Abstract

Objective:

To date, there have been few studies on dietary supplement (DS) use in Korean children and adolescents, using nationally representative data. This study aimed to investigate the current status of DS use and its related factors, among Korean children and adolescents from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) data.

Design:

A cross-sectional study.

Setting:

Data from the KNHANES 2015–2017. Participants completed 24-h dietary recall interviews, including DS products that the subjects consumed.

Participants:

The study population was 4380 children and adolescents aged 1–18 years.

Results:

Approximately 2013 % of children and adolescents were using DS; the highest use was among children aged 1–3 years old, and the lowest use was among adolescents aged 16–18 years. The most frequently used DS was prebiotics/probiotics, followed by multivitamin/mineral supplements. Factors that were associated with DS use were lower birth weight in children aged <4 years; younger age, higher household income, regular breakfast intake and lower BMI in children aged 4–9 years; and regular breakfast intake and use of nutrition facts label in adolescents aged 10–18 years. Feeding patterns in infancy and having chronic diseases were not associated with DS use.

Conclusions:

We report that over 20 % of children and adolescents use DS. Nutritional education for parents and children about proper DS consumption is needed.

Keywords: Dietary supplements, Children, Adolescent, Korea

A dietary supplement (DS) is defined as a vitamin, a mineral, an herb or other botanical, an amino acid, a nutritional substance intended for ingestion to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake, or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract or combination of any ingredient described(1). As socio-economic status improves, DS use becomes increasingly prevalent among children and adolescents in developed countries to compensate for nutritional deficits, improve health conditions and prevent diseases(2,3). For instance, nearly one-third of infants, children and adolescents use DS in the USA(4–6), mostly in the form of multivitamin–minerals(4–6). The use of DS was reported to be associated with higher income, higher household food security levels and higher household education levels in the USA(6).

While public interest in DS use among children has increased, studies on the prevalence and related factors in paediatric DS use are scarce, worldwide, except for in the US Research on DS use in the Korean paediatric population is also extremely limited and is mostly limited to specific regions and age groups(7). This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of each type of DS through all age groups and the related factors affecting the habits of DS use among Korean children and adolescents, using the most recent nationally representative data.

Methods

Subject

The data were collected from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between 2015 and 2017. The study population was confined to subjects aged 1–18 years, who completed a 24-h food recall questionnaire during the survey. The 24-h food recall questionnaire included the type and product name of the DS consumed by the subjects over the past 24 h, the amount of single use and the frequency of DS intake during the day. Participants without anthropometric measurements were excluded. After exclusion, a total of 4380 children and adolescents aged 1–18 years (1777 boys and 1665 girls) were enrolled in this study.

Data collection and study variables

The weight and height of the participants were measured using a digital weighing scale and a stadiometer to the nearest 0·1 kg and 0·1 cm, respectively. BMI was calculated by dividing body weight (kg) by the square root of height (m). For subjects aged ≥2 years, BMI status was grouped into three groups according to the sex and age-specific BMI percentile(8): normal (<85th percentile), overweight (≥85th percentile and <95th percentile) and obese (≥95th percentile). Height status was organised into three groups according to the sex and age-specific height percentile(8): short (<15th percentile), average (≥15th percentile and <85th percentile) and tall (≥85th percentile).

The household income group was categorised according to the quartile values of equalised household income. Birth weight (kg) and feeding patterns during infancy (breast-feeding, formula feeding and mixed feeding) were surveyed in subjects under 4 years of age. Birth weight was organised into three groups: <2·5 kg, 2·5–3·9 kg, ≥4·0 kg. Participants who had a history of atopic dermatitis, asthma and CHD were defined as having chronic diseases. There were no participants who reported other chronic diseases, such as cancer, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus and hepatitis.

Whether or not the subject typically used the nutrition facts label was surveyed only in participants over 10 years old. The frequency of weekly breakfast intakes was divided into three groups: 0–2, 3–4 and 5–7 times/week.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS, Inc.). Sampling weights were used to consider the complex, multistage, probability sampling design for all analyses. The Complex Samples General Linear Model was used to calculate the mean and se of the scale variables, and the Complex Samples Crosstab procedure was used for categorical or ordinal variables. The Complex Samples Logistic Regression procedure was used to identify demographic and dietary habits (OR and 95 % CI) associated with DS use. P-values were two-tailed for all analyses, and a P-value of <0·05 was considered significant.

Results

The prevalence of dietary supplements

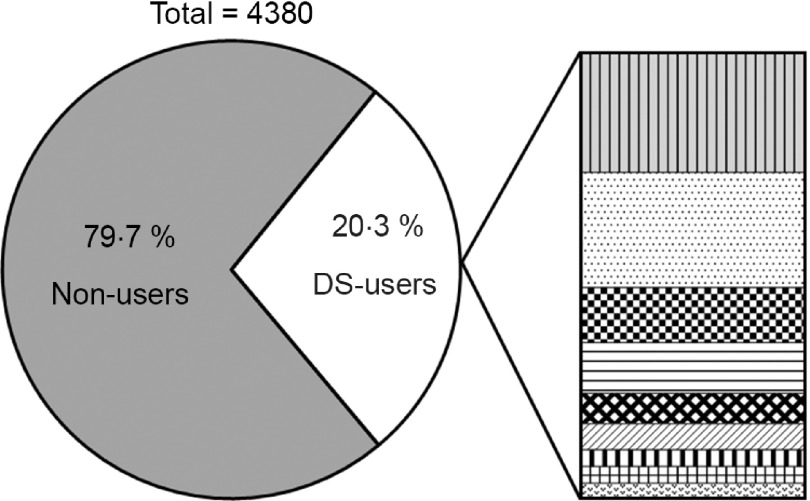

The overall prevalence and types of DS use in subjects are presented in Fig. 1. A total of 20·3 % of children and adolescents used DS. The most consumed DS was probiotics and prebiotics (26·9 % of all DS use), with similar proportions of multivitamin/mineral supplements consumed (25·9 %). Other DS, which included miscellaneous types of botanical supplements, Fe and propolis, accounted for 124 % of all DS types. As a single nutrient, vitamin C and n-3/fish oil accounted for 6·9 %, vitamin D for 5·9 %, Ca and Zn for 3·8 % and red ginseng extract for 3·1 %.

Fig. 1.

The prevalence and types of dietary supplement use among Korean children and adolescents.  , 26·9 % Pro/prebiotics;

, 26·9 % Pro/prebiotics;  , 25·9 % multivitamin/mineral supplements;

, 25·9 % multivitamin/mineral supplements;  , 12·4 % others (botanical supplements, iron etc.);

, 12·4 % others (botanical supplements, iron etc.);  , 11·4 % vitamin C;

, 11·4 % vitamin C;  , 6·9 % ω-3/fish oil;

, 6·9 % ω-3/fish oil;  , 5·9 % vitamin D;

, 5·9 % vitamin D;  , 3·8 % calcium;

, 3·8 % calcium;  , 3·8 % zinc;

, 3·8 % zinc;  , 3·1 % red ginseng

, 3·1 % red ginseng

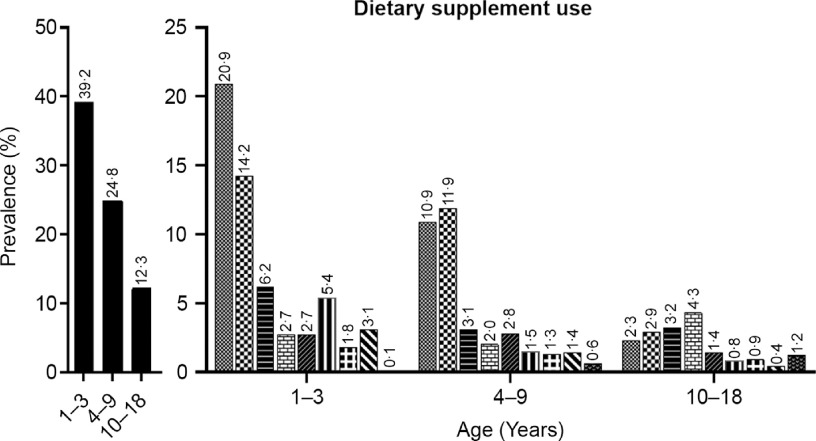

Types of dietary supplement by age group

The prevalence of DS use by age group and DS types is presented in Fig. 2. Total DS intake was 39·2 % at 1–3 years old, 24·8 % at 4–9 years old and 12·3 % at 10–18 years old. In the 1–3-year-old age group, the most commonly used DS was probiotics and prebiotics (20·9 %), followed by multivitamin/mineral supplements (14·2 %), and others (6·2 %). In the 4–9-year-old age group, multivitamin/mineral supplements (119 %) were used most frequently, followed by probiotics and prebiotics (10·9 %) and others (3·1 %). Whereas in the 10–18-year-old age group, the most commonly used DS was vitamin C (4·3 %), followed by others (3·2 %), and multivitamin/mineral supplements (2·9 %).

Fig. 2.

Types of dietary supplement use by age group.  , Any dietary supplements;

, Any dietary supplements;  , pro/prebiotics;

, pro/prebiotics;  , Multivitamin/mineral;

, Multivitamin/mineral;  , others including botanical supplements, Fe and propolis;

, others including botanical supplements, Fe and propolis;  , vitamin C;

, vitamin C;  , ω-3/fish oil;

, ω-3/fish oil;  , vitamin D;

, vitamin D;  , calcium;

, calcium;  , zinc;

, zinc;  , red ginseng

, red ginseng

General characteristics of the study participants

The general characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of DS users was statistically significantly younger than that of non-users and was 7·5 and 9·0 years old, respectively (P < 0·001). The proportion of participants who were under 6 years of age was higher in DS users (50·9 %), compared with non-users (26 %). There were no significant differences in the proportions of sex, household income, height status and chronic disease status according to DS use. A lower prevalence of obesity in DS users was noted, compared with non-users (5·6 % v. 11·2 %, P < 0·001). About three times higher proportion of low birth weight in subjects under 4 years of age was found in DS users than in non-users (9·0 % v. 3·1 %, P = 0·023). However, there were no significant differences in feeding patterns in infancy according to DS use. DS users were more likely to use nutrition facts labels (29·8 % v. 20·6 %, P = 0·035) and more likely to eat breakfast at least five times a week, compared with non-users (84·5 % v. 69·6 %, P < 0001).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population

| Non-users (n 3442) | DS users (n 938) | Total (n 4380) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | P-value | |

| Age (years) | <0·001 | ||||||

| Mean | 10·6 | 7·5 | 9·0 | ||||

| se | 0·2 | 0·3 | 0·2 | ||||

| Age (years) | <0·001 | ||||||

| 1–3 | 498 | 112 | 314 | 283 | 812 | 147 | |

| 4–9 | 1330 | 303 | 401 | 393 | 1731 | 321 | |

| 10–18 | 1614 | 585 | 223 | 324 | 1837 | 532 | |

| Household income | 0·19 | ||||||

| Quartile 1 | 283 | 93 | 51 | 62 | 334 | 87 | |

| Quartile 2 | 980 | 286 | 246 | 267 | 1226 | 282 | |

| Quartile 3 | 1120 | 324 | 351 | 364 | 1471 | 332 | |

| Quartile 4 | 1049 | 297 | 290 | 307 | 133·9 | 299 | |

| Height status * | 0·178 | ||||||

| Short | 420 | 126 | 121 | 126 | 541 | 126 | |

| Average | 226·4 | 647 | 65·4 | 685 | 2918 | 654 | |

| Tall | 758 | 228 | 163 | 189 | 921 | 220 | |

| BMI status† | 0·005 | ||||||

| Normal | 2662 | 806 | 737 | 880 | 3399 | 820 | |

| Overweight | 264 | 82 | 50 | 64 | 314 | 79 | |

| Obese | 362 | 112 | 40 | 56 | 402 | 101 | |

| Birth weight (kg) * | 0·023 | ||||||

| <2·5 | 16 | 31 | 25 | 90 | 41 | 54 | |

| 2·5–3·9 | 456 | 924 | 274 | 872 | 730 | 903 | |

| ≥4·0 | 26 | 46 | 15 | 38 | 41 | 43 | |

| Baby feeding patterns * | 0·201 | ||||||

| Breast-feeding only | 106 | 219 | 74 | 228 | 180 | 223 | |

| Formula feeding only | 70 | 139 | 28 | 82 | 98 | 117 | |

| Mixed feeding | 322 | 642 | 212 | 690 | 534 | 661 | |

| Chronic disease | 0·217 | ||||||

| No | 2805 | 814 | 793 | 839 | 3598 | 819 | |

| Yes | 637 | 186 | 145 | 161 | 782 | 181 | |

| Use of nutrition facts label | 0·035 | ||||||

| Yes | 326 | 206 | 63 | 297 | 389 | 217 | |

| No | 1288 | 794 | 160 | 703 | 1448 | 783 | |

| Breakfast frequency per week | <0·001 | ||||||

| 5–7 times | 2525 | 696 | 805 | 845 | 3333 | 726 | |

| 3–4 times | 390 | 115 | 77 | 90 | 467 | 110 | |

| 0–2 times | 527 | 189 | 53 | 65 | 580 | 164 | |

DS, dietary supplement.

Birth weight and feeding patterns during infancy were surveyed in the subjects <aged 4 years.

Use of nutrition facts label was surveyed in subjects aged ≥10 years.

The types of dietary supplements consumed by the study subjects according to the subjects’ characteristics

Adjusted proportions of DS types consumed by the study population, according to the demographics and lifestyles, are presented in Table 2. Younger participants consumed more multivitamin/mineral supplements, vitamin D and Zn than older participants. The only DS type intake that increased with age was vitamin C. Although most of the DS types were consumed more in the normal-weight subjects than in the obese subjects, pro/prebiotics was the only DS type that showed a statistically significant difference according to obesity status. The subjects who were born with low birth weight showed as high as 65·4 % of the total DS use and demonstrated higher use of multivitamin/mineral supplements and vitamin D than those without low birth weight. n-3/fish oil supplement use was significantly more prevalent in the breast-/formula feeding group than in the mixed feeding group. In contrast, Zn supplement use was significantly higher in the breast-feeding group than the other feeding pattern groups. Multivitamin/mineral and vitamin D supplements were also more frequently used in the breast-feeding group, compared with the formula or mixed feeding group, which was not statistically significant. The vitamin C intake rate was significantly higher in children and adolescents with chronic diseases than in those without chronic diseases, while the total DS use rate was not significantly different among these groups. The type of DS that showed higher intakes in adolescents who check the nutrition facts labels was n-3/fish oil and other supplements. Subjects who had breakfast more than five times a week showed significantly higher use of pro/prebiotics, multivitamin/mineral supplements and Zn than those who did not.

Table 2.

Types of dietary supplements consumed by Korean children and adolescents

| Prevalence of DS use | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total DS | Pro/prebiotics | MVM | Others | Vitamin C | ω-3/fish oil | Vitamin D | Ca | Zn | Red ginseng | |||||||||||

| % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | % | se | |

| Total | 20·3 | 1·0 | 7·8 | 0·6 | 7·5 | 0·7 | 3·6 | 0·4 | 3·3 | 0·5 | 2·0 | 0·3 | 1·7 | 0·3 | 1·1 | 0·3 | 1·1 | 0·2 | 0·9 | 0·3 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 19·0 | 1·2 | 7·2 | 0·7 | 6·9 | 0·8 | 3·2 | 0·5 | 3·0 | 0·6 | 2·0 | 0·4 | 1·7 | 0·3 | 1·2 | 0·4 | 1·1 | 0·3 | 1·0 | 0·4 |

| Female | 21·7 | 1·4 | 8·4 | 0·9 | 8·1 | 1·0 | 4·1 | 0·7 | 3·7 | 0·7 | 2·1 | 0·5 | 1·8 | 0·4 | 1·0 | 0·4 | 1·1 | 0·3 | 0·7 | 0·3 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1–3 | 39·2*** | 2·4 | 20·9 | 2·0 | 14·2*** | 2·0 | 6·2 | 1·2 | 2·7* | 0·8 | 2·7 | 0·8 | 5·4*** | 1·3 | 1·8 | 0·6 | 3·1*** | 0·8 | 0·1 | 0·1 |

| 4–6 | 27·9 | 2·4 | 13·7 | 1·7 | 13·4 | 2·0 | 3·1 | 0·8 | 1·0 | 0·4 | 3·2 | 1·0 | 1·6 | 0·5 | 1·6 | 0·7 | 2·4 | 0·7 | 0·5 | 0·3 |

| 7–9 | 21·5 | 2·3 | 8·0 | 1·4 | 10·3 | 1·7 | 3·2 | 0·9 | 3·0 | 0·9 | 2·3 | 0·9 | 1·3 | 0·5 | 0·9 | 0·4 | 0·4 | 0·3 | 0·7 | 0·4 |

| 10–12 | 13·3 | 1·9 | 4·4 | 0·3 | 3·8 | 1·0 | 2·6 | 0·9 | 3·1 | 1·0 | 0·8 | 0·4 | 0·6 | 0·3 | 0·5 | 0·3 | 0·6 | 0·4 | 0·7 | 0·4 |

| 13–15 | 13·3 | 2·0 | 1·3 | 0·6 | 2·1 | 1·0 | 4·6 | 1·3 | 5·6 | 1·5 | 1·9 | 1·0 | 1·3 | 0·8 | 0·9 | 0·4 | 0·6 | 0·5 | 1·3 | 0·7 |

| 16–18 | 10·7 | 1·8 | 1·4 | 0·8 | 2·9 | 0·9 | 2·6 | 0·9 | 4·1 | 1·1 | 1·4 | 0·6 | 0·7 | 0·4 | 1·1 | 0·8 | 0 | – | 1·6 | 0·8 |

| Household income | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Quartile 1 | 14·4 | 2·6 | 3·2* | 1·3 | 4·6 | 1·8 | 2·7 | 1·4 | 6·9 | 2·4 | 3·2 | 1·9 | 1·8 | 1·5 | 0 | – | 0·1 | 0·1 | 2·3 | 1·4 |

| Quartile 2 | 19·2 | 1·7 | 6·8 | 1·0 | 7·1 | 1·2 | 3·6 | 0·8 | 2·6 | 0·6 | 1·9 | 0·6 | 1·8 | 0·6 | 0·9 | 0·4 | 1·3 | 0·4 | 1·2 | 0·6 |

| Quartile 3 | 22·2 | 1·9 | 8·9 | 1·2 | 9·0 | 1·3 | 3·3 | 0·7 | 3·5 | 1·0 | 1·9 | 0·6 | 1·7 | 0·5 | 1·9 | 0·6 | 1·2 | 0·4 | 0·4 | 0·2 |

| Quartile 4 | 20·8 | 1·9 | 8·8 | 1·2 | 7·0 | 1·2 | 4·3 | 0·9 | 2·8 | 0·6 | 1·9 | 0·6 | 1·6 | 0·5 | 0·8 | 0·3 | 1·1 | 0·5 | 0·7 | 0·3 |

| Obesity status | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Normal | 20·5** | 1·1 | 7·4** | 0·7 | 7·7 | 0·9 | 3·4 | 0·5 | 3·4 | 0·5 | 2·2 | 0·3 | 1·6 | 0·3 | 1·3 | 0·3 | 1·2 | 0·3 | 1·0 | 0·3 |

| Overweight | 15·5 | 3·2 | 5·0 | 1·4 | 7·3 | 2·3 | 3·9 | 2·2 | 3·2 | 1·8 | 2·3 | 1·7 | 1·7 | 1·7 | 0·6 | 0·6 | 0·3 | 0·3 | 0 | – |

| Obese | 10·6 | 2·3 | 2·8 | 0·9 | 3·9 | 13 | 3·9 | 1·6 | 2·2 | 1·0 | 0·7 | 0·4 | 0·6 | 0·4 | 0·2 | 0·2 | 0·5 | 0·3 | 0·6 | 0·6 |

| Birth weight (kg)† | ||||||||||||||||||||

| <2·5 | 65·4* | 10·0 | 25·6 | 9·8 | 34·0* | 13·0 | 5·4 | 5·3 | 9·4 | 6·4 | 7·9 | 7·5 | 11·2** | 7·6 | 3·3 | 3·3 | 3·3 | 3·3 | 0 | – |

| 2·5–3·9 | 37·8 | 2·4 | 20·5 | 2·2 | 13·4 | 1·8 | 6·1 | 1·2 | 2·4 | 0·8 | 2·3 | 0·8 | 4·4 | 1·0 | 1·5 | 0·6 | 2·8 | 0·8 | 0·1 | 0·1 |

| ≥4·0 | 34·9 | 10·9 | 23·7 | 9·8 | 6·2 | 5·9 | 9·8 | 6·5 | 0 | – | 3·9 | 3·8 | 20·1 | 8·6 | 6·2 | 5·9 | 11·2 | 7·4 | 0 | – |

| Baby feeding patterns† | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Breast-feeding only | 42·6 | 6·6 | 16·7 | 3·7 | 13·6 | 4·3 | 5·3 | 2·0 | 4·5 | 2·2 | 6·8*** | 2·7 | 8·5 | 2·7 | 2·0 | 1·4 | 73* | 3·0 | 0 | – |

| Formula feeding only | 29·7 | 7·5 | 18·2 | 4·9 | 9·4 | 4·8 | 1·0 | 1·1 | 0 | – | 8·1 | 4·4 | 2·3 | 1·7 | 2·8 | 2·7 | 1·8 | 1·8 | 0 | – |

| Mixed feeding | 40·3 | 33 | 22·8 | 2·6 | 15·3 | 2·4 | 7·4 | 1·5 | 2·5 | 0·9 | 0·3 | 0·3 | 4·9 | 1·4 | 1·5 | 0·6 | 2·0 | 0·7 | 0·1 | 0·1 |

| Chronic disease | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No | 20·8 | 10 | 8·1 | 0·7 | 7·5 | 0·8 | 3·9 | 0·5 | 2·9 | 0·4 | 2·2 | 0·4 | 1·8 | 0·3 | 1·1 | 0·3 | 1·1 | 0·2 | 0·8 | 0·3 |

| Yes | 18·0 | 2·0 | 6·2 | 1·1 | 7·1 | 1·4 | 2·3 | 0·7 | 5·4* | 1·4 | 1·2 | 0·6 | 1·5 | 0·5 | 1·2 | 0·8 | 1·1 | 0·5 | 1·3 | 0·5 |

| Use of nutrition facts label‡ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 16·9* | 2·5 | 2·1 | 0·9 | 4·4 | 1·5 | 6·3* | 2·0 | 5·6 | 1·8 | 4·5*** | 1·6 | 1·9 | 1·2 | 0·6 | 0·4 | 0·9 | 0·7 | 2·5 | 1·3 |

| No | 11·1 | 1·2 | 2·3 | 0·6 | 2·5 | 0·6 | 2·4 | 0·5 | 3·9 | 0·9 | 0·6 | 0·3 | 0·6 | 0·2 | 0·9 | 0·4 | 0·3 | 0·2 | 1·0 | 0·4 |

| Breakfast frequency | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5–7 times per week | 23·6*** | 1·2 | 9·4*** | 0·7 | 8·9*** | 0·9 | 3·8 | 0·5 | 3·5 | 0·6 | 2·3 | 0·4 | 1·8 | 0·3 | 1·2 | 0·3 | 1·4* | 0·3 | 1·1 | 0·3 |

| 3–4 times per week | 16·6 | 2·8 | 4·9 | 1·5 | 6·2 | 1·8 | 4·9 | 1·9 | 4·9 | 1·6 | 1·8 | 1·2 | 2·6 | 1·3 | 0·5 | 0·4 | 1·1 | 0·7 | 0·6 | 0·6 |

| 0–2 times per week | 8·0 | 1·6 | 2·5 | 1·2 | 2·0 | 0·7 | 1·9 | 0·6 | 1·5 | 0·7 | 0·9 | 0·4 | 0·9 | 0·5 | 1·2 | 0·5 | 0·1 | 0·1 | 0 | – |

DS, dietary supplement; MVM, multivitamin/mineral supplements.

*P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001. CSTABULATE was conducted to compare the prevalence of dietary supplements uses within the variables.

Birth weight and feeding patterns during infancy were surveyed in subjects < aged 4 years.

Use of nutrition facts label was surveyed in subjects aged ≥10 years.

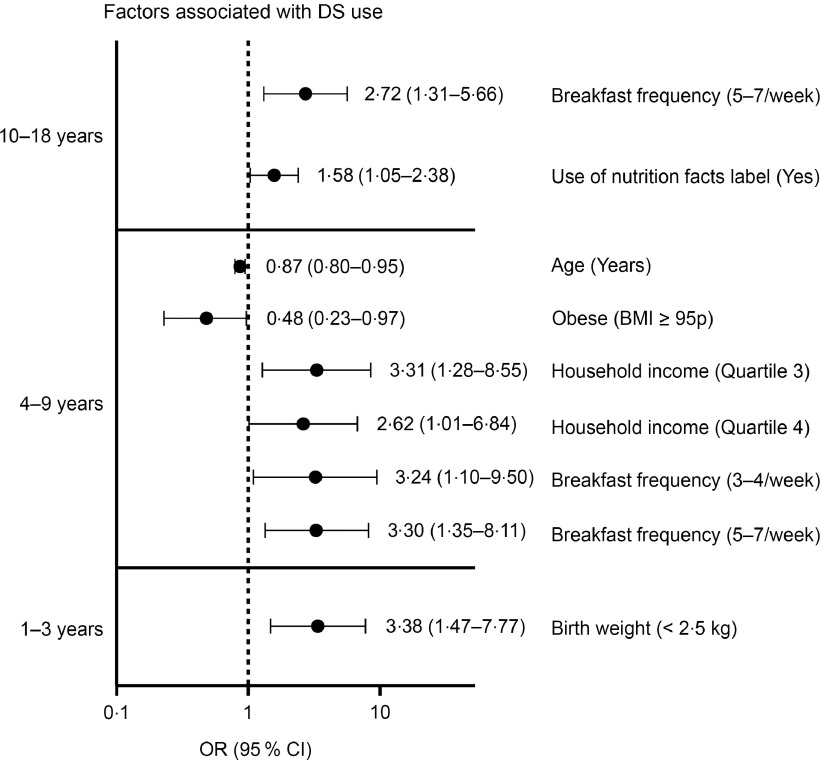

Factors associated with DS use

Independent predictors (OR (95 % CI)) associated with DS use, according to the age groups, are presented in Figure 3. In children aged < 4 years, a history of low birth weight was the only significant factor associated with DS use (3·38 (95 % CI 1·47, 7·77)). In children aged 4–9 years, higher household income (Q3, 3·31 (95 % CI 1·28, 8·55); Q4, 2·62 (95 % CI 1·01, 6·84)) and higher breakfast frequency (3–4/week, 3·24 (95 % CI 1·10, 9·50); 5–7/week, 3·30 (95 % CI 1·35, 8·11)) were significant predictors for DS use. On the other hand, older age (0·87 (95 % CI 0·80, 0·95)) and obesity (0·48 (95 % CI 0·23, 0·97)) were found to be factors of decreased use of DS. For adolescents aged 10 years and older, higher breakfast frequency (5–7/week, 2·72 (95 % CI 1·31, 5·66)) and use of nutrition facts labels (1·58 (95 % CI 1·05, 2·38)) were identified as predictors associated with DS use.

Fig. 3.

Factors (OR and 95 % CI) associated with dietary supplement use. For aged 1–3 years, covariates include age, sex, quartiles of household income, baby feeding patterns (breast-feeding only, formula feeding and mixed feeding), chronic disease (yes v. no) and breakfast frequency (0–2, 3–4, 5–7 times/week). For aged 4–9 years, covariates include sex, chronic disease (yes v. no). For aged ≥ 10 years, covariates include sex, quartiles of household income and chronic disease (yes v. no). References: sex = boys, household income = quartile 1, birth weight ≥ 2·5 kg, baby feeding patterns = breast-feeding only, chronic disease = no, breakfast frequency = 0–2 times/week, obesity status = obese (BMI ≥ 95 percentile), use of nutrition facts label = no

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the prevalence of DS use in children and adolescents in Korea. The DS intake rate of Korean children and adolescents was about 20 %; the highest was 39 % in 1–3 years old, and the lowest was 12 % in teenagers. The highest intakes were pro/prebiotics and multivitamin/mineral supplements, followed by other DS, including botanical supplements, Fe and propolis. DS intake was associated with low birth weight at age 1–3 years; younger age, higher income, regular breakfast intake and lower BMI at age 4–9 years; and regular breakfast intake and use of nutrition facts labels at age 10–18 years.

In a previous study that used data from the KNHANES 2007–2009, DS use in the Korean paediatric population was about 34 %(9), which is significantly higher than that in our findings (20·3 %) from the KNHANES 2015–2017. Of note, the DS questionnaire conducted in the 2007–2009 survey was based on DS taken over the last 2 weeks, while that of the 2015–2017 survey was based on the 24-h food recall. Therefore, the lower DS use in the 2015–2017 survey compared with the 2007–2009 survey is likely due to the irregularity of DS use, rather than an actual decrease in DS use in this population. Furthermore, we found that DS use in toddlers was similar to that found in the previous study (40 %)(9), but among teenagers, DS use decreased considerably from 23 % to 12 %. These findings might be due to the irregularity of DS use among teenagers, compared with toddlers who are regularly provided with DS by their caregivers. Although a direct comparison is difficult due to the difference in age and survey method of DS use, the prevalence of DS use in this study was similar to that in Japan (8·0–20·4 %) and Germany (25·8 %), while lower than that in the USA (27–34·2%), UK (39 %) and Canada (42·5 %)(4–6, 10–15).

Pro/prebiotics was the most commonly used DS by Korean children and adolescents. In particular, there was a high rate of pro/prebiotics use in toddlers aged 1–3 years. Pro/prebiotics are commonly used to treat constipation, acute infectious diarrhoea and antibiotics-associated diarrhoea and to prevent atopic dermatitis(16). However, the evidence of optimal form, number and strain of viable microbes of pro/prebiotics to reap the expected health benefits is weak(17). Also, there is a stability issue in which the number of microbes should be maintained during the product’s distribution period. Therefore, consumers should be careful to choose appropriate products that are permitted by the ministry of food and drug safety.

The second most consumed DS product among the Korean paediatric population was multivitamin/mineral supplements. Multivitamin/mineral supplements have been reported to contribute to increase the total daily intake of vitamins and minerals in adolescents(15,18). However, reckless DS use should be avoided for adolescents who are well-nourished because of the risk of an overdose of fat-soluble vitamins or minerals. In this study, DS users reported more regular breakfast intake and the use of nutrition facts labels, suggesting that there is a higher risk for overnutrition in DS users.

Moreover, children and adolescents have different nutritional needs, depending on the particular disease or health condition they possess(15). For example, breast-feeding infants and premature infants have increased vitamin D and Fe requirements(19), and individuals with obesity have increased pyridoxine, vitamin D and Fe requirements(20). However, in this study, most toddlers who underwent breast-feeding were not taking multivitamins or vitamin D supplements. Also, an extremely low percentage of children with obesity were using multivitamins and vitamin D supplements. In adolescence, the demand for Ca, Fe and Zn increases with rapid growth(19). Therefore, DS use might be helpful to adolescents who often skip meals or those who are not provided with nutritionally sufficient meals because of their low socio-economic status. However, our study found that adolescents who eat breakfast regularly, have an interest in nutrition facts labels and those who are in a higher socio-economic status tend to consume DS more. This finding was consistent with a previous study based on the 2007–2009 survey(2) and other studies from the USA(4–6,15) and Thailand(21,22). These results warrant the demand for public education on proper DS use in children and adolescents according to their nutritional condition.

In this study, we reported that a low birth weight under 2·5 kg is the main predictor of DS use in Korean toddlers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the overall prevalence of DS use and DS types according to toddlers’ birth weight. Nearly 65·4 % of the Korean toddlers born with low birth weight were using DS, and the major DS types for these children were multivitamin/mineral and vitamin D supplements. Since preterm babies or those born with low birth weight have high requirements for Fe and vitamin D(23), we assume that their relatively high DS intakes were a result of a medical provider’s recommendations.

We acknowledge the following limitations of this study. First, since the KNHANES data are cross-sectional, analyses of DS use with the associated factors in the KNHANES cannot presume causality, but only an association. Second, the DS survey in the 2015–2017 KNHANES was conducted as part of a 24-h food recall, not as a long-term DS questionnaire. Therefore, there is a possibility that the prevalence of DS use might be underestimated. Notwithstanding these limitations, the results of this study offer guidance to health care providers on the extent of data gathering and counselling needed regarding DS use. Our study used the latest nationwide data to outline the current state of DS use for the Korean paediatric population of all ages. Moreover, we included various covariates, including BMI, socio-economic status, lifestyle factors, infantile feeding patterns, that are potentially related to DS use.

Conclusion

In conclusion, over 20 % of the Korean paediatric population take DS, and pro/prebiotics and multivitamin/mineral supplements were the most commonly used DS. Younger age, lower BMI status, low birth weight, use of nutrition facts labels and regular breakfast intake were associated with DS use in this study. Since DS use in children with sufficient nutrition can lead to nutritional imbalances or adverse health outcomes, health care providers need to guide caregivers to provide appropriate DS that meets the children’s nutritional needs.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare for providing raw data from the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.H.K. and M.J.P. were responsible for the conception and design of the study. S.H.K. performed data analysis, and all authors had a role in the interpretation of the data. J.H.J. drafted the manuscript, and M.Y.S., S.H.K. and M.J.P. revised and commented on the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (IRB no. 2013-07CON-03-4c, 2013-12EXP-03-5C). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003419.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. National Institutes of Health (1994) Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 Public Law 103-417. https://ods.od.nih.gov/About/DSHEA_Wording.aspx (accessed March 2020).

- 2. Yoon JY, Park HA, Kang JH et al. (2012) Prevalence of dietary supplement use in Korean children and adolescents: insights from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2009. J Korean Med Sci 27, 512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park JS & Lee JH (2008) Elementary school children’s intake patterns of health functional foods and parent’s requirements in Daejeon area. Korean J Commun Nutr 13, 463. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Thomas PR et al. (2013) Why US children use dietary supplements. Pediatric Res 74, 737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gardiner P, Buettner C, Davis RB et al. (2008) Factors and common conditions associated with adolescent dietary supplement use: an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). BMC Complem Altern Med 8, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jun S, Cowan A, Tooze J et al. (2018) Dietary supplement use among US children by family income, food security level, and nutrition assistance program participation status in 2011–2014. Nutrients 10, 1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang M, Kim DW, Jung HJ et al. (2016) Dietary supplement use and nutrient intake among children in South Korea. J Acad Nutr Diet 116, 1316–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim JH, Yun S, Hwang S-S et al. (2018) The 2017 Korean National Growth Charts for children and adolescents: development, improvement, and prospects. Korean J Pediatr 61, 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoon JY, Park HA, Kang JH et al. (2012) Prevalence of dietary supplement use in Korean children and adolescents: insights from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2009. J Korean Med Sci 27, 512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bell A, Dorsch KD, Mccreary DR et al. (2004) A look at nutritional supplement use in adolescents. J Adolesc Health 34, 508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sichert-Hellert W & Kersting M (2004) Vitamin and mineral supplements use in German children and adolescents between 1986 and 2003: results of the DONALD Study. Ann Nutr Metab 48, 414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thane C, Bates C & Prentice A (2004) Zinc and vitamin A intake and status in a national sample of British young people aged 4–18 y. Eur J Clin Nutr 58, 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sato Y, Suzuki S, Chiba T et al. (2016) Factors associated with dietary supplement use among preschool children: results from a nationwide survey in Japan. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 62, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mori N, Kubota M, Hamada S et al. (2011) Prevalence and characterization of supplement use among healthy children and adolescents in an urban Japanese city. Health 3, 135. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shaikh U, Byrd RS & Auinger P (2009) Vitamin and mineral supplement use by children and adolescents in the 1999–2004 national health and nutrition examination survey: relationship with nutrition, food security, physical activity, and health care access. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163, 150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ball SD, Kertesz D & Moyer-Mileur LJ (2005) Dietary supplement use is prevalent among children with a chronic illness. J Am Diet Assoc 105, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dalli SS, Uprety BK & Rakshit SK (2017) Industrial production of active probiotics for food enrichment. In Engineering Foods for Bioactives Stability and Delivery, 1st ed., pp. 85–118 [Roos YH and Livney YD, editors]. New York: Springer-Verlag New York. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dwyer JT, Garceau AO, Evans M et al. (2001) Do adolescent vitamin-mineral supplement users have better nutrient intakes than nonusers? Observations from the CATCH tracking study. J Am Diet Assoc 101, 1340–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Butte NF, Fox MK, Briefel RR et al. (2010) Nutrient intakes of US infants, toddlers, and preschoolers meet or exceed dietary reference intakes. J Am Diet Assoc 110, S27–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xanthakos SA (2009) Nutritional deficiencies in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Pediatr Clin North Am 56, 1105–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen SY, Lin JR, Kao MD et al. (2007) Dietary supplement usage among elementary school children in Taiwan: their school performance and emotional status. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 16, Suppl. 2, 554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chuang CH, Yang SH, Chang PJ et al. (2012) Dietary supplement intake by 6-month-old Taiwanese infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agostoni C, Buonocore G, Carnielli VP et al. (2010) Enteral nutrient supply for preterm infants: commentary from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 50, 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003419.

click here to view supplementary material