Abstract

Background

Adults aged ≥ 60 years are often underrepresented in atopic dermatitis (AD) clinical trials; age-related comorbidities may impact treatment efficacy and safety.

Objective

The aim was to report dupilumab efficacy and safety in patients aged ≥ 60 years with moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

Data were pooled from four randomized, placebo-controlled dupilumab trials of patients with moderate-to-severe AD (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2, LIBERTY AD CAFÉ, and LIBERTY AD CHRONOS) and stratified by age (< 60 [N = 2261] and ≥ 60 [N = 183] years). Patients received dupilumab 300 mg every week (qw) or every 2 weeks (q2w), or placebo with/without topical corticosteroids. Post hoc efficacy at week 16 was examined using broad categorical and continuous assessments of skin lesions, symptoms, biomarkers, and quality of life. Safety was also assessed.

Results

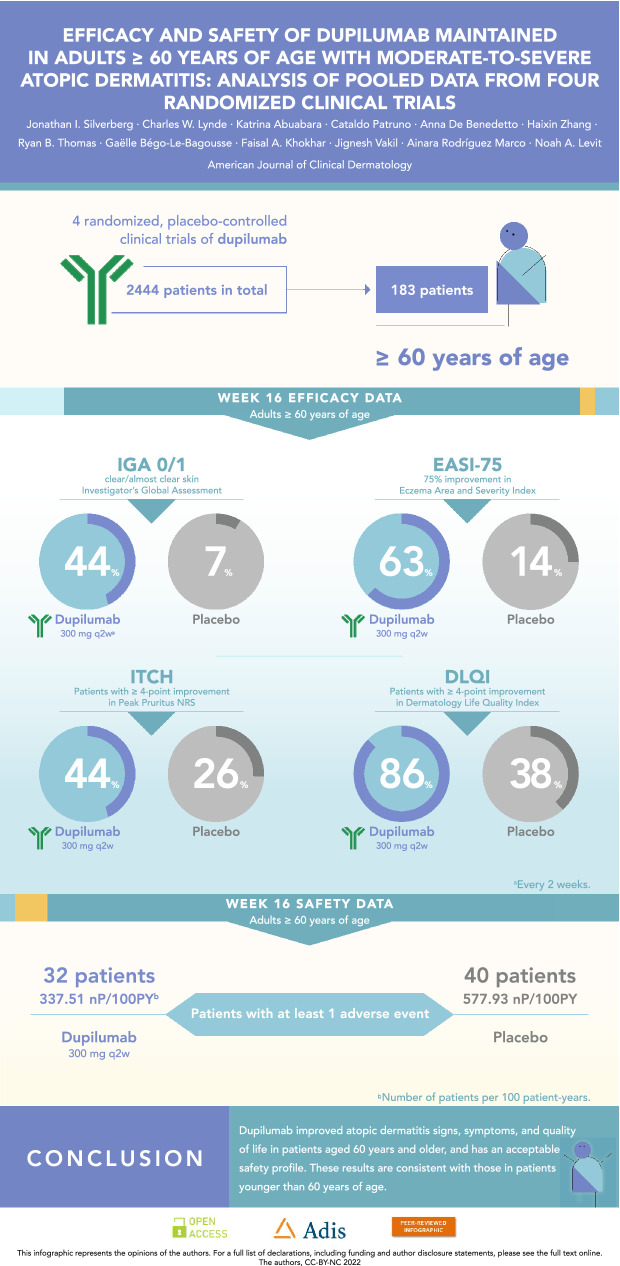

In the ≥ 60-year-old group at week 16, a greater proportion of dupilumab-treated patients achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 (q2w: 44.4%; qw: 39.7%) and 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (63.0%; 61.6%) versus placebo (7.1% and 14.3%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Type 2 inflammation biomarkers (immunoglobulin E and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine) were also significantly reduced in dupilumab- versus placebo-treated patients (P < 0.01). Results were similar in the < 60-year-old group. The exposure-adjusted incidences of adverse events in dupilumab-treated patients were generally similar to those receiving placebo, with numerically fewer treatment-emergent adverse events in the dupilumab-treated ≥ 60-year-old group versus placebo.

Limitations

There were fewer patients in the ≥ 60-year-old group; post hoc analyses.

Conclusion

Dupilumab improved AD signs and symptoms in patients aged ≥ 60 years; results were comparable to those in patients aged < 60 years. Safety was consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02277743, NCT02277769, NCT02755649, NCT02260986.

Graphical abstract

Video abstract

Does dupilumab benefit adults aged 60 years and older with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis?(MP4 20,787 KB)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-022-00754-4.

| Digital Features for this article can be found at 10.6084/m9.figshare.22028006. |

Key Points

| Dupilumab, with or without topical corticosteroids, improved atopic dermatitis (AD) signs, symptoms, and quality of life in adults ≥ 60 years of age. |

| Dupilumab efficacy in patients ≥ 60 years of age was generally consistent with that seen in patients < 60 years of age; safety findings were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile. |

| In both age groups, dupilumab significantly reduced the AD biomarkers thymus and activation-regulated chemokine and immunoglobulin E compared with placebo. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that impacts around 10% of the population worldwide and may be more common than previously thought in older adults [1–5]; the prevalence of AD in older adults was found to be similar to or higher than that in younger adults [1, 2].

Safety is an important consideration for AD treatment in older adults due to the increased burden of medical comorbidities, age-related changes in drug metabolism, and risks associated with polypharmacy [5]. Treatment options without broad immunosuppressing action are important in older adults, due to heightened age-related considerations. For more elderly patients who may be less independent, options for long-term therapy that do not require frequent laboratory monitoring may be an important practical consideration.

AD is a clinically heterogeneous disorder with phenotypic and endotypic shifts observed across age groups and disease chronicity [5–9]. In infants, exudative lesions and erythema predominate and tend to be localized to the cheeks, forehead, scalp, and extensor areas of the extremities. During childhood, subacute and chronic lesions with scaling and lichenification begin to appear, with prominent involvement of the flexural extremities [8, 10]. In adolescents and adults, erythematous and edematous papules and plaques with variable scaling, excoriation, oozing/crusting, and lichenification are typically located on the head, neck, and flexural areas [8, 10]. In older adults with AD, localized disease of the head/neck and hands/feet, and relatively less involvement of the flexural areas of arms and legs, is typical, but lesions may affect any skin site [8, 11, 12]. Rates of some distinct lesional morphologies were reported to be at least twofold higher in adults, including erythrodermic AD, papular/lichenoid eczematous dermatitis, nummular eczema, and AD complicated by prurigo nodularis [13].

Dupilumab, a fully human VelocImmune®-derived [14, 15] monoclonal antibody that blocks the shared receptor subunit for interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, is approved for patients with type 2 inflammatory diseases, including AD, asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and eosinophilic esophagitis [16, 17]. In phase III clinical trials, dupilumab improved AD signs and symptoms, improved quality of life, and had an acceptable safety profile across age groups [18–24]. Similar to clinical trials for other AD treatments, older adults are underrepresented in adult dupilumab clinical trials [25, 26]. Here, we pooled data from four adult dupilumab clinical trials and stratified patients by age (< 60 and ≥ 60 years of age) to examine the efficacy and safety of dupilumab, with or without topical corticosteroids (TCS), in patients ≥ 60 years of age. We further describe baseline levels and changes in immunoglobulin E (IgE) and serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC), which serve as markers of systemic type 2 inflammation, known to correlate with AD severity [27–29].

Methods

Study Design, Patients, and Treatment

This was a pooled analysis of four phase III, randomized, multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 [NCT02277743]; LIBERTY AD SOLO 2 [NCT02277769]; LIBERTY AD CAFÉ [NCT02755649]; and LIBERTY AD CHRONOS [NCT02260986]). Detailed study designs are reported in previous publications [18–20]. Briefly, SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 were 16-week monotherapy trials of identical design, conducted independently and in parallel at study sites across North America, Europe, and Asia. The studies enrolled adults with moderate-to-severe AD with a history of inadequate response to topical treatments, or for whom such therapies were medically inadvisable. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive subcutaneous (SC) dupilumab 300 mg every week (qw), 300 mg every 2 weeks (q2w), or placebo. Concomitant TCS were not permitted, but patients could use topical therapies as rescue treatment. In the United States, the primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with a ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline. In Europe, there were two primary co-endpoints: an IGA score of 0 or 1 with a ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline, and the proportion of patients achieving a 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75). CHRONOS was a 52-week trial conducted at approximately 161 study sites across North America, Europe, and Asia. The study enrolled adults with moderate-to-severe AD with a history of inadequate response to TCS. Patients were randomized 3:1:3 to receive SC dupilumab 300 mg qw, 300 mg q2w, or placebo with concomitant TCS (or topical calcineurin inhibitors [TCI] if TCS were inadvisable). Coprimary endpoints were the proportion of patients achieving an IGA of score 0/1 with a ≥ 2-point reduction and the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75. CAFÉ was a 16-week trial conducted in ten European countries. The study enrolled adults with moderate-to-severe AD who had a history of inadequate response or intolerance to the widely used immunosuppressant cyclosporine A (CsA), or for whom CsA was medically inadvisable. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive SC dupilumab 300 mg qw, 300 mg q2w, or placebo with concomitant TCS. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75.

Ethics

All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and local applicable regulatory requirements, including institutional review board approval. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Outcomes Assessed in this Analysis

Efficacy was assessed by the proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0/1 with a ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline, and the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75. Additional outcomes included the following: least squares (LS) mean change in EASI, LS mean change in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 4-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS, the proportion of patients achieving a 4-point reduction in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), the proportion of patients achieving a 4-point reduction in Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), LS mean change in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), LS mean change in SCORAD Sleep Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and LS mean change in EuroQol 5-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) pain/discomfort. IgE and TARC biomarkers were also assessed based on the LS mean change in total IgE, the percentage change in total IgE, the LS mean change in TARC, and the percentage change in TARC.

Safety outcomes were assessed over the 16-week treatment period and included the following: prevalence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), drug-related TEAEs, TEAEs leading to permanent drug discontinuation, maximum TEAE intensity, death, serious TEAEs, drug-related serious TEAEs, and serious TEAEs leading to permanent drug discontinuation. According to the European Patients’ Academy for Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI) [30], an adverse event is defined as any undesirable event occurring after a participant officially consents to take part in a trial (and could occur before treatment begins). The most common TEAEs by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred term (PT) were also reported.

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy analyses were performed using the full analysis set (all randomized patients), while safety analyses were performed using the safety analysis set (all patients who received at least one dose of study drug). All analyses included data up to week 16. This post hoc, subgroup analysis stratified patients by age (< 60 and ≥ 60 years of age); only descriptive comparisons were made between the age groups. All P values were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

A total of 2444 patients were included in this analysis, of whom 183 were ≥ 60 years of age and 2261 were < 60 years of age. Among patients ≥ 60 years of age, 56 received placebo, 54 received dupilumab 300 mg q2w, and 73 received dupilumab 300 mg qw. Among patients < 60 years of age, 827 received placebo, 616 received dupilumab 300 mg q2w, and 818 received dupilumab 300 mg qw. The median age (interquartile range [IQR]) of patients in the ≥ 60 age group was 65 (62.0–69.0), while the median age of patients in the < 60 age group was 35 (25.0–45.0) years (Table 1). TCS use differed across the adult studies. Most patients included in this analysis were taken from the SOLO pooled monotherapy studies, where topical therapy use was an exclusion criterion at baseline. Among the ≥ 60-year-old group included in this analysis, monotherapy patients from SOLO comprised 57.1% of the placebo group (32/56), 72.2% of the dupilumab 300 mg q2w group (39/54), and 53.4% of the dupilumab 300 mg qw group (39/73), with similar proportions for the < 60-year-old group (placebo: 51.8%, 428/827; dupilumab 300 mg q2w: 67.9%, 418/616; dupilumab 300 mg qw: 51.7%, 423/818). The remaining patients were from CHRONOS and CAFÉ, where concomitant low/medium-potency TCS use were required. For all studies, high-/ultra-potent TCS constituted rescue medication for the purposes of the binary efficacy endpoints, after which patients were classified as non-responders from the time of rescue and not included in the endpoint analyses, and any further data were set to missing.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Age ≥ 60 years | Age < 60 years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo qw (n = 56) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q2w (n = 54) |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 73) |

Total (N = 183) |

Placebo qw (n = 827) |

Dupilumab 300 mg q2w (n = 616) |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 818) |

Total (N = 2261) |

||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||||

| Age, median (Q1–Q3), years |

65.0 (63.0–69.0) |

66.0 (63.0–72.0) |

64.0 (62.0–68.0) |

65.0 (62.0–69.0) |

35.0 (25.0–45.0) |

35.0 (26.0–45.0) |

34.0 (25.0–45.0) |

35.0 (25.0–45.0) |

|

| Male sex, n (%) | 31 (55.4) | 33 (61.1) | 45 (61.6) | 109 (59.6) | 480 (58.0) | 361 (58.6) | 493 (60.3) | 1334 (59.0) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||||

| White | 53 (94.6) | 48 (88.9) | 69 (94.5) | 170 (92.9) | 561 (67.8) | 450 (73.1) | 561 (68.6) | 1572 (69.5) | |

| Black/African American | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.6) | 3 (4.1) | 7 (3.8) | 54 (6.5) | 22 (3.6) | 47 (5.7) | 123 (5.4) | |

| Asian | 2 (3.6) | 3 (5.6) | 1 (1.4) | 6 (3.3) | 189 (22.9) | 126 (20.5) | 186 (22.7) | 501 (22.2) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.2) | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (1.8) | 9 (1.5) | 18 (2.2) | 42 (1.9) | |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7(0.8) | 7 (1.1) | 4 (0.5) | 18 (0.8) | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||||

| Duration of AD, median (Q1–Q3), years |

40.0 (7.5–62.0) |

51.0 (20.0–62.0) |

41.5 (14.0–60.5) |

45.0 (11.0–61.0) |

27.0 (19.0–38.0) |

26.0 (18.0–37.0) |

26.0 (18.0–38.0) |

26.0 (18.0–38.0) |

|

| BSA % affected by AD, median (Q1–Q3) |

48.3 (36.0–70.0) |

56.3 (38.0–72.0) |

52.0 (38.0–67.1) |

52.0 (37.0–69.0) |

55.0 (38.0–74.5) |

54.0 (39.0–71.0) |

53.0 (37.0–70.5) |

54.0 (38.0–72.3) |

|

| EASI score, median (Q1–Q3) |

27.8 (21.6–43.2) |

29.9 (21.4–40.1) |

29.3 (24.3–39.3) |

29.4 (22.0–40.4) |

30.8 (22.6–41.9) |

30.2 (22.4–40.4) |

29.4 (21.8–40.9) |

30.0 (22.2–41.0) |

|

| IGA score, n (%) | |||||||||

| 4 | 29 (51.8) | 30 (55.6) | 41 (56.2) | 100 (54.6) | 395 (47.8) | 296 (48.1) | 376 (46.0) | 1067 (47.2) | |

| 3 | 27 (48.2) | 24 (44.4) | 32 (43.8) | 83 (45.4) | 431 (52.1) | 320 (51.9) | 441 (53.9) | 1192 (52.7) | |

| Peak Pruritus NRS, median (Q1–Q3) | 8.0 (5.8–9.0) | 8.0 (6.6–9.0) | 7.9 (5.6–8.9) | 8.0 (6.0–9.0) | 7.6 (6.2–8.6) | 7.6 (6.1–8.6) | 7.4 (6.0–8.6) | 7.6 (6.1–8.6) | |

| SCORAD—total score, median (Q1–Q3) |

66.4 (58.6–78.1) |

66.8 (60.0–78.3) |

69.8 (56.5–75.8) |

68.1 (58.5–76.7) |

66.4 (57.3–77.3) |

67.4 (57.5–77.2) |

66.0 (56.5–76.5) |

66.5 (57.1–76.9) |

|

| POEM, median (Q1–Q3) |

21.0 (14.0–23.5) |

20.0 (14.0–24.0) |

20.0 (16.0–24.0) |

20.0 (15.0–24.0) |

21.0 (16.0–25.0) |

21.0 (16.0–25.0) |

21.0 (16.0–26.0) |

21.0 (16.0–25.0) |

|

| DLQI score, median (Q1–Q3) |

11.5 (6.5–18.0) |

12.0 (8.0–19.0) |

11.0 (7.0–17.0) |

12.0 (7.0–18.0) |

14.0 (9.0–21.0) |

14.0 (9.0–21.0) |

14.0 (9.0–21.0) |

14.0 (9.0–21.0) |

|

AD atopic dermatitis, BSA body surface area, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, Q quartile, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis

With the exception of age, baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar across treatment and age groups (Table 1). However, a greater proportion of patients in the ≥ 60 age group were White (92.9%) compared with the < 60 age group (69.5%), while a greater proportion of patients in the < 60 age group were Asian compared with the ≥ 60 age group (22.2% vs 3.3%). At least half of the participants in the ≥ 60 age group appeared to have teen- or adult-onset AD (with a median AD duration [IQR] of 45.0 [11.0–61.0] years). Reported history of atopic comorbidities was also similar across age and treatment groups, with numerically higher rates of asthma, allergies, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and allergic conjunctivitis in the < 60 age group (Table 2). Baseline values of total IgE among patients ≥ 60 years of age were lower in all treatment groups compared with patients < 60 years of age (P = 0.0013), while TARC values were generally similar across both treatment and age groups (P = 0.8029) (Table 2; Fig. S1, Online Resource, see the electronic supplementary material).

Table 2.

Baseline type 2 biomarkers and history of atopic comorbidities

| Age ≥ 60 years | Age < 60 years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo qw | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw |

Total | Placebo qw | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw |

Total | |

| Laboratory characteristics | ||||||||

| Total IgE (IU/mL), median (IQR), n |

1665.5 (196.0–6559.0), n = 56 |

1364.5 (71.0–7360.0), n = 54 |

837.0 (123.0–6711.0), n = 73 |

1172.0 (123.0–7338.0)a, N = 183 |

3561.0 (595.0–10,000.0), n = 823 |

3187.5 (625.5–10,000.0), n = 616 |

2825.0 (548.0–10,000.0), n = 817 |

3136.0 (582.0–10,000.0)a, N = 2256 |

| TARC (pg/mL), median (IQR), n |

2629.1 (874.5–9151.5), n = 56 |

2871.5 (936.0–8054.0), n = 54 |

2273.0 (899.7–6655.0), n = 73 |

2602.1 (899.7–7355.0), N = 183 |

2258.7 (915.0–6722.8), n = 821 |

2295.5 (903.0–7011.8), n = 614 |

1943.3 (823.0–5928.0), n = 813 |

2143.3 (883.3–6584.5), N = 2248 |

| History of atopic comorbidities, n (%) | n = 56 | n = 55 | n = 72 | N = 183 | n = 823 | n = 627 | n = 808 | N = 2258 |

| Asthma | 17 (30.4) | 17 (30.9) | 24 (33.3) | 58 (31.7) | 330 (40.1) | 268 (42.7) | 312 (38.6) | 910 (40.3) |

| Allergiesb | 36 (64.3) | 28 (50.9) | 45 (62.5) | 109 (59.6) | 516 (62.7) | 406 (64.8) | 533 (66.0) | 1455 (64.4) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 22 (39.3) | 24 (43.6) | 26 (36.1) | 72 (39.3) | 386 (46.9) | 315 (50.2) | 397 (49.1) | 1098 (48.6) |

| Food allergy | 15 (26.8) | 10 (18.2) | 23 (31.9) | 48 (26.2) | 293 (35.6) | 254 (40.5) | 313 (38.7) | 860 (38.1) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 11 (19.6) | 14 (25.5) | 15 (20.8) | 40 (21.9) | 235 (28.6) | 184 (29.3) | 218 (27.0) | 637 (28.2) |

| Hives | 8 (14.3) | 8 (14.5) | 10 (13.9) | 26 (14.2) | 95 (11.5) | 86 (13.7) | 100 (12.4) | 281 (12.4) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 3 (5.4) | 6 (10.9) | 5 (6.9) | 14 (7.7) | 54 (6.6) | 33 (5.3) | 45 (5.6) | 132 (5.8) |

| Nasal polyps | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 3 (4.2) | 5 (2.7) | 18 (2.2) | 13 (2.1) | 22 (2.7) | 53 (2.3) |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (0.4) |

IgE immunoglobin E, IU international units, IQR interquartile range, mL milliliter, pg picograms, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week, TARC thymus and activation-regulated chemokine

aSignificant differences in total IgE (IU/mL) were observed between the ≥ 60 and < 60 groups (P = 0.0013)

bAllergies other than food

Efficacy

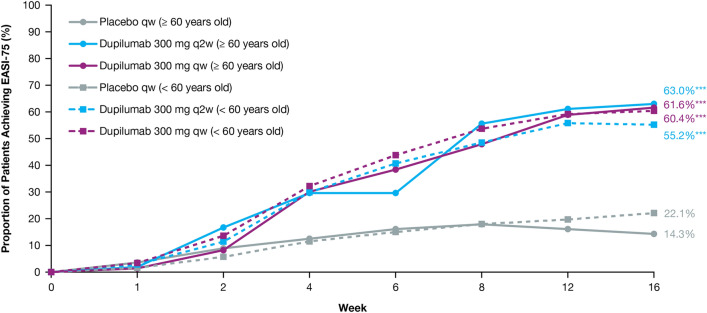

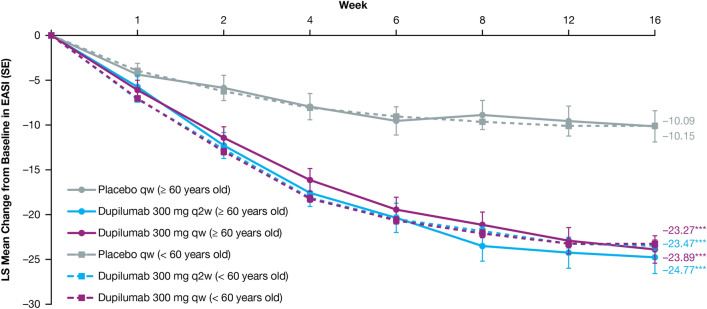

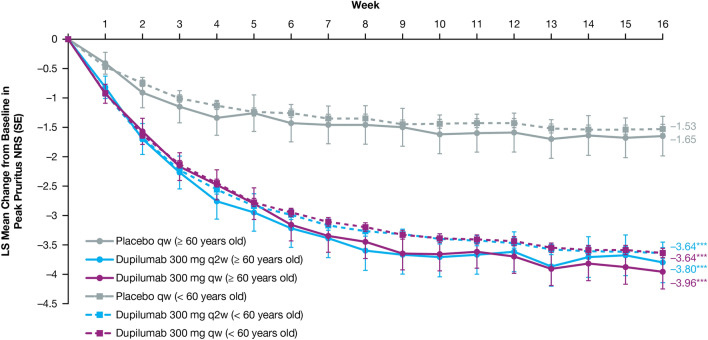

Dupilumab rapidly and significantly improved AD signs and symptoms compared with placebo, with comparable efficacy across age groups (Table 3). In the ≥ 60 age group, the proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 (and a ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline) was greater in those treated with dupilumab (q2w: 44.4%, qw: 39.7%) than in those given placebo (7.1%; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons) at week 16. The proportion of patients achieving EASI-75 in the ≥ 60 age group was also greater in dupilumab-treated patients (q2w: 63.0%, qw: 61.6%) compared with those administered placebo (14.3%; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons), with significantly more patients who received dupilumab versus placebo achieving EASI-75 as early as week 4 for both doses (P < 0.05, Fig. 1). Similar effects were observed at week 16 in the < 60 age group for both IGA 0/1 (q2w: 37.8%, qw: 39.7%, placebo: 12.1%; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons) and EASI-75 (q2w: 55.2%, qw: 60.4%, placebo: 22.1%; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons) (Table 3, Fig. 1). At baseline, mean EASI scores were similar across treatment and age groups (Table 1) and decreased significantly from week 4 through week 16 among dupilumab-treated (qw and q2w) patients compared with placebo-treated patients in both age groups (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons) (Table 3, Fig. 2). The same was observed in both age groups for the LS mean change from baseline in Peak Pruritus NRS from week 5 through week 16 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3), and LS mean change from baseline in DLQI from week 4 through week 16 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Dupilumab also significantly improved several other clinical outcomes compared with placebo in both age groups, including the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 4-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS, the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 4-point improvement in POEM, LS mean change in SCORAD, LS mean change in SCORAD Sleep VAS, and LS mean change in EQ-5D pain/discomfort (Table 3).

Table 3.

Efficacy outcomes at week 16

| Age ≥ 60 years | Age < 60 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo qw (n = 56) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w (n = 54) |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 73) |

Placebo qw (n = 827) | Dupilumab 300 mg q2w (n = 616) |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw (n = 818) |

|

| Patients achieving IGA 0/1 and ≥ 2-point improvement from baseline, n (%) | 4 (7.1) |

24 (44.4) < 0.0001 |

29 (39.7) < 0.0001 |

100 (12.1) |

233 (37.8) < 0.0001 |

325 (39.7) < 0.0001 |

| Patients achieving EASI-75, n (%) | 8 (14.3) |

34 (63.0) < 0.0001 |

45 (61.6) < 0.0001 |

183 (22.1) |

340 (55.2) < 0.0001 |

494 (60.4) < 0.0001 |

| EASI, LS mean change (SE) | − 10.15 (1.742) |

− 24.77 (1.805) < 0.0001 |

− 23.89 (1.530) < 0.0001 |

− 10.09 (0.436) |

− 23.47 (0.495) < 0.0001 |

− 23.27 (0.436) < 0.0001 |

| Peak Pruritus NRS, LS mean change (SE) | − 1.65 (0.337) |

− 3.80 (0.345) < 0.0001 |

− 3.96 (0.292) < 0.0001 |

− 1.53 (0.079) |

− 3.64 (0.091) < 0.0001 |

− 3.64 (0.080) < 0.0001 |

| Patients achieving ≥ 4-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS, n/N1 (%) | 12/47 (25.5) |

23/52 (44.2) 0.0096 |

38/65 (58.5) 0.0003 |

128/776 (16.5) |

262/582 (45.0) < 0.0001 |

353/753 (46.9) < 0.0001 |

| Patients achieving ≥ 4-point improvement in DLQI, n/N1 (%) | 19/50 (38.0) |

43/50 (86.0) < 0.0001 |

50/70 (71.4) 0.0004 |

382/783 (48.8) |

465/579 (80.3) < 0.0001 |

623/783 (79.6) < 0.0001 |

| Patients achieving ≥ 4-point improvement in POEM, n/N1 (%) | 24/56 (42.9) |

42/53 (79.2) < 0.0001 |

60/73 (82.2) < 0.0001 |

343/820 (41.8) |

495/614 (80.6) < 0.0001 |

656/815 (80.5) < 0.0001 |

| SCORAD, LS mean change (SE) | − 14.83 (2.560) |

− 42.21 (2.668) < 0.0001 |

− 40.35 (2.232) < 0.0001 |

− 14.84 (0.686) |

− 37.78 (0.782) < 0.0001 |

− 37.14 (0.687) < 0.0001 |

| SCORAD Sleep VAS, LS mean change (SE) | − 1.28 (0.354) |

− 3.80 (0.369) < 0.0001 |

− 3.74 (0.306) < 0.0001 |

− 1.16 (0.095) |

− 3.45 (0.108) < 0.0001 |

− 3.39 (0.095) < 0.0001 |

| EQ-5D pain/discomfort, LS mean change (SE) | − 0.15 (0.071) |

− 0.54 (0.073) 0.0001 |

− 0.56 (0.062) < 0.0001 |

− 0.21 (0.020) |

− 0.57 (0.022) < 0.0001 |

− 0.57 (0.020) < 0.0001 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL), LS mean change (SE) | 208.60 (429.161) |

− 1833.37 (400.539) 0.0005 |

− 1655.52 (340.953) 0.0006 |

213.63 (121.010) |

− 2635.17 (127.014) < 0.0001 |

− 2375.93 (112.642) < 0.0001 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL), median (Q1–Q3) |

2161.5 (273.0–8445.0) |

731.5 (46.7–3102.0) |

652.5 (67.1–3809.5) |

3966.0 (616.0–10000.0) |

1632.0 (284.0–4923.0) |

1320.5 (283.5–4308.5) |

| TARC (pg/mL) LS mean change (SE) | 956.05 (1564.354) |

− 5770.96 (1489.830) 0.0018 |

− 5671.11 (1249.615) 0.0009 |

− 1071.60 (210.011) |

− 5569.19 (232.172) < 0.0001 |

− 5370.59 (203.903) < 0.0001 |

| TARC (pg/mL), median (Q1–Q3) | 1118.3 (669.0–3882.0) | 422.2 (215.5–657.7) | 393.6 (279.7–696.0) | 1385.0 (648.0–3527.0) | 407.0 (263.1–698.0) | 391.0 (246.5–633.5) |

DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75 75% decrease in EASI, EQ-5D EuroQol – 5 Dimension, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, IgE Immunoglobulin E, IU international units, LS least squares, mL milliliter, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, N1, number of patients with baseline NRS score ≥ 3, pg picograms, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, Q quartile, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SE standard error, TARC thymus and activation-regulated chemokine, VAS visual analog scale

Fig. 1.

Proportion (%) of patients achieving EASI-75. A higher proportion of patients aged < 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw achieved EASI-75 at week 1 vs placebo (P < 0.05), and a higher proportion of patients aged < 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w achieved EASI-75 from week 2 through week 16 vs placebo (P < 0.0001). A higher proportion of patients aged ≥ 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w achieved EASI-75 from week 4 vs placebo (P < 0.05), week 8 vs placebo (dupilumab qw, P < 0.001; dupilumab q2w, P < 0.0001), and from week 12 through week 16 vs placebo (P < 0.0001 for dupilumab qw and q2w). EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-75 75% decrease in EASI, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001

Fig. 2.

LS mean change from baseline in EASI. Patients aged < 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w showed a greater LS mean change from baseline in EASI from week 1 through week 16 vs placebo (P < 0.0001). Patients aged ≥ 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w showed a greater LS mean change from baseline in EASI from week 2 vs placebo (P < 0.05), and from week 4 through week 16 (P < 0.0001). EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, LS least squares, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001

Fig. 3.

LS mean change from baseline in Peak Pruritus NRS. Patients aged < 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w achieved a greater LS mean change from baseline in Peak Pruritus NRS from week 1 through week 16 vs placebo (P < 0.0001). Patients aged ≥ 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw achieved a greater LS mean change from baseline in Peak Pruritus NRS at week 1 vs placebo (P < 0.05), with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w from week 2 vs placebo (P < 0.05), and from week 5 through week 16 (P < 0.0001). LS least squares, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001

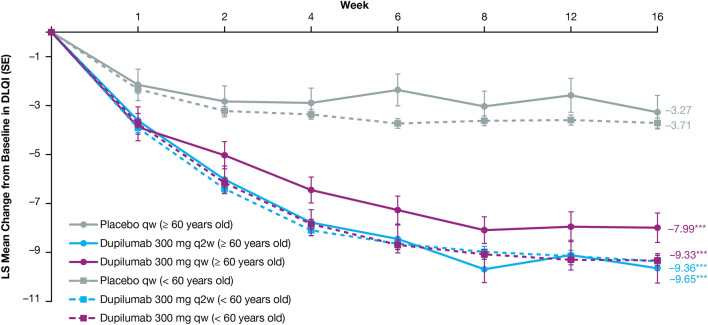

Fig. 4.

LS mean change from baseline in DLQI. Patients aged < 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw or q2w achieved a greater LS mean change from baseline in DLQI from week 1 through week 16 vs placebo (P < 0.0001). Patients aged ≥ 60 years treated with dupilumab 300 mg qw showed a greater LS mean change from baseline in DLQI at week 1 vs placebo (P < 0.05), with dupilumab q2w from week 2 vs placebo (P < 0.001), and with dupilumab qw or q2w from week 4 through week 16 (P < 0.0001). DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, LS least squares, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001

Dupilumab impacted levels of serum T helper 2 (TH2) cell biomarkers TARC and IgE (Table 3). Among patients ≥ 60 years of age, the LS mean change (standard deviation [SD]) in total IgE at week 16 was significantly greater in patients receiving dupilumab q2w (− 1833.37 [400.539]) and qw (− 1655.52 [340.953]) compared with placebo (208.60 [429.161]; P = 0.0005 and P = 0.0006, respectively; Table 3). Similar results were shown in patients < 60 years of age, with a significantly greater LS mean change in total IgE with dupilumab treatment in this age group (q2w: − 2635.17 [127.014], qw: − 2375.93 [112.642]) compared with placebo (213.63 [121.010]; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons). The LS mean change in TARC at week 16 in patients ≥ 60 years of age was also significantly greater in those receiving dupilumab q2w (− 5770.96 [1489.830]) or qw (− 5671.11 [1249.615]) compared with placebo (956.05 [1564.354]; P = 0.0018 and P = 0.0009, respectively, Table 3). Again, results were similar for patients < 60 years of age, with a greater LS mean change in TARC with dupilumab treatment (q2w: − 5569.19 [232.172], qw: − 5370.59 [203.903]) versus placebo (− 1071.60 [210.011]; P < 0.0001 for both comparisons). TARC decreased rapidly with dupilumab treatment (with significant differences observed vs placebo by week 2 for both age groups and dose regimens) and then plateaued for the remainder of the treatment period (Fig. S2, Online Resource, see the electronic supplementary material), while IgE decreased steadily throughout the course of dupilumab treatment (Fig. S3, Online Resource). TARC and IgE values among patients receiving placebo remained steady across the treatment period, with little change from baseline.

Safety

The exposure-adjusted incidence of TEAEs were similar across treatment groups for patients < 60 years of age. For patients ≥ 60 years of age, there were numerically fewer TEAEs per 100 patient years (PY) in the dupilumab groups compared with the placebo group (Table 4). Most TEAEs were of mild-to-moderate severity, with a greater exposure-adjusted incidence of severe TEAEs in the placebo arms compared with the dupilumab arms in both age groups. In the ≥ 60 age group, the number of patients [nP] with a severe event per 100 PY was 40.09 in the placebo arm versus 12.54 nP/100 PY and 9.44 nP/100 PY in patients treated with dupilumab q2w and qw, respectively. In patients < 60 years of age, 31.25 nP/100 PY were reported in the placebo arm, and 18.08 nP/100 PY and 19.27 nP/100 PY among patients treated with dupilumab q2w and qw, respectively. The incidence of TEAEs leading to drug discontinuation was low, but slightly more common among dupilumab-treated patients ≥ 60 years of age (12.21 nP/100 PY and 14.01 nP/100 PY for q2w and qw, respectively) compared with patients < 60 years of age (2.63 nP/100 PY and 5.79 nP/100 PY). No deaths occurred in the ≥ 60 age group, while one death occurred in the < 60 age group but was deemed unrelated to the study drug [19].

Table 4.

Exposure-adjusted safety outcomes during the 16-week treatment period per 100 PY by the safety analysis set

| Total PY | Age ≥ 60 years | Age < 60 years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo qw [n = 56] |

Dupilumab 300 mg q2w [n = 55] |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw [n = 72] |

Placebo qw [n = 823] |

Dupilumab 300 mg q2w [n = 627] |

Dupilumab 300 mg qw [n = 808] |

|||||||

| 16.2 | 16.5 | 21.7 | 247.6 | 190.4 | 243.2 | |||||||

| nE (nE/100 PY) | nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | nE (nE/100 PY) | nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | nE (nE/100 PY) | nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | nE (nE/100 PY) | nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | nE (nE/100 PY) | nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | nE (nE/100 PY) | nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | |

| Any TEAE | 154 (952.40) | 40/6.9 (577.93) | 87 (525.93) | 32/9.5 (337.51) | 147 (678.35) | 52/10.8 (482.18) | 1701 (686.93) | 563/120.6 (466.89) | 1318 (692.10) | 447/90.3 (494.75) | 1794 (737.71) | 560/120.8 (463.47) |

| Any drug-related TEAE | 22 (136.06) | 12/13.0 (92.31) | 25 (151.13) | 11/13.7 (80.32) | 37 (170.74) | 18/17.4 (103.45) | 330 (133.27) | 164/212.1 (77.32) | 397 (208.47) | 183/151.3 (120.97) | 605 (248.78) | 240/193.2 (124.23) |

| Any TEAE causing permanent discontinuation of study drug | 0 | 0 | 3 (18.14) | 2/16.4 (12.21) | 4 (18.46) | 3/21.4 (14.01) | 32 (12.92) | 23/245.2 (9.38) | 6 (3.15) | 5/189.9 (2.63) | 18 (7.40) | 14/241.9 (5.79) |

| Maximum intensity for any TEAE | ||||||||||||

| Mild | 96 (593.70) | 9/14.4 (62.29) | 43 (259.94) | 15/13.7 (109.77) | 94 (433.78) | 16/18.7 (85.35) | 1060 (428.07) | 186/208.4 (89.25) | 935 (490.98) | 214/144.2 (148.39) | 1328 (546.09) | 255/190.8 (133.66) |

| Moderate | 49 (303.04) | 25/9.8 (253.93) | 41 (247.85) | 15/13.0 (115.83) | 50 (230.73) | 34/14.2 (239.42) | 565 (228.17) | 305/177.0 (172.30) | 354 (185.89) | 200/144.5 (138.39) | 431 (177.23) | 260/182.9 (142.18) |

| Severe | 9 (55.66) | 6/15.0 (40.09) | 3 (18.14) | 2/16.0 (12.54) | 3 (13.84) | 2/21.2 (9.44) | 76 (30.69) | 72/230.4 (31.25) | 29 (15.23) | 33/182.5 (18.08) | 35 (14.39) | 45/233.5 (19.27) |

| Any death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.41) | 1/243.2 (0.41) |

| Any serious TEAE | 4 (24.74) | 2/15.7 (12.77) | 4 (24.18) | 2/16.5 (12.10) | 6 (27.69) | 3/21.1 (14.19) | 41 (16.56) | 30/243.2 (12.33) | 15 (7.88) | 14/188.1 (7.45) | 14 (5.76) | 13/241.8 (5.38) |

| Any drug-related serious TEAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.42) | 6/246.6 (2.43) | 3 (1.58) | 3/189.8 (1.58) | 4 (1.64) | 4/242.8 (1.65) |

| Most common TEAEs by PT (≥ 5% of patients) | ||||||||||||

| Dermatitis atopic | 22 (136.06) | 17/12.7 (133.71) | 15 (90.68) | 11/14.7 (74.67) | 5 (23.07) | 4/21.1 (18.99) | 320 (129.23) | 233/202.2 (115.25) | 86 (45.16) | 71/178.9 (39.68) | 113 (46.47) | 89/228.9 (38.87) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 3 (18.55) | 3/15.6 (19.29) | 3 (18.14) | 3/16.1 (18.68) | 11 (50.76) | 7/20.3 (34.42) | 101 (40.79) | 87/233.6 (37.24) | 91 (47.79) | 76/178.3 (42.63) | 108 (44.41) | 92/228.0 (40.35) |

| Injection-site reaction | 3 (18.55) | 3/15.3 (19.58) | 0 | 0 | 19 (87.68) | 10/19.7 (50.74) | 79 (31.90) | 43/238.3 (18.04) | 145 (76.14) | 63/177.0 (35.59) | 299 (122.95) | 117/217.6 (53.77) |

| Headache | 3 (18.55) | 3/15.5 (19.33) | 1 (6.05) | 1/16.2 (6.16) | 4 (18.46) | 2/21.1 (9.49) | 66 (26.65) | 46/238.5 (19.28) | 86 (45.16) | 53/177.7 (29.83) | 105 (43.18) | 62/229.7 (26.99) |

| Conjunctivitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (32.30) | 5/20.8 (24.01) | 8 (3.23) | 8/246.3 (3.25) | 37 (19.43) | 32/185.1 (17.28) | 22 (9.05) | 22/239.7 (9.18) |

| Conjunctivitis allergic | 0a | 0 | 2 (12.09)a | 2/16.2 (12.32) | 3 (13.84)a | 3/21.2 (14.16) | 22 (8.88) | 20/243.7 (8.21) | 43 (22.58) | 35/184.7 (18.95) | 41 (16.86) | 36/237.5 (15.16) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (37.11) | 4/15.3 (26.09) | 1 (6.05) | 1/16.4 (6.09) | 4 (18.46) | 4/20.8 (19.20) | 32 (12.92) a | 27/242.2 (11.15) | 26 (13.65) a | 20/187.2 (10.69) | 46 (18.92) a | 40/236.6 (16.90) |

| Arthralgia | 5 (30.92) | 3/15.8 (18.97) | 4 (24.18) | 3/15.8 (19.01) | 1 (4.61) | 1/21.7 (4.62) | 17 (6.87) a | 16/244.4 (6.55) | 16 (8.40) a | 13/188.0 (6.92) | 9 (3.70) a | 7/242.0 (2.89) |

| Fatigue | 3 (18.55) | 3/15.5 (19.35) | 1 (6.05) | 1/16.3 (6.14) | 2 (9.23) | 2/21.5 (9.28) | 24 (9.69) a | 9/245.5 (3.67) | 19 (9.98) a | 15/186.5 (8.04) | 16 (6.58) a | 14/240.8 (5.82) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (18.55) | 3/15.8 (18.94) | 1 (6.05) | 1/16.3 (6.14) | 0 | 0 | 8 (3.23) a | 8/246.3 (3.25) | 5 (2.63) a | 4/189.5 (2.11) | 4 (1.64) a | 4/242.3 (1.65) |

| Pruritus | 7 (43.29) | 3/15.4 (19.47) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (4.85) a | 11/245.0 (4.49) | 7 (3.68) a | 4/189.6 (2.11) | 5 (2.06) a | 5/242.3 (2.06) |

| Other adverse events | ||||||||||||

| Conjunctivitis (narrow CMQ)b | 0 | 0 | 2 (12.09) | 2/16.2 (12.32) | 11 (50.76) | 9/20.2 (44.64) | 37 (14.94) | 33/241.3 (13.68) | 90 (47.26) | 76/178.0 (42.70) | 76 (31.25) | 69/232.5 (29.68) |

| Conjunctivitis (broad CMQ)c | 1 (6.18) | 1/16.0 (6.26) | 2 (12.09) | 2/16.2 (12.32) | 13 (59.99) | 11/19.9 (55.39) | 51 (20.60) | 41/239.5 (17.12) | 122 (64.06) | 99/174.0 (56.90) | 129 (53.05) | 107/225.5 (47.45) |

| Keratitis (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.61) | 1/21.5 (4.65) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.58) | 3/190.0 (1.58) | 4 (1.64) | 4/242.5 (1.65) |

| Ulcerative keratitis (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.53) | 1/190.4 (0.53) | 1 (0.41) | 1/243.0 (0.41) |

| Herpes (HLT) | 1 (6.18) | 1/16.0 (6.26) | 2 (12.09) | 2/16.3 (12.29) | 1 (4.61) | 1/21.7 (4.62) | 39 (15.75) | 34/242.2 (14.04) | 41 (21.53) | 33/183.6 (17.98) | 48 (19.74) | 39/235.8 (16.54) |

| Injection-site reaction (HLT) | 4 (24.74) | 4/15.1 (26.52) | 0 | 0 | 21 (96.91) | 11/19.6 (56.21) | 90 (36.35) | 52/236.6 (21.98) | 161 (84.54) | 73/174.9 (41.73) | 323 (132.82) | 131/214.6 (61.05) |

| Anaphylaxis reaction (SMQ)d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SAEs under SMQ “hypersensitivity” excluding atopic dermatitise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.40) | 1/247.6 (0.404) | 1 (0.53) | 1/190.1 (0.526) | 1 (0.41) | 1/242.9 (0.412) |

| Serious TEAEs occurring in > 1 patient by PT | ||||||||||||

| Dermatitis atopic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (3.63) | 8/246.2 (3.25) | 3 (1.58) | 3/190.0 (1.58) | 2 (0.82) | 2/243.0 (0.82) |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.21) | 3/247.4 (1.21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CMQ conditional medical query, HLT high-level term, nE number of events, nP number of patients with an event, PT preferred term, PY patient years, q2w every 2 weeks, qw every week, SAE serious adverse event, SMQ standardized medical query, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aTEAE was reported by < 5% of patients in this age group

bPreferred terms for “conjunctivitis” narrow CMQ: Conjunctivitis, Conjunctivitis bacterial, Conjunctivitis viral, Conjunctivitis allergic, Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

cPreferred terms for “conjunctivitis” broad CMQ: Atopic keratoconjunctivitis, Blepharitis, Conjunctivitis, Conjunctivitis allergic, Conjunctivitis bacterial, Conjunctivitis viral, Conjunctivitis hyperemia, Dry eye, Eye discharge, Eye irritation, Eye pruritus, Foreign body sensation in eyes, Lacrimation increased, Ocular hyperaemia, Photophobia, Xerophthalmia

dPreferred terms for “Anaphylaxis reaction” narrow SMQ: Anaphylactic reaction, Anaphylactic shock, Anaphylactic transfusion reaction, Anaphylactoid reaction, Anaphylactoid shock, Circulatory collapse, First use syndrome, Kounis syndrome, Shock, Type 1 hypersensitivity

ePreferred terms for “hypersensitivity excluding atopic dermatitis” SMQ: Dermatitis exfoliative, Rash maculo-papular, Urticaria

The most common TEAEs (≥ 5% incidence) in the ≥ 60 age group were AD in the placebo and q2w dupilumab groups (133.71 nP/100 PY and 74.67 nP/100 PY, respectively) and injection-site reactions in the qw dupilumab group (50.74 nP/100 PY) (Table 4). Exposure-adjusted incidence rates of common TEAEs were generally comparable across age groups, or higher in the < 60 age group, with the exceptions of AD, arthralgia, and urinary tract infection in the q2w dupilumab arm and conjunctivitis and urinary tract infection in the qw dupilumab arm, which were higher in the ≥ 60 age group. Within both age groups, patients treated with placebo experienced higher rates of AD, while dupilumab-treated patients (qw) were more likely to experience injection-site reactions (Table 4). Serious TEAEs were rare in both age groups, with no drug-related serious TEAEs reported in the ≥ 60 age group. In the < 60 age group, the only two serious TEAEs occurring were AD (placebo: 3.25 nP/100 PY; q2w: 1.58 nP/100 PY; qw: 0.82 nP/100 PY) and suicidal ideation (placebo: 1.21 nP/100 PY; q2w: 0 nP/100 PY; qw: 0 nP/100 PY). The overall safety data for these studies have been published previously [18–20].

Discussion

Dupilumab improved AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life in adults ≥ 60 years of age with moderate-to-severe AD. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in patients ≥ 60 years of age were generally consistent with those in patients < 60 years of age, who constituted most of the adult clinical study population, and therefore contributed most to the overall dupilumab efficacy and safety profile. These findings support prior studies demonstrating that dupilumab improves AD signs and symptoms; safety findings were consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile [31–33]. In both age groups, severe TEAEs and TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation were uncommon.

The complex pathophysiology of AD is influenced by genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors that lead to a dysfunctional skin barrier and polarized inflammatory response, characterized by marked type 2 inflammation. Activation of additional TH cell subsets, including TH1/TH17/TH22, was also described in AD; for example, increased TH1 cells were associated with chronic lesions in adults [7, 34]. Further research is warranted to better understand AD phenotype–endotype correlations and the clinical relevance of different immune profiles and barrier abnormalities across age groups. Despite this differential expression of other TH cell pathways, the shared molecular signature of AD across ages is TH2 skewed. Clinical severity scores significantly correlate with TH2-related markers in all age groups [6, 34]. Here, we find elevated levels of total IgE and TARC (two markers of type 2 inflammation) in adult patients with AD. However, compared with adults < 60 years of age at baseline, we find lower levels of total IgE in adults ≥ 60 years of age. This is consistent with findings from Zhou et al., 2019, who found an inverse relationship between IgE levels and age in adults [7]. Zhou et al. also found lower TARC levels in older adults compared with younger adults, whereas we found TARC levels to be comparable between age groups. In both age groups, dupilumab treatment (q2w or qw) significantly reduced levels of IgE and TARC compared with placebo. These data suggest that dupilumab reduces type 2 inflammation in adults regardless of age.

AD treatment options in older adults can be limited due to medical comorbidities, age-related changes in drug metabolism, and risks associated with polypharmacy [5]. Moreover, most AD studies and treatment guidelines typically do not include patients ≥ 60 years of age as a separate group from adults < 60 years of age [25, 26, 35]. Despite limited AD treatment guidelines for older adults, a scoping review of International Eczema Council (IEC) councilors and associates showed dupilumab was the most commonly preferred first-line systemic treatment for special patient populations, including patients over the age of 65 years [36].

Strengths of this study include the pooling of data across four clinical trials, thus allowing for assessment of dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults ≥ 60 years of age, a group that is underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments, including dupilumab. Limitations include the smaller sample size in the ≥ 60 age group compared with the < 60 age group, the lack of statistical comparisons across different age groups (statistical comparisons presented here only compare dupilumab against placebo within each age group, except for baseline TARC and IgE levels), the post hoc nature of the analyses, the fact that the study does not account for chronicity of disease within age groups, the failure to evaluate different clinical phenotypes in each age group, and the relatively short 16-week study duration. Another limitation in this study is that most patients in the ≥ 60 age group were 60–70 years of age, which limits the generalizability of these findings—future studies should explore dupilumab’s safety in patients 70 years and older. Finally, the age threshold defining older patients from younger patients is largely arbitrary, and it is not known if results would differ substantially if the threshold was moved. Sample size considerations additionally limited analyses with thresholds set higher than age 60.

Conclusions

Dupilumab, with or without TCS, improves AD signs and symptoms with an acceptable safety profile in patients ≥ 60 years of age with moderate-to-severe AD. Dupilumab efficacy and safety profiles in patients ≥ 60 years of age are also generally consistent with those in patients < 60 years of age.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the studies. Research sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Declarations

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02277743, NCT02277769, NCT02755649, and NCT02260986. The study sponsors participated in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. Medical writing and editorial assistance provided by Sandra Dedrick, Ph.D., and Juliet H.A. Bell, Ph.D., of Excerpta Medica, funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Conflict of interest

Jonathan I. Silverberg is an investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Lilly, GSK, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Realm Therapeutics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Roche; a consultant for AbbVie, Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Incyte, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Menlo Therapeutics, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Realm Therapeutics, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.; and a speaker for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Sanofi. Charles W. Lynde is an advisor, consultant, and speaker for AbbVie, Altius Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Aralez Pharmaceuticals, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Bausch Health, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Cipher Pharmaceuticals, Dermavant, Lilly, Fresenius Kabi, Galderma, GSK, Innovaderm, Intega Skin Sciences, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, La Roche-Posay, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Medexus Pharmaceuticals, Merck Group, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Pediapharm, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Roche, Sanofi, Sentrex Health Solutions, Teva, Tribute Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Valeant, and Viatris. Katrina Abuabara has received personal fees from TARGET-DERM and is an investigator for Pfizer and L’Oréal. Cataldo Patruno is an investigator, speaker, consultant, and advisory board member for AbbVie, Amgen, Lilly, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. Anna De Benedetto is a consultant for dMed and Incyte; has received grant support or clinical trial support from Dermira, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pfizer. Ryan B. Thomas, Faisal A. Khokhar, and Noah A. Levit are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Haixin Zhang was an employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and may have held stock/stock options in Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Ainara Rodríguez Marco and Gaëlle Bégo-Le-Bagousse are employees of Sanofi, and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company. Jignesh Vakil was an employee of Sanofi at the time of the study, may have held stock and/or stock options in Sanofi, and is currently an employee at Moderna.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committees and the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. The protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards/ethics committees at all centers.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their proxies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as no personal patient-related data were used.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Noah A. Levit, Ainara Rodríguez Marco, and Haixin Zhang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by medical writer Sandra Dedrick, Ph.D., of Excerpta Medica, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this article. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the indication is approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised due to update in article.

Change history

5/17/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40257-023-00784-6

References

- 1.Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan LN, Magyari A, Ye M, Al-Alusi NA, Langan SM, Margolis D, et al. The epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in older adults: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(10):e0258219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Lusignan S, Alexander H, Broderick C, Dennis J, McGovern A, Feeney C, et al. The epidemiology of eczema in children and adults in England: a population-based study using primary care data. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:471–482. doi: 10.1111/cea.13784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanei R. Atopic dermatitis in older adults: a review of treatment options. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(3):149–160. doi: 10.1007/s40266-020-00750-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renert-Yuval Y, Del Duca E, Pavel AB, Fang M, Lefferdink R, Wu J, et al. The molecular features of normal and atopic dermatitis skin in infants, children, adolescents, and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(1):148–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L, Leonard A, Pavel AB, Malik K, Raja A, Glickman J, et al. Age-specific changes in the molecular phenotype of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(1):144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bieber T, D’Erme AM, Akdis CA, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Lauener R, Schäppi G, et al. Clinical phenotypes and endophenotypes of atopic dermatitis: where are we, and where should we go? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4S):S58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura T, Wu J, Kabashima K, Guttman-Yassky E. Endophenotypic variations of atopic dermatitis by age, race, and ethnicity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):1840–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6 S):S118–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girolomoni G, de Bruin-Weller M, Aoki V, Kabashima K, Deleuran M, Puig L, et al. Nomenclature and clinical phenotypes of atopic dermatitis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:1–20. doi: 10.1177/20406223211002979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanei R, Hasegawa Y. Atopic dermatitis in older adults: a viewpoint from geriatric dermatology. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(S1):75–86. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Yasenchak J, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5147–5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323896111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, Karow M, Dore T, Pobursky K, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5153–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration. DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). Highlights of prescribing information. 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761055s014lbl.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2022.

- 17.European Medicines Agency. DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). Summary of product characteristics. https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2019/20190801145601/anx_145601_en.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr 2022.

- 18.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, Reich K, Cork MJ, Radin A, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ) Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083–1101. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Ardeleanu M, Thaçi D, Barbarot S, Bagel J, et al. Dupilumab provides important clinical benefits to patients with atopic dermatitis who do not achieve clear or almost clear skin according to the Investigator’s Global Assessment: a pooled analysis of data from two phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):80–87. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Deleuran M, Kataoka M, Chen Z, Gadkari A, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 randomized trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and LIBERTY AD SOLO 2) J Dermatol Sci. 2019;94(2):266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, Wollenberg A, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam M, Zhu JW, Maqbool T, Adam G, Tadrous M, Rochon P, et al. Inclusion of older adults in randomized clinical trials for systemic medications for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(11):1240–1245. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sreekantaswamy SA, Tully J, Edelman LS, Supiano MA, Butler D. The underrepresentation of older adults in clinical trials of Janus kinase inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;S0190–9622(22):00365–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kou K, Aihara M, Matsunaga T, Chen H, Taguri M, Morita S, et al. Association of serum interleukin-18 and other biomarkers with disease severity in adults with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304(4):305–312. doi: 10.1007/s00403-011-1198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thijs JL, de Bruin-Weller MS, Hijnen D. Current and future biomarkers in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2017;37(1):51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renert-Yuval Y, Thyssen JP, Bissonnette R, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Hijnen D, et al. Biomarkers in atopic dermatitis—a review on behalf of the International Eczema Council. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(4):1174–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Patients’ Academy for Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI). https://toolbox.eupati.eu/glossary/treatment-emergent-adverse-event. Accessed 28 Apr 2022.

- 31.Howell AN, Ghamrawi RI, Strowd LC, Feldman SR. Pharmacological management of atopic dermatitis in the elderly. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(7):761–771. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2020.1729738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patruno C, Napolitano M, Argenziano G, Peris K, Ortoncelli M, Girolomoni G, et al. Dupilumab therapy of atopic dermatitis of the elderly: a multicentre, real-life study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(4):958–964. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patruno C, Fabbrocini G, Longo G, Argenziano G, Ferrucci SM, Stingeni L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of long-term dupilumab treatment in elderly patients with atopic dermatitis: a multicenter real-life observational study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):581–586. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czarnowicki T, He H, Canter T, Han J, Lefferdink R, Erickson T, et al. Evolution of pathologic T-cell subsets in patients with atopic dermatitis from infancy to adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williamson S, Merritt J, De Benedetto A. Atopic dermatitis in the elderly: a review of clinical and pathophysiological hallmarks. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(1):47–54. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drucker AM, Lam M, Flohr C, Thyssen JP, Kabashima K, Bissonnette R, et al. Systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis in older adults and adults with comorbidities: a scoping review and International Eczema Council survey. Dermatitis. 2022;3:200–206. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.