Abstract

Objective

To describe and synthesise the content of public-facing websites regarding the use of diagnostic imaging for adults with lower back pain, knee, and shoulder pain.

Methods

Scoping review conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidance. A Google search was performed to identify public-facing websites that were either United Kingdom-based, or National Health Service affiliated. The DISCERN tool was used to appraise website quality before information regarding the use of imaging was synthesised using thematic analysis.

Results

Eighty-six websites were included, with 48 making reference to the use of imaging. The information within the majority (n = 43) of public-facing websites aligns with best available evidence. Where there is inconsistency, this may be explained by lower website quality. Three themes were apparent regarding the use of imaging – imaging to inform diagnosis and management; imaging in context; patient experience and expectations.

Conclusion

The recommendations and rationale for use of imaging contained within public-facing websites does not appear to justify the increase in imaging rates for musculoskeletal pain in the UK.

Innovation

Publicly available information following a novel search strategy, is largely aligned with best evidence, further understanding is required to determine reasons for requesting imaging from a patient and clinician perspective.

Keywords: Shoulder Pain, Low Back Pain, Knee Pain, Diagnostic Imaging, Public-facing websites

Highlights

-

•

Diagnostic imaging rates for musculoskeletal pain are increasing.

-

•

Co-produced search strategy to replicate the patient experience.

-

•

Public-facing websites for musculoskeletal pain largely align with evidence.

-

•

Further insight required to understand rationale behind increasing imaging use.

1. Introduction

One of the most common reasons for consultation in primary care is musculoskeletal pain [1]. The most common areas affected are the lower back (LBP), knee and shoulder respectively [1,2]. In many situations, there is considerable clinical uncertainty in relation to the diagnosis to which symptoms of pain and reduced function can be attributed. Diagnostic imaging is increasingly being requested by primary care clinicians including general practitioners, nurses and physiotherapists [[3], [4], [5],7], particularly where diagnostic uncertainty exists. It has also been reported that scan results are perceived by patients as authoritative [6].

It has been reported that in the five years between 2011/12 and 2016/17 there has been a 16% increase in the use of diagnostic imaging within the National Health Service (NHS) in England with the high demand from primary care being acknowledged as a challenge [7]. Within this challenge, patient expectations about diagnostic imaging have been suggested to be one factor that might explain the rise in imaging requests [7,8].

The NHS Long Term Plan [9] outlines how patients will have more control over their own health and more individualised care. To achieve this, the need for a fundamental shift in how clinicians work alongside patients is outlined, a model referred to as patient-centred care. Within a patient-centred care model, the encounter between the clinician and the patient is considered an equal encounter of negotiation whereby the patient is an active partner, with the patient-clinician relationship being one of interdependence through ‘shared decision making’ (SDM) [10]. This contrasts with a previously prevailing paternalistic relationship where the power sits with the clinician, and the patient is a passive recipient of care [11].

As of June 2019, 58.8% of the worldwide population have access to the internet [12]. It is suggested that 91% of adults in the United Kingdom (UK) use the internet [13] and that 73% use the internet as a source of healthcare information [14]. Increasing internet access, when combined with patient expectation as being a potential cause of increased use of diagnostic imaging within the NHS, needs to be considered within the wider context of a strategic prioritisation of individualised care informed by SDM. It is possible that the content within public-facing websites is informing patient expectations regarding the requirement for diagnostic imaging.

Despite the use of the internet for health information increasing, the quality of the information online remains varied [[15], [16], [17], [18]]. Within an environment of mixed information, it can be difficult for patients to identify a trustworthy source. Further compounding this is that many patients may not have the capability to appraise website content nor recognise the strengths, weaknesses or credibility of the information [19]. To date, studies have focused on the quality and readability of website content in relation to specific disease processes [20] or specific body sites [21]. There is an absence of research identifying, describing, and synthesising content of written healthcare information related to specific components of clinical delivery, such as diagnostic imaging, across disease processes and body sites. Such research would allow for similarities and differences in relation to information provided to be identified as well as understanding how the website content aligns with best available evidence. In doing so, it can be established whether any differences seen are justified or reflect unwarranted variation, as well as highlighting priority areas for future development or informing potential educational or organisational strategies or policy, aimed at reducing unnecessary diagnostic imaging use.

There is a clear need to understand what online information exists that is available to patients about diagnostic imaging for musculoskeletal pain conditions. This scoping review is the first step towards that understanding. The aim of this scoping review was to describe and synthesise the content of public-facing websites with respect to the use of diagnostic imaging for adults with LBP, knee, and shoulder pain.

1.1. Review objectives

-

•

To identify existing public-facing websites that may be used as sources of written healthcare information for people with LBP, knee, and shoulder pain.

-

•

To describe and summarise website written content in relation to the use of diagnostic imaging for LBP, knee, and shoulder pain.

-

•

To identify similarities and differences across websites and written information provided relating to the use of diagnostic imaging for those with LBP, knee, and shoulder pain in order to understand the influence of website quality on recommendation consistency with reference to best available evidence from clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations.

2. Methods

This scoping review was designed with reference to guidance from the Joanna Briggs Institute [22] and reported in line with the PRISMA guidance extension for scoping reviews [23]. The protocol for this scoping review was published previously via the Open Science Framework (osf.io/x3dq5) on the 21st February 2020. Any deviations from the protocol are outlined below.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Public-facing websites were included if they:

-

-

provided written healthcare information related to either LBP, knee, or shoulder pain (including advertising websites)

-

-

were either based within the UK or were NHS affiliated.

Public-facing websites were excluded if they:

-

-

were video-sharing platforms, such as YouTube or Google Video

-

-

were audio-links

-

-

were not publicly accessible

-

-

were journal articles or journal websites

2.2. Search strategy & information sources

To inform the search strategy (including selection criteria of websites to be included within the review) a Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) meeting was held. This meeting was attended by five members of the public who have previously sought healthcare for various musculoskeletal conditions. The output of this meeting was a co-designed search strategy between the PPIE meeting attendees and the research team that replicated the search someone may perform to find out more about their symptoms, often prior to seeking help from a professional. It was from this meeting that the review was restricted to UK-websites only, as PPIE attendees advised they would not visit international, or non-NHS affiliated websites.

The lead author (AC) entered the following search terms into the Google search engine on the 9th June 2020, as six individual searches:

-

o

Low back pain

-

o

Knee pain

-

o

Shoulder pain

-

o

Why does my back hurt?

-

o

Why does my knee hurt?

-

o

Why does my shoulder hurt?

To ensure that the first 50 hits remained constant throughout the review process, the website domain of each of the websites returned by the search was recorded in a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) document. This ensured that the selection criteria could be independently applied by two reviewers (AC and TJ) without risk of the websites that were returned by the search being different.

2.3. Selection of sources of evidence

The selection criteria were independently applied by two members of the review team (AC and TJ) to each of the websites returned by the searches. A third member of the review team (CL) was available to arbitrate in the event of disagreement.

When viewing the websites, it was anticipated that multiple pages may need to be viewed in order to fully understand the context and obtain the information required to achieve the review objectives. As such, it was necessary to apply boundaries to the search to ensure consistency, reproducibility, and rigour. Within each website, a hyperlink, or Portable Document Folder (PDF) that led to information hosted within the same website was explored and included within the data extraction and analysis. A hyperlink which leads to information hosted within an external website was not explored or included within the data extraction. If multiple pages were viewed, or hyperlinks/PDFs explored within the same website this represented one ‘hit’ rather than multiple ‘hits’ in the context of the first 50 hits being reviewed.

2.4. Charting the results (data extraction)

The relevant characteristics of the included website(s) and the key data relevant to the review objectives were recorded in a charting table. A separate charting table was populated for lower back, knee, and shoulder websites (Supplementary File 1)

Data extraction was independently trialled by AC and TJ on the first five included websites to assess the suitability and capacity to chart all relevant information required to answer the review objectives. No changes to the data charting table were required. AC and TJ were the reviewers responsible for charting the results. A third member of the review team (CL) arbitrated in the event of disagreement.

2.5. Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

Quality appraisal within this review was used to explore the basis for any clear and substantial differences in recommendations between websites. The hypothesis was that those websites making substantially different recommendations to others would be explained by poorer quality. A clear and substantial difference in recommendation was defined as a website providing information that was not consistent with the recommendations contained within other websites, or the best available evidence. These were identified during Step 1 of the thematic analysis, informed by a recent scoping review that has synthesised CPG recommendations regarding the use of diagnostic imaging [24].

In order to understand whether website quality was the reason for clear and substantial differences in recommendations, the DISCERN Tool (Supplementary File 2) was used to appraise each website (Supplementary File 3). The DISCERN Tool was chosen as its reliability has been demonstrated [19] and it has been used in similar reviews of website information [15,25]. Each website was appraised by AC using the DISCERN Tool and verified by TJ. A third member of the review team was available to arbitrate (CL) in the event of disagreement.

2.6. Synthesis of results

Extracted data (Supplementary File 1) was analysed using the six principles outlined by Braun and Clarke [26] whereby the aims of the thematic analysis are to identify, analyse and report patterns within the data.

The initial step involved familiarisation of the data extracted through a process of reading and re-reading (Step 1). During this process, codes were applied to aggregate the text (Step 2) before being organised together to form preliminary themes (Step 3). A theme is a broad unit of information that is made up of several codes grouped together to form a common idea [27]. This analysis was conducted independently by AC and verified by a second member of the review team (TJ). A third member of the review team was available to arbitrate (CL) in the event of disagreement. These preliminary themes were then critically reviewed by all members of the research team, refined, and iteratively developed (Step 4) in order to provide more meaning to the data prior to the final themes being defined (Step 5). The final step involved outlining the results of the analysis.

3. Results

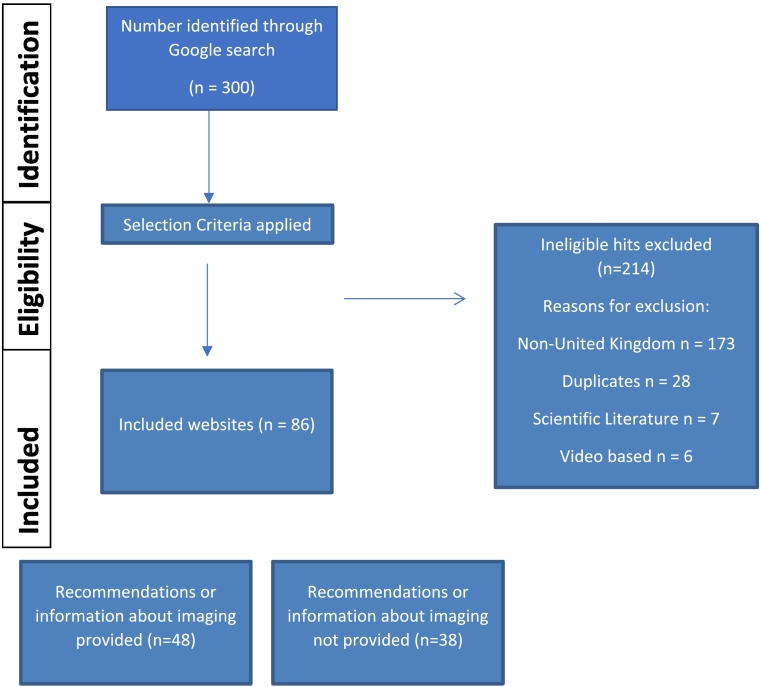

The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1. From 300 identified websites, 214 were excluded leaving 86 public-facing websites included in the review.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the Selection Process.

3.1. Regional MSK condition

Within the websites included in this review, 38 (n = 14 for LBP; n = 14 for knee pain; n = 10 for shoulder pain) did not contain information on diagnostic imaging.

Of those public-facing websites that did provide recommendations or information on the use of diagnostic imaging (n = 48), 17 related to LBP, 15 for knee pain and 16 for shoulder pain.

Table 1 outlines the included websites and whether or not they made provided recommendations of information for imaging.

Table 1.

Included websites and whether or not they made provided recommendations of information for imaging.

3.2. Public-facing websites and their recommendations or information on the use of diagnostic imaging

A charting table for LBP, knee, and shoulder pain was created to describe the identified public-facing websites that may be used as sources of written healthcare information and to describe the written content within these websites (Tables 2 – 4 in Supplementary File 1).

3.2.1. Critical appraisal within sources of evidence

There were five websites (two related to LBP, three for knee pain) with clear and substantial differences to the recommendations provided by other websites, and with reference to the best available evidence from CPG recommendations [24]. Each of these five websites [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]] was categorised by the DISCERN Tool (Tables 2-3) as having serious limitations and in turn deemed not to be a useful source.

Of the 48 websites that provided recommendations or information on the use of diagnostic imaging, 16 (five related to LBP, six for knee pain and five for shoulder pain) were categorised as having serious limitations (scoring a 1 or a 2; Supplementary File 2) and in turn, not useful resources (including the five that make clear and substantially different recommendations). It would appear that clear and substantial differences related to imaging content may be explained by lower website quality, but not exclusively.

3.3. Narrative synthesis

Following familiarisation, initial codes were labelled across the data set to identify text that were relevant to the research aims.

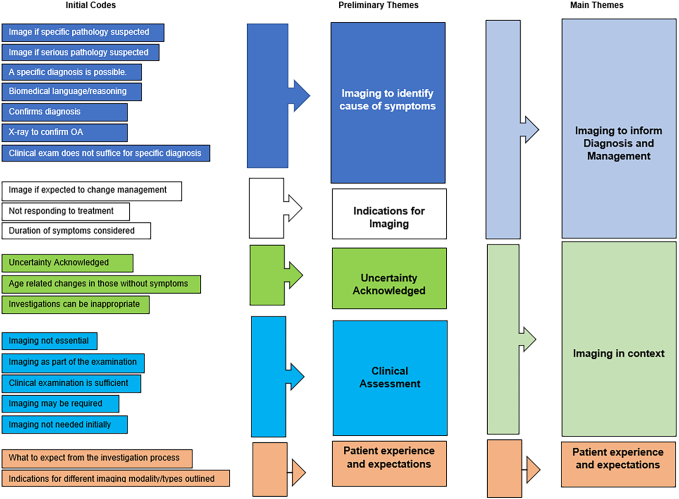

There were 20 initial codes (Supplementary File 4). These initial codes were then reviewed and refined where commonality existed in order to provide more meaning to the data. This step resulted in the refinement of the 20 initial codes into five preliminary themes (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Themes identified from the recommendations or information provided within public-facing websites on the use of diagnostic imaging for LBP, knee, and shoulder pain. Colour when in print.

To complete the synthesis, the preliminary themes were reviewed with reference to the coded data. This resulted in the refinement of the five preliminary themes into three main themes: ‘Imaging to Inform Diagnosis and Management’, ‘Imaging in Context’, and ‘Patient experience and expectations’.

These three main themes were reviewed by the team with reference to both the coded data and the entire data set. This step in the process resulted in no further refinement, with the following themes identified within the written information of public-facing websites regarding imaging for LBP, knee, and shoulder pain.

3.3.1. Imaging to inform diagnosis and management

This theme was consistent across LBP, knee, and shoulder pain. The role of diagnostic imaging to inform diagnosis and management is a clear theme across the written information and recommendations within public-facing websites. These recommendations were framed within the context that a diagnosis is possible, and that imaging is the gold standard to both inform and confirm diagnosis:

An x-ray [35] can usually confirm the diagnosis (kyphosis)

Chiropractors [36] rely on x-rays…and MRI scans for diagnosis (low back pain)

…sometimes an x-ray [78] may be arranged if a clinician is uncertain (knee pain)

…ultrasound or MRI can also be helpful in confirming a diagnosis of painful arc in impingement syndrome (104).

This was particularly relevant where either a serious (such as cauda equina syndrome) or specific (such as a spondylolisthesis) pathology was suspected:

If cauda equina syndrome is suspected the patient must undergo an MRI urgently to confirm the diagnosis [34].

In addition to the use of imaging in this context, recommendations also indicated that imaging should be used where symptoms have persisted despite treatment and the results of the imaging expected to change clinical management:

If your symptoms do not get better after treatment (knee bursitis), you may be referred for further tests [75].

In some cases [102] ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging can be useful, these are only considered if it will guide treatment (rotator cuff tendinopathy).

3.3.2. Imaging in context

Aligned to, but in slight contrast to the above theme, the second theme related to the use of diagnostic imaging in context, again this theme was consistent across LBP, knee, and shoulder pain. The recommendations acknowledged the uncertainty underpinning the use of imaging, in particular the prevalence of changes seen on imaging in those populations without symptoms:

While people with low back pain [43] are more likely to have disc degeneration show up on an MRI, so will a large number of people without back pain

Osteoarthritis of the AC joint (shoulder pain) cannot be reliably diagnosed by X-ray as, although degeneration may be revealed, similar findings can be seen in asymptomatic individuals [108].

There is a significant false positive rate from MRI of the knee. Abnormal findings have been reported in health individuals with no knee symptoms [76].

Within such a context, the possibility of overuse of diagnostic imaging is outlined with reference to consideration of whether imaging is required, and if obtained, should be interpreted in the context of the clinical presentation, rather than in isolation:

Radiographs and MRI of CT scans are often obtained (low back pain). Abnormalities are frequently found in such imaging. This is often unrelated to symptoms and should be interpreted in the context of the clinical picture [44].

Diagnosis is usually made from the patient’s history and a simple examination without the need for further investigations (knee pain). Sometimes an x-ray may be arranged if a clinician is uncertain about the diagnosis or wishes to see the extent of the osteoarthritis [78].

X-rays are good for looking for problems with the bones in your shoulder and minor changes in the joints [89]. However, small changes are quite common and may not be the cause of your trouble (shoulder pain).

3.3.3. Patient experience and expectations

Where an investigation is required, what to expect from the process and what imaging modality to expect is described. In particular, what to expect from the process is outlined for the less common imaging modalities such as DEXA [33] and CT Scan [34]:

If your doctor thinks you may have osteoporosis, they may suggest you have a DEXA (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry) scan to measure the density of your bones. The scan is readily available and involves lying on a couch, fully clothed, for about 15 minutes while your bones are x-rayed [37].

An ultrasound scan can show swelling [89], as well as damage and problems with the tendons, muscles, or other soft tissues in the shoulder. It uses high-frequency sound waves to examine and build pictures of the inside of the body (shoulder pain).

MRI scanning [76] may give much more detail of soft tissues but changes seen may not correlate with the degree of symptoms (anterior knee pain).

There was consistency with regard to x-ray being utilised as a first-line investigation if the suspected diagnosis is related to the bone i.e. fracture, with a CT scan reserved as a second-line investigation following x-ray if further detail is required:

Spondylolisthesis can easily be confirmed by taking an X-ray of your spine from the side while you’re standing. This will show whether a bone in your spine has slipped out of position or if you have a fracture. If you have pain, numbness, tingling or weakness in your legs, you may need additional tests, such as a CT scan or an MRI scan [35].

Where a suspected diagnosis is not related to the bone i.e. soft tissue injury, there was again consistency in that for those with LBP or knee pain an MRI scan is the investigation of choice to both assess the soft tissues but also to rule out serious pathology:

X-rays aren’t usually helpful as cartilage doesn’t show up on the x-ray (patellofemoral pain). Your doctor may suggest an MRI scan, for example if you’ve received a blow to your knee [74].

Whilst for the shoulder, an Ultrasound Scan (USS) was recommended as the first-line investigation with an MRI scan reserved as a second-line investigation following USS, should further detail be required:

Ultrasound is the examination of choice (biceps tendinopathy) …MRI scan can demonstrate the whole course of the biceps tendon (including the intra-articular tendon and related intra-articular pathology). However, it is not appropriate or cost-effective for routine use. It is indicated after unsuccessful rehabilitation or where there is suspected rotator cuff or labral tear injury [108].

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to describe and synthesise the content of public-facing websites with respect to the use of diagnostic imaging for adults with LBP, knee, and shoulder pain. To the author’s knowledge, this represents the first review of its kind with reference to describing and synthesising public-facing websites and reviewing the written information and recommendations for use of diagnostic imaging within these. This review identified three main themes that when combined, outline the key messages contained within public-facing websites regarding the use of diagnostic imaging for LBP, knee, and shoulder pain: (i) imaging to inform diagnosis and management; (ii) imaging in context; and (iii) patient experience and expectations.

Of the 48 websites that including recommendations or information on diagnostic imaging, there were five (n = 2 related to LBP, n = 3 for knee pain) websites with clear and substantial differences to the recommendations provided by other websites, with reference to the best available evidence. These five websites each demonstrated serious limitations and in turn were considered not to be useful sources of information. However, other websites for LBP (n = 3) and knee pain (n = 3) which were also identified as having serious limitations, provided recommendations that were consistent with those provided by websites deemed useful and appropriate. None of the included websites for shoulder pain made recommendations regarding imaging that were clear and substantially different. However, five of the included shoulder websites demonstrated serious limitations and were considered to not be useful sources of information. It would appear that clear and substantial differences related to imaging content may be explained by lower website quality, but not exclusively. Other factors not explored as part of this review, such as credibility, currency or comprehensiveness may explain this difference [21].

The findings of this scoping review suggest that the majority of written information and recommendations within public-facing websites are consistent with the recommendations within CPGs that inform UK clinical practice. A recent scoping review concluded that routine use of diagnostic imaging should be discouraged and reserved for clinical circumstances where there is a suspicion of specific or serious pathology, or where the person is not responding to initial non-surgical management and the imaging result is expected to change that persons clinical management [24]. SDM involves clinicians and patients sharing the best available evidence, with patients being supported to consider options [113]. This consistency between information and recommendations within public-facing websites and CPGs is a key enabler to effective SDM and personalised care. Despite this consistency, there is a lack encouragement for patients to engage with SDM contained within public-facing websites with only seven of the 48 included websites (Supplementary File 3) explicitly encouraging SDM [33,36,42,56,65,97,114].

With the use of diagnostic imaging increasing within primary and intermediate care in the UK, patient expectations or beliefs have been suggested to be one factor that might explain the rise in imaging requests [7,8,115]. It has been shown in the UK that 96% of people are satisfied with the health-related information that they have seen on the internet, with 61% of people obtaining health information via the internet over a 12-month period [116]. For those with shoulder pain [117], more people utilised internet searches (52.5%) to obtain health-related information than consulting their physiotherapist (49.2%) or their family and friends (14.2%). Given the consistency between public-facing website recommendations and clinical guideline recommendations, and the extent to which the internet is used by the public and patients to obtain health-related information, the written information contained within the public-facing websites does not appear to explain the increase in imaging rates seen in the UK. Future research should look to understand the reasons for requesting diagnostic imaging for musculoskeletal pain conditions affecting the LBP, knee, or shoulder, from the perspective of the referring clinician and patients.

The written information contained within public-facing websites, being consistent with clinical guideline recommendations, is not a constant finding within the wider literature. A systematic review of the credibility, accuracy and comprehensiveness of treatment recommendations for lower back pain contained within public-facing websites demonstrated that the majority of websites did not demonstrate credibility, lacked comprehensiveness and provided a high proportion of inaccurate recommendations when compared to those within CPGs [21]. The difference in consistency found between website information and CPG recommendations within this systematic review and the current scoping review, may be explained by the difference in area of research focus as well as the methods used, which introduce greater potential for variation. The systematic review by Ferreira et al. [2019] focused on recommendations for treatment within CPGs, rather than recommendations for use of diagnostic imaging. With regard to methods used, the search strategy employed within the systematic review was developed by the research team, rather than co-produced through PPIE. The current scoping review limited websites to those that were either UK-based or NHS affiliated whilst the systematic review included websites that were based in five major English-speaking countries, with the majority of included websites being based in the United States. Further, whilst the current scoping review included public-facing websites for LBP, knee, and shoulder pain, the systematic review included websites for LBP only [21].

To date, this represents the first review of its kind with reference to describing and synthesising public-facing websites. Within this review the written information and recommendations for use of diagnostic imaging were summarised, appraised, and comparted to the best available evidence. The strengths of this scoping review include that it was conducted in accordance with good practice as recommended for the conduct of scoping reviews [22] and the methods have been reported transparently, allowing for replication, including the previous publication of the protocol.

The involvement of a patient group to design the search strategy should be considered a strength within the context of this review. Within the PPIE meeting, video sources of information were not discussed, and as such the subsequent focus of this review being on written information contained within the public-facing websites. Therefore, a pragmatic approach was taken to limit the focus of this review to written information. The limitation of this is acknowledged in that video-based content is becoming increasingly popular and utilised [118]. Future research should look to messages contained within publicly available video-based content to understand the recommendations within such a medium to the public regarding the use of diagnostic imaging. Within a scoping review, critical appraisal is not used to inform risk of bias and subsequent interpretation as it would within a systematic review which may influence the interpretation of the results.

4.2. Innovation

Increasing internet access, when combined with patient expectation has been seen as a potential cause of increased use of diagnostic imaging within the NHS, influencing beliefs regarding the necessity and utility of diagnostic imaging for musculoskeletal pain. This review frames innovation generally, using a novel search strategy designed with patients to replicate a search for information that that they would undertake should they have lower back, knee, or shoulder pain when they are looking for health information. The results demonstrated that the written information contained within public-facing websites is largely aligned with best evidence, and in turn does not appear to explain the increase in imaging rates observed.

4.3. Conclusion

The key messages contained within public-facing websites regarding the use of diagnostic imaging outlined what patients should expect in terms of imaging modality and the experience when undergoing less common modalities. Where imaging is used, it should be to inform diagnosis and management within the context of the clinical presentation, rather than in isolation.

Written information contained within public-facing websites does not appear to explain the increase in imaging rates seen in the UK for these common musculoskeletal pain presentations. Future studies should seek to understand the reasons for requesting diagnostic imaging for musculoskeletal pain affecting the LBP, knee, or shoulder, from the perspective of the referring clinician and patients.

Funding

This work was supported by an ACORN PhD Studentship from Keele University, and a PhD Studentship from Manchester Metropolitan University.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Andrew Cuff: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Thomas Jesson: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Gillian Yeowell: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision. Lisa Dikomitis: Conceptualization, Supervision. Nadine E. Foster: Conceptualization, Supervision. Chris Littlewood: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authorship declares no competing interests. Competing interests are defined as those potential influences that may undermine the objectivity, integrity, or perceived conflict of interest of a publication.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100040.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

Supplementary material 3

Supplementary material 4

References

- 1.Jordan K.P., Kadam U.T., Hayward R., Porcheret M., Young C., Croft P. Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: An observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(144):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urwin M., Symmons D., Allison T., Brammah T., Busby H., Roxby M., et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: The comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(11):649–655. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.11.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cadogan A., Laslett M., Hing W., McNair P., Coates M. A prospective study of shoulder pain in primary care: prevalence of imaged pathology and response to guided diagnostic blocks. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langridge N., Roberts L., Pope C. The clinical reasoning processes of extended scope physiotherapists assessing patients with low back pain. Man Ther [Internet] 2015;20(6):745–750. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.005. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langridge N. The skills, knowledge and attributes needed as a first-contact physiotherapist in musculoskeletal healthcare. Musculoskeletal Care [Internet] 2019;1–8 doi: 10.1002/msc.1401. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuff A., Littlewood C. Subacromial impingement syndrome – What does this mean to and for the patient? A qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract [Internet] 2018;33:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.10.008. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS England . 2019. Transforming elective care services radiology: Learning from the Elective Care Development Collaborative; pp. 1–44.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/radiology-elective-care-handbook.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou L., Ranger T.A., Peiris W., Cicuttini F.M., Urquhart D.M., Sullivan K., et al. Patients’ perceived needs for medical services for non-specific low back pain: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS England . 2019. The NHS Long Term Plan; pp. 1–136. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidd M.O., Bond C.H., Bell M.L. Patients’ perspectives of patient-centredness as important in musculoskeletal physiotherapy interactions: a qualitative study. Physiotherapy [Internet] 2011;97(2):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.08.002. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin J.J. Doctor-patient relationship: from medical paternalism to enhanced autonomy. Singap Med J. 2002;43(3):152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stats I.W. Internet Usage Statistics [Internet]. WORLD Internet Usage And Population Statistics 2019 - Mid-Year Estimates. 2019. https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm [cited 2019 Dec 18]. Available from:

- 13.Statistics O of N . Internet users; UK: 2019: 2019. Internet users, UK: 2019.https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2019 [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statista. Share of individuals who have used the internet to search for health care information in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2015 [Internet]. Share of individuals who have used the internet to search for health care information in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2015. Available from:https://www.statista.com/statistics/505053/individual-use-internet-for-health-information-search-united-kingdom-uk/.

- 15.Maloney S., Ilic D., Green S. Accessibility, nature and quality of health information on the Internet: A survey on osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2005;44(3):382–385. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrow A., Palmer S., Thomas S., Guy S., Brotherton J., Dear L., et al. Quality of web-based information for osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Physiotherapy [Internet] 2018;104(3):318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2018.02.003. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler L., Foster N.E. Back pain online: A cross-sectional survey of the quality of Web-based information on low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28(4):395–401. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000048497.38319.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrick P.A., Ahmed O.H., Bankier S.S., Chan T.J., Crawford S.A., Ryder C.R., et al. Acute low back pain information online: An evaluation of quality, content accuracy and readability of related websites. Man Ther [Internet] 2012;17(4):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.02.019. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charnock D., Shepperd S., Needham G., Gann R. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(2):105–111. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varady N.H., Dee E.C., Katz J.N. International assessment on quality and content of internet information on osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil [Internet] 2018;26(8):1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.04.017. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira G., Traeger A.C., MacHado G., O’Keeffe M., Maher C.G. Credibility, accuracy, and comprehensiveness of internet-based information about low back pain: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(5):1–10. doi: 10.2196/13357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C.M., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuff A., Parton S., Tyer R., Dikomitis L., Foster N., Littlewood C. Guidelines for the use of diagnostic imaging in musculoskeletal pain conditions affecting the lower back, knee and shoulder: a scoping review. Musculoskeletal Care. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1002/msc.1497. July. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaicker J., Debono V.B., Dang W., Buckley N., Thabane L. Assessment of the quality and variability of health information on chronic pain websites using the DISCERN instrument. BMC Med [Internet] 2010;8(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-59. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/8/59 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cresswell J., Poth C. 4th ed. Sage Publications, Ltd; London: 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design - Choosing Among Five Approaches; p. 459. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MRI BP Turn your Back on Lower Back Pain [Internet] https://www.back-pain-mri.com/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B8wow9reAsvACifbODwiQTZ2-srqgJaFqHS9jKbo-9Ea1CriZMoPoYaAvLqEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 29.Crosby Physio Low Back Pain [Internet] http://crosbyphysio.com/what-we-can-treat/spinal/low-back-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 30.Patel Rahul. Knee Pain [Internet] www.rahulpatel.net [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 31.Acuraflex. Acuraflex [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. p. 53. Available from:https://acuraflex.co.uk/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B-Qe2YAeQ1pSFd5P0YwhAvErb8c1XCkZYXAU2rTU3DRYs7XhaRFrbAaAuyPEALw_wcB.

- 32.Osmopatch Knee Pain [Internet] 2019. https://www.osmopatch.co.uk/conditions/knee-pain/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B8wE8cHKNIeUj-CDmYdN30AysXAapE5bZeaaWvvsr2jFQHAsqJIihIaAj1KEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 33.BUPA Lower back pain [Internet] 2019. https://www.bupa.co.uk/health-information/back-care/back-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 34.Physiopedia Low Back Pain [Internet] 2020. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 35.National Health Service Back Pain [Internet] 2020. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/back-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 36.Nursing Times Back Pain [Internet] 2009. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/pain-management/back-pain-23-03-2009/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 37.Versus Arthritis Back Pain [Internet] https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/back-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 38.Your Pharmacy Back Pain [Internet] 2005. https://www.your-pharmacy.co.uk/shop-by-brand/nurofen/back-pain/cat-2005?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B8u6y- 9ZbfLAFhdshlwFeB4lxHtiF70eGFbjmFbESsZhc8zv41gZUcaAqBmEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds [cited 2020 Jul 1]. p. 2005. Available from:

- 39.Elite Health Chiropractic Elite Health Chiropractic [Internet] http://elitehealthchiropractic.co.uk/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B-JscJJGW6FIpci8rrXXXEb0L5R-jqUGOXjdrJZQkaR1yWnNUhSgr8aAl8rEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 40.Anadin. Back and muscle pain [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. p. 83. Available from:https://www.anadin.co.uk/whats-your-pain/back-muscle-pain?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B-j83XNdLF- ebETC2PYC_K4FGCnkNDG3uB6kRGtLRublWr3pe9VcR8aAqpnEALw_wcB.

- 41.Patient.Info Lower Back Pain [Internet] 2016. https://patient.info/bones-joints-muscles/back-and-spine-pain/lower-back-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 42.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Low back pain in adults: early management [Internet] 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 43.The Guardian Back pain - how to live with one of the worlds’ biggest health problems [Internet] 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jun/14/back-pain-how-to-live-with-one-of-the-worlds-biggest-health-problems [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 44.Ministry of Defence Low Back Pain [Internet] 2008. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/384519/low_back_pain.pdf [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 45.Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust Non-Specific Low Back Pain [Internet] 2019. https://www.royalberkshire.nhs.uk/patient-information-leaflets/Pain Management/AandE Back pain non specific lower back p ain.htm [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 46.Zivaa Strong after section [Internet] https://www.zivaa.com/strong-after-section/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_N04cdXigYefHsC7zgYk0cJwFPyKBJKs8T629v2Z ErA9uyccGANu4aAghnEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 47.Gentle Chiropractic Gentle Chiropractic [Internet] https://www.gentle-chiropractic.co.uk/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 48.Happy Psoas Interactive Dynamic Cushion [Internet] https://www.happypsoas.co.uk/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_r0t6zPhykZO36WTiu4n24 HvGDX7lxrAQMN4e-ti9kpRH8mmRjJrgaAhk6EALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 49.Chiropractic UK Back Pain [Internet] https://chiropractic-uk.co.uk/back-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 50.Sport Injury Clinic Low Back Pain [Internet] 2019. https://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/sport-injuries/back/low-back-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 51.Oxford University Hospital NHS Trust Low Back Pain [Internet] https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/5712Plowbackpain.pdf [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 52.Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Trust Chronic Lower Back Pain [Internet] 2012. https://www.qvh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Chronic-Lower-Back-Pain.pdf [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 53.The Guardian Everything you ever wanted to know about back pain but were afraid to ask [Internet] 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/nov/30/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-back-pain-but-were-afraid-to-ask [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 54.Leukaemia Care Could muscle or back pain indicate leukaemia? [Internet] https://www.leukaemiacare.org.uk/support-and-information/latest-from-leukaemia-care/blog/could-muscle-or-back-pain-indicate-leukaemia/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B9TdHPxx1TDamtbD64HQ2JzPH6- xuQ26FbXXlxjXmaAKT4TvuCireQaAsv1EALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 55.Top MRI Advanced Medical Imaging [Internet] https://topmri.com/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B9WnHQSTDb7QtxW1jT7Kg8oo4tTExH6rpIW9GpJPxkgBs704ILBAq4aAjpyEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 56.Brain and Spine Foundation [Internet] https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/supporting-you/helpline/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B-ohMBHK-hxtm-d3nfeDZYLMpFElZ7eo5YQFVvdf7CTy5nvhoaz3d0aAlbKEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. p.53 Available from:

- 57.Shoes for Crews Why is my back aching after a shift? [Internet] https://blog.sfceurope.com/why-is-my-back-aching-after-a-shift [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 58.Manchester Evening News Why does my back hurt during sex? [Internet] 2013. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/fashion-news/why-does-my-back-hurt-during-sex-986123 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 59.Capital Physio Lower back pain from squats why this happens and how to avoid it [Internet] https://www.capitalphysio.com/fitness/lower-back-pain-from-squats-why-this-happens-and-how-to-avoid-it/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 60.Refinery 29 Lower Back Pain [Internet] https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/lower-back-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 61.The Independent Back Pain - I was only in my early thirties but I felt like an old lady [Internet] https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/features/back-pain-i-was-only-in-my-early-thirties-ndash-but-i-felt-like-an-old-lady-1975563.html [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 62.Amazon Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=knee+pain&adgrpid=55947714471&gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_phek5w0n_ihegq_DzT7-eAdIv804_qjnfY7fPx9Az9GSaz8k3j6IaAuGREALw_wcB&hvadid=259047401210&hvdev=c&hvlocphy=1007064&hvnetw=g&hvqmt=b&hvrand=15650495512940835342&hvtargi [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 63.National Health Service Knee Pain [Internet] 2017. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/knee-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 64.Versus Arthritis Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/knee-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 65.BUPA Explore your knee pain [Internet] https://www.bupa.co.uk/health-information/knee-clinic/explore-knee-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 66.Voltarol Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.voltarol.co.uk/pain-treatments/knee-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 67.Runners World 4 Cause of Knee Pain and How to Fix them [Internet] 2017. https://www.runnersworld.com/uk/health/injury/a773762/4-causes-of-knee-pain-and-how-to-fix-them/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 68.Hisamitsu Salonpas [Internet] https://uk.hisamitsu/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B8SuMfelbVI_lJBJ-jOY8vjnu4d9p0MlUU7B3HfDdf_H49fxD0JaKEaAkbMEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 69.Ultralieve Ultrasound Therapy [Internet] https://www.ultralieve.com/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_BF2uYTBVG1kZwgJV7Pc7MON8BkKld_2LS1hoyU_WiEL4uFDqeU7saAiL5EALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 70.Blackberry Clinic Prolotherapy [Internet] https://www.blackberryclinic.co.uk/landing_page/prolotherapy/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_M0Ssv0CQg2X4jscRdlBQp7-5Xu1FDXs7heuIId-xAUEJORYf2qP4aAtmVEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 71.Active 650 Knee Support [Internet] https://www.active650.co.uk/products/full-knee-support?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_5xdixmpKHtnzv9mdU_WaBHHiicZxI4Nb4s4KfMw6UNO--_2AWptIaAgAwEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 72.Clinic SI . 2019. Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/sport-injuries/knee-painp. 76. [cited 2020 Jul 1] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chartered Sociery of Physiotherapy Video exercises for knee pain [Internet] 2012. https://www.csp.org.uk/conditions/knee-pain/video-exercises-knee-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 74.PhysioHey Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 75.NHS Direct Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/conditions/knee-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 76.Patient Info Anterior Knee Pain [Internet] 2015. https://patient.info/doctor/anterior-knee-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 77.Circle Health Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.circlehealth.co.uk/integratedcare/knee-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 78.North West Boroughs Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.nwbh.nhs.uk/knee [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 79.Avogel Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.avogel.co.uk/health/muscles-joints/joint-pain/knee-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 80.IOsteopathy Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.iosteopathy.org/event/knee-pain-diagnosis-treatment-and-rehab/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 81.Capital Physio Knee Pain [Internet] https://www.capitalphysio.com/health-news/inside-knee-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 82.Just Answer Orthopaedics [Internet] 2020. https://www.justanswer.co.uk/sip/orthopedics?r=ppc%7Cga%7C5%7C1683661621%7C64841937079%7C&JPKW=%2Bknee%2Bpain&JPDC=S&JPST=&JPAD=326911692843&JPMT=b&JPNW=g&JPAF=txt&JPRC=1&JPCD=20190122&JPOP=&JCLT=&cmpid=1683661621&agid=64841937079&fiid=&tgtid=kwd-1890447 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 83.Nurofen Muscular Pain [Internet] 2020. https://www.nurofen.co.uk/blogs/symptoms-advice/muscular-pain?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B8HoIfi4EbXIXr8HVkCAICRvlpduzptyPv47cUMAKzcilOi -GQTybkaAkeREALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 84.BMI Healthcare What’s wrong with my knee? https://www.bmihealthcare.co.uk/health-matters/health-and-wellbeing/whats-wrong-with-my-knee [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 85.Better Braces Inside Knee [Internet] https://www.betterbraces.co.uk/injury-info-center/knee-injury-guide/inside-knee [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 86.Actesso Knee supports for injury [Internet] https://actesso.co.uk/knee-supports-for-injury/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B9OQaUihEeVOmhQGwZtMfA1NKnxRauFIul0zg455j zkP7mWLVNifSAaAnuvEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 87.Amazon Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=shoulder+pain&adgrpid=52358118199&gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B-0UZn4rtwFjHHxgAnk5z5SdRuGeatbWwdVGXReHr6dJ-tUvuI1vBYaAgyjEALw_wcB&hvadid=259085132347&hvdev=c&hvlocphy=1007064&hvnetw=g&hvpos=1t2&hvqmt=e&hvrand=10602600090041 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 88.Shoulder2Wrist Shoulder2Wrist [Internet] http://www.shoulder2wrist.co.uk/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B9j7PArYvk7j3jlG7IUVE3WLhHQDsgXEB1tZWZnVPktf67A1bwtohgaAiz8EALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 89.Versus Arthritis Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/shoulder-pain/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B-0kIEWEDGW5YZbTunEoMuESl5Qua_X5ViheespppnF2FDV44Ulz6AaAvFlEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 90.National Health Service Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/shoulder-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 91.Chartered Society of Physiotherapy Video exercises for shoulder pain [Internet] https://www.csp.org.uk/conditions/shoulder-pain/video-exercises-shoulder-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 92.Voltarol Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.voltarol.co.uk/pain-treatments/shoulder-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 93.NICE CKS Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2017. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/shoulder-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 94.Ibuleve Pain Relief Products [Internet] https://www.ibuleve.com/products?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B9TYcEqt0CBD7CytI0kAN m4ME5QbNljBOTdV40tch6yX_93m3ICcIAaAh6nEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 95.Shoulder Unit Shoulder Unit [Internet] https://www.shoulderunit.co.uk/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B_3RUi0vYybSDRxXmH- E_Hhn5eFhsIEb-C9s-wVEfo9q9WfKMNWgS0aAnT7EALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 96.Izito Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.izito.co.uk/ws?q=shoulder pain treatments&asid=iz_uk_2_010_010&mt=b&nw=g &de=c&ap=1o3&ac=1913&gclid=Cj0KCQiA7OnxBRCNARIsAIW53B9XTyfxN9xDlvoL6qi_U5499ojYfN Up7K8pCbTPooUuPwJ7W2lHMp8aAn5_EALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 97.Patient Info Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2018. https://patient.info/bones-joints-muscles/shoulder-pain-leaflet [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 98.Shoulder Unit Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.shoulderunit.co.uk/services/shoulder-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 99.Highgate Hospital Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2019. https://www.highgatehospital.co.uk/gp-news/experiencing-shoulder-pain/ [cited 2020 Jan 1]. Available from:

- 100.NHS Inform Shoulder Problems [Internet] 2020. https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/muscle-bone-and-joints/self-management-advice/shoulder-problems [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 101.North West Boroughs Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.nwbh.nhs.uk/shoulder-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 102.AHP Suffolk Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2020. https://ahpsuffolk.co.uk/Home/SelfHelp/ShoulderPain.aspx [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 103.Herefordshire and Worcestershire Health and Care NHS Trust Shoulder Pain [Internet] https://www.hacw.nhs.uk/shoulder-pain/ [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 104.Southend University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2012. http://www.southend.nhs.uk/media/188256/shoulderpainincexcercise.pdf [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 105.Sport Injury Clinic Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2018. https://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/sport-injuries/shoulder-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 106.Orth Team Centre Orth Team [Internet] https://www.orthteamcentre.co.uk/?gclid=Cj0KCQiAsvTxBRDkARIsAH4W_j_aMx0Pu4YQP8LW2Nm Y79aSCzu_zdBvdEl2pSTfZLI303LuGZwVp-caAiT5EALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 107.Claim Injury Nationwide Shoulder Injury [Internet] https://claiminjurynationwide.co.uk/slp/shoulder-injury?src=google&kw=shoulder injurysb&gclid=Cj0KCQiAsvTxBRDkARIsAH4W_j-4qZYf6yYvnHjz6HwMeDGunI19GjCW7O-VM3WkIkwpJvoyk7Xh-iYaAp9oEALw_wcB [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 108.Patient Info Shoulder Pain [Internet] 2015. https://patient.info/doctor/shoulder-pain-pro [cited 2021 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 109.Cancer Research UK Shoulder pain becomes breast cancer [Internet] 2016. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-chat/thread/shoulder-pain-becomes-breast-cancer [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 110.Top Doctors Why does my shoulder hurt? The many causes of shoulder pain [Internet] 2019. https://www.topdoctors.co.uk/medical-articles/why-does-my-shoulder-hurt-the-many-causes-of-shoulder-pain [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 111.Pop Sugar. Why does my shoulder hurt? BJSM [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:https://www.popsugar.co.uk/gdpr-consent?destination=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.popsugar.co.uk%2Ffitness%2FWhy-Does-My- Shoulder-Hurt-When-I-Run-46471666.

- 112.Amazon Shoulder pain relief [Internet] https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=shoulder+pain+relief&adgrpid=52866675013&gclid=Cj0KCQiAsvTxBRDkARIsAH4W_j_5uDFlLe4olydo9-yqTYaJujMZRUxuYe4C5VORm9wlM2P2O2gCzfMaAqbkEALw_wcB&hvadid=259095991427&hvdev=c&hvlocphy=9046265&hvnetw=g&hvqmt=b&hvrand=38193575891902514 [cited 2020 Jul 1]. Available from:

- 113.Elwyn G., Laitner S., Coulter A., Walker E., Watson P., Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS and patients should be the first step in giving patients choice. Br Med J. 2010;341(November):971–975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.NICE CKS . NICE; 2017. Shoulder Pain. Natl Inst Heal Care Excell [Internet] Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/shoulder-pain. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Keeffe M.O., Traeger A.C., Michaleff Z.O.E.A., Décary S., Garcia A.N., Zadro J.R. Overcoming overuse Part 3: mapping the drivers of overuse in musculoskeletal. Health Care. 2020;50(12):657–660. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.European Union [Internet] 2014. European citizens’ digital health literacy; pp. 1–221.https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/flash/fl_404_en.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 117.Smythe A., Rathi S., Pavlova N., Littlewood C., Connell D., Haines T., et al. Musculoskeletal science and practice self-reported management among people with rotator cuff related shoulder pain : An observational study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract [Internet] 2021;51(September 2020):102305. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102305. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Van De Belt T.H., Berben S.A.A., Samsom M., Engelen L.J.L.P.G., Schoonhoven L. Use of social media by Western European hospitals: Longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1

Supplementary material 2

Supplementary material 3

Supplementary material 4