Abstract

The Escherichia coli tauABCD and ssuEADCB gene clusters are required for the utilization of taurine and alkanesulfonates as sulfur sources and are expressed only under conditions of sulfate or cysteine starvation. tauD and ssuD encode an α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase and a reduced flavin mononucleotide-dependent alkanesulfonate monooxygenase, respectively. These enzymes are responsible for the desulfonation of taurine and alkanesulfonates. The amino acid sequences of SsuABC and TauABC exhibit similarity to those of components of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily, suggesting that two uptake systems for alkanesulfonates are present in E. coli. Chromosomally located in-frame deletions of the tauABC and ssuABC genes were constructed in E. coli strain EC1250, and the growth properties of the mutants were studied to investigate the requirement for the TauABC and SsuABC proteins for growth on alkanesulfonates as sulfur sources. Complementation analysis of in-frame deletion mutants confirmed that the growth phenotypes obtained were the result of the in-frame deletions constructed. The range of substrates transported by these two uptake systems was largely reflected in the substrate specificities of the TauD and SsuD desulfonation systems. However, certain known substrates of TauD were transported exclusively by the SsuABC system. Mutants in which only formation of hybrid transporters was possible were unable to grow with sulfonates, indicating that the individual components of the two transport systems were not functionally exchangeable. The TauABCD and SsuEADCB systems involved in alkanesulfonate uptake and desulfonation thus are complementary to each other at the levels of both transport and desulfonation.

In Escherichia coli, sulfate starvation causes increased synthesis of several proteins involved in scavenging sulfur from alternative sulfur sources (15). Recently, two sets of genes whose expression is derepressed in the absence of sulfate or cysteine were identified. The tauABCD gene cluster, located at 8.5 min on the E. coli chromosome, encodes a sulfonate-sulfur utilization system that is specifically involved in the utilization of taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) as a source of sulfur. Disruption of tauB, tauC, or tauD resulted in the loss of the ability to utilize taurine as a source of sulfur but did not affect the utilization of a range of other aliphatic sulfonates (21). The TauD protein is an α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase (3), and the TauABC proteins exhibit similarity to ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type transport systems (21). A second set of genes, the ssuEADCB gene cluster, located at 21.4 min on the chromosome, enables E. coli to utilize aliphatic sulfonates other than taurine as a source of sulfur. Deletion of ssuEADCB caused an inability to utilize alkanesulfonates but did not affect the utilization of taurine (24). SsuD is a monooxygenase that catalyzes the desulfonation of a wide range of sulfonated substrates other than taurine, including C2 to C10 unsubstituted linear alkanesulfonates, substituted ethanesulfonic acids and the buffer substances HEPES, MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid), and PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)]. This monooxygenase is dependent on reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMN) which is provided by the SsuE protein, an NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductase (4). The SsuABC proteins also appear to constitute an ABC transport system (24). Neither the TauD enzyme nor the two-component SsuD-SsuE monooxygenase desulfonated methanesulfonic acid, cysteic acid, or aromatic sulfonates (4), compounds that are unable to satisfy the sulfur requirement of E. coli EC1250. These two enzyme systems thus cover the full range of desulfonation activities in this E. coli strain. They convert alkanesulfonates to the corresponding aldehyde and sulfite, which has been shown to enter the sulfite reduction pathway to cysteine (20).

In the present study we investigated the role of the tauABC and ssuABC genes in the utilization of taurine and alkanesulfonates as sulfur sources. The tauA and ssuA genes encode putative signal sequences, indicating that their products probably function as periplasmic binding proteins. The sequences of TauB and SsuB and of TauC and SsuC are significantly similar to those of ATP-binding proteins and integral membrane components, respectively, of members of the ABC transporter superfamily (6). By analogy to known binding-protein-dependent ABC transporters (2), it is inferred that these systems are composed of a homodimeric membrane protein and a homodimeric ATP-binding protein. A pairwise comparison of the components of the TauABC and SsuABC transporters revealed sequence identities of 22.7% for TauA and SsuA, 40.4% for TauB and SsuB, and 34.5% for TauC and SsuC. Using a genetic approach, we explored to what extent the substrate specificity of the TauD and SsuD-SsuE desulfonation systems is reflected in the substrate range of the corresponding transport systems and whether components of the two transport systems are functionally exchangeable.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

All chemicals used as sulfur sources were of the highest quality available and were obtained from Fluka, except N-phenyltaurine and 4-phenyl-1-butanesulfonate (Sigma), isethionic acid (Aldrich), and 3-aminopropanesulfonate (Acros Organics). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland). Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, and Taq DNA polymerase were obtained from MBI Fermentas. Pfu DNA polymerase was from Promega.

E. coli strains and growth conditions.

E. coli strain DH5α (16), used for cloning purposes, was grown with constant shaking (180 rpm) at 37 or 30°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (16). Solid media were prepared by addition of 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. When appropriate, the following additions were made: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 35 μg/ml; isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 0.5 mM; 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl galactoside (X-Gal), 80 μg/ml; and sucrose, 5% (wt/vol). For plasmid isolation, restriction enzyme digestion, and transformation of E. coli, standard procedures were used (1). DNA for sequencing was prepared using either the QiaSpin Miniprep kit from Qiagen or the Jetstar Midiprep kit from Genomed.

E. coli EC1250 (MC4100 trp-1) (7) and the corresponding deletion mutants of this strain were grown at 37°C in a sulfur-free M63 medium (21) supplemented with 4 μg of tryptophan per ml and the desired sulfur source at 250 μM. Growth curves were determined in microtiter plates with 150 μl of culture by using a SPECTRAmax Plus microtiter plate reader with SOFTmax PRO software (Molecular Devices). Overnight cultures grown in sulfur-free M63 minimal medium supplemented with sulfate as a sulfur source were diluted 100-fold in sulfur-free M63 minimal medium, and then 75-μl portions of the diluted overnight cultures were pipetted into the wells of a microtiter plate containing 75 μl of minimal medium supplemented with the appropriate sulfur source at a concentration of 500 μM. The optical density at 600 nm was measured every 5 min. The plate was shaken for 30 s before every measurement to ensure aerobic growth conditions.

Construction of chromosomal in-frame deletion mutants.

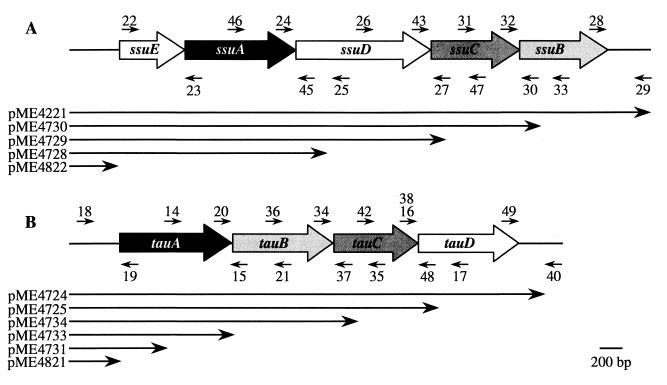

The DNA (at least 500 bp) flanking the gene or group of genes to be deleted was amplified using Pfu DNA polymerase. Oligonucleotide primers were designed to introduce adequate restriction sites for subsequent cloning purposes (Table 1). Their approximate locations in the tau and ssu operons are shown in Fig. 1. Identical restriction sites were introduced at the 5′ end (around 20 bp downstream of the start codon) and at the 3′ end (30 to 40 bp before the stop codon) of the gene or group of genes to be deleted. The external primers used for PCR of the flanking regions introduced restriction sites available in plasmid pBluescript II KS (Stratagene). After digestion with the appropriate restriction enzymes, both PCR products were ligated together into pBluescript. The inserts of the resulting plasmids were sequenced to confirm that in-frame ligation had occurred and that no changes in the DNA sequence were introduced during PCR. Subsequently the deletion inserts were subcloned in plasmid pKO3 (10). All plasmids used for the construction of chromosomal E. coli EC1250 in-frame deletion mutations of tau and ssu genes are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for the construction of tau and ssu deletions

| Primer | Sequencea | Nucleotide positionb | Deletion(s) constructed |

|---|---|---|---|

| EE14 | 5′-GCAAGTGGAGATCTTGAACCT-3′ | 11337–11357 | tauB, tauBC |

| EE15 | 5′-ATCGGCGTAAGCTTGAGAGAT-3′ | 11895–11875 | tauB, tauBC |

| EE16 | 5′-GGTCTGCAAGCTTTACAGCGC-3′ | 13404–13424 | tauC, tauBC |

| EE17 | 5′-TCGCGCCAGCGTCGACGTTCCT-3′ | 13980–13959 | tauC, tauBC, tauABC |

| EE18 | 5′-AGAGACGTAAGATCTGGCGC-3′ | 10318–10337 | tauA, tauAB, tauABC |

| EE19 | 5′-CGGCAAGAAGCTTGTTACGCG-3′ | 10924–10904 | tauA, tauAB, tauABC |

| EE20 | 5′-TGTAGCGAAGCTTTACAGCCA-3′ | 11805–11825 | tauA |

| EE21 | 5′-AACGGTTCGTCGACTAATAAC-3′ | 12332–12312 | tauA |

| EE22 | 5′-TCGCTCCAGATCTTTGCTGGA-3′ | 250–270 | ssuA |

| EE23 | 5′-CCAGCGCAAGCTTAATGATGT-3′ | 804–784 | ssuA |

| EE24 | 5′-CATCTGGAAGCTTACTCAACTG-3′ | 1697–1718 | ssuA |

| EE25 | 5′-AGGTGAGGTCGACATCAACCTG-3′ | 2321–2300 | ssuA |

| EE26 | 5′-AAAGAGAAGATCTAACAAGTGC-3′ | 2345–2366 | ssuC, ssuCB |

| EE27 | 5′-ATAACCAAGCTTTCACTGGCG-3′ | 2916–2896 | ssuC, ssuCB |

| EE28 | 5′-ACGTGGTGAAGCTTAAACTCG-3′ | 4405–4425 | ssuB, ssuCB |

| EE29c | 5′-CTGCGTTGTCGACGAAGCAAAC-3′ | 2111–2124 | ssuB, ssuCB |

| EE30 | 5′-AGACGAGAAGCTTTCATACCG-3′ | 3693–3673 | ssuB |

| EE31 | 5′-TGGCAGCATCTGCAGATCAGC-3′ | 3063–3083 | ssuB |

| EE32 | 5′-CTGGAACCAAGCTTATCATTTG-3′ | 3641–3662 | ssuC |

| EE33 | 5′-CATCTCGAGTCGACTTAAGGC-3′ | 4189–4169 | ssuC |

| EE34 | 5′-CATGCGCGAAGCTTTTTTAAG-3′ | 12579–12599 | tauB, tauAB |

| EE35 | 5′-CGAACCTGGTCGACGCTTTTC-3′ | 13144–13124 | tauB, tauAB |

| EE36 | 5′-AAGGGCTACTGCAGTGGCGC-3′ | 12101–12120 | tauC |

| EE37 | 5′-CGGCCAGCAAGCTTTCAGCC-3′ | 12686–12667 | tauC |

| EE38 | 5′-CGCGTTAAAGCTTCGCCTGACG-3′ | 13412–13433 | tauABC |

| EE40 | 5′-AAGATACGTCGACTATGTCG-3′ | 14833–14814 | tauD |

| EE42 | 5′-ACTTAGCCCTGCAGTACGCG-3′ | 12947–12966 | tauD |

| EE43 | 5′-GGTGGCGAAAGCTTTTATCCC-3′ | 2836–2856 | ssuD |

| EE45 | 5′-TGCCCGTAAGCTTGGGTCGG-3′ | 1779–1760 | ssuD |

| EE46 | 5′-GTTGCCCTGCAGAAAGGTTCC-3′ | 1170–1190 | ssuD |

| EE47 | 5′-CGCCATCTCGAGCAACCCGC-3′ | 3362–3343 | ssuD |

| EE48 | 5′-AGCGGGGGAATTCTCAGACG-3′ | 13482–13463 | tauD |

| EE49 | 5′-GACGGAGAATTCATCGGGCG-3′ | 14247–14266 | tauD |

The boldface indicates changes from the template DNA for the introduction of restriction sites.

The position of the primers designed for tau deletions are indicated with reference to the tau operon sequence (GenBank/EBI Data Bank accession number D85613); the positions of the primers used for ssu deletions (EE29 excepted) are indicated with reference to the sequence of the ssu operon (GenBank/EBI Data Bank accession number AJ237695).

Primer EE29 is complementary to the E. coli pepN sequence (GenBank/EBI Data Bank accession number M15676) over the nucleotide range indicated.

FIG. 1.

Organization of the ssuEADCB (A) and tauABCD (B) operons, showing the approximate positions of the oligonucleotide primers used for the construction of in-frame deletion inserts and the plasmids used for complementation analysis of deletion mutants.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant feature(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pUC19 | Cloning vector, Apr | 26 |

| pBluescript II KS | Cloning vector, Apr | Stratagene |

| pET-24a(+) | Cloning vector, Kanr | Novagen |

| pKO3 | repA(Ts), Cmr, sacB+ | 10 |

| pUC18ALA4 | 7.5-kb EcoRI fragment containing tauABCD in EcoRI of pUC18 | 14 |

| pME4221 | 5.6-kb EcoRI fragment containing ssuEADCB in EcoRI of pUC19 | 24 |

| pME4700 | BglII-HindIII + HindIII-SalI PCR products for tauBC deletion in BamHI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4701 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4700 for tauBC deletion | This study |

| pME4702 | BglII-HindIII + HindIII-SalI PCR products for tauA deletion in BamHI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4703 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4702 for tauA deletion | This study |

| pME4704 | BglII-HindIII + HindIII-SalI PCR products for ssuA deletion in BamHI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4705 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4704 for ssuA deletion | This study |

| pME4706 | BglII-HindIII + HindIII-SalI PCR products for ssuCB deletion in BamHI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4707 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4706 for ssuCB deletion | This study |

| pME4708 | SalI-HindIII + HindIII-PstI PCR products for ssuB deletion in SalI/PstI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4709 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4708 for ssuB deletion | This study |

| pME4710 | BglII-HindIII + HindIII-SalI PCR products for ssuC deletion in BamHI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4711 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4710 for ssuC deletion | This study |

| pME4712 | SalI-HindIII + HindIII-PstI PCR products for tauC deletion in SalI/PstI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4713 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4712 for tauC deletion | This study |

| pME4714 | BglII-HindIII + HindIII-SalI PCR products for tauB deletion in BamHI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4715 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4714 for tauB deletion | This study |

| pME4716 | XbaI-HindIII insert from pME4702 + HindIII-SalI PCR product for tauABC deletion in XbaI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4717 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4716 for tauABC deletion | This study |

| pME4718 | XbaI-HindIII insert from pME4702 + HindIII-SalI insert from pME4714 for tauAB deletion in XbaI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4719 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4718 for tauAB deletion | This study |

| pME4720 | PstI-EcoRI + EcoRI-HindIII PCR products for tauD deletion in PstI/HindIII pBluescript | This study |

| pME4721 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4720 for tauD deletion | This study |

| pME4722 | PstI-HindIII + HindIII-XhoI PCR products for ssuD deletion in PstI/XhoI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4723 | pKO3 with NotI-SalI insert from pME4722 for ssuD deletion | This study |

| pME4724 | NdeI-HindIII tauABCD insert from pUC18ALA4 in NdeI/HindIII pUC19 | This study |

| pME4725 | NdeI-SphI tauABC insert from pUC18ALA4 in NdeI/SphI pUC19 | This study |

| pME4726 | NdeI-BamHI tauAB insert from pME4724 in NdeI/BamHI pUC19 | This study |

| pME4727 | EcoRV-HindIII (blunt) deletion in pME4724 | This study |

| pME4728 | EcoRI-ClaI ssuEA insert from pME4221 in EcoRI/ClaI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4729 | EcoRI-SalI ssuEAD insert from pME4221 in EcoRI/SalI pBluescript | This study |

| pME4730 | StuI-SmaI deletion in pME4221 | This study |

| pME4731 | HincII deletion in pME4724 | This study |

| pME4732 | NdeI-HindIII tauABCD insert from pME4724 in NdeI/HindIII pET-24a(+) | This study |

| pME4733 | NdeI-EcoRV tauA insert from pME4724 in NdeI/HindIII (blunt) pET-24a(+) | This study |

| pME4734 | BamHI (blunt)-HindIII (blunt) deletion in pME4732 | This study |

| pME4821 | 450-bp BamHI-EcoRI tau promoter region from pUC18ALA4 in BamHI/EcoRI pUC19 | This study |

| pME4822 | 340-bp BamHI-EcoRI ssu promoter region from pME4204 in BamHI/EcoRI pUC19 | This study |

In-frame deletion mutants of E. coli EC1250 were constructed as described by Link et al. (10) with some modifications. E. coli EC1250 was first transformed with a pKO3 derivative by using heat shock or electroporation (1). Transformants were selected at 30°C on LB plates containing chloramphenicol. On the second day, five to seven chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were resuspended in 0.5 ml of LB medium and diluted 102-, 103-, and 104-fold. A portion (300 to 500 μl) of each dilution was plated onto prewarmed LB-chloramphenicol plates and incubated at 43°C overnight. On the third day, five to seven chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were resuspended and diluted as described above, plated on LB-sucrose plates, and incubated at 30°C overnight. On the fourth day, 100 to 500 colonies from the LB-sucrose plates were picked on LB-sucrose and LB-sucrose-chloramphenicol plates and incubated at 30°C overnight. When possible, an additional screening on sulfur-free M63 minimal medium plates was done to find out which of the positive colonies (sucrose resistant and chloramphenicol sensitive) were unable to grow with taurine or butanesulfonate as a sulfur source and thus were likely to carry the desired deletion. Putative deletion mutants were analyzed using colony PCR with Taq DNA polymerase. A single colony was resuspended into 20 μl of sterile deionized water, from which 1 μl was added to a 50-μl PCR mixture (1). The sequence of interest was amplified using the external primers used for the construction of the deletion; PCR products were analyzed on 0.8% TAE-agarose gels. Positive clones were purified on LB plates at least three times, checking each time for the presence of the desired in-frame deletion by colony PCR.

For the construction of multiple EC1250 deletion mutants, a deletion mutant was subjected to another round of deletion as described above. Overall, the frequency of in-frame deletions obtained in successful experiments amounted to 1.4% of the putatively positive clones that were screened.

Construction of tauD and ssuD tauD mutants.

Since efforts to obtain an in-frame deletion of tauD remained unsuccessful, a tauD mutant of E. coli EC1250 was constructed by P1 transduction (11). The tauD::lacZ fusion of the E. coli MC4100 derivative MW108 [Φ(tauD::lacZ)(λplacMu9)] (21) was transduced into E. coli EC1250. Kanamycin-resistant transductants were screened for inability to grow on M63 minimal medium with taurine as a sulfur source and for the formation of blue colonies on M63 minimal medium supplemented with glutathione as a sulfur source and X-Gal to confirm the presence of the lacZ fusion. To obtain an ssuD tauD double mutant, an EC1250 mutant with ssuD deleted was used as a recipient.

Complementation analysis of in-frame deletion mutants.

Restriction sites which are unique within the tauABCD and ssuEADCB operons were used to construct the plasmids shown in Fig. 1 and listed in Table 2. Plasmids for the complementation analysis of tau deletions were constructed in pUC19 (26), starting from plasmid pUC18ALA4 (14). Plasmids required for the complementation analysis of ssu deletions were constructed in pBluescript II KS, starting with plasmid pME4221, which carries the entire ssu operon on a 5.6-kb EcoRI fragment (24). Growth of deletion mutants transformed with the appropriate plasmid was measured in 5 ml of sulfur-free M63 minimal medium supplemented with taurine or butanesulfonate as a source of sulfur. Cultures were incubated at 37°C overnight, and the optical density at 600 nm was recorded on the following day. Alternatively, when growth of strains was investigated over a longer period of time, single colonies of the deletion mutant as well as of the strain transformed with the appropriate plasmid were resuspended in 50 μl of sulfur-free M63 minimal medium, from which 20 μl was spotted on an M63 minimal medium plate containing taurine or butanesulfonate as a sulfur source. Sulfur-limited solid media were prepared by the addition of 1.5 to 2% SeaPlaque agarose (FMC BioProducts).

Two plasmids that contain the ssu and tau regulatory sequences located upstream of the ssu and tau operons were constructed (21, 24). A 340-bp BamHI-EcoRI fragment from plasmid pME4204 (24) containing the ssu regulatory elements was ligated into pUC19, leading to plasmid pME4822. For the construction of plasmid pME4821, which carries the tau regulatory sequences, a 450-bp BamHI-EcoRI fragment was PCR amplified from plasmid pUC18ALA4 (14) using primers JP7 and JP8 (21) and finally subcloned into pUC19.

RESULTS

Construction of in-frame deletions in the tau and ssu operons.

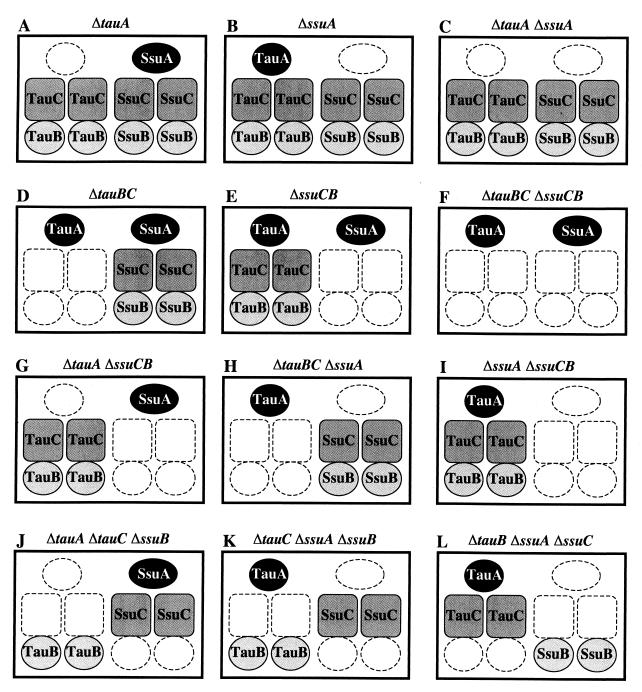

Figure 2 shows the functional transport components in deletion mutants that were constructed to probe for the requirement for the TauABC and SsuABC proteins for growth on alkanesulfonate compounds. A first group of mutants lacked one of the putative periplasmic binding proteins (Fig. 2A and B) or the membrane-associated components TauBC or SsuCB (Fig. 2D and E). A second group included constructs that were defective in the corresponding components of both transport systems at the same time. A mutant devoid of both periplasmic binding proteins (Fig. 2C) allowed exploration of whether or not certain alkanesulfonates can enter the cell in the absence of the periplasmic components. Similarly, a mutant lacking the membrane-associated components of both systems (Fig. 2F) was expected to be defective in the uptake of all sulfonate sulfur sources transported via the TauABC and SsuABC systems. A third group of mutants carried various combinations of deletions that abolished the function of a periplasmic component, an integral membrane component, and an ATP-binding protein of either transport system. Six out of the eight possible combinations of multiple deletion mutants were obtained (Fig. 2G to L), and the growth properties of these mutants were expected to provide information on the exchangeability of components between the TauABC and SsuABC transport systems. Attempts to obtain the multiple deletion ΔtauABC and ΔssuA ΔssuB ΔtauC strains by using the chromosomal mutagenesis system described by Link et al. (10) were unsuccessful, and their construction was not pursued further.

FIG. 2.

Active components of the TauABC and SsuABC transport systems in the deletion mutants.

In addition to mutants with components of the TauABC and SsuABC transport systems deleted, strains lacking either the SsuD or TauD desulfonation enzyme were constructed. These mutants served to correlate growth with a particular alkanesulfonate as a sulfur source with the presence of either one of these enzymes and to verify whether the range of alkanesulfonates utilized corresponded to the previously established substrate range of the purified enzymes (3, 4).

An ssuD tauD double mutant was important for establishing the amount of background growth in growth experiments. Since this strain lacked both α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase and alkanesulfonate monooxygenase, growth of this mutant on medium containing a particular alkanesulfonate as the only sulfur source was considered to be due to nonsulfonate sulfur contaminants present in the alkanesulfonate preparation used.

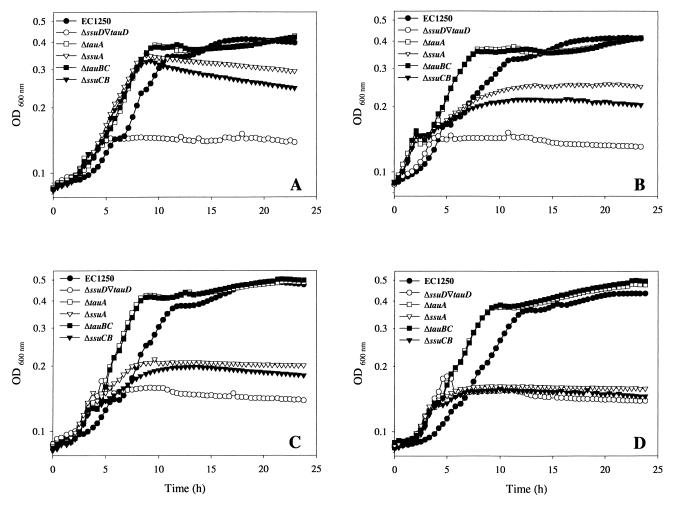

Growth of wild-type and deletion strains with alkanesulfonates as sulfur sources.

Growth was tested in a medium containing one of the following sulfonates as the only sulfur source: taurine, isethionate (2-hydroxyethanesulfonic acid), 3-aminopropanesulfonate, HEPES, MOPS, PIPES, 2-(4-pyridyl)ethanesulfonate, N-phenyltaurine, 1,3-dioxo-2-isoindoline-ethanesulfonate, 4-phenyl-1-butanesulfonate, sulfoacetate, ethanesulfonate, propanesulfonate, butanesulfonate, pentanesulfonate, hexanesulfonate, octanesulfonate, decanesulfonate, and dodecanesulfonate. All of these compounds have been shown to be substrates for the TauD and/or the SsuD enzyme (3, 4). The qualitative assessment of growth with each of the 19 sulfonates tested was based on a comparison of the growth characteristics of each mutant with growth of the wild type. The wild type defined the upper level of growth, while the ssuD tauD double mutant served as a reference for zero growth with a particular sulfonate sulfur source. Growth of the deletion mutants on different sulfur sources was graded as described in Table 3, footnote a. The growth curves of the ΔssuA and the ΔssuCB mutants shown in Fig. 3 illustrate the four arbitrarily established growth categories. From Fig. 3 it is also evident that growth with sulfonate sulfur sources was diauxic, with a first, minor growth phase presumably supported by contaminating sulfate and a second, longer growth phase reflecting sulfonate utilization. Diauxic growth was not observed when strains were cultured with sulfate as a source of sulfur. Furthermore, mutants in which transporter genes were deleted grew faster than the wild-type strain on either sulfate or sulfonates as a sulfur source. However, depending on the sulfonate sulfur source tested, fluctuations in the growth rate and length of the lag phase were noted. Since strains lacking TauD or SsuD grew like the wild type, we presume that these phenomena have their origin at the level of the transport of alkanesulfonates.

TABLE 3.

Growth phenotypes of mutants with deletions in the ssuABC and tauABC genes

| Sulfur source | Growtha of mutant with the following deletion:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | tauA | tauBC | ssuA | ssuCB | ssuABC | ssuA tauA | ssuCB tauBC | ssuA tauBC | ssuCB tauA | ssuAC tauB | ssuAB tauC | ssuB tauAC | |

| Sulfate | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Taurine | +++ | − | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PIPES | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOPS | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HEPES | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4-Phenyl-1-butanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2-(4-Pyridyl)ethanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Isethionate | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1,3-Dioxo-2-isoindolineethanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3-Aminopropanesulfonate | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Ethanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Propanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Butanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Pentanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hexanesulfonate | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Octanesulfonate | +++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Decanesulfonate | +++ | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| N-Phenyltaurine | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Sulfoacetate | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Net growth relative to the net growth yield of the wild-type strain, which was set at 100%; −, <5%; +, 5 to 33%; ++, 33 to 66%; +++, >66%. Growth was evaluated in at least three independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

Growth of E. coli EC1250 and deletion mutants. Cells were grown in a microtiter plate as described in Materials and Methods (150-μl cultures). The optical density at 600 nm (OD600 nm) was recorded with a microtiter plate reader every 5 min over 24 h. Every fifth measurement is shown. Only the growth profiles obtained with mutants grown on 1,3-dioxo-2-isoindolineethanesulfonate (A), butanesulfonate (B), PIPES (C), and MOPS (D) are shown. The optical densities obtained ranged from 0.25 to 0.5 and corresponded to optical densities of 1.0 to 2.0 when measured with a 1-cm light path in a Uvikon P-810 spectrophotometer.

Specificity of the TauABC and SsuABC transporters.

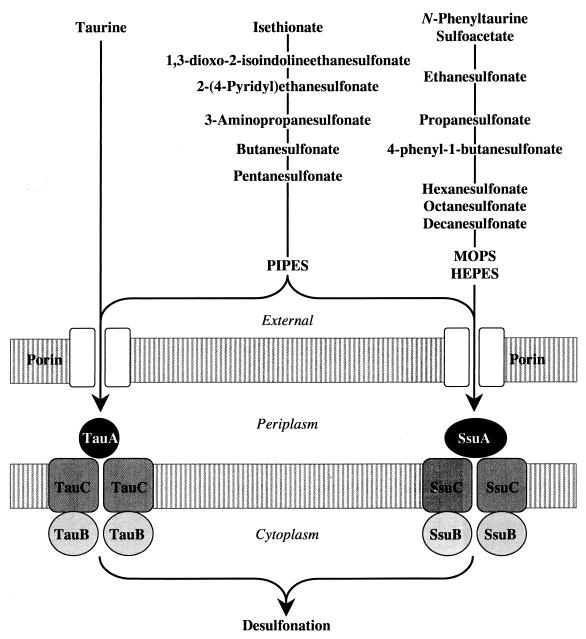

Table 3 summarizes the growth phenotypes of the different E. coli constructs that carried one or more deletions in the genes for the putative TauABC and SsuABC transporters. The growth data indicate that taurine entered the cell exclusively via the TauABC transporter, whereas N-phenyltaurine, 4-phenyl-1-butanesulfonate, sulfoacetate, ethanesulfonate, propanesulfonate, hexanesulfonate, octanesulfonate, decanesulfonate, MOPS, and HEPES were transported only by the SsuABC transporter. Some sulfonates were taken up via both the TauABC and the SsuABC systems. These included PIPES, 2-(4-pyridyl)ethanesulfonate, isethionate, 1,3-dioxo-2-isoindolineethanesulfonate, 3-aminopropanesulfonate, butanesulfonate, and pentanesulfonate, 1,3-Dioxo-2-isoindolineethanesulfonate and 3-aminopropanesulfonate appeared to be transported with the same efficiency by both systems. Figure 4 summarizes these data. Comparison of this scheme with the previously reported substrate ranges of the TauD and SsuD desulfonation enzymes (3, 4) indicates that the range of substrates transported by the SsuABC system is congruent with the substrate specificity of its desulfonation enzyme. This rule does not apply to the TauABC system, whose desulfonation enzyme reacts with propanesulfonate, hexanesulfonate, and MOPS, compounds that enter the cell exclusively via the SsuABC transporter.

FIG. 4.

Substrate specificities of the E. coli TauABC and SsuABC transporters.

As is evident from Table 3, propanesulfonate and butanesulfonate served as sulfur sources and enabled some growth of all deletion mutants examined. This suggests that these compounds enter the cell to some extent by a mechanism different from active transport by the SsuABC and TauABC systems.

To test whether triple deletion mutants such as strains EC1250 ΔtauA ΔssuB ΔtauC, EC1250 ΔssuA ΔtauB ΔssuC, EC1250 ΔssuA ΔtauBC, and EC1250 ΔtauA ΔssuCB are able to form functional hybrid transporters, these strains were inoculated into minimal medium containing one of the alkanesulfonates that are transported by both the SsuABC and the TauABC systems. The absence of growth under these conditions indicated that productive interaction between components of the two transport systems does not occur.

Complementation analysis of deletion mutants.

For the construction of complementation plasmids, it was assumed that chromosomal in-frame deletions would not affect the expression of the genes located upstream of the deleted gene or group of genes. Therefore, the genetic information available on the complementation plasmids started with the regulatory sequences of the operon of interest and ended with the sequence of the gene that had been deleted on the chromosome (Fig. 1). In the case of mutants with multiple deletions, the complementation of each deletion was investigated separately, if necessary in an intermediary deletion mutant.

ssu deletion mutants carrying the appropriate ssu complementation plasmid showed wild-type growth. However, tauA and tauB deletion mutants carrying the corresponding complementation plasmids pME4727 and pME4726 did not grow on taurine to the wild-type level. This effect was traced to the presence of the tauA gene or 540 bp of its proximal part on the high-copy-number plasmid pUC19 (data not shown). The reason for the severe growth inhibition exerted by these plasmids is not known, but complementation of tauA and tauB deletions with constructs based on the low-copy-number vector pET-24a(+) (pME4733, pME4734) was successful.

To confirm that an in-frame deletion of tauA did not affect expression of tauD, α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase activity was measured as described previously (3) in cell extracts of E. coli EC1250 and EC1250 ΔtauA grown on butanesulfonate as a source of sulfur. Identical levels of TauD specific activity were obtained from both wild-type EC1250 and mutant cells lacking TauA. The tauA deletion thus did not influence the expression of the downstream genes. Taken together, these results show that the chromosomally located in-frame deletions did not affect other gene functions and that the observed growth phenotypes were solely due to the deletion of the gene of interest.

DISCUSSION

The E. coli TauABCD and SsuEADCB systems for the assimilation of sulfur from taurine and other alkanesulfonates have previously been characterized at the level of the biochemistry of desulfonation (3, 4). Besides containing the structural genes directly involved in desulfonation, the tauABCD and ssuEADCB operons are thought to encode components of ABC transporters for sulfonates (21, 24). Based on the results from growth experiments and on sequence data, we postulate that TauABC and SsuABC form two distinct ABC transporters for uptake of alkanesulfonates. Sequence comparisons indicate that ABC-type transport systems involved in microbial desulfonation are also present in Bacillus subtilis (23) and Pseudomonas putida (25). Like in E. coli, these are encoded in the same transcription unit as the desulfonating enzyme. The deletion analysis of the E. coli taurine and alkanesulfonate transport systems presented here goes beyond amino acid sequence comparisons; it attempts to characterize these systems in terms of the substrate range and functional exchangeability of their components.

Our results demonstrate that the TauABC and the SsuABC systems complement each other with respect to the range of substrates transported. The substrate ranges of TauD and SsuD were to a large extent reflected in the substrate range of the corresponding ABC transporter. The substrate range of the SsuABC transporter fit that of the SsuD alkanesulfonate monooxygenase. This correlation is not maintained for the TauABC transport system, which was unable to transport HEPES, MOPS, and propanesulfonate, although these compounds are substrates for the TauD enzyme (3). Thus, two systems for alkanesulfonate uptake and metabolism are available in E. coli, with TauABCD being specifically involved in uptake and desulfonation of taurine and SsuEADCB being an uptake and desulfonation system for a wide range of alkanesulfonates other than taurine.

In the systems examined in this work, deletion strains that produced the substrate-binding protein of one transporter and the membrane component of the other did not grow with the sulfonates transported by either TauABC or SsuABC. Also, the formation of productive hybrid transporters in which the membrane component would be composed of the ATP-binding protein (SsuB or TauB) of one transporter and the membrane-spanning protein (SsuC or TauC) of the other transporter did not occur. The failure of hybrid transporters to support growth extended to alkanesulfonates that were common substrates of both wild-type transporters. It therefore appears to be due to the lack of interaction between the individual components of hybrid systems rather than to restrictions imposed by substrate specificity. An exception was noted when propanesulfonate or butanesulfonate was offered as a sulfur source. These compounds enabled growth, at respectable levels, of strains EC1250 ΔtauA ΔssuA and EC1250 ΔtauBC ΔssuCB as well as of mutants producing hybrid transporters (Table 3). In addition to being transported by the TauABC and/or the SsuABC system, propanesulfonate and butanesulfonate appear to enter the cell by an as-yet-unknown mechanism. Since both compounds are fully ionized under physiological conditions (8), their entrance into the cytoplasm by passive diffusion seems unlikely.

There are few reports on functional exchangeability of the components of ABC transporters in the literature. ATP-binding proteins of ABC transporters have domains in common that were shown to be functionally interchangeable in the recombinant hybrid protein HisP-MalK of Salmonella typhimurium. This protein was fully active in maltose transport but failed to complement a hisP deletion mutation (17). This observation indicated that HisP and MalK share domains that are exchangeable, whereas other domains confer system specificity by providing for interactions between the membrane-spanning protein and the ATP-binding protein (12, 17). Furthermore, complete ATP-binding proteins have successfully been exchanged between the Mal and Ugp transporters, which in E. coli transport maltose and sn-glycerol-3-phosphate, respectively (5). The N-terminal parts of the UgpC and MalK proteins exhibit approximately 60% sequence identity, which is much higher than the 35.6% sequence identity over the first 150 amino acids between the TauB and SsuB proteins.

Periplasmic binding proteins for sulfonates and sulfate esters from E. coli, B. subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and P. putida share between 22 and 45% sequence identity (25). They are less than 15% identical to other solute-binding proteins and form a family of binding proteins separate from those previously defined by Tam and Saier (19). TauA and SsuA are members of this family, but they exhibit only 22.7% sequence identity and were found to be unable to substitute for each other (Table 3). This is in contrast to the E. coli uptake systems for sulfate and thiosulfate (18) and lysine-arginine-ornithine and histidine (13), where two binding proteins of overlapping substrate specificity interact with a unique membrane component. The sulfate- and thiosulfate-binding proteins show 45% sequence identity, and the lysine-arginine-ornithine- and histidine-binding proteins are 70% identical.

The proteins of the two postulated independent transport systems of E. coli for taurine on the one hand and alkanesulfonates on the other exhibit low sequence identity but share a common physiological role. As documented by the mechanisms regulating gene expression in these systems, they both are involved in scavenging sulfur for growth. In both systems gene expression is controlled by the transcriptional activator Cbl, whose synthesis is governed by CysB, the transcriptional activator of the cys regulon (22, 24). As we have shown, the two systems also transport structurally similar compounds and partially overlap with respect to substrate range. The genes of both the tau and ssu operons do not belong to those E. coli genes believed to be acquired by lateral transfer events during the past 100 million years (9). However, in view of the above-described considerations, the driving force for evolving two separate transporters with similar function in the same organism is not evident.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich, Switzerland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boos W, Lucht J M. Periplasmic binding protein-dependent ABC transporters. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtis III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1175–1209. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg J R, Kertesz M A, Leisinger T. Characterization of α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23031–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg J R, Leisinger T. Characterization of a two-component alkanesulfonate monooxygenase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26639–26646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hekstra D, Tommassen J. Functional exchangeability of the ABC proteins of the periplasmic binding protein-dependent transport systems Ugp and Mal of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6546–6552. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6546-6552.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins C F. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagura-Burdzy G, Hulanicka D. Use of gene fusions to study expression of cysB, the regulatory gene of the cysteine regulon. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:744–751. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.3.744-751.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King J F. Acidity. In: Patai S, Rapaport Z, editors. The chemistry of sulphonic acids, esters and their derivatives. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1991. pp. 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Molecular archeology of the Escherichia coli genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9413–9417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link A J, Phillips D, Church G M. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mourez M, Hofnung M, Dassa E. Subunit interactions in ABC transporters: a conserved sequence in hydrophobic membrane proteins of periplasmic permeases defines an important site of interaction with the ATPase subunits. EMBO J. 1997;16:3066–3077. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh B-H, Kang C-H, De Bondt H, Kim S-H, Nikaido K, Joshi A K, Ferro-Luzzi Ames G. The bacterial periplasmic histidine-binding protein. Structure/function analysis of the ligand-binding site and comparison with related proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;269:4135–4143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Neill G P, Thorbjarnardóttir S, Michelsen U, Pálsson S, Söll D, Eggertsson G. δ-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency can cause δ-aminolevulinate auxotrophy in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:94–100. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.94-100.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quadroni M, Staudenmann W, Kertesz M, James P. Analysis of global responses by protein and peptide fingerprinting of proteins isolated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Application to the sulfate-starvation response of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:773–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0773u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider E, Walter C. A chimeric nucleotide-binding protein, encoded by a hisP-malK hybrid gene, is functional in maltose transport in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1375–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sirko A, Zatyka M, Sadowy E, Hulanicka D. Sulfate and thiosulfate transport in Escherichia coli K-12: evidence for a functional overlapping of sulfate- and thiosulfate-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4134–4136. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4134-4136.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tam R, Saier M H., Jr Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:320–346. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.320-346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uria-Nickelsen M R, Leadbetter E R, Godchaux W., III Sulfonate-sulfur utilization involves a portion of the assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;123:43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Ploeg J R, Weiss M A, Saller E, Nashimoto H, Saito N, Kertesz M A, Leisinger T. Identification of sulfate starvation-regulated genes in Escherichia coli: a gene cluster involved in the utilization of taurine as a sulfur source. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5438–5446. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5438-5446.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Ploeg J R, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Kertesz M A, Leisinger T, Hryniewicz M M. Involvement of CysB and Cbl regulatory proteins in expression of the tauABCD operon and other sulfate starvation-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7671–7678. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7671-7678.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Ploeg J R, Cummings N J, Leisinger T, Connerton I F. Bacillus subtilis genes for the utilization of sulfur from aliphatic sulfonates. Microbiology. 1998;144:2555–2561. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Ploeg J R, Iwanicka-Nowicka R, Bykowsky T, Hryniewicz M M, Leisinger T. The Escherichia coli ssuEADCB gene cluster is required for the utilization of sulfur from aliphatic sulfonates and is regulated by the transcriptional activator Cbl. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29358–29365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermeij P, Wietek C, Kahnert A, Wüest T, Kertesz M A. Genetic organization of sulphur-controlled aryl desulphonation in Pseudomonas putida S-313. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:913–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]