Abstract

Background

As unplanned Emergency Department (ED) return visits (URVs) are associated with adverse health outcomes in older adults, many EDs have initiated post-discharge interventions to reduce URVs. Unfortunately, most interventions fail to reduce URVs, including telephone follow-up after ED discharge, investigated in a recent trial. To understand why these interventions were not effective, we analyzed patient and ED visit characteristics and reasons for URVs within 30 days for patients aged ≥ 70 years.

Methods

Data was used from a randomized controlled trial, investigating whether telephone follow-up after ED discharge reduced URVs compared to a satisfaction survey call. Only observational data from control group patients were used. Patient and index ED visit characteristics were compared between patients with and without URVs. Two independent researchers determined the reasons for URVs and categorized them into: patient-related, illness-related, new complaints and other reasons. Associations were examined between the number of URVs per patient and the categories of reasons for URVs.

Results

Of the 1659 patients, 222 (13.4%) had at least one URV within 30 days. Male sex, ED visit in the 30 days before the index ED visit, triage category “urgent”, longer length of ED stay, urinary tract problems, and dyspnea were associated with URVs. Of the 222 patients with an URV, 31 (14%) returned for patient-related reasons, 95 (43%) for illness-related reasons, 76 (34%) for a new complaint and 20 (9%) for other reasons. URVs of patients who returned ≥ 3 times were mostly illness-related (72%).

Conclusion

As the majority of patients had an URV for illness-related reasons or new complaints, these data fuel the discussion as to whether URVs can or should be prevented.

Trial registration

For this cohort study, we used data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT). This trial was pre-registered in the Netherlands Trial Register with number NTR6815 on the 7th of November 2017.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-023-04021-x.

Keywords: Older patients, Emergency department, Geriatric, Unplanned return, Return presentations

Introduction

With demographic change, there is an increase in Emergency Department (ED) presentations by patients aged 70 years and older worldwide [1]. Up to 25% of these older patients have an unplanned ED return visit (URV) within one month [2–6]. Since URVs in older adults are associated with adverse health outcomes, they are often viewed as negative [3, 7]. Therefore, many EDs have initiated post-discharge interventions in order to reduce URVs. [8, 9]

Many post-ED discharge intervention programs are focused on older patients at high risk for hospital return. However, prediction tools that have been developed to identify patients at risk have poor predictive accuracy, contain different predictors, and are often not suitable for clinical use [4, 10–13]. However, all previous studies consistently report that the majority of older adults who return to the ED suffer from chronic and often comorbid health conditions, functional dependency or cognitive problems [2, 10, 14, 15]. In addition, several (psycho)social factors, such as living alone, lack of social support and uncertainty about the health condition, as well as insufficient understanding or provision of discharge information are found to be associated with URVs in older adults. [2, 6, 7, 11, 14–19]

Several of these predicting factors could be addressed through specific interventions, such as patient education and community follow-up by a geriatric nurse. However, systematic reviews evaluating the effects of post-discharge interventions initiated in the ED have found that many were not effective in reducing ED re-attendances [8, 9]. In a pragmatic randomized controlled trial, our research group also failed to find a beneficial effect of a transitional care program, consisting of post-ED discharge telephone follow-up for older adults, on the reduction of unplanned hospital admissions and URVs within 30 days after ED discharge [20].

In order to understand why these interventions are not effective in reducing URVs, more insight is needed into the reasons why older patients return to the ED. Therefore, we investigated the frequencies, associated patient and ED visit characteristics and reasons for URVs within 30 days after the index ED visit among patients aged ≥ 70 years. In addition, we examined whether specific categories of reasons for URVs were associated with the number of URVs per patient.

Methods

Study design and setting

For this study, we used data from a pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT). The research question of this RCT was whether a telephone follow-up call reduces unplanned hospitalizations and URVs within 30 days of ED discharge, compared to a satisfaction survey call. The trial was conducted in the EDs of Haaglanden Medical Center (HMC), a non-academic teaching hospital in the Netherlands, from February 1, 2018 to July 1, 2019. In this RCT, 3175 patients were allocated to either the intervention (n = 1516) or the control (n = 1659) group, according to the month of their ED visit; patients included in odd months received an intervention telephone call to identify post-discharge problems and to offer additional information, and patients included in even months received a satisfaction survey telephone call [20]. The Medical Ethics Review Committee of HMC waived the necessity for formal approval of the study as it closely followed routine care (METC Zuidwest Holland, nr. 17–028).

Patients

For this study, only observational data from control group patients were used to exclude a possible effect of the intervention telephone follow-up call. Patients aged ≥ 70 years who were discharged from one of the EDs of HMC to an unassisted living environment were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: admission to the hospital, discharge to a nursing home, another care facility or assisted living environment, and planned follow-up appointment at an outpatient clinic or at the ED within 24 h [20].

Data collection and measurements

Unplanned ED return visits (URVs)

Data on ED return visits were collected from the electronic hospital system (EHS). ED return visits that could not be foreseen were defined as URVs [21]. The index ED visit was the first ED visit during the study period that was followed by a telephone call.

Baseline data

We used baseline data that were associated with URVs in previous studies, including demographics (age [4, 10, 13], gender [4, 5, 10], whether or not living alone [2, 3, 11, 22],) and ED visit characteristics (mode of arrival, Manchester Triage System triage urgency level [23], chief complaint, ED length of stay [2, 10, 11, 24]). We also used data concerning level of ED crowding at discharge, measured by the National Emergency Department OverCrowding Scale (NEDOCS) [25]. Data were abstracted from the EHS by an information technology specialist, who was not involved in the study [20].

Determination of reasons for URVs

Prior to the start of the study, reasons for URVs were defined and categorized, based on findings in the literature (see Additional file 1) [4, 7, 15, 19, 26]. Two investigators (MvLvG and IEV), both medical doctors, independently determined and categorized the reason for each URV by reviewing the emergency medical records (EMRs). In case of disagreement, the EMR was reviewed and reasons for ED return were discussed until consensus was achieved. In case of no agreement, the EMR was reviewed by a third investigator (MCvdL) for the final decision. This study method has been used in previous studies on URVs [16, 26–28]. During analyses, we found that only few URVs were categorized as physician-related, system-related or not classifiable. Therefore, these three categories have been merged into the “other reasons” category. This resulted in the following four main categories: 1. patient-related reasons, 2. illness-related reasons, 3. new complaints and 4. other reasons (see Additional file 1). The study was conducted in adherence to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement [29].

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous data were skewed and therefore presented as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Differences in characteristics of patients with and without URVs were analyzed using X2-tests and univariable logistic regression.

The X2-test was used to examine the association between number of URVs per patient and the categories of reasons for URVs. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). If a patient had multiple URVs during the 30-day follow up period, only the first URV was included to determine the reason for unplanned return and to assess associations between patient and index ED visit characteristics and occurrence of an URV. To investigate whether specific categories of reasons for URVs were associated with the number of URVs per patient, all URVs within 30 days after the index ED visit were included in the analysis.

Inter-rater reliability regarding the initial determination of reasons and categories of URVs was measured with Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Of the 1659 patients, 222 (13.4%) had at least one URV within 30 days. The total number of URVs within 30 days was 279.

Patient and ED visit characteristics associated with URVs

Table 1 shows the differences in baseline patient and index ED visit characteristics between patients with and without an URV. In univariate analysis, the following factors were associated with an URV within 30 days: male sex, ED visit in the 30 days before the index ED visit, triage category “urgent”, longer length of ED stay, and the chief complaints “urinary tract problems”, and “dyspnea”.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and index Emergency Department visit characteristics of patients with and without an URV

| Unplanned ED return visit (URV) ≤ 30 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 222) | No (n = 1437) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 78 (73–83) | 78 (73–83) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0)a |

| Male sex, n (%) | 106 (47.7) | 588 (40.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) |

| Living without partner, n (%)b | 83 (42.3) | 413 (37.7) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| Characteristics of index ED visit | |||

| Mode of referral, n (%) | |||

| - Self-referral | 52 (23.4) | 307 (21.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| - General practitioner | 65 (29.3) | 485 (33.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| - Medical specialist | 44 (19.8) | 246 (17.1) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) |

| ED visit ≤ 30 days before index visit, n (%) | 45 (20.3) | 164 (11.4) | 2.0 (1.4–2.8) |

| Arrival by ambulance, n (%) | 79 (35.6) | 476 (33.1) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| Triage category urgent, n (%)c | 168 (76.4) | 999 (70.0) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) |

| ED visit at daytime, n (%) | 153 (68.9) | 1009 (70.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) |

| Length of ED stay (minutes), median (IQR) | 179 (128–242) | 151 (106–204) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1)ad |

| NEDOCS at discharge ≥ 60, n (%)e | 66 (34.6) | 425 (32.9) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| Chief complaint, n (%) | |||

| - Urinary tract problems | 16 (7.2) | 47 (3.3) | 2.3 (1.3–4.1) |

| - Headache or neurological problems | 10 (4.5) | 55 (3.8) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) |

| - Wounds | 11 (5.0) | 76 (5.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) |

| - Abdominal pain | 16 (7.2) | 76 (5.3) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) |

| - Syncope or palpitations | 8 (3.6) | 90 (6.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

| - Dyspnea | 29 (13.1) | 116 (8.1) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) |

| - Malaise | 19 (8.6) | 131 (9.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) |

| - Chest pain | 28 (12.6) | 177 (12.3) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) |

| - Limb complaints | 37 (16.7) | 299 (20.8) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) |

| - Fall or trauma | 48 (10.7) | 358 (13.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| - Other complaints | 17 (7.7) | 152 (10.6) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

ED Emergency department, NEDOCS National emergency department overcrowding scale, IQR Interquartile range, n number, URV Unplanned emergency department return visit

a In univariable logistic regression model

b Living condition unknown in 26 patients with URV and in 341 patients without URV

c Triage category urgent: red, orange and yellow according to Manchester Triage System. Triage category missing in 2 patients with URV and in 10 patients without URV

d Per 10 min increase in length of stay; OR value of 1.0 is due to rounding

e If the NEDOCS at discharge is ≥ 60, the ED is considered to be busy. NEDOCS at discharge was missing in 31 patients with URV and 144 patients without URV, due to technical malfunction of electronic hospital system on days that patients were discharged from the ED

Reasons for unplanned ED return

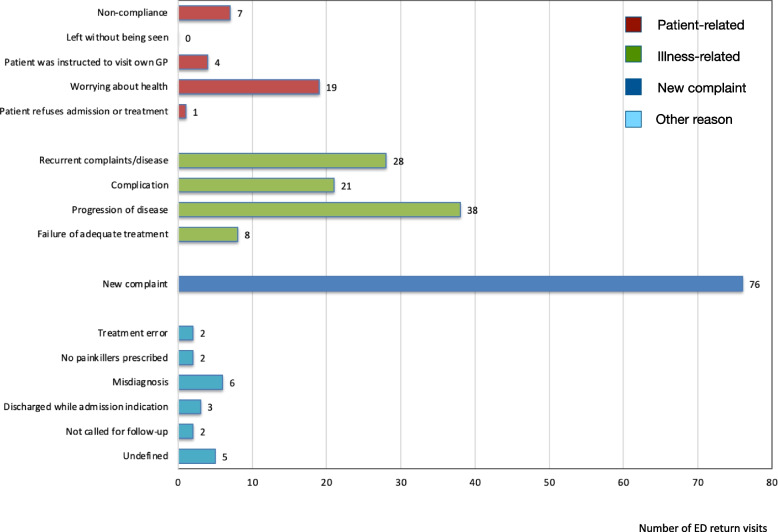

Figure 1 shows the number of URVs per reason for return. Patient-related reasons for URVs were found in 31 (14%) of the 222 patients with one or more URVs. The two most frequently occurring patient-related reasons for URVs were non-compliance with discharge instructions (n = 7), and worrying about health (n = 19). Illness-related reasons for URVs were found in 95 (43%) of the 222 patients, of which recurrent complaints/disease (n = 28) and progression of disease (n = 38) were the two largest subgroups. A new complaint was the reason for URV in 76 (34%) of the 222 patients, and 20 (9%) out of the 222 patients had an URV for other reasons. Within the latter category, 6 of the 20 patients were misdiagnosed during the index ED visit, resulting in inappropriate treatment. Other physician-related and system-related reasons occurred in < 2% of the 222 patients. Five URVs could not be classified and were therefore coded as “undefined”.

Fig. 1.

Reasons for unplanned Emergency Department (ED) return visits (n = 222), divided into four categories

Frequent URVs and reasons for ED return

Of the 222 patients with URVs, 176 (79.2%) had one URV, 39 (17.6%) had two URVs and 7 (3.2%) had three or more URVs within 30 days (Table 2). Most URVs in patients with one or two URVs were illness-related (40.9% and 46.2%, respectively) or because of a new complaint (38.0% and 30.8%, respectively). Patients with three or more URVs also returned mainly for illness-related reasons (72.0%), followed by patient-related reasons (24.0%), while new complaints were less common (4.0%).

Table 2.

Association between the number of URVs per patient and per category of reasons for URVs

| Number of URVs per patient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ≥ 3 | Total | |

| Number of patients, n (%) | 176 (79.2) | 39 (17.6) | 7 (3.2) | 222 |

| Total number of URVs, n (%) | 176 (63.1) | 78 (28.0) | 25 (9.0) | 279 |

| Category reasons for URV: | ||||

| Patient-related, n (%) | 22 (12.5) | 10 (12.8) | 6 (24.0) | 38 |

| Illness-related, n (%) | 72 (40.9) | 36 (46.2) | 18 (72.0) | 126 |

| New complaint, n (%) | 67 (38.0) | 24 (30.8) | 1 (4.0) | 92 |

| Other, n (%) | 15 (8.5) | 8 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 23 |

ED Emergency department, n number, URV Unplanned emergency department return visit

Inter-rater reliability regarding assessment of reasons and categories for URVs

The inter-rater reliability after initial independent determination and categorization of the reasons for the URVs, measured with Cohen’s kappa coefficient, was 0.57. All disagreements concerning the determination of the reasons for URVs were solved by discussion between the two researchers and hence, the judgement of a third researcher for the final decision was not needed.

Discussion

In this study, we found that 222 of the 1659 (13.4%) older adults had at least one URV within 30 days after being discharged from the ED. Of them, 171 (77%) returned for medical reasons, including 95 (43%) for illness-related problems and 76 (34%) for new medical complaints unrelated to the presenting problem of the index ED visit. URVs for patient-related reasons occurred in only 31 (14%) patients. Also, patients with more than one URV returned mainly for illness-related reasons.

The URV rate in our study was comparable with URV rates among older adults reported in other studies [2–4, 10, 30]. We also found that male sex [2, 4, 14, 15], an ED visit in the 30 days before the index ED visit [2, 10, 11, 14], triage category “urgent”, and a longer length of ED stay [24] were more common in patients with an URV. In accordance with other studies, we found that the chief complaints “urinary tract problems” [26], and “dyspnea” [15, 19, 26, 31] were associated with URVs.

Although transitional care programs that focus on patient education and post-discharge support may have a positive effect on the patient’s capacity for self-care, disease control and perceived support [32–34], the limited number of patient-related URVs found in our study may explain why many of these programs do not reduce URVs. Our finding that most older adults returned to the ED for illness-related reasons or new problems suggests that a substantial number of patients needed diagnostic work-up of their health problem and/or acute care. This fuels the discussion of whether URVs can and need to be prevented. If the aim is to divert older patients from the ED, it will have to be sorted out where else diagnostic work-ups can be performed and patients can receive the necessary (acute) care outside the ED. This will depend on the organization of the health care system and should therefore be investigated locally. An example is the organization of an acute geriatric community hospital for older adults [35]. On the other hand, as the ED is organized and equipped to conduct targeted diagnostic work-ups and deliver acute care, it may be more feasible to make existing EDs more senior-friendly by applying the initiatives already described [36–39]. Interventions focusing on close collaboration between primary care, hospital care, and community services may be more successful in reducing unplanned ED visits for older adults than interventions involving only the ED. Within these collaborations, it may be easier to deliver the best care for the patient at the most suitable location. It would be interesting to explore such collaborations in future studies [40, 41].

Strengths and limitations

We were able to compare an extensive set of patient and ED visit characteristics between patients with and without URVs. Although previous studies mentioned reasons for URVs in older adults, this is one of the few studies that investigated the frequencies of the different reasons for URVs in older adults [2, 7]. Data were prospectively collected and derived from the hospital database to diminish confounding by recall bias.

Some limitations, however, could be considered. The reasons for URVs were defined and categorized prior to the start of the study and based on explicit criteria, used in previous studies. However, the reasons for URVs were determined retrospectively. By having the URVs assessed by two independent researchers, we tried to comply with the classification criteria as much as possible. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.57, reflecting a moderate inter-rater reliability of the categorization system, may be a limitation.

Furthermore, not all data about health determinants that are associated with hospital return were available. Finally, this study was conducted in two EDs of a non-academic hospital in the Netherlands. The findings may not be generalizable to all EDs. However, two studies, one conducted in a Dutch academic ED and one in two Australian large referral hospital EDs, reported comparable percentages of URVs for illness-related and patient-related reasons [7] and for new complaints [2].

Conclusion

In this study, most older patients returned unplanned to the ED for medical reasons, whereas URVs for patient-related reasons, such as uncertainty about health or misunderstanding of discharge instructions, were less common. These findings may explain why many transitional care programs that focus on patient education and post-discharge support are ineffective in reducing URVs. In addition, the results suggest that most patients who return to the ED require urgent care. This fuels the discussion as to whether URVs can or need to be prevented.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Definitions of reasons used to analyze unplanned emergency department return visits (URV) and categorization of the reasons.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency department

- URV

Unplanned emergency department return visit

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- HMC

Haaglanden medical center

- n

Number

- METC

Medisch ethische toetsings commissie

- EHS

Electronic hospital system

- NEDOCS

National emergency department overcrowding scale

- EMR

Emergency medical record

- STROBE

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- IQR

Interquartile ranges

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

MvLvG and MCvdL conceived and designed the study, which was further developed with advice from IEV, JG and RCvdM. IEV and MvLvG independently determined and categorized the reason for each URV. MvLvG and IEV managed the data. MvLvG analyzed the data and MCvdL, JG and RCvdM provided statistical advice. MvLvG drafted the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. MvLvG takes responsibility for the article as a whole.

Funding

The corresponding author (Merel van Loon-van Gaalen) received a grant from the Jacobus Foundation in The Hague, The Netherlands, for the conduction of this study. The Jacobus Foundation is a non-commercial trust that supports education and research projects with a focus on Neurology and Psychiatry within the Haaglanden Medical Center. The sponsor had neither a role in the design and conduct of the study, nor in the data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the Board of Directors of Haaglanden Medical Center.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of Southwest Holland waived the necessity for formal approval of the study as it closely followed routine care (nr. 17–028).

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and their legal guardian(s).

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, Gold G. Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendts G, Fitzhardinge S, Pronk K, Hutton M, Nagree Y, Donaldson M. Derivation of a nomogram to estimate probability of revisit in at-risk older adults discharged from the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:249–254. doi: 10.1007/s11739-012-0895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:238–247. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Gelder J, Lucke JA, de Groot B, et al. Predictors and outcomes of revisits in older adults discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:735–741. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graf CE, Giannelli SV, Herrmann FR, et al. Identification of older patients at risk of unplanned readmission after discharge from the emergency department - comparison of two screening tools. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;141:w13327. doi: 10.57187/smw.2012.13327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hastings SN, Barrett A, Weinberger M, et al. Older patients' understanding of emergency department discharge information and its relationship with adverse outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2011;7:19–25. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31820c7678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driesen B, Merten H, Wagner C, Bonjer HJ, Nanayakkara PWB. Unplanned return presentations of older patients to the emergency department: a root cause analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:365. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01770-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crede SH, O'Keeffe C, Mason S, et al. What is the evidence for the management of patients along the pathway from the emergency department to acute admission to reduce unplanned attendance and admission? an evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:355. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2299-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes JM, Freiermuth CE, Shepherd-Banigan M, et al. Emergency department interventions for older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1516–1525. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowthian J, Straney LD, Brand CA, et al. Unplanned early return to the emergency department by older patients: the Safe Elderly Emergency Department Discharge (SEED) project. Age Ageing. 2016;45:255–261. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCusker J, Cardin S, Bellavance F, Belzile E. Return to the emergency department among elders: patterns and predictors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:249–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hastings SN, Purser JL, Johnson KS, Sloane RJ, Whitson HE. Frailty predicts some but not all adverse outcomes in older adults discharged from the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1651–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaMantia MA, Platts-Mills TF, Biese K, et al. Predicting hospital admission and returns to the emergency department for elderly patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:252–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Šteinmiller J, Routasalo P, Suominen T. Older people in the emergency department: a literature review. Int J Older People Nurs. 2015;10:284–305. doi: 10.1111/opn.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheikh S. Risk factors associated with emergency department recidivism in the older adult. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20:931–938. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.7.43073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keith KD, Bocka JJ, Kobernick MS, Krome RL, Ross MA. Emergency department revisits. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:964–968. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(89)80461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rising KL, Padrez KA, O'Brien M, Hollander JE, Carr BG, Shea JA. Return visits to the emergency department: the patient perspective. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:377–386.e373. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen LM, GregersenØstergaard L, Maribo T, Kirkegaard H, Petersen KS. Returning to everyday life after discharge from a short-stay unit at the emergency department-a qualitative study of elderly patients' experiences. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019;14:1563428. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2018.1563428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trivedy CR, Cooke MW. Unscheduled return visits (URV) in adults to the emergency department (ED): a rapid evidence assessment policy review. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:324–329. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Loon-van GM, van der Linden MC, Gussekloo J, van der Mast RC. Telephone follow-up to reduce unplanned hospital returns for older emergency department patients: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:3157–3166. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landrum L, Weinrich S. Readmission data for outcomes measurement: identifying and strengthening the empirical base. Qual Manag Health Care. 2006;15:83–95. doi: 10.1097/00019514-200604000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCusker J, Healey E, Bellavance F, Connolly B. Predictors of repeat emergency department visits by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackway-Jones KMJ, Windle J. Emergency triage. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verelst S, Pierloot S, Desruelles D, Gillet JB, Bergs J. Short-term unscheduled return visits of adult patients to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss SJ, Derlet R, Arndahl J, et al. Estimating the degree of emergency department overcrowding in academic medical centers: results of the National ED Overcrowding Study (NEDOCS) Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Linden MC, Lindeboom R, de Haan R, et al. Unscheduled return visits to a dutch inner-city emergency department. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7:23. doi: 10.1186/s12245-014-0023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereira L, Choquet C, Perozziello A, et al. Unscheduled-return-visits after an emergency department (ED) attendance and clinical link between both visits in patients aged 75 years and over: a prospective observational study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu CL, Wang FT, Chiang YC, et al. Unplanned emergency department revisits within 72 hours to a secondary teaching referral hospital in Taiwan. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biese KJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Cai J, et al. Telephone follow-up for older adults discharged to home from the emergency department: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:452–458. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy M, Cho A, Stavig A, et al. Understanding frequent emergency department use among primary care patients. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21:24–31. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith S, Mitchell C, Bowler S. Standard versus patient-centred asthma education in the emergency department: a randomised study. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:990–997. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00053107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowthian JA, Lennox A, Curtis A, et al. Hospitals and patients WoRking in Unity (HOW R U?): telephone peer support to improve older patients' quality of life after emergency department discharge in Melbourne, Australia-a multicentre prospective feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e020321. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1095–1107. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ribbink ME, Macneil-Vroomen JL, van Seben R, Oudejans I, Buurman BM. Investigating the effectiveness of care delivery at an acute geriatric community hospital for older adults in the Netherlands: a protocol for a prospective controlled observational study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e033802. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Emergency Physicians. American Geriatrics Society. Emergency Nurses Association. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines Task Force Geriatric emergency department guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:e7–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, et al. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:2237–2245. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mooijaart SP, Lucke JA, Brabrand M, Conroy S, Nickel CH. Geriatric emergency medicine: time for a new approach on a European level. Eur J Emerg Med. 2019;26:75–76. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blomaard LC, de Groot B, Lucke JA, et al. Implementation of the acutely presenting older patient (APOP) screening program in routine emergency department care : A before-after study. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;54:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00391-020-01837-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendry A. Creating an Enabling Political Environment for Health and Social Care Integration. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16:7. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(6):CD007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Definitions of reasons used to analyze unplanned emergency department return visits (URV) and categorization of the reasons.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with permission of the Board of Directors of Haaglanden Medical Center.