Abstract

The need to protect and sustain environmental resources for future generation remains sacrosanct in global sustainability agenda. This study was aimed at exploring the interplay between environmental conservation and spirituality from a multicultural perspective. While studies on “spirituality” have monumentally gained global attention, a growing number of evidence underscore the critical role of spiritual resources available for ensuring environmental stewardship. In this present study, attempt was made to respond to some critical questions: Is there any significant association between spirituality and environmental responsibility? What is the impact of spiritual leadership on environmental conservation? What key messages do spiritual leaders need to prioritize to encourage environmental conservation? And what are some of the spirituality-related predictors of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts among the respondents? To determine this nexus between spirituality and environmentalism, a cross-sectional study design was adopted. Primary data were collected by means of a validated and adapted instrument from various literature searches. Data collected from a sample of 1,438 respondents were entered on Excel spreadsheet and eventually exported on SPSS version 21 for further analysis. Every segment of the instrument used yielded a Cronbach’s alpha reliability test result of no less than 0.70. Descriptive statistics and ordinal logistics regression analysis were employed. The findings revealed that majority of respondents expressed a high level of spirituality (p value < 0.05). Majority (70%) of the respondents believe that everyone has a duty of care toward nature. More than two-third (> 60.0%) would be more inclined to observing environmental conservative measures if their spiritual leaders would continue to give exemplary teachings on environmental conservation. While a few indicators of spirituality yielded direct correlation with the willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts, most of the selected indicators reflect willingness. Some of these (predictors) include how often respondents pray, meditate, and fast; caring about people, animals, and the planet; being just happy to be alive; etc. In conclusion, this study reasoned that spirituality could indeed serve as a foundation for environmental conservation campaigns and could reinforce pro-environmental behaviors.

Keywords: Environmental responsibility, Spirituality, Environmental conservation, Faith tradition, Environmental behavior

Introduction

Threats to the sustainability of nature have evolved over years to transcend beyond local attention into a subject of acute global concern. And as such, in what seems to be an unprecedented fashion, the discipline of environmental conservation has received greater attention both as a measure to forestall degradation and as a stimulus to promote sustainability (Kumar, 2017; Pirri, 2019). This has therefore necessitated the pluralism of approaches to facilitate environmental conservation, multilateral strategies to promoting conservation, and indeed galvanization of global efforts across stakeholders and institutions in every society (Egri, 1997; Kaiser et al., 1999; Kumar, 2017).

To this end, spirituality and religious beliefs have been considerably ushered into the discussions on global sustainability (Granberg-Michaelson, 1992). This, in part, underpins the rationale for convening the international conference of religious leaders in Vatican City in March 2018 to discuss a wide variety of issues on sustainable development goals (Centeno et al., 2018). The concept of spirituality must have gained global attention based on two standpoints.

First, as part of humanity, there is the existence of numerous religions with a constantly evolving beliefs and value systems which continues to influence people’s beliefs on almost every existential and sometimes volatile issue. On the latter standpoint, a plethora of evidence have earlier linked several spiritual practices (e.g., praying, meditation, worship, yoga, etc.) to improved health and wellness (Puchalski, 2001; Corey, 2006; MHF, 2006), while a growing number of scholarly papers on spirituality have taken a cursory look at the interplay of spirituality and environmental stewardships (PRC, 2015; Hope & Jones, 2014; Sachdeva, 2016). Taken together, spirituality and/or religion is often perceived as critical source of strength for many people during distress. Hence, it is often considered a resource for finding meaning in life and could be instrumental in promoting good, healthy, protective behaviors, especially in this era where the planet is threatened by very serious environmental distress.

It cannot be overemphasized that a significant proportion of the environmental degradations that confront human existence are the resultant effects of human activities. And to an appreciable measure, human activities are animated and stimulated by a diversity of factors, among which is religion or spiritual beliefs. In the past two decades, the earth has witnessed unprecedented magnitude of environmental degradation, due to the global warming, climate change effects, and the incessant pollution of the environment. These anthropogenic activities (causing poor air quality and undrinkable water) exacerbated by the increased global population have a far-reaching consequences on the ecosystem (Farinmade et al., 2019; Kaiser et al., 1999; Makengo, 2020; Swim et al., 2011).

To recreate sustainable healthy living space for humanity, efforts would be required to provide clean air, natural resources, and a non-toxic environment. This so-called human effort is what scientists literarily termed environmental conservation. The ability to sustain this conservation effort for future generation is termed environmental sustainability. Arora (2018) defined environmental sustainability as the act of meeting today’s needs but ensuring that future generations will have enough natural resources to maintain a quality of life equal to if not better than that of current generations. With uncontrolled resource depletion, humanity would face a global food crisis, energy crisis, and an increase in greenhouse gas emissions that will lead to a global warming crisis. A plethora of conservation measures have been globally acclaimed in offsetting ecological carbon footprint. Some of these measures include afforestation or planting trees (provides clean air and traps carbon), green lifestyle (reduce, reuse, and recycle materials, cut down waste generation), saving water and energy resources, responsible waste disposal (avoid sending chemicals into waterways), and avoiding the consumption of fossil fuels by using renewable energy alternatives. Furthermore, the quest for the re-creation of a sustainable healthy environment would be plausible if drivers of pro-environmental behaviors are well understood and could be sustained. The term “pro-environmental behavior” simply denotes behavior that consciously seeks to minimize the negative impact of one’s actions on the natural and built world (e.g., saving and minimizing resource and energy consumption, use of non-toxic substances, reducing waste production) (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002).

The interwovenness of human’s spirituality, activities, and their impacts on the environment underscores the need to gauge the nexus between the conservation of the environment and spiritual inclination of humans (Kumar, 2017). In other words, this research appreciates the fact that spirituality may influence human behaviors and activities and hence critically evaluate how the conservation of the environment can be promoted or inhibited by the spirituality of humans (Pirri, 2019). Moreover, the promotion of environmental conservation requires the integration of behavior and attitudes that engender conservation into the cognition and culture of human beings. Thus, spirituality as an influencer of man’s conducts may therefore become significant in molding conservation-inclined behaviors (Ayre, 2008).

Furthermore, religious institutions, as harbinger of spirituality, plays an important role in acculturation. In this wise, how the institution of religion and spirituality influences the conservation of the environment through her doctrines and more directly through religious rites, events, etc., is worthy of consideration (Granberg-Michaelson, 1992; Kumar, 2017). Against this backdrop, this present study seeks to offer a critical, engaged perspective on how exactly spiritual beliefs or choices influence environmental behaviors and how spirituality can be creatively harnessed to fuel attitudes that entrench environmental sustainability but carefully navigating through the two dominant divergent views: The source of spirituality is either religion or nature. More so, other fascinating and interconnecting questions on spirituality–environment dogma, specifically dovetailed on “How exactly does a belief in God or the supernatural make people more or less likely to conserve the components of the environment?” and “what will the outlook be if spiritual leaders and religious groups offer inimitable core teachings on environmental conservation?”. This study will offer environmental educators a feel for some of the broader research findings which have informed current environmental education theory and practice.

On the whole, this study sought to provide answers to some pertinent questions. Firstly, what is the mean level of spirituality among the respondents? Secondly, what is the level of interaction between spirituality and environmental responsibility? Thirdly, what are some of the positive spiritually inclined attitudes toward environmental responsibility? The study also queried what impact spiritual leadership have on environmental conservation, as well as some of the approaches or key messages that spiritual leaders deploy to teach and encourage environmental conservation. Furthermore, it demanded to find out, “to what extent were the respondents willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts? Finally, what were the spirituality-related predictors of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts? Hence, the main hypothesis posited for this work was, “there is no statistically significant association between spirituality and environmental responsibility.”

Literature review

What is spirituality?

The meaning of spirituality has evolved over time across creed and culture and has gained so much significance leaving this concept with no widely agreed definition. The term was first used within early Christianity era to refer to a life oriented toward the Holy Spirit. Driver et al. (1996) define spirituality as the interaction and relationship with something other and greater than oneself with a search for greater meaning. Taylor (2001) also submitted that spirituality can be linked to a perception of nature as a “symbolic center,” itself to be sacred. Waaijman (2002) described spirituality as a religious process of re-formation which aims to incline the ideal purpose of humanity by its connection to that which is sacred, the transcendent: who controls the universe and the destiny of humans. Verghese (2008) described it as the ways in which people fulfill what they hold to be the purpose of their lives, a search for the meaning of life, and a sense of connectedness to the universe. Spirituality was also defined as an innate capacity through which people experience transcendence and may extend to lived practices and values (McClintock et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the term “Religion” which is often used interchangeably with “spirituality” is an organized system of beliefs, behaviors, rituals, and ceremonies designed to facilitate closeness to the transcendent, (God) and to foster an understanding of one’s relationship and responsibility to others in living together in a community (Koenig, 2008; Koenig et al., 2012; Omoyajowo, 2001). Earlier studies also suggest that spirituality may not mean the same as religion (Koenig, 2008; Roof, 1993) or could even represent two divergent concepts (Schnell, 2012). Scholars generally agree that spirituality and religion represent highly overlapping constructs and hence, for the most part, spirituality is closely related to the supernatural, to the mystical, and to organized religion (Hill & Paragament, 2003; Koenig, 2008; Koenig et al., 2012; Pirri, 2019).

Environmental conservation behavior and policy need

It is believed that behavior can contribute to achieving organizational and environmental sustainability strategy, and it is on this premise that the protagonists of the voluntary environmental behavior (VEB) are canvassing for mainstreaming the role of managers and leaders of organizations in the promotion of desired social and environmental intentions for sustainable practices (Biswas et al., 2022). From the perspective of energy consumption, this idea arguably fits well into the pro-environmental behavior (PEB) campaign that encourages followers or employees’ values, especially altruistic values that spur their PEB, through planned corporate social responsibility (CSR) and green organizational practices (Xu et al., 2022). Hence, green transformational leadership and green absorptive capacity have been correlated within the context of internal and external environmental orientation approaches (Ozgul, 2022). The statement suggests that there is a growing understanding of the importance of cultural, spiritual, and ethical dimensions in conservation efforts. The statement implies that it is not enough to focus solely on scientific or economic considerations in conservation, but that a more holistic approach is needed that incorporates the cultural, spiritual, and ethical beliefs and practices of communities (Infield & Mugisha, 2010).

Spirituality practices that promote environmental consciousness and development

Spirituality describes a much broader understanding of an individual’s connection with the transcendent aspects of life. Dimensions of Spirituality mentioned in literatures were specifically: love of others (sacred reality and unifying interconnectedness to self-compassion and forgiveness); altruism, as a commitment beyond the self with care and service; gratitude as interpersonal interaction that is perceived as beneficial and that reminds us that our power is limited (McCullough & Tsang, 2004) and contemplative practice (such as meditation, prayer, yoga, or qigong); as well as encouraging meeting together during religious social events life (McClintock et al., 2016). These pro-social behaviors have many consequences that buffer stress and lead to human support when support is needed during difficult times.

Religion, on the other hand, promotes human virtues such as honesty, forgiveness, gratefulness, patience, and dependability, which help to maintain and enhance social relationships. Religion and spirituality play a dominant role in our world today with almost every important discussion referencing and reflecting the concept of spirituality in unfathomable ways: economic development (Kolade et al., 2019; Qayyum et al., 2020), improved quality of life (Counted et al., 2018), improved job satisfaction (Akbari & Hossaini, 2018), mental health care (Koenig, 2008; Verghese, 2008), and profoundly touching the discourse on environmental protection (Csutora & Zsóka, 2014; Jenkins & Chapple, 2011; Schultz et al., 2000; Taylor, 2008).

Scholars have attempted to rationalize the relationship between human and nature in general, particularly spirituality and environmental responsibility with special recognition of Ana Karina Yepes Gomez’s contribution (2009–2010) which echoes spiritual ecofeminism as a tool that can be instrumental in changing individual behaviors to promote change in society—based on an environmental ethics. Additionally, the contribution of Groen (2013), within the context of disenchantment and malaise within modern Western society, examined the growing interests of adult education for spirituality and the environment and argued that attention should be directed to responses and programs of environmental adult education located in a humanistic orientation of learning. Gabriel (2018) expounded that religion is a powerful driver of individual and collective change given its pronounced influence on the worldview, lifestyle, and commitment to humanity. He outlined how indigenous religions and traditions around the world understand and contribute to sustainable development.

Holistic view of the religious dimensions of environmentalism

Various scholars acknowledged the inclination of faith-based institutions and environmental conservation efforts describing the religious dimensions of environmentalism regarded as the dark green Religion approach with the goal of improving our understanding of eco-religious worldviews among environmentally engaged actors and their impact on transitions to sustainability (Grésillon & Sajaloli, 2015; Koehrsen, 2018; Taylor, 2008). The growing global attention about climate change and other environmental campaigns gave birth to several faith-based green movements (Clements et al., 2014), for instance, green Christians, formally launched in 1982 with the goal of sharing knowledge and green insights to affiliated members about ways to save the planet through committed actions, prayer, showing love to others, and a transformation to a green lifestyle (Green Christian, 2021).

It is not impossible to think that people’s spirituality, engaging, or showing commitment in religious activities may have an impact (negative or positive) on the environment. Violence inspired by religious intolerance is global and has the propensity to affect humanity. Bloodsheds, installation of bombs and missiles, burning of carbons, massive deforestation, and pollution of streams and poisoning of livestock, all of which mostly happen during religious violent crisis in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, contribute substantially to the building block of our ecological crisis, which greatly impedes sustainable development (Rabie, 2016).

On the other hand, Clements et al. (2014) opined that religion generally has a negative or insignificant effect on environmental concerns, when measured by acceptance of domination beliefs and biblical literalism, while religious behavior produces no clear trend. Hand and Van Liere (1984) found that while environmental concern is lower among conservative Protestants, it is rather higher among liberal Protestants. Bloch (1998), in a study of a group of people who consider themselves spiritual, found that 82% of those surveyed show concern for environmental issues. Schultz et al. (2000) found strong associations between beliefs in biblical literalism and anthropocentric bases for environmental concerns among undergraduates in various countries. Djupe and Hunt (2009) found that clergy religious communication is overwhelmingly and positively correlated with environmental sentiment and that there is a positive correlation between environmental sentiment and religious communication, although negative correlations are observed (particularly between biblical literalism and environmental protection attitudes).

An empirical study that explored the links between a values-driven life and ecological impact showed that religious people also seem to be characterized by a reduced level of ecological footprint. However, traditional religious thinking, “my way” spiritualism, and green value-based atheism are associated with an increased level of subjective well-being, while materialism is thought to be associated with a high level of ecological footprint and a low level of subjective well-being (Csutora & Zsóka, 2014). Interestingly, a similar study that was cross-examining spirituality with environmental issues in a predominantly Roman Catholic European Union country where church attendance is declining found that though self-rated spirituality and socioeconomic determinants are positively and significantly associated with environmental engagement, but not with church attendance (Briguglio et al., 2020).

Theoretical framework and models for pro-environmentalism

Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) described different models on pro-environmental behaviors, viz. The “rationalists’ model” assumed that educating people about environmental issues would automatically result in more pro-environmental behavior. However, the “theory of reasoned action” propounded by Ajzen & Fishbein (1980) explains that the ultimate determinants of any behavior (e.g., environmental behaviors) are the behavioral beliefs concerning its consequences and normative beliefs concerning the prescriptions of others. Models on altruism, empathy, and pro-social behavior reasoned that person with a strong selfish and competitive orientation are less likely to act ecologically, while people who have satisfied their personal needs are more likely to act ecologically because they have more resources (time, money, energy) to maintain sustainable behavioral patterns, less personal, social, and pro-environmental issues, hence lending credence to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Some other similar models hypothesized that to act pro-environmentally, individuals must focus beyond themselves and be concerned about the community at large (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). This last model particularly inclines with the values of spirituality.

Justification for the study

There is dearth of information on how spirituality or religious beliefs and values might influence perspectives on: (a) climate change and (b) willingness to engage in environmental conservation measures especially in Africa. In this study, hinged on information available in literatures, we proposed a scale that measures spirituality within modern day perspective. Also, we assessed people’s general attitudes to environmental issues within the context of spirituality and assessing, more generally, the extent to which people hold eco-centric (nature-centered) or anthropocentric (human-centered) values.

Materials and methods

Study areas

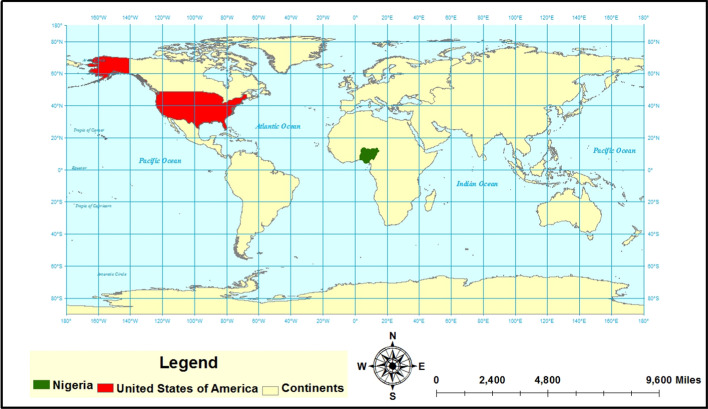

This study was practically conducted in Nigeria and the USA. Nigeria is one of the Africa’s largest economies with a population of 200,963,599, while the USA with a population of about 328.2 million people (World Bank, 2019) is a leading world power. Demographically, Nigeria is a multinational state inhabited by more than 250 ethnic groups speaking about 500 distinct indigenous languages, majorly dominated by three renown tribes (Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo) with English being their official language, and has a fairly equal distribution of Christian and Islamic faith adherents. The USA is a North American country ranked as the third world’s most populous with high socioeconomic performance and constitutes majorly Christians (65% of the total adult population) and those with no formal religion (26% of the total population) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study area map with specifications (Nigeria and USA)

Research design

A descriptive research design was utilized to explore the nexus between spirituality and environmental responsibility. A mix of different data collection and data analysis techniques was adopted to acquire and analyze relevant information while ensuring minimum bias and achieving optimal accuracy in the data collection process. The design uniquely allows for an accurate statistical evaluation of opinions and perspectives based on facts and figures to prompt decision making. Different question sets were employed to evaluate two major variables: spirituality and environmental responsibility. Research instrument used was a questionnaire which was validated by three experts who were multidisciplinary researchers and statisticians. Individual’s behavior and perceptions as it relates to “how people’s belief system influences the choices they make toward being environmentally responsible” was measured on a Likert scale. This research design was considered effective based on the desideratum that respondents might totally or partially agree or disagree with sets of given statements that represent the variables of interest being addressed. The questionnaire consists of 32 demographic, spiritual, and environmental-related items, but four psychosocial measurement instruments were particularly employed to evaluate human spirituality based on literature reviews, especially those reflected in Corey (2006) and suggestions from peers. The questionnaire was critically examined in terms of language, clarity, and content in line with research objectives; research tool was found useful and relevant by reviewers.

Data collection

Research data were collected in a unique fashion. It was basically collected with the aid of a questionnaire which was available in hard copy print and online format. The questionnaire available in hard copy print was administered through face-to-face (drop and collect method) and telephone interview in study locations. Online questionnaire was designed with the aid of Google form in the exact replica of the hard copy format. This novel data collection strategy was helpful in the collection of large amounts of data from participants in a short time frame of two months (July–August 2020). The online questionnaire was quite feasible and effective in collecting data from people in far distances based on the premise that a significant proportion of the global populations are digitally literate and connected.

Online questionnaire survey link was administered through email, websites, and social media (specifically Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram) and particularly online discussion platforms (specifically ResearchGate, Reddit, and Quora), and potential survey participants were invited to take part in the survey while considering quality measures pointed in Regmi et al. (2016). Two computer scientists were employed to review the online survey for a user-friendly design and layout. Participation in the survey was designed to be voluntary, and privacy and confidentiality were ensured. A brief instruction on how to fill the instrument, ethical consent, eligibility criteria, and research correspondent’s contact email and phone number(s) was provided on the first page to guarantee for ethical considerations and safeguards before participants proceeded with the survey. We considered respondents who were 18 years and above fit for this study and put in place quality assurance measures to circumvent the chance of multiple enrolments or possible adulterations, through the collection of respondents’ emails. Data obtained through questionnaires were properly collated, coded, and rechecked for quality assurance on Excel sheet before embarking on statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

The raw data collated on excel spread sheet were exported onto IBM SPSS version 21 software. The 1,438 completed instruments were subjected to a thorough process of data cleaning and recoding. When the options of responses to the main sections that were framed in a five points Likert scale were subjected to Cronbach’s alpha reliability test, all yielded at least 0.7 (good reliability index). There were recoding and reverse recoding to ensure that higher mean values indicated positive environmental attitudes ranging from 0 which reflects never or strongly disagree to 4 which indicates always or strongly agree in the case of positively framed items (statements). In the case of negatively framed items, the responses were reversely recoded. For internal reliability checks, responses to items that were related were summed and averaged to obtain single measures for thematic areas. All variables were presented as mean and standard deviation and or simple frequency counts and percentages. Ordinal logistic regression (OLR) was used to determine “spirituality” predictors of respondents’ willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts. Findings were considered significant at 0.05 alpha level (p value < 0.05).

Results

The data analyzed showed that out of the 1438 participants in this study, male respondents were in majority (738) which is equivalent to 51.3%, the rest being females (Table 1). More than half of them (59.8%) were aged 25 and above, and whereas about a quarter (25.1%) of them were married, an overwhelming majority (74.2%) were single. Most (78.4%) of them indicated belonging to the Christian religious faith, and the bulk (76.6%) of them had an educational attainment of at least a college bachelor’s degree. It is also remarkable that 79.2% of them were of either black or African and Nigerian American racial extraction. There were more (37.6%) unemployed respondents than employed (35.3%) and self-employed (27.1%). And almost half (48.0%) of the respondents earned within the range of 100.0–2099.9 US$.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

| S/N | Variables/categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gender (n = 1438) | ||

| Female | 700 | 48.7 | |

| Male | 738 | 51.3 | |

| 2 | Age group (n = 1438) | ||

| < 25.0 | 578 | 40.2 | |

| 25.0–34.0 | 628 | 43.7 | |

| 35.0 + | 232 | 16.1 | |

| 3 | Marital status (n = 1438) | ||

| Married | 361 | 25.1 | |

| Separated/divorced/widow, etc. | 10 | 0.7 | |

| Single | 1067 | 74.2 | |

| 4 | Religion (n = 1438) | ||

| Christianity | 1128 | 78.4 | |

| Islam | 245 | 17.0 | |

| Others | 65 | 4.5 | |

| 5 | Highest education attained (n = 1438) | ||

| High school | 171 | 11.9 | |

| Pre-bachelor | 165 | 11.5 | |

| Bachelors or equivalent | 687 | 47.8 | |

| Masters | 324 | 22.5 | |

| PhD | 91 | 6.3 | |

| 6 | Race (n = 1438) | ||

| Black or African and Nigerian Americans | 1139 | 79.2 | |

| Nigerian Africans | 43 | 3.0 | |

| Other Africans | 180 | 12.5 | |

| Whites | 44 | 3.1 | |

| Others | 32 | 2.2 | |

| 7 | Employment status (n = 1438) | ||

| Employed | 508 | 35.3 | |

| Self-employed | 389 | 27.1 | |

| Unemployed | 541 | 37.6 | |

| 8 | Average monthly wage/stipend in US dollars (n = 825) | ||

| < 100.0 | 270 | 32.7 | |

| 100.0–2099.9 | 396 | 48.0 | |

| 2100.0–4099.9 | 40 | 4.8 | |

| 4100.0 + | 119 | 14.4 |

The mean score for “How often do you pray, meditate and fast?” being a key index variable for level of spirituality was good (2.99 ± 0.96) for the entire sample in which a remarkable proportion of the respondents either indicated very often (592, 41.2%) or always (482, 33.5%) (Table 2). Among the other eight variables used to measure the level of spirituality of the respondents, seven had a mean value of at least 3 ± SD, each having above 80.0% of the respondents affirming agreement or strong agreement with positive statements on spirituality. Conversely, about 70.0% of the respondents expressed disagreement, strong disagreement, or indecision on the statement “I feel there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak,” thereby resulting in the lowest mean score of 2.08 ± 1.23.

Table 2.

Respondents’ level of spirituality

| Spirituality variable | Always n (%) | Very Often n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Rarely n (%) | Never n (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you pray, meditate, and fast? (Q10) | 482 (33.5) | 592 (41.2) | 266 (18.5) | 63 (4.4) | 35 (2.4) | 2.99 ± 0.96 |

| How true are the following statements about yourself? (Q11, Q36) | Strongly agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Undecided n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly Disagree n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I really care about people, animals, and the planet | 754 (52.4) | 605 (42.1) | 62 (4.3) | 6 (0.4) | 11 (0.8) | 3.45 ± 0.67 |

| I find joy in helping others | 929 (64.6) | 493 (34.3) | 15 (1.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3.63 ± 0.51 |

| I enjoy companionship as much as being alone | 569 (39.6) | 718 (49.9) | 97 (6.8) | 41 (2.9) | 13 (.9) | 3.24 ± 0.77 |

| I am just happy to be alive | 856 (59.5) | 528 (36.7) | 45 (3.1) | 8 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 3.55 ± 0.59 |

| I always try to think positive thoughts even during difficult situations | 729 (50.7) | 619 (43.0) | 72 (5.0) | 16 (1.1) | 2 (0.1) | 3.43 ± 0.66 |

| I often follow my gut instinct | 530 (36.9) | 712 (49.5) | 160 (11.1) | 24 (1.7) | 12 (0.8) | 3.20 ± 0.76 |

| I find it easy to forgive people who hurts me | 470 (32.7) | 710 (49.4) | 144 (10.0) | 92 (6.4) | 22 (1.5) | 3.05 ± 0.91 |

| I feel there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crisis including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. In other words, “GOD may help us to overcome the environmental crises” | 183 (12.7) | 378 (26.3) | 462 (32.1) | 197 (13.7) | 218 (15.2) | 2.08 ± 1.23 |

Reliability statistics: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.731, scale: always–never (4–0), strongly agree–strongly disagree (4–0)

On the level of interaction between spirituality and environmental responsibility, study participants generally expressed disagreement with seven out of the eighteen spirituality attitude variables (Table 3). The seven items include: “The practice of my religion or faith tradition could possibly disturb others in the environment”: (1.57 ± 1.42) where 48.2% disagreed, 19.9% undecided. With regard to the statement, “I often engage in spiritual rites involving open-space burning, poaching, animal slaughtering, exhuming and discharge of waste into the environment-at least one” (1.01 ± 1.27), 66.9% of the respondents disagreed while 14.8% of them expressed neutrality; “Natural or human-induced environmental imbalances such as earthquakes, storms, war, pandemic outbreak (Ebola, COVID-19 etc.) threatens my spiritual well-being” (1.82 ± 1.32) assertion attracted the disagreement of 39.2% participants while 26.6% of them maintained neutrality. “My personal views, lifestyles and the choices I made vis-à-vis saving water, energy and minimizing waste is shaped by my spiritual consciousness of life after-death” (1.86 ± 1.28) where 38.9% disagreed and 26.3% were undecided. “I regard the forest and life beneath the sea as evil” (1.03 ± 1.26) where 66.8% disagreed and 16.4% opted to remain neutral. “Keeping protected areas (such as national parks, wilderness areas, community conserved areas, and nature reserves) contradicts my faith” (1.03 ± 1.24) where 65.2% disagreed and 16.9% remained neutral. “Obeisance to spiritual doctrines or rites supersedes public safety measures during war and pandemic outbreaks such as COVID-19” (1.59 ± 1.21) where 44.2% disagreed and 31.8% were neutral. On the other hand, the top three positive spiritually inclined attitude variables toward environmental responsibility as expressed by about 70.0% of the respondents include: “Everyone has a duty of care toward nature” (2.94 ± 1.15); “Doing my best to save humanity from environmental distress is significant for my spiritual uprightness (2.53 ± 1.11); and “I understood what climate change is all about and I think it is real” (2.89 ± 1.11). Others with a mean score of at least 2.50 include: “It is the will of God or the supernatural that humans should ultimately exploit nature for their needs” (2.50 ± 1.29,” “Protecting the environment is a form of worship” (2.51 ± 1.15), and “I feel the way some people in my community treat nature is unfair” (2.51 ± 1.20).

Table 3.

Level of interaction between spirituality and environmental responsibility

| Attitude Variables (Q12–23) | Strongly Agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Undecided n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly disagree n (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The practice of my religion or faith tradition could possibly disturb others in the environment | 140 (9.7) | 319 (22.2) | 286 (19.9) | 164 (11.4) | 529 (36.8) | 1.57 ± 1.42 |

| I often engage in spiritual rites involving open-space burning, poaching, animal slaughtering, exhuming and discharge of waste into the environment (at least one) | 50 (3.5) | 213 (14.8) | 213 (14.8) | 162 (11.3) | 800 (55.6) | 1.01 ± 1.27 |

| Natural or human-induced environmental imbalances such as earthquakes, storms, war, pandemic outbreak (Ebola, COVID-Strongly Agree9, etc.) threatens my spiritual well-being | 160 (11.1) | 332 (23.1) | 383 (26.6) | 220 (15.3) | 343 (23.9) | 1.82 ± 1.32 |

| My personal views, lifestyles, and the choices I made vis-à-vis saving water, energy and minimizing waste is shaped by my spiritual consciousness of after-life | 142 (9.9) | 359 (25.0) | 378 (26.3) | 254 (17.7) | 305 (21.2) | 1.86 ± 1.28 |

| Everyone has a duty of care toward nature | 568 (39.5) | 490 (34.1) | 224 (15.6) | 61 (4.2) | 95 (6.6) | 2.94 ± 1.15 |

| It is the will of God or the supernatural that humans should ultimately exploit nature for their needs | 353 (24.5) | 489 (34.0) | 292 (20.3) | 124 (8.6) | 180 (12.5) | 2.50 ± 1.29 |

| Protecting the environment is a form of worship | 292 (20.3) | 509 (35.4) | 410 (28.5) | 114 (7.9) | 113 (7.9) | 2.51 ± 1.15 |

| I have heard and/or seen people polluting the environment under the guise of observing spiritual rites | 323 (22.5) | 464 (32.3) | 350 (24.3) | 146 (10.2) | 155 (10.8) | 2.45 ± 1.24 |

| I feel the way some people in my community treat nature is unfair | 323 (22.5) | 493 (34.3) | 359 (25.0) | 129 (9.0) | 134 (9.3) | 2.51 ± 1.20 |

| I often experience a fearless freedom that lights up the way I interact in the environment | 178 (12.4) | 544 (37.8) | 508 (35.3) | 110 (7.6) | 98 (6.8) | 2.41 ± 1.03 |

| I often experience an inner peace whenever I made efforts toward saving water, energy, and other natural resources | 251 (17.5) | 511 (35.5) | 434 (30.2) | 146 (10.2) | 96 (6.7) | 2.46 ± 1.10 |

| Spiritual leaders of my faith tradition are aware of the essence of saving water, energy and keeping safety of the environment | 225 (15.6) | 485 (33.7) | 451 (31.4) | 162 (11.3) | 115 (8.0) | 2.37 ± 1.12 |

| Perception Variables (Q27–Q31, 37) | ||||||

| Spiritual intervention has the potential to resolve environmental crisis or bring about relief to the outbreak of pandemic diseases like COVID-19 | 313 (21.8) | 455 (31.6) | 359 (25.0) | 150 (10.4) | 161 (11.2) | 2.42 ± 1.25 |

| Doing my best to save humanity from environmental distress is significant for my spiritual uprightness | 273 (19.0) | 547 (38.0) | 385 (26.8) | 137 (9.5) | 96 (6.7) | 2.53 ± 1.11 |

| I understood what climate change is about and I think it is real | 507 (35.3) | 501 (34.8) | 252 (17.5) | 116 (8.1) | 62 (4.3) | 2.89 ± 1.11 |

| I regard the forest and life beneath the sea as evil | 70 (4.9) | 171 (11.9) | 236 (16.4) | 214 (14.9) | 747 (51.9) | 1.03 ± 1.26 |

| Keeping protected areas (such as national parks, wilderness areas, community conserved areas, nature reserves and so on) contradicts my faith | 38 (2.6) | 219 (15.2) | 243 (16.9) | 193 (13.4) | 745 (51.8) | 1.03 ± 1.24 |

| Obeisance to spiritual doctrines or rites supersedes public safety measures during war and pandemic outbreak such as COVID-19 | 81 (5.6) | 263 (18.3) | 458 (31.8) | 258 (17.9) | 378 (26.3) | 1.59 ± 1.21 |

Reliability statistics: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.772, strongly agree–strongly disagree (4–0)

Respondents expressed their views on the impact of spiritual leadership on environmental conservation using the options of “No, Not sure, and Yes” (Table 4). An appreciable proportion of the respondents either said, “No (25.1%) or “Not sure” (37.0%) to the statement: “Do your spiritual leaders teach and encourage people on the essence of conserving nature?” and of these proportion, 69.3% were willing to take environmental conservative measures more seriously if their spiritual leaders give teachings on the subject (Table 5).

Table 4.

Impact of spiritual leadership on environmental conservation

| Items | No n (%) | Not sure n (%) | Yes n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does your spiritual leader(s) teach and encourage people on the essence of conserving nature? (n = 1438) | 361 (25.1) | 532 (37.0) | 545 (37.9) |

| If “No or Not sure” was answered above, would you be willing to take environmental conservative measures more seriously if your spiritual leaders give teachings on the subject? (n = 893) | 98 (11.0) | 176 (19.7) | 619 (69.3) |

Table 5.

Ways spiritual leaders teach and encourage environmental conservation (n = 1438)

| Items | Frequency | Percentage | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turn off lights and appliances when not in use | 954 | 66.3 | 1st |

| Donation of unused or obsolete possessions to people in need | 946 | 65.8 | 2nd |

| Planting trees around our homes | 938 | 65.2 | 3rd |

| Proper recycling and disposal of harmful chemicals | 883 | 61.4 | 4th |

| Keeping gardens without the use of harmful chemicals | 795 | 55.3 | 5th |

| Incorporating inimitable core messages about saving our planet earth into spiritual teachings may help awaken genuine concerns for environmental sustainability | 766 | 53.3 | 6th |

| Avoid unnecessary travels and expenses if your job offers flexibility | 759 | 52.8 | 7th |

| Purchase energy-efficient appliances such as LED TV, LED monitors, LED bulbs | 744 | 51.7 | 8th |

| Saving water via rainwater catchment or gray-water recycling system | 735 | 51.1 | 8th |

| Periodic maintenance of emission control systems of vehicles and other mechanical devices | 734 | 51 | 9th |

| Use of electric vehicles, fuel cells, and hydrogen-driven cars rather than fossil fuels | 670 | 46.6 | 10th |

| None | 240 | 16.7 | 11th |

Most of the respondents indicated that spiritual leaders teach and encourage Environmental Conservation in several ways. The most indicated ways include: “Turn off lights and appliances when not in use” (66.3%); “Donation of unused or obsolete possessions to people in need” (65.8%); “Planting trees around our homes” (65.2%); and “Proper recycling and disposal of harmful chemicals” (61.4%). The next most indicated ways include: “Keeping gardens without the use of harmful chemicals” (55.3%); “Incorporating inimitable core messages about saving our planet earth into spiritual teachings may help awaken genuine concerns for environmental sustainability” (53.3%); “Avoid unnecessary travels and expenses if your job offers flexibility” (52.8); “Purchase energy-efficient appliances such as LED TV, LED monitors, LED bulbs” (51.7%); “Saving water via rainwater catchment or gray-water recycling system” (51.1%); and “Periodic maintenance of emission control systems of vehicles and other mechanical devices” (51.0%). The least indicated way was, “Use of electric vehicles, fuel cells, and hydrogen-driven cars rather than fossil fuels” (46.6%). Only 16.7% of respondents admitted “None” for ways their spiritual leaders promote environmental conservation.

Regarding willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts (Table 6), the most highly rated by 62.6% of respondents was “I am willing to take environmental conservative measures more serious if our spiritual leaders give spiritual teachings on the subject” (2.70 ± 1.01). This was followed by “I am willing to raise awareness about saving the planet earth during our religious meetings” (2.51 ± 1.08) which were expressed by 54.1% of respondents. The least indicated by (49.6%) respondents were “I am willing to sponsor environmental stewardship programs through any possible means” (2.41 ± 1.03).

Table 6.

Willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts

| Variable (Q33–Q35) | Strongly agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Undecided n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly disagree n (%) | Mean SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am willing to raise awareness about saving the planet earth during our religious meetings | 273 (19.0) | 505 (35.1) | 444 (30.9) | 130 (9.0) | 86 (6.0) | 2.51 ± 1.08 |

| I am willing to sponsor environmental stewardship programs through any possible means | 199 (13.8) | 515 (35.8) | 501 (34.8) | 139 (9.7) | 84 (5.8) | 2.41 ± 1.03 |

| I am willing to take environmental conservative measures more seriously if our spiritual leaders give spiritual teachings on the subject | 282 (19.6) | 619 (43.0) | 389 (27.0) | 82 (5.7) | 66 (4.6) | 2.70 ± 1.01 |

Reliability statistics: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.753, strongly agree–strongly disagree (4–0)

For the evaluation of the nexus between respondents’ level of spirituality and willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts, ordinal logistic regression analysis was tested (Table 7). The predictors of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts were determined to include how often respondents pray, meditate and fast; caring about people, animals, and the planet; being just happy to be alive; finding it easy to forgive people who hurts; and feeling that there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Compared to respondents who pray, meditate, and fast always, those who never do so at all were less likely (OR = 0.357, Est. = − 1.030, p value = 0.001) to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts, while those who pray, meditate, and fast sometimes have 1.522 times odds of engaging in global environmental conservation efforts. Respondents who were undecided on caring about people, animals, and the planet were less likely (OR = 0.386, p value = 0.002) to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts, compared to those who always do. Additionally, respondents who “agree” that they were “just happy to be alive” had lesser odds (OR = 0.740, p value = 0.027) of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts than those who “strongly agree” that they were “just happy to be alive.” Ironically, respondents who expressed strong disagreement with the statement that “I find it easy to forgive people who hurts me” were 4.043 times more likely to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts than those who indicated “strongly agree” (p value = 0.001). Similarly, all respondents who tended to disagree with “I feel there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak” were significantly (p value = 0.000) less likely to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts than those who expressed strong agreement.

Table 7.

Ordinal logistic regression (OLR) of respondents’ level of spirituality variables on their willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts

| Predictor variables | Odd Ratio (OR) = Exp (Est) | Estimate (Est) | p-value | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| How often do you pray, meditate, and fast? (Q10) | |||||

| Never | 0.357 | − 1.030 | .001 | − 1.651 | − .409 |

| Rarely | 0.311 | − 1.168 | .000 | − 1.654 | − .681 |

| Sometimes | 1.522 | − .420 | .003 | − .696 | − .144 |

| Very Often | 0.653 | − .426 | .000 | − .650 | − .202 |

| Always | Ref. | ||||

| I really care about people, animals, and the planet | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 1.231 | .208 | .752 | − 1.079 | 1.495 |

| Disagree | 0.357 | − 1.030 | .170 | − 2.500 | .440 |

| Undecided | 0.386 | − .951 | .002 | − 1.564 | − .337 |

| Agree | 0.785 | − .242 | .079 | − .512 | .028 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I find joy in helping others | |||||

| Disagree | 0.534 | − .628 | .732 | − 4.223 | 2.968 |

| Undecided | 1.415 | .347 | .546 | − .781 | 1.475 |

| Agree | 1.066 | .064 | .660 | − .223 | .352 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I enjoy companionship as much as being alone | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 0.673 | − .396 | .488 | − 1.513 | .722 |

| Disagree | 0.891 | − .115 | .706 | − .712 | .482 |

| Undecided | 1.126 | .119 | .616 | − .345 | .583 |

| Agree | 1.168 | .155 | .222 | − .094 | .403 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I am just happy to be alive | |||||

| Strongly disagree | Ref. | ||||

| Disagree | 0.691 | − .369 | .576 | − 1.661 | .924 |

| Undecided | 1.078 | .075 | .826 | − .595 | .746 |

| Agree | 0.740 | − .301 | .027 | − .567 | − .035 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I always try to think positive thoughts even during difficult situations | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 0.227 | − 1.484 | .270 | − 4.120 | 1.152 |

| Disagree | 0.416 | − .878 | .098 | − 1.919 | .163 |

| Undecided | 0.600 | − .510 | .071 | − 1.063 | .043 |

| Agree | 0.776 | − .254 | .062 | − .521 | .013 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I often follow my gut instinct | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 0.499 | − .695 | .204 | − 1.768 | .378 |

| Disagree | 0.988 | − .012 | .977 | − .847 | .823 |

| Undecided | 0.760 | − .275 | .142 | − .641 | .092 |

| Agree | 0.829 | − .187 | .158 | − .447 | .073 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I find it easy to forgive people who hurts me | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 4.043 | 1.397 | .001 | .540 | 2.254 |

| Disagree | 1.584 | .460 | .046 | .007 | .913 |

| Undecided | 1.674 | .515 | .009 | .129 | .900 |

| Agree | 1.287 | .252 | .052 | − .002 | .506 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

| I feel there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID -19 pandemic outbreak | |||||

| Strongly disagree | 0.203 | − 1.596 | .000 | − 1.978 | − 1.214 |

| Disagree | 0.139 | − 1.972 | .000 | − 2.360 | − 1.585 |

| Undecided | 0.174 | − 1.751 | .000 | − 2.090 | − 1.412 |

| Agree | 0.353 | − 1.040 | .000 | − 1.380 | − .699 |

| Strongly agree | Ref. | ||||

The bolded P-values indicate statistically significant findings/observations on those rows

Discussion

Apart from cross-examining whether participants sampled could comprehensively represent the study population, the analysis of sociodemographic information is critical on two major standpoints: First, it helps to understand whether identity is causing an individual to do a specific thing and the latter to understand whether something is causing an individual to adopt a certain identity (Abdelal et al., 2009). It was clear that this study had a fair gender distribution with an almost equivalent male/female ratio, while vast majority (over 70%) were black or African, single, and having at least a bachelor’s degree and a religious identity as well as an age tilt to most (59.8%) within the age bracket of 25 years and above (Table 1). The import of this outcome is that people who are educated and that have such religious leaning are expected to have a better understanding about environmental issues in the context of spirituality (Copeland, 2018). More so, education is known to possess a high tendency for changing beliefs and unfavorable behaviors which may be required to drive the consciousness toward knowledge and to pursue the utmost goals of environmental sustainability. Earlier studies have found a positive association between religious involvement with female gender, aging, and African-American ethnicity (Krause, 2004; Levin & Chatters, 1998; Moreira-Almeida et al., 2010).

Religious values toward the environment are diverse, but our scale of spirituality was simply central to investigations of the essence of human nature. High level of spirituality was generally observed among respondents (Table 2). With a mean spirituality measure of at least 3 ± SD, and with above 80.0% of the respondents affirming different levels of agreement with positive statements on spirituality; the bulk of the respondents in this study can be considered to have demonstrated some appreciable level of spirituality.

For the most part, the all-encompassing elements of spirituality as pinpointed by various scholars which include praying, meditation, charity giving, showing compassion to others and gratitude to life, guidance, forgiveness, and thinking positive thoughts even during difficult situations (Goleman et al., 2008; Moberg, 2010) were used as our index variables and were all observed among respondents. Individuals or people that exhibit these traits or characters toward the environment may be considered spiritual based on our study’s unbridled objectivity rather than based on religious beliefs or sentiments, and rituals or commitment in religious activities only. Nevertheless, it is pertinent to note that about 70.0% of the respondents in this study also expressed various degrees of disagreement with the assertion that “I feel there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak” and thereby suggesting some form of a disconnect between spirituality and certain perceptions of environmental crises.

To execute one of the main thrusts of this paper, there was an attempt to explore the level of interaction between “Spirituality” and “Environmental responsibility” (Table 3). To do so, attitude and perception in this regard is significant and can help give a better outlook of issues. As regards the assessment of the respondents’ religious practices or rites that could have harmful consequences on the environment, most respondents expressed disagreement as indicated by lower mean values. This was so even where some of their religious ideals were to be violated. For example, they disagreed with “Obeisance to spiritual doctrines or rites supersedes public safety measures during war and pandemic outbreak such as COVID-19” (1.59 ± 1.21), even though they literally considered their religious activities or faith tradition as undisruptive to the environment. In a more similar fashion, majority of respondents disagreed that they were engaged in religious “…rituals that involves open-space burning, poaching, animal slaughtering, exhuming and discharge of waste into the environment” even though a few (3.5–14.8%) agreed. And although the foregoing findings might appear to paint a seemingly straightforward pro-environmental attitude most likely arising from spirituality or religiosity, “results of the empirical studies question the existence of direct relationships between religion and environmental concern, attitudes, and behavior” (Boersema et al., 2008; Chuvieco et al., 2016; Vonk, 2008).

Furthermore, about 70% of the respondents agreed with other statements that connote positive environmental attitudes and responsibility—that everyone has a duty of care toward nature (2.94 ± 1.15) and protecting the environment is a true form of worship (2.51 ± 1.15). More than half of them admitted having heard and or seen people polluting the environment under the guise of observing spiritual rites (2.45 ± 1.24), and they feel the way some people in their neighborhood treat nature is unfair (2.51 ± 1.20). All these invariably points to a high environmental responsibility index among these study participants who have also demonstrated high religiosity. The intention for posing questions in this way was to understand if there is a direct impact of individuals’ religion on environment. Skirbekk et al. (2020) opined those nations whose inhabitants are less religious tend to use more resources and produce more emissions but also with remarkably high levels of climate change adaptive capacity. Religion is an important form of spirituality which is considered to play a pivotal role toward influencing many aspects of lifestyle that affects the environment (Boersema et al., 2008). These areas may include consumption patterns, use of natural resources, childbearing decisions, and willingness to take actions to abate environmental degradation. Chuvieco et al. (2016) argued that environmental performance of countries in all religious traditions showed a strong dependence from other controlling factors, particularly the human development index and the per capita income.

It is noteworthy that vast majority of respondents gave an outstanding positive view on the essence of protecting nature from potential environmental degradation; assenting to the premise that “everyone has a duty of care toward nature,” aligns with a previous work which found that 81% of all adults, including strong majorities of all major religious traditions, favored “stronger laws and regulations to protect the environment,” while 14% opposed them (PRC, 2015). Majority of our respondents cited that “protecting the environment is a true form of worship,” thus, aligns their pro-environmental behavior with their spiritual consciousness. Nonetheless, majority believed that it is the will of God or the supernatural that humans should explore nature for their needs. However, many respondents in this study claimed they often experience an inner peace whenever they made efforts toward minimizing waste generation, saving water, energy, and other natural resources but also believed that spiritual leaders of their faith tradition were aware of the essence of saving water, energy, and other natural resources and ensuring safety of the environment. A previous work found 81% of all adults, including good majorities of all major religious traditions, favored “stronger laws and regulations to protect the environment,” while 14% opposed them (PRC, 2015).

Most respondents popularly gave a contrary opinion when asked whether “natural or human-induced environmental disruptions (e.g., earthquake, pandemic/COVID-19) influence their spiritual well-being. However, they perceived those spiritual interventions (Praying, fasting and meditation) have the potential to bring a relief to vulnerable populations, victims during crisis and further added that doing their possible best to save humanity from environmental distress is significant for their spiritual well-being (Stuart et al., 1989). More than 70% (with 35.3% strongly agree and 34.8% agree) understood what climate change entails and believed its impact are real. Religious beliefs may influence the way some people think about environment (PRC, 2015).

Based on the desideratum that spiritual leaders can influence environmental behavior of people in their religious groups, respondents were asked “Do your spiritual leaders teach and encourage people on the essence of conserving nature”; 37.9% agreed, 37% were not sure, and 25% disagreed on the subject. However, it becomes clear that some spiritual leaders teach and encourage their religious affiliates on the essence of conserving nature while others do not (Krempl, 2014). This assertion agrees with a previous work which cited that 47% of those who attend worship services at least once or twice a month said their clergy speak out on the environment; few adults described religion’s influence as most important in shaping their thinking on environmental protection (PRC, 2015). Furthermore, respondents whose “spiritual leaders do not teach and encourage people on the essence of nature’s conservation” and “those that were not sure about the subject” were further interviewed on whether they would be willing to take environmental conservative measures more seriously if their spiritual leaders would give more elaborate teachings on the subject; vast majority (69.3%) showed more willingness.

There are several environmental conservation measures globally recognized and proven to help reduce carbon footprint and reduce its impact. The measures could be achieved at individual or at public levels. Respondents popularly mentioned planting trees around homes, saving energy via turning off lights and appliances when not in use, proper recycling and responsible disposal of harmful chemicals, donation of unused or obsolete possessions to others in need among others as some of the ways spiritual leaders teaches and encourage environmental conservation (Table 5). This claim further underscores the significance and great potential religious leaders must spark reform and revolution in environmentalism (Copeland, 2018). Majority of respondents in this study were willing to raise awareness about saving planets and sponsor or support environmental stewardship program through possible means and are willing to take environmental conservation measures more serious if spiritual leaders play a leadership role on the subject.

From times past, religious thinking and environmental stewardship have been consistently receiving attention, drawing on the leadership role of humanitarian society to bridge the gap. Willingness to engage in global environmental efforts is flagged as a positive mental attitude that may entrench environmental sustainability (Krempl, 2014). Scientific research on environmental sustainability is rapidly expanding human knowledge of its vastness and its intricately interacting parts, pro-environmental behavior, lifestyle, perceptions, processes, and influences within which the subject of “spirituality” is considered important.

An ordinal regression analysis revealed that in this study five key predictors of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts were identified. These include how often respondents pray, meditate, and fast; caring about people, animals and the planet; being just happy to be alive; finding it easy to forgive people who hurts; and feeling that there is a supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Compared to respondents who pray, meditate, and fast always, those who never do so at all were less likely (OR = 0.357, p value = 0 0.001) to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts. This association has been corroborated by several studies that suggest the existence of a strong relationship between prayers and/or other spiritual devotions and the environment as well as health (Davis, 2018; WHO, 1998). Respondents who were undecided on caring about people, animals, and the planet were less likely (OR = 0.386, p value = 0.002) to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts, compared to those who always do. This finding tends to elucidate a tendency in people who were indecisive to be more likely to demonstrate unwillingness to engage in global conservation efforts.

Furthermore, based on this study, agreeing to be “just happy to be alive” yielded lesser odds (OR = 0.740, p value = 0.027) of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts than strongly agreeing to be “just happy to be alive.” Again, this further buttresses another fact that contentment being positive or satisfied with life is a significant determinant of willingness to engage in global conservation efforts (Davis, 2018). In another breath, it was rather paradoxical for respondents’ who expressed difficulty to forgive people who hurts them, to be about four times more likely to be willing to engage in global environmental conservation efforts than those who would easily forgive (p value = 0.001). This might not be unconnected with the fact that several studies have indicated that based on differences in methodologies employed and the choice of indicators, the results of studies investigating relationship between spirituality and environmental stewardship are by far not direct, but rather intricate and complex (Boersema et al., 2008; Briguglio et al., 2020; Vonk, 2008). And in fact, it has been admitted that other factors than spirituality or religious beliefs could be exerting more explanatory power in determining pro-environmental and conservation attitudes (Chuvieco et al., 2016).

In a similar fashion, where respondents who disagreed with “… supernatural influence over all environmental crises including flooding, volcanoes, and particularly the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak” significantly (p value = 0.000) exhibited less likelihood of willingness to engage in global environmental conservation efforts, it goes further to substantiate the fact that, if properly harnessed, spirituality can be leveraged upon in environmental conservation efforts (Copeland, 2018). Although Jenkins and Chapple (2011) have observed that the few empirical studies on the relationship between religious beliefs and environmental engagement yielded mixed results, there is no denying the fact that even in more atheist China; Zeng et al. (2020) have shown that study participants “with a religious identity are more willing to engage in public pro-environmental behavior than those without a religious identity.”

Conclusion and outlook

Interestingly, findings do not only reflect a positive relationship on how a belief in God or the supernatural could make people more likely to conserve the components of the environment but also observed that spiritual leaders have so much influence on the choices that their affiliates make toward saving water, energy, and other environmental resources. Precisely, over 60.0% were willing to take environmental conservative measures more seriously if their spiritual leaders gave teachings on the subject while vast majority of respondents held the belief that “protecting the environment is a true form of worship.” This study opines that spiritual beliefs and values should be viewed as a potential resource in environmental conservation discourse simply because of its significant influence on changing people’s unhealthy environmental behaviors which may collectively serve as a “fulcrum” for environmental sustainability on global scale. Identifying effective ways to communicate environmental issues and risks within faith traditions, and encouraging inter-faith and religious–nonreligious collaboration, will be important for addressing future global environmental challenges.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all our participants and survey administrators for their selfless contribution to this research.

Funding

This research was funded by Koozakar Consulting Atlanta (grant no. KO348401). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agency. The funding agency had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available with Mela Danjin (please email meladanjin@gmail.com) upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Andreas May and Mohamed Rabie: Retired Professor

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Koleayo Omoyajowo, Email: ask4koleayo@outlook.com.

Mela Danjin, Email: meladannjin@gmail.com.

Kolawole Omoyajowo, Email: ko46@illinois.edu.

Oluwaseun Odipe, Email: oodipe@unimed.edu.ng.

Benjamin Mwadi, Email: benjaminmwadi@yahoo.com.

Andreas May, Email: may_devonian@yahoo.es.

Amos Ogunyebi, Email: logunyebi@unilag.edu.ng.

Mohamed Rabie, Email: professorrabie@yahoo.com.

References

- Abdelal R, Herrera YM, Johnston AI, McDermott R. Measuring identity: A guide for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari M, Hossaini SM. The relationship of spiritual health with quality of life, mental health, and burnout: The mediating role of emotional regulation. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;12(1):22–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora NK. Environmental Sustainability—Necessary for survival. Environmental Sustainability. 2018;1:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s42398-018-0013-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayre, C. W. (2008). An approach to ecological mission in and through the Christian Community in Australia: Beyond apathy to committed action (Doctoral dissertation, University of Queensland).

- Azjen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-El R, García-Muñoz T, Neuman S, Tobol Y. The evolution of secularization: Cultural transmission, religion and fertility: Theory, simulations and evidence. Journal of Population Economics. 2013;26(3):1129–1174. doi: 10.1007/s00148-011-0401-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barker E. The church without and the God within: Religiosity and/or spirituality. In: Jerolimov D, Zrinščak S, Borowik I, editors. Religion and patterns of social transformation. Zagreb: Institute for Social Research; 2004. pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bastaire J. Pour un Christ vert. Salvator; 2009. p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SR, Uddin MA, Bhattacharjee S, Dey M, Rana T. Ecocentric leadership and voluntary environmental behavior for promoting sustainability strategy: The role of psychological green climate. Business Strategy and the Environment. 2022;31(4):1705–1718. doi: 10.1002/bse.2978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch JP. Alternative spirituality and environmentalism. Review of Religious Research. 1998;40(1):55–73. doi: 10.2307/3512459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boersema J, Blowers A, Martin A. The Religion-Environment Connection. Environmental Sciences. 2008;5(4):217–221. doi: 10.1080/15693430802542257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branas-Garza P, Garcia-Munoz T, Neuman S. Determinants of disaffiliation: An international study. Religion. 2013;4(1):166–185. doi: 10.3390/rel4010166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio, M., Garcia-Munoz, T., & Neuman S. (2020). Environmental engagement, religion and spirituality in the context of secularization. In IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Discussion Paper Series, No. 13946 (pp. 1-26).

- Centeno C, Sitte T, de Lima L, Alsirafy S, Bruera E, Callaway M, Foley K, Luyirika E, Mosoiu D, Pettus K, Christina Puchalski MR, Rajagopal JY, Garralda E, Rhee JY, Comoretto N. White paper for global palliative care advocacy: Recommendations from a PAL-LIFE expert advisory group of the pontifical academy for life, Vatican City. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018;21(10):1389–1397. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuvieco E, Burgui M, Gallego-Álvarez I. Impacts of religious beliefs on environmental indicators. Worldviews. 2016;20(3):251–271. doi: 10.1163/15685357-02003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JM, McCright AM, Xiao C. An examination of the 'Greening of Christianity' thesis among Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2014;53(2):373–391. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, R. (2018). Christianity Can Be Good for the Environment –Local religious leaders have the power to spark reform. The Brink—Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2018/christianity-can-be-good-for-the-environment/ Accessed on 15 June 2021.

- Corey G. Integrating spirituality in counseling practice. VISTA Online. 2006;25:117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Counted V, Possamai A, Meade T. Relational spirituality and quality of life 2007 to 2017: An integrative research review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0895-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csutora M, Zsóka A. May spirituality lead to reduced ecological footprint? Conceptual framework and empirical analysis. World Review of Entrepreneurship Management and Sustainable Development. 2014;10(1):88–105. doi: 10.1504/WREMSD.2014.058056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. T. 2018. Faith and Environmentalism: A personal reflection. Summit to Salish Sea: Inquiries and Essays, 3(1). Retrieved June 23, 2021 from https://cedar.wwu.edu/s2ss/vol3/iss1/2

- Djupe PA, Hunt PK. Beyond the Lynn White thesis: Congregational effects on environmental concern. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(4):670–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01472.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driver BL, Dustin D, Baltic T, Elsner G, Peterson G, editors. Nature and the human spirit: Toward an expanded land management ethic. Venture Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Egri CP. Spiritual connections with the natural environment: Pathways for global change. Organization & Environment. 1997;10(4):407–431. doi: 10.1177/192181069701000405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farinmade AE, Ogunyebi AL, Omoyajowo KO. Studying the effect of cement dust on photosynthetic pigments of plants on the example Ewekoro cement industry, Nigeria. Technogenic and Ecological Safety. 2019;5:22–30. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.2413063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, B. 92018). Les voix des Religions sur le Développement Durable, Ministère fédéral allemand de la Coopération économique et du Développement (BMZ) (pp. 1–180_.

- Goleman D, Small G, Braden G, Lipton BH, McTaggart L, Braden G, Archterberg B. Measuring the immeasurable: The scientific case for spirituality. Louisville, CO: Sounds True publishers; 2008. pp. 1–552. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A. K. Y. (2009–2010). Environmental Ethics and Spiritual Ecofeminism as tools for environmental education in a politicized ethics of care, Faculteit Geneeskunde en Farmacie, Vakgroep Menselijke Ecologie, Postgraduate and Master Programme in Human Ecology (pp. 1–11).

- Granberg-Michaelson W. Redeeming the creation: The Rio Earth summit: Challenges for the churches. Geneva: WCC Publ; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. (2021). What is green Christians? Retrieved from https://greenchristian.org.uk/about/what-is-green-christian/

- Grésillon É, Sajaloli B. L’Église verte ? La construction d’une écologie catholique : étapes et tensions. VertigO. 2015 doi: 10.4000/vertigo.15905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groen J. From Malaise to Re-enchantment. Journal for the Study of Spirituality. 2013;3(1):46–55. doi: 10.1179/2044024313Z.0000000004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guth JL, Kellstedt LA, Smidt CE, Green JC. Theological perspectives and environmentalism among religious activists. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1993;32(4):373–382. doi: 10.2307/1387177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hand CM, Van Liere KD. Religion, mastery-over-nature, and environmental concern. Social Forces. 1984;63(2):555–570. doi: 10.2307/2579062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Paragament KI. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. The American Psychologist. 2003;58(1):64–74. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Jacob, D., Taylor, M., Bindi, M., Brown, S., Camilloni, I., Diedhiou, A., Djalante, R., Ebi, K. L., Engelbrecht, F., Guiot, J., Hijioka, Y., Mehrotra, S., Payne, A., Seneviratne, S. I., Thomas, A., Warren, R. F., Zhou, G., & Tschakert, P. (2018). Impacts of 1.5 C global warming on natural and human systems. Global warming of 1.5 C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., & al. (eds.)]. In Press: 175–301.

- Hope AL, Jones CR. The impact of religious faith on attitudes to environmental issues and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies: A mixed methods study. Technology in Society. 2014;38:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2014.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Infield, M., & Mugisha, A. (2010). Integrating cultural, spiritual and ethical dimensions into conservation practice in a rapidly changing world prepared for the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation by Fauna & Flora International. Macarthur Foundation conservation White Paper series.

- Jenkins W, Chapple CK. Religion and Environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2011;36:441–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-042610-103728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kagany CL, Willits FK. A greening of religion? Some evidence from a Pennsylvania sample. Social Science Quarterly. 1993;74(3):674–683. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser FG, Ranney M, Hartig T, Bowler PA. Ecological behavior, environmental attitude, and feelings of responsibility for the environment. European Psychologist. 1999;4(2):59–74. doi: 10.1027//1016-9040.4.2.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagy CL, Nelsen HM. Religion and environmental concern: Challenging the dominant assumptions. Review of Religious Research. 1995;37(1):33–45. doi: 10.2307/3512069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koehrsen J. Eco-spirituality in environmental action studying Dark Green Religion in the German Energy transition. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture. 2018;12(1):34–54. doi: 10.1558/jsrnc.33915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications international scholarly research notices. Vol. 2012, Article ID 278730, pp. 1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Koenig HG. Concerns about measuring “spirituality” in research”. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196(5):349–355. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816ff796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King DE, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kolade O., Egbetokun A., Rae, D., Hussain G. (2019). Entrepreneurial resilience in turbulent environment: The role of spiritual capital. In Research Handbook on Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies: A Contextualized Approach. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kollmuss A, Agyeman J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research. 2002;8(3):239–260. doi: 10.1080/13504620220145401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Religion, aging, and health: Exploring new frontiers in medical care. Southern Medical Journal. 2004;97(12):1215–1222. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146488.39500.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krempl, S. A. (2014). Spirituality and environmental sustainability: Developing community engagement concepts in Perth, Western Australia. Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Curtin University Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute.

- Kumar S. Spirituality and sustainable development: A paradigm shift. Journal of Economic & Social Development. 2017;1:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D. (2009). L’église et la question écologique, coédition Croire aujourd’hui-Arsis, p. 204.

- Levin JS, Chatters LM. Religion, health, and psychological well-being in older adults: Findings from three national surveys. Journal of Aging and Health. 1998;10(4):504–531. doi: 10.1177/089826439801000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]