Abstract

Shrimp and Crab, important sources of protein, are currently being adversely affected by the rising industrialization, which has led to higher levels of heavy metals. The goal of this study was to evaluate the health risks of contamination associated with nine heavy metals (Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Al, and Fe) in two species of shrimp (Macrobrachium rosenbergii and Metapenaeus monoceros) and one species of crab (Scylla serrata) that were collected from the Khulna, Satkhira, and Bagerhat areas of Bangladesh. Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was used for the study. The results showed that all metal concentrations in shrimp and crab samples were below the recommended level, indicating that ingestion of these foods would not pose any substantial health risks to individuals. To evaluate the non-carcinogenic health risks, the target hazard quotient (THQ) and hazard index (HI) were determined, and the target cancer risk (TR) was utilized to evaluate the carcinogenic health risks. From the health point of view, this study showed that crustaceans obtained from the study sites were non – toxic (THQ and HI < 1), and long-term, continuous intake is unlikely to pose any significant health hazards (TR = 10−7-10−5) from either carcinogenic or non-carcinogenic effects.

Keywords: Bioaccumulation, Metal toxicity, Estimated daily intake, Human health hazard, Target cancer risk, ICP-OES

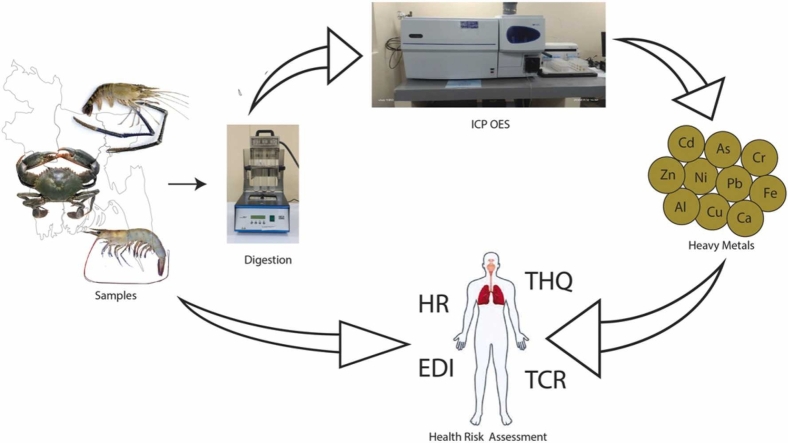

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Presence of heavy metals in shrimp and crab was measured.

-

•

Target Cancer Risk from consuming fish were evaluated.

-

•

Shrimps and crabs were found to be safe for consumption.

1. Introduction

In recent time, an upsurge trend was found in shrimp consumption. The movement was toward a greater awareness of a balanced diet and the nutritional value of seafood consumption, such as the advantages of consuming seafood that is high in protein, vitamin D, vitamin B3, and zinc [1]. Being one of Bangladesh's top export sectors, processed frozen shrimp generates roughly $448 million annually. 80% of Bangladesh's frozen food exports are comprised of shrimp, which also accounts for 2.5% of the global shrimp market [2]. In contrast to the possible health benefits of eating fish, chemical contaminants found in these food items have become a matter of concern, especially for people who eat fish frequently [3], [4]. Heavy metal buildup in the body's tissues can lead to chronic sickness and have negative effects on the wider population [5]. Chronic exposure to heavy metals such as Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Al, and Fe above their acceptable threshold has negative effects on both humans and animals and can pose serious health risk, including neurological issues, headaches, liver damage, gastrointestinal distress, increase red blood cells, reduce lung functions, induce renal tumors, reduce cognitive development, high blood pressure, kidney dysfunctions, osteomalacia and reproductive deficiencies [6], [7], [8], [9]. Water, sediment, and fish feed are the three main ways that shrimp and crabs can become contaminated with heavy metals. Industrial wastes, geochemical structures, and metal mining created a potential source of heavy metal contamination in the aquatic environment [10], [11].

Global attention has been drawn to the problem of trace metal contamination of aquatic environments, particularly in developing nations like Bangladesh [12]. This issue has become a challenge for scientists around the world [13], [14]. Numerous academic studies discovered a substantial association between fish and sediments [15], [16]. Industrial activities, mining, and the dumping of toxic metal-containing effluents that have not been fully treated are the major human-caused sources of heavy metal pollution of water, sediment, and aquatic life [17], [18]. Metal contamination has been on the rise due to the quick development of industry and agriculture, which is dangerous for humans, fish, and invertebrates [19]. Because of the city's tens of thousands of industrial facilities and sewerage systems, which routinely discharge massive amounts of hazardous waste into these rivers, river pollution is becoming more and more severe [13], [20]. Many fields in Bangladesh's southern region are swamped by this river water during the rainy season. As a result, contaminated shrimp and crabs, and water are introduced into the farms with heavy metals. Prawns are omnivores, thus, to promote quicker growth, industrially produced feed that fits their dietary requirements are used. Rice bran, fish meal, soy meal, shrimp meal, silkworms, flour, beef liver and earthworms are frequently used to make these meals [21]. Alarmingly, Bangladesh uses the protein concentrate made from tannery solid wastes for organic fertilizers, poultry feed, and fish feed [22], which might contaminate industrial feeds with heavy metals. By eating shrimp, this heavy metal is eventually transferred to the human body. Neurotoxicity and carcinogenicity are typically the primary negative health impacts of exposure to these heavy metals, even at low concentrations [23].

Some studies have been conducted on trace metals concentration in aquatic elements e.g., water, sediments, fish etc. in some important rivers of Bangladesh. [16], [20], [24]. Studies found out that urban and industrial development increase the metal contamination in aquatic environment and organisms [13], [25]. In recent time, many industries have been established in and about Khulna city, and the number is continually increasing now-a-days. So, the amount of contaminated wastewater in adjacent rivers is increasing drastically. As a result, the increase in heavy metal concentration in aquatic animal might be increasing. It should be monitored continuously to ensure the heavy metal concentration in shrimp and crab, whether it is below safe level or not. To the best of our knowledge, no detailed study has been conducted on the trace metal concentration in shrimp and crab so far. So, metal toxicity data to calculate the risk assessment is very insufficient. Similarly, there is a shortage of detailed information to assess health risk for the shrimp and crab consumers in Bangladesh. Therefore, the present study aimed to find out the concentration of Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Al, and Fe in two mostly consumed shrimp and one crab species and to assess the human health risk due to consumption. In addition, the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health implications of the consumption of those were evaluated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Collection and preparation of samples

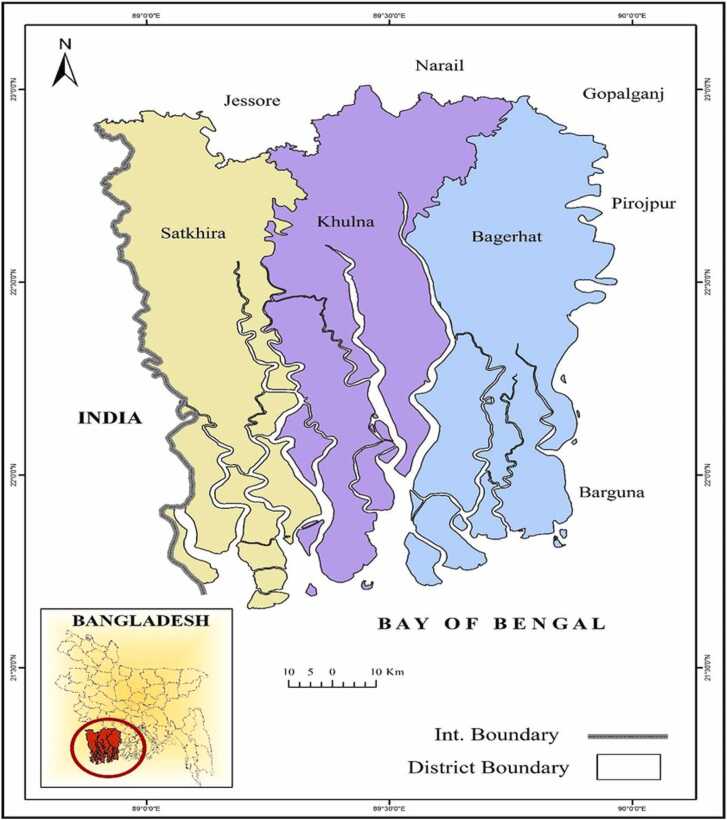

Two cultured shrimp species Macrobrachium rosenbergii and Metapenaeus monoceros, and a crab species (Scylla serrata) were collected from Khulna Division (Satkhira, Khulna, and Bagerhat district) of Bangladesh (Fig. 1). Total 315 samples (5 replicate samples of each species from each farm) were collected from seven different farms and from three districts. The study region was chosen because of the significant role it plays in the shrimp and prawn aquaculture industry as well as the export of frozen fishery products [26].

Fig. 1.

Sample collection area.

Shrimp and crab samples were collected and kept in an ice box to maintain a temperature of 4–5 ºC and delivered to the laboratory for analysis within 24 h. Samples were then washed thoroughly with running water, dried and stored at − 20 ºC until chemical analysis.

Using stainless steel scalpels, frozen shrimp samples were dissected at ∼ 25 ºC. Fresh weights (f.w.) were recorded together with the collection of edible tissues. Before use, all glassware for heavy metal analysis washed with detergent, rinsed in distilled water, steeped in 5% nitric acid for more than 24 h, rinsed with deionized water, and allowed to air-dry at ∼ 25 ºC.

2.2. Analysis of metals by ICP-OES

Concentrations of metals were analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (SN: P70407, PRODIGY 7, Teledyne Leeman Labs, USA) following the method used by Khan, Jeong [27] with little modification. Before analysis the shrimp and crab were thawed and 1 g sample was taken from each shrimp and crab. Samples were digested for 12 h with 25 mL of HNO3 (68%) and 2.0 mL of H2O2 (32%), acting as a catalyst, on a hot plate [28]. The temperature of the heating plate was ramped from 50 °C up to 160 °C. A roughly 5–7 mL of a colorless watery appearance indicates the end of digestion. After digestion the samples were cooled and filtered with the Whatman No. 42 filter paper. The filtrates were then dissolved and diluted with ultrapure deionized water to 50 mL. To quantify the concentration of Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Al, and Fe all digested samples and blanks were examined in triplicate.

Argon gas was initially used to torch the coil and high frequency electric current was then delivered to the work coil at the torch tube's tip to create plasma. Plasma was produced by ionizing argon gas using the electromagnetic field produced by the high frequency current in the torch tube [29]. The energy utilized in the excitation-emission of the sample came from the high electron density and temperature (10000 K) of this plasma. Through the little tube in the middle of the torch tube, solution samples were injected into the plasma in an atomized condition [29]. The wavelengths used for the detection and quantification of Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Al, and Fe were 226.502, 283.305, 324.754, 206.149, 213.856, 231.604, 228.812, 396.152, and 259.940 nm, respectively. The concentrations of metals in shrimp and crab were expressed as mg/kg fresh weight.

2.3. Estimated daily intake (EDI)

EDI was calculated by the method shown by [30] and expressed in mg/day. The average metal content of each sample was computed, then multiplied by the appropriate consumption rate to create an estimate of EDI [31]. The daily intake rate was determined by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

Where MC is the metal concentration in the shrimp and crab samples (mg/kg fw), and IR is the ingestion rate, which was taken as 49.5 g fw/day-person [32].

2.4. Target hazard quotient (THQ)

THQ is an estimation of the non-carcinogenic risk level due to heavy metals exposure. THQ was calculated by using Eq. (2) as per the standard assumption of USEPA Region III Risk-Based Concentration Table [33].

| (2) |

Where, EF represents exposure frequency (350 days/year), ED represents exposure duration (30 years for noncancer risk, as used, IR is the ingestion rate (49.5 g/day) [32], BW is the typical adult body weight of 70 kg, MC is the dry weight of heavy metal concentration in shrimp (mg/kg), and ATn is the typical average exposure time for non-carcinogens (EF × ED) (365 days/year X number of exposure years, assuming 30 years, 10, 950 days) [33], [34]. RfD is the oral reference dosage (mg/kg-day) of a certain metal to which the human population may be continually exposed over the course of their lives without an appreciable risk of deleterious effects. and the values of RfD used in this study were recommended by US EPA and other studies [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. If the THQ value is less than or equal to 1, it means that there is a low likelihood that the exposed population will face any long-term health risks. In contrast, if the THQ is greater than 1, there may be a health concern, necessitating the implementation of relevant actions and safety precautions [41].

2.5. Hazard index

The hazard index (HI) was expressed as the sum of the individual metal THQ values [36]. A HI < 1 is considered safe and HI > 1 is considered hazardous, and THQ (Cd) is the target hazard quotient for Cd intake, and so on.

2.6. Target cancer risk

The term "target cancer risk" (TR) was used to describe the escalating likelihood that a person may get cancer over the course of their lifetime as a result of exposure to a suspected carcinogen [42]. USEPA Region III Risk-Based Concentration Table provides the approach to assess TR [36].

| (3) |

Where ATc is the average period of carcinogens (365 days per year for 70 years), according to USEPA, and CPSo is the carcinogenic potency slope for the oral route (mg/kg bw/day) [36]. The values of CPSo for As, Pb, Cr and Ni were known from USPEA, hence TR values for these metal intakes were computed.

2.7. Data Analysis

One-way analysis of variance was used to look at the differences between the mean values that were statistically significant. Using the statistical program SPSS (SPSS 11.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), the multiple-comparison tests were performed using Tukey's honestly significant difference test. All measurements were carried out at least five times [43].

3. Results and discussion

The present study was conducted to determine the concentration of nine heavy metals, namely Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb), Copper (Cu), Chromium (Cr), Zinc (Zn), Nickel (Ni), Arsenic (As), Aluminium (Al), and Iron (Fe) associated human health risk from the consumption of two shrimp (Macrobrachium rosenbergii, Metapenaeus monoceros) and a crab (Scylla serrata) species. Among the shrimp and crab species, concentrations of the above-mentioned heavy metals were observed. Average concentration of heavy metals found in crustaceans are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentration of heavy metals (mg/kg f.w.) in shrimp and crab collected from Khulna, Bagerhat and Satkhira regions.

| Location | Species | Heavy Metal Concentration (mg/kg f.w.) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Pb | Cu | Cr | Zn | Ni | As | Al | Fe | ||

| Khulna | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 0.062 ± 0.012a | 0.088 ± 0.006ab | 0.019 ± 0.013a | 0.059 ± 0.014b | 0.178 ± 0.056b | 0.065 ± 0.019a | 0.104 ± 0.003a | 0.120 ± 0.057a | 0.034 ± 0.019a |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 0.060 ± 0.021a | 0.093 ± 0.002a | 0.016 ± 0.009a | 0.050 ± 0.008b | 0.127 ± 0.108b | 0.079 ± 0.021a | 0.112 ± 0.014a | 0.079 ± 0.064a | 0.034 ± 0.02a | |

| Scylla serrata | 0.058 ± 0.003a | 0.079 ± 0.002b | 0.031 ± 0.003a | 0.098 ± 0.007a | 0.548 ± 0.007a | 0.073 ± 0.038a | 0.108 ± 0.015a | 0.093 ± 0.059a | 0.058 ± 0.006a | |

| Bagerhat | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 0.057 ± 0.014a | 0.087 ± 0.008a | 0.019 ± 0.012b | 0.091 ± 0.029a | 0.215 ± 0.052b | 0.079 ± 0.028a | 0.115 ± 0.009a | 0.086 ± 0.033a | 0.045 ± 0.029a |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 0.062 ± 0.009a | 0.082 ± 0.007a | 0.008 ± 0.013b | 0.074 ± 0.01a | 0.124 ± 0.065b | 0.102 ± 0.035a | 0.113 ± 0.021a | 0.082 ± 0.056a | 0.033 ± 0.014a | |

| Scylla serrata | 0.057 ± 0.019a | 0.081 ± 0.006a | 0.056 ± 0.008a | 0.077 ± 0.000a | 0.474 ± 0.028a | 0.099 ± 0.01a | 0.128 ± 0.005a | 0.093 ± 0.019a | 0.074 ± 0.002a | |

| Satkhira | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 0.066 ± 0.017a | 0.091 ± 0.007a | 0.019 ± 0.012a | 0.087 ± 0.025a | 0.277 ± 0.104b | 0.089 ± 0.028a | 0.109 ± 0.019a | 0.087 ± 0.034a | 0.052 ± 0.007a |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 0.060 ± 0.009a | 0.080 ± 0.006a | 0.015 ± 0.013a | 0.057 ± 0.026a | 0.266 ± 0.114b | 0.089 ± 0.026a | 0.107 ± 0.004a | 0.108 ± 0.074a | 0.059 ± 0.031a | |

| Scylla serrata | 0.056 ± 0.011a | 0.086 ± 0.003a | 0.013 ± 0.012a | 0.092 ± 0.029a | 0.805 ± 0.235a | 0.051 ± 0.045a | 0.107 ± 0.022a | 0.118 ± 0.009a | 0.083 ± 0.004a | |

Data presented as mean ± Std, different letters in the same column within each location indicates significant difference.

3.1. Concentration of heavy metals

Heavy metal concentrations in shrimp and crab species were determined by ICP-OES and expressed as mg/kg. On a wet weight basis, the concentrations of every metal were calculated. A comparison of heavy metals (mg/kg) concentrations in shrimp and crab samples from previous studies has presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of heavy metals (mg kg−1) concentrations in shrimp and crab samples with results from other studies.

| Location | Cd | Pb | Cu | Cr | Zn | Ni | AS | Fe | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buriganga river, Bangladesh | 8.03–13.52 | 3.36–6.34 | 8.25–11.21 | [20] | |||||

| Buriganga river, Bangladesh | 1.50 | 0.51 | 575 | 2.50 | 195 | 0.60 | 1.20 | [78] | |

| Satkhira farm, Bangladesh |

0.60 × 10−1 | 0.96 | 0.20 | [40] | |||||

| Kalpakkam, India | 0.8–6.5 | 17.6–117.0 | [79] | ||||||

| Tumkur, India | 0.80 | 33 | 55 | 3 | 600 | [79] | |||

| Ganga, West Bengal, India | 0.60 × 10−2- 0.02 | 1.1–5.4 | 4.90–12.2 | [80] | |||||

| Ganga, Kolkata | 4.60 × 10−2 | 3.50 | 0.96 | 7.70 × 10−2 | 12.59 | [81] | |||

| St. Martins Island | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5 | 1 | 50 | 5 | [54] | ||

| Khulna division, Bangladesh | 5.60 × 10−2 − 6.57 × 10−2 | 7.91 × 10−2 − 9.28 × 10−2 | 0.82 × 10−2 − 5.56 × 10−2 | 5.00 × 10−2 − 9.84 × 10−2 | 12.68 × 10−2 − 80.52 × 10−2 | 5.15 × 10−2 − 10.23 × 10−2 | 10.38 × 10−2 − 12.80 × 10−2 | 3.28 × 10−2 − 8.334 × 10−2 | Present study for Shrimp and crab |

| Maximum level (mg/ kg wet weight) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 5 | 0.50 | 50 | 5 | [50], [54] |

3.1.1. Cadmium

At a minimum dose of 1 mg/kg, Cadmium (Cd) can cause chronic poisoning [44]. Fish should only have a Cd value of 0.05 mg/kg or less, according to FAO/WHO [45]. The standard for Cd in seafood set by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (ANHMRC) is 2.0 mg/kg [46]. The main sources of Cd contamination in marine species are the use of uncontrolled fertilizers, long-term discharge of untreated industrial wastes and the potential increase in Cd concentration in farm water. [40]. In the current study, Cd levels in samples of shrimp from various locations ranged from 5.7 × 10−2 to 6.6 × 10−2 mg/kg. The highest and lowest Cd concentrations were found in M. rosenbergii tissues from Satkhira (6.6 ×10−2 mg/kg) and Bagerhat (5.7 ×10−2) (mg/kg) regions, respectively (Table 1). However, lowest concentration of Cd was found in the crab samples from the Satkhira regions (5.6 ×10−2 mg/kg), whereas highest concentration was found from the Khulna regions (5.8 ×10−2 mg/kg) (Table 1). Cd levels in the chosen samples from all sites were found to be lower than the permitted limits [45]. Previous studies show that crustaceans in the Buriganga River have a high Cd content of 1.51 mg/kg, [47]. An earlier investigation revealed that the Cd levels in fish samples from the Bangshi River between two separate seasons ranged from 0.09 to 0.87 mg/kg [16], [40].

3.1.2. Lead

Lead (Pb) concentrations in shrimp tissues ranged from 8.0 × 10−2 to 9.3 × 10−2 mg/kg, with M. monoceros from Satkhira regions having the lowest concentration (8.0 ×10−2 mg/kg) and M. monoceros from Khulna regions having the highest concentration (9.3 ×10−2 mg/kg) (Table 1). Highest Pb concentration in the crab samples was found from Satkhira regions (8.6 ×10−2 mg/kg), while lowest Pb concentration was found in the Khulna regions 7.9 × 10−2 mg/kg (Table 1). These levels were well below the maximum allowable threshold (0.50 mg/kg) [48]. All shrimp and crab samples showed lower values than the suggested level. Studies showed that M. rosenbergii from the Buriganga river had Pb pollution of 0.51 mg/kg [38], [40]. Due to the bottom-dwelling nature of the M. monoceros and M. rosenbergii, these species constantly came into contact with sediments, thus sediment pollution might be a major contributing factor for Pb contamination. The discharge of industrial effluents from a range of companies, including poultry farms, oil refineries, textile manufacturers, and other sources can also cause Pb to enter rivers [40].

3.1.3. Copper

All living organisms require Copper (Cu) for appropriate growth and metabolism [49]. However, at large concentrations, Cu becomes poisonous. It has been reported that Cu concentrations should not exceed 5 mg/kg in the food product [50]. In the examined samples, concentration of Cu was found comparatively at a lower amount. Cu values in the shrimp samples ranged from 0.8 × 10−2 to 1.9 × 10−2 mg/kg, with M. rosenbergii having the maximum concentration of 1.9 × 10−2 mg/kg from the Khulna and Satkhira regions, and M. monoceros having the minimum concentration of 0.8 × 10−2 mg/kg from the Bagerhat regions (Table 1). Thus, the Cu contents in the experimental specimens were lower than the recommended levels. The enrichment of Cu in macrobenthic fauna might be through Cu input in water and sediments from nearby industry.

3.1.4. Chromium

The maximum tolerable concentration of Chromium (Cr) varies between 0.5 [50] and 1.0 mg/kg [51]. The crustacean samples included in the preliminary analysis had Cr values ranging from 5.0 × 10−2 to 9.8 × 10−2 mg/kg. Highest Cr content was found in M. rosenbergii from Bagerhat (9.1 ×10−2 mg/kg), whereas, lowest concentration was found in M. monoceros from Khulna district5.0 × 10−2 mg/kg (Table 1). Highest and lowest levels of Cr was found in S. serrata from Khulna district (9.8 ×10−2 mg/kg) and Bagerhat districts (7.7 ×10−2 mg/kg) respectively (Table 1). In the current study, we found a lower level of Cr than those reported in other studies in shrimp and mollusks (bivalve) [52]. Study findings imply that Cr pollution exceed the safe limit of FAO's acceptable guideline for Cr concentration in shrimp was exceeded in an Indian river [53].

3.1.5. Zinc

Zinc (Zn), as a cofactor for roughly 300 enzymes for all marine organisms, is a vital mineral for both humans and animals [54]. Zn is a constituent of various enzymes and is crucial for a number of biological processes that need to be maintained at quite high levels. Zn toxicity resulting from excessive consumption may lead to electrolyte imbalance, nausea, and anemia [55]. The highest and lowest concentration of Zn was found in M. rosenbergii (27.7 ×10−2 mg/kg) and M. monoceros (12.4 ×10−2 mg/kg) from Satkhira and Bagerhat respectively. On the other hand, the maximum amount of Zn was 80.5 × 10−2 mg/kg in S. serrata from the Satkhira area, while the lowest amount was 47.4 × 10−2 mg/kg from the Bagerhat area (Table 1). The FAO's recommended maximum limit for zinc is 30 mg/kg [56]. All shrimp and crab samples had Zn amounts below the recommended levels. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is no risk to human health from this metal.

3.1.6. Nickel

Ni levels in the shrimp samples ranged from 6.5 × 10−2 to 10.2 × 10−2 mg/kg. M. monoceros, obtained from the Bagerhat regions, had the highest concentration (10.2 ×10−2 mg/kg), while M. rosenbergii, collected from the Khulna regions, had the minimum concentration (6.5 ×10−2 mg/kg). S. serrata from Satkhira and Bagerhat district had the lowest concentration of 5.1 × 10−2 mg/kg and highest concentration of 9.9 × 10−2 mg/kg Ni, respectively (Table 1). The WHO maximum recommended level of Ni is 0.2 mg/kg [57]. No Ni concentrations in all samples exceeded the allowable limit.

3.1.7. Arsenic

Both organic and inorganic types of arsenic (As) can be found in our diet, however inorganic As is more harmful than organic As. The types of As that are present are challenging to accurately assess. It is believed that 10% of all arsenic is inorganic [58]. S. serrata from the Bagerhat region had the highest concentration of As (12.80 ×10−2 mg/kg), while from the Satkhira region had the lowest value (10.72 ×10−2 mg/kg). The maximum As concentration was found in M. rosenbergii from Khulna regions (10.4 ×10−2 mg/kg), while the lowest concentration was found from Bagerhat of 11.5 × 10−2 mg/kg (Table 1). The findings revealed that the shrimp and crab had comparatively higher concentrations of As than other metal tested. The maximum permitted concentration of arsenic in crustaceans is 5 mg/kg [50], [54]. Our findings showed that the As concentration was below the safe level. Recent studies, however, contend that at very low quantities, As disrupts the endocrine system. Chronic exposure to inorganic arsenic may have negative consequences on the liver, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, skin, hematological system, cardiovascular system, neurological system, and skin [59]. Acute high level As exposure can also cause vomiting, diarrhea, anemia, liver damage, and even death. Long-term exposure is thought to increase the risk of developing cancer, hypertension, some types of diabetes, and skin disease [60].

3.1.8. Aluminum

In most cases, Aluminum (Al) exposure through the mouth is safe. Some studies indicate that persons who are exposed to high quantities of aluminum may get Alzheimer's disease [61]. The M. monoceros from the Bagerhat region had the lowest concentration of Al (8.2 ×10−2 mg/kg), whereas M. rosenbergii from Khulna region had the highest concentration of Al (12.0 ×10−2 mg/kg). The highest and lowest Al concentration in S. serrata was found in Satkhira regions (11.8 ×10−2 mg/kg), and Khulna regions (9.3 ×10−2 mg/kg), respectively (Table 1). Previous research has connected neurotoxicity (bad health effects on the central or peripheral nervous system or both), [61] Alzheimer's disease, and breast cancer to regular exposure to high quantities of Al.

3.1.9. Iron

The human body requires iron for proper functioning. Suggested level of heavy metal concentration for Iron (Fe) in white shrimp is 0.50 mg/kg [62]. It functions as an electron transporter inside cells, a component of important protein frameworks in various tissues, and a carrier of oxygen from the lungs to the tissues through red platelet hemoglobin. S. serrata from Satkhira had the highest content of Fe (8.3 ×10−2 mg/kg), whereas from Bagerhat had the lowest concentration (7.4 ×10−2 mg/kg). M. monoceros from Bagerhat had the lowest concentration of 3.3 × 10−2 mg/kg and from Satkhira had the highest concentration of 5.9 × 10−2 mg/kg (Table 1). The study's finding is far safe to the recommended level. The gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa can be severely damaged by Fe ingestion, which can produce nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, hematemesis, and diarrhea. Patients may also experience hypovolemia due to considerable fluid and blood loss.

3.2. Estimated Daily Intake (EDI)

Estimated daily intake (EDI) of trace metals in shrimp and crab has been evaluated in this study. Table 3 lists the EDI of few hazardous heavy metals from ingestion of crustaceans by Bangladeshi adults typically living in the coastal area. EDI to RfD ratio is a significant measure of health risk. RfD is the estimation of the amount of daily exposure to which the general population might be continuously exposed over the course of a lifetime without a significant risk of adverse consequences [63]. New York State Department of Health claims if the derived heavy metal's EDI to RfD ratio is equal to or less than the RfD, the risk is small [64]. However if the ratio is > 1–5, > 5–10, and > 10 x the Rfd, the risk is low, moderate, and significant, respectively [63]. As a result, EDI can be used as a benchmark to assess the possible health effects of the chemical at various levels. The likelihood of negative consequences in a human population rises as the frequency and/or size of exposures that exceed the RfD [54].

Table 3.

Estimated daily intake (EDI) of Heavy metals through consumption of shrimp and crab from Khulna, Satkhira and Bagerhat regions.

| Location | Variety | Estimated daily intake (EDI) (mg/person/ day) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Pb | Cu | Cr | Zn | Ni | As | Al | Fe | ||

| Khulna | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 3.05 × 10−3 | 4.38 × 10−3 | 0.94 × 10−3 | 2.93 × 10−3 | 8.81 × 10−3 | 3.20 × 10−3 | 5.14 × 10−3 | 5.97 × 10−3 | 1.68 × 10−3 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 2.98 × 10−3 | 4.59 × 10−3 | 0.81 × 10−3 | 2.48 × 10−3 | 6.28 × 10−3 | 3.95 × 10−3 | 5.53 × 10−3 | 3.89 × 10−3 | 1.68 × 10−3 | |

| Scylla serrata | 2.88 × 10−3 | 3.92 × 10−3 | 1.52 × 10−3 | 4.87 × 10−3 | 27.14 × 10−3 | 3.62 × 10−3 | 5.36 × 10−3 | 4.59 × 10−3 | 2.86 × 10−3 | |

| Bagerhat | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 2.83 × 10−3 | 4.31 × 10−3 | 0.99 × 10−3 | 4.52 × 10−3 | 10.64 × 10−3 | 3.96 × 10−3 | 5.72 × 10−3 | 4.28 × 10−3 | 2.24 × 10−3 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 3.08 × 10−3 | 4.08 × 10−3 | 0.41 × 10−3 | 3.66 × 10−3 | 6.12 × 10−3 | 5.06 × 10−3 | 5.61 × 10−3 | 4.04 × 10−3 | 1.62 × 10−3 | |

| Scylla serrata | 2.83 × 10−3 | 3.99 × 10−3 | 2.75 × 10−3 | 3.81 × 10−3 | 23.48 × 10−3 | 4.90 × 10−3 | 6.34 × 10−3 | 4.62 × 10−3 | 3.69 × 10−3 | |

| Satkhira | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 3.25 × 10−3 | 4.48 × 10−3 | 0.98 × 10−3 | 4.28 × 10−3 | 13.71 × 10−3 | 4.39 × 10−3 | 5.39 × 10−3 | 4.31 × 10−3 | 2.59 × 10−3 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 2.98 × 10−3 | 3.97 × 10−3 | 0.73 × 10−3 | 2.82 × 10−3 | 13.17 × 10−3 | 4.39 × 10−3 | 5.29 × 10−3 | 5.36 × 10−3 | 2.96 × 10−3 | |

| Scylla serrata | 2.78 × 10−3 | 4.28 × 10−3 | 0.66 × 10−3 | 4.57 × 10−3 | 39.86 × 10−3 | 2.55 × 10−3 | 5.31 × 10−3 | 5.82 × 10−3 | 4.13 × 10−3 | |

However, we have not reached an absolute conclusion that all doses below the RfD are "acceptable" (or without risk) and all doses above the RfD are "unacceptable" (or cause adverse effects) [54], [65]. The daily consumption of a heavy metal determines how harmful it is to people [66]. The average EDIs of all tested metals in the two species of shrimp and one species of crab were lower than the tolerable daily intake limit that indicates that the average consumption of the species in the coastal area would not result in health risk (Table 3). Although the shrimp and crab species examined for this study were deemed acceptable for everyday human consumption, they may pose health hazards if consumed continuously and excessively over 30 years.

3.3. Health risk assessment

Consuming shrimp and crab could expose human to heavy metals in a way that negatively impacts human's health. Therefore, a health risk assessment is unquestionably required for people who regularly consume shrimp and crab.

3.3.1. Target hazard quotient and hazard index

Table 4 provides estimated target hazard quotients (THQ) and hazard index (HI) for Cd, Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Al, and Fe consuming from Macrobrachium rosenbergii, Metapenaeus monoceros, and Scylla serrata cultivated at Khulna Division (Satkhira, Khulna, and Bagerhat district) of Bangladesh. USEPA states that ≤ 1 is the permissible value for THQ [33]. The outcome revealed that each metal's THQ value was less than 1, indicating that consuming shrimp and crab would not expose people to any non-carcinogenic health risks if they only intake one heavy metals individually. Moreover, all metals taken into account together had HI less than the permissible level of 1 for shrimp and crab.

Table 4.

Target hazard quotient (THQ) for individual metals and their hazard index (HI) from consumption of Shrimp and crab from Khulna, Satkhira and Bagerhat regions.

| Location | Variety | Target Hazard Quotient (THQ) |

Hazard Index (HI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Pb | Cu | Cr | Zn | Ni | As | Al | Fe | |||

| Khulna | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 4.18 × 10−2 | 1.49 × 10−2 | 3.23 × 10−4 | 1.34 × 10−2 | 4.02 × 10−4 | 2.19 × 10−3 | 2.35 × 10−1 | 8.17 × 10−5 | 3.28 × 10−5 | 0.01 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 4.08 × 10−2 | 1.57 × 10−2 | 2.79 × 10−4 | 1.13 × 10−2 | 2.87 × 10−4 | 2.71 × 10−3 | 2.53 × 10−1 | 5.34 × 10−5 | 3.29 × 10−5 | 0.01 | |

| Scylla serrata | 3.95 × 10−2 | 1.34 × 10−2 | 5.20 × 10−4 | 2.22 × 10−2 | 1.24 × 10−3 | 2.48 × 10−3 | 2.45 × 10−1 | 6.30 × 10−5 | 5.59 × 10−5 | 0.02 | |

| Bagerhat | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 3.88 × 10−2 | 1.47 × 10−2 | 3.38 × 10−4 | 2.06 × 10−2 | 4.86 × 10−4 | 2.71 × 10−3 | 2.61 × 10−1 | 5.86 × 10−5 | 4.39 × 10−5 | 0.01 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 4.22 × 10−2 | 1.39 × 10−2 | 1.39 × 10−4 | 1.67 × 10−2 | 2.80 × 10−4 | 3.47 × 10−3 | 2.56 × 10−1 | 5.53 × 10−5 | 3.17 × 10−5 | 0.01 | |

| Scylla serrata | 3.88 × 10−2 | 1.37 × 10−2 | 9.43 × 10−4 | 1.74 × 10−2 | 1.07 × 10−3 | 3.36 × 10−3 | 2.89 × 10−1 | 6.33 × 10−5 | 7.21 × 10−5 | 0.02 | |

| Satkhira | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 4.45 × 10−2 | 1.53 × 10−2 | 3.37 × 10−4 | 1.96 × 10−2 | 6.26 × 10−4 | 3.01 × 10−3 | 2.46 × 10−1 | 5.90 × 10−5 | 5.07 × 10−5 | 0.01 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 4.08 × 10−2 | 1.36 × 10−2 | 2.49 × 10−4 | 1.29 × 10−2 | 6.02 × 10−4 | 3.01 × 10−3 | 2.41 × 10−1 | 7.34 × 10−5 | 5.80 × 10−5 | 0.01 | |

| Scylla serrata | 3.80 × 10−2 | 1.47 × 10−2 | 2.25 × 10−4 | 2.09 × 10−2 | 1.82 × 10−3 | 1.75 × 10−3 | 2.42 × 10−1 | 7.97 × 10−5 | 8.08 × 10−5 | 0.03 | |

3.3.2. Target cancer risk (TR)

According to the USFDA [67], the majority (around 90%) of As exposure occurs through seafood. As exposure has been linked to a number of health effects. The inorganic As is regarded as a carcinogen and has been linked to lung, skin, liver, gall bladder, and skin cancers. Kidney failure, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disorders are some of harmful effects of cadmium's toxicity. Pregnant women's Cd intoxication has been linked to shorter pregnancies, smaller babies, and more lately, children's immune and/or endocrine system abnormalities [68]. The major harmful effect of Pb exposure has been linked to delay in neurobehavioral development [69]. The neurological system's efficiency may suffer with prolonged exposure. EPA reports that heavy metal may potentially cause cancer in humans [70]. Moreover, Pb exposure can cause significant damage to the brain, liver, and kidneys as well as eventual mortality [71]. In addition, high exposure of Pb in men can damage the sperm-producing organs [72].

For As, Pb, Cr, and Ni a carcinogenic potency slope factors are available. As is categorized as an established carcinogen (USEPA group A) and based on animal studies, Pb can also be categorized as probable carcinogen (USEPA group B2) [73]. Table 5 shows the TRs for As, Pb, Cr, and Ni in adults from crustacean’s ingestion exposure. The TR values for As, Pb, Cr, and Ni ranged from 4.53 × 10−5 to 5.58 × 10−5, 1.96 × 10−7 to 2.29 × 10−7, 8.60 × 10−6 to 1.43 × 10−5, and 2.54 × 10−5 to 5.05 × 10−5 respectively in shrimp and crab (Table 5). Cancer risks below 10−6 are typically regarded as insignificant, those above 10−4 are generally seen as unacceptable, and those that fall between 10−6 and 10−4 are generally regarded as allowable [33], [74]. For all shrimp and crab samples, the TR for As, Pb, Cr, and Ni was between 10−7and 10−5. Additional sources of metal exposure, such as consuming other foods (such as ground water, wheat, rice, pulses, meat, and eggs), inhaling dust, and so on, could not be considered in this study. Moreover, Mercury (Hg) contamination can be a potential health threat nowadays [75], [76]. Acute exposure to this heavy metal can cause insomnia, neuromuscular changes, headaches and changes in nerve responses [77], therefore, these need to be considered in future study.

Table 5.

Target cancer risk (TR) for heavy metals from consumption of shrimp and crabs from Khulna, Satkhira and Bagerhat regions.

| Location | Variety | Target cancer risk (TR) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | Pb | Cr | Ni | ||

| Khulna | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 4.53 × 10−5 | 2.18 × 10−7 | 8.60 × 10−6 | 3.19 × 10−5 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 4.87 × 10−5 | 2.29 × 10−7 | 7.27 × 10−6 | 3.95 × 10−5 | |

| Scylla serrata | 4.72 × 10−5 | 1.96 × 10−7 | 1.43 × 10−5 | 3.61 × 10−5 | |

| Bagerhat | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 5.03 × 10−5 | 2.15 × 10−7 | 1.33 × 10−5 | 3.95 × 10−5 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 4.94 × 10−5 | 2.03 × 10−7 | 1.07 × 10−5 | 5.05 × 10−5 | |

| Scylla serrata | 5.58 × 10−5 | 1.99 × 10−7 | 1.12 × 10−5 | 4.89 × 10−5 | |

| Satkhira | Macrobrachium rosenbergii | 4.75 × 10−5 | 2.24 × 10−7 | 1.26 × 10−5 | 4.38 × 10−5 |

| Metapenaeus monoceros | 4.66 × 10−5 | 1.98 × 10−7 | 8.28 × 10−6 | 4.38 × 10−5 | |

| Scylla serrata | 4.67 × 10−5 | 2.13 × 10−7 | 1.34 × 10−5 | 2.54 × 10−5 | |

4. Conclusions

This study was conducted to learn more about the levels of heavy metals in shrimp and crab from Bangladesh's southern-western region. Cadmium had absolutely distinct bioaccumulation resulted in higher average concentration in crab than in shrimp samples. Being a favored cuisine in this area, shrimp consumption may cause chronic illnesses including renal failure and other chronic diseases owing to excessive consumption if crustaceans contain significantly higher amount of heavy metals. However, the investigation revealed a minimum heavy metal content which is below the maximum recommended level. Our research provides a new perspective on eating shrimp and crab from these areas that poses nearly no health danger. Long-term cancer risk is negligible for people who regularly consume shrimps and crabs with lower concentrations of heavy metals than that identified in the current study.

Ethical Approval

Appropriate ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Approval committee of Jashore University of Science and Technology.

Declarations

All authors have read, understood, and have complied as applicable with the statement on “Ethical responsibilities of authors” as found in the Instruction of Authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shahjalal University of Science and Technology’s Research Centre, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shafi Ahmed: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Supervision. Md. Farid Uddin: Formal Analysis; Writing – Original Draft Preparation. Md. Sakib Hossain: Formal Analysis; Writing – Review & Editing; Investigation; Visualization. Abdullah Jubair: Writing – Review & Editing; Investigation; Visualization. Md. Nahidul Islam: Methodology; Software; Validation; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Writing – Review & Editing; Supervision. Mizanur Rahman: Conceptualization; Writing – Review & Editing; Supervision; Project Administration; Funding Acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Contributor Information

Md. Nahidul Islam, Email: nahidul.islam@bsmrau.edu.bd.

Mizanur Rahman, Email: mizan-fet@sust.edu.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Copat C., Bella F., Castaing M., Fallico R., Sciacca S., Ferrante M. Heavy metals concentrations in fish from Sicily (Mediterranean Sea) and evaluation of possible health risks to consumers. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012;88(1):78–83. doi: 10.1007/s00128-011-0433-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halim S. Marginalization or empowerment? Women’s involvement in shrimp cultivation and shrimp processing plants in Bangladesh. Women, Gend. Discrim. 2004:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo J.L. Omega-3 fatty acids and the benefits of fish consumption: is all that glitters gold? Environ. Int. 2007;33(7):993–998. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martorell I., Perelló G., Martí-Cid R., Llobet J.M., Castell V., Domingo J.L. Human exposure to arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead from foods in Catalonia, Spain: temporal trend. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010;142(3):309–322. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8787-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amirah M., Afiza A., Faizal W., Nurliyana M., Laili S. Human health risk assessment of metal contamination through consumption of fish. J. Environ. Pollut. Hum. Health. 2013;1(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farmer J.G., Broadway A., Cave M.R., Wragg J., Fordyce F.M., Graham M.C., Ngwenya B.T., Bewley R.J.F. A lead isotopic study of the human bioaccessibility of lead in urban soils from Glasgow, Scotland. Sci. Total Environ. 2011;409(23):4958–4965. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashempour-Baltork F., Hosseini H., Houshiarrad A., Esmaeili M. Contamination of foods with arsenic and mercury in Iran: a comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26(25):25399–25413. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashempour-Baltork F., Jannat B., Tajdar-Oranj B., Aminzare M., Sahebi H., Alizadeh A.M., Hosseini H. A comprehensive systematic review and health risk assessment of potentially toxic element intakes via fish consumption in Iran. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023;249 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaishankar M., Tseten T., Anbalagan N., Mathew B.B., Beeregowda K.N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Inter. Toxicol. 2014;7(2):60–72. doi: 10.2478/intox-2014-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gümgüm B., ünlü E., Tez Z., Gülsün Z. Heavy metal pollution in water, sediment and fish from the Tigris River in Turkey. Chemosphere. 1994;29(1):111–116. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A. Nargis, A.K. Jhumur, M.E. Haque, M.N. Islam, A. Habib, and M. Cai, Human health risk assessment of toxic elements in fish species collected from the river Buriganga, Bangladesh, Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal. (2019).

- 12.Saha N., Zaman M. Evaluation of possible health risks of heavy metals by consumption of foodstuffs available in the central market of Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013;185(5):3867–3878. doi: 10.1007/s10661-012-2835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam M.S., Ahmed M.K., Habibullah-Al-Mamun M. Determination of heavy metals in fish and vegetables in Bangladesh and health Implications. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess.: Int. J. 2014;21(4):986–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghaedi M., Shokrollahi A., Kianfar A.H., Mirsadeghi A.S., Pourfarokhi A., Soylak M. The determination of some heavy metals in food samples by flame atomic absorption spectrometry after their separation-preconcentration on bis salicyl aldehyde, 1,3 propan diimine (BSPDI) loaded on activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008;154(1–3):128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bervoets L., Blust R. Metal concentrations in water, sediment and gudgeon (Gobio gobio) from a pollution gradient: relationship with fish condition factor. Environ. Pollut. 2003;126(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(03)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman M.S., Molla A.H., Saha N., Rahman A. Study on heavy metals levels and its risk assessment in some edible fishes from Bangshi River, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Food Chem. 2012;134(4):1847–1854. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ammann A.A. Speciation of heavy metals in environmental water by ion chromatography coupled to ICP–MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2001;372(3):448–452. doi: 10.1007/s00216-001-1115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahunsi S., Oranusi S. Acute toxicity of synyhetic resin effluent to African Catfish, Clarias gariepinus [BURCHELL, 1822] Am. J. Food Nutr. 2012;2(2):42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi Y., Yang Z., Zhang S. Ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in sediment and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in fishes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River basin. Environ. Pollut. 2011;159(10):2575–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.M. Ahmad, S. Islam, S. Rahman, M. Haque, and M. Islam, Heavy metals in water, sediment and some fishes of Buriganga River, Bangladesh, (2010).

- 21.M. Asaduzzaman, Y. Yang, M. Wahab, J.S. Diana, and Z. Ahmed. Farming system of giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii in Bangladesh: a combination of tradition and technology. in Proceeding of the WAS conference (AQUA 2006) held on. 2006.

- 22.Hossain A.M., Monir T., Ul-Haque A.R., Kazi M.A.I., Islam M.S., Elahi S.F. Heavy metal concentration in tannery solid wastes used as poultry feed and the ecotoxicological consequences. Bangladesh J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2007;42(4):397–416. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jomova K., Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology 283(2-3) 2011:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islam M.S., Ahmed M.K., Habibullah-Al-Mamun M., Hoque M.F. Preliminary assessment of heavy metal contamination in surface sediments from a river in Bangladesh. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014;73(4):1837–1848. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao Y., Yuan Z., Xiaona H., Wei M. Distribution and bioaccumulation of heavy metals in aquatic organisms of different trophic levels and potential health risk assessment from Taihu lake, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012;81:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do Fisheries, National Fish Week 2011 Compendium (in Bengali), Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Animal Resources, Dhaka, Bangladesh. (2011) 63–66.

- 27.Khan N., Jeong I.S., Hwang I.M., Kim J.S., Choi S.H., Nho E.Y., Choi J.Y., Kwak B.-M., Ahn J.-H., Yoon T., Kim K.S. Method validation for simultaneous determination of chromium, molybdenum and selenium in infant formulas by ICP-OES and ICP-MS. Food Chem. 2013;141(4):3566–3570. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habte G., Choi J.Y., Nho E.Y., Oh S.Y., Khan N., Choi H., Park K.S., Kim K.S. Determination of toxic heavy metal levels in commonly consumed species of shrimp and shellfish using ICP-MS/OES. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015;24(1):373–378. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh S., Prasanna V.L., Sowjanya B., Srivani P., Alagaraja M., Banji D. Inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy: a review, Asian J. Pharm. Ana. 2013;3(1):24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ullah A.K.M.A., Maksud M.A., Khan S.R., Lutfa L.N., Quraishi S.B. Dietary intake of heavy metals from eight highly consumed species of cultured fish and possible human health risk implications in Bangladesh. Toxicol. Rep. 2017;4:574–579. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed M.K., Shaheen N., Islam M.S., Habibullah-al-Mamun M., Islam S., Mohiduzzaman M., Bhattacharjee L. Dietary intake of trace elements from highly consumed cultured fish (Labeo rohita, Pangasius pangasius and Oreochromis mossambicus) and human health risk implications in Bangladesh. Chemosphere. 2015;128:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistical B.B.S. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Planning; Dhaka: 2015. Pocketbook Bangladesh, 2015, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- 33.USEPA, Regional Screening Level (RSL) Summary Table: November 2011 http://www.epa.gv/iris/. (2011), United States Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC, USA.

- 34.Peycheva K., Panayotova V., Merdzhanova A., Stancheva R. Estimation of THQ and potential health risk for metals by comsumption of some black sea marine fishes and mussels in Bulgaria. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2019;51:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 35.USEPA, Regional Screening Level (RSL) Summary Table (TR= 1E-06, HQ= 1): http://www.epa.gv/iris/. (2016), United States Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC, USA.

- 36.USEPA, Regional Screening Level (RSL) Summary Table (TR=1E-06, HQ=0.1): November 2022 http://www.epa.gv/iris/. (2022), United States Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC, USA.

- 37.Yi Y., Tang C., Yi T., Yang Z., Zhang S. Health risk assessment of heavy metals in fish and accumulation patterns in food web in the upper Yangtze River, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017;145:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed M.K., Baki M.A., Islam M.S., Kundu G.K., Habibullah-Al-Mamun M., Sarkar S.K., Hossain M.M. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in tropical fish and shellfish collected from the river Buriganga, Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22(20):15880–15890. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4813-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogdanović T., Ujević I., Sedak M., Listeš E., Šimat V., Petričević S., Poljak V. As, Cd, Hg and Pb in four edible shellfish species from breeding and harvesting areas along the eastern Adriatic Coast, Croatia. Food Chem. 2014;146:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkar T., Alam M.M., Parvin N., Fardous Z., Chowdhury A.Z., Hossain S., Haque M., Biswas N. Assessment of heavy metals contamination and human health risk in shrimp collected from different farms and rivers at Khulna-Satkhira region, Bangladesh. Toxicol. Rep. 2016;3:346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X., Sato T., Xing B., Tao S. Health risks of heavy metals to the general public in Tianjin, China via consumption of vegetables and fish. Sci. Total Environ. 2005;350(1–3):28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamunda C., Mathuthu M., Madhuku M. Health risk assessment of heavy metals in soils from Witwatersrand Gold Mining Basin, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13(7):663. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng M., Xu B., Islam M.N., Zhou C., Wei B., Wang B., Ma H., Chang L. Individual and synergistic effect of multi-frequency ultrasound and electro-infrared pretreatments on polyphenol accumulation and drying characteristics of edible roses. Food Res. Int. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roels H.A., Lauwerys R.R., Buchet J.-P., Bernard A., Chettle D.R., Harvey T.C., Al-Haddad I.K. In vivo measurement of liver and kidney cadmium in workers exposed to this metal: Its significance with respect to cadmium in blood and urine. Environ. Res. 1981;26(1):217–240. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(81)90199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.FAO, W.H. Organization, and W.E.C.o.F. Additives, Evaluation of certain contaminants in food: eighty-third report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. 2017: World Health Organization.

- 46.Plaskett D., Potter I.C. Heavy metal concentrations in the muscle tissue of 12 species of teleost from Cockburn Sound, Western Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1979;30(5):607. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed M.K., Parvin E., Islam M.M., Akter M.S., Khan S., Al-Mamun M.H. Lead- and cadmium-induced histopathological changes in gill, kidney and liver tissue of freshwater climbing perchAnabas testudineus(Bloch, 1792) Chem. Ecol. 2014;30(6):532–540. [Google Scholar]

- 48.F. Joint, W.E.C.o.F. Additives, and W.H. Organization, Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants: thirty-third report of the Joint FAO. 1989: World Health Organization.

- 49.R. Eisler, Copper hazards to fish, wildlife, and invertebrates: a synoptic review. 1998: US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey.

- 50.Commission E. Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs . J. Eur. Union. 2006;364:5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 51.F. Joint, Limit test for heavy metals in food additive specifications: Explanatory note. (2002).

- 52.Ahmed M., Kundu G., Al-Mamun M., Sarkar S., Akter M., Khan M. Chromium (VI) induced acute toxicity and genotoxicity in freshwater stinging catfish, Heteropneustes fossilis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013;92:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giri S., Singh A.K. Assessment of human health risk for heavy metals in fish and shrimp collected from Subarnarekha River, India. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2014;24(5):429–449. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2013.857391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baki M.A., Hossain M.M., Akter J., Quraishi S.B., Shojib M.F.H., Ullah A.A., Khan M.F. Concentration of heavy metals in seafood (fishes, shrimp, lobster and crabs) and human health assessment in Saint Martin Island, Bangladesh. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;159:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prasad K., Saradhi P.P., Sharmila P. Concerted action of antioxidant enzymes and curtailed growth under zinc toxicity in Brassica juncea. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1999;42(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 56.FAO, Compilation of legal limits for hazardous substances in fish and fishery products., Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. Fishery circular No. 464, 5–100. (1983).

- 57.Pennington J.A.T., Schoen S.A., Salmon G.D., Young B., Johnson R.D., Marts R.W. Composition of core foods of the U.S. food supply, 1982-1991: II. Calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1995;8(2):129–169. [Google Scholar]

- 58.M.A. Adams, Guidance document for arsenic in shellfish, (1993).

- 59.Ratnaike R.N. Acute and chronic arsenic toxicity. Postgrad. Med. J. 2003;79(933):391–396. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.933.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centeno J.A., Tseng C.-H., Van der Voet G.B., Finkelman R.B. Global impacts of geogenic arsenic: a medical geology research case. Ambio. 2007:78–81. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[78:giogaa]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flaten T.P. Aluminium as a risk factor in Alzheimer’s disease, with emphasis on drinking water. Brain Res. Bull. 2001;55(2):187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.A. CODEX and T.F.O. INTERGOVERNMENTAL, Joint FAO/WHO Food Standard Programme Codex Alimentarius Commission Twenty-Fourth Session Geneva, 2–7 July 2001, Codex. (2001).

- 63.Dhar P.K., Naznin A., Hossain M.S., Hasan M. Toxic element profile of ice cream in Bangladesh: a health risk assessment study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021;193(7):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10661-021-09207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.N. DOH, Hopewell precision area contamination: Appendix C-NYS DOH, Procedure for evaluating potential health risks for contaminants of concern. Available at: http://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/investigations/hopewell/appendc.html. (2007).

- 65.E. IRIS, Environmental protection agency, integrated risk information system, Sist. Integr. Inf. (2007).

- 66.Singh A., Sharma R.K., Agrawal M., Marshall F.M. Risk assessment of heavy metal toxicity through contaminated vegetables from waste water irrigated area of Varanasi, India. Trop. Ecol. 2010;51(2):375–387. [Google Scholar]

- 67.USFDA, Guidance document for arsenic in shellfish. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of Seafood (HFS-416), Washington, DC. (1993).

- 68.Schoeters G., Den Hond E., Zuurbier M., Naginiene R., Van Den Hazel P., Stilianakis N., Ronchetti R., Koppe J. Cadmium and children: exposure and health effects. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(0):50–54. doi: 10.1080/08035320600886232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castoldi A.F., Coccini T., Manzo L. Neurotoxic and molecular effects of methylmercury in humans. Rev. Environ. Health. 2003;18(1) doi: 10.1515/reveh.2003.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kamunda C., Mathuthu M., Madhuku M. Potential human risk of dissolved heavy metals in gold mine waters of Gauteng Province, South Africa. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2018;10(6):56–63. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee K.-g, Kweon H., Yeo J.-h, Woo S., Han S., Kim J.-H. Characterization of tyrosine-rich Antheraea pernyi silk fibroin hydrolysate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011;48(1):223–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin S., Griswold W. Human health effects of heavy metals. Environmen-tal science and technology briefs for citizens, Center for Hazardous Substance. Res., Kans. State Univ. 2009;15 [Google Scholar]

- 73.P. Fenner-Crisp, Health Effects Division, Office of Pesticide Programs, US Environmental Protection Agency, 401 M Street, SW, Washington, DC 20460 USA, Risk Assessment in Chemical Carcinogenesis. (1991) 149.

- 74.Pan L., Fang G., Wang Y., Wang L., Su B., Li D., Xiang B. Potentially toxic element pollution levels and risk assessment of soils and sediments in the upstream river, Miyun Reservoir, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(11):2364. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang Y., Habibullah-Al-Mamun M., Han J., Wang L., Zhu Y., Xu X., Li N., Qiu G. Total mercury and methylmercury in rice: Exposure and health implications in Bangladesh. Environ. Pollut. 2020;265 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rakib M.R.J., Jolly Y., Enyoh C.E., Khandaker M.U., Hossain M.B., Akther S., Alsubaie A., Almalki A.S., Bradley D. Levels and health risk assessment of heavy metals in dried fish consumed in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):14642. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93989-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mahurpawar M. Effects of heavy metals on human health. Int J. Res Grant. 2015;530:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ahmed M., Baki M.A., Islam M., Kundu G.K., Habibullah-Al-Mamun M., Sarkar S.K., Hossain M. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in tropical fish and shellfish collected from the river Buriganga, Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22(20):15880–15890. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4813-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biswas S., Prabhu R.K., Hussain K.J., Selvanayagam M., Satpathy K.K. Heavy metals concentration in edible fishes from coastal region of Kalpakkam, southeastern part of India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012;184(8):5097–5104. doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2325-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhattacharya P., Samal A., Majumdar J., Santra S. Arsenic contamination in rice, wheat, pulses, and vegetables: a study in an arsenic affected area of West Bengal, India. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2010;213(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aktar M., Sengupta D., Chowdhury A. Occurrence of heavy metals in fish: a study for impact assessment in industry prone aquatic environment around Kolkata in India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011;181(1):51–61. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1812-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.