Abstract

The RecA proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae contain inteins. In contrast to the M. tuberculosis RecA, the M. leprae RecA is not spliced in Escherichia coli. We demonstrate here that M. leprae RecA is functionally spliced in Mycobacterium smegmatis and produces resistance toward DNA-damaging agents and homologous recombination.

The RecA protein is a central component of the SOS response, which involves expression of a regulon comprising more than 20 unlinked genes and operons (17). The SOS response is characterized by an increased capacity for DNA repair and mutagenesis (9). In the pathogenic mycobacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae, the recA gene is comprised of a single open reading frame, which is interrupted by an intein coding sequence (2, 4). These two protein introns are different in size, sequence, and location of insertion of their coding sequences into the respective recA genes (4), suggesting that they have been acquired independently. In general, inteins are excised precisely from the precursor protein, and the flanking exteins are ligated to form the mature protein (3, 7, 8, 12). A wide variety of heterologous systems have been used to demonstrate splicing, and most of the available evidence points to the fact that protein splicing is an autocatalytic reaction, which does not require the involvement of accessory molecules (14). In contrast to the M. tuberculosis RecA, the 79-kDa precursor protein of the M. leprae RecA is spliced only in the native organism and not in Escherichia coli (4).

Thus, it was inferred that the M. leprae RecA intein may provide an example of conditional protein splicing, with the splicing reaction requiring some accessory mycobacterial protein or with the splicing activity controlled by a regulatory protein, although the possibility remained that the failure to splice in E. coli was a result of incorrect protein folding (1, 4).

Mycobacterium smegmatis recA mutant strain KS (5) was transformed with the E. coli-mycobacterium shuttle vector pRML-58a, a derivative of pHint (6) carrying a 4.1-kbp SphI/ClaI M. leprae recA fragment; this vector integrates at the mycobacterial attB site. Successful integration was demonstrated by PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). For further investigations, M. smegmatis recA mutant strains complemented with M. tuberculosis recA (KS recA::aph/recA+ M. tuberculosis) or M. smegmatis recA (KS recA::aph/recA+ M. smegmatis) were used as controls.

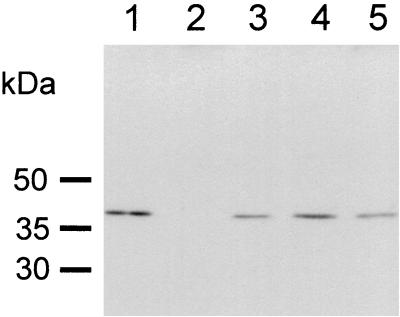

Expression of RecA was investigated after ofloxacin induction (1 μg/ml for 5 h) (5, 11), by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1). A single band of approximately 38 kDa is found in protein extracts from the recA+ strain M. smegmatis mc2 155 SMR5 (lane 1) but is absent from M. smegmatis KS recA::aph (lane 2). Upon complementation of the recA mutant with recA genes from M. smegmatis (lane 3), M. tuberculosis (lane 4), and M. leprae (lane 5), RecA expression is found. Significantly, M. smegmatis recA mutant cells complemented with pRML-58a show a protein with a molecular mass of 38 kDa, indicating expression of the mature form of the introduced M. leprae recA gene. Although the antiserum used is able to recognize the unspliced precursor form of the M. leprae RecA protein (79 kDa), a protein with a corresponding molecular mass is not observed.

FIG. 1.

Detection of mycobacterial RecA protein in extracts from M. smegmatis. Lane 1, mc2 155 SMR5; lane 2, KS recA::aph; lane 3, KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. smegmatis); lane 4, KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. tuberculosis); lane 5, KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. leprae L58a). Approximately 10 μg of protein was loaded on a 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate gel, electroblotted, and developed following incubation with antiserum raised against M. tuberculosis RecA. The antiserum cross-reacts with the RecA proteins from M. leprae, M. tuberculosis, and M. smegmatis.

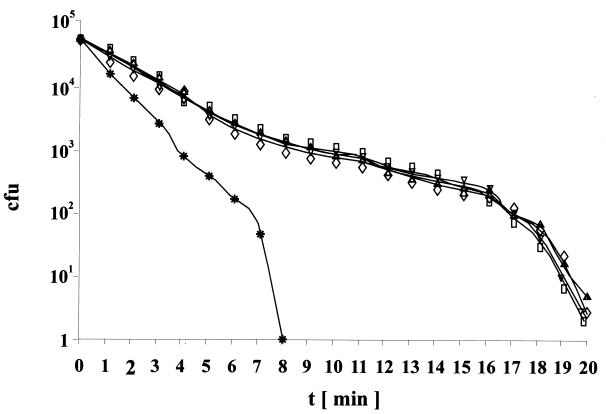

To functionally characterize the M. leprae RecA, complemented M. smegmatis recA mutant cells were investigated with respect to the ability to perform DNA repair following treatment with DNA-alkylating agents (ethyl methanesulfonate-methyl methanesulfonate) or UV irradiation (5). Transformation of M. smegmatis KS recA::aph with pRML-58a fully restored the wild-type phenotype, i.e., growth in the presence of ethyl methanesulfonate-methyl methanesulfonate (data not shown), and resistance to UV irradiation (Fig. 2) of the complemented strain was indistinguishable from that of recA+ mc2 155 SMR5 and from that of the KS recA::aph strains complemented with the recA gene from M. tuberculosis or M. smegmatis, respectively.

FIG. 2.

UV resistance of M. smegmatis recA mutant complemented with recA from M. smegmatis, M. tuberculosis, and M. leprae. Symbols: triangles, M. smegmatis mc2 155 SMR5; stars, KS recA::aph; diamonds, KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. smegmatis); inverted triangles, KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. tuberculosis); rectangles, KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. leprae L58a). The ability to form colonies after UV irradiation was determined by plating dilutions on 7H10 agar plates. The number of CFU was calculated after 3 days of incubation at 37°C.

The ability of the M. leprae RecA protein to catalyze homologous recombination was investigated by transformation experiments. M. smegmatis recA+ and M. smegmatis recA mutant complemented with M. smegmatis or M. leprae recA were transformed with a suicide vector targeting pyrF (5). The number of clones obtained by transformation of KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. leprae L58a) with the suicide vector pHRM-Gm (5) and subsequent selection on gentamicin was comparable to the number of transformants obtained upon transformation of the parental recA+ strain M. smegmatis mc2 155 SMR5 or the recA mutant strain complemented with M. smegmatis recA. In contrast, no transformants were obtained upon transformation of the recA mutant strain (Table 1). These data suggest that the M. leprae RecA is able to mediate integration of exogenous nucleic acids by homologous recombination.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of homologous recombination

| Strain | Transformation efficiency with:

|

Growthe

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMV261-rRNA2058Ga | pHRM-Gmb | On GM-STRc | Without uracild | On FOA | |

| mc2 155 SMR5 | 1 × 106 | 0.6 × 102 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 |

| KS recA::aph | 3 × 105 | 0 | ND | ND | ND |

| KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. smegmatis) | 6.5 × 105 | 0.4 × 102 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 |

| KS recA::aph/recA+ (M. leprae L58a) | 5.1 × 105 | 0.5 × 102 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 |

Selection was performed in the presence of clarithromycin (50 μg/ml); vector pMV261-rRNA2058G (16) was used to control for transformation efficiency.

Selection was performed in the presence of gentamicin (30 μg/ml).

Following selection on gentamicin (GM) and streptomycin (STR), five clones each were picked and investigated for their drug susceptibility.

Five gentamicin- and streptomycin-resistant clones each were investigated.

Number of clones that grew/total number investigated. ND, not done.

Transformants obtained by positive selection with gentamicin are expected to result from a single crossover (15). These transformants possess one functional and one inactivated copy of pyrF and thus cannot be differentiated phenotypically from the parental pyrF+ strain. To verify that transformants obtained with the suicide vector pHRM-Gm resulted from homologous recombination at the pyrF locus, transformants were subjected to a second counterselection (30 μg of gentamicin per ml and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml [15]) to result in intrachromosomal recombination and deletion of the wild-type pyrF gene. Transformants resistant to gentamicin and streptomycin were investigated for their PyrF phenotype. pyrF mutants are uracil auxotrophs and resistant to fluoroorotic acid (FOA), a toxic analog of orotic acid. All gentamicin- and streptomycin-resistant derivatives obtained by counterselection from the recA+ strain and the strains of the KS recA::aph mutant complemented with the recA fragments from M. smegmatis and M. leprae, respectively (five of five each investigated), were uracil dependent and FOA resistant, indicating allelic exchange of pyrF by two successive homologous crossover events (Table 1).

Since the discovery of protein splicing (7, 8), much effort has been devoted to the elucidation of the biochemical reactions that underlie the protein splicing process and to the identification of the catalytic groups and the structural elements of inteins that participate in protein splicing (14). The intein plus the first downstream extein residue contain sufficient information for the splicing reaction to occur. For efficient splicing of an intein, four nucleophilic attacks mediated by three of four conserved splice junction residues are required: a serine, threonine, or cysteine at the intein N terminus; an asparagine at the intein C terminus; and a serine, threonine, or cysteine at the downstream extein N terminus. A penultimate histidine at the C terminus of the intein assists the cleavage reaction (13).

The M. tuberculosis RecA intein is 440 amino acids in size and flanked by a cysteine at the intein N terminus, an asparagine at the intein C terminus, and a cysteine at the downstream extein N terminus. The intein of the M. leprae RecA is 365 amino acids in size and is also flanked by a cysteine at the intein N terminus and an asparagine at the intein C terminus but carries a serine at the downstream extein N terminus (4). In the case of the M. tuberculosis RecA, the protein was spliced appropriately when expressed in E. coli and the protein splicing reaction was found to occur in trans when using purified N- and C-terminal fragments of the intein (10). In contrast, the M. leprae 79-kDa RecA precursor protein is not spliced in E. coli (4). It was thus suggested that the M. leprae RecA intein might represent an example of conditional protein splicing (4).

M. smegmatis is a nonpathogenic mycobacterium which is frequently used in mycobacterial genetics. This species has a single contiguous, i.e., inteinless, RecA, similar to most other eubacterial species. M. smegmatis recA mutant strains are unable to promote homologous recombination (5, 11). Using complementation of the M. smegmatis recA mutant, it has been possible for the first time to perform functional investigations of the M. leprae RecA. Previously, the M. leprae RecA intein was found to splice in M. leprae itself but not when expressed in E. coli. Complementation of an M. smegmatis recA mutant strain with the M. leprae recA gene fully restored the RecA+ phenotype with respect to DNA repair as well as with respect to integration of exogenous nucleic acids by homologous recombination; in addition, a mature 38-kDa RecA protein was detected by immunoblotting. Presumably, if some accessory mycobacterial protein is required for functional splicing of the M. leprae RecA intein, M. smegmatis must provide some enzymatic activity allowing splicing of the M. leprae RecA precursor protein. More likely, in M. smegmatis, but not in E. coli, the RecA protein is folded properly, enhancing the self-splicing reaction. In this regard, it should be noted that the rate of synthesis of the precursor protein may be instrumental in enabling correct folding, for in M. smegmatis the M. leprae RecA was expressed from its own promoter, whereas in E. coli it was expressed from the strong T7 promoter, partly because its native promoter did not function in E. coli (4).

Acknowledgments

We thank Douglas Young for providing plasmid pHint-1, K. G. Papavinasasundaram for RecA antiserum, Anke Meyerdierks for help with Western blot analysis, and Kerstin Ellrott for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Schwerpunktprogramm Ökologie bakterieller Krankheitserreger).

REFERENCES

- 1.Colston M J, Davis E O. The ins and outs of protein splicing elements. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis E O, Sedgwick S G, Colston M J. Novel structure of the recA locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis implies processing of the gene product. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5653–5662. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5653-5662.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis E O, Jenner P J, Brooks P C, Colston M J, Sedgwick S G. Protein splicing in the maturation of M. tuberculosis RecA protein: a mechanism for tolerating a novel class of intervening sequence. Cell. 1992;71:201–210. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90349-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis E O, Thangaraj H S, Brooks P C, Colston M J. Evidence of selection for protein introns in the RecA's of pathogenic mycobacteria. EMBO J. 1994;13:699–703. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frischkorn K, Sander P, Scholz M, Teschner K, Prammananan T, Böttger E C. Investigation of mycobacterial recA function: protein introns in the RecA of pathogenic mycobacteria do not affect competency for homologous recombination. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1203–1214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garbe T R, Birathi J, Barnini S, Zhang Y, Abou-Zeid C, Tang D, Mukherjee R, Young D B. Transformation of mycobacterial species using hygromycin resistance as selectable marker. Microbiology. 1994;140:133–138. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirata R, Ohsumi Y, Nakano A, Kawasaki H, Suzuki K, Anraku Y. Molecular structure of a gene, VMA1, encoding the catalytic subunit of H+-translocating adenosine triphosphatase from vacuolar membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6726–6733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kane P M, Yamashiro C T, Wolczyk D F, Neff N, Goebl M, Stevens T H. Protein splicing converts the yeast TFP1 gene product to the 69kD subunit of the vacuolar H+-adenosine triphosphatase. Science. 1990;250:651–657. doi: 10.1126/science.2146742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kowalczykowski S C, Dixon D A, Eggleston A K, Lauder S D, Rehrauer W M. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:401–465. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.401-465.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills K V, Lew B M, Jiang S-Q, Paulus H. Protein splicing in trans by purified N- and C-terminal fragments of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis RecA intein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3543–3548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papavinasasundaram K G, Colston M J, Davis E O. Construction and complementation of a recA deletion mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis reveals that the intein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis recA does not affect RecA function. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:525–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perler F B, Comb D G, Jck W E, Moran L S, Quiang B, Kucera R B, Benner J, Slatko B E, Nwankwo D O, Hempstead S K, Carlow C K S, Jannasch H. Intervening sequences in an archaea DNA polymerase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5577–5581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perler F B, Olsen G J, Adam E. Compilation and analysis of intein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1087–1093. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perler F B, Xu M Q, Paulus H. Protein splicing and autoproteolysis mechanisms. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;1:292–299. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sander P, Meier A, Böttger E C. rpsL+: a dominant selectable marker for gene replacement in mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:991–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander P, Prammananan T, Meier A, Frischkorn K, Böttger Erik C. The role of ribosomal RNA in macrolide resistance. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:469–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5811946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker G C. SOS-regulated proteins in translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:416–420. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]