Highlights

-

•

The rate of lacrosse-related injuries has fluctuated, with injuries per 100,000 significantly increasing from 2000 to 2012 and significantly decreasing from 2012 to 2016.

-

•

Boys were more likely than girls to be injured by contact with a stick or another player and were more likely to injure their upper extremities. A larger proportion of girls sustained concussions or closed head injuries.

-

•

Injuries differed by age. Older youth players were less often injured by contact with the lacrosse stick or another player.

-

•

Our findings support the continued development and implementation of risk-mitigating rules targeting specific sex and age categories among youth lacrosse players.

Keywords: Lacrosse, National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, Sex differences, Youth injuries

Abstract

Background

Lacrosse is one of the fastest-growing sports in the United States. Its rules regarding permitted contact differ by sex and age. There are no known studies using a nationally representative data set to analyze lacrosse injury patterns over several years by sex and age in the youth population.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed using data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System for youth aged 11–18 years who were treated for lacrosse-related injuries in U.S. emergency departments from 2000 to 2016. Based on our review of the case narratives, we created and coded a new injury-mechanism variable. We generated national estimates from 6406 cases.

Results

An estimated 206,274 lacrosse-related injuries to youths aged 11–18 years were treated in U.S. emergency departments from 2000 to 2016. The rate of injuries per 10,000 significantly increased from 1.9 in 2000 to a peak of 5.3 in 2012 (p < 0.0001), followed by a significant decrease to 3.4 in 2016 (p = 0.020). Injury mechanism, body part injured, and diagnosis differed by sex. Boys were 1.62 times (95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.25–2.09) more likely than girls to be injured by player-to-player contact. Girls were 2.21 times (95%CI: 1.96–2.49) more likely than boys to have non-contact injuries. Overall, as age increased, the percentage of injuries from lacrosse sticks decreased and player-to-player contact increased.

Conclusion

Despite additional protective regulations in the sport, lacrosse is an important source of injury where we continue to see differences by sex and age. This study supports the continuation, modification, and addition of rules aimed at reducing lacrosse injury risk.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Lacrosse is one of today's fastest-growing sports in the United States.1 In recent years, national participation has increased 225% among all ages.2 Lacrosse is also recognized as one of the fastest-growing youth team sports, with 450,000 players ≤14 years of age participating in 2016.1 In lacrosse, players compete to gain possession of a small ball and use sticks with woven nets, plastic heads, and metal or carbon-fiber shafts.3, 4, 5, 6 Youths aged 11–12 years, 13–14 years, and 15–18 years play in the under-13 age (U13) group, the U15 group, and the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) groups, respectively.7,8 Although the youth boys’ and girls’ versions of lacrosse are similar in regard to scoring and the use of sticks, the rules vary substantially in the levels of physical contact permitted and the protective equipment required by U.S. Lacrosse, the sport's national governing body (Table 1).3,4,6,9 In boys’ lacrosse, the level of allowable physical contact increases with age. In the U13 and U15 groups, boys are allowed a limited amount of body checking, but NFHS players are allowed to body check.3,9 Girls of any age are not allowed to body check, but some stick-checking below the shoulders is permitted.4,6

Table 1.

U.S. lacrosse regulations for boys and girls, 2015.a

| Regulation | Boy | Girl |

|---|---|---|

| Required protective equipment |

|

|

| Permitted level of physical contact | Body checking:

|

Body checking:

|

Regulations are implemented by U.S. Lacrosse, the national governing body of lacrosse.

U13 includes youths 11 and 12 years of age, and U15 includes youths 13 and 14 years of age.

Under NFHS age group, players are in high school and, thus, are typically between 15 and 18 years of age.

Abbreviations: NFHS = National Federation of State High School Associations; NOCSAE = National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment; U13 = under-13 age group; U15 = under-15 age group.

Despite these safety regulations and the enforcement of rules related to the use of safety gear, the risk of injury for adolescent lacrosse players is high. The rate of lacrosse injuries in youths has been reported to be 1.96 per 1000 athlete exposures for high school players10 and 6.4 per 1000 athlete exposures for players in recreational leagues.11 Players most commonly experience diagnoses of concussions,10, 11, 12, 13, 14 contusions and lacerations,11 and sprains and strains,10 as well as incurring injuries to the head, face, and lower extremities.10,15 Young players are commonly injured by contact with a stick or other equipment, a lacrosse ball, or another player.10,11,15

The current literature concerning injuries to adolescent lacrosse players is limited. Previously published research investigating lacrosse injuries among youth has examined only specific academic years,10,12,13,16,17 a single season,11,15 specific injuries (such as concussions or face and eye injuries),12,18, 19, 20, 21, 22 a single sex,15,23,24 collegiate level only,16,22, 23, 24 or high school level only.14,18,21,25 Research has also mixed lacrosse injuries with injuries occurring in other sports, such as football and soccer,12,13,26 or has compared lacrosse game injuries with practice injuries.23,24 Three prior research studies used nationally representative data to examine lacrosse-related injuries among all ages; 27, 28, 29 however, 2 of these studies analyzed only head injuries,28,29 and the remaining study did not investigate the mechanism of injury.27 The objective of the present study was to provide a broader examination of lacrosse-related injuries by describing lacrosse-related injuries sustained in all types of lacrosse play (game, practice, and recreational) that were treated in U.S. hospital emergency departments (EDs) from 2000 through 2016 for youths aged 11–18 years. Using this approach, we sought to understand the burden that lacrosse injuries in this age group place on EDs in the USA.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Data for patients treated in U.S. EDs for lacrosse-related injuries between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2016, were obtained through the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which is operated by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission for the reporting of injuries related to consumer products and sports activities. These data can be accessed via the NEISS query and data-builder website.30 The data are collected from a network of ∼ 100 hospitals, representing a stratified probability sample of >5000 hospitals with at least 6 beds and a 24-h ED.31 Professional NEISS coders review and transcribe all ED records, which include variables, such as patient demographics, injury diagnoses, dispositions from the ED, body parts injured, and products involved, along with brief narratives describing the injury.31 Statistical weights provided by the Consumer Product Safety Commission are assigned to the cases, allowing for the derivation of national estimates. The present study was exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Nationwide Children's Hospital.

2.2. Case selection criteria

All NEISS cases identified by the code for lacrosse (activity, apparel, or equipment; Code 1215) for patients 11 through 18 years of age were reviewed (n = 6578). This age range was selected for the study because there are aspects of the game that differ between players 11–18 years of age and individuals ≥19 and those ≤10 years of age. For example, compared to players 11–18 years of age, players ≥19 years typically play at the collegiate level, and for players ≤10 years of age, the purpose of gameplay and the rules regarding aspects of the game that may be associated with injury risk (e.g., safety equipment and permitted physical contact) are different.3,4,9 Cases were included when the narrative explicitly stated that the injury was caused by playing or participating in lacrosse-related activities. These activities could range from patients playing in their yards to patients playing in a game as part of a team. All case narratives were coded by the 1st author (JMB); ambiguous cases were reviewed and resolved by consensus with at least 1 other author. A total of 172 cases were excluded because the injury did not result from actively playing lacrosse (i.e., the patient got hives and a rash on the arms from the lacrosse pads or the patient was hit in the head by a rock thrown accidentally by a lacrosse stick). There were no fatalities in the original data set. A total of 6406 cases were included in the analysis.

2.3. Data

NEISS variables regarding patient age, body part injured, injury diagnosis, and disposition from the ED were regrouped. Age was categorized into 4 groups to reflect U.S. lacrosse's age-specific groups: 11–12 years old, 13–14 years old, 15–16 years old, and 17–18 years old. Body parts injured were categorized into 6 body parts: (1) lower extremities (LEs; including upper leg, knee, lower leg, ankle, foot, and toe); (2) upper extremities (UEs; including shoulder, upper arm, elbow, lower arm, wrist, hand, and finger); (3) head and neck; (4) face (including face, ears, mouth, and eyeballs); (5) trunk (including upper trunk, pubic region, and lower trunk); and (6) all parts of the body (including more than 50% of the body). Injury diagnoses were regrouped into 6 categories: (1) strain or sprain; (2) concussions or closed head injuries (CHIs) (including internal organ injuries to the head); (3) contusions or abrasions (including contusions, abrasions, and hematomas); (4) fractures or dislocations; (5) lacerations or avulsions (including lacerations, avulsions, punctures, crushing, and hemorrhages); and (6) other injuries (including injury by a foreign body, dental injury, nerve damage, internal organ injuries not to the head, anoxia, and not stated). Disposition was recoded into hospitalized (including patients who were admitted, transferred to another hospital, or held for observation) or not hospitalized (including patients who were treated and released or left against medical advice). The locale where the injury occurred was coded as (1) school; (2) place of recreation or sports; or (3) other (including home, farm, mobile home, street/highway, or other public property).

Case narratives were reviewed to create variables of the mechanisms of injury. These were categorized as (1) player-to-player contact (i.e., the patient came into contact with another player or the equipment the other player was wearing); (2) player-to-surface contact (i.e., the patient came into contact with the ground or a wall); (3) contact with a lacrosse stick; (4) contact with a lacrosse ball; (5) unspecified collision (i.e., cases where there was a known collision but the object involved in the collision was unknown); (6) non-contact (i.e., cases where there was no contact with the patient, such as a rolled ankle or twisted knee); or (7) other (including contact with the goal or net and all other cases where patients were injured).

2.4. Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All statistical analyses accounted for the complex sampling frame of the NEISS.31 SAS survey procedures were used to conduct the analyses and to account for the NEISS survey design. Bivariate comparisons, including sex differences, were conducted using Rao-Scott χ2 tests, and strength of association was assessed using the injury proportion ratio32 with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Statistical significance was assessed using α = 0.05 or 95%CI not containing 1.00. Because this study's population included any youth (player or not a player), injury rates per 10,000 youths 11–18 years of age were calculated using population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.33,34 Trend significance for the rate of lacrosse injuries over time was analyzed using linear regression. Trend analyses of portions of the study timeline were also analyzed using linear regression after visually and statistically assessing for linearity. All data reported are national estimates unless specified as actual unweighted cases, and all reported frequencies and distributions are derived from the weighted data. Actual case values <20 and weighted estimates <1200 were considered unstable and potentially unreliable.35

3. Results

3.1. Demographic features and overall injury trends

From 2000 through 2016, there were 6406 actual cases which, when weighted, represented an estimated 206,274 (95%CI: 109,467–303,082) lacrosse-related injuries to youths 11–18 years of age treated in U.S. EDs (Table 2). The mean patient age was 15.2 years (SE = 0.12). Most injuries were sustained by youths who were between 15 and 16 years old (36.6%). Patients were mostly boys (73.7%) injured at a place of recreation or sport (67.8%), but the vast majority (98.4%) were not hospitalized for their injuries.

Table 2.

Characteristics of lacrosse-related injuries among youths aged 11–18 years treated in U.S. emergency departments, 2000–2016.

| Overall |

Sex difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual case | National estimatea | 95% confidence interval | %b | Boy (%) | Girl (%) | pc | |

| Totald | 6406 | 206,274 | 109,467–303,082 | 100.0 | 73.7 | 26.3 | <0.0001 |

| Boy | 4817 | 152,058 | 83,736–220,380 | 73.7 | 100.0 | 0 | |

| Girl | 1589 | 54,216 | 23,944–84,488 | 26.3 | 0 | 100.0 | |

| Age (year) | 0.2677 | ||||||

| 11–12 | 701 | 20,225 | 8439–32,011 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 9.1 | |

| 13–14 | 1708 | 52,897 | 23,043–82,751 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 27.5 | |

| 15–16 | 2320 | 75,566 | 41,290–109,843 | 36.6 | 36.2 | 37.9 | |

| 17–18 | 1677 | 57,586 | 34,009–81,163 | 27.9 | 28.8 | 25.6 | |

| Diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Strain/sprain | 1542 | 52,506 | 25,367–79,646 | 25.4 | 21.3 | 37.1 | |

| Contusion/abrasion | 1399 | 50,516 | 24,151–76,880 | 24.5 | 25.5 | 21.8 | |

| Fracture/dislocation | 1360 | 42,929 | 22,537–63,321 | 20.8 | 24.5 | 10.6 | |

| Concussion/CHI | 1132 | 29,710 | 16,923–42,497 | 14.4 | 13.5 | 17.0 | |

| Laceration/avulsion | 419 | 14,310 | 7759–20,862 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 5.1 | |

| Other | 554 | 16,303 | 9029–23,576 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 8.4 | |

| Body part injurede | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Upper extremity | 2321 | 78,127 | 39,872–116,382 | 37.9 | 42.4 | 25.2 | |

| Finger | 585 | 21,644 | 10,016–33,272 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 9.3 | |

| Shoulder | 637 | 20,406 | 11,637–29,175 | 9.9 | 12.3 | 3.2 | |

| Wrist | 341 | 12,276 | 5316–19,237 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 5.2 | |

| Lower arm | 326 | 9617 | 4755–14,479 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 1.9f | |

| Hand | 234 | 7841 | 3201–12,481 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 4.0 | |

| Elbow | 151 | 4472 | 2470–6474 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 1.0 | |

| Upper arm | 47 | 1871 | 750–2992 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.6f | |

| Lower extremity | 1414 | 48,960 | 23,181–74,739 | 23.7 | 19.4 | 35.9 | |

| Ankle | 603 | 22,023 | 10,862–33,184 | 10.7 | 7.5 | 19.5 | |

| Knee | 471 | 14,568 | 6608–22,528 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 9.6 | |

| Lower leg | 150 | 5080 | 1900–8259 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | |

| Foot | 120 | 4651 | 1493–7808 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 3.6 | |

| Upper leg | 48 | 1592 | 785–2399 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.5f | |

| Toe | 22 | 1047 | 289–1805 | 0.5f | 0.5f | 0.4f | |

| Head/neck | 1473 | 39,607 | 22,716–56,499 | 19.2 | 18.7 | 20.6 | |

| Face | 575 | 20,314 | 11,343–29,286 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 11.2 | |

| Trunk | 568 | 17,842 | 9508–26,176 | 8.7 | 9.6 | 6.1 | |

| All parts of body | 46 | 1292 | 581–2003 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.0 | |

| Disposition | 0.0004 | ||||||

| Not hospitalizedf | 6211 | 203,065 | 107,138–298,992 | 98.4 | 98.2 | 99.3 | |

| Hospitalizedg | 195 | 3209 | 1786–4633 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.7 | |

| Location | 0.2238 | ||||||

| Place of sports/recreation | 4285 | 126,069 | 66,857–185,281 | 67.8 | 69.4 | 63.4 | |

| School | 1392 | 55,501 | 14,969–96,033 | 29.8 | 28.4 | 33.9 | |

| Otherh | 118 | 4411 | 1146–7675 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | |

| Injury mechanism | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Contact with stick | 1211 | 41,852 | 21,333–62,372 | 27.6 | 28.6 | 24.7 | |

| Player-to-player contact | 901 | 26,315 | 15,010–37,620 | 17.4 | 19.3 | 11.9 | |

| Contact with ball | 631 | 22,140 | 10,175–34,104 | 14.6 | 12.7 | 19.9 | |

| Collision, unspecified | 729 | 21,538 | 12,970–30,106 | 14.2 | 15.9 | 9.5 | |

| Contact with surface | 654 | 18,371 | 9312–27,430 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 11.8 | |

| Non-contact | 510 | 17,798 | 8359–27,236 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 19.8 | |

| Other | 115 | 3616 | 1815–5418 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

Some categories do not total 206,274 because of rounding.

Percentage of national estimate. Missing values were not included in percentage calculations. Some categories do not total 100% because of rounding.

p was calculated by Rao-Scott χ2 tests for the sex variable by each characteristic. Statistically significant p values <0.05 are in boldface type.

Some categories have missing values (actual n): body part injured (n = 9), location (n = 611), and injury mechanism (n = 1655).

Actual case values <20 or estimates <1200 considered unstable and potentially unreliable. These values are indicated by superscript.

“Not hospitalized” includes treated and released, examined and released without treatment, left without being seen, or left against medical advice.

“Hospitalized” includes admitted for hospitalization, treated and transferred to another hospital, or held for observation.

“Other” includes home, street, mobile or manufactured home, and other public property.

Abbreviation: CHI = closed head injury.

Although the overall rate of injuries significantly increased (85.3%) over the 17-year study period (slope = 0.18; p = 0.001) (Fig. 1), this trend was not linear. The rate of injuries significantly increased (186.8%) from 1.9 per 10,000 youths in 2000 (n = 6014) to its peak of 5.3 per 10,000 youths in 2012 (n =17,543; slope = 0.33; p < 0.0001), after which the rate significantly decreased (34.4%) from 2012 to 3.4 per 10,000 youths in 2016 (slope = –0.44; p = 0.020).

Fig. 1.

Rate of lacrosse-related injuries per 10,000 youths aged 11–18 years, 2000–2016.

The injury rate for girls increased 83.5% over the study period, from 1.2 per 10,000 girls in 2000 (n = 1867) to 2.2 per 10,000 girls in 2016 (n = 3541). The annual change in the rate of injuries for girls was statistically significant: 0.10 injuries per 10,000 girls (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). The rate of lacrosse injuries in boys 11–18 years of age was 2.5 per 10,000 boys in 2000 (n = 4147) and significantly increased (85.8%) to 4.6 per 10,000 boys in 2016 (n = 7863; slope = 0.25; p = 0.002). The peak injury rate for girls was 2.9 per 10,000 girls in 2012, while the peak injury rates for boys was 7.6 per 10,000 boys in 2010 and 7.5 per 10,000 boys in 2012. After peaking in 2012, there was no significant decrease in the rate of injury for girls (slope = –0.096; p = 0.386), but after peaking in 2010, there was a significant decrease in the rate of injury for boys (slope = –0.497; p = 0.006).

For each age group, the age-specific injury rate per 10,000 youths increased significantly from 2000 through 2016 (Fig. 2). The rate reached its peak in 2013 for youths aged 11–12 years (2.7 per 10,000 youths; n = 2212) and for youths aged 13–14 years (6.44 per 10,000 youths; n = 5291). Youths aged 15–16 years reached their peak injury rate in 2011 at 7.55 per 10,000 youths (n = 6236), and youths aged 17–18 years had a peak injury rate of 6.37 per 10,000 youths in 2012 (n = 5297). The age-specific injury rates per 10,000 youths for all age groups increased significantly from 2000 through their specific peaks (p < 0.0001 for all) and then decreased, but not significantly, from their respective peak year through 2016 (11–12 years: p = 0.624; 13–14 years: p = 0.245; 15–16 years: p = 0.068; 17–18 years: p = 0.063). The age-specific injury rates for those aged 11–12 years were consistently lower than all other age-specific rates throughout the study period. Those aged 15–16 years had the highest age-specific injury rate for most years, except in 2007 and 2013.

Fig. 2.

Age-specific rate of lacrosse-related injuries per 10,000 youths, 2000–2016.

3.2. Injured body parts and diagnoses

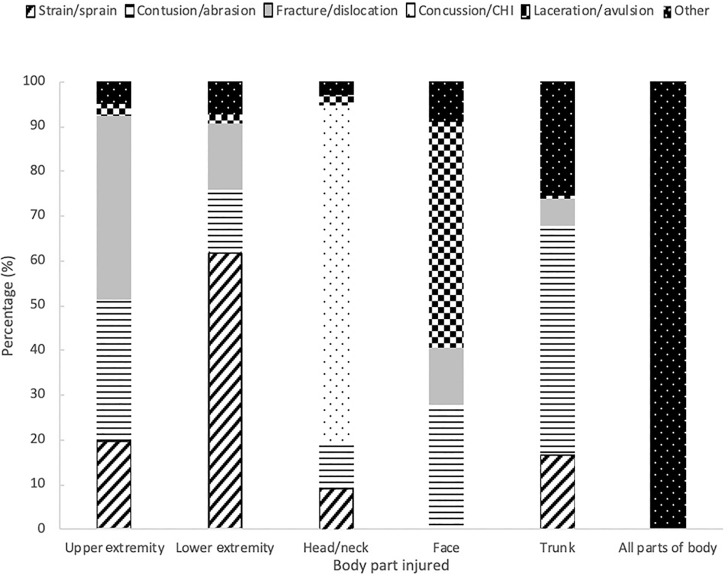

The most commonly injured body parts were in the UEs (37.9%) and LEs (23.7%) (Table 2). The most common diagnoses were strains or sprains (25.4%) and contusions or abrasions (24.5%). Those with UE injuries were 4.81 times (40.9% vs. 8.5%; 95%CI: 3.89–5.94) more likely to sustain a fracture or dislocation, and those with LE injuries were 4.33 times (61.5% vs. 14.2%; 95%CI: 3.80–4.93) more likely to be diagnosed with a strain or sprain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of body parts injured by diagnosis among youths aged 11–18 years with lacrosse-related injuries, 2000–2016. CHI = closed head injury.

3.3. Mechanism of injury

The mechanism of injury was determined in 74.2% of cases (n = 4751), representing an estimated 151,630 (73.5%) cases. Overall, the most common mechanisms of injury were contact with a stick (27.6%) and player-to-player contact (17.4%) (Table 2). The proportion of injuries resulting from contact with a stick decreased as age increased: 36.3% of patients aged 11–12 years compared to 23.6% of patients aged 17–18 years. As patient age increased, the percentage of players injured by player-to-player contact (15.6% of patients 11–12 years vs. 21.1% of patients 17–18 years) also increased.

Those with player-to-player contact injuries were 1.70 times (35.7% vs. 21.0%; 95%CI: 1.54–1.87) more likely to sustain a head or neck injury and 1.82 times (28.2% vs. 15.5%; 95%CI: 1.61–2.06) more likely to sustain a concussion or CHI compared to patients with injuries by all other mechanisms. The proportion of players diagnosed with a concussion or CHI and injured by player-to-player contact increased as age increased, representing 20.5% of players aged 13–14 years and 33.9% of players aged 17–18 years.

3.4. Sex characteristics

Most patients who sustained lacrosse-related injuries were boys (73.7%). The most common mechanisms of injury in boys were contact with a stick (28.6%) and contact with another player (19.3%), whereas the most common mechanisms of injury in girls were contact with a stick (24.7%), contact with a ball (19.9%), and non-contact (19.8%) (Table 2). Among boys, the rate of injuries from contact with a stick peaked in 2008 at 1.6 per 10,000 boys and decreased, although not significantly, to 1.0 per 10,000 boys in 2016 (slope = –0.034; p = 0.168). The rate of injuries from player-to-player contact for boys peaked in 2010 at 1.4 per 10,000 boys but also did not change significantly during the study period (slope = 0.025; p = 0.473).

Boys most often injured their UEs (42.4%), while girls more often injured their LEs (35.9%). Boys were 2.31 times (24.5% vs. 10.6%; 95%CI: 1.81–2.94) more likely than girls to sustain a fracture or dislocation. Boys were 1.62 times (19.3% vs. 11.9%; 95%CI: 1.25–2.09) more likely than girls to be injured by player-to-player contact. Player-to-player contact injuries most commonly resulted in concussions or CHIs for boys (29.1%) but resulted in strains or sprains for girls (27.6%). Girls were more than twice (injury proportion ratio = 2.21; 19.6% vs. 8.9%; 95%CI: 1.96–2.49) as likely to have non-contact injuries and were 1.74 times (37.1% vs. 21.3%; 95%CI: 1.64–1.85) more likely to sustain a strain or sprain compared to boys.

Girls were 1.26 times (17.0% vs. 13.5%; 95%CI: 1.07–1.47) more likely to be diagnosed with a concussion or CHI compared to boys. The most common causes of concussions or CHIs among girls were contact with a ball (31.6%) and contact with a stick (31.6%). Among boys, the most common cause of concussions or CHIs was player-to-player contact (34.6%).

4. Discussion

Injury trends in lacrosse have fluctuated in the past 2 decades, and numerous factors may be involved in these changes. During the 17-year study period, an estimated 206,274 youth lacrosse players were treated in U.S. EDs for lacrosse-related injuries, averaging approximately 33 visits daily. Despite the overall rate of lacrosse-related injuries’ increasing more than 80% from 2000 through 2016, this rate significantly decreased since its peak in 2012. This decrease in the injury rate may have been influenced by the implementation and enforcement of new rules by the NFHS rules committee aimed at mitigating injury risk for youth lacrosse players, particularly boys, because youth leagues often follow the committee's rules.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 The decrease may have also been influenced by the surge in urgent care facilities that serve as alternatives to EDs for issues such as injuries.46

Sports organizations attempt to increase the safety of gameplay through the implementation or augmentation of rules. For youth lacrosse, the NFHS rules committee intended to mitigate lacrosse-related injuries by passing regulations that targeted sex-specific risks because past studies showed that males and females had different injury characteristics.10,14,19,47 For example, because girls were injuring their eyes and faces at higher rates than boys, which may be partially explained by the fact that boys were already required to wear helmets,19,48 the committee mandated that girls wear protective eyewear starting in 2005 and mouthpieces that covered their leading arch beginning in 2015.19,49 Likewise, boys were being injured by player-to-player contact or contact with a stick more often than girls.10,11,14,15 Consequently, the committee introduced regulations reducing body and stick checking for the male players, including boys; for example, the committee limited stick checking of another player who is receiving a pass (2009), increased the severity of penalties for hits to the head and neck (2012), defined body checks to defenseless players as illegal (2014), and restricted how players could assemble their sticks so that it would be easier for a defensive player to dislodge the ball (2016).36,38,41

The findings from our study are consistent with past research indicating that injury mechanisms, body parts injured, and diagnoses differ by sex,10,11,14 and these findings support the continuation of current injury-risk mitigation regulations. Similar to past research, our results show that a higher percentage of boys are injured due to contact with a stick or with another player compared to girls, which is probably due to that fact that more contact is allowed in boys’ lacrosse than in girls’ lacrosse.10,11 For boys, the rates of injuries resulting from contact with a stick and contact with another player peaked in 2008 and in 2010, respectively, after which the rate did not change statistically. Although these rates did not decrease significantly, they also did not increase. This may be attributed to the NFHS's injury prevention regulations regarding stick checking, which passed in 2009.36

Consistent with previous findings,10,11,14,28 we found that a larger proportion of girls had head or face injuries than boys, despite wearing protective eyewear. Contrasting with most previous studies10,12,15,25 (except for one29), we found that a higher proportion of girls were diagnosed with concussions or CHIs, which may be due to the fact that girls are not mandated to wear helmets. In the spring 2017 season, the American Society for Testing and Materials unveiled headgear specifically designed for the female game, but U.S. Lacrosse has yet to mandate that females wear it. Many argue that introducing helmets into the girls’ game promotes game violence, increases injury risk, and is unnecessary because helmets have not been proven to prevent concussions in any sport.50 However, a previous study of the biomechanics of head impacts among female lacrosse players showed that helmets decrease the force of a hit to the head by a ball or stick, the 2 most common causes of concussions and CHIs among girls.51 Another possible explanation for a larger proportion of girls’ being diagnosed with concussions or CHIs is that compared to boys, girls are more likely to experience severe concussive symptoms, including significantly greater neurocognitive declines, after injury.52,53 Consequently, girls may be more likely to report symptoms and to present to EDs for their concussions compared to boys.

Boys and girls also differed by injury mechanisms not addressed by NFHS rulings. Boys more commonly sustained fractures and were more likely to sustain a UE injury, which are common in contact sports, such as boys’ lacrosse, football, and ice hockey.22,54,55 We found that girls had a higher proportion of LE injuries than boys, which is supported by past research.10,14,25 Girls may be predisposed to non-contact and LE injuries due to biological factors such as hormones, muscle development, and joint structure.56 Furthermore, these injury discrepancies may exist because boys’ and girls’ lacrosse have fundamental differences, in that each involves different protective gear and permissible physical contact, leading to opportunities for dissimilarities in injury characteristics by sex. Boys’ lacrosse provides players with the opportunity to use their bodies and their sticks to gain a competitive advantage.3,57 In contrast, girls’ lacrosse has rules that ban body checking and strictly regulate stick checking. Girls’ lacrosse places an emphasis on footwork and body positioning in order to gain a competitive advantage, which often requires more frequent stopping and starting across a larger field.4,57

The age groups analyzed in the study were susceptible to different types of injuries. As age increased, the percentage of patients injured by contact with a stick decreased, while the proportion of patients injured by player-to-player contact increased. Players aged from 17–18 years most often experienced lacerations and avulsions, potentially stemming from more competitive and physical play compared to younger age groups. The results also indicate that players aged from 11–12 years consistently had the lowest age-specific injury rate, while players aged from 15–16 years most often had the highest age-specific injury rate throughout the study period. Similar to the differences in injuries in boys’ and girls’ lacrosse, the differences in injuries between age groups may be influenced by the variation in permissible physical contact and stick checking, as well as the differences in skill level and experience.3,4

4.1. Strengths and limitations

There are both strengths and limitations to our study. Some of its strengths come from our use of a large, nationally representative data set that, to our knowledge, is being used for the first time to characterize lacrosse-related injuries exclusively. However, among the limitations of our study is the fact that the NEISS data set underestimates the total number of lacrosse-related injuries because not all injuries are treated in ED settings. Additionally, because of a lack of detail in some case narratives, we were unable to differentiate between injuries that occurred during informal vs. formal play. There are national rules for high school sports, but youth league rules are determined by organizations; however, these rules generally adhere to the rules set by the nationally recognized organization U.S. Lacrosse.3,4 The increased participation in lacrosse may contribute to the observed increase in the injury rate over the study period. We could not compare injury rates directly in our study to injury rates from previous studies that used athlete exposures to determine injury rate.10, 11, 12,15 We used U.S. Census data to determine injury rate because the NEISS data did not provide information on the number of lacrosse players or on the number of games and practices each player participated in. Despite these limitations, we do not believe that they affected the interpretations of the results.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study support recommendations for continued development and implementation of rules intended to mitigate injury risk by targeting sex-specific injury characteristics for youth lacrosse players. All youth playing any level of lacrosse, including recreational lacrosse, should wear protective equipment to reduce their injury risk. As players age, and competition and physical abilities increase, it is important for coaches and parents to emphasize the importance of players’ wearing required protective equipment in both formal and informal lacrosse play. It is recommended that coaches and parents use safety resources through organizations such as U.S. Lacrosse to educate themselves about current safety research and protocols in lacrosse.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We thank Roxanne Clark for her contribution to this project.

Authors’ contributions

JMB conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed and coded case narratives, carried out the initial data analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; RJM carried out the data analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; KJR conceptualized and designed the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript; JY reviewed and revised the manuscript; LBM conceptualized and designed the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.08.006.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Logue B. National Lacrosse Participation tops 825,000 players. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/blog/national-lacrosse-participation-tops-825000-players. [accessed 07.01.2019].

- 2.US Lacrosse. 2016 Participation survey. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/about-us-lacrosse/participation-survey-2016.pdf. [accessed 15.06.2017].

- 3.US Lacrosse. 2017 Youth boys’ rulebook. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/rules/2017-boys-youth-rules.pdf. [accessed 21.02.2017].

- 4.US Lacrosse. 2017 Youth girls’ rulebook. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/rules/2017-girls-youth-rules.pdf. [accessed 21.02.2017].

- 5.US Lacrosse. 2019 Youth boys’ rulebook. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/rules/2019-boys-youth-rulebook.pdf. [accessed 04.04.2019].

- 6.US Lacrosse. 2019 Youth girls’ rulebook. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/rules/2019-girls-youth-rulebook.pdf. [accessed 04.04.2019].

- 7.Hopper B. Here's what you need to know about the new US lacrosse rules. Available at:https://www.bluestarlacrosse.com/news_article/show/704721-here-s-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-new-us-lacrosse-rules. [accessed 17.04.2019].

- 8.Lacrosse U. Fall 2012–2013 boys’ youth rules. Available at: http://vblax.com/Page.asp?n=73813&org=VBLAX.ORG. [accessed 17.04.2019].

- 9.US Lacrosse. 2015 Rules for boys’ youth lacrosse. Available at:http://files.leagueathletics.com/Images/Club/15784/GLL%202015/docs/2015-boys-youth-rules.pdf. [accessed 04.04.2019].

- 10.Xiang J, Collins CL, Liu D, McKenzie LB, Comstock RD. Lacrosse injuries among high school boys and girls in the United States: Academic years 2008–2009 through 2011–2012. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2082–2088. doi: 10.1177/0363546514539914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoln AE, Yeger-McKeever M, Romani W, Hepburn LR, Dunn RE, Hinton RY. Rate of injury among youth lacrosse players. Clin J Sport Med. 2014;24:355–357. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connor KL, Baker MM, Dalton SL, Dompier TP, Broglio SP, Kerr ZY. Epidemiology of sport-related concussions in high school athletes: National Athletic Treatment, Injury and Outcomes Network (NATION), 2011–2012 through 2013–2014. J Athl Train. 2017;52:175–185. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:747–755. doi: 10.1177/0363546511435626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinton RY, Lincoln AE, Almquist JL, Douoguih WA, Sharma KM. Epidemiology of lacrosse injuries in high school-aged girls and boys: A 3-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1305–1314. doi: 10.1177/0363546504274148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr ZY, Caswell SV, Lincoln AE, Djoko A, Dompier TP. The epidemiology of boys’ youth lacrosse injuries in the 2015 season. Inj Epidemiol. 2016;3:3. doi: 10.1186/s40621-016-0068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds BB, Patrie J, Henry EJ, et al. Quantifying head impacts in collegiate lacrosse. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2947–2956. doi: 10.1177/0363546516648442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierpoint LA, Lincoln AE, Walker N, et al. The first decade of web-based sports injury surveillance: descriptive epidemiology of injuries in US high school boys’ lacrosse (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) and National Collegiate Athletic Association men's lacrosse (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) J Athl Train. 2019;54:30–41. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-200-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lincoln AE, Caswell SV, Almquist JL, Dunn RE, Hinton RY. Video incident analysis of concussions in boys’ high school lacrosse. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:756–761. doi: 10.1177/0363546513476265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln AE, Hinton RY, Almquist JL, Lager SL, Dick RW. Head, face, and eye injuries in scholastic and collegiate lacrosse: A 4-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:207–215. doi: 10.1177/0363546506293900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French C, Kelley R. Laryngeal fractures in lacrosse due to high-speed ball impact. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:735–738. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, Fabricant PD, Lawrence JT, Ganley TJ. Sport-specific yearly risk and incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears in high school athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2716–2723. doi: 10.1177/0363546515617742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardner EC, Chan WW, Sutton KM, Blaine TA. Shoulder injuries in men's collegiate lacrosse, 2004–2009. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2675–2681. doi: 10.1177/0363546516644246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dick R, Romani WA, Agel J, Case JG, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's lacrosse injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance system, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42:255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dick R, Lincoln AE, Agel J, Carter EA, Marshall SW, Hinton RY. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women's lacrosse injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance system, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42:262–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warner K, Savage J, Kuenze CM, Erkenbeck A, Comstock RD, Covassin T. A comparison of high school boys’ and girls’ lacrosse injuries: Academic years 2008–2009 through 2015–2016. J Athl Train. 2018;53:1049–1055. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-312-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yard EE, Comstock RD. Injuries sustained by pediatric ice hockey, lacrosse, and field hockey athletes presenting to United States emergency departments, 1990–2003. J Athl Train. 2006;41:441–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khodaee M, Kirk K, Pierpoint LA, Dixit S. Epidemiology of lacrosse injuries treated at the United States emergency departments between 1997 and 2015. Res Sports Med. 2020;28:426–436. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2020.1721499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamond PT, Gale SD. Head injuries in men's and women's lacrosse: A 10-year analysis of the NEISS database. Brain Inj. 2001;15:537–544. doi: 10.1080/02699050010007362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooley CN, Beranek TJ, Warpinski MA, Alexander R, Esquivel AO. A comparison of head injuries in male and female lacrosse participants seen in US emergency departments from 2005 to 2016. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System: Highlights, data and query builder. Available at: https://www.cpsc.gov/cgibin/NEISSQuery/home.aspx. [accessed 09.04.2017].

- 31.U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System: A tool for researchers. Available at: https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2000d015.pdf. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 32.Knowles SB, Kucera KL, Marshall SW. Commentary: the injury proportion ratio: What's it all about? J Athl Train. 2010;45:475–479. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Census Bureau. Intercensal estimates of the resident population by single year of age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010. Available at:https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal-2000-2010-national.html. [accessed 18.05.2017].

- 34.U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States: April 1, 2010, to July 1, 2016. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2016/demo/popest/nation-detail.html. [accessed 18.05.2017].

- 35.U.S. Consumer Product and Safety Commission. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) Online. Explanation of NEISS estimates obtained through the CPSC web-site. Available at: https://www.cpsc.gov/cgibin/NEISSQuery/webestimates.html. [accessed 06.01.2020].

- 36.National Federation of State High School Associations. NFHS rules changes affecting risk (1982–2016). Available at:https://www.nfhs.org/media/1017463/1982-2016_nfhs_risk_minimization_rules.pdf. [accessed 11.07.2017].

- 37.National Federation of State High School Associations. Boys lacrosse rules changes–2016. Available at: http://www.nfhs.org/sports-resource-content/boys-lacrosse-rules-changes-2016. [accessed 20.06.2017].

- 38.Inside Lacrosse. NFHS approves new high school boys rule changes to minimize injury. Available at:http://www.insidelacrosse.com/article/nfhs-approves-new-high-school-boys-rule-changes-to-minimize-injury/36068. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 39.Zimmerman D. 2011 and 2012 approved rule changes memo. Available at: http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/rules/mlax/2010/2011-12approvedruleschangesmemo.pdf. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 40.Laxpower. Rule changes for boys’ lacrosse for the 2011 season. Available at: http://www.laxpower.com/laxnews/news.php?story=20823. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 41.Inside Lacrosse. Substitution rule changes made, body checks targeted in high school lacrosse. Available at:http://www.insidelacrosse.com/article/substitution-rule-changes-made-body-checks-targeted-in-high-school-lacrosse/20984. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 42.U.S. Lacrosse. Why women's lacrosse is not played with additional protective equipment. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/sites/default/files/public/documents/coaches/safety-issues-in-girls-and-womens-lacrosse.pdf. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 43.National Federation of State High School Associations. High school boys’ lacrosse rules revisions focus on pre-game management and risk minimization. Available at:http://old.nfhs.org/content.aspx?id=3514. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 44.National Federation of State High School Associations. 2013 NFHS boys’ lacrosse rules interpretation meeting. Available at:http://www.sdcloa.com/images/2013_Boys_Lacrosse.pdf. [accessed 20.06.2017].

- 45.National Federation of State High School Associations. 2012 NFHS boys lacrosse rules book. Available at: http://files.leagueathletics.com/Text/Documents/7153/26278.pdf. [accessed 30.06.2017].

- 46.Yee T, Lechner AE, Boukus ER. The surge in urgent care centers: Emergency department alternative or costly convenience? Res Brief. 2013;26:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter EA, Westerman BJ, Lincoln AE, Hunting KL. Common game injury scenarios in men's and women's lacrosse. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2010;17:111–118. doi: 10.1080/17457300903524888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lincoln AE, Caswell SV, Almquist JL, et al. Effectiveness of the women's lacrosse protective eyewear mandate in the reduction of eye injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:611–614. doi: 10.1177/0363546511428873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohanian P. 2015 rule changes announced for girls’ high school and youth lacrosse. Available at:https://www.uslacrosse.org/blog/2015-rule-changes-announced-for-girls%E2%80%99-high-school-and-youth-lacrosse. [accessed 16.05.2019].

- 50.Acabchuk RL, Johnson BT. Helmets in women's lacrosse: What the evidence shows. Concussion. 2017;2:CNC39. doi: 10.2217/cnc-2017-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crisco JJ, Costa L, Rich R, Schwartz JB, Wilcox B. Surrogate headform accelerations associated with stick checks in girls’ lacrosse. J Appl Biomech. 2015;31:122–127. doi: 10.1123/jab.2014-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandel NK, Schatz P, Goldberg KB, Lazar M. Sex-based differences in cognitive deficits and symptom reporting among acutely concussed adolescent lacrosse and soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:937–944. doi: 10.1177/0363546516677246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Covassin T, Schatz P, Swanik CB. Sex differences in neuropsychological function and post-concussion symptoms of concussed collegiate athletes. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:345–351. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000279972.95060.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nation AD, Nelson NG, Yard EE, Comstock RD, McKenzie LB. Football-related injuries among 6 to 17-year-olds treated in US emergency departments, 1990–2007. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50:200–207. doi: 10.1177/0009922810388511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacCormick L, Best TM, Flanigan DC. Are there differences in ice hockey injuries between sexes?: A systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2 doi: 10.1177/2325967113518181. 2325967113518181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ivković A, Franić M, Bojanić I, Pećina M. Overuse injuries in female athletes. Croat Med J. 2007;48:767–778. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2007.6.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vescovi JD, Brown TD, Murray TM. Descriptive characteristics of NCAA Division I women lacrosse players. J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.