Abstract

We performed a 318-participant validation study of an individualized risk assessment tool in women identified as having high- or highest-risk of breast cancer in the personalized arm of the Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of risk (WISDOM) trial. Per protocol, these women were educated about their risk and risk reducing options using the Breast Health Decisions (BHD) tool, which uses patient-friendly visuals and 8th grade reading level language to convey risk and prevention options. Prior to exposure to the educational tool, 4.7% of women were already taking endocrine risk reduction, 38.7% were reducing alcohol intake, and 62.6% were exercising. Three months after initial use of BHD, 8.4% of women who considered endocrine risk reduction, 33% of women who considered alcohol reduction, and 46% of women who considered exercise pursued the risk-reducing activities. Unlike lifestyle interventions which are under the control of the patient, additional barriers at the level of the healthcare provider may be impeding the targeted use of endocrine risk reduction medications in women with elevated breast cancer risk.

Keywords: personalized, risk reduction, breast cancer, genetic counseling, education aid, decision making, validation study

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States and the most common cancer in women, with one in eight (12.3%) women developing breast cancer in their lifetime.1 While there are effective strategies for breast cancer prevention with level 1 evidence, there is little evidence that the women who would stand to benefit most are being counseled. Current strategies to identify women at higher risk include genetic testing of women with strong family histories, and recommendations for more intensive surveillance or prophylactic surgery in women found to be mutation carriers. The vast majority of women are not mutation carriers, but many still have risk and are not routinely screened. For women found to be at elevated risk, there are several strategies to reduce risk, including lifestyle interventions (reduction of alcohol intake, increasing exercise, weight loss), the use of endocrine risk reduction medications (selective estrogen receptor modulators and aromatase inhibitors), and avoidance of combined hormone replacement after menopause.1–16 While lifestyle modifications are recommended for all women, randomized controlled clinical trials support the addition of endocrine risk reduction in women at high risk of developing breast cancer.2,17–20 The United States Preventative Task Force guidelines encourage primary care providers to identify high risk women and offer endocrine risk reduction.18 Risk models including Gail used in the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, Tyrer-Cuzick, BOADICEA, and Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) help to stratify breast cancer risk using factors such as age, reproductive history, prior disease, family history, and breast density.21–28 Despite clinical guidelines, availability of risk models, and multiple FDA approved endocrine risk reducing medications, uptake of breast cancer endocrine risk reduction in the United States remains low.20

Only a small portion of women eligible for risk reducing medications receive treatment due to lack of education, low health literacy, concerns about side effects, aversion to medication, cost, and misconceptions about risks and benefits of treatment.5,20,29–31 Educational risk assessment tools allow people to understand their personal risk and weigh the risks and benefits of risk reducing activities.32 In the clinical setting, educational tools can facilitate individualized shared decision-making approaches with providers to improve risk reducing medication uptake in women who would benefit.18

Previously, Keane and Huilgol et al. described the creation and pilot study of the Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of risk (WISDOM) Risk Assessment Tool that educates high- and highest-risk women on their personal breast cancer risk and risk-reducing strategies using personalized genetic testing results, patient-friendly visuals, and 8th grade reading level language.33,34 The purpose of developing the tool was to deploy a risk assessment tool to aid women in considering and pursuing risk-reducing activities, and to learn if high risk women would be particularly compelled to pursue endocrine risk reduction. The broader aim was to assess whether the risk-assessment tool would ease anxiety about breast cancer risk by providing actionable risk reduction steps and to determine if understanding risk would reduce breast cancer anxiety in the high and highest-risk groups. While the pilot study evaluated high- and highest-risk women’s”immediate desires to pursue risk-reducing activities after using the tool, it did not determine whether they truly implemented the strategies.

Here, we describe results of the validation study of the WISDOM Study risk assessment tool in women of high and highest breast cancer risk. The study builds upon our previous pilot study by not only comparing efficacy of a new educational risk assessment tool between high and highest breast cancer risk groups but also temporally evaluating uptake of risk reducing strategies through an immediate feedback and three-month follow up survey. Through this unique lens, we hope to further our understanding of the following questions:

Is the use of the WISDOM Study risk assessment tool in high- and highest-risk women associated with changes in health-related behavior and uptake of endocrine risk reduction?

What are barriers to health-related behavior change and endocrine risk reduction uptake among high- and highest-risk women following use of an educational risk assessment tool?

To what extent does an educational risk-assessment tool affect breast cancer anxiety in high and highest breast cancer risk women?

RESULTS

Risk Assessment Tool Validation Study Participants

The validation study included 318 WISDOM study participants who were classified as elevated risk in the top 2.5% of BCSC score by age group, which corresponds to high-risk women recommended annual screening or highest-risk women recommended every six-month screening (Table 1). Average BCSC scores for high- and highest-risk women in the study are 5.10 and 7.62 respectively. 109 of the 318 participants responded to the three-month follow up survey. Participants were predominantly white, college graduate or higher, between ages 50 – 69, with BMI 18.5 – 24.9 (Table 1).

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants.

Age, BMI, race/ethnicity, education of participants. And further subset for high and highest risk participants.

| High Risk N = 221 (%) | Highest Risk N = 97 (%) | Total Participants N = 318 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40–49 | 64 (29%) | 7 (7.2%) | 71 (22.3%) |

| 50–59 | 72 (32.6%) | 34 (35%) | 106 (33.3%) | |

| 60–69 | 53 (24%) | 49 (50.5%) | 102 (32.1%) | |

| 70–79 | 32 (14.4%) | 7 (7.3%) | 39 (12.3%) | |

| BMI | < 18.5 | 2 (0.9%) | 4 (4.1%) | 6 (1.9%) |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | 120 (54.3%) | 59 (60.8%) | 179 (56.3%) | |

| 25 – 29.9 | 58 (26.2%) | 18 (18.6%) | 76 (23.9%) | |

| >30 | 41 (18.6%) | 16 (16.5%) | 57 (17.9%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 196 (88.7%) | 87 (89.7%) | 283 (89%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (2.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 6 (1.9%) | |

| Black or African American | 5 (2.3%) | 0 | 5 (1.6%) | |

| Asian | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (3.1%) | 5 (1.6%) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (1.3%) | 0 | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Two or more races | 10 (4.5%) | 3 (3.1%) | 13 (4.1%) | |

| Some other race | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (2.1%) | 3 (0.94%) | |

| No response | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (0.31%) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.5%%) | 0 | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Education | High school | 7 (3.2%) | 2 (2.1%) | 9 (2.8%) |

| College or technical school | 41 (18.6%) | 23 (23.7%) | 64 (20.1%) | |

| College graduate or more | 173 (78.2%) | 71 (73.2%) | 244 (76.7%) | |

| No Response | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (0.4%) |

Note: % calculated in risk groups is out of total participants in each risk group

Risk Reduction Activities After Use of Breast Health Risk Assessment Tool

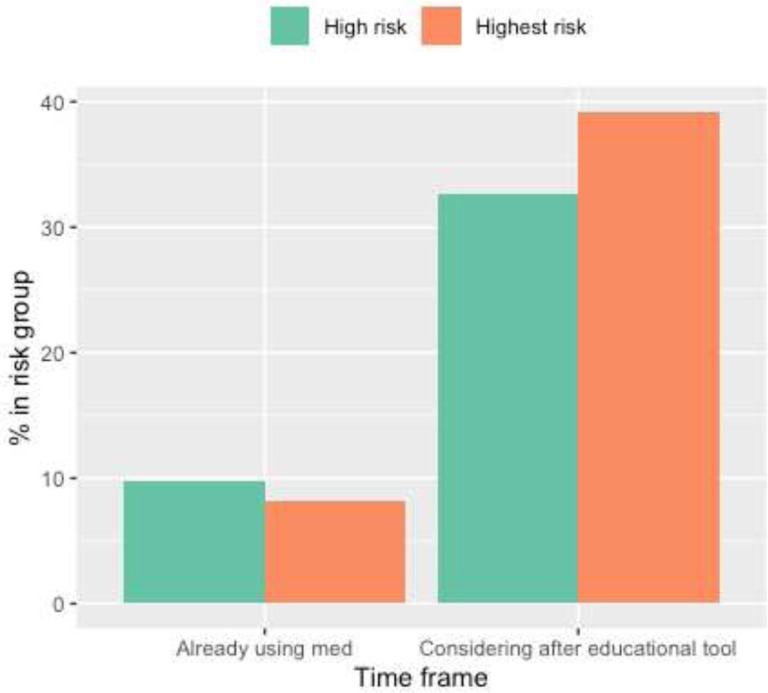

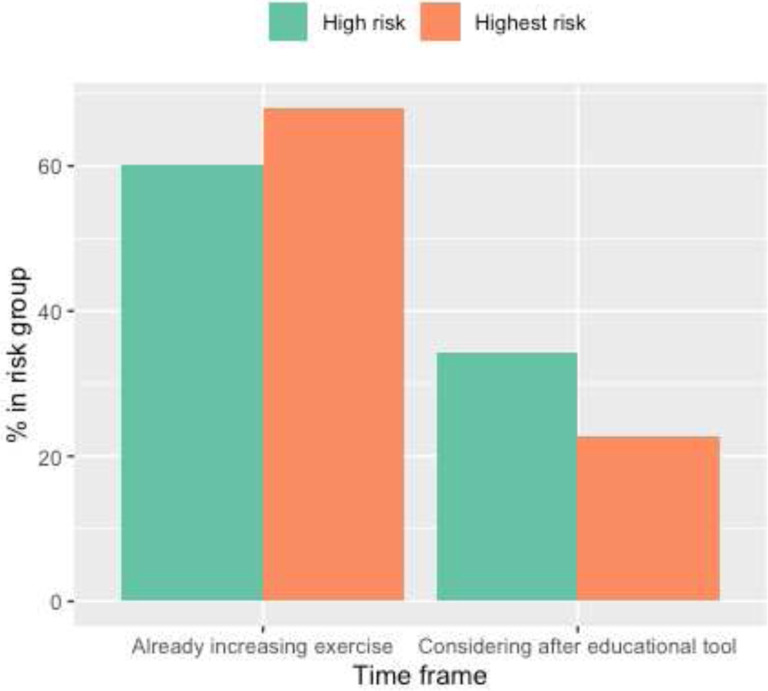

The majority of participants (98.4%) believed that the tool helped them understand their breast cancer risk (Supplementary Table 1). To evaluate risk-reduction activities, we assessed patient reported risk-reducing activity (endocrine risk reduction, alcohol reduction, and exercise) across three time points: before using tool, considerations immediately after using tool, and activities that were implemented 3 months later. Before using the tool, 4.7% of women were taking endocrine risk reduction, 38.7% were reducing alcohol intake, and 62.6% were exercising (Table 2). Immediately after using the tool, 34.6% of women surveyed considered endocrine risk reduction, 14.8% considered decreasing alcohol use and 30.8% considered increasing exercise (Table 2). Next, we examined whether a greater proportion of individuals who considered a risk-reducing activity after using the decision tool pursued it three months later compared to those who did not initially consider it (Supplementary Tables 3a - c). For endocrine risk reduction, 4 out of 48 women (8.4%) who considered it began taking endocrine risk reduction three months later, while 8 out of 61 (13.1%) who did not consider it began taking endocrine risk reduction three months later (Supplementary Table 3a). For alcohol reduction, 31 out of 93 women (33.3%) who considered reducing began to do so three months later, while 11 out of 16 (68.7%) who did not consider it began three months later (Supplementary Table 3b). Lastly, 39 out of 85 women (45.9%) who considered exercising more did so three months later while 14 out of 24 women (58.3%) who did not consider it began three months later (Supplementary Table 3c).

Table 2: Use, Considerations, and Three-Month Follow Up of Breast Cancer Risk-Reducing Strategies.

Risk reducing strategies (endocrine risk reduction, decreasing alcohol, increasing exercise, etc.) that participants are already doing before using BHD, and risk reducing strategies that participants are considering after using BHD, obtained from immediate feedback survey with N = 318 respondents. And risk reducing strategies that they pursued three months later, obtained from three month follow up survey with N=109 respondents.

| High Risk N = 221 (%) |

Highest Risk N = 97 (%) |

Total N = 318 (%) |

Pearson’s Chi Squared Test (high- vs. highest-risk participants) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Already doing risk reducing activities | ||||

| Medication | 7 (3.2%) | 8 (8.2%) | 15 (4.7%) | p = 0.09 |

| Decrease alcohol | 74 (33.5%) | 49 (50.5%)≠ | 123 (38.7%) | p = 0.006 |

| Increase exercise | 133 (60.2%) | 66 (68%) | 199 (62.6%) | p = 0.84 |

| Lose weight | 82 (37.1%) | 45 (46.4%) | 127 (39.9%) | N/A |

| Other | 14 (6.3%) | 12 (12.4%) | 26 (8.2%) | N/A |

| Nothing | 52 (23.5%) | 13 (13.4%) | 65 (20.4%) | N/A |

| Considering risk reducing activities (immediately after using tool) | ||||

| Medication | 72 (32.6%) | 38 (39.2%) | 110 (34.6%) | p = 0.31 |

| Decrease alcohol | 33 (14.9%) | 14 (14.4%) | 47 (14.8%) | p = 1 |

| Increase exercise | 76 (34.4%) | 22 (22.7%) | 98 (30.8%) | p = 0.051 |

| Lose weight | 65 (29.4%) | 17 (17.5%) | 82 (25.8%) | N/A |

| Other | 14 (6.3%) | 3 (3.1%) | 17 (5.3%) | N/A |

| Nothing | 42 (19%) | 22 (22.7%) | 64 (20.1%) | N/A |

| Highest Risk (N = 72) |

Highest Risk (N = 37) |

Total (N = 109) |

||

| Risk reducing activities 3 months after using tool | ||||

| Medication | 7 (9.7%) | 5 (13.5%) | 12 (11%) | p = 0.78 |

| Decrease alcohol | 26 (36.1%) | 16 (43.2%) | 42 (38.5%) | p = 0.6 |

| Increase exercise | 34 (47.2%) | 19 (51.4%) | 53 (48.6%) | p = 0.84 |

| Diet | 47 (65.3%) | 26 (70.3%) | 73 (67%) | N/A |

| Would like support services (3 months after using tool) | 30 (41.7%) | 17 (45.9%) | 47 (43.1%) | N/A |

Notes:

% calculated is out of total who either considered endocrine risk reduction, or the total who did not consider endocrine risk reduction from feedback survey response

statistical significance between high- and highest-risk group

High risk = WISDOM screening assignment recommendation yearly, highest risk = WISDOM screening assignment every 6 months (alternating mammography and MRI). Only high- and highest-risk participants receive a breast health specialist consult with the BHD tool. The low-risk participants however have access to the tool to look through on their own.

Three months after women first used the Breast Health Decisions tool, we asked them whether they discussed their risk with their provider and what risk-reducing activities their provider recommended. A total of 80 (73.3%) women out of the 109 who submitted a three-month follow up survey discussed their breast cancer risk with their provider (Table 3). Healthcare providers recommended endocrine risk reduction to 17% of high- and highest-risk women, alcohol reduction to 14%, and increased exercise to 20% (Table 3). These recommendation percentages were not significantly different between high- and highest-risk women (Table 3).

Table 3: Healthcare Risk-Reducing Recommendation for High- and High-Risk Women.

Table including reasons why participant did not discuss risk with provider, and why they did not pursue endocrine risk reduction, alcohol, or exercise.

| High Risk N = 72 (%) |

Highest Risk N = 37 (%) |

Total N = 109 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Discussed risk with provider | 50 (69.4%) | 30 (81.1%) | 80 (73.3%) |

| Healthcare provider recommended following to reduce risk | |||

| Medication | 11 (15.3%) | 8 (21.6%) | 19 (17.4%) |

| Decrease alcohol | 9 (12.5%) | 6 (16.2%) | 15 (13.8%) |

| Increase exercise | 11 (15.3%) | 11 (29.7%) | 22 (20.2%) |

| Losing weight | 11 (15.3%) | 4 (10.8%) | 15 (13.8%) |

| Other | 8 (11.1%) | 4 (10.8%) | 12 (11%) |

| Nothing at this time | 18 (25%) | 8 (21.6%) | 26 (23.9%) |

Note: Pearson’s Chi-squared test with Yates ‘continuity correction was performed. No statistical significance noted between high- and highest-risk groups

Barriers to discussing risk with provider and using risk-reducing strategies

The most common reason for not discussing one’s risk with a provider was the “other” category, with most participants stating that they have not had their appointment or risk reduction was not brought up during their appointment (Supplementary Table 4). The most commonly selected barriers to endocrine risk reduction were “other” and “fear of side effects” (Supplementary Table 4). Within the “other” category, most women stated that the provider did not recommend the medication. Furthermore, a majority of women who were not reducing alcohol intake or increasing exercise were not doing so because they were already performing the risk-reducing activities (Supplementary Table 4).

Emotional Well Being after use of Risk Assessment Tool

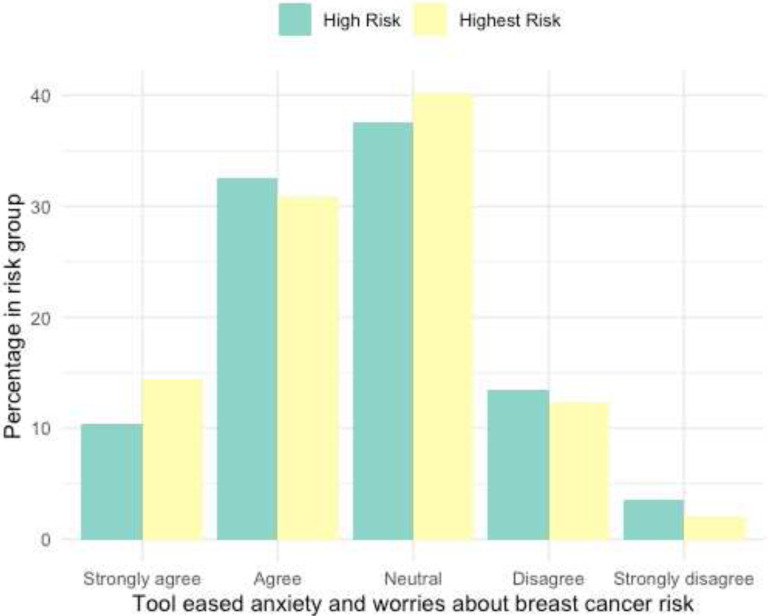

The breast health risk assessment tool eased anxiety about breast cancer risk in 43.7% of participants. A similar proportion of women (38.4%) felt neutral about the tool’s impact on their anxiety. Women who thought the tool did not ease their anxiety made up 16.3% of the surveyed participants (Supplementary Table 1). After stratifying for breast cancer risk, no difference between high and highest-risk women were found (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Risk-Assessment Tool and Anxiety about Breast Cancer Risk (immediately after use).

Bar graph of anxiety and worry about breast cancer risk after use of tool (from feedback survey). Responses obtained through Likert Scale in immediate feedback survey and subset into high- and highest-risk groups.

Note: N/A

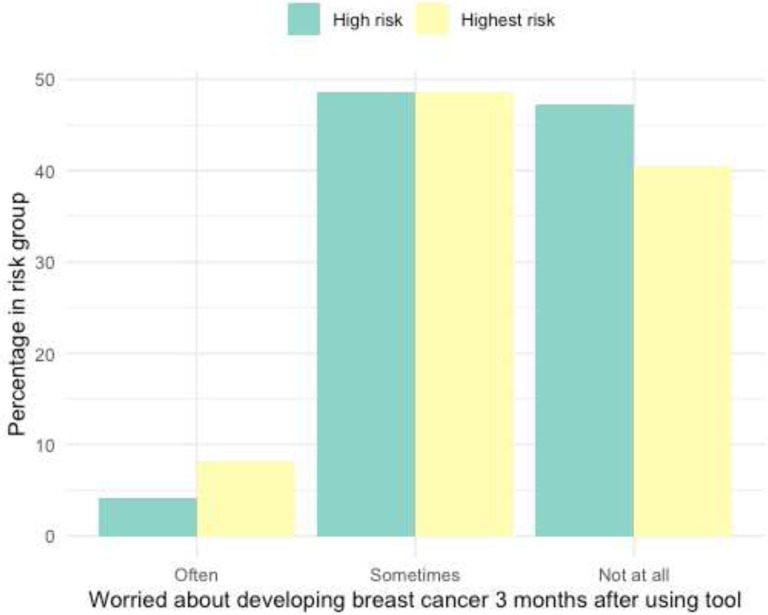

When asked about the frequency women worried about their breast cancer risk three months after first using the decision tool, 5.5% often worried, 48.6% of women sometimes worried, and 45% did not worry at all (Supplementary Table 2). After stratification for breast cancer risk level, no difference between high- and highest-risk women were found (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Worry about Developing Breast Cancer (3 month follow up).

Bar graph of frequency of worry about breast cancer risk after use of tool. Responses obtained through Likert Scale in 3-month follow up survey and subset into high- and highest-risk groups.

Note: N/A

DISCUSSION

Similar risk reduction strategies across risk groups and persistent downstream barriers to endocrine risk reduction

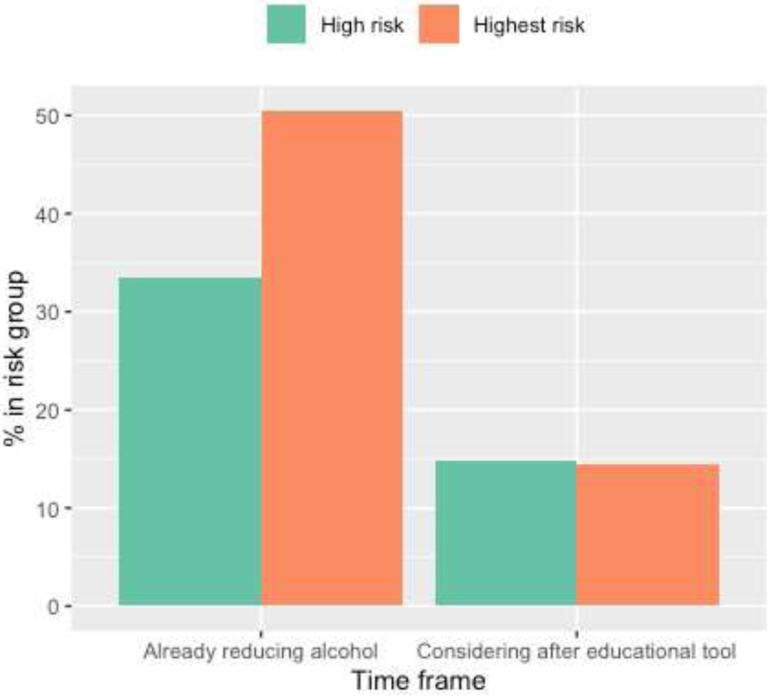

While our initial results are promising, our data also suggests that factors other than initial risk assessment education continue to influence final risk-reduction decisions. To illustrate, a large proportion of all participants (30–40%) considered endocrine risk reduction after using the tool, however the proportion of women taking endocrine risk reduction three months later remains significantly less than those who considered the medication (Fig. 1–3, Table 2). In fact, only 8.4% of women who considered endocrine risk reduction pursued it three months later compared to 30–50% of individuals who considered lifestyle modification (Supplementary Tables 3a-c). Furthermore, the use of endocrine risk reduction was not statistically different between high- and highest-risk women (Fig. 1–3).

Figure 1: Endocrine Risk Reduction Use and Considerations.

Bar graph of endocrine risk reduction use and considerations of reducing alcohol in high and highest breast cancer risk participants. Data collected from immediate feedback survey.

Note: N/A

Figure 3: Exercise Use and Considerations.

Bar graph of exercise use and considerations of pursuing exercise in high and highest breast cancer risk participants. Data collected from immediate feedback survey.

Note: N/A

Lifestyle interventions are under control of the patient while endocrine risk reducing strategies require the support and intervention of a primary care physician or breast cancer prevention specialist. The majority of women who did not pursue endocrine risk reducing medication reported that they either did not have a follow up visit with their primary care physician, or the topic was not brought up. These results suggest that women continue to face barriers to pursue endocrine risk reduction despite becoming more educated and having a desire to take the medication after using the risk assessment tool. There was no active outreach to the participants’” physicians regarding the results of the risk assessment and BHD tool, thus it is also unclear how many of the participants were considered to have elevated risk by their primary care physician. To that end, highest risk women do not have higher uptake of endocrine risk reduction than high risk women after using the educational risk assessment tool.

We did not capture all of the barriers to medication use after the session using the risk assessment tool. Prior papers have suggested that there are barriers to endocrine risk reduction uptake at the provider level in the clinic.29,30,35 Past literature indicates that when assessing risk, most providers never calculate Gail scores (76%).35 While many providers discuss increased risk to high risk women (58%) and tailor screening based on risk (53%), fewer providers usually or always discuss endocrine risk reduction (13%).35 Challenges faced by providers include lack of confidence in risk assessment and knowledge, identifying suitable candidates for preventative strategies, insufficient knowledge of risk-reducing medications, more immediate issues, and lack of time during clinic visits.29,30,35 Despite our efforts in providing a printout summarizing their risk for women to bring to their appointments, this information does not appear to be routinely shared with the primary care physicians. Even when identified as high risk by our study, women are still not getting counseling at the level of their primary care physician, which further confirm the existing literature that indicates that providers are not consistently assessing risk, discussing it, and recommending endocrine risk reduction to high- and highest-risk women who could benefit. Therefore, despite clinical guidelines, providers may not be targeting high-risk women interested in endocrine risk reduction for discussions. Furthermore, when asked about barriers to taking medication, many women noted that their provider did not recommend doing so and that they listen to what their provider recommends (Supplementary Table 4). Since primary care providers are often women’s most trusted source of health information, application of breast cancer risk assessment tools in the clinical setting will require education of and collaboration with the healthcare providers directly involved in patient care.31,36,37 This proposal would emulate the adoption of heart disease risk assessment by primary care physicians, who then implemented interventions to reduce risk for heart attack and stroke, resulting in reducing the risk of cardiac related mortality by 50% over the past several decades.38,39 Alternatively, providing women with virtual prevention clinics could improve medication uptake.

Emotional Well Being after use of Tool Depends on Risk Group

No studies to date have assessed educational tools’ impact on breast cancer anxiety and worry, which is prevalent especially in women with a family history of breast cancer, baseline anxiety, negative illness perceptions, and genetic testing, and impacts decision-making.40–45 Providing women with breast cancer risk estimates has minimal negative effects on anxiety but it is unclear if actionable risk reduction strategies from educational tools like the risk assessment tool can have a positive effect.43,46,47 In this preliminary investigation of anxiety and worry about breast cancer risk after use of an educational tool, a majority of women report that the tool alleviated or did not affect their emotional state, with no difference noted between high- and highest-risk women (Fig. 4–5, Supplementary Table 2). These findings suggest that greater knowledge regarding one’s risk is not associated with negative emotions and may even alleviate anxiety. It is also possible that providing next steps in risk reduction, as done in the educational tool, empowers women and positively contributes to their emotional well-being.

Opportunities

Side effects of medications were listed as one of the important reasons that women chose not to take medication to reduce their breast cancer risk. Fortunately, there are now several studies showing that substantially lower doses of tamoxifen are as effective with few side effects.48 In addition, new evidence suggests a lower dose of an AI is likely to be just as effective in lowering serum estradiol.49

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the COVID-19 pandemic began during our data collection process, so results may be confounded by the public health crisis. In particular, the lockdown and closure of gyms and recreational centers during the COVID crisis may have contributed to the difficulties in scheduling healthcare appointments. Second, due to the nature of the study, we cannot draw causal conclusions. Third, our results are limited by the smaller sample size in our follow up survey results, and the response rate was 35% thus raising the possibility of response or attrition bias. Lastly, our study used a pre-post design and did not include a control group. Thus, subsequent attitudes and health behaviors following use of the BHD tool may have been affected by other intervening temporal factors beside the tool itself.

We also note that several factors limit the generalizability of our study. The WISDOM study participants who used the risk-assessment tool may share characteristics not reflective of the general population. Our participants were predominantly white and highly educated with no African Americans in the highest-risk group. Furthermore, we did not include participants who were high risk by virtue of pathogenic genetic variants.

Future improvements in our approach

There is accumulating evidence that the standard breast cancer risk tools, as well as polygenic risk (PRS), identify women with slower growing hormone positive tumors. This means that our current tools are better at identifying the women most likely to benefit from taking medications to lower their risk. We have increased the diversity of the population of the women in WISDOM so future results should reflect this change. We are working on ways to assess which women are benefiting from endocrine risk reducing therapy.50 We have modified the tool to educate women about small doses of tamoxifen and exemestane previously described. We are working more directly with primary care groups to determine how to best share risk assessment information about their patients. We are also working to determine if a virtual prevention program can be set up to support women in the WISDOM trial, as well as primary care physicians. Studies are also underway testing new medications to reduce risk in women at risk for developing hormone positive breast cancer. Finally, we can explore partnerships with devices that measure physical activity and diet to assist women in quantifying their lifestyle changes.

METHODS AND DATA AVAILABILITY

Modifications of the Risk Assessment Tool

Previously, our team published results of the risk-assessment tool’s pilot study with 17 participants.33 We modified the risk-assessment tool based on participants”feedback and updated the references before implementing it to a broader WISDOM study population.

Study sample

The study sample consisted of 318 WISDOM Study participants in the personalized arm with elevated breast cancer risk in the top 2.5% of BCSC score by age without breast cancer mutation genes (BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53, PTEN, STIK11, CDH1, ATM, PALB2, CHECK2). These high- and highest-risk women are recommended annual mammogram and annual mammogram plus annual MRI screening respectively. Women in the high-risk category are individuals with a 5-year risk greater or equal to 6% in women 65 and older or have a biopsy with atypia and 1st degree family history without chemoprevention. Women in the highest-risk category are individuals with 5-year risk greater or equal to 6% in women 40–64 years old or have a history of chest wall radiation before age 35. Participants eligible for the WISDOM study identify as female, are between ages 40 – 74 years, live in the United States, and have not had prior breast cancer diagnoses. Out of the 318 participants, 109 responded to the follow up survey.

Salesforce platform

Salesforce is an online platform where study coordinators of the WISDOM study can communicate with and perform coordinator tasks for WISDOM participants. The breast health risk assessment tool was provided through the participants’ Salesforce platforms and was accessible after they log into their WISDOM study portal on their own electronic device. The Salesforce platform allowed study coordinators to visualize whether the risk-assessment tool was ever used through a checkbox function.

Procedure

High- and highest-risk participants were provided the opportunity to go through the risk-assessment tool with their breast health specialist through a virtual consultation. Previously in the WISDOM study, breast health specialists contacted high- and highest-risk participants to talk about their risk and answer questions. The risk-assessment tool provided a visual aid for the specialist during the discussion. High- and highest-risk participant who did not respond or declined the consultation had the option to use the risk-assessment tool independently.

After participants completed the breast health risk assessment tool once, they were provided the immediate feedback survey found in the last page of the tool. Three months after participants completed their immediate feedback survey, the three-month follow up survey populated their WISDOM portal.

Data collection

Data was collected from February 2019 to April 2022. A total of 333 participants responded to the feedback survey and 109 participants responded to the three-month follow up survey. Two participants had “stop screening” or “start screening at age 50” recommendations and were excluded from the study. Thirteen completed the survey after being designated low risk and were also excluded from the study.

Data analysis

Study coordinator MC downloaded immediate feedback survey, three-month follow-up survey data and participant demographics information from the Salesforce platform. Study coordinator TW compiled the demographics and survey information into tables and figures and performed statistical analyses using R studio (version 1.0.153). Pearson’s Chi-squared test was calculated to evaluate for differences between high- and highest-risk group categories.

Figure 2: Alcohol Reduction Use and Considerations.

Bar graph of alcohol reduction and considerations of reducing alcohol in high and highest breast cancer risk participants. Data collected from immediate feedback survey.

Note: N/A

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the central Athena Program Management office staff, WISDOM Study member program managers, WISDOM Study advocates, data staff, Breast Health Specialists, and Salesforce programmers for assistance in tool improvements and data collection.

Financial Support:

The WISDOM Study is supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI; PCS-1402-10749 to L.J.E) and National Cancer Institute (R01CA237533 to L.J.E.), Safeway Foundation (to L.J.E.), Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to L.J.E.), Mt. Zion Health Fund (to L.J.E.) and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (to L.J.E.).

Y.S. is supported by the National Cancer Institute (K08KCA237829).

The Athena Breast Health Network is supported by the University of California Office of the President (P0043830 to L.J.E.).

Data collection and sharing for WISDOM Study are supported by the NCI-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (HHSN261201100031C).

Footnotes

Code Availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics

The WISDOM Study is approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco (approval #15–18234). The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved protocol. All participants provided electronic informed consent using digital signatures for the WISDOM Study, and the informed consent materials included the option to participate in additional surveys such as the Breast Health Decisions Tool feedback survey.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Supplementary Files

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Advani P, Moreno-Aspitia A. Current strategies for the prevention of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2014;6:59–71. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S39114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pruthi S, Heisey R, Bevers T. Personalized Assessment and Management of Women at Risk for Breast Cancer in North America. Womens Health. 2015;11(2):213–224. doi: 10.2217/WHE.14.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mocellin S, Goodwin A, Pasquali S. Risk-reducing medications for primary breast cancer: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4:CD012191. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012191.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Use of anastrozole for breast cancer prevention (IBIS-II): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2020;395(10218):117–122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32955-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Land SR, Wickerham DL, Costantino JP, et al. Patient-Reported Symptoms and Quality of Life During Treatment With Tamoxifen or Raloxifene for Breast Cancer PreventionThe NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2742–2751. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cawthorn S, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: extended long-term follow-up of the IBIS-I breast cancer prevention trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):67–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71171-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alés-Martínez JE, et al. Exemestane for Breast-Cancer Prevention in Postmenopausal Women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2381–2391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the Prevention of Breast Cancer: Current Status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powles TJ, Ashley S, Tidy A, Smith IE, Dowsett M. Twenty-Year Follow-up of the Royal Marsden Randomized, Double-Blinded Tamoxifen Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(4):283–290. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waters EA, McNeel TS, Stevens WM, Freedman AN. Use of tamoxifen and raloxifene for breast cancer chemoprevention in 2010. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):875–880. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2089-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of Pharmacologic Interventions for Breast Cancer Risk Reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2942–2962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkin DM, Boyd L, Walker LC. 16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(2):S77–S81. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, Vecchia CL, Corrao G. A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(11):1700–1705. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. The Lancet. 2008;371(9612):569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y, Zhang D, Kang S. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(3):869–882. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2396-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, et al. The Decrease in Breast-Cancer Incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(16):1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3230–3235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilman EA, Pruthi S, Hofstatter EW, Mussallem DM. Preventing Breast Cancer Through Identification and Pharmacologic Management of High-Risk Patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(4):1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman RL, Pruthi S. Chemoprevention of Breast Cancer: The Paradox of Evidence versus Advocacy Inaction. Cancers. 2012;4(4):1146–1160. doi: 10.3390/cancers4041146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewster Abenaa. Chemoprevention for Breast Cancer: Overcoming Barriers to Treatment | American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. In: American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. Vol 32. ; 2012:85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings SR, Tice JA, Bauer S, et al. Prevention of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: approaches to estimating and reducing risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(6):384–398. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson HD, Smith MEB, Griffin JC, Fu R. Use of Medications to Reduce Risk for Primary Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):604–614. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting Individualized Probabilities of Developing Breast Cancer for White Females Who Are Being Examined Annually. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockhill B, Spiegelman D, Byrne C, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA. Validation of the Gail et al. Model of Breast Cancer Risk Prediction and Implications for Chemoprevention. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(5):358–366. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee A, Mavaddat N, Wilcox AN, et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet Med. 2019;21(8):1708–1718. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0406-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brentnall AR, Cuzick J, Buist DSM, Bowles EJA. Long-term Accuracy of Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Combining Classic Risk Factors and Breast Density. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):e180174. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyrer J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat Med. 2004;23(7):1111–1130. doi: 10.1002/sim.1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacInnis RJ, Bickerstaffe A, Apicella C, et al. Prospective validation of the breast cancer risk prediction model BOADICEA and a batch-mode version BOADICEACentre. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1296–1301. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yi H, Xiao T, Thomas PS, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Patient-Provider Communication When Discussing Breast Cancer Risk to Aid in the Development of Decision Support Tools. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2015;2015:1352–1360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hum S, Wu M, Pruthi S, Heisey R. Physician and Patient Barriers to Breast Cancer Preventive Therapy. Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2016;8(3):158–164. doi: 10.1007/s12609-016-0216-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heisey R, Pimlott N, Clemons M, Cummings S, Drummond N. Women’s views on chemoprevention of breast cancer: qualitative study. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2006;52:624–625. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keane H, Huilgol YS, Shieh Y, et al. Development and pilot of an online, personalized risk assessment tool for a breast cancer precision medicine trial. Npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00288-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esserman LJ. The WISDOM Study: breaking the deadlock in the breast cancer screening debate. Npj Breast Cancer. 2017;3(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41523-017-0035-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabatino SA, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Burns RB. Breast cancer risk assessment and management in primary care: provider attitudes, practices, and barriers. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(5):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corbelli J, Borrero S, Bonnema R, et al. Use of the Gail Model and Breast Cancer Preventive Therapy Among Three Primary Care Specialties. J Womens Health. 2014;23(9):746–752. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samimi G, Heckman-Stoddard BM, Holmberg C, et al. Assessment of and Interventions for Women at High Risk for Breast or Ovarian Cancer: A Survey of Primary Care Physicians. Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa. 2021;14(2):205–214. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-20-0407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Agostino Ralph; Vasan Ramachandran. General Cardiovascular Risk Profile for Use in Primary Care. Published online February 12, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebell Mark; Grad Roland. Top 20 Research Studies of 2021 for Primary Care Physicians | AAFP. Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2022/0700/top-poems-2021.html [PubMed]

- 40.Gibbons A, Groarke A. Can risk and illness perceptions predict breast cancer worry in healthy women? J Health Psychol. 2016;21(9):2052–2062. doi: 10.1177/1359105315570984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grimm LJ, Shelby RA, Knippa EE, et al. Frequency of Breast Cancer Thoughts and Lifetime Risk Estimates: A Multi-Institutional Survey of Women Undergoing Screening Mammography. J Am Coll Radiol JACR. 2019;16(10):1393–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seven M, Bağcivan G, Akyuz A, Bölükbaş F. Women with Family History of Breast Cancer: How Much Are They Aware of Their Risk? J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2018;33(4):915–921. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1226-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie Z, Wenger N, Stanton AL, et al. Risk estimation, anxiety, and breast cancer worry in women at risk for breast cancer: A single-arm trial of personalized risk communication. Psychooncology. 2019;28(11):2226–2232. doi: 10.1002/pon.5211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartley CA, Phelps EA. Anxiety and Decision-Making. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beckers T, Craske MG. Avoidance and decision making in anxiety: An introduction to the special issue. Behav Res Ther. 2017;96:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.French DP, Southworth J, Howell A, et al. Psychological impact of providing women with personalised 10-year breast cancer risk estimates. Br J Cancer. 2018;118(12):1648–1657. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0069-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Erkelens A, Sie AS, Manders P, et al. Online self-test identifies women at high familial breast cancer risk in population-based breast cancer screening without inducing anxiety or distress. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2017;78:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eriksson M, Eklund M, Borgquist S, et al. Low-Dose Tamoxifen for Mammographic Density Reduction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2021;39(17):1899–1908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Censi A, Serrano D, Gandini S, et al. A randomized presurgical trial of alternative dosing of exemestane in postmenopausal women with early-stage ER-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_suppl):519–519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.51934878805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glencer AC, Miller PN, Greenwood H, et al. Identifying Good Candidates for Active Surveillance of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ: Insights from a Large Neoadjuvant Endocrine Therapy Cohort. Cancer Res Commun. 2022;2(12):1579–1589. doi: 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-22-0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.