progression to hazardous drinking, and in fact, in longitudinal models it was protective against hazardous drinking initiation. Engagement with some levels of screened media may be protective for youth in some domains, specifically around progression of health risk behavior, a finding noted in other studies on youth screen media usage (Przybylski & Weinstein 2017, 2019). These data suggest that limiting total television viewing time may not be indicated as a recommendation to reduce youth risk for drinking, but rather, the content of television viewership should be monitored and restricted. This finding aligns with current recommendations around parental monitoring and restriction of adolescent media content (Cox et al., 2018; Gabrielli & Tanski 2020) and active engagement in discussion with adolescents about what types of media they consume (Gabrielli et al., 2018). As adolescents develop independent media viewership behaviors, a scaffolded approach to parenting that supports youth ability to critique marketing content embedded within media may be particularly important.

In prior discussions on product placements, it was noted that, “product placement merges advertising and entertainment” (Eagle & Dahl 2015). Given shifting media trends, one might expect expenditure on paid product placements to have increased. However, as of 2011 the alcohol industry reported little financial investment in paid brand placements across media venues (less than 0.12% of total marketing expenditures) (Evans et al., 2014). That being said, paid product placements may be a relatively inexpensive form of advertising. Product placements may provide some sort of reciprocal benefit (e.g. a few cases of beer for the cast if they are present in the background of a scene), thus the cost may be lower than traditional ads that require purchasing of airing time (Newell et al., 2006). Additionally, whereas a traditional ad campaign runs for a set amount of time and then is not shown again, a single paid product placement has the potential to influence viewers for years, as long as the content it is embedded within is still being viewed (Seipel et al., 2018). Streamed media contributes to this potential, as show series that have ended may continue to be accessed. For example, the True Blood series was not renewed after season 7, but the series is currently available through streaming on Amazon Prime and Hulu.

These potential compounding effects of product placements have led many researchers to call for government oversight of the alcohol industry, with a need to identify if self-regulation from industry is sufficient or if “additional independent regulation is warranted” (Eagle & Dahl 2015). Others agree, asserting that as long as the alcohol industry denies any impacts of alcohol marketing on underage drinking–and supports research to discredit the findings that say otherwise–there needs to be external regulation (Nelson 2010; Sargent 2014). Results from the present study corroborate these concerns about the current lack of independent surveillance around alcohol brand appearances in entertainment media given its identified association with adolescent drinking behavior. Indeed, a report by the Federal Trade Commission (2014) on self-regulation of marketing by the alcohol industry found 418 television placements and 140 movie placements between January and June 2011 across only 14 major alcohol advertisers; approximately 73% of industry reported alcohol product placements were in television series. This directly translates to the present findings: alcohol brand appearances were present in 9 out of 10 series assessed in the present study. Adolescents in this nationally representative sample reported watching the series, and adolescent television brand exposure was predictive of drinking outcomes; thus, within-series alcohol marketing should be further evaluated with consideration for increased regulation. Additionally, there is a broad base of evidence for the efficacy of external regulation; a review of the literature found that when regulations were imposed on alcohol marketing in a variety of countries, there were consistently decreases in alcohol-related outcomes (e.g. consumption, fatalities, etc.; Jernigan et al., 2017). Furthermore, the it has been estimated that if alcohol marketing restrictions were imposed in the 26 U.S. states where they were not at the time of publishing, 400 lives would be saved a year (Smith & Geller 2009).

Media and technology play an increasingly influential role in child developmental outcomes, particularly for adolescents, and more work is needed to understand how exposures such as alcohol brand appearances in television may impact adolescent health risk behaviors. Additional research on the brand appearances across a wider range of television series as well as additional media sources (e.g., YouTube, metacafe, social media) would offer more information on how exposures relate to adolescent behavior and allow for focused intervention and prevention efforts to limit and moderate risk. With the emerging market around cannabis and e-cigarettes, additional studies on the role of marketing across substance categories in the media and associations with uptake by adolescent populations is warranted.

Findings should be considered in light of limitations inherent within the present study. First, while adolescent socialization is likely influenced by multiple media sources, analyses were limited to viewership across 50 movies and 10 television series. Restricted representation of media exposures may contribute to underestimation of brand-specific exposure. Given the rise in youth Internet use and media access via personalized media devices, a more broadband measure of youth exposure to alcohol content across media sources would likely provide the best estimate of the impact of exposure to media alcohol content (Gabrielli et al., 2019). Despite this limitation, television media, whether accessed through traditional television sets or via personalized media devices, remains the primary form of media content utilized by youth. Therefore, the focus of this study on embedded alcohol marketing within television show content (i.e. product placement) represents an important novel aspect of marketing exposure provided by this study. While shows were selected from 10 years ago, content coding of shows is a long and arduous process. Moreover, the television shows were selected as part of a prospective study design, thus delaying the availability for follow-up data for analysis. It could be argued that show content is no longer relevant, but the shows included in this study are still available as streamed media content and continue to be accessed today. Study results may also be limited by the purposive selection methods utilized to choose this survey’s television series. Since the series were selected based on adult thematic content, the effect of series viewership may not be specific only to alcohol use. Risk behavior depictions in entertainment media are difficult to parse, and additive or exponential effects of multiple risk behavior depictions may play a role in adolescent risk behavior development.

Additionally, the ICC of 0.70, while considered “good” by most standards for rating agreement, may indicate potential measurement error due to coding discrepancies. This could suppress the effects of exposure to brand appearances on drinking outcomes. Finally, social desirability bias may have played a role in influencing respondents’ self-reporting of media viewership as well as drinking behaviors. Despite these limitations that would mostly restrict identified effects, significant associations were found supportive of study hypotheses. Future studies should seek to replicate these findings using a larger and more representative sampling of television series and should assess viewership over time.

Conclusion

The transition from adolescence to early adulthood is marked by significant social and physical changes, leaving youth particularly susceptible to positive and negative influences that will lay the groundwork for their adult life. Marketing is one of such influences, and the emergence of streaming media provides an avenue for greater marketing impact on youth viewers. However, the scope and impact of branded marketing exposure to substance use-related products nested within television content is largely unknown. The present study endeavored to quantify branded alcohol exposures in popular media programs as well as adolescent viewership of identified programs, alcohol brand affiliation, and alcohol use. We identified a high rate of adolescent exposure to branded alcohol content in the media as well as an association between media exposure to alcohol content and subsequent onset and progression of drinking behavior. We also identified a positive relationship between brand series count and youth self-reported brand affiliation. Taken together, these findings provide evidence for the influence branded alcohol content has on youth brand affiliation and general alcohol use, rendering media alcohol exposures as modifiable environmental risk factor. Limiting youth exposure to media depictions of alcohol, either on a policy level (e.g., regulations) or a family level (e.g., monitoring and restricting media content), has the potential to curb the development and progression of adolescent substance use, thus promoting the successful transition from adolescence to early adulthood.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support provided by Dr. James Sargent in allowing access to data collected through his grant (AA021347) for this manuscript.

Funding

AA021347 (Tanski & McClure); T32 DA037202 (Gabrielli) The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Biographies

Joy Gabrielli is an Assistant Professor in the Clinical and Health Psychology Department at the University of Florida. Her research interests include prevention and intervention for adolescent health risk behaviors and the role of media and technology in child development.

Erin Corcoran is a graduate student in the Clinical and Health Psychology Department at the University of Florida. Her major research interests focus on adolescent substance use behavior and modifiable environmental risk factors for youth risk behavior.

Sam P. Genis is studying medicine at the University of Nevada Reno School of Medicine. In relation to this project, his primary research interests were related to youth alcohol brand affiliation and drinking onset.

Auden C. McClure , MD, is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Her research interests center on the impact of media and marketing on youth health behaviors, including substance use and eating habits.

Susanne E. Tanski , MD, is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. Her primary research interests include prevention and intervention for youth substance use and media influence on children and adolescents.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval This study was approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Review Board (CPHS # 15445).

Informed Consent All individual participants consented to the study after being informed on the purpose of the study and its privacy policy. Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants (those aged 18 years or older) and assent and parental consent was obtained for youth participants (those under the age of 18 years).

References

- Anderson M, & Jiang J (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/05/PI_2018.05.31_TeensTech_TOPLINE.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, & Hastings G (2009). Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 44(3), 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auty S, & Lewis C (2004). Exploring children’s choice: the reminder effect of product placement. Psychology & Marketing, 21(9), 697–713. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Montiero MG (2001). AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in Primary Care. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian SK (1994). Beyond advertising and publicity: hybrid messages and public policy issues. Journal of Advertising, 23(4), 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini E, Demidenko E, & Sargent JD (2013). Trends in tobacco and alcohol brand placements in popular US movies, 1996 through 2009. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 634–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives Of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Schell T, Ellickson PL, & McCaffrey D (2003). Predictors of beer advertising awareness among eighth graders. Addiction, 98(9), 1297–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Gabrielli J, Janssen T, & Jackson KM (2018). Parental restriction of movie viewing prospectively predicts adolescent alcohol and marijuana initiation: implications for media literacy programs. Prevention Science, 19(7), 914–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, & Sargent JD (2008). Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction, 103(12), 1925–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Stoolmiller M, Wills TA, & Sargent JD (2009). Watching and drinking: expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology, 28(4), 473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, & Zhou Y (2005). Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(5), 844–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle L, & Dahl S (2015). Product placement in old and new media: examining the evidence for concern. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(3), 605–618. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore KC, Scull TM, & Kupersmidt JB (2017). Media as a “Super Peer”: how adolescents interpret media messages predicts their perception of alcohol and tobacco use norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(2), 376–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JM, Krainsky E, Fentonmiller K, Brady C, Yoeli E, & Jaroszewicz A (2014). Self-Regulation in the Alcohol Industry: Report of the Federal Trade Commission. Washington, DC: United States Federal Trade Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Flint J, & Sharma A (2019). Netflix Fights to Keep Its Most Watched Shows: ‘Friends’ and ‘The Office’. The Wall Street Journal Apr. https://www.wsj.com/articles/netflix-battles-rivals-for-its-most-watched-shows-friends-and-the-office-11556120136?shareToken=stb3190ef1056940f1bc366ef2c370ca99. [Google Scholar]

- Friestad M, & Wright P (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: how people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli J, Brennan ZLB, Stoolmiller M, Jackson KM, Tanski SE, & McClure AC (2019). A new recall of alcohol marketing scale for youth: measurement properties and associations with youth drinking status. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(5), 563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli J, Marsch L, & Tanski S (2018). TECH parenting to promote effective media management. Pediatrics, 142(1), e20173718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli J, & Tanski SE (2020). The A, B, Cs of youth technology access: promoting effective media parenting. Clinical Pediatrics, 59(4–5), 496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli J, Traore A, Stoolmiller M, Bergamini E, & Sargent JD (2016). Industry television ratings for violence, sex, and substance use. Pediatrics, 138, e20160487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmannova K, Hill KG, Bailey JA, Lee JO, Hartigan LA, Hawkins JD, & Catalano RF (2012). Examining explanatory mechanisms of the effects of early alcohol use on young adult alcohol dependence. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 73 (3), 379–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, & Sargent JD (2009). Longitudinal study of exposure to entertainment media and alcohol use among german adolescents. Pediatrics, 123(3), 989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Feighery E, Schleicher N, & Fortmann S (2008). Receptivity to alcohol marketing predicts initiation of alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42, 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson S, & Hudson D (2006). Branded entertainment: a new advertising technique or product placement in disguise? Journal of Marketing Management, 22(5–6), 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Janssen T, & Gabrielli J (2018). Media/marketing influences on adolescent and young adult substance abuse. Current addiction reports, 5(2), 146–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D, Noel J, Landon J, Thornton N, & Lobstein T (2017). Alcohol Marketing and Youth Alcohol Consumption: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies Published Since 2008. Addiction, 112, 7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2020). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975-2019: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris W, Shanklin S, Flint K, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, & Ethier K (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koordeman R, Anschutz DJ, & Engels R (2014). Self-Control and the Effects of Movie Alcohol Portrayals on Immediate Alcohol Consumption in Male College Students. Front Psychiatry, 5. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koordeman R, Anschutz DJ, & Engels RC (2012). Alcohol portrayals in movies, music videos and soap operas and alcohol use of young people: current status and future challenges. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 47(5), 612–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean SA, Basch CH, & Garcia P (2017). Alcohol and violence in 2017 National Football League Super Bowl commercials. Health Promotion Perspectives, 7(3), 163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure AC, Stoolmiller M, Tanski SE, Engels RC, & Sargent JD (2013). Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing-specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37, E404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M, Isensee B, Sargent JD, & Hanewinkel R (2011). Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 165(7), 610–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). MPlus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables–User’s guide. https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/Mplus%20Users%20Guide%20v6.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JP (2010). What is learned from longitudinal studies of advertising and youth drinking and smoking? A critical assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7, 870–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell J, Salmon CT, & Chang S (2006). The hidden history of product placement. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50(4), 575–594. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen. (2017). Super Bowl Li Draws 111.3 Million Tv Viewers, 190.8 Million Social Media Interactions. Nielsen Insights. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2017/super-bowl-li-draws-111-3-million-tv-viewers-190-8-million-social-media-interactions/. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski AK, & Weinstein N (2017). A large-scale test of the Goldilocks Hypothesis: Quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychological Science, 28(2), 204–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski AK, & Weinstein N (2019). Digital screen time limits and young children’s psychological well-being: evidence from a population-based study. Child Development, 90(1), e56–e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout VJ (2016). Measuring time spent with media: the Common Sense census of media use by US 8- to 18-year-olds. Journal of Children and Media, 10(1), 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout VJ, & Robb MB (2019). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SP, Siegel MB, DeJong W, Ross CS, Naimi T, Albers A, Skeer M, Rosenbloom DL, & Jernigan DH (2016). Brands matter: major findings from the alcohol brand research among underage drinkers (ABRAND) project. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(1), 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CS, Maple E, Siegel M, DeJong W, Naimi TS, Padon AA, Borzekowski DL, & Jernigan DH (2015). The relationship between population-level exposure to alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth in the US. Alcohol Alcohol, 50(3), 358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CA, & Russell DW (2009). Alcohol messages in primetime television series. Journal Consumer Affairs, 43(1), 108–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CA, Russell DW, Boland WA, & Grube JW (2014). Television’s cultivation of american adolescents’ beliefs about alcohol and the moderating role of trait reactance. Journal of Children and Media, 8(1), 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD (2014). Alcohol marketing and underage drinking: time to get real. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38 (12), 2886–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Tanski S, Stoolmiller M, & Hanewinkel R (2010). Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction, 105(3), 506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson J, & Gibbons FX (2006). Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 67(1), 54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Worth KA, Beach M, Gerrard M, & Heatherton TF (2008). Population-based assessment of exposure to risk behaviors in motion pictures. Communication Methods and Measures, 2(1–2), 134–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seipel M, Freeman J, & Brubaker P (2018). Key factors in understanding trends in hollywood product placements from 2005 to 2015. Journal of Promotion Management, 24(6), 755–773. [Google Scholar]

- Shrum LJ (2012). The psychology of entertainment media: Blurring the lines between entertainment and persuasion. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, DeJong W, Naimi TS, Fortunato EK, Albers AB, Heeren T, Rosenbloom DL, Ross C, Ostroff J, Rodkin S, King C, Borzekowski DL, Rimal RN, Padon AA, Eck RH, & Jernigan DH (2013). Brand-specific consumption of alcohol among underage youth in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(7), 1195–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Ross CS, Albers AB, DeJong W, King C 3rd, Naimi TS, & Jernigan DH (2016). The relationship between exposure to brand-specific alcohol advertising and brand-specific consumption among underage drinkers–United States, 2011-2012. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 42(1), 4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, & Foxcroft DR (2009). The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health, 9(51), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RC, & Geller ES (2009). Marketing and alcohol-related traffic fatalities: Impact of alcohol advertising targeting minors. Journal of Safety Research, 40(5), 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburger V (2007). Super-peer theory. In Arnett JJ (Ed), Encyclopedia of children, adolescents, and the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tanski SE, McClure AC, Jernigan DH, & Sargent JD (2011). Alcohol Brand Preference and Binge Drinking Among Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 165(7), 675–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanski SE, McClure AC, Li Z, Jackson K, Morgenstern M, Li Z, & Sargent JD (2015). Cued recall of alcohol advertising on television and underage drinking behavior. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(3), 264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TV Parental Guidelines - Ratings. (2019). TV Parental Guidelines Monitoring Board. http://www.tvguidelines.org/resources/TheRatings.pdf.

- Unger JB, Schuster D, Zogg J, Dent CW, & Stacy AW (2003). Alcohol advertising exposure and adolescent alcohol use: a comparison of exposure measures. Addiction Research & Theory, 11, 177–193. [Google Scholar]