Significance

During development, changes in chromatin structure regulate gene expression dynamics. A detailed understanding of gene regulatory networks will improve our understanding of organogenesis and disease mechanisms. Using single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (snATAC-seq), we comprehensively investigate the single-cell gene regulatory landscape during kidney organoid differentiation.

Keywords: kidney organoid, scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, CUT&RUN, CRISPR interference

Abstract

Kidney organoids differentiated from pluripotent stem cells are powerful models of kidney development and disease but are characterized by cell immaturity and off-target cell fates. Comparing the cell-specific gene regulatory landscape during organoid differentiation with human adult kidney can serve to benchmark progress in differentiation at the epigenome and transcriptome level for individual organoid cell types. Using single-cell multiome and histone modification analysis, we report more broadly open chromatin in organoid cell types compared to the human adult kidney. We infer enhancer dynamics by cis-coaccessibility analysis and validate an enhancer driving transcription of HNF1B by CRISPR interference both in cultured proximal tubule cells and also during organoid differentiation. Our approach provides an experimental framework to judge the cell-specific maturation state of human kidney organoids and shows that kidney organoids can be used to validate individual gene regulatory networks that regulate differentiation.

The mammalian kidney contains more than 20 specialized cell types acting together to maintain homeostasis by regulating water and electrolyte balance, blood pressure, and waste excretion among other functions. Kidneys are composed of nephrons which consist of a glomerulus and renal tubule which filters blood to ultimately produce urine. Nephron dysfunction leads to chronic kidney disease (CKD) which affects 9.1% of the population worldwide (1). A more detailed understanding of kidney cell types and their development will provide a foundation on which to build replacement cell types for regenerative medicine approaches to treat kidney failure.

Epigenetic regulation plays a critical role in controlling cell differentiation during development. Chromatin accessibility regulates the potential for gene expression in part by enabling access of transcription factors to bind regulatory genomic DNA sequences. The analysis of chromatin accessibility profiles combined with gene transcription at single-cell resolution allows the inference of gene regulatory networks underpinning cellular identity (2–8), including in the developing mouse and human adult kidneys (9–11). Recent technological advances allow the joint profiling of transcription and chromatin accessibility in the same cell providing for enhanced detection of genomic features regulating cell differentiation (12–14).

Kidney organoids differentiated from human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) have provided unique opportunities to study human kidney development and disease modeling in vitro (15–25). Several established protocols generate organoids containing variable numbers of nephrons, including glomerular podocytes (POD), parietal epithelial cells (PEC), proximal tubules (PT), loop of Henle (LOH), distal nephron epithelial cells (DN) that include early distal tubules (DT) and connecting segment (CS), as well as stromal interstitial cells (ST) through posterior intermediate mesoderm (PIM) induction (26–33). Other protocols have reported methods to generate branching ureteric bud and collecting duct cell types through more rigorous lineage selection (34–39). Studies utilizing single-cell transcriptomics have revealed that kidney organoids contain not only a diverse range of kidney cell types but also off-target cells, such as neurons and melanocytes (40–42). However, how the epigenetic landscape changes during organoid differentiation and how similar the chromatin accessibility patterns are to mature human kidney remain undefined.

Here, we have generated a multimodal atlas of kidney organoid differentiation with combined single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) and single-nucleus assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (snATAC-seq). We identify cell type-specific chromatin accessibility and predict cis-regulatory links between ATAC peaks and target genes. By direct comparison with human adult kidney (HAK), kidney organoid cell types showed broad chromatin accessibility to their marker gene bodies, but absences of chromatin accessibility in promoter and putative enhancer regions of maturation-related genes, reflecting the epigenetic immaturity of organoid cell types. Changes in transcription factor expression during differentiation were associated with enrichment of their corresponding motifs in ATAC peaks and target gene expression. We used this multiomic atlas to identify a putative HNF1B gene regulatory network that we validated during organoid differentiation by targeting the promoter and enhancer regions of the HNF1B gene with CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), resulting in impaired PT and LOH lineage specification.

Results

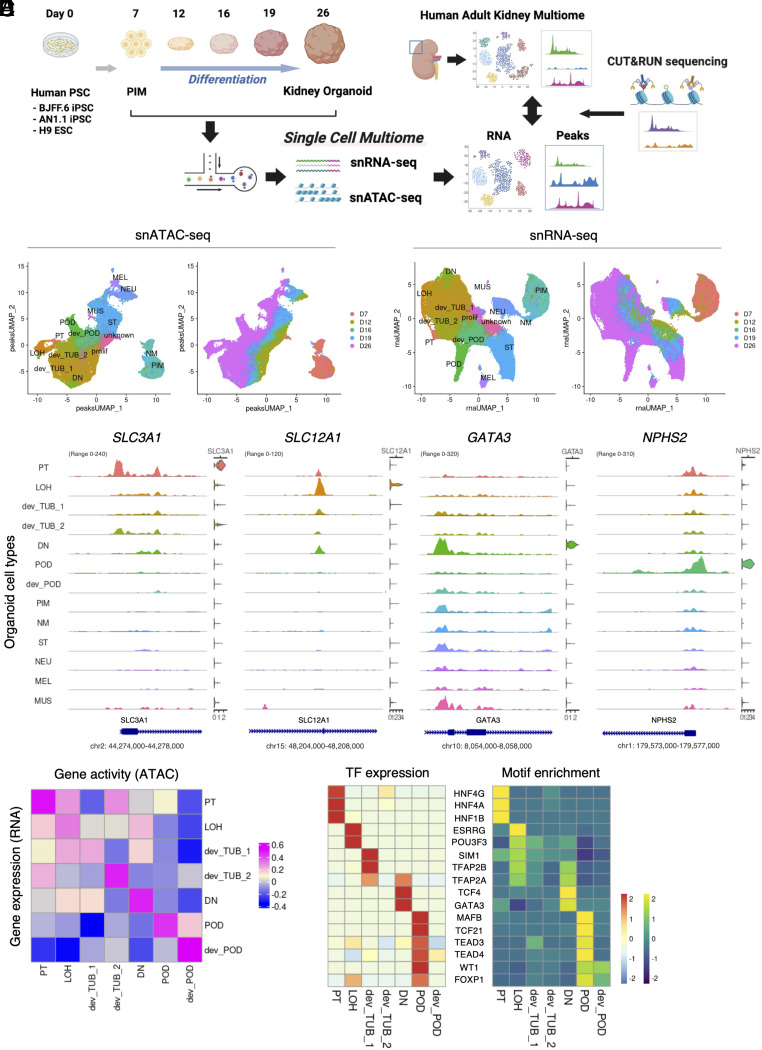

Single-Cell Multiomic Reconstruction of Kidney Organoid Differentiation.

We induced kidney organoids from three different human PSC lines: BJFF.6, AN1.1 human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), and H9 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) with a commonly used protocol (27, 43). The resulting kidney organoids showed robust epithelialization and contained multiple nephron segments, including POD (WT1+), PT (LTL+), and LOH and DN (CDH1+) segments (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). We next collected samples at multiple time points from day 7 to day 26 during differentiation and generated snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq libraries from each timepoint using 10X Genomics Multiome kits to simultaneously measure RNA and chromatin accessibility from the same cell (Fig. 1A). After sequencing and quality control, we performed batch correction between samples and merged all time points (Materials and Methods, SI Appendix, Table S1, and Dataset S1). The integrated multiome dataset included developing nephron epithelia from earlier time points and at later timepoints contained multiple differentiated epithelial cell types (Fig. 1 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S1 D and E and S2 and Table S2). As expected, we also observed off-target cells, such as neurons, muscle cells, and melanocytes (Fig. 1 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C–E), consistent with our previous findings (40). When analyzing cell clusters over time, there was clear progression from a primary mesoderm cluster to intermediary developing clusters at the middle time points and finally to more differentiated cell types at day 26. Each cell type expressed RNA encoding representative marker genes and chromatin accessibility around the transcription start site (TSS) of that marker gene (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4). We also confirmed that PIM cells at day 7 expressed multiple nephron progenitor cell markers (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Interestingly, chromatin accessibilities to the distal regulatory peaks of MEOX1 and CITED1 genes with high cis-regulatory link scores decreased along differentiation, suggesting that these peaks represent putative enhancers regulating gene expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B and C). We calculated gene activity scores from chromatin accessibility and compared this to cognate RNA expression. This revealed good correlations for differentiated cell types, with lesser correlation for developing tubule and LOH (Fig. 1E). Gene activity in the PT also showed moderate correlation to LOH gene expression, and LOH showed moderate correlation to DN.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of gene expression and open chromatin accessibility of human kidney organoid differentiation. (A) Schematic of this study. Samples were collected at multiple time points from day 7 to day 26 during organoid differentiation. The collected samples were dissociated into single cells and nuclei were extracted. snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq libraries were generated from the extracted nuclei using the 10X Genomics single-cell ATAC and gene expression kit. After sequencing, each organoid multiome dataset was merged and processed for analysis. Human adult kidney multiome dataset [Muto et al. (10)] was used to relatively evaluate day 26 kidney organoids. CUT&RUN sequencing was employed to evaluate chemical annotation of ATAC peaks. (B) UMAP plots of chromatin accessible peaks of the merged kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset. Left plot shows each organoid cell type cluster. Right plot shows origin of time points during differentiation. PT, proximal tubule; LOH, Loop of Henle; dev_TUB, developing tubule; DN, distal nephron; POD, podocyte; dev_POD, developing podocyte; PIM, posterior intermediate mesoderm; NM, nascent mesoderm; ST, stromal cell; NEU, neural cell; MEL, melanocyte; MUS, muscle cell; prolif, proliferating cell; unknown, undefined type of cell. (C) UMAP plots of gene expression of the merged kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset. Left plot shows each organoid cell type cluster. Right plot shows origin of time point during differentiation. (D) Coverage plots showing ATAC peaks around transcription start site and gene expression levels of SLC3A1 (PT), SLC12A1 (LOH), GATA3 (DN), and NPHS2 (POD) genes in each cluster of the merged kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset. (E) Heatmap showing Pearson’s correlation coefficient between gene expression and gene activity of each cluster in nephron-lineage cells of the merged kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset. (F) Heatmap showing gene expression levels (Left) and motif enrichment in ATAC peaks (Right) of top-listed transcription factors in nephron-lineage cells of the merged kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset.

To identify critical regulators of cell fate during organoid differentiation, we calculated RNA expression and motif enrichment in open chromatin to compile a list of transcription factors (TFs) regulating each cell state (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Table S3). Many TFs enriched in organoids are also expressed in developing mouse kidneys where they are known to regulate nephrogenesis. For example, HNF4A and HNF1B are required for PT differentiation and maturation (44–48); TFAP2B is essential for DN differentiation (49); WT1 and MAFB regulate POD differentiation and slit diaphragm formation, respectively (50–53). Furthermore, TCF4 was up-regulated and its motif was enriched in the DN cluster, suggesting high WNT signaling activity in distal nephron, which is consistent with the previous reported WNT/ β-catenin gradient in the developing mouse and human kidneys (54). Yap/Taz has been reported to be important for the maintenance of glomerular filtration barrier integrity in mouse podocytes (55, 56). We detected strong gene expression and motif enrichment of TEAD3 and TEAD4 in podocytes of human kidney organoids, suggesting the possibility that Hippo pathway signaling plays an important function in human podocyte differentiation. Thus, our multiomic profiling revealed the cell type-specific landscape of gene expression and chromatin accessibility, allowing the prioritization of top-regulatory TFs during human kidney organoid differentiation.

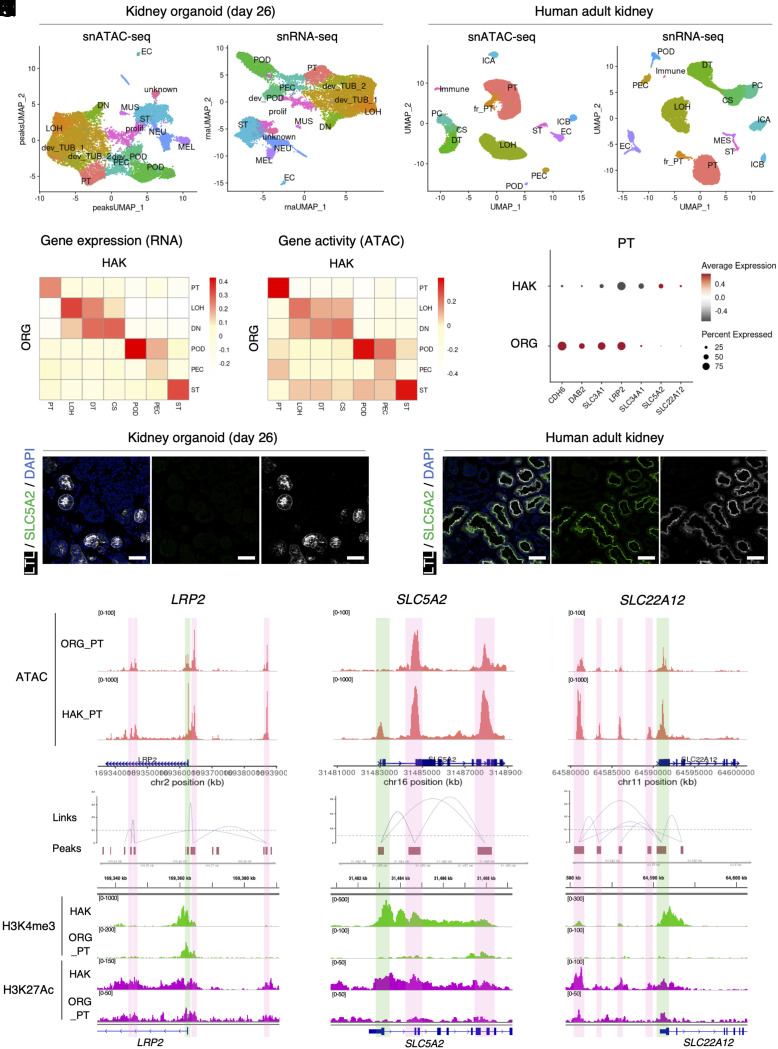

Comparing Kidney Organoid Epigenetic Features with Human Adult Kidneys.

We next compared day 26 kidney organoids with human adult kidney multiomic datasets (10) to evaluate differences in chromatin accessibility in each cell type (Fig. 1A). The HAK dataset included POD, PT, and LOH cell types but also distal tubules (DT) (SLC12A3+/CALB1+), which were not present in the organoids (Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). HAK also had principal cells (PCs) and intercalated cell type A (ICA) and type B (ICB), which are derived from anterior intermediate mesoderm but not PIM. Each cell type in the HAK expressed appropriate marker genes with corresponding gene activity calculated from the snATAC-seq datasets (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Gene activities in organoids were much less cell specific compared to those in HAK (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). A closer examination of chromatin accessibility peaks for marker genes revealed that the organoid cell types had relatively cell-specific peaks near to promoter regions but low cell-type specificity across the rest of the gene body (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Since gene activity scores reflect the summation of peaks across the whole gene body, this may explain why gene activity scores had lower cell specificity compared to RNA expression in organoid cell types (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). When we comprehensively compared gene expression and gene activity between organoids and HAK parenchymal cell types, POD, PT, and ST showed a high correlation in both modalities (Fig. 2 C and D). In contrast, gene expression and gene activity of LOH and DN in organoids showed broad similarity to LOH, DT, and CS in HAK without strong cell type-specific correlation. These results suggest that organoid distal nephron cell types are less differentiated than more proximal cell types.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of kidney organoid and human adult kidney chromatin accessibility landscapes. (A) UMAP plots of chromatin-accessible peak (Left) and gene expression (Right) of the day 26 kidney organoid multiome dataset. PT, proximal tubule; LOH, loop of Henle; dev_TUB, developing tubule; DN, distal nephron; POD, podocyte; dev_POD, developing podocyte; PEC, parietal epithelial cells in the glomerulus, EC, endothelial cell; ST, stromal cell; NEU, neural cell; MEL, melanocyte; MUS, muscle cell; prolif, proliferating cell; unknown, undefined type of cell. (B) UMAP plots of chromatin-accessible peak (Left) and gene expression (Right) of the merged human adult kidney multiome dataset. fr-PT, failed repaired proximal tubule; DT, distal tubule; CS, connecting segment, PC, principal cell; ICA, intercalated cell type A; ICB, intercalated cell type B; Immune, immune cell. (C and D) Heatmaps showing correlation between nephron-lineage cells of human adult kidney and kidney organoid (day 26) gene expression (C) and gene activity (D) modalities. (E) Dot plot showing expression levels of representative developing and mature proximal tubule marker genes in the proximal tubule cluster of human adult kidney and kidney organoid (day 26). (F and G) Immunofluorescence images of SLC5A2 (green, SGLT2), LTL (white), and nuclear DAPI (blue) staining in the proximal tubule of kidney organoids (day 26) (F) and human adult kidney (G). (Scale bars indicate 50 µm). (H–J) Coverage plots showing ATAC peaks and gene expression level in proximal tubule of human adult kidney and kidney organoid (day 26) (Upper) and peaks and peak-to-gene links (Lower) of LRP2 (H), SLC5A2 (I), and SLC22A12 (J) genes. Green boxes indicate promoter regions; pink boxes indicate putative enhancer regions. (K–M) Corresponding integrative genomics viewer (IGV) images showing target sites of H3K4me3 (promoter, upper) and H3K27Ac (enhancer and promoter, lower) antibodies in CUT&RUN sequencing with human adult kidney (HAK) and organoid-derived proximal tubule (ORG_PT) (lower) of LRP2 (K), SLC5A2 (L), and SLC22A12 (M) genes.

Next, we compared representative marker gene expression and chromatin accessibility patterns between organoid and HAK PT. Organoid PT expressed the developmental PT marker CDH6, whereas this gene was down-regulated in PT from HAK. Typical PT markers such as LRP2 and SLC3A1 were also detectable in organoid PT at higher levels than those in HAK PT. Other transport-related genes responsible for reabsorption of glucose (SLC5A2, encoding SGLT2) and uric acid (SLC22A12, encoding URAT1) were not detected in organoid PT compared to HAK PT (Fig. 2 E–G and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Analysis of chromatin accessibility for LRP2 revealed that both organoid and HAK PT showed similar peak patterns near the TSS, intronic, and intergenic regions (Fig. 2H). Some peaks with high cis-regulatory link scores calculated by the LinkPeak function (57) are candidate cis-regulatory elements. By contrast, SLC5A2 entirely lacked promoter accessibility in the organoid PT, while other peaks in the gene body were concordant with HAK (Fig. 2I). A third pattern emerged for the SLC22A12 gene, where the TSS peaks were similar between organoid and HAK, but the organoid PT lacked most of the upstream putative enhancer peaks (Fig. 2J), suggesting that multiple different epigenetic mechanisms underlie the low expression of PT genes in organoids.

To further annotate the gene regulatory landscape of organoids compared to HAK, we next performed cleavage under targets and release using nuclease (CUT&RUN) sequencing (58, 59) using histone modification antibodies with organoid-derived, cell-sorted PT and bulk HAK. This revealed a similar pattern: For PT-associated genes that were highly expressed in organoids, H3K4me3 peaks, which mark active promoters (60), were appropriately detected at the TSS both in bulk HAK and organoid PT (Fig. 2K). But for genes such as SLC5A2 and SLC22A12 that were poorly expressed in organoid PT, there was a corresponding lack of H3K4me3 at their respective TSSs (Fig. 2 L and M). Similarly, H3K27Ac peaks, which mark active enhancers and promoters (61, 62), were detected at the putative enhancer regions of LRP2 in both HAK and organoid PT, but absent in the organoid PT at SLC22A12 putative enhancer regions. These histone biochemical annotations validated the functional features of chromatin-accessible peaks detected in our multiome analysis.

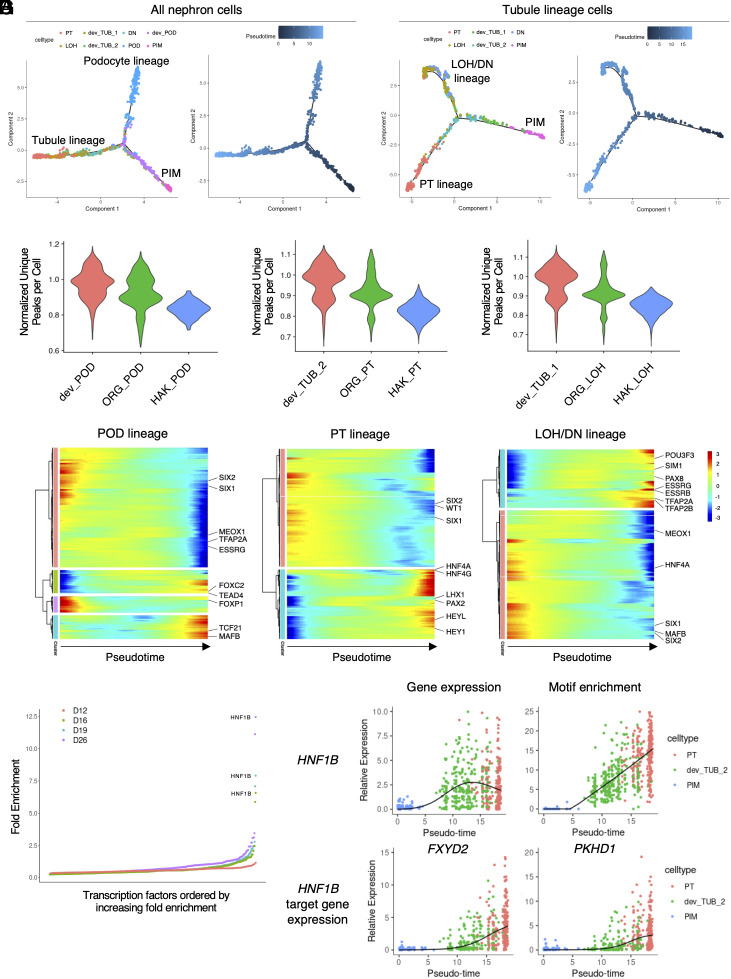

Gene Regulatory Dynamics during Kidney Organoid Differentiation.

Next, we examined cell-specific motif enrichment changes during nephron epithelial lineage differentiation. We subset nephron-lineage cells from the organoid differentiation dataset and created a pseudotime trajectory using Monocle 2. The nephron-lineage trajectory showed two major branches: PIM to POD and PIM to renal tubule (TUB) lineages (Fig. 3A). A subanalysis of the TUB lineage cells revealed a further divergence into PT and LOH/DN lineages (Fig. 3B). These findings are reminiscent of previously reported human fetal nephron trajectories (63). We overlayed sample timepoint with corresponding pseudotime trajectories (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A and B). We next asked how global chromatin accessibility differed between developing and differentiated organoid podocytes and tubule cell types, in comparison to their HAK counterparts. This revealed a clear pattern whereby the developing organoid POD, PT, and LOH had the most unique peaks per cell, with reduced peaks per cell in the more differentiated organoid cell types. However, in comparison to the HAK cell types, all the three organoid cell types had substantially more chromatin accessibility (Fig. 3C). This is consistent with broad chromatin accessibility in organoid cell types (SI Appendix, Figs. S6–S8) compared to HAK and likely reflects organoid cell immaturity in comparison to their adult kidney counterparts.

Fig. 3.

Gene regulatory dynamics during kidney organoid differentiation. (A) Pseudotime ordering plots of nephron-lineage cells using snRNA-seq modality showing podocyte and tubule-lineage branches. Colors are based on cell type (Left) and pseudotime (Right). (B) Subordering plots of tubule-lineage cells along pseudotime showing PT and LOH/DN lineage branches. Colors are based on cell type (Left) and pseudotime (Right). (C) Violin plots of number of unique peaks per cell, normalized for read depth, in differentiating (red) and differentiated (green) podocytes (POD, Left), proximal tubules (PT, Middle), and loop of Henle (LOH, Right) of day 26 kidney organoids and those of human adult kidneys (blue). (D) Heatmaps showing motif enrichment changes along pseudotime of podocyte (POD, Left), proximal tubule (PT, Middle), and loop of Henle and distal nephron (LOH/DN, Right) lineages. (E) Transcription factor enrichment in the PT lineage cells at each time point. (F and G) Dynamics of gene expression (F, Left) and motif enrichment (F, Right) of the HNF1B gene and their target gene expression changes (G) along pseudotime.

Across all organoid cell lineages, motif enrichment changes across pseudotime showed two contrasting patterns: low to high and high to low (Fig. 3D). The top-regulating TF motifs (Fig. 1F) showed low-to-high patterns in each cell lineage along pseudotime, e.g., MAFB and TCF21 in the POD lineage; HNF4A and HNF4G in the PT lineage; and ESRRG and TFAP2A in the LOH/DN lineage (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, upregulation of Notch pathway-related motifs, including HEY1 and HEYL, was also observed during later time points of the PT lineage, supporting previous findings implicating the Notch pathway in PT specification (64–66). By contrast, high-to-low pattern motifs included nephron progenitor-related genes such as SIX1, SIX2, and MEOX1. Motifs related to distal nephron-related genes such as TFAP2A and ESRRG were reduced in the POD lineage, and those of MAFB and HNF4A were reduced in the LOD/DN lineage. These results indicate that organoid cell types gradually lose accessibility for progenitor-related TFs while acquiring accessibility for cell type-specific TFs during differentiation.

We next focused on the top-regulatory TFs in PT and POD cell types, HNF1B and MAFB, respectively (Fig. 1F). Comprehensive analysis of TF enrichment in the PT lineage cells revealed HNF1B as the top-enriched TF during PT differentiation after day 16 (Fig. 3E). Along PT differentiation pseudotime, HNF1B expression changes varied with enrichment of its corresponding motifs (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, changes in the transcription of FXYD2 and PKHD1, target genes of HNF1B (67–69), were concordant with HNF1B motif enrichment changes (Fig. 3G). Similarly, MAFB gene expression and motif enrichment changes varied with MAGI2 and NPHS1 expression changes (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 C and D), target genes of MAFB (70). These results demonstrate the utility of single-cell multiomic analysis of kidney organoid differentiation to reveal cell type differentiation-associated gene regulatory dynamics.

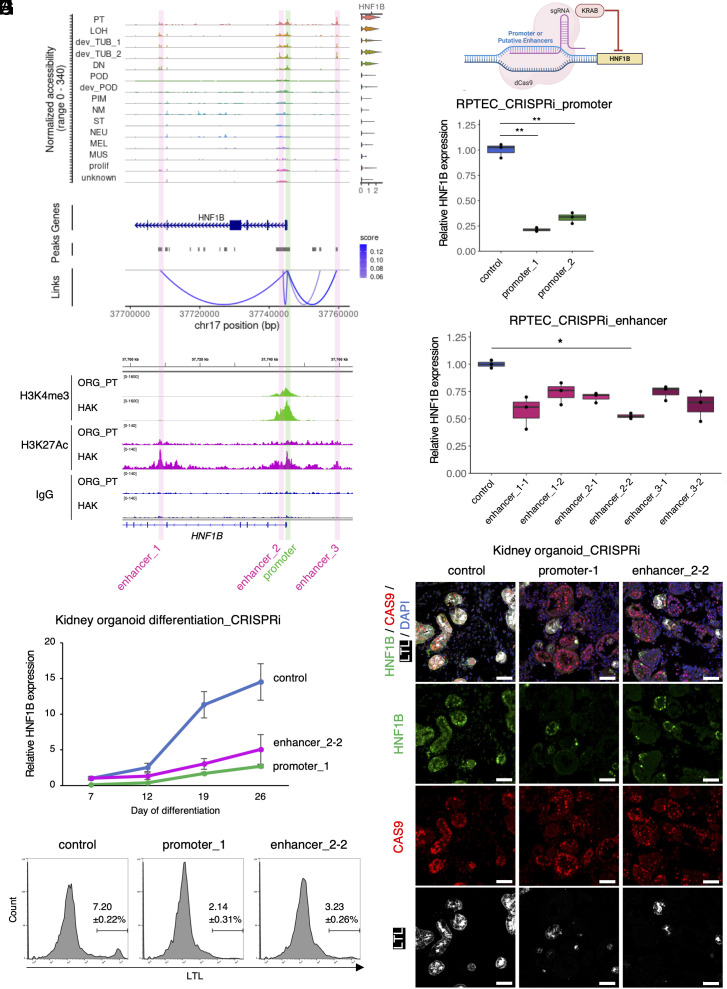

Interference of the Gene Regulatory Network of HNF1B Inhibited PT Differentiation.

We next asked whether we could predict the genomic regulatory features for HNF1B, a transcription factor known to be important for PT and LOH differentiation (29, 46–48, 71). We identified three accessible chromatin peaks with high cis-regulatory link scores to HNF1B as putative enhancers (Fig. 4A). CUT&RUN with anti-H3K27Ac antibody using kidney organoid-derived PT and HAK corroborated that these peaks are potential enhancers regulating HNF1B expression (Fig. 4B). These three peaks also correlated with elevated HNF1B gene expression during organoid differentiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). To validate the functional contribution of these peaks for gene expression, we epigenetically repressed each promoter and enhancer of HNF1B using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) employing inactive CRISPR enzyme (dCAS9) fused to the KRAB repressor domain (Fig. 4C) (72). In cultured human primary renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTEC), CRISPRi with guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the promoter region of HNF1B resulted in a 70 to 80% reduction of HNF1B expression (Fig. 4D). The gRNAs targeting enhancer_2 reduced expression of HNF1B by 30 to 50%, whereas targeting of enhancer_1 or enhancer_3 reduced HNF1B expression by 20 to 40% (Fig. 4E). Bulk ATAC-seq confirmed that the chromatin accessibilities of the gRNA target regions were specifically closed after CRISPRi (Fig. S12). These results indicate that all the three potential enhancers regulate HNF1B expression in RPTEC.

Fig. 4.

Interference of the gene regulatory network of HNF1B inhibited PT differentiation. (A) Coverage plots showing ATAC peaks and gene expression level of HNF1B gene of the merged kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset. Green box indicates promoter region; pink boxes indicate putative enhancer regions. (B) Corresponding integrative genomics viewer (IGV) images showing target sites of H3K4me3 (promoter, Upper), H3K27Ac (enhancer and promoter, Lower), and IgG (negative control) antibodies in CUT&RUN sequencing with day 26 organoid-derived proximal tubule (ORG_PT) and human adult kidney (HAK). (C) Schematic of HNF1B CRISPRi experiment. (D and E) qRT-PCR results of human primary RPTEC with CRISPRi for targeting promoter (D) and putative enhancer (E) regions of HNF1B. n = 3 biological replicates. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. (F) qRT-PCR results of kidney organoid differentiation time course with CRISPRi targeting promoter and enhancer_2 regions of HNF1B. Control samples were treated with a dCAS9-KRAB vector without sgRNA. n = 4 biological replicates. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. (G) Immunofluorescence images of HNF1B (green), LTL (white), CAS9 (red), and nuclear DAPI (blue) staining in kidney organoids (day 26) with CRISPRi for HNF1B using control vector (dCAS9-KRAB without sgRNA, Left), sgRNA targeting promoter (Middle), and sgRNA targeting enhancer_2 (Right). (Scale bars indicate 50 µm). (H) Flow cytometry analyses showing LTL-positive cell proportions of kidney organoid (day 26) with CRISPRi for HNF1B using control vector (dCAS9-KRAB without sgRNA, Left), sgRNA targeting promoter (Middle), and sgRNA targeting enhancer_2 (Right). n = 4 biological replicates. The data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Next, we examined the functional consequences of modifying HNF1B epigenetic regulation during organoid differentiation. We generated hiPSC clones by stably transducing a lentiviral CRISPRi plasmid (dCAS9-KRAB) with gRNAs targeting either promoter_1 or enhancer_2-2 of HNF1B, and then induced kidney organoids. From day 12 to day 19, control organoids transduced with dCAS9-KRAB plasmid without gRNA substantially up-regulated HNF1B expression, whereas CRISPRi organoids targeting both promoter_1 and enhancer_2-2 suppressed HNF1B expression (Fig. 4F). At day 26, CRISPRi organoids targeting the promoter region caused >80% reduction and the enhancer_2 region caused a 65% reduction in HNF1B expression (Fig. 4F). Notably, the resultant CRISPRi organoids contained fewer LTL+ PT and SLC12A1+ LOH together with reduced nuclear HNF1B expression and presence of CAS9 protein (Fig. 4 G and H, and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). These results indicate that the potential enhancers of HNF1B identified by our multiome analysis do regulate HNF1B expression and functionally contribute to PT and LOH differentiation during human kidney organoid differentiation. These results validate kidney organoids as a valuable tool for investigating gene regulatory mechanisms during human nephrogenesis.

Discussion

A major challenge to studying the mechanisms that regulate human kidney development is the difficulty of obtaining tissue across developmental stages and the lack of methods to systematically interrogate transcriptional and epigenetic dynamics over time. Here, we integrated single-cell transcriptome and chromatin accessibility during kidney organoid development in order to provide insight into the mechanisms driving kidney cell differentiation. We find that among the kidney cells represented in organoids, there is broad conservation of cellular differentiation programs in kidney organoids when compared to HAK. Organoid cell types were immature compared to adult, as expected, with distal nephron cell types being more immature than proximal in this differentiation protocol.

We observed increased global chromatin accessibility in tubular progenitors, and with maturation, reduced chromatin accessibility. However, HAK had even less global chromatin accessibility, most likely reflecting a lack of full differentiation in organoids compared to HAK. When we focused on organoid PT, we could define several different patterns of transcription, chromatin accessibility, and histone modification. For highly expressed organoid PT genes such as LRP2, chromatin accessibility and H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac marks were all concordant with HAK. But for other PT genes that were not expressed in organoid, some genes such as SLC5A2 had accessible enhancer regions but inaccessible promoter regions, with variable histone mark concordance. By contrast, SLC22A12 transcription was also absent in organoid PT, but had accessible promoter chromatin, but not accessible chromatin at putative enhancers when compared to HAK. Taken together, these results paint a complex picture regarding the gene regulatory landscape in organoid cell types. For highly expressed genes, at least, the fact that transcription, chromatin accessibility, and histone marks closely mirror that of HAK indicates that organoids can accurately model complex gene regulatory networks present in mature kidney. Our data validate the use of human kidney organoids to investigate both normal developmental pathways and how pathogenic mutations leading to CAKUT or adult kidney disorders alter cell differentiation and/or cell function.

As validation of our gene regulatory network predictions, we targeted a putative enhancer of HNF1B using CRISPRi during organoid differentiation. This resulted in decreased HNF1B transcription and impaired PT and LOH differentiation. This result provides a proof of principle for the utility of kidney organoid models to study and decipher the gene regulatory mechanisms controlling kidney development.

There are limitations to our study. First, we compared kidney organoid and human adult kidney single-cell multiomes. Multiomic analysis of human fetal kidneys, although difficult to obtain, will allow for a more precise characterization of the epigenetic status of kidney organoids since kidney organoids most closely resemble fetal kidneys (20, 27, 41, 73). Such an analysis could resolve whether the differences in epigenetic status we observe reflect either discrete developmental states that normally occur during nephrogenesis vs. chromatin accessibility profiles unique to organoid differentiation in vitro and not seen in vivo. Second, we chose a differentiation protocol that in our hands is robust and reproducible, but it does not generate collecting duct cell types and had few endothelial cells. Application of the kind of multiomic analysis performed here on recent protocol improvements will be promising (32). Finally, we validated a single predicted enhancer for the HNF1B gene by CRISPRi. Recent advances allow for organoid perturbation screens ranging from dozens of targets to genome wide and these also hold promise (5, 74).

In summary, our study provides a comprehensive investigation of the single-cell gene regulatory landscape during kidney organoid differentiation. We expect that joint single-cell transcriptome and chromatin accessibility datasets will be useful to infer and perturb cell regulatory networks governing kidney cell differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

BJFF.6 and AN1.1 human iPSC lines were obtained from the Genome Engineering & Stem Cell Center at McDonnell Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. The BJFF.6 and AN1.1 lines were reprogrammed from a neonatal foreskin-derived fibroblast sample and a urine sample, respectively, with informed consent from all donors. The H9 human ESC line was obtained from WiCell. The use of all these cell lines has been approved by the Washington University Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight (ESCRO) committee. All experiments were approved by an established Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol approved by Washington University in St. Louis. All PSCs were maintained and expanded in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C in StemFlex medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A3349401) on matrigel (Corning, 354277)-coated plate with daily media changes. Cells were passaged every 3 to 4 d by treatment with ReLeSR (STEMCELL Technologies, 05872). The cells were confirmed to be karyotypically normal and Mycoplasma free. Experiments were performed below passage 50. 293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3246) were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11965092) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10437028), 1× GlutaMAX supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 35050061), and 1× penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122). Human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTECs; Lonza, CC-2553) were cultured with renal epithelial cell growth medium (Lonza, CC-3190) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. 293T cells and RPTECs were passaged by treatment with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 25300054). Experiments were performed on early passages.

Human Samples.

Nontumor human kidney cortex sample was obtained from a 71-y-old female donor (serum Cr 0.60 mg/dl) from the MTS with informed consent. The participant provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Samples were frozen or retained in paraffin blocks for future studies. Histologic sections were reviewed by a renal pathologist and laboratory data were abstracted from the medical record. All experiments were approved by an established IRB protocol approved by Washington University in St. Louis.

Kidney Organoid Induction.

Kidney organoids were generated by Takasato protocol (43) with slight modifications. Briefly, on the next day of passage, PSCs were treated with 8 µM CHIR99021 (TOCRIS, 4423) in basal medium that comprised APEL2 (STEMCELL Technologies, 05275) supplemented with 1.5% Protein-Free Hybridoma Medium II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12040077) and 1× antibiotic–antimycotic solution (Corning, 30-004-CI) for 4 d. On day 4, the medium was switched to 200 ng/mL FGF9 (R&D Systems, 273-F9-025) and 1 μg/mL heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, H4784) in the basal medium. On day 7, cells were dissociated into single cells using Accutase (Sigma-Aldrich, SF006) and diluted five-fold with the basal medium with 10 µM Y27632 (TOCRIS, 1254). 2 × 105 cells were spun down at 300 g for 2 min (twice with 180° flip) to make cell aggregates in a low cell–binding tube (VWR, 490003-230) and transferred onto a 0.4-µm pore polyester membrane transwell (Corning, 3460). Pellets were incubated with 5 µM CHIR99021 in the basal medium for 1 h, and then cultured with 200 ng/mL FGF9 and 1 µg/mL heparin in the basal medium for 5 d. From day 12 to days 26 to 28, organoids were grown in the basal medium. The medium were changed every other day.

Nuclei Isolation from Differentiating Kidney Organoids and Library Preparation for Multiome Analysis.

To dissociate organoids into single cells, days 12, 16, 19, and 26 organoids were treated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 25200056) at 37 °C for 8-10 min. Day 7 posterior intermediate cells were treated with Accutase at 37 °C for 6 min to obtain single cells. Dissociated cells were washed with FACS wash buffer and filtered through a 40-µm strainer (pluriSelect, 43-50040-51). 1 × 106 cells were treated with chilled multiome lysis buffer on ice for 5 min to obtain nuclei. The isolated nuclei were washed with multiome wash buffer for a total of three times, then resuspended with chilled multiome nuclei buffer. After nuclei preparation, single-cell libraries were prepared using Chromium Next GEM Single-Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression kit (10X Genomics) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Kidney Organoid Multiome Data Processing.

Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq instrument. Raw sequencing data were converted into FASTQ files using cellranger-arc mkfastq (v2.0). The FASTQ files were then aligned to the GRCh38 (hg38) reference genome and quantified using cellranger-arc count (v2.0.0). Following sequencing, quality control (QC) was performed on each RNA and ATAC modalities (SI Appendix, Table S1). The overall quality of control matrices was high, including molecular counts of each assay, nucleosome signal score, and TSS enrichment scores. We noticed a high percentage of mitochondria in all multiome datasets, which was also observed in the 10× Genomics PBMC multiome dataset using the same nuclei isolation protocol. We reasoned that this was probably due to gentle nuclei isolation treatment, which allowed mitochondria to be attached to the nuclei, and the transposition treatment at 37 °C for 60 min prior to GEM generation. We filtered out low-quality cells and multiplets that showed abnormal QC scores in each dataset (SI Appendix, Table S2). The DoubletFinder R package was further used to eliminate cells estimated to be doublets or multiplets. These preprocessing created multiome datasets consisting of quality-assured singlets (SI Appendix, Table S2). Singlet datasets of each time point from different PSC clones were merged and subjected to batch effect correction for RNA and ATAC assays using the RunHarmony function in Seurat R package (v.4.1.0). Subsequently, these merged datasets for each time point were then aggregated together to generate an organoid differentiation multiome atlas. This resulted in 56,865 cells after filtering. For a comparison to human adult kidney, we used a merged and batch-corrected day 26 organoid dataset.

Gene Expression Data Preprocessing and Cell Annotation.

We normalized gene expression UMI count data using SCTransform with regressing out percentage of mitochondrial reads (percent.mt) and read count (nCount_RNA) in each cell and performed dimensionality reduction by PCA and UMAP embedding (“dim = 1:50”) with RunPCA and RunUMAP functions, respectively. Individual clusters were annotated based on the expression of lineage-specific markers (SI Appendix, Table S2). Differentially expressed genes among cell types were assessed with the FindMarkers function (Seurat) for transcripts detected in at least 10% of cells using a log-fold-change threshold of 0.25. Bonferroni-adjusted p-values were used to determine significance at an FDR < 0.05.

DNA Accessibility Data Processing.

ATAC-seq peaks in the dataset were identified on all cells together using MACS2 (75) with the default parameters of Signac’s (v1.5.0) CallPeaks function: --gsize 2.7e9 --nomodel False --shift -100 --extsize 200 --d-min 20 --qvalue 0.05 --broad False (57). After removing peaks in nonstandard chromosomes and genomic blacklist regions for the hg38 genome, we quantified counts for the resulting peak set for each cell using the FeatureMatrix function in Signac. A gene activity matrix was constructed by counting ATAC peaks within the gene body and promoter region 2 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site using protein-coding genes annotated in the Ensembl database. The DNA accessibility dataset was then normalized with term-frequency inverse-document-frequency (TFIDF) and was subjected to dimensional reduction by singular value decomposition (SVD) of the TFIDF matrix and UMAP embedding (“dim = 2:50”) with RunSVD and RunUMAP functions (Signac). We normalized the number of unique peaks in each cell for read depth by dividing by each cell’s cellranger-computed atac_peak_region_fragments metric so that we could compare the number of unique peaks along PT, LOH, and POD differentiation trajectories in day 26 organoid and human adult kidney datasets.

Correlation of Gene Expression and Gene Activity in Each Nephron Cell Type in the Differentiating Kidney Organoid.

We subset nephron epithelial cells from the kidney organoid differentiation multiome dataset and scaled in each gene expression and gene activity assay. The average gene expression and gene activity values were obtained in each cluster. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated among 18,353 genes commonly detected in gene expression and gene activity assays.

Motif Enrichment and Identification of Key Transcription Factors in Each Cell Type.

Cell type-specific motif enrichment was determined by calculating a per-cell accessibility score for known motifs in the accessible regions of each cell using the chromVAR package with cisBP motif collections (“human_pwms_v2”) and the RunChromVAR function in Signac. To identify key transcription factors (TFs) regulating each cell state, we used the presto package to calculate P-values based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for TFs that yielded significant values for both gene expression data and ChromVAR motif accessibility tests. We then calculated an “AUC” statistic and ranked the TFs for each cell type by taking the average of the AUC values from the two tests. We also used the motif activity scores calculated with chromVAR in order to identify active transcription factors in the PT lineage at each time point. To do this, we computed the average fold change difference in motif activity z-scores for each time point relative to the full dataset with Seurat’s FindMarkers function. We then ranked each TF passing FindMarkers’ default filters at each time point by fold enrichment for plotting.

Peak-to-Gene Linkage.

Linkage scores for each peak–gene pair were calculated using the LinkPeaks function with default settings in Signac (57). Briefly, the set of peaks that may regulate each gene was detected by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients between gene expression and accessibility at peaks within 500 kb of each gene TSS and correcting for bias due to GC content, overall accessibility, and peak size. Significant links were retained above a P-value cutoff of 0.05 and a score cutoff of 0.05 and if the gene and open peak were present in at least 10 cells.

Construction of Pseudotemporal Trajectories.

We used Monocle2 (v2.20.0) (76) to generate pseudotemporal trajectories during nephron epithelial differentiation as described in our previous paper (40). Briefly, we randomly picked equal number of cells from eight types of nephron-lineage clusters. The ordering genes were selected using a semi-supervised approach as follows: They are putatively reported as markers for the kidney developmental state or terminally kidney cell fate; they are specific marker genes differentially expressed in the clusters. We used them to select the ordering genes that covary with these markers using the Monocle function markerDiffTable. We then reduced the data space to two dimensions with DDRTree method and ordered the cells based on their gene expression profiles using the orderCells function. Individual cells were color-coded based on the cell type identity, the collected time points, and pseudotime when the starting state is set as day 7. The trajectory only for tubule lineage was generated in a similar manner using the six types of tubule-lineage clusters.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Details of sample size for each experiment were provided in the figure legends. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test was used for two-group comparison. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer test was used for multiple group comparison. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Experiments were not randomized, and investigators were not blinded to allocation during library preparation, experiments, or analysis.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Humphreys lab for helpful discussions, and the Genome Technology Access Center and the Genome Engineering & Stem Cell Center at the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University School of Medicine for helping in genomic analysis and providing pluripotent stem cell lines, respectively. This work was funded by seed network grant CZF2019-002430 from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (to B.D.H.). Additional support was from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Overseas Research Fellowships and the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to Y.Y.). B.D.H. holds grant funding from Pfizer.

Author contributions

Y.Y. and B.D.H. designed research; Y.Y., Y.M., N.L., H.W., K.O., J.H.M., and B.D.H. performed research; Y.Y., Y.M., N.L., H.W., K.O., J.H.M., and B.D.H. analyzed data; and Y.Y. and B.D.H. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

B.D.H. is a consultant for Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Pfizer, and Chinook Therapeutics and holds equity in Chinook Therapeutics.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The accession number for sn-multiome and CUT&RUN sequencing datasets in this paper is GEO: GSE213152 (77), and that for bulk ATAC-seq dataset is GEO: GSE227061 (78). Previously published sn-multiome data for human adult kidneys are available in GEO: GSE151302 (79). All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Cockwell P., Fisher L.-A., The global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet 395, 662–664 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao J., et al. , Joint profiling of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in thousands of single cells. Science 361, 1380–1385 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuart T., et al. , Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888–1902.e21 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allaway K. C., et al. , Genetic and epigenetic coordination of cortical interneuron development. Nature 597, 693–697 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleck J. S., et al. , Inferring and perturbing cell fate regulomes in human brain organoids. Nature 1–8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevino A. E., et al. , Chromatin and gene-regulatory dynamics of the developing human cerebral cortex at single-cell resolution. Cell 184, 5053–5069.e23 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziffra R. S., et al. , Single-cell epigenomics reveals mechanisms of human cortical development. Nature 598, 205–213 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gegenhuber B., Wu M. V., Bronstein R., Tollkuhn J., Gene regulation by gonadal hormone receptors underlies brain sex differences. Nature 606, 153–159 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miao Z., et al. , Single cell regulatory landscape of the mouse kidney highlights cellular differentiation programs and disease targets. Nat. Commun. 12, 2277 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muto Y., et al. , Single cell transcriptional and chromatin accessibility profiling redefine cellular heterogeneity in the adult human kidney. Nat. Commun. 12, 2190 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilliard S., Tortelote G., Liu H., Chen C.-H., El-Dahr S. S., Single-cell chromatin and gene-regulatory dynamics of mouse nephron progenitors. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 33, 1308–1322 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hao Y., et al. , Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587.e29 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gur C., et al. , LGR5 expressing skin fibroblasts define a major cellular hub perturbed in scleroderma. Cell 185, 1373–1388.e20 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taubenschmid-Stowers J., et al. , 8C-like cells capture the human zygotic genome activation program in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 29, 449–459.e6 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman B. S., et al. , Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nat. Commun. 6, 8715 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruz N. M., et al. , Organoid cystogenesis reveals a critical role of microenvironment in human polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Mater. 16, 1112–1119 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanigawa S., et al. , Organoids from nephrotic disease-derived iPSCs identify impaired NEPHRIN localization and slit diaphragm formation in kidney podocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 11, 727–740 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hale L. J., et al. , 3D organoid-derived human glomeruli for personalised podocyte disease modelling and drug screening. Nat. Commun. 9, 5167 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forbes T. A., et al. , Patient-iPSC-derived kidney organoids show functional validation of a ciliopathic renal phenotype and reveal underlying pathogenetic mechanisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 816–831 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran T., et al. , In vivo developmental trajectories of human podocyte inform in vitro differentiation of pluripotent stem cell-derived podocytes. Dev. Cell 50, 102–116.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuraoka S., et al. , PKD1-dependent renal cystogenesis in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived ureteric Bud/collecting duct organoids. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 31, 2355–2371 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimizu T., et al. , A novel ADPKD model using kidney organoids derived from disease-specific human iPSCs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 529, 1186–1194 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu E., et al. , Profiling APOL1 nephropathy risk variants in genome-edited kidney organoids with single-cell transcriptomics. Kidney360 1, 203–215 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruz N. M., et al. , Modelling ciliopathy phenotypes in human tissues derived from pluripotent stem cells with genetically ablated cilia. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 463–475 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta N., et al. , Modeling injury and repair in kidney organoids reveals that homologous recombination governs tubular intrinsic repair. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabj4772 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taguchi A., et al. , Redefining the in vivo origin of metanephric nephron progenitors enables generation of complex kidney structures from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 14, 53–67 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takasato M., et al. , Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature 526, 564–568 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morizane R., et al. , Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 1193–1200 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Przepiorski A., et al. , A simple bioreactor-based method to generate kidney organoids from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 11, 470–484 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low J. H., et al. , Generation of human PSC-derived kidney organoids with patterned nephron segments and a de novo vascular network. Cell Stem Cell 25, 373–387.e9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimura Y., et al. , Manipulation of nephron-patterning signals enables selective induction of podocytes from human pluripotent stem cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 30, 304–321 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanslambrouck J. M., et al. , Enhanced metanephric specification to functional proximal tubule enables toxicity screening and infectious disease modelling in kidney organoids. Nat. Commun. 13, 5943 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanigawa S., et al. , Generation of the organotypic kidney structure by integrating pluripotent stem cell-derived renal stroma. Nat. Commun. 13, 611 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taguchi A., Nishinakamura R., Higher-order kidney organogenesis from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 21, 730–746.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uchimura K., Wu H., Yoshimura Y., Humphreys B. D., Human pluripotent stem cell-derived kidney organoids with improved collecting duct maturation and injury modeling. Cell Rep. 33, 108514 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mae S.-I., et al. , Expansion of human iPSC-derived ureteric bud organoids with repeated branching potential. Cell Rep. 32, 107963 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howden S. E., et al. , Plasticity of distal nephron epithelia from human kidney organoids enables the induction of ureteric tip and stalk. Cell Stem Cell 28, 671–684.e6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng Z., et al. , Generation of patterned kidney organoids that recapitulate the adult kidney collecting duct system from expandable ureteric bud progenitors. Nat. Commun. 12, 3641 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi M., et al. , Human ureteric bud organoids recapitulate branching morphogenesis and differentiate into functional collecting duct cell types. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 252–261 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H., et al. , Comparative analysis and refinement of human PSC-derived kidney organoid differentiation with single-cell transcriptomics. Cell Stem Cell 23, 869–881.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Combes A. N., Zappia L., Er P. X., Oshlack A., Little M. H., Single-cell analysis reveals congruence between kidney organoids and human fetal kidney. Genome Med. 11, 3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phipson B., et al. , Evaluation of variability in human kidney organoids. Nat. Methods 16, 79–87 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takasato M., Er P. X., Chiu H. S., Little M. H., Generation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1681–1692 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marable S. S., Chung E., Adam M., Potter S. S., Park J.-S., Hnf4a deletion in the mouse kidney phenocopies Fanconi renotubular syndrome. JCI Insight 3, e97497 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marable S. S., Chung E., Park J.-S., Hnf4a is required for the development of Cdh6-expressing progenitors into proximal tubules in the mouse kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 31, 2543–2558 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heliot C., et al. , HNF1B controls proximal-intermediate nephron segment identity in vertebrates by regulating Notch signalling components and Irx1/2. Development 140, 873–885 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naylor R. W., Przepiorski A., Ren Q., Yu J., Davidson A. J., HNF1β is essential for nephron segmentation during nephrogenesis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 77–87 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massa F., et al. , Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β controls nephron tubular development. Development 140, 886–896 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marneros A. G., AP-2β/KCTD1 control distal nephron differentiation and protect against renal fibrosis. Dev. Cell 54, 348–366.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kreidberg J. A., et al. , WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell 74, 679–691 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kann M., et al. , Genome-wide analysis of wilms’ tumor 1-controlled gene expression in podocytes reveals key regulatory mechanisms. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 2097–2104 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadl V. S., et al. , The mouse kreisler (Krml1/MafB) segmentation gene is required for differentiation of glomerular visceral epithelial cells. Dev. Biol. 249, 16–29 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriguchi T., et al. , MafB is essential for renal development and F4/80 expression in macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 5715–5727 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindström N. O., et al. , Integrated β-catenin, BMP, PTEN, and Notch signalling patterns the nephron. Elife 4, e04000 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen J., Wang X., He Q., Harris R. C., TAZ is important for maintenance of the integrity of podocytes. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 322, F419–F428 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartzman M., et al. , Podocyte-specific deletion of yes-associated protein causes FSGS and progressive renal failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 216–226 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stuart T., Srivastava A., Madad S., Lareau C. A., Satija R., Single-cell chromatin state analysis with Signac. Nat. Methods 18, 1333–1341 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skene P. J., Henikoff S., An efficient targeted nuclease strategy for high-resolution mapping of DNA binding sites. Elife 6, e21856 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skene P. J., Henikoff J. G., Henikoff S., Targeted in situ genome-wide profiling with high efficiency for low cell numbers. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1006–1019 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barski A., et al. , High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129, 823–837 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Creyghton M. P., et al. , Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21931–21936 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rada-Iglesias A., et al. , A unique chromatin signature uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature 470, 279–283 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindström N. O., et al. , Progressive recruitment of mesenchymal progenitors reveals a time-dependent process of cell fate acquisition in mouse and human nephrogenesis. Dev. Cell 45, 651–660.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng H.-T., et al. , γ-Secretase activity is dispensable for mesenchyme-to-epithelium transition but required for podocyte and proximal tubule formation in developing mouse kidney. Development 130, 5031–5042 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng H.-T., et al. , Notch2, but not Notch1, is required for proximal fate acquisition in the mammalian nephron. Development 134, 801–811 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duvall K., et al. , Revisiting the role of Notch in nephron segmentation confirms a role for proximal fate selection during mouse and human nephrogenesis. Development 149, dev200446 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gresh L., et al. , A transcriptional network in polycystic kidney disease. EMBO J. 23, 1657–1668 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hiesberger T., et al. , Mutation of hepatocyte nuclear factor–1β inhibits Pkhd1 gene expression and produces renal cysts in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 814–825 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adalat S., et al. , HNF1B mutations associate with hypomagnesemia and renal magnesium wasting. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 1123–1131 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Usui T., et al. , Transcription factor MafB in podocytes protects against the development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 98, 391–403 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grand K., et al. , HNF1B alters an evolutionarily conserved nephrogenic program of target genes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 34, 412 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thakore P. I., et al. , Highly specific epigenome editing by CRISPR-Cas9 repressors for silencing of distal regulatory elements. Nat. Methods 12, 1143–1149 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garreta E., et al. , Fine tuning the extracellular environment accelerates the derivation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Mater. 18, 397–405 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ungricht R., et al. , Genome-wide screening in human kidney organoids identifies developmental and disease-related aspects of nephrogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 29, 160–175.e7 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Y., et al. , Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qiu X., et al. , Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. Methods 14, 979–982 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoshimura Y., Muto Y., Humphreys B., The gene regulatory landscape of kidney organoid differentiation revealed by single nucleus multiomic analyses. Gene Expression Omnibus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE213152. Deposited 12 September 2022.

- 78.Yoshimura Y., Muto Y., Humphreys B., Bulk ATAC-seq of RPTEC with HNF1B CRISPRi. Gene Expression Omnibus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE227061. Deposited 9 March 2023.

- 79.Muto Y., Wilson P., Humphreys B., Single Cell Transcriptional and Chromatin Accessibility Profiling on the human adult kidneys. Gene Expression Omnibus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE151302. Deposited 27 May 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The accession number for sn-multiome and CUT&RUN sequencing datasets in this paper is GEO: GSE213152 (77), and that for bulk ATAC-seq dataset is GEO: GSE227061 (78). Previously published sn-multiome data for human adult kidneys are available in GEO: GSE151302 (79). All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or SI Appendix.