Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the scientific literature examining parents' experiences and information needs for the management of their child's asthma exacerbations.

Methods

We searched five databases for quantitative and qualitative studies in Canada and the United States from 2002 onwards. A convergent integrated approach and the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool were used to analyze and appraise the evidence, respectively.

Results

We included 84 studies (27 quantitative, 54 qualitative, 3 mixed methods). Some parents lacked confidence in recognizing or managing exacerbations. A few parents were uncertain when and where to seek medical help. The main barrier to accessing care was cost. Impacts on parents included poor sleep, distress, and lifestyle disruptions. Parents felt they lacked information and wanted education on treatments and how to recognize and manage exacerbations via education sessions, written materials, community outreach and online resources.

Conclusion

Improved education for parents may help reduce parents' stress, asthma-related morbidities for children and use of urgent health services.

Innovation

The development of tailored interventions and knowledge translation strategies with input from target audiences (e.g. parents, health care providers) is necessary to meet their information needs and support adherence to clinical recommendations.

Keywords: Asthma exacerbation, Parents, Experiences, Information needs, Systematic review

Highlights

-

•

84 studies reviewed and analyzed using the convergent integrated approach

-

•

Parents lacked confidence in recognizing, treating or seeking care for exacerbations

-

•

Cost was a barrier to care; parents affected by psychosocial impacts

-

•

Parent's desired education on treatments and how to recognize and manage exacerbations

-

•

Interventions and knowledge translation strategies must be developed with parents

1. Introduction

The prevalence of asthma in children is increasing globally [1,2], and is now the most common chronic disease in children [3]. In North America, asthma is one of the most common reasons for emergency department (ED) visits for children aged 1-17 years [4,5]. Asthma places an immense burden on families, health systems and economies [6,7] and, with the rising prevalence, there is a marked demand on health services for treatment of asthma exacerbations.

Asthma exacerbations are acute episodes of shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, or a combination of these symptoms, that become increasingly worse and make breathing difficult [8]. Despite the development of evidence-based guidelines on the prevention and treatment of asthma exacerbations, [[9], [10], [11]] asthma-related morbidity rates [1] and health services utilization [11] for children remains high. This, in part, may be due to non-adherence with the guidelines at home.

Management of asthma exacerbations in children is complex: it requires that parents and caregivers have sufficient knowledge of the pathophysiology, symptoms, treatment regimens and best preventative practices for the disease [12]. Comprehensive education for parents is therefore essential to equip parents with the knowledge and resources needed to effectively prevent and treat acute asthma exacerbations. Unfortunately, gaps in the education process persist. A previous state-of-the-science review found that North American parents' information needs are often not met [13]. The review suggested that inadequate information and education may lead to increased parental fear and anxiety, insufficient management of symptoms, and improper use of health care resources [13].

One step to optimizing the care of pediatric patients, and helping parents understand how best to manage their child's asthma exacerbations, is to develop knowledge translation (KT) tools (e.g., infographics, videos, eBooks, etc.) for parents [14]. To guide the development of these KT tools, we conducted a mixed studies systematic review to explore parents' self-reported experiences and information needs related to their child's acute asthma exacerbations.

2. Methods

2.1. Review conduct

We followed an a priori protocol registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019145746), and reported any deviations from the protocol in Appendix 1. Findings are reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Material 1) [15].

2.2. Search strategy

We developed the search strategy (Supplementary Material 2) in collaboration with a medical research librarian, who implemented the search. Search terms combined subject headings and keywords for asthma, parents, experiences and information needs. The following databases were searched in December 2019 for relevant studies conducted in North America and indexed from January 2002: Ovid Medline (1946 to present), Ovid PsycINFO (1987 to present), CINAHL Plus via EBSCOhost (1937 to present), and the Cochrane Library. We also searched ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global to identify grey literature and hand searched the reference lists of all included studies and any relevant reviews and overviews to identify additional relevant records. We uploaded our search results to EndNote reference management software (v. X9, Clarivate Analytics) and removed duplicates.

2.3. Study selection

All records were transferred to Microsoft Office Excel (v. 2016, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) and screened by one reviewer. Full texts were retrieved for any ‘include’ or ‘unsure’ citations and underwent further assessment for eligibility. Excluded studies from the title/abstract and full-text screening stages were further screened by a second reviewer for verification. Given the large volume and diversity of records, excluded studies were verified by two reviewers during both stages of screening, and the final eligibility of included studies was verified by two reviewers once the breadth of results was better understood. Any reviewer disagreements were resolved via a third reviewer.

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Appendix 2. To be included, studies had to report on outcomes related to parents' or caregivers' (e.g. grandparents, legal guardians) self-reported experiences or information needs concerning their child's asthma exacerbations, be published after 2002 and in English. These restrictions were used to ensure that our results were congruent with present day treatment guidelines and information seeking behaviours of parents in Canada and the USA. The language restriction was not expected to impact the results or conclusions of the systematic review, particularly with our focus on Canadian and American studies [16]. We considered events and circumstances immediately before (e.g. early warning signs), during and following (e.g. experiences in the ED or hospital) an exacerbation to be relevant. We described experiences as events or circumstances that happen to a person, including social cognitive (e.g. attitudes and beliefs), demographic (e.g. culture) or emotional (e.g. perceptions and feelings) factors; actions a person takes; and the extent to which a person's needs have been met [17]. Parent information needs were defined as the type, quantity and mode of delivery of information that parents needed or desired in relation to the management of their child's asthma exacerbations [18,19].

2.4. Data extraction

One reviewer extracted data from each included record using a form developed by the research team (Microsoft Excel, 2016) and a second reviewer verified the extracted data for accuracy and completeness. Any disagreements were resolved via consensus.

We collected data on study (author(s), publication year, funding source(s), design, setting), population (inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, age and gender of children and parents, other sociodemographic factors), and outcome (parent-reported experiences and information needs) characteristics for quantitative, qualitative and mixed studies. Quantitative outcome data were extracted directly into Microsoft Office Excel. Qualitative outcomes (interpretations identified as ‘findings’ or ‘results’ by the study authors) were transferred verbatim to NVivo software (v.10; QSR International; Melbourne, Australia).

2.5. Quality assessment

We appraised the methodological quality of all included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Supplementary Material 3) [20,21]. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of each included study and provided justification for their decisions with a comment or direct quote from the study. Disagreements were resolved via third party adjudication. We did not exclude studies based on quality assessment scores so as to provide a comprehensive representation of parent-reported experiences or information needs related to their child's asthma exacerbations.

2.6. Data synthesis and interpretation

Our research question could be addressed by both quantitative and qualitative research designs. Therefore, in accordance with the 2020 Joanna Briggs Institute methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews, a convergent integrated approach was used where quantitative and qualitative evidence were integrated through data transformation and analyzed together [22]. Quantitative results were converted into “qualitized data” by transforming the data into textual descriptions or narrative interpretation. This step was completed by one reviewer experienced in qualitative and mixed methods analyses (JSK) and confirmed by a second review with extensive experience in both forms of analyses (SE). Qualitative results were analyzed thematically using NVivo software. One reviewer (JSK) inductively coded the relevant text line-by-line, applying one or more codes according to its meaning and content (capturing the essence of the data). Codes were then sorted and organized into analytical categories and themes [23]. To reduce the risk of interpretive biases, a second reviewer (SE) reviewed the preliminary codes and confirmed the emergent themes. All data were then categorized and pooled together based on similarity in meaning to produce a set of integrated findings.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

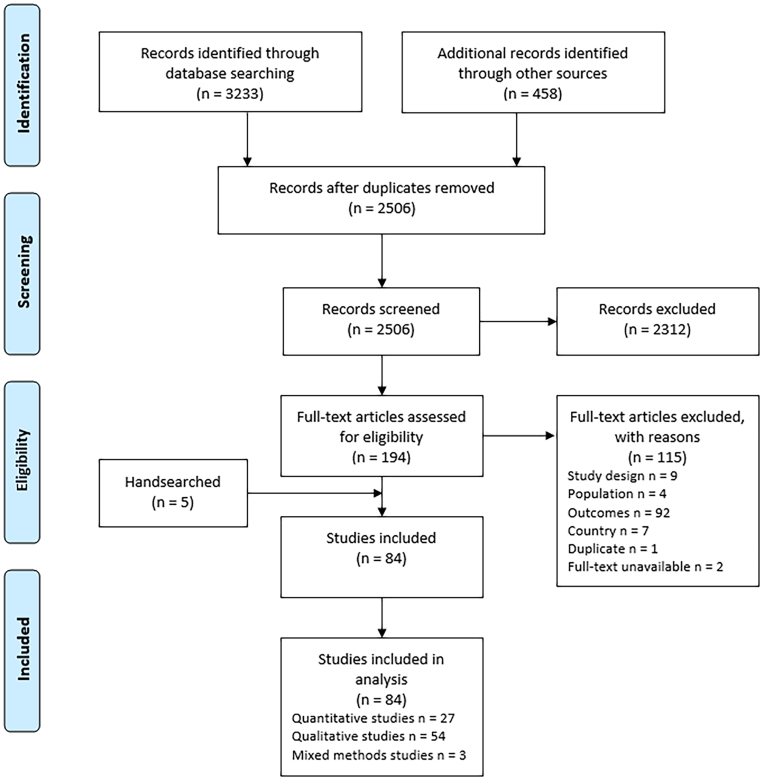

Fig. 1 shows the flow of studies through the selection process. We identified 2506 unique records, assessed the full-text of 194 studies and included 84 [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107]].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for study inclusion.

3.2. Study characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1 and detailed in Supplementary Material 4. Studies were categorized (based on extracted data) as quantitative descriptive (n = 19), quantitative non-randomized (n = 8), qualitative (n = 54) and mixed methods (n = 3). The mean year of publication was 2010 and the majority of studies (n = 81, 96%) took place in the USA, and three (4%) studies took place in Canada. Data on self-reported experiences and information needs were available from approximately 8466 parents (median 22, IQR 12 to 85) via semi-structured individual interviews, surveys and rating scales, focus groups and analysis of online posts or phototexts. When reported, the majority of parents were mothers (mean 89%, based on 3204 participants in 53 studies) and the weighted mean age was 36.1 years (based on 1041 participants in 26 studies).

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of the 84 included studies reporting on parent-reported experiences and information needs regarding their child's acute asthma exacerbations.

| Study Design | Method | Country | Study Setting (recruitment) | Parents |

Children |

Key Outcomes (n studies) | MMAT Score, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean N (Range) | Mean Age, (Range) (years) | Mean N (Range) | Mean Age, (Range) (years) | ||||||

| Quantitative descriptive, n = 19 studies | Surveys n = 18, Case series n = 1 |

USA n = 18, Canada n = 1 |

ED n = 8, Primary care and health centers n = 5, Community n = 5, Inpatient hospital unit n = 1 |

160 (48-278), NR 2 studies | 35.6 (22-64), NR 14 studies | 175 (48-530) | 8.4 (0.6-18.2), NR 7 studies | Access and barriers n = 7, Point of care decisions for seeking help n = 5, Type of information wanted n = 5, Emotional and personal impacts n = 4, Treatments/strategies used n = 4, Confidence in managing symptoms n = 2, Sources of information n = 2, Decision to seek care n = 1, Information seeking behaviours and decision-making preferences n = 1 |

100: 6 (31.6%), 80: 4 (21.1%), 60: 5 (26.3%), 40: 4 (21.1%) |

| Quantitative non-randomized studies, n = 8 studies | Cross-sectional analytic studies n = 7, Retrospective cohort n = 1 |

USA n = 8 | Community n = 2, Research center n = 2, Multiple settings n = 2, Primary care and health centers n = 1, National database n = 1 |

554 (85-2535) | 38.9 (19-69), NR 6 studies | 614 (27-3104) | 10.3 (0-18), NR 3 studies | Emotional and personal impacts n = 7, Decision to seek care n = 1; Point of care decisions for seeking help n = 1 |

80: 5 (62.5%), 60: 3 (37.5%) |

| Qualitative studies, n = 54 | Qualitative description n = 25, Grounded theory n = 11, Phenomenology n = 10, Ethnography n = 5, Qualitative case study n = 1, Interpretive description n = 1 |

USA n = 52, Canada n = 2 |

Community n = 23, Primary care and health centers n = 14, Multiple settings n = 7, ED n = 4, Health databases n = 2, Inpatient hospital unit n = 2, Online groups n = 2 |

28 (4-435), NR 1 study | 34.8 (16-74), NR 35 studies | 22 (3-215), NR 15 studies | 8.1 (0-18), NR 39 studies | Emotional and personal impacts n = 35, Treatments/strategies used n = 35, Decision to seek care n = 32, Experiences and interactions with HCPs n = 24, Lack of information and knowledge gaps n = 25, Confidence in recognizing symptoms and unpredictability of exacerbations n = 21, Sources of information n = 20, Confidence in managing exacerbations n = 19, Point of care decisions for seeking help n = 16, Access and barriers to equipment and health care n = 13, Preferences of mode of information delivery n = 9, Information seeking behaviours and decision-making preferences n = 7, Type of information wanted n = 4 |

100: 41 (75.9%), 80: 7 (13.0%), 60: 4 (7.4%), 40: 2 (3.7%) |

| Mixed methods studies, n = 3 | Convergent design n = 2, Sequential explanatory design n = 1 |

USA n = 2 | Primary care and health centers n = 3 | 39 (22-50) | 39.1 (26-58), NR 2 studies | 39 (22-50) | 11.4 (2-17), NR 1 study | Access and barriers to equipment and health care n = 2, Confidence in managing exacerbations n = 2, Decision to seek care n = 2, Emotional and personal impacts n = 2, Information seeking behaviours and decision-making preferences n = 2, Lack of information and knowledge gaps n = 2, Experiences and interactions with HCPs n = 1, Point of care decisions for seeking help n = 1, Treatments/strategies used n = 1 |

80: 1 (33.3%), 0: 2 (66.7%) |

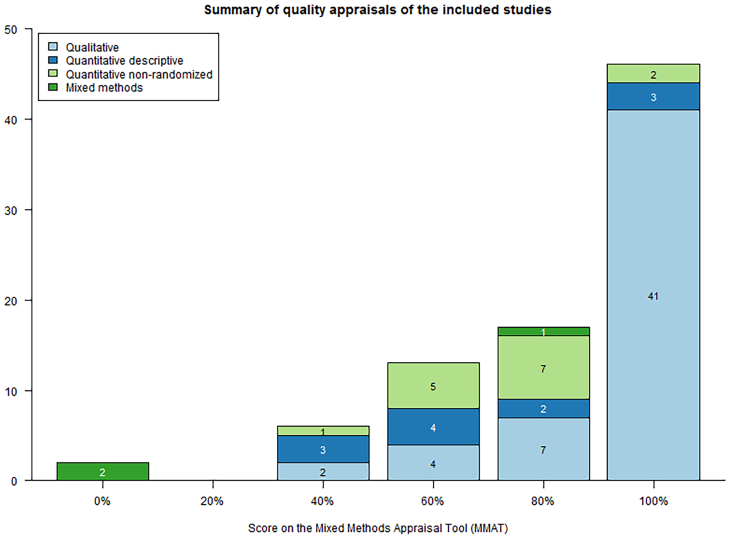

3.3. Quality appraisal

The majority of included studies were of good quality and met at least 80% of the MMAT criteria (Fig. 2). Sixty-three studies (75%) met 80% or 100% of the MMAT criteria, thirteen met 60%, six met 40% and two met 0%.

Fig. 2.

Summary of quality appraisals of the included studies.

3.4. Study findings

We organized our findings by outcomes of interest. First, we present parents' experiences, followed by their information needs. Our findings from the quantitative and qualitative studies are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of quantitative findings reported in included studies.

| Outcome | Contributing studies | % MMAT criteria met, median (range) | N parents; median (range) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiences | ||||

| Ability to recognize exacerbation symptoms | 1 Descriptive | 100% | 198 | Most parents were confident or very confident in identifying when the child needed his/her medications and when to manage the child's asthma at home or to go to the physician (n = 1 study) [104]. |

| Treatments/strategies used at home | 5 Descriptive 2 Mixed method 1 Cohort |

70% (0% to 100%) | 168.5 (22 to 229) |

Most parents were confident in treating their child's exacerbations (n = 3 studies) [43,53,104] but some worried about not being able to help their child feel better (n = 1) [84]. Parents treated their child's exacerbations at home using a prescription bronchodilator and anti-inflammatory medications (n = 3) [27,34,66], over-the-counter medications (n = 3) or other home remedies and CAM therapies (n = 3) [24,27,66]. Some parents did not use at-home treatments for their child's asthma exacerbation (n = 2) [27,66]. Some parents were concerned about the effects of medications used to treat asthma exacerbations (n = 1) [25]. |

| Seeking health care | 6 Descriptive 2 Mixed method 1 Cross-sectional |

80% (0% to 100%) | 150 (50 to 234) |

Parents sought asthma care from a variety of sources including primary care providers (PCP; i.e., family doctor, health clinics), medical specialists or specialty clinics (pulmonologist, allergist, etc.), and the ED or hospital (n = 5 studies). The majority of parents in 3 of 4 studies did not contact the PCP prior to attending the ED [37,38,47,54]. Parents decided to take their child to the ED within 12 h of symptoms starting (n = 1) [38], when symptoms became urgent (n = 2) [54,74], or after at-home treatment failed (n = 1) [74]. |

| Access and barriers to equipment and health care | 9 Descriptive 2 Mixed method 1 Cross-sectional |

80% (0% to 100%) | 199 (22 to 530) |

Most families have spacers and nebulizers (n = 2 studies) [68,74] and parents were confident in their use (n = 1) [104]. Some families did not have a spacer device for school or ran out of medication (n = 1) [37]. At-home peak flow meters were less common and rarely used (n = 1). Most families could easily access care for their child's asthma (n = 5) [39,47,54,66,68], including being able to identify a primary asthma care provider (n = 2) [66,68] and book appointments on short notice (n = 2) [54,66]. Parents who delayed care were more likely to visit the ED (n = 1) [90]. Some parents delayed or did not seek care or obtain prescription medications because of worries about cost (n = 5) [47,53,67,69,90], especially when they did not have medical insurance (n = 2) [47,67]. Other barriers included difficulty or inconvenience making an appointment (n = 3) [67,69,90], difficulties travelling to the clinic (n = 2) [69,90], waiting times (n = 2) [69,90], a language barrier (n = 1) [67], fear (n = 1) [67], and lack of supplies at the clinic (n = 1) [67]. |

| Emotional and personal impacts on parents | 5 Cross-sectional 2 Mixed method 1 Cohort 4 Descriptive |

60% (0% to 80%) | 117.5 (27 to 2535) |

Many parents experienced disrupted or poor-quality sleep due to their child's night-time asthma symptoms (n = 6 studies) [54,67,68,71,91,93]. Their child's asthma made parents feel helpless or frightened (n = 5) [25,46,67,84,93], worried (n = 2) [67,84], upset (n = 2) [25,67], and frustrated/impatient (n = 1) [93]. Parents feared for their child's life during an exacerbation (n = 1) [93]. A child's asthma interfered with a parents' household work or employment (n = 5) [42,54,68,84,93], especially when their child's asthma was not well controlled (n = 1) [42]. Families sometimes changed plans because of a child's asthma (n = 1) [67], and some families experienced a traumatic event relating to their child's asthma (n = 1) [61]. |

| Information Needs | ||||

| Lack of information and knowledge gaps | 1 Cohort 1 Descriptive 1 Mixed method |

80% (40% to 100%) | 139 (45 to 225) |

Most parents received some level of asthma education (n = 3 studies) [27,34,84] but it was not always complete (n = 2) [27,34]. Some parents found the information difficult to understand and desired more help or support in understanding information about asthma (n = 1) [84]. |

| Type of information wanted | 4 Descriptive 1 Cross-sectional |

100% (40% to 100%) | 225 (83 to 278) |

Parents wanted to learn more about how to manage their child's asthma (n = 5) [27,43,51,66,107], including the differences between rescue and controller medications (n = 2) [43,51], proper medication administration (n = 1) [66], and CAM therapies for asthma (n = 1) [27]. Parents also wanted more information about how to identify an asthma exacerbation (n = 1) [66], and what to do or when to seek care in case of an exacerbation (n = 2) [27,107]. |

| Sources of information | 3 Descriptive | 60% (60% to 100%) | 76 (66 to 200) |

Parents sourced information on asthma from health care providers, other sources, or both (n = 3 studies) [24,66,79]. |

| Information seeking and decision-making preferences | 1 Descriptive 1 Mixed method |

20% (0% to 40%) | 50 (22 to 77) | Parents wanted as much information as possible, even if the news was bad, and especially if their child's condition worsened. Parents felt that physicians should make decisions about the child's medical care, especially if the child was hospitalized. [58] WAAPs: Most parents would find a WAAP useful, but only half of parents knew what a WAAP was. WAAPs were difficult for parents to understand because the information was too dense and technical language was used. Adding pictures/graphics and training healthcare providers on how to use and educate parents on WAAPs would make WAAPs more useful to parents. [53] |

Abbreviations: CAM = Complementary and Alternative Medicine; ED = Emergency Department; PCP = Primary Care Provider; WAAP = Written Asthma Action Plan

Table 3.

Summary of the qualitative findings reported in included studies.

| Primary theme | Subtheme | Representative quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Experiences | ||

|

|

“[T]hey’re both so young right now that I don’t trust that they can report to me accurately. She gets scared and that scares me, because I wonder if it’s more severe than what I’m recognizing because she can’t share it with me accurately.” [41] |

|

“[An asthma exacerbation] comes on so fast that it’s scary. It’s scary for me to deal with it.” [85] | |

|

“I guess, really, my fear is that maybe I won't pick up one of the symptoms or like some of the symptoms... because sometimes it's like he does breathe in heavier...but is it just because that's how he's breathing or is it because he's getting ready to have an attack?” [98] “I’ve become very good at treating it and hearing it, before it comes.” [35] |

|

|

|

“For me, it was really difficult because I did not feel very capable to be able to help him...” [84] “[H]e gives me the signs and normally I can give him a treatment or I can give him the inhaler and take care of it.” [52] |

|

“All participants, except one, reported administering prescribed medical treatment (medication, aerosol treatment) for effective relief from respiratory distress.” [60] “This is for the machine [showing albuterol]. They also give it to her in liquid but I give it away, I don’t use it.” [30] “[O]ne mother expressed the desire to withhold necessary medications to prevent her child from becoming hyper. ‘I don't even want to try, if we give him Albuterol it’s just 10 times that up, and then his attitude and everything else!’” [98] |

|

|

“The most common Hawaiian healing practices were prayer, pōpolo (Solanum nigrum) berries, and lomi (body massage) to back and chest to help relax the child during an asthma attack…” [60] “[F]amilies sought traditional healing in order to ‘get well’ and ‘be cured’. By contrast, biomedical therapies were reported to only suppress symptoms of asthma that would likely reappear.” [97] “A lot of people have told me about [alternative] medications for asthma but I don’t dare to give them to him [her grandson], he’s already taking so many medications, I don’t want him to have any complication.” [49] |

|

|

“Sit them down. Calming them down. That works. Letting them breathe in and out, that works.” [70] | |

|

“I just wait and see. I don’t give him his inhaler or... none of his medications at first, because I just kind of want to wait and see if his own body, you know, his own immune system will boot it out and will take care of it.” [49] | |

|

|

“Parents coped with recurrent and escalating crises of difficult breathing by seeking care from providers in doctors’ offices, clinics, and hospital emergency rooms.” [62] “[P]arents were concerned about the quality of advice and lack of familiarity with the problems of the individual child” at the ED. [48] “I still prefer bringing her to this ER [emergency room] because here there is more attention to what she has, better than at the pediatrician. There she only gets treatments to go home.” [87] |

|

“I looked for the spray and gave it to her according to the instructions, and waited for a while, about half an hour and she was still the same, so what I did is that I took her to the hospital” [33] “[Y]ou know when stuff like that happens they [ED staff] take you in right away, so we didn’t have to stress out about waiting to see the doctor.” [26] |

|

|

“I know there are great doctors and they take care of him right away.” [40] “My child looked bad to me. The nurse knows more than me, I don’t know anything, so then I was thankful.” [87] “Well the most difficult is to see him [my child] there [in the emergency room] without knowing what to do.” [33] “They were putting things on and I did not know what they were giving him. Because I did not understand them. They tried to tell us. Later they told us but in that moment no.” [87] “Ruby recalled her conflicted feelings when the respiratory therapist gave Reggie a breathing treatment. She wanted to cooperate with optimum treatment for Reggie’s asthma but she could not endure standing by while he cried.” [65] “You feel frustration, fury, anger, and you feel like grabbing the doctor and telling him, ‘Look, tell me something I can understand.’ But he’s telling me something strange and I cannot understand, and that makes it worse.” [83] “Parents overcame language barriers with the assistance of others (i.e., interpreters, translators, Spanish-speaking community members, or children themselves) to mediate communication when coordinating children’s care.” “[S]ometimes I don’t agree with some of the doctors calls.” [31] “The uncertainty of the wait time seemed to add stress; ‘you know, just the waiting and how soon they’re going to get here [in the room in the ED] to give him the treatment.’” (Coffey 2012) “One caregiver reported her frustration and anger with the healthcare system due to the “damage” caused when her child was not promptly diagnosed: That was before they even gave her the diagnosis. …She was in there [the ED], may be [sic] once a week for 27 weeks.” [50] “One time we had waited hours [in the ED]. And he still wasn't being seen. And he was wheezing and breathing very fast. I got loud and told the nurses and doctors that he had asthma, not bronchitis and that he needed to be seen right away. They took him right away.” [63] “[The ED doctors] read stuff slow to you or they look at you strange and it’s just not very helpful. It’s like, because you’re Indian, or whatever you might be, that you don’t know anything.” [85] “[Parents] expressed appreciation for the physician’s accessibility, general interest in their children, and the respect that the physicians had for the caregiver’s concerns and suggestions for care.” [41] |

|

|

|

“Finances directly and indirectly affected parents’ adaptation challenges. One financial difficulty included private insurances not covering the cost of nebulizer equipment.” [59] |

|

“When we came to this country all the medications were covered by the medical plan. But in Puerto Rico, the Pulmicort and the albuterol was not covered anymore by the medical plan, and they were extremely high costly [sic]. We have to get help from family members…” [75] | |

|

“[Y]ou don’t have transportation, and if your current medical supplier doesn’t supply a cab for you, how are you going to get down there? You don’t want to call 911 because that ambulance ride is going to cost you $300…” [85] | |

|

|

“[S]he was just like she was going out of it. I was like, Oh Lord, she’s fixing to go. I was so scared.” [36] |

|

“It’s a lot of stress. A lot of not going to sleep. Lot of worry...when she is sick we don’t sleep.” [50] “And it’s really stressful to have to get up some times at 3, 4 o’clock in the morning, get the other kids up or try to get someone to come sit with them or haul them to the neighbors at 3 o’clock in the morning to take her to the ER [emergency room].” [85] |

|

|

“African American and Hispanic parents expressed feeling worried about the impact of work absences due to asthma appointments or emergencies and inflexible work policies employment [sic] on their abilities to maintain employment.” [102] | |

|

“In subsequent days and months, their own accustomed routines of eating, sleeping, and bathing fell away. All felt caught up in frightening circumstances over which, at best, they had tenuous control.” [62] “He [child's father] was fearful. So he kind of left it up to me.” [50] |

|

| Information Needs | ||

|

|

“I’ve not gotten any education about asthma through the doctors. None whatsoever. All they do is say, ‘Here you go. Take this (medication).’ And on your merry way.” [60] “I can’t even articulate what I think I should know right now … or what I would like some help with.” [26] |

|

“Well, [asthma] might have been explained sufficiently, but I don’t think I’ve grasped a total understanding of it that maybe I should have” [35] | |

|

“I think sometimes it can be the doctors or nurses, respiratory… and it’s just like one person can say this, then the next moment, somebody else is saying this, and sometimes make you a little confused.” [86] | |

|

“[The health care provider] provided me with the information that I wanted and, yeah it’s been good so far” [26] | |

|

|

“[I]f they [health providers] could give them [parents] a pamphlet for asthma saying, you know, you need to watch the reps (respirations) and tell them- show them how to check the reps.” [88] |

|

“I want to know what they’re going to do. I want to see what they’re doing because I feel like, if they’re going to do something different I want to be there to see. So if I have to do it at home, I’ll know what to do…” [64] | |

|

“The majority of the caregivers felt the need to know all they could about the medications. They would give their children the medication, but wanted to know side effects, possible interactions, and exactly what part of the asthma it treated.” [50] | |

|

“Parents voiced willingness to learn more about the Medicaid system, to better maneuver and advocate for their child’s care, but were unsure where to get such information.” [96] | |

|

“Five participants expressed avid interest in learning more about traditional healing practices.” [59] | |

|

|

“All caregivers described collaborative relationships with their children’s primary physicians and with the allergists and pulmonologists. They sought guidance in the initial diagnostic stage, for ongoing preventive treatment, and for managing asthma attacks.” [41] |

|

“[W]ithout a diagnosis from professionals, [the parents] sought advice from friends and acquaintances and continually deliberated about how to respond to crises.” [62] “One participant continued to rely on her mother because her instructions were clear and specific.” [59] |

|

|

“Participants sought informational support about asthma from health professionals, ʻohana, internet, Child Family Services, Kaiser Permanente asthma classes for parents and children, and the American Lung Association.” [60] | |

|

“Parents had several recommendations for asthma education strategies and methods: (1) televised public service announcements, (2) faith-based community outreach and asthma education sessions, (3) a “one-stop shop” for reliable and up-to-date asthma information (available via phone and Internet), (4) education-based support groups for parents and children, and (5) school-based asthma education programs for school personnel and families.” [94] | |

|

|

“It is hard for Indian people to ask for the services they need, because it is our way that you should have your family members there to help you. If we don’t ask a question, it’s not that we know it all, but it’s just that we might be afraid to ask the question because of feeling inferior.” [85] |

|

“If there's something going on, I want to know my own stuff. You know, I want to know what the doctors are talking about, side effects, long term and short term. So I went and got my own books and read.” [50] “No other mothers had accessed further information for reasons such as being ‘too busy,’ not having access to the Internet, not knowing where to look, or simply not feeling the need for further information.” [98] |

|

|

“Yes, it works, and I try to always have it somewhere visible in case I’m not at home and someone else is taking care of my son. That person can look at the plan if he or she does not understand what’s happening with my son at any moment.” (Givens 2010) “The asthma action plan was either not used, not understood, or was thought to be too generic.” [29] “Don’t think of action plans when one occurs if happening.” [53] “[C]aregivers expressly stated that simple words and short phrases were needed to supplement what some of the pictures were conveying.” [45] |

|

Abbreviations: CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; ED = emergency department; HCP = health care provider; PCP = primary care provider; WAAP = written asthma action plan.

3.4.1. Parent experiences

Parent experiences from 78 studies (23 quantitative, 52 qualitative and 3 mixed methods) were organized into five categories: 1) ability to recognize asthma exacerbation symptoms, 2) managing exacerbations at home, 3) seeking health care and interactions with healthcare providers (HCPs), 4) access and barriers to urgent health care, and 5) psychosocial impact on parents.

3.4.1.1. Parents' ability to recognize symptoms of an exacerbation

3.4.1.1.1. Confidence in recognizing an exacerbation

Parents reported differing levels of confidence or self-efficacy in recognizing their child's exacerbation symptoms. Eleven studies (1 quantitative and 10 qualitative) reported that parents were confident in knowing when their child was having an exacerbation and needed his/her medication [26,35,36,50,52,59,63,64,88,96,104]. Many parents acknowledged that their ability to recognize exacerbation symptoms improved with lived experience [26,28,36,41,50,59,62,63,88]. Conversely, six qualitative studies reported that parents felt confused, uncertain or fearful about their ability to recognize exacerbation symptoms or distinguish mild respiratory symptoms (e.g. cough, cold) from a true asthma exacerbation [32,41,59,64,72,98]. In particular, recognizing exacerbations in young children was worrisome for parents because young children were unable to voice their discomfort or symptoms [41,50,59]. Parents reported that exacerbation recognition became easier as children aged and were more reliable in reporting problems [101].

3.4.1.1.2. Unpredictability of an exacerbation

Another common concern in the qualitative studies related to parents' report of symptoms occurring unpredictably or suddenly. Parents were surprised [41,62,63], confused [60,87], scared [28,36,85,87] or frustrated [28] by the quick onset of symptoms. In some cases, this enforced a state of preparedness [28] or hypervigilance [32,50].

3.4.1.2. Parents' experiences managing an exacerbation at home

Forty-eight studies (7 quantitative, 39 qualitative and 2 mixed methods) reported on parents' management of exacerbations at home. Studies included information about parents' confidence in managing their child's exacerbations, as well as the use of different management options (e.g. prescription medications, complementary and alternative medicines (CAM), calming measures).

3.4.1.2.1. Confidence in managing exacerbation symptoms

Parents in 19 studies (3 quantitative, 1 mixed methods and 15 qualitative) rated their self-efficacy in managing their child's exacerbation as either moderate or high [43,53,84,104] or reported feeling comfortable, equipped or confident in their ability to treat their child [26,32,35,41,50,52,59,[62], [63], [64],88,96,98,99,101]. Ten studies reported that parents felt their confidence managing an exacerbation improved with lived experience or after learning more about asthma (e.g. once the child was diagnosed) [26,35,41,50,59,62,63,88,96,98]. However,lack of confidence, uncertainty, self-doubt, and hesitancy to act was reported by parents in nine qualitative studies [26,29,41,49,64,76,84,94,96]. Additionally, in one study, three mothers reported that their confidence in managing their child's exacerbations eroded with the repeated need for professional care, “leaving them feeling helplessly dependent on hospital providers and procedures”. [64].

3.4.1.2.2. Use of different treatment regimens at home

Parents reported their experience with treating their child with prescription medication, complementary and alternative home remedies, and the use of calming measures.

Twenty-three studies reported prescription medications being a common choice of treatment among parents [29,30,33,35,41,49,50,56,57,59,60,64,75,76,78,82,87,88,96,97,99,102,105]. However, parents in over half the studies reported several concerns about quick-relief prescription medications such as adverse side effects [28,30,32,41,49,59,60,75,96,98], administering medication [70,75,98,101] and doubting the effectiveness of the medication [52,84,98].

Several complementary and alternative medicines (CAM), home remedies and religious practices were also strategies parents used to help manage their child's exacerbations. These strategies ranged from prayer [24,27,59,60] and cultural/traditional healing practices [55,59,60,76,82,97], ingestion of natural foods [24,27,49,55,59,60,75,78], Vicks vaporub [24,59,60,76,82,99], herbal rubs and massage [24,27,55,59,60,76], breathing in steam or vapours [27,60,76,82,99], offering the child a drink [49,59,60,76,78], cold and over-the-counter medications [27,66,82], breathing and stretching techniques [27,55,76,78], to playing at the beach in the salty ocean water [60,76].

Notably, a strategy used by some parents was no treatment, or a “wait and see” approach [27,49,66] Additionally, calming or comfort measures such as calming and reassuring the child [40,57,65,70,72,76,81,88,96,100,101], encouraging deep or slow breathing[41,55,59,60,70,81,99], and stopping activities and encouraging the child to rest and relax [40,41,57,59,60,70,99] were reported as exacerbation management strategies.

3.4.1.3. Parents' experiences seeking health care and interactions with HCPs

Forty-six (6 quantitative, 37 qualitative and 3 mixed methods) studies reported on parents' experiences when seeking health care for their child's asthma exacerbations.

3.4.1.3.1. Point of care decisions for seeking help

The most common source of medical care that parents sought during their child's exacerbation was a primary care physician (PCP) [24,41,44,48,50,59,63,64,66,76,78,100,101]. The ED was also mentioned frequently [36,37,40,54,59,[62], [63], [64],76,78,87,99]. Outpatient or walk-in clinics [36,[62], [63], [64]], and an asthma specialist [50] were less commonly used.

3.4.1.3.2. Decision to attend the ED

In 36 studies, parents reported their reasons for taking their child to the ED. The most common reasons included: the treatment(s) at home was/were unsuccessful [28,31,33,38,40,41,52,54,59,63,64,74,76,78,85,88,95,97], the child had severe (e.g. chest retractions, difficulty breathing) or progressive symptoms [36,38,40,50,54,63,64,73,82,85,87,88,101], the child was brought to the ED during every asthma attack or the parent's asthma management style was “crisis oriented” [26,29,36,38,40,54,63,83,84,96,99,101], and the PCP was unavailable or it was impractical to attend primary care [40,44,56,63,74,87,101]. Other reported reasons included: the child requested medical attention [32,88], the parents trusted the care provided at the ED [74] and the PCP recommended the child attend the ED [54].

3.4.1.3.3. Experiences and interactions with HCPs

Twenty-four qualitative studies addressed parents' experiences in the ED, inpatient hospital wards, clinic or intensive care unit when their child had an asthma exacerbation.

Positive Experiences: Five studies [40,59,77,96,101] reported parents felt they received good care for their child during an exacerbation. When the treatments received in the ED or hospital were successful, a few parents reflected on their relief and gratitude for the care received [40,101]. Four studies noted parents appreciated when HCPs listened to their concerns and collaborated with them when making decisions during a child's exacerbation [41,50,64,99]. The desire for family-centred care and shared decision-making was evident in eight studies [33,41,50,63,64,83,99,100].

Negative Experiences: Ten studies reported on parents' feelings of frustration, fear and worry related to the long waits before the child received treatment in the ED [33,40,59,[63], [64], [65],83,87,88]. Studies reported that parents perceived the HCP to be unfamiliar with asthma exacerbation assessments and treatments [31,50,54,64], observed a lack of standardized treatment protocols [48,101], and thought that their child was sent home without being properly assessed or treated [31,50,64,101]. Seven studies reported parents felt they were being treated rudely, with condescension or were blamed by staff [32,33,50,62,85,96,105] and one study reported that ethnic minority parents perceived the disrespect or mistreatment they received to stem from racism [85]. Five studies also found that non-English speaking parents experienced the language barrier as an added stressor during their child's visit to the ED or hospital [33,40,83,87,102], noting that parents felt anxious, frustrated, embarrassed or powerless when they were unsuccessful in communicating their child's needs or receiving important information from HCPs [33,83].

3.4.1.4. Access and barriers to equipment and health care

Five quantitative studies reported that the majority of parents (706/967, 73%) had adequate access to health care when their child was experiencing an exacerbation [39,47,54,66,68]. They were able to make unscheduled appointments or call their PCP when needed [66,68], had access to evening or weekend advice [39], and perceived access to care as “easy” [47] or “not too difficult” [54]. However, four quantitative [47,67,69,90], 1 mixed methods [53] and 10 qualitative [31,48,50,56,60,64,73,85,96,99] studies identified parent-reported barriers regarding access to urgent asthma care. The most common barrier related to cost (poverty) or insurance issues [31,47,48,64,67,69,73,85,96,99]. Other health care barriers included: transportation issues [50,56,59,73,85,90], difficulties contacting the PCP after hours or obtaining an urgent appointment [48,96], the primary care office was not open [90], the family did not have a PCP [56], or parents perceived a lack of health care supplies at the primary care clinic to adequately treat their child's exacerbation [69].

In addition to accessing health services, parents indicated that access to quick-relief asthma medications and equipment was limited by: cost, no insurance or insurance limitations on refills or nebulizers [59,75,87,96]; lack of access to a pediatrician to obtain prescriptions [87]; and difficulty in filling prescriptions immediately after a child's visit to the ED or hospital due to a lack of time or transportation issues [87].

3.4.1.5. Emotional and personal impacts on parents

Managing a child's asthma exacerbations had several psychosocial effects on parents including a range of emotional responses, poor sleep, and disrupted lifestyle due to their child's asthma exacerbations.

3.4.1.5.1. Feelings of fear and frustration

Parents' emotional responses to their child's exacerbations ranged from fear (of the child's death) [28,29,31,33,41,44,50,55,59,[62], [63], [64],70,73,[83], [84], [85],93,102], being scared [28,29,32,33,36,40,41,46,50,59,62,63,65,70,83,85,87,88,100,102], anxious [29,33,40,41,87,89,105], concerned [28,40,84], worried [25,31,67,82,87,102] and upset [25,59,67] to feeling helpless [25,28,29,40,41,46,50,59,[62], [63], [64], [65],73,83,84,88,93], distressed [59,62,87,96], and frustrated [28,29,33,50,56,59,65,93]. Other emotions experienced by parents reported in the qualitative studies included denial [59], doubt [41,96], feeling lost [29,56,62], panicked [26,29,41,62,63,92,102,105], empathy toward their child's circumstances [29,59,64,65,83,103], loneliness or isolation [29,50], sense of responsibility for their child's wellbeing [31,41,62,64,65,77,80,100], relief after asthma diagnosis or a successful treatment [41,63,105], guilt or feeling criticized for not acting sooner [62,92] or feeling stressed from the lack of sleep [85,92].

3.4.1.5.2. Poor sleep and stress at night

Fourteen (6 quantitative and 8 qualitative) studies highlighted the impact of a child's exacerbations on parents' sleep. Because of actively managing their child's exacerbations during the night [50,59,82,98,100], parents reported being woken up regularly [67,91,93], having sleepless nights [25,68], and experiencing significant sleep disruption as measured by the Modified Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, compared to healthy controls [71]. Additionally, parents felt the management of exacerbations during the night was complicated by additional challenges of finding child care for other children or bringing the entire family to the ED [63,85] and struggling to administer medications “when the child and parent are tired and grumpy” [98].

3.4.1.5.3. Changes in plans or disrupted lifestyle

One quantitative [67] and two qualitative [41,52] studies agreed that their child's asthma exacerbations caused the family to change plans, miss events or leave functions early. Additionally, parents in five quantitative [42,54,68,84,93] and 15 qualitative [31,32,36,41,50,52,56,59,63,75,85,96,98,100,102] studies reported missed work or school days in order to deal with their child's exacerbations.

3.4.2. Parent information needs

Forty-five studies (9 quantitative, 33 qualitative and 3 mixed methods) examined parents' information needs around asthma exacerbations. The findings were categorized into four key areas: 1) knowledge gaps, 2) type of information wanted, 3) sources of information and preferences for the mode of information delivery, 4) information seeking behaviours and decision-making preferences.

3.4.2.1. Lack of information and knowledge gaps

Parent reports of receiving and understanding asthma education about the management of an asthma exacerbation were variable across 27 (3 quantitative, 22 qualitative and 2 mixed methods) studies. While parents in six studies reported receiving adequate information [26,28,34,59,60,64], 24 studies reported that parents did not receive comprehensive information or that there were gaps in their knowledge [26,27,29,33,48,50,54,57,59,60,64,72,73,75,[83], [84], [85], [86], [87],94,96,98,103,107]. Some parents reported difficulty in identifying their knowledge gaps or articulating their information needs [26,88]. Parents in two qualitative studies agreed that the ability to recognize their information needs increased with experience [26,56].

3.4.2.2. Type of information wanted

The type of information parents wanted or the specific topics they felt they lacked education were reported by 20 studies (5 quantitative, 14 qualitative and 1 mixed methods). Parents wanted more information or education on: how to recognize exacerbation symptoms and severity [26,48,57,66,83,88,98]; how to treat an exacerbation [33,57,59,64,73,83,96,107]; the function of medications [26,54,59,64], difference between quick-relief and controller medications [43,51], medication dosing [96], side effects and possible interactions of quick-relief medications [50,96]; advice on CAM or information about traditional healing practices [27,59]; and when to seek medical attention [98].

3.4.2.3. Sources of information

Parents obtained information from one or more sources, including their HCP, the internet, videos, asthma classes, family members, other parents, coworkers, community agencies, news articles, printed materials and their personal experiences [24,28,29,33,41,49,50,52,57,59,60,62,66,72,75,78,79,88,92,[96], [97], [98],101,103,105].

Parents who sought advice from family members or lay sources, rather than HCPs, did so because of their desire to discuss unconventional treatments [49], an asthma diagnosis or information was not provided by a health professional [28,62,75], or the parent was comfortable with a family member's instructions because it was clear and specific [59].

3.4.2.4. Preferences for mode of information delivery

Parents reported several preferred modes of receiving information. The most common was asthma education sessions [50,60,83,94,101,103]. Other preferred modes of delivery included printed materials (e.g. pamphlet, book, written instructions) [50,59,83,86], websites or an up-to-date central repository [59,88,94], community outreach initiatives (e.g. televised public service announcements, faith-based community outreach, health fairs, school-based programs) [50,83,94], designated telephone lines [94,101], peer or support groups [59,94] and one-on-one in-person education [86,87].

3.4.2.5. Information seeking behaviours and decision-making preferences

Parents differed in their preferences for or comfort level with seeking information. A few parents in one study were afraid to ask HCPs questions because the parents felt inadequate or inferior [85]. Parents in two studies preferred self-directed information seeking [26,50]; however, another study found that self-directed information seeking may not be initiated “for reasons such as being ‘too busy,’ not having access to the Internet, not knowing where to look, or simply not feeling the need for further information” [98]. One study evaluated parental information-seeking and decision-making preferences [58]. The author concluded that (i) parents generally preferred lower autonomy regarding decision-making “compared to a desire for information,” but there was high variability in decision-making preference scores, and (ii) parents wanted as much information as possible and likely would have been interested in an asthma education intervention.

Two mixed methods [53,54] and three qualitative studies [83,88,99] found that the majority of parents thought a Written Asthma Action Plan (WAAP) was useful to manage their child's exacerbations before seeking medical care. On the other hand, some parents reported not using a WAAP because they did not think of it when an exacerbation was occurring or they did not believe it was a useful tool [29,53,88,99].

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

In this comprehensive mixed studies systematic review, we identified 84 studies (since 2002) that addressed parents' experiences and information needs regarding their child's acute asthma exacerbations. This clearly represents an important parent concern for a prevalent condition, in which nuances such as severity of illness, day to day management, healthcare system and support available, greatly impact parent experiences. Our findings revealed that many parents feel a sense of uncertainty and worry when dealing with their child's acute asthma exacerbations, in large part due to a lack of information.

4.1.1. Experiences

A common finding was that some parents were not confident in their ability to recognize their child's exacerbation, and a number of parents were uncertain about when to seek medical attention. The uncertainty and lack of confidence in recognizing the onset of a child's exacerbation was particularly apparent with parents of young children (who cannot voice concerns to their parents) [41,50,59]. Some parents indicated that their confidence increased over time with lived experience; however, in a few cases, parents' confidence regressed due to frequent crises requiring professional care, leaving the parent to feel helpless and dependent on hospital providers and procedures [64].

Many parents felt comfortable managing an exacerbation with prescription medications, though some parents chose to use home remedies or traditional practices instead of or in addition to prescription medications. Unfortunately, there are risks associated with using alternative treatments for asthma exacerbations, such as adverse interactions or side effects, delays in seeking medical intervention and worsening asthma symptoms [108]. Thus, education and resources providing information on the identification and home treatment of exacerbations, as well as when to seek medical care would be beneficial to parents.

Preferences for seeking medical care may have been influenced in part by the negative experiences parents had with certain health centers or providers, as reported by a large majority of parents. The prevalent negative experiences in these North American studies were in contrast to an Australian study of a general pediatric population in which parents appreciated the timely and collaborative care that their child received at a pediatric ED [109]. Peeler et al. (2019) described how parents' stress and concerns were alleviated by a prompt assessment of the child, continual communication and updates, competent care and consultation with parents about treatment decisions [109]. Incorporating these factors into the care provided to children suffering from an asthma exacerbation may help improve the quality of care received and lessen parents' distress, frustration and anxiety (e.g. perhaps KT resources directed at HCP are needed at non pediatric ED settings to manage pediatric cases?).

The main barrier to accessing quick-relief asthma medications and immediate health care in the included studies was cost or insurance issues. The studies citing cost as a constraint were all conducted in the USA where health insurance may be difficult to obtain for low-income and immigrant families [110], which are subpopulations typically at higher risk for asthma [1,2]. Parent suggestions to improve health care access were scarce in this body of evidence; however, a solution that parents in one qualitative study proposed to improve access to after-hours asthma care prior to visiting an ED was a 24-h phone line [96]. While system-level changes are needed to address the longstanding issues of health insurance coverage and wait times, solutions that HCPs and parents could work toward may include effective communication and education to ensure that parents are aware of the options available to manage their child's exacerbations at home.

We found managing a child's asthma exacerbations had several personal effects on parents (e.g. less sleep, poor quality of sleep, feelings of distress and worry, disrupted lifestyles). These findings are supported by a related study [111] that found there were four key factors that loaded onto parents' distress about their child's asthma: sleepless nights, being awakened, feeling upset and feeling helpless. Poor sleep, in particular, can have detrimental physical and emotional effects on parents, including fatigue and poor daytime functioning, reduced capacity to cope with the child's care needs, and increased crying and irritability [112]. This emphasizes the stressors parents experience in managing their child's exacerbations and not getting enough quality sleep.

4.1.2. Information needs

In general, parents wanted more information to better recognize and manage their child's asthma exacerbations. Based on parent-reported feelings of uncertainty about when to seek medical care [63,88,94,106] and what to expect when the child is treated at a health center [33,59,62,83,87], educational resources could be developed to alleviate parents' worries regarding recognition and treatment within the home and health care setting.

Comprehension of medical advice played an important role in parents' ability to manage an exacerbation and follow treatment guidelines. Unfamiliarity with the medical terminology used or low health literacy can lead to parents' confusion and misinterpretation of the information provided [113,114]. Additionally, parents may need something that is very clear and straightforward when tired or stressed, as their capacity for absorbing or implementing information may be reduced.

Parents usually sought information from multiple sources, including HCPs and lay sources. To ensure that parents receive credible and consistent information, it is important that information and education for parents is readily available in emergency and primary care settings. However, there are numerous challenges in providing comprehensive information in a health setting (e.g. lack of time, ability to retain information during a stressful event, distractions) [86]. Multipronged approaches to disseminating evidence-based recommendations, such as supplemental online videos or group classes, may be useful to enhance parents' knowledge and meet their information needs. With this in mind, it is important to consider parents' preferences for how they would like to receive information.

Parents wanted comprehensive education on recognizing symptoms [48,66] and treatment steps [43,50,96] and when to seek medical attention [98] in the form of education sessions, written materials or online resources [50,59,83,86,88,94]. The quantity of information needed was less clear, but some studies noted that parents wanted as much information as possible [33,58].

Interestingly, a few parents acknowledged that the ability to recognize their information needs increased with experience [26,56]. Therefore, recognizing the type of information that parents were lacking may be more of a barrier for parents of newly diagnosed children. Early education and accessible KT tools could help to fill this knowledge gap and prompt parents to think about questions to raise with the child's primary asthma provider.

4.1.3. Limitations

A possible limitation of this review was the difficulty in distinguishing data regarding ongoing and acute asthma exacerbation management, which are often interrelated concepts. Study participants or authors of the included studies did not consistently distinguish between the two types of management. This was especially challenging for information needs where knowledge about the disease etiology, triggers, different medications and management strategies may help inform parents' identification and treatment of exacerbations. We limited data collection on parent experiences to exacerbations by assessing potentially relevant data in the context of the individual study. Data that were ambiguous or primarily related to ongoing management or disease prevention were not extracted. We were more inclusive of data relevant to information needs because it was particularly difficult to disentangle parents' information needs regarding ongoing and acute management.

Eight included studies (9.5%) were rated as low quality (MMAT score < 60%) because of methodological flaws or inadequate reporting. We acknowledge that bias may have been introduced in these records; however, they presented relevant parent-reported experiences and information needs and contributed to the richness of our findings. It is also worth noting that studies with overall high-quality ratings may have: (i) scored poorly in one or two MMAT domains and may not have been devoid of bias [115], (ii) reported minimal findings, or (iii) poorly interpreted the data, leading to incomplete insights into the researched topic [116]. Hence, we included all studies that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria regardless of quality to provide a comprehensive overview of the available literature addressing our outcomes of interest and explore new insights.

4.2. Innovation

This review identified an abundance of data on parents' experiences and information needs regarding their child's asthma exacerbations. To our knowledge, the evidence on this subject has not yet been synthesized and the drivers of parents' disease management decisions, especially decisions that deviate from clinical guidelines, have not been well understood.

The volume and heterogeneous nature of the literature indicates that there are many factors impacting parents' management of their child's asthma exacerbations (e.g., severity of illness, preferences for treatment, health care systems and supports). A common narrative from this review was that parents lacked information, which impacted their emotional responses to their child's asthma exacerbations (e.g. feelings of fear or helplessness) and care decisions. Given the many factors affecting parents' access to and comprehension of information on asthma exacerbations, tailored interventions and KT strategies must be developed with input from the target audience in order to meet parents' information needs. When possible, customizable features of clinical resources (e.g. personalized action plans) and shared decision-making may facilitate parents' acceptance and understanding of professional recommendations, and support parents' decisions regarding their child's asthma management.

We combined the findings of this review with parent interviews to create an innovative KT video for parents. The video provides evidence-based information to help families understand common symptoms of asthma, how to manage symptoms at home and when to seek emergency care. The video is freely available at http://www.echokt.ca/asthma/.

4.3. Conclusion

To optimize the care of pediatric patients experiencing an asthma exacerbation, it is important to understand parents' experiences and information needs with respect to their child's condition. Through this mixed studies systematic review, we found that parents felt they carried considerable responsibility in managing their child's exacerbations. Parents were stressed when they could not recognize or were not confident in treating exacerbation symptoms at home. This aligned with their information needs preferences focusing on how to recognize and treat exacerbations at home and when to seek medical attention.

Adequately addressing parents' information needs depends on characteristics of the population (e.g. health literacy, non-English speaking) and preferences for mode of information delivery. Therefore, parent engagement and targeted KT strategies (e.g. offering parents more than one format), are recommended when developing and/or distributing resources to ensure that the format and content meets parents' needs, ultimately leading to improved outcomes for children with asthma.

Data availability

The data associated with this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

PROSPERO registration #: CRD42019145746

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Foundation grant awarded to Drs. Hartling and Scott. Dr. Hartling is a Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis and Translation and a Distinguished Researcher, Stollery Science Lab. Dr. Scott is a Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation in Children's Health and a Distinguished Researcher, Stollery Science Lab.

We would also like to thank the Research Assistants, Article Retrieval Personnel and Librarian who supported this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2021.100006.

Appendix 1. Protocol deviations - data synthesis

Initially we proposed to conduct a sequential explanatory approach and synthesize quantitative outcome data in first phase followed by qualitative outcome data in second phase (details of the method are available in the protocol). Later in the review process, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) published new methodological guidance for the conduct of the mixed studies systematic reviews [22]. Due to the greater volume and content of qualitative outcome data reported across the included studies, we decided to follow the JBI's convergent integrated approach and synthesized qualitative and quantitative outcome data in parallel rather than in sequence. We believed this data-based approach was more relevant to address our research question.

Appendix 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection

| Characteristic | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Publication date | January 2002 or later | Prior to January 2002 |

| Language | English and French | Languages other than English and French |

| Study design | Primary studies: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods designs |

|

| Population | Parents or guardians of children (0-18 years) who have experienced acute asthma exacerbations | Animal models |

| Outcome | Self-reported parent experiences or information needs related to their child's acute asthma exacerbations (either immediately before, during or after and exacerbation). |

|

| Country | Canada, United States | Countries other than Canada and the United States |

Intervention studies (e.g. education programs) that influence or change parents' experiences or information needs regarding their child's acute asthma exacerbations were excluded.

Appendix 3. Supplementary data

PRISMA Checklist

Systematic Review Search Strategies

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

Detailed Table of Characteristics of Included Studies

References

- 1.Akinbami L., et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001-2010. NCHS. Data Brief. 2012;(94):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus P., Wise S. Epidemiology of asthma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;24(3):245–249. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Chronic respiratory diseases: asthma. 2021. https://www.who.int/respiratory/asthma/en/ [cited 2019 November 7]; Available from:

- 4.Weiss A., et al. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [Internet]; 2011. Overview of Emergency Department Visits in the United States; p. 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garner R., Kohen D. Changes in the prevalence of asthma among Canadian children. Health Rep. 2008;19(2):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett S., Nurmagambetov T. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002-2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanova J., et al. Effect of asthma exacerbations on health care costs among asthmatic patients with moderate and severe persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(5):1229–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougherty R., Fahy J. Acute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation-prone phenotype. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(2):193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FitzGeralda J., et al. Recognition and management of severe asthma: a Canadian thoracic society position statement. Canadian J Respirat Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017;1(4):199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Program, N.A.E.A.P . National Institute of health - National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2012. Asthma care quick reference: diagnosing and managing asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosychuk R., Youngson E., Rowe B. Presentations to Alberta emergency departments for asthma: a time series analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(8):942–949. doi: 10.1111/acem.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoos H., et al. The impact of the parental illness representation on disease management in childhood asthma. Nurs Res. 2007;56(3):167–174. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000270023.44618.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Archibald M., Scott S. The information needs of North American parents of children with asthma: a state-of-the-science review of the literature. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(1) doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2012.07.003. 5-13.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartling L., et al. Development and evaluation of a parent advisory group to inform a research program for knowledge translation in child health. Res Involv Engage. 2021;7(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s40900-021-00280-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartling L., et al. Grey literature in systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Silva D. Vol. 50. The Health Foundation; London, UK: 2013. Evidence scan No. 18: Measuring patient experience. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gates A., et al. A systematic review of parents’ experiences and information needs related to their child’s urinary tract infection. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(7):1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gates M., et al. Parent experiences and information needs related to bronchiolitis: a mixed studies systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):864–878. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pace R., et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pluye P., et al. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(4):529–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stern C., et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2108–2118. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams-Labonte S. University of Massachusetts; Boston: 2007. Complementary and alternative medication (cam) use, parental beliefs, and communication about asthma: An urban perspective; p. 1291. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annett R., et al. Using structural equation modeling to understand child and parent perceptions of asthma quality of life. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(8):870–882. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Archibald M., et al. What is left unsaid: an interpretive description of the information needs of parents of children with asthma. Res Nurs Health. 2015;38(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/nur.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arcoleo K. University of Rochester; New York: 2006. Variations in parental illness representations of children with asthma: The impact on the use of complementary and alternative medicine and symptom severity; p. 412. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arcoleo K., et al. Illness representations and cultural practices play a role in patient-centered care in childhood asthma: experiences of Mexican mothers. J Asthma. 2015;52(7):699–706. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.1001905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arroyo J. A needs assessment for the delivery of asthma education to parents of Young children. Respirat Care Educat Annual. 2014;23:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bearison D., Minian N., Granowetter L. Medical management of asthma and folk medicine in a Hispanic community. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(4):385–392. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellin M., et al. Improving Care of Inner-City Children with poorly controlled asthma: what mothers want you to know. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32(4):387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellin M., et al. Caregiver perception of asthma management of children in the context of poverty. J Asthma. 2017;54(2):162–172. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1198375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg J., et al. One gets so afraid: Latino families and asthma management--an exploratory study. J Pediatr Health Care. 2007;21(6):361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohm S. Michigan State University; Ann Arbor: 2003. Children with asthma at a Michigan hospital emergency department: Do their care and management adhere to the NAEPP guidelines for asthma? p. 100. Masters dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bokhour B., et al. Patterns of concordance and non-concordance with clinician recommendations and parents’ explanatory models in children with asthma. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(3):376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyle J., Baker R., Kemp V. School-based asthma: a study in an African American elementary school. J Transcult Nurs. 2004;15(3):195–206. doi: 10.1177/1043659604265112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butterfoss F., Kelly C., Taylor-Fishwick J. Health planning that magnifies the community’s voice: allies against asthma. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(1):113–128. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butz A., et al. Asthma management practices at home in young inner-city children. J Asthma. 2004;41(4):433–444. doi: 10.1081/jas-120033985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Claudio L., Stingone J. Primary household language and asthma care among Latino children. J Health Care Poor & Unders. 2009;20(3):766–779. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coffey J., et al. Puerto Rican families’ experiences of asthma and use of the emergency department for asthma care. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26(5):356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawson C. State University of New York at Albany; Ann Arbor: 2017. The Lived Experience of Caregivers for Children with Asthma; p. 125. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dean B., et al. The impact of uncontrolled asthma on absenteeism and health-related quality of life. J Asthma. 2009;46(9):861–866. doi: 10.3109/02770900903184237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deis J., et al. Parental knowledge and use of preventive asthma care measures in two pediatric emergency departments. J Asthma. 2010;47(5):551–556. doi: 10.3109/02770900903560225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dowell J. Experiences, functioning and needs of low-income African American mothers of children with asthma. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duncan C., et al. Developing pictorial asthma action plans to promote self-management and health in rural youth with asthma: a qualitative study. J Asthma. 2018;55(8):915–923. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1371743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Everhart R., et al. Ethnic differences in caregiver quality of life in pediatric asthma. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(8):599–607. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318264c2b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flores G., et al. Keeping children with asthma out of hospitals: parents’ and physicians’ perspectives on how pediatric asthma hospitalizations can be prevented. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):957–965. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fredrickson D., et al. Understanding frequent emergency room use by Medicaid-insured children with asthma: a combined quantitative and qualitative study. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(2):96–100. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freidin B., Timmermans S. Complementary and alternative medicine for children’s asthma: satisfaction, care provider responsiveness, and networks of care. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(1):43–55. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gehring L. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Ann Arbor: 2002. Focusing on my child: Weaving the web of asthma care; p. 248. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geryk L., et al. Exploring youth and caregiver preferences for asthma education video content. J Asthma. 2016;53(1):101–106. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1057847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibson-Young L., et al. Interviews with caregivers during acute asthma hospitalisations. J Asthma. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1602875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]