Abstract

Background:

Human exposures to organophosphate flame retardants result from their use as additives in numerous consumer products. These agents are replacements for brominated flame retardants but have not yet faced similar scrutiny for developmental neurotoxicity. We examined a representative organophosphate flame retardant, triphenyl phosphate (TPP) and its potential effects on behavioral development and dopaminergic function.

Methods:

Female Sprague–Dawley rats were given low doses of TPP (16 or 32 mg/kg/day) via subcutaneous osmotic minipumps, begun preconception and continued into the early postnatal period. Offspring were administered a battery of behavioral tests from adolescence into adulthood, and littermates were used to evaluate dopaminergic synaptic function.

Results:

Offspring with TPP exposures showed increased latency to begin eating in the novelty-suppressed feeding test, impaired object recognition memory, impaired choice accuracy in the visual signal detection test, and sex-selective effects on locomotor activity in adolescence (males) but not adulthood. Male, but not female, offspring showed marked increases in dopamine utilization in the striatum, evidenced by an increase in the ratio of the primary dopamine metabolite (3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid) relative to dopamine levels.

Conclusions:

These results indicate that TPP has adverse effects that are similar in some respects to those of organophosphate pesticides, which were restricted because of their developmental neurotoxicity.

Keywords: Developmental neurotoxicity, Dopamine, Flame retardants, Neurobehavioral dysfunction, Triphenyl phosphate

Introduction

Flame retardant chemicals are commonly found in electronics, textiles, foams used in furniture, and various building materials. Unfortunately, these additives are often mobile, allowing for human exposure through absorptive materials like household dust (Hoffman, 2015; Percy, 2020; Stapleton, 2008). Of potential concern, these compounds have been detected in samples from pregnant women (Bai, 2019; Castorina, 2017a; Hoffman, 2017; Zhao, 2017) and in breastmilk (Adgent, 2014; Ma, 2019), indicating that prenatal and infant exposures are common. As with other environmental toxicants, multiple classes of flame retardants have been introduced, phased out and replaced based on their potential toxicity, with older generations including polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers. However, their replacements, largely organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs, e.g. triphenyl phosphate) were introduced as supposedly lower-risk alternatives but with relatively little toxicological data to support the idea that they represented an improvement from older classes. OPFRs may target nervous system development, as other OP have been shown to. Indeed, some OPFRs inhibit acetylcholinesterase (Kinugasa, 2001), the target for organophosphate insecticides, but the OPFRs also exhibit a range of other cellular and physiological effects that can affect development (See review (Patisaul, 2021)), including endocrine disruption, neuroinflamation, oxidative stress, shifts in neural/glial determination, differentiation and morphology, and disruption of neurotransmission.

Prenatal or neonatal exposure to OPFRs is associated with adverse developmental and cognitive effects in children, including hyperactivity, deficits in fine motor performance, language, and working memory, as well as reduced IQ and externalizing behaviors (Castorina, 2017b; Doherty, 2019; Lipscomb ST, 2017). These human studies are supported by a range of behavioral toxicology studies in animals investigating OPFRs or OPFR-containing mixtures such as Firemaster-550. Studies with lower-vertebrate fish models, such as zebrafish, found both short- and long-term behavioral changes following embryonic individual OPFR exposures, including changes in larval motility, locomotor activity, anxiety-like diving, startle responses and predator avoidance (Dishaw, 2014; Glazer, 2018; Noyes, 2015; Oliveri, 2015; Sun, 2016). Likewise, rodent studies have noted long-term affective and locomotor effects in rodent offspring exposed to OPFR mixtures during fetal or neonatal development (Baldwin, 2017; Walley, 2021; Wiersielis, 2020; Witchey, 2020), further indicating that the neurotoxic potential of OPFR is well conserved across vertebrate species. These findings raise the possibility that individual or mixed OPFRs may impact developmental toxicity, similar to structurally-similar organophosphate pesticides, a class of compounds that have been increasingly restricted because of those effects, which include behavioral dysfunction associated with structural and synaptic neurochemical disruption, with dopamine systems as a prominent target in rodent offspring (Hawkey, 2022; Karen, 2001; Slotkin, 2007; Slotkin et al., 2009). Notably, another OPFR, tris (1,3-dichloropropyl) phosphate, which contains both the organophosphate moiety as well as halogens, has been shown to promote hyperdevelopment of the dopaminergic phenotype in vitro (Dishaw, 2011). What remains less clear is to what degree a simpler OPFR, devoid of halogen moieties, mimics the overall neurotoxic and behavioral profiles of known OP neurotoxicants and mixtures.

The present study was conducted to evaluate behavioral and dopaminergic consequences in offspring with maternal TPP exposure (0, 3.95 or 7.58 mg/day, corresponding to an initial dose of 16-32 mg/kg/day). TPP was selected as a representative OPFR based on its frequent detection in indoor environmental samples (Hartmann, 2004; Mizouchi, 2015; Phillips, 2018; Zheng, 2017), and because of its inclusion in common OPFR mixtures like Firemaster 550 (FM550). TPP was delivered by osmotic minipump to maintain around-the-clock exposure, with treatment occupying the entire gestational period and into the second postnatal week. Offspring were then subjected to a battery of behavioral tests to evaluate cognitive, locomotor and emotional function. In addition, we evaluated the impact on dopaminergic synaptic function, measuring dopamine levels and utilization (turnover). The latter was assessed by calculating the ratio of the chief dopamine metabolite, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) to dopamine (Slotkin et al., 2009). Dopamine is critical for cognition and emotional processing (Abraham et al., 2014; Puig et al., 2014), as well as for a broader array of behavioral functions, and as noted above, it has been documented to be targeted by OP insecticides.

Methods

Subjects and Housing

Subjects consisted of Sprague Dawley rats (Charles Rivers Labs, Raleigh, NC, USA) and their offspring, which were bred in house. Animals were kept on a 12/12 reversed day:light cycle and provided with ad libitum access to food/water throughout breeding and early offspring development. Restricted feeding was used in three behavioral tests among offspring to promote motivated feeding behaviors (see below). A total of 36 adult female Sprague Dawley breeder rats were used to generate offspring for testing (10-14 per condition, as needed based on mating success to generate 8+ litters). All offspring were housed in social housing (2-3 rats per cage) with all members of a given cage representing either males or females of a given treatment condition. All surgical, husbandry and testing procedures were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University. The animal protocol approval number is A253-19-11 and the facility is AAALAC approved.

Minipump Implantation, Mating and TPP Exposure

A total of 36 adult female Sprague Dawley ratswere surgically implanted with subcutaneous Alzet osmotic infusion pumps (2ML4, Durect Inc, Cupertino, CA, USA) under anaesthesia (60mg/kg ketamine, Covetrus, Dublin, OH, USA, and 15mg/kg dexdormitor, Dechra, Overland Park, KS, USA). TPP (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO, USA, Lot#BCC88784) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used to fill a single osmotic pump per animal for implantation. Solutions (100% DMSO + powdered TPP) were determined to provide doses of 0, 16 or 32mg/kg/day of TPP, based on dam weight at the time of surgery. Control groups received identical pumps with 100% DMSO vehicle alone. The corresponding outputs of the osmotic minipumps were, on average, 0, 3.95 or 7.58 mg/day TPP. Rats were then allowed to recover for 72 hours prior to mating, and pumps remained in place until weaning (postnatal day PN21) of any resulting litters. Mating consisted of each female being housed with an untreated male rat for 5 days. These doses were selected based on preliminary experiments that established the tolerability during pregnancy, defined as falling below the threshold for disrupted fertility or for growth impairment in dams and offspring. These pumps are marketed as a 4-week delivery device, but they actually last 5 weeks (information supplied by the manufacturer). Consequently, in our study, TPP exposure lasted throughout pregnancy and up to 8-11 days into the neonatal stage. Corresponding to human neurodevelopmental stages from conception into the third trimester (Semple, 2013). Dam weights increased during gestation, resulting in an average 25% reduction in dose rate by the time of birth, after which the dose rates rose back to nearly the original values because of the weight loss associated with parturition. Throughout the gestation and pre-weaning period, maternal health and signs of distress was monitored daily through visual inspection, including lethargy, piloerection, discolored fur, and subcutaneous fluid buildup around the osmotic pumps. Handling was kept to a minimum needed to verify health, except in the case of fluid buildup, which was addressed by draining excess fluid and application of a topical cream (triple antibiotic cream).

At PN1 (the day of birth was designated as PN0), all offspring were weighed and litters were culled such that the number of remaining offspring did not exceed 10, and so that numbers of males and females were balanced, as available in each litter. At weaning, one randomly-selected male and female were selected from each litter and were housed in same-sex groups for subsequent rearing and behavioral testing. All remaining siblings were retained for tissue collection for the neurochemical studies, which likewise utilized only one male and one female from each litter at each time point. Weaning was performed at 21 days of age, and rats selected for the behavioral study were group housed with same-sex, same-condition offspring (2-3 rats per cage, based on pregnancy success) originating from other litters. These social housing groups were maintained for the duration of the study. Offspring used in the neurochemistry study were housed with same-sex littermates (2-3 rats per cage, based on sex-balance within litter) and rats were removed at set ages for tissue collection. Behavioral testing began 1-week after weaning, whereas tissue samples for neurochemistry were obtained at PN60, PN100 and PN150.

Behavioral Testing of the Offspring

The behavioral battery consisted of seven tests, described in detail below (Table 1), with only one test being performed during any given week of development. Assessment began at 4 weeks of age and included tests of locomotor, affective, and cognitive function. All testing was performed during the dark phase of the reversed day/night cycle and under the low-level ambient light of the dark phase of the cycle (800 hr–1700 hr). The same animals completed all behavioral tests sequentially. During the radial arm maze and attention task testing, rats were food restricted to maintain weight at 85% of free feeding levels, while allowing for developmentally appropriate weight gain (e.g. daily food was adjusted across the training and testing phases of each test). Appropriate levels were verified by consistent task engagement and weight gain, and daily food allotments were adjusted if needed to return the rats to the target restriction level.

Table 1. Maternal TPP Exposure and Behavioral Testing of Offspring.

Treatment and testing schedule for TPP exposure and behavioral assessment of their offspring. One test was performed in any given week, with testing beginning at 4 weeks of age.

| Week | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8-11 | 12-40 | Post-OVSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Test | Elevated Plus Maze | Figure-8 Maze | Novel Env. Suppressed Feeding | Novel Object Recognition | Radial Arm Maze | Operant Visual Signal Detection | Figure-8 Maze |

Week 4: Elevated Plus Maze

At 4 weeks of age, rats were tested in the elevated plus maze (Med Associates, St Albans, VT, USA). This test assessed open space aversion in these young animals, a characteristic which is associated with anxiety-like avoidance of space with an elevated risk of predation. Increased preference for enclosed spaces is generally interpreted as enhanced anxiety-like responses, while a greater open space preference is interpreted as reduced risk avoidance. The apparatus consisted of a central hub (11.5 x 11.5cm) with 4 equally spaced arms extending from it (11.5 x 50cm). Two of these arms were bordered with 15-cm high walls, while the other two were bordered by 2-cm railings. Each rat was allowed to freely explore the maze for one 5 min session. The two primary dependent variables were the time spent in the open arms of the maze and the number of center hub crossings (indicative of exploration and general locomotor activity).

Week 5 and Adulthood: Figure-8 Locomotor Activity Test

At 5 weeks of age, offspring were tested for locomotor activity and locomotor habituation in the figure-8 maze. The figure-8 maze was an enclosed locomotor chamber (70cm x 42cm) made of sheet metal walls with a Plexiglas lid. This included a continuous 10cm x 10cm alley which formed the shape of the number 8 with two side alleys extending from its center. Photobeams were placed at 8 equally spaced locations throughout the maze to detect movement throughout the apparatus. Offspring were allowed to freely explore the maze for 1-hour. Locomotor activity, and its attenuation across the 1h session (habituation) were measures as number of beam breaks per 5-min session block (x 12). The linear trend of locomotion reductions across the session represented the rate of habituation. This test was repeated in adulthood, after completion of the signal detection task (see below).

Week 6: Novelty Suppressed Feeding

At 6 weeks of age, offspring were tested for fear/stress responsivity in the novel environment suppressed feeding test. This test leveraged the resistance of rats to freely eat food when in a novel, mildly stressful environment to detect the intensity of fear/stress-like responses (Roegge, 2008). In this test, offspring rats were food restricted for 24h and then taken to a novel, bright room. Each rat was then individually placed into an empty (no bedding) plastic cage identical to its home cage with sat in the middle of the floor with no lid on top. Twelve rat chow pellets were placed in 4 rows of 3 pellets along the floor of the cage. This food was weighed prior to and immediately after a 10 min session, where rats were allowed to freely explore the cage and eat. The difference in food weight before vs after the session indicated food consumption. While the session was running, experimenters scored the eating behavior of each animal, including the total time spent eating, the number of bouts of eating, and the latency to begin eating. Eating was defined as visibly/audibly chewing the food, and not unrelated investigation of the food such as niffing, holding or carrying the food pellets.

Week 7: Novel Object Recognition

At 7 weeks of age, offspring were tested for attention and memory in the novel object recognition test. This test represents basic memory processes in a low-motivational state, where behavior is not reinforced or punished by any consequence. Initially, offspring were acclimated to the testing apparatus, a 10 cm x 41 cm black plastic box, twice over two days (10 min each). To demonstrate familiarization and memory, offspring then completed two investigation sessions separated by one hour. During the first session (AA), two corners of the enclosure contained randomly selected, identical objects to be investigated. These objects were made of glass, plastic or ceramic and offspring were allowed to freely investigate them for 10 min. During the second (AB) session, one of the previously investigated objects was replaced with a novel object of similar size and material, but with distinct visual characteristics (shape, color, etc). Again, offspring were allowed to freely investigate the two objects for 10 min. Between testing sessions and between animals, the enclosure and objects were wiped with a 10% vinegar solution to remove latent odors. Collected videos of each investigation session were analyzed for the time spent investigating each object, defined as sniffing of the object. Climbing on or touching the objects, in the absence of sniffing, was excluded. Each 10-min session was then split into two 5 min blocks, to allow within-session changes in investigation due to familiarization to be assessed. Typically, time spent investigate with diminish over the course of the 10 min session, as, will preference for the novel object within the AB session. The primary dependent measures were the time spent investigating each object, the difference in investigation between the two co-presented objects (preference), and the change in each of these scores from the first to second 5 min block. Graphed data (Fig. 3) represent the difference in investigation between the two co-presented objects (novel object investigation time – familiar object investigation time), interpreted as the magnitude of object discrimination or novelty preference.

Figure 3.

Gestational TPP exposure effects on novel object recognition, novel-familiar investigation (s), relative to vehicle exposed control rats (mean ± sem). A treatment x object interaction was observed, F(2, 23) = 4.26, p < 0.05, and follow-up tests were performed on the net investigation difference between objects (novel – familiar) within each group. The 32 mg/kg/day group differed from controls on their relative preference for the novel object (p <0.05).

Week 8-11: Radial-Arm Maze

From weeks 8-11 of age, offspring were maintained on restricted feeding to facilitate food-motivated behavior and tested for spatial learning and memory in the 16 arm radial arm maze. This configuration of the test is designed to detect both short- and long-term memory function in one test, conducted over 12 sessions. The apparatus consisted of a central hub (50 cm diameter) with 16, 10cm x 60 cm arms radiating out from it. Each arm ended with a food cup 2 cm from the end of the arm. To aid navigation throughout the maze, cardboard shapes were placed on the walls. Training began with 10 min acclimation sessions over two days, whereby each rat was placed in a round black cylinder in the middle of the central hub and allowed to eat pieces of sugar-coated cereal (Froot Loops®; Kellogg’s Inc, Battle Creek, MI, USA). This was done to ensure that these rats would readily eat the food rewards during subsequent testing. For the remainder of training, the offspring were provided with one daily session, whereby they would explore the maze and retrieve any rewards from the ends of the maze arms. During these sessions, 12 of the 16 arms had food hidden at the end, and 4 were left empty. The positions of baited/unbaited arms were randomized for each rat and kept consistent across the 12 training sessions. Sessions ran until the rat successfully entered all baited arms or when 10 minutes had elapsed, whichever came first. Arm entries were scored by an observer and split into correct responses and two types of errors. Any entry into an arm which was never baited throughout training was scored as a reference memory error. Any repeated entry into an arm which was typically baited was scored as a working memory error. Arm entry latency was calculated as the total time of the session divided by the total number of arm entries.

Weeks 12-40: Operant Visual Attention Task

Following the end of radial arm maze testing, offspring remained on restricted feeding, and completed training and testing in the operant signal detection, or visual attention, test (Holloway, 2020). This test measured the accuracy of choices made by the rats based on the presence or absence of a visual cue prior to that choice. All training and testing was conducted in a standard operant chamber equipped with two retractable levers, a visual cue light, and automated feeder which dispensed 20mg sucrose pellets. Training began by using an autoshaping procedure (4 sessions) to develop reliable lever processing responses and continued with training on two distinct trial types. On cued or “signal” trials, the cue light, placed immediately above the associated lever, was illuminated for 500 ms and turned off before both levers were presented. The position (left, right) of the light/associated lever was counterbalanced across rats and kept constant throughout training and testing. A lever press on the associated side resulted in the delivery of a sucrose pellet. On non-cued or “blank” trials, the two levers were delivered without a prior light flash. On these trials, presses on the non-light associated lever (on the opposite side) led to pellet delivery. On either trial type, if no response was made within 5s, the trial ended and “no response” was recorded. Trial types were trained individually (50-trial sessions of cued-trials until 96% accuracy criterion reached (48/50 trials), then the same with blank trials). Following this, 100-trial sessions included both cued and blank trials, first sequentially (50 cued, 50 blank, completion criterion 99% accuracy) and then on a multiple schedule (mixed within session) (completion criterion 70% total accuracy). During this latter phase, the light position was transferred from being above the associated lever to a centered position at the top of the wall. On the tertiary testing phase, accuracy and performance was recorded across a 240 trial session (120 presentations of each, randomized) and this data was used for the primary analysis. Performance criteria for data inclusion on the tertiary phase was a minimum of 70% average accuracy across the two trial types. Accuracy was measured as follows: Correct responses during “signal” trials were recorded as hits, and calculated as a percentage of all “signal” trials (% correct). Correct responses during “blank” trials were recorded as correct rejections, and likewise calculated as a percentage of all “blank” trials. Data analysis focused on performance within this final phase of testing (light centered, 240 trial multiple schedule sessions), and on the percent correct responses for each trial type.

Neurochemistry

Animals were euthanized via decapitation at PN60, PN100 and PN150, and the striatum (all ages) and frontal/parietal cortex (PN100, PN150) were dissected and frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C until utilized. Tissues were deproteinized by homogenization in 0.1 N perchloric acid containing 3,4-dihydroxybenzylamine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis MO, USA) as an internal standard. Homogenates were sedimented at 26,000 × g for 10 min and supernatants were trace-enriched by alumina adsorption. Dopamine and DOPAC were separated by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography, and quantitated by electrochemical detection (Seidler & Slotkin, 1981), standardized against external standards containing 3,4-dihydroxybenzylamine and known quantities of dopamine (Sigma) and DOPAC (Sigma); values were corrected for recovery of the internal standard. Transmitter utilization was then calculated by the DOPAC/dopamine ratio, so as to assess the proportion of dopamine released into the synapse (Slotkin et al., 2009). In the frontal/parietal cortex, we simultaneously measured the level of another catecholamine neurotransmitter, norepinephrine.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), with factors of TPP treatment and sex (repeated measure within litter). As relevant to each test, additional within-subjects repeated measures were also included, such as time block, training session, or trial type. For neurochemistry, the test factors were TPP treatment, sex, age and brain region (repeated measure); statistical tests on neurochemistry required log transformation because of heterogeneous variance between regions. For all tests, significance was assumed at the level of p<0.05 (two-tailed). For interactions at p<0.1, we also examined whether lower-order simple main effects were detectable (at p<0.05) after subdivision of the interactive variables (Snedecor, 1967). The p<0.1 criterion for interaction terms was not used to assign significance to the effects but rather to identify interactive variables requiring subdivision for lower-order tests of the main effects of TPP, the variable of chief interest. Individual group comparisons were performed using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test. Fertility rates, litter health and growth are presented in the main body as are all significant findings within behavioral and neurochemical analysis (Table 2, Fig. 1–5). Non-significant effects and summaries of outcomes by sex are presented in supplementary tables (Tables S1–S4).

Table 2. Developmental Health Measurements.

Developmental health measurements of conception success (% preg.), offspring weight gain, litter size sex ratio (mean ± sem). No treatment effects were detected.

| Litter Information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | % Preg. | Litter Size | % Male |

| Control | 58% | 10 ± 0.6 | 50 ± 3.8 |

| TPP 16 | 90% | 12 ± 1.0 | 48 ± 5.3 |

| TPP 32 | 69% | 9.4 ± 1.3 | 56 ± 6.9 |

| Body Weight (g) (by Postnatal Day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 21 |

|

| |||||||

| Control | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 10.6 ± 0.4 | 13.2 ± 0.5 | 18.6 ± 0.6 | 25.1 ± 0.8 | 42.2 ± 1.5 | 56.3 ± 5.7 |

| TPP 16 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 9.7 ± 0.6 | 13.3 ± 0.8 | 17.9 ± 0.9 | 24.6 ± 1.3 | 40.5 ± 1.3 | 59.7 ± 2.0 |

| TPP 32 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 10.3 ± 0.4 | 12.5 ± 0.4 | 16.7 ± 0.8 | 23.7 ± 0.6 | 38.8 ± 0.9 | 58.8 ± 3.0 |

| Females | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 21 |

|

| |||||||

| Control | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.4 | 12.6 ± 0.5 | 18.0 ± 0.6 | 24.1 ± 1.0 | 40.2 ± 1.6 | 53.9 ± 5.5 |

| TPP 16 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 0.9 | 17.7 ± 1.0 | 24.3 ± 1.3 | 39.7 ± 1.5 | 57.3 ± 2.1 |

| TPP 32 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 9.9 ± 0.3 | 12.1 ± 0.3 | 16.6 ± 0.6 | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 38.0 ± 1.1 | 57.3 ± 3.0 |

Figure 1.

Gestational TPP exposure effects on figure-8 maze locomotor activity in adolescent and adult rats, relative to vehicle exposed control rats (mean ± sem). In adolescents there was a TPP treatment x sex interaction (F(2,32)=3.10, p < 0.06) that triggered tests of the simple main effects of TPP in males and females. There was a significant main effect of treatment in males, F(1,32)=5.06, p < 0.05, but not females (p > 0.05). In adolescence, males from the 32 mg/kg/day group differed from control males on their average number of beam breaks per 5 min time block (p < 0.05). No effects were detected among adult rats.

Figure 5.

Gestational TPP exposure effects on neurochemical assays in striatal (upper) and frontal-parietal cortical tissue (lower) (mean ± sem). DOPAC analyses observed a sex x tissue x treatment interaction, F(1,41) = 4.1, p < 0.05, whereby DOPAC was increased in the 32 mg/kg/day group in the male striatum. DOPAC/dopamine ratio also showed a sex x tissue x treatment interaction, F(2,65) = 8.0, p < 0.0008, whereby this ratio was increased in the 16 and 32 mg/kg/day groups in the male striatum.

Results

Clinical Signs of Fertility and Neonatal Health

During and following exposure, several key signs of clinical health were recorded and analyzed Neither TPP treatment reduced fertility nor did they evoke changes in litter size, sex-ratio, body weights or anogenital distance (Table 2).

Elevated Plus Maze Test of Anxiety-like Behavior

On the elevated plus maze, the primary outcomes were percent preference for the open arms of the maze and number of center crossings (Table S1). For open arm preference, there was an interaction of TPP exposure x sex (p < 0.10) which prompted follow-up tests of the simple main effects of TPP in each sex. Group comparisons with Fisher’s LSD test showed that in females the high dose group spent significantly more time in the open arms (p<0.05) than did the low dose group but neither TPP group was significantly different from controls. No significant group differences were seen for males. No main effects of treatment or interactions of treatment with other variables were detected for center crossings.

Figure-8 Apparatus Locomotor Activity

For the figure-8 maze, locomotor activity was assessed across time (5 min blocks) and at two ages (adolescence vs. adult). In adolescents there was a TPP treatment x sex interaction (p < 0.06) that triggered tests of the simple main effects of TPP in males and females (Fig. 1). This showed that for the males 32 mg/kg/day of TPP during gestation caused a significant (p < 0.05) increase in activity relative to controls. In adults there were no TPP exposure-related effects, although there were significant main effects of sex (p < 0.05), showing typical sex differences (female > male) and session block (p < 0.05) where activity diminishes over time. To support interpretation of age-differences, a secondary analysis including age as a repeated-measures variable showed no overall age x sex x treatment or age x treatment interaction, indicating that the TPP effects detected above should not be interpreted as distinctly age-specific.

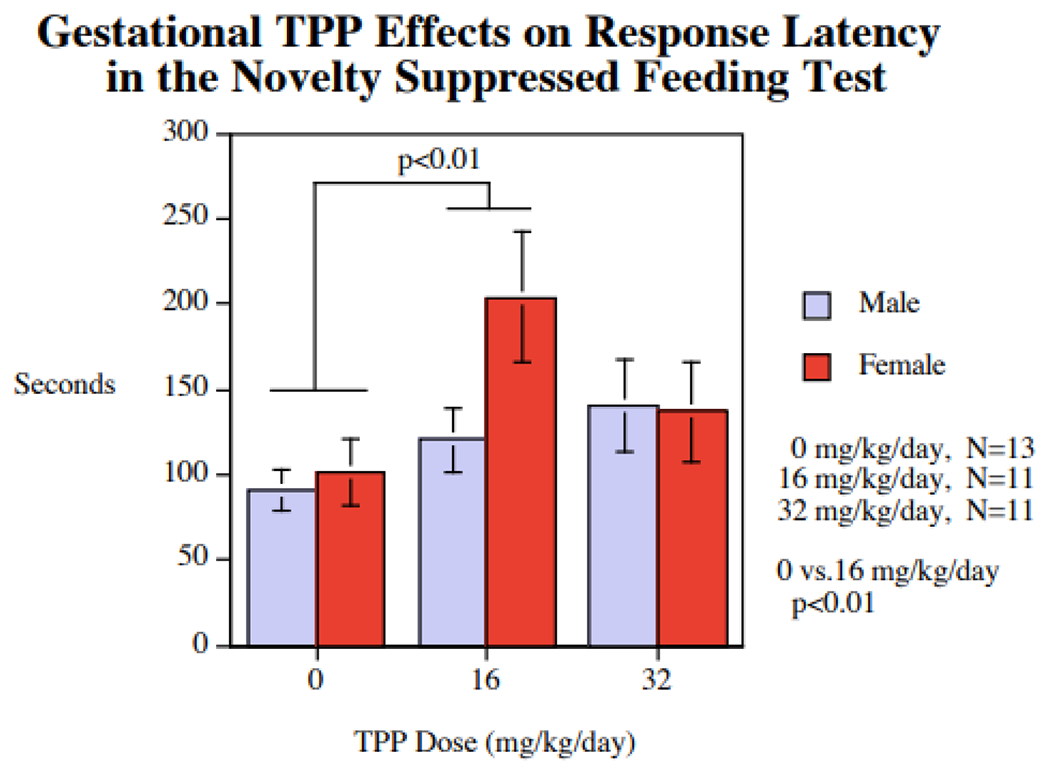

Novelty Suppressed Feeding Test of Fear Response

For novel environment suppressed feeding, the primary outcomes were latency to begin feeding, time spent eating, number of eating bouts and amount of food eaten. For latency to begin eating, there was a main effect of TPP treatment (p < 0.05), whereby offspring exposed to 16mg/kg/day waited longer to begin eating compared to controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). The two TPP-treated groups did not significantly differ from one another on this outcome. No other measures showed significant effects of treatment or relevant interactions. Typical sex differences in latency to eat (male < female) were not significantly detected.

Figure 2.

Gestational TPP exposure effects on response latency (s) in the novelty suppressed feeding test, relative to vehicle exposed control rats (mean ± sem). For latency to begin eating (square root of seconds), there was a main effect of TPP treatment, F(2,32)=3.92, p < 0.05, whereby offspring exposed to 16mg/kg/day waited longer to begin eating compared to controls, F(1,32)=7.57, p < 0.01. The 16 mg/kg/day group differed from controls on the latency to begin eating during the test (p < 0.05).

Novel Object Recognition Test of Non-spatial Memory

The novel object recognition test measured the difference in investigation between the novel and familiar object in the AB session, and the change in this score from the first to the second half of the session (first half – second half). A TPP x object (familiar vs. novel) interaction (p<0.05) was detected which prompted follow-up with tests of the effects of TPP on novel preference. We found that the offspring exposed to 32 mg/kg/day of TPP exhibited significantly less novel object preference compared to controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3), but not the 16 mg/kg/day group. Unrelated to TPP treatment, there were also significant main effects of object (familiar vs. novel) (p < 0.05) and 5-min time block of the session (p < 0.05). Sex x treatment interactions did not reach significance, although visible trends (TPP-related impairments in females appear more dramatic than males) may assist in interpretation, as provided in the supplemental materials (Table S2).

16-Arm Radial Maze Test of Spatial Learning and Memory

For the radial arm maze, the primary outcomes were the numbers of errors (working vs reference memory) and response latency. With errors, there was a significant TPP x error type interaction (p < 0.05). However, after subdivision into the error types, we did not detect significant TPP-related effects on either working or reference memory (Table S3), nor was there a significant TPP effect on response latency. Typical sex differences (error rates, male < female) in task performance and accuracy were not significantly detected.

Operant Visual Signal Detection Test

For the operant visual signal detection test, the primary outcomes were choice accuracy across two trial types (“signal” vs “blank” trials). There was a significant interaction of TPP x trial type (p < 0.05). Follow-up tests of the simple main effects of TPP with each trial type showed a significant TPP effect on correct reject trials (p < 0.05), with the TPP 32 group distinguishable from both the controls and the 16 mg/kg/day group (Fig. 4). A full sex x treatment summary is provided in the supplemental materials (Table S4).

Figure 4.

Gestational TPP exposure effects on percent correct performance for hit and correct rejection trials in the visual signal detection attention test (mean ± sem). A treatment x trial type interaction was detected, F(2, 23) = 7.28, p < 0.05, and follow-up tests were performed on each trial type separately. The 32 mg/kg/day group differed from both controls and the 16mg/kg/day group in correct rejection accuracy (non-cued trials) (p < 0.05), but not hit accuracy (cued trials).

Neurochemistry

Neurochemical analyses principally examined tissue levels of dopamine, DOPAC, and DOPAC/dopamine ratio in the striatum and frontal/parietal cortex of offspring animals, with additional assessment of norepinephrine in the frontal/parietal cortex (Fig. 4). To enable ready visual comparison of all the different parameters, values are shown as the percent change from control, with the original values provided in Table 3. Effects of TPP exposure were specific to the striatum (Figure 4A), with no corresponding effects in the frontal/parietal cortex (Figure 4B). In the striatum, TPP effects were sex-selective, with males showing significant synaptic hyperactivity (elevated DOPAC and DOPAC/dopamine ratio), whereas females were unaffected.

TABLE 3: TPP Effects on Dopamine (DA), DOPAC and Norepinephrine (NE).

Full results of Dopamine (Striatum, upper; Frontal-Parietal Cortex, Lower) and Norepinephrine (PFC) assays. Data (mean ± SEM) obtained from 6-12 animals in each treatment group for each age and sex.

| Region | Postnatal Age (days) | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA ng/g | Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

|

| striatum | 60 | 6631 ± 268 | 6379 ± 156 | 6466 ± 250 | 6619 ± 401 | 6353 ± 181 | 5792 ± 307 |

| 100 | 7514 ± 447 | 6716 ± 406 | 7040 ± 653 | 7236 ± 489 | 6906 ± 408 | 7156 ± 536 | |

| 150 | 7850 ± 780 | 7495 ± 592 | 7247 ± 763 | 7381 ± 761 | 7373 ± 814 | 8193 ± 758 | |

| frontal/parietal cortex | 100 | 450 ± 28 | 437 ± 36 | 448 ± 34 | 437 ± 21 | 373 ± 27 | 451 ± 36 |

| 150 | 884 ± 67 | 825 ± 97 | 846 ± 77 | 713 ± 54 | 740 ± 57 | 721 ± 55 | |

| DOPAC ng/g | Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

|

| striatum | 60 | 825 ± 49 | 895 ± 69 | 1011 ± 115 | 958 ± 78 | 819 ± 84 | 863 ± 99 |

| 100 | 598 ± 32 | 671 ± 32 | 641 ± 48 | 681 ± 45 | 693 ± 30 | 654 ± 56 | |

| 150 | 624 ± 116 | 594 ± 57 | 718 ± 74 | 693 ± 67 | 607 ± 93 | 720 ± 74 | |

| frontal/parietal cortex | 100 | 70 ± 2 | 71 ± 4 | 78 ± 6 | 65 ± 2 | 65 ± 5 | 77 ± 3 |

| 150 | 132 ± 11 | 116 ± 9 | 126 ± 14 | 113 ± 8 | 121 ± 7 | 116 ± 10 | |

| % DOPAC/DA | Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

|

| striatum | 60 | 12.5 ± 0.8 | 14.1 ± 1.2 | 15.7 ± 1.7 | 14.3 ± 0.8 | 13.3 ± 1.1 | 14.8 ± 1.5 |

| 100 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.5 | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 9.6 ± 0.6 | 12.2 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 0.7 | |

| 150 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 0.6 | |

| frontal/parietal cortex | 100 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | 17.0 ± 1.1 | 17.7 ± 1.2 | 15.0 ± 0.6 | 18.1 ± 1.4 | 17.9 ± 1.2 |

| 150 | 15.2 ± 1.5 | 15.9 ± 1.2 | 15.2 ± 1.7 | 16.2 ± 1.1 | 16.6 ± 0.8 | 16.4 ± 1.3 | |

| NE ng/g | Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

Control | TPP 16 mg/kg |

TPP 32 mg/kg |

|

| frontal/parietal cortex | 100 | 170 ± 5 | 176 ± 7 | 177 ± 7 | 168 ± 6 | 172 ± 5 | 176 ± 8 |

| 150 | 288 ± 23 | 292 ± 13 | 287 ± 14 | 272 ± 17 | 275 ± 8 | 292 ± 14 | |

Discussion

Our studies support the conclusion that TPP, a supposedly safer replacement for polybrominated flame retardants, is a neurobehavioral teratogen. Chronic maternal exposure to TPP during perinatal development evoked neurobehavioral and neurochemical anomalies which persisted into adulthood. Importantly, we chose exposures that were devoid of effects on fertility, growth or viability, and thus would escape the definition of developmental toxicity as assessed simply by gross examination. The affected behaviors included both affective and cognitive performance: male-specific hyperactivity in adolescence, enhanced fear-like avoidance of eating in a novel environment, reduced novel object recognition, and choice accuracy deficits in the visual signal detection test, associated with increased dopamine utilization of striatal tissue of males.

Maternal TPP exposure led to a specific cluster of behavioral symptoms which complement prior animal studies and epidemiological associations between developmental OP exposure and cognitive/affective outcomes later in life. TPP notably targeted many of the same outcomes as other, better studied OP compounds, but often caused unique profiles of impairment within those outcomes. Sex-specific effects included male-driven increases in locomotor activity, and male-driven increases in adolescent locomotor activity. Superimposed on the sex-selective effects, we found effects shared by both sexes, including enhancements in novelty-induced suppression of eating initiation, an indication greater fear-like stress responses, and impaired novel object recognition, indicating interference with non-spatial memory processes under a low motivational state.

The four tests sensitive to early life exposure to TPP have been previously shown to be sensitive to similar exposures to other OP pesticides and flame retardant mixtures (Chen, 2011, 2014; Hawkey, 2020; Roegge, 2008), although the exact TPP-effects are partially distinct from the other OPs. For example, locomotor effects of other OPs include hyperactivity, but not necessarily with the same sex-selectivity. For example, prenatal diazinon exposure leads to female-, rather than male-, specific hyperactivity (Hawkey, 2020). By contrast, chlorpyrifos exposure on GD9-12 or PND 11-14 produced female-specific increases or general reductions in locomotor habituation respectively (Icenogle, 2004; Levin, 2001; Roegge, 2008) with no main effect on activity levels. With respect to novelty-suppressed feeding, TPP appears to be distinguishable from diazinon, which reduces latency to feed in males (Roegge, 2008).

With respect to novel object recognition, developmental exposures to the OP insecticides, diazinon or malathion, produce impairments in novel object discrimination (Hawkey, 2020; N’Go, 2013; Win-Shwe, 2013). Prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos, by contrast, was shown to enhance object investigation overall among males, without disrupting object discrimination (Levin, 2014). This suggests that some, but not all OP exposures may impair this outcome. With respect to the signal detection task, TPP appears unique from diazinon in producing choice impairments when no cue was presented (“blank” trials” or correct rejections). Prenatal diazinon exposure was found to impair choice accuracy regardless of trial type in middle-aged, but not young adult rats (Hawkey, 2020; Hawkey, 2022). Overall, it is concluded that TPP, a representative OP flame retardant, shares the liability of developmental neurotoxicity of the OP insecticides, but that it also has a number of unique effects. Some of these differences may reflect kinetic and metabolic properties. For example, OP insecticides generate toxic oxon-forms through metabolism (Mutch, 2006; Poet, 2003), which are believed to contribute to the overall neurotoxicity of these compounds and their anti-cholinesterase properties ((Betancourt, 2004)). TPP, by contrast, is primarily metabolized into intermediate phenyl phosphates (e.g. hydroxylated TPPs and diphenyl phosphate) (Marteinson, 2020; Su, 2014) which may contribute to neurotoxicity in distinct ways.

With respect to TPP-alone vs TPP-containing mixtures, the present data suggest additional areas of agreement and potential differences. TPP-containing mixtures have been previously associated with changes in locomotor activity and/or open space avoidance (Baldwin, 2017; Walley, 2021; Wiersielis, 2020; Witchey, 2020). Similar to the current study, Patisaul and colleagues found male-specific FM550-induced hyperactivity among juvenile rats in the open field, while no similar effects were observed in adulthood (Baldwin, 2017; Witchey, 2020). In mice, Roepke and colleagues found that a mixture of TDCPP, TPP and TCP led to female-specific effects in the open field test in certain cases, but not others (Walley, 2021; Wiersielis, 2020). Additionally, each of these studies identified alterations in open space avoidance or similar anxiety-like outcomes, which were found to be spared in the elevated plus maze within the present study. Taken together, these similarities and differences may indicate that locomotor effects of OPFR mixtures may be partially attributable to TPP, while anxiolytic or anxiogenic effects may be more closely associated with other OPFR within those mixtures. It should also be noted that existing studies of TPP-containing mixtures have largely focused on locomotor and affective functions, and the present data emphasizes that cognitive outcomes, such as recognition memory and attentional function, can be sensitive to OPFR effects as well, and should be included in future work in this area. While the present work complements prior rodent work, it should be acknowledged that the symptom cluster observed does not fully account for behavioral associations noted in human studies (e.g. fine motor impairments, working memory deficits), and as such, additional studies will be needed to fully model and explain the bases of OPFR-induced behavioral dysfunction.

As with the OP insecticides, the behavioral anomalies were associated with lasting neurochemical changes in dopamine systems, characterized by increased dopamine utilization (turnover). However, we were unable to connect the neurochemical effects to specific behavioral outcomes, as the latter did not completely share the sex-selectivity seen for neurochemistry (males only). It would require an expanded battery of tests to determine whether there are specific links between increased dopamine utilization and specific behavioral defects. Importantly though, prior studies have shown that developmental exposure to OP pesticides likewise leads to increased dopamine utilization (Slotkin, 2007), just as seen here for TPP. So, these effects may be common to OPs regardless of whether they are insecticides or flame retardants.

One notable limitation highlighted in this study pertains to the role of varying kinetics in the effects observed. The osmotic pumps used in this study model a consistent, steady source of environmental exposure, which while theoretically “natural” does not provide a steady internal dose. The maternal dose per kg of body weight was estimated to reduce by ~25% by the time of birth due to gestational weight gain. As a result, the kinetic profile during gestation provides greater levels of exposure during early stages of fetal development than during later stages. These factors may influence the variability of this dataset, as weight gain, and therefore relative dose, will necessarily vary across individuals within each maternal group. Additionally, lactational exposure during the neonatal period, equated with the third trimester of human brain development, has not been quantified so the offspring dose at this point cannot be precisely stated. The pump method is valuable insofar as it reduces the repeated handling and gestational stress associated with repeated injections or gavage, but this benefit is tempered somewhat by the lack of kinetic stability. Future studies in this area will need to provide a more comprehensive assessment of exposure kinetics using these pumps, and/or adopt osmotic pumps which can be externally programmed to provide a more precise and weight-appropriate output of the candidate toxin. Such future studies will be able to clarify which aspects of the present work may depend on the unique characteristics of this exposure method, and which are more representative across methods.

In summary, the current study identified multiple neurobehavioral and neurochemical consequences of perinatal TPP exposure at otherwise subtoxic exposures. The effects partially overlap those associated with OP pesticides while at the same time, and often target previously identified outcomes of interest, yet evidence suggests that the risks associated with TPP are distinct from other Ops, or better aligned with some representative compounds than others. The developmental neurotoxicity of the OP pesticides and older generations of flame retardants (e.g. PBDEs) has been more rigorously assessed, and while these chemicals have been restricted or banned, studies like the current work emphasize that replacement compounds require a similar level of scrutiny. While there is ample evidence to support the conclusion that the continued use of OPs, whether insecticides or flame retardants, confers some risk of developmental neurotoxicity, there are distinctions among the various OP compounds, so that those risks are not identical across the broad array of OPs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Duke University Superfund Research Center ES010356. TAS and FJS were responsible for the neurochemical measurements.

Footnotes

COI statement

TAS has received consultant income in the past three years from Edelson PC (Chicago, IL), Wicker Smith (Naples, FL), Gjording Fouser (Boise, ID), Thorsnes Bartolotta McGuire (San Diego, CA), Cracken Law (Dallas, TX), Matthews Law (Houston, TX), Segal Law (Charleston, WV), Armstrong Teasdale (St. Louis, MO), CNA Continental Casualty Company (Chicago, IL), The National Association of Attorneys General (Washington, DC) and the State of Arizona.

References

- Abraham AD, Neve KA, & Lattal KM (2014). Dopamine and extinction: a convergence of theory with fear and reward circuitry. Neurobiol Learn Mem, 108, 65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adgent MA, Hoffman K, Goldman BD, Sjödin A and Daniels JL (2014). Brominated flame retardants in breast milk and behavioural and cognitive development at 36 months. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology, 28(1), 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai XY, Lu SY, Xie L, Zhang B, Song SM, He Y, Ouyang JP and Zhang T (2019). A pilot study of metabolites of organophosphorus flame retardants in paired maternal urine and amniotic fluid samples: potential exposure risks of tributyl phosphate to pregnant women. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 21(1), 124–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin KR, Phillips AL, Horman B, Arambula SE, Rebuli ME, Stapleton HM, & Patisaul HB (2017). Sex specific placental accumulation and behavioral effects of developmental Firemaster 550 exposure in Wistar rats. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt AM, & Carr RL (2004). The effect of chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos-oxon on brain cholinesterase, muscarinic receptor binding, and neurotrophin levels in rats following early postnatal exposure. Toxicological Sciences, 77(1), 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castorina R, Bradman A, Stapleton HM, Butt C, Avery D, Harley KG, Gunier RB, Holland N and Eskenazi B (2017b). Current-use flame retardants: maternal exposure and neurodevelopment in children of the CHAMACOS cohort. Chemosphere, 189, 574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castorina R, Butt C, Stapleton HM, Avery D, Harley KG, Holland N, Eskenazi B and Bradman A (2017a). Flame retardants and their metabolites in the homes and urine of pregnant women residing in California (the CHAMACOS cohort). Chemosphere, 179, 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQ, Yuan L, Xue R, Li YF, Su RB, Zhang YZ, & Li J (2011). Repeated exposure to chlorpyrifos alters the performance of adolescent male rats in animal models of depression and anxiety. Neurotoxicology, 32(4), 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQ, Zhang YZ, Yuan L, Li YF, & Li J (2014). Neurobehavioral evaluation of adolescent male rats following repeated exposure to chlorpyrifos. Neuroscience Letters, 570, 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishaw LV, Hunter DL, Padnos B, Padilla S, & Stapleton HM (2014). Developmental exposure to organophosphate flame retardants elicits overt toxicity and alters behavior in early life stage zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicological Sciences, 142(2), 445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishaw LV, Powers CM, Ryde IT, Roberts SC, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, & Stapleton HM (2011). Is the PentaBDE replacement, tris (1, 3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCPP), a developmental neurotoxicant? Studies in PC12 cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 256(3), 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty BT, Hoffman K, Keil AP, Engel SM, Stapleton HM, Goldman BD, Olshan AF and Daniels JL (2019). Prenatal exposure to organophosphate esters and cognitive development in young children in the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition Study. Environmental research, 169, 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer L, Hawkey AB, Wells CN, Drastal M, Odamah KA, Behl M and Levin ED, 2018. Developmental exposure to low concentrations of organophosphate flame retardants causes life-long behavioral alterations in zebrafish. Toxicological Sciences, 165(2), 487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann PC, Bürgi D, & Giger W (2004). Organophosphate flame retardants and plasticizers in indoor air. Chemosphere, 57(8), 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey A, Pippen E, White H, Kim J, Greengrove E, Kenou B, Holloway Z and Levin ED (2020). Gestational and perinatal exposure to diazinon causes long-lasting neurobehavioral consequences in the rat. Toxicology, 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey AB, Pippen E, Kenou B, Holloway Z, Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ, & Levin ED (2022). Persistent neurobehavioral and neurochemical anomalies in middle-aged rats after maternal diazinon exposure. Toxicology, 472, 153189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Garantziotis S, Birnbaum LS and Stapleton HM (2015). Monitoring indoor exposure to organophosphate flame retardants: hand wipes and house dust. Environmental health Perspectives, 123(2), 160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Lorenzo A, Butt CM, Adair L, Herring AH, Stapleton HM and Daniels JL (2017). Predictors of urinary flame retardant concentration among pregnant women. Environment International, 98, 96–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icenogle LM, Christopher NC, Blackwelder WP, Caldwell DP, Qiao D, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA and Levin ED (2004). Behavioral alterations in adolescent and adult rats caused by a brief subtoxic exposure to chlorpyrifos during neurulation. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 26(1), 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karen DJ, Li W, Harp PR, Gillette JS, Bloomquist JR (2001). Striatal dopaminergic pathways as a target for the insecticides permethrin and chlorpyrifos. Neurotoxicology, 22, 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinugasa H, Yamaguchi Y, Miyazaki N, Okumura M, & Yamamoto Y (2001). Evaluation of toxicity in the aquatic environment based on the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 67(4), 696–702. [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Addy N, Nakajima A, Christopher NC, Seidler FJ, & Slotkin TA . (2001). Persistent behavioral consequences of neonatal chlorpyrifos exposure in rats. Developmental Brain Research, 130(1), 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Cauley M, Johnson JE, Cooper EM, Stapleton HM, Ferguson PL, Seidler FJ and Slotkin TA (2014). Prenatal dexamethasone augments the neurobehavioral teratology of chlorpyrifos: significance for maternal stress and preterm labor. Neurotoxicology and teratology, 41, 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST MM, MacDonald M, Cardenas A, Anderson KA, Kile ML. Cross-sectional study of social behaviors in preschool children and exposure to flame retardants. Environ Health. 2017;16(1):23. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Zhu H and Kannan K (2019). Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in breast milk from the United States. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 6(9), 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteinson S, Guigueno MF, Fernie KJ, Head JA, Chu S, & Letcher RJ (2020). Uptake, Deposition, and Metabolism of Triphenyl Phosphate in Embryonated Eggs and Chicks of Japanese Quail (Coturnix japonica). Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 39(3), 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizouchi S, Ichiba M, Takigami H, Kajiwara N, Takamuku T, Miyajima T, Kodama H, Someya T and Ueno D (2015). Exposure assessment of organophosphorus and organobromine flame retardants via indoor dust from elementary schools and domestic houses. Chemosphere, 123, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutch E, & Williams FM (2006). Diazinon, chlorpyrifos and parathion are metabolised by multiple cytochromes P450 in human liver. Toxicology, 224(1-2), 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N’Go PK, Azzaoui FZ, Ahami AOT, Soro PR, Najimi M, & Chigr F (2013). Developmental effects of Malathion exposure on locomotor activity and anxiety-like behavior in Wistar rat. Health, 5(3), 603–611. [Google Scholar]

- Noyes PD, Haggard DE, Gonnerman GD and Tanguay RL, 2015. Advanced morphological—behavioral test platform reveals neurodevelopmental defects in embryonic zebrafish exposed to comprehensive suite of halogenated and organophosphate flame retardants. Toxicological Sciences, 145(1), 177–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri AN, Bailey JM, & Levin ED (2015). Developmental exposure to organophosphate flame retardants causes behavioral effects in larval and adult zebrafish. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 52, 220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patisaul HB, Behl M, Birnbaum LS, Blum A, Diamond ML, Rojello Fernández S, Hogberg HT, Kwiatkowski CF, Page JD, Soehl A and Stapleton HM (2021). Beyond Cholinesterase Inhibition: Developmental Neurotoxicity of Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers. Environmental Health Perspectives, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy Z, La Guardia MJ, Xu Y, Hale RC, Dietrich KN, Lanphear BP, Yolton K, Vuong AM, Cecil KM, Braun JM and Xie C (2020). Concentrations and loadings of organophosphate and replacement brominated flame retardants in house dust from the home study during the PBDE phase-out. Chemosphere, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AL, Hammel SC, Hoffman K, Lorenzo AM, Chen A, Webster TF, & Stapleton HM (2018). Children’s residential exposure to organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers: investigating exposure pathways in the TESIE study. Environment International, 116, 176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poet TS, Wu H, Kousba AA, & Timchalk C (2003). In vitro rat hepatic and intestinal metabolism of the organophosphate pesticides chlorpyrifos and diazinon. Toxicological Sciences, 72(2), 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig MV, Rose J, Schmidt R, & Freund N (2014). Dopamine modulation of learning and memory in the prefrontal cortex: insights from studies in primates, rodents, and birds. Front Neural Circuits, 8, 93. 10.3389/fncir.2014.00093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roegge CS, Timofeeva OA, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, & Levin ED . (2008). Developmental diazinon neurotoxicity in rats: later effects on emotional response. Brain research bulletin, 75(1), 166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler FJ, & Slotkin TA (1981). Development of central control of norepinephrine turnover and release in the rat heart: responses to tyramine, 2-deoxyglucose and hydralazine. Neuroscience, 6, 2081–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple BD, Blomgren K, Gimlin K, Ferriero DM, & Noble-Haeusslein LJ (2013). Brain development in rodents and humans: Identifying benchmarks of maturation and vulnerability to injury across species. Progress in neurobiology, 106, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, & Seidler FJ . (2007). Prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure elicits presynaptic serotonergic and dopaminergic hyperactivity at adolescence: critical periods for regional and sex-selective effects. Reproductive Toxicology, 23(3), 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Wrench N, Ryde IT, Lassiter TL, Levin ED, & Seidler FJ (2009). Neonatal parathion exposure disrupts serotonin and dopamine synaptic function in rat brain regions: modulation by a high-fat diet in adulthood. Neurotoxicol. Teratol, 31, 390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, & Cochran WG . (1967). Statistical methods. Iowa State College Press, Ames, IA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Allen JG, Kelly SM, Konstantinov A, Klosterhaus S, Watkins D, McClean MD and Webster TF (2008). Alternate and new brominated flame retardants detected in US house dust. Environmental Science & Technology, 42(18), 6910–6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su G, Crump D, Letcher RJ, & Kennedy SW (2014). Rapid in vitro metabolism of the flame retardant triphenyl phosphate and effects on cytotoxicity and mRNA expression in chicken embryonic hepatocytes. Environmental science & technology, 42(22), 13511–13519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Xu W, Peng T, Chen H, Ren L, Tan H, Xiao D, Qian H and Fu Z (2016). Developmental exposure of zebrafish larvae to organophosphate flame retardants causes neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 55, 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley SN, Krumm EA, Yasrebi A, Wiersielis KR, O’Leary S, Tillery T, & Roepke TA (2021). Maternal organophosphate flame-retardant exposure alters offspring feeding, locomotor and exploratory behaviors in a sexually-dimorphic manner in mice. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 41(3), 442–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersielis KR, Adams S, Yasrebi A, Conde K, & Roepke TA (2020). Maternal exposure to organophosphate flame retardants alters locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in male and female adult offspring. Hormones and behavior, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win-Shwe TT, Nakajima D, Ahmed S, & Fujimaki H . (2013). Impairment of novel object recognition in adulthood after neonatal exposure to diazinon. Archives of toxicology, 87(4), 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witchey SK, Al Samara L, Horman BM, Stapleton HM, & Patisaul HB (2020). Perinatal exposure to FireMaster® 550 (FM550), brominated or organophosphate flame retardants produces sex and compound specific effects on adult Wistar rat socioemotional behavior. Hormones and behavior, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Chen M, Gao F, Shen H and Hu J (2017). Organophosphorus flame retardants in pregnant women and their transfer to chorionic villi. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(11), 6489–6497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Qiao L, Covaci A, Sun R, Guo H, Zheng J, Luo X, Xie Q and Mai B (2017). Brominated and phosphate flame retardants (FRs) in indoor dust from different microenvironments: implications for human exposure via dust ingestion and dermal contact. Chemosphere, 184(185–191). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.