Abstract

Broadly neutralizing antibodies directed against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) offer promise as long-acting agents for prevention and treatment of HIV. Progress and challenges are discussed. Lessons may be learned from the development of monoclonal antibodies to treat and prevent COVID-19.

Keywords: HIV, broadly neutralizing antibodies, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19

Broadly neutralizing antibodies directed against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) offer promise as long-acting agents for prevention and treatment of HIV. Progress to date and future challenges are discussed. Lessons may be learned from the development of monoclonal antibodies to treat and prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Passive immunotherapy with high-titer serum or purified immune globulin has been used for more than a century to prevent or treat viral infections, including rabies, varicella and hepatitis B. Early efforts to apply high-titer human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) immunoglobulin were unsuccessful due to the extraordinary genetic diversity and antigenic variation of HIV isolates. Technological advances that permitted the identification and characterization of individual B cells that produce HIV-specific neutralizing antibodies led to the discovery of a series of monoclonal antibodies, termed broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), capable of neutralizing a wide range of HIV variants. As macromolecules (ie, immunoglobulins), bNAbs must be administered parenterally but have a much longer half-life (typically weeks to months) than small molecules (typically hours to days) because they are not subject to clearance by the usual hepatic or renal routes for drug elimination. A large number of bNAbs directed against a variety of epitopes on the viral envelope glycoprotein (gp120 and gp41) have been isolated, several of which have been tested in clinical trials [1]. We review the current state of the art regarding HIV bNAbs, their potential use as long-acting agents for the prevention and treatment of HIV, and the challenges faced in their clinical development and implementation. In addition, we review briefly the development and implementation of monoclonal neutralizing antibodies for prevention and treatment of COVID-19 and consider lessons learned that may apply to the development of bNAbs for HIV.

HIV-1 bNAbs

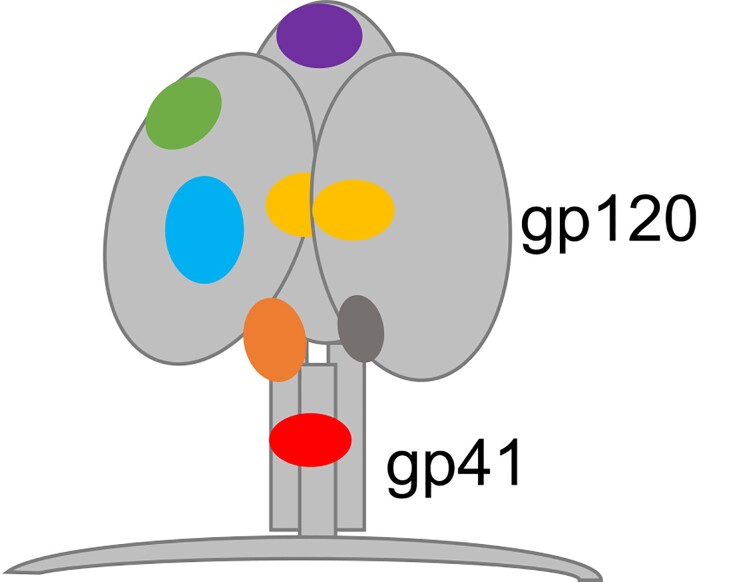

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope (Env) trimer is the only target on the surface of the virus and contains several sites of vulnerability targeted by antibodies (Figure 1). However, HIV-1 envelope spikes are extremely diverse and may differ by as much as 35% in their amino acid sequence. Besides enormous diversity, HIV-1 displays only a small number of functional envelope spikes per virion with a high density of rapidly shifting glycans that shield sites of potential vulnerability (reviewed in [2–4]). Due to these viral features, many of the antibodies that develop in most people living with HIV (PWH) are non-neutralizing and strain specific, with serum neutralization breadth typically arising several years after infection [5, 6]. The development of standardized and high-throughput assay platforms using well-characterized pseudovirus panels to measure in vitro serum neutralizing activity against HIV-1 allowed the identification of individuals with antibody responses against diverse viral strains [7, 8]. Serum neutralizing activity against HIV-1 among PWH is a continuum, where only 10–25% of infected individuals develop antibodies with breadth of neutralization and only an estimated 1% generate highly potent broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) or “elite neutralization” activity, defined by high neutralization titers against more than 1 pseudovirus within a clade group across at least 4 viral clades [9, 10].

Figure 1.

Binding sites on the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein for HIV-1 bNAbs. Purple, V1/V2 apex; green, V3 loop; cyan, CD4 binding site; yellow, gp120 “silent face”; orange, gp120-gp41 interface; dark gray, fusion peptide; red, MPER. Abbreviations: bNAbs, broadly neutralizing antibodies; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; MPER, membrane-proximal external region.

Despite bNAbs arising relatively infrequently during infection, antibodies with neutralizing breadth were described early on in the epidemic. Subsequently, antibodies with increased breadth and targeting distinct epitopes were obtained from PWH (reviewed in [11, 12]). Although these early antibodies displayed neutralizing breadth, their potency was limited resulting in little clinical benefit [13, 14]. It was only after the introduction of single cell antibody cloning methods that highly potent bNAbs were discovered [3, 15]. Epitope mapping and refined structural studies of Env-antibody complexes enabled the identification of vulnerable Env sites that are targeted by these antibodies. As discussed above, bNAbs are typically evaluated by the ability to block infection of cells in vitro using standardized methods. In addition to interfering with the interaction of Env with its host cell receptors and interrupting new rounds of infection, bNAbs also have the capacity to augment host antiviral immune responses and directly eliminate HIV-infected cells through the Fc-mediated engagement of effector responses [16].

Evidence from preclinical models demonstrates that antibody effector functions play an important role in conferring both therapeutic and preventive efficacy. For example, studies in adult and infant macaques showed that bNAb-mediated protection against a simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) mucosal challenge includes clearance of virus from distal sites, likely mediated by Fc-effector mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [17, 18]. Experiments in humanized-mice (hu-mice) showed that both bNAb-mediated protective efficacy and effects on established HIV-1 viral reservoirs are dependent upon engagement of the Fcγ receptor (FcγR) [19]. Moreover, in a hu-mouse model bNAbs accelerated the clearance of CD4+ T cells infected with primary viral isolates by FcγR-mediated mechanisms [20]. As with neutralization activity, bNAbs differ in their ability to mediate Fc-effector functions. Efficient ADCC requires sustained cell surface binding of bNAbs to Env, suggesting that efficient killing is associated with stronger affinity than that necessary for inhibiting cell-free infection. In addition, although neutralization activity is not necessary to trigger Fc-mediated functions, it has been found to be predictive of infected-cell binding, which is needed to trigger ADCC (reviewed in [21]). Therefore, breadth and potency of neutralizing activity as well as Fc-engagement potential should be considered when selecting bNAbs for clinical evaluation and designing combination regimens with other reservoir altering and immune modulating molecules.

Classification of bNAbs based on Binding Domains

Single B-cell sorting approaches enabled the discovery of numerous highly potent monoclonal antibodies targeting several different domains on the Env trimer [15, 22]. Additional methods using unbiased B cell microculture and, more recently, barcoded antigens have also led to the identification of potent bNAbs [4]. The most clinically advanced bNAbs target a subset of vulnerable sites on Env (Table 1): VRC01 [28], 3BNC117 [29], VRC07–523 [30], N6 [31], and their variants target the CD4 binding site (CD4bs); 10-1074 [26], and PGT121 [23] recognize the base of the V3 loop and surrounding glycans; 10E8 [37], binds to the membrane proximal region (MPER); PGDM1400 [24] and CAP256 [25] recognize the V1–V2 region and associated glycans [39–46]. More recently, bNAbs targeting previously unidentified Env vulnerability sites were discovered, including: gp120–41 interface (eg, 8ANC195 [36]), gp120 silent face (eg, SF12 [34]), and fusion peptide (eg, VRC34.01 [35]). Several newly identified potent bNAbs target known epitopes including the V3 loop (eg, BG18) [27], as well as the CD4 binding site (eg, N49P7, 1–18) [32, 33]. N49P7 is a CD4bs antibody with high breadth that interacts with the relatively conserved inner domain of gp120 [32]. Antibody 1–18 is another newly identified CD4bs antibody that can restrict the development of viral escape [33]. Finally, structural analyses revealed a novel unique targeting mode of the Env transmembrane region, in addition to the MPER, by the germinal center B cell-derived bNAb LN01 [38].

Table 1.

Anti-HIV-1 bNAb Binding Classes

| Binding Site | bNAb | References (original bNAb report) |

|---|---|---|

| V1/V2 apex | PG9 | Walker et al, 2011 [23] |

| PGDM1400 | Sok et al, 2014 [24] | |

| CAP256V2LS | Doria-Rose et al, 2014 [25] | |

| V3 loop | 10-1074, 10-1074-LS | Mouquet et al, 2012 [26] |

| PGT121, PGT121.414.LS | Walker et al, 2011 [23] | |

| BG18 | Freund et al, 2017 [27] | |

| CD4 binding site | VRC01, VRC01 LS | Wu et al, 2010 [28] |

| 3BNC117, 3BNC117-LS | Scheid et al, 2011 [29] | |

| VRC07-523LS | Rudicell et al, 2014 [30] | |

| N6LS | Huang et al, 2016 [31] | |

| N49P7 | Sajadi et al, 2018 [32] | |

| 1-18 | Schommers, 2020 [33] | |

| gp 120 silent face | SF12 | Schoofs et al, 2019 [34] |

| Fusion peptide | VRC34.01 | Kong et al, 2016 [35] |

| gp120-gp41 interface | 8ANC195 | Scharf et al, 2014 [36] |

| MPER | 10E8VLS | Huang et al, 2012 [37] |

| LN01 | Pinto et al, 2019 [38] |

bNAbs shown in bold have entered clinical evaluation.

Abbreviations: bNAbs, broadly neutralizing antibodies; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; MPER, membrane proximal region.

In line with their epitope specificities, different bNAb classes demonstrate characteristic neutralization sensitivity profiles, often explained by amino acid or potential N-linked glycosylation site (PNGS) mutations on or near bNAb contact residues. The bNAbs directed against CD4bs and MPER typically target highly conserved epitopes that carry high fitness costs to escape, and exhibit significant breadth, although often not as potent as other classes. The V3 glycan bNAbs usually are highly potent against clade B viruses, but are not as broadly active against clade C viruses and poorly neutralize CRF 01_AE strains, 96% of which shift N332, a key N-linked glycosylation site for V3 bNAbs, to N334 [12]. In contrast, V2 bNAbs are relatively narrow in activity against B subtypes, but exhibit greater breadth and potency against A and C subtypes. The V2 bNAbs PGDM1400 and CAP256-VRC25.26 are also unusual in that they show different relative potencies against primary isolates versus pseudotyped clade C viruses: CAP256-VRC25.26 shows no significant difference in activity, whereas PGDM1400 is 42-fold less active against primary clade C viruses [47].

Understanding differences in neutralization activity by bNAb classes has guided the selection of antibody combinations for clinical evaluation [48, 49]. Despite the extraordinary in vitro breadth and potency of all bNAbs currently in clinical trials, pre-existing resistance among circulating strains and in the reservoir of PWH, and the risk of escape during therapy pose significant challenges to the development of anti-HIV-1 bNAbs for clinical use. Therefore, ongoing efforts in HIV-1 antibody discovery not only allow the selection of new promising candidates, but continue to provide a roadmap for a better understanding of antibody escape pathways and potential ways to overcome them.

Potential Clinical Applications of Long-Acting HIV bNAbs

Long-acting HIV bNAbs have numerous potential clinical applications (Table 2). For the purposes of this discussion these applications will be categorized as uses for prevention; as a component of long-acting antiretroviral therapy (ART); and as a component of interventions aimed at long-term drug-free remission of HIV.

Table 2.

Potential Clinical Applications of Long-Acting HIV bNAbs

Prevention

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; bNAbs, broadly neutralizing antibodies; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Long-Acting HIV bNAbs for Prevention

Perhaps the most compelling case for use of long-acting HIV bNAbs can be made for their potential role in HIV prevention. Such use comprises both pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP, respectively). The antibody-mediated prevention (AMP) trials, jointly conducted by the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN) and HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) tested the ability of bimonthly infusions of VRC01 to prevent acquisition of HIV-1 by at-risk cisgender men and transgender persons in North America and Europe (HVTN/ 704/HPTN 085) or in at-risk women in sub-Saharan Africa (HVTN 703/HPTN 081) [50]. Although neither study demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in HIV-1 acquisition in the VRC01 arms as compared to placebo, a prespecified secondary analysis demonstrated approximately 75% efficacy in reduction of infection due to HIV-1 isolates sensitive to VRC01. The AMP studies revealed both the promise and limitations of bNAbs as PrEP. On the one hand, these studies demonstrated the feasibility of repeated administration of bNAbs intravenously to more than 3000 participants and the potential for protection against HIV acquisition; on the other hand, the studies highlighted the importance of ensuring that bNAbs used for prevention have high-titer neutralizing activity against HIV variants circulating in a region. Studies using combinations of bNAbs for PrEP are now being designed. Use of bNAbs containing the LS modification in the Fc domain, which prolongs the half-life of the antibodies (see below) could allow for dosing every 3–6 months, thereby increasing the feasibility of sustained delivery of bNAbs for PrEP outside of the clinical trials setting.

An additional potential preventive use of bNAbs is in the setting of post-exposure prophylaxis. Just as hepatitis B immune globulin, varicella-zoster immune globulin and rabies immune globulin have been used to prevent infection with hepatitis B virus, varicella-zoster virus and rabies virus, respectively, HIV-1 bNAbs could be used to augment or replace daily oral antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV infection following occupational exposure, sexual assault or failure of barrier protection. Demonstrating the clinical efficacy of bNAbs for PEP in human clinical trials could pose an insurmountable challenge, however, given the widespread availability and use of oral ART for PEP and the (fortunately) very low rates of HIV acquisition following these types of exposure. A special case of PEP would be administration of bNAbs to neonates born to mothers with HIV, presumably as an adjunct to oral combination ART for the mother and post-partum administration of zidovudine to the infant. Long-acting bNAbs could conceivably have a role in protecting infants from acquiring HIV through breastfeeding (a form of PrEP). Randomized, controlled trials comparing ART alone to ART plus bNAb(s) could conceivably be done in babies born to mothers who present for care late in pregnancy.

Long-Acting bNAbs for Treatment

Several scenarios present a reasonable use case for long-acting bNAbs in the treatment of HIV. These include the use of bNAbs to construct a suppressive regimen in highly treatment-experienced patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) HIV or who are unable to construct a tolerable, effective regimen with available agents; to augment or intensify standard oral ART; to substitute for daily oral ART in patients who are virologically suppressed on a standard ART regimen; in combination with other injectable long-acting agents; and as a bridge during periods of non-adherence to ART. In addition, bNAbs may play role in augmenting HIV-specific responses [51, 52] and reducing the reservoir of latently infected cells harboring replication competent provirus [53]. This latter use of bNAbs to achieve long-term drug-free remission or cure of HIV is mentioned here for completeness but will not be discussed further in this review.

bNAbs for Highly Treatment-Experienced Patients

Patients with repeated episodes of virologic failure due either to MDR HIV or drug intolerance may be able to construct a suppressive regimen by combining a long-acting bNAb together with at least 1 potent agent (eg, an integrase inhibitor, boosted protease inhibitor or entry inhibitor) to achieve virologic suppression. Such was the strategy used successfully in clinical trials of ibalizumab, a host-directed monoclonal antibody that binds to CD4, thereby blocking HIV entry [54]. Although such patients represent a relatively small niche, there remains an unmet medical need for this select group, and relatively small phase 3 trials offer a potentially rapid path toward approval. The principal challenge of such use is determining which bNAb would be most active against a particular patient's virus.

bNAbs to Augment or Intensify ART

In theory, addition of a long-acting bNAb could enhance the potency of an oral combination regimen and/or protect against virologic failure during periods of non-adherence. Given the high rates of virologic suppression in clinical trials of contemporary first-line ART regimens, demonstrating the clinical benefit of adding a long-acting bNAb to such regimens would be challenging and likely require very large sample sizes. Moreover, given the failure to date of single bNAbs to sustain virologic suppression, combination bNAbs most likely would be needed to prevent virologic failure during extended periods of non-adherence. The bar to demonstrating cost-effectiveness of this approach would be very high, given that the cost of bNAbs would be added to, rather than in place of, the cost of oral ART.

bNAbs in Place of Daily Oral ART

Perhaps the most likely therapeutic use of long-acting bNAbs is as a substitute for daily oral ART in patients who have successfully achieved and maintained virologic suppression on standard therapy. This use would be analogous to that of long-acting injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine (Cabenuva®). Preliminary proof of concept of this approach was demonstrated in a pilot study (Tatelo) in Botswana of children diagnosed with HIV at birth and placed immediately on ART [55]. At a median age of 3.6 years, children who had been virologically suppressed for the preceding 6 months on oral ART received infusions of VRC01LS plus 10-1074 every 4 weeks while continuing on ART. After on overlap period of at least 8 weeks, 25 children discontinued oral ART while continuing on VRC01LS and 10-1074. Eleven children (44%) maintained virologic suppression for 24 weeks [56]. Although data on neutralization resistance are not yet available, the Tatelo study illustrates both the potential benefits and limitations of this approach. Whereas nearly half of children maintained virologic suppression, because children entered into Tatelo were virologically suppressed, it was not possible to determine prospectively whether their HIV was susceptible to the bNAbs employed. Neutralization assays using pseudotyped viruses constructed using env genes amplified from proviral DNA may permit susceptibility testing in this situation, but not all samples will generate a result and validation against clinical response is still pending. Identifying bNAbs better matched to viruses prevalent in the population and improvements in diagnostic tests to identify patients best suited for use of bNAbs in place of oral ART are needed in order to implement this approach.

bNAbs in Combination With Other Long-Acting Antiretroviral Drugs

An alternative scenario to one in which bNAbs substitute entirely for small-molecule antiretrovirals is the use of long-acting bNAbs in combination with 1 or more long-acting ARVs. Ideally such applications would pair a long-acting bNAb with a long-acting ARV that has a similar dosing interval. This strategy is being explored in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol A5357, which combines long-acting cabotegravir with VRC07-523LS (NCT03739996). Because of concerns about emergence of cabotegravir resistance should the bNAb prove ineffective, participants are screened using a neutralization assay based on amplifying env from proviral DNA.

bNAbs as a Bridge During Periods of Non-Adherence

As with long-acting formulations of small-molecule ARVs, bNAbs or bNAb combinations could in theory be employed to establish or maintain virologic suppression in patients unable to adhere to traditional orally dosed ARVs. In principle, this use is similar to the strategy being studied in ACTG LATITUDE study (Long-Acting Therapy to Improve Treatment Success in Daily Life; A5359 [NCT03635788]). As with other potential uses of bNAbs discussed above, limitations of this approach include the need to demonstrate susceptibility to the bNAbs employed; achieving virologic suppression with oral ART prior to switching to bNAbs; the need for parenteral administration; and cost. On the other hand, potential advantages of bNAbs over currently available injectable long-acting ART include longer dosing interval and intravenous or potentially subcutaneous administration in place of intramuscular injection.

Clinical Data to Date

Despite being generally safe, passive transfer of antibodies against HIV-1 was initially abandoned given the limited in vivo antiviral activity of the first generation of bNAbs (reviewed in [11]). Enthusiasm for this approach has continued to grow over the last 5 years, since the discovery of the highly potent new generation bNAbs and results from initial clinical studies showing significant antiviral activity during infection. The safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of antibodies targeting 3 non-overlapping epitopes on the HIV-1 envelope trimer, the CD4 binding site (3BNC117, VRC01, VRC01LS, VRC07-523LS) [39–41, 43, 44, 46], the base of the V3 loop (10-1074, PGT121) [42, 57], and the V1/V2 apex (PDGM-1400) [58] have been reported to date. An antibody targeting the MPER, 10e8, was evaluated in a phase 1 study (NCT03565315), and other CD4bs and V3 loop antibodies (N6LS, NCT03538626, NCT04871113, NCT05291520; CAP256V2LS, NCT04408963) are currently in clinical trials. bNAbs have been evaluated in different populations and clinical scenarios [11], including HIV-exposed infants [59, 60], adults living with HIV who initiated ART during primary infection [61], during ongoing viremia in chronic infection [39, 41, 46, 57, 58, 62], as well as during ART interruption [15, 63–65], and in children who started ART shortly after birth [55]. Overall, bNAb administrations have been generally well-tolerated with infrequent adverse events reported, including following prolonged exposure to repeated bNAb infusions in two phase 2b studies [50, 66]. The antibodies have maintained expected neutralizing activities in serum, and anti-drug antibody (ADA) responses interfering with antibody activity or clearance rates have not been reported [11, 12].

Engineered antibodies designed to have extended half-lives (discussed below) and increased potency and breadth have also been evaluated. VRC07-523LS is a CD4-binding site antibody engineered for increased breadth and potency as well as longer half-life. It showed approximately five times greater in vitro potency than VRC01 against clade B and C HIV-1 viruses [30]. Evaluation of serum neutralizing activity following VRC07-523LS administration in uninfected adults confirmed its superior antiviral activity in comparison to VRC01 and its long-acting variant VRC01LS [44]. Clinical studies of engineered molecules displaying multi-HIV-1 Env specificity (eg, SAR441236, which targets CD4bs, V1/V2 apex and MPER [67]), or with dual affinity to Env and a cellular target (eg, 10E8.4/iMab, which targets HIV-1 Env MPER and domain 2 of CD4 [67], or MGD014, a dual-affinity re-targeting antibody (DART) molecule derived from the non-neutralizing antibody A32 that binds a CD4-induced epitope on HIV-1 gp120 as well as CD3ε chain [68]) are underway, with results expected in the near future (NCT03875209, NCT03705169). It will be interesting to see if these engineered molecules will maintain the favorable safety profiles of the naturally occurring bNAbs and will not induce clinically significant anti-antibody responses that affect half-life and activity.

Several completed and ongoing studies are assessing the roles anti-HIV-1 bNAbs may play in prevention, therapy and cure strategies. As discussed above, the AMP studies demonstrated proof of concept that an HIV-1 bNAb can reduce the risk of HIV acquisition of antibody-sensitive viruses, in this case defined by in vitro neutralizing IC80 < 1 μg/mL [50]. Results from these studies demonstrated that in vitro neutralization sensitivity of HIV-1 pseudoviruses to VRC01 is a biomarker of prevention efficacy and suggest the value of ID80 neutralization titers as a predictive biomarker [42] of efficacy, as initially noted in a meta-analysis of NHP challenge studies [69]. This benchmark may facilitate screening and down selection of future bNAb combinations for prevention [70]. It is not yet known, however, if findings from the AMP studies can be extended to other antibody combinations and how they relate to antibody efficacy in maintaining viral suppression during infection.

During established infection, single bNAb infusions have led to transient 1- to 2-log10 declines in plasma viremia [39, 41, 42, 57, 58]. Pre-existing resistance and selection of escape variants following bNAb administration were reported in all studies. For example, 3BNC117, a CD4bs bNAb, induces shifts in the Env expressed by viral quasispecies, but the nature of these shifts differs among participants and does not consistently lead to increased resistance [51]. In contrast, 10-1074 (V3 loop) infusions select a series of recurrent amino acid mutations in key contact residues, most of which (> 95%) eliminate the PNGS at position N332 [42]. Escape variants emerge as early as 1 week after 10-1074 infusion, and full-length Env deep sequencing revealed the presence of circulating pre-existing 10-1074 resistant variants at very low frequencies in these individuals [42]. In these first studies, full viral suppression was achieved only in participants with low starting plasma HIV-1 RNA levels (< 2000 copies/mL) [39, 57]. In some cases suppression was long-lived, with viral rebound occurring when bNAb serum levels were below the limit of detection [57]; rebound viruses in those participants demonstrated full or partial PGT121 sensitivity [57].

Monotherapy with bNAbs was also tested in the context of analytical treatment interruption (ATI). Two studies evaluated 3BNC117 monotherapy in chronically infected individuals who achieved viral suppression on ART and another study evaluated VRC01. In contrast to previous studies [13, 14], the two 3BNC117 studies showed delay in viral rebound when compared to historical controls (8.4 vs 5.5 weeks, respectively [64, 71]) and restriction of viral populations emerging from the reservoir. In contrast, the effects of VRC01 were more limited, reflecting the prevalence of pre-existing resistance to VRC01 in the evaluated cohort [63]. A study in Thai adult participants who initiated ART during acute HIV-1 infection (ie, Fiebig stages I–III) showed very similar results with regard to viral suppression, where median time to viremia was not significantly different between the VRC01 and placebo groups [61]. However, circulating Env sequences and neutralization sensitivity did not differ between diagnosis (pre-ART) and rebound, indicating lack of VRC01 resistance selection during the short duration of viral replication in individuals harboring homogenous viral populations as a result of very early ART initiation [72]. Collectively, the initial bNAb monotherapy studies show that, although these antibodies have significant antiviral activity, they resemble small molecule ARVs in that pre-existing resistant variants can emerge from the reservoir.

Subsequent studies evaluated combinations of 2 or 3 bNAbs targeting non-overlapping sites on HIV-1 envelope to provide broader antiviral coverage. In contrast to single infusions of either 3BNC117 or 10-1074 [39, 42], the combination of 3BNC117 and 10-1074 led to more pronounced and prolonged reduction of viremia [62]. However, 3 of 7 enrolled participants carried pre-existing resistance mutations to 1 or both antibodies and showed no response or short-lived decline in viremia after bNAb infusions. Rebound viremia was associated with the emergence of viruses that were resistant to 10-1074. This finding is consistent with the relatively shorter half-life of 3BNC117 that leads effectively to a period of 10-1074 monotherapy. Interestingly, none of the 4 participants whose virus initially was sensitive to the 2 antibodies developed de novo resistance to 3BNC117, despite residual viremia in 3 of them and frequent recombination events between circulating viruses [62]. Recently, results from the first study of a triple-bNAb combination—PGDM1400 (V2 loop), PGT121 (V3 loop), VRC07-523LS (CD4bs)—in viremic individuals became available [58]. Modeling of available vitro neutralization data projected that this triple bNAb combination neutralizes 99% of strains in large viral panels, with > 80% of strains being sensitive to as least 2 of the bNAbs [73]. In vivo, the triple-bNAb infusions resulted in significant decline in viremia, although viral rebound occurred in all participants within a median of 20 days after nadir. Rebound viruses demonstrated partial to complete resistance to PGDM1400 and PGT121 in vitro, but susceptibility to VRC07-523LS was preserved among the Env sequences analyzed. Despite the lack of VRC07-523LS resistance, viral rebound occurred in the presence of high mean VRC07-523LS serum concentrations. These data suggest that bNAb combinations not only need to provide broad neutralization activity but also maintain high titers relative to the ID80 in order to achieve viral control [58]. Importantly, these studies show that the efficacy of bNAbs during viremia does not achieve the degree of virological suppression of current ART regimens.

Unlike the findings during ongoing viremia, the combination of 2 bNAbs, 3BNC117 and 10-1074, maintained full viral suppression in ART-treated individuals who harbored bNAb-sensitive viruses when they discontinued ART and received combination antibody infusions over 6–20 weeks (median time to viral rebound 21 and 28.5 weeks, respectively). Among 33 participants enrolled in both studies, 4 maintained suppression beyond the study follow-up period of 30 and 48 weeks [53, 65]. In both studies, viral rebound did not occur until 3BNC117 reached serum concentrations below 10 µg/mL. As seen in the viremic studies, the longer half-life of 10-1074 resulted in a period of 10-1074 monotherapy and selection of resistance. However, there was no emergence of double-resistant variants. These results demonstrate that a combination of 2 bNAbs is effective in maintaining suppression for extended periods of time in individuals harboring HIV-1 strains sensitive to the antibodies [53, 65]. Despite these promising results, selecting participants with bNAb-sensitive viral reservoirs remains a challenge. In vitro neutralizing sensitivity of viruses cultured from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) did not reliably predict pre-existing resistance [65, 71]. Similarly, neither genotypic nor phenotypic analyses of baseline Env sequences derived from PBMCs predicted clinical outcomes in the cohort of 18 participants who received repeated 3BNC117 and 10-1074 infusions without pre-screening [53]. Other studies are applying similar screening methods and results will help better define the sensitivity cutoffs and the value of different assays. Moreover, improvement of screening tools to predict bNAb susceptibility are expected with the development of sequencing methods that allow more in depth evaluation of reservoir diversity during chronic HIV-1 infection, coupled with improved understanding of bNAb-escape pathways and modeling tools. In the meantime, the potential of bNAbs as long-acting ARVs continues to be evaluated in proof-of-concept studies (eg, an ART-interruption study of the triple-bNAb combination described above was recently completed, NCT03707977). In addition, ongoing and planned studies will evaluate if the period of bNAb-mediated viral suppression can be extended further by long-acting bNAb variants (NCT05079451, NCT04319367) or if viral suppression can be maintained by 1 or 2 bNAbs and a single long-acting antiretroviral drug (NCT04811040, NCT03739996).

Anti-HIV-1 bNAbs are also being explored in cure strategies. As discussed earlier, antibodies are among the key modulators of immunity and differ from ART in that they can recruit immune effector functions through their Fc domains [16]. Until recently, limited data were available on the effects of bNAbs on HIV-1 persistence in humans. However, a recent study of repeated doses of 3BNC117 and 10-1074 during ATI or ART suppression demonstrated changes in the size and composition of the intact proviral reservoir after 6 months of antibody therapy among participants who had been on suppressive ART for > 7 years prior to the study [53]. Although the observed changes were not directly associated with long-term viral control, the data suggest that bNAbs can alter the HIV-1 reservoir. Several ongoing and planned studies, including interventions during early or acute HIV-1 infection or at ART initiation, will further assess if anti-HIV-1 bNAbs, alone or in combination with other immunologic strategies, can affect HIV-1 persistence and augment host immune responses that may result in long-term viral control. The potential roles of bNAbs in HIV cure strategies are beyond the scope of this review but were recently discussed in [74–76].

Modifications to Increase Half-Life

The half-lives of most bNAbs allow intravenous dosing every 4 weeks to maintain trough concentrations in the target range (ie, several fold above the plasma level required for virus neutralization). By this criterion, bNAbs may already be considered potential “long-acting” antiretroviral agents by comparison to small molecule ARVs that require daily oral dosing. bNAbs can be made even longer-acting through modifications of the Fc domain that extend the half-life of these antibodies, resulting in substantially prolonged dosing intervals (eg, 3–6 months). The basis of this half-life extension is enhanced binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), which plays an important role in regulating the serum half-life of immunoglobulin G (IgG). Two sets of mutations, M252Y, S352T, and T256E (YTE modification) and M428L and N434S (LS modification) that increase Fc binding to FcRn have commonly been employed to extend the half-life of therapeutic antibodies [77].

Introduction of the LS modification into VRC01 to create VRC01-LS extended the half-life by more than 4-fold (from 15 to 71 days) without altering neutralizing activity or inducing anti-drug antibodies [43]. Likewise, the terminal half-life of VRC01-LS administered subcutaneously to neonates born to women with HIV was significantly greater than that of VRC01, potentially allowing for administration every 3 months [60]. The second-generation bNAb VRC07-523LS has a serum half-life of 38 days following intravenous administration and 33 days following subcutaneous administration and demonstrated potent anti-HIV activity in viremic adults with HIV [44, 78]. The LS modification has been incorporated into numerous other bNAbs with various target specificities, many of which are in various stages of clinical development [1, 79].

Longterm delivery of bNAbs through antibody gene transfer is another strategy to extend bioavailability that has advanced to clinical evaluation in some cases. Delivering the genetic sequence of selected antibodies using viral vectors, DNA or RNA can circumvent challenges associated with protein characterization and large-scale production, and may facilitate production of more complex molecules [80–82]. A recombinant adenoassociated virus (rAAV1) vector encoding the gene for PG9, which targets the V2 loop, was found to be safe in a phase 1 study but led to low circulating antibody levels, while inducing antivector and neutralizing anti-PG9 antibody responses [83]. More recently, a small phase 1 study tested an AAV8 vector encoding VRC07 (a CDbs bNAb) in 8 PWH on suppressive ART. As with the prior study, the construct was safe at all doses tested. AAV8-VR07 led to measurable amounts of active VRC07 in serum in all 8 participants, reaching concentrations above 1 μg/mL in 3 of 8 individuals. Although these are relatively low levels compared to passive administration, concentrations remained near maximal concentration for up to 3 years of follow-up in 4 of the participants. Anti-drug antibody (ADA) responses were induced but did not affect the continued production of VRC07 [84]. This study is an important step forward in the development of bNAb-gene delivery platforms and provides proof-of-principle that AAV vectors can durably produce biologically active and difficult-to-induce bNAbs in vivo. At the same time, it highlights the need for continued optimization of approaches to achieve sufficient protein expression while limiting antivector or ADA responses that interfere with bNAb function.

Lessons Learned From SARS-CoV-2 mAbs

The rapid development and implementation of mAbs with potent neutralizing activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) for prevention and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) provide both a model and a caveat for the use of bNAbs for HIV. As with the bNAbs, the SARS-CoV-2 mAbs are directed against the surface protein responsible for receptor binding and virus entry (the spike or S protein). Bamlanivimab was the first mAb granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for the treatment of outpatients with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection who were at increased risk of progression to severe disease (ie, requiring hospital care) or death. This authorization was based on interim results of a phase 2 trial that showed significantly greater reductions in SARS-CoV-2 RNA and slightly lower disease severity in recipients of the mAb, administered intravensously, as compared to controls [85]. Because a subsequent trial demonstrated greater reductions in SARS-CoV-2 RNA with the combination of bamlanivimab and etesevimab [86], bamlanivimab alone never progressed to phase 3 trials for a treatment indication. The combination of bamlanivimab plus etesevimab significantly reduced the risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization as compared to placebo, leading to the EUA of this combination [80]. Notably, there are no data on the virologic or clinical activity of etesevimab alone, so it is unclear whether bamlanivimab is an essential component of this combination [81]. Moreover, soon after an EUA for this combination was granted, SARS-CoV-2 variants resistant to bamlanivimab began circulating, so that only the etesevimab component of the combination remained active [82].

The combination of casirivimab plus imdevimab, developed initially as a dual intravenous mAb cocktail, received EUA for treatment of symptomatic outpatients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of severe disease based on interim results of a phase 1–3 trial that demonstrated greater reductions in SARS-CoV-2 RNA [83]; subsequently, the phase 3 component of the trial confirmed the clinical efficacy of this combination, showing a 71.3% reduction in the relative risk of COVID-19 hospitalization or death [84]. Subcutaneous administration of this cocktail prevented disease progression at risk persons with asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, although the relative risk reduction (31.5%) was more modest than with the intravenous formulation [87]. Based on these data, subcutaneous administration of casirivimab plus imdevimab was granted EUA for circumstances in which intravenous dosing was not feasible or would lead to delays in administration. By contrast, casirivimab plus imdevimab was not effective in reducing mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, except for the subset of participants who were SARS-CoV-2 antibody-negative at time of enrollment [88].

The mAb sotrovimab was found to reduce the risk of hospitalization or death by 85% when administered intravenously as a single agent and received EUA for use in symptomatic outpatients at risk for severe COVID-19 [89, 90]; intramuscular administration was shown to be non-inferior to intravenous dosing in a randomized comparison [91]. A potential advantage of sotrovimab is that it carries the LS modification in the Fc domain, resulting in a substantially prolonged half-life that may be advantageous in its use for prevention; trials of sotrovimab for this indication are ongoing.

The use of each of these agents has been upended by the serial emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern with reduced susceptibility to the mAbs. All of these mAbs retained good activity against the Alpha variant, but Beta and Gamma showed resistance to neutralization by bamlanivimab, etesevimab, and casirivimab, whereas susceptibility to imdevimab and sotrovimab was retained; the Delta variant remained resistant to bamlanivimab but was susceptible to other available mAbs [92]. The initial Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) was resistant to all of these mAbs except sotrovimab, but the BA.2 subvariant demonstrates resistance to sotrovimab as well [93]. As a result, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has withdrawn or limited the EUAs for these mAbs. As of this writing (June 2022), only bebtelovimab is authorized for treatment of COVID-19, and that EUA is based solely on phase 2 virologic data and retained susceptibility of Omicron variants to this mAb [94].

The use of mAbs for prevention faced similar challenges. Bamlanivimab was the first mAb shown to protect against symptomatic COVID-19 in those with potential exposure in skilled nursing or long-term care facilities [95], but by the time these results were released bamlanivimab was only available in combination with etesevimab. Moreover, variants in circulation at the time were resistant to bamlanivimab but remained susceptible to etesevimab. Hence, the EUA authorizing use of bamlanimivab plus etesevimab for post-exposure prophylaxis was based on no clinical evidence that etesevimab provided such protection [96]. Similarly, the combination of casirivimab plus imdevimab was shown to protect household contacts against symptomatic COVID-19 [97]. The emergence of Omicron with 4 months of the EUA of these mAbs for post-exposure prophylaxis rendered them no longer useful for that indication. Like sotrovimab, tixagevimab, and cilgavimab have modifications in the Fc domain that lead to prolonged persistence in serum. This combination was shown to be effective as pre-exposure prophylaxis in person with an increased risk of inadequate response to COVID-19 vaccination, increased risk of exposure to SARS-CoV2, or both [98]. The long serum half-life makes this combination particularly suitable for periodic administration to immunocompromised patients who remain susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection despite vaccination. However, Omicron and its subvariants are resistant to tixagevimab [92]. Although these variants remain neutralizable by achievable concentrations of cilgavimab, just how effective this antibody alone is in preventing COVID-19 remains uncertain.

Although the experience with mAbs for COVID-19 shows the potential of monoclonal antibodies against infectious pathogens at a large scale, it highlights the challenges of developing novel therapeutic and preventive interventions in the setting of a rapidly evolving pandemic. Although the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is now well established in the human population, variants continue to emerge within individuals and in populations. Even combinations of antibodies quickly become obsolete when resistant variants supplant previously circulating viruses as the predominant variant. Given the substantially greater heterogeneity of HIV-1 variants, this experience serves as a cautionary tale.

Challenges in the Clinical Development of Long-Acting bNAbs for HIV

As is clear from the foregoing, the clinical development of long-acting bNAbs for HIV faces myriad challenges. These include selecting the right combination of bNAbs for use to match the susceptibility of HIV-1 variants prevalent in specific populations; to select appropriate trial participants based on bNAb susceptibility for studies combining bNAbs with other long-acting antiretroviral drugs; to demonstrate superiority or non-inferiority of bNAbs or bNAb-containing regimens as compared to current oral or injectable regimens for HIV treatment and prevention; and to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of bNAb-containing regimens. Ensuring equitable access to these agents poses an additional challenge. Improvements in manufacturing to bring down the cost of goods and advances in delivery systems will be needed to make long-acting bNAbs practical alternatives that are accessible on a global scale for persons with or at risk for HIV.

CONCLUSIONS

The advent of bNAbs as therapeutic agents for the prevention and treatment of HIV offers considerable promise as adjuncts or alternatives to long-acting ARVs in specific populations. This promise is tempered, however, by the considerable challenges faced in proving their specific indications, and in demonstrating their cost-effectiveness for those indications in the face of existing ART regimens. Advances in antibody discovery, engineering, manufacturing and delivery are expected, which should further the advancement of this strategy.

Contributor Information

Marina Caskey, Rockefeller University, New York, New York, USA.

Daniel R Kuritzkes, Division of Infectious Diseases, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the Einstein-Rockefeller-CUNY (grant number P30 AI124414) and Harvard University (grant number P30 AI060354) Centers for AIDS Research and the REACH (grant number UM1 AI164565), and BEAT-HIV (grant number UM1 AI12662) Delaney Collaboratories for HIV Cure Research to M. C. and the Boston HIV Clinical Trials Unit (grant numbers UM1 AI069412, U01 AI35940) and R01 AI157854 to D. R. K.

Supplement sponsorship. This article appears as part of the supplement “Long-Acting and Extended-Release Formulations for the Treatment and Prevention of Infectious Diseases,” sponsored by the Long-Acting/Extended Release Antiretroviral Research Resource Program (LEAP).

References

- 1. AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition. Neutralizing antibodies January 2021. Available at: https://www.avac.org/sites/default/files/infographics/neutralizingAntibodies_jan2021.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022.

- 2. Sok D, Burton DR. Recent progress in broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV. Nat Immunol 2018; 19:1179–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein F, Mouquet H, Dosenovic P, Scheid JF, Scharf L, Nussenzweig MC. Antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine development and therapy. Science 2013; 341:1199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gruell H, Schommers P. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 and concepts for application. Curr Opin Virol 2022; 54:101211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gray ES, Madiga MC, Hermanus T, et al. The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4+ T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. J Virol 2011; 85:4828–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sather DN, Armann J, Ching LK, et al. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol 2009; 83:757–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mascola JR, D'Souza P, Gilbert P, et al. Recommendations for the design and use of standard virus panels to assess neutralizing antibody responses elicited by candidate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccines. J Virol 2005; 79:10103–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sarzotti-Kelsoe M, Bailer RT, Turk E, et al. Optimization and validation of the TZM-bl assay for standardized assessments of neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1. J Immunol Methods 2014; 409:131–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simek MD, Rida W, Priddy FH, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J Virol 2009; 83:7337–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doria-Rose NA, Klein RM, Manion MM, et al. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 2009; 83:188–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Caskey M, Klein F, Nussenzweig MC. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 monoclonal antibodies in the clinic. Nat Med 2019; 25:547–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karuna ST, Corey L. Broadly neutralizing antibodies for HIV prevention. Annu Rev Med 2020; 71:329–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trkola A, Kuster H, Rusert P, et al. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med 2005; 11:615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehandru S, Vcelar B, Wrin T, et al. Adjunctive passive immunotherapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals treated with antiviral therapy during acute and early infection. J Virol 2007; 81:11016–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, et al. A method for identification of HIV gp140 binding memory B cells in human blood. J Immunol Methods 2009; 343:65–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bournazos S, Wang TT, Dahan R, Maamary J, Ravetch JV. Signaling by antibodies: recent progress. Annu Rev Immunol 2017; 35:285–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu J, Ghneim K, Sok D, et al. Antibody-mediated protection against SHIV challenge includes systemic clearance of distal virus. Science 2016; 353:1045–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hessell AJ, Jaworski JP, Epson E, et al. Early short-term treatment with neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies halts SHIV infection in infant macaques. Nat Med 2016; 22:362–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bournazos S, Klein F, Pietzsch J, Seaman MS, Nussenzweig MC, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies require Fc effector functions for in vivo activity. Cell 2014; 158:1243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lu CL, Murakowski DK, Bournazos S, et al. Enhanced clearance of HIV-1-infected cells by anti-HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies in vivo. Science 2016; 352:1001–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rossignol E, Alter G, Julg B. Antibodies for human immunodeficiency virus-1 cure strategies. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, et al. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature 2009; 458:636–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, et al. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature 2011; 477:466–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sok D, van Gils MJ, Pauthner M, et al. Recombinant HIV envelope trimer selects for quaternary-dependent antibodies targeting the trimer apex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:17624–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, et al. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature 2014; 509:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mouquet H, Scharf L, Euler Z, et al. Complex-type N-glycan recognition by potent broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:E3268–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Freund NT, Wang H, Scharf L, et al. Coexistence of potent HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies and antibody-sensitive viruses in a viremic controller. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9:eaal2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, et al. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science 2010; 329:856–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, et al. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science 2011; 333:1633–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rudicell RS, Kwon YD, Ko SY, et al. Enhanced potency of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody in vitro improves protection against lentiviral infection in vivo. J Virol 2014; 88:12669–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang J, Kang BH, Ishida E, et al. Identification of a CD4-binding-site antibody to HIV that evolved near-pan neutralization breadth. Immunity 2016; 45:1108–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sajadi MM, Dashti A, Rikhtegaran Tehrani Z, et al. Identification of near-pan-neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 by deconvolution of plasma humoral responses. Cell 2018; 173:1783–95 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schommers P, Gruell H, Abernathy ME, et al. Restriction of HIV-1 Escape by a highly broad and potent neutralizing antibody. Cell 2020; 180:471–89 e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schoofs T, Barnes CO, Suh-Toma N, et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies recognize the silent face of the HIV envelope. Immunity 2019; 50:1513–29 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kong R, Xu K, Zhou T, et al. Fusion peptide of HIV-1 as a site of vulnerability to neutralizing antibody. Science 2016; 352:828–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scharf L, Scheid JF, Lee JH, et al. Antibody 8ANC195 reveals a site of broad vulnerability on the HIV-1 envelope spike. Cell Rep 2014; 7:785–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang J, Ofek G, Laub L, et al. Broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by a gp41-specific human antibody. Nature 2012; 491:406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pinto D, Fenwick C, Caillat C, et al. Structural basis for broad HIV-1 neutralization by the MPER-specific human broadly neutralizing antibody LN01. Cell Host Microbe 2019; 26:623–37 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caskey M, Klein F, Lorenzi JC, et al. Viraemia suppressed in HIV-1-infected humans by broadly neutralizing antibody 3BNC117. Nature 2015; 522:487–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ledgerwood JE, Coates EE, Yamshchikov G, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and neutralization of the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody VRC01 in healthy adults. Clin Exp Immunol 2015; 182:289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lynch RM, Boritz E, Coates EE, et al. Virologic effects of broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01 administration during chronic HIV-1 infection. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:319ra206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Caskey M, Schoofs T, Gruell H, et al. Antibody 10–1074 suppresses viremia in HIV-1-infected individuals. Nat Med 2017; 23:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gaudinski MR, Coates EE, Houser KV, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of the fc-modified HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody VRC01LS: a phase 1 open-label clinical trial in healthy adults. PLoS Med 2018; 15:e1002493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gaudinski MR, Houser KV, Doria-Rose NA, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of broadly neutralising human monoclonal antibody VRC07-523LS in healthy adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation clinical trial. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e667–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stephenson KE, Julg B, Ansel J, et al. Therapeutic activity of PGT121 monoclonal antibody in HIV-infected adults [abstract 145LB]. In, Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections Abstract Book ( Seattle), San Francisco: CROI Foundation/IAS-USA, 2019:54. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen G, Coates E, Fichtenbaum C, et al. Safety and virologic effect of the broadly neutralizing antibodies, VRC01LS or VRC07-523LS, administered to HIV-infected adults in a phase 1 clinical trial. J Intl AIDS Soc 2019; 22(Suppl 5):100. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lorenzi JCC, Mendoza P, Cohen YZ, et al. Neutralizing activity of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies against primary african isolates. J Virol 2020; 95:e01909–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kong R, Louder MK, Wagh K, et al. Improving neutralization potency and breadth by combining broadly reactive HIV-1 antibodies targeting major neutralization epitopes. J Virol 2015; 89:2659–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wagh K, Bhattacharya T, Williamson C, et al. Optimal combinations of broadly neutralizing antibodies for prevention and treatment of HIV-1 clade C infection. PLoS Pathog 2016; 12:e1005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Corey L, Gilbert PB, Juraska M, et al. Two randomized trials of neutralizing antibodies to prevent HIV-1 acquisition. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1003–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schoofs T, Klein F, Braunschweig M, et al. HIV-1 therapy with monoclonal antibody 3BNC117 elicits host immune responses against HIV-1. Science 2016; 352:997–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nishimura Y, Gautam R, Chun TW, et al. Early antibody therapy can induce long-lasting immunity to SHIV. Nature 2017; 543:559–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gaebler C, Nogueira L, Stoffel E, et al. Prolonged viral suppression with anti-HIV-1 antibody therapy. Nature 2022; 606:368–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Emu B, Fessel J, Schrader S, et al. Phase 3 study of ibalizumab for multidrug-resistant HIV-1. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Maswabi K, Ajibola G, Bennett K, et al. Safety and efficacy of starting antiretroviral therapy in the first week of life. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shapiro RL, Maswabi K, Ajibola G, et al. Treatment with broadly neutralizing antibodies in children with HIV in Botswana. 29th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Denver, Colorado, 2022.

- 57. Stephenson KE, Julg B, Tan CS, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity of PGT121, a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody against HIV-1: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 clinical trial. Nat Med 2021; 27:1718–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Julg B, Stephenson KE, Wagh K, et al. Safety and antiviral activity of triple combination broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody therapy against HIV-1: a phase 1 clinical trial. Nat Med 2022; 28:1288–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cunningham CK, McFarland EJ, Morrison RL, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 monoclonal antibody VRC01 in HIV-exposed newborn infants. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:628–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McFarland EJ, Cunningham CK, Muresan P, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of a long-acting broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) monoclonal antibody VRC01LS in HIV-1-exposed newborn infants. J Infect Dis 2021; 224:1916–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Crowell TA, Colby DJ, Pinyakorn S, et al. Safety and efficacy of VRC01 broadly neutralising antibodies in adults with acutely treated HIV (RV397): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bar-On Y, Gruell H, Schoofs T, et al. Safety and antiviral activity of combination HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies in viremic individuals. Nat Med 2018; 24:1701–07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bar KJ, Sneller MC, Harrison LJ, et al. Effect of HIV antibody VRC01 on viral rebound after treatment interruption. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2037–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cohen YZ, Lorenzi JCC, Krassnig L, et al. Relationship between latent and rebound viruses in a clinical trial of anti-HIV-1 antibody 3BNC117. J Exp Med 2018; 215:2311–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mendoza P, Gruell H, Nogueira L, et al. Combination therapy with anti-HIV-1 antibodies maintains viral suppression. Nature 2018; 561:479–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Takuva S, Karuna ST, Juraska M, et al. Infusion reactions after receiving the broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01 or placebo to reduce HIV-1 acquisition: results from the phase 2b antibody-mediated prevention randomized trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2022; 89:405–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Huang Y, Yu J, Lanzi A, et al. Engineered bispecific antibodies with exquisite HIV-1-neutralizing activity. Cell 2016; 165:1621–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sung JA, Pickeral J, Liu L, et al. Dual-Affinity Re-targeting proteins direct T cell-mediated cytolysis of latently HIV-infected cells. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:4077–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pegu A, Borate B, Huang Y, et al. A meta-analysis of passive immunization studies shows that serum-neutralizing antibody titer associates with protection against SHIV challenge. Cell Host Microbe 2019; 26:336–46 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Huang Y, Zhang L, Eaton A, et al. Prediction of serum HIV-1 neutralization titers of VRC01 in HIV-uninfected Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) trial participants. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022; 18:1908030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Scheid JF, Horwitz JA, Bar-On Y, et al. HIV-1 antibody 3BNC117 suppresses viral rebound in humans during treatment interruption. Nature 2016; 535:556–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Cale EM, Bai H, Bose M, et al. Neutralizing antibody VRC01 failed to select for HIV-1 mutations upon viral rebound. J Clin Invest 2020; 130:3299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Stephenson KE, Wagh K, Korber B, Barouch DH. Vaccines and broadly neutralizing antibodies for HIV-1 prevention. Annu Rev Immunol 2020; 38:673–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Deeks SG, Archin N, Cannon P, et al. Research priorities for an HIV cure: International AIDS Society global scientific strategy 2021. Nat Med 2021; 27:2085–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hsu DC, Mellors JW, Vasan S. Can broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies help achieve an ART-free remission? Front Immunol 2021; 12:710044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ward AR, Mota TM, Jones RB. Immunological approaches to HIV cure. Semin Immunol 2021; 51:101412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ward ES, Devanaboyina SC, Ober RJ. Targeting FcRn for the modulation of antibody dynamics. Molecular immunology 2015; 67:131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chen G, Coates E, Fichtenbaum C, et al. Safety and virologic effect of the HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies, VRC01LS or VRC07-523LS, administered to HIV-infected adults in a phase 1 clinical trial. 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS2019). Mexico City, Mexico, 2019.

- 79. Mahomed S, Garrett N, Baxter C, Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS. Clinical trials of broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for human immunodeficiency virus prevention: a review. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:370–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, et al. Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab in mild or moderate COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Doggrell SA. Do we need bamlanivimab? Is etesevimab a key to treating COVID-19? Expert opinion on biological therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2021; 21:1359–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Widera M, Wilhelm A, Hoehl S, et al. Limited neutralization of authentic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 variants carrying E484K in vitro. J Infect Dis 2021; 224:1109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:238–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGEN-COV Antibody combination and outcomes in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325:632–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. O'Brien MP, Forleo-Neto E, Sarkar N, et al. Effect of subcutaneous casirivimab and imdevimab antibody combination vs placebo on development of symptomatic COVID-19 in early asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022; 327:432–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Group RC. Casirivimab and imdevimab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 2022; 399:665–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Early treatment for COVID-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1941–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Effect of sotrovimab on hospitalization or death among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022; 327:1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Shapiro AE, Sarkis E, Acloque J, et al. Intramuscular sotrovimab is noninferior to intravenous sotrovimab for COVID-19. 29th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Denver, Colorado (virtual) 2022.

- 92. Takashita E, Kinoshita N, Yamayoshi S, et al. Efficacy of antibodies and antiviral drugs against COVID-19 Omicron Variant. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:995–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Takashita E, Kinoshita N, Yamayoshi S, et al. Efficacy of antiviral agents against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariant BA.2. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1475–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Eli Lilly . Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency use authorization for bebtelovimab. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/156152/download. Accessed 31 May 2022.

- 95. Cohen MS, Nirula A, Mulligan MJ, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab on incidence of COVID-19 among residents and staff of skilled nursing and assisted living facilities: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 326:46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kuritzkes DR. Bamlanivimab for prevention of COVID-19. JAMA 2021; 326:31–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. O'Brien MP, Forleo-Neto E, Musser BJ, et al. Subcutaneous REGEN-COV antibody combination to prevent Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1184–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Levin MJ, Ustianowski A, De Wit S, et al. Intramuscular AZD7442 (tixagevimab-cilgavimab) for prevention of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:2188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]