Highlights

-

•

Rab1a expression is upregulated during PRRSV infection.

-

•

Rab1a promotes PRRSV replication mediated by autophagy.

-

•

Rab1a participates in PRRSV-triggered autophagy by interacting with ULK1.

Keywords: PRRSV, Autophagy, Rab1a, ULK1

Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), an arterivirus from the Nidovirales order, continues to be a threat to the swine industry worldwide causing reproductive failure and respiratory disease in pigs. Previous studies have demonstrated that autophagy plays a positive role in PRRSV replication. However, its mechanism is less clearly understood. Herein, we report first that the protein level of Rab1a, a member of the Ras superfamily of GTPases, is upregulated during PRRSV infection. Subsequently, we demonstrate that Rab1a enhances PRRSV replication through an autophagy pathway as evidenced by knocking down the autophagy-related 7 (ATG7) gene, the key adaptor of autophagy. Importantly, we reveal that Rab1a interacts with ULK1 and promotes ULK1 phosphorylation dependent on its GTP-binding activity. These data indicate that PRRSV utilizes the Rab1a-ULK1 complex to initiate autophagy, which, in turn, benefits viral replication. These findings further highlight the interplay between PRRSV replication and the autophagy pathway, deepening our understanding of PRRSV infection.

1. Introduction

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS), a highly contagious swine disease, has led to tremendous economic losses in the swine industry worldwide by causing acute respiratory distress in piglets and reproductive failure in sows (Neumann et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2007). The etiological agent of this disease, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), is an enveloped, single-positive-stranded RNA virus of the family Arteriviridae (Snijder et al., 2013). Vaccination is currently the major strategy used to control the disease. However, conventional vaccines do not provide satisfied prevention owing to the rapid evolution and variation of PRRSV (Li et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2015). Thus, it is necessary to develop other strategies to control the prevalence of this disease, which requires a better understanding of the mechanism underlying PRRSV replication.

Autophagy (macroautophagy) is a highly conserved cellular process involved in delivering cytosolic components to the lysosome for degradation, thereby playing an important role in maintaining cellular homeostasis (Majeed et al., 2022). The process is divided into four steps, (i) translocation and initiation, (ii) elongation and cargo recruitment, (iii) completion, and (iv) lysosome fusion and degradation (Rubinsztein et al., 2015). The initiation of autophagy is controlled by the ULK1 autophagy initiation complex, which is comprised of Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1), FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa (FIP200), autophagy-related 13 (ATG13), and ATG101 (Ganley et al., 2009; Hara et al., 2008; Hosokawa et al., 2009b; Mercer et al., 2009). Crucially, the initiation of autophagy requires the phosphorylation of ULK1, which enhances its kinase activity (Kim et al., 2011). In turn, ULK1 phosphorylates FIP200 and ATG13 to activate the complex, which then translocates to the phagophore to initiate autophagosome formation (Karanasios et al., 2013).

Rab GTPase proteins have been shown to be involved in different stages of autophagy (Ao et al., 2014). Rab5 is involved in the translocation of the Class III PI3 kinase complex and delivery of LC3-II (Mizuno-Yamasaki et al., 2012). Rab8a, Rab24, Rab32, Rab33b, and Rab39b are all involved in autophagosome formation, assisting the elongation by the delivery of additional membrane via ATG9/ATG2/WIPI1/2 (Itoh et al., 2008; Munafo and Colombo, 2002). Rab7 is involved in autophagosome transport while Rab11 delivers multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) to the autophagosome, which appears to be required for maturation. Rab7, Rab8b, and Rab9 are involved in the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes, a process that may also require Rab24 (Gutierrez et al., 2004; Nozawa et al., 2012).

Rab1a is a member of the Rab GTPase family with a molecular weight of 23.5 kDa. Previous studies have shown that Rab1a is mainly located in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus and plays a role in transporting vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus (Stenmark, 2009). Increasing evidence has shown that Rab1a is involved in autophagy regulation, mediating trafficking of the ULK1 complex to the phagophore, and is involved in delivery of ATG9-positive membranes to the site of phagophore formation (Webster et al., 2016, 2018). Rab1a was also reported to be involved in viral infections, including hepatitis C virus (HCV), classical swine fever virus (CSFV), and vaccinia virus (VACV) (Bhattacharjee and Mukhopadhyay, 2022; Lin et al., 2018; Pechenick Jowers et al., 2015). However, the role of Rab1a in PRRSV infection is still unknown. In this study, we described the role of Rab1a in promoting PRRSV replication through the autophagy process. Briefly, PRRSV infection upregulated Rab1a expression and strengthened its interaction with ULK1, which, in turn, favored PRRSV replication by facilitating autophagy initiation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and virus

Marc-145 cells (an African green monkey kidney epithelial cell line, ATCC CRL-12,231) and HEK 293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Marc-145 cells stably expressing monkey Rab1a (Rab1a) or its mutant (Rab1a-N124I) were selected with puromycin (sc-205,821, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a concentration of 8 μg/mL. Pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PAMs) were collected from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) 4-week-old piglets (free of PRRSV, porcine circovirus type 2, pseudorabies virus, classical swine fever virus, swine influenza virus, porcine parvovirus, and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infections) as previously described (Lu et al., 2012). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA) or RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco USA) containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich, USA). The highly pathogenic PRRSV-2 isolate BB0907 (GenBank accession no. HQ315835.1), which was used for all experiments and was designated as “PRRSV” throughout this article (Zhang et al., 2013), was amplified and titrated in Marc-145 cells.

2.2. Plasmid construction

The Rab1a (GenBank accession no. NM_001257272.1) gene was amplified from Marc-145 cells (Macaca mulatta) by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). The amplified Rab1a fragment was ligated into the lentivector pCDH-EF1α-MCS (Systembio, USA) with a N-terminal FALG tag, resulting in pCDH-Flag-Rab1a (Flag-Rab1a). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to construct a variant of the Rab protein containing a single amino acid substitution (N124I) named as Falg-Rab1a-N124I. Mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange II XL (Stratagene, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.3. Antibodies

Mouse anti-β-actin (A5316) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse anti-Rab1a (#sc-377,201) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA). Rabbit anti-ULK1 (D8H5) (#8054), rabbit anti-Phospho-ULK1 (Ser317) (#37,762), rabbit anti-Flag (#14,793), anti-rabbit IgG-HRP-linked antibody (#7074), and anti-mouse IgG-HRP-linked antibody (#7076) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). Rabbit anti-LC3 (#14,600–1-AP) was purchased from Proteintech (USA). The antibody against PRRSV-N protein was described previously (Song et al., 2019).

2.4. siRNA knocking down

Three pairs of specific siRNAs separately for Rab1a (Rab1a-siRNA1, 5′-CAA AGA AAG UAG UAG ACU ACA-3′; siRNA2, 5′-GAU GAU ACA UAU ACA GAA AGC-3′; siRNA3, 5′-GGU UUG CAG AUG AUA CAU AUA-3′), ATG7 (ATG7-siRNA1, 5′-GCA UCA UCU UCG AAG UGA AGC-3′; siRNA2, 5′-GGU CAA AGG AUG AAG AUA ACA-3′; siRNA3, 5′-AGA GAA AGC UGG UCA UCA AUG-3′)), ULK1 (ULK1-siRNA1, 5′-UGU UCU ACG AGA AGA ACA AGA-3′; siRNA2, 5′-AGU GCA UUA ACA AGA AGA ACC-3′; siRNA3, 5′-AGU UCG AGU UCU CCC GCA AGG-3′)), and a non-specific control siRNA were designed by Biotend (Shanghai, China). Briefly, Marc-145 cells were transfected with siRNAs, and the knockdown efficiency was detected by western blotting.

2.5. qRT-PCR

The Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-tek, Shenzhen, China) was used to extract RNA from cells and synthesize cDNA. qPCR was performed in an ABI QuantStudio 6 Systems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using a SYBR-Green RT-PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation for 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. All the primer sequences used are as follows: Rab1a (Macaca mulatta), 5′- TTG GAA AGT CTT GCC TTC TT-3′ and 5′-TGC TGT GTC CCA TAT TTG AA-3′; β-actin (Macaca mulatta), 5′-CTC CAT CAT GAA GTG CGA CGT-3′ and 5′-GTG ATC TCC TTC TGC ATC CTG TC-3′. Duplicate samples of each transcript were analyzed, and the level of expression for all genes was normalized to that of β-actin. The results were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

2.6. Lentivirus transduction

For construction of stably expressed Rab1a or its mutant in Marc-145 cells, lentivirus was produced after transfection of pCDH-Flag-Rab1a, pcDH-Flag-Rab1a-N124I, or empty vector together with package plasmids (pCMV-VSV-G, pMDLg/pRRE, and pRSV-REV) in HEK-293T cells (Liu et al., 2021). Marc-145 cells were then infected with the lentivirus. At 16 h after infection, cells were overlaid with fresh medium. At 3 d after infection, the cells were selected with 8 μg/mL puromycin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). All experiments were performed within 2 weeks after lentiviral transduction. For transduction of Rab1a in PAMs, the lentiviral supernatants were collected and concentrated using a lentivirus concentration kit (Genomeditech Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The titers of lentivirus in HEK-293T cells were determined and used for PAMs transduction.

2.7. Western blotting

Cells were harvested and lysed with RIPA Lysis Buffer (Beyotime, China). Afterward, the lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min, and the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Target proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). The membrane was then blocked in 5% skim milk and incubated with indicated primary antibodies and secondary antibodies. Finally, the proteins on the membranes were observed using the Chemistar High-sig ECL western blotting substrate (Tanon, China) and developed on a Tanon 5200 system (China). The bands were quantitated using ImageJ 1.8.0 software (National Institutes of Health).

2.8. Co-immunoprecipitation

Infected Marc-145 cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer containing PMSF. For immunoprecipitation, 1 mL of whole cell lysate was incubated with 2 μg of the indicated antibody and 40 μL of protein A/G agarose beads on rollers overnight at 4°C. The agarose beads were washed three times with 1 mL PBS or RIPA buffer with PMSF. Finally, the samples were analyzed by western blotting.

2.9. Confocal microscopy

Marc-145 cells were grown on coverslips (Chemglass) and transfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 plasmid (Addgene #110,060) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sixteen hours post-transfection, cells were mock-infected or infected with PRRSV for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and then the nuclei were stained with DAPI (Invitrogen, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was observed by confocal microscopy (LSM800, Zeiss). The cytoplasmic LC3B puncta in cells were manually counted for at least 20 randomly selected cells.

2.10. Ethics statement

All animal experiments conformed to the rules of National Guidelines for Housing and Care of Laboratory Animals (China) and were performed after obtaining the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of NAU (permit no. IACECNAU20191002).

2.11. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). An unpaired two-tailed Student's t test was used. The P values were calculated from three biological replicates unless otherwise indicated in the legends. Data were reproduced in independent experiments as indicated in the figure legends.

3. Results

3.1. Rab1a is involved in PRRSV replication

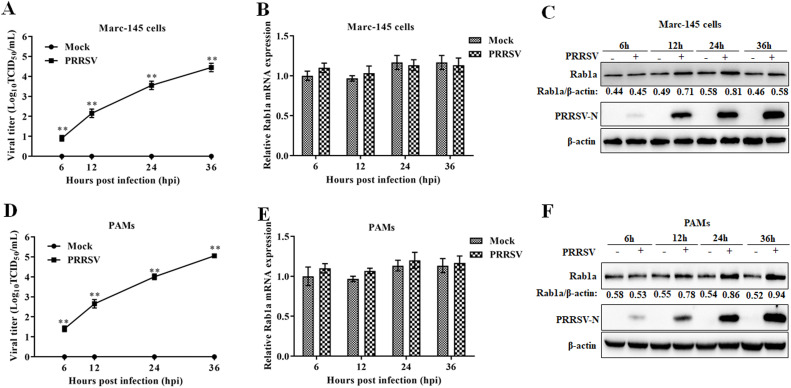

Previous studies have demonstrated that Rab1a is associated with some virus replication, such as HCV, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), VACV, and CSFV (Bhattacharjee and Mukhopadhyay, 2022; Lin et al., 2018; Pechenick Jowers et al., 2015; Zenner et al., 2011). Several pieces of evidence have implied that Rab1a may have certain effects on PRRSV infection (Hu et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2012). Here, we first determined whether Rab1a expression was correlated to PRRSV replication in Marc-145 cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, PRRSV grew steadily over the course of infection. Additionally, the expression of Rab1a protein was upregulated in a time-dependent manner compared to those in the mock infection groups, which were consistent with the trend of viral replication (Fig. 1C), whereas the mRNA expressions of Rab1a were almost stable during PRRSV infection (Fig. 1B). Next, we determined the Rab1a expression in PAMs during PRRSV infection. The pattern of Rab1a expression (i.e., stable mRNA expression but upregulated protein expression) in PAMs was consistent with those in Mac-145 cells (Fig. 1D-1F). These data indicated that Rab1a protein expression is upregulated during PRRSV infection, which may be involved in PRRSV replication.

Fig. 1.

PRRSV infection upregulates the expression of Rab1a. (A and D) Kinetics of viral growth. Marc-145 cells (A) or PAMs (D) were mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI of 0.1 and were then were harvested at indicated timepoints to determine the viral titers expressed as log10 TCID50/mL. (B and E) qRT-PCR was used to quantitate the level of Rab1a mRNA expression. Marc-145 cells (B) or PAMs (E) were treated as described in panel A or C, and then harvested for qRT-PCR analysis. The Rab1a levels were normalized to β-actin. (C and F) Western blot analysis was used to determine the level of Rab1a protein expression. Marc-145 cells (C) or PAMs (F) were treated as described in panel A or C, and harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against Rab1a, PRRSV-N, and β-actin. The protein bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ software and are presented as the amount of Rab1a normalized to β-actin in each sample. All the data were statistically analyzed by a two-tailed Student's t test (**P < 0.01) with SD (n = 3). The results are from three independent experiments.

3.2. Rab1a facilitates PRRSV replication

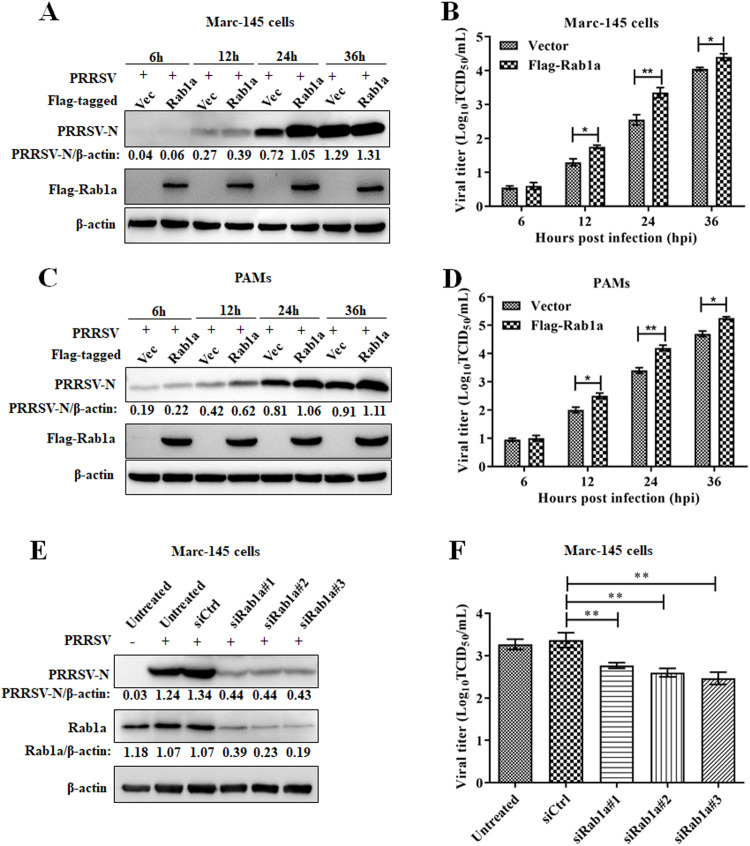

To determine the role of Rab1a in PRRSV replication, we evaluated the replication of PRRSV in Marc-145 cells stably expressed with Rab1a with the lentivirus system. As shown in Fig. 2A, the expression of PRRSV-N protein was elevated at 12 and 24 h post-infection in Rab1a stably expressed Marc-145 cells as compared to that in the cell line transduced with only lentivirus encoding the empty vector. Consistently, the replication of PRRSV at 12 and 24 h were significantly increased in Rab1a-overexpressed Marc-145 cells compared to those with the empty vector-expressed cells (Fig. 2B). Further, we detected the effect of Rab1a on PRRSV infection in PAMs. The results showed that transduction of Rab1a in PAMs also promoted PRRSV replication, reflecting by the PRRSV-N protein expression and viral titer (Fig. 2C and 2D). Conversely, the PRRSV-N protein expression and viral titer were decreased at 24 h post-infection in Marc-145 cells in which Rab1a was knocked down by siRNA (Fig. 2E and 2F). These data demonstrated that Rab1a plays a positive role in PRRSV replication.

Fig. 2.

Rab1a increases PRRSV replication. (A and C) Western blot assay for N protein in Marc-145 cells (A) or PAMs (C) that stably expressed Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector. Cells were mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 at different timepoints and then harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against PRRSV-N, Flag, and β-actin. The PRRSV-N levels were normalized to β-actin. (B and D) PRRSV titers in Marc-145 cells (B) or PAMs (D) stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector. Cells were treated as described in panel A or C, and then harvested for PRRSV titration by a TCID50 assay. (E) Western blot assay for N protein in Marc-145 cells with knock-down of Rab1a. Cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Rab1a and then mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. The cells were harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against PRRSV-N, Rab1a, and β-actin. The PRRSV-N and Rab1a levels were normalized to β-actin. (F) PRRSV titers in Marc-145 cells with Rab1a knockdown. Cells were treated as described in panel A and then harvested for PRRSV titration by a TCID50 assay. All the data were statistically analyzed by a two-tailed Student's t-test (**P < 0.01) with SD (n = 3). The results are from three independent experiments.

3.3. Rab1a promotes PRRSV replication via the autophagy pathway

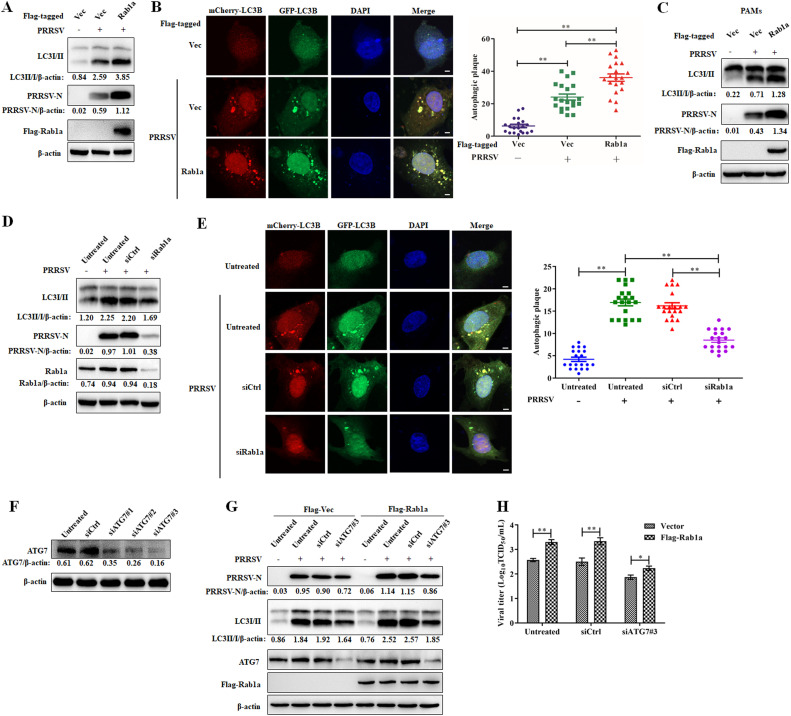

Rab1a, a member of the Ras superfamily of GTPases, has been demonstrated to be associated with the autophagy pathway (Webster et al., 2016, 2018). In addition, the autophagy process plays a role in enhancing PRRSV replication (Chen et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012). Thereby, we hypothesized that Rab1a promotes PRRSV replication via the autophagy pathway. To determine this, we first measured autophagy in Marc-145 cells with or without Rab1a stable expression after PRRSV infection. As shown in Fig. 3A, LC3II, a marker of autophagy induction, was significantly increased in cells stably carrying Rab1a as compared to that in empty vector-expressed cells after PRRSV infection. Additionally, PRRSV-N expression in Rab1a-overexpressing cells was higher than that in empty vector-expressed cells. The phenotype was also confirmed by the mCherry-LC3-GFP fluence test. The yellow dots of LC3 were significantly increased in cells with Rab1a as compared to that in the normal cells (Fig. 3B). In addition, the LC3II conversion was found to increase noticeably in PAMs transduced with Rab1a after PRRSV infection (Fig. 3C). Conversely, in Marc-145 cells with Rab1a knockdown by siRNA, both LC3II conversion and yellow dots of LC3 were decreased during PRRSV infection (Fig. 3D and E).

Fig. 3.

Rab1a promotes PRRSV infection via autophagy. (A and C) Western blot assay for autophagy induction in Marc-145 cells (A) or PAMs (C) stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector. Cells were mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h and then harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against LC3I/II, PRRSV-N, Flag, and β-actin. The LC3II/I and PRRSV-N levels were normalized to β-actin. (B) LC3B puncta formation in Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector. Cells were transfected with an mCherry-eGFP-LC3 plasmid for 16 h and then mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. Images were then captured. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue); scale bar, 10 μm. LC3B puncta formation were quantitated by Image J. Results represent the mean number ± SD of LC3B puncta per cell (n = 20). (D) Western blot assay for autophagy induction in Marc-145 cells with knock-down of Rab1a. Cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Rab1a and then mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. The cells were harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against LC3I/II, PRRSV-N, Flag, and β-actin. The LC3II/I and PRRSV-N levels were normalized to β-actin. (E) LC3B puncta formation in Marc-145 cells with knock-down of Rab1a. Cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Rab1a for 6 h and then treated as described in panel B. (F) Western blot was used to quantitate the level of ATG7 in siATG7#1-, siATG7#2-, siATG7#3-, or siCtrl-transfected Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector. Cells were transfected with siRNA targeting ATG7 or siCtrl for 24 h and then harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against ATG7 and β-actin. The ATG7 levels were normalized to β-actin. (G) Western blot assay for N protein in Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector by knocking down ATG7. Cells were transfected with siATG7#3 or siCtrl and then mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. The cells were harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against PRRSV-N, LC3I/II, ATG7, Flag, and β-actin. The ATG7 and LC3II/I levels were normalized to β-actin. (H) PRRSV titers in Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector by knocking down ATG7. Cells were treated as described in panel D and then harvested for PRRSV titration by a TCID50 assay (n = 3). All the data were statistically analyzed by a two-tailed Student's t test (**P < 0.01) with SD. The results are from three independent experiments.

The above results described a correlation between Rab1a and PRRSV replication. To further verify that Rab1a benefits PRRSV infection through autophagy, we tested PRRSV replication by knocking down ATG7, a hallmark gene of autophagy. As illustrated in Fig. 3F, three siRNAs all have the ability to abolish the expression of ATG7, in which siRNA#3 was the most effective. Next, we found that the increased PRRV-N protein expression in Rab1a-overexpressed Marc-145 cells was downregulated after knocking down ATG7 (Fig. 3G). Further, the TCID50 of PRRSV in the Rab1a group was higher than that in the vector group, while the difference was reduced after ATG7 expression was decreased (Fig. 3H). These data showed that Rab1a promotes PRRSV replication via autophagy.

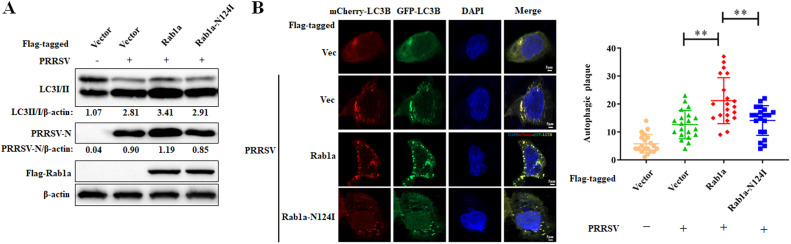

3.4. GTP-binding activity of Rab1a is essential for PRRSV-induced autophagy

Rab GTPases switch between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state (Zhang et al., 2019). To determine the role of Rab1a activity in regulating PRRSV-induced autophagy, we infected cells stably expressing Flag-tagged wild-type Rab1a (Rab1a WT) or dominant-negative guanine nucleotide binding–deficient mutant Rab1a-N124I (Zhang et al., 2019). As shown in Fig. 4A, the expression of PRRSV-N protein was increased in Flag-tagged wild-type Rab1a compared to that in empty vector. Interestingly, the increased PRRSV-N protein expression was dismissed in Rab1a-N124I stably expressed cells. As expected, LC3II/LC3I was significantly increased in Flag-tagged wild-type Rab1a, whereas no change was detectable in Rab1a-N124I. Consistently, the LC3 puncta formation observed in WT Rab1a were significantly increased as compared to that in empty vector-transfected cells. However, this phenotype was abolished in Rab1a-N124I (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrated that the GTP-binding activity of Rab1a is essential for PRRSV-induced autophagy.

Fig. 4.

GTPase activity of Rab1a is essential for PRRSV-induced autophagy. (A) Western blot assay for autophagy induction in Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged wild-type Rab1a or its GTPase inactive mutant (Rab1a-N124I). Cells were mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h and then harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against LC3I/II, PRRSV-N, Flag, and β-actin. The LC3II/I and PRRSV-N levels were normalized to β-actin. (B) LC3B puncta formation in Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged wild-type Rab1a or its GTPase inactive mutant (Rab1a-N124I). Cells were transfected with mCherry-GFP-LC3 plasmid for 16 h and then mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. Images were then captured. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue); scale bar, 10 μm. LC3B puncta formation were quantitated by Image J. Results represent the mean number ± SD of LC3B puncta per cell (n = 20). The results are from three independent experiments.

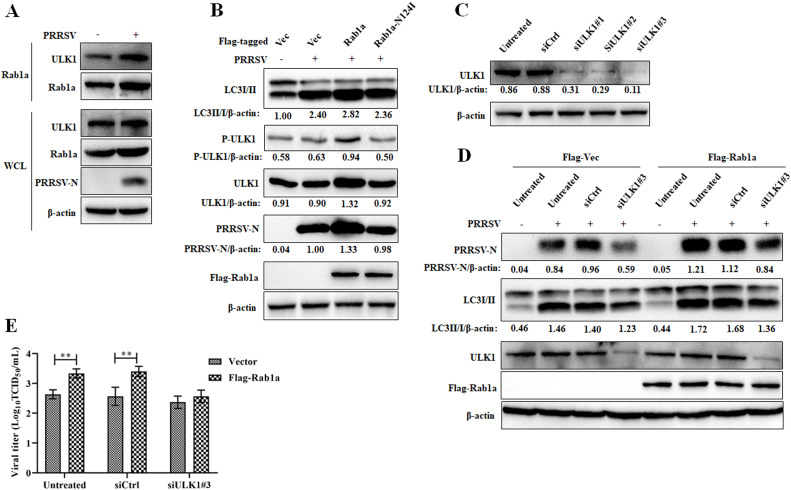

3.5. Rab1a enhances PRRSV-induced autophagy by interacting with ULK1

It has been demonstrated that Rab1a participates in autophagy by interacting with ULK1 (Webster et al., 2016, 2018). Therefore, we hypothesized that Rab1a promotes PRRSV-induced autophagy by interacting with ULK1. To test this, we analyzed Rab1a-ULK1 binding in Marc-145 cells that were mock-infected or infected with PRRSV. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, the amount of ULK1 precipitated by Rab1a in PRRSV-infected cells was increased compared to that in mock-infected cells. One of the essential steps of ULK1 activation is autophosphorylation (Kim et al., 2011). Next, we tested the role of Rab1a in ULK1 phosphorylation after PRRSV infection. In wild-type Rab1a-overexpressed cells, PRRSV infection induced the phosphorylation of ULK1. However, in the GTPase inactive mutant Rab1a-N124I-overexpressed cells, the phosphorylation of ULK1 was abolished (Fig. 5B). Finally, we tested the role of ULK1 and Rab1a promoting PRRSV infection. We designed small-interfering RNAs that targeted ULK1. The results showed that siULK1#3 was the most efficient (Fig. 5C). Using siULK1#3 to reduce ULK1 expression, we found that ULK1 expression played a positive role in Rab1a promoting PRRSV replication, as reflected by the decreased PRRSV-N expression and PRRSV titer in ULK1-knocked down cells (Fig. 5D and E). These results demonstrated that Rab1a-ULK1 binding is essential for PRRSV replication.

Fig. 5.

Rab1a facilitates PRRSV-induced autophagy by interacting with ULK1. (A) PRRSV infection strengthened the interaction between Rab1a and ULK1. Marc-145 cells were infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h and then harvested for co-IP with anti-Rab1a. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) and precipitated proteins were probed with antibodies against Rab1a, ULK1, PRRSV-N, and β-actin. (B) Rab1a promotes ULK1 phosphorylation dependent on its GTP-binding activity in PRRSV infection. Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged wild-type Rab1a or its GTPase inactive mutant (Rab1a-N124I) were infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. Cells were harvested for western blot with antibodies against LC3I/II, P-ULK1 ULK1, PRRSV-N, Flag, and β-actin. The LC3II/I, P-ULK1, ULK1 and PRRSV-N levels were normalized to β-actin. (C) Western blot was used to quantitate the level of ULK1 in siULK1#1-, siULK1#2-, siULK1#3-, or siCtrl-transfected Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector. Cells were transfected with siRNA targeting to ULK1 or siCtrl for 24 h and then harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against ULK1 and β-actin. The ULK1 levels were normalized to β-actin. (D) Western blot assay for N protein in Marc-145 cells stably expressed with Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector by knocking down ULK1. Cells were transfected with siULK1#3 or siCtrl and then mock-infected or infected with PRRSV at an MOI 0.1 for 24 h. The cells were harvested for western blot analysis with antibodies against PRRSV-N, LC3I/II, ULK1, Flag, and β-actin. The PRRSV-N and LC3II/I levels were normalized to β-actin. (E) PRRSV titers in Marc-145 cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Rab1a or an empty vector by knocking down ULK1. Cells were treated as described in panel D and then harvested for PRRSV titration by a TCID50 assay. All the data were statistically analyzed by a two-tailed Student's t-test (**P < 0.01) with SD (n = 3). The results are from three independent experiments.

4. Discussion

Several studies have reported that PRRSV has strategies to exploit autophagy for its own replication (Chen et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012). However, the mechanism by which this exploitation occurs is still unclear. In the present study, we showed that PRRSV infection upregulated Rab1a expression in Marc145 cells. Further, Rab1a was demonstrated to play a positive role in PRRSV replication by overexpression or silencing of Rab1a. Moreover, we showed Rab1a promoted PRRSV-induced autophagy. Mechanically, PRRSV infection strengthened the Rab1a-ULK1 interaction, thereby facilitating the autophagy process. Overall, this study revealed the function of Rab1a in PRRSV replication, which opened a new avenue for the PRRSV-host interaction and highlighting alternative methods to control the disease.

The Rab GTPase protein family contains over 60 human Rab proteins. Rab1a is mainly located in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, which plays a role in transporting vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus (Galea et al., 2015; Stenmark, 2009). Previous work has revealed a role for Rab1a in the life cycles of some viruses. Rab1a is required for the trafficking of viral envelope glycoproteins of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Nachmias et al., 2012) and HSV-1 (Zenner et al., 2011), highlighting its role in maintenance of a functional Golgi. In contrast, Rab1a plays a direct role in HCV replication, interacting with the viral protein NS5A and promoting lipid droplet formation (Nevo-Yassaf et al., 2012; Sklan et al., 2007). CSFV utilizes viral NS5A and Rab1A work cooperatively during its particle assembly (Lin et al., 2018). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that Rab1a is involved in autophagy regulation (Webster et al., 2016, 2018). However, the role of Rab1a in virus-induced autophagy has not been yet defined. Here, we found that Rab1a participates in PRRSV-induced autophagy. PRRSV infection upregulates Rab1a expression and strengthens the interaction between Rab1a and ULK1. Interestingly, we detected that Rab1a protein expression was upregulated, whereas Rab1a mRNA expression was stable. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the posttranslational modification (PTM) of proteins that occurs during the later stage of protein biosynthesis. It has been reported that the ubiquitination of proteins is crucial for controlling protein stability, localization, and conformation (Foot et al., 2017; Titapiwatanakun and Murphy, 2009). Thus, we hypothesized that Rab1a underwent ubiquitination during PRRSV infection, which will be investigated in the future.

The ULK1 complex is under direct regulation by the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) (Dunlop et al., 2011). Under nutrient-rich conditions, mTORC1 interacts with ULK1 and directly phosphorylates ATG13 and ULK1 at inhibitory sites to suppress the kinase activity of the complex (Hosokawa et al., 2009a). When under stimulation, the loss of mTORC1 inhibitory action allows ULK1 to phosphorylate FIP200, ATG13, and ATG101 at multiple sites (Park et al., 2016), resulting in full activation of the ULK1 complex. We found that Rab1a interacted with ULK1, which is consistent with a previous study (Webster et al., 2016). However, the connections between Rab1a and mTORC1 or other autophagy-associated genes are still unclear, which will be explored in future studies. Notably, we found that the Rab1a GTPase inactive mutant showed minimal PRRSV-induced autophagy, indicating the importance of GTPase activity of Rab1a. Moreover, our results showed that total and phosphorylated ULK1 expression was upregulated upon PRRSV infection in Rab1a-overexpresssing wild-type cells, while this phenomenon was abolished in Rab1a-N124I-overexpressed cells. These data suggested that a GTP-bound state of Rab1a is preferential in ULK1 activation, which was consistent with a previous study (Webster et al., 2016). C9orf72 has been reported to be a Rab1a effector that interacts with ULK1 (Webster et al., 2018). However, the role of C9orf72 in PRRSV-induced autophagy still needed to be explored in the future.

Taken together, the present study revealed that Rab1a is a crucial host factor recruited by PRRSV-induced autophagy and plays a pro-viral role in viral replication. Furthermore, our findings provide new insights in elucidating the regulatory mechanism of autophagy, which is essential to understanding the pathophysiology of PRRS.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chenlong Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis. Feifei Diao: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Zicheng Ma: Validation, Formal analysis. Jie Zhang: Validation, Formal analysis. Juan Bai: Writing – review & editing. Hans Nauwynck: Writing – review & editing. Ping Jiang: Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Xing Liu: Conceptualization, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank for the technical support provided by the Instrument Platform of Institute of Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Nanjing Agricultural University.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (32230103), and startup funding form the Nanjing Agricultural University (090-804125).

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Ao X., Zou L., Wu Y. Regulation of autophagy by the Rab GTPase network. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:348–358. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee C., Mukhopadhyay A. Generation of fluorescent HCV pseudoparticles to study early viral entry events- involvement of Rab1a in HCV entry. Virusdisease. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s13337-022-00770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Fang L., Wang D., Wang S., Li P., Li M., Luo R., Chen H., Xiao S. Induction of autophagy enhances porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication. Virus Res. 2012;163:650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop E.A., Hunt D.K., Acosta-Jaquez H.A., Fingar D.C., Tee A.R. ULK1 inhibits mTORC1 signaling, promotes multisite Raptor phosphorylation and hinders substrate binding. Autophagy. 2011;7:737–747. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foot N., Henshall T., Kumar S. Ubiquitination and the Regulation of Membrane Proteins. Physiol. Rev. 2017;97:253–281. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea G., Bexiga M.G., Panarella A., O'Neill E.D., Simpson J.C. A high-content screening microscopy approach to dissect the role of Rab proteins in Golgi-to-ER retrograde trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:2339–2349. doi: 10.1242/jcs.167973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganley I.G., Lam du H., Wang J., Ding X., Chen S., Jiang X. ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:12297–12305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M.G., Munafo D.B., Beron W., Colombo M.I. Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2687–2697. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T., Takamura A., Kishi C., Iemura S., Natsume T., Guan J.L., Mizushima N. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N., Hara T., Kaizuka T., Kishi C., Takamura A., Miura Y., Iemura S., Natsume T., Takehana K., Yamada N., Guan J.L., Oshiro N., Mizushima N. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1981–1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N., Sasaki T., Iemura S., Natsume T., Hara T., Mizushima N. Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy. 2009;5:973–979. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Wu X., Feng W., Li F., Wang Z., Qi J., Du Y. Cellular protein profiles altered by PRRSV infection of porcine monocytes-derived dendritic cells. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;228:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T., Fujita N., Kanno E., Yamamoto A., Yoshimori T., Fukuda M. Golgi-resident small GTPase Rab33B interacts with Atg16L and modulates autophagosome formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:2916–2925. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanasios E., Stapleton E., Manifava M., Kaizuka T., Mizushima N., Walker S.A., Ktistakis N.T. Dynamic association of the ULK1 complex with omegasomes during autophagy induction. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:5224–5238. doi: 10.1242/jcs.132415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kundu M., Viollet B., Guan K.L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Zhuang J., Wang J., Han L., Sun Z., Xiao Y., Ji G., Li Y., Tan F., Li X., Tian K. Outbreak Investigation of NADC30-Like PRRSV in South-East China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2016;63:474–479. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Wang C., Liang W., Zhang J., Zhang L., Lv H., Dong W., Zhang Y. Rab1A is required for assembly of classical swine fever virus particle. VirologyVirology. 2018;514:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Qin Y., Zhou L., Kou Q., Guo X., Ge X., Yang H., Hu H. Autophagy sustains the replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory virus in host cells. VirologyVirology. 2012;429:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Ma Y., Voss K., van Gent M., Chan Y.K., Gack M.U., Gale M., Jr., He B. The herpesvirus accessory protein gamma134.5 facilitates viral replication by disabling mitochondrial translocation of RIG-I. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q., Bai J., Zhang L., Liu J., Jiang Z., Michal J.J., He Q., Jiang P. Two-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) labeling approach revealed first proteome profiles of pulmonary alveolar macrophages infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:2890–2903. doi: 10.1021/pr201266z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeed S.T., Majeed R., Andrabi K.I. Expanding the view of the molecular mechanisms of autophagy pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jcp.30819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer C.A., Kaliappan A., Dennis P.B. A novel, human Atg13 binding protein, Atg101, interacts with ULK1 and is essential for macroautophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5:649–662. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno-Yamasaki E., Rivera-Molina F., Novick P. GTPase networks in membrane traffic. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012;81:637–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052810-093700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo D.B., Colombo M.I. Induction of autophagy causes dramatic changes in the subcellular distribution of GFP-Rab24. Traffic. 2002;3:472–482. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias D., Sklan E.H., Ehrlich M., Bacharach E. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope proteins traffic toward virion assembly sites via a TBC1D20/Rab1-regulated pathway. Retrovirology. 2012;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann E.J., Kliebenstein J.B., Johnson C.D., Mabry J.W., Bush E.J., Seitzinger A.H., Green A.L., Zimmerman J.J. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2005;227:385–392. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo-Yassaf I., Yaffe Y., Asher M., Ravid O., Eizenberg S., Henis Y.I., Nahmias Y., Hirschberg K., Sklan E.H. Role for TBC1D20 and Rab1 in hepatitis C virus replication via interaction with lipid droplet-bound nonstructural protein 5A. J. Virol. 2012;86:6491–6502. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00496-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa T., Aikawa C., Goda A., Maruyama F., Hamada S., Nakagawa I. The small GTPases Rab9A and Rab23 function at distinct steps in autophagy during Group A Streptococcus infection. Cell. Microbiol. 2012;14:1149–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.M., Jung C.H., Seo M., Otto N.M., Grunwald D., Kim K.H., Moriarity B., Kim Y.M., Starker C., Nho R.S., Voytas D., Kim D.H. The ULK1 complex mediates MTORC1 signaling to the autophagy initiation machinery via binding and phosphorylating ATG14. Autophagy. 2016;12:547–564. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1140293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechenick Jowers T., Featherstone R.J., Reynolds D.K., Brown H.K., James J., Prescott A., Haga I.R., Beard P.M. RAB1A promotes Vaccinia virus replication by facilitating the production of intracellular enveloped virions. VirologyVirology. 2015;475:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein D.C., Bento C.F., Deretic V. Therapeutic targeting of autophagy in neurodegenerative and infectious diseases. J. Exp. Med. 2015;212:979–990. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklan E.H., Serrano R.L., Einav S., Pfeffer S.R., Lambright D.G., Glenn J.S. TBC1D20 is a Rab1 GTPase-activating protein that mediates hepatitis C virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:36354–36361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., Kikkert M., Fang Y. Arterivirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:2141–2163. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.056341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Bai J., Liu X., Nauwynck H., Wu J., Liu X., Jiang P. S100A9 regulates porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication by interacting with the viral nucleocapsid protein. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;239 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.X., Huang L., Wang R., Yu Y.L., Li C., Li P.P., Hu X.C., Hao H.P., Ishag H.A., Mao X. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus induces autophagy to promote virus replication. Autophagy. 2012;8:1434–1447. doi: 10.4161/auto.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian K., Yu X., Zhao T., Feng Y., Cao Z., Wang C., Hu Y., Chen X., Hu D., Tian X., Liu D., Zhang S., Deng X., Ding Y., Yang L., Zhang Y., Xiao H., Qiao M., Wang B., Hou L., Wang X., Yang X., Kang L., Sun M., Jin P., Wang S., Kitamura Y., Yan J., Gao G.F. Emergence of fatal PRRSV variants: unparalleled outbreaks of atypical PRRS in China and molecular dissection of the unique hallmark. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titapiwatanakun B., Murphy A.S. Post-transcriptional regulation of auxin transport proteins: cellular trafficking, protein phosphorylation, protein maturation, ubiquitination, and membrane composition. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:1093–1107. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C.P., Smith E.F., Bauer C.S., Moller A., Hautbergue G.M., Ferraiuolo L., Myszczynska M.A., Higginbottom A., Walsh M.J., Whitworth A.J., Kaspar B.K., Meyer K., Shaw P.J., Grierson A.J., De Vos K.J. The C9orf72 protein interacts with Rab1a and the ULK1 complex to regulate initiation of autophagy. EMBO J. 2016;35:1656–1676. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster C.P., Smith E.F., Grierson A.J., De Vos K.J. C9orf72 plays a central role in Rab GTPase-dependent regulation of autophagy. Small GTPases. 2018;9:399–408. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2016.1240495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenner H.L., Yoshimura S., Barr F.A., Crump C.M. Analysis of Rab GTPase-activating proteins indicates that Rab1a/b and Rab43 are important for herpes simplex virus 1 secondary envelopment. J. Virol. 2011;85:8012–8021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00500-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Liu J., Bai J., Wang X., Li Y., Jiang P. Comparative expression of Toll-like receptors and inflammatory cytokines in pigs infected with different virulent porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates. Virol. J. 2013;10:135. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Bai J., Hou H., Song Z., Zhao Y., Jiang P. A novel recombinant porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus with significant variation in cell adaption and pathogenicity. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;208:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang L., Lv Y., Jiang C., Wu G., Dull R.O., Minshall R.D., Malik A.B., Hu G. The GTPase Rab1 Is Required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and inflammatory lung injury. J. Immunol. 2019;202:194–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Wang Z., Ding Y., Ge X., Guo X., Yang H. NADC30-like strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:2256–2257. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.150360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.