Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to investigate whether dietary patterns were associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or pre-diabetes in adults of rural area in Henan.

Design:

Cross-sectional study. Principal component analysis was used to identify dietary patterns, while multivariate logistic regression analysis and restricted cubic spline regression models were used to analyse the association between dietary patterns and both pre-diabetes and T2DM.

Setting:

Rural area of Henan province, China.

Participants:

A total of 38 779 adults aged 18–79 years were recruited from the Henan rural cohort study as the subjects.

Results:

The prevalence of pre-diabetes and T2DM in rural Henan was 6·8 % and 9·4 %, respectively. A total of three dietary patterns were assessed in the present study. Dietary pattern I with a high intake of red meat and white meat; dietary pattern II with a high intake of grains, nuts, milk and eggs and dietary pattern III with a high intake of vegetables, staple food and fruits. The highest quintile (Q5) of pattern III could reduce 32·7 % risk of pre-diabetes. The Q5 of pattern II showed a 15·5 % decreased risk of T2DM, in a U-shaped dose–response manner; meanwhile, the Q5 of pattern III was significantly associated with reduced risks of T2DM (OR: 0·582, 95 % CI (0·497, 0·682)).

Conclusions:

Pattern III is beneficial for reducing risk of pre-diabetes or T2DM. Though a higher consumption of ‘grains-nuts-egg’ may associate with a reduced risk of T2DM, excessive intakes should be avoided. This study may provide a reference for the prevention of diabetes on dietary precautions.

Keywords: Dietary patterns, T2DM, Pre-diabetes, Rural adults

Over recent decades, the worldwide prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in adults has increased drastically, especially in developing countries(1–4). It has been estimated that 693 million or more people might suffer from diabetes worldwide by 2045, while 374 million people would become impaired glucose tolerance patients(5). The prevalence of diabetes in China has more than quadrupled in past decades; an estimated 110 million adults have suffered from diabetes in 2010, and 490 million adults were diagnosed as pre-diabetes(6). Moreover, the prevalence of diabetes in Chinese rural areas was 4·1 %(7), sugesting that diabetes issues in rural China cannot be ignored.

Genetic variations play an important role in the development of the disease, while epidemic data indicate that lifestyle changes, as well as environmental exposures, contribute to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)(8). It is well known that diet is one of the main affecting factors of a variety of diseases(9). Recent studies have shown that with the onset of diabetes, food choice and eating habits played a crucial role in controlling disease progression(10).

There are many studies that assessed the relationship of dietary patterns and diabetes in China; however, there is a gap and controversies in this area(11–14). The research of Cai et al. showed that the ‘meats’ and ‘grains’ dietary patterns were associated with an increased risk of T2DM, whereas the ‘dairy product’ dietary pattern showed no association with the risk of T2DM(11). The study of Shu et al. indicated that western dietary pattern was associated with an elevated risk, whereas the grains–vegetables dietary pattern was associated with a reduced risk of T2DM(13).

In traditional epidemiology, the main approach is to establish the relationship between nutrients or food with chronic diseases, such the case of diabetes. However, human diet is a complicated issue, as food consumed in China is varied and there are synergistic or inhibitory effects among nutrients, making it difficult to verify these possible associations. Nevertheless, the use of dietary patterns may overcome these limitations via analysing the effects of multiple dietary factors on the individual’s health(9,15). Many diabetes-related studies have found that early lifestyle modifications, particularly healthy diets and exercises, were effective in delaying the onset of diabetes(16).

Thus, it is important to know the eating patterns of diabetic individuals and their association with clinical aspects of the disease. In rural China, no studies have yet analysed the dietary patterns in both T2DM and pre-diabetes, nor their relationship with glycaemic control. In this study, we aimed to identify the main dietary patterns of patients with T2DM or pre-diabetes.

Methods

Study population

Data from the baseline survey of the Henan Rural Cohort were used to analyse the association between dietary patterns and T2DM. The Henan Rural Cohort was an ongoing cohort including 39 259 individuals aged 18–79 years in five rural regions of Henan province in China (Suiping county, Yuzhou county, Xinxiang county, Tongxu county and Yima county) at baseline (2015–2017). The cohort detail information is described elsewhere(17). For the present analysis, we excluded participants with type 1 diabetes (n 4), gestational diabetes (n 64), malignant tumours (n 332) and kidney failure (n 18). We additionally excluded participants with missing information on fasting glucose (n 63). This resulted in a final sample size of 38 779 participants for analyses. And, all participants completed the informed consent.

Data collection

Data were collected from a standard questionnaire including information on general demographic characteristics, lifestyles, personal and family history of diseases that was completed by well-trained investigators by face-to-face interview. Venous blood samples were collected for routine blood measurements, biochemical indexes after at least 8 h of overnight fasting. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), TAG, total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol were assayed by an automatic chemistry analyzer (Cobas C501, Roche Diagnostics GmbH). Glycosylated HbA1C was determined enzymatically on an automatic analyser. Insulin was measured using RIA. Anthropometric measurements included height, weight, waist circumference, resting blood pressure, heart rate and lung function. Subjects were in light clothing and without shoes when measuring anthropometric variables. Two measurements of height and weight were performed to the nearest 0·1 cm and 0·1 kg separately, on the basis of a standard protocol. Blood pressure measurements were performed after 5-min rest in seated position, with 30-s intervals between measurements, using an electronic sphygmomanometer (HEM-770AFuzzy). The average of the three measurements from the right arm of every person was applied to the analyses. All the measurements and tests were collected using standard protocol by trained staff. The detailed data collection protocol has been described elsewhere(18,19). BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height.

Dietary assessment

Dietary data were collected via a self-reported FFQ, which was evaluated for reliability and validity(20). A food consumption questionnaire contains eleven-item food groups including staple food such as rice, noodles and steamed bread; red meat such as pork, lamb and beef; white meat such as chicken and duck; fish including freshwater and marine fish; eggs such as chicken, duck and goose eggs; milk and dairy products including milk, goat’s milk, yogurt, cheese and other dairy products; fruits; vegetables; legumes and products like soya beans, mung beans, red beans, black beans, broad beans, tofu, soya milk, dried tofu, vegetarian chicken, etc.; nuts and peanuts; grains like corn, sweet potatoes and sorghum. Consumption questions covering intake of food groups during the previous 12 months were asked by a trained investigator. Each item had a choice of five frequency categories (never, daily, weekly, monthly, yearly) and the amount (g/ml) of food consumed at that frequency. For each question, the respondents were shown a card with samples of a standard portion of each food group relevant for typical diets.

Definition of type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes

The definition of T2DM and pre-diabetes was based on the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria (2018)(21). After excluding type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes and other special type of diabetes at the same time, pre-diabetes was defined as 5·6 mmol/l ⩽ FPG < 7·0 mmol/l, or 5·7 % < HbA1C < 6·5 %. T2DM was confirmed as FPG ⩾ p;7·0 mmol/l, or HbA1C > 6·5 %, or having a self-reported previous diagnosis of diabetes by a physician, or taking antiglycaemic agents during the previous 2 weeks.

Data analysis

Age was used on a continuous scale. Education was grouped into five categories (Illiteracy, Primary school, Middle school, High school, College and above) by asking the question ‘What is your highest level of education?’ Marital status was categorised as married, widowed, divorced and single. Smoking and drinking status were allocated to three categories as ‘never, ever, current’. Per capita monthly income was calculated by total household income and family size and categorised into five groups and expressed in Ren Min Bi (RMB: <500 RMB, 500–999 RMB, 1000–1999 RMB, 2000–2999 RMB, ≥3000 RMB. Physical activity level was estimated based on self-reported activities and grouped into three categories (low, medium and high).

Dietary patterns were identified by factor analysis using the standard principal component analysis method. The varimax method was used for rotation in the analysis. Patterns were determined by scree plot, eigenvalue (>1) and factor interpretability by each factor. Labelling of the patterns was primarily descriptive and based on our interpretation of the pattern structures. Factor loadings are equivalent to simple correlations between the food items and the patterns. Factor loadings were presented in tabular form. Participants were assigned pattern-specific factor scores, which were calculated as the sum of the products of the factor loading coefficients and standardised daily intake of each food group is associated with that pattern.

Continuous data are presented as mean and SD or median and quartile (median (p25, p75)). Categorical data are presented as number and percentage. The categorical data of each group were compared by χ2 test. The Kruskal–Wallis method was used to assess the differences in non-normally continuous data. Normally continuous data using one-way ANOVA assessed the P value. The circus diagram and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient were used to show the relationship between dietary patterns and variables. The association between diabetes/pre-diabetes and dietary patterns scores by using Multinomial logistic regression analysis and was adjusted for age, region, gender, education level, marital status and per capita monthly income in ‘Model 1’. Health behaviours (BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity and family history of diabetes) were further adjusted in ‘Model 2’. ‘Model 3’ was the final adjusted model by additional energy. For the quintiles of each dietary pattern, the first quintile (Q1) was considered as the reference group. Restricted cubic spline(22) was used to explore the dose–response relationship between continuous factor scores with T2DM and pre-diabetes, with five knots located at 17th, 33rd, 50th, 67th and 83rd percentiles of factor scores. All the analyses were conducted using SPSS21.0 (IBM Corp.) and R software (version 3.5.3). Statistical significance was considered when P < 0·05 with two-sided tested.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

A total of 38 779 remaining participants (15 368 males and 23 411 females) were included in the final analysis, and the mean age was 55·58 years. Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the participants according to case and control groups. The prevalence of pre-diabetes and T2DM was 6·8 % and 9·4 %, respectively. Statistically significant differences in gender, age, education level, marital status, region, per capita monthly income, physical activity, family history of diabetes, smoking and alcohol drinking were observed among different groups (P < 0·05). Furthermore, height, weight, BMI, waist circumference, as well as expressions of total cholesterol, TAG, insulin, fasting glucose and HDL-cholesterol also differed significantly among different groups (Table 2). Table 3 displays the differences in food consumptions among three groups. According to our study, participants with T2DM were more likely to consume less red meat, white meat, eggs and fruits. Furthermore, participants with pre-diabetes tended to consume fewer staples, red meat, fish, milk, vegetables and nuts in daily life.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics according to the grouping

| Control | Pre-diabetes | T2DM | χ2/F | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Total† | 32 491 | 83·8 | 2634 | 6·8 | 3654 | 9·4 | ||

| Gender | 8·356 | 0·015 | ||||||

| Men | 12 869 | 39·6 | 1102 | 41·8 | 1397 | 38·2 | ||

| Women | 19 622 | 60·4 | 1532 | 58·2 | 2257 | 61·8 | ||

| Age (years) | 446·726 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Mean | 54·78 | 58·66 | 60·39 | |||||

| sd | 12·45 | 10·53 | 9·24 | |||||

| Education level | 303·020 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Illiteracy | 5067 | 15·6 | 530 | 20·1 | 857 | 23·5 | ||

| Primary school | 8964 | 27·6 | 770 | 29·2 | 1163 | 31·8 | ||

| Middle school | 13 297 | 40·9 | 944 | 35·8 | 1205 | 33·0 | ||

| High school | 4112 | 12·7 | 354 | 13·4 | 373 | 10·2 | ||

| College and above | 1051 | 3·2 | 36 | 1·4 | 56 | 1·5 | ||

| Marry | 89·879 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Married | 29 245 | 90·0 | 2322 | 88·2 | 3236 | 88·8 | ||

| Widowed | 2501 | 7·7 | 282 | 10·7 | 378 | 10·3 | ||

| Divorced | 185 | 0·6 | 8 | 0·3 | 16 | 0·4 | ||

| Single | 560 | 1·7 | 22 | 0·8 | 24 | 0·7 | ||

| Region | 669·134 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Yuzhou | 7476 | 23·0 | 646 | 24·5 | 1056 | 28·9 | ||

| Zhumadian | 14 119 | 43·5 | 696 | 24·5 | 1028 | 28·1 | ||

| Kaifeng | 2017 | 6·2 | 72 | 6·5 | 285 | 7·8 | ||

| Xinxiang | 8095 | 24·9 | 1066 | 40·5 | 1186 | 32·5 | ||

| Yima | 784 | 2·4 | 54 | 2·1 | 99 | 2·7 | ||

| Income | 46·827 | <0·001 | ||||||

| ≤500 RMB | 11 366 | 35·0 | 1007 | 38·2 | 1437 | 39·3 | ||

| ∼1000 RMB | 10 739 | 33·1 | 859 | 32·6 | 1177 | 32·2 | ||

| ∼2000 RMB | 7893 | 24·3 | 600 | 22·8 | 815 | 22·3 | ||

| ∼3000 RMB | 1632 | 5·0 | 108 | 4·1 | 157 | 4·3 | ||

| ≥3000 RMB | 861 | 2·6 | 60 | 2·3 | 68 | 1·9 | ||

| Smoking | 93·120 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Never | 23 558 | 72·5 | 1879 | 71·3 | 2751 | 75·3 | ||

| Ever | 2491 | 7·7 | 277 | 10·5 | 365 | 10·0 | ||

| Current | 6442 | 19·8 | 478 | 18·1 | 538 | 14·7 | ||

| Drinking | 56·875 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Never | 25 098 | 77·2 | 1969 | 74·8 | 2882 | 78·9 | ||

| Ever | 1429 | 4·4 | 137 | 5·2 | 228 | 6·2 | ||

| Current | 5964 | 18·4 | 528 | 20·0 | 544 | 14·9 | ||

| Physical activity | 131·488 | <0·001 | ||||||

| Low | 10 134 | 31·2 | 970 | 36·8 | 1435 | 39·3 | ||

| Moderate | 12 425 | 38·2 | 901 | 34·2 | 1295 | 35·4 | ||

| High | 9932 | 30·6 | 763 | 29·0 | 924 | 25·3 | ||

| Family history of diabetes | 350·549 | <0·001 | ||||||

| No | 31 362 | 96·5 | 2512 | 95·4 | 3289 | 90·0 | ||

| Yes | 1129 | 3·5 | 122 | 4·6 | 365 | 10·0 | ||

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; RMB, Ren Min Bi.

Continuous data are presented as mean and sd using one-way ANOVA assessed the P value.

Categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages, and using χ2 test.

Table 2.

Levels of physical examination and biochemical traits of the participants in each group

| Variables | Control | Pre-diabetes | T2DM | χ2 | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | p25, p75 | Median | p25, p75 | Median | p25, p75 | |||

| Height (cm) | 159·20 | 154·00, 165·20 | 159·20 | 153·50, 165·50 | 158·10 | 153·00, 164·60 | 31·605 | <0·001 |

| Weight (kg) | 62·10 | 55·30, 69·70 | 65·50 | 58·80, 73·70 | 65·40 | 58·20, 73·40 | 513·135 | <0·001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24·44 | 22·18, 26·82 | 25·88 | 23·67, 28·26 | 25·99 | 23·76, 28·42 | 944·287 | <0·001 |

| WC (cm) | 83·00 | 76·00, 90·00 | 88·10 | 81·45, 95·00 | 89·00 | 83·00, 96·00 | 1507·573 | <0·001 |

| TC (mmol/l) | 4·60 | 4·03, 5·25 | 5·00 | 4·35, 5·70 | 4·91 | 4·28, 5·70 | 639·517 | <0·001 |

| TAG (mmol/l) | 1·34 | 0·96, 1·91 | 1·54 | 1·11, 2·32 | 1·73 | 1·20, 2·57 | 782·463 | <0·001 |

| Insulin (mg/ml) | 10·09 | 7·00, 13·12 | 10·90 | 7·40, 15·05 | 11·22 | 7·60, 15·39 | 260·263 | <0·001 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 5·10 | 4·77, 5·41 | 6·38 | 6·20, 6·60 | 8·04 | 7·19, 9·99 | 14 857·051 | <0·001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1·31 | 1·10, 1·54 | 1·24 | 1·05, 1·46 | 1·19 | 1·00, 1·43 | 440·117 | <0·001 |

WC, waist circumference; TC, total cholesterol.

P value was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis method.

Table 3.

Food consumption in each group

| Food groups | Control | Pre-diabetes | T2DM | χ2 | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | p25, p75 | Median | p25, p75 | Median | p25, p75 | |||

| Staple food (g/d) | 400·00 | 300·00, 500·00 | 400·00 | 300·00, 500·00 | 400·00 | 300·00, 500·00 | 46·580 | <0·001 |

| Red meat (g/d) | 16·67 | 6·67, 42·86 | 14·29 | 6·67, 35·71 | 14·29 | 5·00, 35·71 | 49·893 | <0·001 |

| White meat (g/d) | 6·67 | 1·67, 16·67 | 5·00 | 0·82, 14·29 | 5·00 | 0·82, 14·29 | 117·760 | <0·001 |

| Fish (g/d) | 1·37 | 0·00, 5·00 | 0·82 | 0·00, 3·33 | 0·96 | 0·00, 4·11 | 54·722 | <0·001 |

| Egg (g/d) | 62·50 | 17·86, 62·50 | 62·50 | 17·86, 62·50 | 62·50 | 17·86, 62·50 | 19·551 | 0·004 |

| Milk (ml/d) | 0·00 | 0·00, 16·67 | 0·00 | 0·00, 7·33 | 0·00 | 0·00, 17·56 | 21·038 | <0·001 |

| Fruits (g/d) | 100·00 | 33·33, 200·00 | 85·71 | 28·57, 200·00 | 57·14 | 13·33, 200·00 | 441·666 | <0·001 |

| Vegetable (g/d) | 250·00 | 200·00, 500·00 | 250·00 | 150·00, 400·00 | 250·00 | 200·00, 450·00 | 69·205 | <0·001 |

| Bean (g/d) | 16·67 | 5·00, 42·86 | 16·67 | 6·67, 42·86 | 16·67 | 6·67, 42·86 | 8·224 | 0·016 |

| Nuts (g/d) | 6·85 | 0·41, 21·43 | 6·85 | 0·00, 21·43 | 6·67 | 0·00, 16·67 | 13·979 | 0·001 |

| Grains (g/d) | 35·71 | 13·33, 83·33 | 50·00 | 14·29, 100·00 | 35·00 | 8·33, 100·00 | 35·633 | <0·001 |

P value was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis method.

Definition of dietary patterns

The three-cluster dietary patterns were obtained according to scree plot, eigenvalue (Fig. 1, see online Supplemental Fig. S1) and factor interpretability (see online Supplemental Table S1), with an accumulating contribution rate of 43·56 %. Factor 1, the ‘meat’ pattern, characterised by a high intake of red and white meat. Factor 2, the ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern, stands for a high intake of grains, nuts, milk and eggs. Factor 3, the ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern, is featured by a high consumption of vegetables, staple food and fruits.

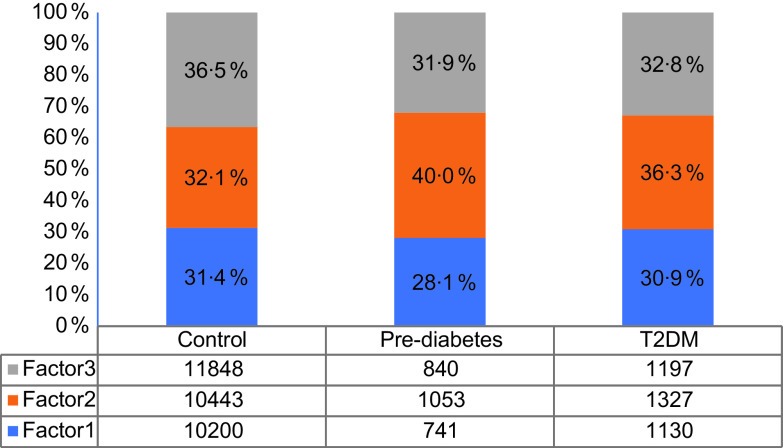

Fig. 1.

The proportion of dietary patterns components’ number of each group. Factor 1, ‘meat’ pattern; factor 2, ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern; factor 3, ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern. T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus

Figure 1 exhibits the proportion of dietary patterns components’ number of each group. The normal subjects conformed to ‘meat’ pattern, ‘grains-nuts-egg’ pattern and ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern were 31·6 %, 32·1 % and 36·5 %, respectively. Among people with pre-diabetes, the proportions of each pattern were 28·1 %, 40·0 % and 31·9 %. 30·9 % of T2DM patients were subjected to ‘meat’ pattern, 36·3 % with ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern and 32·8 % with ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern.

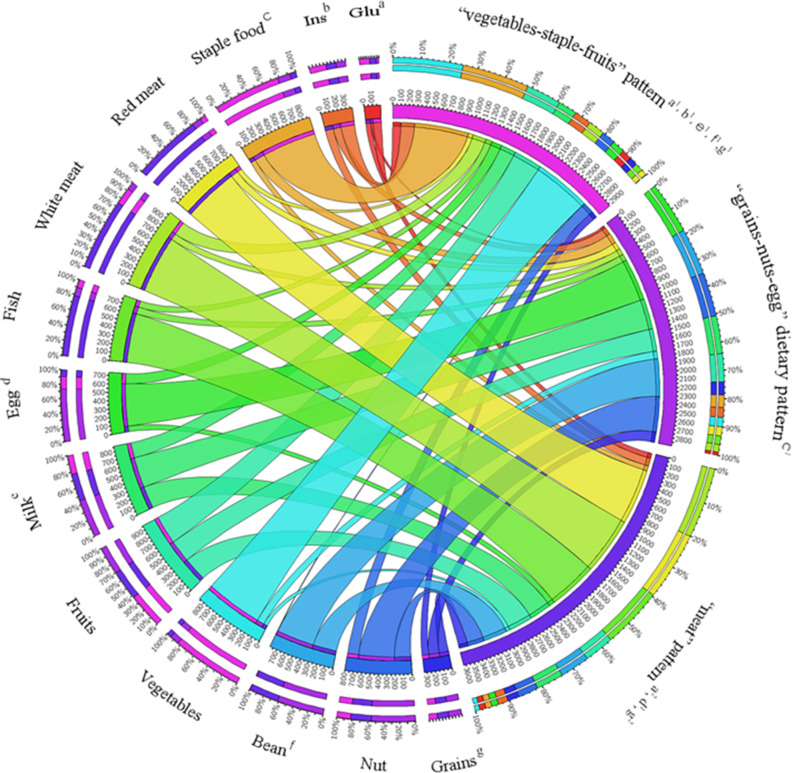

Figure 2 and Table S2 show the relationship among dietary patterns with insulin, fasting glucose and food groups. The width of the ribbon represents the intensity of the correlation (in positive correlation). The top three correlation coefficients for the ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern were vegetables, staple and fruits. Egg, milk, bean and nut were closely related to the ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern. For ‘meat’ pattern, red meat, white meat and fish were on the top of the menu. Furthermore, patients with ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern showed lower levels of fasting glucose and insulin, this pattern was negatively correlated with FPG (r = −0·106, P < 0·001) and positively correlated with insulin (r = 0·174, P < 0·001), while ‘meat’ pattern was also negatively related to the fasting glucose level.

Fig. 2.

The circus diagram of relationship between dietary patterns and variables. The correlation coefficient is negative between a and a1, a2, b and b1, c and c1, d and d1, e and e1, f and f1, g and g1, g2. The correlation coefficient was calculated by Spearman’s rank correlation. Ins, Insulin. Glu, fasting glucose

Table S3 presents the food consumption of each group based on the quintiles of different pattern factor scores. Under certain dietary patterns, the consumption of characteristic foods grows as the factor score increases. Take ‘meat’ pattern for example, the intake of fish, red and white meat advanced as the scores grew.

Relationship between dietary patterns and pre-diabetes

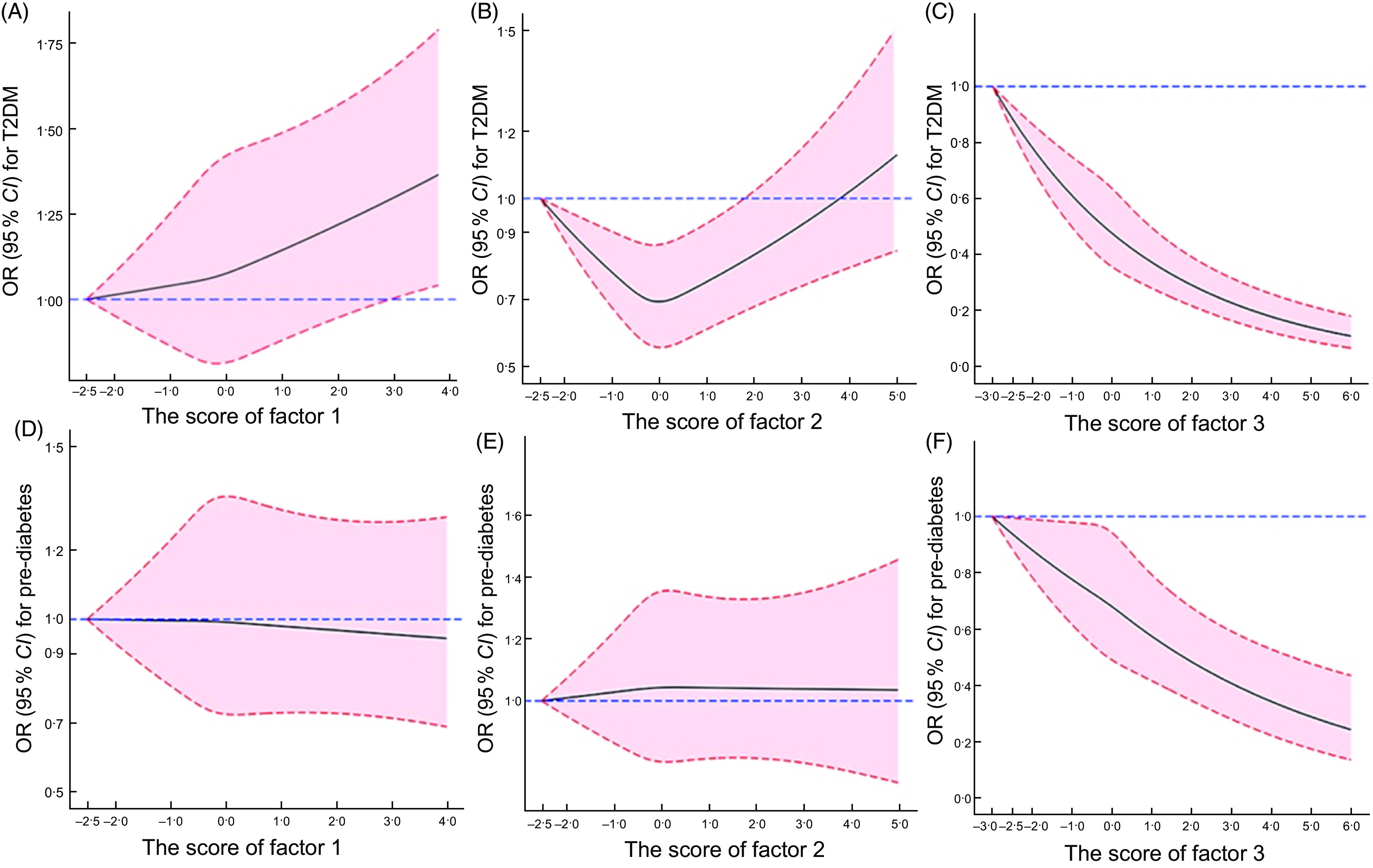

Table 4 and Fig. 3 show the associations between dietary patterns and pre-diabetes. In the crude model, the highest quintile (Q5) of the meat pattern was significantly associated with a reduced risk of pre-diabetes (OR: 0·678, 95 % CI (0·596, 0·771), Ptrend < 0·001) as compared with the lowest quintile (Q1). After adjusting for covariates (models 1–3), the ‘meat’ pattern was not significantly correlated with pre-diabetes. There was no significant correlation between ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern and pre-diabetes in both crude and adjusted models. In all models, the highest quintiles of ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern were significantly associated with reduced risks of pre-diabetes (OR crude: 0·616, 95 % CI (0·540, 0·703), Ptrend < 0·001); (OR model 1: 0·690, 95 % CI (0·602, 0·791), Ptrend < 0·001); (OR model: 2 0·708, 95 % CI (0·616, 0·813), Ptrend < 0·001); (OR model 3: 0·683, 95 % CI (0·569, 0·820), Ptrend < 0·001, respectively). There was a linear relationship for ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern in pre-diabetes according to the restrictive cubic spline.

Table 4.

OR (95 % CI) for pre-diabetes and T2DM according factor scores to by dietary pattern

| Groups | Dietary patterns | n | Crude* | Model 1† | Model 2‡ | Model 3§ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |||

| Pre-diabetes | Factor 1‖ | |||||||||

| Q1¶ | 599 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | |

| Q2 | 579 | 0·943 | 0·835, 1·065 | 1·061 | 0·938, 1·200 | 1·048 | 0·925, 1·187 | 1·047 | 0·924, 1·186 | |

| Q3 | 533 | 0·848 | 0·750, 0·959 | 1·029 | 0·908, 1·167 | 1·007 | 0·886, 1·144 | 1·005 | 0·884, 1·141 | |

| Q4 | 492 | 0·787 | 0·695, 0·892 | 1·025 | 0·901, 1·168 | 1·005 | 0·881, 1·146 | 0·999 | 0·875, 1·141 | |

| Q5 | 431 | 0·678 | 0·596, 0·771 | 0·971 | 0·845, 1·115 | 0·930 | 0·808, 1·070 | 0·919 | 0·794, 1·063 | |

| Ptrend | <0·001 | 0·796 | 0·384 | 0·820 | ||||||

| Factor 2 | ||||||||||

| Q1 | 484 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | |

| Q2 | 510 | 1·049 | 0·921, 1·194 | 0·977 | 0·857, 1·114 | 0·991 | 0·868, 1·131 | 0·991 | 0·869, 1·131 | |

| Q3 | 540 | 1·120 | 0·985, 1·274 | 0·993 | 0·871, 1·133 | 1·013 | 0·887, 1·157 | 1·011 | 0·885, 1·155 | |

| Q4 | 574 | 1·188 | 1·046, 1·349 | 1·017 | 0·891, 1·161 | 1·054 | 0·922, 1·205 | 1·048 | 0·916, 1·200 | |

| Q5 | 526 | 1·090 | 0·957, 1·242 | 0·896 | 0·780, 1·028 | 0·947 | 0·824, 1·089 | 0·936 | 0·809, 1·082 | |

| Ptrend | 0·043 | 0·078 | 0·411 | 0·885 | ||||||

| Factor 3 | ||||||||||

| Q1 | 604 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | |

| Q2 | 627 | 1·029 | 0·915, 1·157 | 1·073 | 0·953, 1·208 | 1·072 | 0·951, 1·209 | 1·061 | 0·937, 1·202 | |

| Q3 | 494 | 0·790 | 0·698, 0·895 | 0·859 | 0·757, 0·975 | 0·847 | 0·745, 0·963 | 0·833 | 0·725, 0·957 | |

| Q4 | 510 | 0·810 | 0·716, 0·917 | 0·893 | 0·787, 1·014 | 0·898 | 0·790, 1·022 | 0878 | 0·757, 1·019 | |

| Q5 | 399 | 0·616 | 0·540, 0·703 | 0·690 | 0·602, 0·791 | 0·708, | 0·616, 0·813 | 0·683 | 0·569, 0·820 | |

| Ptrend | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | ||||||

| T2DM | Factor 1** | |||||||||

| Q1 | 806 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | |

| Q2 | 824 | 0·965 | 0·868, 1·072 | 1·076 | 0·966, 1·197 | 1·053 | 0·943, 1·175 | 1·049 | 0·940, 1·171 | |

| Q3 | 720 | 0·841 | 0·755, 0·936 | 1·035 | 0·927, 1·156 | 1·004 | 0·896, 1·124 | 0·988 | 0·883, 1·107 | |

| Q4 | 681 | 0·805 | 0·722, 0·897 | 1·094 | 0·978, 1·225 | 1·079 | 0·962, 1·211 | 1·039 | 0·925, 1·167 | |

| Q5 | 623 | 0·720 | 0·645, 0·804 | 1·111 | 0·987, 1·251 | 1·094 | 0·968, 1·235 | 1·008 | 0·888, 1·144 | |

| Ptrend | <0·001 | 0·068 | 0·123 | 0·103 | ||||||

| Factor 2†† | ||||||||||

| Q1 | 795 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | |

| Q2 | 705 | 0·883 | 0·793, 0·984 | 0·848 | 0·761, 0·946 | 0·875 | 0·783, 0·978 | 0·877 | 0·781, 0·976 | |

| Q3 | 700 | 0·882, | 0·792, 0·983 | 0·837 | 0·749, 0·936 | 0·859 | 0·766, 0·962 | 0·843 | 0·752, 0·945 | |

| Q4 | 705 | 0·886 | 0·795, 0·987 | 0·835 | 0·745, 0·935 | 0·871 | 0·775, 0·977 | 0·835 | 0·743, 0·939 | |

| Q5 | 749 | 0·942 | 0·846, 1·049 | 0·872 | 0·778, 0·979 | 0·919 | 0·817, 1·034 | 0·845 | 0·747, 0·956 | |

| Ptrend | 0·343 | 0·009 | 0·117 | 0·125 | ||||||

| Factor 3‡‡ | ||||||||||

| Q1 | 862 | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | 1 | ref. | |

| Q2 | 810 | 0·920 | 0·830, 1·019 | 0·954 | 0·860, 1·059 | 0·966 | 0·868, 1·075 | 0·904 | 0·809,1·009 | |

| Q3 | 740 | 0·819 | 0·737, 0·909 | 0·870 | 0·781, 0·968 | 0·884 | 0·792, 0·987 | 0·794 | 0·704, 0·894 | |

| Q4 | 652 | 0·719 | 0·645, 0·801 | 0·772 | 0·690, 0·862 | 0·793 | 0·707, 0·889 | 0·682 | 0·598, 0·777 | |

| Q5 | 590 | 0·634 | 0·567, 0·708 | 0·698 | 0·622, 0·784 | 0·742 | 0·659, 0·835 | 0·582 | 0·497, 0·682 | |

| Ptrend | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | <0·001 | ||||||

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Crude: unadjusted.

Model 1: adjusted for age, region, gender, education level, marital status and per capita monthly income.

Model 2: further adjusted for BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity and family history of diabetes based on model 1.

Model 3: further adjusted for energy based on model 2.

Factor scores were divided into quartiles.

For the quintiles of each dietary pattern, the first quintile (Q1) was considered as the reference group.

Factor 1, ‘meat’ pattern.

Factor 2, ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern.

Factor 3, ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern.

Fig. 3.

Dose–response relationships between continuous factor score with T2DM and pre-diabetes. Fully adjusted model was adjusted for age, region, gender, education level, marital status, per capita monthly income, BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, family history of diabetes and energy. Factor 1, ‘meat’ pattern; factor 2, ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern; factor 3, ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern

The relationship between dietary patterns and type 2 diabetes mellitus

The OR of T2DM across quintiles of dietary patterns are shown in Table 4. Before adjustment (crude model), the highest quintile (Q5) of the ‘meat’ pattern was significantly associated with a reduced risk of T2DM (OR: 0·720, 95 % CI (0·645, 0·804), Ptrend < 0·001) when compared with the lowest quintile (Q1). After adjusting for covariates (models 1–3), the ‘meat’ pattern was not significantly correlated with T2DM. Nevertheless, the restrictive cubic spline suggested a risk trend between ‘meat’ pattern and T2DM after fully adjusted.

The highest quintile of the ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern was not significantly associated with a decreased risk of T2DM (OR: 0·942, 95 % CI (0·846, 1·049), Ptrend = 0·343); however, there was a significant association in the fully adjusted model (OR: 0·845, 95 % CI (0·747, 0·956), Ptrend = 0·125), and this dose–response relationship was shown to be U-shaped by restrictive cubic spline (Fig. 3 ).

The risk of T2DM decreased gradually as the intake of ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern increased. In both unadjusted and adjusted models, the highest quintiles of ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern were significantly associated with reduced risks of T2DM (OR unadjusted: 0·634, 95 % CI (0·567, 0·708), Ptrend < 0·001); (OR adjusted: 0·582, 95 % CI (0·497, 0·682), Ptrend < 0·001, respectively). A linear relationship between ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern and T2DM was shown by restrictive cubic spline (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our study suggested that ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern is beneficial for reducing risk of pre-diabetes or T2DM, which is consistent with the results of previous studies(23–26). Plant-based dietary patterns, which are rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains, play a pivotal role in preventing various chronic diseases. A research reported that non-vegetarians were 74 % more likely to develop diabetes than vegetarians over 17 years of follow-up (via a 17-year period-study)(27). Plant-based diet may help prevent and treat diabetes, possibly by improving insulin sensitivity and ameliorating insulin resistance(28). Reports show that fruits, vegetables and whole grains may improve glycaemic control and reduce carbohydrate production and the risk of diabetes due to their low energy density, low glycaemic load, high fibre and antioxidant content(25,29). Similarly, vegetarian and vegan diets have also been shown to improve plasma lipid concentrations and reverse atherosclerosis progression(24). What is more? Vegetarian diet seems to be more effective in controlling glycaemia and plasma lipid concentrations(30). In fact, the dietary pattern of high fruits and vegetables is indeed beneficial for the prevention of T2DM(31).

On the contrary, evidences have linked red meat intake to an increased risk of CAD, cancer and T2DM(32). which is in consistent with our results. After adjusting for covariates, the ‘meat’ pattern was not significantly correlated with pre-diabetes, whereas there was a risk trend between ‘meat’ pattern and T2DM. High consumption of meat, especially for red meat which contains high amounts of saturated fat and cholesterol, was associated with an increased risk of obesity, an important risk factor for T2DM(33). Meanwhile, higher intakes of red meat may result in more absorption of haem iron(34). Previous studies have also demonstrated that body iron overload may induce insulin resistance and increase the risk of T2DM(35). Worsely, advanced glycation of high-fat products and meats can enhance oxidative stress and inflammation, which in turn accelerates insulin resistance and increases the risk of T2DM(36).

The ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary pattern, characterised by high consumption of grains, nuts, egg, beans and milk, reduced the risk of T2DM. However, no such correlation was seen with pre-diabetes. A recent report by Song et al. has shown that higher consumption of dairy products(37,38) and nuts(39) was associated with a reduced risk of T2DM(40). In addition, a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies revealed an inverse correlation between dairy foods, particularly yogurt, with T2DM(37). Some investigators(41) stressed that whole-fat dairy could be detrimental, for that an inverse association between diary food and T2DM was seen most frequently in higher yogurt and low-fat milk intake rather than high-fat milk or other dairy products such as cheeses(37,42). Our study failed to establish a similar inverse correlation with pre-diabetes since our dairy food consumption category referred to all kinds of dairy foods.

The present study holds several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the relationship between dietary patterns and both risks of pre-diabetes and T2DM among the rural adults in China. Our findings provided valuable information for the primary prevention of T2DM, as well as pre-diabetes, through dietary modifications to the rural Chinese population. Second, this survey is a large-scaled cross-sectional study of its kind in rural China. Third, in our analyses, we have also adjusted for some known and proposed potential confounders in the statistical model. However, some potential limitations still warrant a mention. First, based on the cross-sectional design, we cannot evaluate the causal associations between dietary patterns and the risk of pre-diabetes and T2DM. However, the cross-sectional research reflects the individual exposure and outcome at the time of the investigation, which helps to indicate the risk factors of the disease. Second, the definition of T2DM based on FPG and HbA1C was flawed. Thus, additional diagnostic tests were needed in future research. Third, factor analysis, which was used for data reduction, has limitations. The definition of the dietary patterns, including determination on number of factors, the type of rotation, as well as the interpretation and naming of the factors, involves subjective decisions (may not be so objective)(31). We used rotation in the analysis to make the extracted factors more explanatory. Fourth, we had no further calculation of nutrients, since FFQ was collected according to food group. For further researches, we will evaluate the reliability and validity of the amounts of nutrients obtained through FFQ by calculating the nutrient weighting coefficients for each food group based on data from the 3-d 24 h-dietary review of a small sample. Fifth, Differences between the group with normal glucose metabolism and the group with diabetes may reflect changes in diet as a result of the diabetes diagnosis. We lack the investigation of newly diagnosed diabetes; nevertheless, we investigated the diet of patients with pre-diabetes, which provides a reference for the prevention of diabetes on dietary precautions.

Conclusions

The ‘vegetables-staple-fruits’ pattern is beneficial for reducing risk of pre-diabetes or T2DM. People with pre-diabetes should consume more fruits and vegetables instead of meat or eggs/milks. Although a higher consumption of ‘grains-nuts-egg’ dietary patterns may be associated with a reduced risk of T2DM, excessive intakes should be avoided. This study may provide a reference for the prevention of diabetes on dietary precautions.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the villagers who took part in this study, the research team and hospital staff for their cooperation and assistance. Financial support: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Programme Precision Medicine Initiative of China, grant number: 2016YFC0900803; National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers: 81872626 and 82003454; Chinese Nutrition Society – Bright Moon Seaweed Group Nutrition and Health Research Fund, grant number: CNS-BMSG2020A63; Chinese Nutrition Society – Zhendong National Physical Fitness and Health Research Fund, grant number: CNS-ZD2019066. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authorship: Conceptualisation, W.-J.L. and C.-J.W.; methodology, Y.X.; investigation, C.L., B.-Y.W., D.-D.Z. and Y.W.; data curation, Z.-X.M. and S.-C.Y.; writing-original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing-review & editing, X.L. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University. Ethic approval code: (2015) MEC (S128). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000227.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Shaw JE, Sicree RA & Zimmet PZ (2010) Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 87, 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C et al. (2011) IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 94, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y et al. (2017) IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 128, 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I et al. (2014) Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103, 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S et al. (2018) IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 138, 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu Y, Wang L, He J et al. (2013) Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA 310, 948–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bragg F, Holmes MV, Iona A et al. (2017) Association between diabetes and cause-specific mortality in rural and urban areas of China. JAMA 317, 280–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Studart EPM, Arruda SPM, Sampaio HAD et al. (2018) Dietary patterns and glycemic indexes in type 2 diabetes patients. Rev Nutr 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frank LK, Kroger J, Schulze MB et al. (2014) Dietary patterns in urban Ghana and risk of type 2 diabetes. Br J Nutr 112, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Colles SL, Singh S, Kohli C et al. (2013) Dietary beliefs and eating patterns influence metabolic health in type 2 diabetes: a clinic-based study in urban North India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 17, 1066–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cai JX, Zhang Y, Nuli R et al. (2019) Interaction between dietary patterns and TCF7L2 polymorphisms on type 2 diabetes mellitus among Uyghur adults in Xinjiang Province, China. Diabetes Metab Syndr 12, 239–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mak J, Pham N, Lee A et al. (2018) Dietary patterns during pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes: a prospective cohort study in Western China. Nutr J 17, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shu L, Shen XM, Li C et al. (2017) Dietary patterns are associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged adults in Zhejiang Province, China. Nutr J 16, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi ZM, Zhen SQ, Zimmet PZ et al. (2016) Association of impaired fasting glucose, diabetes and dietary patterns with mortality: a 10-year follow-up cohort in Eastern China. Acta Diabetologica 53, 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Castro MBT, Sichieri R, Brito FDB et al. (2014) Mixed dietary pattern is associated with a slower decline of body weight change during postpartum in a cohort of Brazilian women. Nutr Hosp 29, 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tuso P (2014) Prediabetes and lifestyle modification: time to prevent a preventable disease. Perm J 18, 88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu X, Mao Z, Li Y et al. (2019) The Henan rural cohort: a prospective study of chronic non-communicable diseases. Int J Epidemiol 78, 1756–1756j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu XT, Yu SC, Mao ZX et al. (2018) Dyslipidemia prevalence, awareness, treatment, control, and risk factors in Chinese rural population: the Henan rural cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 17, 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu RH, Li YQ, Mao ZX et al. (2018) Gender-specific independent and combined dose-response association of napping and night sleep duration with type 2 diabetes mellitus in rural Chinese adults: the rural diabetes study. Sleep Med 45, 106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xue Y, Yang K, Wang B et al. (2019) Reproducibility and validity of an FFQ in the Henan rural cohort study. Public Health Nutr 23, 34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Diabetes Association (2018) 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes – 2018. Diabetes Care 41, Suppl. 1, S13–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Desquilbet L & Mariotti F (2010) Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med 29, 1037–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medina-Remon A, Kirwan R, Lamuela-Raventos RM et al. (2018) Dietary patterns and the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, and neurodegenerative diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci 58, 262–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barnard ND, Katcher HI, Jenkins DJA et al. (2009) Vegetarian and vegan diets in type 2 diabetes management. Nutr Rev 67, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tonstad S, Stewart K, Oda K et al. (2013) Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc 23, 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Papamichou D, Panagiotakos DB & Itsiopoulos C (2019) Dietary patterns and management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 29, 531–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vang A, Singh PN, Lee JW et al. (2008) Meats, processed meats, obesity, weight gain and occurrence of diabetes among adults: findings from Adventist Health Studies. Ann Nutr Metab 52, 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McEvoy CT, Temple N & Woodside JV (2012) Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: a review. Public Health Nutr 15, 2287–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Psaltopoulou T, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C et al. (2011) Dietary antioxidant capacity is inversely associated with diabetes biomarkers: the ATTICA study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc 21, 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ et al. (2009) A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-weeks clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 89, 1588S–1596S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shu L, Shen XM, Li C et al. (2017) Dietary patterns are associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged adults in Zhejiang Province, China. Nutr J 16, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pounis GD, Tyrovolas S, Antonopoulou M et al. (2010) Long-term animal-protein consumption is associated with an increased prevalence of diabetes among the elderly: the Mediterranean islands (MEDIS) study. Diabetes Metab 36, 484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shu L, Zheng PF, Zhang XY et al. (2015) Association between dietary patterns and the indicators of obesity among Chinese: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients 7, 7995–8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maghsoudi Z, Ghiasvand R & Salehi-Abargouei A (2016) Empirically derived dietary patterns and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis on prospective observational studies. Public Health Nutr 19, 230–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang R, Ma J, Ascherio A et al. (2004) Dietary iron intake and blood donations in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in men: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 79, 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Palli D & Consortium I (2013) Association between dietary meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: the EPIC-InterAct study. Diabetologia 56, 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gijsbers L, Ding EL, Malik VS et al. (2016) Consumption of dairy foods and diabetes incidence: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr 103, 1111–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tong X, Dong JY, Wu ZW et al. (2011) Dairy consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 65, 1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Afshin A, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S et al. (2014) Consumption of nuts and legumes and risk of incident ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 100, 278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Song S & Lee JE (2018) Dietary patterns related to triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in Korean men and women. Nutrients 11, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abiemo EE, Alonso A, Nettleton JA et al. (2013) Relationships of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with insulin resistance and diabetes incidence in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Br J Nutr 109, 1490–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu S, Choi HK, Ford E et al. (2006) A prospective study of dairy intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 29, 1579–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000227.

click here to view supplementary material