Abstract

Terrestrial open water evaporation is difficult to measure both in situ and remotely yet is critical for understanding changes in reservoirs, lakes, and inland seas from human management and climatically altered hydrological cycling. Multiple satellite missions and data systems (e.g., ECOSTRESS, OpenET) now operationally produce evapotranspiration (ET), but the open water evaporation data produced over millions of water bodies are algorithmically produced differently than the main ET data and are often overlooked in evaluation. Here, we evaluated the open water evaporation algorithm, AquaSEBS, used by ECOSTRESS and OpenET against 19 in situ open water evaporation sites from around the world using MODIS and Landsat data, making this one of the largest open water evaporation validations to date. Overall, our remotely sensed open water evaporation retrieval captured some variability and magnitude in the in situ data when controlling for high wind events (instantaneous: r2 = 0.71; bias = 13% of mean; RMSE = 38% of mean). Much of the instantaneous uncertainty was due to high wind events (u > mean daily 7.5 m·s−1) when the open water evaporation process shifts from radiatively-controlled to atmospherically-controlled; not accounting for high wind events decreases instantaneous accuracy significantly (r2 = 0.47; bias = 36% of mean; RMSE = 62% of mean). However, this sensitivity minimizes with temporal integration (e.g., daily RMSE = 1.2–1.5 mm·day−1). To benchmark AquaSEBS, we ran a suite of 11 machine learning models, but found that they did not significantly improve on the process-based formulation of AquaSEBS suggesting that the remaining error is from a combination of the in situ evaporation measurements, forcing data, and/or scaling mismatch; the machine learning models were able to predict error well in and of itself (r2 = 0.74). Our results provide confidence in the remotely sensed open water evaporation data, though not without uncertainty, and a foundation by which current and future missions may build such operational data.

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Hydrology

Introduction

Knowledge of terrestrial open water evaporation is necessary in understanding how and why changes in reservoirs, lakes, and inland seas occur, and how to manage these changes1,2. As climate extremes and human demand on freshwater sources increase, both society and natural ecosystems are impacted by shrinking reservoirs, lakes, and inland seas3–8. Two causes can shrink all these water bodies for a given known water height and surface discharge or human abstraction: (1) surface evaporation; and, (2) leakage9,10. Evaporation and leakage are very difficult to estimate and monitor accurately, yet only evaporation can change significantly from day to day, diurnally, and seasonally11. Half the water loss may be from evaporation alone, and could be roughly equal to human abstraction, which in summation may be approximately equal to total inputs if water levels stay constant; a shift in any of those can alter the equilibrium balance12,13. Understanding surface evaporation rates can help close the water balance equation and inform decision-makers on how to manage abstraction and movement of water from these bodies10,14–16. For instance, water managers may have multiple interconnected reservoirs in their purview, and may be able to move water from one reservoir to the next if that can enable them to reduce evaporative loss17–20.

Measuring open water evaporation is challenging for two primary reasons: (1) instrumentation; and, (2) representation1,16. It is difficult to set up and maintain in situ evaporation equipment in the middle of an unstable water body21–24. Eddy covariance assumptions about stability and fetch are often ill-constrained25, Bowen ratio approaches lose temporal fidelity26, and bulk aerodynamic or mass transfer methods are sensitive to user-(mis)calibration27. Further, most methods are indirect estimates of evaporation. Related, representation of point measurements to the larger water body is often error-prone as evaporation rates vary widely across the body depending on underlying bathymetry—and associated radiative storage and cycling—and exposure to varying wind and humidity especially from on-shore28–30.

Remote sensing has the potential to overcome the spatial representation problem, especially given high spatial resolution measurements of surface temperature31,32. Such resolution not only can identify spatial variability in evaporation, but also dynamically changing surface area related to water height and subsequent volumetric water loss33. In conjunction with high frequency in situ measurements, this combination can be a powerful pair both to produce a fused spatiotemporal capability, as well as provide calibration of the satellite data9,34. Still, there are challenges with remotely based evaporation estimates both in terms of retrieval mathematical formulation and physical process assumptions, as well as available data to drive those models35–37. Numerous models have been developed to estimate open water evaporation38–46.

Here, we are motivated by NASA’s ECOSTRESS mission, which now operationally produces open water evaporation data over millions of water bodies47 using the AquaSEBS approach45 in the global evapotranspiration (ET) product (L3_ET_PT-JPL)32. Initially in data Collection 1, ECOSTRESS masked out water bodies because the open water evaporation algorithm had not been evaluated. The analysis that went into this paper provided confidence in the open water evaporation data48, which are now un-masked in Collection 2. Because back-processing of the ECOSTRESS Collection 2 data takes a long time (e.g., > 1 year) and were consequently unavailable, we evaluated the ECOSTRESS open water evaporation algorithm using MODIS and Landsat data here. Moreover, PT-JPL with AquaSEBS is a core model in the OpenET system, including the open water evaporation component, which is linked to the ECOSTRESS implementation49. Our primary objective here is to establish the dataset and approach, and provide a first initial evaluation (Stage 1) of the AquaSEBS open water evaporation model as implemented in both ECOSTRESS and OpenET. We compiled in situ data from 19 sites from around the world, making this paper one of the largest evaluations of remotely sensed terrestrial open water evaporation to date. We also benchmarked AquaSEBS against a suite of 11 machine learning approaches to determine what the best accuracy is for a calibrated and optimized statistical model. This paper establishes a foundation on which subsequent analyses may be done with ECOSTRESS and OpenET data and provides an important reference for science investigations that use the open water evaporation data.

Methods

Data: in situ

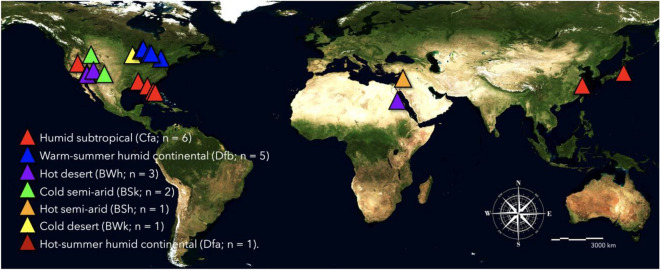

In situ measurements and estimates of open water evaporation and ancillary data were collected from sample size (n) 19 sites from around the world (Fig. 1). The sites included reservoirs and lakes of varying sizes and seven different Köppen-Geiger climate zones50: humid subtropical (Cfa; n = 6), warm-summer humid continental (Dfb; n = 5), hot desert (BWh; n = 3), cold semi-arid (BSk; n = 2), hot semi-arid (BSh; n = 1), cold desert (BWk; n = 1), and hot-summer humid continental (Dfa; n = 1). Data were obtained from the Great Lakes Evaporation Network (GLEN) (superiorwatersheds.org/GLEN)21,29, the US Bureau of Reclamation’s Open Water Evaporation Network (OWEN) (owen.dri.edu)51, data in Zhao and Gao9, as well as primary data collected by us52 (Table 1). Data contained within these sources (especially Zhao and Gao9) contain compilations of data from other studies as well22,53–64. Measurement techniques varied across sites including eddy covariance (n = 11), Bowen ratio energy balance (n = 5), bulk mass transfer (n = 2), and floating evaporation pan (n = 1). Ultimately, each site was handled consistently in comparisons despite differences in measurement technique and processing. Data spanned the years 1986 to 2019.

Figure 1.

In situ terrestrial open water evaporation data from 19 sites around the world were used to validate the remote sensing data. QGIS version 3.18 and Microsoft PowerPoint version 16.72 were used to add map elements to the figures.

Table 1.

List of 19 validation sites for in situ open water evaporation data.

| Site | Latitude | Longitude | Climate | Method | Sample rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Falls | 42.899761 | −112.75799 | Bsk | Bulk mass transfer | 30 min |

| Calm | 28.142088 | −82.582044 | Cfa | BREB | Monthly average |

| Cochiti | 35.616928 | −106.31541 | Bsk | Floating evaporation pan | 1 h |

| Five-O | 30.42177 | −85.664162 | Cfa | BREB | Monthly average |

| Granite Island | 46.7207104 | −87.413556 | Dfb | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

| Kasumigaura | 36.0430556 | 140.411667 | Cfa | Eddy covariance | Monthly average |

| Kinneret | 32.8166667 | 35.6 | Bsh | BREB | Monthly average |

| Lahontan | 39.4501944 | −119.06874 | Bwk | Bulk mass transfer | 30 min |

| Long Point | 42.56667 | −80.05 | Dfb | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

| Mead | 36.0834882 | −114.78053 | Bwh | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

| Mohave | 35.4272222 | −114.64806 | Bwh | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

| Nasser | 23.953539 | 32.877671 | Bwh | BREB | Monthly average |

| Ross Barnett | 32.43823 | −90.03168 | Cfa | Eddy covariance | Monthly average |

| Spectacle Reef | 45.77581 | −84.135914 | Dfb | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

| Stannard Rock | 47.18361 | −87.225 | Dfb | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

| Starr | 27.956697 | −81.588115 | Cfa | BREB | Daily average |

| Taihu | 31.382029 | 120.195508 | Cfa | Eddy covariance | Monthly average |

| White Bear | 45.07703 | −92.98331 | Dfa | Eddy covariance | Monthly average |

| White Shoal | 45.77333 | −85.13667 | Dfb | Eddy covariance | 30 min |

The sites included reservoirs and lakes of varying sizes and seven different Köppen climate zones: humid subtropical (Cfa), warm-summer humid continental (Dfb), hot desert (BWh), cold semi-arid (BSk), hot semi-arid (BSh), cold desert (BWk), and hot-summer humid continental (Dfa). Measurement techniques varied (BREB: Bowen ratio energy balance), as well as sample rate of available data.

Data were available in different time units: (i) half-hourly (n = 9); (ii) hourly (n = 1); (iii) daily average (n = 1); and, (iv) monthly average (n = 8). Data were reported in different physical units as well. For half-hourly and hourly measurements, we converted them to match the units of the instantaneous overpass satellite data where needed, i.e., W·m−2. For daily and monthly data, we created daily and monthly satellite products from the instantaneous data (“Model: aquasebs water heat flux”). We did not construct new daily data for the sites with sub-daily data because of missing data. In situ data were filtered for bad quality flags as provided.

Data: satellite: Landsat and MODIS

We produced fine spatial resolution 30 m images of water evaporation using the Landsat Analysis Ready Dataset (ARD) Surface Temperature (ST) and Surface Reflectance (SR) products65. This record provides a historical analog to the 70 m surface temperature from ECOSTRESS, with the limitation that the overpass time from Landsat is consistently around 10:30 AM, whereas ECOSTRESS provides sampling throughout the day. Landsat 5, 7, and 8 were used to cover the in situ record from 1986 to 2019. The Landsat ARD ST product provides resampled 30 m images of atmospherically corrected surface temperature from the 120 m Landsat 5, 60 m Landsat 7, and 100 m Landsat 8 thermal infrared instruments. Albedo was estimated by applying near-to-broadband coefficients to the SR product66.

To expand the temporal data volume beyond the 8–16 day revisit of the Landsat satellites, we opted to include daily Terra MODIS data (~ 10:30 AM overpass) at 1 km as well and conduct a comparison between the two data sources, from 2000 to 2019. Surface temperature was taken from the daily 1 km MOD11A1 product67. Albedo was taken from the 16-day, 500 m MCD43A3 product, which processes the bi-directional reflectance function over a combination of MODIS Terra and Aqua images from a 16-day repeat orbit68. Near surface air temperature and humidity were derived from the MOD07_L2 product following Famiglietti, Fisher69. Aerosol optical thickness from MOD04_L2 and cloud optical thickness from MOD06_L2 were used to derive solar radiation. Satellite data were filtered for bad quality flags and clouds. For Landsat, because the data volume was much smaller than that for MODIS, we additionally visually inspected each image manually to confirm success of the cloud filtering.

For the half-hourly and hourly data in situ data, the data point closest in time to satellite overpass was selected for comparison, accounting for differences in satellite overpass times. To capture some of the in situ fetch and to reduce any potential pixel noise, we calculated spatial aggregates of pixels at each of the in situ geographic coordinates and compared these aggregates to the single pixel overlying each site center point32. We note that a more sophisticated approach would be to conduct a temporally dynamic footprint-aware analysis for each site70–73, and adjust the corresponding pixels accordingly; the absence of this approach may reduce the goodness of fit in some instances74. Landsat was re-sampled to 30 m and a 5-by-5 pixels area of 150 m × 150 m was used for each site. MODIS, at a much coarser resolution, was limited in the area of extrapolation; we assessed a 3-by-3 pixels area for MODIS where possible. We screened for land intrusion through manual comparison to high resolution Google Earth RGB imagery. For each spatial aggregate, we calculated the mean, median, and interquartile range. We identified the optimal combination of spatial representation and statistical aggregate per site32.

Model: AquaSEBS water heat flux

We used the AquaSEBS model to estimate the water heat flux, (W·m−2)45:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

where is water surface temperature (°C); is near surface air dew point temperature (°C); is wind speed (m·s−1); and, is net shortwave radiation (W·m−2). represents a wind function (m·s−1); represents a thermal exchange coefficient (W·m−2·°C−1); and, represents a hypothetical equilibrium temperature (°C) when the net heat flux exchange between the water surface and the atmosphere equals zero. Formulation, definitions, and nomenclature match Abdelrady, Timmermans45 here for consistency.

was used in the Priestley–Taylor75 equation to calculate total evaporation, (W·m-2):

| 7 |

where is the Priestley–Taylor coefficient of 1.26 (unitless), is the slope of the saturation-to-vapour pressure curve, dependent on near surface air temperature (; °C) and water vapour pressure (; kPa), is the psychrometric constant (0.066 kPa·°C−1), and is net radiation (W·m−2).

Landsat and MODIS (and ultimately ECOSTRESS) provide . can be obtained from MODIS69, weather stations, or reanalysis. can be obtained from weather stations or reanalysis. can be obtained from MODIS, weather stations, or reanalysis. For MODIS-based modeling, we used MODIS for , , and following the ECOSTRESS Collection 1 retrieval for evapotranspiration for the global product (L3_ET_PT-JPL)32 with temporal upscaling for daily estimates following Verma, Fisher76; and, from the NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis I dataset at 6-hourly, 2.5° resolution (psl.noaa.gov)77. Specifically, was retrieved using the Forest Light Environmental Simulator (FLiES)78,79 and Breathing Earth System Simulator (BESS)80–82. Downwelling shortwave radiation () was calculated from eight inputs: (1) solar zenith angle; (2) aerosol optical thickness at 550 nm; (3) cloud optical thickness; (4) land surface albedo; (5) cloud top height; (6) atmospheric profile type; (7) aerosol type; and, (8) cloud type81. Upwelling shortwave radiation () was calculated from broadband surface albedo, which integrates black and white sky albedo, and . For Landsat-based modeling, we used , , humidity, and from NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis I.

The remotely sensed open water evaporation was produced as instantaneous at the time of overpass. However, some of the in situ data were available only as daily sums. As such, we produced an additional daily total remotely sensed evaporation product following the ECOSTRESS Collection 1 approach for the daily PT-JPL evapotranspiration product83. Specifically, diurnal incoming net radiation was sinusoidally modeled based on date and latitude, and the evaporative fraction ratio between the instantaneous evaporation and net radiation was carried forward throughout the day84. For brevity, we refer further details of these equations to Fisher83 and Bisht, Venturini84. To compare to those sites providing only monthly sums, we averaged all daily satellite data for a given month to make respective comparisons. We note that ECOSTRESS switches to AquaSEBS when the MODIS land/water mask is water.

Model: machine learning

We ran a suite of 11 machine learning models to determine what the best accuracy was for a given calibrated and optimized non-mechanistic model. This creates a benchmark to differentiate error between AquaSEBS and the in situ data that can be attributed to the remote sensing or the in situ data. For example, if AquaSEBS explained 50% of the variation in the in situ data, and the best machine learning model predicted 60%, then this suggests that AquaSEBS predicted most of the explainable variation. Secondarily, we also used the machine learning models to predict the error.

The models used were: (I) Ordinary Least Squares; (II) Ridge Regression; (III) LASSO; (IV) Elastic Net; (V) Multilayer Perceptron; (VI) Tensorflow Neural Network; (VII) Decision Tree; (VIII) Random Forest; (IX) Support Vector Machine; (X) K-Nearest Neighbors; and, (XI) Gradient Boosting85–94. We created a testing harness to train and fine tune multiple models simultaneously using Sklearn in Python95. Statistics on model performance and hyperparameter grid search for optimal hyperparameters were automatically saved; k-fold cross validation was used in conjunction with grid search96. Under/over fitting and convergence were tracked through loss and learning curve plots97. Preprocessing the data for machine learning required additional manual flagging of extended periods (> 2 weeks) of missing data. Data also required min–max scaling prior to ingestion into these models.

Software packages

Python version 3.9.5 was used to process all data, run the machine learning models, and produce the map figures and machine learning scatterplot. Microsoft Excel version 16.72 was used to verify the statistics and improve the aesthetics of the validation scatterplots. QGIS version 3.18 was used to add map elements to the figures and Microsoft PowerPoint version 16.72 was used to add aesthetic improvements to the maps.

Results

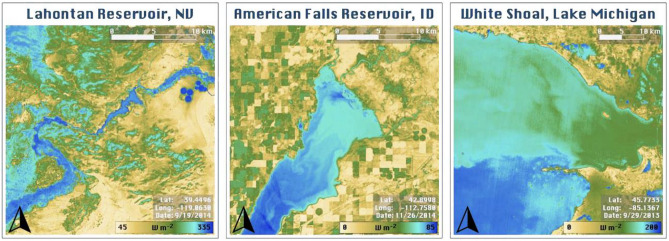

We produced 30 m landscape-scale maps of open water evaporation (AquaSEBS) and land evapotranspiration (PT-JPL) from Landsat over the 19 validation sites. The high spatial resolution and surface temperature sensitivity uncovered dynamic spatial patterns in evaporation across the reservoirs and lakes (Fig. 2). These patterns encompassed near shore changes related to bathymetry, north–south/east–west gradients across the water bodies, and circulation-based patterns as heat distributes via currents. Open water evaporation was typically larger than land evapotranspiration even in irrigated or mountainous settings during late summer and fall periods.

Figure 2.

High spatial resolution (30 m Landsat) and surface temperature sensitivity of AquaSEBS reveals dynamic spatial patterns in evaporation across reservoirs and lakes. These patterns encompass near shore changes related to bathymetry, north–south or east–west gradients across the water bodies, and circulation-based patterns as heat distributes via currents. Here, three examples are shown for Lahontan Reservoir, Nevada (left); American Falls Reservoir, Idaho (middle); and, White Shoal, Lake Michigan (right). Python version 3.9.5 was used to process all data and produce the map figures. QGIS version 3.18 was used to add map elements to the figures.

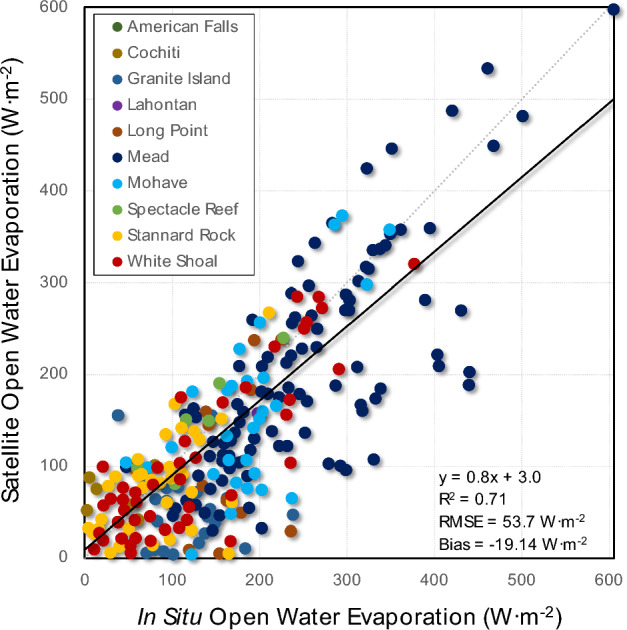

The bulk of the remotely sensed data used for validation against half-hourly and hourly in situ data came from MODIS given its daily cadence. 11,016 images aligned with the available in situ data, which was filtered down to 686 cloud-free scenes. For the available in situ daily and monthly data, 52 cloud-free scenes were available. For the MODIS instantaneous data only with high wind filtering (u > mean daily 7.5 m·s-1), the remote sensing data captured the variability in the open water evaporation reasonably well (r2 = 0.71; RMSE = 53.7 W·m-2; RMSE = 38% of mean; Bias = -19.1 W·m-2; Bias = 13% of mean) (Fig. 3). As this is a single model (AquaSEBS) run universally across all 19 sites, this bodes well for robust extrapolation beyond the sites, which vary widely in physical and environmental characteristics.

Figure 3.

Validation of remotely sensed instantaneous open water evaporation from AquaSEBS with MODIS against in situ measurements.

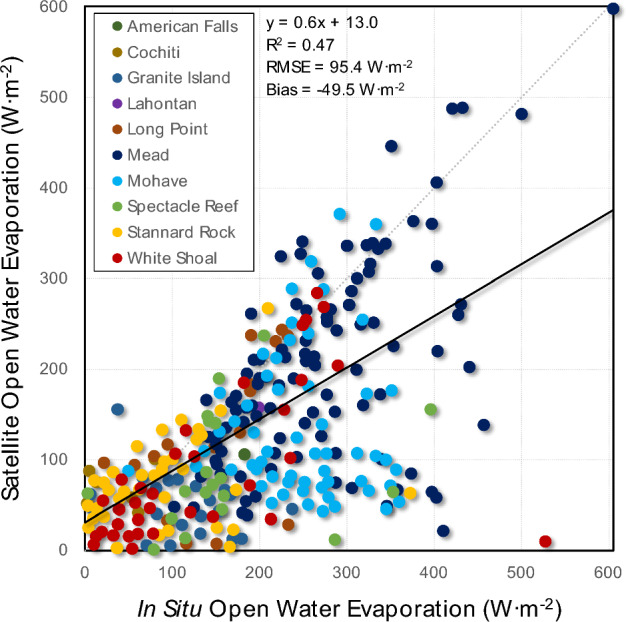

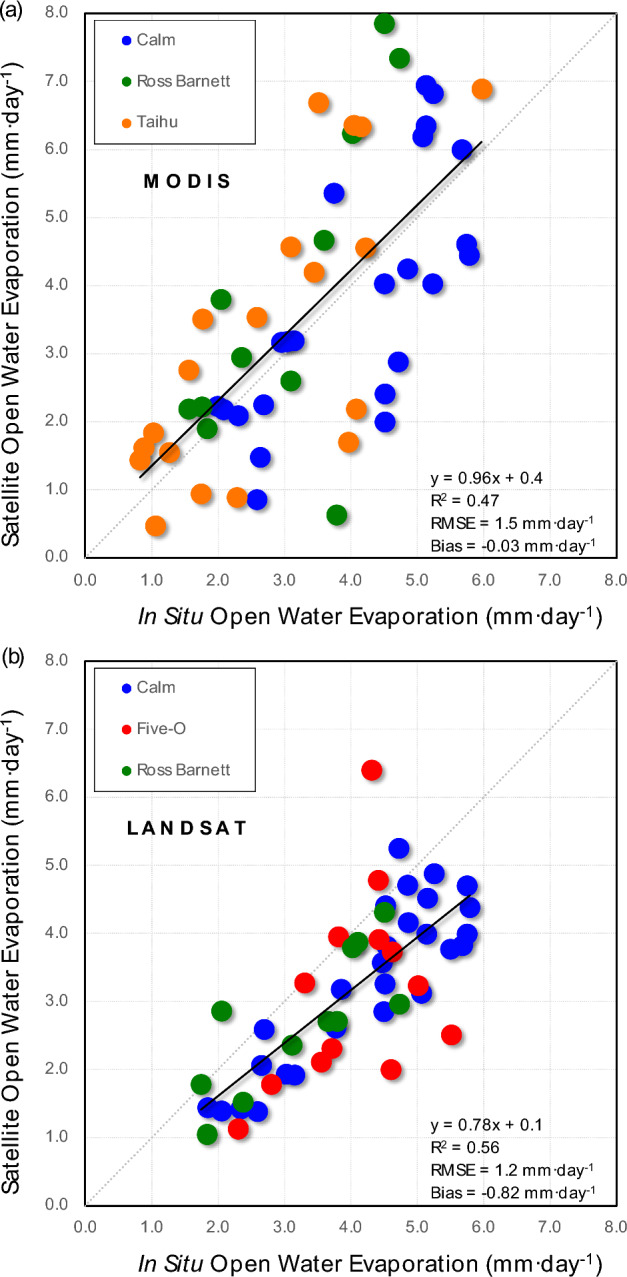

However, the instantaneous results were particularly sensitive to short-term high wind events. Failure to account for these events resulted in missed high evaporation moments (r2 = 0.47; RMSE = 84.4 W·m−2; RMSE = 62% of mean; Bias = −49.5 W·m−2; Bias = 36% of mean) (Fig. 4). Nonetheless, the daily results are not as sensitive to these high wind events; in fact, the Bias and RMSE were remarkably small, although the scatter was still large given the small sample size (r2 = 0.47; RMSE = 1.5 mm·day−1; RMSE = 41% of mean; Bias = 0.19 mm·day−1; Bias = 1% of mean) (Fig. 5a).

Figure 4.

All raw unfiltered data showed high in situ instantaneous open water evaporation associated with high wind events.

Figure 5.

Remotely sensed daily open water evaporation data compared well with in situ data available from a limited number of sites. The daily data were less sensitive to high wind events. Results were similar between MODIS (a) and Landsat (b), though the scatter improved with the higher spatial resolution of Landsat.

We next asked what the change in accuracy is with increasing spatial resolution from MODIS to Landsat. Although the sample size was small and the comparison was not 1-to-1, it appeared that there may be a modest increase in correlation with Landsat; RMSE and Bias remained relatively low though larger than that of MODIS (r2 = 0.56; RMSE = 1.2 mm·day−1; RMSE = 38% of mean; Bias = −0.8 mm·day−1; Bias = 26% of mean) (Fig. 5b). The small sample size was sensitive to outliers; the three outlier points in the Five-O data caused a reduction in r2 from 0.71 to 0.56.

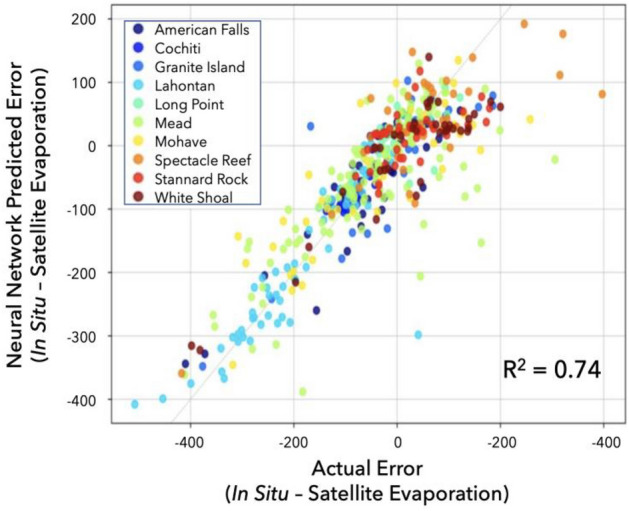

The top performing machine learning models were: (1) Multilayer Perceptron; (2) Elastic Net; (3) LASSO; (4) Ridge Regression; and, (5) TensorFlow Neural Network. However, none of the machine learning models outperformed AquaSEBS, which provides confidence for AquaSEBS and its application beyond the validation sites. Nonetheless, the machine learning models outperformed basic multiple linear regression and residual analyses in predicting AquaSEBS error (Table 2). Although error predictability varied from site to site, generally wind speed was the predominant predictor of open water evaporation error at most, but not all, sites and mostly only for the instantaneous/half-hourly/hourly data. The TensorFlow Neural Network with two hidden layers, 256 neurons at each hidden layer, dropout of 0.5 added after each layer, 0.001 regularization alpha, an Adam optimizer, ReLU for the dense layers activation function, and a loss function of mean absolute error was able to capture with reasonable speed a large amount of the variability in open water evaporation error (r2 = 0.74) (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Simple ordinary least squares linear regression analysis of ancillary predictors of error in remotely sensed open water evaporation relative to in situ measurements highlights the sensitivity to wind speed.

| Variable | Coef | Std err | t | P >|t| | [0.025 | 0.975] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air temperature (Celsius) | −2.00 | 1.54 | −1.30 | 0.19 | −5.03 | 1.02 |

| Net radiation (W·m−2) | −0.05 | 0.04 | −1.19 | 0.24 | −0.14 | 0.03 |

| Relative humidity (%) | −1.56 | 0.40 | −3.92 | 0.00 | −2.34 | −0.77 |

| Water vapor density (g·m−3) | 4.69 | 2.61 | 1.80 | 0.07 | −0.45 | 9.82 |

| Wind direction (°) | 0.14 | 0.06 | 2.40 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.26 |

| Wind speed (m·s−1) | 20.10 | 1.81 | 11.13 | 0.00 | 16.55 | 23.66 |

Significant values are in bold.

Figure 6.

A neural network (TensorFlow) predicted error in instantaneous satellite vs. in situ open water evaporation mismatch capturing 74% of variability.

Discussion

AquaSEBS is a relatively new model and has been used in only a few studies thus far. Abdelrady, Timmermans45, who developed AquaSEBS, reported RMSE’s of 20–35 W·m−2 and 1.5 mm·day−1, depending on site and measurement method; they reported a high r2 of 0.98 at one site though the r2 for their sensible heat flux was 0.70. Rodrigues, Costa98 and Rodrigues, Costa37 used AquaSEBS across multiple sites and reported RMSE’s of 0.81–1.25 mm·day−1 in the former and 0.03–0.58 mm·day−1 in the latter, with r2’s of 0.51–0.65 and 0.32–0.63, respectively. Our results compare similarly to all these studies (outside of the anomalous high r2 in Abdelrady, Timmermans45). Our instantaneous RMSE was a little larger than Abdelrady, Timmermans45 at 53.7 W·m−2, but our daily RMSE’s of 1.2–1.5 mm·day−1 compare similarly to the 1.5 mm·day−1 of Abdelrady, Timmermans45 and the high end of 1.25 mm·day−1 from Rodrigues, Costa98.

What are the sources of error in the model-data mismatch? Although we often attribute errors entirely to the model, the error is in fact a combination of multiple sources including: (1) the model; (2) the in situ data; (3) the forcing data; (4) scale mismatch; and, (5) user error35,36. In situ measurement of open water evaporation is challenging, as described in the Introduction; therefore, some of the model-data mismatch is due to the in situ validation data alone. Error characterization of these measurements is also challenging, and there have been numerous community efforts and controversies to make these systematic99–103.

Similarly, model forcing data have inherent uncertainties and errors that propagate through to the final model error104–108. Related, the model forcing data and final model output may be of a coarser spatial resolution than the footprint of the in situ measurements. So, the model may be “seeing” fluxes, surface, and meteorological features not captured by the in situ measurements; or, the pixels may be fine resolution, but the in situ fetch footprint is dynamic in space and time not aligned with the pixel analysis32,70–73. For instance, horizontally or laterally advected air, energy, and moisture can lead to both contamination in in situ measurements as well as remote sensing pixels49,106,109,110. For our validation, we accounted for it by a combination of: (A) placement of in situ measurements far from shore; and, (B) selection of pixels far from shore. This minimized bias from wind direction; we find no significant biases by waterbody area or shape (Table 2). However, beyond the validation, pixels at sharp wet/dry boundaries, especially in arid areas, will likely be impacted by advection49,106,110.

Temporal aggregation is another source of scale mismatch error, which is particularly acute when comparing instantaneous remotely sensed estimates to daily or monthly in situ data82,111. Such temporal mismatches, in turn, circle back to controls on the open water evaporation process and how they are represented in the model formulation. If additional model capabilities, such as machine learning approaches to predict and integrate many of these ill-constrained error sources (e.g., Fig. 6), can be combined with the process model, then there may be avenues for improving the uncertainty of remotely sensed estimates of open water evaporation.

Taken together, these challenges and limitations in both model-data mismatch and site representation present some opaqueness with understanding how accurate our remotely sensed open water evaporation data are globally. Our validation sites, while among the largest open water validate site collections to date, are not globally representative, lacking important low- and high-latitudes (and altitudes)112,113. Nonetheless, we chose to proceed with this collection as a critical step forward in understanding the accuracy of our data but recognize that there are more steps to be had in future analyses. On the other hand, the net gain of insight from this analysis far outweighs these limitations, making these results a significant contribution to the scientific literature.

Penman44 described and formulated evaporation from open water over a lifetime ago. Since then, multiple papers have described and synthesized how the controls on open water evaporation are not static but vary in space and time1,12,114. Still, study of terrestrial open water evaporation has been overshadowed by much more work done on evapotranspiration from land and plants115 or implicitly subsumed into analyses of pan evaporation116. Studies of ocean evaporation have been mature with low uncertainties having been reported for decades117–121. However, the processes controlling open water evaporation from reservoirs and lakes, while perhaps not different in name from those controlling land and plant evapotranspiration, have notably distinctive sensitivities and impacts on open water evaporation. Certainly, standard variables of radiation, humidity, wind, and air and surface temperature control both evaporation processes122,123. Plants and land introduce additional surface, aerodynamic, and stomatal resistances, as well as varying access to water110,124. But, open water introduces much deeper radiation-absorbing characteristics than do plants and land that ultimately manifest in evaporation, though not necessarily immediately or even in the same location, as heat is circulated throughout the water body12,125. These characteristics are, in turn, strongly determined by the physical structure of the water holding landform and associated underlying bathymetry1. Open water may be more sensitive to wind events than in forested ecosystems, which provide some physical structural buffering126. Indeed, open water evaporation may be near zero even on the hottest and driest day if there is no wind127. Still, evaporation formulations that incorporate wind speed are highly vulnerable to uncertainties in wind speed measurements105. Salinity may impact predictive capacities in both systems45,128. Ultimately, radiation continues to be the dominant driver of both land and open water evaporation at large space and time scales; but, the process shifts to atmospherically-controlled at short time scales32,129–131.

The future of remotely sensed terrestrial open water evaporation is promising with new missions emerging that increase the spatial resolution and frequency of surface temperature measurements, and operational data products including open water evaporation over millions of water bodies. The Landsat record continues to be supported with regular launches to replace aging satellites132. ECOSTRESS has increased the temporal resolution to 1–5 days with diurnal sampling32. SBG, TRISHNA, and LSTM will provide consistent, high quality, and well-calibrated surface temperature measurements every 3 days133–135. Hydrosat will provide the highest spatiotemporal surface temperature measurements at 50 m, daily, multiple times per day136–138. In a very complementary approach, radar measurements from SWOT will enable monitoring of changes in reservoir and lake water height levels, at least for large water bodies139. Synergies among all these missions, in conjunction with operational open water evaporation data production, can provide a step-change in our ability to estimate and monitor open water evaporation. Moreover, synergies with operational meteorological reanalyses and forecasting agencies and datasets enable diurnally integrated open water evaporation accounting from the instantaneous remote sensing measurements49. While reanalysis can provide fine scale temporal information, remote sensing can provide fine scale spatial measurements that can also be used to downscale the coarse reanalysis pixels140. Together, these tools can complement and build on foundational work done by Zhao, Li2 characterizing 1.42 million lakes globally, and beyond. Finally, bottom-up support of in situ monitoring networks such as GLEN21,29, OWEN51, the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON)141, the Western Reservoir Evaporation Network (WREN)1, and AmeriFlux/FLUXNET142 is necessary to provide and expand the validation and diurnal scaling as these satellite data come online.

Conclusion

Here, we conducted the first evaluation of the AquaSEBS open water evaporation model as implemented in the ECOSTRESS mission and OpenET, applied to MODIS and Landsat data across 19 sites from around the world, making it among the largest open water validations to date. Our paper provides the foundational reference of preliminary results that provide confidence in the model and data, which enable both ECOSTRESS and OpenET to move forward with operational production and public releases of these data, and by which further research can build off. As those data begin to be produced, this evaluation should be re-visited with the new data across more sites. Moreover, further investigation is warranted to increase the sophistication from this analysis, particularly with incorporation of approaches to reduce uncertainties. These range from improving the quantification of the in situ data error and dynamic footprints to integration with machine learning techniques to predict error. There continues to be scope for improving the mechanistic formulation of the open water evaporation process within AquaSEBS with respect to environmental sensitivities and temporal dynamics for future data production collections and expanded validation sites. Synergies with upcoming missions from SBG, TRISHNA, LSTM, and Hydrosat, as well as SWOT, in conjunction with expanded and standardized in situ networks will be key to ensuring water management and analysis of changes in climate and hydrological cycling best leverage these data as such operational information becomes increasingly important into the future.

Acknowledgements

The research was carried out in part at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80NM0018D0004). California Institute of Technology. Research was also carried out at the Desert Research Institute. Government sponsorship acknowledged. Funding was provided in part by OpenET partners and philanthropies, the U.S. Geological Survey Landsat Science Team (140G0118C0007), NASA’s ECOSTRESS program, and NASA’s WATER program. Copyright 2023. All rights reserved. Eddy covariance data used in this research were kindly provided by the Great Lakes Evaporation Network (GLEN), with data compilation and publication provided by LimnoTech under Award/Contract No. 10042-400759 from the International Joint Commission (IJC) through a sub-contract with the Great Lakes Observing System (GLOS). The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of GLEN, LimnoTech, the IJC, or GLOS. Two anonymous reviewers provided useful comments.

Author contributions

J.B.F. and G.H.H. formulated idea; J.B.F. and G.H.H. designed research; M.B.D. and G.H.H. performed research; J.W.C., C.P., and J.L.H. provided data; all authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Data availability

The satellite datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the LP DAAC AppEEARS tool: lpdaac.usgs.gov/tools/appeears. The reanalysis data are available from: psl.noaa.gov. The in situ data were manually compiled and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Friedrich K, et al. Reservoir evaporation in the Western United States: Current science, challenges, and future needs. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018;99(1):167–187. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00224.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao G, et al. Evaporative water loss of 1.42 million global lakes. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):3686. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31125-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider P, Hook SJ. Space observations of inland water bodies show rapid surface warming since 1985. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010;37:22. doi: 10.1029/2010GL045059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Reilly CM, et al. Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015;42(24):10773–10781. doi: 10.1002/2015GL066235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenters JD, Kratz TK, Bowser CJ. Effects of climate variability on lake evaporation: Results from a long-term energy budget study of Sparkling Lake, northern Wisconsin (USA) J. Hydrol. 2005;308(1–4):168–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2004.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian W, et al. Estimation of global reservoir evaporation losses. J. Hydrol. 2022;607:127524. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, et al. Global lake evaporation accelerated by changes in surface energy allocation in a warmer climate. Nat. Geosci. 2018;11(6):410–414. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0114-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh A, et al. On the desiccation of the South Aral Sea observed from spaceborne missions. Remote Sens. 2018;10(5):793. doi: 10.3390/rs10050793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao G, Gao H. Estimating reservoir evaporation losses for the United States: Fusing remote sensing and modeling approaches. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019;226:109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivapragasam C, et al. Modeling evaporation-seepage losses for reservoir water balance in semi-arid regions. Water Resour. Manag. 2009;23(5):853–867. doi: 10.1007/s11269-008-9303-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher JB, et al. The future of evapotranspiration: Global requirements for ecosystem functioning, carbon and climate feedbacks, agricultural management, and water resources. Water Resour. Res. 2017;53(4):2618–2626. doi: 10.1002/2016WR020175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenters, J. et al. Physical controls on lake evaporation across a variety of climates and lake types. in 17th International Workshop on Physical Processes in Natural Waters (2014).

- 13.Myrup L, et al. Climatological estimate of the average monthly energy and water budgets of Lake Tahoe California-Nevada. Water Resour. Res. 1979;15(6):1499–1508. doi: 10.1029/WR015i006p01499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winter TC. Uncertainties in estimating the water balance of lakes. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1981;17(1):82–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-1688.1981.tb02593.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gronewold AD, et al. Reconciling the water balance of large lake systems. Adv. Water Resour. 2020;137:103505. doi: 10.1016/j.advwatres.2020.103505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Bureau of Reclamation. Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study. (Executive Summary, 2012).

- 17.Fornarelli R, Antenucci JP. The impact of transfers on water quality and the disturbance regime in a reservoir. Water Res. 2011;45(18):5873–5885. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman DJ. More reservoirs or transfers? A computable general equilibrium analysis of projected water shortages in the Arkansas River Basin. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2000;25:698–713. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng X, et al. Water transfer triggering mechanism for multi-reservoir operation in inter-basin water transfer-supply project. Water Resour. Manag. 2014;28(5):1293–1308. doi: 10.1007/s11269-014-0541-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zand AD, Khalili-Damghani K, Raissi S. Designing an intelligent control philosophy in reservoirs of water transfer networks in supervisory control and data acquisition system stations. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 2021;18(5):694–717. doi: 10.1007/s11633-021-1284-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanken PD, et al. Evaporation from lake superior: 1. Physical controls and processes. J. Great Lakes Res. 2011;37(4):707–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2011.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreo, M., Evaporation Data from Lake Mead and Lake Mohave, Nevada and Arizona, March 2010 Through April 2015. Vol. 10. F79C6VG3. 10.5066/F79C6VG3 (US Geological Survey, 2015).

- 23.Liu H, et al. Variability in cold front activities modulating cool-season evaporation from a southern inland water in the USA. Environ. Res. Lett. 2011;6(2):024022. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/6/2/024022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe LD, et al. Evaporation from water supply reservoirs: An assessment of uncertainty. J. Hydrol. 2009;376(1–2):261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.07.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W, et al. An approximate footprint model for flux measurements in the convective boundary layer. J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech. 2006;23(10):1384–1394. doi: 10.1175/JTECH1911.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winter TC, et al. Evaporation determined by the energy-budget method for Mirror Lake, New Hampshire. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2003;48(3):995–1009. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.3.0995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brutsaert, W. Evaporation into the Atmosphere: Theory, History and Applications. Vol. 1. (Springer, 2013).

- 28.Rosenberry D, Sturrock A, Winter T. Evaluation of the energy budget method of determining evaporation at Williams Lake, Minnesota, using alternative instrumentation and study approaches. Water Resour. Res. 1993;29(8):2473–2483. doi: 10.1029/93WR00743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spence C, et al. Evaporation from Lake Superior: 2: Spatial distribution and variability. J. Great Lakes Res. 2011;37(4):717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jglr.2011.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishcha P, Starobinets B. Spatial heterogeneity in dead sea surface temperature associated with inhomogeneity in evaporation. Remote Sens. 2021;13(1):93. doi: 10.3390/rs13010093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiménez-Muñoz JC, et al. Land surface temperature retrieval methods from Landsat-8 thermal infrared sensor data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014;11(10):1840–1843. doi: 10.1109/LGRS.2014.2312032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher, J.B. et al. ECOSTRESS: NASA's Next Generation Mission to Measure Evapotranspiration from the International Space Station. Vol. 56(4). e2019WR026058 (Water Resources Research, 2020).

- 33.Rimmer A, et al. Mechanisms of long-term variations in the thermal structure of a warm lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011;56(3):974–988. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.3.0974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalma JD, McVicar TR, McCabe MF. Estimating land surface evaporation: A review of methods using remotely sensed surface temperature data. Surv. Geophys. 2008;29(4):421–469. doi: 10.1007/s10712-008-9037-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher JB, et al. Modeling the terrestrial biosphere. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014;39:91–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-012913-093456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badgley G, et al. On uncertainty in global terrestrial evapotranspiration estimates from choice of input forcing datasets. J. Hydrometeorol. 2015;16(4):1449–1455. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-14-0040.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodrigues IS, et al. Evaporation in Brazilian dryland reservoirs: Spatial variability and impact of riparian vegetation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;797:149059. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberry DO, et al. Comparison of 15 evaporation methods applied to a small mountain lake in the northeastern USA. J. Hydrol. 2007;340(3–4):149–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacKay MD, et al. Modeling lakes and reservoirs in the climate system. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009;54(62):2315–2329. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.6_part_2.2315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finch J, Gash J. Application of a simple finite difference model for estimating evaporation from open water. J. Hydrol. 2002;255(1–4):253–259. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00511-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McJannet DL, Webster IT, Cook FJ. An area-dependent wind function for estimating open water evaporation using land-based meteorological data. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012;31:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paw K. Surface renewal analysis: A new method to obtain scalar fluxes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995;74:119–137. doi: 10.1016/0168-1923(94)02182-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mengistu M, Savage M. Open water evaporation estimation for a small shallow reservoir in winter using surface renewal. J. Hydrol. 2010;380(1–2):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penman HL. Natural evaporation from open water, bare soil and grass. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. 1948;193:120–146. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1948.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdelrady A, et al. Surface energy balance of fresh and saline waters: AquaSEBS. Remote Sens. 2016;8(7):583. doi: 10.3390/rs8070583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher JB, Whittaker RH, Malhi Y. ET Come Home: A critical evaluation of the use of evapotranspiration in geographical ecology. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011;20:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00578.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Downing JA, et al. The global abundance and size distribution of lakes, ponds, and impoundments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2006;51(5):2388–2397. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dohlen, M. et al. Remotely sensed open water reservoir and lake evaporation. in AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (2019).

- 49.Melton F, et al. OpenET: Filling the biggest data gap in water management for the Western United States. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022;58(6):971–994. doi: 10.1111/1752-1688.12956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007;11(5):1633–1644. doi: 10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spears, M., Huntington, J. & Gangopadhyay, S. Improving Reservoir Evaporation Estimates.https://www.usbr.gov/research/projects/detail.cfm (2016).

- 52.Collison JW. The Collison Floating Evaporation Pan: Design, Validation, and Comparison. The University of New Mexico; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elsawwaf M, et al. Evaporation estimates from Nasser Lake, Egypt, based on three floating station data and Bowen ratio energy budget. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 2010;100(3):439–465. doi: 10.1007/s00704-009-0168-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin X, Nicholson SE, Ba MB. On the diurnal cycle of cloudiness over Lake Victoria and its influence on evaporation from the lake. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2000;45(3):407–424. doi: 10.1080/02626660009492338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vallet-Coulomb C, et al. Lake evaporation estimates in tropical Africa (lake Ziway, Ethiopia) J. Hydrol. 2001;245(1–4):1–18. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00341-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rimmer A, Samuels R, Lechinsky Y. A comprehensive study across methods and time scales to estimate surface fluxes from Lake Kinneret, Israel. J. Hydrol. 2009;379(1–2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang W, et al. Temporal and spatial variations in radiation and energy balance across a large freshwater lake in China. J. Hydrol. 2014;511:811–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sugita M, et al. Evaporation from Lake Kasumigaura: Annual totals and variability in time and space. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2014;8(3):103–107. doi: 10.3178/hrl.8.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prata A. Satellite-derived evaporation from Lake Eyre, South Australia. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1990;11(11):2051–2068. doi: 10.1080/01431169008955160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu H, et al. Eddy covariance measurements of surface energy budget and evaporation in a cool season over southern open water in Mississippi. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009;114:D4. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu H, Zhang Q, Dowler G. Environmental controls on the surface energy budget over a large southern inland water in the United States: An analysis of one-year eddy covariance flux data. J. Hydrometeorol. 2012;13(6):1893–1910. doi: 10.1175/JHM-D-12-020.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abtew W. Evaporation estimation for Lake Okeechobee in south Florida. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2001;127(3):140–147. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(2001)127:3(140). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiao K, et al. Evaporation from a temperate closed-basin lake and its impact on present, past, and future water level. J. Hydrol. 2018;561:59–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.03.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sacks L, Lee T, Radell M. Comparison of energy-budget evaporation losses from two morphometrically different Florida seepage lakes. J. Hydrol. 1994;156(1–4):311–334. doi: 10.1016/0022-1694(94)90083-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Claverie M, et al. The Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 surface reflectance data set. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018;219:145–161. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2018.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang S. Narrowband to broadband conversions of land surface albedo I: Algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001;76(2):213–238. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(00)00205-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang W, Liang S, Meyers T. Validating MODIS land surface temperature products using long-term nighttime ground measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008;112(3):623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2007.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schaaf CB, et al. First operational BRDF, albedo nadir reflectance products from MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002;83(1–2):135–148. doi: 10.1016/S0034-4257(02)00091-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Famiglietti CA, et al. Global validation of MODIS near-surface air and dew point temperatures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018;45(15):7772–7780. doi: 10.1029/2018GL077813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chasmer L, et al. Characterizing vegetation structural and topographic characteristics sampled by eddy covariance within two mature aspen stands using lidar and a flux footprint model: Scaling to MODIS. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2011;116:G2. doi: 10.1029/2010JG001567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.DuBois S, et al. Using imaging spectroscopy to detect variation in terrestrial ecosystem productivity across a water-stressed landscape. Ecol. Appl. 2018;28(5):1313–1324. doi: 10.1002/eap.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Montaldo N, Oren R. The way the wind blows matters to ecosystem water use efficiency. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016;217:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu K, Metzger S, Desai AR. Upscaling tower-observed turbulent exchange at fine spatio-temporal resolution using environmental response functions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017;232:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2016.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rey-Sanchez C, et al. Evaluation of atmospheric boundary layer height from wind profiling radar and slab models and its responses to seasonality of land cover, subsidence, and advection. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021;126(7):e2020JD033775. doi: 10.1029/2020JD033775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Priestley CHB, Taylor RJ. On the assessment of surface heat flux and evaporation using large scale parameters. Mon. Weather Rev. 1972;100:81–92. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1972)100<0081:OTAOSH>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Verma M, et al. Global surface net-radiation at 5 km from MODIS Terra. Remote Sens. 2016;8(9):739. doi: 10.3390/rs8090739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kalnay E, et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1996;77(3):437–472. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Iwabuchi H. Efficient Monte Carlo methods for radiative transfer modeling. J. Atmos. Sci. 2006;63(9):2324–2339. doi: 10.1175/JAS3755.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kobayashi H, Iwabuchi H. A coupled 1-D atmosphere and 3-D canopy radiative transfer model for canopy reflectance, light environment, and photosynthesis simulation in a heterogeneous landscape. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008;112(1):173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2007.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ryu Y, et al. Integration of MODIS land and atmosphere products with a coupled-process model to estimate gross primary productivity and evapotranspiration from 1 km to global scales. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2011;25(4):GB4017. doi: 10.1029/2011GB004053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ryu Y, et al. MODIS-derived global land products of shortwave radiation and diffuse and total photosynthetically active radiation at 5 km resolution from 2000. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018;204:812–825. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2017.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ryu Y, et al. On the temporal upscaling of evapotranspiration from instantaneous remote sensing measurements to 8-day mean daily-sums. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012;152:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2011.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fisher, J. Level-3 Evapotranspiration L3 (ET_PT-JPL) Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document (ECOSTRESS). Vol. 3 (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 2018).

- 84.Bisht G, et al. Estimation of the net radiation using MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) Remote Sens. Environ. 2005;97:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2005.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Abadi, M. TensorFlow: Learning functions at scale. in Proceedings of the 21st ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Functional Programming (2016).

- 86.Gardner MW, Dorling S. Artificial neural networks (the multilayer perceptron)—A review of applications in the atmospheric sciences. Atmos. Environ. 1998;32(14–15):2627–2636. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00447-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 2005;67(2):301–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zou H. The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2006;101(476):1418–1429. doi: 10.1198/016214506000000735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dhillon PS, et al. A risk comparison of ordinary least squares vs ridge regression. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013;14(1):1505–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Safavian SR, Landgrebe D. A survey of decision tree classifier methodology. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1991;21(3):660–674. doi: 10.1109/21.97458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Belgiu M, Drăguţ L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2016;114:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2016.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suthaharan S. Machine Learning Models and Algorithms for Big Data Classification. Springer; 2016. Support vector machine; pp. 207–235. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Samet H. K-nearest neighbor finding using MaxNearestDist. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007;30(2):243–252. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2007.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bentéjac C, Csörgő A, Martínez-Muñoz G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021;54(3):1937–1967. doi: 10.1007/s10462-020-09896-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Komer B, Bergstra J, Eliasmith C. Automated Machine Learning. Springer; 2019. Hyperopt-sklearn; pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rodriguez JD, Perez A, Lozano JA. Sensitivity analysis of k-fold cross validation in prediction error estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2009;32(3):569–575. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rijn, J.N.V. et al. Fast algorithm selection using learning curves. in International Symposium on Intelligent Data Analysis. (Springer, 2015).

- 98.Rodrigues IS, et al. Trends of evaporation in Brazilian tropical reservoirs using remote sensing. J. Hydrol. 2021;598:126473. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Papale D, et al. Towards a standardized processing of net ecosystem exchange measured with eddy covariance technique: Algorithms and uncertainty estimation. Biogeosciences. 2006;3(4):571–583. doi: 10.5194/bg-3-571-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Falge E, et al. Gap filling strategies for long term energy flux data sets. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001;107(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1923(00)00235-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Foken T. The energy balance closure problem: An overview. Ecol. Appl. 2008;18(6):1351–1367. doi: 10.1890/06-0922.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fisher JB, et al. What the towers don't see at night: Nocturnal sap flow in trees and shrubs at two AmeriFlux sites in California. Tree Physiol. 2007;27(4):597–610. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.4.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Papale D, et al. Database maintenance, data sharing policy, collaboration. In: Aubinet M, Vesala T, Papale D, et al., editors. Eddy Covariance: A Practical Guide to Measurement and Data Analysis. Springer; 2012. pp. 399–424. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cawse-Nicholson K, et al. Sensitivity and uncertainty quantification for the ECOSTRESS evapotranspiration algorithm-DisALEXI. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020;89:102088. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fisher JB, et al. Evapotranspiration models compared on a Sierra Nevada forest ecosystem. Environ. Model. Softw. 2005;20(6):783–796. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2004.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fisher JB, Tu K, Baldocchi DD. Global estimates of the land-atmosphere water flux based on monthly AVHRR and ISLSCP-II data, validated at 16 FLUXNET sites. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008;112(3):901–919. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2007.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hansen LP. Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators. Econometrica. 1982;50(4):1029–1054. doi: 10.2307/1912775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Warnick KF, Chew WC. Error analysis of the moment method. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2004;46(6):38–53. doi: 10.1109/MAP.2004.1396735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang, T. et al. A duet of fluxes: Pursuing the dyadic advection of heat and moisture. in Fall Meeting 2022. (AGU, 2022).

- 110.Purdy AJ, et al. SMAP soil moisture improves global evapotranspiration. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018;219:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2018.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Colaizzi P, et al. Comparison of five models to scale daily evapotranspiration from one-time-of-day measurements. Trans. ASABE. 2006;49(5):1409–1417. doi: 10.13031/2013.22056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fisher JB, et al. Missing pieces to modeling the Arctic-Boreal puzzle. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018;13(2):020202. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa9d9a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fisher JB, et al. Nutrient limitation in rainforests and cloud forests along a 3,000-m elevation gradient in the Peruvian Andes. Oecologia. 2013;172(3):889–902. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Granger RJ, Hedstrom N. Modelling hourly rates of evaporation from small lakes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011;15(1):267–277. doi: 10.5194/hess-15-267-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Baldocchi D, et al. FLUXNET: A new tool to study the temporal and spatial variability of ecosystem-scale carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy flux densities. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2001;82(11):2415–2434. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(2001)082<2415:FANTTS>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Roderick ML, Farquhar GD. The cause of decreased pan evaporation over the past 50 years. Science. 2002;298(5597):1410–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.1075390-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Large W, Pond S. Sensible and latent heat flux measurements over the ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1982;12(5):464–482. doi: 10.1175/1520-0485(1982)012<0464:SALHFM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Robertson FR, et al. Uncertainties in ocean latent heat flux variations over recent decades in satellite-based estimates and reduced observation reanalyses. J. Clim. 2020;33(19):8415–8437. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0954.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gleckler PJ, Weare BC. Uncertainties in global ocean surface heat flux climatologies derived from ship observations. J. Clim. 1997;10(11):2764–2781. doi: 10.1175/1520-0442(1997)010<2764:UIGOSH>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stephens GL, et al. An update on Earth's energy balance in light of the latest global observations. Nat. Geosci. 2012;5(10):691–696. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Trenberth KE, Fasullo JT, Kiehl J. Earth's global energy budget. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2009;90(3):311–324. doi: 10.1175/2008BAMS2634.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Polhamus A, Fisher JB, Tu KP. What controls the error structure in evapotranspiration models? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013;169:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Baldocchi DD, et al. Atmospheric humidity deficits tell us how soil moisture deficits down-regulate ecosystem evaporation. Adv. Water Resour. 2022;159:104100. doi: 10.1016/j.advwatres.2021.104100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shuttleworth WJ, Wallace JS. Evaporation from sparse crops—An energy combination theory. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1985;111:839–855. doi: 10.1002/qj.49711146910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Purdy A, et al. Ground heat flux: An analytical review of 6 models evaluated at 88 sites and globally. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2016;121(12):3045–3059. doi: 10.1002/2016JG003591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kim D, et al. Sensitivity of stand transpiration to wind velocity in a mixed broadleaved deciduous forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014;187:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2013.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Collison, J.W. & Llewellyn, D. Deployment of the Collison Floating Evaporation Pan on Lake Powell, UT-AZ and Cochiti Lake, NM to Improve Evaporation Rate Measurement Accuracy and Precision. 1–187. (Bureau of Reclamation, 2021).

- 128.Katerji N, et al. Salinity and drought, a comparison of their effects on the relationship between yield and evapotranspiration. Agric. Water Manag. 1998;36(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3774(97)00049-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fisher JB, et al. The land-atmosphere water flux in the tropics. Glob. Change Biol. 2009;15:2694–2714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01813.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Brutsaert W. Radiation, evaporation and the maintenance of turbulence under stable conditions in the lower atmosphere. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1972;2(3):309–325. doi: 10.1007/BF02184772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jensen, M.E. & Haise, H.R. Estimating evapotranspiration from solar radiation. in Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers. J. Irrig. Drain. Div.89, 15–41 (1963).

- 132.Irons JR, Dwyer JL, Barsi JA. The next Landsat satellite: The Landsat data continuity mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012;122:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2011.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cawse-Nicholson K, et al. NASA's surface biology and geology designated observable: A perspective on surface imaging algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021;257:112349. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2021.112349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lagouarde, J.-P. et al. The Indian–French Trishna mission: Earth observation in the thermal infrared with high spatio-temporal resolution. in IGARSS 2018–2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. (IEEE, 2018).

- 135.Koetz, B. et al. High spatio-temporal resolution land surface temperature mission-a copernicus candidate mission in support of agricultural monitoring. in IGARSS 2018–2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. (IEEE, 2018).

- 136.Fisher, J.B. et al. Towards daily, field-scale, global thermal infrared measurements from space. in AGU Fall Meeting 2021. (AGU, 2021).

- 137.Lalli, K. & Soenen, S. Comparison of vicarious and on-board infrared calibration sources for small satellites. in CubeSats and SmallSats for Remote Sensing V. (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2021).

- 138.Farella MM, et al. Thermal remote sensing for plant ecology from leaf to globe. J. Ecol. 2022;110(9):1996–2014. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Fu L-L, et al. The SWOT (Surface Water and Ocean Topography) mission: Spaceborne radar interferometry for oceanographic and hydrological applications. Proc. OCEANOBS. 2009;9:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Colliander A, et al. Spatial downscaling of SMAP soil moisture using MODIS land surface temperature and NDVI during SMAPVEX15. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017;14(11):2107–2111. doi: 10.1109/LGRS.2017.2753203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hamilton DP, et al. A Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) for synthesising high-frequency sensor data for validation of deterministic ecological models. Inland Waters. 2015;5(1):49–56. doi: 10.5268/IW-5.1.566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Fisher JB, et al. Once upon a time, in AmeriFlux. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021;126(1):e2020JG006148. doi: 10.1029/2020JG006148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The satellite datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the LP DAAC AppEEARS tool: lpdaac.usgs.gov/tools/appeears. The reanalysis data are available from: psl.noaa.gov. The in situ data were manually compiled and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.