Abstract

Protein phosphorylation is an essential post-translational modification that regulates many aspects of cellular physiology, and dysregulation of pivotal phosphorylation events is often responsible for disease onset and progression. Clinical analysis on disease-relevant phosphoproteins, while quite challenging, provides unique information for precision medicine and targeted therapy. Among various approaches, mass spectrometry (MS)-centered characterization features discovery-driven, high-throughput and in-depth identification of phosphorylation events. This review highlights advances in sample preparation and instrument in MS-based phosphoproteomics and recent clinical applications. We emphasize the preeminent data-independent acquisition method in MS as one of the most promising future directions and biofluid-derived extracellular vesicles as an intriguing source of the phosphoproteome for liquid biopsy.

Keywords: Phosphoproteomics, Mass spectrometry, Data-independent acquisition, Tissue/liquid biopsy, Extracellular vesicle

1. Clinical relevance of protein phosphorylation

As the major players in cellular processes, proteins are responsible for almost every biomolecular process and cellular function [1, 2]. Over millions of years of evolution, proteins in living organisms have acquired more diversified structures to accomplish increasingly complex biological functions. Encoding additional amino acid sequences and translating new proteins is costly and impractical. Instead, evolution developed the ability to implement functional groups onto existing proteins to achieve specific aims, namely post-translational modifications (PTMs) [3–5]. As a standout in PTMs, protein phosphorylation is one of the most ubiquitous modifications due to its indispensability in modulating pathophysiological properties [6, 7].

Intrinsically bearing reactive hydroxyl groups, serine (Ser), threonine (Thr), and tyrosine (Tyr) are able to stably link phosphate groups to their amino acid residues [8, 9]. With kinases as “writers” and phosphatases as “erasers”, phosphate groups can be enzymatically attached or detached to the designated substates, concomitantly with the conversion between adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) [10, 11]. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, occurring at all times in living organisms, provide dynamic equilibrium and reversibility. Protein conformational transitions are induced by phosphorylation, and consequently, alter protein functionalities, protein-protein interactions, cellular localizations, and many other physiological events. In the view of phenotypes, protein phosphorylation shapes the biological status and behaviors of living organisms by broadly organizing signaling networks and their interplay.

Meanwhile, uncontrollable dysregulation of protein phosphorylation is one of the main reasons for multiple disease formation, such as cancer, diabetes, and neurodegeneration [12–14]. For disease treatment, numerous attempts to intervene in this dysregulation have claimed groundbreaking success. For example, inhibitors of certain druggable kinases have appeared as successful alternatives for effective disease remission [15–17]. Besides, in the realm of clinical analysis, protein phosphorylation detection supplies another layer for disease diagnosis and monitoring [18, 19].

Traditional technologies are focused on antibody-based detection to profile specific target phosphoproteins and have been utilized in clinical practice to some extent (Fig. 1). For example, reverse phase protein array (RPPA) enables sensitive and quantitative measurements of several common phosphoproteins, such as protein kinase B (pAKT), signal transducer and activator of transcription (pSTAT), mechanistic target of rapamycin (p-mTOR), and epidermal growth factor receptor (pEGFR) from hundreds of tumor biopsies simultaneously [20–22]. Another immunoassay termed phospho-specific flow cytometry is quite effective for liquid tumors, such as leukemia. Analysis of pSTAT abundance levels can suggest the likelihood of a patient’s responsiveness to drug therapeutics [23]. However, the limitations of all immunoassay formats are notable [19, 24]. The availability of highly specific antibodies remains a problem, especially for phosphoprotein detection. The promiscuity due to cross-reactivity is a particularly severe concern due to phosphosite variation and phosphoprotein heterogeneity. Moreover, poor sensitivity of come antibodies hinders the detection limit and leads to semi-quantitative outcomes. Last but not least, although hundreds of analytes can be processed in some formats, only a few phosphoproteins can be examined at one time. Altogether, there is a demand to measure a larger set of phosphoproteins engaged in excessive signaling pathways with better quantitative capabilities.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of clinical analytical approaches about phosphoproteins and phosphoproteomics.

2. Clinical phosphoproteomics

Systems biology attempts to understand multiple various biomolecules simultaneously [25, 26]. Instead of focusing only on several recognized phosphoprotein targets with a well-known disease involvement, phosphoproteomics opens an avenue to discovery-driven profiling of signaling with high-throughput capabilities (Fig. 1). In many instances where the underlying biology is not well understood, it is helpful to circumvent any knowledge-based antibody selection and profile the complete phosphoproteome in an unbiased and comprehensive manner as the starting point for the identification of true disease effectors and mediators. Furthermore, phosphoproteomic assessment emphasizes comprehensive analyses of thousands of phosphoproteins, which can serve as global indicators of activated networks and inter-pathway crosstalk.

For specific clinical analysis, phosphoproteome can reveal unique messages for precision medicine and personalized surveillance and therapeutic treatment. Compared to general proteome, phosphoproteome analysis is often more relevant for functional profiling of signaling networks and brings us one step closer to the understanding of actual disease phenotypes. Herein, we aim to introduce some recent studies and provide the readers with meaningful insights as well as the trends of clinical phosphoproteomics based on our understanding in this field. For many diseases that are extensively regulated by protein phosphorylation, phosphoproteomics offers an effective opportunity to illustrate the progression of such diseases as cancer, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Integrating phosphoproteomic analysis into routine use is necessary in this revolutionary era for healthcare and medication.

3. Mass spectrometry-based analysis of clinical phosphoproteomics

3.1. Sample preparation in phosphoproteomics

Mass spectrometric technologies have recently demonstrated their unique capabilities in certain clinical tests, for example, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to screen newborn metabolic disorders by targeting several small-molecule metabolites from biofluidic droplets or dried spots on filter paper [27, 28]. This has become a worldwide test because of the irreplaceable advantages offered by MS, in particular featuring high speed, accuracy, and sensitivity. Equally valuable for phosphoproteomics, MS empowers antibody-free high-confidence phosphorylation detection and relatively accurate phosphosite localization. Once coupled to liquid chromatography (LC), seamless LC-MS/MS enables upfront separation based on molecular properties and further fulfills the comprehensive analysis promise of “omics” [29–32].

To date, the MS-based top-down proteomics approach is insufficient for detailed proteome landscaping due to the lack of universal LC separation methods and versatile ionization and fragmentation MS parameters for heterogeneous proteins [33, 34]. The same bottlenecks exist in phosphoproteomics as well. As a result, the dominant bottom-up scheme has been widely applied in the field of phosphoproteomics, since the easy-to-handle shorter phosphopeptides are relatively uniform in the LC-MS/MS analysis aspects. In this case, C18 column as apparatus of reversed-phase LC, under the nanoflow operations, serves the phosphoproteomic profiling in most studies [35, 36]. However, the relatively arduous and time-consuming sample preparation workflow constricts phosphoproteomic deployment for clinical analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

General workflow of clinical sample preparation for bottom-up phosphoproteomics via LC-MS/MS.

As the first step in sample preparation, a high-standard storage environment predates any phosphoproteome processing. Typically, temporary storage at −80 °C is sufficient for most cells and biofluids. After tissue harvesting, the phosphoproteome can be relatively well-preserved upon instant snap-freezing to deactivate enzymes like phosphatases [37–39]. Conventional hours-long preparation of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue biopsies leaves the inherent phosphoproteome susceptible to enzymatic degradation and can lead to significant signal loss [40]. Nonetheless, although preferred, liquid nitrogen or other ultralow-temperature cryopreservation provision is not always available in surgical rooms.

Protein extraction with the presence of phosphatase inhibitors is standardized for global phosphoproteomics analysis. Sonication in the urea or guanidine hydrochloride denaturing solutions for cell lysis is adequate to release most cytosol proteins; but for organelle or membrane protein extraction, detergent-aided lysis is recommended. Notably, any addition of protease inhibitors during this step can suppress the subsequent protease cleavage if no further clean-up step is applied. Tissue samples warrant complete homogenization for efficient protein extraction, and biofluids may require top-abundant protein depletion to reduce sample complexity. Denaturation, reduction and alkylation processes are typically needed to generate the protein linear structure for complete digestion. Instead of the traditional sequential operations with dithiothreitol (DTT) followed by iodoacetamide (IAA), some studies recommend simultaneous combination of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP·HCl) and chloroacetamide under a high temperature and short time [41, 42]. In MS-based proteomic studies, proteolytic digestion is often achieved with typsin or combining with Lys-C for optimal results. After peptide cleanup by C18 cartridge or other approaches, samples are ready for label-free MS acquisition; alternatively, peptides are chemically labeled using stable isotope tags such as dimethylation or tandem mass tag labeling (TMT).

Finally, sub-stoichiometrically phosphorylated peptides are enriched to avoid being overwhelmed by unmodified peptides in the MS analysis. Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) is one of the most widespread enrichment methods, and the polymer-based metal ion affinity capture (PolyMAC) technique developed by our group emerged as a suitable alternative offering high specificity and greater capacity for phosphopeptide retrieval [43–47]. Phosphate groups on peptides are labile, so we advocate for LC-MS analysis immediately after the phosphopeptide enrichment step is finished.

3.2. Development of mass spectrometric strategies for quantitative phosphoproteomics

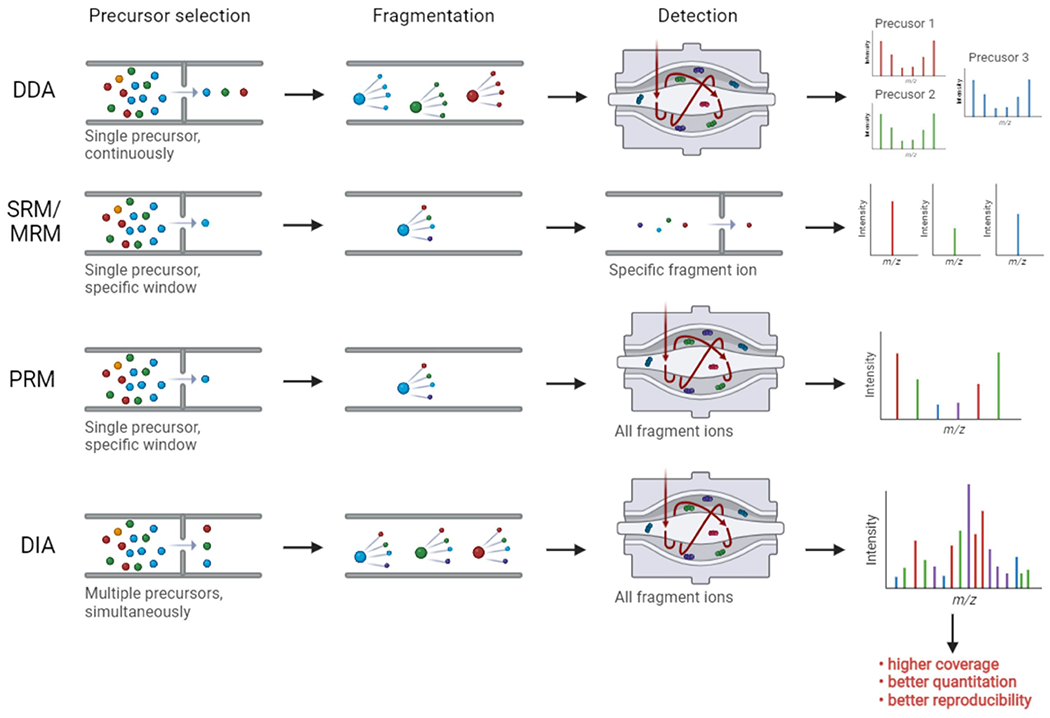

Hydrophilic phosphate groups tend to reduce the ionization efficiency of phosphopeptides, which is a barrier to phosphoproteome analysis. Especially after suboptimal phospho-enrichment, precursor ions derived from phosphopeptides are mostly masked, leading to a significant reduction in overall identification and phosphosite localization. Within a duty cycle in the traditional data-dependent acquisition (DDA) analysis, precursor ions are quickly ranked according to their respective abundances. Then, the top 10-20 precursor ions are successively sent to MS2 for fragmentation and peptide sequencing (Fig. 3) [48, 49]. Because of the limited numbers of stochastically picked precursors, DDA easily reaches the saturation for sequencing, thus reducing the protein coverage and resulting in poor quantitation as well. To address the quantitation and sensitivity issues, MS methods need to partially sacrifice the multiplexity and throughput. For example, several choices for targeted phosphoproteomic methods include selected reaction monitoring (SRM), multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), and parallel reaction monitoring (PRM). These enable improved quantitation and sensitivity for phosphosite validation and quantitation (Fig. 3) [50, 51]. But they rely on the hypothesis-driven analysis made from the discovery phase and enable only small-scale profiling - usually up to several dozen of phosphopeptides at a time. Thus, there is a clear need to develop an unbiased comprehensive MS approach for quantitative global phosphoproteomics.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of different MS methodologies: DDA, targeted proteomic approaches (SRM, MRM, PRM) and DIA.

To address these concerns, data-independent acquisition (DIA) has recently gained traction in the community due to improved quantitation, higher speed, and better protein coverage and identification (Fig. 3) [52, 53]. In principle, DIA is achieved by co-fragmenting all precursor ions within specific m/z windows and the complicated fragmentation information is leveraged for multi-peptide sequencing. Compared to DDA, DIA has demonstrated better quantitative performance with multiple fragment ions at the MS/MS level [54]. Successful DIA analysis relies on the power of bioinformatic algorithms. Putatively, another challenge lies in the accurate and high-confidence localization of modification sites for phosphoproteomics via DIA. In 2020, Bekker-Jensen et.al. published a rapid and reproducible DIA-based LC-MS/MS approach for global phosphoproteome identification and quantitation [55]. Starting from the HeLa cell line, extracted protein samples were denatured and digested, the tryptic peptides were enriched by IMAC magnetic beads, and resulting eluates were loaded onto LC-MS/MS (Table 1). After the optimization of collision energy, m/z window selection, cycle time as well as pioneering DIA-specific phosphosite localization algorithm implemented in the Spectronaut search engine, using only 15-min unfractionated gradients in the DIA mode there were able to profile around 14,000 phosphosites without marked quantitation disturbance. Notably, direct DIA analysis without aid from spectral libraries also provided similar analytical results compared to the mapped library-based DIA strategy. In a follow-up study, Kitata et.al. utilized lung cancer cell lines and patient-derived tissues to establish a rich project-oriented phosphoproteome spectral library, containing 88,107 phosphosites for any future analyses (Table 1) [56]. Using this strategy, over 38,000 phosphosites were quantified in single-shot 2-hour-gradient DIA runs, unveiling the amenability of sensitive DIA for in-depth coverage of phosphoproteome.

Table 1.

Overview of phosphoproteomics studies

| Sample types | Sample preparation | LC-MS methods | Identification number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa cells | • Lysis buffer (6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 5 mM TCEP, 10 mM CAA, 100 mM Tris pH 8.5) • Sep-Pak C18 cartridge • Ti-IMAC magnetic beads |

• 15-min LC gradient • DirectDIA |

>14,000 phosphosites | [55] |

| Lung adenocarcinoma cells | • Lysis buffer (1% SL buffer, 10 mM TCEP, 40 mM CAA, protease inhibitor, and phosphatase inhibitors in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5) • Reversed-phase StageTips • IMAC StageTip |

• 2-hour LC gradient • Library-based DIA |

>34,000 phosphosites | [56] |

| Lung cancer tissue | • Lysis buffer (12 mM SDC, 12 mM SLS, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 9.0, phosphatase cocktail inhibitors, and EDTA-free protease cocktail inhibitor) • Methanol/chloroform protein precipitation • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM DTT and 50 mM IAA • Reversed-phase StageTips • IMAC StageTip |

• 2-hour LC gradient • Library-based DIA |

32,407 phosphosites | [56] |

| HeLa cells | • Lysis buffer (2% SDC in 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM TCEP and 40 mM CAA • Sepax Extraction columns • Fe(III)-NTA |

• 21-min LC gradient • dia-PASEF mode • Library-based DIA |

46,136 phosphosites | [62] |

| HeLa cells | • Lysis buffer (4% SDC in 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM TCEP and 40 mM CAA • Sepax Extraction columns • TiO2 beads |

• 7-min LC gradient • dia-PASEF mode • DirectDIA |

>9,000 phosphopeptides | [63] |

| Vero E6 cells | • Lysis buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 150 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor, phosphatase inhibitors) • Reduction and alkylation by 4 mM TCEP and 10 mM IAA • Sep Pak tC18 cartridges • Ni-NTA Superflow beads |

• 2-hour LC gradient • Library-based DIA |

4,624 phosphosites | [69] |

| Human postmortem brain tissue | • Lysis buffer (8 M urea, 0.5% SDC, 1x PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail in 50 mM HEPES pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 5 mM DTT and 10 mM IAA • Sep-Pak C18 cartridge • TMT labelling • TiO2 beads |

• 2-hour LC gradient • TMT-DDA |

34,000 phosphosites | [73] |

| 3T3-L1 adipocytes | • Lysis buffer (6 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 25 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate, protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM DTT and 25 mM IAA • tC18 cartridges • TiO2 beads |

• 100-min LC gradient • Library-based DIA |

130 phosphosites | [85] |

| Plasma EVs | • Ultracentrifugation • Lysis buffer (12 mM SDC, 12 mM SLS, and phosphatase inhibitor mixture in 100 mM Tris·HCl at pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM TCEP and 40 mM CAA • Sep-Pak C18 cartridge • In-house-constructed IMAC tip |

• 60-min LC gradient • Label-free DDA |

9,643 phosphopeptides | [100] |

| Breast cancer cell-derived EVs | • Ultracentrifugation • Lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 5% glycerol, 0.1% nDodecyl-β-D-Maltoside, 0.2 mM DTT, 1.6 M urea, and phosphatase inhibitors) • C18 TopTips • Fe-NTA phosphopeptide enrichment kit |

• 65-min LC gradient • Label-free DDA |

2,003 phosphopeptides | [106] |

| Lung tissue EVs | • Ultracentrifugation • Lysis buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM NH4HCO3, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and phosphoSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) • Reduction and alkylation by 5 mM DTT and 10 mM IAA • Strata X C18 SPE column • TMT labelling • IMAC microspheres |

• 40-min LC gradient • TMT-DDA |

2,473 phosphopeptides | [107] |

| Urinary EVs | • EVtrap • Lysis buffer (12 mM SDC, 12 mM SLS, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail in 100 mM Tris·HCl at pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM TCEP and 40 mM CAA • Sep-Pak C18 cartridge • PolyMAC |

• 60-min LC gradient • Label-free DDA |

1,896 phosphopeptides | [108] |

| Urinary EVs | • EVtrap • Lysis buffer (12 mM SDC, 12 mM SLS, and phosphatase inhibitor mixture in 100 mM Tris·HCl at pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM TCEP and 40 mM CAA • C18 TopTips • PolyMAC |

• 60-min LC gradient • Label-free DDA |

10,620 phosphopeptides | [109] |

| Plasma EVs | • EVtrap • Lysis buffer (12 mM SDC, 12 mM SLS, and phosphatase inhibitor mixture in 100 mM Tris·HCl at pH 8.5) • Reduction and alkylation by 10 mM TCEP and 40 mM CAA • C18 TopTips • PolyMAC |

• 60-min LC gradient • Label-free DDA |

5,570 phosphopeptides | [110] |

Offering another tool for effective proteome detection and quantitation, Bruker Corporation® has recently developed trapped ion mobility spectrometry - quadrupole time of flight (timsTOF) mass spectrometer [57, 58]. Besides offering collisional cross section (CCS) as an additional dimension for precursor ion separation, the integration of DIA and technology of Parallel Accumulation Serial Fragmentation (PASEF) on the timsTOF platform, termed diaPASEF, facilitates highly sensitive and exhaustive proteomic analysis [59–61]. The key part is the trapped ion mobility (TIMS) device: it is equipped with an efficient precursor ion trap; and in a synchronized and ultra-rapid manner, it allows timely release to geometrically subsequent mass-filter-function quadrupole and collision cell for fragmentation. Simultaneously, the TOF analyzer empowers high-speed m/z read-out. Consequently, timsTOF achieves almost 100% duty cycle and ion utilization efficiency, thus resulting in significantly improved proteome analysis. Since this is a recently released instrument, we found only a few phosphoproteomic reports taking advantage of diaPASEF in the timsTOF mass spectrometer. For example, Skowronek et.al. employed diaPASEF in the timsTOF machine with a 21-minute LC gradient to quantitatively profile HeLa cell phosphoproteome (Table 1) [62]. Unprecedentedly, 46,136 phosphosites were quantified by searching against their project-specific library. Another investigation by Oliinyk et.al. demonstrated that diaPASEF was able to accurately quantify over 9,000 phosphopeptides within only a 7-min gradient (Table 1) [63]. Based on this evidence, we reason that diaPASEF in timsTOF enables fast, sensitive, and deep phosphoproteomics analysis and offers a great opportunity for extensive clinical phosphoproteome profiling.

4. Examples of clinical phosphoproteome research

Clinical applications of phosphoproteomics are promising but there are many challenges. A number of recent studies demonstrated it facilitates better understanding diseases and the development of precision medicine tactics. Here, we describe several such examples, ranging from contagious disease (COVID-19) and neurodegenerative disorder (AD) to diabetes and cancer. We particularly focus on the key role of MS in analysis and various sample sources for phosphoproteomics.

4.1. Investigation of phosphoproteome changes upon SARS-CoV-2 infection

The outbreak of COVID-19 has created a worldwide health emergency, demanding urgent research endeavors on understanding the virus biology and uncovering therapeutic strategies [64–66]. As the causative agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been explored in diverse aspects, but it has become necessary to fully comprehend the protein phosphorylation mechanisms of viral infection and the subsequent responses from host cell phosphoproteins [67, 68]. Bouhaddou et.al. centered their study on the cellular phosphoproteome changes upon SARS-CoV-2 infection, trying to uncover the responsive phosphorylation-dependent signaling pathways [69]. After a time-course viral infection of up to 24 hours, regulated phosphoproteome in Vero E6 cell was profiled by the DIA approach, resulting in 4,624 quantifiable human-orthologous phosphosites in total (Table 1). Within this survey, several important phosphorylation networks were found to be significantly regulated, influencing cellular response. For example, the prompted phosphorylation of specific substrate proteins such as heat shock protein beta-1, negative elongation factor E, and cAMP response element-binding protein indicated the activation of several upstream kinases in the p38/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling transduction pathway upon viral infection. As validation, researchers pre-treated the host cells with respective MAPK kinase inhibitors, such as MAPK11/14 inhibitor ralimetinib or MAPK13 inhibitor MAPK13-IN-1, prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the probing stage, some MAPK inhibitors were confirmed to block virus replication with negligible damage to host cell viability, similar to verified antiviral drugs. This report manifested the potential of phosphoproteomic interrogation to propose new therapeutic regimens to prevent infection and offer novel cures for COVID-19 patients.

4.2. Tissue phosphoproteome profiling of AD patients with brain diseases

In the clinical setting, “gold standard” tissue biopsy is the classic phosphoproteome workhorse for disease research as well as clinical diagnostics and therapeutic guidance [70, 71]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as one of the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders, is substantially attributed to the progression of critical phosphoproteins, such as hyperphosphorylated microtubule-associated protein tau (tau or MAPT), determining tauopathy [72]. Therefore, analyzing tissue phosphoproteome from AD patient brain tissues has become an important step in trying to decipher disease formation and identify therapies. Impartially surveying differently staged AD brain tissues, Bai et.al. identified over 34,000 phosphosites in total, notably including 56 phosphosites in the hyperphosphorylated tau protein (Table 1) [73]. According to 398 differentially expressed phosphoproteins, 28 kinases were enriched, indicating regulation of holistic phosphorylation events in AD. Other similar publications on extensive phosphoproteome profiling from large cohorts of brain tissues have also discovered new disease rationales and presented some actionable therapeutic targets for AD treatment [74, 75].

However, there remains a concern about the extreme heterogeneity of tissues, including brain tissues. For example, brain tissue is composed of five major cell subpopulations - neurons, astrocytes, microglia, endothelial and oligodendrocytes [76, 77]. Each cell or cell type may carry different combinations of proteome networks. This is the primary reason why the diversity of cellular-level proteome is hidden by conventional bulk analysis and why the field of a single cell or single cell type proteomics has become a rapidly emerging field [78–81]. However, single cell or cell type phosphoproteomics is even more challenging than traditional proteomics due to the extreme rarity and low level of protein phosphorylation. So far, only a limited number of studies have been published analyzing single cell phosphoproteome. A new single-cell barcode chip (SCBC) tool was proposed for sensitive proteome detection from a small amount of only ~1,000 cells [82, 83]. On this basis, Wei et.al. analyzed single cell phosphoproteome from glioblastoma patient-derived brain tissues in order to scrutinize the resistance to mTOR inhibition as treatment [84]. However, the essence of SCBC is still based on immunohistochemistry and researchers exquisitely defined a small-scope phosphoproteome analysis, possessing only nine phosphoproteins entangled in mTOR signaling coordination. Compared to large-scale MS methods, this SCBC approach missed the majority of the phosphorylation information from other signaling pathways, which could also supply important clues for the interpretation of drug resistance. Admittedly, trace amounts of phosphoproteins from single cell biospecimens challenge the detection limit and sensitivity of MS. However, we envision that continued improvements in MS technology will fill this technical gap and enable scale-up single cell phosphoproteome analysis.

4.3. Phosphoproteome explorations of insulin signaling and type 2 diabetes cases

The insulin signaling pathway serves as one of the primary anchors for scientific exploration and therapy development for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The insulin network is tightly regulated by a myriad of phosphoproteins and is dependent on the extensive activation of kinases. To examine this further, Parker et.al. used 3T3-L1 adipocytes as the model to discern insulin-related phosphoproteome in a proof-of-principle study [85]. By building a project-specific library, DIA-MS was successfully performed to profile differentially expressed phosphoproteins upon insulin stimulation (Table 1). As a result, 86 phosphoproteins in the insulin network were mined as downstream effectors, and the corresponding inhibitors on “master regulator’ kinases (e.g., AKT and mTOR) were verified to influence insulin signaling. In the end, the authors validated DIA as an effective, accurate, and reproducible large-scale quantitative method.

Batista et.al. and Haider et.al. moved the field one step closer to clinical relevance by leveraging the cutting-edge technique of differentiation of patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into skeletal muscle myoblasts [86, 87]. The “pseudo” clinical analysis uncovered the insulin signaling defects which were truly existing in each patient. However, such a complicated two-step iPSC-differentiation process involving cocktail-based transformation takes over three weeks. Even for the traditional clinical tumor tissue biopsy, it is very difficult to successively sample the tissue over a two-week span [88, 89]. This long interval along sample harvesting and preparation impedes short-term monitoring using daily tests and would likely miss real-time messaging needed to evaluate disease progression or treatment response. As an alternative solution, non-invasive liquid biopsy has the potential to enable early disease diagnosis or prognosis at the prodromal stage and longitudinal tracking for drug administration evaluation and adjustment. Nonetheless, for phosphorylation-related diseases, the detection of phosphoproteins in biofluids is greatly limited at the current stage. New solutions are needed to overcome this technical issue.

4.4. Profiling phosphoproteome landscape of circulating EVs for disease biomarkers

Detection of free/soluble phosphoproteins in bioliquids suffers greatly from the interference from phosphatases and other enzymes and a hodgepodge of high-abundant proteins that mask the useful signaling molecules [90]. Very limited numbers of phosphoproteins have been previously identified in biofluids, although few of them do appear to convey remarkable biological or pathological relevance [91–93]. One encouraging direction for the field is biofluid-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) as the source of disease-relevant phosphoproteins. EVs are comprised of two major categories: microvesicles/ectosomes (typically 0.1 - 1 μm) and exosomes (typically 30 - 100 nm), with both types being secreted from almost all cell types [94–97]. Released into a variety of biofluids (plasma, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, etc.), EVs carry cargoes like nucleic acids, lipids, metabolites, and proteins (including phosphoproteins), and circulate around the whole body to adaptatively command intercellular communication, immune response, biowaste offload and so on [98, 99]. Owing to the EV membranous structure, internal phosphoproteins are well-protected from outside phosphatases [100, 101]. Hence, we justify that released EVs partially reflect parental cell phosphoproteome, with relevant EV phosphoproteins serving as indicators to surveil phosphorylation-associated diseases (Fig. 1).

Our team demonstrated the identification of close to 10,000 unique phosphopeptides from ~2,000 phosphoproteins in EVs with a small volume of plasma (Table 1) [100]. Furthermore, 144 EV phosphoproteins were discovered as elevated in breast cancer patients and, eventually, a panel of four phosphoproteins was validated for its diagnostic potential, including Ral GTPase-activating protein subunit alpha-2, cGMP-dependent protein kinase 1, tight junction protein 2, and a nuclear transcription factor - X box-binding protein 1. Of note, all four of the potential phosphoprotein markers have been previously verified by tissue biopsy-based breast cancer surveys in independent experiments from other groups [102–105]. As a prerequisite in vivo study, Minic et al reported several known phosphorylated enzymes presenting in two breast cancer cell lines exclusively, but absent in a healthy breast cell line (Table 1) [106]. Another interesting study leveraged lung tumor EV phosphoproteome and unveiled phosphoproteins, especially phosphorylated kinases, as significant regulators or participants in lung cancer procession (Table 1) [107]. These findings suggest that EVs offer a preserved profile of important protein phosphorylation from the lesion, especially in cancerous cells.

Dissecting EV phosphoproteomes as the main focus in our group, we have recently reported the utility of using urinary EV-derived phosphoproteins as potential biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease (Table 1) [108, 109]. plasma-derived EV phosphoproteins as the potential source for renal cell carcinoma diagnosis (Table 1) [110] and distinct serum EV phosphoproteome to indicate diabetic pathobiology from a novel perspective [13]. In summary, EVs offer unprecedented potential for non-invasive phosphoproteome profiling and could enable targeted phosphoprotein detection using the preferred routine clinical analysis via liquid biopsy.

5. Conclusion and outlook

Many advances in clinical phosphoproteomics have been made over the past decades, and this field is relatively new and is expected to add a significant contribution to disease investigation. While MS-based techniques pave the way toward extensive and in-depth detection of phosphoproteomes, significant requirements for instrument sensitivity, computational power, and clinically-friendly bioanalytical methods raise additional challenges. Here in our review, we only selected limited sample types for phosphoproteome research on four different diseases, and the topics of data analysis and statistics are discussed briefly. Another part we have overlooked is the applications in clinics based on targeted phosphoproteomics, since the examples are limited at this stage. We attempt here to give a general view and a few examples that represent the current status and shed light on the future trends of clinical development from phosphoproteomics realm. Firstly, for any single cell or cell type analysis, the quality of cell sorting and rigorous stratification could have a substantial effect on the eventual success. Sensitive sampling is of particular importance for phosphoproteome detection since any substantial loss of targeted cells is more detrimental considering the intrinsically low phosphorylation levels. In addition, the defective specificity of cell sorting may lead to the capture of unrelated phosphoproteins and distort final quantitation. To perform single cell phosphoproteome analysis using LC-MS, every preparation step should be virtually error-free. Secondly, the DIA platform is revolutionary with extra support from timsTOF but demands powerful algorithms during the post-MS analysis. There is still room for improvement in computational methods. For example, the integration of state-of-the-art machine learning entities for fragment ion deconvolution, phosphosite localization, and quantitation correction will be critical for successful future DIA analyses, especially for the most convenient and straightforward direct DIA approach. Thirdly, despite the recent success and potential of the EV phosphoproteome analysis, consistent EV isolation strategy remains a universal problem for most laboratory and hospital benches. Evaluation parameters like recovery, purity, and reproducibility are critical to enabling routine EV phosphoproteome enrichment and analysis. Our team has recently developed a highly-efficient chemical affinity-based EV isolation technique, termed EV total recovery and purification (EVtrap), which aims to address these issues, but it still must be validated by groups worldwide to be universally recognized and accepted [108, 110]. Another concern in the field is the distinct biogenesis of biofluid EVs. Rather than using the bulk EV mixture, could the disease-specific EV populations be enriched and analyzed to focus only on the disease-related phosphorylation information and whether such an approach would offer an improved panel of specific biomarkers? However, the obstacles to such a strategy are similar to single cell phosphoproteomics analysis, with sensitivity and specificity issues potentially impeding effective analysis and subsequent adoption. In summary, the successful profiling of tissue or EV phosphoproteomics calls for additional substantial improvements in the field in order to enable truly clinically-useful phosphoproteomics analysis. With technical breakthroughs accumulating and knowledge gaps being filled, we expect that DIA-based EV phosphoproteome screening has the potential to redefine clinical liquid biopsy for personalized precision medicine.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Protein phosphorylation relates to most biological functions and disease onset and progression.

Mass spectrometry has been the method of the choice for cell-wide protein phosphorylation analysis.

MS allows confident identification and quantitation in phosphoproteome profiling.

Circulating extracellular vesicles contain and preserve disease-related phosphoprotein markers.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by NIH grants RF1AG064250, R43AG063589, and R44CA239845.

List of abbreviations and acronyms

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CAA

chloroacetamide

- CCS

collisional cross section

- DDA

data-dependent acquisition

- DIA

data-independent acquisition

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- EVtrap

EV total recovery and purification

- FFPE

formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded

- IAA

iodoacetamide

- IMAC

immobilized metal affinity chromatography

- iPSCs

induced pluripotent stem cells

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MAPK

p38/mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- pAKT

phosphorylated protein kinase B

- PASEF

Parallel Accumulation Serial Fragmentation

- pEGFR

phosphorylated epidermal growth factor receptor

- pmTOR

phosphorylated mechanistic target of rapamycin

- PolyMAC

polymer-based metal ion affinity capture

- PRM

parallel reaction monitoring

- pSTAT

phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- RPPA

reverse phase protein array

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SCBC

single-cell barcode chip

- SDC

sodium deoxycholate

- SLS

sodium lauroyl sarcosinate

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TMT

tandem mass tag

- timsTOF

trapped ion mobility spectrometry - quadrupole time of flight

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Ideker T, et al. , Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of a systematically perturbed metabolic network. Science, 2001. 292(5518): p. 929–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian Q, et al. , Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of gene expression in Mammalian cells. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2004. 3(10): p. 960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Studer RA, et al. , Evolution of protein phosphorylation across 18 fungal species. Science, 2016. 354(6309): p. 229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearlman SM, Serber Z, and Ferrell JE Jr., A mechanism for the evolution of phosphorylation sites. Cell, 2011. 147(4): p. 934–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrao P, et al. , Evolution and functional cross-talk of protein post-translational modifications. Mol Syst Biol, 2013. 9: p. 714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ardito F, et al. , The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (Review). Int J Mol Med, 2017. 40(2): p. 271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Garcia T, et al. , Role of Protein Phosphorylation in the Regulation of Cell Cycle and DNA-Related Processes in Bacteria. Front Microbiol, 2016. 7: p. 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardman G, et al. , Strong anion exchange-mediated phosphoproteomics reveals extensive human non-canonical phosphorylation. EMBO J, 2019. 38(21): p. e100847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salazar C and Hofer T, Multisite protein phosphorylation--from molecular mechanisms to kinetic models. FEBS J, 2009. 276(12): p. 3177–3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu ZL, Phosphatase-coupled universal kinase assay and kinetics for first-order-rate coupling reaction. PLoS One, 2011. 6(8): p. e23172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabbro D, Cowan-Jacob SW, and Moebitz H, Ten things you should know about protein kinases: IUPHAR Review 14. Br J Pharmacol, 2015. 172(11): p. 2675–2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulikas T, The phosphorylation connection to cancer (review). Int J Oncol, 1995. 6(1): p. 271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunez Lopez YO, et al. , Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Provide New Insights into Diabetes Pathobiology. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(10): p. 5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira J, et al. , Protein Phosphorylation is a Key Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017. 58(4): p. 953–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen P, Cross D, and Janne PA, Kinase drug discovery 20 years after imatinib: progress and future directions. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2021. 20(7): p. 551–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klaeger S, et al. , The target landscape of clinical kinase drugs. Science, 2017. 358(6367): p. eaan4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Attwood MM, et al. , Trends in kinase drug discovery: targets, indications and inhibitor design. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2021. 20(11): p. 839–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doll S, Gnad F, and Mann M, The Case for Proteomics and Phospho-Proteomics in Personalized Cancer Medicine. Proteomics Clin Appl, 2019. 13(2): p. e1800113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierobon M, et al. , Application of molecular technologies for phosphoproteomic analysis of clinical samples. Oncogene, 2015. 34(7): p. 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petricoin EF 3rd, et al. , Phosphoprotein pathway mapping: Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin activation is negatively associated with childhood rhabdomyosarcoma survival. Cancer Res, 2007. 67(7): p. 3431–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wulfkuhle JD, et al. , Molecular analysis of HER2 signaling in human breast cancer by functional protein pathway activation mapping. Clin Cancer Res, 2012. 18(23): p. 6426–6435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jameson GS, et al. , A pilot study utilizing multi-omic molecular profiling to find potential targets and select individualized treatments for patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2014. 147(3): p. 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irish JM, et al. , Single cell profiling of potentiated phospho-protein networks in cancer cells. Cell, 2004. 118(2): p. 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iliuk AB and Tao WA, Is phosphoproteomics ready for clinical research? Clin Chim Acta, 2013. 420: p. 23–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weston AD and Hood L, Systems biology, proteomics, and the future of health care: toward predictive, preventative, and personalized medicine. J Proteome Res, 2004. 3(2): p. 179–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hood L, Systems biology: integrating technology, biology, and computation. Mech Ageing Dev, 2003. 124(1): p. 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ombrone D, et al. , Expanded newborn screening by mass spectrometry: New tests, future perspectives. Mass Spectrom Rev, 2016. 35(1): p. 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.la Marca G, Mass spectrometry in clinical chemistry: the case of newborn screening. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2014. 101: p. 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma A, et al. , Comprehensive Workflow of Mass Spectrometry-based Shotgun Proteomics of Tissue Samples. J Vis Exp, 2021. (177): p. e61786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozanova S, et al. , Quantitative Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: An Overview. Methods Mol Biol, 2021. 2228: p. 85–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawton ML and Emili A, Mass Spectrometry-Based Phosphoproteomics and Systems Biology: Approaches to Study T Lymphocyte Activation and Exhaustion. J Mol Biol, 2021. 433(24): p. 167318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenqvist H, Ye J, and Jensen ON, Analytical strategies in mass spectrometry-based phosphoproteomics. Methods Mol Biol, 2011. 753: p. 183–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dang X, et al. , The first pilot project of the consortium for top-down proteomics: a status report. Proteomics, 2014. 14(10): p. 1130–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghezellou P, et al. , A perspective view of top-down proteomics in snake venom research. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom, 2019. 33(S1): p. 20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ono M, et al. , Label-free quantitative proteomics using large peptide data sets generated by nanoflow liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2006. 5(7): p. 1338–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natsume T, et al. , A direct nanoflow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry system for interaction proteomics. Anal Chem, 2002. 74(18): p. 4725–4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao H, et al. , Accelerated Lysis and Proteolytic Digestion of Biopsy-Level Fresh-Frozen and FFPE Tissue Samples Using Pressure Cycling Technology. J Proteome Res, 2020. 19(5): p. 1982–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hewitt SM, et al. , Tissue handling and specimen preparation in surgical pathology: issues concerning the recovery of nucleic acids from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2008. 132(12): p. 1929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scandella V, Paolicelli RC, and Knobloch M, A novel protocol to detect green fluorescent protein in unfixed, snap-frozen tissue. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 14642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vassilakopoulou M, et al. , Preanalytical variables and phosphoepitope expression in FFPE tissue: quantitative epitope assessment after variable cold ischemic time. Lab Invest, 2015. 95(3): p. 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller T and Winter D, Systematic Evaluation of Protein Reduction and Alkylation Reveals Massive Unspecific Side Effects by Iodine-containing Reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2017. 16(7): p. 1173–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman JK, et al. , Updates of the In-Gel Digestion Method for Protein Analysis by Mass Spectrometry. Proteomics, 2018. 18(23): p. e1800236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thingholm TE and Larsen MR, Phosphopeptide Enrichment by Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography. Methods Mol Biol, 2016. 1355: p. 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thingholm TE and Jensen ON, Enrichment and characterization of phosphopeptides by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) and mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol, 2009. 527: p. 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iliuk AB, et al. , In-depth analyses of kinase-dependent tyrosine phosphoproteomes based on metal ion-functionalized soluble nanopolymers. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2010. 9(10): p. 2162–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iliuk A, et al. , In-Depth Analyses of B Cell Signaling Through Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Phosphopeptides Enriched by PolyMAC. Int J Mass Spectrom, 2015. 377: p. 744–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iliuk A, et al. , Functionalized soluble nanopolymers for phosphoproteome analysis. Methods Mol Biol, 2011. 790: p. 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer JG, Qualitative and Quantitative Shotgun Proteomics Data Analysis from Data-Dependent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol, 2021. 2259: p. 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su T, et al. , A comparative study of data-dependent acquisition and data-independent acquisition in proteomics analysis of clinical lung cancer tissues constrained by blood contamination. Proteomics Clin Appl, 2021. 16(3): p. e2000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer JG and Schilling B, Clinical applications of quantitative proteomics using targeted and untargeted data-independent acquisition techniques. Expert Rev Proteomics, 2017. 14(5): p. 419–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borras E and Sabido E, What is targeted proteomics? A concise revision of targeted acquisition and targeted data analysis in mass spectrometry. Proteomics, 2017. 17(17-18): p. 1700180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Searle BC, et al. , Using Data Independent Acquisition (DIA) to Model High-responding Peptides for Targeted Proteomics Experiments. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2015. 14(9): p. 2331–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu A, Noble WS, and Wolf-Yadlin A, Technical advances in proteomics: new developments in data-independent acquisition. F1000Res, 2016. 5(F1000 Faculty Rev): p. 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barkovits K, et al. , Reproducibility, Specificity and Accuracy of Relative Quantification Using Spectral Library-based Data-independent Acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2020. 19(1): p. 181–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bekker-Jensen DB, et al. , Rapid and site-specific deep phosphoproteome profiling by data-independent acquisition without the need for spectral libraries. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitata RB, et al. , A data-independent acquisition-based global phosphoproteomics system enables deep profiling. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akkurt Arslan M, et al. , Proteomic Analysis of Tears and Conjunctival Cells Collected with Schirmer Strips Using timsTOF Pro: Preanalytical Considerations. Metabolites, 2021. 12(1): p. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aballo TJ, et al. , Ultrafast and Reproducible Proteomics from Small Amounts of Heart Tissue Enabled by Azo and timsTOF Pro. J Proteome Res, 2021. 20(8): p. 4203–4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meier F, et al. , Online Parallel Accumulation-Serial Fragmentation (PASEF) with a Novel Trapped Ion Mobility: Mass Spectrometer. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2018. 17(12): p. 2534–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu F, et al. , Fast Quantitative Analysis of timsTOF PASEF Data with MSFragger and IonQuant. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2020. 19(9): p. 1575–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foginov DS, et al. , Benefits of Ion Mobility: Separation and Parallel Accumulation-Serial Fragmentation Technology on timsTOF Pro for the Needs of Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Protein Analysis. ACS Omega, 2021. 6(15): p. 10352–10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skowronek P, et al. , Rapid and in-depth coverage of the (phospho-)proteome with deep libraries and optimal window design for dia-PASEF. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2022. 21(9): p. 100279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oliinyk D and Meier F, Ion mobility:-resolved phosphoproteomics with dia-PASEF and short gradients. Proteomics, 2022: p. e2200032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Migus A, et al. , COVID-19 epidemic phases: Criteria, challenges and issues for the future. Bull Acad Natl Med, 2020. 204(9): p. e145–e156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hageman JR, Current Status of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Influenza and COVID-19 Together, and COVID-19 Viral Variants. Pediatr Ann, 2020. 49(11): p. e448–e449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H, et al. , Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): current status and future perspectives. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2020. 55(5): p. 105951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiang HW, et al. , SARS-CoV-2 proteome microarray for global profiling of COVID-19 specific IgG and IgM responses. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meyerowitz-Katz G and Merone L, A systematic review and meta-analysis of published research data on COVID-19 infection fatality rates. Int J Infect Dis, 2020. 101: p. 138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bouhaddou M, et al. , The Global Phosphorylation Landscape of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell, 2020. 182(3): p. 685–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodriguez J, et al. , When Tissue is an Issue the Liquid Biopsy is Nonissue: A Review. Oncol Ther, 2021. 9(1): p. 89–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Esagian SM, et al. , Comparison of liquid-based to tissue-based biopsy analysis by targeted next generation sequencing in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2020. 146(8): p. 2051–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bai B, et al. , Proteomic landscape of Alzheimer’s Disease: novel insights into pathogenesis and biomarker discovery. Mol Neurodegener, 2021. 16(1): p. 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bai B, et al. , Deep Multilayer Brain Proteomics Identifies Molecular Networks in Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Neuron, 2020. 105(6): p. 975–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ping L, et al. , Global quantitative analysis of the human brain proteome and phosphoproteome in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Data, 2020. 7(1): p. 315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wesseling H, et al. , Tau PTM Profiles Identify Patient Heterogeneity and Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell, 2020. 183(6): p. 1699–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vaikath NN, et al. , Heterogeneity in alpha-synuclein subtypes and their expression in cortical brain tissue lysates from Lewy body diseases and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 2019. 45(6): p. 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Y, et al. , Purification and Characterization of Progenitor and Mature Human Astrocytes Reveals Transcriptional and Functional Differences with Mouse. Neuron, 2016. 89(1): p. 37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perkel JM, Single-cell proteomics takes centre stage. Nature, 2021. 597(7877): p. 580–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vistain LF and Tay S, Single-Cell Proteomics. Trends Biochem Sci, 2021. 46(8): p. 661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheung TK, et al. , Defining the carrier proteome limit for single-cell proteomics. Nat Methods, 2021. 18(1): p. 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paul I, et al. , Imaging the future: the emerging era of single-cell spatial proteomics. FEBS J, 2021. 288(24): p. 6990–7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ma C, et al. , A clinical microchip for evaluation of single immune cells reveals high functional heterogeneity in phenotypically similar T cells. Nat Med, 2011. 17(6): p. 738–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shi Q, et al. , Single-cell proteomic chip for profiling intracellular signaling pathways in single tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(2): p. 419–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wei W, et al. , Single-Cell Phosphoproteomics Resolves Adaptive Signaling Dynamics and Informs Targeted Combination Therapy in Glioblastoma. Cancer Cell, 2016. 29(4): p. 563–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parker BL, et al. , Targeted phosphoproteomics of insulin signaling using data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. Sci Signal, 2015. 8(380): p. rs6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Caron L, et al. , A Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Model of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy-Affected Skeletal Muscles. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2016. 5(9): p. 1145–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haider N, et al. , Signaling defects associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic and diabetic individuals and modification by sex. J Clin Invest, 2021. 131(21): p. e151818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yap TA, et al. , First-in-man clinical trial of the oral pan-AKT inhibitor MK-2206 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol, 2011. 29(35): p. 4688–4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baselga J, et al. , Phase I safety, pharmacokinetics, and inhibition of SRC activity study of saracatinib in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 2010. 16(19): p. 4876–4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giorgianni F and Beranova-Giorgianni S, Phosphoproteome Discovery in Human Biological Fluids. Proteomes, 2016. 4(4): p. 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jaros JA, et al. , Clinical use of phosphorylated proteins in blood serum analysed by immobilised metal ion affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. J Proteomics, 2012. 76: p. 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tagliabracci VS, Pinna LA, and Dixon JE, Secreted protein kinases. Trends Biochem Sci, 2013. 38(3): p. 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yalak G and Vogel V, Extracellular phosphorylation and phosphorylated proteins: not just curiosities but physiologically important. Sci Signal, 2012. 5(255): p. re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cocucci E and Meldolesi J, Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol, 2015. 25(6): p. 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu R, Simpson RJ, and Greening DW, A Protocol for Isolation and Proteomic Characterization of Distinct Extracellular Vesicle Subtypes by Sequential Centrifugal Ultrafiltration. Methods Mol Biol, 2017. 1545: p. 91–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bazie WW, et al. , Plasma Extracellular Vesicle Subtypes May be Useful as Potential Biomarkers of Immune Activation in People With HIV. Pathog Immun, 2021. 6(1): p. 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Raposo G and Stoorvogel W, Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol, 2013. 200(4): p. 373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tkach M and Thery C, Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell, 2016. 164(6): p. 1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Robbins PD and Morelli AE, Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol, 2014. 14(3): p. 195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen IH, et al. , Phosphoproteins in extracellular vesicles as candidate markers for breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(12): p. 3175–3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang Y, Wu X, and Andy Tao W, Characterization and Applications of Extracellular Vesicle Proteome with Post-Translational Modifications. Trends Analyt Chem, 2018. 107: p. 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peri S, et al. , Defining the genomic signature of the parous breast. BMC Med Genomics, 2012. 5: p. 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gong Y, et al. , Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 5 reduces bone mass by suppression of canonical Wnt signaling. Cell Death Dis, 2014. 5: p. e1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nam S, et al. , A pathway-based approach for identifying biomarkers of tumor progression to trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. Cancer Lett, 2015. 356(2B): p. 880–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yi T, et al. , Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis reveals system-wide signaling pathways downstream of SDF-1/CXCR4 in breast cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(21): p. E2182–E2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Minic Z, et al. , Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Breast Cancer-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Reveals Disease-Specific Phosphorvlated Enzymes. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(2): p. 408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Qiao Z, et al. , Phosphoproteomics of extracellular vesicles integrated with multiomics analysis reveals novel kinase networks for lung cancer. Mol Carcinog, 2022. 61(12): p. 1116–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu X, et al. , Highly Efficient Phosphoproteome Capture and Analysis from Urinary Extracellular Vesicles. J Proteome Res, 2018. 17(9): p. 3308–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hadisurya M, et al. , Quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics of urinary extracellular vesicles define diagnostic and prognostic biosignatures for Parkinson’s Disease. medRxiv, 2022.01.18.22269096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Iliuk A, et al. , Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicle Phosphoproteomics through Chemical Affinity Purification. J Proteome Res, 2020. 19(7): p. 2563–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]