Abstract

Introduction:

Sleep disturbance is associated with autonomic dysregulation, but the temporal directionality of this relationship remains uncertain. The objective of this study was to evaluate the temporal relationships between objectively measured sleep disturbance and daytime or nighttime autonomic dysregulation in a co-twin control study.

Methods:

A total of 68 members (34 pairs) of the Vietnam Era Twin Registry were studied. Twins underwent 7-day in-home actigraphy to derive objective measures of sleep disturbance. Autonomic function indexed by heart rate variability (HRV) was obtained using 7-day ECG monitoring with a wearable patch. Multivariable vector autoregressive models with Granger causality tests were used to examine the temporal directionality of the association between daytime and nighttime HRV and sleep metrics, within twin pairs, using 7-day collected ECG data.

Results:

Twins were all male, mostly white (96%), with mean (SD) age of 69 (2) years. Higher daytime HRV across multiple domains was bidirectionally associated with longer total sleep time and lower wake after sleep onset; these temporal dynamics were extended to a window of 48 h. In contrast, there was no association between nighttime HRV and sleep measures in subsequent nights, or between sleep measures from previous nights and subsequent nighttime HRV.

Conclusions:

Daytime, but not nighttime, autonomic function indexed by HRV has bidirectional associations with several sleep dimensions. Dysfunctions in autonomic regulation during wakefulness can lead to subsequent shorter sleep duration and worse sleep continuity, and vice versa, and their influence on each other may extend beyond 24 h.

Keywords: Sleep, Autonomic nervous system, Actigraphy, Time series analysis

1. Introduction

Sleep is an essential component of physiological regulation and is critical for optimal brain and bodily functions. Sleep disturbance is associated with higher risk for many chronic conditions, especially cardiovascular disease (CVD). [1,2] However, the precise biological mechanisms linking sleep disturbance with CVD risk are only beginning to be understood. One of these potential mechanisms is dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which controls basic bodily functions such as heartbeat, digestion and respiration. [3,4]

ANS regulation can be assessed noninvasively using heart rate variability (HRV), which provides a measure of beat-to-beat heart rate fluctuations over time. Reduced HRV is indicative of an imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation, i.e., heightened sympathetic activity and/or vagal withdrawal, [5] and is an independent predictor of CVD morbidity and mortality. [6–8]

At present, the pathways linking ANS function and sleep need further explorations and the directionality of their associations and potentially lasting effects still remain unclear. Some studies have suggested that sleep disturbance, including obstructive sleep apnea and measures of sleep quality, may cause autonomic imbalance by triggering a dominance of sympathetic over parasympathetic activity. [9–11 ] In contrast, other studies have proposed that ANS regulation, measured by HRV, is a predictor of subsequent sleep quality and sleep architecture. [12–14] However, no prior studies have comprehensively evaluated the temporal directionality of these associations using a full spectrum of objective sleep measures. More information is also needed on the temporal dynamics between HRV and sleep, i.e., the extent to which their influence is maintained over time, since prior studies assessed primarily short-term effects. [13,15,16] Short-term HRV only captures autonomic flexibility during rest and does not measure the autonomic relationships with sleep and activity. Thus, it offers a limited scope of overall autonomic health. In contrast, measuring long-term HRV over a 24-h period reduces random error due to situational factors, and it averages together the HRV from a mixture of activities during measurement, including physical activity and sleep. Thus, long-term HRV provides a summary of overall autonomic health. Research have also found more robust relationships between long-term HRV and outcomes than short-term HRV. [17],

In addition to limited information regarding the temporal directionality of the association between HRV and sleep, most existing data are based on patients with specific clinical problems, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, narcolepsy, and obstructive sleep apnea. [11,12,18,19] Literature in healthy populations is limited and results have differed. [16,20,21] Furthermore, most prior studies used laboratory-based methods to measure sleep. [14,18,22,23] While this provides a controlled environment, it may not illuminate sleep problems in normal life. [24,25] Finally, no previous study has taken into account the potential influence of familial and genetic factors, which is an important consideration since autonomic regulation and sleep could share common pathophysiology. [26,27]

To address these limitations, we conducted a co-twin control study to evaluate the temporal relationships between autonomic dysregulation indexed by reduced HRV and objectively measured sleep disturbance, using actigraphy data from multiple days. We sought to evaluate the temporal dynamics and directionality of the association between HRV and sleep characteristics. We hypothesized that the association between HRV and sleep would be bidirectional and that the influence of these phenotypes on each other would be relatively brief, within 24 h.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

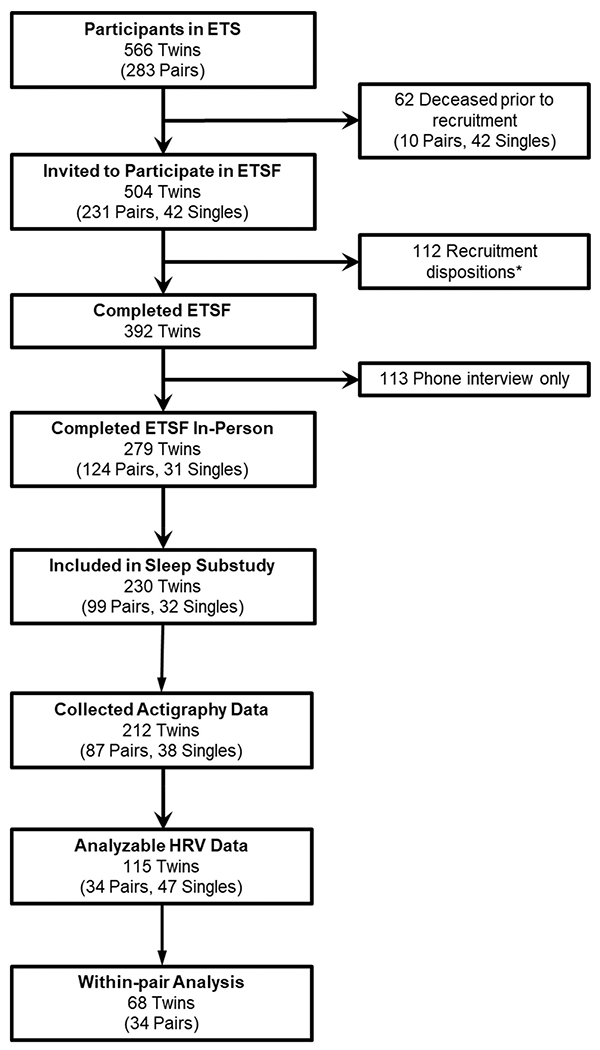

The participants in this study are part of the Sleep Substudy of the Emory Twin Study Follow-up (ETSF). Twins were recruited from the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry, a national registry of >7000 male twins who served on active duty during the Vietnam war. [28] Details on the construction of the study sample are shown in Fig. 1. As part of the ETSF we re-examined in person 279 twins (including 124 pairs and 31 singles) who had participated in the initial Emory Twin Study (ETS). [29,30] The ETS included twin pairs where at least one member had PTSD or major depression, and control pairs free of these psychiatric conditions based on information from previous registry surveys. Twins who self-reported any history of cardiovascular diseases according to 1990–1991 registry data were excluded from ETS. [28] The Sleep Substudy of the ETSF collected objective sleep measures among 230 twins (99 pairs, 32 singles). Of these, a total of 68 paired twins (34 pairs) had good quality autonomic function data and sleep measures obtained at-home, thus they presented the analytical sample for this study.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram. Abbreviations: ETS: Emory Twin Study; ETSF: Emory Twin Study Follow-up; HRV: heart rate variability; PSG: polysomnography. * Recruitment dispositions: 95 never responded or refused to participate; 10 deceased during recruitment; 5 were too ill to participate; 1 withdrew; 1 incarcerated during recruitment.

All twin pairs were examined together at Emory University on the same day to match environmental exposures. Zygosity information was collected and verified by DNA typing. We obtained written informed consent from all participants, and the Institutional Review Board at Emory University approved this study.

2.2. Assessment of sleep

We used actigraphy to obtain an objective evaluation of sleep characteristics. We gave each participant with a wrist-worn actigraph (Actiwatch SpectrumPro, Phillips Respironics) to derive objective sleep metrics in a naturalistic environment. All twins were instructed to wear the device on their non-dominant wrist for up to 7 days. Wrist actigraphy has been recognized as a useful adjunctive tool in sleep medicine. [24,25] It measures body movement over 24-h using a calibrated accelerometer that records physical movement in 1-min epochs. [31] Raw actigraphy data (including activity counts and event markers) were first adjudicated using a sleep diary kept by each participant, and then we applied a standardized scoring algorithm to the data, [32] using Actiwatch software (version 6.0). Various sleep metrics were obtained and summarized for each 24-h day up to 7 days. Our primary actigraphy measures included: (1) TST, the total number of minutes spent asleep during the night; (2) SE, the percentage of the nocturnal sleep period spent asleep; and (3) WASO, the total minutes of wakefulness during the sleep period after sleep onset. A total of 212 twins, including 87 pairs, had usable actigraphy data. All twins had ≥4 days of actigraphy data; almost all (n = 170, 98%) had ≥6 days of data, and most (n = 151, 87%) had 7 days of data. Thus, all twins were included in the analysis to maximize sample size.

2.3. Assessment of autonomic regulation

For HRV data collection, we used the CardeaSolo™ patch, which is a non-invasive and wearable ambulatory ECG monitoring adhesive patch monitor. The device was applied over the left pectoral region of each participant’s chest for up to 7 days. ECG data were extracted and processed using the manufacturer’s custom-built validated software in the same methods as Holter ECG data. [33,34] Both twins in the same pair were evaluated at the same time, and their recording times, schedule, and activity level during recording were similar. On each day, we evaluated four discrete frequency domains (in ms2), including ultra-low frequency (ULF, <0.0033 Hz), very low frequency (VLF, 0.0033–0.04 Hz), low frequency (LF, 0.04–0.15 Hz), and high frequency (HF, 0.15–0.40 Hz). [6,17] We also calculated deceleration capacity (DC) (in ms), which provides an average speed of heart rate deceleration and is potentially more useful than other HRV metrics in evaluating parasympathetic nervous function and predicting adverse events. [35] Data were separated into sleep (nighttime) and wake (daytime) periods as determined by the adjudicated actigraphy data. Twins with low quality data (e.g. loss of electrode contact, movement artifacts, low SQI <90%, or twins with <75% data) were excluded, reducing the number of subjects with usable data to 115 twins, including 34 twin pairs (n = 68) who were included in the within-pair analysis. There were no differences between twins who did (n = 115) and did not have (n = 97) complete HRV assessments in terms of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics (data not shown).

2.4. Other measurements

At the ETSF clinic visit, medical history and medication use was obtained. Anthropometric data, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, lipid profile, and health behaviors were measured as previously described. [36] Habitual physical activity was measured using the Baecke physical activity questionnaire. [37,38] History of hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg, or use of anti-hypertensive medications. [39] History of coronary artery disease that might have occurred from the time of the initial screen was also assessed. Diabetes mellitus was defined as having a measured fasting glucose level > 126 mg/dL or any treatment with antidiabetic medications. A lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and alcohol abuse disorder were obtained using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, 4th Edition, (SCID).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Using actigraphy and ECG data collected during 7-day home monitoring, we evaluated the temporal relationships between sleep and HRV in a naturalistic environment. In a study of twins, within-pair differences intrinsically control for potential confounding by shared genetic factors and early familial background, as well as environmental factors during ambulatory monitoring as twins were examined together. The within-pair analysis included a total of 362 observations (days) reflecting data from 68 twins, and on average, each twin contributed 5.3 observations (days) of data. We fit bivariate vector autoregressive (VAR) models to analyze the longitudinal data. [40] We included each combination of HRV and sleep in separate models. Then for each combination of HRV and sleep measures, we built bivariate VAR models that adjusted for potential confounding factors (smoking status, habitual physical activity, BMI, history of hypertension, and history of depression, PTSD and alcohol abuse). As HRV data were skewed, logarithmic transformations were used to normalize the distributions.

The recording of multiple 24-h periods of simultaneous ECG and actigraphy allowed us to model potential temporal causality using time-lagged models. To determine the length of time the association between HRV and sleep was maintained, we built a series of models by adding lagged values of the dependent variables. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used for order selection, with lower BIC indicating better model fit. To formally test whether the associations between HRV and sleep persist beyond a single 24-h period, we used likelihood ratio tests to compare VAR models with the lowest BIC with the first order models.

After determining the appropriate lag order, to evaluate the temporal directionality of the associations between HRV and sleep, we conducted F tests of Granger causality. In a Granger causality test, if the F-value is statistically significant, it means that the past values of predictor X contain information that helps predict outcome Y in addition to the information contained in the past values of Y alone; in other words, X “Granger-causes” or predicts Y. We individually tested if each of the HRV metric predicted each of the sleep measure, and vice versa, and conducted VAR models separately for wake and sleep periods to evaluate the day and night difference. We further conducted mixed-effects regression models to clarify the direction of significant effects after controlling for the same set of covariates as in the VAR models. In these models, predictor variables were expressed as daily variation from individual’s averages.

A p-value less than 0.05 was used for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Stata, TX).

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ characteristics

A total of 34 paired twins (N = 68) with data collected during home monitoring were included in the within-pair base sample for this study. Among them, 65 (96%) were white, with a mean age ± SD of 69 (2) years (Table 1). Of the 68 twins, 21 pairs (n = 42, 62%) were MZ twins and 13 pairs (n = 26) were DZ twins. Participants’ HRV and sleep data are summarized in Supplemental eTable 1. On average, participants had relatively long TST at home (477 min), 87% SE and 52 min of WASO during home monitoring.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 68 Twins (34 pairs).

| Characteristics, mean (SD), or No. (%) |

Total (N = 68) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | ||

| Age, years | 69 | (2) |

| White, No. (%) | 65 | (96) |

| Education, No. (%) | ||

| High school or less | 12 | (18) |

| Some college or associate | 31 | (46) |

| College degree | 14 | (21) |

| Graduate education or degree | 11 | (16) |

| Employed, No. (%) | 16 | (24) |

| Health factors | ||

| BMI | 29 | (4) |

| Ever smokers, No. (%) | 42 | (62) |

| History of alcohol abuse, No. (%) | 18 | (26) |

| Baecke score for physical activity | 8.0 | (1.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 142 | (21) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80 | (14) |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 36 | (53) |

| History of diabetes, No. (%) | 11 | (16) |

| Family history of CAD, No. (%) | 10 | (15) |

| BDI score | 5.6 | (6.0) |

| PCL-4 score | 26 | (11) |

| Lifetime history of PTSD, No. (%) | 16 | (24) |

| Lifetime history of depression, No. (%) | 12 | (18) |

| Current PTSD, No. (%) | 11 | (16) |

| Current depression, No. (%) | 4 | (6) |

| Medication use | ||

| β-Blockers, No. (%) | 16 | (24) |

| Antidepressants, No. (%) | 9 | (13) |

| Statin, No. (%) | 38 | (56) |

| ACE inhibitor, No. (%) | 14 | (21) |

Abbreviations: ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; PCL-4: PTSD Checklist for DSM-4; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; SD: standard deviation.

3.2. Association of HRV with sleep measured by actigraphy over 7 days

Results of VAR models were examined to identify the most appropriate lag level and best model fit. For all the sleep-HRV pairs, the BIC for the 2-day VAR model was the smallest, indicating the best model fit, for nearly all models examining the association of sleep metrics with daytime or nighttime HRV. Likelihood ratio test results were consistent with BIC (eTables 2–3.) This indicates that 2-day models were significantly more predictive than the 1-day models for both daytime and nighttime HRV across almost all combinations of HRV and sleep metrics. There was no material difference in the results comparing 1-day VAR and 2-day VAR in the models that examined the association of HRV to TST. Therefore, for consistency, Granger causality tests were conducted with the 2-day VAR across all models to examine the temporal directionality.

F test results of Granger causality showed that daytime HRV metrics during the previous days were significantly associated with two sleep measures in the subsequent night, including TST and WASO, after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). These two sleep measures also significantly predicted multiple daytime HRV metrics on the following day. Mixed-effects models provided the directionality for these effects (Fig. 2). Specifically, higher daytime HF and DC HRV predicted subsequent longer TST (F = 3.63 and 5.21, p = 0.03 and 0.01, respectively); and higher ULF, LF, HF and DC HRV predicted decreased WASO (F between 3.07 and 4.91, p between 0.01 and 0.04). Looking at the opposite direction from sleep to subsequent daytime HRV, longer TST and lower WASO predicted higher HRV (F between 3.30 and 7.09, p between <0.01 and 0.04). In contrast, we did not find any significant associations involving nighttime HRV, i.e., between nighttime HRV and sleep measures in subsequent nights, or between sleep measures from previous nights and subsequent nighttime HRV (eTable 4).

Table 2.

F-test Results of Granger Causality for the Within-Pair Association of Daytime Heart Rate Variability and Sleep Disturbance During 7-Day Monitoring Using 48-h Laga,b.

| TST | SE | WASO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direction from Previous Daytime HRV to Sleep | |||

| ULF | 1.98 | 0.69 | 3.07* |

| VLF | 1.71 | 0.26 | 2.48 |

| LF | 1.03 | 1.40 | 4.91* |

| HF | 3.63* | 1.82 | 4.45* |

| DC | 5.21* | 0.96 | 4.53* |

| Direction from Sleep to HRV in Following Day | |||

| ULF | 4.27* | 2.71 | 3.30* |

| VLF | 7.09* | 2.13 | 2.07 |

| LF | 3.78* | 0.57 | 3.80* |

| HF | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.61 |

| DC | 4.25* | 0.88 | 4.34* |

Abbreviations: DC: deceleration capacity; HF: high frequency; HRV: heart rate variability; LF: low frequency; SE: sleep efficiency; TST: total sleep time; ULF: ultra-low frequency; VLF: very low frequency; WASO: wake after sleep onset.

Indicates that the F-value was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Models were fully adjusted for potential confounding factors (smoking status, alcohol abuse, habitual physical activity, body mass index, history of hypertension, depression, and PTSD).

The F test p-values were calculated for overall F statistic = F[2,301]. The exact number of observations and denominator degrees of freedom varied slightly between models due to missing data.

Fig. 2.

Directions of significant effects between daytime heart rate variability with sleep disturbance. Abbreviations: HRV: heart rate variability; TST: total sleep time; WASO: wake after sleep onset.

4. Discussion

In this co-twin control study, we aimed at characterizing the temporal relationships between autonomic dysregulation indexed by reduced HRV, and sleep disturbance objectively measured in multiple dimensions. We found that most of these relationships are bidirectional. During a week of monitoring in the home environment, a higher daytime HRV was bidirectionally associated with better sleep duration and continuity measured by actigraphy, as indicated by longer TST and lower WASO. We also found that the relationships between daytime HRV and sleep duration and continuity measures generally persisted to 48 h, but no longer. In contrast to daytime HRV, nighttime HRV was not related to sleep duration or continuity longitudinally. Because our analysis examined differences within twin pairs, results are largely independent of shared early familial environment.

Our overall findings for actigraphy measures during home monitoring are consistent with prior literature showing that higher HRV predicts better subsequent sleep duration and continuity, although the HRV domains implicated differ across studies. [12–15,41] We observed that all HRV metrics predict indices of better sleep, including longer TST and lower WASO. Of note, DC HRV, which represents changes in PNS activity, demonstrated the most consistent association with both of these sleep measures. LF power is modulated by inputs from sympathetic nervous system to the sino-atrial node; HF power is almost exclusively modulated by vagal tone. [42] Thus, our findings suggest that both sympathetic and vagal indices during the day are involved in sleep duration and continuity. Contrary to previous studies, [14,41,43] however, we did not find significant relationships between HRV and SE, likely because the measure of SE included sleep latency in its calculation. Our findings that daytime HRV rather than nighttime HRV is associated with selected sleep measures, agree with prior studies that assessed HRV both during wakefulness and sleep. [15,44] Using multiple HRV frequency domains and objective sleep duration and continuity measures, our findings suggest that ANS regulation during wakefulness, perhaps reflecting exposures to daily stressors, may alter the sympathovagal balance during the daytime and play a key role in sleep. [45–47]

The existing literature is inconsistent on whether poor sleep duration and continuity can adversely affect, be affected by, or otherwise be associated with HRV. For example, one study showed that subjects with insomnia compared to normal sleepers had decreased HRV, [48] while another study did not find such association. [49] Using a longitudinal, naturalistic design over consecutive 24-h periods, our study extended previous understanding of the temporal relationships between sleep and HRV and showed that TST and WASO, can predict subsequent daytime HRV in multiple domains. It has been noted that low sleep duration and poor sleep continuity can increase sympathetic over parasympathetic dominance, which may be reflected in reduced HRV. [9,10,50] Sleep disturbance may also lead to decreased sensitivity of hormonal receptors such as corticotropin-releasing hormone and serotonin receptors, which may result in dysregulation of stress responses and autonomic function. [9]

Our findings may not be generalizable to women and other racial and age groups, as our sample included mostly white older men. Due to noise and nyquist frequency, the use of 5-min windows to process HRV data may have not generated reliable estimates for lower frequency bands, such as ULF and VLF. In addition, due to the relatively small sample size using home monitoring data, our analysis may have been underpowered to detect significant bidirectional associations across some sleep dimensions. The small sample size also does not allow a reliable evaluation of association separately in monozygotic and dizygotic twins in order to evaluate of role of genetic factors on the association. A reduction in sample size is inevitable in our design, given that within-pair analyses rely on complete pairs and consecutive data are necessary during home monitoring to properly calculate lagged values. However, our co-twin control study design should have improved internal validity and precision by intrinsically adjusting for unknown or unmeasured confounders.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated the temporal dynamics and directionality of relationships between HRV and objective sleep measures over successive 24-h periods and modeled day-night associations in a time-lagged model, allowing inferences via Granger causality. Our approach incorporated objective evaluation of multiple sleep dimensions measured at home. The VAR models fitting bivariate time series and associated Granger causality tests provided an informative method to assess the temporal directionality of associations, and it allowed us to not only evaluate temporal relationships between HRV and sleep, but also the length of time during which HRV exerted effects on sleep and vice versa.

5. Conclusions

In the context of a controlled twin design, the present study provides evidence of a significant bidirectional association between autonomic function and sleep measures. In the home environment, the relationship between autonomic dysregulation during daytime and sleep duration and continuity persists beyond a 24-h period. Specifically, the dysfunction of autonomic regulation indexed by reduced HRV can lead to shorter sleep duration and worse sleep continuity within the subsequent 48 h, and vice versa. Our findings highlight a potential bidirectional mechanism linking autonomic function and sleep with persisting effects, and uncover the importance of a healthy autonomic function in the regulation of sleep and vice versa. These results should inform sleep health promotion strategies, and underscore that targeting daytime autonomic function is a key factor. Furthermore, our study may aide in clarifying the complex relationships between sleep, autonomic regulation, and cardiovascular function. Specifically, our results suggest that autonomic function and sleep health, both of which are cardiovascular risk factors, should be evaluated and managed together, and this approach should have a synergic effect in the prevention of CVD. For example, treatments to improve sleep quality may be aided by pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions to restore autonomic balance, such as exercise training, biofeedback and vagal nerve stimulation.

Supplementary Material

Funding/support

R01 HL68630, R01 AG026255, R01 HL125246, 2K24 HL077506, R01 HL109413, and R01HL136205, AHA 19PRE34450130.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.05.028.

References

- [1].Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA, Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies, Eur. Heart J 32 (2011) 1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Colten HR, Altevogt BM (Eds.), Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem, Washington (DC), 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nagai M, Hoshide S, Kario K, Sleep duration as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease- a review of the recent literature, Curr. Cardiol. Rev 6 (2010) 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Knutson KL, Sleep duration and cardiometabolic risk: a review of the epidemiologic evidence, Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 24 (2010) 731–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC, Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease, Psychosom. Med 67 (Suppl. 1) (2005) S29–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bigger JT Jr, Fleiss JL, Steinman RC, Rolnitzky LM, Kleiger RE, Rottman JN, Frequency domain measures of heart period variability and mortality after myocardial infarction, Circulation. 85 (1992) 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dekker JM, Crow RS, Folsom AR, Hannan PJ, Liao D, Swenne CA, et al. , Low heart rate variability in a 2-minute rhythm strip predicts risk of coronary heart disease and mortality from several causes: the ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis risk in communities, Circulation. 102 (2000) 1239–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tsuji H, Larson MG, Venditti FJ Jr, Manders ES, Evans JC, Feldman CL, et al. , Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events. The Framingham Heart Study, Circulation. 94 (1996) 2850–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meerlo P, Sgoifo A, Suchecki D, Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity, Sleep Med. Rev 12 (2008) 197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Michels N, Clays E, De Buyzere M, Vanaelst B, De Henauw S, Sioen I, Children’s sleep and autonomic function: low sleep quality has an impact on heart rate variability, Sleep. 36 (2013) 1939–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Urbanik D, Gac P, Martynowicz H, Poreba M, Podgorski M, Negrusz-Kawecka M, et al. , Obstructive sleep apnea as a predictor of reduced heart rate variability, Sleep Med. 54 (2019) 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Burton AR, Rahman K, Kadota Y, Lloyd A, Vollmer-Conna U, Reduced heart rate variability predicts poor sleep quality in a case-control study of chronic fatigue syndrome, Exp. Brain Res 204 (2010) 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fantozzi MPT, Artoni F, Faraguna U, Heart rate variability at bedtime predicts subsequent sleep features, Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc 2019 (2019) 6784–6788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jung DW, Lee YJ, Jeong DU, Park KS, New predictors of sleep efficiency, Chronobiol. Int 34 (2017) 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Werner GG, Ford BQ, Mauss IB, Schabus M, Blechert J, Wilhelm FH, High cardiac vagal control is related to better subjective and objective sleep quality, Biol. Psychol 106 (2015) 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jackowska M, Dockray S, Endrighi R, Hendrickx H, Steptoe A, Sleep problems and heart rate variability over the working day, J. Sleep Res 21 (2012) 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kleiger RE, Miller JP, Bigger JT Jr., Moss AJ, Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction, Am. J. Cardiol 59 (1987) 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li X, Covassin N, Zhou J, Zhang Y, Ren R, Yang L, et al. , Interaction effect of obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movements during sleep on heart rate variability, J. Sleep Res 28 (2019), e12861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aslan S, Erbil N, Tezer FI, Heart rate variability during nocturnal sleep and daytime naps in patients with narcolepsy type 1 and type 2, J. Clin. Neurophysiol 36 (2019) 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Holmes AL, Burgess HJ, Dawson D, Effects of sleep pressure on endogenous cardiac autonomic activity and body temperature, J. Appl. Physiol 2002 (92) (1985) 2578–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhong X, Hilton HJ, Gates GJ, Jelic S, Stern Y, Bartels MN, et al. , Increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic cardiovascular modulation in normal humans with acute sleep deprivation, J. Appl. Physiol 2005 (98) (1985) 2024–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Aeschbacher S, Bossard M, Schoen T, Schmidlin D, Muff C, Maseli A, et al. , Heart rate variability and sleep-related breathing disorders in the general population, Am. J. Cardiol 118 (2016) 912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kikuchi T, Kasai T, Tomita Y, Kimura Y, Miura J, Tamura H, et al. , Relationship between sleep disordered breathing and heart rate turbulence in non-obese subjects, Heart Vessel. 34 (2019) 1801–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Poliak CP, The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms, Sleep. 26 (2003) 342–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Lichstein KL, Morin CM, Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia, Sleep. 29 (2006) 1155–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Calandra-Buonaura G, Provini F, Guaraldi P, Plazzi G, Cortelli P, Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunctions and sleep disorders, Sleep Med. Rev 26 (2016) 43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fink AM, Bronas UG, Calik MW, Autonomic regulation during sleep and wakefulness: a review with implications for defining the pathophysiology of neurological disorders, Clin. Auton. Res 28 (2018) 509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tsai M, Mori AM, Forsberg CW, Waiss N, Sporleder JL, Smith NL, et al. , The Vietnam Era Twin Registry: a quarter century of progress, Twin. Res. Hum. Genet 16 (2013) 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, Shah AJ, Veledar E, Faber TL, et al. , Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 62 (2013) 970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Scherrer JF, Xian H, Bucholz KK, Eisen SA, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, et al. , A twin study of depression symptoms, hypertension, and heart disease in middle-aged men, Psychosom. Med 65 (2003) 548–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ancoli-Israel S, Martin JL, Blackwell T, Buenaver L, Liu L, Meltzer LJ, et al. , The SBSM guide to actigraphy monitoring: clinical and research applications, Behav. Sleep Med 13 (Suppl. 1) (2015) S4–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC, Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity, Sleep. 15 (1992) 461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Glass L, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov PC, Mark RG, et al. , PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals, Circulation. 101 (2000) E215–E220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vest AN, Da Poian G, Li Q, Liu C, Nemati S, Shah AJ, et al. , An open source benchmarked toolbox for cardiovascular waveform and interval analysis, Physiol. Meas 39 (2018), 105004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bauer A, Kantelhardt JW, Barthel P, Schneider R, Makikallio T, Ulm K, et al. , Deceleration capacity of heart rate as a predictor of mortality after myocardial infarction: cohort study, Lancet. 367 (2006) 1674–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Vaccarino V, Lampert R, Bremner JD, Lee F, Su S, Maisano C, et al. , Depressive symptoms and heart rate variability: evidence for a shared genetic substrate in a study of twins, Psychosom. Med 70 (2008) 628–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE, A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies, Am. J. Clin. Nutr 36 (1982) 936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, Jacobs DR Jr, Leon AS, Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure-time physical activity, Int. J. Epidemiol 24 (1995) 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr., et al. , Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, Hypertension. 42 (2003) 1206–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Granger C, Testing for causality: a personal viewpoint, J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2 (1980) 329–352. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gouin J, Wenzel K, Deschenes S, Dang-Vu T, Heart rate variability predicts sleep efficiency, Sleep Med. 14 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kleiger RE, Stein PK, Bigger JT Jr., Heart rate variability: measurement and clinical utility, Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol 10 (2005) 88–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Elmore-Staton L, El-Sheikh M, Vaughn B, Arsiwalla DD, Preschoolers’ daytime respiratory sinus arrhythmia and nighttime sleep, Physiol. Behav 107 (2012) 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Irwin MR, Valladares EM, Motivala S, Thayer JF, Ehlers CL, Association between nocturnal vagal tone and sleep depth, sleep quality, and fatigue in alcohol dependence, Psychosom. Med 68 (2006) 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Thayer JF, Yamamoto SS, Brosschot JF, The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors, Int. J. Cardiol 141 (2010) 122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Brosschot JF, Van Dijk E, Thayer JF, Daily worry is related to low heart rate variability during waking and the subsequent nocturnal sleep period, Int. J. Psychophysiol 63 (2007) 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G, Endocrinology of the stress response, Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67 (2005) 259–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bonnet MH, Arand DL, Heart rate variability in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers, Psychosom. Med 60 (1998) 610–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fang SC, Huang CJ, Yang TT, Tsai PS, Heart rate variability and daytime functioning in insomniacs and normal sleepers: preliminary results, J. Psychosom. Res 65 (2008) 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Akerstedt T, Psychosocial stress and impaired sleep, Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 32 (2006) 493–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.