Highlights

-

•

Ovine papillomaviruses play a role in bladder carcinogenesis in cattle.

-

•

All OaPVs were detected and quantified using droplet digital polymerase chain reaction.

-

•

Abortive and productive infections by OaPVs occurred in the urinary bladder of cattle.

-

•

Persistent infections by OaPVs could be involved in bladder carcinogenesis in cattle.

Keywords: Bladder tumors, Calpains, Cattle, Cross-species infection, Ovine papillomaviruses, PDGFβR

Abstract

Introduction

Bladder tumors of cattle are very uncommon accounting from 0.1% to 0.01% of all bovine malignancies. Bladder tumors are common in cattle grazing on bracken fern-infested pasturelands. Bovine papillomaviruses have a crucial role in tumors of bovine urinary bladder.

Aim of the study

To investigate the potential association of ovine papillomavirus (OaPV) infection with bladder carcinogenesis of cattle.

Methods

Droplet digital PCR was used to detect and quantify the nucleic acids of OaPVs in bladder tumors of cattle that were collected at public and private slaughterhouses.

Results

OaPV DNA and RNA were detected and quantified in 10 bladder tumors of cattle that were tested negative for bovine papillomaviruses. The most prevalent genotypes were OaPV1 and OaPV2. OaPV4 was rarely observed. Furthermore, we detected a significant overexpression and hyperphosphorylation of pRb and a significant overexpression and activation of the calpain-1 as well as a significant overexpression of E2F3 and of phosphorylated (activated) PDGFβR in neoplastic bladders in comparison with healthy bladders, which suggests that E2F3 and PDGFβR may play an important role in OaPV-mediated molecular pathways that lead to bladder carcinogenesis.

Conclusion

In all tumors, OaPV RNA could explain the causality of the disease of the urinary bladder. Therefore, persistent infections by OaPVs could be involved in bladder carcinogenesis. Our data showed that there is a possible etiologic association of OaPVs with bladder tumors of cattle.

1. Introduction

Tumors of the urinary bladder are uncommon in cattle, with a prevalence ranging from 0.1% to 0.01% of all bovine malignancies (Pamukcu, 1974). However, disease is very frequently seen in cattle and water buffaloes reared on pasturelands, where bracken fern (Pteridium spp.) grows abundantly. In these endemic areas, up to 90% of adult animals may be affected (Pamukcu, 1974; Pamukcu et al., 1976; Carvalho et al., 2006; Roperto et al., 2010; Roperto et al., 2013). It is worth noting that the urinary bladder of these herbivores is a target for bracken genotoxins, such as ptaquiloside (PT) (Prakash et al., 1996). PT is believed to be responsible for adenine alkylation of codon 61 of the H-ras gene, which causes a glutamine 61 substitution. Ras proteins regulate signaling pathways involved in many cellular responses, such as proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Ras proteins are activated when bound to guanosine triphosphate (GTP). Ras-GTP signaling is terminated by hydrolysis to Ras guanosine diphosphate (Ras-GDP). Glutamine 61 is essential for GTP hydrolysis, and substitution of any amino acid at this position blocks hydrolysis. Accordingly, the active GTP-bound conformation (Ras-GTP) accumulates in cells, thereby causing abnormal cell proliferation and differentiation (Schubbert et al., 2007).

A synergism between chronic ingestion of bracken fern (Pteridium spp.) and bovine papillomavirus (BPV) infection can result in chronic inflammation and urinary bladder tumors, which are responsible for bovine enzootic hematuria (BEH), a clinical syndrome characterized by bloody urine, anemia, progressive emaciation, and death of affected animals (Campo et al., 1992; de Alcântara et al., 2021; Medeiros-Fonseca et al., 2021). Although numerous bacterial isolates have been found in the urine of cattle with bladder neoplasia, their role, if any, remains to be elucidated (Roperto et al., 2012). Currently, bovine deltapapillomaviruses, namely, bovine papillomavirus types 1, 2, 13, and 14 (BPV1, BPV2, BPV13m BPV14) are the only viral agents known to be associated with bladder neoplasia in cattle. In naturally occurring bladder tumors of cattle and water buffaloes, the E5 oncoprotein transforms cells by activating the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor (PDGFβR) (Roperto et al., 2013). Additional minor and alternative transformation pathways are also known to be activated. E5 exerts its transforming activity via calpain-3, which is proteolytically active in urothelial neoplastic cells of cattle (Roperto et al., 2010). Furthermore, the E5 oncoprotein binds to the D subunit of the V1-ATPase proton pump in bovine tumor cells, which may result in perturbation of proteostasis and autophagic responses (Roperto et al., 2014). E6 interacts with the focal adhesion protein paxillin (Tong and Howley, 1997). E7 contributes to cell transformation via binding to p600 (De Masi et al., 2005). Recently, E6 oncoprotein levels were quantified in urothelial neoplastic cells transformed by BPV-2 and BPV-13, showing that E6 has an important role in cell proliferation and may be related to tumor initiation and promotion (de Alcântara et al., 2021).

Ovine papillomaviruses (OaPVs – Ovis aries Papillomaviruses) are oncogenic viruses comprising four genotypes. OaPV1, OaPV2, and OaPV4 belong to the genus Deltapapillomavirus, whereas OaPV3 is a Dyokappapapillomavirus (PaVE, 2022). OaPV1, OaPV2, and OaPV4 exhibit tropism for both keratinocytes and fibroblasts (Tore et al., 2017); OaPV3 exclusively infects keratinocytes (Alberti et al., 2010). OaPVs have been associated with ruminal fibropapillomas, cutaneous papillomas, papillomatosis, and fibropapillomas in sheep (Gibbs et al., 1975; Vanselow et al., 1982; Trenfield et al., 1990; Tilbrook et al., 1992; Hayward et al., 1993; Uzal et al., 2000; Norval et al., 1985). Although it has been speculated that OaPVs could be responsible for the progression of ovine cutaneous papillomas to squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) (Vanselow et al., 1982), only recently OaPV3 has been identified in a high number of SCCs in sheep (Alberti et al., 2010). Therefore, this novel virus could represent a key infectious agent in the onset of SCC in ovine species (Alberti et al., 2010; Vitiello et al., 2017). To date, all benign and malignant OaPV-associated tumors have been recorded only in sheep.

In this study, we aimed to provide further evidence of a novel cross-species infection by OaPVs in cattle and to investigate their potential role in bovine bladder carcinogenesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

We did not perform any animal experiments during this study. All samples were collected postmortem from slaughterhouses, and thus, ethical approval was not required.

2.2. Animal samples

During an ongoing research program on chronic enzootic hematuria in cattle, we collected 60 neoplastic bladder samples from public and private slaughterhouses after obtaining permission from medical authorities (manuscript in preparation). Each sample was immediately divided into several parts that were frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent molecular biological analysis, or fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and processed for paraffin embedded for microscopic investigation. Histological assessment of bladder tumors was performed on 5-µm-thick hematoxylin-eosin (HE)-stained sections following the morphological criteria previously suggested for histotype and grading of bladder tumors in cattle (Roperto et al., 2010). After virological assessment of both BPVs and OaPVs, we selected 10 neoplastic bladders that harbored only OaPV infection. Additional bladder samples were collected from healthy cattle. Diseased and healthy cattle shared with sheep grasslands rich in bracken ferns known to contain immunosuppressant substances.

2.3. DNA extraction

Total DNA was extracted from six healthy and 10 neoplastic bladder samples of cattle using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Wilmington, DE, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR)

For ddPCR, (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) QX100 ddPCR System was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction was performed in a final volume of 22 μL containing 11 μL of ddPCR Supermix for Probes (2X; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), 0.9 μM primer, and 0.25 μM probe with 7 μL sample DNA corresponding to 100 ng. The sequences of primers and probes used to verify the presence of BPV and OaPV DNA have been described previously (De Falco et al., 2021; De Falco et al., 2022). The ddPCR mixture was placed in a 96-well 140 PCR plate, and 7 µL of each sample was added to each well (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The plate was then transferred to an automated droplet generator (AutoDG; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). AutoDG added 70 µL of droplet generation oil for the probe in each well, and each sample was partitioned into approximately 20,000 stable nanodroplets. The droplet emulsion (40 µL) was transferred into a new 96 well PCR plate and then coated with a pierceable film that was heat-sealed using a PX1 PCR Plate Sealer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR amplification was performed on a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following thermal profile: hold at 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58°C for 1 min, 1 cycle at 98°C for 10 min, and end at 4 °C. After amplification, the plate was loaded onto a droplet reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and the droplets from each well of the plate were read automatically. The 96-well PCR plate was then placed on the reader. The data were analyzed using the QuantaSoft analysis tool (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Poisson statistics were used to calculate the absolute concentrations of BPV and OaPV DNA in each sample (Pinheiro et al., 2012). A manual threshold line was used to discriminate between positive (blue) and negative (gray) droplets. Therefore, the ddPCR results could be directly converted into copies/µL in the initial samples simply by multiplying them by the total volume of the reaction mixture (22 µL) and then dividing that number by the volume of the DNA sample added to the reaction mixture (7 µL) at the beginning of the assay. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate. Samples with very few positive droplets were reanalyzed to ensure that these low copy number samples were not due to cross-contamination.

2.5. RNA extraction and one-step reverse transcription (RT)-ddPCR

Total RNA was extracted from six healthy and 10 neoplastic bladder samples of cattle infected with OaPVs using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, NW, DE), according to the manufacturer's instructions. This Kit contains genomic DNA (gDNA) Eliminator Spin Columns. One hundred nanograms of total RNA was used for One-Step RT-ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The One-Step was performed both on samples in which the reverse transcriptase was added (RT+) and in those without adding (RT-). The reaction was performed in a final volume of 22 μL, containing 11 μL of ddPCR Supermix 2x for Probes, 2 μL reverse transcriptase, 1 μL DTT, and 1 μL of primer and probe mix (0.9 μM of each primer and 0.25 μM of probe, respectively) for all four delta BPVs and OaPV1, 2, 3, and 4. The sequences of primers and probes used to verify the presence of delta BPV and OaPV transcripts have been described previously (De Falco et al., 2021; De Falco et al., 2022). The plate was transferred to an automated droplet generator (AutoDG, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR amplification was carried out on a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following thermal profile: 50 °C for 60 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 1 min, 1 cycle at 98 °C for 10 min, and end at 4 °C. After amplification, the plate was loaded onto a droplet reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and droplets from each well of the plate were read automatically. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

2.6. Antibodies

Mouse antibody against calpain-1 (previously known as μ-calpain) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Merck, DA, Germany). Rabbit antibody against calpain-2 (previously known as m-calpain) was purchased from Abcam (CA, UK). Rabbit polyclonal anti-PDGFβR and anti-phosphorylated PDGFβR antibodies, as well as mouse antibodies against E2F3 and GAPDH, were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (TX, USA). Mouse anti-retinoblastoma protein (pRb) antibody was obtained from BD Pharmingen (NJ, USA) and anti-phospho-pRb antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA).

2.7. Western blot (WB) analysis

Healthy and pathological bovine bladder samples were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% Triton X-100, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM 178 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1.7 mg/mL aprotinin, 50 mM 179 NaF, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate]. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). For western blotting, 20 μg protein lysate was heated at 90 °C in 4X premixed Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and then, the mixture was clarified via centrifugation, separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, UK). Membranes were blocked with EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in EveryBlot Blocking Buffer. The membranes were washed three times with TBST, incubated for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, diluted 1:5,000 in TBST containing EveryBlot Blocking Buffer, and washed three times with TBST. Immunoreactive bands were detected using Western Clarity Western ECL Substrate or Clarity Max Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and ChemiDoc XRS Plus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Images were acquired using Image Lab Software (version 6.1). WB analyses were performed in duplicate.

3. Results

3.1. Microscopic pattern of the bladder tumors

Histological examination of 10 bladder tumors revealed microscopic patterns consistent with high- and low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, invasive urothelial carcinoma, carcinoma in situ (CIS), squamous cell carcinoma, hemangiosarcoma and capillary hemangioma. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The table reports the histotype of 10 bladder tumors and summarizes the copy number/μL of both DNA and RNA for each of the OaPVs. N = negative.

| Microscopic pattern | OaPV1 E5 |

OaPV2 L1 |

OaPV3 E6 |

OaPV4 E5 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | DNA | mRNA | ||

| 1 | Invasive urothelial carcinoma (UC), high-grade (HG) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.4 | 5 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.6 |

| 2 | Non-invasive papillary UC, HG | 0.4 | 0.1 | 2 | N | 1.5 | 0.8 | N | N |

| 3 | Hemangiosarcoma | 2 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 9 | 1 | N | N |

| 4 | Carcinoma in situ (CIS) | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 3.4 | N | N | N | N |

| 5 | Invasive UC, HG | 2.9 | N | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 | N | 1 | N |

| 6 | Non-invasive papillary UC, low-grade (LG) | N | N | 0.1 | N | 1.8 | 10.5 | N | N |

| 7 | Non-invasive papillary UC, LG and capillary hemangioma | 25.5 | 0.7 | 1.8 | N | 3.6 | 0.5 | 13 | 0.2 |

| 8 | CIS | 0.7 | N | 0.2 | N | 1 | 0.9 | N | N |

| 9 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 0.9 | 0.1 | 2 | N | 1 | N | N | N |

| 10 | Non-invasive papillary UC, LG | N | N | 0.6 | 3.1 | N | N | N | N |

3.2. Virological assessment

All examined bladder samples tested negative for BPV DNA. Only OaPV DNA and mRNA were detected using ddPCR in these 10 neoplastic bladders. OaPV2 was the most prevalent genotype as it was found exclusively or in association with other OaPV types in all bladder tumors. In five samples, OaPV2 was also detected on L1 mRNA level. OaPV1 and OaPV3 were also detected very frequently as they were revealed and quantified in eight of 10 bladder tumors on E5 and E6 DNA and transcript level. OaPV4 DNA was found in three of 10 bladder tumors. OaPV4 E5 mRNA was detected in two samples. Table 1 provides the copy number/μL of both DNA and RNA for each of the OaPVs.

3.3. Molecular findings

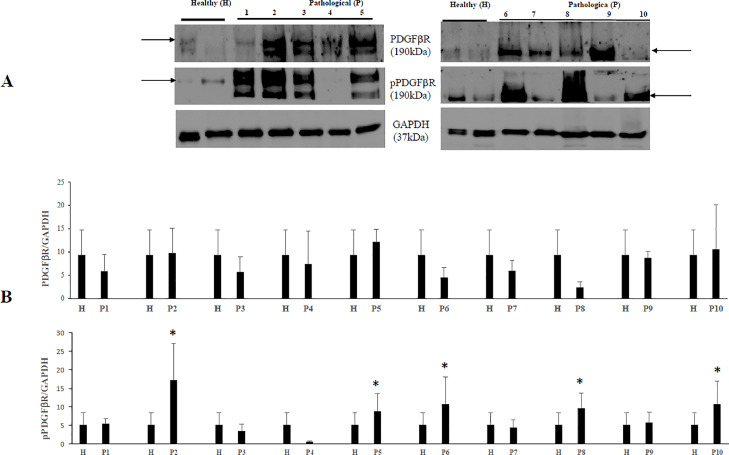

As the activation of PDGFβR is a major transforming pathway of BPVs (Karabadzhak et al., 2017), we investigated whether this receptor is also activated (phosphorylated) by OaPVs. Therefore, we performed WB analysis and found that the amount of total PDGFβR did not show any significant variation in neoplastic bladder cells infected by OaPVs in comparison with urothelial cells from healthy bovine bladders. However, we detected a significant increase of the phosphorylated receptor in some neoplastic bladder cells compared to urothelial healthy cells, which suggest that PDGFβR activation also has a crucial role in molecular pathways of OaPV infection leading to bladder carcinogenesis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PDGFβR and phosphorylated PDGFβR expression levels in bladders of cattle. (A) WB analysis of PDGFβR and activated (phosphorylated) PDGFβR (pPDGFβR) in four healthy and 10 numbered bladder tumors. (B) Densitometric analysis of both proteins was performed relative with the GAPDH protein levels (*p ≤ 0.05). PDGFβR and pPDGFβR bands used for densitometry were indicated by arrows. Plots represent value found in each sample performed in duplicate.

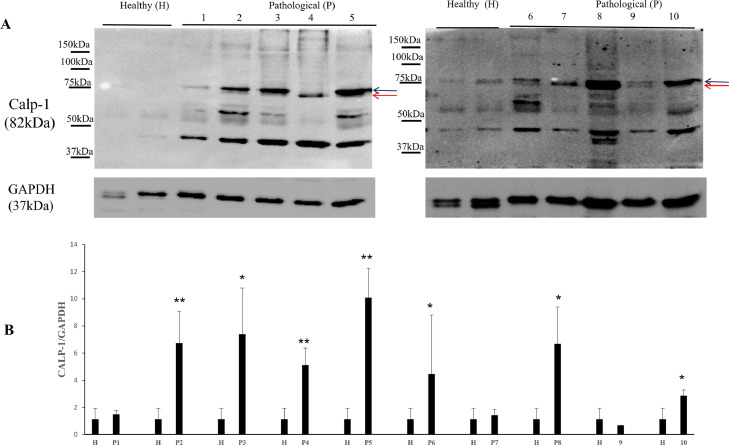

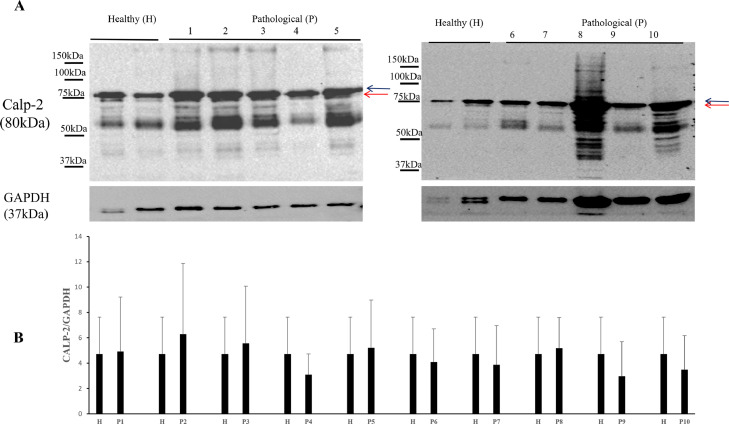

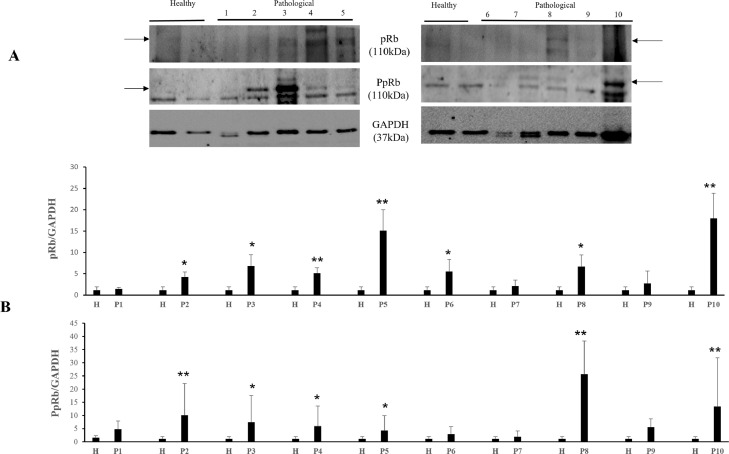

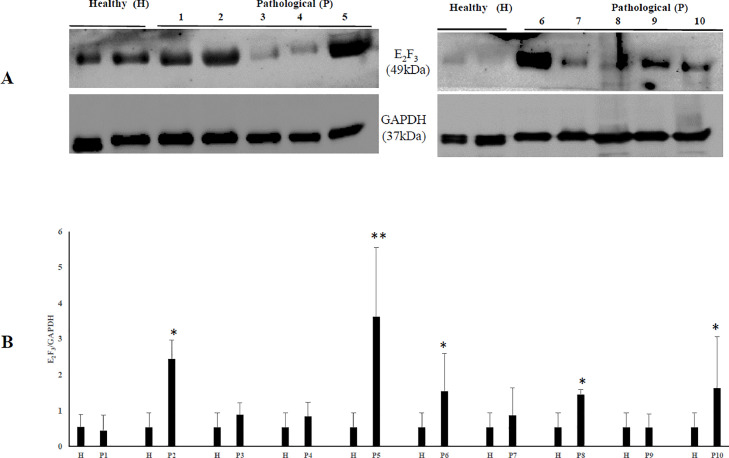

It has been shown that the calpain system is activated in both experimental and spontaneous papillomavirus infections (Roperto et al., 2010; Darnell et al., 2007). Therefore, we investigated the expression levels of calpain-1, and calpain-2. WB analysis revealed a significant overexpression of native and activated calpain-1 in neoplastic bladder cells infected by OaPVs compared to OaPV-negative healthy cells (Fig. 2). Expression levels of calpain-2 appeared to be higher in OaPV-positive cell tumors than healthy cells; however, they did not show any significant variation (Fig. 3). Calpains have a role in the normal cell cycle mainly via pRb phosphorylation (Carragher et al., 2002; Goll et al., 2003). Therefore, we investigated the pRb protein, which is known to bind and repress E2Fs based on its phosphorylation status. WB analysis revealed a significant overexpression of total and phosphorylated pRb in tumor cells infected with OaPVs compared to healthy cells without any OaPV infection (Fig. 4). Then, we investigated the expression of E2F3 because hyperphosphorylation changes the tertiary structure of pRb, thereby releasing and promoting the transcriptional activity of E2Fs (Mendoza and Grossniklaus, 2015). WB analysis revealed a significant overexpression of E2F3 in OaPV-positive tumor cells compared to OaPV-negative healthy cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Calp-1 protein expression in bladders of cattle. (A) WB analysis of calp-1 in four healthy and 10 numbered bladder tumors. Black and red arrows indicate native and activated calp-1 levels, respectively. (B) Densitometric analysis of native and activated calp-1 was performed relative with the GAPDH protein levels (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01). Plots represent value found in each sample performed in duplicate.

Fig. 3.

Calp-2 protein expression in bladders of cattle. (A) WB analysis of calp-2 in four healthy and 10 numbered bladder tumors. Black and red arrows indicate native and activated calp-2 levels, respectively. (B) Densitometric analysis of native and activated calp-2 was performed relative with the GAPDH protein levels. Plots represent value found in each sample performed in duplicate.

Fig. 4.

pRb and phosphorylated pRb (PpRb) expression levels in bladders of cattle. (A) WB analysis of pRb and PpRb in four healthy and 10 numbered bladder tumors. (B) Densitometric analysis of both proteins was performed relative with the GAPDH protein levels (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01). pRb and PpRb bands used for densitometry were indicated by arrows. Plots represent value found in each sample performed in duplicate.

Fig. 5.

E2F3 protein expression in bladders of cattle. (A) WB analysis of E2F3 in four healthy and 10 numbered bladder tumors. (B) Densitometric analysis of E2F3 protein was performed relative with the GAPDH protein levels (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01). Plots represent value found in each sample performed in duplicate.

4. Discussion

To date, OaPVs have been known to infect only ovine species. Recently, it was shown that OaPVs are responsible for a novel cross-species transmission, as their DNA and RNA were found in the blood of healthy cattle (De Falco et al., 2022). It has been suggested that blood infected with PV yields infections at permissive sites with detectable viral DNA and RNA transcripts (Cladel et al., 2019; Syrjänen and Syrjänen, 2021). Virological and molecular findings of this study suggest that OaPVs are associated with bladder carcinogenesis in a species that is not sheep. OaPV DNA and RNA were detected in the neoplastic bladders of cattle that were negative for bovine deltapapillomaviruses. Early genes (E) of papillomaviruses are typically expressed in infected tissues (IARC, 2007). OaPV1, OaPV2, and OaPV4 are fibropapillomaviruses, which represent a clade of closely related papillomaviruses. All fibropapillomaviruses belong to the Deltapapillomavirus genus, which is known to encode the most highly conserved E5 oncoproteins (Van Doorslaer, 2013), probably because of the integration of the E5 open reading frame in the genome of an ancestor of the genus Deltapapillomavirus occurred between 65 and 23 million years ago (Garcia-Vallvé et al., 2005). The E5 oncoprotein of bovine fibropapillomavirus binds to the transmembrane domain (TMD) of PDGFβR, causing dimerization and phosphorylation (activation) of the receptor, resulting in receptor autophosphorylation and initiation of a mitogenic signaling cascade (Karabadzhak et al., 2017). The bovine deltapapillomavirus E5 oncoprotein shares essential residues, namely, Gln17 (Q), Asp33 (D), Cys37, and Cys39 (C) with the E5 oncoprotein of ovine deltapapillomaviruses (Karabadzhak et al., 2017; DiMaio and Petti, 2013). Notably, these residues are important for the binding between E5 and PDGFβR because complex formation and biological activity are crucially dependent on Gln17 and Asp33 of E5 and Lys499 and Thr513 in PDGFβR. We detected a significant increase in phosphorylated (activated) PDGFβR levels in neoplastic bladders in comparison with healthy bladders, which suggests that the E5 oncoprotein of OaPVs may contribute to cell transformation, as reported for most artiodactyl fibropapillomaviruses infecting cells (Munger and Howley, 2002). The molecular findings of the current study suggest that PDGFβR plays an important role in OaPV-mediated molecular pathways that lead to bladder carcinogenesis, similar to how BPVs do.

The oncogenic activity of OaPV3 may be due to the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which are known to immortalize primary sheep keratinocytes, alter cell functionality and induce cell transformation in vitro, deregulating pRb pathway via calpain activation (Darnell et al., 2007; Tore et al., 2019). We detected a significant overexpression and hyperphosphorylation of pRb and a significant overexpression and activation of the calpain-1 in bladder tumors of cattle harboring OaPV transcripts. As no commercial antibodies against OaPV early (E) and late (L) proteins are available, we were unable to investigate the in vivo mechanism(s) involving calpain system in OaPV infection. However, calpain activation may have a role in the molecular pathways of bladder tumors associated with OaPV infection. Our speculation appears to be strengthened by studies on both spontaneous and experimental papillomavirus infections. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is known to activate calpain-1 in cell lines via E7 oncoprotein (Darnell et al., 2007; Tomita et al., 2020). Furthermore, proteomic studies have shown that bovine deltapapillomaviruses can activate calpain-3 in naturally occurring bladder tumors in cattle (Roperto et al., 2010). It has been suggested that pRb hyperphosphorylation is responsible for the release of E2F transcription factors (Darnell et al., 2007). In both human and bovine bladder carcinogenesis, hyperphosphorylation of pRb and release of E2F3 have been shown to occur via calpain system activation and are key events in the molecular pathways leading to urothelial carcinogenesis (Roperto et al., 2010; Olsson et al., 2007; Hurst et al., 2008). Ultimately, the E2F3 overexpression observed in the current study may have been mediated by the calpains that could be activated by OaPV oncoproteins, similar to how HPV and BPV oncoproteins activate calpains. In particular, it is conceivable that the major OaVP-3 transforming proteins, that are known to be E6 and E7 oncoproteins (Tore et al., 2019), are responsible for activation of calpain-1 similar to how HPV E7 oncoprotein does (Darnell et al., 2007). Our study shows, for the first time, that cross-species transmission and infection by papillomaviruses, not belonging to Deltapapillomavirus genus, can occur and that OaPV-3, a Dyokappapapillomavirus, may play a potential role in bladder carcinogenesis of cattle. However, further studies are necessary to better understand the role, if any, of calpains in bladder carcinogenesis of ruminants.

To date, bovine deltapapillomaviruses are the only papillomaviruses responsible for documented cases of natural cross-species infections both in domestic and wild animals being reported in horses, sheep, goats and buffaloes as well as in giraffe, sable antelope and wild ruminants (Roperto et al., 2013; IARC, 2007; Otten et al., 1993; Somvanshi, 2011; Mazzucchelli-de-Souza et al., 2018; Roperto et al., 2018; Cutarelli et al., 2021; van Dyk et al., 2011; Savini et al., 2016). The current study provides further evidence and corroborates a recently reported novel OaPV-mediated cross-species transmission (De Falco et al., 2022).

Close physical proximity and/or sharing grazing lands rich in bracken ferns, which are known to contain strong immunosuppressants, may be an additional prerequisite for PV types to cross host-species barriers, as suggested by the detection of various bovine deltapapillomaviruses in other domestic animals (Cutarelli et al., 2021; de Villiers et al., 2004; Roperto et al., 2021). In our study, cattle infected with OaPVs shared bracken fern-infested highlands with pasture-residing sheep. Therefore, it is conceivable that animal husbandry practices leading to mammalian sympatry facilitate direct and/or indirect contact and may contribute to the cross-species transmission of OaPVs. However, it remains to be determined whether the ability of OaPVs to infect distantly related hosts is putatively linked to husbandry practices of farm animals. Immunosuppressants of bracken coupled with more frequent exposure between sympatric hosts may help OaPVs jump host species, resulting in host switching.

Our study suggests that OaPVs could have a relevant role in bladder carcinogenesis in cattle; however, further studies are needed to determine their oncogenic potential both in sheep and cross-species infections.

As the number of cross-species transmissions continues to increase, the need to understand how papillomavirus transmits within a given species, as well as to new host species, becomes increasingly crucial because the cross-species transmission of viruses from one host species to another is responsible for the majority of emerging infections (Geoghegan et al., 2017). Finally, identification of papillomavirus reservoir is crucial to better understand the viral epidemiology and further research to prevent and control papillomavirus infection, responsible for significant economic losses in cattle industry, including the search for a safe and effective BPV vaccine, is warranted.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Mezzogiorno. The funders of the work did not influence study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Francesca De Falco: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Bianca Cuccaro: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Roberta De Tullio: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Alberto Alberti: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Anna Cutarelli: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Esterina De Carlo: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sante Roperto: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. S. Morace of the University of Catanzaro ‘Magna Graecia', Drs. F. Di Domenico, G. Marino, G. Pizzolante from Azienda Sanitaria Locale (ASL) of Salerno, Dr. R.N. La Rizza from ASL of Vibo Valentia, Dr Marcellino Riccitelli from Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Mezzogiorno, and Dr. A. Russillo from Azienda Sanitaria of Potenza for their technical support.

Data availability

Data are available in the text.

References

- Alberti A., Pirino S., Pintore F., Addis M.F., Chessa B., Cacciotto C., Cubeddu T., Anfossi A., Benenati G., Coradduzza E., Lecis R., Antuofermo E., Carcangiu L., Pittau M. Ovis aries papillomavirus 3: a prototype of a novel genus in the family Papillomaviridae associated with ovine squamous cell carcinoma. Virology. 2010;407:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo M.S., Jarrett W.F.H., Barron R.J., O'Neil B.W., Smith K.T. Association of bovine papillomavirus type 2 and bracken fern with bladder cancer in cattle. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6898–6904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher N.O., Westhoff M.A., Riley D., Potter D.A., Dutt P., Elce J.S., Greer P.A., Frame M.C. v-Src-induced modulation of calpain-calpastatin proteolytic system regulates transformation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:257–269. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.257-269.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho T., Pinto C., Peleteiro M.C. Urinary bladder lesions in bovine enzootic haematuria. J. Comp. Pathol. 2006;134:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cladel N.M., Jiang P., Li J.J., Peng X., Cooper T.K., Majerciak V., Balogh K.K., Meyer T.J., Brendle S.A., Budgeon L.R., Shearer D.A., Munden R., Cam M., Vallur R., Christensen N.D., Zheng Z.M., Hu J. Papillomavirus can be transmitted through the blood and produce infections in blood recipients: Evidence from two animal models. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019;8:1108–1121. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1637072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutarelli A., De Falco F., Uleri V., Buonavoglia C., Roperto S. The diagnostic value of the droplet digital PCR for the detection of bovine deltapapillomavirus in goats by liquid biopsy. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021;68:3624–3630. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell G.A., Schroder W.A., Antalis T.M., Lambley E., Major L., Gardner J., Birrell G., Cid-Arregui A., Suhrbier A. Human papillomavirus E7 requires the protease calpain to degrade the retinoblastoma protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37492–37500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alcântara B.K., Lunardi M., Agnol A.M.D., Alfieri A.F., Alfieri A.A. Detection and quantification of the E6 oncogene in bovine papillomavirus types 2 and 13 from urinary bladder lesions in cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.673189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco F., Corrado F., Cutarelli A., Leonardi L., Roperto S. Digital droplet PCR for the detection and quantification of circulating bovine Deltapapillomavirus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021;68:1345–1352. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Falco F., Cutarelli A., Cuccaro B., Catoi C., De Carlo E., Roperto S. Evidence of a novel cross-species transmission by ovine papillomaviruses. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022;69:3850–3857. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Masi J., Huh K.W., Nakatani Y., Munger K., Howley P.M. Bovine papillomavirus E7 transformation function correlates with cellular p600 protein binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:11486–11491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505322102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers E.M., Fauquet C., Broker T.R., Bernard H.U., zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaio D., Petti L.M. The E5 proteins. Virology. 2013;445:99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vallvé S., Alonso A., Bravo I.C. Papillomaviruses: different genes have different histories. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan J.L., Duchêne S., Holmes E.C. Comparative analysis estimates the relative frequencies of co-divergence and cross-species transmission within viral families. PLOS Pathog. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs C.J., Smale E.P., Lawman M.J. Warts in sheep. Identification of a papillomavirus and transmission of infection to sheep. J. Comp. Pathol. 1975;85:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(75)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll D.E., Thompson V.F., Li H., Wei W., Cong J. The calpain system. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward M.L., Baird P.J., Meischke H.R. Filiform viral squamous papillomas on sheep. Vet. Rec. 1993;132:86–88. doi: 10.1136/vr.132.4.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst C.D., Tomlinson D.C., Williams S.V., Platt F.M., Knowles M.A. Inactivation of the Rb pathway and overexpression of both isoforms of E2F3 are obligate events in bladder tumours with 6p22 amplification. Oncogene. 2008;27:2716–2727. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC . Vol. 90. World Health Organization; Lyon, France: 2007. (Human Papillomaviruses. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabadzhak A.G., Petti L.M., Barrera F.N., Edwards A.P.B., Moya-Rodriguez A., Polikanov Y.S., Freites J.A., Tobias D.J., Engelman D.M., DiMaio D. Two transmembrane dimers of the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein clamp the PDGF β receptor in an active dimeric form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:E7262–E7271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705622114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucchelli-de-Souza J., de Carvalho R.F., Monolo D.G., Thompson C.E., Araldi R.P., Stocco R.C. First detection of bovine papillomavirus type 2 in cutaneous wart lesions from ovines. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:939–943. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros-Fonseca B., Abreu-Silva A.L., Medeiros R., Oliveira P.A., Gil da Costa R.M. Pteridium spp. and bovine papillomavirus: partners in cancer. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.758720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza P.R., Grossniklaus H.E. The biology of retinoblastoma. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2015;134:503–516. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger K., Howley R.M. Human papillomavirus immortalization and transformation functions. Virus Res. 2002;89:213–228. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norval M., Michie J.R., Apps M.V., Head K.W., Else R.E. Rumen papillomas in sheep. Vet. Microbiol. 1985;10:219–229. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(85)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson A.Y., Feber A., Edwards S., te Poele R., Giddings J., Merson S., Cooper C.S. Role of E2F3 expression in modulating cellular proliferation rate in human bladder and prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:1028–1037. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten N., von Tscharner C., Lazary S., Antczak D.F., Gerber H. DNA of bovine papillomavirus type 1 and 2 in equine sarcoids: PCR detection and direct sequencing. Arch. Virol. 1993;132:121–131. doi: 10.1007/BF01309847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamukcu A.M. Tumours of the urinary bladder. Bull. World Health Organ. 1974;50:43–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamukcu A.M., Price J.M., Bryan G.T. Naturally occurring and bracken-fern-induced bovine urinary bladder tumors. Clinical and morphological characteristics. Vet. Pathol. 1976;13:110–122. doi: 10.1177/030098587601300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PaVE: The papillomavirus episteme available from http://pave.niaid.nih.gov (accessed 20 December 2022).

- Pinheiro L.B., Coleman V.A., Hindson C.M., Herrmann J., Hindson B.J., Bhat S., Emslie K.R. Evaluation of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:1003–1011. doi: 10.1021/ac202578x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A.S., Pereira T.N., Smith B.L., Shaw G., Seawrigth A.A. Mechanism of bracken fern carcinogenesis: Evidence for H-ras activation via initial adenine alkylation by ptaquiloside. Nat. Toxins. 1996;4:221–227. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)(1996)4:5<221::AID-NT4>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., Borzacchiello G., Brun R., Leonardi L., Maiolino P., Martano M., Paciello O., Papparella S., Russo V., Salvatore G., Urraro C., Roperto F. A review of bovine urothelial tumours and tumour-like lesions of the urinary bladder. J. Comp. Pathol. 2010;142:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2009.08.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., Cutarelli A., Corrado F., De Falco F., Buonavoglia C. Detection and quantification of bovine papillomavirus DNA by digital droplet PCR in sheep blood. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:10292. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89782-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., De Tullio R., Raso C., Stifanese R., Russo V., Gaspari M., Borzacchiello G., Averna M., Paciello O., Cuda G., Roperto F. Calpain3 is expressed in a proteolytically active form in papillomavirus-associated urothelial tumors of the urinary bladder in cattle. PLOS One. 2010;5:e10299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., Di Guardo G., Leonardi L., Pagnini U., Manco E., Paciello O., Esposito I., Borzacchiello G., Russo V., Maiolino P., Roperto F. Bacterial isolates from the urine of cattle affected by urothelial tumors of the urinary bladder. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012;93:1361–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., Russo V., Borzacchiello G., Urraro C., Lucà R., Esposito I., Riccardi M.G., Raso C., Gaspari M., Ceccarelli D.M., Galasso R., Roperto F. Bovine papillomavirus type 2 (BPV-2) E5 oncoprotein binds to the subunit D of the V1-ATPase proton pump in naturally occurring urothelial tumors of the urinary bladder of cattle. PLOS One. 2014;9:e88860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., Russo V., Corrado F., De Falco F., Munday J.S., Roperto F. Oral fibropapillomatosis and epidermal hyperplasia of the lip in newborn lambs associated with bovine Deltapapillomavirus. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13310. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31529-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roperto S., Russo V., Ozkul A.V., Corteggio A., Sepici-Dincel A., Catoi C., Esposito I., Riccardi M.G., Urraro C., Lucà R., Ceccarelli D.M., Longo M., Roperto, F F. Productive infection of bovine papillomavirus type 2 in the urothelial cells of naturally occurring urinary bladder tumors in cattle and water buffaloes. PLOS One. 2013;8:e62227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savini F., Dal Molin E., Gallina L., Casà G., Scagliarini A. Papillomavirus in healthy skin and mucosa of wild ruminants in the Italian Alps. J. Wildl. Dis. 2016;52:82–87. doi: 10.7589/2015-03-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubbert S., Shannon K., Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somvanshi R. Papillomatosis in buffaloes: a less-known disease. Tansbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011;58:327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2011.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrjänen S., Syrjänen K. HPV-associated benign squamous cell papillomas and in the upper aero-digestive tract and their malignant potential. Viruses. 2021;13:1624. doi: 10.3390/v13081624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook P.A., Sterrett G., Kulski J.K. Detection of papillomaviral-like DNA sequences in premalignant and malignant perineal lesions of sheep. Vet. Microbiol. 1992;31:327–341. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90125-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita T., Huibregtse J.M., Matouschek A. A masked initiation region in retinoblastoma protein regulates its proteasomal degradation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X., Howley P.M. The bovine papillomavirus E6 oncoprotein interacts with paxillin and disrupts the actin cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:4412–4417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tore G., Cacciotto C., Anfossi A.G., Dore G.M., Antuofermo E., Scagliarini A., Burrai G.P., Pau S., Zedda M.T., Masala G., Pittau M., Alberti A. Host cell tropism, genome characterization, and evolutionary features of OaPV4, a novel deltapapillomavirus identified in sheep fibropapilloma. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;204:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tore G., Dore G.M., Cacciotto C., Accardi R., Anfossi A.G., Bogliolo L., Pittau M., Pirino S., Cubeddu T., Tommasino M., Alberti A. Transforming properties of ovine papillomaviruses E6 and E7 oncogenes. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;230:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenfield K., Spradbrow P.B., Vanselow B.A. Detection of papillomavirus DNA in precancerous lesions of the ears of sheep. Vet. Microbiol. 1990;25:103–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90070-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzal F.A., Latorraca A., Ghoddusi M., Horn M., Adamson M., Kelly W.R., Schenckel R. An apparent outbreak of cutaneous papillomatosis in merino sheep in Patagonia, Argentina. Vet. Res. Commun. 2000;24:197–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1006460432270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer K. Evolution of the Papillomaviridae. Virology. 2013;445:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dyk E., Bosman A.M., van Wilpe E., Williams J.H., Bengis R.G., van Heerden J., Venter E.H. Detection and characterization of papillomavirus infection in skin lesions of giraffe and sable antelope in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2011;82:80–85. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v82i2.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanselow B.A., Spradbrow P.B., Jackson A.R.B. Papillomaviruses, papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas in sheep. Vet. Rec. 1982;110:561–562. doi: 10.1136/vr.110.24.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello V., Burrai G.P., Pisani S., Cacciotto C., Addis M.F., Alberti A., Antuofermo E., Cubeddu T., Pirino S. Ovis aries papillomavirus 3 in ovine cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Vet. Pathol. 2017;54:775–782. doi: 10.1177/0300985817705171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article

Data are available in the text.