Abstract

This review is a tribute to honor Dr Douglas Paddon-Jones by highlighting his career research contributions. Dr Paddon-Jones was a leader in recognizing the importance of muscle health and the interactions of physical activity and dietary protein for optimizing the health span. Aging is characterized by loss of muscle mass and strength associated with reduced rates of muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and the ability to repair and replace muscle proteins. Research from the team at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston discovered that the age-related decline in MPS could be overcome by increasing the quantity or quality of dietary protein at each meal. Dr Paddon-Jones was instrumental in proposing and testing a “protein threshold” of ∼30 g protein/meal to optimize MPS in older adults. Dr Paddon-Jones demonstrated that physical inactivity greatly accelerates the loss of muscle mass and function in older adults. His work in physical activity led him to propose the “Catabolic Crisis Model” of muscle size and function losses, suggesting that age-related muscle loss is not a linear process, but the result of acute periods of disuse associated with injuries, illnesses, and bed rest. This model creates the opportunity to provide targeted interventions via protein supplementation and/or increased dietary protein through consuming high-quality animal-source foods. He illustrated that nutritional support, particularly enhanced protein quantity, quality, and meal distribution, can help preserve muscle health during periods of inactivity and promote health across the life course.

Keywords: muscle protein synthesis, older adults, meal patterning, disuse, physical activity

Introduction

This invited review highlights the research legacy of Distinguished Professor Dr Douglas J Paddon-Jones, who passed away abruptly on August 12, 2021. Dr Paddon-Jones was a leading international expert in dietary protein, muscle metabolism, and aging. His contributions and advancements in these areas lay the foundation for establishing protein recommendations that promote skeletal muscle preservation, sarcopenia prevention, and overall health and well-being, particularly during inactivity with aging in healthy and clinical populations. Equally inspiring was his ability to communicate scientific evidence in an ingenious, witty, and practical manner that would captivate scientific audiences and the general public [1].

Dr Paddon-Jones was born in Brisbane, Australia. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in Human Movement Studies from the University of Queensland, Australia, and a Master of Science Degree in Exercise Physiology from Ball State University. He completed his Doctor of Philosophy in Human Movement Studies at the University of Queensland, Australia, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship in protein metabolism at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB). He then joined the faculty at UTMB and became the Sheridan Lorenz Distinguished Professor in Aging and Health. Dr Paddon-Jones was a fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine and an active American Society for Nutrition member, receiving the Vernon Young International Award for Amino Acid Research.

Throughout his academic career, Dr Paddon-Jones was the driving force for several key discoveries. He demonstrated that physical inactivity greatly accelerates the loss of muscle mass and function in middle-aged and older adults [2]. He illustrated that nutritional support, particularly in the form of enhanced protein quantity, quality, and meal distribution, can help preserve muscle health during periods of inactivity and promote health across the life course [[2], [3], [4]].

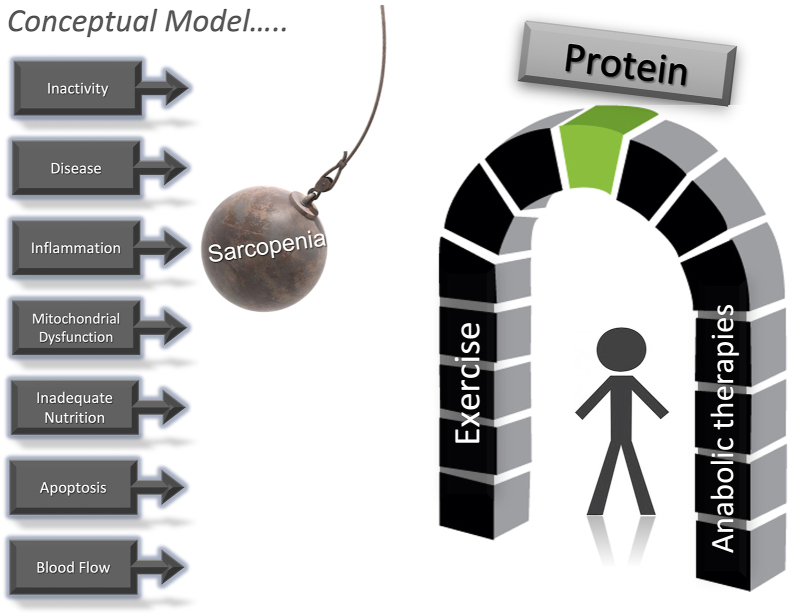

As a result of these findings, Dr Paddon-Jones and colleagues proposed the “Catabolic Crisis Model” of muscle/function loss, which illustrates the insult to lean mass due to repeated bout of musclar inactivity related to injury or illness in older adults [5]. This model creates the opportunity to provide targeted prevention and treatment interventions via protein supplementation and/or increased dietary protein through the consumption of high-quality animal-source foods. Dr Paddon-Jones was also instrumental in proposing and testing a “protein threshold” of ∼30 g protein/meal to help maintain muscle mass and function in older adults [2] and extended this research to confirm a similar “protein threshold” of ∼30 g protein/meal for appetite control and satiety [6]. Other novel models included the assessment of “even protein distribution” across the day to promote muscle health [7] and a “Protein Shot” to augment meals containing “suboptimal” protein quantities [8]. These proposed models and principles continue to be explored and may provide novel insights when developing healthy dietary patterns that optimize protein quantity and timing of consumption across the life course. This review is a tribute to highlight the career of Dr. Douglas Paddon-Jones.

Targeting Protein Quantity, Quality, and Distribution

Aging is characterized by a decline in the rate of total protein synthesis across virtually all cells. Age-related changes in the efficiency of protein synthesis are associated with changes in transcription and translation factors, including reduced efficiency of ribosomes, reduced amounts of mRNAs, and reduced activity of initiation factors such as eukaryotic initiation factor 4 (eIF4). The consequences of slower rates of protein synthesis manifest as aging pathology [9]. In skeletal muscle, this pathology is defined as sarcopenia, characterized by a loss of functional mobility and reduced metabolic flexibility, increasing risk for obesity, diabetes, and heart disease [10].

With this backdrop, during the early 2000s, there were a series of findings and a convergence of ideas that changed thinking about aging and guidelines for dietary protein. Dietary recommendations had long recognized protein needs for growth to generate positive nitrogen balance, but conventional wisdom was that nongrowing adults in maintenance had lower protein needs. There was a general acceptance that the RDA of 0.8 g/kg/d was adequate both as a minimum and optimum dietary intake for adults. However, with an increasing focus on aging and health, optimal protein intake for older adults received renewed interest. Dr Paddon-Jones was a leader in changing our views about the requirements for protein quantity, quality, and distribution to maintain and promote healthy muscles [11].

Dr Paddon-Jones was part of a team of researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston investigating the age-related decline in muscle protein synthesis (MPS). They discovered that the rate of MPS during postabsorptive periods (ie, after an overnight fast) was not different for young (age ∼30 y) compared with older (age ∼65 y) adults [12]. These investigators theorized that the difference between young and older adults must be during the anabolic period after a meal associated with the influx of amino acids. In a series of elegant studies, they found that the postmeal anabolic response was age-related and dependent on the quantity and quality of protein consumed and, specifically, the essential amino acid (EAA) content of the meal [13, 14]. They established that although the efficiency of MPS declined with aging, aging did not affect the maximum postmeal MPS rate when dietary protein was adequate.

Concurrent with these findings, mechanistic research with rodents revealed that regulation of MPS depended on the plasma and/or intracellular concentration of the EAA leucine [[15], [16], [17]]. During catabolic conditions such as exhaustive exercise or short-term fasting, MPS is downregulated at the translation initiation step mediated by eIF4, presumably to maintain ATP for myofibrillar contraction. Recovery requires increased plasma leucine concentration to stimulate a signaling cascade through the protein kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin in complex 1 (mTORC1) to activate eIF4 and ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) to initiate MPS. Leucine is now well established as a unique dietary signal triggering a postmeal recovery response.

Dr Paddon-Jones was a leader in demonstrating the practical application of these research findings. In an early study, the Galveston group compared the MPS response in older adults (age ∼68 y) by providing isocaloric meals with 15 g of amino acids from either whey protein or EAA [18]. Whey protein is a high-quality protein, rich in EAA, with a rapid digestion profile. The whey treatment contained 1.75 g of leucine and produced a 35% increase in MPS after the meal. In comparison, the EAA treatment provided 2.79 g of leucine resulting in a 57% increase in MPS, highlighting the importance of specific EAA balance and suggesting that a leucine-rich mixture of EAA may be a more energetically efficient nutritional supplement for maintaining MPS in older adults. The unique role of leucine was confirmed in a subsequent study [14].

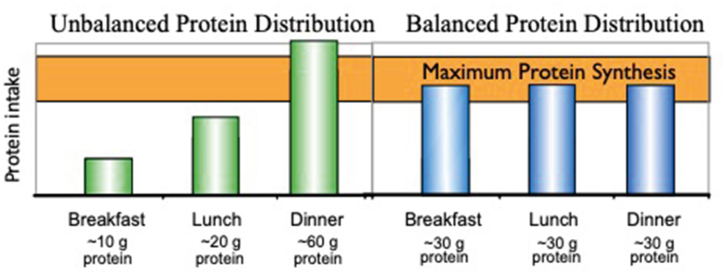

Prior to these findings with older adults, dietary protein requirements were assumed to be a net daily intake, and the meal distribution of protein was not important. However, this research on MPS in older adults suggested that the composition of individual meals was also important. Another piece of the puzzle was defining the duration of the postmeal MPS response. Research with animals [19] and humans [20] demonstrated that the duration of the postmeal MPS response was 2 to 2.5 h. Furthermore, the duration was independent of the protein quantity at the meal or the signaling status of mTORC1 or initiation factors. These findings led to a review of American eating patterns that reflected consumption of approximately 60% of daily protein in a single meal late in the day (ie, dinner) with less than 10 g of protein in the first meal. Dr Paddon-Jones theorized that a more even protein distribution across the meals would enhance the anabolic response (Figure 1) [11].

FIGURE 1.

The typical American eating pattern results in the majority of protein being consumed at the last meal of the day (unbalanced). Studies on muscle protein synthesis suggest that redistributing protein to achieve a minimum threshold at the first meal (balanced) may be beneficial for muscle health. (Figure from presentation files of Dr Paddon-Jones).

In a seminal study, Dr Paddon-Jones demonstrated that redistributing protein from the dinner meal to the first meal of the day enhanced net daily MPS [7]. Using a crossover design, study participants were provided 90 g/d of protein for 2, 7-day periods. The control treatment distributed the protein as 10, 20, and 60 g at breakfast, lunch, and dinner, respectively, to stimulate the quantity and distribution typical of American diets. The second treatment distributed the same amount of protein as 30, 30, and 30 g, respectively. The 30 g meal amounts provided 2.5 g of leucine to trigger the MPS initiation process. Measurement of MPS for 24 h revealed that redistributing protein from a large dinner meal to the first meal of the day increased net daily MPS by 25% with the same total daily protein. These findings have become the foundation for dietary protein recommendations for adults that now emphasize obtaining at least 2.5 g of leucine and a minimum of 30 g of proteins at each meal [21].

Applications of Protein Quantity, Quality, and Distribution

Although increasing dietary protein and specifically leucine-rich EAAs at the first meal after a prolonged, overnight fast produces dramatic increases in MPS [14, 22], the impact of redistributing dietary protein on actual changes in muscle mass is less clear [23, 24]. Dr Paddon-Jones’ experiment demonstrating greater daily MPS when protein intake was redistributed from a skewed (10–20–60 g/meal) pattern to an even (30–30–30 g/meal) pattern [7] prompted research testing of this protein distribution concept. For example, Dr Paddon-Jones and colleagues at Purdue University conducted a randomized, controlled feeding trial designed to assess whether within-day protein intake distribution (skewed vs. even) influenced changes in body composition, including skeletal muscle size, of overweight adults after a 16-wk period of moderate energy restriction and resistance exercise training [25]. After 16 wk, there was no difference in lean body mass. Participants provided with an even distribution of the dietary protein lost approximately 8.6 kg of body weight and 7.1 kg of body fat, whereas participants provided with a skewed distribution lost 7.3 kg of body weight and 6.8 kg of body fat. Lean body mass changes and midthigh muscle area were not different between groups.

However, in a similar weight loss study using a 2 × 2 experimental design with resistance exercise and diet groups, both resistance exercise and increased dietary protein at the first meal had positive and additive effects on sparing lean body mass [26]. This study demonstrated that resistance exercise had a greater impact on changes in muscle mass than the distribution of dietary protein. Comparing the two studies, Hudson et al. [25] found that approximately 90% of the weight lost was body fat (83% even and 93% skewed groups, respectively). Likewise, in the study by Layman et al. [26], body fat loss was approximately 90% in the exercise plus diet group, whereas body fat loss in the group receiving no exercise and the skewed diet was only 64% of the total weight loss. These data suggest that resistance exercise has a much greater impact on muscle mass than the redistribution of dietary protein in the context of a weight loss diet.

Although dietary advice often includes recommendations for an “even” protein distribution [21], the current evidence on the efficacy of consuming an “optimal” protein distribution to favorably influence skeletal muscle–related changes is limited and inconsistent. Some studies showed beneficial effects of protein distribution [23, 27] and others found no effects. In total, “the effect of protein distribution cannot be sufficiently disentangled from the effect of protein quantity” [24].

The total daily quantity of protein and the meal distribution may be synergistically related. Optimal MPS rates are obtained with ∼30 g of high-quality protein at the first meal, whereas most adults only consume approximately one-third of this amount. Dr Paddon-Jones and colleagues at Purdue University, as well as, researchers from other laboratories tested this concept by supplementing protein at the breakfast meal. Increasing total daily protein by supplementing a low-protein breakfast meal had beneficial effects on plasma amino acid profiles [8] and lean body mass [28]. Consuming a more balanced protein distribution by supplementing protein at the breakfast meal may be a practical way for adults with marginal or inadequate protein intakes (<0.80 g/kg/d) to achieve a moderately higher total protein intake [28]. The precise balance of protein quantity, quality, and distribution for diverse populations and physiological conditions to obtain optimal muscle health remains a critical area for future research.

Protein quantity and quality are also embedded in food patterns. Red meat is one of the most controversial sources of high-quality protein rich in EAAs. Numerous epidemiologic studies report the association of red meat with negative health outcomes including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes leading to dietary recommendations to reduce red meat consumption [29]. However, the association of red meat with negative cardiovascular disease outcomes may be confounded by overall lifestyle choices posing the question, Is the association with negative health outcomes due to red meat or the nutritional and lifestyle “company” it keeps? Dr Paddon-Jones and colleagues at Purdue explored this question using a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern, which is recognized as heart-healthy [30]. Using a randomized, crossover, controlled feeding study, overweight subjects (BMI ≈ 30.5 kg/m2) were provided foods for 2 5-wk intervention periods. Both treatment arms provided identical amounts of seafood, olive oil, and nuts plus 7 servings of vegetables, 4 servings of fruits, and 4 servings of whole grains and provided ∼115 g/d of protein (18% of energy intake). One treatment contained ∼500 g/wk of fresh, lean, unprocessed red meat (comparable to the average US intake), and the control diet contained ∼200 g/wk (comparable to standard recommendations for a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern). Higher red meat intake promoted greater reductions in total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol, whereas the quantity of red meat consumed did not influence improvements in blood pressure. The study demonstrated the effectiveness of consuming a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern with different amounts of lean, unprocessed red meat to improve multiple cardiometabolic disease risk factors in overweight adults.

Muscle Health and Aging – The “Catabolic Crisis”

Age-related sarcopenia describes the loss of muscle mass, strength, and function with age [31]. It is not known precisely when sarcopenia begins, but it is likely in or around a person’s fifth decade of life (ie, a person’s 40s) [32]. The rate of sarcopenic muscle loss is ∼0.8% per year and is detectable with most methods in people’s sixth decade of life [32]. The paradigm of sarcopenic muscle loss has been recognized as treatable, and the syndrome now has an international classification of disease code [33]. The often-cited paradigm is that sarcopenia proceeds, and at some point, a degree of muscle loss is reached, at which point an older person would have an increased risk of mobility issues [34] and other muscle-associated morbidities and even an elevated risk of mortality [35]. Hence, there has been a large effort to search for interventions that can mitigate the decline in sarcopenia to extend the period of a person’s life during which they are mobile and in good health. The two most potent countermeasures to sarcopenia are exercise, particularly resistance exercise, and dietary protein [36].

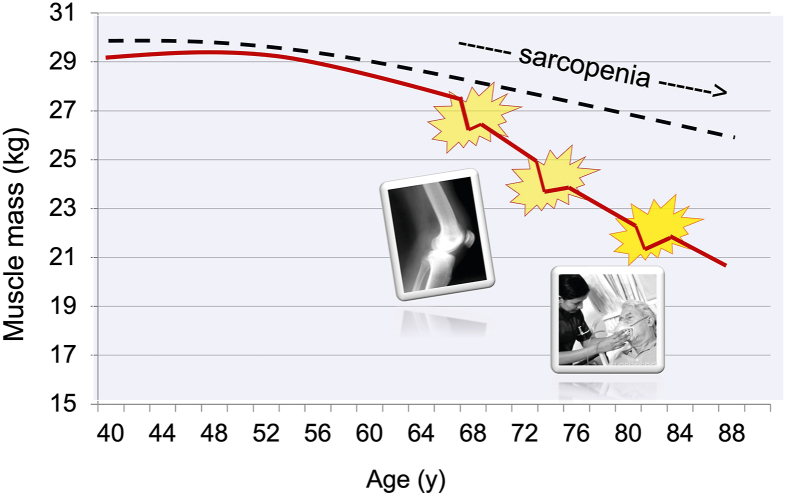

It may be that the usual sarcopenic decline in muscle mass and function is unlikely to be problematic for many as they age, but as English and Paddon-Jones pointed out in 2010, a “catabolic crisis” is a watershed moment in an aging person’s life (5) (Figure 2). These authors stated that “ …with advancing age, it becomes increasingly likely that even a brief, clinically mandated period of bed rest could initiate a serious decline in muscle strength and functional capacity, ie, a “tipping point” from which some may not fully recover.” They went on to point out, “ …there should be a clear conceptual distinction between the traditional, insidious sarcopenic process and the accelerated episodic loss of muscle and functional capacity during a ‘catabolic crisis’.” As few as five days of inactivity can significantly compromise muscle health, particularly in hospitalized adults [[37], [38], [39]]. Events leading to bed rest and catabolism in aging could be as devastating as a fall or protracted viral infection requiring prolonged hospitalization or admittance to the intensive care unit. Alternatively, a catabolic event could begin with a benign bout of flu compounded by a short hospital stay because of respiratory distress followed by a prolonged (weeks to months) convalescence. An extension of the bed rest model of muscle disuse was recognizing that a period of reduced ambulatory activity would mean a relative “disuse” of leg muscle, experimentally recapitulated by the so-called “reduced step model” [40].

FIGURE 2.

The conventional sarcopenia model (dashed line) suggests a linear age-related loss of muscle mass, whereas the Catabolic Crisis model (solid line) depicts aging punctuated with acute catabolic insults such as bone fracture, joint replacement, illness, or bed rest. (Figure from presentation files of Dr Paddon-Jones).

Interestingly, the coining of the term "catabolic crisis" by English and Paddon-Jones [5], in the context of their paradigm, was underpinned by a reduction in MPS more than an increase in muscle protein breakdown. Thus, the net catabolism during disuse (and arguably sarcopenia) is more a matter of reductions in protein synthesis than increased proteolysis, making the support of protein synthesis the obvious process to target in mitigating disuse atrophy [40]. The suppression of proteolysis, although a seemingly erstwhile goal to offset atrophic muscle loss, is likely a poor strategy as it would lead to the accumulation/aggregation of damaged (misfolded or oxidized) proteins.

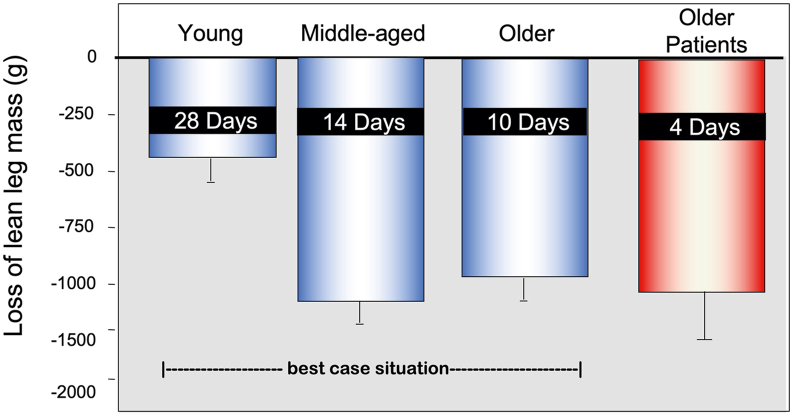

The disuse–catabolic crisis remains a turning point for older persons [41] because it is difficult, if not impossible, from which to recover. For various reasons, older skeletal muscle has a reduced regenerative capacity. Therefore, the decline in muscle mass and strength that occurs over a short duration of disuse can have a lasting impact on functional mobility. An estimated 70% of hospitalized adults are discharged below their preadmission level of function, and many experience long-lasting physical impairment [42]. Repeated bouts of inactivity in middle-aged and older adults exacerbate underlying health conditions [43], accelerate declines in functional capacity [3], can lead to early mortality, and contribute to the annual $40 billion economic cost linked to age-related loss of muscle [44]. It is also important to point out that although healthy middle-aged adults often have a phenotype clinically indistinguishable from younger adults, this population can lose two to three times more skeletal muscle than younger adults over a similar period of disuse [3, 45] (Figure 3). The onset of middle age also coincides with the natural decline in skeletal muscle mass that begins around the fourth decade of life [11]. Together, these data emphasize the problem and Dr Paddon-Jones recognized the need to develop pragmatic, cost-effective interventions that can be easily implemented in a clinical setting to support muscle health during brief periods of disuse. With no prospect of pharmacologic therapies to counteract aging or disuse-related muscle atrophy, Dr Paddon-Jones focused on developing nutrition support and exercise protocols as the first line of defense.

FIGURE 3.

Loss of leg lean mass following bed rest in young, middle-aged, older healthy adults, and a comparative group of older hospitalized patients. Younger adults are relatively protected from loss of leg lean mass during disuse, whereas middle-aged and older adults experience a rapid decline in leg lean mass, losing up to 1 kg in just 7 d. The loss of lean mass in older adults has likely exacerbated in the presence of a procatabolic environment, ie, an underlying illness. (Figure from presentation files of Dr Paddon-Jones; data are compiled from a series of published studies, young [45], middle-aged [3], and older adults [53]; the older patient leg lean mass loss is unpublished pilot data).

Supporting Muscle and Metabolic Health During Disuse With Nutrition and Physical Activity

At the most fundamental level, maintenance of skeletal muscle health requires consuming adequate amounts of dietary protein to ensure a sufficient supply of amino acid building blocks to mount an anabolic response. Although a first instinct may be to increase daily protein as an intervention during disuse or hospitalization, this may not always be metabolically advantageous because the postmeal anabolic response requires specific amounts of EAA and the protein-synthetic response is maximally stimulated by a moderate serving of high-quality protein. Amino acid intakes exceeding the anabolic threshold cannot be stored and are oxidized as additional energy. This concept was demonstrated by a study led by Dr Paddon-Jones in which older adults consuming either a moderate serving (30 g) or a large serving (90 g) of high-quality beef protein had similar protein-synthetic responses to the differing protein amounts [46]. In addition to the metabolic constraints, the target populations may have barriers that limit the consumption of large amounts of protein, such as compromised kidney function or practical issues, including satiety, body composition goals, dentition, and food cost.

Addressing the need for pragmatic interventions for disuse, Dr Paddon-Jones and his group conducted a series of studies to evaluate targeted protein- and physical activity–based interventions on skeletal muscle health during bed rest in middle-aged and older adults. In the absence of any intervention, healthy middle-aged (45–60 y) and older adults (65–80 y) consuming slightly above the RDA for protein (0.9 kg/g protein) lose an average of 1 kg of lean mass from their lower limbs following 7 d of bed rest. Supplementing these cohorts with a small amount of the branched-chain amino acid leucine, (∼4 to 6 g) at each meal attenuated leg lean mass loss by ∼50% [3,47].

Although isolated amino acids, such as leucine and other branched-chain amino acids, have been successfully used in clinical studies to protect muscle mass during disuse (3, 45 47), some challenges prohibit clinical implementation, such as palatability, volume, and cost and ultimately the need for all of the EAA to optimize the anabolic response [48]. Utilizing readily available foods or supplements that contain leucine-rich, high-quality protein can offer a similar anabolic response with a complete mixture of EAA. Providing a diet enriched with whey protein partially protected from the loss of leg lean mass and accelerated fat mass loss in older adults undergoing 7 d of bed rest compared with isonitrogenous controls [49].

Although the ability of protein-based nutritional support to slow the loss of leg lean mass during disuse is promising, it is important to recognize the time-sensitive limitation of such interventions in the overwhelming catabolic environment presented by extended periods of inactivity. Although leucine supplementation protected against leg lean mass loss in middle-aged adults following 7 d of disuse, by 14 d of bed rest,the leg lean mass loss of the leucine-supplemented group and the isonitrogenous control group was equivalent [3].

In addition to high-quality protein, moderate, purposeful physical activity is beneficial, when appropriate, to support muscle health. In a cohort of healthy, community-dwelling older adults undergoing a 7-day bed rest protocol, those who completed a single bout of 2000 steps each day (equivalent to ∼20 min of walking at a moderate pace) experienced a partial reduction in the negative effects of disuse on lean leg mass and insulin sensitivity [50].

Dr Paddon-Jones established the following recommendations, foundational to support muscle health during aging and can be extended to circumstances that compromise skeletal muscle health such as restricted physical activity/sedentary behavior (Figure 4).

-

1)

Consume a moderate amount (0.5 g/kg/meal) [51] of high-quality protein (high leucine and EAA) with each meal [3, 47, 49, 52];

-

2)

Incorporate habitual exercise in close temporal proximity to protein-containing meals [40]; and

-

3)

React aggressively to combat the accelerated loss of muscle mass and function during acute catabolic crises and periods of impaired physical activity [4, 5, 52].

FIGURE 4.

The Catabolic Crisis Model depicts sarcopenia as an accumulation of episodic challenges. Mitigation of these catabolic events is built on pillars of resistance exercise and anabolic therapies. The keystone to balancing these pillars is providing adequate quantity and quality of dietary protein. (Figure from presentation files of Dr. Paddon-Jones.)

Although Dr Paddon-Jones was a tremendous researcher, he was also known as a true friend, collaborative colleague, and engaging mentor to so many people around the world. We hope that this summary will honor his academic life and provide an opportunity for young investigators to better understand the impact Dr Paddon-Jones’ research continues to have in the nutrition world.

Author disclosures

DKL is on the advisory boards for Nutrient Institute and Herbalife, a research consultant to National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, and a partner in Metabolic Designs. HJL received grants from the Beef Checkoff and Egg Nutrition Center; and is on the scientific advisory boards for the National Pork Board and the Beef Matrix Collaborative; HJL is also on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Nutrition. SMP received grants or research contracts from the US National Dairy Council, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, Dairy Farmers of Canada, Roquette Freres, Ontario Centre of Innovation, Nestle Health Sciences, Myos, National Science and Engineering Research Council, and the US NIH, personal fees from Nestle Health Sciences, nonfinancial support from Enhanced Recovery, outside the submitted work. SMP has patents licensed to Exerkine but reports no financial gains from any patent or related work. WWC was receiving funding for research, travel, or honoraria for scientific presentations or consulting services, when this manuscript was written, from the following organizations: US National Institutes of Health, US Department of Agriculture, Mushroom Council, Foundation for Meat and Poultry Research and Education, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, Whey Protein Research Consortium, and the National Dairy Council. EAL has no disclosures.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed equally to writing this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors report funding from National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, Egg Nutrition Center, US Dairy Council, Dairy Farmers of Canada, Myos, Nestle Health Science, National Science and Engineering Council, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Agriculture, Mushroom Council, Foundation for Meat & Poultry Research & Education, and Whey Protein Research Consortium.

References

- 1.Paddon-Jones D.J. In: Protein, muscle and inactivity: projecting muscle health during aging. Services U.H.M., editor. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paddon-Jones D., Campbell W.W., Jacques P.F., Kritchevsky S.B., Moore L.L., Rodriguez N.R., et al. Protein and healthy aging. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1339S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084061. 45S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.English K.L., Mettler J.A., Ellison J.B., Mamerow M.M., Arentson-Lantz E., Pattarini J.M., et al. Leucine partially protects muscle mass and function during bed rest in middle-aged adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):465–473. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.112359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvan E., Arentson-Lantz E., Lamon S., Paddon-Jones D. Protecting skeletal muscle with protein and amino acid during periods of disuse. Nutrients. 2016;8(7) doi: 10.3390/nu8070404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.English K.L., Paddon-Jones D. Protecting muscle mass and function in older adults during bed rest. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(1):34–39. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333aa66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paddon-Jones D., Leidy H. Dietary protein and muscle in older persons. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamerow M.M., Mettler J.A., English K.L., Casperson S.L., Arentson-Lantz E., Sheffield-Moore M., et al. Dietary protein distribution positively influences 24-h muscle protein synthesis in healthy adults. J Nutr. 2014;144(6):876–880. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.185280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson J.L., Paddon-Jones D., Campbell W.W. Whey protein supplementation 2 hours after a lower protein breakfast restores plasma essential amino acid availability comparable to a higher protein breakfast in overweight adults. Nutr Res. 2017;47:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rattan S.I. Synthesis, modifications, and turnover of proteins during aging. Exp Gerontol. 1996;31(1–2):33–47. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(95)02022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roubenoff R., Hughes V.A. Sarcopenia: current concepts. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(12):M716–M724. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.12.m716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paddon-Jones D., Rasmussen B.B. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(1):86–90. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831cef8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volpi E., Sheffield-Moore M., Rasmussen B.B., Wolfe R.R. Basal muscle amino acid kinetics and protein synthesis in healthy young and older men. JAMA. 2001;286(10):1206–1212. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paddon-Jones D., Sheffield-Moore M., Zhang X.J., Volpi E., Wolf S.E., Aarsland A., et al. Amino acid ingestion improves muscle protein synthesis in the young and elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286(3):E321–E328. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00368.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsanos C.S., Kobayashi H., Sheffield-Moore M., Aarsland A., Wolfe R.R. A high proportion of leucine is required for optimal stimulation of the rate of muscle protein synthesis by essential amino acids in the elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291(2):E381–E387. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00488.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gautsch T.A., Anthony J.C., Kimball S.R., Paul G.L., Layman D.K., Jefferson L.S. Availability of eIF4E regulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis during recovery from exercise. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(2):C406–C414. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthony J.C., Anthony T.G., Layman D.K. Leucine supplementation enhances skeletal muscle recovery in rats following exercise. J Nutr. 1999;129(6):1102–1106. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthony J.C., Yoshizawa F., Anthony T.G., Vary T.C., Jefferson L.S., Kimball S.R. Leucine stimulates translation initiation in skeletal muscle of postabsorptive rats via a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. J Nutr. 2000;130(10):2413–2419. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.10.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paddon-Jones D., Sheffield-Moore M., Katsanos C.S., Zhang X.J., Wolfe R.R. Differential stimulation of muscle protein synthesis in elderly humans following isocaloric ingestion of amino acids or whey protein. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(2):215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton L.E., Layman D.K., Bunpo P., Anthony T.G., Brana D.V., Garlick P.J. The leucine content of a complete meal directs peak activation but not duration of skeletal muscle protein synthesis and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in rats. J Nutr. 2009;139(6):1103–1109. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.103853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atherton P.J., Etheridge T., Watt P.W., Wilkinson D., Selby A., Rankin D., et al. Muscle full effect after oral protein: time-dependent concordance and discordance between human muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1080–1088. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer J., Biolo G., Cederholm T., Cesari M., Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Morley J.E., et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):542–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy C.H., Churchward-Venne T.A., Mitchell C.J., Kolar N.M., Kassis A., Karagounis L.G., et al. Hypoenergetic diet-induced reductions in myofibrillar protein synthesis are restored with resistance training and balanced daily protein ingestion in older men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308(9):E734–E743. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00550.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pikosky M.A., Cifelli C.J., Agarwal S., Fulgoni V.L., 3rd Association of dietary protein intake and grip strength among adults aged 19+ years: NHANES 2011-2014 analysis. Front Nutr. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.873512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson J.L., Iii R.E.B., Campbell W.W. Protein distribution and muscle-related outcomes: does the evidence support the concept? Nutrients. 2020;12(5) doi: 10.3390/nu12051441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudson J.L., Kim J.E., Paddon-Jones D., Campbell W.W. Within-day protein distribution does not influence body composition responses during weight loss in resistance-training adults who are overweight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(5):1190–1196. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.158246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Layman D.K., Evans E., Baum J.I., Seyler J., Erickson D.J., Boileau R.A. Dietary protein and exercise have additive effects on body composition during weight loss in adult women. J Nutr. 2005;135(8):1903–1910. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farsijani S., Cauley J.A., Santanasto A.J., Glynn N.W., Boudreau R.M., Newman A.B. Transition to a more even distribution of daily protein intake is associated with enhanced fat loss during a hypocaloric and physical activity intervention in obese older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(2):210–217. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1313-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton C., Toomey C., McCormack W.G., Francis P., Saunders J., Kerin E., et al. Protein supplementation at breakfast and lunch for 24 weeks beyond habitual intakes increases whole-body lean tissue mass in healthy older adults. J Nutr. 2016;146(1):65–69. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.219022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill E.R., O’Connor L.E., Wang Y., Clark C.M., McGowan B.S., Forman M.R., et al. Red and processed meat intakes and cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: an umbrella systematic review and assessment of causal relations using Bradford Hill’s criteria. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022:1–18. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2123778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor L.E., Paddon-Jones D., Wright A.J., Campbell W.W. A Mediterranean-style eating pattern with lean, unprocessed red meat has cardiometabolic benefits for adults who are overweight or obese in a randomized, crossover, controlled feeding trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(1):33–40. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Bahat G., Bauer J., Boirie Y., Bruyère O., Cederholm T., et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssen I., Heymsfield S.B., Wang Z.M., Ross R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(1):81–88. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anker S.D., Morley J.E., von Haehling S. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7(5):512–514. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen I., Baumgartner R.N., Ross R., Rosenberg I.H., Roubenoff R. Skeletal muscle cutpoints associated with elevated physical disability risk in older men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(4):413–421. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu P., Hao Q., Hai S., Wang H., Cao L., Dong B. Sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2017;103:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunes E.A., Colenso-Semple L., McKellar S.R., Yau T., Ali M.U., Fitzpatrick-Lewis D., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of protein intake to support muscle mass and function in healthy adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(2):795–810. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Covinsky K.E., Palmer R.M., Fortinsky R.H., Counsell S.R., Stewart A.L., Kresevic D., et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirsch C.H., Sommers L., Olsen A., Mullen L., Winograd C.H. The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(12):1296–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sager M.A., Franke T., Inouye S.K., Landefeld C.S., Morgan T.M., Rudberg M.A., et al. Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(6):645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oikawa S.Y., Holloway T.M., Phillips S.M. The impact of step reduction on muscle health in aging: protein and exercise as countermeasures. Front Nutr. 2019;6:75. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell K.E., von Allmen M.T., Devries M.C., Phillips S.M. Muscle disuse as a pivotal problem in sarcopenia-related muscle loss and dysfunction. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5(1):33–41. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2016.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zisberg A., Shadmi E., Gur-Yaish N., Tonkikh O., Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):55–62. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Booth F.W., Roberts C.K., Thyfault J.P., Ruegsegger G.N., Toedebusch R.G. Role of inactivity in chronic diseases: evolutionary insight and pathophysiological mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(4):1351–1402. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goates S., Du K., Arensberg M.B., Gaillard T., Guralnik J., Pereira S.L. Economic impact of hospitalizations in US adults with sarcopenia. J Frailty Aging. 2019;8(2):93–99. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2019.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paddon-Jones D., Sheffield-Moore M., Urban R.J., Sanford A.P., Aarsland A., Wolfe R.R., et al. Essential amino acid and carbohydrate supplementation ameliorates muscle protein loss in humans during 28 days bedrest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(9):4351–4358. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Symons T.B., Sheffield-Moore M., Wolfe R.R., Paddon-Jones D. A moderate serving of high-quality protein maximally stimulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis in young and elderly subjects. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(9):1582–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.06.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arentson-Lantz E.J., Fiebig K.N., Anderson-Catania K.J., Deer R.R., Wacher A., Fry C.S., et al. Countering disuse atrophy in older adults with low-volume leucine supplementation. J Appl Physiol. 2020;128(4):967–977. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2019. 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Escobar J., Frank J.W., Suryawan A., Nguyen H.V., Davis T.A. Amino acid availability and age affect the leucine stimulation of protein synthesis and eIF4F formation in muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(6):E1615–E1621. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arentson-Lantz E.J., Galvan E., Ellison J., Wacher A., Paddon-Jones D. Improving dietary protein quality reduces the negative effects of physical inactivity on body composition and muscle function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(10):1605–1611. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arentson-Lantz E., Galvan E., Wacher A., Fry C.S., Paddon-Jones D.2,000. Steps/day does not fully protect skeletal muscle health in older adults during bed rest. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27(2):191–197. doi: 10.1123/japa.2018-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore D.R., Churchward-Venne T.A., Witard O., Breen L., Burd N.A., Tipton K.D., et al. Protein ingestion to stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis requires greater relative protein intakes in healthy older versus younger men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(1):57–62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips S.M., Paddon-Jones D., Layman D.K. Optimizing adult protein intake during catabolic health conditions. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(4):S1058–S1069. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kortebein P., Symons T.B., Ferrando A., Paddon-Jones D., Ronsen O., Protas E., et al. Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(10):1076–1081. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]