Abstract

A substantial proportion of acute stroke patients fail to recover following successful endovascular therapy (EVT) and injury to the brain and vasculature secondary to reperfusion may be a contributor. Acute stroke patients were included with: i) large vessel occlusion of the anterior circulation, ii) successful recanalization, and iii) evaluable MRI early after EVT. Presence of hyperemia on MRI perfusion was assessed by consensus using a modified ASPECTS. Three different approaches were used to quantify relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF). Sixty-seven patients with median age of 66 [59–76], 57% female, met inclusion criteria. Hyperemia was present in 35/67 (52%) patients early post-EVT, in 32/65 (49%) patients at 24 hours, and in 19/48 (40%) patients at 5 days. There were no differences in incomplete reperfusion, HT, PH-2, HARM, severe HARM or symptomatic ICH rates between those with and without early post-EVT hyperemia. A strong association (R2 = 0.81, p < 0.001) was found between early post-EVT hyperemia (p = 0.027) and DWI volume at 24 hours after adjusting for DWI volume at 2 hours (p < 0.001) and incomplete reperfusion at 24 hours (p = 0.001). Early hyperemia is a potential marker for cerebrovascular injury and may help select patients for adjunctive therapy to prevent edema, reperfusion injury, and lesion growth.

Keywords: Hyperemia, hyperperfusion, luxury perfusion, reperfusion injury, cerebrovascular autoregulation

Introduction

Early recanalization of an occluded vessel has widely been considered the most effective strategy for decreasing morbidity and increasing functional independence following acute ischemic stroke.1,2 Evidence from clinical trials testing the efficacy of endovascular therapy (EVT) in patients with large vessel occlusion stroke continues to grow. An argument has been made to not exclude patients from EVT based on the presumption of irreversibly damaged tissue with little to salvage. 3 However, there is growing recognition that a substantial proportion of patients will not achieve functional independence despite recanalization and new strategies must be used to augment the beneficial effects of recanalization.

One relatively unexplored mediator of clinical outcome is injury to the vasculature and brain following recanalization, secondary to the index ischemic event.4–8 Reperfusion injury has been long recognized as a contributor to secondary injury in pre-clinical models, but has not been widely considered a main contributor to clinical outcome in large vessel occlusion stroke patients. Frequent, early, and abrupt recanalization brought on by modern EVT may have altered that balance.4,9 Prior to recanalization, vessels in the affected vascular territory have maximally dilated, either as the result of lost contractility or through cerebrovascular autoregulation (CA) to maintain cerebral blood flow in the ischemic penumbra.2,10 Upon abrupt resolution of a proximal thrombus, the distal vascular territory immediately experiences an increased cerebral perfusion pressure. 11 Unless the vessels contract, elevated perfusion pressure results in an increase in cerebral blood flow, sometimes referred to as “luxury perfusion”, 12 reactive hyperemia, 13 and/or hyperperfusion,4,14–17 which in turn has the potential to exacerbate injury in the form of increased vascular permeability, edema, and hemorrhage.4,18,19 Loss of CA has generated interest in the best practices for blood pressure management after EVT and in potential therapeutic strategies to minimize secondary injury.1,20–23

Markedly elevated cerebral blood flow on post-EVT MRI, suggestive of hyperemia, has been observed early after recanalization in our population. Similarly, growth of the lesion on diffusion MRI has been seen despite complete recanalization. This leads to the study hypothesis that early hyperemia is associated with subsequent lesion growth. Therefore, the objective of this study is to describe the observations of hyperemia made on post-EVT MRI, test the association of hyperemia with post-EVT evolution of the lesion, and explore the relationship of hyperemia with clinical outcome.

Materials and methods

Patient population

This study is part of an ongoing prospective protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00009243) that was approved by the National Institutes of Health institutional review board (IRB), the Georgetown University – MedStar Health Research Institute IRB, and the Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB, governed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations 45 CFR 46 and in accordance with the ethical principles set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and/or their legally authorized representatives.

Patients presenting to MedStar Washington Hospital Center (Washington, DC) and Suburban Hospital (Bethesda, MD) between April 1, 2018, and April 30, 2021, who met the following criteria were screened and enrolled: i) age ≥18 years, ii) no contraindication to 3 T MRI, iii) EVT attempted, and iv) planned or obtained 3 T MRI studies early post-EVT and at 24 hours (Supplemental Figure 1). Standard treatment with IV thrombolysis was not an exclusion. Patients were included in the analysis with: i) large vessel occlusion of the anterior circulation, ii) a modified Thrombolysis In Cerebral Infarction (mTICI) score of 2B or 3 (successful recanalization) and iii) evaluable perfusion-weighted imaging on early post-EVT MRI. The same inclusion criteria described above were required for a comparative, “control”, group, but with the exception that these control patients had incomplete recanalization defined as mTICI 0, 1 or 2 A based on the angiographic imaging obtained during the endovascular procedure and assigned by the treating neurointerventionalist. Early neurological improvement was defined as a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score decrease ≥4 points or total score of 0–1 at 24 hours. Good clinical outcome was defined as a modified Rankin Scale of 0-2 at 30 or 90 days.

Imaging protocol

Patients underwent MRI on Siemens 3 T or Phillips 3 T early post-EVT, at 24 hours, and at 5 days. The target time for the early post-EVT MRI was within 2 hours following EVT initiation with an upper limit of 6 hours. The MR imaging protocol included diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), gradient recalled echo, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) perfusion-weighted imaging, and MRA. Perfusion-weighted imaging was performed using a weight adjusted single-dose of macrocyclic-gadolinium based contrast agent injected via a power injector. The perfusion-weighted imaging parameters included TR/TE = 1,000–1,200/25 ms, NEX = 1, FA =70–80, 192 × 192–256 × 256 matrix, 20-7 mm thick slices, and 80–120 dynamics and maps of relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and mean transit time were generated using AIF deconvolution. Post-gadolinium FLAIR was obtained at each time point. Pre-EVT MRI with perfusion-weighted imaging was obtained in patients when clinically appropriate and not contraindicated.

Visual assessment of imaging

Three trained raters (AH, LLL, ML) independently evaluated and then reached consensus on the rCBF and mean transit time maps for evidence of hyperemia defined as i) a visually obvious increase in rCBF in the index vascular territory (Supplemental Figure 2A) with ii) a corresponding decrease in mean transit time (Supplemental Figure 2B). To assess spatial extent, hyperemia was noted in 7 MCA regions: Deep, M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, and M6 to produce an ordinal score using a modified Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) 24 applied to MRI (Supplemental Figure 2C) with range of 10 (absent in all regions) to 3 (present in all 7 MCA regions). These scores were evaluated on MRI: pre-EVT when obtained, early post-EVT, at 24 hours, and at 5 days. Incomplete reperfusion was visually assessed as hypoperfused regions within the ischemic vascular territory using the scanner derived perfusion maps including mean transit time and time-to-peak. Hemorrhagic transformation (HT) was read using a modified ECASS-II criterion for gradient recalled echo. 25 Blood-brain barrier disruption was assessed as hyperintense acute reperfusion marker (HARM) using the pre- and post-gadolinium FLAIR.26,27 HARM, a secondary injury marker, was visualized as enhancement of the CSF spaces on FLAIR due to delayed gadolinium contrast extravasation.26,27

Quantitative image analysis

Quantitative image analysis was performed on the patients with successful recanalization (Supplemental Figure 1).

VOI-based hyperemia quantification

Three volume of interest (VOI) methods were utilized to quantify rCBF as follows: i) visually guided rCBF measurement, ii) DWI-based rCBF measurement, and iii) MCA-guided using the M2 region rCBF measurement. Three different quantitative methods were utilized to: i) understand how rCBF measurements varied with the qualitative hyperemia assessments; ii) to measure rCBF using DWI-based regions in the most severe ischemic core portion of the lesions, likely representing the regions with the most severe loss of CA; and iii) and to provide a standardized rCBF measurement across time in all patients by using the MCA-guided M2 region.

The MCA territory with the most visually obvious rCBF increase was sampled by three independent raters using a semi-circular VOI by three raters and averaged, along with a contralateral homologous VOI to calculate the “normally perfused” rCBF signal intensity value (Supplemental Figure 2D), and a rCBF-ratio was calculated. To obtain a control rCBF-ratio, a region ipsilateral to the ischemic MCA region but without visually obvious hyperemia was sampled along with the contralateral homologous VOI on CBF.

The DWI was co-registered to the rCBF map at each time point to sample the largest region in a single slice in the corresponding rCBF location and the contralateral homologous regions (Supplemental Figure 2E) to calculate the DWI-based rCBF-ratios. The same lesion VOI for each subject from a single slice was used to compare change across time and to weigh each subject as equally as possible to limit bias from over representation of large lesions.

A region in the anterior temporal lobe, including the cortex lateral to the insular ribbon (M2 region on ASPECTS), the region most frequently identified as hyperemic (Supplemental Figure 3B), was sampled to quantify ipsilateral-to-contralateral rCBF-ratios across all subjects (Supplemental Figure 2F).

Ischemic core and DWI lesion volumes

Ischemic core volumes using an apparent diffusion coefficient threshold ≤620 µm2/s were calculated using the early post-EVT DWI and apparent diffusion coefficient images using a fully automated novel NIH tool in Mipav (v10, Center for Information Technology, NIH). 8 Core at 24 hours was not calculated due to the prominent presence of areas of both hemorrhagic transformation and associated heterogeneous signal, making a meaningful measure of ischemic core technically difficult. DWI lesion volumes were calculated by two trained raters (ML and RD) on early post-EVT and 24 hours, and FLAIR volumes at 5 days. Lesion growth was defined at 24 hours as an increase in DWI volume >5 mL and at 5 days as an increase in FLAIR volume > 5mL, both relative to the DWI volume measured on early post-EVT MRI.

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as median [IQR], average ± SD, or number (percentage). Cohen’s Kappa test was used to assess inter-rater agreement for the presence of hyperemia. Pearson correlation coefficient was reported for the two independent sets of visually obvious quantitative hyperemia measurements. Exploratory analyses including nonparametric or parametric tests were used as appropriate for variables with significance defined as p-values ≤0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were estimated using linear regression models for DWI volume at 24 hours adjusting for covariates using p-values ≤0.10. Hyperemia on early post-EVT and 24-hour MRI were considered in separate regression models to predict DWI volume at 24 hours.

Results

Two hundred twelve patients were screened for this study (Supplemental Figure 1). Sixty-seven patients (32%) with median age of 66 years [59–76], 57% female, and successful recanalization met inclusion criteria for the analysis (Table 1, Supplemental Figure 1) with early post-EVT MRI time of 1.4 hours [1-2] from recanalization. Forty-five percent of patients received IV thrombolysis (Table 1) and one patient received intra-arterial rtPA. Most patients (54%) had cardioembolic etiology, 12% had large artery, and the remaining 34% had undetermined or other etiology. Forty-two of these patients also had pre-EVT MRI completed with 39/42 (93%) with evaluable perfusion-weighted imaging. Eight patients with median age of 64 years [56-78], 38% female, had incomplete recanalization and were included in the comparative control analysis. The distribution of target vessel locations for the study population was 45 (67%) M1, 11 (16%) M2, 9 (13%) iICA, and 2 (3%) eICA. The distribution for the control population was 6 (75%) M1, 1 (12.5%) M2, and 1 (12.5%) iICA.

Table 1.

Baseline and outcome variables stratified by early post-EVT hyperemia for patients with successful recanalization.

| Variables n (%), median, [IQR] | All (n = 67) |

Early post-EVT hyperemia |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n = 35,52%) | Absent (n = 32,48%) | |||

| Age, years | 66 [59–76] | 67 [60–80] | 64 [57–75] | 0.57 |

| Sex (Female) | 38 (57%) | 22 (63%) | 16 (50%) | 0.33 |

| Risk Factor: Hypertension | 41 (61%) | 23 (66%) | 18 (56%) | 0.80 |

| Risk Factor: Atrial fibrillation | 18 (27%) | 11 (31%) | 7 (22%) | 0.59 |

| Onset (min) | 209 [101–486] | 200 [115–405] | 218 [86–586] | 0.98 |

| Admission NIHSS | 18 [12–22] | 19 [15–22] | 14 [8–20] | 0.30 |

| Preadmission modified Rankin Scale | 0 [0–0] | 0 [0–1] | 0 [0–0] | 0.38 |

| IV rtPA received | 30 (45%) | 18 (51%) | 12 (38%) | 0.33 |

| Cardioembolic etiology | 36 (54%) | 21 (60%) | 15 (47%) | 0.28 |

| M1 occlusion | 45 (67%) | 25 (71%) | 20 (63%) | 0.60 |

| Onset to groin puncture (minutes) | 293 [189–644] | 265 [181–490] | 371 [205–846] | 0.24 |

| Onset to recanalization (minutes) | 329 [245–633] | 322 [241–531] | 379 [254–809] | 0.40 |

| Early post-EVT imaging outcomes | ||||

| Time from recanalization to MRI (hours) | 1.4 [1–2] | 1.4 [1–3] | 1.3 [1–2] | 0.62 |

| Incomplete reperfusion | 41 (61%) | 19 (54%) | 22 (69%) | 0.32 |

| HT | 18 (27%) | 10 (29%) | 8 (25%) | 0.79 |

| PH-2 HT | 3 (4%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 0.48 |

| HARM | 41 (61%) | 19 (54%) | 22 (69%) | 0.27 |

| Severe HARM | 28 (42%) | 13 (37%) | 15 (47%) | 0.61 |

| Core (ADC ≤ 620) volume (mL) | 5 [2–18] | 7 [3–19] | 3 [1–11] | 0.10 |

| DWI volume (mL) | 28 [6–67] | 43 [14–78] | 14 [5–36] | 0.008 |

| 24 Hours clinical and imaging outcomes (n = 65) | ||||

| NIHSS at 24 hours | 12 [3–19] | 12 [4–19] | 11 [3–20] | 0.74 |

| Decrease in NIHSS at 24 hours | 5 [11–0] | 6 [11–2] | 4 [10–(+3)] | 0.30 |

| Early neurological improvement at 24 hours | 39 (60%) | 22 (63%) | 17 (57%) | 0.62 |

| Symptomatic ICH at 24 hours | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1.0 |

| Discharge Disposition (home) | 21 (32%) | 10 (29%) | 11 (37%) | 0.79 |

| Incomplete reperfusion | 25 (38%) | 15 (43%) | 10 (33%) | 0.79 |

| Hyperemia | 32 (49%) | 28 (80%) | 4 (13%) | <0.001 |

| HT | 31 (48%) | 20 (57%) | 11 (37%) | 0.14 |

| PH-2 HT | 3 (5%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 1.0 |

| HARM | 55 (85%) | 30 (86%) | 25 (83%) | 1.0 |

| Severe HARM | 37 (57%) | 20 (57%) | 17 (55%) | 1.0 |

| DWI volume (mL) | 35 [12–93] | 59 [26–103] | 19 [7–55] | 0.008 |

| 30–90 Days clinical outcomes (n = 62) | ||||

| mRS (latest of 30 or 90 day) | 2 [1–5] | 3 [1–5] | 2 [1–4] | 0.46 |

| Good outcome (mRS ≤ 2) (latest of 30 or 90 day) | 32 (52%) | 15 (48%) | 17 (55%) | 0.80 |

DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR: fluid attenuated inversion recovery; EVT: endovascular therapy; HT: hemorrhagic transformation; HARM: Hyperintense Acute Reperfusion Marker; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS: modified Rankin scale.

The inter-rater agreement was 74% for the visual hyperemia assessment (κ = 0.487, 95% CI: 0.315–0.659). Hyperemia was detected in 1/39 (3%) patient prior to EVT. For patients with successful recanalization, hyperemia was present in 35 (52%) patients early post-EVT, in 32 (49%) at 24 hours, and in 19 (40%) at 5 days (Table 1). For patients with incomplete recanalization, hyperemia was present in 4 (50%) patients early post-EVT, in 3 (28%) at 24 hours, and in 3 (43%) at 5 days. Three out of these 4 patients with hyperemia had incomplete recanalization (mTICI 2 A) with 1 having no recanalization (mTICI 0). All 3 patients with incomplete reperfusion demonstrated hyperemia in some perfused regions, but also had hypoperfused regions within the same vascular territory on the early post-EVT MRI. However, the patient with mTICI of 0 at the end of the EVT procedure had imaging evidence of complete recanalization and reperfusion on the early post-EVT MRI consistent with the hyperemia assessment. Only 1 patient with incomplete recanalization (mTICI 2 A) had persistent hyperemia through 5 days.

There were no differences in incomplete reperfusion, HT, PH-2, HARM, severe HARM or symptomatic ICH rates between those with and without early post-EVT hyperemia (Table 1). Patients with and without hyperemia at 24 hours also did not demonstrate differences in these variables listed above (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome variables stratified by post-EVT hyperemia at 24 hours for patients with successful recanalization.

| Variablesn (%), median, [IQR] | All (n = 67) |

Post-EVT hyperemia at 24 hours |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n = 32,53%) | Absent (n = 28,47%) | |||

| 24 Hours clinical and imaging outcomes (n = 60) | ||||

| NIHSS at 24 hours | 12 [3–19] | 12 [6–18] | 10 [2–22] | 0.29 |

| Decrease in NIHSS at 24 hours | 5 [11–0] | 6 [10–2] | 5 [11–(+1)] | 0.52 |

| Early neurological improvement at 24 hours | 39 (60%) | 19 (59%) | 15 (54%) | 0.77 |

| Symptomatic ICH at 24 hours | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 0.92 |

| Discharge Disposition (home) | 21 (32%) | 9 (28%) | 11 (39%) | 0.35 |

| Incomplete reperfusion | 25 (38%) | 10 (31%) | 13 (46%) | 0.31 |

| HT | 31 (48%) | 18 (56%) | 12 (43%) | 0.30 |

| PH-2 HT | 3 (5%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (4%) | 0.64 |

| HARM | 55 (85%) | 28 (88%) | 24 (86%) | 0.84 |

| Severe HARM | 37 (57%) | 19 (59%) | 17 (61%) | 0.92 |

| DWI volume (mL) | 35 [12–93] | 68 [34–117] | 19 [8–55] | <0.001 |

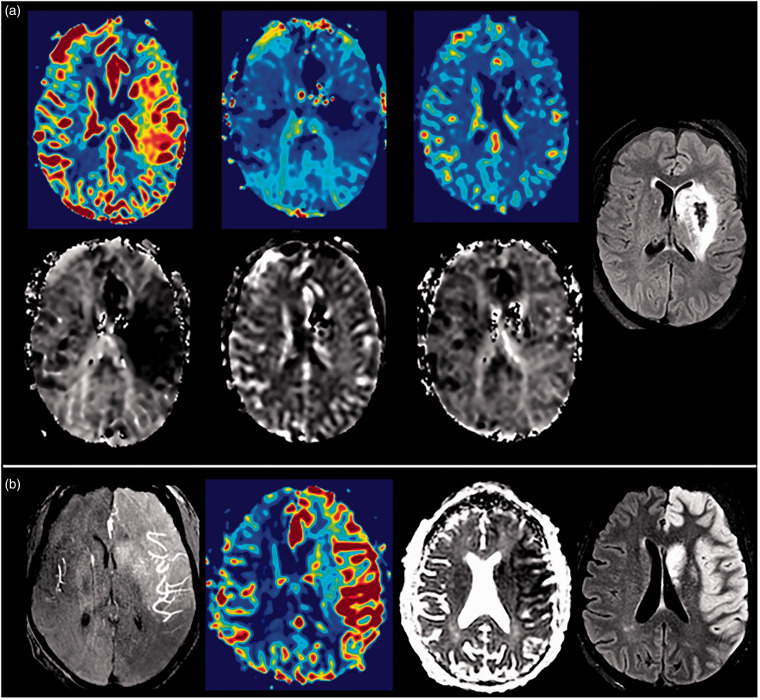

Figure 1(a) illustrates a successfully recanalized patient with hyperemia on early post-EVT MRI that resolved at 24 hours and remained so at 5 days with HI-2 on FLAIR; in a different patient, hyperemia persisted at 5 days on rCBF and mean transit time is displayed with angiographic “blush” on MRA at 24 hours, associated edema, and lesion growth on FLAIR (Figure 1(b)). The distribution of total hyperemia scores early post-EVT for patients with successful recanalization is presented in Supplemental Figure 3A. Supplemental Figures 4A and 5A include the distribution of total hyperemia scores at 24 hours and 5 days. The region-specific distribution of hyperemia is shown in Supplemental Figures 3B, 4B and 5B. Hyperemia on early post-EVT MRI was well-distributed across the MCA regions and most common in the M2 region. Hyperemia involvement across the MCA regions decreased at 5 days. Hyperemia persisted at 24 hours in 28/35 (80%), resolved in 4/35 (11%), and data was not acquired in 3/35 (9%). Hyperemia persisted at 5 days in 14/35 (40%), resolved in 8/35 (23%), and data was not acquired in 13/35 (37%). Hyperemia developed at 24 hours or 5 days in 4 patients, 3 were subtle (score of 9), while 1 was severe (score of 4).

Figure 1.

(a) Patient with successful recanalization and early hyperemia that resolved at 24 hours and remained so at 5 days with HI-2 on FLAIR. Serial rCBF (from left to right: early—24hr—5d) in top panel with corresponding MTT (from left to right: early—24hr—5d) in bottom panel illustrating the elevated rCBF and decreased MTT on early post-EVT, normalized rCBF and MTT at 24 hours, and normalized rCBF and MTT at 5 days with FLAIR (right image) and (b) Patient with successful recanalization and MR angiographic “blush” seen at 24 hours (left image), persistent hyperemia at 5 days demonstrated by elevated rCBF (left middle image), low ADC (right middle image), and lesion growth and edema on FLAIR (right image).

Note – HI: hemorrhagic infarction; FLAIR: fluid attenuated inversion recovery; rCBF: relative cerebral blood flow; MTT: mean transit time; MR: magnetic resonance; ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient.

VOI-based hyperemia quantification

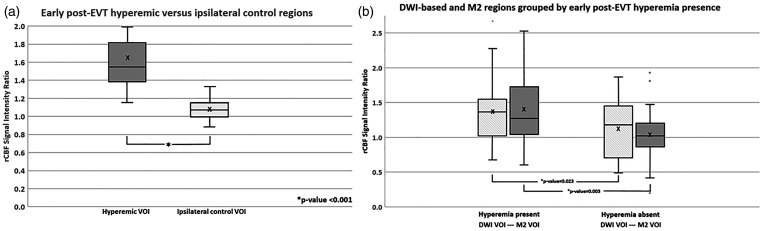

In the analysis, of the 35 patients with early post-EVT hyperemia, the average rCBF signal intensity ratio for the hyperemic vs the ipsilateral control regions was 1.65 ± 0.41 vs 1.08 ± 0.12, p < 0.001 (Figure 2). This represents a significant rCBF increase of ∼ 57% in the hyperemic vs ipsilateral control regions (p < 0.001). At 24 hours, the rCBF difference decreased to ∼ 33% in these same patients, 1.36 ± 0.30 vs 1.03 ± 0.16, p < 0.001, in the hyperemic vs ipsilateral control regions (not shown). The inter-rater agreement of the rCBF-ratios based on Pearson correlation coefficient across the two sets of independent measurements (n = 152) was good (0.71).

Figure 2.

(a) Comparison of rCBF signal intensity ratios on early post-EVT for visually guided hyperemic VOIs vs. ipsilateral control VOIs and (b) DWI-based and MCA-guided M2 region VOI on early post-EVT for successfully recanalized patients with vs without hyperemia.

Note – EVT: endovascular therapy; rCBF: relative cerebral blood flow; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; VOI: volume of interest.

In patients with early post-EVT hyperemia, the average rCBF for both the DWI-based (1.38 ± 0.46 vs 1.13 ± 0.40, p = 0.023) and M2 region VOIs (1.40 ± 0.55 vs 1.04 ± 0.36, p = 0.003) was higher with ∼25–36% rCBF increase compared to those without early post-EVT hyperemia (Figure 2). At 24 hours, the average rCBF was still higher in patients with early post-EVT hyperemia in both DWI-based and M2 regions (Supplemental Figure 6), (1.45 ± 0.46 vs 1.29 ± 0.31, p = 0.26 and 1.19 ± 0.40 vs 0.99 ± 0.36, p = 0.04). At 5 days, there was no difference in the average rCBF of patients with and without early post-EVT hyperemia for the DWI-based regions, (1.36 ± 0.39 vs 1.22 ± 0.93, p = 0.53), and rCBF decreased in both participant groups in the M2 regions (Supplemental Figure 6), (1.16 ± 0.26 vs 0.96 ± 0.34, p = 0.04).

Ischemic core and DWI lesion volumes

In the subset of patients (n = 45) with pre-EVT MRI, there was a trend toward larger median core volumes, 13 [2–51] vs 6 [2–11], in patients with vs without early hyperemia (p = 0.15) but this did not reach significance. However, patients with hyperemia at 24 hours did have significantly larger pre-EVT core volumes, compared to patients without, 16 [5–55] vs 4 [1–9] (p = 0.005).

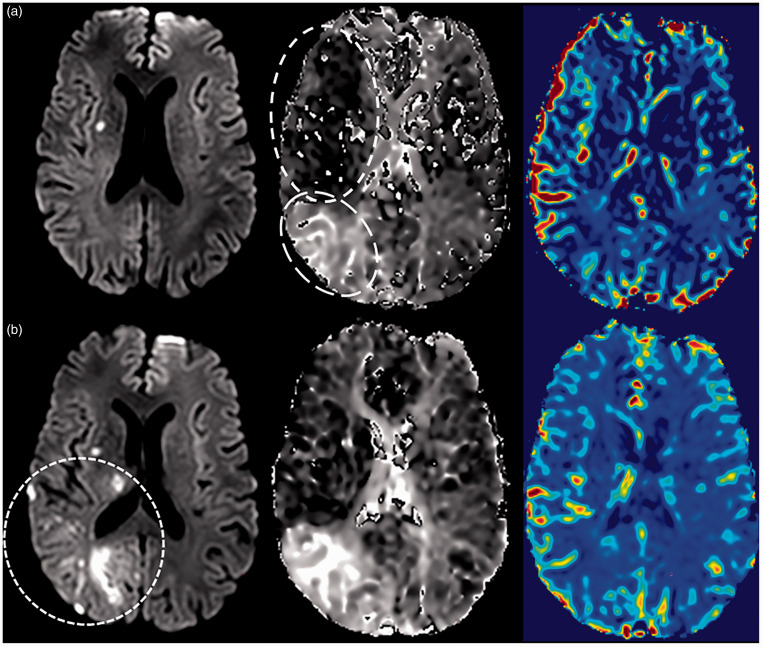

In the analysis, patients with vs without DWI lesion growth at 24 hours had larger core volumes (8 vs 2 mL, p = 0.013) and larger DWI volumes (38 vs 11 mL, p = 0.008) on early post-EVT, with higher rates of hyperemia (59% vs 33%, p = 0.034), HT (59% vs 29%, p = 0.039), and incomplete reperfusion (56% vs 8%, p < 0.001) detected on the 24-hour MRI (Figure 3, Table 3). As illustrated in Figure 3(a), early hyperemia (circled with short-dashed lines) and incomplete reperfusion (circled with long-dashed lines) were coincident in this individual patient. Subsequent lesion growth was visualized on the DWI at 24 hours (circled with dashed lines) in both hyper- and hypo-perfused regions (Figure 3(b)). There was a trend for a higher rate of early post-EVT hyperemia, 63% vs 38% (p = 0.07) in patients with lesion growth vs without lesion growth at 24 hours. Univariate analysis (Table 3) demonstrated differences between patients with vs without DWI lesion growth at 24 hours in the rates of early post-EVT core and DWI volumes, post-EVT hyperemia, incomplete reperfusion, HT rates, and DWI volume at 24 hours. Using linear regression, a strong association (R2 = 0.81, p < 0.001, 95% CI, −33.3-(−2)) was found between early post-EVT hyperemia (p = 0.027) and DWI volume at 24 hours even after adjustment using DWI volume at 2 hours (p < 0.001) and incomplete reperfusion at 24 hours (p = 0.001) as covariates.

Figure 3.

(a) Patient with successful recanalization, early hyperemia (circled with short-dashed lines), and incomplete reperfusion (circled with long-dashed lines). Early DWI in top panel with corresponding MTT and rCBF illustrating the elevated rCBF and decreased MTT on early post-EVT and (b) Same patient in bottom panel at 24 hours with DWI lesion growth (circled with dashed lines), persistent hyperemia and incomplete reperfusion with corresponding MTT and rCBF.

Note – DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; MTT: mean transit time; rCBF: relative cerebral blood flow.

Table 3.

Outcome variables stratified by DWI lesion growth from early to 24 hours post-EVT for patients with successful recanalization.

| Outcome variables n (%), median [IQR] | All (n = 65)a | DWI lesion growth at 24 hours |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n = 41,63%) | Absent (n = 24,37%) | |||

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| NIHSS at 24 hours | 12 [3–19] | 12 [6–20] | 10 [1–15] | 0.26 |

| Decrease in NIHSS at 24 hours | 5 [11–0] | 3 [8–3] | 7 [12–4] | 0.66 |

| Early neurological improvement at 24 hours | 37 (57%) | 19 (46%) | 18 (75%) | 0.018 |

| Symptomatic ICH at 24 hours | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 |

| Discharge Disposition (home) | 21 (32%) | 8 (20%) | 13 (54%) | 0.005 |

| mRS (latest of 30 or 90 day) | 2 [1–5] | 3 [2–5] | 1 [0–4] | 0.029 |

| Good outcome (mRS ≤ 2 ) (latest of 30 or 90 day) | 32 (49%) | 18 (44%) | 14 (58%) | 0.43 |

| Early post-EVT imaging outcomes | ||||

| Incomplete reperfusion | 39 (60%) | 27 (66%) | 12 (50%) | 0.29 |

| Hyperemia | 35 (54%) | 26 (63%) | 9 (38%) | 0.07 |

| HT | 17 (26%) | 12 (29%) | 5 (21%) | 0.57 |

| PH-2 HT | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0.37 |

| HARM | 40 (62%) | 24 (59%) | 16 (67%) | 0.39 |

| Severe HARM | 28 (43%) | 17 (41%) | 11 (46%) | 0.60 |

| Core (ADC ≤ 620) volume (mL) | 5 [2–18] | 8 [3–19] | 2 [1–8] | 0.013 |

| DWI volume (mL) | 28 [6–63] | 38 [14–77] | 11 [3–37] | 0.008 |

| 24 Hours imaging outcomes | ||||

| Incomplete reperfusion | 25 (38%) | 23 (56%) | 2 (8%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperemia | 32 (49%) | 24 (59%) | 8 (33%) | 0.034 |

| HT | 31 (48%) | 24 (59%) | 7 (29%) | 0.039 |

| PH-2 HT | 3 (5%) | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.55 |

| HARM | 55 (85%) | 36 (88%) | 19 (79%) | 0.71 |

| Severe HARM | 37 (57%) | 26 (63%) | 11 (46%) | 0.29 |

| DWI volume (mL) | 35 [12–93] | 59 [28–115] | 10 [3–26] | <0.001 |

| Change in DWI volume (mL) | 9 [2–24] | 17 [10–31] | 1 [−0.5–2] | – |

|

DWI lesion growth at 24 hours |

||||

|

|

All Patients (n = 48) |

Present (n = 30,62.5%) |

Absent (n = 18,37.5%) |

p-value |

| 5 Days imaging outcomes | ||||

| Hyperemia | 19 (40%) | 14 (47%) | 5 (28%) | 0.22 |

| HT | 22 (46%) | 16 (53%) | 6 (33%) | 0.24 |

| PH-2 HT | 3 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 1.0 |

| FLAIR volume (mL) | 46 [15–118] | 74 [32–130] | 23 [6–49] | 0.005 |

| Change in lesion volume (mL) | 18 [4–36] | 26 [15–41] | 1 [−1–14] | <0.001 |

| Lesion growth | 34 (71%) | 28 (93%) | 6 (33%) | <0.001 |

aTotal of 65/67 patients had available 24-hour data for lesion growth stratification into groups.

DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR: fluid attenuated inversion recovery; EVT: endovascular therapy; HT: hemorrhagic transformation; HARM: Hyperintense Acute Reperfusion Marker; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS: modified Rankin scale.

Clinical outcome

For the analysis of patients with successful recanalization, there were no differences in univariate analysis between patients with and without early hyperemia in baseline characteristics including age, admission NIHSS, onset time, onset to recanalization time, M1 occlusion rates, and IV rtPA treatment rates (Table 1). Comparing patients with and without hyperemia, clinical outcomes including NIHSS at 24 hours, decrease in NIHSS at 24 hours, early neurological improvement rates, modified Rankin Scale at 30 to 90 days, and good clinical outcome (modified Rankin Scale 0-2) were not significantly different (Table 1).

Discussion

We demonstrated that a dramatic increase in relative cerebral blood flow, suggestive of post-ischemic reactive hyperemia, occurs early after technically successful recanalization by EVT, is common, and can persist up to one week. Rates of 40–50% post-recanalization hyperperfusion were described previously in a small sample of patients receiving intra-arterial thrombolysis imaged with MRI several hours to one week following successful recanalization. 14 Our finding of 45% post-EVT hyperemia within one week is consistent with this previous study, and we have also demonstrated that the phenomenon occurs immediately following successful recanalization. Pre-EVT hyperemia was present in only one patient (3%) of those with evaluable MR perfusion imaging, likely due to spontaneous reperfusion provided by collateral circulation. Quantitative measurements confirmed a significant increase in rCBF of ∼57% compared to ipsilateral regions on the early post-EVT MRI.

A significant portion of acute stroke patients who undergo EVT still do not achieve good clinical outcomes despite the high rates of angiographic recanalization. Factors contributing to poor outcome include persistent or residual perfusion deficits due to distal emboli or no-reflow6,8,28 and secondary injury in the setting of reperfusion such as blood-brain barrier breakdown with hemorrhage and/or edema.5,7 We have previously shown that incomplete reperfusion early post-EVT despite angiographic success is seen in up to 61% of patients and is a predictor of worse outcome. 8 We attempted to control for vascular status by including only patients with successful recanalization in the analysis. In this current study, we have identified a marked increase in rCBF as an additional potential mediator of outcome post-EVT that may also be a target for treatment. “Bioenergetic compromise” using ADC core was proposed as a possible cause for the likelihood of infarction in areas demonstrating hyperperfusion. 14 Separately, quantitative CBF following MCAO in adult rats has been used to follow the time course of ischemia and correlations with vasoreactivity and angiogenesis with findings that ischemia led to later hyperperfusion and increased infarction. 29 We did find an association between early hyperemia and lesion growth, suggesting post-EVT hyperemia may not be benign.

In some previous studies, hyperperfusion has been interpreted as a positive prognostic indicator and associated with treatment response.12,16,17,30 It is reasonable to expect hyperperfusion, as a surrogate marker for successful reperfusion by EVT, would be associated with improved outcome in comparison to persistent hypoperfusion or incomplete reperfusion. It is also possible that areas identified as hyperperfused are contained in regions of oligemia and therefore not at risk for infarction. This heterogeneity in the severity and duration of ischemia prior to recanalization likely contributes to the variability in presence, localization, and degree of hyperemia post-recanalization. 31 The microcirculatory responses to EVT including no-reflow may contribute to even more heterogeneity within the penumbral pattern. However, the co-occurrence of residual hypoperfusion deficit and regions of elevated rCBF, in the same patient as was seen in 54% of this population, confound an association of these imaging markers with clinical outcome, and may in part explain discrepant findings in the literature.15–18 Further work is needed to better elucidate the relationship between the heterogeneity of ischemic injury during triage and localization of areas of hyperperfusion or incomplete reperfusion following recanalization.

Despite normalization in some patients, we found early post-EVT hyperemia to be strongly associated with lesion growth at 24 hours even after adjusting for incomplete reperfusion and early DWI volume. This finding indicates that lesion growth occurred in regions that were no longer hypoperfused post-EVT, and extended into hyperemic or reperfused regions. However, it is not possible to confirm this since it was not possible to measure the extent of the pre-EVT perfusion lesion in all patients. The association between elevated rCBF and subsequent lesion growth may reflect exacerbation of pre-thrombectomy ischemic injury and/or progression of cerebral edema. In this study, while the early post-EVT ischemic core volume (based on low apparent diffusion coefficient) did not differ between early hyperemia cohorts, the pre-EVT core volume was larger in patients with early hyperemia, suggesting a greater extent of neuronal and vascular injury. Furthermore, the DWI lesion did grow significantly in patients with early post-EVT hyperemia suggesting an increase in vasogenic edema as another factor mediating outcome. Both ischemic core growth and vasogenic edema evolution are likely contributors to lesion growth.

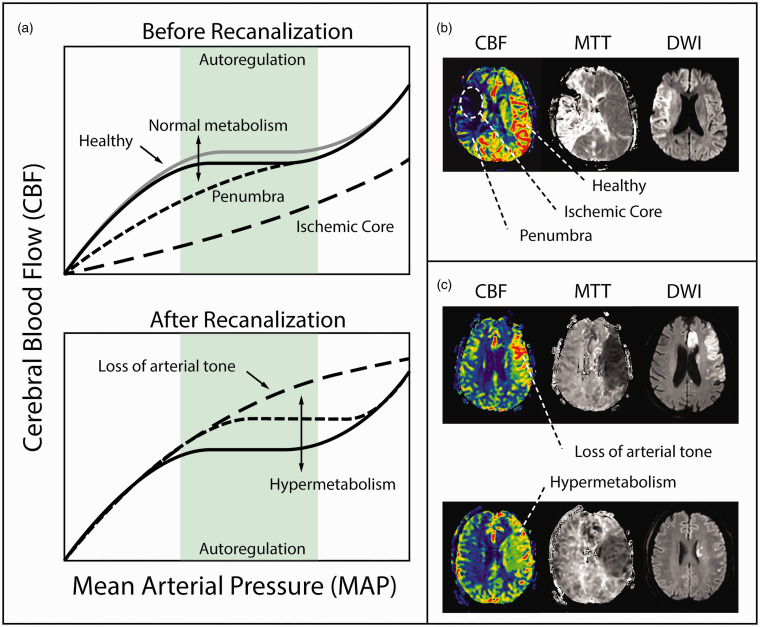

Likely mechanisms of post-EVT hyperemia fall into one of two broad categories: i) loss of CA (reactive hyperemia) or ii) hypermetabolism (functional hyperemia) (Figure 4). Cerebral ischemia, distal to a large vessel occlusion, leads directly to vascular injury and loss of arterial tone. Vasoreactivity is compromised by ischemia, vessels are no longer able to contract, vascular resistance remains low following recanalization, and CBF becomes directly coupled to mean arterial pressure. The classic description of luxury perfusion is a plausible explanation.12,32 There is also evidence for favorable tissue outcome in response to functional hyperemia 30 achieved through successful recanalization, suggesting hyperemia may be a harmless and potentially beneficial phenomenon. 30 However, the hyperemic territory is left vulnerable to secondary injury in the form of oxidative stress, endothelial activation, recruitment of circulating myelomonocytic cells, blood-brain barrier disruption, edema, and HT, all of which may be exacerbated by an unregulated increase in CBF coupled to systemic blood pressure. The rate of severe HARM at 24 hours found in this study, 57%, is within the reported range, 54–64%, of prior studies from the same centers involving different patients with similar inclusion criteria.5,8 The rate of any HT at 24 hours, 48%, was also within the reported range of these same studies, 45–51%.5,8 Though we expected patients with hyperemia would be more likely to have blood-brain barrier disruption or hemorrhage, there were no significant differences in the rates of HARM, severe HARM or HT between patients with and without early post-EVT hyperemia. Other studies have also reported an unclear association between hyperemia and HT, perhaps significant for severe HT only.15,16,18

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of post-EVT hyperemia. (a) Mean arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow before and after recanalization demonstrating the loss of arterial tone and associated hypermetabolism due to loss of cerebral autoregulation. (b) Patient example of large vessel occlusion with associated ischemic core and surrounding penumbra before recanalization indicated on the CBF with consistent hypoperfusion on MTT and lesion on DWI and (c) Patient examples after recanalization of hypermetabolism visualized as an increase in CBF, decrease in MTT, and associated DWI lesions.

Note – CBF: cerebral blood flow; MTT: mean transit time; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging.

Regardless of the exact mechanism, it is hard to argue that dramatically elevated rCBF as was measured in this study, is physiologically atypical and therefore is indicative of a pathological process. Hyperemia, or more broadly, impaired CA, is clinically recognized as a potential downstream effect or complication post-EVT.6,10,33,34 For this reason, blood pressure management is incorporated into clinical practice guidelines recommending blood pressure thresholds <180/105 mm Hg in patients successfully recanalized based on prior RCT protocols. 1 Some studies of patients post-EVT have suggested an association between higher blood pressure post-EVT and worse outcomes, but without any measure of CA or perfusion imaging.20,21 However, an observational study that dynamically monitored CA using near-infrared spectroscopy did find an association between loss of CA and worse clinical and radiographic outcomes. 23 One of the ongoing trials of targeting lower BP post-EVT does include TCD monitoring, 35 presumably to understand the mechanism of BP management in this context, though none are directly measuring CA nor perfusion.35–38 An alternative explanation is that vasoreactivity is sustained and CA remains intact and the increase in CBF detected following recanalization is indicative of an active compensatory mechanism coupled to an increased metabolic demand. Regardless of the causal mechanism, the elevation of rCBF detected in this study was shown to be common and sustained.

This study has a few potential limitations. Only consented patients were included in the analysis, introducing potential bias in that the study population may not be representative of a larger EVT-treated patient population. It is important to acknowledge that this analysis was performed on a per-patient basis possibly contributing to the heterogeneity of the findings. The availability of multimodal MRI early following EVT is not standard of care at most stroke centers, however, acquiring MRI at 24 hours post-EVT is feasible and frequently obtained in routine clinical practice in patients receiving EVT. While hyperemia is not expected prior to recanalization, pre-EVT MRI is not routinely obtained in standard clinical practice except in a limited subgroup of patients. Maps of rCBF are highly heterogeneous and compared to regions of hypoperfusion, hyperemia is visually less conspicuous. The rCBF quantitative values reported in this study are ratios of signal intensity values measured from the rCBF maps and may not be directly proportional to the physiological CBF values. We therefore used three independent quantitative methods that consistently confirmed significant increases in rCBF in visually-apparent regions of hyperemia.

In summary, hyperemia occurs early after recanalization with EVT, is common and persists up to a week, and when detected early after mechanical recanalization is an independent predictor of lesion growth. Future directions may also include evaluating pre-EVT imaging markers to determine predictors of subsequent hyperemia. Early hyperemia is a potential marker for cerebrovascular injury and may help select patients for adjunctive therapy to prevent edema, reperfusion injury, and lesion growth.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231155222 for Post-ischemic hyperemia following endovascular therapy for acute stroke is associated with lesion growth by Marie Luby, Amie W Hsia, Carolyn A Lomahan, Rachel Davis, Shannon Burton, Yongwoo Kim, Veronica Craft, Victoria Uche, Rainier Cabatbat, Malik M Adil, Leila C Thomas, Jill B De Vis, Mariam M Afzal, Dorian McGavern, John K Lynch, Richard Leigh and Lawrence L Latour in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We thank our patients and their families, without whom this research would not have been possible. We also appreciate the clinicians and research and administrative teams for their support of the Natural History of Stroke study.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this work was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: Conceptualization, ML, AWH, LLL; writing-original draft preparation, ML, AWH, CAL, LLL; investigation and data curation, ML, AWH, CAL, RD, SB, YK, VC, VU, RC, MMA, LCT, JBDV, MMA, JKL, RL, LLL; writing-review & editing, ML, AWH, YK, RL, DM, LLL; formal analysis and visualization, ML, AWH, CAL, LLL; project administration, LLL; supervision, LLL; funding acquisition, LLL.

ORCID iDs: Leila C Thomas https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0815-0578

Richard Leigh https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8285-1815

Lawrence L Latour https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6160-5263

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019; 50: e344–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boisseau W, Desilles JP, Fahed R, et al. Neutrophil count predicts poor outcome despite recanalization after endovascular therapy. Neurology 2019; 93: e467–e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyal M, Ospel JM, Menon B, et al. Challenging the ischemic core concept in acute ischemic stroke imaging. Stroke 2020; 51: 3147–3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potreck A, Mutke MA, Weyland CS, et al. Combined perfusion and permeability imaging reveals different pathophysiologic tissue responses after successful thrombectomy. Transl Stroke Res 2021; 12: 799–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luby M, Hsia AW, Nadareishvili Z, et al. Frequency of blood-brain barrier disruption post-endovascular therapy and multiple thrombectomy passes in acute ischemic stroke patients. Stroke 2019; 50: 2241–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng FC, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Prevalence and significance of impaired microvascular tissue reperfusion despite macrovascular angiographic reperfusion (no-reflow). Neurology 2021; 98: e790–e801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng FC, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Microvascular dysfunction in blood-brain barrier disruption and hypoperfusion within the infarct posttreatment are associated with cerebral edema. Stroke 2022; 53: 1597–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luby M, Merino JG, Davis R, et al. Association of multiple passes during mechanical thrombectomy with incomplete reperfusion and lesion growth. Cerebrovasc Dis 2022; 51: 394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng FC, Campbell BCV.Imaging after thrombolysis and thrombectomy: rationale, modalities and management implications. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019; 19: 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer M, Juenemann M, Braun T, et al. Impaired cerebrovascular autoregulation in large vessel occlusive stroke after successful mechanical thrombectomy: a prospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2020; 29: 104596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostergaard L, Dreier JP, Hadjikhani N, et al. Neurovascular coupling during cortical spreading depolarization and -depression. Stroke 2015; 46: 1392–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassen NA.The luxury-perfusion syndrome and its possible relation to acute metabolic acidosis localised within the brain. Lancet 1966; 2: 1113–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen TS, Larsen B, Skriver EB, et al. Focal cerebral hyperemia in acute stroke. Incidence, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Stroke 1981; 12: 598–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Mattiello J, et al. Diffusion-perfusion MRI characterization of post-recanalization hyperperfusion in humans. Neurology 2001; 57: 2015–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu S, Liebeskind DS, Dua S, et al. Postischemic hyperperfusion on arterial spin labeled perfusion MRI is linked to hemorrhagic transformation in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 630–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimonaga K, Matsushige T, Hosogai M, et al. Hyperperfusion after endovascular reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2019; 28: 1212–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu SS, Cao YZ, Su CQ, et al. Hyperperfusion on arterial spin labeling MRI predicts the 90-day functional outcome after mechanical thrombectomy in ischemic stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging 2021; 53: 1815–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosior JC, Buck B, Wannamaker R, et al. Exploring reperfusion following endovascular thrombectomy. Stroke 2019; 50: 2389–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu S, Ma SJ, Liebeskind DS, et al. Reperfusion into severely damaged brain tissue is associated with occurrence of parenchymal hemorrhage for acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mistry EA, Sucharew H, Mistry AM, et al. Blood pressure after endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke (BEST): a multicenter prospective cohort study. Stroke 2019; 50: 3449–3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsanos AH, Malhotra K, Ahmed N, et al. Blood pressure after endovascular thrombectomy and outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Neurology 2022; 98: e291–e301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazighi M, Richard S, Lapergue B, et al. Safety and efficacy of intensive blood pressure lowering after successful endovascular therapy in acute ischaemic stroke (BP-TARGET): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2021; 20: 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen NH, Silverman A, Strander SM, et al. Fixed compared with autoregulation-oriented blood pressure thresholds after mechanical thrombectomy for ischemic stroke. Stroke 2020; 51: 914–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J, et al. Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. ASPECTS Study Group. Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score. Lancet 2000; 355: 1670–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renou P, Sibon I, Tourdias T, et al. Reliability of the ECASS radiological classification of postthrombolysis brain haemorrhage: a comparison of CT and three MRI sequences. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010; 29: 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latour LL, Kang DW, Ezzeddine MA, et al. Early blood-brain barrier disruption in human focal brain ischemia. Ann Neurol 2004; 56: 468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warach S, Latour LL.Evidence of reperfusion injury, exacerbated by thrombolytic therapy, in human focal brain ischemia using a novel imaging marker of early blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke 2004; 35: 2659–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He YB, Su YY, Rajah GB, et al. Trans-cranial doppler predicts early neurologic deterioration in anterior circulation ischemic stroke after successful endovascular treatment. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020; 133: 1655–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wegener S, Artmann J, Luft AR, et al. The time of maximum post-ischemic hyperperfusion indicates infarct growth following transient experimental ischemia. PLoS One 2013; 8: e65322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchal G, Furlan M, Beaudouin V, et al. Early spontaneous hyperperfusion after stroke. A marker of favourable tissue outcome? Brain 1996; 119: 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Zoppo GJ, Sharp FR, Heiss WD, et al. Heterogeneity in the penumbra. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1836–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manabe H ZB.Messmer K microcirculation in circulatory disorders. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Claassen J, Thijssen DHJ, Panerai RB, et al. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol Rev 2021; 101: 1487–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman A, Kodali S, Sheth KN, et al. Hemodynamics and hemorrhagic transformation after endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blood Pressure Management in Stroke Following Endovascular Treatment (DETECT), ClinicalTrials.gov Web site, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04484350 (accessed 22 March 2022).

- 36.Blood Pressure After Endovascular Stroke Therapy-II (BEST-II), ClinicalTrials.gov Web site, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04116112 (accessed 2 March 2022).

- 37.Second Enhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombectomy Stroke Study (ENCHANTED2), ClinicalTrials.gov Web site, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04140110 (accessed 29 March 2022).

- 38.Intensive Control of Blood Pressure in Acute Ischemic Stroke After Endovascular Therapy on Clinical Outcome (CRISIS I), ClinicalTrials.gov Web site, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04775147 (accessed 14 April 2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X231155222 for Post-ischemic hyperemia following endovascular therapy for acute stroke is associated with lesion growth by Marie Luby, Amie W Hsia, Carolyn A Lomahan, Rachel Davis, Shannon Burton, Yongwoo Kim, Veronica Craft, Victoria Uche, Rainier Cabatbat, Malik M Adil, Leila C Thomas, Jill B De Vis, Mariam M Afzal, Dorian McGavern, John K Lynch, Richard Leigh and Lawrence L Latour in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism