Abstract

Introduction

Reviews of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are essential for informing ongoing research efforts of symptomatic therapies and potentially disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).

Methods

We performed a systematic review of all clinical trials conducted until September 27, 2022, by examining 3 international registries: ClinicalTrials.gov, the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials Database, and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, to identify drugs in trials in DLB.

Results

We found 25 agents in 40 trials assessing symptomatic treatments and DMTs for DLB: 7 phase 3, 31 phase 2, and 2 phase 1 trials. We found an active pipeline for drug development in DLB, with most ongoing clinical trials in phase 2. We identified a recent trend towards including participants at the prodromal stages, although more than half of active clinical trials will enroll mild to moderate dementia patients. Additionally, repurposed agents are frequently tested, representing 65% of clinical trials.

Conclusion

Current challenges in DLB clinical trials include the need for disease-specific outcome measures and biomarkers, and improving representation of global and diverse populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-023-00467-8.

Keywords: Dementia with Lewy bodies, Clinical trials, Drug development, Drug therapies

Key Summary Points

| In this review, we studied drug development in dementia with Lewy bodies by analyzing three international clinical trials registries |

| To date, 25 agents across 40 clinical trials have been investigated in dementia with Lewy bodies. More than half of the trials have been conducted in the last 10 years, with 9 remaining active |

| There is increased interest in disease-modifying therapies in dementia with Lewy bodies that currently represent 55.5% of ongoing clinical trials (5 studies) |

| Current challenges for dementia with Lewy bodies drug development include increased diagnosis at earlier stages of the disease, disease-specific outcome measures and biomarkers, augmenting global representation, and including more diverse populations |

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD). In clinical populations, DLB is diagnosed in approximately 7.5% of all patients, and accounts for 2.2–24.7% of all cases of dementia [1].

DLB is associated with higher mortality risk, poorer prognosis, greater caregiver burden, and higher healthcare costs, as well as earlier nursing home admission and higher hospitalization rates than AD [2–6]. Recent advances in the AD field with the approval of its first disease-modifying therapy (DMT) [7], have intensified the scientific community's focus on randomized clinical trials (RCT) of AD and other highly prevalent neurodegenerative diseases, such as DLB. As opposed to AD and synucleinopathies like Parkinson’s Disease (PD), therapies and scientific evidence about delaying neurodegeneration in DLB are limited [8], and there are no disease-specific treatments currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Donepezil and zonisamide are approved for DLB symptomatic therapy in Japan. The need for therapy to prevent, delay onset, slow progression, and improve symptoms in DLB is driven by the worldwide growth in the size and proportion of older people and the steep increase in DLB incidence with age [1].

Discoveries regarding DLB’s underlying disease mechanisms have led to a growing number of clinical trials targeting potentially disease-relevant processes. Likewise, in recent years, there has been an increased interest in clinical trial methodology in DLB. Several reviews have provided an overview of the current treatment strategies and have investigated DLB drug development pipeline by searching the ClinicalTrials.gov database and/or PubMed [8–11]. These studies have found a significant improvement in DLB drug development, yet highlight the call for more RCTs, optimization of diagnostic criteria, and development of disease-specific biomarkers and clinical outcome measures. The drugs identified in the DLB pipeline are often presented in terms of the symptoms treated or the mechanism of action (MoA). Another option is to present the drugs in terms of the clinical trial phase to inform the progress in the field of DLB therapeutic development. Similarly, there is little information about number of participants, treatment duration, disease stage, diagnostic groups included, global distribution, sponsorship, and use of repurposed agents.

In this review, we provide an overview and analysis of the current DLB drug development pipeline, using an adapted methodology from AD and PD fields [12, 13], and based on three international clinical trials registries, to acquire insights on the progress in the field of DLB therapeutic development.

Methods

Data Collection

Two known relevant scoping reviews on different neurodegenerative diseases published in the last two years were used as a starting point to identify the most extensive clinical trial databases and search strategies [12, 13]. For this systematic review, we used data on RCTs of drug therapies from three international registries: (1) the US National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinical research registry ClinicalTrials.gov, (2) the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT/clinicaltrialsregister.eu), and (3) the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) operated by the World Health Organization (WHO).

To generate our dataset of drug trials, the search strategy was adapted for each of the search engines using pre-defined search fields with no time restrictions. Study protocols from RCTs for DLB on phases 1–3 and funded by NIH, industry, other US Federal agencies or any other (individual, university, organizations) were included. RCTs that included other diagnostic groups in addition to DLB were also considered in this review. All non-pharmacological, observational studies, phase 4, or phase 1 in healthy subjects, were excluded from our final dataset. Two independent reviewers (C.A. and M.C.G) examined each phase of the review (screening, eligibility, and inclusion and exclusion criteria). The index date for this review was September 27, 2022. Ethics committee approval was not required for this study. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Synthesis and Analysis of the Data

If a trial was classified as phase 1/2 or phase 2/3, we included the study in the lower of the two phases in our analyses (for example, a phase 1/2 was considered phase 1). We then extracted key trial characteristics: clinical trial title, source registry, trial number, classification into symptomatic or DMT, primary outcome measure, use of biomarkers as inclusion criteria and/or outcome measures (excluding safety biomarkers), start date, study completion date, actual end date, if completed, active or ongoing (recruiting, active/not recruiting), withdrawn, not recruiting, not yet recruiting, terminated or pending status; cause of termination, duration of treatment exposure in weeks, number of subjects planned for enrollment, number of subjects enrolled if completed or terminated; additional diagnostic groups, stage of the disease, global distribution, sponsorship, whether the agent was repurposed, or used an adaptive design. To identify a MoA, the common Alzheimer's Disease Research Ontology (CADRO) classification of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, International Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias Research Portfolio (iadrp.nia.nih.gov) was used. CADRO identifies disease processes of neurodegenerative disorders, and we identified a target process of each drug. If the agent has more than one MoA, we searched the literature to identify the action of the drug currently viewed as dominant. Each trial/protocol in our dataset was first defined as symptomatic therapy or novel DMT. We arbitrarily distinguished between "symptomatic" and "DMT" drugs, considering whether the drug's purpose was improvement in cognitive, motor, sleep, or neuropsychiatric symptoms without intending to affect the biological causes of cell death. By contrast, "disease modifiers" claimed to change the biology of the disease and/or provide neuroprotection. As reported in previous scoping reviews, we divided DMTs into biologics (i.e., vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, gene therapies, among others) and small molecules (oral treatments that are < 500 Daltons in molecular weight) [12]. Disease stage classification included the following categories: prodromal, dementia stages (mild, moderate, and severe), and combination of prodromal and dementia stages. Repurposed drugs were defined when an established compound was investigated for a new therapeutic indication [14]. Approved indication was defined searching in PubMed and using FDA, and EMA databases. Global distribution was based on trials performed in North America (United States and Canada), Latin America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Middle East, and/or Oceania. Lastly, sponsor was defined in accordance to the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use E6 as “an individual, company, institution, or organization which takes responsibility for the initiation, management, and/or financing of a clinical trial” [15].

A detailed description of the methodology used in this systematic review can be found in the Supplementary material.

Results

Overview

From a total of 412 clinical trials registered as of September 27, 2022, we selected 40 clinical trials. ClinicalTrials.gov has the largest number of registered trials, where we found 154 studies for screening. On EudraCT/clinicaltrialsregister.eu, we found 33 studies for screening (18 not found on clinicaltrials.gov), and, on the ICTPR registry, we found 225 studies for screening (88 not found on ClinicalTrials.gov) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The trials investigated 25 agents: 17.5% in phase 3 (7 studies), 77.5% in phase 2 (31 studies), and 5% in phase 1 (2 studies) (Table 1). Most of the trials investigated symptomatic agents: 75% versus 25% DMTs (number of agents: 30 versus 10) (Fig. 1). More than half of these clinical trials have been completed with 9 remaining active (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

General characteristics of clinical trials in DLB as of September 27, 2022

| Clinical trial phase | Number of clinical trials | Status | Classification | Repurposed agents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | Activea | Other status | DMT | Symptomatic | |||

| Phase3 | 7 (17.5%) | 6 (86%) | 1 (14%) | 0 | 0 | 7 (100%) | 7 (100%) |

| Phase 2 | 31 (77.5%) | 15 (48.4%) | 8 (25.8%) | 8b (25.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | 23 (74.2%) | 16 (51.6%) |

| Phase 1 | 2 (5%) | 0 | 0 | 2c (100%) | 2 (100%) | 0 | 2 (100%) |

| Total | 40 | 21 (52.5%) | 9 (22.5%) | 10 (27%) | 10 (25%) | 30 (75%) | 25 (65%) |

aRecruiting, Active/not recruiting

bWithdrawn = 3, pending = 2, not recruiting = 2, terminated = 1

cNot yet recruiting = 2

Fig. 1.

Distribution of agents in clinical trials for DLB in 2022, showing agents in phases 1, 2, and 3. Agents in yellow areas are disease-modifying treatments (DMTs), agents in green areas are cognitive enhancers, agents in orange areas are treatments for neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms, agents in gray areas are treatments for sleep disturbances and REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and agents in blue areas are treatments for motor symptoms. The shape of the icon shows the status of the clinical trial, and the color of the font shows the classification of the agents in terms of the Common Alzheimer’s Disease Research Ontology (CADRO)

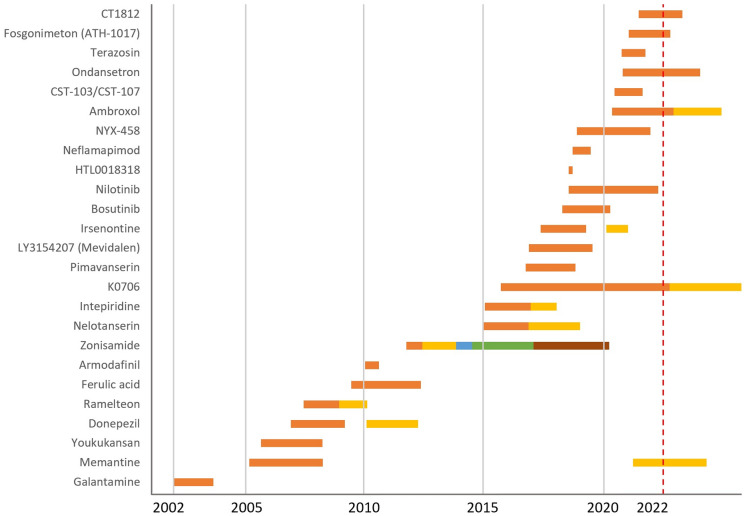

Fig. 2.

Evolution of clinical trials for DLB, showing all the agents investigated in DLB clinical trials from 2002 to 2022. Each color represents one clinical trial

The 30 clinical trials for symptomatic treatment included: 15 (50%) clinical trials for cognitive enhancers, 7 (23.3%) for neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms, 5 (16.7%) addressing motor symptoms, and 3 (10%) for sleep disturbances and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD). All DMTs were classified as small molecules.

Sixty-five percent (n = 25) of clinical trials investigated 14 repurposed agents for symptomatic or DMT: terazosin, nilotinib, bosutinib, donepezil, galantamine, memantine, ambroxol, armodafinil, ondansetron, ramelteon, pimavanserin, zonisamide, ferulic acid, and a traditional Japanese “kampo” medicine called yokukansan.

Phase 3

We found 7 phase 3 clinical trials, all of them for symptomatic treatment: 3 (43%) cognitive enhancers, 3 (43%) for neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms, and 1 (14%) for motor symptoms. According to the CADRO classification of mechanisms of action, most of the drugs in phase 3 clinical trials target neurotransmitter receptors (6 out of 7; 86%), and there was 1 (14%) multi-target agent. All the agents in this phase were repurposed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Agents in phase 3 clinical trials for dementia with Lewy bodies

| Agent | CADRO | Mechanism of action | Therapeutic purpose | Status | Registry source | Registry number | Start date | End datea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memantine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Noncompetitive, low- to medium-affinity antagonist of NMDA glutamate receptors | Symptomatic | Recruiting | ICTPR | ISRCTN79794378 | March 2022 | April 2025 |

| Zonisamide | Neurotransmitter receptors | Sulfonamide, antiseizure. Inhibitor of sodium and T-type calcium channels. Potentiates dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission | Symptomatic | Completed | ICTPR | jRCTs041180125 | October 2017 | December 2020 |

| Pimavanserin | Neurotransmitter receptors | Antagonist/inverse agonist at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors and less potent antagonist. Inverse agonist actions at 5-HT2C receptors | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and EUdraCT |

2017–002,227-13 |

September 2017 | October 2019 |

| Zonisamide | Neurotransmitter receptors | Sulfonamide, antiseizure. Inhibitor of sodium and T-type calcium channels. Potentiates dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission | Symptomatic | Completed | ICTPR | JapicCTI-152839 | April 2015 | November 2017 |

| Donepezil | Neurotransmitter receptors | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | January 2011 | March 2013 | |

| Yokukansan (traditional Japanese Kampo medicine) | Multi-target | Prevents neurotoxicity induced by amyloid-associated oxidative stress. Improves glutamate uptake and inhibits glutamate-induced neuronal death. Partial agonistic effect on serotonin 5-HT1A receptors | Symptomatic | Completed | ICTPR | UMIN000001511 | August 2006 | March 2009 |

| Galantamine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT00230997 | December 2002 | August 2004 |

aEnd date: actual end date or study completion date

In terms of disease stage, phase 3 clinical trials in DLB have included all dementia stages (mild, moderate, and severe: 4 clinical trials, 57%) and mild to moderate dementia stage (3 clinical trials, 43%).

Six of the seven clinical trials in this phase have been completed (86%), and there is one clinical trial currently recruiting (14%).

The clinical trials completed have investigated donepezil, galantamine, pimavanserin, zonisamide, and yokukansan. The clinical trial currently recruiting is investigating memantine’s effect on overall health and functioning as an add-on treatment to a cholinesterase inhibitor (ICTPR: ISRCTN79794378).

The 6 completed clinical trials enrolled a total of 970 participants (we found 1 study with unpublished results that planned to enroll 60 patients). The clinical trial currently recruiting plans to enroll 372 patients. The mean total of participants planned for enrollment in phase 3 clinical trials was 196 (range 50–372).

The mean treatment duration was 27 weeks (range 4–52): for cognitive enhancers the mean treatment exposure was 43 weeks (range 24–52), for neuropsychiatric symptoms the mean was 15 weeks (range 4–38), and the clinical trial investigating motor symptoms had 12 weeks of treatment exposure.

The clinical outcome measures used in phase 3 clinical trials were Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Cognitive Drug Research Assessment System (COGDRAS) for cognition; Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI-12) for neuropsychiatric symptoms, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study: Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGIC) for clinical global change, and Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III total score for motor symptoms.

One clinical trial included fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) as an outcome measure, and none of the phase 3 clinical trials used biomarkers as inclusion criteria (Table 3).

Table 3.

Biomarkers use in clinical trials

| Biomarkers use | Clinical trial phase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Phase 3 | Phase 2 | Phase 1 | ||

| Inclusion criteria | DaTSCAN | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| MIBG | 2 | 2 | |||

| PSG | 3 | 3 | |||

| Stratification | Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio | 1 | 1 | ||

| CSF AD biomarkers | 1 | 1 | |||

| Genetic testing for APOE | 1 | 1 | |||

| Genetic testing for GBA | 1 | 1 | |||

| Outcome measure | Plasma HVA and DOPAC | 2 | 2 | ||

| Plasma AD biomarkers | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio | 1 | 1 | |||

| Plasma α-synuclein | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Serum ATP | 1 | 1 | |||

| CSF HVA | 2 | 2 | |||

| CSF DOPAC | 1 | 1 | |||

| CSF AD biomarkers | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| CSF α-synuclein | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| CSF cGMP | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| CSF NSE, S100B, phosphorylated neurofilaments and TREM-2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Amyloid PET | 1 | 1 | |||

| EEG or qEEG | 3 | 3 | |||

| PSG or videoPSG | 2 | 2 | |||

| DaTSCAN | 2 | 2 | |||

| MIBG | 1 | 1 | |||

| FDG-PET | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MRI volumetry | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MRI spectroscopy | 1 | 1 | |||

| Digital biomarkers | 5 | 5 | |||

DaTSCAN Dopamine transporter single photon emission computerized tomography, MIBG iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy, PSG polysomnography, Aβ amyloid-β, AD Alzheimer’s disease, APOE apolipoprotein E, GBA glucosylceramidase β, HVA homovanillic acid, DOPAC 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, ATP adenosine triphosphate, cGMP cyclic guanosine monophosphate, NSE neuron-specific enolase, S100B S100 calcium-binding protein B, TREM-2 triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, EEG electroencephalogram, qEEG quantitative electroencephalogram, PET positron emission tomography, FDG-PET fluodeoxiglucose positron emission tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging

Phase 2

We found 31 phase 2 clinical trials: 23 (74.2%) symptomatic and 8 (25.8%) DMTs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Agents in phase 2 clinical trials for dementia with Lewy bodies

| Agent | CADRO | Mechanism of action | Therapeutic purpose | Status | Registry source | Registry number | Start date | End datea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT1812 | Synaptic plasticity/neuroprotection | σ-2 receptor modulator | DMT | Recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT05225415 | June 2022 | April 2024 |

| Fosgonimeton (ATH-1017) | Growth factors and hormones | Activates signaling via the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) | DMT | Recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04831281 | January 2022 | November 2023 |

| Ondansetron | Neurotransmitter receptors | Selective antagonist of serotonin 5-HT3 receptors | Symptomatic | Recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04167813 | October 2021 | January 2025 |

| CST-103, CST-107 | Neurotransmitter receptors |

CST-103: β-2 adrenoceptor agonist CST-107: β blocker with minimal brain penetration |

Symptomatic | Active, not recruiting | CT.gov, ICTPR, EudraCT |

2020–006,067-28 |

June 2021 | August 2022 |

| Ambroxol | Proteostasis/proteinopathies | Increases lysosomal fraction and the enzymatic activity of glucocerebrosidase | DMT | Recruiting | CT.gov and EUdraCT |

2019–002,855-41 |

May 2021 | December 2023 |

| Irsenontrine | Synaptic plasticity/neuroprotection | Active and selective phosphodiesterase 9 (PDE9) inhibitor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04764669 | February 2021 | January 2022 |

| Zonisamide | Neurotransmitter receptors | Sulfonamide, antiseizure. Inhibitor of sodium and T-type calcium channels. Potentiates dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission | Symptomatic | Not recruiting | ICTPR | jRCTs041190126 | February 2021 | Missing data |

| Zonisamide | Neurotransmitter receptors | Sulfonamide, antiseizure. Inhibitor of sodium and T-type calcium channels. Potentiates dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission | Symptomatic | Not recruiting | ICTPR | jRCTs051200054 | September 2020 | Missing data |

| NYX-458 | Neurotransmitter receptors | NMDAR receptor modulator that enhances synaptic plasticity | Symptomatic | Recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04148391 | November 2019 | December 2022 |

| Neflamapimod | Synaptic plasticity/neuroprotection | ATP competitive inhibitor of p38α kinase | DMT | Completed | CT.gov and EUdraCT |

2019–001,566-15 |

September 2019 | June 2020 |

| Nilotinib | Proteostasis/proteinopathies | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | DMT | Recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04002674 | July 2019 | April 2023 |

| HTL0018318 | Neurotransmitter receptors | Selective muscarinic M1 receptor partial agonist | Symptomatic | Withdrawn | CT.gov and ICTPR |

JapicCTI-183989 |

July 2019 | September 2019 |

| Bosutinib | Proteostasis/proteinopathies | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | DMT | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT03888222 | April 2019 | April 2021 |

| Irsenontrine | Synaptic plasticity/neuroprotection | Active and selective phosphodiesterase 9 (PDE9) inhibitor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov, ICTPR, EudraCT |

JapicCTI-183932 2017–003,728-64 |

May 2018 | April 2020 |

| LY3154207 (Mevidalen) | Neurotransmitter receptors | Positive allosteric modulator of the dopamine receptor D1 | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT03305809 | November 2017 | July 2020 |

| Intepirdine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Selective 5-HT6 receptor antagonist | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT02910102 | October 2016 | November 2017 |

| Vodobatinib (K0706) | Proteostasis/proteinopathies | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | DMT | Recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT03996460 | September 2016 | October 2023 |

| Galantamine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Symptomatic | Pending | ICTPR | UMIN000022860 | September 2016 | Missing data |

| Nelotanserin | Neurotransmitter receptors | Selective antagonist of the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT02708186 | March 2016 | May 2018 |

| Intepirdine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Selective 5-HT6 receptor antagonist | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov, ICTPR, EudraCT |

2015–005,495-19 |

January 2016 | December 2017 |

| Nelotanserin | Neurotransmitter receptors | Selective antagonist of the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT02640729 | December 2015 | November 2017 |

| Zonisamide | Neurotransmitter receptors | Sulfonamide, antiseizure. Inhibitor of sodium and T-type calcium channels. Potentiates dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission | Symptomatic | Completed | ICTPR | JapicCTI-122040 | March 2013 | April 2014 |

| Zonisamide | Neurotransmitter receptors | Sulfonamide, antiseizure. Inhibitor of sodium and T-type calcium channels. Potentiates dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission | Symptomatic | Completed | ICTPR | UMIN000010631 | September 2012 | May 2013 |

| Ferulic acid | Oxidative stress | Suppresses free radicals, chronic inflammation and aggregation of amyloid-β protein in the brain | Symptomatic | Completed | ICTPR | UMIN000003683 | June 2010 | May 2013 |

| Armodafinil | Unknown target | Unknown/Eugeroics: stimulants that provide long-lasting mental arousal | Symptomatic | Withdrawn | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT01256905 | January 2011 | August 2011 |

| Youkukansan | Multi-target | Prevents neurotoxicity induced by amyloid-associated oxidative stress. Improves glutamate uptake and inhibits glutamate-induced neuronal death. Partial agonistic effect on serotonin 5-HT1A receptors | Symptomatic | Missing data | ICTPR | UMIN000001832 | April 2009 | Missing data |

| Ramelteon | Neurotransmitter receptors | Agonist of MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors | Symptomatic | Withdrawn | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT00907595 | May 2009 | July 2010 |

| Ramelteon | Neurotransmitter receptors | Agonist of MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors | Symptomatic | Terminated | CT.gov | NCT00745030 | June 2008 | December 2009 |

| Donepezil | Neurotransmitter receptors | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT00543855 | November 2007 | February 2010 |

| Memantine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Antagonist of NMDA glutamate receptors | Symptomatic | Completed | EudraCT and ICTPR |

2005–004,109-27 ISRCTN89624516 |

March 2006 | September 2008 |

| Memantine | Neurotransmitter receptors | Antagonist of NMDA glutamate receptors | Symptomatic | Completed | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT00630500 | February 2006 | March 2009 |

aEnd date: actual end date or study completion date

DMT disease-modifying treatment

There were 12 (38.7%) clinical trials for cognitive enhancers, 4 (12.9%) for neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms, 4 (12.9%) for motor symptoms, and 3 (9.7%) for sleep disturbances and RBD. All DMTs investigated were small molecules.

CADRO mechanisms of both symptomatic and DMT clinical trials included neurotransmitter receptors (19; 61.3%), synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection (4; 12.9%), proteostasis and proteinopathies (4; 12.9%), multi-target (1; 3.2%), growth factor and hormones (1; 3.2%), oxidative stress (1; 3.2%), and 1 unknown target (1; 3.2%). Sixteen (51.6%) agents in phase 2 clinical trials were repurposed.

Most clinical trials included participants in mild to moderate dementia (19; 61.3%), followed by all dementia stages (6; 19.4%), prodromal and mild dementia stage (2; 6.5%), and prodromal/mild cognitive impairment stage (1; 3.2%). Three (9.7%) clinical trials did not provide this information.

Regarding clinical trial status, we found 15 (48.4%) completed, 7 (22.6%) recruiting, 3 (9.7%) withdrawn, 2 (6.5%) not recruiting, 2 (6.5%) pending status, 1 (3.2%) terminated, and 1 (3.2%) active not recruiting.

The agents investigated in the 8 active clinical trials are: CT1812 (σ-2 receptor modulator), vodobatinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor), nilotinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor), fosgonimeton (activates signaling via the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)), ambroxol (increases lysosomal fraction and the enzymatic activity of glucocerebrosidase), NYX-458 (NMDA receptor modulator), ondansetron (selective antagonist of serotonin 5-HT3 receptors), and CST-103/CST-107 (CST-103: β-2 adrenoceptor agonist/CST-107: β blocker with minimal brain penetration).

A total of 1897 participants were enrolled in completed clinical trials (one clinical trial had missing information about the number of enrolled participants; their planned enrollment was 50 participants). Three participants were enrolled in a clinical trial that was terminated due to low subject recruitment and enrollment. Clinical trials currently recruiting plan to enroll 878 participants. The mean total of participants planned for enrollment in phase 2 clinical trials was 94 (range 20–340), with a mean duration of treatment exposure of 18 weeks (1 missing value) (range 4–92 weeks). For symptomatic treatment, the mean treatment exposure was 12 weeks (range 4–24, 1 missing value) with an average of 101 participants planned for enrollment, and for DMTs exposure was 36 weeks (range 12–92) with an average of 77 participants planned for enrollment.

The clinical measures used as primary outcomes in phase 2 clinical trials for evaluating cognition were Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), MMSE, Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), Hasegawa Dementia Rating Scale, negative emotional bias in the Facial Expression Recognition Task (FERT), Trail Making Test (TMT), and the following composite scores: a study-specific neuropsychological test battery (NTB) that included assessment of attention, executive function, and visual learning; the continuity of attention (CoA) composite score of the Cognitive Drug Research Computerized Cognition Battery (CDR-CCB); and the Global Statistical Test (GTS) that combines scores from the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog13) and change in event-related potential (ERP) P300 latency. UPDRS part II, III and IV were used for motor symptoms; Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change Plus caregiver input (CIBIC-Plus), Clinical Global Impression (CGI), and ADCS-CGIC were used for identifying clinical change; Geriatric Depression Scale and NPI were used for neuropsychiatric symptoms, the Japanese version of the Zarit Burden Interview (J-ZBI) for caregiver burden; the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) for daily function, and the Dementia Cognitive Fluctuation Scale (DCFS) was used for cognitive fluctuations.

Nine phase 2 clinical trials used the following biomarkers for inclusion criteria: Dopamine Transporter Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (DaTSCAN), 123iodine-myocardial scintigraphy (MIBG), polysomnography (PSG); whereas plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) AD biomarkers, and genetic testing for Apolipoprotein E (APOE) and glucosylceramidase β (GBA) were used for stratification. Fifteen clinical trials included biomarkers as an outcome measure: plasma, CSF, amyloid PET neuroimaging, electroencephalogram (EEG), quantitative EEG (qEEG), PSG, video-PSG, MIBG, DaTSCAN, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and digital biomarkers (actigraphy, Lilly trial App, Electronic Walkway Assessment, Mini Balance Evaluation Systems Test -Mini-BESTest-, and a digital wearable device called BioStamp) (Table 3).

Phase 1

We found 2 clinical trials in phase 1 investigating small molecules for DMT, which are not yet recruiting. One is investigating a CADRO mechanism classified as metabolism and bioenergetics, and the other one is testing a drug that targets proteostasis and proteinopathies. Both agents are repurposed: terazosin (α-1 adrenergic receptor blockers) and ambroxol (increases lysosomal fraction and the enzymatic activity of glucocerebrosidase) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Agents in ongoing phase 1 clinical trials for dementia with Lewy bodies

| Agent | CADRO | Mechanism of action | Therapeutic purpose | Status | Registry source | Registry number | Start date | End datea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terazosin | Metabolism and bioenergetics | α-1 adrenergic receptor blockers | DMT | Not yet recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04760860 | October 2021 | October 2022 |

| Ambroxol | Proteostasis/proteinopathies | Increases lysosomal fraction and the enzymatic activity of glucocerebrosidase | DMT | Not yet recruiting | CT.gov and ICTPR | NCT04405596 | November 2023 | November 2025 |

aEnd date: actual end date or study completion date

DMT disease-modifying treatment

These 2 clinical trials plan to enroll a total of 55 participants in mild to moderate dementia stages, and the mean total exposure will be 34 weeks (15 and 52 weeks).

MMSE for evaluating cognition will be used as the primary outcome measure in one clinical trial. Both phase 1 clinical trials will use biomarkers as outcomes: brain ATP measured by MRI spectroscopy, FDG-PET, serum ATP levels, CSF, plasma, global and regional MRI atrophy measures. One of these clinical trials requires DaTSCAN for inclusion (Table 3).

Trials Participants

Detailed information about treatment exposure, number of subjects, and their contribution in person weeks in DLB clinical trials is presented in Supplementary Table 1. Completed clinical trials have recruited a total of 2867 participants (planned enrollment was 2539 patients). The average of DLB patients enrolled per completed clinical trials was 137 (2 clinical trials with missing data: 1 phase 2 clinical trial planned to enroll 50 participants, and 1 phase 3 clinical trial planned to enroll 60 participants). The mean duration of treatment exposure was 16 weeks (range 4–52) (Supplementary Table 1).

There are 9 (22.5%) ongoing clinical trials (8 recruiting and 1 active, not recruiting), that plan to enroll 1290 participants. Most of these trials are phase 2 (8, 88.9%).

Mild to moderate dementia was the most common disease stage of participants among all clinical trials (24; 60%), active (5; 55.6%), completed (16; 76.2%), symptomatic (16; 53.3%) and DMT (8; 80%) (Supplementary Table 2). Twenty-one (52.5%) clinical trials included DLB patients only, whereas the rest included DLB plus the following diagnostic groups: PD, PD dementia (PDD), RBD, multiple system atrophy (MSA), AD, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Huntington’s disease (HD), all causes of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (Supplementary table 3). Most of the 9 active clinical trials include DLB patients only (4; 44.4%), followed by DLB or PDD (3; 33.3%), DLB or PD (1; 11.1%) and DLB, PDD, PD associated with RBD, or mild cognitive impairment patients (1; 11.1%).

Global Distribution and Sponsorship

Most clinical trials have been conducted in 1 continent (33; 82.5%): 16 (40%) in North America, 13 (32.5%) in Asia, and 4 (10%) in Europe (Table 6). The same is true for completed and active clinical trials. Seventy-six percent (n = 16) of completed clinical trials have been conducted in 1 continent (Asia, Europe, or North America), 14.3% (n = 3) have been conducted in 2 continents (Europe and North America, or North America and Latin America), and 9.5% (n = 2) have been conducted in 3 continents (Asia, Europe, and North America; and Europe, North America, and Latin America). Active clinical trials are being conducted in 1 continent (7, 77,8%): Europe or America; or 2 continents (2, 22.2%): Europe and Oceania (Table 6). We did not find clinical trials performed in Africa or the Middle East.

Table 6.

Global distribution of clinical trials

| Number of continents | Total n (%) |

Recruitment status | Therapeutic purpose | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active n (%) |

Completed n (%) |

Othera n (%) |

Symptomatic n (%) |

DMTs n (%) |

||

| 1 continent | 33 (82.5%) | 7 (77.8%) | 16 (76.2%) | 10 (100%) | 24 (80%) | 9 (90%) |

| Asia | 13 (32.5%) | 0 | 8 (38.1%) | 5 (50%) | 12 | 1 (10%) |

| Europe | 4 (10%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 | 3 | 1 (10%) |

| North America | 16 (40%) | 5 (55.6) | 6 (28.6%) | 5 (50%) | 9 | 7 (70%) |

| 2 continents | 5 (12.5%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (14.3%) | 0 | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (10%) |

| Europe and North America | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Europe and Oceania | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| North America and Latin America | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 3 continents | 2 (5%) | 0 | 2 (9.5%) | 0 | 2 (6.7%) | 0 |

| Asia, Europe and North America | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (4.75%) | 1 (3.4%) | |||

| Europe, North America and Latin America | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (4.75%) | 1 (3.3%) | |||

aOther withdrawn: 3 phase 2, not yet recruiting: 2 phase 1, not recruiting: 2 phase 2, missing data: 2 phase 2, terminated 1 phase 2

Academic centers sponsored 52.5% (n = 21) of all clinical trials in DLB, biopharma industry sponsored 42.5% (n = 17), and public–private partnerships sponsored 5% (n = 2). Active clinical trials are being sponsored by academic centers (5; 55.6%), biopharma industry (3, 33.3%), and public private partnerships (1, 11.1%). Likewise, most clinical trials testing repurposed agents are conducted by academic centers. With regards to therapeutic purpose, half of the symptomatic treatment were sponsored by biopharma industry and most of the DMTs (7; 70%) by academic centers (Table 7).

Table 7.

Sponsorship of clinical trials

| Number of continents | Total n (%) |

Recruitment status | Therapeutic purpose | Repurposed n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active n (%) |

Completed n (%) |

Other n (%) |

Symptomatic n (%) |

DMTs n (%) |

|||

| Academic centers | 21 (52.5%) | 5 (55.6%) | 8 (38.1%) | 8 (80%) | 14 (46.7%) | 7 (70%) | 19 (76%) |

| Biopharma industry | 17 (42.5%) | 3 (33.3%) | 13 (61.9%) | 1 (10%) | 15 (50%) | 2 (20%) | 5 (20%) |

| Public–private partnership | 2 (5%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 1 (10%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

Discussion

Up to September 2022 and with no time restriction, we found just 40 clinical trials for both symptomatic and DMTs in DLB, investigating 25 agents: 7 in phase 3, 31 in phase 2, and 2 in phase 1. More than half of these clinical trials have been completed with 9 remaining active: 8 (25.8%) in phase 2 (5 small molecule DMTs and 3 symptomatic treatments), and 1 in phase 3. While the symptomatic treatments are the focus of most trials in DLB, representing all phase 3 and 74.2% of phase 2 trials, there is increasing interest in DMTs with 55.5% (n = 5) of current clinical trials testing agents of this type.

Two of the five DMTs currently under investigation in phase 2 trials are anticancer treatments that inhibit tyrosine kinases: vodobatinib (K0706) and nilotinib. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors promote autophagy of neurotoxic proteins, such as α-synuclein, amyloid-β protein, and phosphorylated tau [16]. Vodobatinib showed good tolerability with no serious adverse events in a phase 1 trial for PD [17]. Nilotinib is approved by the FDA for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, but has failed to demonstrate benefit in phase 2 trials in PD, PDD, and AD [11]. Bosutinib, another tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for chronic myeloid leukemia, was associated with less worsening in CDR-SB and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) performance in an open label study with 15 AD and 16 PDD patients after 1 year of treatment [18]. A phase 2 clinical trial was recently completed in DLB showing adequate safety and tolerability, reduction of CSF α-synuclein and dopamine catabolism, and functional improvement in activities of daily living [19].

The remaining DMTs under investigation are: CT1812, AHT-1017 (fosgonimeton), and ambroxol. CT1812 targets σ-2 receptors inhibiting α-synuclein and amyloid-β oligomers-induced toxicity, while also regulating autophagy, intracellular lipid vesicle trafficking, and cholesterol metabolism processes often impaired in synucleinopathies [11, 20]. AHT-1017 (fosgonimeton) has been tested in a phase 1 clinical trial with healthy participants and AD patients [21], with the phase 2 trial in DLB ongoing. AHT-1017 activates HGF signaling implicated in regeneration of hepatocytes in liver injury, and seems to promote angiogenesis, increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and decrease oxidative stress [22]. Finally, ambroxol, a secretolytic agent that increases glucocerebrosidase activity and lysosomal function, decreases α-synuclein levels, and improves autophagy [23], is currently being tested in both a multi-center phase 2 trial and a single-center phase 1/2 trial.

All 4 active clinical trials investigating symptomatic treatments target neurotransmitter receptors, 3 are cognitive enhancers (CST-103/CST-107, NYX-458 and memantine) and 1 targets hallucinations (ondansetron). CST-103 is a β-2 adrenoceptor agonist co-administered with CST-107, a β blocker with minimal brain penetration and intended to block peripheral side effects. NYX-458 is an NMDA receptor modulator being studied in a multi-center phase 2 clinical trial to evaluate safety and tolerability over 12 weeks of treatment. Memantine is a NMDA receptor antagonist approved for symptomatic treatment in AD that has been investigated in 2 multi-center phase 2 clinical trials. One of these studies showed greater improvement (vs. placebo) in global clinical status and neuropsychiatric symptoms in the DLB group treated with memantine for 24 weeks, while the other study found a global clinical change only in PDD but not in DLB patients after 24 weeks of treatment [24, 25]. Currently, memantine is being investigated in a multi-center phase 3 clinical trial to determine if improvement is seen after 52 weeks of treatment when used in conjunction with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Lastly, ondansetron is a selective agonist of the 5-HT3 serotonin receptor, currently being studied in a phase 2 trial of patients with DLB and PD for the treatment of hallucinations over 12 weeks.

Twenty-one (52.5%) clinical trials have been completed, mostly in phase 2 (15, 71.4%). The remaining completed clinical trials were phase 3 and, to date, only donepezil and zonisamide have received approval in Japan for treating cognition and parkinsonism in DLB, respectively.

A few limitations were evident in the landscape of clinical trials for DLB. In contrast with PD and AD where novel therapies dominate clinical trials [12, 13], most of the clinical trials in DLB investigate repurposed agents and there are very few agents in Phase 1 trials [14]. This is largely because drugs are often developed initially for AD or PD and later directed towards DLB. We found that most DLB clinical trials, and in particular the repurposing of agents, were sponsored by academic centers, likely related to complexities around IP within the biopharma industry [12, 26].

As noted in previous reviews, most of the clinical outcome measures used for primary endpoints in DLB clinical trials are not disease-specific nor validated in this population [27], with most of them designed for AD or PD. We identified four instruments for assessing clinical outcome measures specific for DLB: the Dementia Cognitive Fluctuation Scale (DCFS) evaluating cognitive fluctuations to distinguish Lewy body dementias from AD and vascular dementia [28] used in the CST-103/CST-107 trial and various composite scores used in clinical trials of neflamapimod, ATH-1017 (fosgonimeton), and mevidalen. The composite scores were different across trials and included measures designed to capture attention, executive function, and visual learning impairments specific to DLB [29, 30].

Most clinical trials identified in this review included DLB patients in mild to moderate dementia stages (24; 60%), but a recent shift towards inclusion of patients at earlier disease stages was evident, with 2 currently active trials including patients with prodromal DLB for the first time. Earlier diagnosis of DLB will allow increased representation of these patients in clinical trials to identify treatments that slow disease progression at an early stage. Advances in the recognition of RBD as a prodromal presentation of DLB (in addition to PD and MSA), as well as the recent publication of the research criteria for prodromal DLB [31], should help to improve our ability to identify prodromal DLB for trials. Biomarkers are also important in facilitating the earlier diagnosis of DLB for inclusion in clinical trials, while also improving diagnostic sensitivity and excluding participants without Lewy-type pathology.

More than half of DLB clinical trials have used biomarkers, more often for outcome measures than to support patient selection. There is growing recognition of the heterogenous neuropathological footprint in DLB, with co-pathology present in most patients, and the use of biomarkers as inclusion criteria is likely to be of increasing relevance [32]. Selection of participants based on biomarkers may be particularly beneficial for DMTs aim to target specific neuropathologies. Indeed, while many clinical trials included diagnostic groups in addition to DLB (usually PDD), reflecting the overlap of DLB symptomatology with other neurodegenerative diseases, as well as some of the challenges in accurate diagnosis of DLB [33], this was less common in DMTs, with 80% including DLB patients only.

Master protocols may be one means of improving clinical trials for patients with DLB. Master protocols are a type of clinical trial design that use a single protocol to test multiple therapies (separately or in combination), and/or multiple diseases in parallel. They are classified as basket, umbrella, and platform trials [34]. Active clinical trials plan to enroll 1290 participants and challenges in clinical trial recruitment could be overcome with the implementation of adaptive methodologies that allow pre-specified modifications to clinical trial protocols during the data collection period [35]. These modifications may include: sample size re-estimation, changes to eligibility criteria, endpoints, dosage, or patient allocation, as well as the addition or termination of treatment arms [36]. We did not identify use of master protocols or adaptive methodologies in current clinical trials in DLB. These innovative designs have been implemented in other neurodegenerative diseases like AD and PD, so lessons learned from these clinical trials could be adapted to drug development in DLB [37].

Other challenges in DLB drug development are the inclusion of more diverse populations and an increase of global representation. Only 5% of DLB clinical trials have been conducted in multiregional programs involving 3 continents: Asia, Europe, North America, and Latin America. Only 2 completed clinical trials included DLB patients in a South American site, and we did not find DLB clinical trials conducted in Africa or the Middle East. These results highlight the importance of global collaborations, data-sharing platforms, and partnerships between academic centers, patient advocacy groups, pharmaceutical companies, and government institutions as potential strategies to fill these gaps [38–40].

Conclusions

In this systematic review, we expanded the information provided by recent publications investigating drug development in DLB [8, 10, 11], using a methodology adapted from AD and PD clinical trial reviews [12, 13]. We have updated the DLB drug development pipeline, analyzed recruitment status, the disease stage and diagnostic groups included in clinical trials, number of trials participants and treatment exposure, use of repurposed agents per clinical trial phase, description of outcome measures for primary endpoints, use of biomarkers for inclusion and/or outcome measures, sponsorship, and global distribution. To this end, we used three international registries, but we acknowledge that there are additional worldwide registries. Similarly, there may be clinical trials that precede the availability of ClinicalTrials.gov, EudraCT, and ICTPR, for example, two clinical trials of Rivastigmine published in 2000 [41, 42]. Therefore, some clinical trials may have not been included in this review.

In summary, drug development in DLB presents an active pipeline. To accelerate DLB drug development there is a need for more clinical trials, increased diagnosis at earlier stages of the disease, and disease-specific outcome measures and biomarkers, as well as augmenting global representation and including more diverse populations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

This paper represents independent research partly funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. CA postdoctoral fellowship is funded by the Susan and Charles Berghoff Foundation. LLG is funded by the Alzheimer’s Society. JC is supported by NIGMS grant P20GM109025; NINDS grant U01NS093334; NIA grant R01AG053798; NIA grant P20AG068053; NIA grant P30AG072959; NIA grant R35AG71476; Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF); Ted and Maria Quirk Endowment; and the Joy Chambers-Grundy Endowment. No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this article.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Carla Abdelnour and Maria Camila Gonzalez. Analysis was performed by Carla Abdelnour. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Carla Abdelnour and Maria Camila Gonzalez, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Carla Abdelnour has received the Sue Berghoff LBD Research Fellowship, and honoraria as speaker from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Zambon, Nutricia, Schwabe Farma Ibérica S.A.U. She is member of the Board of Directors of the Lewy Body Dementia Association. Maria Camila Gonzalez has no conflicts of interest. Lucy L. Gibson has no conflicts of interest. Kathleen L. Poston has been funded by grants to conduct research from the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the Lewy Body Dementia Association, the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, the Sue Berghoff LBD Research Fellowship, and the NIH. She is on the Scientific Advisory Board for Curasen, where she receives consulting fees and stock options. She is on the Scientific Advisory Board for Amprion, where she receives stock options. Clive G. Ballard has received consulting fees from Acadia pharmaceutical company, AARP, Addex pharmaceutical company, Eli Lily, Enterin pharmaceutical company, GWPharm, H.Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, Novo Nordisk pharmaceutical company, Novartis pharmaceutical company, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson and Johnson pharmaceuticals, Orion Corp pharmaceutical company, Otsuka America Pharm Inc, Sunovion Pharm. Inc, Suven pharmaceutical company, Roche pharmaceutical company, Biogen pharmaceutical company, Synexus clinical research organization and tauX pharmaceutical company. Jeffrey L. Cummings has provided consultation to Acadia, Actinogen, Alkahest, AlphaCognition, AriBio, Biogen, BioVie, Cassava, Cerecin, Corium, Cortexyme, Diadem, EIP Pharma, Eisai, GemVax, Genentech, Green Valley, GAP Innovations, Grifols, Janssen, Karuna, Lilly, Lundbeck, LSP, Merck, NervGen, Novo Nordisk, Oligomerix, Optoceutics, Ono, Otsuka, PRODEO, Prothena, ReMYND, Resverlogix, Roche, Sage Therapeutics, Signant Health, Simcere, Sunbird Bio, Suven, TrueBinding, and Vaxxinity pharmaceutical, assessment, and investment companies. Dag Aarsland has received research support and/or honoraria from Evonik, DailyColors, Muhdo, Astra-Zeneca, H. Lundbeck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Roche Diagnostics, and GE Health, and served as paid consultant for H. Lundbeck, Eisai, Heptares, Mentis Cura, Eli Lilly, Anavex, Cognetivity, Enterin, Acadia, Sygnature, Biogen, Cognetivity, EIP Pharma, and Acadia.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Vann Jones SA, O'Brien JT. The prevalence and incidence of dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review of population and clinical studies. Psychol Med. 2014;44(4):673–683. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Ptacek S, Farahmand B, Kareholt I, Religa D, Cuadrado ML, Eriksdotter M. Mortality risk after dementia diagnosis by dementia type and underlying factors: a cohort of 15,209 patients based on the Swedish Dementia Registry. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(2):467–477. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller C, Ballard C, Corbett A, Aarsland D. The prognosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(5):390–398. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oesterhus R, Soennesyn H, Rongve A, Ballard C, Aarsland D, Vossius C. Long-term mortality in a cohort of home-dwelling elderly with mild Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38(3–4):161–169. doi: 10.1159/000358051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams MM, Xiong C, Morris JC, Galvin JE. Survival and mortality differences between dementia with Lewy bodies vs Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(11):1935–1941. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247041.63081.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller C, Perera G, Rajkumar AP, et al. Hospitalization in people with dementia with Lewy bodies: Frequency, duration, and cost implications. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabinovici GD. Controversy and progress in alzheimer's disease—FDA approval of aducanumab. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):771–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2111320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee G, Cummings J, Decourt B, Leverenz JB, Sabbagh MN. Clinical drug development for dementia with Lewy bodies: past and present. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(11):951–965. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1681398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor J-P, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, et al. New evidence on the management of Lewy body dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):157–169. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30153-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope ED, Cordes L, Shi J, Mari Z, Decourt B, Sabbagh MN. Dementia with Lewy bodies: emerging drug targets and therapeutics. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2021;30(6):603–609. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.1916913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald S, Shah AS, Tousi B. Current therapies and drug development pipeline in lewy body dementia: an update. Drugs Aging. 2022;39(7):505–522. doi: 10.1007/s40266-022-00939-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings J, Lee G, Nahed P, et al. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12295. 10.1002/trc2.12295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.McFarthing K, Rafaloff G, Baptista M, et al. Parkinson's disease drug therapies in the clinical trial pipeline: 2022 update. J Parkinsons Dis. 2022;12(4):1073–1082. doi: 10.3233/JPD-229002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien JT, Chouliaras L, Sultana J, et al. RENEWAL: REpurposing study to find NEW compounds with Activity for Lewy body dementia—an international Delphi consensus. Alzheimer's Res Therapy. 2022;14(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01103-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. Accessed February 18, 2023. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/E6_R2_Addendum.pdf

- 16.Fagiani F, Lanni C, Racchi M, Govoni S. Targeting dementias through cancer kinases inhibition. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020;6(1):e12044. 10.1002/trc2.12044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Goldfine A, Faulkner R, Sadashivam V, et al. Results of a Phase 1 Dose-Ranging Trial, and Design of a Phase 2 Trial, of K0706, a Novel C-Abl Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurology. 2019;92(15 Supplement):P2.8–047.

- 18.Mahdavi KD, Jordan SE, Barrows HR, et al. Treatment of dementia with bosutinib: an open-label study of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(3):e294–e302. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagan FL, Torres-Yaghi Y, Hebron ML, et al. Safety, target engagement, and biomarker effects of bosutinib in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12296. 10.1002/trc2.12296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Limegrover CS, Yurko R, Izzo NJ, et al. Sigma-2 receptor antagonists rescue neuronal dysfunction induced by Parkinson's patient brain-derived alpha-synuclein. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(4):1161–1176. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moebius H, Hua X, Church K, et al. Phase 1 study of NDX-1017: safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers and dementia patients. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019;6(S22)

- 22.Takeuchi D, Sato N, Shimamura M, et al. Alleviation of Abeta-induced cognitive impairment by ultrasound-mediated gene transfer of HGF in a mouse model. Gene Ther. 2008;15(8):561–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balestrino R, Schapira AHV. Glucocerebrosidase and Parkinson disease: molecular, clinical, and therapeutic implications. Neuroscientist. 2018;24(5):540–559. doi: 10.1177/1073858417748875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z, et al. Memantine in patients with Parkinson's disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):613–618. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emre M, Tsolaki M, Bonuccelli U, et al. Memantine for patients with Parkinson's disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(10):969–977. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(10)70194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummings J, Bauzon J, Lee G. Who funds Alzheimer's disease drug development? Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2021;7(1):e12185. 10.1002/trc2.12185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Rodriguez-Porcel F, Wyman-Chick KA, Abdelnour Ruiz C, et al. Clinical outcome measures in dementia with Lewy bodies trials: critique and recommendations. Transl Neurodegener. 2022;11(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s40035-022-00299-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DR, McKeith I, Mosimann U, et al. The dementia cognitive fluctuation scale, a new psychometric test for clinicians to identify cognitive fluctuations in people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(9):926–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang Y, Alam JJ, Gomperts SN, et al. Preclinical and randomized clinical evaluation of the p38α kinase inhibitor neflamapimod for basal forebrain cholinergic degeneration. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1)10.1038/s41467-022-32944-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Biglan K, Munsie L, Svensson KA, et al. Safety and efficacy of mevidalen in lewy body dementia: a phase 2, randomized. Placebo-Controlled Trial Mov Disord. 2022;37(3):513–524. doi: 10.1002/mds.28879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKeith IG, Ferman TJ, Thomas AJ, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2020;94(17):743–755. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toledo JB, Abdelnour C, Weil RS, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies: impact of co-pathologies and implications for clinical trial design. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 doi: 10.1002/alz.12814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas AJ, Mahin-Babaei F, Saidi M, et al. Improving the identification of dementia with Lewy bodies in the context of an Alzheimer's-type dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0356-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu CC, Li XN, Broglio K, et al. Practical considerations and recommendations for master protocol framework: basket, umbrella and platform trials. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2021;55(6):1145–1154. doi: 10.1007/s43441-021-00315-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorlund K, Haggstrom J, Park JJ, Mills EJ. Key design considerations for adaptive clinical trials: a primer for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;360:k698. 10.1136/bmj.k698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials of Drugs and Biologics. Guidance for industry (Food and Drug Administration) (2019).

- 37.Cummings J, Montes A, Kamboj S, Cacho JF. The role of basket trials in drug development for neurodegenerative disorders. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D'Antonio F, Kane JPM, Ibanez A, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies research consortia: A global perspective from the ISTAART Lewy Body Dementias Professional Interest Area working group. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2021;13(1):e12235. 10.1002/dad2.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Goldman JG, Forsberg LK, Boeve BF, et al. Challenges and opportunities for improving the landscape for Lewy body dementia clinical trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00703-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peterson B, Armstrong M, Galasko D, et al. Lewy body Dementia association's research centers of excellence program: inaugural meeting proceedings. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKeith IG, Grace JB, Walker Z, et al. Rivastigmine in the treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies: preliminary findings from an open trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(5):387–392. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200005)15:5<387::Aid-gps131>3.0.Co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. The Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2031–2036. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.