Abstract

Lueyang black-bone chicken is a domestic breed in China. The genetic mechanism of the formation of important economic traits of this breed has not been studied systematically. Therefore, in this study, whole genome resequencing was used to systematically analyze and evaluate the genetic diversity of the black-feather and white-feather populations, and to screen and identify key genes related to phenotypes. The results of principal component analysis and population structure analysis showed that Lueyang black-feathered chickens and white-feathered chickens could be divided into 2 subgroups, and the genetic diversity of black-feathered chicken was richer than that of white-feathered chickens. Linkage disequilibrium analysis also showed that the selection intensity of black-feathered chickens was lower than for white-feathered chickens, which was mainly due to the small population size of white-feathered chickens and a certain degree of inbreeding. Fixation index (FST) analysis revealed that the candidate genes related to feather color traits were G-gamma, FA, FERM, Kelch, TGFb, Arf, FERM, and melanin synthesis-related gene tyrosinase (TYR). Based on Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment analysis, Jak-STAT, mTOR, and TGF-β signaling pathways were mainly related to melanogenesis and plume color. The findings of this study supported important information for the evaluation and protection of chicken genetic resources and help to analyze the unique genetic phenotypes such as melanin deposition and feather color of Lueyang black-bone chicken. Additionally, it could provide basic research data for the improvement and breeding of Lueyang black-bone chicken with characteristic traits.

Key words: lueyang black-bone chicken, whole genome resequencing, plumage, SNP

INTRODUCTION

The black-bone chicken originated from China with a variety of breeds such as the Jiangshan black-bone chicken, the Lueyang black-bone chicken, and the Muchuan black-bone chicken (Zhu et al., 2014). With specific characteristics of black bone and meat, black-bone chickens are different from broiler and layer chickens. In China, the black-bone chicken has been used in traditional Chinese medicine recipes for treating various diseases (Chen et al., 2006) and rehabilitating patients for thousands of years (Geng et al., 2010). The Lueyang black-bone chicken, named for the Chinese county of Lueyang, typically with 6 black parts (cockscomb, beak, skin, legs, tongue, and bone) that distinguished it from other chicken breeds. Lueyang black-bone chickens are highly prized and major income producers for farmers in the region.

Feather color distinguishes poultry breeds and is one of the important morphological characteristics, which is an economically important trait that consumers may consider to purchasing these birds. Feather blackness is one of the key traits the black-bone chicken possesses. The black feather is determined by melanin, which is synthesized by melanocytes located in the basal epidermis skin layer and transferred to keratinocytes (Cichorek et al., 2013). This process is mainly controlled by genetics. Several studies have reported that melanin synthesis was regulated by melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), dopachrome tautomerase (DCT), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1), tyrosinase (TYR), and agouti signaling protein (ASIP) genes (Jiao et al., 2004; Dorshorst et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019). These genes mainly involved in the melanogenesis pathway.

Lueyang black-bone chicken is an ancient local breed of chicken that has been domesticated over a long period of time in the unique geographical environment of Lueyang County in China. This breed has 3 types of feather color: black feather, white feather and hemp feather. Much more research concerned about Lueyang black-bone chickens with black feather because of their black traits with high economic value, whereas white feathers and hemp feathers have almost disappeared during the breeding process. Therefore, the protection of feather color diversity and investigation of the formation mechanism of Lueyang black-bone chicken is of great significance to the protection and industrial development of this breed. However, the genetic structure of the population of different feather colors has not been systematically explored, and the genetic mechanism of the formation of black feathers and white feathers in the population has not been studied.

This study was systematically analyzed and evaluated the population genetic diversity and genetic structure through the re-sequencing of the genomes of Lueyang black-feathered chickens and white-feathered chickens. Meanwhile, candidate genes and SNPs related to the black and white feather color traits of Lueyang black-bone chickens were screened out. These results provided novel genetic markers and candidate genes for the refined breeding of Lueyang black-bone chickens with different feather colors and provided fundamental data for the protection of genetic resources of Lueyang black-bone chickens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All animal experimental procedures were approved and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Shaanxi province Animal Care and Use Committee.

Sample Collection and Sequencing

A total of 20 blood samples were obtained from the wing vein of 3 months Lueyang black-bone chickens, including 10 black-feathered chickens and 10 white-feathered chickens, all of which were 5 females and 5 males. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood according to the standard phenol/chloroform method and stored at -20°C until use.

Briefly, genomic DNA library construction involved the following steps: genomic DNA shearing, purification, end-repairing, ligating adaptors, size selection, and DNA amplification. The libraries were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq X platform. Sequencing and base calling were performed using the manufacturer's protocols to generate primary read data (Li et al., 2020).

Quality Control Processing and Variant Calling

To ensure high-quality data, the raw sequencing data for all samples were filtered to remove adaptors, trim low-quality and unidentified nucleotides (Ns) at the 5 and 3 ends, trim nucleotides having an average quality score less than 30 within a window of 4 nucleotides, and removing reads containing more than 10% Ns. After a series of quality controls, High-quality reads were aligned to the chicken reference genome (Gallus gallus (assembly bGalGal1. mat. broiler. GRCg7b)) using BWA-MEM (Jung and Han, 2022). The SNP calling was performed using GATK (McKenna et al., 2010), and the high-quality SNP positions were filtered and reported using SAMtools.

Population Genetics Structure and Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

We employed smartpca implemented in the EIGENSOFT package to perform principal component analysis (PCA) analysis (Patterson et al., 2006) and visualized with R package (ggplot2). The population structure was investigated by using the supervised ADMIXTURE program (Alexander et al., 2009) via the maximum likelihood method. We predefined K, the number of genetic clusters (ranging from K = 2 to K = 5). To reduce noise due to linkage disequilibrium (LD), SNPs with high pair-wise R2 values (R2 >0.2) were pruned from the dataset using PLINK (Purcell et al., 2007). LD for 2 breeds was calculated on the basis of the correlation coefficient R2 statistics of 2 loci using PopLDdecay (Zhang et al., 2019).

Genome-Wide Selective Sweep Analysis and Gene Annotation

To define candidate regions that undergone directional selection in the Lueyang black bone chicken, we calculated the population differentiation index (FST) between black-feathered chickens and white-feathered chickens using the approach as previously described (Weir and Cockerham, 1984). We calculated the average FST value in 500 kb sliding windows with a 50 kb sliding step between 2 populations using VCFtools (v0.1.15) (Danecek et al., 2011). Finally, we performed a functional enrichment analysis of the candidate genes, using Gene Ontology categories and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways.

RESULTS

Genetic Variation in Lueyang Black-Bone Chicken

To identify genetic variations, we resequenced the genomes of 20 Lueyang black-bone chickens (Figure 1). Using the Illumina sequencing platform, all samples yielded over 723.276 G clean reads, representing approximately 36163.808 M per chicken. Q30 scores exceeded 92.38%. We identified 68,825,330 SNPs, including 4,801,421 SNPs in black-feathered chickens and 2,081,109 SNPs in white-feathered chicken. There were 1,130,594 SNPs shared between the 2 populations.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and variant statistics. (A) The geographical location of Lueyang black-bone chicken. (B) Overview of the experimental design. (C) Distribution of SNPs based on genome sequences alignment.

To better understand the distribution of SNPs, we classified them according to their context into 7 categories (Figure 1C and Supplementary Table S3). 28.71% of SNPs were found in introns. An even larger numbers of SNPs were located in intergenic regions (61.02%). Smaller numbers of SNPs were within exon (0.64% in aggregate), upstream or downstream of genes (0.012% in aggregate), upstream of genes (0.54% in aggregate).

Population Genetic Structure

To examine genome-wide relationships and divergence between Lueyang black-feathered chickens and white-feathered chickens, we performed PCA based on whole-genome polymorphic SNPs. The result showed that, 2 maximum features were obtained, namely PC1 and PC2 (Figure 2A). In the 2-dimensional space constituted by these 2 main features, there was no overlap between 2 populations, and they were separated according to the PC1, indicating obvious differentiation between the 2 populations.

Figure 2.

Population genetics and LD decay. (A) PCA plots based on the 20 chickens. (B) Genetic structure of 20 individual samples for K groups using the ADMIXTURE program. K is the number of presumed ancestral groups, which was varied in the analysis from 2 to 5. (C) Measurement of LD decay for Lueyang black-bone chickens. LD, linkage disequilibrium.

Structure analysis results were consistent with the PCA (Figure 2B). For black-feather chicken, at a low value of K (K = 2), it is clearly associated with a separate ancestor. When K = 5, we observed 4 distributed ancestral components labeled. For white-feather chicken, When K was set from 2 to 5, it was still associated with a single ancestor. In terms of the structure of the whole population, it could be obviously divided into 2 distinct groups, and there was almost no gene exchange between the 2 groups, indicating that the genetic distance between them was relatively far.

To estimate LD in black-feathered chickens and white-feathered chickens, we calculated the squared correlations for 2 loci against the genome distance R2 between pairs of SNPs. As shown in Figure 2C, black-feathered chickens attenuated faster than white-feathered chickens, indicating black-feathered chickens have relatively higher diversity and lower selection intensity.

Genome-Wide Selective Sweep Signals and Functional Analysis

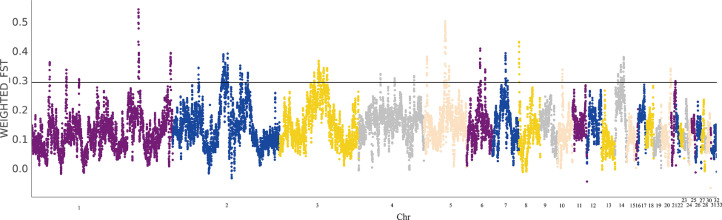

In order to better detect genome-wide selection signals related to the unique feather trait, we divided the populations into black-feather and white-feather groups. After conducting selection sweep analysis, FST test was performed to detect variation between 2 populations. Among the 2 populations, there were 10762 values distributed between 0.05 to 0.15, 6056 values between 0.15 to 0.3, and 1165 values greater than 0.3, including 10 values greater than 0.5 (Supplementary Figure S5). High FST values (FST > 0.3) were used as criteria for classifying selective sweeps (Figure 3). In total, we identified 27 windows in accordance with the parameter, and a total of 149 candidate genes were identified. TYR was identified on chromosome 4 which is a gene related to melanin synthesis. At the same time, FST >0.5 was found on chromosome 1 and chromosome 5. After gene annotation, the gene was found to be RVT_1 (ENSGALP00000071574 and ENSGALP00000065234). In addition, g-Gamma, FA, FERM, Kelch, TGFb, Arf, FERM and other genes were identified in the selected region (FST > 0.3). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis results showed that candidate genes are mainly involved in inflammatory bowel disease, hepatitis C, basal cell carcinoma, TGF-β signaling, JAK-STAT signaling pathway (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

FST distribution in the whole genome of Lueyang black-feathered and white-feathered chicken.

Figure 4.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of candidate genes under selection in Lueyang black-bone chickens. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

DISCUSSION

Lueyang black-bone chicken is mainly produced in the Heihe River Basin of Lueyang County, in Shaanxi Province. It is an excellent domestic breed formed after long-term cultivation, showing obvious advantages in genetic resources. In this research, 30 × whole genome resequencing was performed to 20 Lueyang black-bone chickens (10 black-feathered black-bone chickens and 10 white-feathered black-bone chickens), achieving a huge volume of resequencing data and high sequencing quality (Q30 > 92%). Basing on analysis, 4,801,421 SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) were detected in Lueyang black-feathered black-bone chicken group, and 2,081,109 SNPs were obtained in Lueyang white-feathered group. The proportion of SNPs in exons at mutation sites between the 2 groups was less than 1%, equal to 81,169 (0.84%) and 87,331 (0.85%) respectively. The SNPs are mainly located in the intergenic and intron regions. At present, the research of Lueyang black-bone chicken mainly focuses on breeding management technology, nutritional value analysis, resource protection and genetic diversity. The analyses of genetic diversity and genetic structure at the whole gene level and the research on the genetic mechanism of important traits have not been reported yet. This research discovered that the number of SNPs in the white-feathered group was small and the polymorphism was low. This finding is consistent with the actual situation, because most of Lueyang black-bone chickens are currently bred black-feathered group, and the breeding stock is small for white-feathered group. The groups in this study are the result of local inbreeding in the group. Genetic heterozygosity and genetic diversity are reduced in white-feathered group. Compared with Lueyang white-feathered black-bone chickens, black-feathered chickens are currently the main breeding group. The black-feathered group size is large, so it has a larger number of SNPs, and a higher genetic diversity and genetic index.

The analysis of group structure could help us gain a further understanding towards the formation process of varieties or subspecies (Li et al., 2020). Lueyang black-feathered and white-feathered chickens can be clearly divided into 2 subspecies, and the 2 groups have very slight gene flow. Such research finding is consistent with the actual breeding situation, because Lueyang black-feathered black-bone chickens and white-feathered black-bone chickens have their own economic values, so few people used the 2 groups for hybrid breeding. Therefore, it guarantees the pure breeding. When the value K increased, the Lueyang black-feathered black-bone chicken group showed differentiation and fell into the corresponding expected number of subgroups, but the Lueyang white-feathered black-bone chicken group did not undergo group differentiation with the value K increasing and existed as a unique group, showing no individual gene exchange. Zhang et al. discovered that the nucleotide diversity of black-bone chickens typically showed a decreasing trend, and speculated that the phenomenon may be due to artificial selection (Zhang et al., 2018). As a purebred breed, Lueyang white-feathered black-bone chicken has less gene exchange, which leads to a decrease in its genetic diversity and a sharp decrease in the number of genetic varieties. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the protection of the resources of white-feathered group of Lueyang black-bone chickens.

In this study, the FST value was firstly used to select the 2 groups, including Lueyang black-feathered and white-feathered black-bone chicken. Based on systematic analysis, a total of 11 chromosomes had a large genetic differentiation between the 2 groups, and further window analysis was carried out. The sites with FST values greater than 0.3 on each chromosome were displayed and functionally annotated. The results showed that 149 candidate genes were identified in 27 windows on 11 chromosomes, and the distribution on each chromosome was different.

Feather color is a very important trait in animal domestication research. In order to identify candidate genes that cause feather color differentiation in black-feathered and white-feathered groups, we compared the whole genome resequencing data of 10 individuals from each of the 2 groups. Subsequently, we identified that Jak-STAT, mTOR, and TGF-β pathways were mainly related to melanogenesis and plume color. This finding is consistent with the researching results of YU et al. reported, demonstrating that TGF-β pathway played an important role in the formation of feather melanin based on transcriptome analysis of Muchuan black-bone chicken hair follicles (Yu et al., 2018). Meanwhile, Kanakachari et al., also showed that Jak-STAT, mTOR, and TGF-β signaling pathways were closely related to feather color traits(Kanakachari et al., 2022).

In addition, TYR is annotated in the selected region of chromosome 4, which is encoding the rate-limiting enzyme that regulates melanin formation (Poelstra et al., 2014). Cho et al. proved that white-feathered chickens have the recessive white TYR allelic genes, thus showing the white-feathered phenotype due to the insertion of retroviral sequences into intron 4 to inhibit the transcription of TYR exon 5 (Cho et al., 2021). Imes et al. discovered that the expression level of TYR in Datong black yak was significantly higher than that in Tianzhu white yak (Imes et al., 2006). They also discovered that TYR mutation would cause some black-fur animals to grow white furs. Therefore, a lot of research has been conducted on black feather and white feather, all of which demonstrate that TYR is closely related to feather color formation. These researches concluded that TYR mutation may cause the feather and fur color differentiation in various animals. This conclusion coincides with the findings of the present study. The gene accession number of TYR annotated in the research is ENSGALP00000046568, ENSGALP00000049491, ENSGALP00000068800, ENSGALP00000073653, ENSGALP00000068819, ENSGALP00000037901, ENSGALP00000069809 and ENSGALP00000056246. Meanwhile, regions with FST greater than 0.5 have been found on both chromosome 1 and 5. According to the result of gene annotation, the gene is RVT_1 (ENSGALP00000071574 and ENSGALP00000065234). Furthermore, we identified G-gamma, FA, FERM, Kelch, TGFb, Arf, FERM and other genes that may be related to feather color traits in the selected regions. These genes are possibly related to the formation of feather color between Lueyang black-feathered and white-feathered black-bone chicken. These genes are needed to verify by further.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the whole genome resequencing data, the research found that Lueyang black-feathered black-bone chicken and white-feathered black-bone chicken could be obviously divided into 2 groups, and the genetic diversity of white-feathered group was lower than that of black-feathered group, and there was very little gene exchange between the 2 groups. According to the result of further enrichment analysis, Jak-STAT, mTOR, and TGF-β signaling pathways related to feather color were discovered and annotated to TYR, a type of gene related to melanin formation. We also identified RVT_1, G-gamma, FA and other potential functional genes that may be related to feather color.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Scientific Research Project of Shaanxi University of Technology (SXC-2101) and Key Scientific Research Project of Education Department of Shaanxi Province (20JY006).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Ling Wang, Zhen Xue; Formal analysis: Ge Yang, Yingmin Tian; Funding acquisition: Tao Zhang; Project administration: Hongzhao Lu, Wenxian Zeng; Resources: Yufei Yang, Pan Li; Software: Shanshan Wang; Writing - original draft: Zhen Xue; Writing - review & editing: Ling Wang.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.102721.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Alexander D.H., Novembre J., Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhou H., Liu Y.B., Wang J.F., Li H., Ung C.Y., Han L.Y., Cao Z.W., Chen Y.Z. Database of traditional Chinese medicine and its application to studies of mechanism and to prescription validation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;149:1092–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E., Kim M., Manjula P., Cho S.H., Seo D., Lee S.S., Lee J.H. A retroviral insertion in the tyrosinase (TYR) gene is associated with the recessive white plumage color in the Yeonsan Ogye chicken. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2021;63:751–758. doi: 10.5187/jast.2021.e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichorek M., Wachulska M., Stasiewicz A., Tymińska A. Skin melanocytes: biology and development. Postepy. Dermatol. Alergol. 2013;30:30–41. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2013.33376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P., Auton A., Abecasis G., Albers C.A., Banks E., DePristo M.A., Handsaker R.E., Lunter G., Marth G.T., Sherry S.T., McVean G., Durbin R., and 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorshorst B., Okimoto R., Ashwell C. Genomic regions associated with dermal hyperpigmentation, polydactyly and other morphological traits in the Silkie chicken. J. Hered. 2010;101:339–350. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng S.S., Li H.Z., Wu X.K., Dang J.M., Tong H., Zhao C.Y., Liu Y., Cai Y.Q. Effect of Wujijing Oral Liquid on menstrual disturbance of women. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:649–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imes D.L., Geary L.A., Grahn R.A., Lyons L.A. Albinism in the domestic cat (Felis catus) is associated with a tyrosinase (TYR) mutation. Anim. Genet. 2006;37:175–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Z., Mollaaghababa R., Pavan W.J., Antonellis A., Green E.D., Hornyak T.J. Direct interaction of Sox10 with the promoter of murine Dopachrome Tautomerase (Dct) and synergistic activation of Dct expression with Mitf. Pigment. Cell. Res. 2004;17:352–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y., Han D. BWA-MEME: BWA-MEM emulated with a machine learning approach. Bioinformatics. 2022;38:2404–2413. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanakachari M., Ashwini R., Chatterjee R.N., Bhattacharya T.K. Embryonic transcriptome unravels mechanisms and pathways underlying embryonic development with respect to muscle growth, egg production, and plumage formation in native and broiler chickens. Front. Genet. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.990849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Sun G., Zhang M., Cao Y., Zhang C., Fu Y., Li F., Li G., Jiang R., Han R., Li Z., Wang Y., Tian Y., Liu X., Li W., Kang X. Breeding history and candidate genes responsible for black skin of Xichuan black-bone chicken. BMC Genomics. 2020;21:511. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-06900-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., DePristo M.A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N., Price A.L., Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLos Genet. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelstra J.W., Vijay N., Bossu C.M., Lantz H., Ryll B., Müller I., Baglione V., Unneberg P., Wikelski M., Grabherr M.G., Wolf J.B.W. The genomic landscape underlying phenotypic integrity in the face of gene flow in crows. Science. 2014;344:1410–1414. doi: 10.1126/science.1253226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir B.S., Cockerham C.C. Estimating f-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution. 1984;38:1358–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.W., Ran J.S., Yu C.L., Qiu M.H., Zhang Z.R., Du H.R., Li Q.Y., Xiong X., Song X.Y., Xia B., Hu C., Liu Y.P., Jiang X.S. Polymorphism in MC1R, TYR and ASIP genes in different colored feather chickens. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:203. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1710-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Wang G., Liao J. Association of a novel SNP in the ASIP gene with skin color in black-bone chicken. Anim. Genet. 2019;50:283–286. doi: 10.1111/age.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Wang G., Liao J., Tang M., Sun W. Transcriptome Profile analysis of mechanisms of black and white plumage determination in black-bone chicken. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;46:2373–2384. doi: 10.1159/000489644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Dong S.S., Xu J.Y., He W.M., Yang T.L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1786–1788. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Liu H., Yang L.K., Yin Y.J., Lu H.Z., Wang L. The complete mitochondrial genome and molecular phylogeny of Lueyang black-bone chicken. Br. Poult. Sci. 2018;59:618–623. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2018.1514581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.D., Wang H.H., Zhang C.X., Li Q.H., Chen X.H., Lou L.F. Analysis of skin color change and related gene expression after crossing of Dongxiang black chicken and ISA layer. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015;14:11551–11561. doi: 10.4238/2015.September.28.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W.Q., Li H.F., Wang J.Y., Shu J.T., Zhu C.H., Song W.T., Song C., Ji G.G., Liu H.X. Molecular genetic diversity and maternal origin of Chinese black-bone chicken breeds. Genet. Mol. Res. 2014;13:3275–3282. doi: 10.4238/2014.April.29.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.