Abstract

The dlt operon (dltA to dltD) of Lactobacillus rhamnosus 7469 encodes four proteins responsible for the esterification of lipoteichoic acid (LTA) by d-alanine. These esters play an important role in controlling the net anionic charge of the poly (GroP) moiety of LTA. dltA and dltC encode the d-alanine–d-alanyl carrier protein ligase (Dcl) and d-alanyl carrier protein (Dcp), respectively. Whereas the functions of DltA and DltC are defined, the functions of DltB and DltD are unknown. To define the role of DltD, the gene was cloned and sequenced and a mutant was constructed by insertional mutagenesis of dltD from Lactobacillus casei 102S. Permeabilized cells of a dltD::erm mutant lacked the ability to incorporate d-alanine into LTA. This defect was complemented by the expression of DltD from pNZ123/dlt. In in vitro assays, DltD bound Dcp for ligation with d-alanine by Dcl in the presence of ATP. In contrast, the homologue of Dcp, the Escherichia coli acyl carrier protein (ACP), involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, was not bound to DltD and thus was not ligated with d-alanine. DltD also catalyzed the hydrolysis of the mischarged d-alanyl–ACP. The hydrophobic N-terminal sequence of DltD was required for anchoring the protein in the membrane. It is hypothesized that this membrane-associated DltD facilitates the binding of Dcp and Dcl for ligation of Dcp with d-alanine and that the resulting d-alanyl–Dcp is translocated to the primary site of d-alanylation.

Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) plays a vital role in the growth and physiology of gram-positive bacteria. It is postulated that this macroamphiphile modulates the activities of autolysins (4, 13), the binding of cations required for enzyme function (2, 20, 21, 27), and the electromechanical properties of the cell wall (37). The d-alanyl esters of LTA determine its net anionic charge and hence may regulate the functions of this polymer (32).

The biosynthesis of d-alanyl–LTA requires the 56-kDa d-alanine–d-alanyl carrier protein ligase (Dcl) and the 8.8-kDa d-alanyl carrier protein (Dcp) (33). Heaton and Neuhaus (19) isolated Dcp and showed that d-alanyl–Dcp donates its d-alanyl substituent to membrane-associated LTA. Debabov et al. (10) cloned, sequenced, and expressed the gene encoding this novel carrier protein, a homologue of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) involved in fatty acid biosynthesis. In addition to the genes encoding Dcl (DltA) and Dcp (DltC), the dlt operon contains two additional genes, dltB and dltD, encoding putative membrane proteins (10, 33).

The goal of this paper is to establish the function of the Lactobacillus rhamnosus protein encoded by dltD. To accomplish this goal, the gene was cloned, sequenced, and expressed in Escherichia coli with and without the sequence encoding the N-terminal hydrophobic domain. Additionally, the gene was inactivated and its protein product was examined for thioesterase activity and carrier protein binding specificity. The results support a role for this protein in hydrolyzing mischarged d-alanyl–ACP and as a facilitator of d-alanine ligation to the carrier protein Dcp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages, and plasmids.

All bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain, plasmid, or phage | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. rhamnosus 7469 | Formerly named L. casei ATCC 7469 | ATCC |

| L. casei 102S | L. casei ATCC 393 cured from plasmids | B. Chassy |

| L. casei 102S dltD::erm | Emr; dltD interrupted by erm | This study |

| E. coli XL-1 Blue MRF′ | Δ(mcrA) 183Δ (mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr) 173end1A supE44thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1lac [F′ proAB lacqZΔM15 Tn10(Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm(DE3)pLysS | Novagene |

| E. coli DH5α | F− f80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk+) supE44 λ− thi-1 girA96 relA1 | Gibco-BRL |

| Phages (phagemids) | ||

| λZAPII [Bluescript SK(−)] | Apr cloning vector | Stratagene |

| VCSM13 | Helper phage | Stratagene |

| λZAPII(−)DE43 | 4.3 kb of L. rhamnosus DNA containing dltA, dltB, dltC, and partial dltD | 10 |

| λZAPII(−)A65 | 6.5 kb of L. rhamnosus DNA containing partial dltB, dltC, dltD, and downstream flanking region | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET-3d | Expression vector | Novagene |

| pDltD | Expression plasmid; dltD cloned into pET-3d | This study |

| pΔDltD | Expression plasmid; ΔdltD cloned into pET-3d | This study |

| pVE6006 | Emr Cmr Ts shuttle vector | 30 |

| pNZ123 | Cmr shuttle vector | 46 |

| pΔDltD/erm | 1.2-kb EcoICR erm fragment of pVE6006 joined to BamHI blunt-ended pΔDltD in direct orientation to ΔdltD | This study |

| pNZ123/dlt | 4.895-kb fragment containing dlt operon cloned into HindIII of pNZ123 | This study |

Emr, erythromycin resistant; Cmr, choramphenicol resistant; Apr, ampicillin resistant; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Chemicals and reagents.

[35S]dATP (600 Ci/mmol in 5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]), d-[14C]alanine (43 mCi/mmol), and dithiothreitol (DTT) were products of ICN Biochemicals, Inc. Medium supplies were obtained from Difco Laboratories. Tetracycline, ampicillin, carbenicillin, erythromycin, EDTA, Tris, bis-Tris, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), and chlorhexidine were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. Solutions of phenol-chloroform were products of Amresco Inc. Metricel filter membranes (GN-6) and Econo-Safe scintillation cocktail were purchased from Gelman Sciences and RPI Corp., respectively. Restriction enzymes were obtained from a number of suppliers and were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isopropyl-β-d-galactoside (IPTG) and EcoRI (NotI) adapters were purchased from Gibco-BRL. The Genius System nonradioactive DNA labeling kit and DIG nucleic acid detection kit were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim GmbH. Gigapack II Plus packaging extracts, T4 DNA ligase, and PfuTurbo DNA polymerase were obtained from Stratagene. The Sequenase and PCR kits were purchased from United States Biochemical Corp. and MBI Fermentas, respectively. BioBlot nitrocellulose blotting membranes were purchased from Costar, Inc. The QIAprep spin miniprep, QIAquick nucleotide removal, and QIAquick gel extraction kits were obtained from Qiagen. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.

Growth of bacteria.

E. coli was cultured in either Luria-Bertrani (LB) broth or 2× YT (2× yeast extract-tryptone) medium and plated on either LB agar or LB agarose (41). L. rhamnosus 7469 and Lactobacillus casei 102S were cultured in MRS medium (Difco). For electroporation, L. casei 102S was grown in a low-salt medium (LL) containing (grams/liter) tryptone, 15; yeast extract, 5; MgSO4, 0.01; MnSO4, 0.005; glucose, 10; and 5 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:30 with fresh LL medium, and the cells were grown for an additional 3 to 3.5 h at 37°C. The cells were collected by centrifugation, washed several times with water (4°C), and resuspended in 0.01 volume of cold 10% glycerol. Aliquots of cells were stored at −80°C. Tetracycline, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol were used to select and maintain plasmids in E. coli (10, 100, and 20 μg/ml, respectively). For L. casei 102S with plasmid and chromosomal integration, 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and 5 μg of erythromycin/ml, respectively, were used. Competent cultures of E. coli were prepared by the method of Hanahan (17). Bacteriophages were propagated by standard methods (41).

DNA techniques.

L. rhamnosus 7469 and L. casei 102S were lysed by the method of Chassy and Giuffrida (7). Plasmids from L. casei 102S were isolated according to the method of O'Sullivan and Klaenhammer (36). Restriction digests, agarose and acrylamide gel electrophoreses, Southern blots, small- and large-scale plasmid and phage DNA preparations, transformations, and isolation of chromosomal DNA were performed by standard techniques (41). For the preparation of high-quality plasmids and DNA fragments, Qiagen kits were used. Digoxigenin labeling of the DNA probe, Southern blotting, and colony hybridizations were performed according to the conditions described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH). Both strands of DNA were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method (42) with the use of Sequenase version 2.0 DNA polymerase (47).

Sequence analyses.

The protein database searches were performed by the BLAST algorithm (1), and the deduced amino acid sequences were analyzed with the University of Wisconsin Genetic Computer Group sequence analysis software package, version 9.0 (11). Multiple alignments and consensus sequences were accomplished with PILEUP and determined with PRETTY, respectively. Comparisons of homologous proteins were accomplished with GAP. Remote homologies were detected by the method of Karplus et al. (22). The MacVector sequence analysis programs were used for the design of primers for PCR and sequencing and for the calculation of molecular masses, isoelectric points, and hydrophobicity profiles of proteins. The locations of protein and signal peptidase cleavage sites were predicted with the Signal P algorithm (34).

Construction of an L. rhamnosus AvaI library.

A restriction map of the dlt chromosomal region was generated by Southern analyses of L. rhamnosus restriction digests with the 389-bp digoxigenin-labeled probe complementary to nucleotides (nt) 3029 to 3417 of the dlt operon (Fig. 1A) (10). The map shows four restriction fragments (AvaI, DraI, BalI, and HincII) which contain the downstream region of the dlt operon. The 6.5-kb AvaI fragment was selected for cloning. Chromosomal DNA fragments were purified after AvaI digestion and treated with DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment for 40 min at 37°C to generate blunt ends. EcoRI restriction sites were introduced by blunt-end ligation of phosphorylated EcoRI (NotI) adaptors. The resulting DNA was ligated into λZAPII EcoRI arms. This preparation was packaged with Gigapack II packaging extract and used to infect E. coli XL-1 Blue MRF'. Phages from the resulting plaques were transferred to Nytran maximum-strength membranes and screened with the above-mentioned 389-bp probe. A plaque from the hybridizing clones, designated λZAPII(−)A65, was purified, the phagemid was rescued by helper phage VCSM13, and single-stranded DNA was isolated for sequence analysis.

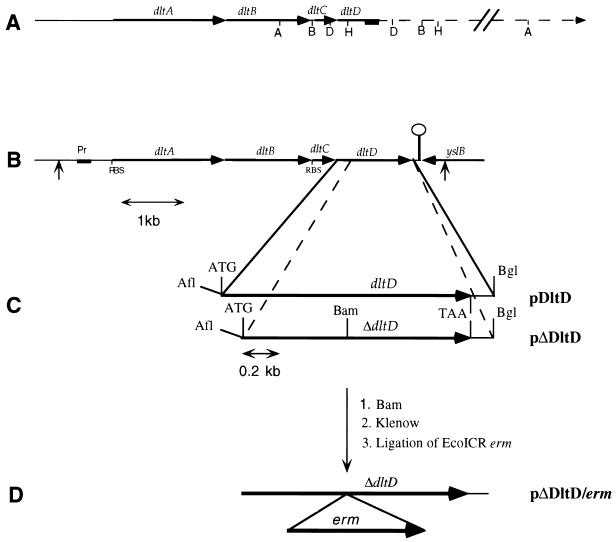

FIG. 1.

Cloning strategy for the isolation, expression, insertional inactivation, and complementation of dltD. (A) L. rhamnosus chromosomal map of dltD and flanking regions. The site of probe hybridization to dltD is shown by the solid box. (B) Physical map of the L. rhamnosus dlt operon. ORFs are shown by arrows, and the terminator of transcription is shown by ○. The positions of primers for the amplification of the dlt operon and its cloning into pNZ123 are shown by vertical arrows. (C) Inserts containing dltD and ΔdltD in pET-3d, designated pDltD and pΔDltD. The AflIII and BglII sites were introduced by PCR with the mutagenic primers described in Materials and Methods. (D) Cloning of the EcoICR erm fragment from pVE6006 into the BamHI site of ΔdltD to obtain the plasmid (pΔDltD/erm) for insertional inactivation. Pr, promoter; RBS, ribosome binding site; ATG, start codon; TAA, termination codon; A, AvaI; B, BalI; D, DraI; H, HincII, Afl, AflIII; Bam, BamHI; Bgl, BglII.

Construction of pDltD and pΔDltD.

To construct the plasmids for dltD and ΔdltD expression, amplifications and mutations of the gene were accomplished by PCR. Each reaction was carried out with λZapII(−)A65 DNA and mutagenic primers. For the construction of pDltD, primer I, 5′-CGAACAAGCAacATGtcAAAACCGATC-3′ (the mutagenized nucleotides are lowercase; the restriction site is underlined), was complementary to the minus strand of the A65 insert and positioned a new AflIII site to span the ATG start codon of dltD. Primer II, 5′-GATGGCACCTAgAtCTGACTGGCC-3′, was complementary to the plus strand of the A65 insert and positioned a new BglII site 10 nt downstream of the termination codon of dltD. For the construction of pΔDltD, the first primer, 5′-GCGGCCAGCTaCATGTCGGCC-3′, was complementary to the minus strand of the A65 insert and positioned a new AflIII site to span the ATG codon encoding Met48 of DltD. The second primer was the same as primer II used for the construction of pDltD. Both DNA fragments were amplified (25 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min), digested with AflIII and BglII, and ligated into the pET-3d vector (45) which had been digested with NcoI and BamHI. The ligation mixtures were used to transform E. coli XL-1 Blue MRF'. Clones containing plasmids with dltD or ΔdltD inserts, designated pDltD and pΔDltD, respectively, were identified by restriction and sequence analyses (Fig. 1C). These plasmids were used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS for expression studies.

Expression of dltD and ΔdltD in E. coli.

E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS containing either pDltD or pΔDltD was grown in 100 ml of LB broth with 100 μg of carbenicillin/ml at 37°C (300 rpm). At an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7, the cultures were induced with 0.4 mM IPTG, and the cells were harvested 2 h after induction. The expression of dltD and ΔdltD was observed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (26). To prepare soluble and insoluble protein fractions for this analysis, cells were suspended in 0.1 culture volume of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and disintegrated with a Labsonic U ultrasonic homogenizer (B. Braun Biotech, Inc.) for 3 min at 60-s intervals. The disrupted cells were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min, and the pellet was analyzed for insoluble proteins. The E. coli membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation of the supernatant fraction at 200,000 × g for 90 min and homogenized in a minimal amount of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 10% glycerol. Membrane fragments were washed by three cycles of differential centrifugation at 10,000 × g and 200,000 × g. The washed membranes (18.5 mg of protein) were suspended in 1 ml of 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 10% glycerol. Protein was measured with the Bradford reagent (Pierce Chemical Co.). Aliquots of membranes were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

For the preparation of ΔDltD, a pellet (inclusion bodies) as described above after centrifugation was dissolved in 8 M urea, centrifuged, and dialyzed against 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). After dialysis, the pellet containing ΔDltD was collected by centrifugation and dissolved in a minimal volume of 10 mM NaOH. The protein solution was applied to a Sephacryl S-200 column (1 by 50 cm), and ΔDltD was eluted with 10 mM NaOH. The fraction containing ΔDltD was collected, concentrated on a Macrosep centrifugal concentrator (10K) (Filtron Technology Corp.), and stored in aliquots at −80°C.

Expression and purification of Dcp and Dcl.

Dcp was expressed and purified according to the method of Debabov et al. (10). The conversion of apo-Dcp to holo-Dcp was carried out using recombinant holo-ACP synthase generously provided by R. H. Lambalot, R. S. Flugel, and C. T. Walsh (Harvard University) (10). Dcl was expressed according to the method of Heaton and Neuhaus (18) and purified from inclusion bodies. In brief, a pellet obtained after centrifugation of sonicated cells was dissolved in 6 M urea, centrifuged, and dialyzed against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (PPB) (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM DTT. After dialysis, the protein solution was applied to a Q-Sepharose fast flow column (2.6 by 5.0 cm) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), which was washed with 25 mM PPB (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM DTT until the optical density at 254 nm returned to baseline. Dcl was eluted with a 0 to 1.0 M NaCl gradient (10 volumes) in the same buffer. The first peak containing Dcl was collected, concentrated on a filtron centrifugal concentrator (10K), and stored in aliquots with 10% glycerol at −80°C. After purification, the Dcl had a specific activity of ca. 1,700 U/mg of protein (hydroxamate assay [3]) and a purity greater than 95% as estimated by SDS-PAGE.

d-Alanine incorporation assay.

For the assay of d-alanine incorporation into LTA, L. casei 102S was permeabilized with toluene at 4°C according to the method of Childs and Neuhaus (8). Alternatively, membranes from L. casei 102S were isolated according to a procedure described previously (19) using a French pressure cell for the disruption of cells. The incorporation of d-alanine into either the permeabilized cells or membranes was carried out according to previously described protocols (8, 19) in a total volume of 50 μl. For the incorporation of d-alanine into LTA using membranes, 1.1 nmol of recombinant Dcp and 5 U of Dcl from L. rhamnosus were used.

Construction of dltD::erm mutant of L. casei 102S.

For the insertional inactivation of the dltD gene, ΔdltD interrupted by erm was used (Fig. 1D). For its preparation, the 1.175-kb EcoICR fragment of pVE6006, which encodes Emr, was cloned into the BamHI site of pΔdltD blunt-ended by Klenow DNA polymerase. The resulting plasmid, pΔDltD/erm, was isolated from E. coli DH5α. Plasmid pΔdltD/erm (30 μg of DNA per 100 μl of cells) was electroporated into L. casei 102S (1.8 kV; R = 129 Ω; 2-mm-gap cuvette) (BTX Electroporation System). After the pulse, the cells were immediately diluted with 2 ml of ice-cold MRS broth and incubated for 10 min on ice and then for 1.5 h at 37°C. Integrants were selected by plating them on MRS plus erythromycin at 37°C under 5 to 10% CO2.

Complementation of dltD::erm in L. casei 102S.

For complementation of the dltD mutation, the dlt operon of L. rhamnosus, including its promoter, was cloned into pNZ123 (Fig. 1B). For the construction of pNZ123/dlt, a 4.895-kb dlt fragment was amplified by PCR (40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 42.5°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 12 min) with PfuTurbo DNA polymerase, with primers (5′-GATATATTTAAGCTTTTTCGATGGTCCG-3′) and (5′-GCAGCAGGTATTaaGCTTTGCAGTCGAAGGAGC-3′) and chromosomal DNA from L. rhamnosus 7469 as the template. In these primers, the HindIII site is underlined and bases not complementary to the dlt sequence are shown in lowercase letters. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with HindIII and ligated into pNZ123. The ligation mixture was used to transform L. casei 102S and the L. casei 102S dltD mutant as described above. Cmr clones containing the recombinant pNZ123/dlt were identified by restriction and PCR analyses.

Binding of Dcp to ΔDltD on NC membranes.

To determine whether ΔDltD complexes with the carrier protein, ΔDltD in 10 mM NaOH was bound to nitrocellulose (NC) membranes. The membranes were washed with 25 mM PPB (pH 6.8) and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1.5 h, and the excess albumin was removed with the same buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl. The NC membranes were incubated with either d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp or d-[14C]alanyl–ACP or alternatively with either Dcp or ACP. d-[14C]Alanyl–Dcp and d-[14C]alanyl–ACP were prepared and purified according to previously described procedures (19). After incubation, the NC membranes were washed with 25 mM PPB containing 0.1 M NaCl. In those binding experiments containing Dcp or ACP, the NC membranes were incubated in 1 ml of reaction mixture containing 0.11 mM d-[14C]alanine (43 mCi/mmol), 8.0 U of recombinant Dcl, 30 mM bis-Tris (pH 6.5), 10 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT at 37°C for 1.5 h. The NC membranes were washed as described above, dried, and exposed for 3 to 5 days to X-OMAT (Kodak Co.) film using a Kodak Bio-Max intensifying screen.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of dltD from L. rhamnosus together with that of dltA to -C and the adjacent chromosomal regions was reported to GenBank (accession no. AF192553).

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the dltD gene.

To clone dltD from L. rhamnosus, an AvaI genome library was constructed and screened with a digoxigenin-labeled probe complementary to a previously determined partial dltD sequence (10) (Fig. 1A). A lambda clone [λZapII(−)A65] hybridizing with this probe was identified, and its 6.5-kb insert was isolated and sequenced. The complete sequence of dltD was determined from this insert. This gene encoded a putative protein of 423 amino acids (aa) whose mass and pI were 47.738 kDa and 9.54, respectively.

Since the dlt operons from at least two organisms, Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus mutans, contained five genes (38; D. A. Boyd, D. G. Cvitkovitch, A. S. Bleiweis, M. Y. Kiriukhin, D. V. Debabov, F. C. Neuhaus, and I. R. Hamilton, submitted for publication), it was necessary to analyze the downstream sequence in L. rhamnosus for additional genes and for the transcriptional terminator. The analysis 3′ to dltD revealed a putative terminator 84 nt downstream of the dltD stop codon (Fig. 1B). It is a 12-nt inverted repeat followed by a series of T residues (TTTATTTT). At 104 nt 3′ to the terminator, another open reading frame (ORF) is encoded on the opposite strand (Fig. 1B). The deduced amino acid sequence of this ORF (136 aa) shows 31% identity (61% similarity) to the YslB protein of B. subtilis. Since it is encoded in the orientation opposite to that of the dlt operon and downstream of the terminator, this gene does not belong to the dlt operon. Thus, as in the case of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus xylosus (39), the dlt operon of L. rhamnosus contains only four genes.

Comparison of L. rhamnosus DltD with those from different gram-positive organisms.

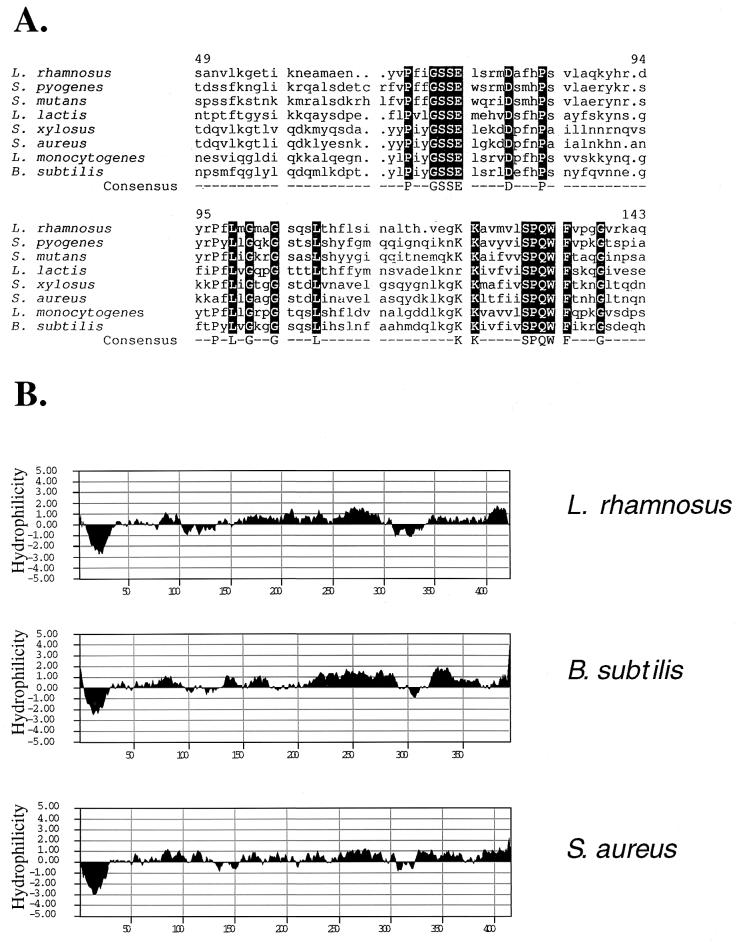

To establish the consensus sequences in DltDs, the deduced amino acid sequence from L. rhamnosus was aligned with those from seven gram-positive bacteria. The sequence of DltD from L. rhamnosus is 25 to 42% identical to those of the other DltDs. Two mostly conserved sequences were identified, PXXGSSEXXXXDXXXP (positions 69 to 83) and KKXXXXXSPQWFXXXG (positions 123 to 138) (Fig. 2A). Proteins of known function with primary sequence identity to these consensus sequences were not identified by BLAST search. However, there is some similarity of the first consensus sequence to the signature sequence of thioesterases, GXSXG (5), and the corresponding sequence of myristoyl-ACP-specific thioesterase from Vibrio harveyi (AASLS) (28). The sequences of DltDs from a variety of organisms are compatible with the structure of amino- and phosphotransferases as determined by the method for remote-homology detection (22). According to the CATH classification (35), these proteins belong to the alpha beta class three-layer (alpha-beta-alpha) sandwich architecture. Interestingly, as will be shown below, DltD catalyzes the hydrolytic cleavage of the mischarged d-alanyl–ACP. Thioesterases, which catalyze this activity, have the same architecture.

FIG. 2.

Consensus sequences of DltD (A) and hydropathy plots of DltDs from L. rhamnosus, B. subtilis, and S. aureus (B). The multiple alignment was performed with the PILEUP program, and the consensus sequences were determined by the PRETTY program. In this alignment, the sequence of L. rhamnosus DltD (aa 49 to 144) was compared with those of seven other gram-positive bacteria: Streptococcus pyogenes, contig 320 (B. A. Roe, http://dna1.chem.uokhnor.edu/strep.html); S. mutans, GenBank accession no. AF049357 (44) and AF051356 (Boyd et al., unpublished); S. aureus, accession no. AF101234 (39); S. xylosus, accession no. AF032440 (39); L. lactis, accession no. U81621 (12); Listeria monocytogenes, accession no. AJ012255 (P. Trieu-Cuot, E. Abachin, C. Poyart, and P. Berche, unpublished data); and B. subtilis, accession no. X73124 (15). (B) Hydropathy plots performed by the method of Kyte and Doolittle (25).

It was proposed that DltD from S. aureus has an N-terminal signal peptide with a cleavage site weakly conserved among four DltDs (39), whereas that from B. subtilis was proposed to have a noncleavable signal peptide functioning as an anchor (38). As shown in the hydropathy profile (Fig. 2B), DltD from L. rhamnosus also has a single N-terminal hydrophobic domain. However, based on the absence of a conserved cleavage site in all DltDs (eight homologues) as predicted by the Signal P algorithm (34), we proposed that this protein might not contain an N-terminal cleavable signal peptide and thus may contain a transmembrane anchor domain. To establish whether this domain is cleaved, it was necessary to express DltD with and without the domain.

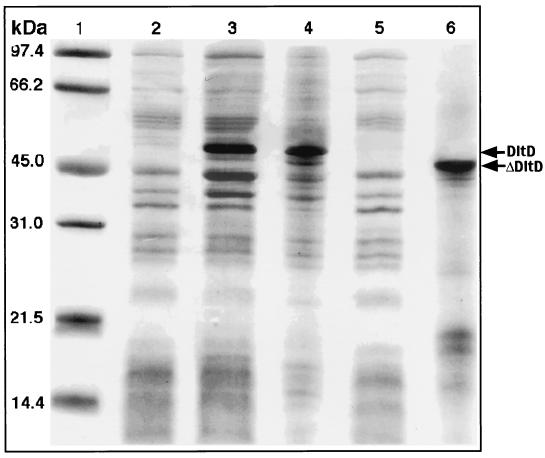

Expression of dltD and ΔdltD in E. coli.

To express DltD and ΔDltD (minus the 48 N-terminal residues), the corresponding DNA fragments were subcloned into the pET-3d expression vector; the plasmids pDltD and pΔDltD (Fig. 1C) were used to transform E. coli strain BL21(DE3) pLysS. After induction of the resulting strains with IPTG, the insoluble and membrane proteins were analyzed (Fig. 3). Both DltD and ΔDltD accumulated in the inclusion bodies. However, DltD but not ΔDltD accumulated in the membrane fraction. Thus, we have demonstrated that the N-terminal hydrophobic domain of DltD is not cleaved in E. coli and may be required for anchoring the protein in the membrane. While the growth of E. coli stopped after induction of dltD, this toxic effect was not observed in the expression of ΔDltD. ΔDltD was purified (99% purity by SDS-PAGE) from the inclusion bodies by treatment with 8 M urea, dialysis, and subsequent gel filtration on Sephacryl S-200 in 10 mM NaOH. All attempts to maintain the protein in solution in concentrations greater than 5 μg/ml (pH 6 to 8), even in the presence of the detergents Triton X-100 and CHAPS {3-[(3- cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}, were unsuccessful. Thus, many of the experiments reported in this paper utilized ΔDltD (15 mg/ml) stored in 10 mM NaOH at −80°C.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of DltD and ΔDltD expression in E. coli. Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, purified membranes without expression; lane 3, purified membranes after expression of DltD (pDltD); lane 4, DltD from inclusion bodies dissolved in 8 M urea; lane 5, purified membranes after expression of ΔDltD (pΔDltD); lane 6, ΔDltD from inclusion bodies dissolved in 8 M urea.

Insertional inactivation of dltD.

To define the role of DltD, a mutant strain was constructed by insertional mutagenesis. Because L. rhamnosus 7469 cannot be transformed, L. casei 102S (Table 1) was chosen for the mutagenesis experiment. Using a suicide plasmid with ΔdltD interrupted by the erythromycin resistance marker (pΔdltD/erm [Fig. 1D]), we obtained an Emr mutant with inactivated dltD. It was confirmed by PCR that erm was integrated into dltD by allelic replacement. The doubling time of the mutant (1.31 h) was similar to that of the parent (1.21 h).

To establish that dltD in the mutant is defective, cells were permeabilized and assayed for d-[14C]alanine incorporation into LTA. As shown in Table 2, the L. casei 102S dltD::erm mutant is defective for d-alanylation. Thus, dltD is required for the synthesis of d-alanyl–LTA in permeabilized cells. However, when purified membranes from the dltD mutant were incubated with recombinant Dcl (DltA) and Dcp (DltC), 50% of the activity observed for the parent membranes was detected (Table 2). This result suggested that the function of DltD could be partially circumvented in the isolated membrane system, and thus, DltD may not be the primary enzyme responsible for the d-alanylation of LTA.

TABLE 2.

Incorporation of d-[14C]alanine into permeabilized cells and membranes from L. casei 102S (dltD+) and its dltD::erm mutant

| Genotypea | Incorporation of d-[14C]alanine (cpm)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Permeabilized cells | Membranes | |

| dltD+ | 960 ± 20 | 1,660 ± 20 |

| dltD+ (heat treated) | 15 ± 4 | 40 ± 6 |

| dltD::erm | 55 ± 6 | 890 ± 20 |

| dltD+ + (pNZ123/dlt) | 2,540 ± 20 | 1,790 ± 20 |

| dltD::erm + (pNZ123/dlt) | 2,680 ± 20 | 1,840 ± 20 |

dltD+ is the genotype of L. casei 102S (wild type).

Cells (260 μg [wet weight]) were permeabilized with 0.6% toluene and incubated with ATP and d-[14C]alanine according to the d-alanine incorporation assay described in Materials and Methods. Membranes (120 μg of protein) were incubated with ATP, d-[14C]alanine, and recombinant Dcl and Dcp from L. rhamnosus according to the d-alanine incorporation assay.

The size of the mutant was increased on average to 1.6 times that of the parent. The mean length of the parent cells was 1.2 ± 0.25 μm, while the mean length of the mutant cells was 1.9 ± 0.45 μm (data not shown). No other defect could be observed by scanning electron microscopy. One of the unique phenotypes of this mutant was the higher susceptibility to the action of the cationic compounds CTAB and chlorhexidine (data not shown). Similar observations with the cationic antimicrobial peptides, e.g., defensins and protegrins, were also made with insertional mutants of S. aureus in the dlt operon (39). Therefore, the dltD mutant of L. casei 102S may have a higher polyanionic surface charge and thus bind more of the two cationic compounds.

To confirm that this mutation is in fact responsible for the loss of d-alanylation, a plasmid containing dltA to -D and its native promoter was used to complement the dltD::erm mutant (Table 2). The permeabilized mutant with this plasmid gave a 2.8-fold-higher amount of d-alanine incorporation than permeabilized L. casei 102S, whereas membranes prepared from this complemented mutant (dltD::erm/dltD+) gave approximately the same activity as the parent membranes (dltD+) (Table 2).

Binding properties of DltD.

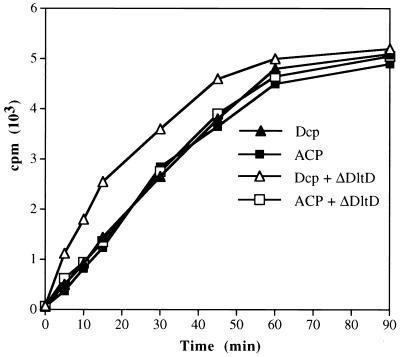

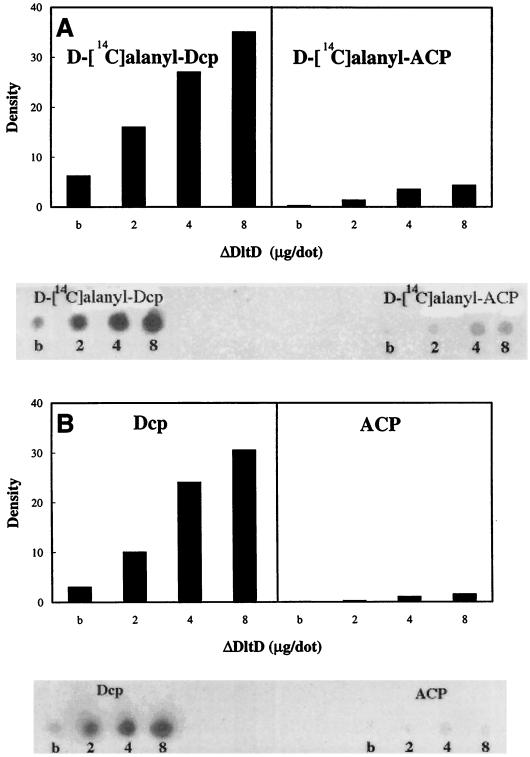

Given the basic pI of DltD (9.5), we proposed that this protein might bind Dcl (pI 5.2) and Dcp (pI 3.8). Evidence for this proposal was observed in studies of the ligation reaction catalyzed by Dcl (Fig. 4). The addition of ΔDltD to the reaction mixture containing Dcl and Dcp resulted in a twofold increase in the initial rate of ligation of Dcp with d-alanine. However, when ACP (pI 3.9) from E. coli was substituted for Dcp, no increase in the rate of ligation was observed in the presence of ΔDltD (Fig. 4). It was concluded that ΔDltD stimulates the ligation of Dcp with d-alanine but not that with ACP. Because ΔDltD is sparingly soluble in pH 6 to -8 buffers, it was impossible to increase the concentration of the protein in these reaction mixtures. To circumvent this problem, a binding assay was designed using ΔDltD bound to NC membranes. When increasing amounts of ΔDltD were bound to these membranes and incubated with either d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp or d-[14C]alanyl–ACP, only d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp was bound to ΔDltD (Fig. 5A). Thus, it was concluded that ΔDltD can selectively bind d-alanyl–Dcp.

FIG. 4.

Time courses of d-alanyl–Dcp and d-alanyl–ACP formation in the presence and absence of ΔDltD. The 400-μl reaction mixtures contained 5 nmol of the carrier protein, 12 U of Dcl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 0.11 mM d-[14C]alanine (46 mCi/mmol), 5 mM DTT, and 30 mM bis-Tris (pH 6.5). For the open symbols, 2 μg of ΔDltD was added to the mixtures. The amounts of d-alanyl–Dcp and d-alanyl–ACP were measured as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 5.

Binding of d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp and d-[14C]alanyl–ACP (A) and ligation of d-[14C]alanine to Dcp and ACP (B) in the presence of ΔDltD on NC membranes. (A) Either d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp or d-[14C]alanyl–ACP was incubated with the NC membrane containing increasing amounts of ΔDltD, and the amount bound was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Either Dcp or ACP was incubated with the membrane containing ΔDltD, and after washing, the filter was incubated in the presence of Dcl, ATP, and d-[14C]alanine as described in Materials and Methods. b, 8 μg of ΔDltD previously treated at 100°C for 2 min.

It may be argued that ACP from E. coli is not a good reference protein for these experiments. Although ACP from L. rhamnosus has not been isolated, the corresponding protein has been isolated from B. subtilis (31). This ACP strongly resembles (sequence 61% identical) E. coli ACP. When B. subtilis ACP replaced E. coli ACP in our experiments, the observations were identical to those with ACP from E. coli (data not shown).

The ability of ΔDltD to bind Dcp and ligate d-alanine in the presence of Dcl was also tested. As shown in Fig. 5B, the addition of either Dcp or ACP to increasing amounts of ΔDltD, followed by washing with 0.1 M NaCl in phosphate buffer before incubation of the membrane in the presence of Dcl, ATP, and d-[14C]alanine, showed that only in the case of Dcp is d-[14C]alanine ligated to the carrier protein. These results suggest that in the presence of ΔDltD, the ligation of d-alanine catalyzed by Dcl is specific for Dcp.

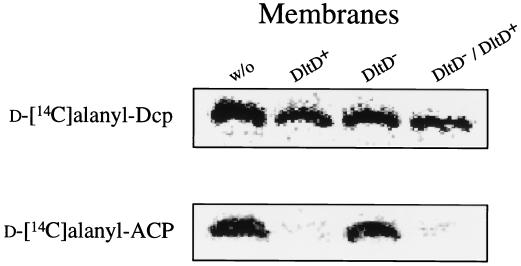

Thioesterase activity of DltD.

If DltD functioned as a thioesterase specific for d-alanyl–ACP, the results of binding specificity could be interpreted in terms of the hydrolytic release of the radiolabeled d-alanine from d-[14C]alanyl–ACP. It was previously observed that the formation of d-alanyl–ACP was inhibited while the formation of d-alanyl–Dcp was not affected when membranes were added to the d-alanine incorporation assay (19). To test whether this inhibition is correlated with the presence of DltD, purified membranes (DltD+, DltD−, and DltD−/DltD+) were incubated with either Dcp or ACP in the presence of Dcl, ATP, and radiolabeled d-alanine. The formation of d-alanyl–ACP is inhibited only when parent membranes (DltD+) or complemented membranes (DltD−/DltD+) are used (Fig. 6). The results with ACP are distinct from those observed with Dcp. In the case of d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp, no effect on its formation is observed in those reaction mixtures containing either DltD+, DltD−, or DltD−/DltD+ membranes (Fig. 6). The inhibition of d-alanyl–ACP formation exerted by the addition of membranes showed either that DltD prevents ligation of d-alanine to ACP or that DltD has thioesterase activity for d-alanyl–ACP.

FIG. 6.

Formation of d-alanyl–Dcp and d-alanyl–ACP in the presence of DltD+, DltD−, and DltD−/DltD+ membranes. Nondenaturing PAGE (15%) was used to monitor the amount of either d-[14C]alanyl–Dcp or d-[14C]alanyl–ACP according to the method of Heaton and Neuhaus (19). The reactions were performed in 250-μl mixtures containing 8 U of Dcl, 5 nmol of either Dcp or ACP, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 30 mM bis-Tris buffer (pH 6.5), 10 mM ATP, and 110 μM d[14C]alanine (46 mCi/mmol) in the absence of membranes (w/o) and in the presence of membranes (130 μg) from L. casei 102S (dltD+), L. casei 102S (dltD::erm), and the dltD mutant which had been complemented with pNZ123/dlt (dltD::erm/dltD+). All reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C.

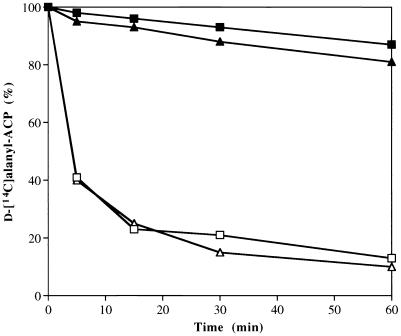

Thioesterase activity associated with DltD was directly tested by incubating d-[14C]alanyl–ACP with purified membranes (DltD+, DltD−, or DltD−/DltD+). As shown in Fig. 7, d-alanyl–ACP was hydrolyzed by membranes containing DltD+ or membranes from the complemented mutant (DltD−/ DltD+). In contrast, membranes from the dltD::erm strain did not effect the hydrolysis of this thioester. These results suggest that DltD has thioesterase activity with specificity for the mischarged carrier protein, d-alanyl–ACP.

FIG. 7.

Time courses of d-[14C]alanyl–ACP hydrolysis in the absence of membranes (■) and in the presence of DltD+(□), DltD−(▴), and DltD−/ DltD+(▵) membranes. The 250-μl reaction mixture contained 6.5 nmol of d-[14C]alanyl–ACP and 130 μg of membranes (except for the control) in 10 mM bis-Tris and 30 mM MgCl2. Samples (50 μl) were removed from the incubation mixture (37°C) at the indicated times, and the amounts of d-[14C]alanyl–ACP remaining were measured by precipitation with 10% trichloroacetic acid according to the method of Heaton and Neuhaus (19).

DISCUSSION

The dlt operon encodes four proteins which are required for the d-alanylation of LTA. The first gene encodes Dcl, which shares homology with over 200 nonribosomal peptide synthetases in a wide variety of organisms (18). These synthetases are characterized by several conserved signature sequences, the most common of which is the adenylation domain, GXXGXPK (23, 24). The second gene (dltB) encodes a putative transporter that has sequence similarity to a variety of proton antiporters involved in the efflux of tetracycline, quaternary ammonium compounds, and glycerol phosphate (33). One DltB homologue, AlgI, is a transporter involved in the acetylation of alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14). The 8.8-kDa protein (Dcp) encoded by the third gene is homologous to the ACPs involved in fatty acid and polyketide biosyntheses. The fourth gene, dltD, encodes a membrane protein which has no known homologue. The fact that dltD is translationally coupled with dltC in all reported organisms (eight) indicates a close functional or structural relationship between the two proteins (33). We hypothesized that one of the DltD functions is to ensure the ligation of d-alanine to the appropriate carrier protein, Dcp.

The present results suggest that DltD may be the protein responsible for discriminating between Dcp involved in the d-alanylation of LTA and ACP involved in fatty acid biosynthesis. This function may prevent gram-positive organisms from accumulating a pool of d-alanyl–ACP. In the absence of membranes containing DltD, Dcl ligates d-alanine to either Dcp or ACP. As shown previously (33), only Dcp participates in the incorporation of d-alanine into LTA. As in the case of other nonribosomal synthetic systems, it is essential that the d-alanylation machinery be able to purge the system of mischarged carrier proteins or to selectively bind the appropriate carrier protein for ligation with d-alanine.

To test the hypothesis that DltD binds d-alanyl–Dcp specifically, a binding assay was designed which allowed us to manipulate the concentration of ΔDltD and assess the binding of the carrier protein to DltD on an NC membrane. Only d-alanyl–Dcp bound to ΔDltD under these conditions. Thus, even though the pIs of Dcp and ACP are both acidic, only Dcp was ligated with d-alanine in the presence of ΔDltD bound to this membrane. Additional experiments indicated that DltD also possesses thioesterase activity for d-alanyl–ACP. Thus, not only does ACP not appear to be ligated with d-alanine in the presence of DltD on the membrane but DltD hydrolytically cleaves d-alanyl–ACP if it becomes ligated with d-alanine.

In most of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase modules, a thioesterase domain is encoded downstream of the synthetase genes (43). It has been speculated that these domains encode a thioesterase which functions to edit the product or purge synthetases of aberrant materials that might otherwise block the synthesis of normal products (6). Alternatively, in polyketide synthesis, thioesterases may be responsible for the release and concomitant cyclization of the processed chain (16). While the homology search described in this paper produced only a distant similarity with thioesterases, the correlation of the insertional inactivation of dltD with the defective hydrolytic cleavage of d-alanyl–ACP strongly supports the conclusion that DltD catalyzes thioesterase activity. However, it is not clear whether the hydrolytic cleavage of mischarged ACPs is the primary or only function of the protein. If this were the only function of the protein, one might expect permeabilized cells of the dltD mutant to show activity for d-alanine incorporation into LTA. Since this is not the case, it is reasonable to suggest that the enzyme functions both as a hydrolase of mischarged ACP and as a facilitator of d-alanine ligation to Dcp.

It is possible that DltD is multifunctional and thus also facilitates or enhances the d-alanylation of LTA. If DltD plays a role in the direct d-alanylation of LTA, it will be necessary to establish whether the protein is on the inner or outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane. It appears logical for the protein to be on the inner leaflet if it is to exert its selectivity for ligation of d-alanine to the carrier protein. However, if DltD is to enhance the d-alanylation of the LTA, one might speculate that the protein is located on the outer leaflet, the proposed site of d-alanylation. Thus, one of the goals of future experiments is to establish the topology of DltD. The present work only supports the conclusion that DltD is associated with the membrane and that the N-terminal sequence functions as a membrane-spanning domain for anchoring the protein.

One of the long-term goals of this research has been to determine the role of the membrane in the d-alanine incorporation system (29, 32, 40). Several suggested roles include (i) establishing a specific conformation of the LTA, (ii) anchoring an enzyme or protein that is required for d-alanine incorporation, and (iii) facilitating the formation of a specific LTA complex with other membrane constituents. The membrane protein, DltD, may function in one of these roles and thus is required for the incorporation of d-alanine into the LTA of permeabilized cells.

The importance of the dlt operon in the physiology of the gram-positive organism is illustrated by the variety of observed phenotypes. For example, in Streptococcus gordonii DL1 (Challis), insertional inactivation of dltA results in a loss of intrageneric coaggregation and in the formation of a variety of pleomorphs (9). In the case of S. mutans, Spatafora et al. (44) observed that a knockout mutation of the promoter of the dlt operon resulted in the defective synthesis of intracellular polysaccharides. On the other hand, insertional inactivation of dltC in this organism resulted in a loss of acid tolerance (Boyd et al., unpublished). In B. subtilis, deletion of either dltA, -B, -C, or -D resulted in mutants with enhanced autolytic activity (48). In L. lactis (12), it was found that mutants defective for DltD synthesis have enhanced UV sensitivity. As described in this paper, insertional inactivation of this gene in L. casei 102S results in an increase in cellular length and enhanced antimicrobial activity of CTAB and chlorhexidine. These phenotypes may be correlated to the decrease in d-alanylation of LTA, a result also observed in S. aureus, which leads to the enhanced sensitivity of these organisms to cationic antibiotics (39). It is apparent from these widely different phenotypes that the d-alanyl esters of LTA play a pleiotropic role in determining the properties of the cell surface.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dmitri V. Debabov and Michael Y. Kiriukhin made equal contributions to this paper.

The research was supported in part by Public Health Service grant RO1 GM51623 from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences.

We thank Bruce Chassy (University of Illinois) for the strain L. casei 102S and discussions of transformation in lactobacilli. We thank H. Ricardo Morbidoni and John E. Cronan, Jr. (University of Illinois) for ACP from B. subtilis. We are grateful to Ralph H. Lambalot, Roger S. Flugel, and Christopher T. Walsh (Harvard University) for the holo-ACP synthase and E. coli ACP. We are indebted to Sir James Baddiley and Werner Fischer (Universitat Erlangen) for discussions of these results. We also thank Eugene W. Minner for his generous help in the Electron Microscopy Facility of the Department of Neurobiology and Physiology (Northwestern University). We thank Andrei Gabrielian (Celera Genomics) for help in the protein sequence analyses. We are especially grateful to Michael P. Heaton (U.S. Meat Animal Research Center) for a critical reading of the manuscript and many discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald A R, Baddiley J, Heptinstall S. The alanine ester content and magnesium binding capacity of walls of Staphylococcus aureus H grown at different pH values. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;291:629–634. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baddiley J, Neuhaus F C. The enzymic activation of d-alanine. Biochem J. 1960;75:579–587. doi: 10.1042/bj0750579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierbaum G, Sahl H-G. Induction of autolysis of Staphylococcus simulans 22 by Pep5 and nisin and influence of the cationic peptides on the activity of the autolytic enzymes. In: Jung G, Sahl H-G, editors. Nisin and novel antibiotics. Leiden, The Netherlands: ESCOM; 1991. pp. 386–396. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner S. The molecular evolution of genes and proteins: a tale of two serines. Nature. 1988;334:528–530. doi: 10.1038/334528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler A R, Bate N, Cundliffe E. Impact of thioesterase activity on tylosin biosynthesis in Streptomyces fradiae. Chem Biol. 1999;6:287–292. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80074-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chassy B M, Giuffrida A. Method for the lysis of gram-positive, asporogenous bacteria with lysozyme. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:153–158. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.1.153-158.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Childs W C, III, Neuhaus F C. Biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid: characterization of ester-linked d-alanine in the in vitro-synthesized product. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:293–301. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.293-301.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemans D L, Kolenbrander P E, Debabov D V, Zhang Q, Lunsford R D, Sakone H, Whittaker C J, Heaton M P, Neuhaus F C. Insertional inactivation of genes responsible for the d-alanylation of lipoteichoic acid in Streptococcus gordonii DL1 (Challis) affects intrageneric coaggregations. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2464–2474. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2464-2474.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Debabov D V, Heaton M P, Zhang Q, Stewart K D, Lambalot R H, Neuhaus F C. The d-alanyl carrier protein in Lactobacillus casei: cloning, sequencing, and expression of dltC. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3869–3876. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3869-3876.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duwat P, Cochu A, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Characterization of Lactococcus lactis UV-sensitive mutants obtained by ISS-1 transposon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4473–4479. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4473-4479.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer W, Rosel P, Koch H U. Effect of alanine ester substitution and other structural features of lipoteichoic acids on their inhibitory activity against autolysins of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:467–475. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.467-475.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin M J, Ohman D E. Identification of algI and algJ which are required for alginate O acetylation in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate biosynthetic gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2186–2195. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2186-2195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser P, Kunst F, Arnaud M, Coudart M-P, Gonzales W, Hullo M-F, Ionescu M, Lubochinsky B, Marcelino L, Moszer I, Presecan E, Santana M, Schneider E, Schweizer J, Vertes A, Rapoport G, Danchin A. Bacillus subtilis genome project: cloning and sequencing of the 97 kb region from 325° to 333°. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:371–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gokhale R S, Hunziker D, Cane D E, Khosla C. Mechanism and specificity of the terminal thioesterase domain from the erythromycin polyketide synthase. Chem Biol. 1999;6:117–125. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanahan D. Studies of transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaton M P, Neuhaus F C. Biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid: cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Lactobacillus casei gene for the d-alanine activating enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4707–4717. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4707-4717.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heaton M P, Neuhaus F C. Role of the d-alanyl carrier protein in the biosynthesis of d-alanyl lipoteichoic acid. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:681–690. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.681-690.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heptinstall S, Archibald A R, Baddiley J. Teichoic acids and membrane function in bacteria. Nature. 1970;225:519–521. doi: 10.1038/225519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes A H, Hancock I C, Baddiley J. The function of teichoic acids in cation control in bacterial membranes. Biochem J. 1973;132:83–93. doi: 10.1042/bj1320083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karplus K, Barrett C, Hughey R. Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:846–856. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinkauf H, Von Dohren H. A nonribosomal system of peptide biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:335–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konz D, Marahiel M A. How do peptide synthetases generate structural diversity? Chem Biol. 1999;6:R39–R48. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert P A, Hancock I C, Baddiley J. Influence of alanyl ester residues on the binding of magnesium ions to teichoic acid. Biochem J. 1975;151:671–676. doi: 10.1042/bj1510671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawson D M, Derewenda U, Serre L, Ferri S, Szittner R, Wei Y, Meighen E A, Derewenda Z S. Structure of a myristoyl-ACP specific thioesterase from Vibrio harveyi. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9382–9388. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linzer R, Neuhaus F C. Biosynthesis of membrane teichoic acid: a role for the d-alanine activating enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:3196–3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maguin E, Duwat P, Hege T, Ehrlich D, Gruss A. New thermosensitive plasmid for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5633–5638. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5633-5638.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morbidoni H R, de Mendoza D, Cronan J E., Jr Bacillus subtilis acyl carrier protein is encoded in a cluster of lipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4794–4800. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4794-4800.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neuhaus F C, Linzer R, Reusch V M., Jr Biosynthesis of membrane teichoic acid: role of the d-alanine activating enzyme and d-alanine:membrane acceptor ligase. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;235:502–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuhaus F C, Heaton M P, Debabov D V, Zhang Q. The dlt operon in the biosynthesis of d-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid in Lactobacillus casei. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:77–84. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen H, Engelbreacht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orengo C A, Michie A D, Jones S, Jones D T, Swindells M B, Thornton J M. CATH-a: hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structures. 1997;5:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Sullivan D J, Klaenhammer T R. Rapid mini-prep isolation of high-quality plasmid DNA from Lactococcus and Lactobacillus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2730–2733. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2730-2733.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ou L-T, Marquis R E. Electromechanical interactions in cell walls of gram-positive cocci. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:92–101. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.1.92-101.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perego M, Glaser P, Minutello A, Strauch M A, Leopold K, Fischer W. Incorporation of d-alanine into lipoteichoic acid and wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis: identification of genes and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15595–15606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peschel A, Otto M, Jack R W, Kalbacher H, Jung G, Gotz F. Inactivation of the dlt operon in Staphylococcus aureus confers sensitivity to defensins, protegrins, and other antimicrobial peptides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8405–8410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reusch V M, Jr, Neuhaus F C. d-Alanine: membrane acceptor ligase from Lactobacillus casei. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:6136–6143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider A, Marahiel M A. Genetic evidence for a role of thioesterase domains, integrated in or associated with peptide synthetases, in non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:404–410. doi: 10.1007/s002030050590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spatafora G, Sheets A M, June R, Luyimbazi D, Howard K, Holbert R, Barnard D, El Janne M, Hudson M C. Regulated expression of the Streptococcus mutans dlt genes correlates with intracellular polysaccharide accumulation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2363–2372. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2363-2372.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Asseldonk M, de Vos W M, Simons G. Functional analysis of the Lactococcus lactis ups45 secretion signal in the secretion of a homologous proteinase and heterologous α-amylase. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;240:428–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00280397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabor S, Richardson C C. DNA sequence analysis with a modified bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4767–4771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wecke J, Perego M, Fischer W. d-Alanine deprivation of Bacillus subtilis teichoic acids is without effect on cell growth and morphology but affects the autolytic activity. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:123–129. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]