Abstract

Background:

Food-specific immunoglobulin G4 (FS-IgG4) is associated with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE); however, it is not clear whether production is limited to the esophagus.

Aims:

To assess FS-IgG4 levels in the upper gastrointestinal tract and plasma and compare these with endoscopic disease severity, tissue eosinophil counts, and patient-reported symptoms.

Methods:

We examined prospectively-banked plasma, throat swabs, and upper gastrointestinal biopsies (esophagus, gastric antrum, and duodenum) from control (n=15), active EoE (n=24) and inactive EoE (n=8) subjects undergoing upper endoscopy. Patient-reported symptoms were assessed using the EoE symptom activity index (EEsAI). Endoscopic findings were evaluated using the EoE endoscopic reference score (EREFS). Peak eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) were assessed from esophageal biopsies. Biopsy homogenates and throat swabs were normalized for protein content and assessed for FS-IgG4 to milk, wheat, and egg.

Results:

Median FS-IgG4 for milk and wheat was significantly increased in the plasma, throat swabs, esophagus, stomach, and duodenum of active EoE subjects compared to controls. No significant differences for milk- or wheat-IgG4 were observed between active and inactive EoE subjects. Among the gastrointestinal sites sampled, FS-IgG4 levels were highest in the esophagus. Esophageal FS-IgG4 for all foods correlated significantly across all sites sampled (r≥0.59, p<0.05). Among subjects with EoE, esophageal FS-IgG4 correlated significantly with peak eos/hpf (milk and wheat) and total EREFS (milk). EEsAI scores and esophageal FS-IgG4 levels did not correlate.

Conclusions:

Milk and wheat FS-IgG4 levels are elevated in plasma and throughout the upper gastrointestinal tract in EoE subjects and correlate with endoscopic findings and esophageal eosinophilia.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, IgG4, biomarker, food allergy

Background:

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an immune-mediated disease of the esophagus characterized by eosinophilic inflammation, dysphagia, tissue remodeling, and esophageal dysfunction 1. EoE is an allergic-type disease mediated by type 2 inflammation, often triggered by ingested food antigens 2. Treatment with elemental diet promotes histologic and endoscopic improvements 3. A major unresolved question is how food antigens drive type 2 inflammation in EoE.

Several studies have disputed the role of IgE in EoE 4-6 and there is little information regarding the antigen specificity of Th2 cells in the esophageal mucosa. We and others have noted elevated food-specific immunoglobulin G4 (FS-IgG4) in the esophagus and plasma/serum of EoE patients 7-11 suggesting that patients with EoE develop humoral type 2 immune responses to foods. FS-IgG4 is associated with prolonged and repeated exposures to food antigens 9,12. FS-IgG4 has been correlated with histological markers of disease in adult and pediatric EoE patients 7,13-15. Total and FS-IgG4 levels decrease in patients responding to diet elimination therapy 7 and corticosteroid treatment 16. Unfortunately, no clear association between EoE food triggers and FS-IgG4 levels has been made 7,8,17. Thus, the role of FS-IgG4 in EoE pathogenesis is unclear.

FS-IgG4 is associated with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE); however, it is not clear whether its production is limited to the esophagus. The primary objective of this study was to assess FS-IgG4 levels in the plasma and upper gastrointestinal tract and compare these with endoscopic disease severity, tissue eosinophil counts, and patient reported symptoms.

Methods:

Study population, specimen collection, and clinical characteristics

We conducted a nested case control study of prospectively collected gastrointestinal biopsies (esophagus, gastric antrum, and duodenum) and questionnaires from subjects undergoing upper endoscopy for symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mayo Clinic (15-008588, 17-007025).

Demographic and atopic disease status were collected from the electronic medical record and patient questionnaires. Endoscopic findings were evaluated using the EoE endoscopic reference score (EREFS) 18. Eight biopsy specimens (4 distal, 4 mid-proximal) procured during endoscopy were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded for histological assessment. Additional biopsies were obtained for research purposes. Peak eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) were assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Diagnosis of active EoE was determined by histological assessment of esophageal biopsies, per consensus guidelines 19. Gastric and duodenal biopsy H&E-stained sections were also assessed for eos/hpf to evaluate for concomitant non-esophageal eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (EGID). Non-EoE controls were subjects with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction who did not meet histologic criteria for EoE. Inactive EoE subjects had <15 peak eos/hpf in esophageal biopsies following treatment with high-dose PPI. At the time of endoscopy, a plasma sample, throat swab, and additional esophageal, gastric, and duodenal biopsies were obtained, flash frozen, and stored for subsequent analyses.

Subjects completed a questionnaire assessing demographics, medical history, and allergic conditions at intake, prior to endoscopic examination. Subjects also the completed EoE symptom activity index (EEsAI) questionnaires 20. Briefly, this patient-reported outcome instrument includes domains assessing symptom severity and behavioral adaptations, which are recalled over a 7-day period. The domain addressing symptoms while eating or drinking includes items on frequency and duration of trouble swallowing, as well as pain when swallowing. The visual dysphagia question (VDQ) component addresses severity of dysphagia and the AMS (avoidance, modification, and slow eating) component assesses behavioral adaptations when consuming food of 8 different consistencies. EoE subjects with a history of prior esophageal dilation were excluded from analysis of EEsAI questionnaires 21.

Patients who were on treatment for EoE with diet elimination, swallowed topical steroids, or biologics were excluded. Some patients were on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) at the time of initial endoscopy as multiple endoscopies were performed prior to the updated consensus guidelines eliminating the requirement for a PPI trial for EoE diagnosis 22 19.

Biospecimen processing and FS-IgG4 measurements

As previously reported 7, frozen tissue biopsy specimens were thawed, manually homogenized using a 2 mL Dounce tissue grinder set (Sigma Aldrich) in PBS and protease inhibitor (Roche). Protein was extracted from throat swab specimens in 500 μl of cetrimonium bromide (CTAB) containing sucrose solution (0.22% CTAB, 0.3M sucrose). The total protein content of the tissue homogenates and throat swab eluates was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA, Pierce) and normalized to 100 μg/mL.

For FS-IgG4 measurements, Immulon HBX microtiter plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with milk, wheat, or egg white extract (Greer; diluted to 20 μg/mL in bicarbonate coating buffer). Standard curve wells were coated with purified mouse anti-human IgG4 (BD, clone G17-4; diluted 1:250). Tissue homogenates and throat swab eluates were diluted 1:2 in 1% BSA-PBS-0.05% Tween 20 and added to sample wells. Plasma samples were not normalized for protein content and all were diluted 1:5,000 in 1% BSA-PBS-0.05% Tween 20. Mouse anti-human IgG4-HRP antibody (Southern Biotech, clone HP6025 diluted 1:1,000) was used as the detection antibody and the wells were developed with TMB substrate solution (KPL). The plates were read on a plate reader and optical density values were compared to a standard curve generated from serial 1:2 dilutions of recombinant human IgG4 (Abcam) from 100 ng/mL to 0.097 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics of controls, active EoE subjects, and inactive EoE subjects were summarized with descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were reported as the subject count and percentage and continuous variables were reported by median and quartiles 1 and 3 (Q1, Q3) or range. Comparisons of demographic and atopic features of all subjects were made using a Chi-squared test (categorical variables) or a Kruskal-Wallis test (continuous variables). The Kruskall-Wallis test was also used to compare FS-IgG4 across the four gastrointestinal sites sampled. Pairwise comparisons of EREFS, EEsAI, and median FS-IgG4 values between control and active EoE subjects were made using a Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations between FS-IgG4 levels, eos/hpf, EREFS for EoE subjects (active and inactive) were calculated using Spearman’s rho. EEsAI scores were assessed among subjects with EoE (active and inactive) using Spearman’s rho. The analysis of EREFS and EEsAI scores did not include control subjects as these instruments have only been validated in EoE subjects. Statistical comparisons and plots were made with GraphPad Prism (version 9, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. There was no adjustment for multiple testing.

Results:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are detailed in Table 1. Matched gastrointestinal biopsies (esophagus, gastric antrum, duodenum), plasma, and throat swab samples were taken from 47 subjects undergoing upper endoscopy. We evaluated 15 control, 24 active EoE, and 8 inactive EoE subjects. All control subjects had 0 peak eos/hpf with exception of one individual. This subject had Los Angeles grade D esophagitis, 6 peak eos/hpf in the distal esophagus, and was diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). One subject with active EoE had tissue eosinophilia consistent with eosinophilic gastritis (EoG). The samples and data collected for this study are summarized in Supplemental Figure 1. In comparison to controls, subjects with active EoE were more likely to be male and have a history of atopic dermatitis. Control subjects were more likely to have GERD or a functional gastrointestinal disorder. Total EREFS was elevated among active EoE subjects.

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics

| Controls (n=15) |

Active EoE (n=24) |

Inactive EoE (n=8) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n, %) | 11 (73.3) | 5 (20.8) | 4 (50) | 0.005 |

| Males (n, %) | 4 (26.7) | 19 (79.2) | 4 (50) | 0.005 |

| Age (median yrs, (Q1,Q3)) | 64 (35, 68) | 45 (35, 57) | 43 (35, 54) | 0.08 |

| Atopy (any) (n, %) | 9 (60) | 21 (87.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0.10 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 7 (46.7) | 17 (70.8) | 7 (87.5) | 0.11 |

| Asthma | 6 (40) | 11 (45.8) | 3 (37.5) | 0.89 |

| Food allergy | 0 | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 0.22 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 0 | 6 (25) | 0 | 0.04 |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | ||||

| EoE | 0 | 24 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| GERD | 8 (53.3) | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0.0002 |

| IBS | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.34 |

| Esophageal dysmotility | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.34 |

| Functional GI disorder | 3 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Normal | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.31 |

| Schatzki’s ring | 1 (6.7) | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 0.54 |

| History of dilation† | 4 (26.7) | 14 (58.3) | 2 (25) | 0.08 |

| Peak eos/hpf (median, (Q1, Q3)) | 0 (0, 0) | 45 (30, 76.5) | 3 (0, 8.75) | <0.0001 |

| EREFS (median, range) | ||||

| Edema | - | 1 (0-1) | 0.5 (0-1) | 0.40 |

| Rings | - | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) | 0.17 |

| Exudates | - | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | >0.99 |

| Furrows | - | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 0.09 |

| Strictures | - | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 0.42 |

| EREFS (total) | - | 4 (0-6) | 2.5 (2-3) | 0.02 |

| Other endoscopic findings | ||||

| Reflux esophagitis | 5 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| Hiatal hernia | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | 0.21 |

| Salmon patches | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 0.70 |

| EEsAI scores (median, range) | ||||

| Composite dysphagia | - | 15 (0-31) | 0 (0-15) | 0.38 |

| VDQ | - | 15.5 (0-21) | 6 (0-12) | 0.12 |

| AMS score | - | 0 (0-25) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

| EEsAI (total) | - | 27 (12-52) | 6 (0-27) | 0.05 |

Comparisons across three groups were performed using a chi-squared test (categorical variables) or Kruskal-Wallis test (continuous variables). Comparisons of EREFS and EEsAI scores between active and inactive EoE subjects were performed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Indications for esophageal dilation in control subjects were Schatzki’s ring (n =2) or stricture (n = 1 peptic stricture, n = 1 stricture with unknown location).

Abbreviations: AMS – avoidance, modification, and slow eating; EEsAI – eosinophilic esophagitis symptom activity index; EoE – eosinophilic esophagitis; eos/hpf – eosinophils per high-power field; EREFS – endoscopic reference score; GERD – gastroesophageal reflux disease; GI – gastrointestinal; IBS – irritable bowel syndrome; Q1 – quartile 1; Q3 – quartile 3; VDQ – visual dysphagia question; yrs - years.

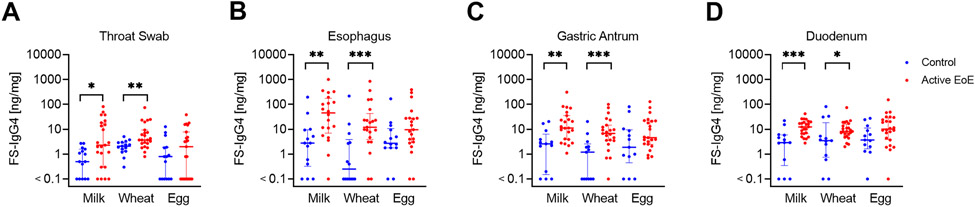

We assessed FS-IgG4 for the most common EoE trigger foods: milk, wheat, and egg 23. Milk-IgG4 was elevated in active EoE patients vs. controls throughout the upper gastrointestinal tract [median (95% CI of difference): throat swab 2.3 ng/mg vs. 0.5 ng/mg (0.2-13.6), p=0.01; esophagus 46.65 ng/mg vs. 2.8 ng/mg (4.2-110.8), p=0.002; gastric antrum 11.2 ng/mg vs. 2.6 ng/mg (2.4-21.4), p=0.001; duodenum 12.45 ng/mg vs. 2.9 ng/mg (3.8-14.3), p=0.0004] (Figure 1). Wheat-specific IgG4 was also elevated in active EoE patients along the gastrointestinal tract [median throat swab 3.7 ng/mg vs. 2.1 ng/mg (0.7-5.2), p=0.003; esophagus 12.1 ng/mg vs. 0.25 ng/mg (3-22.5), p=0.001; gastric antrum 6.8 ng/mg vs. 1.2 ng/mg (1.8-9.6), p=0.0008; duodenum 8.2 ng/mg vs. 3.5 ng/mg (0.9-8), p=0.03]. Similar trends were observed for egg-IgG4, but these did not reach statistical significance. Milk- and egg-IgG4 levels were highest in the esophagus among the gastrointestinal sites sampled in subjects with EoE (active and inactive) and controls and a similar trend was observed for wheat-IgG4 (milk-IgG4: H=19.06, p=0.0003, wheat-IgG4: H=7.035, p=0.07, egg-IgG4: H=105.1, p<0.0001). H. Interestingly, undetectable levels of FS-IgG4 were only noted in 1 subject in the stomach and duodenum among active EoE subjects.

Figure 1: Food-specific IgG4 (FS-IgG4) to milk and wheat are increased throughout the upper gastrointestinal tract in subjects with active EoE.

FS-IgG4 levels to milk, wheat, and egg from throat swabs (A) and biopsies from the esophagus (B), gastric antrum (C), and duodenum (D) in control vs. active EoE subjects. Horizontal lines indicate median and interquartile range. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

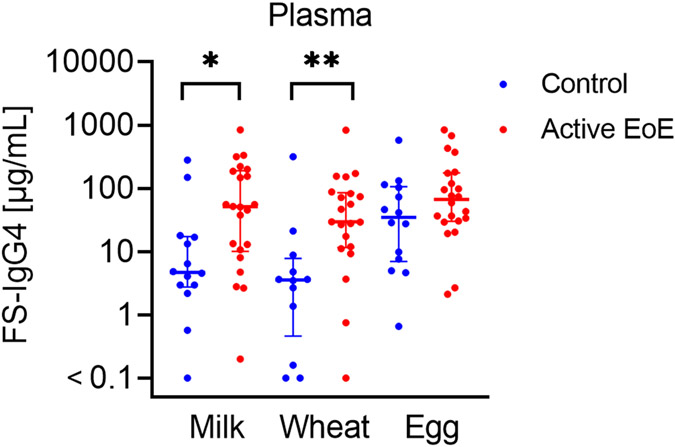

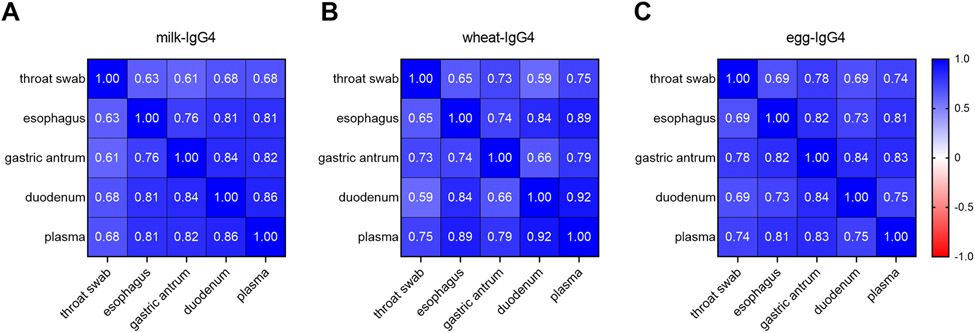

Milk- and wheat-IgG4 were significantly increased in the plasma of active EoE subjects compared to controls [median (95% CI of difference): milk-IgG4 51.4 μg/mL vs. 4.7 μg/mL (3.2-141.5), p=0.01; wheat-IgG4 29.5 μg/mL vs. 3.6 μg/mL (7.96-70.38), p=0.002] (Figure 2). No significant differences were observed between active and inactive EoE subjects, however the sample size of inactive EoE subjects was small. IgG4 levels for all foods correlated significantly across the gastrointestinal sites assessed, as well as with the plasma FS-IgG4 levels of EoE subjects (Figure 3).

Figure 2: FS-IgG4 levels to milk and wheat are increased in the plasma of EoE subjects.

FS-IgG4 levels to milk, wheat, and egg are compared between controls and active EoE subjects. Horizontal lines indicate median and interquartile range. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

Figure 3: FS-IgG4 levels strongly correlate across sites in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Correlation matrices for milk-IgG4 (A), wheat-IgG4 (B), and egg-IgG4 (C) show the relationship between FS-IgG4 levels among various compartments of the upper gastrointestinal tract. All correlations shown are significant (p<0.0001).

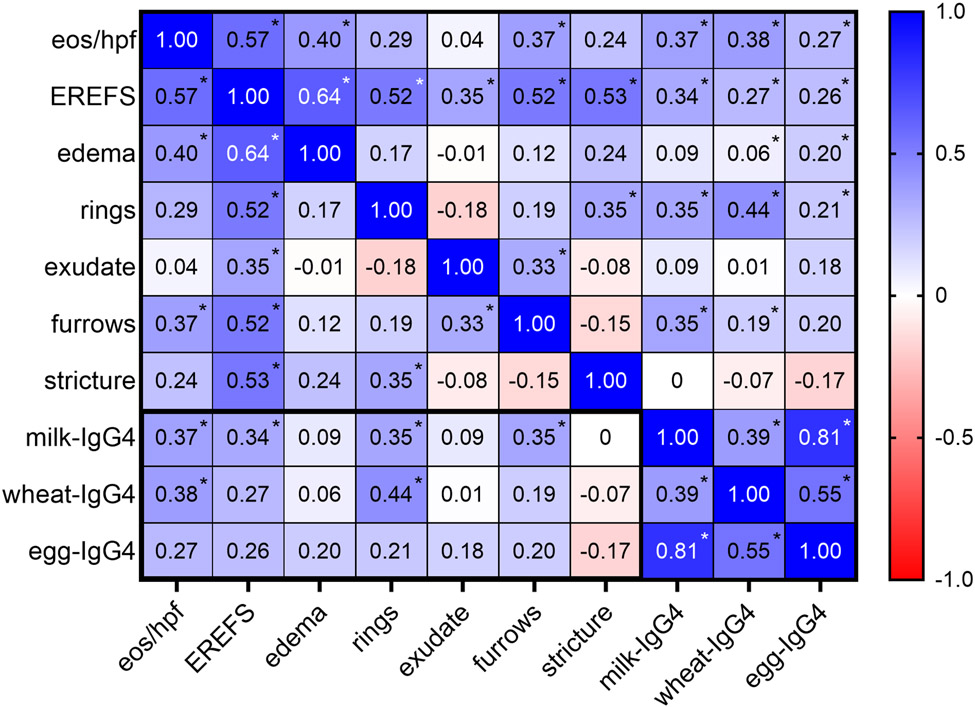

To assess the relationship between esophageal FS-IgG4 levels and markers of disease activity and endoscopic severity, we compared esophageal FS-IgG4 with peak eos/hpf and EREFS total and component scores. Milk-IgG4 correlated significantly with peak eos/hpf (r=0.37, p=0.03) and total EREFS (r=0.34, p=0.048) (Figure 4). Among EREFS component scores, FS-IgG4 correlated most strongly with scores for rings (milk-IgG4: r=0.35, p=0.04 and wheat-IgG4: r=0.44, p=0.009) and furrows (milk-IgG4: r=0.35, p=0.04).

Figure 4: FS-IgG4 correlates with tissue eosinophilia and endoscopic findings.

Correlation matrix showing the relationship between FS-IgG4, eos/hpf, and EREFS (total and component scores) in the esophagus of EoE and control subjects. * p<0.05.

Finally, we evaluated the relationship between FS-IgG4 and EEsAI scores to determine whether FS-IgG4 was associated with clinical symptoms. FS-IgG4 levels did not correlate with patient-reported symptoms in EoE subjects based on total EEsAI or EEsAI component scores; however, the number of subjects who completed EEsAI questionnaires without a history of esophageal dilation was limited (n=12) and only a trend for higher median total EEsAI scores was observed in active vs. inactive EoE subjects (Supplemental Figure 2).

Discussion:

In this study, we found that FS-IgG4 levels are elevated in the plasma and throughout the upper gastrointestinal tract in subjects with active EoE. Consistent with previous studies examining mucosal secretions and biopsies 7,13-15, esophageal FS-IgG4 correlated with markers of disease severity including endoscopic findings and esophageal eosinophilia. FS-IgG4 levels were highest in the esophagus among the gastrointestinal samples; however, the detection of extra-esophageal FS-IgG4 suggests a coordinated antigen-specific immune response in additional areas of the gastrointestinal tract. Although only approximately 3% of individuals with EoE have co-morbid EoG or eosinophilic duodenitis (EoD) 24, increased IgG4-positive plasma cells and extracellular IgG4 deposition has been noted in patients with EoG and EoD25,26. To our knowledge, we are the first to show that FS-IgG4 levels are elevated in the stomach and duodenum of EoE subjects.

We noted increased FS-IgG4 in throat swabs from subjects with EoE that correlated with esophageal FS-IgG4. This finding is intriguing given that many patients with EoE also have comorbid oral allergy syndrome 27,28. Notably, eosinophil granule proteins have not been detected in the oropharynx of individuals with EoE, despite elevated levels in the esophagus 29,30. In contrast, our results suggest that throat swabs and saliva samples are reflective of local gastrointestinal FS-IgG4 levels and may provide an easier means to assess esophageal FS-IgG4. We previously noted that FS-IgG4 decreases in response to diet elimination in esophageal homogenates, but not necessarily plasma 7, highlighting the importance of sampling at or near the site of inflammation. Similar to our findings, Pyne et al. 13 noted elevated FS-IgG4 in the saliva of 2/4 subjects with EoE. Further, Smeekens et al. 31 recently noted increased peanut-IgG4 in the saliva of subjects undergoing peanut oral immunotherapy (OIT). This observation is important in the context of a potential causal association between OIT and EoE in a subset of patients 32.

One of the main challenges in assessing immune factors associated with EoE is discerning whether they are pathogenic, compensatory, or produced as an epiphenomenon. Plasma FS-IgG4 has been shown to reflect dietary consumption in EoE 9. When compared to aeroallergen-specific IgG4, FS-IgG4 levels in the plasma are an order of magnitude higher in EoE suggesting antigen load influences the quantity of production 9. We find it interesting that despite less than 30% of EoE patients being triggered by wheat 23, most EoE subjects have elevated esophageal FS-IgG4 to wheat if it remains in the diet. Indeed, production of FS-IgG4 in the esophagus does not appear to be dependent on trigger status, given the correlation of FS-IgG4 we observed across antigens (i.e. milk, egg, and wheat). Moreover, in the small number of EoE subjects with no history of esophageal dilation who completed the EEsAI questionnaire, we did not see associations between symptoms of EoE and FS-IgG4. These findings coupled with the observation that FS-IgG4 is detectable in areas of the gastrointestinal tract where there is no observable pathology suggest that FS-IgG4 does not drive disease pathogenesis.

Key questions remaining include the source and function of FS-IgG4 in EoE. Regarding its source, FS-IgG4 is produced both locally and systemically. IgG4-positive plasma cells have been identified in the lamina propria of subjects with EoE, EoG and EoD signaling local production 15,16,25,26. We speculate paracellular leakage through the stratified squamous epithelium from both the lamina propria and circulation may contribute to increased FS-IgG4 levels in the gastrointestinal tract. Further, the dilation of intercellular spaces and angiogenesis associated with EoE may enhance paracellular leakage. Swallowing/luminal transport of FS-IgG4 from proximal to more distal areas of the gastrointestinal tract is also a consideration.

In terms of function, Zukerberg et al.16 noticed superficial layering of extracellular IgG4 deposits in EoE, suggesting IgG4 may play a role at the apical surface of the esophageal epithelium. Mucosal barrier impairment associated with EoE leads to persistence of food proteins in the esophagus and formation of IgG4:antigen immune complexes 33. Experiments in mouse models of food allergy suggest that FcRn-dependent transfer of maternal IgG:ovalbumin immune complexes via breast milk promotes neonatal tolerance through antigen presentation by CD11c+ dendritic cells and induction of allergen-specific regulatory T cells in offspring 34. We hypothesize that FS-IgG4 is produced in response to epithelial barrier disruption as a protective response to neutralize antigen and possibly influence antigen presentation to promote tolerance. In EGIDs, this response is inadequate.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, we did not match EoE cases and controls based on sex. Though we do not anticipate sex-related differences in FS-IgG4 production, we cannot exclude this possibility. Second, we did not define EoE food triggers for our subjects nor did we assess frequency of food consumption. Third, our method for detection of FS-IgG4 only allows for relative comparisons across antigens as the standard curve is generated from a generic IgG4 molecule. In addition, the sample size of EoE subjects without a history of esophageal dilation who completed the EEsAI questionnaire is small. Furthermore, these subjects reported relatively mild symptoms, limiting our ability to make definitive conclusions about the relationship between symptoms and FS-IgG4. These weaknesses are balanced by several strengths including the prospective collection of questionnaires and specimens in EoE subjects and controls who were not being treated with diet elimination or topical steroids, comprehensive assessment of FS-IgG4 from multiple gastrointestinal compartments, and correlation with multiple food antigens and disease outcome measures.

In conclusion, we show that FS-IgG4 levels to milk and wheat are increased in the plasma and throughout the gastrointestinal tract of subjects with EoE. FS-IgG4 levels correlate with tissue eosinophilia and endoscopic findings, but not necessarily clinical symptoms. Additional studies are needed to define the role of IgG4 in EGIDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the patients at Mayo Clinic Arizona who participated in this study. We appreciate the assistance of the Sara Farmer in the Mayo Clinic Survey Research Center for her assistance with the electronic questionnaires and database. We would also like to thank the members of the esophageal disease group (Marcelo Vela, MD, Francisco Ramirez, MD, and David Fleischer, MD), the allied health staff in the endoscopy suite, and the pathology research core and biorepository staff, who assisted with specimen collection, storage and requisition. We acknowledge the support of clinical research coordinators Shannan Avelar and Rachel Kendrick. We thank Ekaterina Safroneeva, PhD for allowing us to use the EEsAI PRO and Evan Dellon, MD, MPH for his aid in interpretating the EEsAI scores.

Financial support:

This work was supported by the Arizona Biomedical Research Consortium (ADHS18-198880), Donald R. Levin Family Foundation, Mayo Clinic Foundation, and Phoenix Children's Hospital Foundation. M.Y.M. is a member of the Immunology Graduate Program and is supported by the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. B.L.W. also reports funding from NIH (L30 AI147030) and the Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers U54AI117804 (CEGIR), which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Disease Research (ORDR). CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups including American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (CURED), and Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC). As a member of the RDCRN, CEGIR is also supported by its Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC) (U2CTR002818).

Abbreviations used:

- AMS

avoidance, modification, and slow eating

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid assay

- CI

confidence interval

- CTAB

cetrimonium bromide

- EEsAI

eosinophilic esophagitis symptom activity index

- EGID

eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease

- EoD

eosinophilic duodenitis

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- EoG

eosinophilic gastritis

- eos/hpf

eosinophils per high-power field

- EREFS

endoscopic reference score

- FS-IgG4

food-specific immunoglobulin G4

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- GI

gastrointestinal

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- Q1

quartile 1

- Q3

quartile 3

- VDQ

visual dysphagia question

- yrs

years

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: None to report.

References:

- 1.Muir A, Falk GW. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Review. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1310–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Shea KM, Aceves SS, Dellon ES, et al. Pathophysiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Tenias JM, Lucendo AJ. Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1639–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loizou D, Enav B, Komlodi-Pasztor E, et al. A pilot study of omalizumab in eosinophilic esophagitis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0113483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon D, Cianferoni A, Spergel JM, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis is characterized by a non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity. Allergy. 2016;71(5):611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright BL, Kulis M, Guo R, et al. Food-specific IgG(4) is associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):1190–1192 e1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellon ES, Guo R, McGee SJ, et al. A Novel Allergen-Specific Immune Signature-Directed Approach to Dietary Elimination in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10(12):e00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGowan EC, Medernach J, Keshavarz B, et al. Food antigen consumption and disease activity affect food-specific IgG4 levels in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Clin Exp Allergy. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuyler AJ, Wilson JM, Tripathi A, et al. Specific IgG(4) antibodies to cow's milk proteins in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):139–148 e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dilollo J, Rodriguez-Lopez EM, Wilkey L, Martin EK, Spergel JM, Hill DA. Peripheral markers of allergen-specific immune activation predict clinical allergy in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2021;76(11):3470–3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tordesillas L, Berin MC. Mechanisms of Oral Tolerance. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;55(2):107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyne AL, Hazel MW, Uchida AM, et al. Oesophageal secretions reveal local food-specific antibody responses in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(9):1328–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg CE, Mingler MK, Caldwell JM, et al. Esophageal IgG4 levels correlate with histopathologic and transcriptomic features in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2018;73(9):1892–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pope AE, Stanzione N, Naini BV, et al. Esophageal IgG4: Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Correlations in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68(5):689–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zukerberg L, Mahadevan K, Selig M, Deshpande V. Oesophageal intrasquamous IgG4 deposits: an adjunctive marker to distinguish eosinophilic oesophagitis from reflux oesophagitis. Histopathology. 2016;68(7):968–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson K, Lin E, Saffari H, et al. Food-specific antibodies in oesophageal secretions: association with trigger foods in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(6):997–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, Thomas CS, Gonsalves N, Achem SR. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62(4):489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1022–1033 e1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoepfer AM, Straumann A, Panczak R, et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1255–1266 e1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safroneeva E, Pan Z, King E, et al. Long-Lasting Dissociation of Esophageal Eosinophilia and Symptoms After Dilation in Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(4):766–775 e764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3–20 e26; quiz 21-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhan T, Ali A, Choi JG, et al. Model to Determine the Optimal Dietary Elimination Strategy for Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(11):1730–1737 e1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiramoto B, Zalewski A, Gregory D, et al. Low Prevalence of Extraesophageal Gastrointestinal Pathology in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(7):3080–3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn L, Nguyen B, Menard-Katcher C, Spencer L. IgG4+ cells are increased in the gastrointestinal tissue of pediatric patients with active eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis and decrease in remission. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55(1):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosaka S, Tanaka F, Nakata A, et al. Gastrointestinal IgG4 Deposition Is a New Histopathological Feature of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(8):3639–3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Letner D, Farris A, Khalili H, Garber J. Pollen-food allergy syndrome is a common allergic comorbidity in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahdavinia M, Bishehsari F, Hayat W, Elhassan A, Tobin MC, Ditto AM. Association of eosinophilic esophagitis and food pollen allergy syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(1):116–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder S, Ochkur SI, Shim KP, et al. Throat-derived eosinophil peroxidase is not a reliable biomarker of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1804–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saffari H, Baer K, Boynton KK, Gleich GJ, Peterson KA. Pharyngeal mucosa brushing does not correlate with disease activity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(5):1455–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smeekens JM, Baloh C, Lim N, et al. Peanut-Specific IgG4 and IgA in Saliva Are Modulated by Peanut Oral Immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(12):3270–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright BL, Fernandez-Becker NQ, Kambham N, et al. Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Responses in a Longitudinal, Randomized Trial of Peanut Oral Immunotherapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(6):1151–1159 e1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravi A, Marietta EV, Alexander JA, et al. Mucosal penetration and clearance of gluten and milk antigens in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53(3):410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohsaki A, Venturelli N, Buccigrosso TM, et al. Maternal IgG immune complexes induce food allergen-specific tolerance in offspring. J Exp Med. 2018;215(1):91–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.