Abstract

RAS alterations are often found in difficult-to-treat malignancies and are considered “undruggable.” To better understand the clinical correlates and coaltered genes of RAS alterations, we used targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) to analyze 1,937 patients with diverse cancers. Overall, 20.9% of cancers (405/1,937) harbored RAS alterations. Most RAS-altered cases had genomic coalterations (95.3%, median: 3, range: 0–51), often involving genes implicated in oncogenic signals: PI3K pathway (31.4% of 405 cases), cell cycle (31.1%), tyrosine kinase families (21.5%) and MAPK signaling (18.3%). Patients with RAS-altered versus wild-type RAS malignancies had significantly worse overall survival (OS; p = 0.02 [multivariate]), with KRAS alterations, in particular, showing shorter survival. Moreover, coalterations in both RAS and PI3K signaling or cell-cycle-associated genes correlated with worse OS (p = 0.004 and p < 0.0001, respectively [multivariate]). Among RAS-altered patients, MEK inhibitors alone did not impact progression-free survival (PFS), while matched targeted therapy against non-MAPK pathway coalterations alone showed a trend toward longer PFS (vs. patients who received unmatched therapy) (HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.61–1.03, p = 0.07). Three of nine patients (33%) given tailored combination therapies targeting both MAPK and non-MAPK pathways achieved objective responses. In conclusion, RAS alterations correlated with poor survival across cancers. The majority of RAS alterations were accompanied by coalterations impacting other oncogenic pathways. MEK inhibitors alone were ineffective against RAS-altered cancers while matched targeted therapy against coalterations alone correlated with a trend toward improved PFS. A subset of the small number of patients given MEK inhibitors plus tailored non-MAPK-targeting agents showed responses, suggesting that customized combinations warrant further investigation.

Keywords: RAS, next-generation sequencing, targeted therapy

Introduction

Since the discovery of activating RAS mutations in 1982,1–3 further research in cancer genomics revealed that alterations in this gene family (KRAS, NRAS and HRAS) are among the most frequent in cancer, being discerned in about 20–30% of tumors.4–6 Single point mutations in the RAS gene lock the protein in a GTP-bound state, leading to constitutive activation of the Ras protein and persistent signaling in multiple downstream pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways.4 At the cellular level, oncogenic RAS alterations are also associated with increased anchorage-independent cell growth and implicated in cancer initiation and aggressiveness.7–10

Among different RAS alterations, KRAS is the isoform most frequently altered (86% of all RAS alterations), followed by NRAS (11%) and HRAS (3%).4,5 The frequency of alterations in RAS differs depending on the cancer type. For example, KRAS alterations are most commonly seen in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (71–98% of pancreatic adenocarcinoma) followed by colorectal adenocarcinoma (35–45%) and lung adenocarcinoma (19–31%). NRAS alterations are frequently observed in cutaneous melanoma (28%) followed by thyroid carcinoma (8–9%). HRAS alterations can be discerned in bladder urothelial carcinoma (6%), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (5%) and thyroid carcinoma (3–4%).4–6 Moreover, the frequencies of specific codon mutations in each RAS gene differ from cancer to cancer,5 and different codon mutations can lead to distinct downstream signaling patterns.8 Clinically, evaluation of RAS alteration status is routinely done for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer since their presence predicts lack of response to anti-EGFR therapies (cetuximab and panitumumab). The presence of RAS alterations has also been associated with significantly worse overall survival (OS) among lung, colorectal and pancreatic cancers when compared to patients with wild-type RAS.11–14

A number of clinical trials have attempted to target RAS-altered cancers. For instance, blocking of Ras membrane association, which is an essential step for Ras activation, and targeting of Ras downstream effector signaling, have been extensively studied. Unfortunately, to date, most trials have failed to demonstrate clinical benefit among patients with RAS alterations (Supporting Information Table S1). For example, tipifarnib (famesyltransferase inhibitor15) and L-778,123 (dual inhibitor of famesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase type 1; block Ras membrane association) had minimal activity among patients with KRAS-mutated cancers16–18 (though recently there is preliminary evidence of activity in HRAS-mutated head and neck cancer19). Moreover, targeting of downstream signaling with a MEK inhibitor among patients with KRAS-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and the dual inhibition with MEK and AKT inhibitors among pancreatic cancer patients also failed to demonstrate clinical benefit when compared to chemotherapy as a comparator.20,21 Although targeting RAS has been challenging, early phase clinical trial with AMG 510 (a novel small molecule inhibitor specifically for KRAS G12C) among KRAS G12C altered cancer patients demonstrated clinical responses and further enrollment is ongoing.22 Moreover, the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib induced a remarkable response in a patient with Rosai–Dorfman syndrome, whose disease harbored a KRAS mutation but no other characterized alterations.23 Therefore, factors such as genomic coalterations might also attenuate responsiveness to agents that directly or indirectly impact Ras signaling.

In order to better understand the genotypic and phenotypic ecosystem of RAS,4 we used next-generation sequencing (NGS) to interrogate the molecular landscape of RAS alterations in 1,937 patients with diverse cancers. We also investigated the clinical characteristics, genomic coalterations and survival impact of RAS alterations, as well as the therapeutic impact of matched therapies, including illustrative patients given MEK inhibitors together with agents targeting coalterations.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We evaluated the genomic landscape of RAS alterations among 1,937 patients with diverse malignancies that were seen at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Moores Cancer Center from December 2012 to June 2017 (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Our study was performed according to the guidelines of the UCSD Institutional Review Board (Profile Related Evidence Determining Individualized Cancer Therapy [PREDICT], NCT02478931) or I-PREDICT (NCT02534675) and for any investigational therapies for which the patients consented.

Tissue samples and mutational analysis

Tumors were provided as formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples and evaluated by NGS in a clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA)-certified lab (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA). The methods used for NGS have been previously reported.24–26 Briefly, 50–200 ng of genomic DNA was extracted and purified from the submitted FFPE tumor samples. DNA was adaptor ligated, and hybrid capture was performed for all coding exons of 182–406 cancer-related genes plus selected introns from 14 to 31 genes frequently rearranged in cancer (Illumina HiSeq platform). Sequencing was performed with an average sequencing depth of coverage greater than 250×, with >100× at >99% of exons. Somatic mutations were identified with 99% specificity and >99% sensitivity for base substitutions at ≥5% mutant allele frequency, and >95% sensitivity for copy number alterations. Gene amplification was reported at ≥8 copies above ploidy, with ≥6 copies considered equivocal. The exception was ERRB2, for which ≥5 copies is considered equivocal amplification.25,26 One case underwent NGS at UCSD laboratory (n = 397 genes; CLIA-certified). Variants of unknown significance were not curated for the analyses.

Endpoints and statistical methods

Patient characteristics, prevalence of RAS alterations and genomic coalterations were summarized by descriptive statistics. The Fisher’s exact test and logistics regression analysis were used for categorical variables. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as time interval between the start of therapy and the date of disease progression. OS was defined as time from cancer diagnosis with recurrent or metastatic disease condition to last follow up or death. Patients with ongoing therapy without progression at the last follow-up date were censored for PFS at that date. Patients alive at last follow up were censored for OS. Log-rank test and Cox regression analysis were used to compare subgroups of patients. All tests were two-sided and variables with p < 0.1 were included for multivariate analysis, p values ≤0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with assistance from coauthor RO using Graph-Pad Prism version 7.0 (San Diego, CA) and SPSS version 24.0 (Chicago, IL).

Data availability

Data for our study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

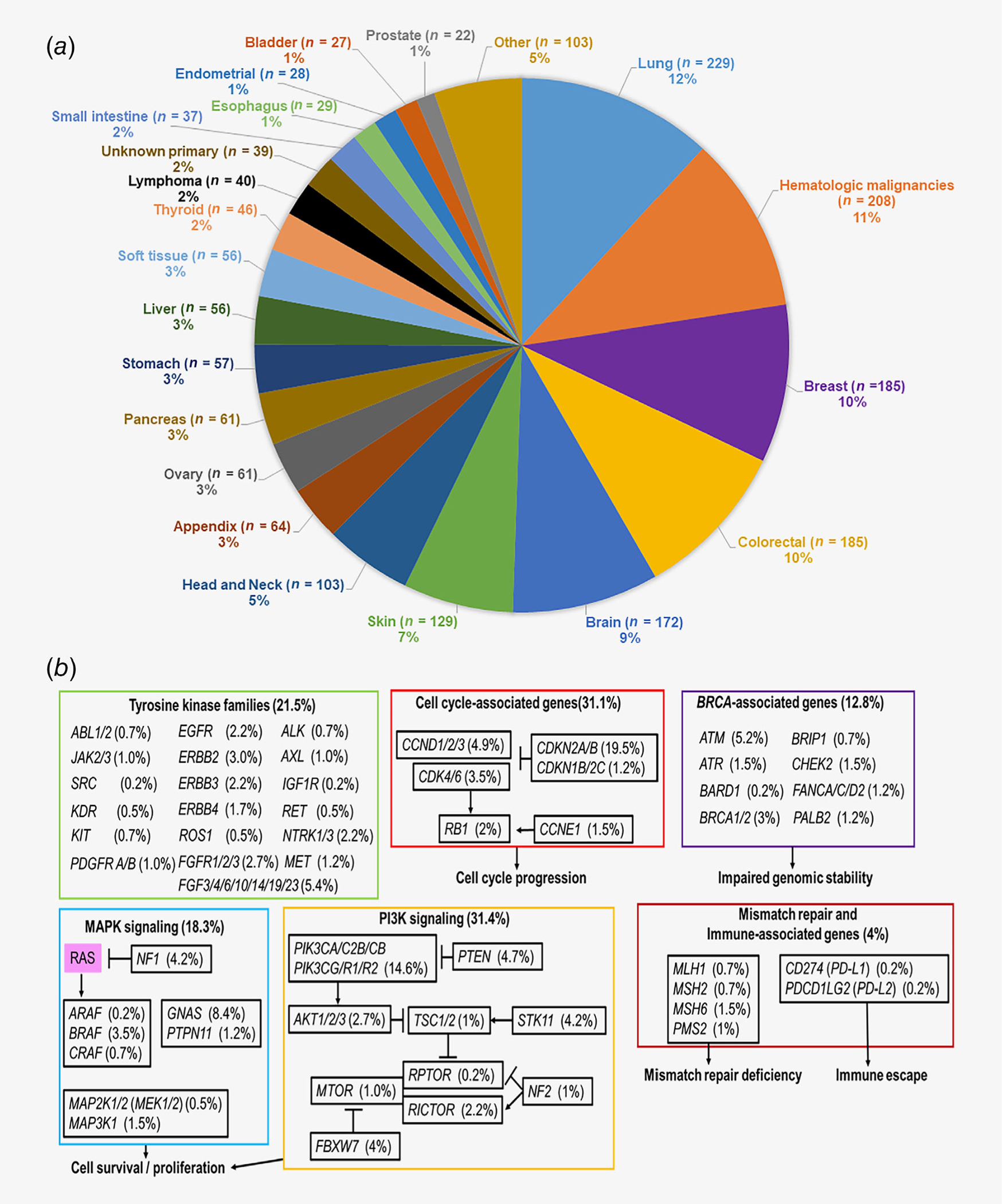

Among 1,937 patients with diverse cancers, the most common diagnosis was lung cancer (11.8% [229/1,937]), followed by hematologic malignancies (10.7% [208/1,937]), breast (9.6% [185/1,937]) and colorectal cancers (9.6% [185/1,937]; Fig. 1a and Supporting Information Table S2). Overall, RAS alterations were found in 20.9% of cases (405/1,937). Among different RAS alterations (n = 405), KRAS was most commonly altered (80.0% [324/405]) followed by NRAS (16.0% [65/405]) and HRAS (4.9% [20/405]) alterations (n = 4 had both KRAS and NRAS alterations). RAS alterations were significantly associated with pancreatic cancer (72.1% [44/61], odds ratio [OR]: 8.41), appendiceal (57.8% [37/64], OR: 3.37) and colorectal cancers (57.3% [106/185], OR: 4.45; all p < 0.0001 [multivariate]). RAS alterations were significantly less common among brain (0.6% [1/172], OR 0.03, p = 0.001), breast (3.8% [7/185], OR 0.18, p < 0.0001), soft tissue sarcomas (5.4% [3/56], OR 0.24, p = 0.02), head and neck (5.8% [6/103], OR: 0.23, p = 0.001) and hematologic malignancies (12.5% [26/208], OR 0.53, p = 0.01; all p values after multivariate analysis; Supporting Information Table S2).

Figure 1.

(a) Frequency of analyzed cancer types included in our study (n = 1,937). Included cancer diagnosis with n > 20. Among diverse cancer types analyzed in our study, the most common cancer diagnosis was lung cancer (n = 229, 12%) followed by hematologic malignancies (n = 208, 11%), breast (n = 185, 10%), colorectal (n = 185, 10%) and brain cancer (n = 172, 9%). (b) Coaltered oncogenic pathways associated with RAS alterations (n = 405). Among patients harboring RAS alterations (n = 405), coalterations in oncogenic pathways were observed in tyrosine kinase family genes (21.5%), cell cycle-associated genes (31.3%), BRCA-associated genes (12.8%), MAPK signaling pathway-associated genes (18.3%), PI3K signaling-associated genes (31.4%) and mismatch repair or immune-associated genes (4%). See Supporting Information Table S2 for detail.

Patients with RAS abnormalities had frequent coalterations

Among patients with RAS alterations, 95.3% (386/405) had coalterations (median: 3, range: 0–51). When compared to tumors bearing wild-type RAS, tumors harboring RAS alterations had significantly increased rates of coalterations in the following genes: STK11 (OR: 2.81, p = 0.01), SMAD4 (OR: 2.25, p = 0.003) and GNAS (OR: 1.95, p = 0.02). In contrast, alterations in RET (OR: 0.19, p = 0.03), KIT (OR: 0.21, p = 0.01), EGFR (OR: 0.27, p = 0.001) and BRAF (OR: 0.29, p = 0.0001) were less frequently associated with RAS alterations (all p values after multivariate analysis; Supporting Information Table S2).

When coalterations were grouped depending on their oncogenic pathways (e.g., EGFR and FGFR alterations grouped into tyrosine kinase families), RAS altered cases were most commonly coaltered with genes impacting PI3K signaling (31.4% [127/405]) followed by cell cycle-associated genes (31.1% [126/405]), tyrosine kinase families (21.5% [87/405]), MAPK signaling (18.3% [74/405]), BRCA-associated genes (12.8% [52/405]) and mismatch repair and immune-associated genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, CD274 [PD-L1] and PDCD1LG2 [PD-L2], 4% [16/405]; Fig. 1b and Supporting Information Table S3).

RAS alterations were associated with shorter survival among patients with metastatic or recurrent solid tumors (n = 1,526)

Among 1,937 patients with diverse cancers, patients with metastatic or recurrent solid tumors were included in the survival analysis (n = 1,526; excluded patients with lymphoma [n = 40], hematological malignancies [n = 208] and patients without recurrent or metastatic disease condition [n = 163]; Supporting Information Fig. S1). Among patients with metastatic or recurrent solid tumors, 23.5% (358/1,526) had RAS alterations. When compared to patients whose tumors harbored wild-type RAS, those who harbored cancers with RAS alterations had significantly shorter OS from date of metastatic/recurrent disease, (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03–1.48, p = 0.02 [multivariate]; Table 1 and Fig. 2a).

Table 1.

Overall survival by RAS (K/N/H-RAS) subtype alteration and different RAS codon alteration status (n = 1,526)

| Patient characteristics (n = 1,526) | HR for overall survival (95% Cl) (univariate)1 | p-value (univariate)1 | HR for overall survival (95% Cl) (multivariate)2 | p-value (multivariate)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Overall survival comparing RAS wild-type and RAS altered cases | ||||

| RAS wild-type (n = 1,168) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS alteration (n = 358) | 1.34 (1.11–1.63) | 0.001 | 1.24 (1.03–1.48) | 0.02 |

| Overall survival among K/N/H- RAS alterations 3 | ||||

| RAS wild-type (n = 1,168) | 1 (reference) | |||

| KRAS (n = 295) | 1.46 (1.18–1.80) | <0.0001 | 1.30 (1.07–1.59) | 0.01 |

| NRAS (n = 48) | 0.86 (0.54–1.37) | 0.55 | ||

| HRAS (n = 16) | 1.05 (0.51–2.15) | 0.89 | ||

| Overall survival among different codon alterations | ||||

| RAS wild-type (n = 1,168) | 1 (reference) | |||

| KRAS G12D (n = 91) | 1.1 (0.76–1.6) | 0.59 | ||

| KRAS G12V (n = 68) | 1.76 (1.14–2.7) | 0.001 | 1.64 (1.18–2.30) | 0.004 |

| KRAS G13D (n = 27) | 2.01 (1.02–3.94) | 0.004 | 2.07 (1.27–3.38) | 0.004 |

| KRAS amplificador4 (n = 24) | 1.84 (0.9–3.75) | 0.02 | 1.88 (1.09–3.24) | 0.02 |

| KRAS G12C (n = 22) | 0.84 (0.4–1.75) | 0.66 | ||

| KRAS G12R (n = 17) | 2.15 (0.87–5.34) | 0.01 | 1.58 (0.83–2.99) | 0.16 |

| KRAS Q61H (n = 11) | 2.00 (0.64–6.20) | 0.09 | 1.39 (0.61–3.19) | 0.43 |

| KRAS Q61K (n = 12) | 0.38 (0.16–0.91) | 0.16 | ||

| KRAS Q61R (n = 18) | 1.24 (0.54–2.85) | 0.57 | ||

Included characteristics with n s 10.

HR and p values with univariate analysis by log-rank test.

HR and p values with multivarlate analysis by Cox regresslon analysis. Adjusted for age, sex, prlmary site of cancer diagnosis and variables among sub-categorles with p-value <0.1 by univariate analysis (all variables In Table 1 and Supportlng Information Table S4 with univariate p values <0.1 were Included In the multivarlate analysis shown in this table).

n = 1 had both KRAS and NRAS alteratlons.

KRAS ampllficatlon Indlcates ampllficatlon In wlld-type KRAS.

Abbrevlatlons: Cl, confidence Interval; HR, hazard ratlo.

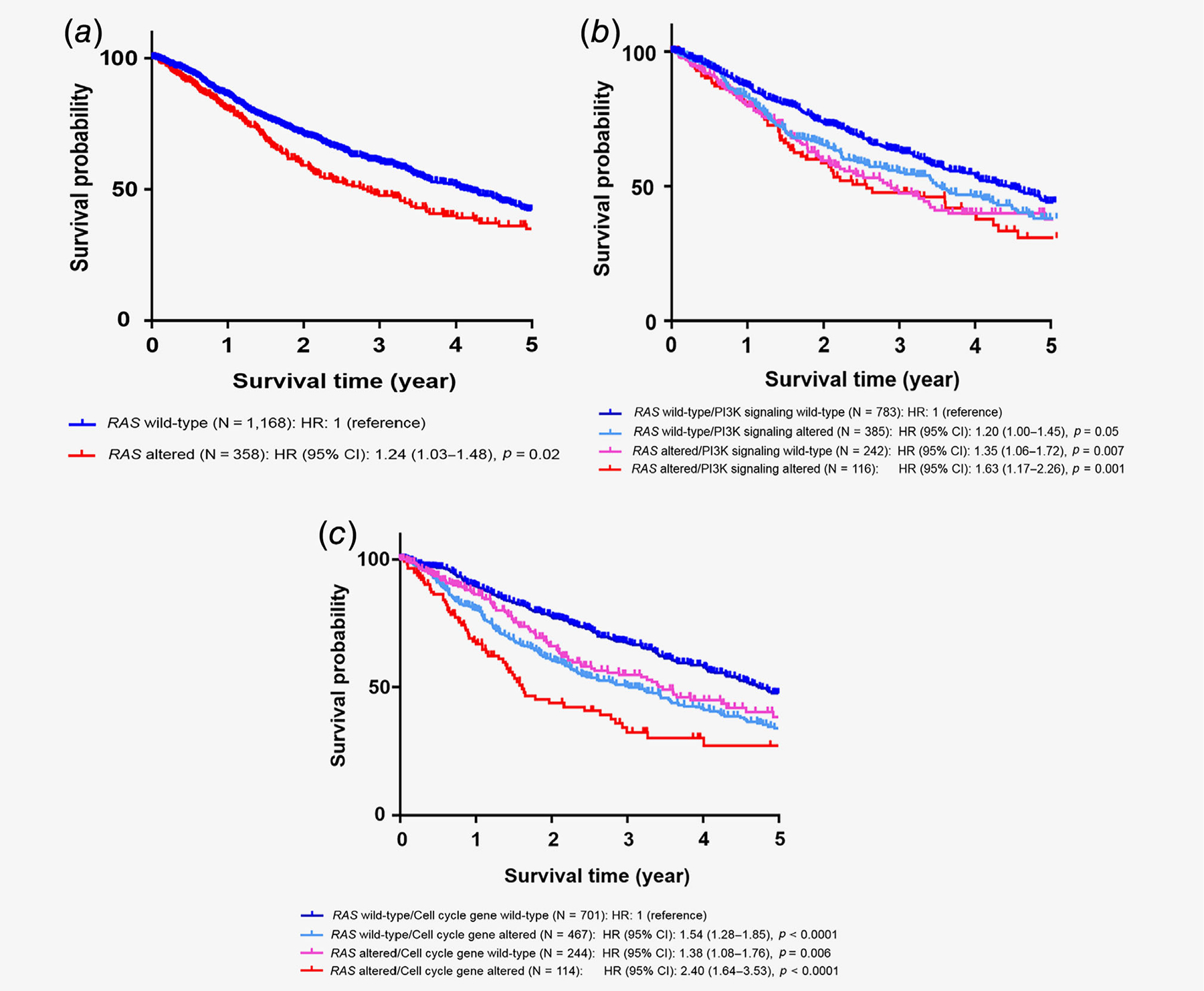

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for overall survival. Tick marks represent censored time points for patients still alive at last follow up. (a) Overall survival from time of metastatic/advanced disease comparing patients with wild-type RAS and RAS-altered cancers. Overall survival analysis based on RAS alteration status. When compared to RAS wild-type cases (n = 1,168), RAS altered cases (n = 358) had worse overall survival with HR of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.03–1.48, p = 0.02) by log-rank test, (b) Overall survival from time of metastatic/advanced disease comparing impact of RAS and PI3K signaling alterations. Overall survival analysis based on RAS and PI3K signaling-associated gene alteration status. When compared to RAS wild-type/PI3K signaling wild-type cases (n = 783), RAS wild-type/PI3K signaling altered cases (n = 385) had HR of 1.20 (95% CI: 1.00–1.45, p = 0.05), RAS altered/PI3K signaling wild-type cases (n = 242) had HR of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.06–1.72, p = 0.007) and RAS altered/PI3K signaling altered cases (n = 116) had HR of 1.63 (95% CI: 1.17–2.26, p = 0.001) by log-rank test, (c) Overall survival from time of metastatic/advanced disease comparing impact of RAS and cell cycle-associated alterations. Overall survival analysis based on RAS and cell cycle-associated gene alteration status. When compared to RAS wild-type/Cell cycle gene wild-type cases (n = 701), RAS wild-type/cell cycle gene-altered cases (n = 467) had HR of 1.54 (95% CI: 1.28–1.85, p < 0.0001), RAS altered/cell cycle gene wild-type cases (n = 244) had HR of 1.38 (95% CI: 1.08–1.76, p = 0.006) and RAS altered/cell cycle genealtered cases (n = 114) had HR of 2.40 (95% CI: 1.64–3.53, p < 0.0001) by log-rank test. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Specific RAS alterations correlated with worse outcome.

Among K-, N- and H-RAS alterations, KRAS alterations were the only alterations significantly associated with worse OS (HR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.07–1.59, p = 0.01). Moreover, among different RAS codon alterations, KRAS G12V (HR: 1.64, 95% CI: 1.18–2.30, p = 0.004), KRAS G13D (HR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.27–3.38, p = 0.004) and KRAS amplification (HR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.09–3.24, p = 0.02) were independently associated with inferior OS (all p values by multivariate analysis; Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S4).

RAS alterations accompanied by coalterations in PI3K signaling and cell cycle-associated genes had worse survival

We also investigated survival based on the RAS alterations and the coaltered oncogenic pathways. Interrogating all 1,526 individuals (including RAS wild-type and RAS mutated), patients who had both RAS alterations and coaltered oncogenic pathways in other MAPK signaling genes, BRCA-associated genes and immune-related gene alterations showed no significant difference in OS when compared to patients with RAS wild-type without coaltered pathways (Table 2). However, harboring alterations in both RAS and tyrosine kinase family genes (HR: 1.37, 95% CI: 0.98–1.93, p = 0.07 [trend]), PI3K signaling (HR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.15–2.01, p = 0.004; Fig. 2b) and cell cycle-associated genes (HR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.49–2.67, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2c) was associated with worse OS when compared to patients without those anomalies (all p values by multivariate analysis; Table 2).

Table 2.

Overail survival by coaltered oncogenic pathways associated with RAS alterations (n = 1,526)

| Patient characteristics | HR for overall survival (95% Cl) (univariate)1 | p-value (univariate)1 | HR for overall survival (95% Cl) (multivariate)2 | p-value (multivariate)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Overall survival depending on RAS and tyrosine kinase family gene alterations (n = 1,526) 3 | ||||

| RAS wild-type/tyrosine kinases wild-type (n = 769) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS wild-type/tyrosine kinases altered (n = 399) | 1.11 (0.93–1.34) | 0.25 | ||

| RAS altered/tyrosine kinases wild-type (n = 278) | 1.34 (1.07–1.67) | 0.006 | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | 0.07 |

| RAS altered/tyrosine kinases altered (n = 80) | 1.55 (1.04–2.32) | 0.01 | 1.37 (0.98–1.93) | 0.07 |

| Overall survival depending on tyrosine kinase family gene alterations among RAS altered cases (n= 358) | ||||

| RAS altered/Tyrosine Kinases wild-type (n = 278) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS altered/Tyrosine Kinases altered (n = 80) | 1.11 (0.76–1.61) | 0.58 | ||

| Overall survival depending on RAS and MAPK signaling alterations (n = 1,526) 3 | ||||

| RAS wild-type/other MAPK wild-type (n = 919) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS wild-type/other MAPK altered (n = 249) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.88 | ||

| RAS altered/other MAPK wild-type (n = 294) | 1.34 (1.08–1.65) | 0.003 | 1.20 (0.99–1.46) | 0.07 |

| RAS altered/other MAPK altered (n = 64) | 1.35 (0.86–2.10) | 0.13 | ||

| Overall survival depending on MAPK signaling alterations among RAS altered cases (n = 358) | ||||

| RAS altered/other MAPK wild-type {n = 294) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS altered/MAPK altered (n = 64) | 1.04 (0.69–1.56) | 0.87 | ||

| Overall survival depending on RAS and PI3K signaling alterations (n = 1,526) 3 | ||||

| RAS wild-type/PI3K signaling wild-type (n = 783) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS wild-type/PI3K signaling altered (n = 385) | 1.20 (1.00–1.45) | 0.05 | 1.29 (1.07–1.56) | 0.01 |

| RAS altered/PI3K signaling wild-type (n = 242) | 1.35 (1.06–1.72) | 0.007 | 1.26 (1.00–1.58) | 0.05 |

| RAS altered/PI3K signaling altered (n = 116) | 1.63 (1.17–2.26) | 0.001 | 1.52 (1.15–2.01) | 0.004 |

| Overall survival depending on PI3K signaling alterations among RAS altered cases (n = 358) | ||||

| RAS altered/PI3K signaling wild-type (n = 242) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS altered/PI3K signaling altered (n = 116) | 1.16 (0.84–1.61) | 0.36 | ||

| Overall survival depending on RAS and celi cycle associated gene alterations (n = 1,526) 3 | ||||

| RAS wild-type/Ceil cycle gene wild-type (n = 701) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS wild-type/Ceil cycle gene altered (n = 467) | 1.54 (1.28–1.85) | <0.0001 | 1.52 (1.27–1.81) | <0.0001 |

| RAS altered/Cell cycle gene wild-type (n = 244) | 1.38 (1.08–1.76) | 0.006 | 1.28 (1.01–1.61) | 0.04 |

| RAS altered/Cell cycle gene altered (n = 114) | 2.40 (1.64–3.53) | <0.0001 | 1.99 (1.49–2.67) | <0.0001 |

| Overall survival depending on celi cycle associated gene alterations among RAS altered cases (n = 358) | ||||

| RAS altered/Cell cycle gene wild-type (n = 244) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS altered/Cell cycle gene altered (n = 114) | 1.70 (1.20–2.41) | 0.001 | 1.42 (0.99–2.02) | 0.056 |

| Overall survival depending on RAS and BRCA associated gene alterations (n = 1,526) | 3 | |||

| RAS wild-type/BRCA associated gene wild-type (n = 994) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS wild-typ e/BRCA associated gene altered (r? = 174) | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | 0.47 | ||

| RAS altered/BRCA associated gene wild-type (n = 309) | 1.31 (1.07–1.61) | 0.005 | 1.20 (0.99–1.46) | 0.06 |

| RAS altered/BRCA associated gene altered (n = 49) | 1.34 (0.84–2.14) | 0.16 | ||

| Overall survival depending on BRCA associated gene alterations among RAS altered cases (n = 358) | ||||

| RAS altered/BRCA associated gene wild-type (n = 309) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS altered/BRCA associated gene altered (n = 49) | 1.00 (0.65–1.55) | 0.99 | ||

| Overall survival depending on RAS and immune related gene alterations (n = 1,526) 3 | ||||

| RAS wild-type/immune related genes wild-type (n = 1,139) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS wild-type/immune related genes altered (n = 29) | 1.01 (0.57–1.80) | 0.97 | ||

| RAS altered/immune related genes wild-type (n = 342) | 1.35 (1.11–1.64) | 0.001 | 1.23 (1.03–1.48) | 0.03 |

| RAS altered/immune related genes altered (n = 16) | 1.04 (0.42–2.57) | 0.92 | ||

| Overall survival depending on immune related gene alterations among RAS altered cases (n = 358) | ||||

| RAS altered/immune related genes wild-type (n = 342) | 1 (reference) | |||

| RAS altered/immune related genes altered (n = 16) | 0.74 (0.34–1.60) | 0.50 | ||

Included characteristics with n ≥ 10.

HR and p values with univariate analysis by log-rank test.

HR and p values with multlvarlate analysis by Cox regresslon analysis. Adjusted for age, sex, prlmary site of cancer diagnosis and variables among sub-categorles with p-value <0.1 by univariate analysis (all variables In Table 1 or Supportlng Information Table S3 with univariate p values <0.1 were included in the multlvariate analysis shown in this table).

See Figure 1 and Supportlng Information Table S2 for the descrlption of coaltered oncogenlc pathways; for example, immune-related genes Included MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, CD274 (PD-L1) and PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) alteratlons.

Abbrevlations: Cl, confidence Interval; HR, hazard ratio.

When OS was evaluated just among 358 patients with RAS alterations (not including patients with wild-type RAS), coalterations in cell cycle-associated genes showed a strong trend to worse OS (HR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.20–2.41, p = 0.001 [univariate], HR: 1.42, 95% CI: 0.99–2.02, p = 0.056 [multivariate] [trend]; Table 2).

Treatment outcomes among patients with metastatic or recurrent/MS-altered solid tumors (n = 284)

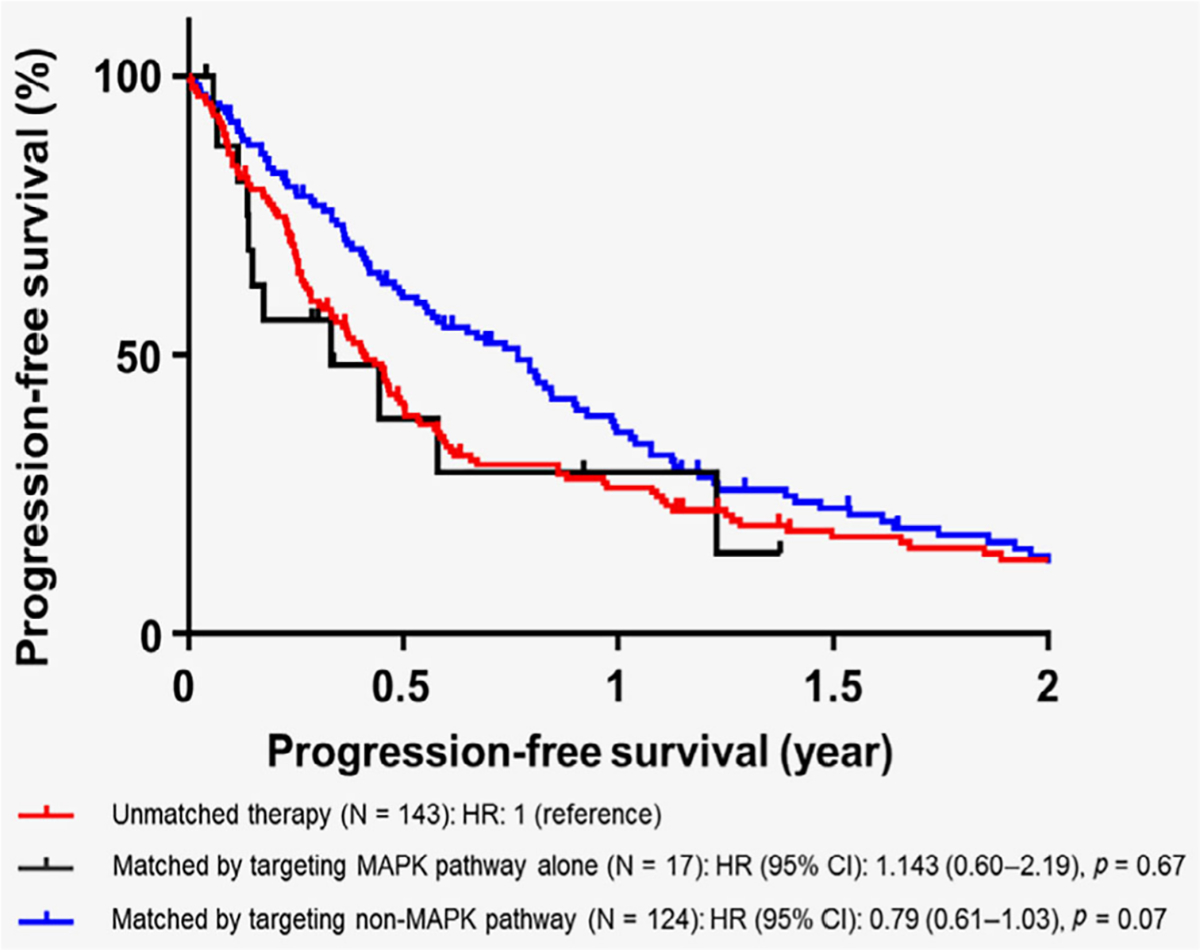

Among patients with RAS-altered recurrent or metastatic solid tumors (n = 358), 284 patients received systemic therapies and were evaluable for assessment of PFS (Supporting Information Fig. S1). When PFS was compared to patients who received unmatched therapy (therapies that were not based on genomic markers; n = 143), patients who received therapies targeting only the MAPK pathway (n = 17) did not show a significant difference in PFS (HR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.60–2.19, p = 0.67 [univariate]). On the other hand, patients who received matched therapy targeting a non-MAPK pathway (n = 124) had a trend for better PFS when compared to the unmatched therapy group (HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.61–1.03, p = 0.07 [univariate]; Fig. 3). After multivariate analysis, targeting of non-MAPK pathway did not remain a significant factor predicting longer PFS (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.67–1.19, p = 0.42; Supporting Information Table S5). Patients who received therapies targeting both MAPK and non-MAPK pathways were not included in the analysis due to the small sample size (n = 9); however, 33.3% (3/9) achieved a partial response (PR; Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Progression-free survival among patients with RAS-altered solid tumors who received systemic therapies (n = 284). Tick marks represent censored time points for patients still progression-free at last follow up. Progression-free survival among patients with RAS mutations who received systemic therapies (n = 284) were evaluated (Patients who received therapies targeting both MAPK and non-MAPK pathways were not included in the analysis due to the small sample size; n = 9). When compared to patients who received unmatched therapy (n = 143), patients who received matched therapy only against MAPK pathway had HR of 1.14 (95% CI: 0.60–2.19, p = 0.67; n = 17) and patients who received matched targeted therapy targeting non-MAPK pathway had HR of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.61–1.03, p = 0.07; n = 124).

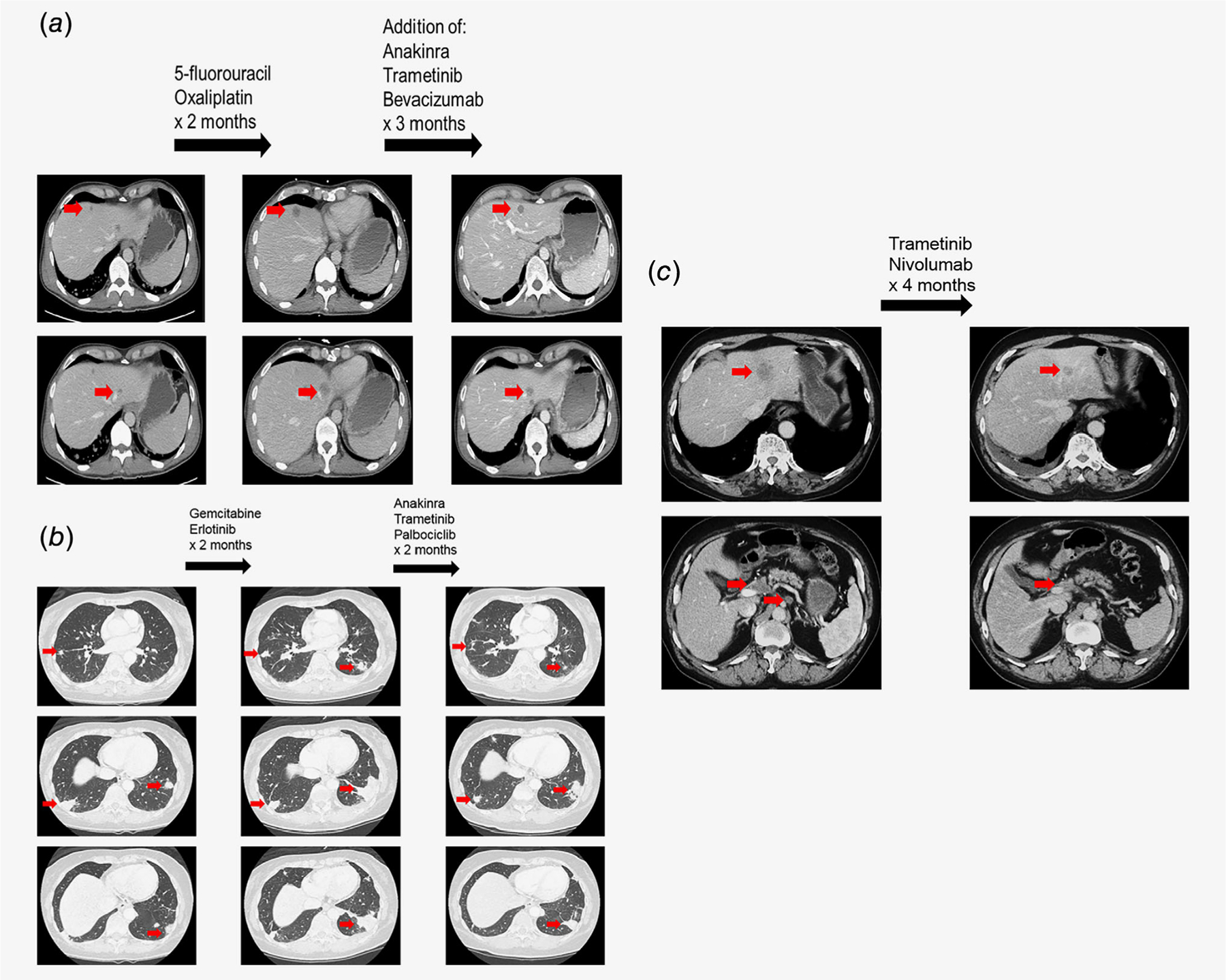

Figure 4.

Illustrative cases of patients with R4S alterations treated with MEK inhibitor-based therapies, (a) Colon cancer patient with KRAS G13D and TP53 alterations managed with trametinib and bevacizumab-based targeted therapy approach. A 50-year-old man presented with rectal pain. Further evaluation with colonoscopy revealed a rectal mass. Biopsy was consistent with moderately differentiated invasive colorectal adenocarcinoma. Further imaging with computed tomography (CI) showed lung and liver metastases (a, left panel). Patient was initially started on 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin. However, 2 months after the initiation of therapy, CT showed progression in the liver metastases (a, middle panel). The case was discussed at the Molecular Tumor Board and suggestions included continuing on 5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin, adding trametinib (MEK inhibitor) and anakinra (interleukin-1 [IL-1] receptor antagonist) for KRAS G13D (MEK inhibitor to attenuate signals downstream of KRAS. IL-1 having been shown to be a downstream mediator of cell growth in KR4S-mutated cells35–38) and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF antibody) for TP53 C242fs*5 (TP53 alterations are associated with increased VEGF expression39; clinical data suggested that patients with TP53 alterations have longer PFS with bevacizumab [anti-VEGF antibody] or pazopanib [small molecule VEGFR Inhibitor] containing regimens when compared to treatment without anti-anglogenesis agents40,41). After adding the targeted agents, the patient achieved a partial response (30% decrease by RECIST 1.1; a, right panel). No significant toxicities occurred. After 9 months of therapy, patient elected to switch the therapy to nonconventional approach that consisted of herbal medicine. (b) Pancreatic cancer patient with KRAS G12D and CDKN2A R80* alteration managed with trametinib and palbociclib based combination therapy. A 63-year-old woman was Initially diagnosed with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of pancreas. Patient was started on neoadjuvant therapy with 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and irinotecan followed by pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery was followed by adjuvant gemcitabine. Ten months after the surgery for local recurrence, patient received chemoradiation therapy with capecitabine. Patient was subsequently found to have lung metastases and received albumin-bound paclitaxel In combination with palbociclib until progression (PFS = 3.6 months; best response = stable disease; on a clinical trial) followed by gemcitabine plus erlotinib with progression (b, left and middle panels). Case was discussed at the Molecular Tumor Board with suggestion of trametinib (MEK inhibitor) and anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist) for KRAS G12D (IL-1 having been shown to be a downstream mediator of cell growth In KRAS-mutated cells35–38) and readministration of palbociclib (CDK4/6 inhibitor) for CDKN2A R80*. After 2 months of combination therapy, the patient achieved a partial response (31.7% decrease by RECIST 1.1). PFS lasted 9.2 months. There was no significant toxicity, (c) Patient with adenocarcinoma of unknown primary with KRAS G12D and MLH1 alteration managed with trametinib plus nivolumab. An 82-year-old-man presented with abdominal pain. Further workup revealed patient to have adenocarcinoma of unknown primary with liver and abdominal lymph node metastases. Genomic analysis revealed KRAS G12D and MLH1 splice site 1989+1G>T. The case was discussed at the Molecular Tumor Board and it was suggested to enroll the patient into I-PREDICT protocol (NCT02534675) and to start therapy with trametinib for KRAS G12D and nivolumab (anti-PD-1 inhibitor) for MLH1 alteration (checkpoint inhibitor-associated with antitumor activity in patients with mismatch repair gene alteration including MLH1; microsatellite instability status: ambiguous; tumor mutational burden: intermediate [15 mutations/megabase]). Patient achieved a partial response (36.4% decrease per RECIST 1.1; c, left to right) along with normalization of carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA-19–9) tumor marker (>10,000 U/ml down to 20 U/ml). PFS lasted 15 months.42 There was no significant toxicity.

Illustrative cases.

Three patients with advanced lethal malignancies given trametinib and a therapy matched to a genomic coalteration(s) who achieved partial responses lasting 9, 9.2 and 15 months are shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

Herein we report the comprehensive genomic landscape of RAS alterations among 1,937 patients with diverse malignancies and clinical annotation. Overall, RAS alterations were found in 20.9% of patients (405/1,937). Among diverse cancer types, RAS alterations were significantly associated with pancreatic cancer (72.1% [44/61], odds ratio [OR]: 8.41), appendiceal malignancies (57.8% [37/64], OR: 3.37) and colorectal cancers (57.3% [106/185], OR: 4.45; all p < 0.0001 after multivariate analysis; Supporting Information Table S2), which is consistent with previous reports.4–6

Since the presence of RAS alterations has been linked to significantly worse survival among lung, colorectal and pancreatic cancers when compared to patients with wild-type RAS,11–14 we also examined the impact of RAS alterations on survival among diverse solid tumors (n = 1,526). Consistent with previous reports, we have observed that patients with RAS-altered tumors had significantly worse OS (HR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.03–1.48, p = 0.02 [multivariate]; Table 1). Among different subtypes of RAS alterations (K-, N- and H-RAS alterations), KRAS alterations were associated with worse OS (HR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.07–1.59, p = 0.01 [multivariate]). Furthermore, among different codon or other alterations, KRAS G12V, KRAS G13D and KRAS amplification correlated with poor OS when compared to patients with RAS wild-type (HR: 1.64, 95% CI: 1.18–2.30, p = 0.004, HR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.27–3.38, p = 0.004 and HR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.09–3.24, p = 0.02, respectively [multivariate]; Table 1). Our findings are consistent with previous reports indicating that varied RAS alterations do not all have the same impact.13,14,27 Distinct clinical outcomes may be attributable to dissimilar degrees of GTP-binding ability among RAS anomalies, thus leading to a differential impact on downstream signaling and effectors.28 For example, Ihle et al.8 showed that PI3K signaling was preferentially activated in cell lines with KRAS G12D alterations; meanwhile, activation of the Ral A/B pathway associated with KRAS G12C alterations. In the study by Ihle et al. differences in downstream effectors, depending on the specific codon alterations, also affected colony number and tumor growth, which may explain the heterogeneous clinical outcomes among different RAS-altered patients.

Importantly, we have demonstrated that coaltered oncogenic pathways associated with RAS abnormalities can also influence survival outcome. Notably, coalterations in both RAS and PI3K signaling or cell cycle-associated genes were significantly correlated with worse OS when compared to patients without those anomalies (HR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.15–2.01, p = 0.004 and HR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.49–2.67, p < 0.0001, respectively [multivariate]; Table 2 and Figs. 2b and 2c). This observation is in line with a previous report that showed that a combination of alterations, especially KRAS and CDKN2A abnormalities, had significantly worse disease-free survival and OS among patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.13 Further investigations that incorporate an understanding of RAS downstream signaling and effectors as well as the functional impact of genomic coalterations are necessary.

Therapeutically, comprehensive understanding of RAS and its genomic coalterations is likely required to better manage RAS-altered malignancies. As mentioned, multiple attempts have been made to target RAS-altered cancers, mainly by blocking the RAS membrane association16–18 or by inhibiting the RAS downstream effectors (mostly with single-agent targeting with a MEK inhibitor or in combination with PI3K, AKT or mTOR inhibitors).20,21 However, most of the approaches to date have failed to yield satisfactory antitumor activities (and cotargeting of MEK and PI3K pathways has demonstrated significant toxicity29). Therefore, there is no standardized therapy targeting RAS-altered cancers (Supporting Information Table S1).

In our current study, we have also demonstrated that targeting the MAPK pathway with MEK inhibitors (n =17) was not associated with improvement in PFS when compared to patients receiving unmatched therapy (n = 143; HR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.60–2.19, p = 0.67; Fig. 3 and Supporting Information Table S5). Giving patients therapy matched to their coalterations, without targeting the MEK pathway, was associated with improved PFS, albeit without reaching statistical significance (Fig. 3). However, in contrast to previous reports and the current study, a dramatic response has been reported with single-agent cobimetinib (MEK inhibitor) in a patient with Rosai-Dorfman disease (rare non-Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis associated with massive lymphadenopathy) who harbored a KRAS G12R alteration, but without any coalterations.23 Therefore, one of the potential challenges in targeting RAS alterations with agents such as MEK inhibitors may be due to resistance mediated by the high number of genomic coalterations. Indeed, we observed that most patients with RAS alterations harbored genomic coalterations (95.3% [386/405], median: 3, rang: 0–51), often potentially affecting important oncogenic pathways (Fig. 1b and Supporting Information Table S3). Hence, effective Ras targeting may require a tailored combination approach that addresses both Ras activation and the specific coaltered pathway in each patient.30–33 In this regard, we have demonstrated a response rate of 33% (3 of 9 individuals) among patients who received matched therapies targeting both MAPK and non-MAPK pathways. For instance, in a patient with pancreatic cancer and a KRAS and a CDKN2A alteration given both trametinib and palbociclib, a partial response lasting 9 months was achieved after having failed therapies including a palbociclib-containing regimen that did not include a MEK inhibitor (Fig. 4b). Although the low sample size precludes definitive conclusions, our observations suggest that such a customized combination approach warrants further investigation (I-PREDICT trial currently ongoing [ClinicalTrial.gov, NCT02534675]).34

There were several limitations to the current report. First, clinical correlations were assessed retrospectively. Second, since the number of cancer types included in the study was based on the samples sent for NGS by treating physicians, sample size bias cannot be ignored. Third, multiple assessments could result in overcalling the implication of positive p values. Fourth, molecular analysis was performed on archival tumor samples that were obtained at various time points in relation to the clinical history. However, despite these limitations, the current study provides a large and comprehensive clinical analysis of RAS alterations in diverse, clinically annotated cancers.

In conclusion, we have shown that 20.9% of 1,937 patients with varied cancers had RAS alterations. RAS-altered versus wild-type cases (especially those involving KRAS) were associated with significantly worse survival. Moreover, among different subtypes of RAS alterations, KRAS G12V and GOD mutations and KRAS amplification correlated with the shortest survival. The majority of RAS-altered cases also had genomic coalterations (95.3% [386/405], median: 3) affecting critical oncogenic signals that could serve to mediate resistance. Coalterations in both RAS and PI3K signaling or cell cycle-associated genes associated with worse survival when compared to patients without those alterations. Among RAS-altered cases, patients who received matched targeted therapy against non-MAPK pathway alterations had a trend for better PFS when compared to patients who received unmatched therapy, but targeting the Ras pathway alone with MEK inhibitors showed no improvement in outcome. In a small subset of nine patients given combination therapies targeting both MAPK and the specific non-MAPK gene altered, a response rate of 33% was achieved, as reflected by the illustrative cases (Fig. 4). Further clinical investigation of individualized combinations that include agents that impact both MAPK and the precise coaltered gene(s) harbored by each tumor in patients with RAS-altered cancers is warranted.

Supplementary Material

What’s new?

Tumors harboring alterations in RAS are notoriously difficult to treat. Indeed, despite extensive study, most therapeutic strategies designed to target RAS-altered cancers have yielded little benefit in patients. In this investigation of the biology of RAS-altered cancers, specific alterations in KRAS were associated with significantly reduced survival compared to other RAS-altered and wild-type RAS malignancies. Shortest survival time was linked to co-alterations in RAS and PI3K-signaling or cell cycle-associated genes. Therapeutically, a subset of patients with RAS alterations responded to treatment with MEK inhibitors plus tailored non-MAPK-targeting agents, suggesting that overcoming resistance mediated by genomic co-alterations requires tailored combinations.

Acknowledgements

This work was also supported in part by the Jon Schneider Memorial Cancer Research Fund, as well as NIH K08CA168999 and R21CA192072 (to J.K.S.). The project described was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, Grant TL1TR001443 (to P.R.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported in part by Foundation Medicine, the Joan and Irwin Jacobs Fund philanthropic fund; and by National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health [grant P30 CA023100 (to R.K., rkurzrock@ucsd.edu)].

Abbreviations:

- CI

confidence interval

- CLIA

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

- FFPE

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- HR

hazard ratio

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- NSCLC

nonsmall cell lung cancer

- OR

odds ratio

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-ldnase

- PR

partial response

- UCSD

University of California, San Diego

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Shumei Kato serves as a consultant for Foundation Medicine. Jason K Sicklick receives research funds from Foundation Medicine Inc. and Amgen, as well as consultant fees from Grand Rounds, Deciphera and LOXO. David S Hong receives research and grant funding from AbbVie, Adaptimmune, Aldi-Norte, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Fate Therapeutics, Genentech, Genmab, Ignyta, Infinity, Kite, Kyowa, Lilly, Loxo, Merck, Medlmmune, Mirati, miRNA, Molecular Templates, Mologen, NCI-CTEP, Novartis, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, Turning Point Therapeutics. Travel, accommodations, expenses from LOXO, miRNA, Genmab, AACR, ASCO and SITC. Serves as consulting or advisory role in Alpha Insights, Amgen, Axiom, Adaptimmune, Baxter, Bayer, Genentech, GLG, Group H, Guidepoint, Infinity, Janssen, Merrimack, Medscape, Numab, Pfizer, Prime Oncology, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, Trieza Therapeutics, WebMD. Other ownership interests include Molecular Match (advisor), OncoResponse (Founder) and Presagia Inc (Advisor). Paul Riviere received consulting fee from Peptide Logic. Razelle Kurzrock has Stock and Other Equity Interests in IDbyDNA, CureMatch, Inc., and Soluventis. Serves as consulting or Advisory Role for Gaido, LOXO, X-Biotech, Actuate Therapeutics, Roche, NeoMed, Soluventis, and Pfizer. Receives speaker’s fee from Roche. Research funding from Incyte, Genentech, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Sequenom, Foundation Medicine, Guardant Health, Grifols, Konica Minolta, DeBiopharm, Boerhringer Ingelheim, and OmniSeq [All institutional]) and serves as Board Member for CureMatch, Inc.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Der CJ, Krontiris TG, Cooper GM. Transforming genes of human bladder and lung carcinoma cell lines are homologous to the ras genes of Harvey and Kirsten sarcoma viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982;79:3637–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parada LF, Tabin CJ, Shih C, et al. Human EJ bladder carcinoma oncogene is homologue of Harvey sarcoma virus ras gene. Nature 1982;297:474–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos E, Tronick SR, Aaronson SA, et al. T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene is an activated form of the normal human homologue of BALB- and Harvey-MSV transforming genes. Nature 1982;298:343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, et al. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission Possible? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014;13:828–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res 2012;72:2457–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, et al. Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell 2014;25:272–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins MA, Bednar F, Zhang Y, et al. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest 2012;122:639–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ihle NT, Byers LA, Kim ES, et al. Effect of KRAS oncogene substitutions on protein behavior: implications for signaling and clinical outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:228–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev 2001;15:3243–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seguin L, Kato S, Franovic A, et al. An integrin beta(3)-KRAS-RalB complex drives tumour sternness and resistance to EGFR inhibition. Nat Cell Biol 2014;16:457–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phipps AI, Buchanan DD, Makar KW, et al. KRAS-mutation status in relation to colorectal cancer survival: the joint impact of correlated tumour markers. Br J Cancer 2013;108:1757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin P, Leighl NB, Tsao MS, et al. KRAS mutations as prognostic and predictive markers in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:530–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qian ZR, Rubinson DA, Nowak JA, et al. Association of Alterations in Main driver genes with outcomes of patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:el73420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cercek A, Braghiroli MI, Chou JF, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with colorectal cancers harboring NRAS mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenaux P, Raza A, Mufti GJ, et al. A multicenter phase 2 study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib in intermediate- to high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 2007;109:4158–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macdonald JS, McCoy S, Whitehead RP, et al. A phase II study of farnesyl transferase inhibitor R115777 in pancreatic cancer: a southwest oncology group (SWOG 9924) study. Invest New Drugs 2005;23:485–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin NE, Brunner TB, Kiel KD, et al. A phase I trial of the dual farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase inhibitor L-778,123 and radiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:5447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao S, Cunningham D, de Gramont A, et al. Phase III double-blind placebo-controlled study of farnesyl transferase inhibitor R115777 in patients with refractory advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3950–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho A, Chau N, Garcia IB, et al. Preliminary results from a phase 2 trial of Tipifarnib in HRAS-mutant head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;100:1367. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung V, McDonough S, Philip PA, et al. Effect of Selumetinib and MK-2206 vs Oxaliplatin and fluorouracil in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer after Prior therapy: SWOG SI 115 study randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:516–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janne PA, van den Heuvel MM, Barlesi F, et al. Selumetinib plus Docetaxel compared with Docetaxel alone and progression-free survival in patients with KRAS-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the SELECT-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:1844–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fakih M, O’Neil B, Price TJ, et al. Phase 1 study evaluating the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), and efficacy of AMG 510, a novel small molecule KRASG12C inhibitor, in advanced solid tumors. / Clin Oncol 2019;37:3003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobsen E, Shanmugam V, Jagannathan J. Rosai-Dorfman disease with activating KRAS mutation—response to Cobimetinib. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2398–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He J, Abdel-Wahab O, Nahas MK, et al. Integrated genomic DNA/RNA profiling of hematologic malignancies in the clinical setting. Blood 2016;127:3004–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas RK, Nickerson E, Simons JF, et al. Sensitive mutation detection in heterogeneous cancer specimens by massively parallel picoliter reactor sequencing. Nat Med 2006;12:852–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagle N, Berger MF, Davis MJ, et al. High-throughput detection of actionable genomic alterations in clinical tumor samples by targeted, massively parallel sequencing. Cancer Discov 2012;2:82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones RP, Sutton PA, Evans JP, et al. Specific mutations in KRAS codon 12 are associated with worse overall survival in patients with advanced and recurrent colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2017;116:923–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castellano E, Santos E. Functional specificity of ras isoforms: so similar but so different. Genes Cancer 2011;2:216–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolcher AW, Bendell JC, Papadopoulos KP, et al. A phase IB trial of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) in combination with everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 2015;26:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jardim DL, Schwaederle M, Wei C, et al. Impact of a biomarker-based strategy on oncology drug development: a meta-analysis of clinical trials leading to FDA approval. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:djv253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwaederle M, Zhao M, Lee JJ, et al. Impact of precision medicine in diverse cancers: a meta-analysis of phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3817–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwaederle M, Zhao M, Lee JJ, et al. Association of Biomarker-Based Treatment Strategies with Response Rates and Progression-Free Survival in refractory malignant neoplasms: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsimberidou AM, Iskander NG, Hong DS, et al. Personalized medicine in a phase I clinical trials program: the MD Anderson Cancer Center initiative. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sicklick JK, Kato S, Okamura R, et al. Molecular profiling of cancer patients enables personalized combination therapy: the I-PREDICT study. Nat Med 2019;25:744–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beaupre DM, Talpaz M, Marini FC 3rd, et al. Autocrine interleukinlbeta production in leukemia: evidence for the involvement of mutated RAS. Cancer Res 1999;59:2971–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Thuren T, et al. Effect of interleukinlbeta inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;390:1833–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling J, Kang Y, Zhao R, et al. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/beta/NF-kappaB activation by IL-1 alpha and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012;21:105–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhuang Z, Ju HQ, Aguilar M, et al. IL1 receptor antagonist inhibits pancreatic cancer growth by abrogating NF-kappaB activation. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:1432–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwaederle M, Lazar V, Validire P, et al. VEGFA expression correlates with TP53 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: implications for anti-angiogenesis therapy. Cancer Res 2015;75:1187–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koehler K, Liebner D, Chen JL. TP53 mutational status is predictive of pazopanib response in advanced sarcomas. Ann Oncol 2016;27:539–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Said R, Hong DS, Warneke CL, et al. P53 mutations in advanced cancers: clinical characteristics, outcomes, and correlation between progression-free survival and bevacizumab-containing therapy. Oncotarget 2013;4:705–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato S, Krishnamurthy N, Banks KC, et al. Utility of genomic analysis in circulating tumor DNA from patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Cancer Res 2017;77:4238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for our study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.