Abstract

Ureteroscopy is increasingly being used for urolithiasis. Technological innovations have been accompanied by wide variations in practice patterns. At the same time, a common finding in many studies, especially systematic reviews, is that the heterogeneity of outcome measurements and lack of standardisation can limit both the reproducibility and generalisability of study findings. While many checklists are available to improve study reporting, there are no ureteroscopy-specific ones. The Adult-Ureteroscopy (A-URS) checklist is a practical aid for both researchers and reviewers for studies in this field. It contains five main sections (study details, preoperative, operative, postoperative, and long term data) and a total of 20 items.

Patient summary

We developed a checklist to improve how studies on ureteroscopy (insertion of a telescope through the urethra to inspect the urinary tract) in adults are reported. This could help in advancing the field and improving patient outcomes, as all the key information is captured.

Keywords: Ureteroscopy, Urolithiasis, Adult, Checklist

Checklists are well established in the setting of study reporting. Examples include Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidance for observational studies and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement [1], [2]. These are valuable tools for both authors and reviewers when making an assessment for publication. However, procedure-specific tools are lacking in surgery, which is also the case for endourology. We recently developed the Paediatric Ureteroscopy (P-URS) checklist to improve standardisation of parameters reported in this clinical area [3]. As for paediatric URS, practice patterns vary widely in adult URS [4]. Topics of continued debate and disagreement include the role of access sheaths, laser settings, and prestenting. A core reason for this variation is the heterogeneity of data collection and reporting. This is a common conclusion in literature reviews [5], [6].

While there is an ever-increasing volume of URS publications, which is of course welcome, the path towards gaining clarity and resolution will be slow without more efforts to address these issues. Results can also be misleading when subtleties in study protocols are not clearly defined. This can cause confusion for readers, especially for more junior faculty without the experience to “read between the lines” regarding a study’s results. For example, it can be claimed that a particular technique for URS is superior as the stone-free rate (SFR) was higher than in another study. However, the latter study may have pooled SFR data for renal and ureteral stones but not made it clear that 90% of the burden was represented by distal ureteric stones. Even such seemingly small points can lead to quick dissemination of the conclusion that one modality is clearly superior. This is just one example of many.

With these issues in mind, we created the Adult Ureteroscopy (A-URS) checklist to complement the P-URS [3]. The development process mirrored the methods used for the P-URS, including a literature review (P.J.-J. and B.K.S.) and the development of a list of core items. The draft version was critiqued by all of the authors and then revised accordingly. This process was repeated a total of four times until consensus was finally achieved. Before its development, the team decided that the general layout for the A-URS would match that of the P-URS. While many of the points included in the final version may seem obvious at first glance, a review of the literature on adult URS revealed that such information is often missing.

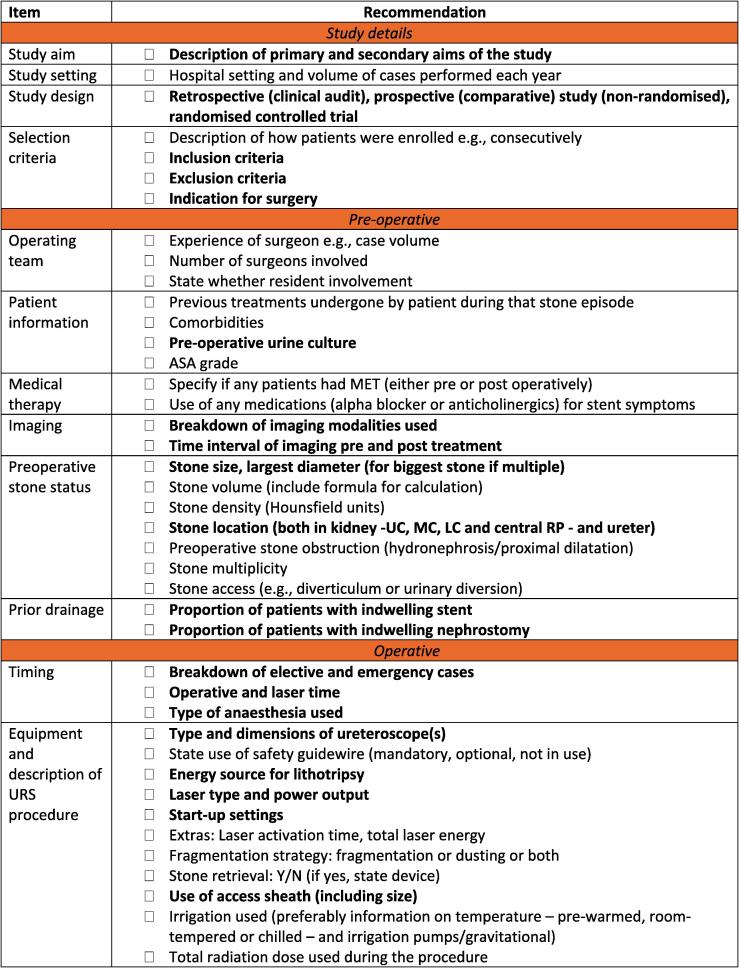

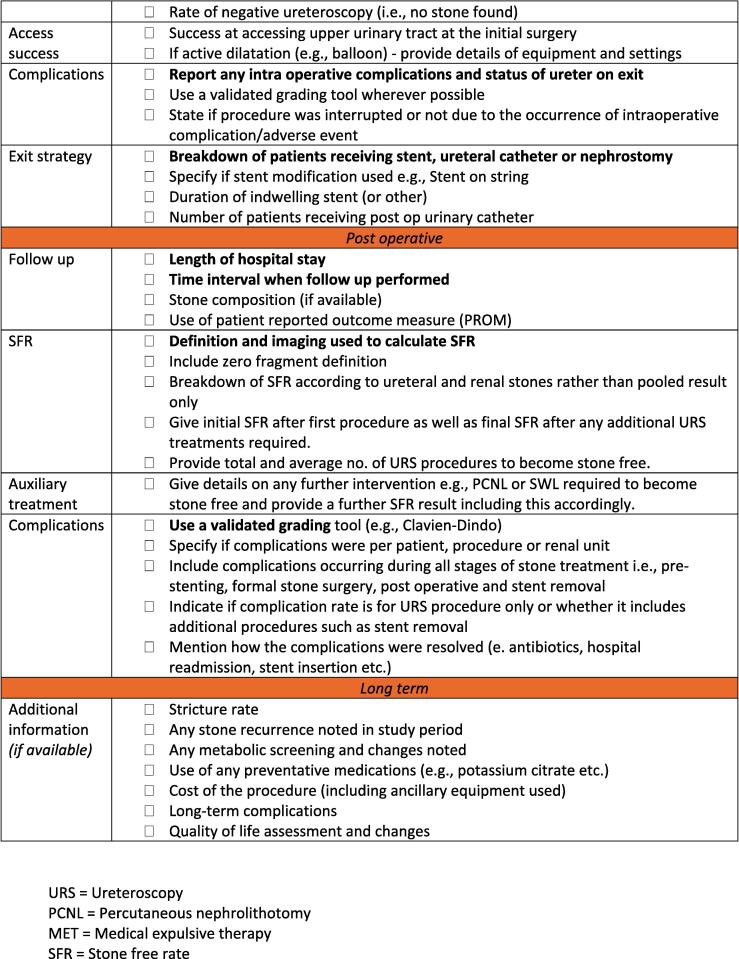

The final version is shown in Figure 1. Key items deemed by the authors to be of high priority are highlighted in bold font. There are five main sections, which cover information on the following areas: study details, and preoperative, operative, postoperative, and long-term data.

Fig. 1.

Adult Ureteroscopy (A-URS) checklist. Items of high priority are highlighted in bold font.

Section 1 (Study details) covers generic information relevant to the study such as the aim, design, setting (eg, academic or community and annual case volume), as well as the study selection criteria and indication for the surgery.

Section 2 (Preoperative data) includes details for the operating team (eg, experience) and the number of surgeons involved in the study. This has relevance as it helps in differentiating when a series has been performed by single expert surgeon or whether a group that includes residents was involved. Information on patient demographics is also included here (eg, preoperative urine culture). Another important area covered is preoperative stone status, including stone dimensions, multiplicity, and location, as well as imaging modality. Maximal stone diameter is still the most common measure of size, but stone volume is increasingly being used.

Section 3 contains operative information. Key areas include information relating to the energy source (laser type, power output, and start-up settings). Intraoperative complications can occur, and tools exist that can aid classification at the time of reporting, such as ClassIntra [7]. In cases in which ureteral mucosal trauma has occurred, this can be graded, for example, using the Traxer and Thomas system [8]. The exit strategy should be made clear, including use of any modifications such as a stent on a string.

Section 4 covers postoperative information and follow-up. Consensus is lacking on the ideal approach for reporting stone-free status. From a practical perspective, the inclusion of at least a zero-fragment definition allows for a useful baseline when comparing study results. Use of noncontrast computed tomography allows for more accurate assessment of the residual stone burden and is preferable if available. As well as use of a classification tool for postoperative complications, we recommend recording of further details, rather than only reporting the percentage breakdown for major and minor adverse events, as is often observed. This should also include the time period over which complications were recorded (eg, 30 d).

Section 5 covers long-term information as well as more general items that are valuable for analysis, if available. With this in mind, it is fully appreciated that when undertaking retrospective data collection, not all items can be gathered at a later date; for example, access to prescription records or patients treated out of the area with loss to longer-term follow-up may not be possible.

While there is clear overlap with the P-URS, there are a number of subtle but important differences. In the paediatric setting, for example, further breakdown of the sample by age group is suggested (eg, infants, children, prepuberty, adolescents) and/or weight. Another difference is the highlighting any additional intraoperative radiation protection measures in paediatric URS and transparency regarding repeat URS at the time of stent removal, given that this is typically performed under general anaesthesia in the paediatric age group. The A-URS also includes an additional fifth section that covers long-term information such as the stricture rate and quality of life that is not present in the P-URS checklist.

The A-URS checklist is not aimed at being an exhaustive list and authors should also not feel obligated to include every item. The main goal is to provide a practical supplement that authors and reviewers can use to provide more robust studies and reports in the setting of URS and stone lithotripsy.

Author contributions: Patrick Juliebø-Jones had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Juliebø-Jones, Somani, Ulvik, Beisland.

Acquisition of data: Juliebø-Jones, Somani, Ulvik, Beisland.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Juliebø-Jones, Somani, Ulvik, Beisland.

Drafting of the manuscript: Juliebø-Jones, Somani, Ulvik, Beisland.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Juliebø-Jones, Somani, Ulvik, Beisland.

Statistical analysis: None.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: None.

Supervision: Somani.

Other: None.

Financial disclosures: Patrick Juliebø-Jones certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Øyvind Ulvik has acted as a consultant for Olympus. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Data sharing statement: The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Associate Editor: Silvia Proietti

References

- 1.Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31–S34. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moher D., Schulz K.F., Altman D., CONSORT Group The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juliebø-Jones P., Ulvik Ø., Beisland C., Somani B.K. Paediatric Ureteroscopy (P-URS) reporting checklist: a new tool to aid studies report the essential items on paediatric ureteroscopy for stone disease. Urolithiasis. 2023;51:35. doi: 10.1007/s00240-023-01408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietropaolo A., Bres-Niewada E., Skolarikos A., et al. Worldwide survey of flexible ureteroscopy practice: a survey from European Association of Urology sections of Young Academic Urologists and Uro-technology Groups. Cent Eur J Urol. 2019;72:393–397. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2019.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geraghty R.M., Jones P., Herrmann T.R.W., Aboumarzouk O., Somani B.K. Ureteroscopy is more cost effective than shock wave lithotripsy for stone treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol. 2018;36:1783–1793. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2320-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietropaolo A., Jones P., Whitehurst L., Rai B.P., Geraghty R., Somani B.K. Efficacy and safety of ureteroscopy for stone disease in a solitary kidney: findings from a systematic review. Urology. 2018;119:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dell-Kuster S., Gomes N.V., Gawria L., et al. Prospective validation of classification of intraoperative adverse events (ClassIntra): international, multicentre cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Traxer O., Thomas A. Prospective evaluation and classification of ureteral wall injuries resulting from insertion of a ureteral access sheath during retrograde intrarenal surgery. J Urol. 2013;189:580–584. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]