Highlights

-

•

Salivary microRNAs (miRNAs) are promising biomarkers for identifying sports-related concussion.

-

•

This study investigated if concussion-related miRNAs are confounded by exercise.

-

•

Two miRNAs decreased with acute exercise and 23 changed over an athletic season.

-

•

Levels of miR-27a and miR-30a distinguished concussed and non-concussed athletes.

-

•

Saliva miRNAs may identify sports concussion without confounding effects of exercise.

Keywords: Biomarker, Contact sports, Football, RNA, Traumatic brain injury

Abstract

Background

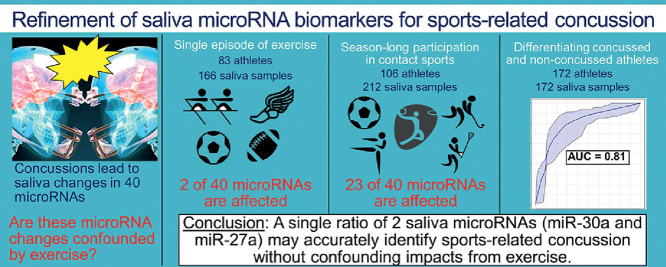

Recognizing sport-related concussion (SRC) is challenging and relies heavily on subjective symptom reports. An objective, biological marker could improve recognition and understanding of SRC. There is emerging evidence that salivary micro-ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) may serve as biomarkers of concussion; however, it remains unclear whether concussion-related miRNAs are impacted by exercise. We sought to determine whether 40 miRNAs previously implicated in concussion pathophysiology were affected by participation in a variety of contact and non-contact sports. Our goal was to refine a miRNA-based tool capable of identifying athletes with SRC without the confounding effects of exercise.

Methods

This case-control study harmonized data from concussed and non-concussed athletes recruited across 10 sites. Levels of salivary miRNAs within 455 samples from 314 individuals were measured with RNA sequencing. Within-subjects testing was used to identify and exclude miRNAs that changed with either (a) a single episode of exercise (166 samples from 83 individuals) or (b) season-long participation in contact sports (212 samples from 106 individuals). The miRNAs that were not impacted by exercise were interrogated for SRC diagnostic utility using logistic regression (172 samples from 75 concussed and 97 non-concussed individuals).

Results

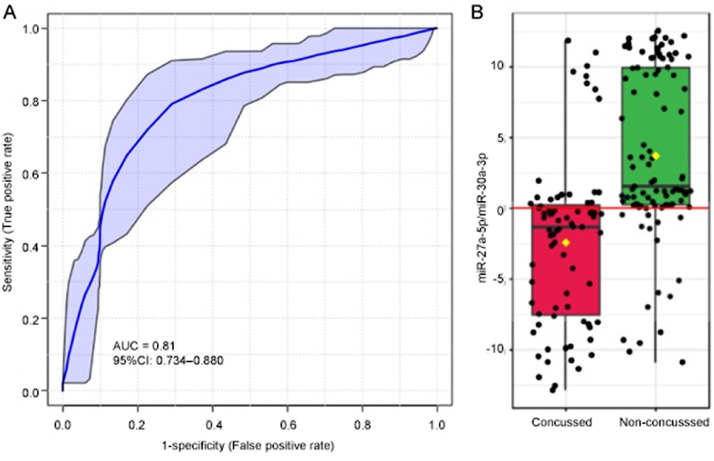

Two miRNAs (miR-532-5p and miR-182-5p) decreased (adjusted p < 0.05) after a single episode of exercise, and 1 miRNA (miR-4510) increased only after contact sports participation. Twenty-three miRNAs changed at the end of a contact sports season. Two of these miRNAs (miR-26b-3p and miR-29c-3p) were associated (R > 0.50; adjusted p < 0.05) with the number of head impacts sustained in a single football practice. Among the 15 miRNAs not confounded by exercise or season-long contact sports participation, 11 demonstrated a significant difference (adjusted p < 0.05) between concussed and non-concussed participants, and 6 displayed moderate ability (area under curve > 0.70) to identify concussion. A single ratio (miR-27a-5p/miR-30a-3p) displayed the highest accuracy (AUC = 0.810, sensitivity = 82.4%, specificity = 73.3%) for differentiating concussed and non-concussed participants. Accuracy did not differ between participants with SRC and non-SRC (z = 0.5, p = 0.60).

Conclusion

Salivary miRNA levels may accurately identify SRC when not confounded by exercise. Refinement of this approach in a large cohort of athletes could eventually lead to a non-invasive, sideline adjunct for SRC assessment.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Sport-related head trauma is one of the most common causes of concussion.1 Field-side assessment of sport-related concussion (SRC) relies on subjective symptom reports. However, some athletes may conceal symptoms to keep playing.2 Neurocognitive and balance assessments may also be administered, but these can be manipulated to expedite return to play.3,4 As a result, there has been much interest in developing a biological test (i.e., biomarker) for concussion.5 Biomarkers have been defined by the World Health Organization as “a substance, structure, or process that can be measured in the body or its products and influence or predict the incidence of outcome or disease”.6 A biomarker would add objectivity to the diagnosis and management of SRC, thereby reducing external pressures on athletes to report symptoms. Such a test might also be used to stratify biological phenotypes within SRC, leading to individualized prognoses and treatment protocols.7

There is growing evidence that levels of micro-ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) are altered in the cerebrospinal fluid,8 blood,9,10 and saliva11,12 of individuals with concussion. Salivary miRNAs, in particular, possess several qualities of an ideal SRC biomarker: (1) released from cranial nerves in the oropharynx within minutes of head impact,13 these molecular “switches” provide a rapid window into the physiology of the injured brain; (2) certain miRNAs are highly enriched within neurons, yielding a brain-specific signature;14,15 and (3) neurons can package miRNAs within protective vesicles,16 which renders them stable, and easily measured through a non-invasive collection process.12 Recently, we demonstrated that salivary miRNA levels could identify individuals with concussion with similar accuracy to traditional balance and neuropsychological measures, and pairing salivary miRNA measures with subjective symptom reports could enhance diagnostic accuracy.17 Successful application of saliva miRNA technology will require researchers to determine how individual characteristics (such as previous concussion history) to impact miRNA levels, while thoroughly investigating test–retest reliability and change indices.18,19 Application as a sideline tool for SRC will also require an understanding of how acute and chronic exercise impacts saliva miRNA levels.

Individual miRNAs that reflect the physiological changes occurring with exertion, cumulative fatigue, minor musculoskeletal injuries, or enhanced conditioning may be unsuitable for SRC detection.20 Several studies have examined the impact of contact and non-contact sports participation on blood miRNA levels.21, 22, 23 Several studies seeking to develop saliva miRNA biomarkers for concussion have utilized athletes from specific contact sports as controls.13,17,24 However, few studies have specifically examined the acute response of saliva miRNAs to exercise.25,26 To our knowledge, no study has described saliva miRNA dynamics across a wide range of contact and non-contact sports or determined the effects of season-long contact sport participation on saliva miRNA levels. Such knowledge is critical for development of accurate miRNA biomarkers of SRC because saliva miRNAs that change during season-long sport participation may confound comparisons with pre-season baseline levels. Likewise, saliva miRNAs that change during acute exercise may confound field-side SRC tests. The purpose of this study was to identify and exclude saliva miRNAs confounded by exercise, in order to refine a saliva miRNA approach for sideline detection of SRC.

We hypothesized that a subset of 40 miRNAs previously shown to identify concussion17,27 would be impacted by a single episode of exercise or display longitudinal accumulation across an entire season of contact sport participation, rendering them unsuitable as concussion biomarkers. We posited that the remaining miRNAs (i.e., those unaffected by exercise) could accurately differentiate athletes with SRC from peers with recent participation in contact and non-contact sports. To our knowledge, this is the first study to harmonize salivary miRNA profiles from a large cohort of athletes participating in both contact and non-contact sports during periods of acute and chronic exercise.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was provided by Western Institutional Review Board Study (#1271583). Institutional approval was also provided by collaborating institutions: Pennsylvania State University (STUDY00003729), SUNY Upstate Medical University (1070727), Marist College (#S18-033), Syracuse University (#17-374), Vanderbilt University (#181814), Bridgewater College (19-005), and the United States Army, Regional Health Command-Atlantic (#1510001-1). Written informed consent/assent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Experimental design

The goal of this prospective multi-center study was to refine a set of 40 saliva miRNAs with diagnostic potential for SRC17,27 by eliminating miRNAs confounded by acute or chronic exercise, which would negatively impact the accuracy of field-side miRNA measurement or post-injury comparisons to a pre-season miRNA baseline. To achieve this goal, the study employed a 3-step approach: (1) saliva miRNAs impacted by “acute exercise” were identified within 83 individuals who completed a single workout involving one of 4 sports (running, rowing, soccer, or football); (2) saliva miRNAs impacted by “chronic exercise” were identified within 106 individuals who completed a full season involving one of 5 full-contact sports (lacrosse, basketball, hockey, soccer, or mixed martial arts); and (3) the ability of saliva miRNAs not impacted by “acute exercise” or “chronic exercise” to differentiate 75 individuals with recent concussion (≤24 h post-injury) from 97 individuals without recent concussion was assessed via logistic regression analysis. Misclassification rates were compared between individuals with SRC and individuals with non-SRC as well as between individuals with recent exercise and without recent exercise.

2.3. Participants

The study included a convenience sample of 455 saliva samples from 314 individuals, aged 8–58 years. All participants were enrolled as part of a larger parent study17 at 10 institutions: Bridgewater College (n = 20), Colgate University (n = 106), the United States Army Combative School (n = 27), Marist College (n = 45), Penn State University (n = 52), New York Institute of Technology (n = 28), SUNY Upstate Medical University (n = 17), Syracuse University (n = 12), Temple University (n = 6), and Vanderbilt University (n = 1). Recruitment was performed by research staff at affiliated emergency departments, athletic training facilities, and acute care clinics. Inclusion criteria were (1) concussion within the previous 24 h (identified by licensed clinicians using the 2016 Concussion in Sport Group definition28) or (2) active participation in organized sport (defined as participation in a collegiate, semi-professional, or military-affiliated athletic event). Exclusion criteria for all participants were primary language other than English, pregnancy, periodontal disease, neurologic disorder (e.g., epilepsy), drug/alcohol dependency, respiratory infection, and orthopedic injury (sprain, contusion, or fracture within 14 days of enrollment). Participants with concussion were excluded for Glasgow Coma Score of ≤13 at the time of initial injury, penetrating head injury, symptoms attributable to underlying psychological disorder (e.g., depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), over-night hospitalization for concussion, skull fracture, or findings of intracranial bleed on imaging (if performed).

2.3.1. Group 1: Acute exercise

First, we sought to determine the acute impact of exercise on concussion-related miRNAs and assess whether exercise-induced changes in saliva miRNAs differed between athletes in contact versus non-contact sports. We assessed miRNA levels within 166 saliva samples from 83 individuals. Paired saliva samples were collected from each individual between 15 min and 60 min prior to sport participation, and again within 20 min of exercise completion. There were 51 participants in non-contact sports: 25 collegiate distance runners completing their weekly “long run” (duration of ≥55 min, covering ≥20% of weekly running distance29); 20 college students completing a graded treadmill protocol; and 6 collegiate rowers completing a high-intensity 50-min ergometer workout. There were 32 participants in contact sports: 12 semi-professional soccer players participating in a 45-min, full-contact scrimmage; and 20 collegiate football athletes completing a full-contact practice that was 120 min in duration. The number of head impacts sustained by each contact sport athlete were recorded through direct observation by research staff (4 researchers observed 4 different athletes across 5 separate practices). None of the participating athletes were diagnosed with a concussion during the practice.

2.3.2. Group 2: Chronic exercise (season-long contact sport participation)

Second, we sought to determine whether concussion-related saliva miRNAs change as a result of chronic exercise (throughout a season of contact sport participation). We assessed miRNA levels within 212 paired saliva samples from 106 athletes. Saliva was collected at the outset of the athletic season from 83 athletes involved in lacrosse, basketball, hockey, or soccer, as well as 23 U.S. Army soldiers performing mixed-martial arts training. Saliva samples were collected from each individual again at the completion of the athletic season (30–115 days after enrollment). None of the participants were diagnosed with a concussion during the course of their athletic season.

2.3.3. Group 3: SRC diagnosis

Third, we sought to employ salivary miRNAs unaffected by exertion or season-long participation in contact sports (in Groups 1 and 2) to refine a diagnostic adjunct for SRC. We assessed salivary miRNA levels within 172 saliva samples from 172 athletes. There were 75 individuals with concussion and 97 without concussion. The participants without concussion included 46 college athletes who had participated in sport ≤30 min prior to saliva collection, and 51 college athletes with no recent sport participation immediately prior to saliva collection. Concussion mechanism was self-reported as sport-related (n = 42) or non-sport-related (n = 33). Athletes with non-SRCs were included in order to determine whether a predictive model using saliva miRNAs would perform similarly for SRCs and non-SRCs.

2.4. Measures

Medical and demographic information (sex, age, race, anthropometrics, dietary restrictions, and co-morbid medical conditions) was collected from all participants via survey. Presence/absence of any previous concussion was self-reported. For athletes with acute participation in contact sports, the number of head impacts sustained during practice was recorded through 1:1 observation by research staff. Helmet-to-ground, helmet-to-helmet, and helmet-to-body impacts were counted. Saliva was collected from each participant following oral tap-water rinse, in a non-fasting state, using swabs (OraCollect RE-100; DNA Genotek, Ottawa, Canada) or expectorant kits (OraCollect P-157; DNA Genotek). Per manufacturer instructions, samples were stored at room temperature for up to 60 days prior to their shipment to the SUNY Genomic Core Facility. Samples were then incubated at 50°C and frozen at –20°C prior to RNA analysis.

2.5. Saliva RNA analysis

As we have previously reported,17,29 RNA was isolated from each saliva sample per manufacturer instructions with the miRNeasy Kit (217084; Qiagen Inc., Germantown, MD, USA). RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The TruSeq Small RNA Library Prep Kit (RS-122-2001; Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to prepare RNA libraries. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq (Nextseq500; Illumina) instrument at a sequencing depth of 10 million reads/sample. Cutadapt (https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/) was used to remove adapter sequences,30 prior to alignment with miRBase22 using Bowtie (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml). Quantification was performed via SamTools (http://www.htslib.org/) using a custom-built bio-informatics architecture.31 Aligned reads were quantile normalized. Each miRNA feature was scaled (mean-centered, divided by the feature standard deviation). Down-stream analysis focused on 40 miRNA candidates previously identified in published studies of traumatic brain injury.17,27

2.6. Statistical analysis

The acute influence of exercise on salivary levels of concussion-related miRNAs was assessed (166 samples, 83 participants) using a within-subject non-parametric two-way analysis of variance. Levels of the 40 miRNAs were the dependent factors. Exercise status (pre-/post-participation) and sport type (contact/non-contact) were the independent variables. The cumulative effect of season-long contact sport participation on miRNA levels was assessed (212 samples, 106 participants) using a within-subject non-parametric one-way analysis of variance. To explore whether the miRNAs displaying season-long changes during contact sport participation might be affected by cumulative head impacts (as opposed to cumulative fatigue, minor musculoskeletal injuries, or enhanced conditioning), we performed Spearman's rank testing to identify associations between pre-/post-practice changes in miRNA levels and the number of head impacts sustained during practice. Finally, the salivary miRNAs that demonstrated no effect of acute exercise or season-long sports participation in the previous analyses were interrogated for the ability to differentiate 75 concussed and 97 non-concussed participants via logistic regression analysis. Accuracy of each miRNA was assessed by 100-fold cross-validated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Sensitivity, specificity, positive/negative likelihood ratios, and between groups differences (on non-parametric Wilcoxon rank testing) were also determined for each miRNA. To promote translation to a sideline point-of-care device using dual-channel polymerase chain reaction (which allows quantification of 2 miRNAs in 1 well), the miRNA ratio with the highest AUC was used to develop a logistic regression model that predicted concussion status within the Metaboanalyst v4.0 biomarker toolkit.32 To assess the potential confounding effects of exercise on the predictive model, a two-proportion z test was used to compare misclassification rates of concussed individuals with SRC vs. non-SRC. Statistical analyses were performed in Metabolanalyst,32 and Benjamini–Hochberg correction was applied to all analysis of variance results. An a priori power analysis using MDAnderson Bioinformatics software (https://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/MicroarraySampleSize) determined that a sample size of 14 participants per group provided 80% power to detect a 1.5-fold difference among 40 miRNAs (per-gene α = 0.05), based on the standard variance observed in our previous miRNA datasets.12,13,25

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Participants were mostly college-aged, Caucasian males (Table 1). Few participants had anxiety (8/314; 3%), depression (14/314; 5%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (11/314; 4%), or dietary restrictions (25/314; 8%). One-quarter of the participants (78/314; 25%) had suffered a previous concussion.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| All | Acute exercise | Sports season | Sports related concussions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | SRC | Non-SRC | Exercise CTRL | CTRL | ||||

| Total | 314 | 106 | 83 | 172 | 42 | 33 | 46 | 51 |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Sex (male) | 198 (63) | 83 (78) | 47 (57) | 105 (61) | 25 (60) | 17 (52) | 38 (78)* | 27 (53) |

| Age (year) | 21 ± 6 | 23 ± 5 | 20 ± 1 | 20 ± 7 | 16 ± 6 | 21 ± 14* | 21 ± 1* | 21 ± 1* |

| Caucasian | 208 (86) | 74 (79) | 57 (69) | 114 (86) | 34 (82) | 29 (88) | 36 (78) | 48 (94) |

| African American | 27 (11) | 14 (15) | 6 (10) | 18 (14) | 4 (9) | 2 (6) | 11 (24) | 4 (8) |

| Asian | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Medical | ||||||||

| Height (in) | 68 ± 6 | 70 ± 4 | 69 ± 4 | 67 ± 7 | 63 ± 9 | 63 ± 6 | 71 ± 4* | 70 ± 4* |

| Weight (lbs) | 162 ± 41 | 171 ± 38 | 166 ± 27 | 161 ± 49 | 142 ± 53 | 138 ± 59 | 184 ± 42* | 170 ± 25* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.6 ± 8 | 24.6 ± 4 | 24.1 ± 2 | 25.1 ± 11 | 23.5 ± 5 | 23.5 ± 7 | 25.7 ± 5 | 24.2 ± 2 |

| Anxiety | 8 (3) | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| Depression | 14 (5) | 9 (13) | 0 (0) | 7 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (17)* | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| ADHD | 11 (4) | 3 (4) | 5 (6) | 4 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Oral | ||||||||

| Time of collection (h) | 9 AM ± 4 | 11 AM ± 4 | 11 AM ± 4 | 10 AM ± 4 | 1 PM ± 4 | 1 PM ± 3 | 12 PM ± 3 | 11 AM ± 4* |

| Dietary restrictions | 25 (9) | 7 (10) | 6 (7) | 11 (7) | 2 (5) | 3 (9) | 2 (4) | 4 (8) |

| Head injury details | ||||||||

| Past concussion | 78 (25) | 32 (31) | 17 (20) | 48 (28) | 9 (21) | 5 (16) | 18 (39)* | 16 (31) |

| Hits to head (n (range)) | NA | 8 (0–50) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Time from TBI to collection (h) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14 ± 8 | 16 ± 6 | NA | NA |

Notes: Date are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). Percentage reflects the percentage of respondents with a particular trait/condition, not percentage of all participants with the trait/condition. A portion (n = 47) of control participants in the sports-related concussion group were derived from the acute exercise and sports season groups, which is why the total unique participants (n = 314) is less than the group totals (n = 361) reflected in the table. Respondents were given the opportunity to select more than 1 race. Not all participants reported race.

Abbreviations: ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; BMI = body mass index; CTRL = control participant; NA = not applicable; SRC = sports-related concussion; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

p < 0.05 compared to SRC.

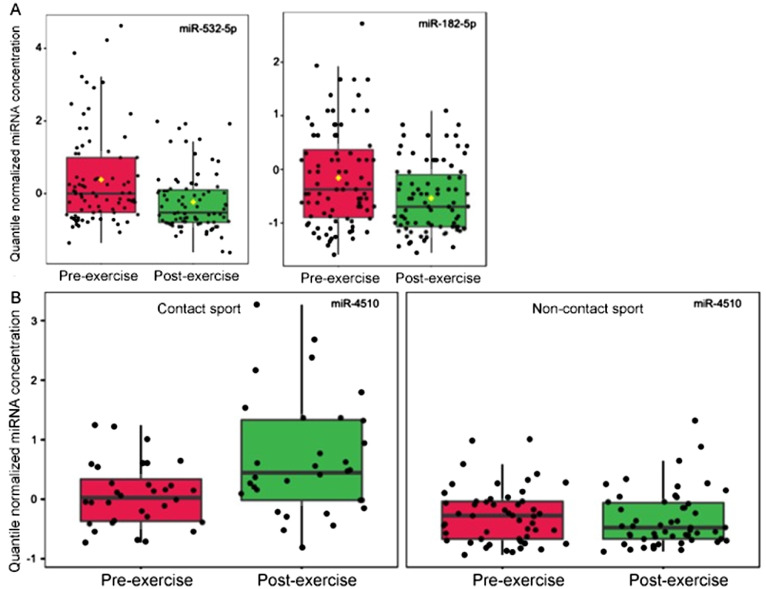

3.2. Salivary miRNAs within a single episode of acute exercise

Assessment of the 40 concussion-related miRNAs among 83 individuals immediately before/after participation in contact (n = 32) or non-contact sports (n = 51) revealed 2/40 miRNAs with an effect (adjusted p < 0.05) of exercise (Fig. 1A). Levels of both miR-532-5p and miR-182-5p decreased with exercise. Only 1 miRNA responded uniquely to contact sports (i.e., displayed an interaction effect between exercise and sport-type). Levels of miR-4510 increased only among contact sport athletes (Fig. 1B). There was no relationship between the number of observed head impacts and levels of miR-532-5p (r = 0.16, p = 0.48), miR-182-5p (r = 0.15, p = 0.50), or miR-4510 (r = 0.17, p = 0.46) among athletes involved in contact sports.

Fig. 1.

Three salivary miRNAs acutely impacted by sport participation. (A) The box plots represent quantile normalized concentrations for 2 miRNAs (miR-532-5p and miR-182-5p) with a significant change (adjusted p < 0.05) among 83 athletes from pre-exercise (red) to post-exercise (green); (B) There was 1 miRNA (miR-4510) with a significant interaction (adjusted p < 0.05) between sport type and exercise. Levels of miR-4510 increased among 32 contact sport athletes post-exercise, but not among 51 non-contact sport athletes. miRNA = micro ribonucleic acid.

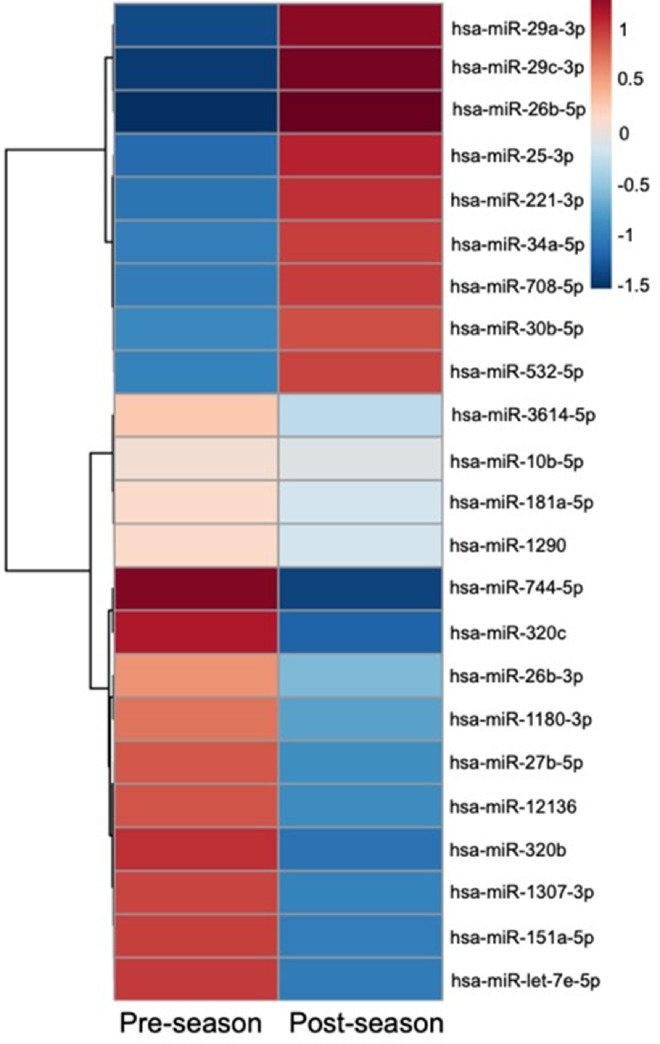

3.3. Salivary miRNAs across a season of contact sport participation

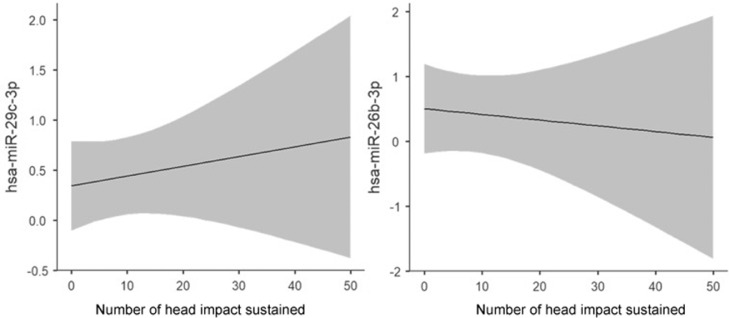

Comparison of saliva miRNA levels within 106 collegiate athletes and soldiers participating in contact sports demonstrated changes (adjusted p < 0.05) in 23/40 concussion-related miRNAs at the end of the season (Fig. 2). There were 9 miRNAs that increased and 14 miRNAs that decreased at the end of the season. One of these miRNAs (miR-532-5p) had also displayed decreased levels with acute exercise. Among 20 football athletes participating in a full-contact practice, pre/post-practice changes in 2 of the 23 miRNAs demonstrated an association (R > 0.50, p < 0.05) with the number of head impacts sustained during practice (Fig. 3). Levels of miR-29c-3p increased with the number of head impacts (R = 0.59, p = 0.006), while levels of miR-26b-3p decreased with the number of head impacts (R = –0.51, p = 0.020). Similarly, levels of miR-29c-3p also increased during contact sports season, whereas miR-26b-3p levels decreased, suggesting these season-long changes might be related to cumulative head impacts.

Fig. 2.

Twenty-three salivary miRNAs change at the end of a contact sports season. The heat map displays mean levels of 23 miRNAs that showed a significant change (adjusted p < 0.05) between pre- and post-season levels among 106 athletes and soldiers participating in contact sports. There were 14 miRNAs with decreased salivary levels (blue) at the end of the season, and 9 miRNAs with increased salivary levels (red). The miRNAs are clustered based on expression similarity using a Ward clustering algorithm with a Pearson distance metric. hsa = Homo sapiens; miRNA = micro ribonucleic acid.

Fig. 3.

Levels of 2 miRNAs are related to the number of head impacts sustained. Marginalized means plots display the relationship between the number of head impacts sustained in a single football practice and the pre-/post-practice change in normalized saliva miRNA concentration. A greater number of head impacts sustained in a single practice was associated with an increase in post-practice levels of miR-29c-3p relative to pre-practice baseline levels (R = 0.59, p = 0.006); a greater number of head impacts was also associated with a reduction in post-practice levels of miR-26b-3p relative to pre-practice baseline (R = –0.51, p = 0.020). The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. hsa = Homo sapien; miRNA = micro ribonucleic acid.

3.4. Diagnostic ability of SRC-related miRNAs

The 15/40 salivary miRNAs unaffected by acute exercise or season-long exercise were interrogated as diagnostic candidates for SRC. Ability of individual miRNAs to differentiate concussed and non-concussed participants was quantified by AUC on a logistic regression analysis (Table 2). The majority of these candidates (11/15) demonstrated a significant difference (adjusted p < 0.05) between concussed and non-concussed participants, and 6 miRNAs displayed moderate differential ability (AUC ≥ 0.70). The most accurate miRNA for differentiating concussed and non-concussed participants was miR-27a-5p (AUC = 0.78, sensitivity = 74%, specificity = 75%). A logistic regression model employing a ratio of miR-27a-5p and miR-30a-3p (logit(P) = 0.155 + 0.169 miR-27a-5p/miR-30a-3p) achieved the highest accuracy (AUC = 0.810, sensitivity = 82.4%, specificity = 73.3%) for differentiating concussion status (Fig. 4). Adding age and sex as covariates to this model did not appreciably change predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.811, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.734–0.880). There was no difference (z = 1.69, p = 0.09) in the proportion of misclassified individuals with recent exercise (29/88, 33%) vs. those without recent exercise (18/84, 21%). Similarly, there was no difference (z = 0.5, p = 0.60) in the proportion of misclassified individuals with SRC (10/42, 24%), vs. those with non-SRC (6/33, 18%).

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of 15 salivary miRNAs unaffected by acute exercise or season-long exercise.

| Name | AUC | Adjusted p value | Cut-offs | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity + specificity | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-27a-5p | 0.78 | 2.2E-07 | –0.22 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 1.49 | 2.93 | 0.35 |

| miR-1246 | 0.77 | 1.9E-01 | –0.20 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 1.44 | 3.74 | 0.48 |

| miR-30e-3p | 0.73 | 2.1E-05 | –0.23 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 1.43 | 2.35 | 0.36 |

| miR-30a-3p | 0.72 | 1.7E-05 | –0.21 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 1.39 | 2.09 | 0.39 |

| miR-151a-3p | 0.71 | 3.3E-05 | –0.18 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 1.39 | 2.11 | 0.41 |

| miR-192-5p | 0.70 | 1.7E-06 | –0.02 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 1.35 | 1.77 | 0.36 |

| miR-7-1-3p | 0.67 | 4.3E-04 | –0.05 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 1.30 | 2.13 | 0.59 |

| miR-181c-5p | 0.67 | 3.1E-04 | –0.25 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 1.31 | 1.78 | 0.48 |

| miR-30e-5p | 0.67 | 1.6E-04 | –0.14 | 0.60 | 0.73 | 1.33 | 2.24 | 0.55 |

| miR-1307-5p | 0.67 | 1.1E-05 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 1.30 | 1.69 | 0.49 |

| miR-182-5p | 0.61 | 5.3E-02 | –0.10 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 1.24 | 1.70 | 0.63 |

| miR-3074-5p | 0.61 | 2.3E-02 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.68 | 1.15 | 1.48 | 0.77 |

| miR-629-5p | 0.55 | 5.5E-01 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 1.03 |

| miR-944 | 0.52 | 8.0E-01 | –0.65 | 0.71 | 0.39 | 1.10 | 1.16 | 0.75 |

| miR-27b-3p | 0.51 | 5.6E-01 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.40 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 0.90 |

Notes: Diagnostic accuracy for each of the 15 salivary miRNAs is displayed based on AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratio of an individual logistic regression algorithm. Diagnostic cut-off for each algorithm is displayed. Adjusted p-values for each miRNA are also shown for comparing concussion and non-concussion participants on Mann–Whitney U testing.

Abbreviations: AUC = area under the curve; LR = likelihood ratio; miRNA = micro ribonucleic acid.

Fig. 4.

A single miRNA ratio differentiates concussed and non-concussed individuals. (A) A receiver operator characteristic curve displays the relative sensitivity and specificity of a logistic regression algorithm employing concentrations of miR-27a-5p and miR-30a-3p for differentiating 75 concussed individuals from 97 non-concussed individuals. The ratio achieved an AUC of 0.81 (95%CI: 0.734–0.880), with 82.4% sensitivity and 73.3% specificity; (B) Levels of miR-27a-5p/miR-30a-3p were lower among concussed individuals. Notably, both miRNAs displayed no effect of acute or chronic exercise, and they differentiated SRCs and non-SRCs with similar accuracy. 95%CI = 95% confidence interval; AUC = area under the curve; miRNA= micro ribonucleic acid; SRCs = sport-related concussions.

4. Discussion

This study identified saliva miRNAs that could potentially identify SRC without confounding effects of acute exercise or season-long training. A single miRNA ratio (measurable in 1 tube using dual-channel quantitative polymerase chain reaction) identified concussion status with an AUC of 0.810. This accuracy is similar to that of serum biomarkers.33, 34, 35, 36,18,37, 38, 39, 40 For any biological marker of SRC, it is critical to determine the impact of acute or chronic exercise.41, 42, 43 The present study defines this important relationship for saliva miRNAs.

4.1. Clinical implications

Clinicians performing sideline assessments of athletes rely primarily on subjective symptom reports, balance measures, and neurocognitive testing to identify SRC.2,44 These tools perform optimally when baseline assessments are available.45 Despite their diagnostic utility, they can be manipulated by athletes wishing to avoid removal from play.3,46 Neurocognitive testing must be administered by a trained professional,47 and the time required for test administration often prohibits sideline administration.48 Development of an objective saliva miRNA assessment for concussion could address several of these limitations. Perhaps the biggest value of salivary miRNA is rapid obtainment with minimal medical training. Previous studies have demonstrated that miR-27a and miR-30a levels may hold diagnostic utility for concussion when measured in blood or saliva.9, 10, 11,14,49 However, serum markers involve a blood draw, which requires an invasive medical procedure with potential for infection. Measurement of sensitive and specific salivary miRNAs in real time could lead to a rapid sideline test, easily deployed by athletic trainers. Such a test could prove particularly useful when assessing athletes with transient symptoms who pass sideline testing, but where suspicion of underlying head injury persists. Although miR-27a and miR-30a are found in tissues throughout the human body,50,51 both miRNAs are expressed by peripheral nerves (such as those innervating the pharynx), where they have been shown to control pathophysiologic processes relevant to concussion, such as pain modulation and cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury.52,53

4.2. Biological implications

The biological relevance of miR-27a and miR-30a to SRC pathophysiology underscores the unique role that these biomarkers may serve in SRC. Existing SRC assessments characterize subjective symptoms and functional changes that arise from brain injury. However, these measures do not detect the brain injury itself.54 Reliance on such assessments may contribute to under-recognition of brain injury.55, 56, 57 It may also hinder advances in SRC treatment, which currently focuses on addressing symptomatic manifestations, rather than underlying biological changes. Finally, reliance on symptomatic and functional changes diminishes the importance of minor head impacts that may accumulate to raise an athlete's SRC risk.58,59 Since it will be nearly impossible for diagnostic biomarkers to outperform a subjective gold standard of SRC, integration of biomarkers into SRC evaluation and treatment will likely require a major paradigm shift. For example, in the present study, 2 molecules implicated in concussion pathophysiology (miR-26b-3p and miR-29c-3p) were found to change at the end of a contact sports season and to correlate with the burden of non-concussive head impacts. Validation of this relationship in a larger, longitudinal cohort of contact sport athletes with sensitive measures of head impact burden could eventually be used to create a biological test for non-concussive head impacts that raise SRC risk.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The enrollment of athletes from a wide variety of sports, across 10 different clinical sites, enhances the generalizability of these findings. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of miRNA changes with exercise,60 and the first to examine saliva miRNA changes with both acute exercise and cumulative (season-long) sports participation. We note that the timing between exercise and saliva collection varied among participants. Participants with SRC were enrolled within 24 h of injury (and exercise) because previous research has shown that exercise can impact miRNA levels for up to 24 h.61 However, exercise controls were enrolled within 2 h of exercise. This difference in “recent exercise” definition may have impacted misclassification rates for the predictive miRNA ratio. However, we expect that such a difference would lead to over-estimation of misclassification rates, which did not differ between individuals with/without recent exercise. In addition, few miRNAs (2/40) displayed an acute effect of exercise, and these miRNAs were excluded from diagnostic consideration.

Our study design does not allow us to definitively determine whether the saliva miRNAs that change with season-long participation in contact sports are impacted by cumulative fatigue, musculoskeletal injuries, or conditioning. Our exploratory analysis suggested that 2 saliva miRNAs that changed during a contact sports season (miR-26b-3p and miR-29c-3p) were also associated with the number of head impacts in a single practice. However, larger studies utilizing more sensitive, objective measures of head impacts over a full season of contact sport are needed to confirm this finding. Use of accelerometers or video recordings may provide more accurate estimates of head impacts than the direct observation used in this study. Our analysis of season-long changes in salivary miRNAs excluded participants who suffered a concussion during the course of the season as well as participants who had orthopedic injuries at the time of saliva collection, but no data are available for intra-season injuries. Finally, the study was not powered to examine sport-specific effects on saliva miRNA levels because our goal was to identify saliva miRNAs that display consistent changes across a wide variety of sports, which may limit their utility as sideline biomarkers for SRC.

5. Conclusion

This study contributes to growing evidence regarding salivary miRNAs as potential concussion biomarkers. We identify a subset of salivary miRNAs that are impacted by acute exercise or season-long participation in contact sports. Such miRNAs may constitute poor biomarkers for SRC because they could confound sideline measurements or comparisons with pre-season baselines. The salivary miRNAs unaffected by exercise represent promising biomarker candidates for SRC. Indeed, a ratio of 2 of these miRNAs (miR-27a-5p and miR-30a-3p) differentiated individuals with concussion regardless of exercise status and displayed similar accuracy to serum biomarkers. Future investigations prospectively validating the response of these miRNAs in large populations of athletes would provide additional evidence for their clinical utility in SRC.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alexandra Confair, Molly Carney, Jessica Beiler, Katsiah Cadet, Elizabeth Packard, Jennifer Stokes (Penn State University), Kyle Kelleran (Bridgewater College), Allison Iles, Arianna Montefusco, Rhianna Ericson, Kayla Wagner (Quadrant Biosciences), Matthew Badia, and Jason Randall (Marist College) for aiding with participant enrollment and sample analysis. We thank Eric Schaefer and Vonn Walter (Penn State) for guidance on statistical modeling, Frank Middleton (SUNY Upstate) and Aakanksha Rangnekar (Quadrant Biosciences) for assistance with RNA processing and alignment, and Kevin Heffernan (Syracuse University) for article appraisal and revisions.

This project was supported by a sponsored research agreement between Quadrant Biosciences and the Penn State College of Medicine to ACL. SDH's time was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant KL2 TR002015 and Grant UL1 TR002014). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sources. Material has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. There is no objection to its presentation and/or publication. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting true views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in AR 70–25.

Authors’ contributions

SDH designed the study, oversaw sample collection, analyzed the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript; ACL and SLZ contributed to the study design; RYK, KJZ, JL, RPO, CaM, MMM, TL, MH, ChM, EF, MND, and TRC were involved in sample acquisition; GF and SDV oversaw sample processing; ZG, GF, and CN contributed to data analysis; CO, SLZ, and MND participated in the drafting of the article. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

SDH is a paid consultant and scientific advisory board member for Quadrant Biosciences. He is named as a co-inventor on intellectual property related to saliva RNA biomarkers in concussion that is patented by The Penn State College of Medicine and licensed to Quadrant Biosciences. SDV and GF are paid employees of Quadrant Biosciences. CN has equity interest in Quadrant Bioscience Inc. All the support had no involvement in the study design and writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM, Shankar V, McCrea M, Cantu RC. Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in seven us high school and collegiate sports. Inj Epidemiol. 2015;2:13. doi: 10.1186/s40621-015-0045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumba-Brown A, Yeates KO, Sarmiento K, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline on the diagnosis and management of mild traumatic brain injury among children. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins KL, Denney RL, Maerlender A. Sandbagging on the immediate post-concussion assessment and cognitive testing (impact) in a high school athlete population. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;32:259–266. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acw108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schatz P, Elbin R, Anderson MN, Savage J, Covassin T. Exploring sandbagging behaviors, effort, and perceived utility of the impact baseline assessment in college athletes. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2017;6:243. doi: 10.1037/spy0000100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrea M, Meier T, Huber D, et al. Role of advanced neuroimaging, fluid biomarkers and genetic testing in the assessment of sport-related concussion: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:919–929. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. International programme on chemical safety. Biomarkers in risk assessment: Validity and validation. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42363. [accessed 06.11.2020]

- 7.Jeter CB, Hergenroeder GW, Hylin MJ, Redell JB, Moore AN, Dash PK. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of mild traumatic brain injury/concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:657–670. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balakathiresan N, Bhomia M, Chandran R, Chavko M, McCarron RM, Maheshwari RK. microRNA let-7i is a promising serum biomarker for blast-induced traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1379–1387. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redell JB, Moore AN, Ward 3rd NH, Hergenroeder GW, Dash PK. Human traumatic brain injury alters plasma microRNA levels. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:2147–2156. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhomia M, Balakathiresan NS, Wang KK, Papa L, Maheshwari RK. A panel of serum miRNA biomarkers for the diagnosis of severe to mild traumatic brain injury in humans. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28148. doi: 10.1038/srep28148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Pietro V, Porto E, Ragusa M, et al. Salivary microRNAs: Diagnostic markers of mild traumatic brain injury in contact-sport. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:290. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JJ, Loeffert AC, Stokes J, Olympia RP, Bramley H, Hicks SD. Association of salivary microRNA changes with prolonged concussion symptoms. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaRocca D, Barns S, Hicks SD, et al. Comparison of serum and saliva miRNAs for identification and characterization of MTBI in adult mixed martial arts fighters. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicks SD, Johnson J, Carney MC, et al. Overlapping microRNA expression in saliva and cerebrospinal fluid accurately identifies pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:64–72. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahjin F, Guda RS, Schaal VL, et al. Brain-derived extracellular vesicle microRNA signatures associated with in utero and postnatal oxycodone exposure. Cells. 2020;9:21. doi: 10.3390/cells9010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prada I, Gabrielli M, Turola E, et al. Glia-to-neuron transfer of miRNAs via extracellular vesicles: A new mechanism underlying inflammation-induced synaptic alterations. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135:529–550. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1803-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hicks SD, Onks C, Kim RY, et al. Diagnosing mild traumatic brain injury using saliva RNA compared to cognitive and balance testing. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10:e197. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asken BM, Bauer RM, DeKosky ST, et al. Concussion basics III: Serum biomarker changes following sport-related concussion. Neurology. 2018;91:e2133–e2e43. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asken BM, Bauer RM, DeKosky ST, et al. Concussion biomarkers assessed in collegiate student-athletes (basics) I: Normative study. Neurology. 2018;91:e2109–e2e22. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mannix R, Levy R, Zemek R, et al. Fluid biomarkers of pediatric mild traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:2029–2044. doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domańska-Senderowska D, Laguette MJN, Jegier A, Cięszczyk P, September AV, Brzeziańska-Lasota E. Microrna profile and adaptive response to exercise training: A review. Int J Sports Med. 2019;40:227–235. doi: 10.1055/a-0824-4813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papa L, Slobounov SM, Breiter HC, et al. Elevations in microRNA biomarkers in serum are associated with measures of concussion, neurocognitive function, and subconcussive trauma over a single National Collegiate Athletic Association division I season in collegiate football players. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:1343–1351. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svingos AM, Asken BM, Bauer RM, et al. Exploratory study of sport-related concussion effects on peripheral micro-RNA expression. Brain Inj. 2019;33:1–7. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1573379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Pietro V, Yakoub KM, Scarpa U, Di Pietro C, Belli A. Microrna signature of traumatic brain injury: From the biomarker discovery to the point-of-care. Front Neurol. 2018;9:429. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks SD, Jacob P, Middleton FA, Perez O, Gagnon Z. Distance running alters peripheral microRNAs implicated in metabolism, fluid balance, and myosin regulation in a sex-specific manner. Physiol Genom. 2018;50:658–667. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00035.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konstantinidou A, Mougios V, Sidossis L. Acute exercise alters the levels of human saliva miRNAs involved in lipid metabolism. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37:584–588. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1569345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atif H, Hicks SD. Areview of microRNA biomarkers in traumatic brain injury. J Exp Neurosci. 2019;13 doi: 10.1177/1179069519832286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvořák J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:838–847. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hicks SD, Jacob P, Perez O, Baffuto M, Gagnon Z, Middleton FA. The transcriptional signature of a runner's high. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:970–978. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chong J, Wishart DS, Xia J. Using MetaboAnalyst 4.0 for comprehensive and integrative metabolomics data analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2019;68:e86. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papa L, Lewis LM, Falk JL, et al. Elevated levels of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein breakdown products in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury are associated with intracranial lesions and neurosurgical intervention. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papa L, Lewis LM, Silvestri S, et al. Serum levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase distinguish mild traumatic brain injury from trauma controls and are elevated in mild and moderate traumatic brain injury patients with intracranial lesions and neurosurgical intervention. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1335–1344. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182491e3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu X, Hildebrandt N. Rapid and multiplexed microRNA diagnostic assay using quantum dot-based Forster resonance energy transfer. ACS Nano. 2015;9:8449–8457. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papa L, Brophy GM, Welch RD, et al. Time course and diagnostic accuracy of glial and neuronal blood biomarkers GFAP and UCH-l1 in a large cohort of trauma patients with and without mild traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:551–560. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf H, Frantal S, Pajenda GS, et al. Predictive value of neuromarkers supported by a set of clinical criteria in patients with mild traumatic brain injury: S100b protein and neuron-specific enolase on trial. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:1298–1303. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS121181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geyer C, Ulrich A, Gräfe G, Stach B, Till H. Diagnostic value of S100b and neuron-specific enolase in mild pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:339–344. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.PEDS08481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giza CC, McCrea M, Huber D, et al. Assessment of blood biomarker profile after acute concussion during combative training among us military cadets: A prospective study from the NCAA and US department of defense care consortium. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCrea M, Broglio SP, McAllister TW, et al. Association of blood biomarkers with acute sport-related concussion in collegiate athletes: Findings from the NCAA and department of defense CARE consortium. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasselblatt M, Mooren FC, Von Ahsen N, et al. Serum S100β increases in marathon runners reflect extracranial release rather than glial damage. Neurology. 2004;62:1634–1636. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123092.97047.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saur L, de Senna PN, Paim MF, et al. Physical exercise increases GFAP expression and induces morphological changes in hippocampal astrocytes. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0500-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roh HT, So WY. The effects of aerobic exercise training on oxidant–antioxidant balance, neurotrophic factor levels, and blood–brain barrier function in obese and non-obese men. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patricios JS, Ardern CL, Hislop MD, et al. Implementation of the 2017 Berlin Concussion in Sport Group Consensus Statement in contact and collision sports: A joint position statement from 11 national and international sports organisations. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:635–641. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cottle JE, Hall EE, Patel K, Barnes KP, Ketcham CJ. Concussion baseline testing: Preexisting factors, symptoms, and neurocognitive performance. J Athl Train. 2017;52:77–81. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.12.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schatz P, Moser RS, Solomon GS, Ott SD, Karpf R. Prevalence of invalid computerized baseline neurocognitive test results in high school and collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2012;47:289–296. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.3.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Echemendia RJ, Herring S, Bailes J. Who should conduct and interpret the neuropsychological assessment in sports-related concussion? Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(Suppl. 1):i32. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058164. –5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moser RS, Schatz P, Neidzwski K, Ott SD. Group versus individual administration affects baseline neurocognitive test performance. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2325–2330. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taheri S, Tanriverdi F, Zararsiz G, et al. Circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers for traumatic brain injury-induced hypopituitarism. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1818–1825. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fehlmann T, Ludwig N, Backes C, Meese E, Keller A. Distribution of microRNA biomarker candidates in solid tissues and body fluids. RNA Biol. 2016;13:1084–1088. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1234658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Rie D, Abugessaisa I, Alam T, et al. An integrated expression atlas of miRNAs and their promoters in human and mouse. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:872–878. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan M, Shen L, Hou Y. Epigenetic modification of BDNF mediates neuropathic pain via miR-30a-3p/EP300 axis in CCI rats. Biosci Rep. 2020;40 doi: 10.1042/BSR20194442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang T, Wang D, Qu Y, et al. N-hydroxy-N'-(4-butyl-2-methylphenyl)-formamidine attenuates oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation-induced cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via regulation of microRNAs. J Integr Neurosci. 2020;19:303–311. doi: 10.31083/j.jin.2020.02.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asken BM. Concussion biomarkers: Deviating from the garden path. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:515–516. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray IR, Murray AD, Robson J. Sports concussion: Time for a culture change. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;2:75–77. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gourley MM, Valovich McLeod TC, Bay RC. Awareness and recognition of concussion by youth athletes and their parents. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2010;2:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corwin DJ, Arbogast KB, Haber RA, et al. Characteristics and outcomes for delayed diagnosis of concussion in pediatric patients presenting to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2020;59:795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rowson S, Duma SM. Development of the STAR evaluation system for football helmets: integrating player head impact exposure and risk of concussion. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:2130–2140. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Funk JR, Rowson S, Daniel RW, Duma SM. Validation of concussion risk curves for collegiate football players derived from HITS data. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40:79–89. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.da Silva FC, da Rosa Iop R, Andrade A, Costa VP, Gutierres Filho PJB, da Silva R. Effects of physical exercise on the expression of microRNAs: A systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;34:270–280. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mooren FC, Viereck J, Krüger K, Thum T. Circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers of aerobic exercise capacity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H557. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00711.2013. –63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.