Abstract

Objective

This article presents a new conceptual framework “Connection to Health for Smokers” (CTHS), its application to address smoking cessation, and its acceptability in community health centers (CHCs).

Methods

CTHS, an online interactive patient educational tool comprehensively implements the “5 A's” (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange) within the context of patients' social and behavioral health needs. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with five health educators (nurses) who administered CTHS with 62 patients to evaluate the acceptability of the program. Thematic analyses were conducted with interview transcripts.

Results

CHC health educators viewed CTHS has enhanced patient-centered communication, was able to identify patients' needs beyond tobacco use, and individualize action planning to integrate social and behavioral health needs.

Conclusion

CTHS received enthusiasm from CHC health educators as a helpful tool to address tobacco use among their patients. Comprehensive on-site smoking cessation programs at CHCs that provide a structured evidence-based approach informed by an understanding of each patient's coexisting social and behavioral health needs may play an important role in reducing tobacco use disparities in the United States.

Innovation

CTHS offers a new promising framework to comprehensively integrate the 5A's within the context of social and behavioral determinants of health for smoking cessation.

Keywords: Tobacco, Smoking cessation, Primary care, Community health centers, Underserved, Provider-patient communication, 5A's, Patient education, Patient-centered communication

Highlights

-

•

Social and behavioral health challenges may interfere smoking cessation

-

•

CTHS implements “5A's” while addressing coexisting social and behavioral needs

-

•

Integrate patients' needs in tobacco treatment optimizes cessation outcomes

-

•

Nurses viewed addressing complex needs helpful to motivate smokers to quit smoking

-

•

Comprehensive patient-centered approach may reduce tobacco use disparities

1. Introduction

Tobacco use, especially cigarette smoking, is a leading cause of preventable death in the United States [1]. While the prevalence of cigarette smoking in the United States declined from 20.9% in 2005 to 14% in 2019, tobacco use remains high among populations living below the poverty level, those with lower levels of education, and the underinsured [2]. Many of these individuals receive healthcare from community health centers (CHCs). CHCs serve as the primary medical home for 30 million people in more than 14,000 rural, suburban, and urban clinical sites across the United States [3]. Primary care clinicians in CHCs are responsible for counseling patients to quit smoking during office visits, finding time and resources during primary care visits to address smoking effectively in the context of other related health problems can be difficult, while referring patients off-site for these services may not be well-coordinated or accepted by patients [[4], [5], [6]]. A majority of CHCs responding to a national survey acknowledged many barriers for providing smoking cessation services, including lack of comprehensive on-site programs [7]. CHC patients are disproportionately affected by various health-related challenges that may interfere with tobacco cessation such as food insecurity [8], unstable housing [9], social isolation [10], alcohol use or adverse health behaviors [11], and co-occurring behavioral health conditions [12]. These social determinants of health negatively affect health and well-being and will need to be addressed within the context of tobacco cessation [13].

Since 1996, the US Preventive Services Task Force has recommended that clinicians ask adults about tobacco use and provide cessation advice coupled with behavioral interventions and approved pharmacotherapy to tobacco users [14]. These recommendations were reaffirmed in 2020 [15], which correspond to the “5 A's”: 1) ask about tobacco use at every visit; 2) advise all tobacco users to quit; 3) assess readiness to quit; 4) assist those who are ready with a quit plan; and 5) arrange follow-up visits. However, delivering the 5A's to individual patients without an awareness of their social environment (e.g., social support, home environment, food security, or physical safety), lifestyle health behaviors (e.g., dietary choices, physical activity, or stress management), and behavioral health conditions (e.g., depression or co-occurring substance use) may reduce the effectiveness of these efforts [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. We sought to develop a novel program, called Connection to Health for Smokers (CTHS), to comprehensively implement the 5 A's within the context of social environment, health behaviors, and behavioral health for smoking cessation in CHCs, where resources are limited and many of the highest risk individuals with complex needs receive care. In this article, we describe this framework, the program we developed, and evidence of its feasibility in clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. The Connection to Health for Smokers (CTHS) intervention framework

CTHS was adapted from Connection to Health (CTH), an evidence-based program to provide self-management support for individuals with chronic disease through structured and comprehensive patient assessment, collaborative priority setting, detailed action planning, and follow up [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. A comprehensive assessment includes assessing patient's health behaviors (e.g., dietary intake and physical activity), behavioral health conditions (e.g., depression and substance use), and social environments (e.g., social support, home environment). After assessment, patients will be guided by a series of questions to help identify areas of concern that the patient would like to prioritize (priority setting). Action planning builds on patient's priorities by leveraging their existing strengths or resources, and referring patients to the needed support such as referrals to address concurrent behavioral health conditions. Follow-up involves reminders via text and/or telephone calls to follow-up with progress and to revise action plans as needed. An important feature of CTH includes identifying and addressing complex social and behavioral health challenges which may interfere with optimal clinical outcomes. Current approaches for treating tobacco dependence often target tobacco use as a disease condition without tailoring cessation plans with an awareness of these challenges. Tobacco cessation strategies are generally focused at the level of smoking behaviors, for example matching nicotine replacement therapy dosages to the time of the first cigarette and/or the number of cigarettes smoked per day [26]. The CTHS conceptual framework addresses this gap by adding specific attention to each patient's social and behavioral health needs as an essential step in treating tobacco dependence.

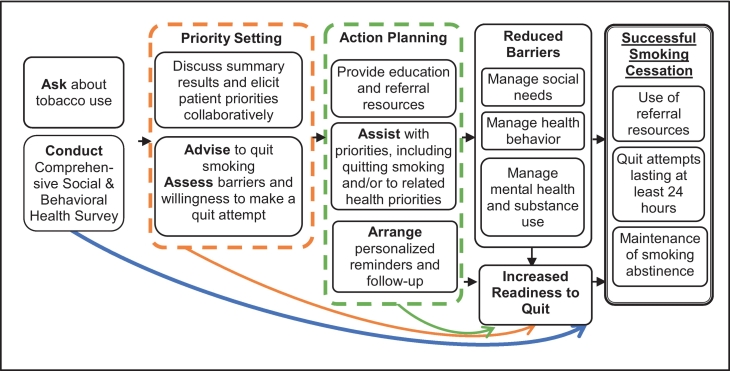

Fig. 1 depicts the CTHS conceptual framework. Expanding from the “5A's,” the framework has three integrated key components: Assessment, Priority Setting and Action Planning. The first component, Assessment involves tobacco screening (Ask) integrated with a comprehensive assessment of an individuals' social environment, health behavior, and behavioral health. During Priority Setting, the health educator reviews the results of the assessment with the patient and elicits the patient's relative interest in tobacco cessation in the context of other social and behavioral needs (Assess). Leveraging this discussion, the health educator advises patient on the long-term importance of quitting smoking. According to patient's readiness and immediate goals (Advise). Action Planning proceeds with the health educator assisting the patient by providing education, generating action plans to address their priorities including quitting smoking or cutting down on smoking in the context of other social and behavioral health needs (Assist) and coordinating follow-ups including referrals (Arrange). If the patient is not ready to quit or cut down on smoking, the health educator will assist and arrange follow up for the patient on another priority which is perceived to be a barrier to smoking cessation.

Fig. 1.

Connection To Health for Smokers (CTHS): Conceptual Framework of a Comprehensive Approach to Address Tobacco-Related Health Disparities in Community Health Centers.

The process of Assessment, Priority Setting and Action Planning may result in increased readiness to quit through specific smoking cessation-related activities (e.g., delaying first cigarette of the day, setting a quit date, arranging a trial of pharmacotherapy, and/or referrals to a quitline). In addition, Action Planning may result in reduced barriers for smoking cessation through managing various social and behavioral health needs (e.g., referrals for housing assistance or a food pantry, increasing physical activity, or treatment of anxiety, depression, or substance use). Recognizing that, for some patients, successful smoking cessation may take several visits to address multiple social and behavioral health issues and increase readiness and ability to quit. CTHS promotes a patient-centered approach to smoking cessation. As endorsed by the National Cancer Institute, social and behavioral contexts should be incorporated into guideline-based clinical care [27]. The following section describes how the CTHS intervention framework can be applied in an online tool.

2.2. Online application of the CTHS intervention framework

2.2.1. Assessment

CTHS starts with an online self-administered Health Survey, available in English/Spanish, that is also available in an audio format for patients with limited reading skills. Assessment items have been used in population-based surveys [28,29] and primary care settings [30,31] with diverse populations. The survey consists of two parts: (1) tobacco use and (2) social and behavioral health needs (social environment, health behaviors, and behavioral health). The tobacco use assessment asks about tobacco use status, types of tobacco used in the past 30 days including e-cigarette use, cigarette smoking history (years smoked regularly); previous quit attempts (24-h quit attempt in the past year); methods used to quit smoking in the last year (cutting down, quitting all at once (“cold turkey”), nicotine medications, other medications, joined a smoking cessation program, or other methods with an option to specify); average number of cigarettes smoked per day, time to first cigarette after waking as indicator of nicotine dependence [32], intention to quit within 30 days and 6 months [33], and confidence to be smoke-free for at least 30 days in 6 months from today (from 0 “not at all” to 10”extremely confident”). The social and behavioral health assessment aims to provide the social and behavioral contexts related to smoking and potential barriers for quitting including: depression symptoms as assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (screened by PHQ2 [34] and if PHQ2 ≥ 3 followed by PHQ-8 [35]); perceived general health (poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent) [36]; at-risk alcohol drinking during the past month (exceeding the drinking levels recommended by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: exceeding 7 [for women] or 14 [for men] drinks in a week and/or exceeding 4 [for women, and for men age 65+] or 5 [for men] drinks in any one occasion depending on sex) [37] and illegal drug use/prescription med for non-medical purposes in last year (yes/no) [31]; general life stress in the last week (yes/no); social isolation (talk to someone you feel close to ≤2 times/week); and current experience of social risks (yes/no) in each of the following areas: food insecurity, housing instability, limited access to healthcare due to transportation or cost, feeling unsafe at home, feeling unsafe in the community, or having utilities disconnected in the last year [38]. Scores above the cutoffs generate a reminder on the summary report (below) to initiate a discussion with patient and could lead to referrals within the CHC and/or in the community to addressing these needs.

2.2.2. Priority setting

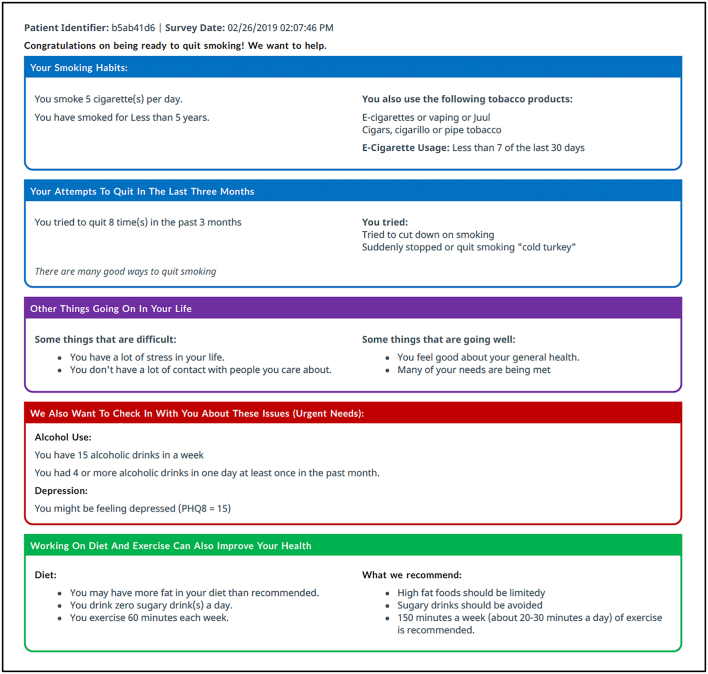

After completion of the Survey, CTHS generates a “Health Summary Report” (Fig. 2). Health educators can use this report to engage patients using a collaborative and patient-centered approach to elicit patient strengths, challenges, and priorities. The report begins by acknowledging the patient's quit intention and is followed by a summary of current tobacco use, including current use of e-cigarettes and a history of prior attempts to quit. Following current clinical guidelines [39], e-cigarette use is addressed similarly to conventional cigarette use with an ultimate goal of abstinence. Specifically, patients were advised that e-cigarette is not an FDA-approved smoking cessation aid [40]. In addition, the report presents important social and behavioral health needs that could be relevant to consider, including patient level strengths and challenges. If the patient reports symptoms of major depression, high-risk alcohol use, or illegal/prescription drug use for non-medical purposes, an “urgent needs” flag alerts the health educator to discuss with the patient on additional specialty referrals as appropriate. The final section draws attention to diet and exercise behaviors that may interact with or inform the tobacco cessation planning process, their corresponding recommended guidelines, and whether patients' current behaviors are meeting the general recommendations. The discussion of the Health Summary Report with the patient allows the health educator to provide patient-centered guidance on tobacco cessation in the context of their health.

Fig. 2.

A Sample of Connect To Health for Smokers (CTHS) Health Summary Report.

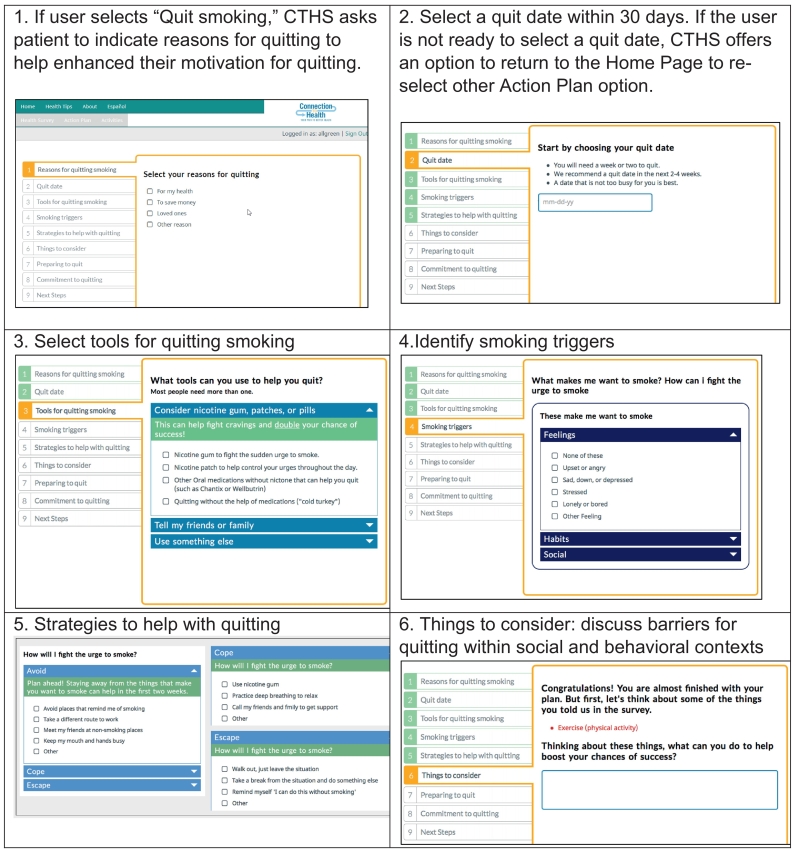

2.2.3. Action planning

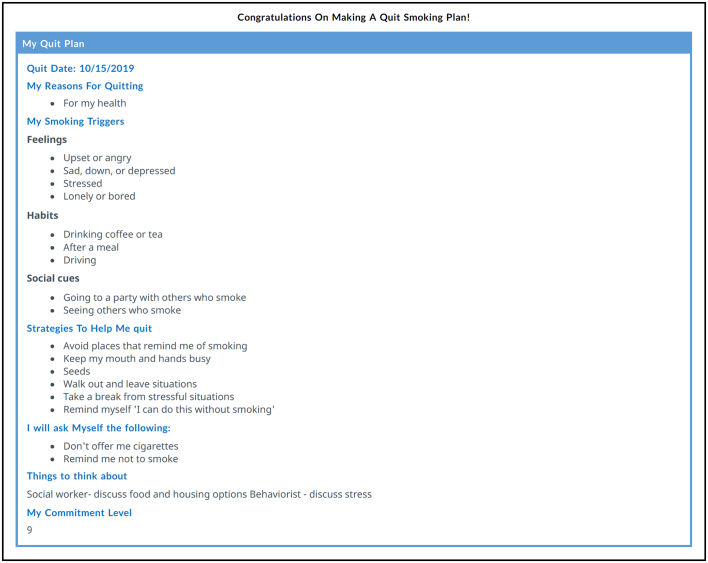

Once patient priorities are discussed and established, the health educator works with individuals using the CTHS Action Planning module. The patient starts by selecting one of 3 Action Plan options: (1) Quit Smoking; (2) Change Smoking Behaviors; or (3) Work on Something Else. Each option leads into a programmed sequence allowing the health educator and patient to collaboratively select detailed, specific, manageable, and realistic steps that the patient feels confident in achieving. Fig. 3 shows sample screenshots of the CTHS Action Planning Online Tool for patients who select “Quit Smoking” as the goal. If the patient selects “Quit Smoking,” but indicates low commitment to their plan and/or inability to select a quit date within the next 30 days, patients are offered an option to change their smoking behaviors instead, for example, by cutting down, delaying the first cigarette, or changing the places where they smoke. CTHS also allows patients who may decide it is not time to change their smoking behaviors given challenges related to housing, finances or other needs. The health educator can engage the patient to address these other needs and revisit smoking behaviors at a future visit. The overall goal of the CTHS tool is to engage the patient in a sustained patient-centered dialogue about their smoking with recognition of the patient's priorities, their needs within social and behavioral contexts, and to provide optimal support in the process, even when they may not be able to quit immediately. After completion, CTHS generates an Action Plan that can be printed for the patient and stored in the electronic health record for future reference (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Connection To Health for Smokers (CTHS) “Quit Smoking” Action Planning: Sample Screenshots.

Fig. 4.

A Sample of Connection To Health for Smokers (CTHS) Action Plan.

2.2.4. Follow-up

Lastly, the patient selects a method of follow-up, which can include weekly or daily motivational text messages or email reminders, and in-person follow-up appointments to provide encouragement, assess progress, revise action plans, or receive additional services. Guided by the health educators, patients are asked to generate personally relevant motivation text messages or email reminders. The CTHS online tool also provides health educators with an electronic dashboard for tracking and documentation.

2.3. User experience: feedback from health educators

2.3.1. Setting

We obtained feedback from health educators who used the CTHS program at three county-run CHC sites in the context of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [41]. Prior to the CTHS implementation, health educators in one of the participating sites provided in-person individual counseling sessions using a video and a booklet to assist patients in preparing for a quit attempt. The other two sites did not have a formal smoking cessation program at baseline. A total of seven nurses (2 to 3 from each clinic) who served as health educators at their clinics participated in a 4-h training that introduced the background of the RCT and the CTHS framework in addressing tobacco use. The training included demonstration and role play to practice use of the online CTHS tool. Patients were recruited by referrals from physicians or by telephone outreach conducted by the health educators to patients identified as smokers in a registry generated from the electronic health record. Patients interested in speaking with a health educator about smoking were scheduled for an in-person clinic visit. During this visit, patients randomized to CTHS completed the program (online patient health survey, summary report review, action planning). Follow-up visits took place by telephone or in-person. A total of 62 patients received CTHS.

2.3.2. Health educators

We invited all the health educators to participate in a 30-min interview to discuss their experiences providing smoking cessation counseling using the CTHS program. Of the seven health educators who participated in the training, two declined the interview, including one who did not administer the program and the other used CTHS with only two patients. The five health educators who agreed to participate in the interviews, all used CTHS with at least 5 patients.

2.3.3. Interview procedures

A semi-structured interview guide was used to engage health educators in discussing their experiences in implementing CTHS on these perspectives: ease and difficulty; use of various program components such as the health summary report; new insights or skills gained, if any, from CTHS; and using CTHS with patients who were not ready to quit smoking. The interviews were conducted by video conference or telephone, and lasted 25 to 40 min.

2.3.4. Qualitative data analyses

The interviews were transcribed with removal of identifiers and analyzed using Dedoose (www.dedoose.com). Three researchers (KL, MBP, JYT) independently reviewed the transcripts, with at least two members of the research team coded each transcript. Using an iterative process, emergent themes were identified, classified, and summarized [42]. The procedure was approved by the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

Three major themes centering around the health educators' perspectives on using the CTHS program emerged: 1) enhancing patient-centered communication, 2) identifying patients' needs beyond tobacco use, and 3) individualized action planning to integrate social and behavioral health needs within and beyond tobacco use.

3.1. Theme #1: enhancing patient-centered communication

Health educators appreciated the systematic structure of CTHS and commented that CTHS facilitated patient engagement. Specifically, the Health Survey engaged patients to participate in considering various needs they had. One of the health educators said “… the program is so structured that it just makes it efficient… the program asks the question and it makes them think…”

Similarly, conducting the assessment and reviewing the Health Summary Report with patients enhanced rapport building:

“I would have them fill out their survey and then I would just go over their answers with them …Then, you know, I would know the answers … So I did use that before going through the action plan, getting to know them, kind of [getting them to] open up a little about themselves… ”.

Several health educators described the Health Summary Report as an efficient tool to understand and communicate about each patient's needs holistically:

“Oh, I love the health summary report because it's a good educational tool… you discuss information regarding their smoking and their health status, and of course their lifestyle, … it could make them decide what goals [they] want to add or change in the future … it's also an effective tool for communication.”

In the process of enhancing communications with patients using CTHS, health educators also felt CTHS benefited them by feeling more engaged and competent in supporting patients with smoking cessation. One of the health educators shared:

“I do like it because it kind of gives you options [referred to the suggested options for coping or quitting methods offered by the CTHS tool as shown in Fig. 3], and so, you know, I think just the knowledge of and seeing what the options are, it helps me become more engaged…”.

Another commented,

“I didn't really know what I didn't know. So as I was going through the program, I got a lot of experience with each patient and just kind of talking with them and using the program.”

3.2. Theme #2: Identifying patients' social and behavioral health needs

The health educators described CTHS as an efficient way to learn about the lived experiences of their patients: “It helped with being time efficient and the health survey was a great way to identify other needs, and it was another tool to help patients...”

Specifically, health educators viewed that the process of identifying patients' needs was helpful in motivating patients “… the questions made the patients think more of why they wanted to quit...” and in setting a mindset or doing the needed preparation for quitting smoking:

“…I feel like knowing their history, such as depression and everything and them getting help with their mental health, it really helps with their mindset of quitting.”

“… if there were any issues with income, with being able to buy food or anything like that, it at least made us aware of what type of situation they're in, especially if they have other things that seem like they would need to get in order before they can really focus on smoking cessation.”

3.3. Theme #3: Individualized action planning integrating patients' needs within and beyond tobacco use

All the health educators found CTHS's capability to tailor action planning for their patients helpful. Specifically, tailoring by integrating patients' social and behavioral health needs in the tobacco treatment plan and by providing various treatment options to meeting patients' needs regarding their tobacco use were important for the patient population they served.

All of the health educators noted that CTHS assists in addressing smoking cessation in the context of social and behavioral needs commonly experienced by the patient populations served by CHCs:

“…we work with the homeless population… the basic needs of housing and food, ... they feel like they could take on other challenges.”

“…if they don't have food, then I'll print out the food bank information for them, [refer them to] social workers… it is useful to know about the patient, not just the smoking aspect but everything.”

“…we talk about a patient going through depression, needing help with food, and housing… it was good sending a message to the behaviorist and giving them the number for the food bank, …guiding them on what we can do to help them not only with the smoking cessation.“.

One health educator, however, pointed out that assessing the social and behavioral health needs during a smoking cessation visit might be redundant for those whose needs may have already been identified and addressed by other health providers in the clinic. Nonetheless, health educators overall did not feel burdened to address those needs while working with their patients on smoking because they routinely make such referrals and the process fit well with their standard workflow.

An important element of CTHS, from the health educators' perspective, is the capacity to offer the option of cutting back on smoking for those not ready to quit:

“…it was helpful because there was an option to cut back and they [the patients] were excited to do that…”.

“I like it because it gives options... So if they just want to cut down their habits, ‘cause not every patient wants to completely quit smoking… That's what we don't have in our program.”

Furthermore, the program empowered patients to see options of actions that they could take:

“…it helps the patients …like self-realization, like what they can do. So it's like it kind of gives them ideas from the options that they give.”

3.4. Limitations

One limitation of the qualitative evaluation methodology used was that the evaluation was based on semi-structured interviews with only five health educators who were all CHC nurses, which was unlikely to be sufficient to reach saturation [43]. Additional themes might have been missed because of the small sample size. Nonetheless, the interview sample included all five nurses who had used the program with at least five patients. Usability and user experience testing of digital health products generally finds a sample size of four to eight participants per user group as acceptable to uncover problems in using the program [44,45]. These health educators had administered the program with 60 of the 62 CHC smoking patient participants across three CHC clinics, and each health educator administered CTHS to at least five patients, which we considered sufficient to provide them with a range of experiences. Another limitation is that the findings may only be limited to nursing staff who serve in the health educator's role but not be generalizable to other types of health providers in CHCs who may take on the health educator role. However, our interviewees had various levels of clinical experience working with patients on tobacco cessation, and their reflections come from a variety of perspectives that may be useful for further development of the CTHS program.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Systematic reviews on perspectives from both patients and primary care physicians [6,46], and clinical expert opinions [47] have recommended approaches beyond brief advice, but they should also be collaborative and respectful of each patient's readiness and individual circumstances related to quitting smoking. The preliminary usability findings from five CHC health educators (nurses) who used the CTHS online tool with 60 CHC patients in offering smoking cessation assistance have provided initial support for its applicability in enhancing communications, identifying patients' social and behavioral needs, and individualized action planning to integrate these needs within and beyond the context of tobacco use. CTHS provides a useful framework to thoroughly address tobacco use in patients with complex needs.

4.2. Innovation

This paper describes a new CTHS conceptual framework and program, and its first implementation in three CHC clinic sites serving patients with complex concurrent physical and behavioral health issues and social needs. Conventional tobacco cessation programs generally focus on patients' smoking behaviors whereas CTHS provides a framework to integrate individuals' social and behavioral health needs using the 5A's in the treatment of tobacco dependence. Findings demonstrate support for a proof of concept applying the novel CTHS framework in CHCs that serve patients who are disproportionately affected by challenges that may interfere with tobacco cessation. CTHS offers a comprehensive patient-centered and collaborative approach to address tobacco use among patients in CHCs where resources are limited, and many individuals served have complex needs.

4.3. Conclusion

Addressing tobacco use should be an integrated part of routine healthcare in primary care, oncology and other settings, supported by health teams and digital technologies when appropriate [6,47,48]. CTHS offers a promising framework to comprehensively integrate the 5A's within the context of social and behavioral determinants of health for smoking cessation. Comprehensive on-site smoking cessation programs for community health centers may play an important role in reducing tobacco use disparities in the US, especially if they incorporate evidence-based approaches to smoking cessation and a more comprehensive understanding of social and behavioral barriers to success.

Funding

This work was supported by the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program [grant number: 27IP-0024]. This project was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR001872. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The researchers acknowledge the leaders and clinical teams at Contra Costa Health Services for their active collaboration in the development, implementation, and evaluation of CTHS. Contra Costa Health Services is a member of the San Francisco Bay Collaborative Research Network, which is supported by UCSF's Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/TOC.pdf Available from.

- 2.Cornelius M.E., Wang T.W., Jamal A., Loretan C.G., Neff L.J. Tobacco product use among adults — United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736–1742. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Association of Community Health Centers America's Health Centers. 2020. nachc.org

- 4.Yarnall K.S., Ostbye T., Krause K.M., Pollak K.I., Gradison M., Michener J.L. Family physicians as team leaders: “time” to share the care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(2):A59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostbye T. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? The Annals Family Med. 2005;3(3):209–214. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manolios E., Sibeoni J., Teixeira M., Révah-Levy A., Verneuil L., Jovic L. When primary care providers and smokers meet: a systematic review and metasynthesis. npj Primary Care Res Med. 2021;31(1) doi: 10.1038/s41533-021-00245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flocke S.A., Vanderpool R., Birkby G., Gullett H., Seaman E.L., Land S., et al. Addressing tobacco cessation at federally qualified health centers: current practices & resources. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(3):1024–1036. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2019.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim-Mozeleski J.E., Pandey R. The intersection of food insecurity and tobacco use: a scoping review. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(1_suppl):38S–124S. doi: 10.1177/1524839919874054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayaraghavan M., Benmarnhia T., Pierce J.P., White M.M., Kempster J., Shi Y., et al. Income disparities in smoking cessation and the diffusion of smoke-free homes among U.S. smokers: Results from two longitudinal surveys. PLoS One. 2018;13(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201467. e0201467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyal S.R., Valente T.W. A systematic review of loneliness and smoking: small effects. Big Implicat Subst Use & Misuse. 2015;50(13):1697–1716. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1027933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook J.W., Fucito L.M., Piasecki T.M., Piper M.E., Schlam T.R., Berg K.M., et al. Relations of alcohol consumption with smoking cessation milestones and tobacco dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(6):1075–1085. doi: 10.1037/a0029931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forman-Hoffman V.L., Hedden S.L., Glasheen C., Davies C., Colpe L.J. The role of mental illness on cigarette dependence and successful quitting in a nationally representative, household-based sample of U.S. adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(7):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. National Cancer Institute . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2017. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities [PDF]https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/m22_complete.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Final Recommendation Statement Tobacco Use Prevention: Counseling, 1996 [Internet] 1996. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-prevention-counseling-1996 updated 1996/01/01. Available from.

- 15.Krist A.H., Davidson K.W., Mangione C.M., Barry M.J., Cabana M., Caughey A.B., et al. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325(3):265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meernik C., Mccullough A., Ranney L., Walsh B., Goldstein A.O. Evaluation of community-based cessation programs: how do smokers with Behavioral health conditions fare? Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(2):158–165. doi: 10.1007/s10597-017-0155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster T., Stead L.F. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3(3):CD001292. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub3. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub3/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen A., Machiorlatti M., Krebs N.M., Muscat J.E. Socioeconomic differences in nicotine exposure and dependence in adult daily smokers. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):375. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6694-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim-Mozeleski J.E., Tsoh J.Y. Food insecurity and psychological distress among former and current smokers with low income. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(2):199–207. doi: 10.1177/0890117118784233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim-Mozeleski J.E., Pandey R., Tsoh J.Y. Psychological distress and cigarette smoking among U.S. households by income: Considering the role of food insecurity. Prev Med Rep. 2019;16:100983. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrett B.E., Martell B.N., Caraballo R.S., King B.A. Socioeconomic differences in cigarette smoking among sociodemographic groups. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16 doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher L., Hessler D., Naranjo D., Polonsky W. AASAP: a program to increase recruitment and retention in clinical trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toobert D.J., Glasgow R.E., Radcliffe J.L. Physiologic and related behavioral outcomes from the Women’s lifestyle heart trial. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02895162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toobert D.J., Glasgow R.E., Nettekoven L.A., Brown J.E. Behavioral and psychosocial effects of intensive lifestyle management for women with coronary heart disease. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow R.E., Toobert D.J., Hampson S.E., Wilson W. Behavioral research on diabetes at the Oregon research institute. Ann Behav Med. 1995;17(1):32–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02888805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation Medications. 2014. In: The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and HealthReports of the Surgeon General. Available from: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/sgr50-chap-14-app14-5.pdf.

- 27.U.S. National Cancer Institute . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2017. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 22. NIH Publication No. 17-CA-8035A [PDF]https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/m22_complete.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): CAI Specifications for Programming (English Version). In: Administration SAaMHS, Rockville, MD2017.

- 29.California Health Interview Survey . UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2019. CHIS 2018 Adult Questionnaire, Version 1.53, September 11, 2019 [PDF]https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Documents/2018%20Questionnaires%20and%20Topics%20List/09-11-19%20Updated/CHIS%202018%20Adult.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulvaney-Day N., Marshall T., Downey Piscopo K., Korsen N., Lynch S., Karnell L.H., et al. Screening for behavioral health conditions in primary care settings: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):335–346. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith P.C., Schmidt S.M., Allensworth-Davies D., Saitz R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(13) doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center Tobacco D, Baker T.B., Piper M.E., DE McCarthy, Bolt D.M., Smith S.S., et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2007;9(Suppl. 4) doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. S555-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiClemente C.C., Prochaska J.O., Fairhurst S.K., Velicer W.F., Rossi J.S. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The patient health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClave A.K., Dube S.R., Strine T.W., Kroenke K., Caraballo R.S., Mokdad A.H. Associations between smoking cessation and anxiety and depression among U.S. adults. Addict Behav. 2009;34(6–7):491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Idler E.L., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Drinking Levels Defined: NIAAA. 2021. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking Available from.

- 38.Gottlieb L.M., Adler N.E., Wing H., Velazquez D., Keeton V., Romero A., et al. Effects of in-person assistance vs personalized written resources about social services on household social risks and child and caregiver health. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2020. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General.https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-full-report.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Food & Drug Administration Fact or Fiction: What to Know About Smoking Cessation and Medications 2019. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fact-or-fiction-what-know-about-smoking-cessation-and-medications updated 03/28/2109. Available from.

- 41.Potter MB, Tsoh JY, Lugtu K, Parra J, Hessler D. Providing smoking Cessation Support in the Context of Other Social and Behavioral Needs: Preliminary Evidence of Feasibility, Acceptability and Efficacy of Two Smoking Cessation Programs in Community Health Centers. [Manuscript Under Review]. 2021.

- 42.Morgan D.L., Nica A. Iterative thematic inquiry: a new method for analyzing qualitative data. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19 160940692095511. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guest G., Namey E., Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Virzi R.A. Refining the test phase of usability evaluation: how many subjects is enough? Hum Fact J Hum Fact Ergon Soc. 1992;34(4):457–468. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis J.R., Sauro J. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics [Internet] 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021. Usability and user experience: design and evaluation. 13 August 2021 [cited 10/1/2021]. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odorico M., Le Goff D., Aerts N., Bastiaens H., Le Reste J.Y. How to support smoking cessation in primary care and the community: a systematic review of interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2019;15:485–502. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S221744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.OCP Van Schayck, Williams S., Barchilon V., Baxter N., Jawad M., Katsaounou P.A., et al. Treating tobacco dependence: guidance for primary care on life-saving interventions. Position statement of the IPCRG. npj Primary Care Res Med. 2017;27(1) doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0039-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Angelo H., Ramsey A.T., Rolland B., Chen L.-S., Bernstein S.L., Fucito L.M., et al. Pragmatic application of the RE-AIM framework to evaluate the implementation of tobacco cessation programs within NCI-designated cancer centers. Front Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]